An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Twenty-Five Years of Social Media: A Review of Social Media Applications and Definitions from 1994 to 2019

Thomas aichner , phd, matthias grünfelder , msc, oswin maurer , phd, deni jegeni , bsc.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Address correspondence to: Prof. Dr. Oswin Maurer, Faculty of Economics and Management, Free University of Bozen-Bolzano, Piazza Università 1, 39100 Bozen-Bolzano, Italy [email protected]

Issue date 2021 Apr 1.

This Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons License [CC-BY] ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

In this article, the authors present the results from a structured review of the literature, identifying and analyzing the most quoted and dominant definitions of social media (SM) and alternative terms that were used between 1994 and 2019 to identify their major applications. Similarities and differences in the definitions are highlighted to provide guidelines for researchers and managers who use results from previous research to further study SM or to find practical applications. In other words, when reading an article about SM, it is essential to understand how the researchers defined SM and how results from articles that use different definitions can be compared. This article is intended to act as a guideline for readers of those articles.

Keywords: social media, social networks, social media definition, social media applications, literature review

Introduction

The term “social media” (SM) was first used in 1994 on a Tokyo online media environment, called Matisse. 1 It was in these early days of the commercial Internet that the first SM platforms were developed and launched. Over time, both the number of SM platforms and the number of active SM users have increased significantly, making it one of the most important applications of the Internet.

With a similarly fast pace, businesses have moved their marketing interests toward SM platforms. The presence of both businesses and users on SM has further led to a shift in how companies interact with their customers, who are additionally no longer limited to a passive role in their relationship with a company. 2 Customers give feedback, ask questions, and expect quick and customized answers to their specific problems. In addition, customers post text, pictures, and videos. Managers came to the understanding that the brand transition to SM ultimately involves a re-casting of the customer relationship, where the customer has become an ally or an enemy, not an audience. 3

In research, SM is generally used as an umbrella term that describes a variety of online platforms, including blogs, business networks, collaborative projects, enterprise social networks (SN), forums, microblogs, photo sharing, products review, social bookmarking, social gaming, SN, video sharing, and virtual worlds. 4 Given this broad spectrum of SM platforms, the applications of SM are quite diverse and not limited to sharing holiday snapshots or advertising and promotion.

As of January 2020, there are more than 110,000 publications that have the term “social media” in their title. Over the past 25 years in which these works were published, countless researchers have formulated quite varying definitions of SM—sometimes using alternative terms. In this period, the perceptions and understanding of what SM is, what it includes, and what it represents have also varied considerably. This can make it difficult for both researchers and companies to interpret and apply research findings; for example , when referring to SM in general, rather than referring to a specific type of SM, such as SN. It can be problematic to quote previous research that was carried out exclusively on one SM platform as being generalizable to SM, or to refer to results from research that defined SM as being more or less inclusive in terms of which platforms qualify as SM and which do not.

Major Applications of SM

This section serves as the background of SM functions, rather than how the definition has changed. It provides a general, although not comprehensive, overview of some of the most important applications of SM over the past two and a half decades. This is important, as it highlights that SM cover a broad variety of scopes with specific functions and applications that can differ greatly between the different types of SM. Consequently, also the purpose and the users' perceived value of using SM varies. From a research perspective, this section serves as a foundation for classifying and discussing the SM definitions that are presented in the following chapters.

Socializing with friends and family

Although not all SM platforms are specifically designed to facilitate socialization between its users, it may be considered one of the most apparent commonalities of all types of SM. 4 Sometimes referred to as online communities, these SM platforms are valuable given that people often do not perceive a difference between virtual friends and real friends, as long as they feel supported and belong to a community of like-minded individuals. 5 The SM helps to strengthen relationships through the sharing of important life events in the form of status updates, photos, etc., reinforcing at the same time their in-person encounters as well. 6

The SM has also become a common tool for communication in families. A study conducted by Sponcil and Gitimu 7 showed that for 91.7 percent of students the main reason for using SM is communicating with family and friends. In addition, 50 percent of the students communicated with their family and friends every day, and another 40 percent at least a few days a week. Williams and Merten 8 suggest that by using SM in everyday life, people strengthen the relationships with family. Especially in relation to globalization and constant migration, it has become a vital tool for maintaining contact within migrant families. The need for transnational communication between family members and the people they left behind is of great importance. 9

Romance and flirting

Several studies suggest that SM significantly influences the romantic aspects of life. Aside from facilitating human interaction, communication technologies are also shaping and defining our relationships. 10 It has been shown that SM is important in the starting phases of a relationship and has a significant influence on the relationship of many couples in the long run. 11 The SM can help when starting a romantic relationship, for example , contacting a crush through SM can have special benefits for introverts, who otherwise would avoid face-to-face contact and would otherwise communicate less. 7 Moreover, in some cases, online dating is preferable to live dating, as it gives the same feeling and allows users to avoid unnecessary discomforts. 11 Finally, rejection on SM is less painful compared with face-to-face rejection. 10 Further, users can contemplate their responses and do not have to worry about their physical appearance while conversing/chatting online, making it a less stressful environment to flirt with people on SM than face-to-face conversations. 12

Interacting with companies and brands

It is estimated that close to 100 percent of larger companies (both B2C and B2B) are using some sort of SM platform to inform their customers, gather information, receive feedback, provide after-sales service or consultancy, and promote their products or services. The key characteristic that makes SM so relevant for companies is the fact that SM allows for two-way communication between the brand and the customer. 13 Sometimes referred to as “social customer relationship management,” 14 SM can be viewed as an effective tool used to get closer to the customer. However, some studies suggest that what customers seek is somewhat different from what companies offer through SM. 14 Customers are mainly interested in communicating easily and quickly with the company. From a business perspective, the company wants to make sure customers receive the right information in a timely manner, linking the customer closer to the brand and, simultaneously, controlling the flow of information. Successful SM managers understand how an SM platform works and is used by its customers, and they then develop corporate communication tools that fit the behavior of their users. Many researchers highlight the need for customer relationship management to adapt to the rise of SM 2 to efficiently manage relationships with modern, connected, and empowered customers.

Job seeking and professional networking

Another application of SM is to connect job seekers with employers. The vast majority of Fortune 500 companies use LinkedIn for talent acquisition. 15 With more than 660 million users in 2020, it is an important tool for companies searching to expand their talent pool. This pool of individuals is extended, as the nature of SM also allows recruiters to identify and target, apart from active users, talented candidates who are passive or semi-passive and lure them to prospective job positions. 16 In fact, through SM platforms such as LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter, recruiters can post job advertisements to lure potential applicants who are not actively looking for a job. 17 Rather than the costly and time-consuming traditional ways of staffing with interviews and tests, hiring through SM offers recruiters the benefit of free access to prospects' profiles and an instant means of communication. For users, LinkedIn profiles allow them to create an idealized portrait by displaying their skills to recruiters and peers. 18 Indeed, LinkedIn asks members to highlight their relevant skills, promoting their abilities and strengths, urging them to complete their profiles through getting recommendations and praise from peers/colleagues and clients for their performance or skills. 19

Doing business

The SM has a considerable impact on how companies approach clients and vice versa. In addition, SM utilizing SM as a means of understanding and informing customers has become imperative for businesses to remain competitive. The SM providers have created possibilities for companies to improve their internal operations and communicate in new ways with customers, other businesses, and suppliers. 20 At the same time, companies can actively engage customers, encouraging them to become advocates of their brands. 2 This is certainly important, as users can create online customer communities, which potentially add value to the brand beyond just increased sales. 20 The engagement of customers can be beneficial, as they will frequently interact with the brand and share positive word-of-mouth since they have become more emotionally attached to the brand. 21 This electronic word-of-mouth created in SM communities helps consumers in their purchasing decisions. 22 This suggestion is important given that customers are actually more interested in other users' recommendations and word-of-mouth rather than the vendor-created product information. 23

Research questions

Reviewing the existent literature about SM applications inevitably leads to the question of whether the researchers had the same definition in mind when talking about SM, SN, online communities, and the like. It is also apparent that the focus of the researcher's interest has changed over time, and that the time when the research was conducted could have an impact on how the findings should be interpreted. Therefore, the remainder of this article aims at answering the following research questions (RQ):

RQ1: How has the definition of social media changed from 1994 to 2019? RQ2: What are the differences and commonalities in social media definitions from 1994 to 2019?

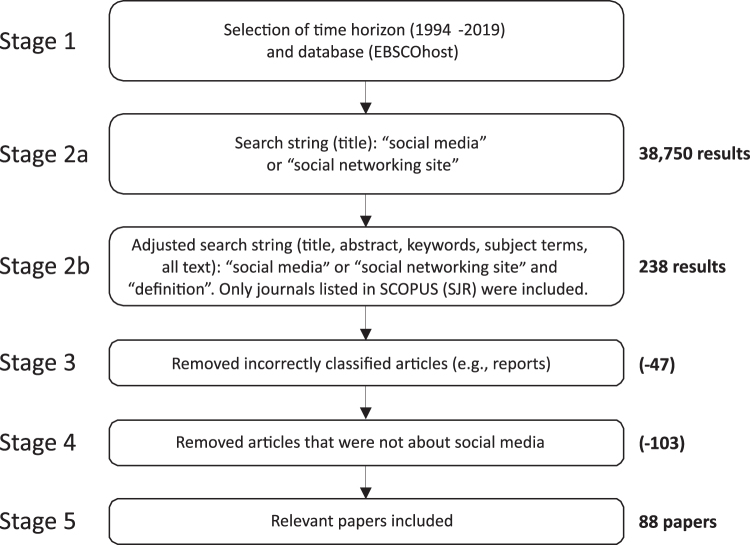

To answer the two RQ, we decided to conduct a systematic literature review (SLR). Using a multi-step SLR approach as recommended by Tranfield et al. 24 ( Fig. 1 ), we structurally examined the literature between 1994 and 2019 to find all relevant SM definitions to identify the major differences and commonalities.

Structure and process of the systematic literature review.

After identifying 88 potential papers, all the articles were read to find original definitions for SM or related terms. In addition, we used backward and forward snowballing, two methods frequently employed in academic research to find additional relevant sources based on the references used in the original publication (backward snowballing) and searched papers that cited the article (forward snowballing), respectively. 25 In combination with the SLR, the backward snowballing led to the identification of a total number of 21 original definitions, including some definitions that were published in books and conference proceedings, which were not included in the SLR.

In this chapter, we present all major definitions of SM (and synonymous terms) that were formulated from 1994 to 2019 ( Table 1 ). Table 1 further includes details about the source and the number of citations according to Google Scholar as of August 2020.

Social Media Definitions with Author Names, Source, and the Number of Citations As of August 2020

Before we assess the meaning and compare the definitions in terms of the two RQ, a few quantitative results are provided. Analyzing the 21 definitions, we found a lexical density (i.e., the percentage of nouns, adjectives, verbs, and adverbs) of 57.5 percent. The most frequently used word with 23 occurrences is “social,” followed by “people” with 12 occurrences, and “virtual,” “content,” “user,” and “network” with 8 occurrences each. In terms of two-word phrases, “social network[s]” (8 occurrences) is followed by “social media” and “social networking” (5 occurrences each), as well as “virtual communities” (VC) (4 occurrences).

Notably, the first formal definition is from 1996 and uses “computer-supported social networks” or “CSSNs,” although the term “SM” was coined about 2 years earlier. Later, researchers used different terms such as “virtual communities,” “social networks,” “social networking services,” “online social network,” “social networking sites,” “social network sites,” and “social media.” Although there are small variations in these terms, they can be classified into three categories: VC, SN, and SM. It is important to mention that all these definitions describe the same concept, but with different terms. Assessing the SM definitions that resulted from the SLR reveals that from 1997 to 2002, VC was the dominant term. In contrast, SN was used over a longer period, but it was dominant from 2005 to 2009. It was only in 2010 that researchers started using predominantly SM. But how did the definitions—independent from their terminology—change?

Throughout the observed period, the role of SM, as an enabler for human interaction as well as an avenue to connect with other users, has been a constant in defining SM. In early definitions, the focus was mainly on people and how people interact, whereas later definitions (after 2010) have largely substituted the term “people” with “user” and placed more focus on generating and sharing content. This changed focus, with regard to both the application of SM and the terminology of people versus user, may also reflect the increasingly important role of anonymity in SM. 47

The role of user-generated content is not reflected in early definitions, whereas it has become a central part of recent definitions. It was Kaplan and Haenlein 38 who first mentioned “creation,” whereas later definitions use terms such as “user-supplied content” and “user-driven platforms” in addition to “user-generated content,” which is the common term used in research and practice today.

Another notable change is that until 2009, several researchers included the common interests that linked people with each other, whereas this link is completely missing in post-2010 definitions. Again, this may be reflected by the fact that in the early days, SM users were mostly close or loosely related friends communicating with each other, whereas in recent years, SM has evolved to a set of media that are also used as a powerful tool by companies, celebrities, and influencers to reach the masses. 48

Finally, although sharing information and content is generally not the central aspect in defining SM, the terminology has changed over time. Until 2010, researchers used “exchange” or “upload,” which were substituted with the term “share” in subsequent years. The underlying meaning, however, remained the same.

Conclusions

About 60,000 articles have cited the SM definitions summarized in this article. Therefore, the value this research provides goes beyond a simple overview of the definitions and major applications of SM in the 25 years, since the term was originally coined. The result is a timeline of SM definitions that helps researchers and practitioners to quickly put the results of previous research in perspective and to avoid time-consuming research of the single definitions in different papers. Why is this necessary? This is because, based on the definition, the results may need to be interpreted in a more or less different way.

One notable result is that, although SM is one of the main research areas in social sciences (and beyond) and its landscape has been changing quickly, only a handful of scholars have made an effort to develop a definition of SM. Although some elements, for example , the fact that SM connects people, are common, the definitions are rather different from each other. The commonalities and differences highlighted in the previous section allow for the division of the definitions into two main streams: those published before 2010 and after 2010. Before 2010, SM was commonly approached as a tool of connectivity for people with common interests. After 2010, the focus changed to creating and sharing user-generated content.

These results are in line with previous research about the evolution of SM literature, which concluded that SM definitions changed over time, namely from platforms for socializing in the past to tools for information aggregation. 45 Similarly, Kapoor et al. 45 found that there was an evolution in SM definitions and a cut in the early 2010. Our research shows that there is no single or commonly accepted definition, but that several definitions have been co-existing and found broad acceptance in literature.

Future SM researchers can use these findings to better compare SM articles and avoid flaws in their theory or methodological design. Especially when comparing the results of empirical studies, it may be critical to consider both when the study was conducted and which SM definition was used as a basis for hypothesis development and data analysis. In addition, this article gives SM researchers the possibility to make an informed choice of which SM definition to use for their studies.

Given the method employed to identify the SM definitions, we are confident that this is the most comprehensive overview that includes all major publications. However, the results may be limited by the original search terms used to identify the papers to be included in the SLR. Although the use of backward snowballing should have helped in minimizing this risk, there may still be some less explicit definitions of SM that were not included in this article. In addition, non-English articles and other gray literature were not considered, which is common criticism in academic research. Future research could also try to identify the differences in how SM is defined by researchers from different scientific backgrounds, for example , marketing versus medicine versus psychology versus anthropology versus engineering versus information technology. It would also be insightful to see whether there are tendencies of certain researchers, for example , from engineering, to base their research on specific definitions rather than on others. For example, if one definition is dominant in engineering but not in medical research, this would imply that interdisciplinary research about SM applications needs to be compared more carefully, as the basic definition differs. Similarly, it would be interesting to link the use of SM definitions to the cultural or national context of where the research was carried out, for example , to identify whether European versus American versus Asian researchers have a generally different understanding of SM and its applications. These possible cultural differences in the definition or selection of an SM definition as a basis for research could be linked to the fact that in different countries and cultural clusters different SM platforms are more or less popular. 49 Overall, our research will help compare findings from SM literature more easily and avoid misinterpretations of past and future research.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This work was supported by the Open Access Publishing Fund of the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano.

- 1. Bercovici J. (2010) Who coined social media? Web pioneers compete for credit. Forbes. http://forbes.com/sites/jeffbercovici/2010/12/09/who-coinedsocial-media-web-pioneers-compete-for-credit/2/ (accessed Aug. 1, 2020)

- 2. Malthouse EC, Haenlein M, Skiera B, et al. . Managing customer relationships in the social media era: introducing the social CRM house. Journal of Interactive Marketing 2013; 27:270–280 [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Som A, Blanckaert C. (2015) The road to luxury: the evolution, markets, and strategies of luxury brand management. Singapore, Singapore: John Wiley and Sons Singapore Pte. Ltd [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Aichner T, Jacob F. Measuring the degree of corporate social media use. International Journal of Market Research 2015; 57:257–276 [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Lazakidou AA. (2012) Virtual communities, social networks and collaboration. New York: Springer [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Barkhuus L, Tashiro J. (2010) Student socialization in the age of facebook. In Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. New York: ACM Press, pp. 133–142 [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Sponcil M, Gitimu P. Use of social media by college students: relationship to communication and self-concept. Journal of Technology Research 2013; 4:1–13 [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Williams AL, Merten MJ. iFamily: internet and social media technology in the family context. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal 2011; 40:150–170 [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Parreñas RS. Children of global migration: transnational families and gendered woes. Canadian Journal of Sociology Online 2005; 224–225 [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Fox J, Warber KM. Romantic relationship development in the age of facebook: an exploratory study of emerging adults' perceptions, motives, and behaviors. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 2013; 16:3–7 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Papp LM, Danielewicz J, Cayemberg C. “Are we facebook official?” Implications of dating partners' facebook use and profiles for intimate relationship satisfaction. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 2012; 15:85–90 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Suler J. The online disinhibition effect. CyberPsychology and Behavior 2004; 7:321–326 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Lyon TP, Montgomery AW. Tweetjacked: the impact of social media on corporate greenwash. Journal of Business Ethics 2013; 118:747–757 [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Baird HC, Parasnis G. From social media to social customer relationship management, Strategy and Leadership 2011; 39:30–37 [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Fertig A. (2017) How Headhunters Use LinkedIn to Find Talented Candidates. https://money.usnews.com/money/blogs/outside-voices-careers/articles/2017-05-05/how-headhunters-use-linkedin-to-find-talented-candidates (accessed Aug. 1, 2020)

- 16. Koch T, Gerber C, De Klerk JJ. The impact of social media on recruitment: are you linkedIn? SA Journal of Human Resource Management 2018; 16:1–14 [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Sinha V, Thaly P. A review on changing trend of recruitment practice to enhance the quality of hiring in global organizations. Journal of Contemporary Management Issues 2013; 18:141–156 [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. van Dijck J, Poell T. Understanding social media logic. Media and Communication 2013; 1:2–14 [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Chiang JK-H, Suen H-Y. Self-presentation and hiring recommendations in online communities: lessons from LinkedIn. Computers in Human Behavior 2015; 48:516–524 [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Culnan MJ, McHugh PJ. How large U.S. companies can use twitter and other social media to gain business value. MIS Quarterly Executive 2010; 9:243–259 [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Dholakia UM, Durham E. One café chain's facebook experiment. Harvard Business Review 2010; 88:26 [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Pan L-Y, Chiou J-S. How much can you trust online information? Cues for perceived trustworthiness of consumer-generated online information. Journal of Interactive Marketing 2011; 25:67–74 [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Ridings CM, Gefen D. Virtual community attraction: why people hang out online. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 2004; 10:1–10 [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Tranfield D, Denyer D, Smart P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British Journal of Management 2003; 14:207–222 [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Schön EM, Thomaschewski J, Escalona MJ. Agile requirements engineering: a systematic literature review. Computer Standards and Interfaces 2017; 49:79–91 [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Wellman B. Computer networks as social networks: collaborative work, telework, and virtual community. Annual Review of Sociology 1996; 293:2031–2034 [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Romm C, Pliskin N, Clarke R. Virtual communities and society: toward an integrative three phase model. International Journal of Information Management 1997; 17:261–270 [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Garton L, Haythornthwaite C, Wellman B. Studying online social networks. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 1997; 3:1–32 [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Hagel J. Net gain: expanding markets through virtual communities: Journal of Interactive Marketing 1999; 13:55–65 [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Balasubramanian S, Mahajan V. The economic leverage of the virtual community. International Journal of Electronic Commerce 2001; 5:103–138 [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Ridings CM, Gefen D, Arinze B. Some antecedents and effects of trust in virtual communities. Journal of Strategic Information Systems 2002; 11:271–295 [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Marwick AE. (2005) I'm a lot more interesting than a friendster profile’: identity presentation, authenticity and power in social networking services. In Association for Internet Researchers 6.0. Chicago, IL: Association for Internet Researchers, pp. 1–26 [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Acquisti A, Gross R. (2006) Imagined communities: awareness, information sharing, and privacy on the facebook. In Danezis G, Golle P, eds. Privacy enhancing technologies. Berlin, Germany: Springer, pp. 36–58 [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. O'Murchu I, Breslin JG, Decker S. (2007) Online social and business networking communities. In Gopalan S, Taher N, eds. Viral marketing: concepts and cases. Washington, DC: DERI Technical Report, pp. 53–80 [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Boyd MD, Ellison NB. Social network sites: definition, history, and scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 2007; 13:210–230 [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Joinson AN. ‘Looking at’, ‘looking up’ or ‘keeping up with’ people? Motives and uses of facebook. Online Social Networks 2008; 1027–1036 [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Sledgianowski D, Kulviwat S. Using social network sites: the effects of playfulness, critical mass and trust in a hedonic context. Journal of Computer Information Systems 2009; 49:74–83 [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Kaplan AM, Haenlein M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Business Horizons 2010; 53:59–68 [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Kietzmann JH, Hermkens K, McCarthy IP, et al. . Social media? Get serious! Understanding the functional building blocks of social media. Business Horizons 2011; 54:241–251 [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Hughes DJ, Rowe M, Batey M, et al. . A tale of two sites: twitter vs. facebook and the personality predictors of social media usage. Computers in Human Behavior 2012; 28:561–569 [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Ellison NB, Boyd DM. (2013) Sociality through social network sites. In Dutton WH, ed. The oxford handbook of internet studies. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, pp. 151–172 [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Carr CT, Hayes RA. Social media: defining, developing, and divining. Atlantic Journal of Communication 2015; 23:46–65 [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Miller D, Costa E, Haynes N, et al. (2016) How the world changed social media. London, United Kingdom: UCL Press [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Leyrer-Jackson JM, Wilson AK. The associations between social-media use and academic performance among undergraduate students in biology. Journal of Biological Education 2018; 52:221–230 [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Kapoor KK, Tamilmani K, Rana NP, et al. . Advances in social media research: past, present and future. Information Systems Frontiers 2018; 20:531–558 [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Bishop M. (2019) Healthcare social media for consumer. In Edmunds M, Hass C, Holve E, eds. Consumer informatics and digital health: solutions for health and health care. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, pp. 61–86 [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. Himelboim I, Smith MA, Rainie L, et al. . Classifying twitter topic-networks using social network analysis. Social Media + Society 2017; 3:1–13 [ Google Scholar ]

- 48. Jin SV, Muqaddam A, Ryu E. Instafamous and social media influencer marketing. Marketing Intelligence and Planning 2019; 37:567–579 [ Google Scholar ]

- 49. Zhao S, Shchekoturov AV, Shchekoturova SD. Personal profile settings as cultural frames: facebook versus vkontakte. Journal of Creative Communications 2017; 12:171–184 [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (785.6 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

IMAGES

VIDEO