- Mission & History

- Transparency

- 2023 Annual Report

- Join Our Email List

- Major Campaigns of 2024

- Attorney Referral Program

- Find An Attorney

- Who is a Whistleblower?

- What to Know

- Protections and Rewards

- Stop Retaliation

- Climate Center

- Revitalize the IRS Whistleblower Program

- Enact AML Whistleblower Rules

- Save the CFTC Whistleblower Program

- Protect the False Claims Act

- Reform the SEC Whistleblower Program

- Fight Climate Corruption in Banking and Securities

- Strengthen U.S. Whistleblower Laws

- Women’s History Month

- Whistleblower Network News

- Rules for Whistleblowers

- Press Releases

- Contact Form

Case Studies

The National Whistleblower Center has taken a look at several high profile cases in industries with a high risk of fraud in order to highlight the type of fraudulent activities that can occur.

The first climate-change related securities class action against a major oil and gas company, Ramirez v. ExxonMobil Corporation, highlights how whistleblowers can identify potential securities fraud related to climate risks and oil and gas reserves.

The Shell reserves scandal shows that even the world’s oldest and largest oil and gas companies are not immune to the temptation to overstate their reserves.

Using the qui tam provision of the False Claims Act, a group of whistleblowers revealed a nationwide conspiracy by more than a dozen oil and gas companies to systematically defraud the government by underpaying leasing royalties.

Making false statements to obtain a permit, lease, or loan like BP did for the Deepwater Horizon rig falls under a powerful whistleblower provision, known as the reverse False Claims Act.

Chevron’s Gorgon gas project in Australia was supposed to generate enough tax revenue to facilitate personal tax cuts for every Australian. Instead, most of the profits were siphoned off into offshore tax havens.

An investigation into widespread corruption in the oil and gas industry revealed a scheme by six oil and gas companies to use a third party to pay and conceal bribes to foreign officials.

The U.S. government’s first prosecution for mineral-rights leases concerned the collaboration on bids between competing oil and gas companies in Western Colorado.

Oil & gas prices impact nearly every level of our economy, from financial investors to companies producing petroleum products to consumers paying for gas. Fixing prices in commodities markets as was allegedly done in one recent case can harm traders, investors and consumers.

Whistleblowers have successfully used reverse False Claims suits to stop industrial gas companies from dodging customs duties in cases such as Jackson vs. Linde.

A landmark investigation into Occidental Petroleum’s environmental disclosures revealed that major incidents of environmental damage can also help regulators identify equally significant financial fraud in liability disclosures.

Rio Tinto’s Mozambique coal scandal shows how executives under pressure could be tempted to commit fraud – and how internal whistleblowers can reveal the truth.

An investigation into the nation’s largest coal company revealed that it had knowingly not disclosed the full financial risks associated with new environmental regulations to shareholders over a period of several years.

A historic case against Kerr-McGee highlights the potential for a company to understate liabilities to spin them off and how such a scheme can lead to a multibillion-dollar liability.

Lenders have accused Murray Energy of fraudulent transfer and breach of fiduciary duty, as well as manipulating financial information to avoid violating a bankruptcy financing agreement.

From 2001 to 2011, several Minnesota businessmen solicited major investments in a clean coal machine that they knew didn’t work, committing securities fraud in the process.

FirstEnergy is an IOU headquartered in Akron, Ohio that operates several electricity generation and distribution subsidiaries throughout the Midwest and Mid-Atlantic. It has recently been linked to a major bribery & racketeering scandal and is currently under investigation for securities fraud.

In 2016, SandRidge Energy Inc. became the first company to be charged by the SEC for retaliating against an internal whistleblower and one of the first companies to be charged for using illegal severance agreements to block whistleblowers from reporting to the SEC.

A securities class action lawsuit alleged that timber company Rayonier violated federal securities laws by concealing systemic over-harvesting in Washington state.

In a landmark case, U.S.-based Lumber Liquidators was fined $13 million under the Lacey Act for illegally importing hardwood flooring from the Russian Far East.

A recent NGO report alleges that protected timber illegally harvested by Chinese company dodged U.S. conservation laws via numerous middlemen.

A recent case concerning disappearing containers of rare wood from Gabon demonstrates the role that whistleblowers can play in combatting fraud in the timber industry.

Advocates for Justice

Taxpayer money is everywhere. And where there is money, there are people willing to cheat to get more than their fair share. Fortunately, there are also upstanding humans interested in calling out wrongdoers gaming the system and stealing tax dollars. Also fortunately, we have whistleblower rewards!

The primary law used to assist those blowing the whistle on bad behavior is the federal False Claims Act. The SEC also has a whistleblower program that has grown significantly over the past decade. The last year has brought a record number of whistleblower claims under the FCA and SEC programs. In 2020, the SEC received almost 7,000 whistleblower tips—a 31% increase from just two years prior, and a more than two-fold increase since the program’s inception. Stemming from whistleblower lawsuits, the SEC has awarded almost $700 million to over 100 individuals since issuing its first award in 2012.

How to be a whistleblower? Whistleblowers may be eligible for an award when they voluntarily provide original, timely, and credible information that leads to a successful enforcement action. Awards in a whistleblower case can range from 10 to 30 percent of the money collected when the sanctions exceed $1 million.

Whistleblower lawsuits vary. In every industry, the U.S. government pays private companies for goods or services. In healthcare, Medicare and Medicaid constitute half of payments to providers of medical services and goods. In the defense industry, hundreds of billions of government dollars are paid to private contractors. Beyond those fields, billions of government dollars go to everything from toilet paper and hand soap, to computers, extension cords and software, and everything in between. The government also supports many industries through subsidies, loans, and guarantees.

Below are details regarding the top awards under the FCA and SEC whistleblower programs over the past year.

- Settlement Date: July 1, 2020

- Defendant: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation

- Allegation: Between 2002 and 2011, violating the Anti-Kickback Statute and False Claims Act by providing doctors with cash payments, luxury travel and meals to induce them to prescribe Novartis cardiovascular and diabetes drugs reimbursed by federal healthcare programs.

- Total Settlement: $642 million

- Whistleblower Award: TBD

- Want more info about this case? https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/novartis-pays-over-642-million-settle-allegations-improper-payments-patients-and-physicians

- Settlement Date: October 22, 2020

- Defendant: Undisclosed

- Allegation: Information and assistance led to the SEC’s successful enforcement action and successful related actions by other agencies.

- Total Settlement: Undisclosed

- Whistleblower Award: $114 million.

- Want more info about this case? https://www.forbes.com/sites/danielcassady/2020/10/22/whistleblower-awarded-over-114-million-by-sec/?sh=61155e343979

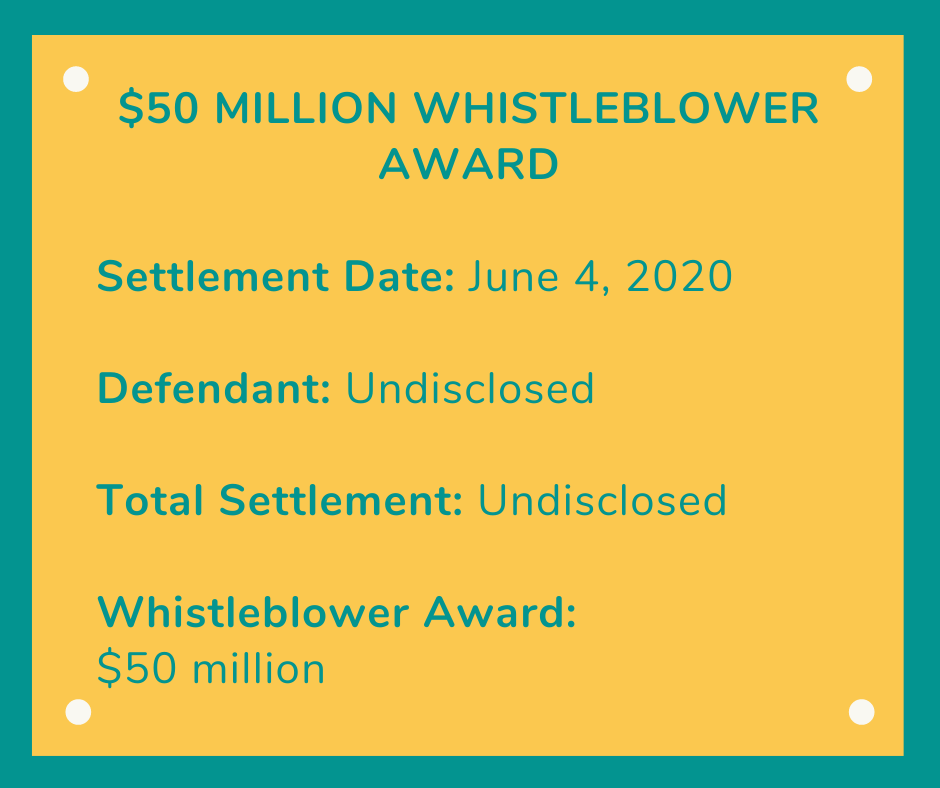

- Settlement Date: June 4, 2020

- Allegation: Detailed, firsthand observations of misconduct by a company that resulted in a successful enforcement action and the return of significant funds to investors.

- Total Settlement: Undisclosed

- Whistleblower Award: $50 million (at the time, the largest amount ever awarded to one individual under the SEC’s whistleblower program)

- Want more info about this case? https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2020-126

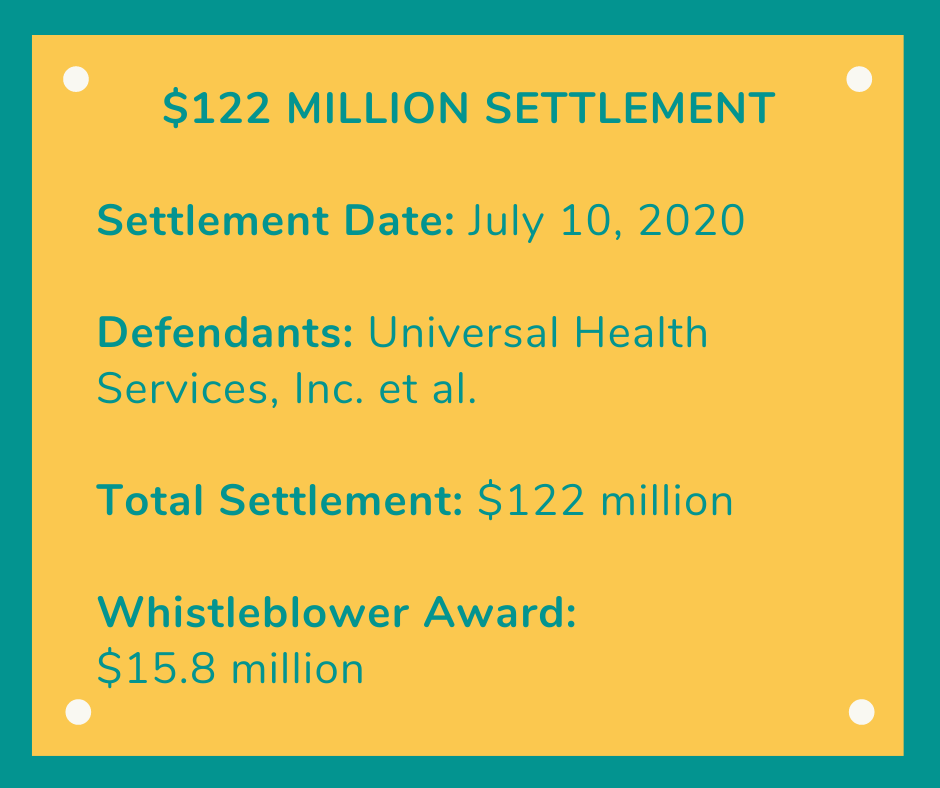

- Settlement Date: July 10, 2020

- Defendants: Universal Health Services, Inc. and UHS of Delaware, Inc. (collectively, UHS), and a Georgia-based UHS facility, Turning Point Care Center, LLC

- Allegation: Billing federal healthcare programs for medically unnecessary inpatient behavioral health services, failing to provide adequate or appropriate services, and paying illegal inducements to program beneficiaries.

- Total Settlement: $122 million

- Whistleblower Award: $15.8 million.

- Want more info about this case? https://www.justice.gov/usao-mdfl/pr/universal-health-services-inc-and-related-entities-pay-122-million-settle-false-claims

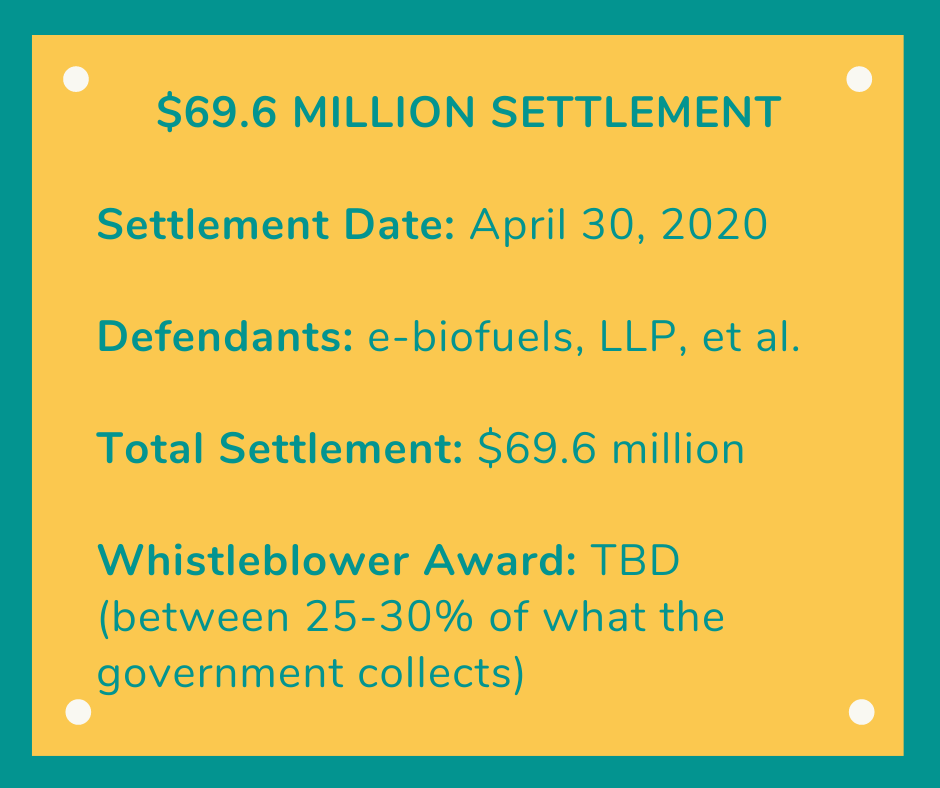

- Settlement Date: April 30, 2020

- Defendants: e-biofuels, LLP, et al.

- Allegation: Making fraudulent transactions in the renewable energy biofuels industry.

- Total Settlement: $69.6 million

- Whistleblower Award: TBD (between 25-30% of what the government collects)

- Want more info about this case? https://whistleblowersblog.org/2020/05/articles/featured-story/court-issues-69-6-million-judgement-in-qui-tam-false-claims-act-whistleblower-case/

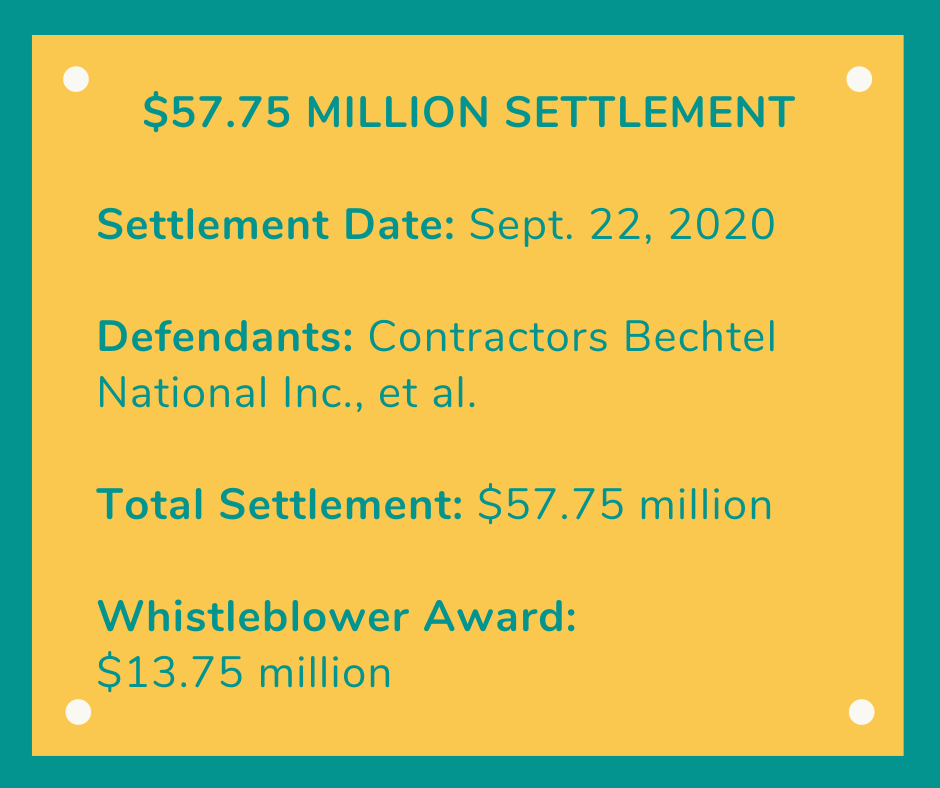

- Settlement Date: September 22, 2020

- Defendants: Contractors Bechtel National Inc., Bechtel Corporation, AECOM Energy & Construction, Inc., and Waste Treatment Completion Company, LLC

- Allegation: Overbilling the Department of Energy for work on the Hanford Waste Treatment Plant on craft labor performed by electricians, millwrights, pipefitters, and other skilled trades workers, including billing for unallowable and unreasonable idle time caused by management failures in scheduling work.

- Total Settlement: $57.75 million

- Whistleblower Award: $13.75 million

- Want more info about this case? https://www.justice.gov/usao-edwa/pr/bechtel-aecom-us-department-energy-doe-contractors-agree-pay-5775-million-resolve-0

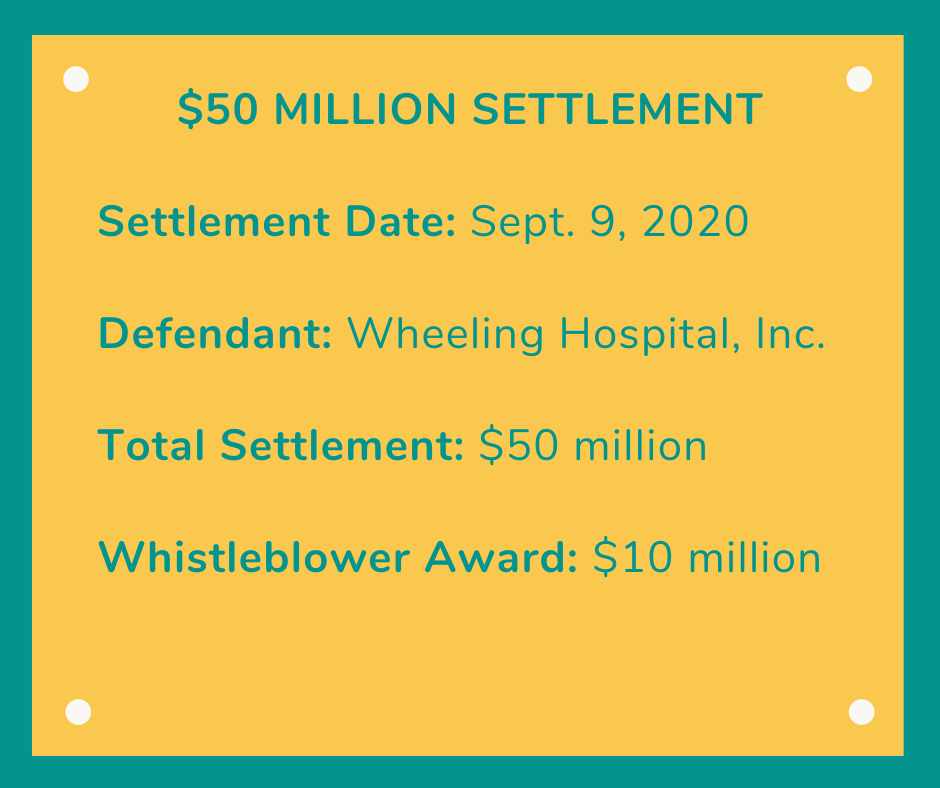

- Settlement Date: September 9, 2020

- Defendant: Wheeling Hospital, Inc.

- Allegation: Providing referring physicians with compensation above fair market value, based on the volume or value of their referrals, then submitting to Medicare claims resulting from those improper referrals.

- Total Settlement: $50 million

- Whistleblower Award: $10 million

- Want more info about this case? https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/west-virginia-hospital-agrees-pay-50-million-settle-allegations-concerning-improper

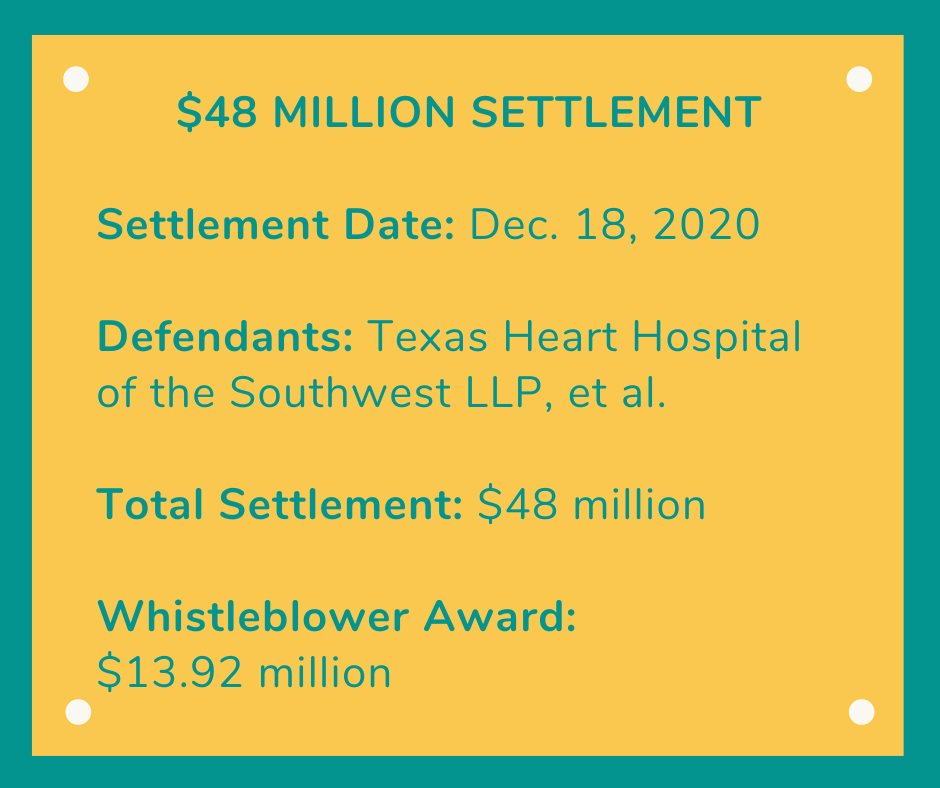

- Settlement Date: December 18, 2020

- Defendants: Texas Heart Hospital of the Southwest LLP and its affiliate THHBP Management Company LLC

- Allegation: Requiring the physician-owners doctors of the hospital to have 48 patient-contacts a year in order to maintain their ownership interests.

- Total Settlement: $48 million

- Whistleblower Award: $13.92 million

- Want more info about this case? https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/texas-heart-hospital-and-wholly-owned-subsidiary-thhbp-management-company-llc-pay-48-million

- Settlement Date: April 27, 2020

- Defendant: Genova Diagnostics Inc.

- Allegation: Billing government healthcare programs for medically unnecessary lab tests, and paying unlawful compensation to phlebotomy vendors.

- Total Settlement: $43 million

- Whistleblower Award: $6 million

- Want more info about this case? https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/testing-laboratory-agrees-pay-43-million-resolve-allegations-medically-unnecessary-tests

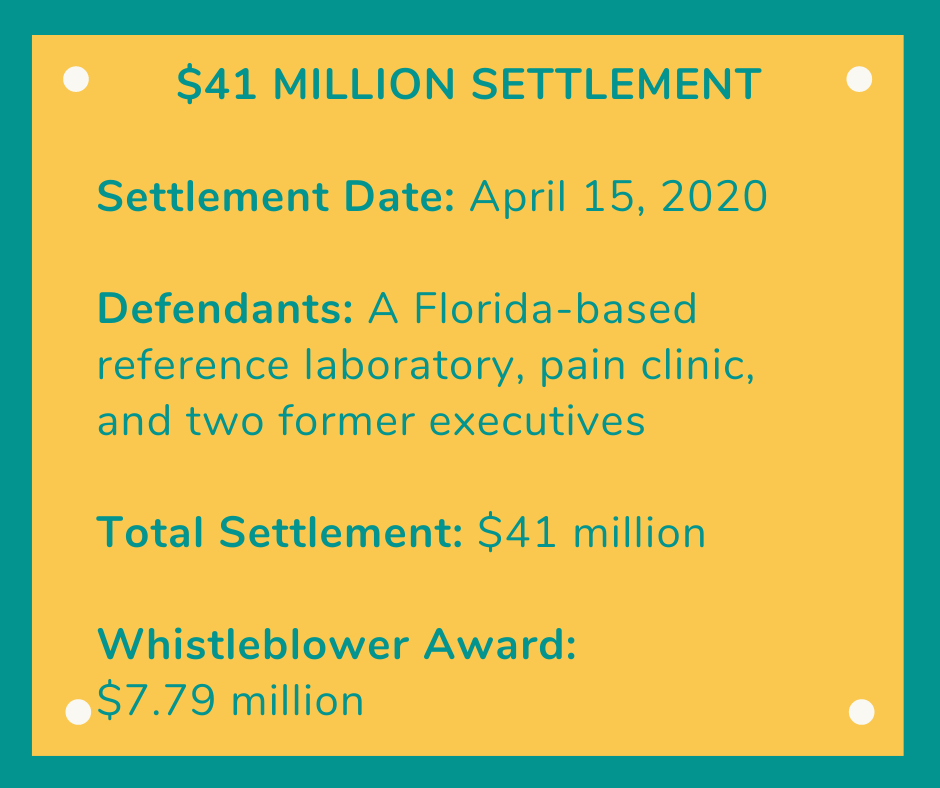

- Settlement Date: April 15, 2020

- Defendants: A Florida-based reference laboratory, pain clinic, and two former executives

- Allegation: Automatically ordering urine drug tests for all patients at every visit regardless of need.

- Total Settlement: $41 million

- Whistleblower Award: $7.79 million

- Want more info about this case? https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/reference-laboratory-pain-clinic-and-two-individuals-agree-pay-41-million-resolve-allegations

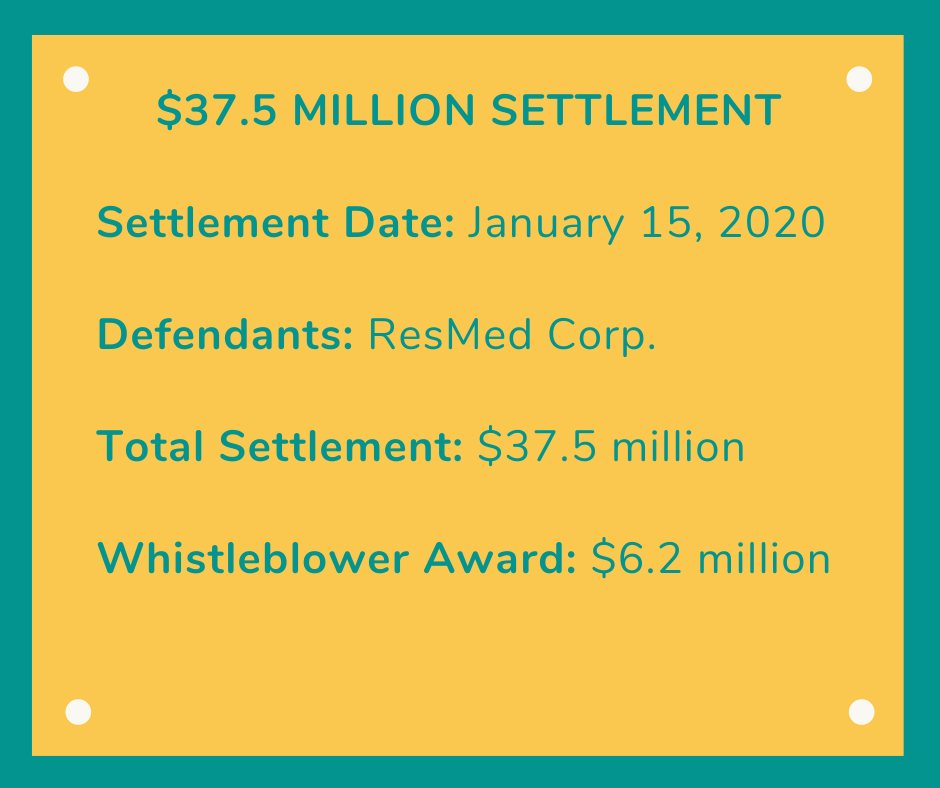

- Settlement Date: January 15, 2020

- Defendant: ResMed Corp.

- Allegation: Improperly providing or helping provide free or below cost call center services, patient outreach services, medical equipment and installation, and interest-free loans to suppliers, sleep labs, and other health providers, in exchange for business.

- Total Settlement: $37.5 million

- Whistleblower Award: $6.2 million

- Want more info about this case? https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/resmed-corp-pay-united-states-375-million-allegedly-causing-false-claims-related-sale

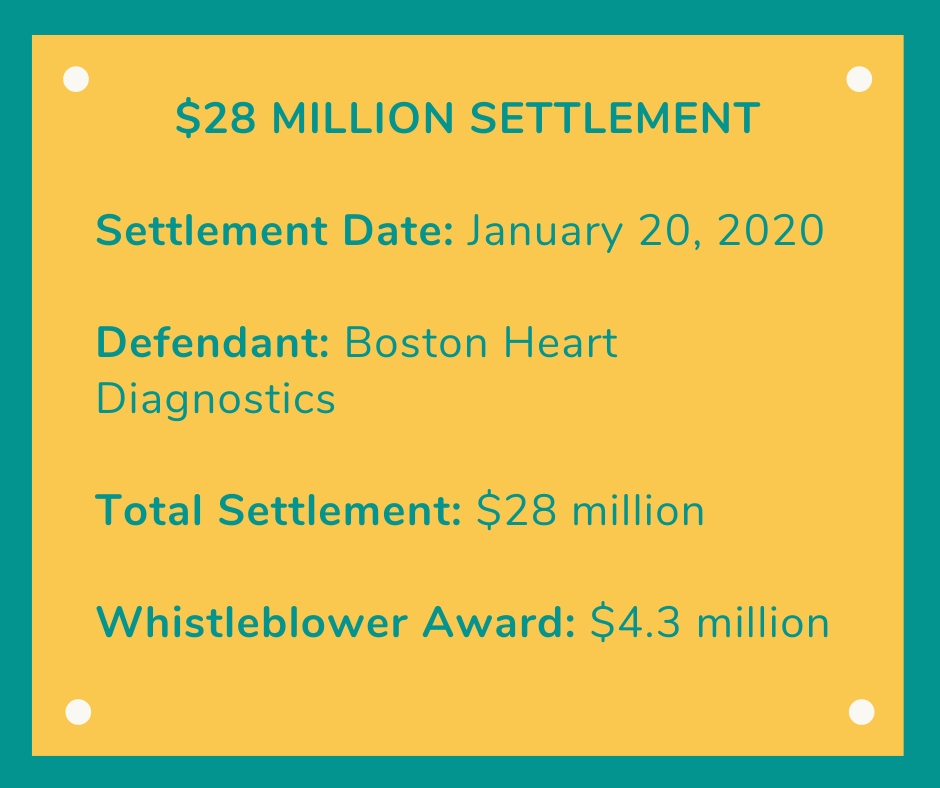

- Settlement Date: January 20, 2020

- Defendant: Boston Heart Diagnostics

- Allegation: Entering into multiple quid pro quo arrangements with doctors that order its tests, recruiting doctors to have them promise that their patients would never have to pay a deductible or co-payment, and offering free dietician counseling services in exchange for the doctors’ ordering (via Medicare) an expensive panel of laboratory tests.

- Total Settlement: $28 million

- Whistleblower Award: $4.3 million

- Want more info about this case? https://www.cpmlegal.com/news-28-Million-Settlement-in-Major-Whistleblower-Suit-Against-Boston-Heart-Diagnostics

Need a whistleblower attorney? Cotchett Pitre and McCarthy is one of the nation’s most successful and well-respected whistleblower law firms, representing individuals retaliated against by employers for raising concerns, and individuals reporting corporate fraud resulting in the waste of taxpayer money. For general information about CPM’s Whistleblower practice, see this link: https://www.cpmlegal.com/practices-Whistleblower-Qui-Tam-False-Claims-California

Want to learn more? To learn more about the terminology of whistleblower law, including definitions of terms like whistleblower, “qui tam,” “relator” (very different from “realtor”), and the specifics of the timing and scope of governmental investigations, check out this link: https://www.cpmlegal.com/practices-Whistleblower-Qui-Tam-False-Claims-California#FAQs

Sarvenaz (Nazy) Fahimi is a partner practicing in several areas of litigation, with a focus on high profile cases of fraud, cases involving qui tam Relators in False Claims Act cases in federal and state courts, and cases ...

- Follow us on LinkedIn

- Follow us on Twitter

- Follow us on Facebook

- False Claims/Whistleblower

- Consumer Protection

- Elder Abuse

- Employment Law

- Personal Injury

- Securities / Financial Fraud

- Class Actions

- Environmental Litigation

- Public Interest

- California Law

- Intellectual Property

- San Francisco Bay Area 650.697.6000

- Los Angeles/Santa Monica 310.392.2008

- New York 212.381.6373

- Seattle 206.802.1272

By using this site, you agree to our updated Privacy Policy and our Terms of Use .

Case Studies

People we've helped, filter our case studies by type of concern raised:.

- abuse of vulnerable person

- consumer breach

- exposure to dangerous substances

- financial mismanagement

- food safety

- furlough fraud

- incorrect reporting to client

- maladministration of medication

- misuse of funds

- patient safety

- social work

- unsafe equipment

- unsafe staffing levels

- work safety

When settlement is the preferred outcome

Helena* worked in the distribution factory of a well-known food company. She was an agency worker, so effectively worked for both her agency and the distribution factory as both played a role in determining the terms of her engagement. At work, Helena noticed a culture of racism including racist language being used by senior members of staff, as well as working practices which disadvantaged Muslim workers.

Side effects of speaking up as a social worker

Eleanor* was a social worker, whose work often brought her to her local hospital to support patients. Over time, she grew increasingly uneasy about the inadequate handling of patient safety, and decisions not being taken in the best interests of vulnerable people. She felt that a manager appeared to be discharging patients who weren’t ready to go home.

Reaching out to the regulator

During the course of his job, Oliver realised his company had hired someone who had previous convictions for a serious financial crime. Oliver had been made to do a DBS check when he joined so was shocked this person had been hired.

HSE take action following whistleblower’s safety concerns

Amal* works for a charity providing wellbeing services to vulnerable adults. She called Protect following a serious incident where a service user had physically threatened her. Amal explained that she had raised concerns previously about the charity’s building not being safe for workers following previous incidents. She told us her requests for securing the premises and implementing additional safety measures for staff had been ignored.

Standing Up for Standards: A Police Officer’s Struggle to Address Unqualified Police Trainers

As a new recruit in the police force, Mary* was shocked to discover what was happening amongst police officers in her area. Mary knows that so-called “trainers” are responsible for teaching police officers how to do their job and issuing licenses to those who have completed their training. However, Mary came across compelling evidence suggesting that more than a hundred trainers themselves were unqualified and lacked oversight of who had completed their training.

Advice for Union Reps supporting migrant whistleblowers

Dentist reaches settlement after victimisation for whistleblowing, health and safety gone mad, the cost of victimisation, poor practice at the practice , charity worker raises furlough fraud concerns, blacklisted – or simply bad luck.

Georgia worked as an electrical engineer on a major transport project. She reported that electrical installations did not comply with health and safety standards. When no action was taken she resigned in frustration and the following year the contractors in question were replaced.

Supermarket worker speaks up about health and safety concerns

Graham (not his real name) worked in a managerial role at a supermarket and became concerned about the supermarket’s health and safety practices. He saw examples of staff working in unsafe conditions, with their own health and safety being disregarded. Food produce regulations were not being followed, such as frozen food being sold after it … Read more

Teacher speaks up over student safeguarding concerns

Food factory worker raises concerns over lack of covid-19 safety measures, accountant speaks up over construction company’s financial malpractice, furloughed restaurant employee had concerns over illegal working ignored, education worker bullied for raising health and safety concerns.

Mary (not their real name) worked at an independent school for children with special educational needs. She was only there only a short time when she started having a number of health and safety concerns about the school. Mary never received any appropriate health and safety training from the organisation, despite being designated the lead … Read more

Mental health worker speaks out over poor patient care

Gillian (not her real name) worked for the NHS for over 20 years. She worked with patients with acute mental illness. Gillian had concerns about poor patient care. This included poor communication, a failure to engage with vulnerable patients, nurses turning up to work late and leaving early, nurses falling asleep on shift, and low … Read more

Finance worker speaks up over fake charges to clients

Patrick worked as an adviser in the financial services industry. He was concerned that his employer had been breaching Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) regulations for a number of years. In particular, Patrick’s firm was charging clients for advice that it had not given and it assessed the performance of its employees by using targets that … Read more

Nurse speaks up over medicine maladministration at care home

Delia (not her real name) worked as a nurse at a care home. Delia witnessed numerous incidents regarding the maladministration of medicine. This included overstocking out of date medication and the administration of overdue and incorrect medication. She raised her concerns with her manager in the first instance, and escalated this to the care home … Read more

Food supplier fails to test food hygiene

Food producer exposes goods to contamination, food manufacturer sells out of date and illegal food, care workers help to stop abuse of vulnerable residents, whistleblower exposed to asbestos speaks up to regulator, unsafe food practices resolved by whistleblower speaking up, social worker speaks up about inappropriate relationship, fraud in family company puts whistleblower in difficult position, manager convicted for theft in care home, protect helps food sector whistleblower agree £100,000 settlement, fraud in charity stopped by whistleblowers, care worker thanked for raising patient safety concerns, our use of cookies.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to footer

Whistleblower Aid

Report Government & Corporate Lawbreaking. Without Breaking The Law.

Case Studies

Col. earl matthews' reprisal claim for speaking out about january 6.

Andrew Bakaj and Mark Zaid filed a whistleblower reprisal complaint on behalf of our client Colonel (COL) Earl Matthews, a Judge Advocate in the U.S. Army Reserve with the Department of Defense Office of Inspector General, and former Acting General Counsel of the U.S. Army.

Prior to engaging Mark Zaid’s law firm and Whistleblower Aid, in December 2021 COL Matthews disclosed to the House January 6 th Committee and the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee that, among other things, the Director of the Army Staff, Lieutenant General Walter E. Piatt and the Army’s former Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations, now-General Charles A. Flynn, had not been completely factual or truthful in their June 2021 oral and written testimony to the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee or in their testimony to the DoD OIG. Furthermore, COL Matthews asserted that LTG Piatt had overseen the creation of a misleading, factually flawed, and revisionist recitation of events called the Report of Operations of the United States Army. Subsequently, LTG Piatt provided the factually flawed report to several committees of the U.S. Congress.

In October 2022, The Washington Post reported that President Biden declined to nominate LTG Piatt for promotion to full General due to concerns over his actions or inaction on and around January 6th. The October 2022 Washington Post article on the President’s decision not to nominate LTG Piatt referenced COL Matthews’ December 2021 disclosure, which had been critical of Piatt’s activities surrounding the events of January 6, 2021.

As a direct result of COL Matthews’ protected communications, Responsible Management Officials (“RMOs”) associated with the U.S. Army War College retaliated against him by, among other things: 1) falsely accusing him of misconduct and/or unprofessional behavior; 2) by abruptly curtailing a scheduled 12-day reserve duty assignment midway through; 3) by having COL Matthews physically and visibly escorted out of a publicly accessible hotel by security personnel; and 4) by providing COL Matthews’ name and likeness to military police personnel assigned onsite as a person of concern who might attempt to disrupt the military conference that Matthews had previously been assigned to support in his reserve capacity. In addition to causing him the loss of military pay and reserve retirement points, the retaliatory actions of the Army War College RMOs caused COL Matthews grievous reputational harm, significant personal embarrassment and public humiliation.

Related Media

- “Army officer alleges reprisal for his account of Capitol riot response” - The Washington Post

- “‘Absolute liars': Ex-D.C. Guard official says generals lied to Congress about Jan. 6” - Politico

- “Former Guard Official Says Army Retaliated for His Account of Jan. 6 Delay” - The New York Times

- “Army Colonel alleges retaliation after whistleblower complaint regarding January 6th” - CNN

Capitol Police Intelligence Officer Warnings on Known Threats of Violence before January 6 Ignored

Mark Zaid, with support from Whistleblower Aid, represented Julie Farnam, then the Assistant Director of Intelligence with the U.S. Capitol Police. With counsel support, Ms. Farnam disclosed to the USCP Inspector General and then later the January 6th Committee evidence that she and her intelligence team had previously warned Capitol Police senior leaders of an impending threat of violence which ultimately became the January 6th insurrection.

- “Ex-Capitol Police Chief Faults Intelligence Officials and Military in Jan. 6 Attack” - New York Times

- “Capitol Police official says she warned of potential violence before riot” - CNN

- “Exclusive: Inside the Capitol Police intelligence unit overhaul that caused confusion ahead of January 6” - The Hill

- “Capitol Police intelligence official says she sounded alarm about potential violence days before January 6 riot” - CBS

- “Inside the Capitol Cops’ Jan. 6 Blame Game” - Rolling Stone

- “Farnam interview with the House Select Committee on the January 6 attack” - House Select Committee on the Jan. 6 Attack (Contributed by Project on Government Oversight)

- “The Capitol Police Weren’t Ready on Jan. 6, and They Aren’t Ready Now” - The Daily Beast

How Whistleblower Aid Helped Raise the Alarm About Data Security At Twitter Even Before Elon Musk's Takeover

When the former head of security at Twitter, Peiter “Mudge” Zatko, wanted to speak out about security, privacy and infrastructure failures at the company even before Elon Musk’s takeover, he turned to Whistleblower Aid for support. We and our co-counsel at Katz Banks & Kumin filed disclosures with the SEC, DOJ and FTC as well as relevant Congressional committees and generated media coverage around the globe.

Given Twitter’s prominence and its continuing role as an essential platform for public discourse around the world, we expect our client, with his extraordinary expertise, to continue to receive media coverage and to continue to inform regulators here and abroad on effective enforcement strategies in the public interest.

“When other avenues were exhausted, and I realized I would have to become a legal whistleblower to fulfill my obligations, I was very concerned with making sure that I did things in the most responsible and ethical way possible. Whistleblower Aid was invaluable in helping figure out how to fulfill my obligations through legal avenues. Knowing that my family and I had Whistleblower Aid on our side helped us navigate a very stressful, complicated, and important process.”

- “Former security chief claims Twitter buried ‘egregious deficiencies” - The Washington Post

- “Ex-Twitter exec blows the whistle, alleging reckless and negligent cybersecurity policies” - CNN

- “The Twitter Whistleblower Needs You to Trust Him” - Time

- “Twitter whistleblower alleges major security issues” - NBC

- “Twitter whistleblower alleges execs misled board and public on spam, security” - CNBC

- “Twitter misled U.S. regulators on hackers, spam, whistleblower says” - Reuters

- “A former employee accuses Twitter of big security lapses in a whistleblower complaint” - NPR

- “Twitter Whistleblower Peiter Zatko Has Warned of Cyber Disasters for Decades” - The Wall Street Journal

- “Twitter Whistle-Blower Will Be Star Witness In Congress” - Bloomberg

How We Helped Tell The Real Story About Hate and Violence on Social Media

Frances Haugen, a member of Facebook’s Civic Integrity team, became front page news around the world in 2021 when she showed how the company was misrepresenting its progress on containing the spread of hate, violence, and psychological damage to teenage girls exposed to unrealistic expectations about their bodies. Whistleblower Aid helped Haugen disclose thousands of internal company documents and helped organize hearings in Congress and other national legislatures.

On the media side, our team managed the exclusive public launch of this case with the Wall Street Journal and 60 Minutes which generated a torrent of local, national, and international coverage – that continues today.

We continue to be a resource as Facebook has come under scrutiny from federal law enforcement agencies, state Attorneys General, and class action lawsuits. Policymakers at home and abroad rely on our expertise as they craft new legislation, including the recent Kids Online Safety Act, introduced by Senators Blumenthal and Blackburn. Ms. Haugen’s testimony and recommendations played a key role in shaping the legislation according to Senator Blumenthal. Ms. Haugen’s testimony before the European Union was credited for playing a pivotal role in the passing of the EU’s Digital Marketing Act and Digital Services Act.

Frances Haugen’s case was a watershed moment in the public’s understanding of how decisions made by Facebook and its parent company Meta can affect our daily lives.

- “The Facebook Whistleblower, Frances Haugen, Says She Wants to Fix the Company, Not Harm It” - The Wall Street Journal

- “Whistle-Blower Unites Democrats and Republicans in Calling for Regulation of Facebook” - The New York Times

- “Facebook Whistleblower Frances Haugen: The 60 Minutes Interview” - 60 Minutes

- “Inside Frances Haugen's Decision to Take on Facebook” - TIME

- “Frances Haugen: ‘I never wanted to be a whistleblower. But lives were in danger” - The Guardian

- “Here are 4 key points from the Facebook whistleblower's testimony on Capitol Hill” - NPR

- “Whistle-Blower Says Facebook ‘Chooses Profits Over Safety” - The New York Times

Whistleblower Aid Stands with High-Profile Witness Leading to Trump’s First Impeachment

When a member of the intelligence community felt compelled to report on a phone call in which President Trump attempted to parlay foreign aid to Ukraine into an investigation into his political rival, Whistleblower Aid attorneys Andrew Bakaj and Mark S. Zaid jumped in to represent them. The lawful, protected complaint they filed triggered multiple investigations into the President’s use of his office to engage in election interference and ultimately resulted in the first impeachment of then President Donald Trump. The reason we know about Trump’s illegal misconduct is only because a civil servant had the courage to speak out .

Whistleblower Aid was critical in providing funding, physical security, technological support, and encrypted communications for the legal team who represented the unnamed whistleblower. We continue to protect their identity.

- “Trump’s communications with foreign leader are part of whistleblower complaint that spurred standoff between spy chief and Congress, former officials say” - The Washington Post

- “Whistleblower claimed that Trump abused his office and that White House officials tried to cover it up” - The Washington Post

- “Washington at war: Dems aim for speedy impeachment push as Trump threatens whistleblower” - CNN

- “Whistleblower report complains of White House cover-up on Trump-Ukraine scandal” - Reuters

- “Read the full text of the Trump-Ukraine whistleblower complaint” - NBC

- “Whistleblower claims White House abused power, tried to cover up details of Ukraine call” - PBS Newsletter

- “READ: House Intel Committee Releases Whistleblower Complaint On Trump-Ukraine Call” - NPR

- “The Trump-Ukraine whistleblower complaint, explained” - Vox

Anonymous Whistleblower calls out Persistent Threat

When then-CEO Parag Agrawal initiated a campaign to discredit renowned cybersecurity chief, Mudge Zatko’s, disclosures about the true state of Twitter, anonymous whistleblower known as Jack Spratt, came forward with documentary evidence demonstrating just how easy it is to impersonate users on Twitter. When Spratt dug into how and why multiple methods for tweeting as others existed, Twitter’s answer was a game of semantics. Changing the name of one capability from “GodMode” to “PrivilegedMode” as a “solution” to the fact that every Twitter engineer was given GodMode upon entry to the company did nothing to limit the exposure to users. Even after Elon Musk took over, anyone with access to Twitter’s engineering code base could easily Tweet as any user without leaving a record of foul play.

Spratt’s disclosures to the SEC, FTC and others submitted by Whistleblower Aid, both substantiated Mudge’s warnings on privacy, security and national security concerns – and exposed the bad faith anti-whistleblower tactics by Twitter leadership.

Working with Whistleblower Aid has been an exceptional experience; their professionalism, empathy, relationships and stewardship has provided a significant peace of mind for myself and my family. WBA recognizes that it is a huge step and risk to speak up, and having worked with them, their dedication, attention and care to the individual and their message is treated with the utmost care and diligence. They truly make you the North Star, and help champion your observations to ensure that they are communicated with the right stakeholders.” – Anonymous Twitter Whistleblower

- “Ex-Twitter engineer tells FTC security violations persist after Musk” - The Washington Post

- “Twitter engineers can still use 'GodMode' to tweet as any account, claims whistleblower” - Engadget

- “Twitter Still Has Security Flaws After Musk Takeover, Whistleblower Alleges” - CNET

- “New Twitter Whistleblower Says Privacy Lapses Continued Into Musk Era” - Bloomberg

- “Twitter ‘GodMode’: Whistleblower Reveals this Allows Engineers to Tweet as Anyone, But is it Legit?” - Tech Times

Whistleblower Aid Exposes Police Department That Protected a Serial Rapist

A former special federal prosecutor revealed that the Johnson City (TN) Police Department (JCDP) was protecting an alleged serial rapist – and Whistleblower Aid stepped up to represent her. The JCPD refused to investigate multiple, credible allegations that a suspect was drugging and raping women spanning more than a decade. Two of the victims were critically injured or died following their encounters with him.

This is an ongoing investigation and Whistleblower Aid is working diligently with co- counsel and regional media to identify victims, connect them with appropriate legal representation, and hold the JCPD accountable.

“I was so grateful when [Whistleblower Aid] took on my case and helped me navigate the process of whistleblowing. It can be an overwhelming and isolating experience, so having such a knowledgeable team step in was a huge relief. I was impressed not only by their legal expertise, but by their compassion for their clients who are in difficult and stressful situations. Their dedication to the truth and protecting whistleblowers who come forward is admirable.” – Kateri Dahl

- “Former federal attorney’s lawsuit: JC police chief fired her in retaliation after she pressed for rape investigations” - WJHL Channel 11 News

- “Whistleblower Aid: Evidence for DOJ complaint growing in JCPD ‘Voe’ case” - WJHL Channel 11 News

- “Prominent whistleblower group steps into JC police allegations, seeks additional information from people” - WJHL Channel 11 News

- “Former Federal Prosecutor Sues Johnson City over Botched Serial Rapist Case” - The Tennessee Star

- “Johnson City Police sued by former Special Assistant U.S. Attorney: Case alleges police ignored repeated allegations of rape and allowed the suspect to escape” - The Tennessee Lookout

Protecting the Most Vulnerable Caught in Political Crossfire

Our clients revealed that Facebook had deliberately blocked pages of Australian government fire and safety agencies, among others, during brush fire season and health institutes days before the Covid-19 vaccine rollout in a strategically executed blackout that was only supposed to include news sites. They revealed it was a premeditated effort to strong-arm the Australian government and influence precedential legislation on how much it and other tech companies should pay news outlets for the use of journalistic content.

Whistleblower Aid helped our clients lawfully disclose their evidence to members of Congress, the United States Attorney General Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section, the DOJ Criminal Division, and the California US Attorney. We continue to protect their identities.

Shortly after our clients made their submission, The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission began investigating our clients’ claims. During an October 2022 Legislative Hearing by the Canadian Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage, Whistleblower Aid and our clients’ disclosure were directly cited while debating Bill C-18, An Act respecting online communications platforms that make news content available to persons in Canada . Many European nations are also considering our client’s disclosure as they move to adopt similar legislation.

- “Facebook Deliberately Caused Havoc in Australia to Influence New Law, Whistleblowers Say” - The Wall Street Journal

- “Facebook Accused of Deliberately Causing Havoc in Australia Over News Content Law” - CNET

- “Facebook whistleblowers allege government and emergency services hit by Australia news ban was a deliberate tactic” - The Guardian

- “Whistleblowers claim Facebook’s chaotic Australia news ban was a negotiating tactic” - The Verge

- “Facebook accused of deliberately disrupting Australia emergency services” - BBC

Whistleblower Aid Exposes Hate and Human Rights Abuses Facebook Ignored

Joohn Choe hunted bad actors for Facebook. His directive was to find and report hate groups, inciters of violence, and illegal use of the platform according to their community standards and federal regulations. What he found, and alerted senior executives to, was evidence that sanctioned, pro-Russian rebels were using the platform to identify and imprison dissidents in early 2021. Despite his efforts, Facebook did not act on Mr. Choe’s reports and continued to allow the sanctioned rebels to use the platform to spread misinformation and publicly hunt and persecute people fighting for human rights in the country. Whistleblower Aid helped Mr. Choe to safely disclose his findings to the DoJ and the FBI.

Mr. Choe continues to identify companies that are violating US trade and business restrictions and he shares these tips with the Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Asset Control. Many of his tips involve businesses illegally supporting Russia and president Vladimir Putin. These sanctions will support international democracy and help protect those who fight against the unjust invasion of Ukraine.

Furthermore, Mr. Choe transmitted his research on hate groups and violent inciters to the January 6th Committee.

“Before Whistleblower Aid, honestly, I felt… like I was way over my head and I didn’t have adequate preparation… [Whistleblower Aid] provided the support that I needed to come forward and provide my truth to the world – to become a whistleblower myself.” – Joohn Choe

- “Pro-Russia rebels are still using Facebook to recruit fighters, spread propaganda” - The Washington Post

- “Whistleblower alleges Meta violated US sanctions law by permitting pro-Russia rebels’ accounts” - The Hill

- “Sanctioned Russian Facebook Accounts Still Used for Recruitment! Rumors Claim They Remain Active” - Tech Times

- “The age of the work-from-home whistleblower” - Business Insider

Whistleblower Aid Details Former LA Mayor Eric Garcetti’s Lies to Congress

Two months after the Senate Foreign Relations Committee unanimously approved Eric Garcetti’s nomination as the next U.S. ambassador to India, Whistleblower Aid filed a disclosure accusing Garcetti of lying under oath. He had denied being aware that his top aide had for years engaged in a pattern of persistent sexual harassment and abuse, even though multiple witnesses in a lawsuit filed against the City of Los Angeles had testified that he had in fact seen it with his own eyes on multiple occasions. One of those witnesses, a former communications director to Garcetti named Naomi Seligman, became a Whistleblower Aid client and together we met with the staff of more than two dozen Senators, both Republican and Democrat, to lay out the evidence against Mayor Garcetti and to argue that enabling and attempting to cover up sexual abuse made him unfit to serve.

Whistleblower Aid filed follow-up disclosures and made sure the issue received consistent media coverage. In response, Senator Chuck Grassley directed his Judiciary Committee staff to investigate the issue themselves. Not only did they conclude that Garcetti either did or should have known about the harassment; they also uncovered more witnesses than had previously spoken out.

Two years after the original Whistleblower Aid disclosure, Garcetti remains unconfirmed as ambassador. Ms. Seligman, meanwhile, has joined the staff of Whistleblower Aid as Vice President of External Affairs. With Garcetti’s nomination still pending, we are continuing to support Ms. Seligman with congressional briefings and local and global media reporting .

“I have dedicated my career to holding officials responsible when they violate the public trust. Whistleblower Aid was my invaluable support when I came forward myself to denounce a pattern of enabling sexual harassment and abuse in the Los Angeles mayor’s office and made sure that the facts prevailed even when my former colleagues sought to undermine me.”

- “Mayor Garcetti’s former top spokeswoman wants him charged with perjury” - Los Angeles Times

- “Los Angeles Mayor’s Path to U.S. Ambassadorship Is Constricting” - The New York Times

- “Garcetti Ambassador Nomination Stalled in Senate Over Questions About Former Aide’s Conduct” - The Wall Street Journal

- “GOP senator places hold on Garcetti nomination, citing new whistleblower claims” - Los Angeles Times

- “Grassley privately investigating Garcetti, wants nomination held” - Politico

- “Garcetti ‘likely knew or should have known’ about alleged harassment, Senate report finds” - The Hill

- “Garcetti, you're still here?” - Politico

- “US senator delays India post as Los Angeles mayor denies ignoring abuse” - The Hindustan Times

- “Garcetti’s Path to US Ambassadorship to India further narrows down” - The Print (India)

Whistleblower Aid Shuts Down International Pay-To-Spy Scheme

Gary Miller, a mobile phone security expert, disclosed that the surveillance company NSO Group Technologies offered to give representatives of an American mobile-security firm “bags of cash” in exchange for access to global citizens’ private texts messages, phone calls, and geolocation information.

NSO Group Technologies is an Israeli technical surveillance company that makes Pegasus, a program on smartphones – allowing operators to track the user’s locations, listen to calls, retrieve pictures and monitor social media activity – often used by repressive governments to spy on journalists, dissidents, and activists. Pegasus has been found on the phones of murder victims including prominent Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi who was killed inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul. Whistleblower Aid helped Mr. Miller share his lawful disclosure with the DOJ and members of Congress. We worked with The Washington Post to support their breaking news coverage.

- “NSO offered ‘bags of cash’ for access to U.S. cell networks, whistleblower claims” - The Washington Post

- “NSO offered US mobile security firm ‘bags of cash’, whistleblower claims” - The Guardian

- “US Whistleblower Alleges NSO Offered 'Bags of Cash' to Access Global Mobile Networks” - The Wired

- “How Whistleblowers Navigate a Security Minefield” - Wired

Whistleblower Aid Takes On Harvey Weinstein and Notorious Spy Company

Harvey Weinstein spied on journalists reporting on his sexual crimes in an attempt to identify and harass their sources using an elite, Israeli private intelligence agency called Black Cube. As an investigative subcontractor to Black Cube, Igor Ostrovskiy soon realized he was inadvertently assisting Weinstein while endangering himself and many others.

Whistleblower Aid helped Mr. Ostrovskiy separate from Black Cube and provided secure communications for his use to shield him from retaliation. We helped Mr. Ostrovskiy disclose the surveillance to the journalists reporting on Weinstein and assisted the DoJ in their investigation of Black Cube. We guided Mr. Ostrovskiy through the process of sharing his story with the world with the help of one of the very journalists targeted by Weinstein in an exposé featured in The New Yorker .

Whistleblower Aid is proud to have helped hold Harvey Weinstein accountable for his crimes and to support our nation’s journalists.

“[Whistleblower Aid] guided me through the process… It was a relief. It felt safe. It felt like I’ll be able to continue to do the right thing and I’m not going to jeopardize myself. I don’t know where I would be without Whistleblower Aid.” – Igor Ostrovskiy “I was lucky to have the support of [Whistleblower Aid], a nonprofit law firm that offers pro bono legal services to [w]histleblowers. They are a hero of our time, representing many national interest [whistleblower] clients for free.“ – Igor Ostrovskiy

- “The Black Cube Chronicles: The Private Investigators” - The New Yorker

- “Catch and Kill” - HBO Docuseries

Whistleblower Aid Bolsters Case Against Hate and Violence Campaigns on Facebook

Our client, Matthew Schissler, a sociocultural anthropologist who formerly lived and worked in Myanmar, provided groundbreaking evidence of Facebook/Meta’s culpability in a campaign of hate and organized violence against Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar.

He documented Facebook’s choice to ignore how the platform was being used to promote violence against ethnic minorities in Myanmar. Mr. Schissler’s disclosure, which Whistleblower Aid filed with the DOJ, highlights Meta’s failure to moderate non-English hate speech and take actions to prevent the deaths and displacement of millions.

Current litigation against Facebook for its role in the Rohingya genocide and complementary work by Amnesty International are using Mr. Schissler’s evidence to hold Meta accountable and prevent similar atrocities.

- “The country where Facebook posts whipped up hate” - BBC

- “Facebook has continued to fail Myanmar. Now its people have to pay the price.” - Media Matters

Whistleblower Aid Defends Right to Expose Corrupt Dealmaking

A former Department of Energy (DOE) photographer Simon Edelman made public photos that showed that then-Secretary Rick Perry was crafting U.S. energy policy to fulfill coal baron Robert Murray’s “wish list”. Mr. Edelman published his photos – which show the two men hugging and discussing an “action plan” for overhauling federal energy regulations — when Perry publicly claimed he did not have a relationship with Murray. He was illegally fired and ordered to destroy the photographs.

Whistleblower Aid filed Mr. Edelman’s complaint with the US Office of Special Counsel, alleging that he was fired from the DOE for sharing “evidence of criminal corruption, obstruction of justice, and ethics violations” with the press.

As a direct result of Mr. Edelman’s disclosures, Perry’s proposed rule before the Federal Energy Regulatory Committee, needlessly subsidizing the coal industry, was voted down unanimously.

“…[T]here’s a great organization called Whistleblower Aid who’s there to protect people who want to expose law breaking without breaking the law. And they helped me out pro bono and they’re there for anybody else who wants to speak up and is afraid to. And this isn’t just a government issue, this is a private sector issue, too. If you see wrongdoing in any sector, you should feel free to speak up because you have the right to do so and there’s protections that can do that.” – Simon Edelman

- “He Leaked a Photo of Rick Perry Hugging a Coal Executive. Then He Lost His Job.” - The New York Times

- “A Whistle-Blower Alleges Corruption in Rick Perry’s Department of Energy” - The New Yorker

- “DOE staffer claims retaliation over photos of secret meeting” - Associated Press News

- “DOE staffer claims retaliation over photos of secret meeting” - CBS News

- “Rick Perry Hugged A Coal Baron. Photographer Got The Picture. Then He Was Placed On Leave.” - The Washington Post

Join our mailing list

Stay informed by email. Do NOT use your work email.

" * " indicates required fields

Media Contact: [email protected] Follow us on X @wbaidlaw

Latest News:

- Statement on Behalf of Whistleblower Aid Client Shannon Van Sant

- Response from Whistleblower Aid CEO Libby Liu to Harvard Kennedy School Statement

- Harvard Gutted Initial Team Examining Facebook Files Following $500 Million Donation from Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, Whistleblower Aid Client Reveals

- Los Angeles City Council Awards $1.8 million Settlement in Sexual Harassment Lawsuit, Vindicating Former Garcetti Aides Who Chose to Tell the Truth

- Reports of Horrifying Photos and Videos of Sexual Assaults of 50+ Victims Including an Infant by Serial Predator Underscores Urgent Need for Accountability and Reform of Tennessee Police Department

- Independent Audit of Johnson City Police Department Affirms Allegations of Kateri Dahl – former Special Assistant United States Attorney and Whistleblower Aid Client

PRIVACY POLICY

Truth Be Told: Unpacking the Risks of Whistleblowing

In 2018, HBS associate professors Aiyesha Dey and Jonas Heese wrote a case about a whistleblower at a multi-national gambling company who exposed financial misstatements, first to his manager and later to the US Securities and Exchange Commission. The case focused on the company’s response to the complaint, but the class discussion turned to the motivations of the man who revealed the wrongdoing.

Have you ever thought about blowing the whistle? Dey asked her students. Their response: We’ve thought about it, but it is so costly.

At a time when regulators and employers alike are increasingly relying on whistleblowers to prevent and investigate fraud, the professors realized, there is little understanding about the real risks faced by an employee who steps forward. Dey and Heese set out to study the experiences of about 2,400 whistleblowers who filed lawsuits under the False Claims Act, which rewards whistleblowers who report fraud against the federal government with a percentage of the money recovered. “We need to understand the costs,” explains Heese, “and how to empower the people who have important information to share that information.”

April White : Do you think regulators have the necessary tools to encourage people to come forward with information?

Jonas Heese : Our research focuses on specific legislation known as the False Claims Act, which was the first cash-for-information whistleblower law in the world. It goes back to the Civil War, and it has been adopted by modern regulators, such as the SEC whistleblower program [a similar program authorized in the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act], the DOT’s Motor Vehicle Safety whistleblower program, and more recently the Treasury’s anti-money-laundering whistleblower program that was passed into law in 2021.

"A lot of whistleblowers are fired. Some may need to move to another state or another industry to find a job, and they may not find a job at the same level."

The big thing is that “cash for information” may not be the right way to talk about it, because it comes across as if someone is making a lot of money without any costs. It’s more like an insurance payment. Whistleblowers incur a lot of costs and get some money as compensation. That changes how we think about whistleblower incentives; it isn’t a reward.

White : Is there abuse of these statutes?

Aiyesha Dey : The debate is about whether it is frivolous, disgruntled employees going to regulators for financial motives, or whether people are coming forward when it is needed and they just get compensated for some of the cost they incur.

Heese : The concern in most countries around the world, in many different types of whistleblower regimes, is that you will get all of these frivolous tips. Regulators and politicians are more willing to talk about laws prohibiting retaliation. But we can show that it’s very difficult to prevent retaliation just with provisions that say you are not allowed to retaliate. Ultimately, the most effective way to protect whistleblowers is to compensate them financially for the costs they incur. We also found that cash-for-information regimes do not increase the number of frivolous tips filed with regulators or change the probability that the employee whistleblower will first report the issue internally.

White: What risks do whistleblowers face?

Dey : There are social and emotional consequences, and there are also career consequences. A lot of whistleblowers are fired. Some may need to move to another state or another industry to find a job, and they may not find a job at the same level.

But when we expanded to a longer term, looking at a variety of consequences over time, we found that the amount of money whistleblowers get seems to compensate, on average, for the financial costs. When they receive financial compensation, the costs are not as high. A slight caveat is that our main findings are for lower-level employees, where the compensation for whistleblowing is a larger percentage of their lifetime earnings.

White : Why do whistleblowers contact regulators?

Heese : In our research, the reason that someone went to the regulator was not a financial motive. It was because their allegation was ignored. In almost two-thirds of the cases, the company just ignored the complaint. In another 10 percent of cases, the company is actually engaging in a cover-up. And then on top of that, some companies retaliate against the whistleblower, with firing being the most severe form of retaliation.

White : Should companies do more to encourage employees to report misdeeds internally?

Heese : Companies have to understand that their employees can be a big source of information for them, too. Whistleblower is a loaded term, but essentially what we’re talking about is how a company can create a culture where an employee feels comfortable telling a boss, “Oh, I just observed that no one is wearing a helmet in the factory. Maybe we should change that.” The upside for the organization when someone speaks up is that it can prevent additional costs or bigger fraud events.

"The problem is that the current structure incentivizes employees to report issues where the penalty is high."

Dey : There are a lot of issues that well-meaning managers and boards may not know about. There may be something bad going on in one subsidiary, or one factory, or with one supervisor. If there is a way that the firm can know about such things, they can resolve it internally more quickly and in a more efficient way than if it goes to regulators.

Although we don’t study this, I think it could also empower employees to feel ownership of the company because they’re helping in the overall growth and productivity of the firm. On the flip side, it could create—again, we haven’t tested this—distrust among employees. But, in general, having employees with the right ethics and values, who come forward when they see something, can actually help companies overall.

White : How could these statutes and policies be improved?

Heese : These statutes are effective in terms of getting the right information in a financially sound way. The problem is that the current structure incentivizes employees to report issues where the penalty is high. For a workplace safety violation, the penalty can be as low as $5,000. A percentage of that may not be enough to encourage an employee to report it. At the same time, we know that thousands of workers still die or get injured due to workplace safety violations. But in securities fraud or tax fraud, where the penalties can be in the millions, it makes more sense.

White : What is next in your research?

Dey : It would be interesting to understand the other avenues of motivating employees to come forward. To do that, we would need to study to what extent the environment within a company or specific society plays a role. What elements of corporate culture could empower employees to take ownership and report possible fraud? What kinds of internal control levers, employee training programs, or perhaps even internal (nonfinancial) rewards and recognitions lead to a greater number of internal whistleblower reports? Subject to data availability, we would also be interested in studying the types and levels of financial and nonfinancial incentives that can encourage whistleblowing at the senior management levels.

This article originally appeared in the HBS Alumni Bulletin .

[Image: iStockphoto/mustafagull]

- 24 Jan 2024

Why Boeing’s Problems with the 737 MAX Began More Than 25 Years Ago

- 02 Apr 2024

- What Do You Think?

What's Enough to Make Us Happy?

- 25 Jan 2022

- Research & Ideas

More Proof That Money Can Buy Happiness (or a Life with Less Stress)

- 01 Apr 2024

- In Practice

Navigating the Mood of Customers Weary of Price Hikes

- 25 Feb 2019

How Gender Stereotypes Kill a Woman’s Self-Confidence

- Values and Beliefs

- Corporate Accountability

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Advertisement

What Makes You a Whistleblower? A Multi-Country Field Study on the Determinants of the Intention to Report Wrongdoing

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 25 March 2022

- Volume 183 , pages 885–905, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Hengky Latan 1 ,

- Charbel Jose Chiappetta Jabbour ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6143-4924 2 , 3 ,

- Murad Ali 4 ,

- Ana Beatriz Lopes de Sousa Jabbour 3 , 5 &

- Tan Vo-Thanh 6

9607 Accesses

7 Citations

19 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

A Correction to this article was published on 07 April 2022

This article has been updated

Whistleblowers have significantly shaped the state of contemporary society; in this context, this research sheds light on a persistently neglected research area: what are the key determinants of whistleblowing within government agencies? Taking a unique methodological approach, we combine evidence from two pieces of fieldwork, conducted using both primary and secondary data from the US and Indonesia. In Study 1, we use a large-scale survey conducted by the US Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB). Additional tests are conducted in Study 1, making comparisons between those who have and those who do not have whistleblowing experience. In Study 2, we replicate the survey conducted by the MSPB, using empirical data collected in Indonesia. We find a mixture of corroboration of previous results and unexpected findings between the two samples (US and Indonesia). The most relevant result is that perceived organizational protection has a significant positive effect on whistleblowing intention in the US sample, but a similar result was not found in the Indonesian sample. We argue that this difference is potentially due to the weakness of whistleblowing protection in Indonesia, which opens avenues for further understanding the role of societal cultures in protecting whistleblowers around the globe.

Similar content being viewed by others

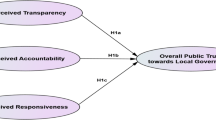

Public Trust in Local Government: Explaining the Role of Good Governance Practices

Taye Demissie Beshi & Ranvinderjit Kaur

Inaction and public policy: understanding why policymakers ‘do nothing’

Allan McConnell & Paul ’t Hart

Reflections on Criminal Justice Reform: Challenges and Opportunities

Pamela K. Lattimore

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A number of government scandals that have emerged in the news media over the past several years have involved whistleblowers who spoke out against perpetrators of wrongdoing, leading to such wrongdoing being widely recognized by both the public and stakeholders. For instance, evidence that whistleblowers played an important role in letting the world know about the gravity of the coronavirus outbreak in China reveals the unique way in which whistleblowers are shaping contemporary society. Another example is the affair known as the Trump-Ukraine scandal, which occurred in the US and involved an officer of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) who reported an abuse of power in the form of an attempt to encourage an investigation into Joe Biden, Trump’s political opponent in the 2020 US presidential election. Another famous instance of whistleblower activity is the case of Edward Snowden, who leaked a number of classified National Security Agency (NSA) documents that were meant to be kept secret (Archambeault & Webber, 2015 ; Latan et al., 2018 ).

However, a recent study conducted by the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE) in 2020 reported that occupational fraud occurring in government and the public administration sector has increased dramatically, especially cases of corruption, followed by white collar crime, conspiracy, money laundering, abuse of power and others (ACFE, 2020 ). To date, little attention has been devoted to studying this area. Previous studies by Roberts et al. ( 2011 ) have provided a guide for managing internal reporting of wrongdoing in the public sector, while the work of Brown and Lawrence ( 2017 ) has reported on the strength of organizational processes for responding to staff wrongdoing concerns in the public sector. However, the persistent gap regarding the determinants of whistleblowing in government agencies remains to be fully explored (Mesmer-Magnus & Viswesvaran, 2005 ; Miceli & Near, 2005 ). Given that whistleblowing plays a pivotal role in facilitating the reform of government agencies and is often seen as consistent with serving the public or society at large (Caillier, 2017b ; Cho & Song, 2015 ), it is important to investigate the relevant factors that encourage whistleblowers to speak up upon observing wrongdoing. Therefore, this research aims to fill this persistent gap and examines the determinants of whistleblowing within government agencies.

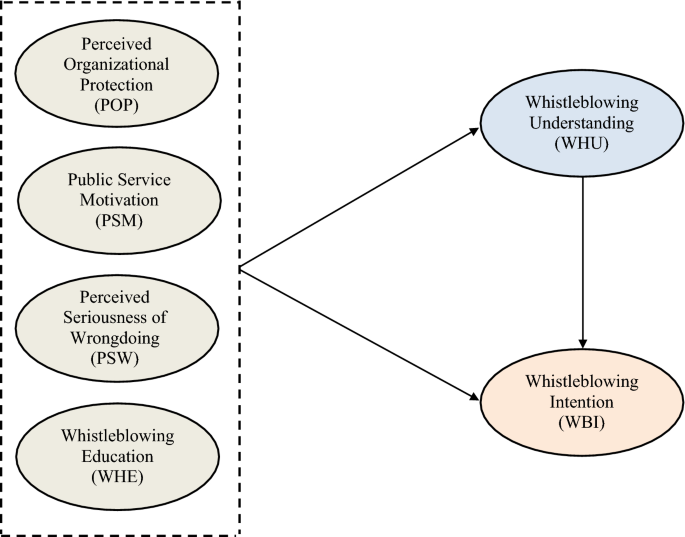

As highlighted in a number of recent studies synthesizing the relevant literature (Culiberg & Mihelič, 2017 ; Gao & Brink, 2017 ), there is a large number of existing studies that have investigated individual, situational and organizational factors associated with whistleblowing in the private sector and for-profit organizations (e.g., attitude, personal responsibility, sense of morality, perceived seriousness of wrongdoing, motivation to obtain monetary reward, organizational support, retaliation, wrongdoer power, etc.). Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether these factors will have similar or different effects in relation to blowing the whistle when applied in the public sector and non-profit organizations (Cassematis & Wortley, 2013 ; Nayır et al., 2018 ; Scheetz & Wilson, 2019 ). Furthermore, as indicated in previous studies, there are several critical missing links regarding the relationships between these variables that have not yet been studied thoroughly, which has resulted in a lack of insight in this area and calls for further investigation. As far as we are aware, little attention has been paid by whistleblowing scholars to the overlapping nature of factors such as perceived organizational protection (POP), public service motivation (PSM), perceived seriousness of wrongdoing (PSW) and whistleblowing education (WHE) in influencing observers to speak up about misconduct within government agencies.

Although whistleblowers are often regarded as ‘heroes’ for defending the public interest, they are not infrequently also considered ‘traitors’ for revealing wrongdoing in an organization. A study conducted by Miceli and Near ( 2013 ) reports that the involvement of whistleblowers in uncovering misconduct in government agencies has tended to increase over time (Miceli & Near, 2005 ). Unfortunately, retaliation against whistleblowers has followed the same pattern (Near & Miceli, 2016 ), with most observers of wrongdoing admitting that they have experienced retaliation. Several studies have documented retaliation against whistleblowers, with consequences ranging from mild to severe, such as being treated unfairly, bullying from co-workers, experiencing verbal harassment and being laid off from work, all of which disturb the mental health of whistleblowers (Latan et al., 2021 ; Park & Lewis, 2018 ; Rehg et al., 2008 ; van der Velden et al., 2019 ). However, one factor that has not been well studied with regard to mitigating such retaliation is organizational protection (Chordiya et al., 2020 ). We define perceived organizational protection (POP) as the efforts made by an organization to protect its members from various potential threats when they have decided to blow the whistle. On one hand, an observer will feel comfortable and confident in blowing the whistle when he or she believes that they will be protected after speaking out. On the other hand, when protection is weak or non-existent, an observer may choose to remain silent when considering the potential risks that threaten his or her personal and professional life (Izraeli & Jaffe, 1998 ; Latan et al., 2021 ; MacGregor & Stuebs, 2014 ). Hence, POP can be seen as a security system which increases whistleblowing intention (WBI).

Furthermore, there are other related questions which arise, such as why whistleblowers decide to sacrifice themselves for the public interest, and what motivates them to expose wrongdoing in government agencies? According to Roberts ( 2014 ), motivational factors related to the public interest are prominent within government agencies; this includes public service motivation (PSM) and desire to help victims as a result of the perceived seriousness of wrongdoing (PSW) (e.g., fraud, theft, breaches of code of conduct, misuse of allowances or falsification of records). We define PSM as an individual’s orientation toward providing services to people with the aim of serving the public and the wider community. With regard to whistleblowing, PSM can trigger an individual to reveal wrongdoing when it is related to others’ survival. PSM is often associated with an altruistic motive that plays a pivotal role in explaining the intention behind whistleblowing (Caillier, 2017b ; Cho & Song, 2015 ; Ugaddan & Park, 2019 ). In certain situations, PSM encourages observers to sacrifice themselves for the public good. We define PSW as an observer’s assessment of the magnitude of the consequences generated by illegal, immoral or illegitimate practices (Latan et al., 2021 ; Rehg et al., 2008 ). In this regard, the higher the potential impact of wrongdoing on the wider community, the higher the likelihood of observers speaking up. More precisely, whistleblowers often speak up about misconduct which is deemed to have a significant negative impact on the public (e.g., to preserve valuable resources, protect people’s rights and lives or enforce the rule of law). In other words, more serious wrongdoing has greater potential to be reported.

According to the ACFE ( 2020 ) report, whistleblowing education (WHE) has received little attention from stakeholders in various organizations, including government agencies. This suggests the possibility that an observer who has witnessed misconduct in the workplace may not know how or to whom to report it (Culiberg & Mihelič, 2017 ; Vandekerckhove & Lewis, 2012 ). As Caillier ( 2017a ) argues, scant attention has been devoted to dealing with WHE, and it is still unclear how this factor relates to the intention to blow the whistle. We argue that the lack of WHE has serious implications for whistleblowers’ understanding (WHU) and intention to report wrongdoing. In addition, WHE is considered a vehicle that speeds up the whistleblowing process. WHE can help observers when faced with ethical dilemmas; that is, when wrongdoers hold positions of power in organizational structures (such as supervisors or top-level management). In this context, WHE guides observers regarding how to report their findings without fear of retaliation (e.g., using anonymous channels). Therefore, the existence of WHE has the potential to trigger observers to blow the whistle within government agencies.

Motivated by the aforementioned context, we conducted two original field studies, using employees working for government agencies as a sample. We took samples from two countries—the US and Indonesia—with the aim of potentially increasing the generalizability of our findings. In Study 1, we used data from a large-scale survey conducted by the US Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB). The aim of Study 1 is to empirically test the determinants of whistleblowing in US government agencies (i.e., POP, PSM, PSW and WHE). Specifically, the MSPB data allow us to examine relationships between variables that have not been explored in previous studies. As has been shown in previous studies in this field (Miceli & Near, 1984 , 1989 , 2002 ), the MSPB survey has significant consequences for the reform of government agencies in the US. In Study 2, we replicated Study 1’s format, in order to examine relationships between variables that have not been explored by previous studies using primary data from an Indonesian sample. We found a slight difference between the two sample groups, indicating unexpected findings which can be explained by differences in societal culture and whistleblowing protection acts (WPA).

Our study extends the state-of-the-art research in the field of whistleblowing and provides new insight for this body of knowledge in two ways. First, our research broadens the scope of whistleblowing in the fields of government and public administration, as reported by several previous scholars (Brown & Lawrence, 2017 ; Miceli & Near, 2002 ; Roberts et al., 2011 ). Specifically, this is one of the first empirical studies to consider the latest MPBS survey in examining the relationships between variables using a very large sample size. To our knowledge, recent studies that have used datasets from the MPBS survey are relatively scarce. We note that studies by Ugaddan and Park ( 2019 ), Dungan et al. ( 2019 ), Caillier (2017ab), and Cho and Song ( 2015 ) have used the MBPS survey; however, these works do not fully explore its potential for exploring relationships between variables. For example, Dungan et al. ( 2019 ) and Caillier ( 2017a ) only consider ‘simple relationships’ between variables (i.e., between predictors and outcomes). In addition, the studies by Ugaddan and Park ( 2019 ), Caillier ( 2017b ) and Cho and Song ( 2015 ) only consider a selection of variables individually.

Second, the present research does not depend on a single study. Based on our best knowledge, the use of multiple studies in whistleblowing research is relatively rare. In contrast to previous studies, which rely solely on the MPBS survey, our study uses two field studies to enrich our findings (Miceli & Near, 2002 ). Therefore, our results provide external validity and a higher potential for the generalization of findings. In addition, this work also answers recent calls by Vandekerckhove et al. ( 2014 ) and Latan et al. ( 2021 ) to conduct cross-cultural comparative studies; in our case between the US and Indonesia.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The next section presents the theoretical background and development of hypotheses, followed by the research methodology. Following this, the empirical results are presented. Finally, the results are discussed and implications for both academics and practitioners are given.

Theoretical Background and Development of Hypotheses

Whistleblowing in the public sector.

Recently, whistleblowing has come to receive attention from many organizations, including governments and the public administration sector. Although previous studies have noted the virtuousness of whistleblowing and its positive impacts for society at large (Apaza & Chang, 2017 ; Lewis et al., 2014 ; Miceli et al., 2008 ; Vaughn, 2012 ), recent developments indicate that ‘blowing the whistle’ has not been an easy feat in the public sector (Brink et al., 2017 ; Miceli & Near, 2013 ). Taking whistleblowing action against government agencies, who are some of the largest employers and also those who hold the most power in a given country, is undoubtedly not always an easy decision to make (Lewis, 2015 ; Vandekerckhove & Lewis, 2012 ). However, the important role played by whistleblowing in the public sector has several arguments in its favor. First and foremost, within a good system of governance, the public sector can be the most important part of a country’s economy and affects the overall life of the society. Therefore, disclosure of wrongful activities in public sector organizations has the potential benefit of saving people’s lives. In addition, this type of action helps to stop the damage caused by wrongdoing and restore public trust. In some cases, whistleblowing actions can help Presidents, Congresses, agency leaders and/or other decision makers to improve existing systems and identify weaknesses in government agencies. Second, since the public sector is involved in providing services to citizens, disclosure of illegal, immoral and illegitimate acts helps to improve the effectiveness of services (Miceli & Near, 2013 ). In this regard, such disclosure can mean protecting millions of dollars and reducing service costs to create good governance.

The public sector has certain specific characteristics that should be taken into account when understanding the act of whistleblowing. This sector tends to be more centralized and to have a more hierarchical management structure than the private sector. This characteristic may influence the willingness of public sector employees to speak out against wrongdoing. Another feature of the public sector is the degree of political control over this sector, which may influence bureaucratic behaviors and thus, perhaps, public employees’ whistleblowing decisions. Thus, it is important to conduct research considering the public sector, due to its particular characteristics (Lee, 2020 ).

As Miceli and Near ( 2013 ) argue, the whistleblowing process in the public sector may involve a different route and scope from the private sector. However, based on a broad definition, whistleblowing constitutes the disclosure by members of an organization (including former members and job applicants) of illegal, immoral, or illegitimate practices (including omissions) by the employer, to persons or organizations who may be able to effect action (Near & Miceli, 1985 ). We argue that the above definition can be applied in both the private and public sectors. In the public sector, the whistleblowing process may involve many stages, and the disclosure of wrongdoing in this sector is specifically regulated by federal law and controlled by the relevant authorities. Furthermore, the scope of wrongdoing may differ in the public sector, given the differences in workplace activity. For example, according to the ACFE ( 2020 ) report, misconduct that occurred in the private sector included the misappropriation of assets and fraudulent financial statements. Meanwhile, misconduct that occurred in the public sector included corruption, embezzlement, abuse of power and others. In certain instances, governmental dishonesty or the illegal behavior of government agencies may in fact encourage whistleblowing action.

On the other hand, whistleblowing in the context of the public sector is often associated with a prosocial perspective; that is, behavior which is intended to benefit others as well as oneself (Alford, 2001 ; Dozier & Miceli, 1985 ).

Different countries have taken different approaches toward incentivizing the act of speaking out. For example, there are more than 40 pieces of legislation concerning whistleblowing provisions across many jurisdictions in the US, showing that whistleblowing is a widespread cultural phenomenon in this country. However, in other countries, such as Indonesia, there is a lack of law enforcement related to retaliation against whistleblowers. In addition, in countries such as Indonesia, whistleblower protection systems and laws relating to whistleblowing have not been fully regulated. Although government agencies in Indonesia do already have a whistleblowing system in place, it is limited to internal cases. Thus, it is pertinent to consider whether the whistleblower protection measures in place in a given country may relate to whistleblowing intention (WBI). In other words, it is relevant to assess the situation in different countries in terms of whistleblower protection and cultural aspects of the sample context, as in this article.

Perceived Organizational Protection Affecting Whistleblowing