Essay on Coronavirus Vaccine

500+ words essay on coronavirus vaccine.

The Coronavirus has infected millions of people so far all over the world. In addition to that, millions of people have lost their lives to it. Ever since the outbreak, researchers all over the world have been working constantly to develop vaccines that will work effectively against the virus. We will take a look at the Coronavirus vaccine that is present today. Vaccines have the ability to save people’s lives. Developing the vaccine for Coronavirus was a huge step to end the pandemic.

Working of Coronavirus Vaccine

As Coronavirus caused a lot of confusion and fear amongst people, it is natural people were not aware of how the vaccine works. To begin with, a vaccine will work by mimicking an infectious agent.

The agent can be viruses, bacteria or any other microorganisms. They carry the potential of causing disease. When it mimics that, our immune system learns how to respond against it rapidly and efficiently.

As per the traditional methods, vaccines have managed to do this as they introduce a weakened form of an infectious agent. It enables our immune system to basically build its memory.

As a result, our immune system can then identify it quickly and fight against it before it gets the chance to harm us or make us ill. Similarly, some of the coronavirus vaccines have been made like that.

On the other hand, there are other coronavirus vaccines that researchers have developed by making use of new approaches. We refer to them as messenger RNA or mRNA vaccines.

Over here, they do not introduce antigens in our bodies. Instead, mRNA vaccines give the genetic code our body needs to enable our immune system for producing the antigen itself.

For several years, researchers have been studying mRNA vaccine technology. Thus, they do not contain any live virus and also do not interfere with the human DNA .

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Safety of Coronavirus Vaccine

While the vaccines are being developed at a fast pace, they also require rigorous testing. The tests are done in clinical trials to ensure that they meet the benchmarks for the safety and efficiency of international standards.

When they meet the standards, then only can they get the go-ahead from WHO and national regulatory agencies. UNICEF has said that it will attain and supply only those vaccines that meet the WHO guidelines and have met the regulatory approval.

As of now, the vaccine doses are limited in number. Thus, the healthcare workers, first responders, people over the age of 75 and residents of long-term care facilities will receive the first doses.

After that, everyone will be able to get it once more of them are available. To get the vaccine, a person may require to pay a fee. However, some government institutions are providing it free of cost.

In order to get the vaccine, one must check with their local and state health departments on a regular basis. When they get the chance, they must get the dose right away.

The Coronavirus outbreak has challenged the whole world. Constantly, the experts and authorities are working to develop the vaccines. Therefore, we can also do our bit and adopt preventive measures to limit the spread of this disease. The major goal is to get the vaccine to everyone so that we can go on and about with our normal lives.

FAQ on Essay on Coronavirus Vaccine

Question 1: What are some common side effects of the Coronavirus vaccine?

Answer 1: The most common side effect includes a sore arm, fever , headache, and fatigue. However, not to worry, side effects are good in this case. They indicate that your vaccine is starting to work as it triggers your immune system.

Question 2: When do Coronavirus vaccine side effects kick in?

Answer 2: Usually, most of the side effects start to kick in within the first 3 days after you get your vaccine. Moreover, they will last up to 1 to 2 days only.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Persuasive Essay Guide

Persuasive Essay About Covid19

How to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid19 | Examples & Tips

11 min read

People also read

A Comprehensive Guide to Writing an Effective Persuasive Essay

200+ Persuasive Essay Topics to Help You Out

Learn How to Create a Persuasive Essay Outline

30+ Free Persuasive Essay Examples To Get You Started

Read Excellent Examples of Persuasive Essay About Gun Control

Crafting a Convincing Persuasive Essay About Abortion

Learn to Write Persuasive Essay About Business With Examples and Tips

Check Out 12 Persuasive Essay About Online Education Examples

Persuasive Essay About Smoking - Making a Powerful Argument with Examples

Are you looking to write a persuasive essay about the Covid-19 pandemic?

Writing a compelling and informative essay about this global crisis can be challenging. It requires researching the latest information, understanding the facts, and presenting your argument persuasively.

But don’t worry! with some guidance from experts, you’ll be able to write an effective and persuasive essay about Covid-19.

In this blog post, we’ll outline the basics of writing a persuasive essay . We’ll provide clear examples, helpful tips, and essential information for crafting your own persuasive piece on Covid-19.

Read on to get started on your essay.

- 1. Steps to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

- 2. Examples of Persuasive Essay About Covid19

- 3. Examples of Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 Vaccine

- 4. Examples of Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 Integration

- 5. Examples of Argumentative Essay About Covid 19

- 6. Examples of Persuasive Speeches About Covid-19

- 7. Tips to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

- 8. Common Topics for a Persuasive Essay on COVID-19

Steps to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

Here are the steps to help you write a persuasive essay on this topic, along with an example essay:

Step 1: Choose a Specific Thesis Statement

Your thesis statement should clearly state your position on a specific aspect of COVID-19. It should be debatable and clear. For example:

Step 2: Research and Gather Information

Collect reliable and up-to-date information from reputable sources to support your thesis statement. This may include statistics, expert opinions, and scientific studies. For instance:

- COVID-19 vaccination effectiveness data

- Information on vaccine mandates in different countries

- Expert statements from health organizations like the WHO or CDC

Step 3: Outline Your Essay

Create a clear and organized outline to structure your essay. A persuasive essay typically follows this structure:

- Introduction

- Background Information

- Body Paragraphs (with supporting evidence)

- Counterarguments (addressing opposing views)

Step 4: Write the Introduction

In the introduction, grab your reader's attention and present your thesis statement. For example:

Step 5: Provide Background Information

Offer context and background information to help your readers understand the issue better. For instance:

Step 6: Develop Body Paragraphs

Each body paragraph should present a single point or piece of evidence that supports your thesis statement. Use clear topic sentences, evidence, and analysis. Here's an example:

Step 7: Address Counterarguments

Acknowledge opposing viewpoints and refute them with strong counterarguments. This demonstrates that you've considered different perspectives. For example:

Step 8: Write the Conclusion

Summarize your main points and restate your thesis statement in the conclusion. End with a strong call to action or thought-provoking statement. For instance:

Step 9: Revise and Proofread

Edit your essay for clarity, coherence, grammar, and spelling errors. Ensure that your argument flows logically.

Step 10: Cite Your Sources

Include proper citations and a bibliography page to give credit to your sources.

Remember to adjust your approach and arguments based on your target audience and the specific angle you want to take in your persuasive essay about COVID-19.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

Examples of Persuasive Essay About Covid19

When writing a persuasive essay about the Covid-19 pandemic, it’s important to consider how you want to present your argument. To help you get started, here are some example essays for you to read:

Check out some more PDF examples below:

Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 Pandemic

Sample Of Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 In The Philippines - Example

If you're in search of a compelling persuasive essay on business, don't miss out on our “ persuasive essay about business ” blog!

Examples of Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 Vaccine

Covid19 vaccines are one of the ways to prevent the spread of Covid-19, but they have been a source of controversy. Different sides argue about the benefits or dangers of the new vaccines. Whatever your point of view is, writing a persuasive essay about it is a good way of organizing your thoughts and persuading others.

A persuasive essay about the Covid-19 vaccine could consider the benefits of getting vaccinated as well as the potential side effects.

Below are some examples of persuasive essays on getting vaccinated for Covid-19.

Covid19 Vaccine Persuasive Essay

Persuasive Essay on Covid Vaccines

Interested in thought-provoking discussions on abortion? Read our persuasive essay about abortion blog to eplore arguments!

Examples of Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 Integration

Covid19 has drastically changed the way people interact in schools, markets, and workplaces. In short, it has affected all aspects of life. However, people have started to learn to live with Covid19.

Writing a persuasive essay about it shouldn't be stressful. Read the sample essay below to get idea for your own essay about Covid19 integration.

Persuasive Essay About Working From Home During Covid19

Searching for the topic of Online Education? Our persuasive essay about online education is a must-read.

Examples of Argumentative Essay About Covid 19

Covid-19 has been an ever-evolving issue, with new developments and discoveries being made on a daily basis.

Writing an argumentative essay about such an issue is both interesting and challenging. It allows you to evaluate different aspects of the pandemic, as well as consider potential solutions.

Here are some examples of argumentative essays on Covid19.

Argumentative Essay About Covid19 Sample

Argumentative Essay About Covid19 With Introduction Body and Conclusion

Looking for a persuasive take on the topic of smoking? You'll find it all related arguments in out Persuasive Essay About Smoking blog!

Examples of Persuasive Speeches About Covid-19

Do you need to prepare a speech about Covid19 and need examples? We have them for you!

Persuasive speeches about Covid-19 can provide the audience with valuable insights on how to best handle the pandemic. They can be used to advocate for specific changes in policies or simply raise awareness about the virus.

Check out some examples of persuasive speeches on Covid-19:

Persuasive Speech About Covid-19 Example

Persuasive Speech About Vaccine For Covid-19

You can also read persuasive essay examples on other topics to master your persuasive techniques!

Tips to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

Writing a persuasive essay about COVID-19 requires a thoughtful approach to present your arguments effectively.

Here are some tips to help you craft a compelling persuasive essay on this topic:

Choose a Specific Angle

Start by narrowing down your focus. COVID-19 is a broad topic, so selecting a specific aspect or issue related to it will make your essay more persuasive and manageable. For example, you could focus on vaccination, public health measures, the economic impact, or misinformation.

Provide Credible Sources

Support your arguments with credible sources such as scientific studies, government reports, and reputable news outlets. Reliable sources enhance the credibility of your essay.

Use Persuasive Language

Employ persuasive techniques, such as ethos (establishing credibility), pathos (appealing to emotions), and logos (using logic and evidence). Use vivid examples and anecdotes to make your points relatable.

Organize Your Essay

Structure your essay involves creating a persuasive essay outline and establishing a logical flow from one point to the next. Each paragraph should focus on a single point, and transitions between paragraphs should be smooth and logical.

Emphasize Benefits

Highlight the benefits of your proposed actions or viewpoints. Explain how your suggestions can improve public health, safety, or well-being. Make it clear why your audience should support your position.

Use Visuals -H3

Incorporate graphs, charts, and statistics when applicable. Visual aids can reinforce your arguments and make complex data more accessible to your readers.

Call to Action

End your essay with a strong call to action. Encourage your readers to take a specific step or consider your viewpoint. Make it clear what you want them to do or think after reading your essay.

Revise and Edit

Proofread your essay for grammar, spelling, and clarity. Make sure your arguments are well-structured and that your writing flows smoothly.

Seek Feedback

Have someone else read your essay to get feedback. They may offer valuable insights and help you identify areas where your persuasive techniques can be improved.

Tough Essay Due? Hire Tough Writers!

Common Topics for a Persuasive Essay on COVID-19

Here are some persuasive essay topics on COVID-19:

- The Importance of Vaccination Mandates for COVID-19 Control

- Balancing Public Health and Personal Freedom During a Pandemic

- The Economic Impact of Lockdowns vs. Public Health Benefits

- The Role of Misinformation in Fueling Vaccine Hesitancy

- Remote Learning vs. In-Person Education: What's Best for Students?

- The Ethics of Vaccine Distribution: Prioritizing Vulnerable Populations

- The Mental Health Crisis Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic

- The Long-Term Effects of COVID-19 on Healthcare Systems

- Global Cooperation vs. Vaccine Nationalism in Fighting the Pandemic

- The Future of Telemedicine: Expanding Healthcare Access Post-COVID-19

In search of more inspiring topics for your next persuasive essay? Our persuasive essay topics blog has plenty of ideas!

To sum it up,

You have read good sample essays and got some helpful tips. You now have the tools you needed to write a persuasive essay about Covid-19. So don't let the doubts stop you, start writing!

If you need professional writing help, don't worry! We've got that for you as well.

MyPerfectWords.com is a professional essay writing service that can help you craft an excellent persuasive essay on Covid-19. Our experienced essay writer will create a well-structured, insightful paper in no time!

So don't hesitate and get in touch with our persuasive essay writing service today!

Frequently Asked Questions

Are there any ethical considerations when writing a persuasive essay about covid-19.

Yes, there are ethical considerations when writing a persuasive essay about COVID-19. It's essential to ensure the information is accurate, not contribute to misinformation, and be sensitive to the pandemic's impact on individuals and communities. Additionally, respecting diverse viewpoints and emphasizing public health benefits can promote ethical communication.

What impact does COVID-19 have on society?

The impact of COVID-19 on society is far-reaching. It has led to job and economic losses, an increase in stress and mental health disorders, and changes in education systems. It has also had a negative effect on social interactions, as people have been asked to limit their contact with others.

Write Essay Within 60 Seconds!

Caleb S. has been providing writing services for over five years and has a Masters degree from Oxford University. He is an expert in his craft and takes great pride in helping students achieve their academic goals. Caleb is a dedicated professional who always puts his clients first.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

- High contrast

- Press Centre

Search UNICEF

What you need to know about covid-19 vaccines, answers to the most common questions about coronavirus vaccines..

- Available in:

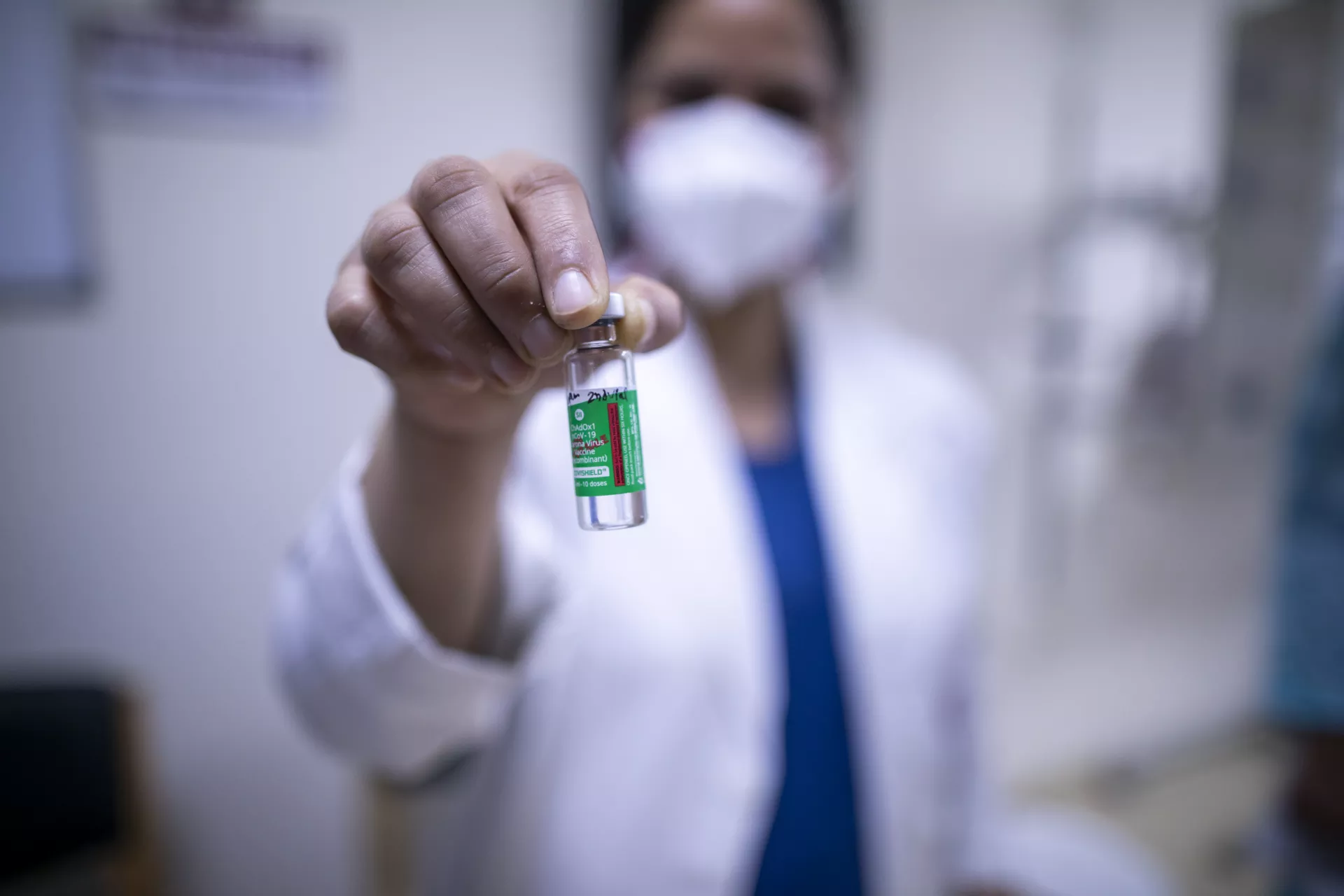

Vaccines save millions of lives each year. The development of safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines are a crucial step in helping us get back to doing more of the things we enjoy with the people we love.

We’ve gathered the latest expert information to answer some of the most common questions about COVID-19 vaccines. Keep checking back as we will update this article as more information becomes available.

What are the benefits of getting vaccinated?

Vaccines save millions of lives each year and a COVID-19 vaccine could save yours. The COVID-19 vaccines are safe and effective, providing strong protection against serious illness and death. WHO reports that unvaccinated people have at least 10 times higher risk of death from COVID-19 than someone who has been vaccinated.

It is important to be vaccinated as soon as it’s your turn, even if you already had COVID-19. Getting vaccinated is a safer way for you to develop immunity from COVID-19 than getting infected.

The COVID-19 vaccines are highly effective, but no vaccine provides 100 per cent protection. Some people will still get ill from COVID-19 after vaccination or pass the virus onto someone else.

Therefore, it is important to continue practicing safety precautions to protect yourself and others, including avoiding crowded spaces, physical distancing, hand washing and wearing a mask.

Who should be vaccinated first?

Each country must identify priority populations, which WHO recommends are frontline health workers (to protect health systems) and those at highest risk of death due to COVID-19, such as older adults and people with certain medical conditions. Other essential workers, such as teachers and social workers, should then be prioritized, followed by additional groups as more vaccine doses become available.

The risk of severe illness from COVID-19 is very low amongst healthy children and adolescents, so unless they are part of a group at higher risk of severe COVID-19, it is less urgent to vaccinate them than these priority groups.

Children and adolescents who are at higher risk of developing severe illness from COVID-19, such as those with underlying illnesses, should be prioritized for COVID-19 vaccines.

When shouldn’t you be vaccinated against COVID-19?

If you have any questions about whether you should receive a COVID-19 vaccine, speak to your healthcare provider. At present, people with the following health conditions should not receive a COVID-19 vaccine to avoid any possible adverse effects:

- If you have a history of severe allergic reactions to any ingredients of a COVID-19 vaccine.

- If you are currently sick or experiencing symptoms of COVID-19 (although you can get vaccinated once you have recovered and your doctor has approved).

Should I get vaccinated if I already had COVID-19?

Yes, you should get vaccinated even if you’ve previously had COVID-19. While people who recover from COVID-19 may develop natural immunity to the virus, it is still not certain how long that immunity lasts or how well it protects you against COVID-19 reinfection. Vaccines offer more reliable protection, especially against severe illness and death. Vaccination policies after COVID-19 infection vary by country. Check with your health care provider on the recommendation where you live.

Which COVID-19 vaccine is best for me?

All WHO-approved vaccines have been shown to be highly effective at protecting you against severe illness and death from COVID-19. The best vaccine to get is the one most readily available to you.

You can find a list of those approved vaccines on WHO’s site .

Remember, if your vaccination involves two doses, it’s important to receive both to have the maximum protection.

How do COVID-19 vaccines work?

Vaccines work by mimicking an infectious agent – viruses, bacteria or other microorganisms that can cause a disease. This ‘teaches’ our immune system to rapidly and effectively respond against it.

Traditionally, vaccines have done this by introducing a weakened form of an infectious agent that allows our immune system to build a memory of it. This way, our immune system can quickly recognize and fight it before it makes us ill. That’s how some of the COVID-19 vaccines have been designed.

Other COVID-19 vaccines have been developed using new approaches, which are called messenger RNA, or mRNA, vaccines. Instead of introducing antigens (a substance that causes your immune system to produce antibodies), mRNA vaccines give our body the genetic code it needs to allow our immune system to produce the antigen itself. mRNA vaccine technology has been studied for several decades. They contain no live virus and do not interfere with human DNA.

For more information on how vaccines work, please visit WHO .

Are COVID-19 vaccines safe?

Yes, COVID-19 vaccines have been safely used to vaccinate billions of people. The COVID-19 vaccines were developed as rapidly as possible, but they had to go through rigorous testing in clinical trials to prove that they meet internationally agreed benchmarks for safety and effectiveness. Only if they meet these standards can a vaccine receive validation from WHO and national regulatory agencies.

UNICEF only procures and supplies COVID-19 vaccines that meet WHO’s established safety and efficacy criteria and that have received the required regulatory approval.

How were COVID-19 vaccines developed so quickly?

Scientists were able to develop safe effective vaccines in a relatively short amount of time due to a combination of factors that allowed them to scale up research and production without compromising safety:

- Because of the global pandemic, there was a larger sample size to study and tens of thousands of volunteers stepped forward

- Advancements in technology (like mRNA vaccines) that were years in the making

- Governments and other bodies came together to remove the obstacle of funding research and development

- Manufacturing of the vaccines occurred in parallel to the clinical trials to speed up production

Though they were developed quickly, all COVID-19 vaccines approved for use by the WHO are safe and effective.

What are the side effects of COVID-19 vaccines?

Vaccines are designed to give you immunity without the dangers of getting the disease. Not everyone does, but it’s common to experience some mild-to-moderate side effects that go away within a few days on their own.

Some of the mild-to-moderate side effects you may experience after vaccination include:

- Arm soreness at the injection site

- Muscle or joint aches

You can manage any side effects with rest, staying hydrated and taking medication to manage pain and fever, if needed.

If any symptoms continue for more than a few days then contact your healthcare provider for advice. More serious side effects are extremely rare, but if you experience a more severe reaction, then contact your healthcare provider immediately.

>> Read: What you need to know before, during and after receiving a COVID-19 vaccine

How do I find out more about a particular COVID-19 vaccine?

You can find out more about COVID-19 vaccines on WHO’s website .

Can I stop taking precautions after being vaccinated?

Keep taking precautions to protect yourself, family and friends if there is still COVID-19 in your area, even after getting vaccinated. The COVID-19 vaccines are highly effective against serious illness and death, but no vaccine is 100% effective.

The vaccines offer less protection against infection from the Omicron variant, which is now the dominant variant globally, but remain highly effective in preventing hospitalization, severe disease, and death. In addition to vaccination, it remains important to continue practicing safety precautions to protect yourself and others. These precautions include avoiding crowded spaces, physical distancing, hand washing, and wearing a mask (as per local policies).

Can I still get COVID-19 after I have been vaccinated? What are ‘breakthrough cases’?

A number of vaccinated people may get infected with COVID-19, which is called a breakthrough infection. In such cases, people are much more likely to only have milder symptoms. Vaccine protection against serious illness and death remains strong.

With more infectious virus variants such as Omicron, there have been more breakthrough infections. That’s why it's recommended to continue taking precautions such as avoiding crowded spaces, wearing a mask and washing your hands regularly, even if you are vaccinated.

And remember, it’s important to receive all of the recommended doses of vaccines to have the maximum protection.

How long does protection from COVID-19 vaccines last?

According to WHO, the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines wanes around 4-6 months after the primary series of vaccination has been completed. Taking a booster to strengthen your protection against serious disease is recommended if it is available to you.

Do the COVID-19 vaccines protect against variants?

The WHO-approved COVID-19 vaccines continue to be highly effective at preventing severe illness and death.

However, the vaccines offer less protection against infection from Omicron, which is the dominant variant globally. That's why it's important to get vaccinated and continue measures to reduce the spread of the virus – which helps to reduce the chances for the virus to mutate – including physical distancing, mask wearing, good ventilation, regular handwashing and seeking care early if you have symptoms.

Do I need to get a booster shot?

Booster doses play an important role in protecting against severe disease, hospitalization and death.

WHO recommends that you take all COVID-19 vaccine doses recommended to you by your health authority as soon as it is your turn, including a booster dose if recommended.

Booster shots should be given first to high priority groups. Data shows that a booster shot plays a significant role in boosting waning immunity and protecting against severe disease from highly transmissible variants like Omicron.

If available, an additional second booster shot is also recommended for some groups of people, 4-6 months after the first booster. That includes older people, those who have weakened immune systems, pregnant women and healthcare workers.

Check with your local health authorities for guidance and the availability of booster shots where you live.

What do we know about the bivalent COVID-19 booster doses that have been developed to target Omicron?

Bivalent COVID-19 booster shots have now been developed with both the original strain of the coronavirus and a strain of Omicron. These have been designed to better match the Omicron subvariants that have proven to be particularly transmissible. Lab studies have shown that these doses help you to mount a higher antibody response against Omicron. Both Moderna and Pfizer have developed these bivalent vaccines, and some countries have now approved their use.

Check with your local health authorities for information about the availability of these doses and who can get them where you live. And it’s important to note that the original COVID-19 vaccines continue to work very well and provide strong protection against severe illness from Omicron.

Can I receive different types of COVID-19 vaccines?

Yes, however, policies on mixing vaccines vary by country. Some countries have used different vaccines for the primary vaccine series and the booster. Check with your local health authorities for guidance where you live and speak with your healthcare provider if you have any questions on what is best for you.

I’m pregnant. Can I get vaccinated against COVID-19?

Yes, you can get vaccinated if you are pregnant. COVID-19 during pregnancy puts you at higher risk of becoming severely ill and of giving birth prematurely.

Many people around the world have been vaccinated against COVID-19 while pregnant or breastfeeding. No safety concerns have been identified for them or their babies. Getting vaccinated while pregnant helps to protect your baby. For more information about receiving a COVID-19 vaccination while pregnant, speak to your healthcare provider.

>> Read: Navigating pregnancy during the COVID-19 pandemic

I’m breastfeeding. Should I get vaccinated against COVID-19?

Yes, if you are breastfeeding you should take the vaccine as soon as it is available to you. It is very safe and there is no risk to the mother or baby. None of the current COVID-19 vaccines have live virus in them, so there is no risk of you transmitting COVID-19 to your baby through your breastmilk from the vaccine. In fact, the antibodies that you have after vaccination may go through the breast milk and help protect your baby. >> Read: Breastfeeding safely during the COVID-19 pandemic

Can COVID-19 vaccines affect fertility?

No, you may have seen false claims on social media, but there is no evidence that any vaccine, including COVID-19 vaccines, can affect fertility in women or men. You should get vaccinated if you are currently trying to become pregnant.

Could a COVID-19 vaccine disrupt my menstrual cycle?

Some people have reported experiencing a disruption to their menstrual cycle after getting vaccinated against COVID-19. Although data is still limited, research is ongoing into the impact of vaccines on menstrual cycles.

Speak to your healthcare provider if you have concerns or questions about your periods.

Should my child or teen get a COVID-19 vaccine?

An increasing number of vaccines have been approved for use in children. They’ve been made available after examining the data on the safety and efficacy of these vaccines, and millions of children have been safely vaccinated around the world. Some COVID-19 vaccines have been approved for children from the age of 6 months old. Check with your local health authorities on what vaccines are authorized and available for children and adolescents where you live.

Children and adolescents tend to have milder disease compared to adults, so unless they are part of a group at higher risk of severe COVID-19, it is less urgent to vaccinate them than older people, those with chronic health conditions and health workers.

Remind your children of the importance of us all taking precautions to protect each other, such as avoiding crowded spaces, physical distancing, hand washing and wearing a mask.

It is critical that children continue to receive the recommended childhood vaccines.

How do I talk to my kids about COVID-19 vaccines?

News about COVID-19 vaccines is flooding our daily lives and it is only natural that curious young minds will have questions – lots of them. Read our explainer article for help explaining what can be a complicated topic in simple and reassuring terms.

It’s important to note that from the millions of children that have so far been vaccinated against COVID-19 globally, we know that side effects are very rare. Just like adults, children and adolescents might experience mild symptoms after receiving a dose, such as a slight fever and body aches. But these symptoms typically last for just a day or two. The authorized vaccines for adolescents and children are very safe.

My friend or family member is against COVID-19 vaccines. How do I talk to them?

The development of safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines is a huge step forward in our global effort to end the pandemic. This is exciting news, but there are still some people who are skeptical or hesitant about COVID-19 vaccines. Chances are you know a person who falls into this category.

We spoke to Dr. Saad Omer, Director at the Yale Institute for Global Health, to get his tips on how to navigate these challenging conversations. >> Read the interview

How can I protect my family until we are all vaccinated?

Safe and effective vaccines are a game changer, but even once vaccinated we need to continue taking precautions for the time being to protect ourselves and others. Variants like Omicron have proven that although COVID-19 vaccines are very effective at preventing severe disease, they’re not enough to stop the spread of the virus alone. The most important thing you can do is reduce your risk of exposure to the virus. To protect yourself and your loved ones, make sure to:

- Wear a mask where physical distancing from others is not possible.

- Keep a physical distance from others in public places.

- Avoid poorly ventilated or crowded spaces.

- Open windows to improve ventilation indoors.

- Try and focus on outdoor activities if possible.

- Wash your hands regularly with soap and water or an alcohol-based hand rub.

If you or a family member has a fever, cough or difficulty breathing, seek medical care early and avoid mixing with other children and adults.

Can COVID-19 vaccines affect your DNA?

No, none of the COVID-19 vaccines affect or interact with your DNA in any way. Messenger RNA, or mRNA, vaccines teach the cells how to make a protein that triggers an immune response inside the body. This response produces antibodies which keep you protected against the virus. mRNA is different from DNA and only stays inside the cell for about 72 hours before degrading. However, it never enters the nucleus of the cell, where DNA is kept.

Do the COVID-19 vaccines contain any animal products in them?

No, none of the WHO-approved COVID-19 vaccines contain animal products.

I’ve seen inaccurate information online about COVID-19 vaccines. What should I do?

Sadly, there is a lot of inaccurate information online about the COVID-19 virus and vaccines. A lot of what we’re experiencing is new to all of us, so there may be some occasions where information is shared, in a non-malicious way, that turns out to be inaccurate.

Misinformation in a health crisis can spread paranoia, fear and stigmatization. It can also result in people being left unprotected or more vulnerable to the virus. Get verified facts and advice from trusted sources like your local health authority, the UN, UNICEF, WHO.

If you see content online that you believe to be false or misleading, you can help stop it spreading by reporting it to the social media platform.

What is COVAX?

COVAX is a global effort committed to the development, production and equitable distribution of vaccines around the world. No country will be safe from COVID-19 until all countries are protected.

There are 190 countries and territories engaged in the COVAX Facility, which account for over 90 per cent of the world’s population. Working with CEPI, GAVI, WHO and other partners, UNICEF is leading efforts to procure and supply COVID-19 vaccines on behalf of COVAX.

Learn more about COVAX .

This article was last updated on 25 October 2022. It will continue to be updated to reflect the latest information.

Related topics

More to explore, covid-19 response.

Resources and information about UNICEF’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic

How to talk to your children about COVID-19 vaccines

Tips for navigating the conversation

How to talk to friends and family about vaccines

Tips for handling tough conversations with your loved ones

COVAX information centre

UNICEF and partners led the largest vaccine procurement and supply operation in history

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 14 May 2021

Public attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination: The role of vaccine attributes, incentives, and misinformation

- Sarah Kreps 1 ,

- Nabarun Dasgupta 2 ,

- John S. Brownstein 3 , 4 ,

- Yulin Hswen 5 &

- Douglas L. Kriner ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9353-2334 1

npj Vaccines volume 6 , Article number: 73 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

19k Accesses

72 Citations

43 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Health care

- Translational research

While efficacious vaccines have been developed to inoculate against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2; also known as COVID-19), public vaccine hesitancy could still undermine efforts to combat the pandemic. Employing a survey of 1096 adult Americans recruited via the Lucid platform, we examined the relationships between vaccine attributes, proposed policy interventions such as financial incentives, and misinformation on public vaccination preferences. Higher degrees of vaccine efficacy significantly increased individuals’ willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, while a high incidence of minor side effects, a co-pay, and Emergency Use Authorization to fast-track the vaccine decreased willingness. The vaccine manufacturer had no influence on public willingness to vaccinate. We also found no evidence that belief in misinformation about COVID-19 treatments was positively associated with vaccine hesitancy. The findings have implications for public health strategies intending to increase levels of community vaccination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Measuring the impact of COVID-19 vaccine misinformation on vaccination intent in the UK and USA

Sahil Loomba, Alexandre de Figueiredo, … Heidi J. Larson

Vaccine hesitancy and monetary incentives

Ganesh Iyer, Vivek Nandur & David Soberman

Providing normative information increases intentions to accept a COVID-19 vaccine

Alex Moehring, Avinash Collis, … Dean Eckles

Introduction

In less than a year, an array of vaccines was developed to bring an end to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. As impressive as the speed of development was the efficacy of vaccines such as Moderna and Pfizer, which are over 90%. Despite the growing availability and efficacy, however, vaccine hesitancy remains a potential impediment to widespread community uptake. While previous surveys indicate that overall levels of vaccine acceptance may be around 70% in the United States 1 , the case of Israel may offer a cautionary tale about self-reported preferences and vaccination in practice. Prospective studies 2 of vaccine acceptance in Israel showed that about 75% of the Israeli population would vaccinate, but Israel’s initial vaccination surge stalled around 42%. The government, which then augmented its vaccination efforts with incentive programs, attributed unexpected resistance to online misinformation 3 .

Research on vaccine hesitancy in the context of viruses such as influenza and measles, mumps, and rubella, suggests that misinformation surrounding vaccines is prevalent 4 , 5 . Emerging research on COVID-19 vaccine preferences, however, points to vaccine attributes as dominant determinants of attitudes toward vaccination. Higher efficacy is associated with greater likelihood of vaccinating 6 , 7 , whereas an FDA Emergency Use Authorization 6 or politicized approval timing 8 is associated with more hesitancy. Whether COVID-19 misinformation contributes to vaccine preferences or whether these attributes or policy interventions such as incentives play a larger role has not been studied. Further, while previous research has focused on a set of attributes that was relevant at one particular point in time, the evidence and context about the available vaccines has continued to shift in ways that could shape public willingness to accept the vaccine. For example, governments, employers, and economists have begun to think about or even devise ways to incentivize monetarily COVID-19 vaccine uptake, but researchers have not yet studied whether paying people to receive the COVID-19 vaccine would actually affect likely behavior. As supply problems wane and hesitancy becomes a limiting factor, understanding whether financial incentives can overcome hesitancy becomes a crucial question for public health. Further, as new vaccines such as Johnson and Johnson are authorized, knowing whether the vaccine manufacturer name elicits or deters interest in individuals is also important, as are the corresponding efficacy rates of different vaccines and the extent to which those affect vaccine preferences. The purpose of this study is to examine how information about vaccine attributes such as efficacy rates, the incidence of side effects, the nature of the governmental approval process, identity of the manufacturers, and policy interventions, including economic incentives, affect intention to vaccinate, and to examine the association between belief in an important category of misinformation—false claims concerning COVID-19 treatments—and willingness to vaccinate.

General characteristics of study population

Table 1 presents sample demographics, which largely reflect those of the US population as a whole. Of the 1335 US adults recruited for the study, a convenience sample of 1100 participants consented to begin the survey, and 1096 completed the full questionnaire. The sample was 51% female; 75% white; and had a median age of 43 with an interquartile range of 31–58. Comparisons of the sample demographics to those of other prominent social science surveys and U.S. Census figures are shown in Supplementary Table 1 .

Vaccination preferences

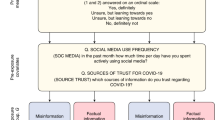

Each subject was asked to evaluate a series of seven hypothetical vaccines. For each hypothetical vaccine, our conjoint experiment randomly assigned values of five different vaccine attributes—efficacy, the incidence of minor side effects, government approval process, manufacturer, and cost/financial inducement. Descriptions of each attribute and the specific levels used in the experiment are summarized in Table 2 . After seeing the profile of each vaccine, the subject was asked whether she would choose to receive the vaccine described, or whether she would choose not to be vaccinated. Finally, subjects were asked to indicate how likely they would be to take the vaccine on a seven-point likert scale.

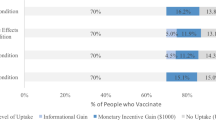

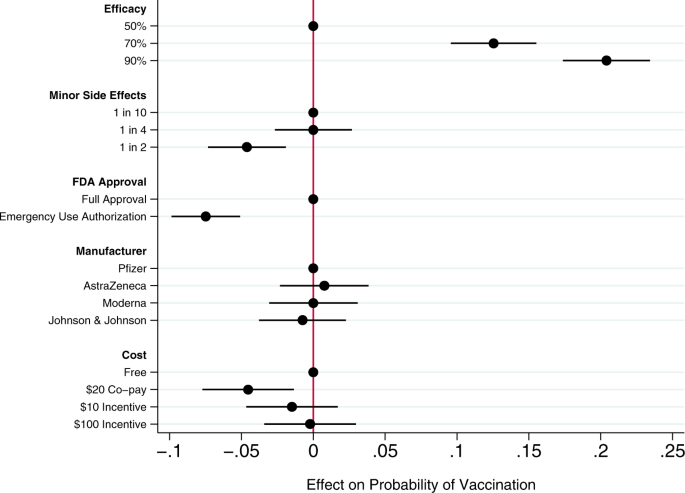

Across all choice sets, in 4419 cases (58%) subjects said they would choose the vaccine described in the profile rather than not being vaccinated. As shown in Fig. 1 , several characteristics of the vaccine significantly influenced willingness to vaccinate.

Circles present the estimated effect of each attribute level on the probability of a subject accepting vaccination from the attribute’s baseline level. Horizontal lines through points indicate 95% confidence intervals. Points without error bars denote the baseline value for each attribute. The average marginal component effects (AMCEs) are the regression coefficients reported in model 1 of Table 3 .

Efficacy had the largest effect on individual vaccine preferences. An efficacy rate of 90% increased uptake by about 20% relative to the baseline at 50% efficacy. Even a high incidence of minor side effects (1 in 2) had only a modest negative effect (about 5%) on willingness to vaccinate. Whether the vaccine went through full FDA approval or received an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA), an authority that allows the Food and Drug Administration mechanisms to accelerate the availability and use of treatments or medicines during medical emergencies 9 , significantly influenced willingness to vaccinate. An EUA decreased the likelihood of vaccination by 7% compared to a full FDA authorization; such a decline would translate into about 23 million Americans. While a $20 co-pay reduced the likelihood of vaccination relative to a no-cost baseline, financial incentives did not increase willingness to vaccinate. Lastly, the manufacturer had no effect on vaccination attitudes, despite the public pause of the AstraZeneca trial and prominence of Johnson & Johnson as a household name (our experiment was fielded before the pause in the administration of the Johnson & Johnson shot in the United States).

Model 2 of Table 3 presents an expanded model specification to investigate the association between misinformation and willingness to vaccinate. The primary additional independent variable of interest is a misinformation index that captures the extent to which each subject believes or rejects eight claims (five false; three true) about COVID-19 treatments. Additional analyses using alternate operationalizations of the misinformation index yield substantively similar results (Supplementary Table 4 ). This model also includes a number of demographic control variables, including indicators for political partisanship, gender, educational attainment, age, and race/ethnicity, all of which are also associated with belief in misinformation about the vaccine (Supplementary Table 2 ). Finally, the model also controls for subjects’ health insurance status, past experience vaccinating against seasonal influenza, attitudes toward the pharmaceutical industry, and beliefs about vaccine safety generally.

Greater levels of belief in misinformation about COVID-19 treatments were not associated with greater vaccine hesitancy. Instead, the relevant coefficient is positive and statistically significant, indicating that, all else being equal, individuals who scored higher on our index of misinformation about COVID-19 treatments were more willing to vaccinate than those who were less susceptible to believing false claims.

Strong beliefs that vaccines are safe generally was positively associated with willingness to accept a COVID-19 vaccine, as were past histories of frequent influenza vaccination and favorable attitudes toward the pharmaceutical industry. Women and older subjects were significantly less likely to report willingness to vaccinate than men and younger subjects, all else equal. Education was positively associated with willingness to vaccinate.

This research offers a comprehensive examination of attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination, particularly the role of vaccine attributes, potential policy interventions, and misinformation. Several previous studies have analyzed the effects of vaccine characteristics on willingness to vaccinate, but the modal approach is to gauge willingness to accept a generic COVID-19 vaccine 10 , 11 . Large volumes of research show, however, that vaccine preferences hinge on specific vaccine attributes. Recent research considering the influence of attributes such as efficacy, side effects, and country of origin take a step toward understanding how properties affect individuals’ intentions to vaccinate 6 , 7 , 8 , 12 , 13 , but evidence about the attributes of actual vaccines, debates about how to promote vaccination within the population, and questions about the influence of misinformation have moved quickly 14 .

Our conjoint experiment therefore examined the influence of five vaccine attributes on vaccination willingness. The first category of attributes involved aspects of the vaccine itself. Since efficacy is one of the most common determinants of vaccine acceptance, we considered different levels of efficacy, 50%, 70%, and 90%, levels that are common in the literature 7 , 15 . Evidence from Phase III trials suggests that even the 90% efficacy level in our design, which is well above the 50% threshold from the FDA Guidance for minimal effectiveness for Emergency Use Authorization 16 , has been exceeded by both Pfizer’s and Moderna’s vaccines 17 , 18 . The 70% efficacy threshold is closer to the initial reports of the efficacy of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, whose efficacy varied across regions 19 . Our analysis suggests that efficacy levels associated with recent mRNA vaccine trials increases public vaccine uptake by 20% over a baseline of a vaccine with 50% efficacy. A 70% efficacy rate increases public willingness to vaccinate by 13% over a baseline vaccine with 50% efficacy.

An additional set of epidemiological attributes consisted of the frequency of minor side effects. While severe side effects were plausible going into early clinical trials, evidence clearly suggests that minor side effects are more common, ranging from 10% to 100% of people vaccinated depending on the number of doses and the dose group (25–250 mcg) 20 . Since the 100 mcg dose was supported in Phase III trials 21 , we include the highest adverse event probability—approximating 60% as 1 in 2—and 1 in 10 as the lowest likelihood, approximating the number of people who experienced mild arthralgia 20 . Our findings suggest that a the prevalence of minor side effects associated with recent trials (i.e. a 1 in 2 chance), intention to vaccinate decreased by about 5% versus a 1 in 10 chance of minor side effects baseline. However, at a 25% rate of minor side effects, respondents did not indicate any lower likelihood of vaccination compared to the 10% baseline. Public communications about how to reduce well-known side effects, such as pain at the injection site, could contribute to improved acceptance of the vaccine, as it is unlikely that development of vaccine-related minor side effects will change.

We then considered the effect of EUA versus full FDA approval. The influenza H1N1 virus brought the process of EUA into public discourse 22 , and the COVID-19 virus has again raised the debate about whether and how to use EUA. Compared to recent studies also employing conjoint experimental designs that showed just a 3% decline in support conditional on EUA 6 , we found decreases in support of more than twice that with an EUA compared to full FDA approval. Statements made by the Trump administration promising an intensely rapid roll-out or isolated adverse events from vaccination in the UK may have exacerbated concerns about EUA versus full approval 8 , 23 , 24 , 25 . This negative effect is even greater among some subsets of the population. As shown in additional analyses reported in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Fig. 5 ), the negative effects are greatest among those who believe vaccines are generally safe. Among those who believe vaccines generally are extremely safe, the EUA decreased willingness to vaccinate by 11%, all else equal. This suggests that outreach campaigns seeking to assure those troubled by the authorization process used for currently available vaccines should target their efforts on those who are generally predisposed to believe vaccines are safe.

Next, we compared receptiveness as a function of the manufacturer: Moderna, Pfizer, Johnson and Johnson, and AstraZeneca, all firms at advanced stages of vaccine development. Vaccine manufacturers in the US have not yet attempted to use trade names to differentiate their vaccines, instead relying on the association with manufacturer reputation. In other countries, vaccine brand names have been more intentionally publicized, such as Bharat Biotech’s Covaxin in India and Gamaleya Research Institute of Epidemiology and Microbiology Sputnik V in Russia. We found that manufacturer names had no impact on willingness to vaccinate. As with hepatitis and H. influenzae vaccines 26 , 27 , interchangeability has been an active topic of debate with coronavirus mRNA vaccines which require a second shot for full immunity. Our research suggests that at least as far as public receptiveness goes, interchangeability would not introduce concerns. We found no significant differences in vaccination uptake across any of the manufacturer treatments. Future research should investigate if a manufacturer preference develops as new evidence about efficacy and side effects becomes available, particularly depending on whether future booster shots, if needed, are deemed interchangeable with the initial vaccination.

Taking up the question of how cost and financial incentives shape behavior, we looked at paying and being paid to vaccinate. While existing research suggests that individuals are often willing to pay for vaccines 28 , 29 , some economists have proposed that the government pay individuals up to $1,000 to take the COVID-19 vaccine 30 . However, because a cost of $300 billion to vaccinate the population may be prohibitive, we posed a more modest $100 incentive. We also compared this with a $10 incentive, which previous studies suggest is sufficient for actions that do not require individuals to change behavior on a sustained basis 31 . While having to pay a $20 co-pay for the vaccine did deter individuals, the additional economic incentives had no positive effect although they did not discourage vaccination 32 . Consistent with past research 31 , 33 , further analysis shows that the negative effect of the $20 co-pay was concentrated among low-income earners (Supplementary Fig. 7 ). Financial incentives failed to increase vaccination willingness across income levels.

Our study also yields important insights into the relationship between one prominent category of COVID-19 misinformation and vaccination preferences. We find that susceptibility to misinformation about COVID-19 treatments—based on whether individuals can distinguish between factual and false information about efforts to combat COVID-19—is considerable. A quarter of subjects scored no higher on our misinformation index than random guessing or uniform abstention/unsure responses (for the full distribution, see Supplementary Fig. 2 ). However, subjects who scored higher on our misinformation index did not exhibit greater vaccination hesitancy. These subjects actually were more likely to believe in vaccine safety more generally and to accept a COVID-19 vaccine, all else being equal. These results run counter to recent findings of public opinion in France where greater conspiracy beliefs were negatively correlated with willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19 34 and in Korea where greater misinformation exposure and belief were negatively correlated with taking preventative actions 35 . Nevertheless, the results are robust to alternate operationalizations of belief in misinformation (i.e., constructing the index only using false claims, or measuring misinformation beliefs as the number of false claims believed: see Supplementary Table 4 ).

We recommend further study to understand the observed positive relationship between beliefs in COVID-19 misinformation about fake treatments and willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. To be clear, we do not posit a causal relationship between the two. Rather, we suspect that belief in misinformation may be correlated with an omitted factor related to concerns about contracting COVID-19. For example, those who believe COVID-19 misinformation may have a higher perception of risk of COVID-19, and therefore be more willing to take a vaccine, all else equal 36 . Additional analyses reported in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Fig. 6 ) show that the negative effect of an EUA on willingness to vaccinate was concentrated among those who scored low on the misinformation index. An EUA had little effect on the vaccination preferences of subjects most susceptible to misinformation. This pattern is consistent with the possibility that these subjects were more concerned with the disease and therefore more likely to vaccinate, regardless of the process through which the vaccine was brought to market.

We also observe that skepticism toward vaccines in general does not correlate perfectly with skepticism toward the COVID-19 vaccine. Therefore, it is important not to conflate people who are wary of the COVID-19 vaccine and those who are anti-vaccination, as even medically informed individuals may be hesitant because of the speed at which the COVID-19 vaccine was developed. For example, older people are more likely to believe vaccines are safe but less willing to receive the COVID-19 vaccine in our survey, perhaps following the high rates of vaccine skepticism among medical staff expressing concerns regarding the safety of a rapidly-developed vaccine 2 . This inverse relationship between age and willingness to vaccinate is also surprising. Most opinion surveys find older adults are more likely to vaccinate than younger adults 37 . However, most of these survey questions ask about willingness to take a generic vaccine. Two prior studies, both recruiting subjects from the Lucid platform and employing conjoint experiments to examine the effects of vaccine attributes on public willingness to vaccinate, also find greater vaccine hesitancy among older Americans 6 , 7 . Future research could explore whether these divergent results are a product of the characteristics of the sample or of the methodological design in which subjects have much more information about the vaccines when indicating their vaccination preferences.

An important limitation of our study is that it necessarily offers a snapshot in time, specifically prior to both the election and vaccine roll-out. We recommend further study to understand more how vaccine perceptions evolve both in terms of the perceived political ownership of the vaccine—now that President Biden is in office—and as evidence has emerged from the millions of people who have been vaccinated. Similarly, researchers should consider analyzing vaccine preferences in the context of online vaccine controversies that have been framed in terms of patient autonomy and right to refuse 38 , 39 . Vaccination mandates may evoke feelings of powerlessness, which may be exacerbated by misinformation about the vaccines themselves. Further, researchers should more fully consider how individual attributes such as political ideology and race intersect with vaccine preferences. Our study registered increased vaccine hesitancy among Blacks, but did not find that skepticism was directly related to misinformation. Perceptions and realities of race-based maltreatment could also be moderating factors worth exploring in future analyses 40 , 41 .

Overall, we found that the most important factor influencing vaccine preferences is vaccine efficacy, consistent with a number of previous studies about attitudes toward a range of vaccines 6 , 42 , 43 . Other attributes offer potential cautionary flags and opportunities for public outreach. The prospect of a 50% likelihood of mild side effects, consistent with the evidence about current COVID-19 vaccines being employed, dampens likelihood of uptake. Public health officials should reinforce the relatively mild nature of the side effects—pain at the injection site and fatigue being the most common 44 —and especially the temporary nature of these effects to assuage public concerns. Additionally, in considering policy interventions, public health authorities should recognize that a $20 co-pay will likely discourage uptake while financial incentives are unlikely to have a significant positive effect. Lastly, belief in misinformation about COVID-19 does not appear to be a strong predictor of vaccine hesitancy; belief in misinformation and willingness to vaccinate were positively correlated in our data. Future research should explore the possibility that exposure to and belief in misinformation is correlated with other factors associated with vaccine preferences.

Survey sample and procedures

This study was approved by the Cornell Institutional Review Board for Human Participant Research (protocol ID 2004009569). We conducted the study on October 29–30, 2020, prior to vaccine approval, which means we captured sentiments prospectively rather than based on information emerging from an ongoing vaccination campaign. We recruited a sample of 1096 adult Americans via the Lucid platform, which uses quota sampling to produce samples matched to the demographics of the U.S. population on age, gender, ethnicity, and geographic region. Research has shown that experimental effects observed in Lucid samples largely mirror those found using probability-based samples 45 . Supplementary Table 1 presents the demographics of our sample and comparisons to both the U.S. Census American Community Survey and the demographics of prominent social science surveys.

After providing informed consent on the first screen of the online survey, participants turned to a choice-based conjoint experiment that varied five attributes of the COVID-19 vaccine. Conjoint analyses are often used in marketing to research how different aspects of a product or service affect consumer choice. We build on public health studies that have analyzed the influence of vaccine characteristics on uptake within the population 42 , 46 .

Conjoint experiment

We first designed a choice-based conjoint experiment that allowed us to evaluate the relative influence of a range of vaccine attributes on respondents’ vaccine preferences. We examined five attributes summarized in Table 2 . Past research has shown that the first two attributes, efficacy and the incidence of side effects, are significant drivers of public preferences on a range of vaccines 47 , 48 , 49 , including COVID-19 6 , 7 , 13 , 50 . In this study, we increased the expected incidence of minor side effects from previous research 6 to reflect emerging evidence from Phase III trials. The third attribute, whether the vaccine received full FDA approval or an EUA, examines whether the speed of the approval process affects public vaccination preferences 6 . The fourth attribute, the manufacturer of the vaccine, allows us to examine whether the highly public pause in the AstraZeneca trial following an adverse event, and the significant differences in brand familiarity between smaller and less broadly known companies like Moderna and household name Johnson & Johnson affects public willingness to vaccinate. The fifth attribute examines the influence of a policy tool—offsetting the costs of vaccination or even incentivizing it financially—on public willingness to vaccinate.

Attribute levels and attribute order were randomly assigned across participants. A sample choice set is presented in Supplementary Fig. 1 . After viewing each profile individually, subjects were asked: “If you had to choose, would you choose to get this vaccine, or would you choose not to be vaccinated?” Subjects then made a binary choice, responding either that they “would choose to get this vaccine” or that they “would choose not to be vaccinated.” This is the dependent variable for the regression analyses in Table 3 . After making a binary choice to take the vaccine or not be vaccinated, we also asked subjects “how likely or unlikely would you be to get the vaccine described above?” Subjects indicated their vaccination preference on a seven-point scale ranging from “extremely likely” to “extremely unlikely.” Additional analyses using this ordinal dependent variable reported in Supplementary Table 3 yield substantively similar results to those presented in Table 3 .

To determine the effect of each attribute-level on willingness to vaccinate, we followed Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto and employed an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression with standard errors clustered on respondent to estimate the average marginal component effects (AMCEs) for each attribute 51 . The AMCE represents the average difference in a subject choosing a vaccine when comparing two different attribute values—for example, 50% efficacy vs. 90% efficacy—averaged across all possible combinations of the other vaccine attribute values. The AMCEs are nonparametrically identified under a modest set of assumptions, many of which (such as randomization of attribute levels) are guaranteed by design. Model 1 in Table 3 estimates the AMCEs for each attribute. These AMCEs are illustrated in Fig. 1 .

Analyzing additional correlates of vaccine acceptance

To explore the association between respondents’ embrace of misinformation about COVID-19 treatments and vaccination willingness, the survey included an additional question battery. To measure the extent of belief in COVID-19 misinformation, we constructed a list of both accurate and inaccurate headlines about the coronavirus. We focused on treatments, relying on the World Health Organization’s list of myths, such as “Hand dryers are effective in killing the new coronavirus” and true headlines such as “Avoiding shaking hands can help limit the spread of the new coronavirus 52 .” Complete wording for each claim is provided in Supplementary Appendix 1 . Individuals read three true headlines and five myths, and then responded whether they believed each headline was true or false, or whether they were unsure. We coded responses to each headline so that an incorrect accuracy assessment yielded a 1; a correct accuracy assessment a -1; and a response of unsure was coded as 0. From this, we created an additive index of belief in misinformation that ranged from -8 to 8. The distribution of the misinformation index is presented in Supplementary Fig. 2 . A possible limitation of this measure is that because the survey was conducted online, some individuals could have searched for the answers to the questions before responding. However, the median misinformation index score for subjects in the top quartile in terms of time spent taking the survey was identical to the median for all other respondents. This may suggest that systematic searching for correct answers is unlikely.

To ensure that any association observed between belief in misinformation and willingness to vaccinate is not an artifact of how we operationalized susceptibility to misinformation, we also constructed two alternate measures of belief in misinformation. These measures are described in detail in the Supplementary Information (see Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4 ). Additional regression analyses using these alternate measures of misinformation beliefs yield substantively similar results (see Supplementary Table 4 ). Additional analyses examining whether belief in misinformation moderates the effect of efficacy and an FDA EUA on vaccine acceptance are presented in Supplementary Fig. 6 .

Finally, model 2 of Table 3 includes a range of additional control variables. Following past research, it includes a number of demographic variables, including indicator variables identifying subjects who identify as Democrats or Republicans; an indicator variable identifying females; a continuous variable measuring age (alternate analyses employing a categorical variable yield substantively similar results); an eight-point measure of educational attainment; and indicator variables identifying subjects who self-identify as Black or Latinx. Following previous research 6 , the model also controlled for three additional factors often associated with willingness to vaccinate: an indicator variable identifying whether each subject had health insurance; a variable measuring past frequency of influenza vaccination on a four-point scale ranging from “never” to “every year”; beliefs about the general safety of vaccines measured on a four-point scale ranging from “not at all safe” to “extremely safe”; and a measure of attitudes toward the pharmaceutical industry ranging from “very positive” to “very negative.”

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data and statistical code to reproduce the tables and figures in the manuscript and Supplementary Information are published at the Harvard Dataverse via this link: 10.7910/DVN/ZYU6CO.

Hamel, L., Kirzinger, A., Munana, C. & Brodie, M. KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: December 2020 | KFF (2020).

Dror, A. A. et al. Vaccine hesitancy: the next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 35 , 775–779 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Scharf, I. & Ben Zion, I. As Vaccinations Lag, Israel Combats Online Misinformation. AP2 (21AD).

Nyhan, B. & Reifler, J. Does correcting myths about the flu vaccine work? An experimental evaluation of the effects of corrective information. Vaccine 33 , 459–464 (2015).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Hussain, A., Ali, S., Ahmed, M. & Hussain, S. The anti-vaccination movement: a regression in modern medicine. Cureus 10 , e2919 (2018).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kreps, S. et al. Factors Associated With US Adults’ Likelihood of Accepting COVID-19 Vaccination. JAMA Netw. open 3 , (2020).

Motta, M. Can a COVID-19 vaccine live up to Americans’ expectations? A conjoint analysis of how vaccine characteristics influence vaccination intentions. Soc. Sci. Med . 113642, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113642 (2021).

Bokemper, S. E., Huber, G. A., Gerber, A. S., James, E. K. & Omer, S. B. Timing of COVID-19 vaccine approval and endorsement by public figures. Vaccine , https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.12.048 (2021).

Quinn, S. C., Jamison, A. M. & Freimuth, V. Communicating effectively about emergency use authorization and vaccines in the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Public Health e1–e4 (2020).

Malik, A. A., McFadden, S. A. M., Elharake, J. & Omer, S. B. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. EClinicalMedicine 26 , 100495 (2020).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Fisher, K. A. et al. Attitudes toward a potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: a survey of U.S. adults. Ann. Intern. Med. 173 , 964–973 (2020).

Lazarus, J. V. et al . A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat. Med . 1–4 (2020).

Schwarzinger, M., Watson, V., Arwidson, P., Alla, F. & Luchini, S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in a representative working-age population in France: a survey experiment based on vaccine characteristics. Lancet Public Heal ., https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-2667(21)00012-8 (2021).

Wood, S. & Schulman, K. Beyond politics—promoting Covid-19 vaccination in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med . NEJMms2033790, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMms2033790 (2021).

Marshall, H. S., Chen, G., Clarke, M. & Ratcliffe, J. Adolescent, parent and societal preferences and willingness to pay for meningococcal B vaccine: a discrete choice experiment. Vaccine 34 , 671–677 (2016).

Administration, F. and D. Development and Licensure of Vaccines to Prevent COVID-19: Guidance for Industry . (2020).

Polack, F. P. et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 383 , 2603–2615 (2020).

Baden, L. R. et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med ., https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2035389 (2020).

Johnson & Johnson. Johnson & Johnson Announces Single-Shot Janssen COVID-19 Vaccine Candidate Met Primary Endpoints in Interim Analysis of its Phase 3 ENSEMBLE Trial. (2020). Available at: https://www.jnj.com/johnson-johnson-announces-single-shot-janssen-covid-19-vaccine-candidate-met-primary-endpoints-in-interim-analysis-of-its-phase-3-ensemble-trial . (Accessed 28 Feb 2021).

Jackson, L. A. et al. An mRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2—preliminary report. N. Engl. J. Med. 383 , 1920–1931 (2020).

Anderson, E. J. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-1273 vaccine in older adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 383 , 2427–2438 (2020).

Quinn, S. C., Kumar, S., Freimuth, V. S., Kidwell, K. & Musa, D. Public willingness to take a vaccine or drug under emergency use authorization during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. Biosecurity Bioterrorism 7 , 275–290 (2009).

Holden Thorp, H. A dangerous rush for vaccines. Science 369 , 885 (2020).

Limaye, R. J., Sauer, M. & Truelove, S. A. Politicizing public health: the powder keg of rushing COVID-19 vaccines. Hum. Vaccines Immunother ., https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2020.1846400 (2020).

Feuer, W. Trump Says ‘No President’s Ever Pushed’ the FDA Like Jim, Vaccine Coming ‘Very Shortly’. CNBC (2020).

Soysal, A., Gokçe, I., Pehlivan, T. & Bakir, M. Interchangeability of a hepatitis A vaccine second dose: Avaxim 80 following a first dose of Vaqta 25 or Havrix 720 in children in Turkey. Eur. J. Pediatr. 166 , 533–539 (2007).

Greenberg, D. P. & Feldman, S. Vaccine interchangeability. Clin. Pediatrics 42 , 93–99 (2003).

Article Google Scholar

Bishai, D., Brice, R., Girod, I., Saleh, A. & Ehreth, J. Conjoint analysis of French and German parents’ willingness to pay for meningococcal vaccine. PharmacoEconomics 25 , 143–154 (2007).

Cameron, M. P., Newman, P. A., Roungprakhon, S. & Scarpa, R. The marginal willingness-to-pay for attributes of a hypothetical HIV vaccine. Vaccine 31 , 3712–3717 (2013).

Litan, R. Want herd immunity? Pay people to take the vaccine. Brookings (2020).

Kane, R. L., Johnson, P. E., Town, R. J. & Butler, M. A structured review of the effect of economic incentives on consumers’ preventive behavior. Am. J. Preventive Med. 27 , 327–352 (2004).

Volpp, K. G., Loewenstein, G. & Buttenheim, A. M. Behaviorally informed strategies for a National COVID-19 vaccine promotion program. JAMA - J. Am. Med. Assoc. 325 , 125–126 (2020).

Google Scholar

Nowalk, M. P. et al. Improving influenza vaccination rates in the workplace. A randomized trial. Am. J. Prev. Med. 38 , 237–246 (2010).

Bertin, P., Nera, K. & Delouvée, S. Conspiracy beliefs, rejection of vaccination, and support for hydroxychloroquine: a conceptual replication-extension in the COVID-19 pandemic context. Front. Psychol. 11 , 2471 (2020).

Lee, J. J. et al. Associations between COVID-19 misinformation exposure and belief with COVID-19 knowledge and preventive behaviors: cross-sectional online study. J. Med. Internet Res. 22 , e22205 (2020).

Reyna, V. F. Risk perception and communication in vaccination decisions: a fuzzy-trace theory approach. Vaccine 30 , 3790–3797 (2012).

Lin, C., Tu, P. & Beitsch, L. M. Confidence and receptivity for covid‐19 vaccines: a rapid systematic review. Vaccines 9 , 1–32 (2021).

Broniatowski, D. A. et al. Facebook pages, the ‘Disneyland’ measles outbreak, and promotion of vaccine refusal as a civil right, 2009–2019. Am. J. Public Health 110 , S312–S318 (2020).

Moon, K., Riege, A., Gourdon-Kanhukamwe, A. & Vallée-Tourangeau, G. The Moderating Effect of Autonomy on Promotional Health Messages Encouraging Flu Vaccination Uptake Among Healthcare Professionals . (PsyArXiv, 2020), https://doi.org/10.31234/OSF.IO/AJV4Q .

Ferdinand, K. C., Nedunchezhian, S. & Reddy, T. K. The COVID-19 and influenza “Twindemic”: barriers to influenza vaccination and potential acceptance of SARS-CoV2 vaccination in African Americans. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 112 , 681–687 (2020).

PubMed Google Scholar

Jaiswal, J., LoSchiavo, C. & Perlman, D. C. Disinformation, misinformation and inequality-driven mistrust in the time of COVID-19: lessons unlearned from AIDS denialism. AIDS Behav. 24 , 2776–2780 (2020).

Determann, D. et al. Acceptance of vaccinations in pandemic outbreaks: a discrete choice experiment. PLoS ONE 9 , e102505 (2014).

Simpson, C. R., Ritchie, L. D., Robertson, C., Sheikh, A. & McMenamin, J. Effectiveness of H1N1 vaccine for the prevention of pandemic influenza in Scotland, UK: A retrospective observational cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 12 , 696–702 (2012).

Remmel, A. COVID vaccines and safety: what the research says. Nature 590 , 538–540 (2021).

Coppock, A. & McClellan, O. A. Validating the demographic, political, psychological, and experimental results obtained from a new source of online survey respondents. Res. Polit. 6 , 1–14 (2019).

de Bekker-Grob, E. W. et al. The impact of vaccination and patient characteristics on influenza vaccination uptake of elderly people: A discrete choice experiment. Vaccine 36 , 1467–1476 (2018).

Determann, D. et al. Public preferences for vaccination programmes during pandemics caused by pathogens transmitted through respiratory droplets–A discrete choice experiment in four European countries, 2013. Eurosurveillance 21 , 1–13 (2016).

de Bekker-Grob, E. W. et al. Girls’ preferences for HPV vaccination: A discrete choice experiment. Vaccine 28 , 6692–6697 (2010).

Guo, N., Zhang, G., Zhu, D., Wang, J. & Shi, L. The effects of convenience and quality on the demand for vaccination: results from a discrete choice experiment. Vaccine 35 , 2848–2854 (2017).

Kaplan, R. M. & Milstein, A. Influence of a COVID-19 vaccine’s effectiveness and safety profile on vaccination acceptance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118 , 2021726118 (2021).

Hainmueller, J., Hopkins, D. J. & Yamamoto, T. Causal inference in conjoint analysis: Understanding multidimensional choices via stated preference experiments. Polit. Anal. 22 , 1–30 (2014).

Organization, W. H. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public: Mythbusters. (2020). Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public/myth-busters . (Accessed 14 Jan 2021).

Download references

Acknowledgements

S.K. and D.K. would like to thank the Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability for financial support.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Government, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA

Sarah Kreps & Douglas L. Kriner

Injury Prevention Research Center, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Nabarun Dasgupta

Department of Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

John S. Brownstein

Computational Epidemiology Lab, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of California, San Francisco, CA, USA