77 Frederick Douglass Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best frederick douglass topic ideas & essay examples, ✅ most interesting frederick douglass topics to write about, ❓ frederick douglass essay questions.

Many students find writing a Frederick Douglass essay a problematic task. If you’re one of them, then check this article to learn the essential do’s and don’ts of academic writing:

- Do structure your essay. Here’s the thing: when you arrange the key points of your paper in a logical order, it makes it easier for your readers to read the essay and get the message across. Eliminate unnecessary words and phrases: keep continually asking yourself whether you need a particular construction in the paper and if it clear.

- Do put your Frederick Douglass essay thesis statement in the intro. A thesis statement is a mandatory part of the paper introduction. Use it to reveal the central idea of your assignment. Think of what you’re going to write about: slavery, its effect of slaveholders, freedom, etc. Avoid placing a thesis at the beginning of the introductory paragraph.

- Do use citations. If you’re going to use a quote, provide examples from a book, always use references. Doing this would help your essay sound more convincing and also will help you avoid accusations of plagiarism. Make sure that you stick to the required citation style.

- Do use the present tense in your literature and rhetorical analysis. The secret is that present tense will make your paper more engaging.

- Do stick to Frederick Douglass essay prompt. If your paper has a prompt, make sure that you’ve covered all the aspects of it.

- Don’t use too complicated sentences. Using unnecessary complex sentences will only increase of grammar and1 style mistakes. Instead, make your writing simple and readable.

- Don’t overload your paper with facts and quotes. Some Frederick Douglass essay topics require more quotes than other papers. However, you should avoid turning your paper in one complete quote. Narrow the topic and use only the most relevant citations to prove your statements.

- Don’t use slang and informal language. You’re writing an essay, not a letter to your friend. So stick to the academic writing style and use appropriate language. Avoid using clichés.

- Don’t underestimate the final paper revision. Regardless of what Frederick Douglass essay titles you choose for your assignment, don’t let mistakes and typos spoil your writing. There are plenty of spelling and grammar checking tools. Use them to polish your paper. However, don’t underrate human manual proofread. Ask your friend or relative to revise the text.

If you’re looking for Frederick Douglass essay questions, you can explore some sample ideas to use in your paper:

- How do you think, what did Frederick Douglass dreamed about?

- Explore Douglass’s view of slavery. Illustrate it with quotes from the Narrative.

- What role did Douglass play for further liberation from slavery?

- Explain why self-education was so important for Douglass. Show the connection between knowledge and freedom. Why did slaveholders refuse to educate their slaves?

- What was the role of female slaves in Douglass works?

Check out IvyPanda’s Frederick Douglass essay samples to learn how to structure academic papers for college and university, find inspiration, and boost your creativity.

- The Importance of Literacy Essay (Critical Writing) Literacy is a skill that is never late to acquire because it is essential for education, employment, belonging to the community, and ability to help one’s children.

- Frederick Douglass Leadership Personality Traits Report (Assessment) The book was so humorous that he feared that he would be enslaved again for the weaknesses that he portrayed in the American lifestyle and how he was able to trick them with the attire […]

- The Challenges of Racism Influential for the Life of Frederick Douglass and Barack Obama However, Douglass became an influential anti-slavery and human rights activist because in the early childhood he learnt the power of education to fight inequality with the help of his literary and public speaking skills to […]

- Religion Role in Douglass Narrative Story The Christianity practiced by the black slaves is represented as the Christianity that is inexistence of purity, complete in peace in it, and also it serves as the full representation of the nature of Christ […]

- Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass The book, ‘Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass’ is both an indictment of slavery and a call to action for its abolition.

- Harriet Jacobs and Frederick Douglass Literature Comparison As a result, their narratives, in tone, in mood, in presentation of self, in degree and kind of analysis of the world around them, reflect these differences.

- Malcolm X and Frederick Douglass’ Comparison He was challenged in the area of writing and was incapacitated without the skill and ability to write letters to Mr. He was then to be imprisoned, and inside the four walls of the prison, […]

- African American Lit: “The Heroic Slave” by Frederick Douglass Freedom is not that simple, thus Frederick Douglass saw fit to write The Heroic Slave in which he portrays this vision for freedom; the idea of becoming a free man, and using the struggle he […]

- Christianity in Frederick Douglass Narrative Story This discussion is therefore inclusive of the role of Christianity which is represented in the narrative Frederick story in comparison of both representations by the slaveholders as well as the slaves themselves.

- Narrative of the Life of Fredrick Douglass – An American Slave Another evidence of beatings perpetrated on slaves is seen when Douglass is taken to the custody of Mr. The effect of this can be seen when Douglass was taken to Mr.

- Analysis of “Ethos in Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave” by Fredrick Douglass Another important point the readers are to draw their attention to when reading is the appearance of hope in the author’s heart.

- Frederick Douglas biography study This speech is considered to be the brightest words in regards to civil rights, slave freedom, and a kind of reborn of slaves and their families.

- Dr. King’s Work, and Frederick Douglass’ Efforts Douglass is righteous in his indignation and without caution blasts away at the evils responsible for the condition of his race, as he sees them. It is because of the presence of bondage in Douglass’ […]

- Rhetorical Analysis of Ethos in “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave” While making rhetorical analysis of Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, I would like to point out that his memoir is recognized to be one of greatest narratives of the nineteen century in the […]

- Autobiography & Slavery Life of Frederick Douglass This essay discusses the slavery life of Frederick Douglass as written in his autobiography, and it highlights how he resisted slavery, the nature of his rebellion, and the view he together with Brinkley had about […]

- Frederick Douglass on Recipe for Obedience In his pursuit of knowledge, Douglass taught himself to read and write, helped other enslaved people become literate, and escaped slavery to become the face of the abolitionist movement in the US.

- The “My Escape from Slavery” Essay by Frederick Douglass With imagery that allows the reader to experience his trials and worries, the story describes his experiences and hurdles on his way to his new “free life” in New York.

- Frederick Douglass: The Autobiography Analysis Serving as the pivoting point in Douglass’ perception of his situation, his fight with covey made him realize the necessity to fight back as the only possible response to the atrocities of slavery and the […]

- Relevance of Frederick Douglass’s Address to the Modern Events In the selection that is quite relevant to the current events and issues, the speaker exclaims that only blasting reproaches, biting ridicule, and sarcasm can awaken the consciousness of a nation and make people do […]

- Main Theme and Motifs of Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass Slavery is one of the most tragic episodes in the history of the world and the most striking manifestations of human discrimination.

- Frederick Douglass: The Positions of African Americans Due to the passion and hard work of this person, slavery was subsequently abolished in the whole territory of the United States.

- Frederick Douglass’s My Bondage and My Freedom Review He criticizes that in spite of the perceived knowledge he was getting as a slave, this very light in the form of knowledge “had penetrated the moral dungeon”.

- Frederick Douglass and His Fight for Slaves Rights Slaves used to be numb, their voices were not heard because of their illiteracy and inability to speak publicly, which can be seen in the second edition of the second edition of his work Narrative […]

- Frederick Douglass and Harriet Jacobs: Slave Narratives Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass is the story of the fight for civil fights and racial injustice. Incidents in the life of a slave girl by Harriet Jacobs is a true story of […]

- Frederick Douglass 1865 Speech Review Standing in front of the president, Douglass says: “for in fact, if he is not the slave of the individual master, he is the slave of society, and holds his liberty as a privilege, not […]

- The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass Frederick Douglass is the writer of the slavery origin, who managed to get an education and to tell the whole world about the life of slaves, about their suffering and abjection, which they have to […]

- Frederick Douglass’ Speech: Oratorical Analysis The following essay presents an oratorical analysis of Frederic Douglass’ speech on the abolition of slavery by providing a description, analyzing the audience, and evaluating the success of the presentation.

- Frederick Douglass on Moral Value of Individuals In conclusion, it is appropriate to note that a clear answer to the matters of moral and instrumental values of human beings.

- The Story of Mr. Frederick Douglass: Lesson Plan The focus of the lesson will be American History as the emphasis will be put on Mr. They will be required to record their feelings about different aspects of the story as it is told.

- Frederick Douglass as an Anti-Slavery Activist In “What to the slave is the fourth of July?” the orator drives the attention of his audience to a serious contradiction: Americans consider the Declaration of independence a document that proclaimed freedom, but this […]

- Slavery in “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass” The character traits of the slaveholders are brought out by the use of the word nigger and the emphasis on ignorance as a weapon against the empowerment of the blacks.

- Mary Prince and Frederick Douglass: Works Comparison The primary goal of compiling the stories was to invoke opposition and assist in the fight for the abolishment of slavery.

- Slavery in Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass In the fifth chapter, for instance, the author notes that he was moved to Baltimore, Maryland, something that played a critical role in transforming his life since he faced the realities of slavery.

- Frederick Douglass and His Incredible Life It is hard to ignore the fact that most of the historic events that took place in the USA up to the middle of the XX century were carried out by white men; slavery, a […]

- Frederick Douglass and Harriet Jacobs To enlighten the people about the dreadful facts, escapee slaves noted down their accounts of slavery on paper and availed the information for the public to read.

- The Role of Animality in Constructing Frederick Douglass’s Identity and the Issues of Liminality in “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave” by Frederick Douglass However, in his work Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Frederick Douglass represents the contradictory vision of the issue, supporting the idea that the white slave owners acted as animals in […]

- The Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave He realizes the importance of education and decides that he has to learn how to read and write at all costs.

- Slavery in America: “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass” The Author is also the persona in entire narration as he recounts his real experience in slavery right from childhood. In the narration, there are major and minor characters that the author has used to […]

- Slavery Effects on Enslaved People and Slave Owners Reflecting on the life of Douglass Frederick and written in prose form, the narrative defines the thoughts of the author on various aspects of slavery from the social, economic, security, and the need for appreciation […]

- Frederick Douglass’s poem Apparently, by doing it, Douglass strived to emphasize the hypocritical ways of Southern slave-owning Bible-thumpers, who used to be thoroughly comfortable with indulging in two mutually incompatible activities, at the same time treating Black slaves […]

- Alternative ending of the book about Frederick Douglass He expected people in the north to be poor and miserable and he regarded that poverty as “the necessary consequence of their being non-slaveholders”.

- The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass Douglass felt that the lords made rules and regulation with the need to oppress the Negros, he was of the view that the American Lords had developed the religion of Christianity and enforced it to […]

- Recapping the “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass” He reveals that the slave’s children were left at the care of aged women who were unable to provide labour, and that this was meant to break the strong affection of the child and the […]

- Testament Against Slavery: ”Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass” The opposition to his accounts soon spread to include slave abolitionists who felt that he should concentrate on the “facts of his story” and abstain from delving into the philosophy behind slavery.”Narrative of the Life […]

- Why slavery is wrong When Douglass heard this story, he got the idea of how whites manage to keep blacks in a state of ignorance so that they cannot come out of their captivity. In his book, Douglass reveals […]

- Frederick Douglass’ Life and Character He was aware of his disadvantaged situation as a slave but instead he chose not to bow to the pressure and fight back.

- The Frederick Douglass Historic Site The site is protected by Public Law and is meant to commemorate the life of Frederick Douglass. This site is a commemoration of the life of Frederick Douglass.

- What are Douglass’s views on Christianity?

- How Does Douglass Attain Literacy and What Does This Ability Do for Him?

- What Are the Elements of Traditional African Religion and Dialect in the Autobiography of Frederick Douglass?

- How Does Douglass’s Abolitionism Begin and Develop?

- What Are Douglass’s Strengths?

- How Does Douglass Evolve From a Boy and a Slave to a Fully-Realized Man and Human Being?

- What Are the Various Ways in Which Douglass Expresses the Horrors of Slavery?

- How Does Douglass Revisit the Mythology of Ben Franklin and the “Self-Made Man”?

- What Are the Tone and Style Douglass Employs in His Prose?

- How Does Douglass Connect Violence and Power in His Narrative?

- What Are Douglass’s Perceptions of the North?

- How Does Douglass Conceive Freedom? What Qualities or Characteristics Does It Seem to Have for Him?

- What “American” Values or Ethics Does Douglass Seem to Embrace or Reject?

- How Does Douglass Describe New Bedford, Massachusetts?

- What Thoughts Does Douglass Have About Religion and God?

- Why Is Education So Important to Douglass?

- What Role Do Women Play in Douglass’s Narrative?

- How Did Frederick Douglass Feel About Freedom?

- What Kind of Hero Is Douglass? Does His Heroism Come From His Physical or Mental State?

- How Did Frederick Douglass Help End Slavery?

- What Lessons Does Douglass’s Life Have for Readers Who Aren’t Slaves? What Can We Learn From His Story?

- How Did Frederick Douglass Inspire Others?

- What Was Frederick Douglass’s Main Message?

- How Did Frederick Douglass Describe Slavery?

- What Was Frederick Douglass’s Greatest Strength?

- How Many Slaves Did Frederick Douglass Help Free?

- What Impact Did Frederick Douglass Have On Slavery?

- Why Is the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass Important to History?

- What Struggles Did Frederick Douglass Have?

- Why Did Douglass Write His Narrative?

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, September 26). 77 Frederick Douglass Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/frederick-douglass-essay-examples/

"77 Frederick Douglass Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 26 Sept. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/frederick-douglass-essay-examples/.

IvyPanda . (2023) '77 Frederick Douglass Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 26 September.

IvyPanda . 2023. "77 Frederick Douglass Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/frederick-douglass-essay-examples/.

1. IvyPanda . "77 Frederick Douglass Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/frederick-douglass-essay-examples/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "77 Frederick Douglass Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/frederick-douglass-essay-examples/.

- Race Essay Ideas

- Slavery Ideas

- US History Topics

- Malcolm X Questions

- Racial Profiling Essay Topics

- Racism Paper Topics

- Barack Obama Topics

- Democracy Titles

- Abraham Lincoln Topics

- Freedom Topics

- African American History Essay Ideas

- Booker T. Washington Paper Topics

- Civil Rights Movement Questions

- W.E.B. Du Bois Research Ideas

- Benjamin Franklin Titles

Frederick Douglass’s Path to Freedom

Written by: Bill of Rights Institute

By the end of this section, you will:.

- Explain how and why various reform movements developed and expanded from 1800 to 1848

- Explain the continuities and changes in the experience of African Americans from 1800 to 1848

Suggested Sequencing

This Narrative explores the idea of slavery and abolitionism and can be used along with the Nat Turner’s Rebellion and William Lloyd Garrison’s War Against Slavery Narratives, as well as the David Walker, “An Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World,” 1829 and Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass , 1845 Primary Sources.

Frederick Douglass grew up enslaved in Maryland, where his individual human dignity was stripped away by a system of owning other human beings. He barely knew his mother, who had had to walk several miles from another plantation to visit him when he was a little boy. He also did not know who his father was, though he guessed it was one of the white men on the plantation. He did not even know his birthday.

When Douglass was seven years old, his grandmother carried him to another plantation where he witnessed the horrors of slavery. He watched as his aunt was stripped to the waist and brutally whipped, causing blood to run down her back. “It was the first of a long series of such outrages . . . It struck me with awful force.” Douglass never became reconciled to such an unjust system.

This photograph of an enslaved person’s scarred back, taken in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in 1863, demonstrates the brutality of slavery. Frederick Douglass witnessed such a whipping as a seven-year-old boy.

Douglass’s owner sent the boy to live in Baltimore, Maryland, with Hugh and Sophia Auld. Sophia taught Douglass to read the Bible, which outraged her husband. Hugh argued it would ruin Douglass for slavery because he would reject his servitude; he forbade the lessons. The brilliant young boy immediately recognized there was something unnatural about slavery. He caught on to its immorality and the importance of reading to recover his humanity. “From that moment, I understood the pathway from slavery to freedom . . . The argument which he so warmly urged, against my learning to read, only served to inspire me with a desire and determination to learn,” Douglass later wrote.

The intrepid Douglass continued to learn to read. He surreptitiously read from the spelling copybook belonging to the Aulds’ son and from their Bible. He bribed and tricked white boys in the neighborhood to give him reading instruction. He acquired a copy of the Columbian Orator , which had speeches that taught him language and rhetoric. More importantly, the book contained lessons about the principles of liberty and emancipation from slavery. From newspapers, Douglass learned about Nat Turner’s slave rebellion and statesmen such as John Quincy Adams who were fighting the gag rule and the injustices of slavery in the halls of Congress.

When his masters died, ownership of Douglass was juggled until the brutal Thomas Auld owned him and demanded that the enslaved fifteen-year-old boy be sent to work as a field hand on his plantation. Douglass had converted to Christianity and tried to start a Sunday school for other slaves but was thwarted. Because he had a rebellious streak, Auld sent him to a “slave breaker” named Edward Covey to crush his spirit with the lash.

Within a week, Covey had whipped Douglass savagely. “Mr. Covey gave me a very severe whipping, cutting my back, causing the blood to run, and raising ridges on my flesh as large as my little finger,” Douglass later reported. Covey beat Douglass at least once a week. The dehumanizing routine of violence stripped Douglass of his human dignity. According to Douglass, “Mr. Covey succeeded in breaking me. I was broken in body, soul, and spirit. My natural elasticity was crushed, my intellect languished, the disposition to read departed, the cheerful spark that lingered about my eye died; the dark night of slavery closed in on me; and behold a man transformed into a brute!”

Douglass fell into a stupor and could not shake his malaise. One day, he suffered heatstroke and had to stop working because he was weak and dizzy. Covey discovered Douglass lying on the ground and thought him lazy. Covey gave the enslaved Douglass a “savage kick in the side, and told me to get up.” Douglass tried several times to rise and was beaten harder with every failure. A blow to his head with a hickory stick made “a large wound, and the blood ran freely.” He mustered the courage to defy Covey and walk seven miles to his master’s house to relate what Covey had done. The unsympathetic Auld ignored his pleas and sent him back to Covey. Never had Douglass felt more powerless and less like a man. He hid out for a day for relief but finally returned.

The next day changed Douglass’s life forever. Covey sought to tackle Douglass and beat him, but Douglass actually fought back. “At this moment – from whence came the spirit I don’t know – I resolved to fight; and, suiting my action to my resolution, I seized Covey by the throat.” Covey desperately solicited the help of another white man, whom Douglass kicked in the ribs and knocked down. Douglass wrote that he told Covey “Come what might; that he had used me like a brute for six months, and that I was determined to be used so no longer.”

Covey then tried to order another slave to intervene, but the man refused and left the two to finish their battle. Douglass thought the fight lasted for nearly two hours until finally it ended in a draw. As they stared at each other, panting frantically, Douglass noted with satisfaction that he had been neither bloodied nor whipped, but that he had bloodied Covey. For the next six months, Covey did not lay a finger on Douglass again. Douglass even ignored Covey’s threats and warned the slave breaker that he would get a worse beating than the first if he tried.

For Douglass, it was the turning point in his life. He had recovered his manhood and his dignity. “It rekindled the few expiring embers of freedom,” Douglass explained, “and revived within me a sense of my manhood. It recalled the departed self-confidence, and inspired me again with a determination to be free.” Douglass exercised his duty to resist injustice and secure his natural rights to restore his spirit and humanity. Having destroyed any hold that slavery might have over his soul, he was now a slave in name only and would no longer live in fear or submission. His soul longed for liberty. “It was a glorious resurrection, from the tomb of slavery, to the heaven of freedom. My long-crushed spirit rose, cowardice departed, bold defiance took its place; and I now resolved that, however long I might remain a slave in form, the day had passed forever when I could be a slave in fact.”

Douglass escaped to the North and freedom through the Underground Railroad a few years later. He married and started earning his own money, keeping the fruits of his labor. His work and marriage contributed further to his recovering his human dignity and becoming a man. “I was now my own master. It was a happy moment, the rapture of which can be understood only by those who have been slaves. It was the first work, the reward of which was to be entirely my own.” Douglass was now a man with a strong sense of self-worth who devoted himself to ensuring equal rights for all Americans through the abolitionist and women’s suffrage movements.

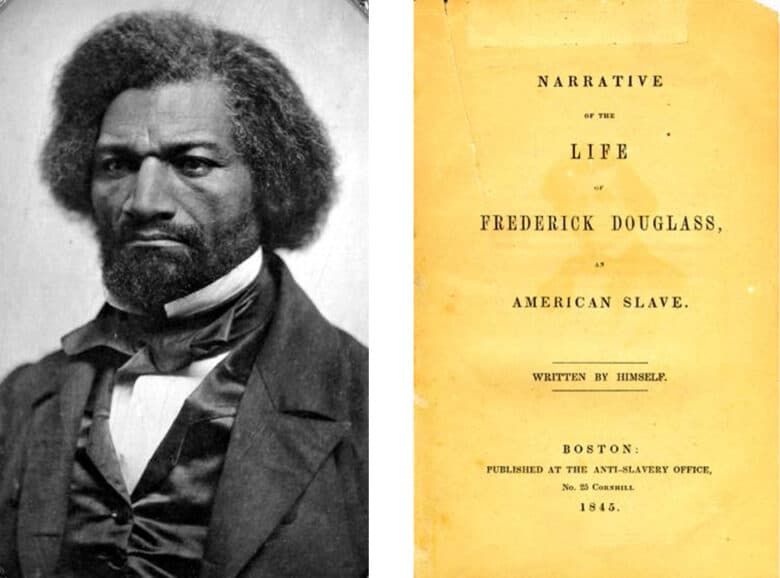

(a) This 1856 ambrotype of Frederick Douglass demonstrates an early type of photograph developed on glass. Douglass was an escaped slave who became instrumental in the abolitionist movement. (b) His story, told in Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, Written by Himself , followed a long line of similar narratives that demonstrated the brutality of slavery, for northerners unfamiliar with the institution.

Review Questions

1. What text was instrumental in teaching Frederick Douglass how to read and learning the principles of liberty as a young man?

- The Federalist

- The Columbian Orator

- The Liberator

- Common Sense

2. Which of the following best describes Frederick Douglass’s childhood?

- He was raised by his mother on a tobacco plantation and knew few of his other relatives.

- He was raised by his parents on a small farm, where he worked side by side with the family of the farm’s owner.

- He was raised by his master and mistress on a cotton plantation, where he was granted more privileges than an enslaved person typically received.

- He was raised by his grandmother and never knew the identity of his father.

3. Where was Frederick Douglass born and raised?

- Massachusetts

- North Carolina

4. How did Douglass achieve his freedom?

- He worked odd jobs, earned money, and bought his freedom.

- His freedom was purchased for him by abolitionists.

- He escaped to the North on the Underground Railroad.

- The state of Maryland abolished slavery.

5. Frederick Douglass’s life was most changed by

- his beatings by Edward Covey

- his learning to read and understand the concept of freedom

- the teachings of his grandmother

- lessons learned from the Bible

6. What did Frederick Douglass’s transformative fight with Edward Covey teach him?

- Slaves could not fight back against slavery.

- Running away would be severely punished.

- Slaves could never win their freedom.

- Resisting slavery could help him recover his worth as a human being.

Free Response Questions

- Using Frederick Douglass as an example, explain how an enslaved person was dehumanized by the institution of slavery.

- Explain how Frederick Douglass recovered his humanity and sense of dignity while a slave and later after he escaped to freedom.

AP Practice Questions

“I was glad to learn, in your story, how early the most neglected of God’s children waken to a sense of their rights, and of the injustice done them. Experience is a keen teacher; and long before you had mastered your A B C, or knew where the ‘white sails’ of the Chesapeake were bound, you began, I see, to gauge the wretchedness of the slave, not by his hunger and want, not by his lashes and toil, but by the cruel and blighting death which gathers over his soul. In connection with this, there is one circumstance which makes your recollections peculiarly valuable, and renders your early insight the more remarkable. You come from that part of the country where we are told slavery appears with its fairest features. Let us hear, then, what it is at its best estate – gaze on its bright side, if it has one; and then imagination may task her powers to add dark lines to the picture, as she travels southward to that (for the colored man) Valley of the Shadow of Death, where the Mississippi sweeps along.”

Letter from Wendell Phillips, Esq., Boston, April 22, 1845, included as an introduction to Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, Written by Himself

1. The author of the excerpt most likely would support what social reform in the antebellum era?

- Women’s rights

- A broader access to public education

2. According to this author, practices of slaveholders in which part of the United States were most brutal?

- the Northeast coast

- the deep South

- the Chesapeake region

- the mid-Atlantic

Primary Sources

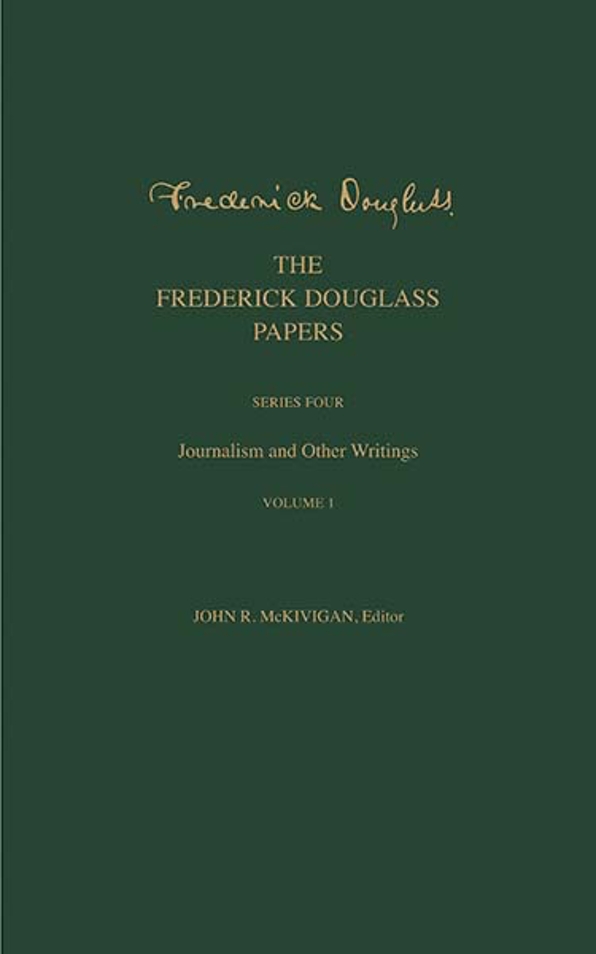

Douglass, Frederick. Life and Times of Frederick Douglass . New York: Library of America, 1994. (Originally published, 1892).

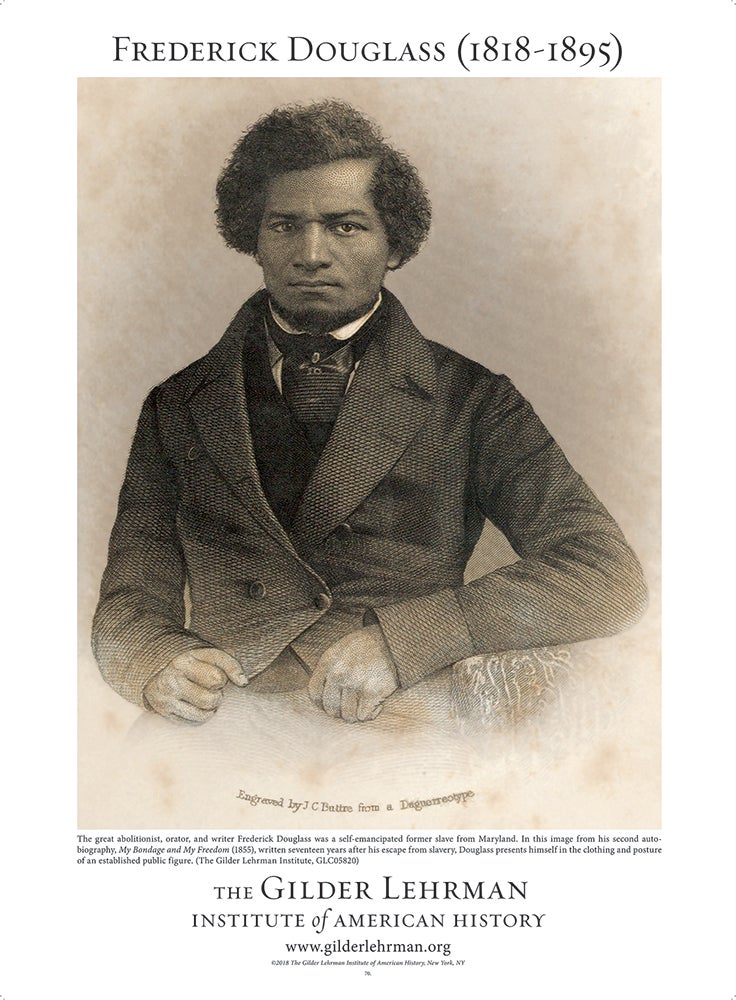

Douglass, Frederick. My Bondage and My Freedom . New York: Penguin, 1993. (Originally published, 1855).

Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave: Written by Himself . New York: Penguin, 1986 (Originally published, 1845).

Suggested Resources

Blight, David W. Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom . New York: Simon and Schuster, 2018.

Huggins, Nathan Irvin. Slave and Citizen: The Life of Frederick Douglass . Boston: Little Brown, 1980.

Levine, Robert S. The Lives of Frederick Douglass. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016.

McFeely, William. Frederick Douglass . New York: Norton, 1991.

Meyers, Peter C. Frederick Douglass: Race and the Rebirth of America Liberalism . Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2008.

Stauffer, John, Zoe Trodd, and Celeste-Marie Bernier. Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Century’s Most Photographed American . New York: Liveright, 2015.

Related Content

Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness

In our resource history is presented through a series of narratives, primary sources, and point-counterpoint debates that invites students to participate in the ongoing conversation about the American experiment.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Frederick Douglass

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 8, 2024 | Original: October 27, 2009

Frederick Douglass was a formerly enslaved man who became a prominent activist, author and public speaker. He became a leader in the abolitionist movement , which sought to end the practice of slavery, before and during the Civil War . After that conflict and the Emancipation Proclamation of 1862, he continued to push for equality and human rights until his death in 1895.

Douglass’ 1845 autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave , described his time as an enslaved worker in Maryland . It was one of three autobiographies he penned, along with dozens of noteworthy speeches, despite receiving minimal formal education.

An advocate for women’s rights, and specifically the right of women to vote , Douglass’ legacy as an author and leader lives on. His work served as an inspiration to the civil rights movement of the 1960s and beyond.

Who Was Frederick Douglass?

Frederick Douglass was born into slavery in or around 1818 in Talbot County, Maryland. Douglass himself was never sure of his exact birth date.

His mother was an enslaved Black women and his father was white and of European descent. He was actually born Frederick Bailey (his mother’s name), and took the name Douglass only after he escaped. His full name at birth was “Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey.”

After he was separated from his mother as an infant, Douglass lived for a time with his maternal grandmother, Betty Bailey. However, at the age of six, he was moved away from her to live and work on the Wye House plantation in Maryland.

From there, Douglass was “given” to Lucretia Auld, whose husband, Thomas, sent him to work with his brother Hugh in Baltimore. Douglass credits Hugh’s wife Sophia with first teaching him the alphabet. With that foundation, Douglass then taught himself to read and write. By the time he was hired out to work under William Freeland, he was teaching other enslaved people to read using the Bible .

As word spread of his efforts to educate fellow enslaved people, Thomas Auld took him back and transferred him to Edward Covey, a farmer who was known for his brutal treatment of the enslaved people in his charge. Roughly 16 at this time, Douglass was regularly whipped by Covey.

Frederick Douglass Escapes from Slavery

After several failed attempts at escape, Douglass finally left Covey’s farm in 1838, first boarding a train to Havre de Grace, Maryland. From there he traveled through Delaware , another slave state, before arriving in New York and the safe house of abolitionist David Ruggles.

Once settled in New York, he sent for Anna Murray, a free Black woman from Baltimore he met while in captivity with the Aulds. She joined him, and the two were married in September 1838. They had five children together.

From Slavery to Abolitionist Leader

After their marriage, the young couple moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts , where they met Nathan and Mary Johnson, a married couple who were born “free persons of color.” It was the Johnsons who inspired the couple to take the surname Douglass, after the character in the Sir Walter Scott poem, “The Lady of the Lake.”

In New Bedford, Douglass began attending meetings of the abolitionist movement . During these meetings, he was exposed to the writings of abolitionist and journalist William Lloyd Garrison.

The two men eventually met when both were asked to speak at an abolitionist meeting, during which Douglass shared his story of slavery and escape. It was Garrison who encouraged Douglass to become a speaker and leader in the abolitionist movement.

By 1843, Douglass had become part of the American Anti-Slavery Society’s “Hundred Conventions” project, a six-month tour through the United States. Douglass was physically assaulted several times during the tour by those opposed to the abolitionist movement.

In one particularly brutal attack, in Pendleton, Indiana , Douglass’ hand was broken. The injuries never fully healed, and he never regained full use of his hand.

In 1858, radical abolitionist John Brown stayed with Frederick Douglass in Rochester, New York, as he planned his raid on the U.S. military arsenal at Harper’s Ferry , part of his attempt to establish a stronghold of formerly enslaved people in the mountains of Maryland and Virginia. Brown was caught and hanged for masterminding the attack, offering the following prophetic words as his final statement: “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.”

'Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass'

Two years later, Douglass published the first and most famous of his autobiographies, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave . (He also authored My Bondage and My Freedom and Life and Times of Frederick Douglass).

In it Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass , he wrote: “From my earliest recollection, I date the entertainment of a deep conviction that slavery would not always be able to hold me within its foul embrace; and in the darkest hours of my career in slavery, this living word of faith and spirit of hope departed not from me, but remained like ministering angels to cheer me through the gloom.”

He also noted, “Thus is slavery the enemy of both the slave and the slaveholder.”

Frederick Douglass in Ireland and Great Britain

Later that same year, Douglass would travel to Ireland and Great Britain. At the time, the former country was just entering the early stages of the Irish Potato Famine , or the Great Hunger.

While overseas, he was impressed by the relative freedom he had as a man of color, compared to what he had experienced in the United States. During his time in Ireland, he met the Irish nationalist Daniel O’Connell , who became an inspiration for his later work.

In England, Douglass also delivered what would later be viewed as one of his most famous speeches, the so-called “London Reception Speech.”

In the speech, he said, “What is to be thought of a nation boasting of its liberty, boasting of its humanity, boasting of its Christianity , boasting of its love of justice and purity, and yet having within its own borders three millions of persons denied by law the right of marriage?… I need not lift up the veil by giving you any experience of my own. Every one that can put two ideas together, must see the most fearful results from such a state of things…”

Frederick Douglass’ Abolitionist Paper

When he returned to the United States in 1847, Douglass began publishing his own abolitionist newsletter, the North Star . He also became involved in the movement for women’s rights .

He was the only African American to attend the Seneca Falls Convention , a gathering of women’s rights activists in New York, in 1848.

He spoke forcefully during the meeting and said, “In this denial of the right to participate in government, not merely the degradation of woman and the perpetuation of a great injustice happens, but the maiming and repudiation of one-half of the moral and intellectual power of the government of the world.”

He later included coverage of women’s rights issues in the pages of the North Star . The newsletter’s name was changed to Frederick Douglass’ Paper in 1851, and was published until 1860, just before the start of the Civil War .

Frederick Douglass Quotes

In 1852, he delivered another of his more famous speeches, one that later came to be called “What to a slave is the 4th of July?”

In one section of the speech, Douglass noted, “What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy—a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages.”

For the 24th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation , in 1886, Douglass delivered a rousing address in Washington, D.C., during which he said, “where justice is denied, where poverty is enforced, where ignorance prevails, and where any one class is made to feel that society is an organized conspiracy to oppress, rob and degrade them, neither persons nor property will be safe.”

Frederick Douglass During the Civil War

During the brutal conflict that divided the still-young United States, Douglass continued to speak and worked tirelessly for the end of slavery and the right of newly freed Black Americans to vote.

Although he supported President Abraham Lincoln in the early years of the Civil War, Douglass fell into disagreement with the politician after the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, which effectively ended the practice of slavery. Douglass was disappointed that Lincoln didn’t use the proclamation to grant formerly enslaved people the right to vote, particularly after they had fought bravely alongside soldiers for the Union army.

It is said, though, that Douglass and Lincoln later reconciled and, following Lincoln’s assassination in 1865, and the passage of the 13th amendment , 14th amendment , and 15th amendment to the U.S. Constitution (which, respectively, outlawed slavery, granted formerly enslaved people citizenship and equal protection under the law, and protected all citizens from racial discrimination in voting), Douglass was asked to speak at the dedication of the Emancipation Memorial in Washington, D.C.’s Lincoln Park in 1876.

Historians, in fact, suggest that Lincoln’s widow, Mary Todd Lincoln , bequeathed the late-president’s favorite walking stick to Douglass after that speech.

In the post-war Reconstruction era, Douglass served in many official positions in government, including as an ambassador to the Dominican Republic, thereby becoming the first Black man to hold high office. He also continued speaking and advocating for African American and women’s rights.

In the 1868 presidential election, he supported the candidacy of former Union general Ulysses S. Grant , who promised to take a hard line against white supremacist-led insurgencies in the post-war South. Grant notably also oversaw passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1871 , which was designed to suppress the growing Ku Klux Klan movement.

Frederick Douglass: Later Life and Death

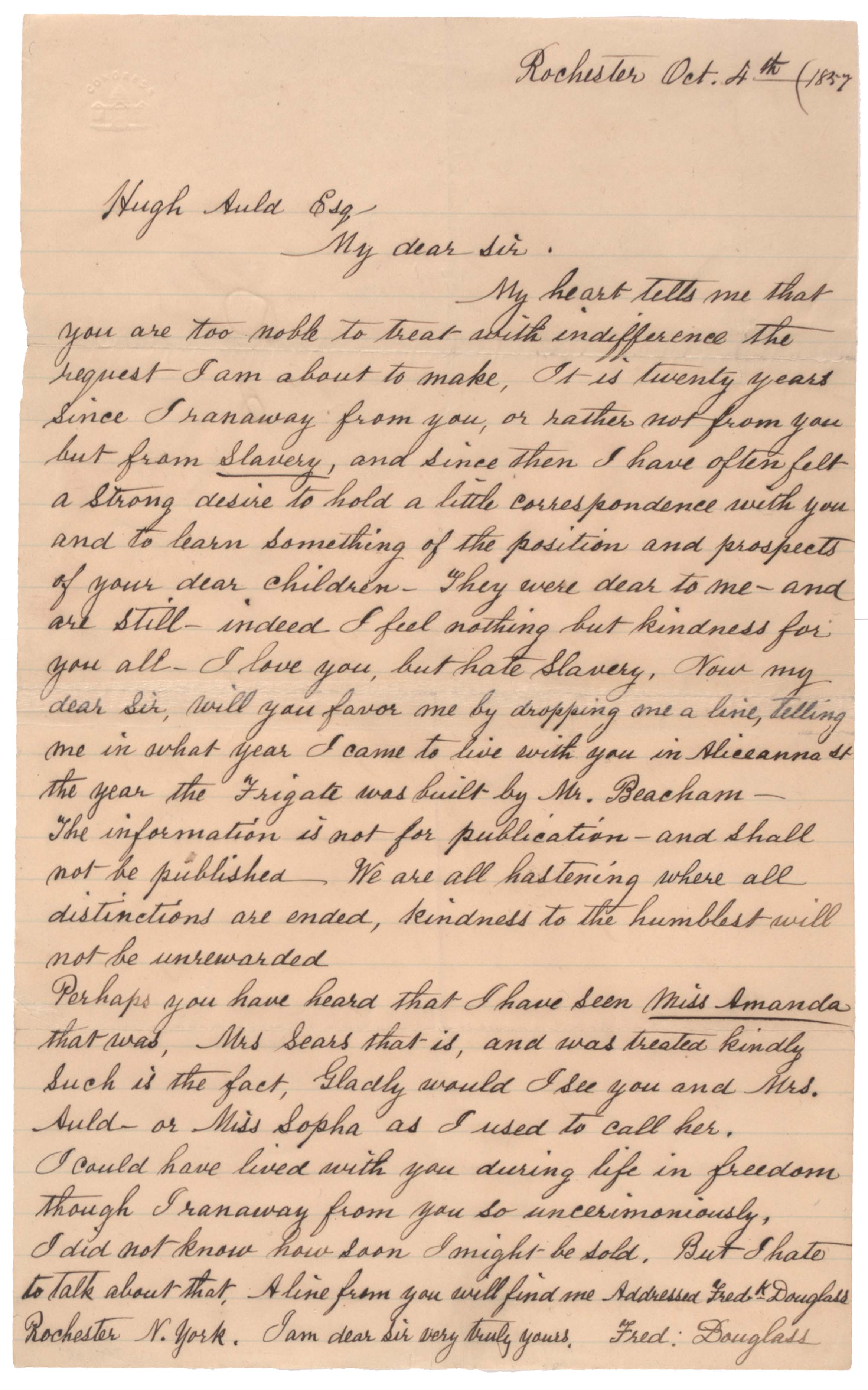

In 1877, Douglass met with Thomas Auld , the man who once “owned” him, and the two reportedly reconciled.

Douglass’ wife Anna died in 1882, and he married white activist Helen Pitts in 1884.

In 1888, he became the first African American to receive a vote for President of the United States, during the Republican National Convention. Ultimately, though, Benjamin Harrison received the party nomination.

Douglass remained an active speaker, writer and activist until his death in 1895. He died after suffering a heart attack at home after arriving back from a meeting of the National Council of Women , a women’s rights group still in its infancy at the time, in Washington, D.C.

His life’s work still serves as an inspiration to those who seek equality and a more just society.

HISTORY Vault: Black History

Watch acclaimed Black History documentaries on HISTORY Vault.

Frederick Douglas, PBS.org . Frederick Douglas, National Parks Service, nps.gov . Frederick Douglas, 1818-1895, Documenting the South, University of North Carolina , docsouth.unc.edu . Frederick Douglass Quotes, brainyquote.com . “Reception Speech. At Finsbury Chapel, Moorfields, England, May 12, 1846.” USF.edu . “What to the slave is the 4th of July?” TeachingAmericanHistory.org . Graham, D.A. (2017). “Donald Trump’s Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass.” The Atlantic .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

3.4 Annotated Sample Reading: from Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass by Frederick Douglass

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Read in several genres to understand how conventions are shaped by purpose, language, culture, and expectation.

- Use reading for inquiry, learning, critical thinking, and communicating in varying rhetorical and cultural contexts.

- Read a diverse range of texts, attending to relationships among ideas, patterns of organization, and interplay between verbal and nonverbal elements.

Introduction

Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) was born into slavery in Maryland. He never knew his father, barely knew his mother, and was separated from his grandmother at a young age. As a boy, Douglass understood there to be a connection between literacy and freedom. In the excerpt from his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave , that follows, you will learn about how Douglass learned to read. By age 12, he was reading texts about the natural rights of human beings. At age 15, he began educating other enslaved people. When Douglass was 20, he met Anna Murray, whom he would later marry. Murray helped Douglass plot his escape from slavery. Dressed as a sailor, Douglass bought a train ticket northward. Within 24 hours, he arrived in New York City and declared himself free. Douglass went on to work as an activist in the abolitionist movement as well as the women’s suffrage movement.

In the portion of the text included here, Douglass chooses to represent the dialogue of Mr. Auld, an enslaver who by the laws of the time owns Douglass. Douglass describes this moment with detail and accuracy, including Mr. Auld’s use of a racial slur. In an interview with the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), Harvard professor Randall Kennedy (b. 1954), who has traced the historical evolution of the word, notes that one of its first uses, recorded in 1619, appears to have been descriptive rather than derogatory. However, by the mid-1800s, White people had appropriated the term and begun using it with its current negative connotation. In response, over time, Black people have reclaimed the word (or variations of it) for different purposes, including mirroring racism, creating irony, and reclaiming community and personal power—using the word for a contrasting purpose to the way others use it. Despite this evolution, Professor Kennedy explains that the use of the word should be accompanied by a deep understanding of one’s audience and by being clear about the intention. However, even when intention is very clear and malice is not intended, harm can, and likely will, occur. Thus, Professor Kennedy cautions that all people should understand the history of the word, be aware of its potential negative effect on an audience, and therefore use it sparingly, or preferably not at all.

In the case of Mr. Auld and Douglass, Douglass gives an account of Auld’s exact language in order to hold a mirror to the racism of Mr. Auld—and the reading audience of his memoir—and to emphasize the theme that literacy (or education) is one way to combat racism.

Living by Their Own Words

Literacy from unexpected sources.

annotated text From the title and from Douglass’s use of pronoun I, you know this work is autobiographical and therefore written from the first-person point of view. end annotated text

public domain text [excerpt begins with first full paragraph on page 33 and ends on page 34 where the paragraph ends] end public domain text

public domain text Very soon after I went to live with Mr. and Mrs. Auld, she very kindly commenced to teach me the A, B, C. After I had learned this, she assisted me in learning to spell words of three or four letters. Just at this point of my progress, Mr. Auld found out what was going on, and at once forbade Mrs. Auld to instruct me further, telling her, among other things, that it was unlawful, as well as unsafe, to teach a slave to read. end public domain text

annotated text Douglass describes the background situation and the culture of the time, which he will defy in his quest for literacy. The word choice in his narration of events indicates that he is writing for an educated audience. end annotated text

public domain text To use his own words, further, he said, “If you give a nigger an inch, he will take an ell. A nigger should know nothing but to obey his master—to do as he is told to do. Learning would spoil the best nigger in the world. Now,” said he, “if you teach that nigger (speaking of myself) how to read, there would be no keeping him. It would forever unfit him to be a slave. He would at once become unmanageable, and of no value to his master. As to himself, it could do him no good, but a great deal of harm. It would make him discontented and unhappy.” end public domain text

annotated text In sharing this part of the narrative, Douglass underscores the importance of literacy. He provides a description of Mr. Auld, a slaveholder, who seeks to impose illiteracy as a means to oppress others. In this description of Mr. Auld’s reaction, Douglass shows that slaveholders feared the power that enslaved people would have if they could read and write. end annotated text

annotated text Douglass provides the details of Auld’s dialogue not only because it is a convention of narrative genre but also because it demonstrates the purpose and motivation for his forthcoming pursuit of literacy. We have chosen to maintain the authenticity of the original text by using the language that Douglass offers to quote Mr. Auld’s dialogue because it both provides context for the rhetorical situation and underscores the value of the attainment of literacy for Douglass. However, contemporary audiences must understand that this language should be uttered only under very narrow circumstances in any current rhetorical situation. In general, it is best to avoid its use. end annotated text

public domain text These words sank deep into my heart, stirred up sentiments within that lay slumbering, and called into existence an entirely new train of thought. It was a new and special revelation, explaining dark and mysterious things, with which my youthful understanding had struggled, but struggled in vain. I now understood what had been to me a most perplexing difficulty—to wit, the white man’s power to enslave the black man. It was a grand achievement, and I prized it highly. From that moment, I understood the pathway from slavery to freedom. It was just what I wanted, and I got it at a time when I the least expected it. Whilst I was saddened by the thought of losing the aid of my kind mistress, I was gladdened by the invaluable instruction which, by the merest accident, I had gained from my master. end public domain text

annotated text In this reflection, Douglass has a definitive and transformative moment with reading and writing. The moment that sparked a desire for literacy is a common feature in literacy narratives, particularly those of enslaved people. In that moment, he understood the value of literacy and its life-changing possibilities; that transformative moment is a central part of the arc of this literacy narrative. end annotated text

public domain text Though conscious of the difficulty of learning without a teacher, I set out with high hope, and a fixed purpose, at whatever cost of trouble, to learn how to read. The very decided manner with which he spoke, and strove to impress his wife with the evil consequences of giving me instruction, served to convince me that he was deeply sensible of the truths he was uttering. It gave me the best assurance that I might rely with the utmost confidence on the results which, he said, would flow from teaching me to read. What he most dreaded, that I most desired. What he most loved, that I most hated. That which to him was a great evil, to be carefully shunned, was to me a great good, to be diligently sought; and the argument which he so warmly urged, against my learning to read, only served to inspire me with a desire and determination to learn. In learning to read, I owe almost as much to the bitter opposition of my master, as to the kindly aid of my mistress. I acknowledge the benefit of both. end public domain text

annotated text Douglass articulates that this moment changed his relationship to literacy and ignited a purposeful engagement with language and learning that would last throughout his long life. The rhythm, sentence structure, and poetic phrasing in this reflection provide further evidence that Douglass, over the course of his life, actively pursued and mastered language after having this experience with Mr. Auld. end annotated text

public domain text [excerpt continues with the beginning of Chapter 7 on page 36 and ends with the end of the paragraph at the top of page 39] end public domain text

public domain text [In Chapter 7, the narrative continues] I lived in Master Hugh’s family about seven years. During this time, I succeeded in learning to read and write. In accomplishing this, I was compelled to resort to various stratagems. I had no regular teacher. My mistress, who had kindly commenced to instruct me, had, in compliance with the advice and direction of her husband, not only ceased to instruct, but had set her face against my being instructed by any one else. It is due, however, to my mistress to say of her, that she did not adopt this course of treatment immediately. She at first lacked the depravity indispensable to shutting me up in mental darkness. It was at least necessary for her to have some training in the exercise of irresponsible power, to make her equal to the task of treating me as though I were a brute. end public domain text

public domain text My mistress was, as I have said, a kind and tender-hearted woman; and in the simplicity of her soul she commenced, when I first went to live with her, to treat me as she supposed one human being ought to treat another. In entering upon the duties of a slaveholder, she did not seem to perceive that I sustained to her the relation of a mere chattel, and that for her to treat me as a human being was not only wrong, but dangerously so. Slavery proved as injurious to her as it did to me. When I went there, she was a pious, warm, and tender-hearted woman. There was no sorrow or suffering for which she had not a tear. She had bread for the hungry, clothes for the naked, and comfort for every mourner that came within her reach. Slavery soon proved its ability to divest her of these heavenly qualities. Under its influence, the tender heart became stone, and the lamblike disposition gave way to one of tiger-like fierceness. The first step in her downward course was in her ceasing to instruct me. She now commenced to practise her husband’s precepts. She finally became even more violent in her opposition than her husband himself. end public domain text

annotated text Douglass describes in detail a person in his life and his relationship to her. He uses specific diction to describe her kindness and to help readers get to know her—a “tear” for the “suffering”; “bread for the hungry, clothes for the naked, and comfort for every mourner.” end annotated text

public domain text She was not satisfied with simply doing as well as he had commanded; she seemed anxious to do better. Nothing seemed to make her more angry than to see me with a newspaper. She seemed to think that here lay the danger. I have had her rush at me with a face made all up of fury, and snatch from me a newspaper, in a manner that fully revealed her apprehension. She was an apt woman; and a little experience soon demonstrated, to her satisfaction, that education and slavery were incompatible with each other. end public domain text

annotated text The fact that Douglass can understand the harm caused by the institution of slavery to slaveholders as well as to enslaved people shows a level of sophistication in thought, identifies the complexity and detriment of this historical period, and demonstrates an acute awareness of the rhetorical situation, especially for his audience for this text. The way that he articulates compassion for the slaveholders, despite their ill treatment of him, would create empathy in his readers and possibly provide a revelation for his audience. end annotated text

public domain text From this time I was most narrowly watched. If I was in a separate room any considerable length of time, I was sure to be suspected of having a book, and was at once called to give an account of myself. All this, however, was too late. The first step had been taken. Mistress, in teaching me the alphabet, had given me the inch , and no precaution could prevent me from taking the ell . end public domain text

annotated text Once again, Douglass underscores the value that literacy has for transforming the lived experiences of enslaved people. The reference to the inch and the ell circles back to Mr. Auld’s warnings and recalls the impact of that moment on his life. end annotated text

public domain text The plan which I adopted, and the one by which I was most successful, was that of making friends of all the little white boys whom I met in the street. As many of these as I could, I converted into teachers. With their kindly aid, obtained at different times and in different places, I finally succeeded in learning to read. When I was sent of errands, I always took my book with me, and by going one part of my errand quickly, I found time to get a lesson before my return. I used also to carry bread with me, enough of which was always in the house, and to which I was always welcome; for I was much better off in this regard than many of the poor white children in our neighborhood. This bread I used to bestow upon the hungry little urchins, who, in return, would give me that more valuable bread of knowledge. I am strongly tempted to give the names of two or three of those little boys, as a testimonial of the gratitude and affection I bear them; but prudence forbids;—not that it would injure me, but it might embarrass them; for it is almost an unpardonable offence to teach slaves to read in this Christian country. end public domain text

annotated text Douglass comments on the culture of the time, which still permitted slavery; he is sensitive to the fact that these boys might be embarrassed by their participation in unacceptable, though humanitarian, behavior. His audience will also recognize the irony in his tone when he writes that it is “an unpardonable offense to teach slaves . . . in this Christian country.” Such behavior is surely “unchristian.” end annotated text

public domain text It is enough to say of the dear little fellows, that they lived on Philpot Street, very near Durgin and Bailey’s ship-yard. I used to talk this matter of slavery over with them. I would sometimes say to them, I wished I could be as free as they would be when they got to be men. “You will be free as soon as you are twenty-one, but I am a slave for life ! Have not I as good a right to be free as you have?” These words used to trouble them; they would express for me the liveliest sympathy, and console me with the hope that something would occur by which I might be free. end public domain text

annotated text Douglass pursues and attains literacy not only for his own benefit; his knowledge also allows him to begin to instruct, as well as advocate for, those around him. Douglass’s use of language and his understanding of the rhetorical situation give the audience evidence of the power of literacy for all people, round out the arc of his narrative, and provide a resolution. end annotated text

Discussion Questions

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Authors: Michelle Bachelor Robinson, Maria Jerskey, featuring Toby Fulwiler

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Writing Guide with Handbook

- Publication date: Dec 21, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/3-4-annotated-sample-reading-from-narrative-of-the-life-of-frederick-douglass-by-frederick-douglass

© Dec 19, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

The Annotated

Frederick douglass, introduction and annotations by david w. blight, in 1866, the famous abolitionist laid out his vision for radically reshaping america in the pages of the atlantic ..

In his third autobiography, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass , while reflecting on the end of the Civil War, Douglass admitted that “a strange and, perhaps, perverse feeling came over me.” Great joy over the ending of slavery, he wrote, was at times “tinged with a feeling of sadness. I felt I had reached the end of the noblest and best part of my life; my school was broken up, my church disbanded, and the beloved congregation dispersed, never to come together again.” In recalling the postwar years, Douglass drew from a scene in a Shakespearean tragedy to express his memory of that moment: “ ‘Othello’s occupation was gone.’ ” In Othello, Douglass perceived a character, the former high-ranking general and “moor of Venice,” who had lost authority and professional purpose. Douglass harbored a special affinity for this most famous Black character in Western literature, whose mental collapse and horrible end lingered as a warning in a famous speech: “O, now, for ever / Farewell the tranquil mind! Farewell content!”

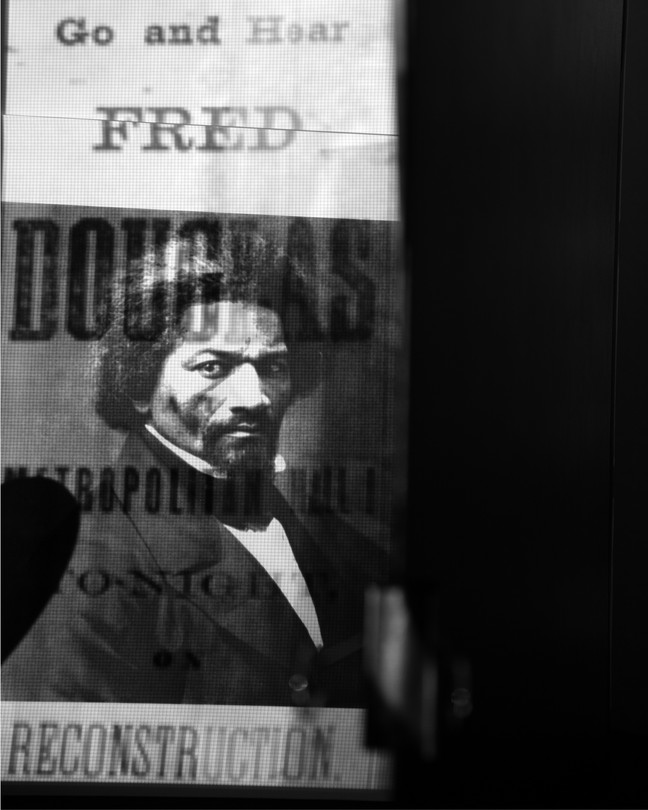

In 1866, Douglass took up his pen to try to capture this moment of transformation, both for himself and for the United States. For the December issue of this magazine that year, in an essay simply titled “ Reconstruction ,” Douglass observed that “questions of vast moment” lay before Congress and the nation. Nothing less than the essential results of the “tremendous war,” he writes, were at stake. Would the war become “a miserable failure … a scandalous and shocking waste of blood and treasure,” or a “victory over treason,” resulting in a newly reimagined nation “delivered from all contradictions and … based upon loyalty, liberty, and equality”? In this inquiry, Douglass’s new role as a conscience of the country became clarified. His leadership had always been through words and persuasion, written and oratorical. How, now that the war was over, would he employ his incomparable voice?

From the beginning, Reconstruction had faced three paramount questions: Who would rule in the South (defeated ex-Confederates or the victorious North?); who would rule in Washington, D.C. (Congress or the president?); and what were the meanings and dimensions of Black freedom? As of his writing in December, Douglass declared that nothing could yet be “considered final.” After ferocious debates, Congress had enacted the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and passed the Fourteenth Amendment, the latter still subject to ratification by three-quarters of the state legislatures. Violent anti-Black riots had occurred in Memphis and New Orleans that spring and summer, killing at least 48 people in the first city and at least 38 in the second. Much had been done to secure emancipation, but all remained in abeyance, awaiting legislation, human persuasion, and acts of political will.

As Douglass was writing, two visions of Reconstruction vied for national dominance in the fall elections. President Andrew Johnson, a Democrat from Tennessee, favored a policy of a lenient restoration, a plan that allowed for no Black civil and political rights and admitted the southern states back into the Union as quickly as possible. The Republican leadership of the House and the Senate, however, demanded a slower, harsher, and more transformative Reconstruction, a process that would establish state governments in the South that were more democratic. Black civil and political rights and enforcement mechanisms in federal law formed the backbone of these “Radical Republican” regimes.

Douglass was at this juncture a Radical Republican in the spirit of Thaddeus Stevens , the congressman from Pennsylvania who led the effort to impeach Johnson. Like Stevens, Douglass argued vehemently that Johnson had to be countered and thwarted by any legal means necessary or the promise of emancipation would fail. Douglass believed at the end of 1866 that, though only at its vulnerable beginning, the United States had been reinvented by war and by new egalitarian impulses rooted in emancipation. His essay is, therefore, full of radical brimstone, cautious hope, and a thoroughly new vision of constitutional authority. In careful but clear terms, he described Reconstruction as a revolution that would “cause Northern industry, Northern capital, and Northern civilization to flow into the South, and make a man from New England as much at home in Carolina as elsewhere in the Republic.” In short, he sought an overturning of history, the expansion of human rights forged from the fact of African American freedom—and from an idealism that soon would be sorely tested. Revolutions may or may not go backwards, but they surely give no rest to those who lead them.

David W. Blight is the Sterling Professor of American History at Yale and the author, most recently, of Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom .

RECONSTRUCTION by FREDERICK DOUGLASS

The assembling of the Second Session of the Thirty-ninth Congress may very properly be made the occasion of a few earnest words on the already much-worn topic of reconstruction.

Seldom has any legislative body been the subject of a solicitude more intense, or of aspirations more sincere and ardent. There are the best of reasons for this profound interest. Questions of vast moment, left undecided by the last session of Congress, must be manfully grappled with by this. No political skirmishing will avail. The occasion demands statesmanship. 1

Whether the tremendous war so heroically fought and so victoriously ended shall pass into history a miserable failure, barren of permanent results,—a scandalous and shocking waste of blood and treasure,—a strife for empire, as Earl Russell characterized it, of no value to liberty or civilization,—an attempt to re-establish a Union by force, which must be the merest mockery of a Union,—an effort to bring under Federal authority States into which no loyal man from the North may safely enter, and to bring men into the national councils who deliberate with daggers and vote with revolvers, and who do not even conceal their deadly hate of the country that conquered them; or whether, on the other hand, we shall, as the rightful reward of victory over treason, 2 have a solid nation, entirely delivered from all contradictions and social antagonisms, based upon loyalty, liberty, and equality, must be determined one way or the other by the present session of Congress.

The last session really did nothing which can be considered final as to these questions. The Civil Rights Bill and the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill and the proposed constitutional amendments, with the amendment already adopted and recognized as the law of the land, do not reach the difficulty, and cannot, unless the whole structure of the government is changed from a government by States to something like a despotic central government, with power to control even the municipal regulations of States, and to make them conform to its own despotic will. While there remains such an idea as the right of each State to control its own local affairs,—an idea, by the way, more deeply rooted in the minds of men of all sections of the country than perhaps any one other political idea,—no general assertion of human rights can be of any practical value. To change the character of the government at this point is neither possible nor desirable. All that is necessary to be done is to make the government consistent with itself, and render the rights of the States compatible with the sacred rights of human nature. 3

The arm of the Federal government is long, but it is far too short to protect the rights of individuals in the interior of distant States. They must have the power to protect themselves, or they will go unprotected, spite of all the laws the Federal government can put upon the national statute-book.

Slavery, like all other great systems of wrong, founded in the depths of human selfishness, and existing for ages, has not neglected its own conservation. It has steadily exerted an influence upon all around it favorable to its own continuance. And to-day it is so strong that it could exist, not only without law, but even against law. Custom, manners, morals, religion, are all on its side everywhere in the South; and when you add the ignorance and servility of the ex-slave to the intelligence and accustomed authority of the master, you have the conditions, not out of which slavery will again grow, but under which it is impossible for the Federal government to wholly destroy it, unless the Federal government be armed with despotic power, to blot out State authority, and to station a Federal officer at every cross-road. This, of course, cannot be done, and ought not even if it could. The true way and the easiest way is to make our government entirely consistent with itself, and give to every loyal citizen the elective franchise,—a right and power which will be ever present, and will form a wall of fire for his protection. 4

One of the invaluable compensations of the late Rebellion is the highly instructive disclosure it made of the true source of danger to republican government. Whatever may be tolerated in monarchical and despotic governments, no republic is safe that tolerates a privileged class, or denies to any of its citizens equal rights and equal means to maintain them. What was theory before the war has been made fact by the war.

There is cause to be thankful even for rebellion. It is an impressive teacher, though a stern and terrible one. In both characters it has come to us, and it was perhaps needed in both. It is an instructor never a day before its time, for it comes only when all other means of progress and enlightenment have failed. Whether the oppressed and despairing bondman, no longer able to repress his deep yearnings for manhood, or the tyrant, in his pride and impatience, takes the initiative, and strikes the blow for a firmer hold and a longer lease of oppression, the result is the same,—society is instructed, or may be. 5

Such are the limitations of the common mind, and so thoroughly engrossing are the cares of common life, that only the few among men can discern through the glitter and dazzle of present prosperity the dark outlines of approaching disasters, even though they may have come up to our very gates, and are already within striking distance. The yawning seam and corroded bolt conceal their defects from the mariner until the storm calls all hands to the pumps. Prophets, indeed, were abundant before the war; but who cares for prophets while their predictions remain unfulfilled, and the calamities of which they tell are masked behind a blinding blaze of national prosperity? 6

It is asked, said Henry Clay, on a memorable occasion, Will slavery never come to an end? That question, said he, was asked fifty years ago, and it has been answered by fifty years of unprecedented prosperity. Spite of the eloquence of the earnest Abolitionists,—poured out against slavery during thirty years,—even they must confess, that, in all the probabilities of the case, that system of barbarism would have continued its horrors far beyond the limits of the nineteenth century but for the Rebellion, and perhaps only have disappeared at last in a fiery conflict, even more fierce and bloody than that which has now been suppressed.

It is no disparagement to truth, that it can only prevail where reason prevails. War begins where reason ends. The thing worse than rebellion is the thing that causes rebellion. What that thing is, we have been taught to our cost. It remains now to be seen whether we have the needed courage to have that cause entirely removed from the Republic. At any rate, to this grand work of national regeneration and entire purification Congress must now address itself, with full purpose that the work shall this time be thoroughly done. 7 The deadly upas, root and branch, leaf and fibre, body and sap, must be utterly destroyed. The country is evidently not in a condition to listen patiently to pleas for postponement, however plausible, nor will it permit the responsibility to be shifted to other shoulders. Authority and power are here commensurate with the duty imposed. There are no cloud-flung shadows to obscure the way. Truth shines with brighter light and intenser heat at every moment, and a country torn and rent and bleeding implores relief from its distress and agony.

If time was at first needed, Congress has now had time. All the requisite materials from which to form an intelligent judgment are now before it. Whether its members look at the origin, the progress, the termination of the war, or at the mockery of a peace now existing, they will find only one unbroken chain of argument in favor of a radical policy of reconstruction. For the omissions of the last session, some excuses may be allowed. A treacherous President stood in the way; and it can be easily seen how reluctant good men might be to admit an apostasy which involved so much of baseness and ingratitude. 8 It was natural that they should seek to save him by bending to him even when he leaned to the side of error. But all is changed now. Congress knows now that it must go on without his aid, and even against his machinations. The advantage of the present session over the last is immense. Where that investigated, this has the facts. Where that walked by faith, this may walk by sight. Where that halted, this must go forward, and where that failed, this must succeed, giving the country whole measures where that gave us half-measures, merely as a means of saving the elections in a few doubtful districts. That Congress saw what was right, but distrusted the enlightenment of the loyal masses; but what was forborne in distrust of the people must now be done with a full knowledge that the people expect and require it. The members go to Washington fresh from the inspiring presence of the people. In every considerable public meeting, and in almost every conceivable way, whether at court-house, school-house, or cross-roads, in doors and out, the subject has been discussed, and the people have emphatically pronounced in favor of a radical policy. Listening to the doctrines of expediency and compromise with pity, impatience, and disgust, they have everywhere broken into demonstrations of the wildest enthusiasm when a brave word has been spoken in favor of equal rights and impartial suffrage. Radicalism, so far from being odious, is now the popular passport to power. The men most bitterly charged with it go to Congress with the largest majorities, while the timid and doubtful are sent by lean majorities, or else left at home. The strange controversy between the President and Congress, at one time so threatening, is disposed of by the people. The high reconstructive powers which he so confidently, ostentatiously, and haughtily claimed, have been disallowed, denounced, and utterly repudiated; while those claimed by Congress have been confirmed.

Of the spirit and magnitude of the canvass nothing need be said. The appeal was to the people, and the verdict was worthy of the tribunal. Upon an occasion of his own selection, with the advice and approval of his astute Secretary, soon after the members of Congress had returned to their constituents, the President quitted the executive mansion, sandwiched himself between two recognized heroes,—men whom the whole country delighted to honor,—and, with all the advantage which such company could give him, stumped the country from the Atlantic to the Mississippi, 9 advocating everywhere his policy as against that of Congress. It was a strange sight, and perhaps the most disgraceful exhibition ever made by any President; but, as no evil is entirely unmixed, good has come of this, as from many others. Ambitious, unscrupulous, energetic, indefatigable, voluble, and plausible,—a political gladiator, ready for a “set-to” in any crowd,—he is beaten in his own chosen field, and stands to-day before the country as a convicted usurper, a political criminal, guilty of a bold and persistent attempt to possess himself of the legislative powers solemnly secured to Congress by the Constitution. No vindication could be more complete, no condemnation could be more absolute and humiliating. Unless reopened by the sword, as recklessly threatened in some circles, this question is now closed for all time.