An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS. A lock ( Lock Locked padlock ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Funding at NSF

- Getting Started

- Search for Funding

- Search Funded Projects (Awards)

- For Early-Career Researchers

- For Postdoctoral Researchers

- For Graduate Students

- For Undergraduates

- For Entrepreneurs

- For Industry

- NSF Initiatives

- Proposal Budget

- Senior Personnel Documents

- Data Management Plan

- Research Involving Live Vertebrate Animals

- Research Involving Human Subjects

- Submitting Your Proposal

- How We Make Funding Decisions

- Search Award Abstracts

- NSF by the Numbers

- Honorary Awards

- Proposal and Award Policies and Procedures Guide (PAPPG)

- FAQ Related to PAPPG

- NSF Policy Office

- Safe and Inclusive Work Environments

- Research Security

- Research.gov

The U.S. National Science Foundation offers hundreds of funding opportunities — including grants, cooperative agreements and fellowships — that support research and education across science and engineering.

Learn how to apply for NSF funding by visiting the links below.

Finding the right funding opportunity

Learn about NSF's funding priorities and how to find a funding opportunity that's right for you.

Preparing your proposal

Learn about the pieces that make up a proposal and how to prepare a proposal for NSF.

Submitting your proposal

Learn how to submit a proposal to NSF using one of our online systems.

How we make funding decisions

Learn about NSF's merit review process, which ensures the proposals NSF receives are reviewed in a fair, competitive, transparent and in-depth manner.

NSF 101 answers common questions asked by those interested in applying for NSF funding.

Research approaches we encourage

Learn about interdisciplinary research, convergence research and transdisciplinary research.

Newest funding opportunities

Molecular foundations for sustainability: sustainable polymers enabled by emerging data analytics (mfs-speed), using long-term research associated data (ultra-data), national science foundation research traineeship institutional partnership pilot program, joint national science foundation and united states department of agriculture national institute of food and agriculture funding opportunity: supporting foundational research in robotics (frr).

100 Places to Find Funding For Your Research

- Grants.gov : Though backed by the Department of Health & Human Services, Grants.gov provides a valuable resource for searching for fellowships, grants, and other funding opportunities across multiple disciplines.

- Foundation Center : One of the largest databases of philanthropy in the United States contains information from more than 550 institutions eager to donate their money to creative, technical, medical, scientific, and plenty of other kinds of causes.

- Pivot : Pivot claims it hosts an estimated $44 billion worth of grants, fellowships, awards, and more, accessed by more than three million scholars worldwide.

- The Chronicle of Philanthropy New Grants : Another excellent search engine entirely dedicated to helping the most innovative thinkers obtain the money needed to move forward with their projects.

- Research Professional : Seven thousand opportunities await the driven at the well-loved Research Professional , which serves inclusively as a government-to-nonprofit grant database.

- Council on Foundations : Corporations, nonprofits, and other institutions gather here to talk best practices in philanthropy and where to find what for various projects.

- The Grantsmanship Center : Search for available research funding by state, see what givers prefer, and explore which ones offer up the most moolah.

- GrantSelect : Whether looking for money to advance an educational, nonprofit, artistic, or other worthwhile cause, GrantSelect makes it easy to find that funding.

- The Spencer Foundation : The Spencer Foundation provides research funding to outstanding proposals for intellectually rigorous education research.

- The Fulbright Program : The Fulbright Program offers grants in nearly 140 countries to further areas of education, culture, and science.

- Friends of the Princeton University Library : The Friends of the Princeton University Library offers short-term library research grants to promote scholarly use of the research collections.

- National Endowment for the Arts : The NEA's Office of Research & Analysis will make awards to support research that investigates the value and/or impact of the arts, either as individual components within U.S. arts ecology or as they interact with each other and/or with other domains of American life.

- Amazon Web Services : AWS has two programs to enable customers to move their research or teaching endeavors to the cloud and innovate quickly and at lower cost: The AWS Cloud Credits for Research program (formerly AWS Research Grants) and AWS Educate – a global initiative to provide students and educators with the resources needed to greatly accelerate cloud-related learning endeavors and to help power the entrepreneurs, workforce, and researchers of tomorrow.

- The National Association of State Boards of Accountancy Research Grants : The NASBA will fund and award up to three grants totaling up to $25,000 for one-year research projects, intended for researchers at higher institutions.

- The Tinker Foundation Research Grants : The Tinker Foundation Field Research Grants Program is designed to provide budding scholars with first-hand experience of their region of study, regardless of academic discipline.

- SPIN (Sponsored Programs Information Network) : SPIN is run by InfoEd International and requires an institutional subscription to access its global database for funding opportunities.

- GrantForward : GrantForward is a massive resource, full of grants from more than 9,000 sponsors in the United States. The site leverages data-crawling technology to constantly add new funding opportunities.

- Bush Foundation Fellowship Program : Leadership in its many forms are the main focus of the BFFP, who give money to folks dedicated to improving their communities.

Social and Civil

- National Endowment for Democracy : NGOs dedicated to furthering the cause of peace and democracy are the only ones eligible for grants from this organization.

- William T. Grant Foundation : Research and scholarship funding here goes towards advancing the cause of creating safe, healthy, and character-building environments for young people.

- Russell Sage Foundation : The Russell Sage Foundation focuses on best practices research feeding into equality and social justice initiatives.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts : Public policy is the name of the game here, where funding targets innovators looking to promote environmental, economic, and health programming causes reaching across demographics.

- The John Randolph Haynes Foundation : Based largely in Los Angeles, the John Randolph Haynes Foundation seeks to improve the city through a wide variety of altruistic projects.

- Economic and Social Research Council : This UK-based organization provides grants to researchers concerned with studying the social sciences in a manner that supports humanity's progress.

- The American Political Science Association : Stop here for fellowships, grants, internships, visiting scholars programs, and other chances to pay for political research.

- Social Science Research Council : In the interest of furthering an awareness of integral political issues, the SSRC donates to a wide range of initiatives worldwide.

- Horowitz Foundation for Social Policy : Several grants go out each year through this organization, covering all the social sciences and judged based on how well they fit into policymaking.

- The Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation : The Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation welcomes proposals from any of the natural and social sciences and the humanities that promise to increase understanding of the causes, manifestations, and control of violence and aggression. Highest priority is given to research that can increase understanding and amelioration of urgent problems of violence and aggression in the modern world.

- The National Endowment for the Humanities : Research grants from TNEH support interpretive humanities research undertaken by a team of two or more scholars. Research must use the knowledge and perspectives of the humanities and historical or philosophical methods to enhance understanding of science, technology, medicine, and the social sciences.

- American Historical Association : The American Historical Association awards several research grants to AHA members with the aim of advancing the study and exploration of history in a diverse number of subject areas. All grants are offered annually and are intended to further research in progress. Preference is given to advanced doctoral students, nontenured faculty, and unaffiliated scholars. Grants may be used for travel to a library or archive, as well as microfilming, photography, or photo copying, paying borrowing or access fees, or similar research expenses.

- The Dirksen Congressional Center : The Dirksen Congressional Center offers individual grants of up to $3500 for individuals with a serious interest in studying Congress. The Center encourages graduate students who have successfully defended their dissertation prospectus to apply, and awards a significant portion of the funds toward dissertation research.

- The Independent Social Research Foundation : The ISRF supports independent-minded researchers pursuing original and interdisciplinary studies for solutions to social problems that are unlikely to be funded by existing funding bodies.

- The David & Lucile Packard Foundation : Nonprofit organizations dedicated to growing education, charities, health, and other social justice causes should consider seeing what funding is available to them through this foundation.

- Volkswagen Stiftung : Volkswagen devotes its grants and other funding opportunities to a diverse portfolio of charities and charity-minded individuals.

Science and Engineering

- National Science Foundation : For the love of science! Head here when searching for ways to pay for that gargantuan geology or bigtime biology project. Awards are used for everything from undergraduate research grants to small business programs.

- Alexander von Humboldt Foundation : Humboldt fellows embody the spirit of science and leadership alike, and the organization sponsors thinkers in Germany and abroad alike.

- National Academy of Engineering : All of the awards dished out by the NAE celebrate engineering advances, education, and media promotion.

- National Parks Foundation : Americans who want to preserve their country's gorgeous parks and trails pitch projects to this governing body, concerned largely with ecology and accessibility issues.

- American Physical Society : Future Feynmans in search of the sponsorship necessary to test their theories (and explore possible applications) might want to consider applying for the APS' suite of awards.

- Alfred P. Sloan Foundation : Money is available here throughout the year, covering science and engineering as well as causes that overlap with civics, education, and economics.

- American Society for Engineering Education : The Department of Defense, NASA, The National Science Foundation, and other federal agencies sponsor high school and college students who show promise in the engineering sector.

- CRDF Global : Dedicated to peace and prosperity, recipients of CRDF Global grants apply their know-how to bettering social causes.

- Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council : Students and professionals working in the physical sciences as they relate to engineering might find a few options to their liking here.

- The Whitehall Foundation : The Whitehall Foundation, through its program of grants and grants-in-aid, assists scholarly research in the life sciences. It is the Foundation's policy to assist those dynamic areas of basic biological research that are not heavily supported by federal agencies or other foundations with specialized missions.

- Human Frontier Science Program : Research grants from the Human Frontier Science Program are provided for teams of scientists from different countries who wish to combine their expertise in innovative approaches to questions that could not be answered by individual laboratories.

- The U.S. Small Business Administration : The U.S. Small Business Administration offers research grants to small businesses that are engaged in scientific research and development projects that meet federal R&D objectives and have a high potential for commercialization.

- The Geological Society of America : The primary role of the GSA research grants program is to provide partial support of master's and doctoral thesis research in the geological sciences for graduate students enrolled in universities in the United States, Canada, Mexico, and Central America.

- The Welch Foundation : The Welch Foundation provides grants for a minimum of $60,000 in funding to support research in chemistry by a full-time tenured or tenurehttps://leakeyfoundation.org/grants/research-grants/-track faculty member who serves as principal investigator. Applications are restricted to universities, colleges, and other educational institutions located within the state of Texas.

- The Leakey Foundation : The Leakey Foundation offers research grants of up to $25,000 to doctoral and postdoctoral students, as well as senior scientists, for research related specifically to human origins.

- American College of Sports Medicine: The American College of Sports Medicine offers several possible grants to research students in the areas of general and applied science.

- Association of American Geographers : The AAG provides small grants to support research and fieldwork. Grants can be used only for direct expenses of research; salary and overhead costs are not allowed.

- The Alternatives Research & Development Foundation : The Alternatives Research & Development Foundation is a U.S. leader in the funding and promotion of alternatives to the use of laboratory animals in research, testing, and education.

- BD Biosciences : BD Biosciences Research Grants aim to reward and enable important research by providing vital funding to scientists pursuing innovative experiments that advance the scientific understanding of disease. This ongoing program includes grants for immunology and stem cell research, totaling $240,000 annually in BD Biosciences research reagents.

- Sigma Xi : The Sigma Xi program awards grants for research in the areas of science, engineering, astronomy, and vision.

- The United Engineering Foundation : The United Engineering Foundation advances the engineering arts and sciences for the welfare of humanity. It supports engineering and education by, among other means, developing and offering grants.

- Wilson Ornithological Society Research Grants : The Wilson Ornithological Society Research Grants offer up to four grants of $1,500 dollars each for work in any area of ornithology.

- National Institutes of Health : Foreign and American medical professionals hoping to advance their research might want to consider one of these prestigious (and generous) endowments.

- Whitaker International Program : Biomedical engineering's global reach serves as this organization's focus, so applicants here need to open themselves up to international institutions and applications.

- U.S. National Library of Medicine : From tech to small businesses, the USNLM funding programs cover a diverse range of fields that feed into medicine.

- American Heart Association : Most of the AHA's research involves cardiovascular disease and stroke, with funding in these areas available in both the winter and the summer.

- Society for Women's Health Research : Female engineers and scientists are eligible for these grants, meant to support initiatives that improves women's health and education on a global scale.

- Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation : Every cent donated to the DRCRF directly feeds into fellowships and awards bringing humanity closer to cancer cures and improved prevention regimens.

- Burroughs Wellcome Fund : Emerging scientists working in largely underrecognized and underfunded biomedical fields are the main recipients of this private foundation's awards.

- The Foundation for Alcohol Research : As one can probably assume from the name, The Foundation for Alcohol Research contributes to projects studying how alcohol impacts human physical and mental health.

- Alex's Lemonade Stand : These grants go towards doctors, nurses, and medical researchers concerned with curing childhood cancer.

- National Cancer Institute : Thanks to a little help from their friends in Congress, the National Cancer Institute have $4.9 billion to share with medical science researchers.

- Charles Stewart Mott Foundation : Michigan-based thinkers currently developing ways to improve upon serious local and state issues might want to consider checking out what this organization can offer in the way of funding for their ideas.

- American Federation for Aging Research : AFAR provides up to $100,000 for a one-to-two-year award to junior faculty (MDs and PhDs) to conduct research that will serve as the basis for longer term research efforts in the areas of biomedical and clinical research.

- The Muscular Dystrophy Association : The MDA is pursuing the full spectrum of research approaches that are geared toward combating neuromuscular diseases. MDA also helps spread this scientific knowledge and train the next generation of scientific leaders by funding national and international research conferences and career development grants.

- American Nurses Foundation : The ANF Nursing Research Grants Program provides funds to beginner and experienced nurse researchers to conduct studies that contribute toward the advancement of nursing science and the enhancement of patient care.

- The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation : The CF Foundation offers competitive awards for research related to cystic fibrosis. Studies may be carried out at the subcellular, cellular, animal, or patient levels. Two of these funding mechanisms include pilot and feasibility awards and research grants.

- The National Ataxia Foundation : The National Ataxia Foundation (NAF) is committed to funding the best science relevant to hereditary and sporadic types of ataxia in both basic and translational research. NAF invites research applications from USA. and International non-profit and for-profit institutions.

- The March of Dimes : In keeping with its mission, the March of Dimes research portfolio funds many different areas of research on topics related to preventing birth defects, premature birth, and infant mortality.

- The American Tinnitus Association : The American Tinnitus Association Research Grant Program financially supports scientific studies investigating tinnitus. Studies must be directly concerned with tinnitus and contribute to ATA's goal of finding a cure.

- American Brain Tumor Association : The American Brain Tumor Association provides multiple grants for scientists doing research in or around the field of brain tumor research.

- American Cancer Society : The American Cancer Society also offers grants that support the clinical and/or research training of health professionals. These Health Professional Training Grants promote excellence in cancer prevention and control by providing incentive and support for highly qualified individuals in outstanding training programs.

- Thrasher Research Fund : The Thrasher Research Fund provides grants for pediatric medical research. The Fund seeks to foster an environment of creativity and discovery aimed at finding solutions to children's health problems. The Fund awards grants for research that offer substantial promise for meaningful advances in prevention and treatment of children's diseases, particularly research that offers broad-based applications.

- Foundation for Physical Therapy : The Foundation supports research projects in any patient care specialty.

- International OCD Foundation : The IOCDF awards grants to investigators whose research focuses on the nature, causes, and treatment of OCD and related disorders.

- Susan G. Komen : Susan G. Komen sustains a strong commitment to supporting research that will identify and deliver cures for breast cancer.

- American Association for Cancer Research : The AACR promotes and supports the highest quality cancer research. The AACR has been designated as an organization with an approved NCI peer review and funding system.

- American Thyroid Foundation : The ATA is committed to supporting research into better ways to diagnose and treat thyroid disease.

- The National Patient Safety Foundation : The National Patient Safety Foundation (NPSF) Research Grants Program seeks to stimulate new, innovative projects directed toward enhancing patient safety in the United States. The program's objective is to promote studies leading to the prevention of human errors, system errors, patient injuries, and the consequences of such adverse events in a healthcare setting.

- The Foundation for Anesthesia Education and Research : The FAER provides research grant funding for anesthesiologists and anesthesiology trainees to gain additional training in basic science, clinical and translational, health-services-related, and education research.

- The Alzheimer's Association : The Alzheimer's Association funds a wide variety of investigations by scientists at every stage of their careers. Each grant is designed to meet the needs of the field and to introduce fresh ideas in Alzheimer's research.

- The Arthritis National Research Foundation : The Arthritis National Research Foundation seeks to move arthritis research forward to find new treatments and to cure arthritis.

- Hereditary Disease Foundation : The focus of the Hereditary Disease Foundation is on Huntington's disease. Support will be for research projects that will contribute to identifying and understanding the basic defect in Huntington's disease. Areas of interest include trinucleotide expansions, animal models, gene therapy, neurobiology and development of the basal ganglia, cell survival and death, and intercellular signaling in striatal neurons.

- The Children's Leukemia Research Association : The objective of the CLRA is to direct the funds of the Association into the most promising leukemia research projects, where funding would not duplicate other funding sources.

- The American Parkinson Disease Association : The APDA offers grants of up to $50,000 for Parkinson disease research to scientists affiliated with U.S. research institutions.

- The Mary Kay Foundation : The Mary Kay Foundation offers grants to select doctors and medical scientists for research focusing on curing cancers that affect women. Details for 2017 are forthcoming.

- The Crohn's & Colitis Foundation of America : The CCFA is a leading funder of basic and clinical research in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. CCFA supports research that increases understanding of the etiology, pathogenesis, therapy, and prevention of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis.

- American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons : ASES provides grants of up to $20,000 for promising shoulder and elbow research projects.

- The International Research Grants Program : The IRGP seeks to promote research that will have a major impact in developing knowledge of Parkinson's disease. An effort is made to promote projects that have little hope of securing traditional funding.

- American Gastroenterological Association : The AGA offers multiple grants for research advancing the science and practice of Gastroenterology.

- The Obesity Society : The Obesity Society offers grants of up to $25,000 dollars to members doing research in areas related to obesity.

- The Sjögren's Syndrome Foundation : The SSF Research Grants Program places a high priority on both clinical and basic scientific research into the cause, prevention, detection, treatment, and cure of Sjögren's.

- The Melanoma Research Foundation : The MRF Research Grant Program emphasizes both basic and clinical research projects that explore innovative approaches to understanding melanoma and its treatment.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian Dermatol Online J

- v.12(1); Jan-Feb 2021

Research Funding—Why, When, and How?

Shekhar neema.

Department of Dermatology, Armed Forces Medical College, Pune, Maharashtra, India

Laxmisha Chandrashekar

1 Department of Dermatology, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research (JIPMER), Dhanvantari Nagar, Puducherry, India

Research funding is defined as a grant obtained for conducting scientific research generally through a competitive process. To apply for grants and securing research funding is an essential part of conducting research. In this article, we will discuss why should one apply for research grants, what are the avenues for getting research grants, and how to go about it in a step-wise manner. We will also discuss how to write research grants and what to be done after funding is received.

Introduction

The two most important components of any research project is idea and execution. The successful execution of the research project depends not only on the effort of the researcher but also on available infrastructure to conduct the research. The conduct of a research project entails expenses on man and material and funding is essential to meet these requirements. It is possible to conduct many research projects without any external funding if the infrastructure to conduct the research is available with the researcher or institution. It is also unethical to order tests for research purpose when it does not benefit patient directly or is not part of the standard of care. Research funding is required to meet these expenses and smooth execution of research projects. Securing funding for the research project is a topic that is not discussed during postgraduation and afterwards during academic career especially in medical science. Many good ideas do not materialize into a good research project because of lack of funding.[ 1 ] This is an art which can be learnt only by practising and we intend to throw light on major hurdles faced to secure research funding.

Why Do We Need the Funds for Research?

It is possible to publish papers without any external funding; observational research and experimental research with small sample size can be conducted without external funding and can result in meaningful papers like case reports, case series, observational study, or small experimental study. However, when studies like multi-centric studies, randomized controlled trial, experimental study or observational study with large sample size are envisaged, it may not be possible to conduct the study within the resources of department or institution and a source of external funding is required.

Basic Requirements for Research Funding

The most important requirement is having an interest in the particular subject, thorough knowledge of the subject, and finding out the gap in the knowledge. The second requirement is to know whether your research can be completed with internal resources or requires external funding. The next step is finding out the funding agencies which provide funds for your subject, preparing research grant and submitting the research grant on time.

What Are the Sources of Research Funding? – Details of Funding Agencies

Many local, national, and international funding bodies can provide grants necessary for research. However, the priorities for different funding agencies on type of research may vary and this needs to be kept in mind while planning a grant proposal. Apart from this, different funding agencies have different timelines for proposal submission and limitation on funds. Details about funding bodies have been tabulated in Table 1 . These details are only indicative and not comprehensive.

Details of funding agencies

Application for the Research Grant

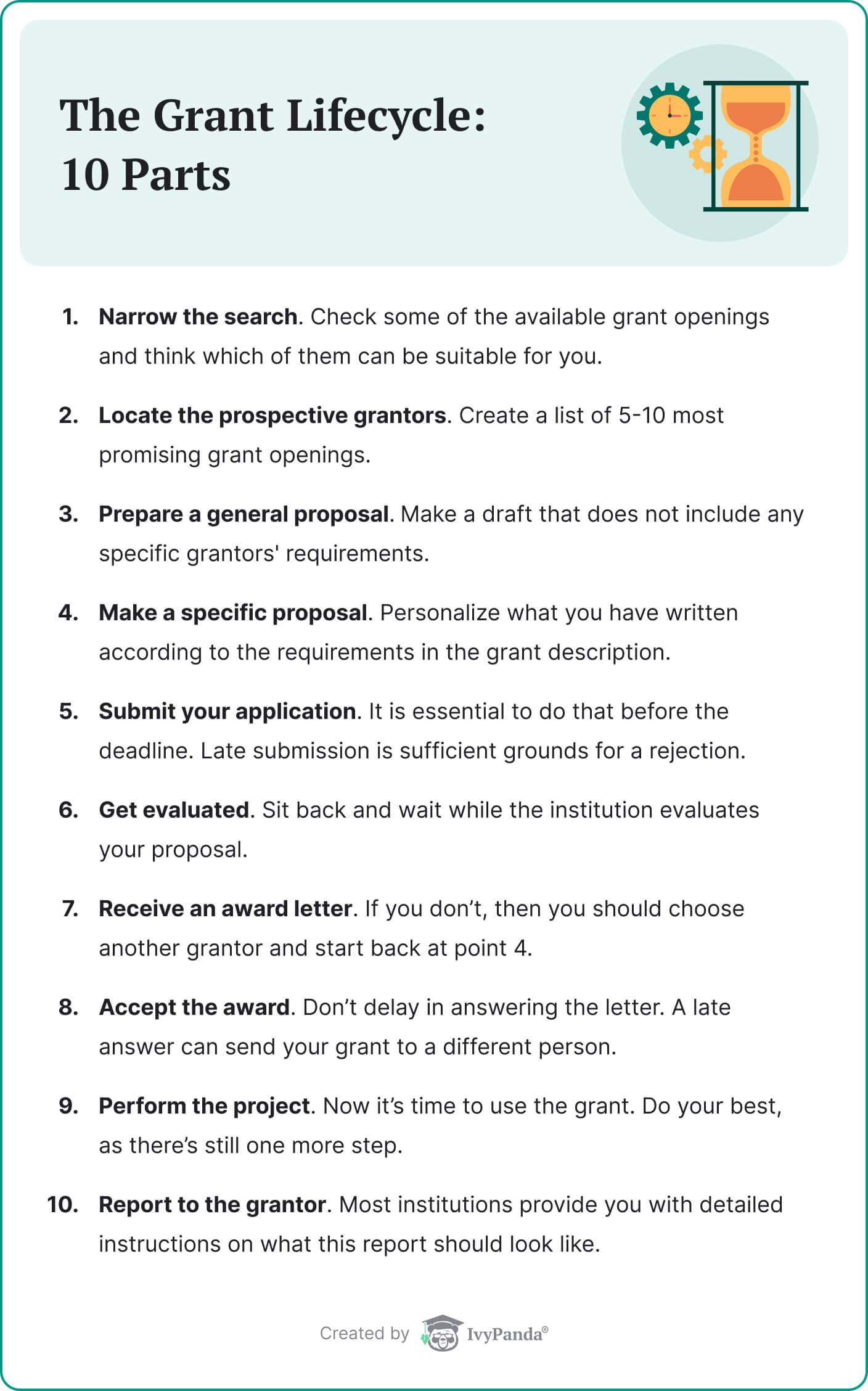

Applying for a research grant is a time-consuming but rewarding task. It not only provides an opportunity for designing a good study but also allows one to understand the administrative aspect of conducting research. In a publication, the peer review is done after the paper is submitted but in a research grant, peer review is done at the time of proposal, which helps the researcher to improve his study design even if the grant proposal is not successful. Funds which are available for research is generally limited; resulting in reviewing of a research grant on its merit by peer group before the proposal is approved. It is important to be on the lookout for call for proposal and deadlines for various grants. Ideally, the draft research proposal should be ready much before the call for proposal and every step should be meticulously planned to avoid rush just before the deadline. The steps of applying for a research grant are mentioned below and every step is essential but may not be conducted in a particular order.

- Idea: The most important aspect of research is the idea. After having the idea in mind, it is important to refine your idea by going through literature and finding out what has already been done in the subject and what are the gaps in the research. FINER framework should be used while framing research questions. FINER stands for feasibility, interesting, novel, ethical, and relevant

- Designing the study: Well-designed study is the first step of a well-executed research project. It is difficult to correct flawed study design when the project is advanced, hence it should be planned well and discussed with co-workers. The help of an expert epidemiologist can be sought while designing the study

- Collaboration: The facility to conduct the study within the department is often limited. Inter-departmental and inter-institutional collaboration is the key to perform good research. The quality of project improves by having a subject expert onboard and it also makes acceptance of grant easier. The availability of the facility for conduct of research in department and institution should be ascertained before planning the project

- Scientific and ethical committee approval: Most of the research grants require the project to be approved by the institutional ethical committee (IEC) before the project is submitted. IEC meeting usually happens once in a quarter; hence pre-planning the project is essential. Some institutes also conduct scientific committee meeting before the proposal can be submitted for funding. A project/study which is unscientific is not ethical, therefore it is a must that a research proposal should pass both the committees’ scrutiny

- Writing research grant: Writing a good research grant decides whether research funding can be secured or not. So, we will discuss this part in detail.

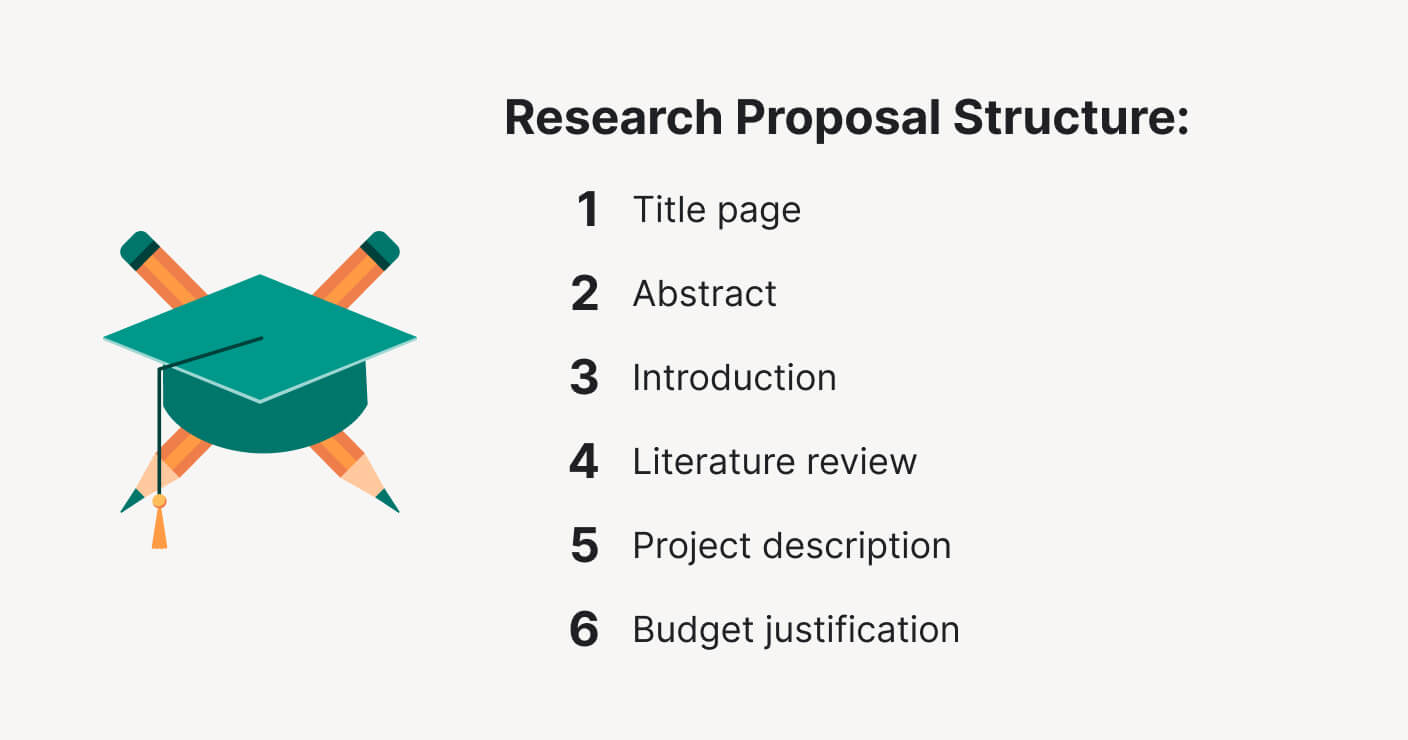

How to write a research grant proposal [ 13 , 14 , 15 ] The steps in writing a research grant are as follows

- Identifying the idea and designing the study. Study design should include details about type of study, methodology, sampling, blinding, inclusion and exclusion criteria, outcome measurements, and statistical analysis

- Identifying the prospective grants—the timing of application, specific requirements of grant and budget available in the grant

- Discussing with collaborators (co-investigators) about the requirement of consumables and equipment

- Preparing a budget proposal—the two most important part of any research proposal is methodology and budget proposal. It will be discussed separately

- Preparing a specific proposal as outlined in the grant document. This should contain details about the study including brief review of literature, why do you want to conduct this study, and what are the implications of the study, budget requirement, and timeline of the study

- A timeline or Gantt chart should always accompany any research proposal. This gives an idea about the major milestones of the project and how the project will be executed

- The researcher should also be ready for revising the grant proposal. After going through the initial proposal, committee members may suggest some changes in methodology and budgetary outlay

- The committee which scrutinizes grant proposal may be composed of varied specialities. Hence, proposal should be written in a language which even layman can understand. It is also a good idea to get the proposal peer reviewed before submission.

Budgeting for the Research Grant

Budgeting is as important as the methodology for grant proposal. The first step is to find out what is the monetary limit for grant proposal and what are the fund requirements for your project. If these do not match, even a good project may be rejected based on budgetary limitations. The budgetary layout should be prepared with prudence and only the amount necessary for the conduct of research should be asked. Administrative cost to conduct the research project should also be included in the proposal. The administrative cost varies depending on the type of research project.

Research fund can generally be used for the following requirement but not limited to these; it is helpful to know the subheads under which budgetary planning is done. The funds are generally allotted in a graded manner as per projected requirement and to the institution, not to the researcher.

- Purchase of equipment which is not available in an institution (some funding bodies do not allow equipment to be procured out of research funds). The equipment once procured out of any research fund is owned by the institute/department

- Consumables required for the conduct of research (consumables like medicines for the conduct of the investigator-initiated trials and laboratory consumables)

- The hiring of trained personnel—research assistant, data entry operator for smooth conduct of research. The remuneration details of trained personnel can be obtained from the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) website and the same can be used while planning the budget

- Stationary—for the printing of forms and similar expense

- Travel expense—If the researcher has to travel to present his finding or for some other reason necessary for the conduct of research, travel grant can be part of the research grant

- Publication expense: Some research bodies provide publication expense which can help the author make his findings open access which allows wider visibility to research

- Contingency: Miscellaneous expenditure during the conduct of research can be included in this head

- Miscellaneous expenses may include expense toward auditing the fund account, and other essential expenses which may be included in this head.

Once the research funding is granted. The fund allotted has to be expended as planned under budgetary planning. Transparency, integrity, fairness, and competition are the cornerstones of public procurement and should be remembered while spending grant money. The hiring of trained staff on contract is also based on similar principles and details of procurement and hiring can be read at the ICMR website.[ 4 ] During the conduct of the study, many of grant guidelines mandate quarterly or half-yearly progress report of the project. This includes expense on budgetary layout and scientific progress of the project. These reports should be prepared and sent on time.

Completion of a Research Project

Once the research project is completed, the completion report has to be sent to the funding agency. Most funding agencies also require period progress report and project should ideally progress as per Gantt chart. The completion report has two parts. The first part includes a scientific report which is like writing a research paper and should include all subheads (Review of literature, material and methods, results, conclusion including implications of research). The second part is an expense report including how money was spent, was it according to budgetary layout or there was any deviation, and reasons for the deviation. Any unutilized fund has to be returned to the funding agency. Ideally, the allotted fund should be post audited by a professional (chartered accountant) and an audit report along with original bills of expenditure should be preserved for future use in case of any discrepancy. This is an essential part of any funded project that prevents the researcher from getting embroiled in any accusations of impropriety.

Sharing of scientific findings and thus help in scientific advancement is the ultimate goal of any research project. Publication of findings is the part of any research grant and many funding agencies have certain restrictions on publications and presentation of the project completed out of research funds. For example, Indian Association of Dermatologists, Venereologists and Leprologists (IADVL) research projects on completion have to be presented in a national conference and the same is true for most funding agencies. It is imperative that during presentation and publication, researcher mentions the source of funding.

Research funding is an essential part of conducting research. To be able to secure a research grant is a matter of prestige for a researcher and it also helps in the advancement of career.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

Grants & funding.

The National Institutes of Health is the largest public funder of biomedical research in the world. In fiscal year 2022, NIH invested most of its $45 billion appropriations in research seeking to enhance life, and to reduce illness and disability. NIH-funded research has led to breakthroughs and new treatments helping people live longer, healthier lives, and building the research foundation that drives discovery.

three-scientists-goggles-test-tube.jpg

Grants Home Page

NIH’s central resource for grants and funding information.

lab-glassware-with-colorful-liquid-square.jpg

Find Funding

NIH offers funding for many types of grants, contracts, and even programs that help repay loans for researchers.

calendar-page-square.jpg

Grant applications and associated documents (e.g., reference letters) are due by 5:00 PM local time of application organization on the specified due date.

submit-key-red-square.jpg

How to Apply

Instructions for submitting a grant application to NIH and other Public Health Service agencies.

female-researcher-in-lab-square.jpg

About Grants

An orientation to NIH funding, grant programs, how the grants process works, and how to apply.

binder-with-papers-on-office-desk-square.jpg

Policy & Compliance

By accepting a grant award, recipients agree to comply with the requirements in the NIH Grants Policy Statement unless the notice of award states otherwise.

blog-key-blue-square.jpg

Grants News/Blog

News, updates, and blog posts on NIH extramural grant policies, processes, events, and resources.

scientist-flipping-through-report-square.jpg

Explore opportunities at NIH for research and development contract funding.

smiling-female-researcher-square.jpg

Loan Repayment

The NIH Loan Repayment Programs repay up to $50,000 annually of a researcher’s qualified educational debt in return for a commitment to engage in NIH mission-relevant research.

Connect with Us

- More Social Media from NIH

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

Funding for Research: Importance, Types of Funding, and How to Apply

Embarking on a PhD or research journey is akin to embarking on a quest for knowledge, a quest that often hinges on a crucial ally – funding for research. However, in a highly competitive environment, funding is hard to secure as more researchers enter the field every year. According to the UNESCO Science report, global research expenditure increased by 19.2% between 2014 and 2018, with a 3x faster increase in the researcher pool than the global population during the same period. [1] In this article, we unravel the intricacies of funding for research, exploring its paramount importance, the types of research funding available, and how to navigate the funding maze in research.

Table of Contents

Importance of Funding for Research

Not only does research play a significant role in influencing decisions and policies across various sectors, it is essential in expanding our understanding of the world and finding solutions to global issues. And at the heart of groundbreaking discoveries lies funding, the catalyst that fuels innovation. But how does funding work? Funding for research isn’t merely about financial sustenance; it’s about unlocking the doors to securing resources, enabling researchers to traverse the path from ideation to innovation that makes tangible contributions to human knowledge. It enables researchers to push boundaries, facilitating access to cutting-edge technologies, specialized equipment, and expert collaborations. Unfortunately, it is common to see potentially valuable research initiatives languishing due to a lack of adequate resources and insufficient funding. This is why identifying the best types of funding and applying for research grants becomes important for researchers.

Understanding the Types of Research Funding

Let’s take a look at the different types of research funding that is usually available to researchers and how they can benefit from them.

Scholarships and fellowships

Most reputed academic institutions and universities have certain standard mechanisms for research funding through grants, scholarships, and fellowships. Generally, these sources of funding are meant for students and researchers who are affiliated with the institution and can be availed by faculty members too. Apart from space in the university library, they can cover a spectrum of resources, including tuition, travel, and stipends. It’s important to note that some scholarships and fellowships may have specific eligibility criteria, such as academic achievements or research focus, so applicants should carefully review these requirements. So be sure to gather as much information as possible, including what is on offer, details of stipends, and the duration of the scholarships and fellowships that you apply for.

Seed funding

Imagine you have a brilliant idea and all you need is a small amount of funding or capital to get it off the ground. This is where seed funding comes in to provide initial funding (generally small) to researchers to support the early stages of research. These research grants are usually given to cover short periods ranging from a few months to a year. The work is closely evaluated by the funding agency to get a sense of how good or innovative the research idea is. The evaluation process for seed funding often focuses on the potential impact and feasibility of the research idea. Researchers should be prepared to provide a compelling case for how their work aligns with the funding agency’s goals and contributes to the advancement of knowledge. A good example of a seed-funder is the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation backed Grand Challenges in Global Health Exploration Grants.

Project funding

This is a type of funding that most academic institutions and universities are geared towards providing. Project funding is given to a team behind a research idea or project for a period ranging from 3 to 5 years. The competitive nature of project funding necessitates a clear and comprehensive research proposal that outlines the objectives, methods, and expected outcomes. To be successful in securing project funding it is essential to emphasize the significance of the research question and the expertise of the team working on stimulating new ideas or projects.

Centre funding

Here, the size of the funds is usually greater compared to project funding, which is granted after a comprehensive assessment of the work program and the team’s capabilities. The objective of center funding is to provide resources for an entire program that can comprise several different research projects. The duration of the funding ranges from 3 to 6 years or even longer depending on various factors. Researchers seeking center funding should showcase a cohesive and impactful research program that aligns with the funder’s strategic priorities.

Prizes and awards

This is usually characterized as recognition and financial support for past contributions in research or a field of study. This type of research funding is to encourage and incentivize project teams and researchers to carry out further innovative work. These types of research funding are very competitive and often require a strong track record of research achievements. They can entail either money or a cash prize or award in the form of a contract with a funding agency.

How to Apply for Research Funding

Strategic Timing: When it comes to securing funding for research, timing is everything. Plan your funding applications strategically, aligning them with critical milestones in your research. Consider the academic calendar, project timelines, and funding cycles to optimize your chances of securing funding for research.

Thorough Preparation: Before diving into the application process, conduct thorough groundwork. Familiarize yourself with the funding organization’s mission, priorities, expectations, and application, requirements. Clarify your research idea and design and then tailor your proposal to align seamlessly with their goals.

Crafting a Compelling Proposal: Your proposal for a research grant is your voice in the funding arena. Clearly articulate the significance of your research, your methodology, the possible outcomes, and the anticipated impact along with timelines. Your proposal will be scrutinized by a seasoned committee so craft it with precision, clarity, and a compelling narrative to ensure it can be easily understood even by non-academics.

Additional Tips to Secure Research Funding

Building Collaborations: Cultivate partnerships within and beyond your institute as collaboration adds weight to your funding application. A multidisciplinary approach not only strengthens your proposal but also enhances the potential impact of your research.

Staying Informed: The world of research funding is dynamic. Stay informed about emerging funding opportunities, policy changes, and shifts in research priorities. Regularly check funding databases, attend workshops, and engage with your academic community to maximize your chance of success.

Embracing Diversity in Funding Sources: Diversify your research funding portfolio as relying solely on one source of funding for research can be precarious. Explore various avenues, balancing government grants, private foundations, and industry collaborations to create a resilient funding strategy.

Being Resilient in the Face of Rejections: Rejections are an inherent part of the funding journey. View them not as setbacks but as opportunities to refine and strengthen your proposals. Seek feedback, learn from the process, and persist in your pursuit.

If you are a serious researcher wondering how to get funding for research then do check out GrantDesk a solution by Researcher.Life . It provides expert support aimed at revolutionizing the funding process and increasing your chances of securing research grants.

References:

- Schneegans, T. Straza and J. Lewis (eds). UNESCO (2021) UNESCO Science Report: the Race Against Time for Smarter Development.

Researcher.Life is a subscription-based platform that unifies top AI tools and services designed to speed up, simplify, and streamline a researcher’s journey, from reading to writing, submission, promotion and more. Based on over 20 years of experience in academia, Researcher.Life empowers researchers to put their best research forward and move closer to success.

Try for free or sign up for the Researcher.Life All Access Pack , a one-of-a-kind subscription that unlocks full access to an AI academic writing assistant, literature reading app, journal finder, scientific illustration tool, and exclusive discounts on professional services from Editage. Find the best AI tools a researcher needs, all in one place – Get All Access now for prices starting at just $17 a month !

Related Posts

Levels of Measurement: Nominal, Ordinal, Interval, and Ratio (with Examples)

How to Write a Research Paper Outline (with Examples)

Search for:

Candid Learning

Candid learning offers information and resources that are specifically designed to meet the needs of grantseekers..

Candid Learning > Resources > Knowledge base

How do I find funding for my research?

Because most private foundations make grants only to nonprofit organizations, individuals seeking grants must follow a different funding path than public charities. You need to be both creative and flexible in your approach to seeking funding.

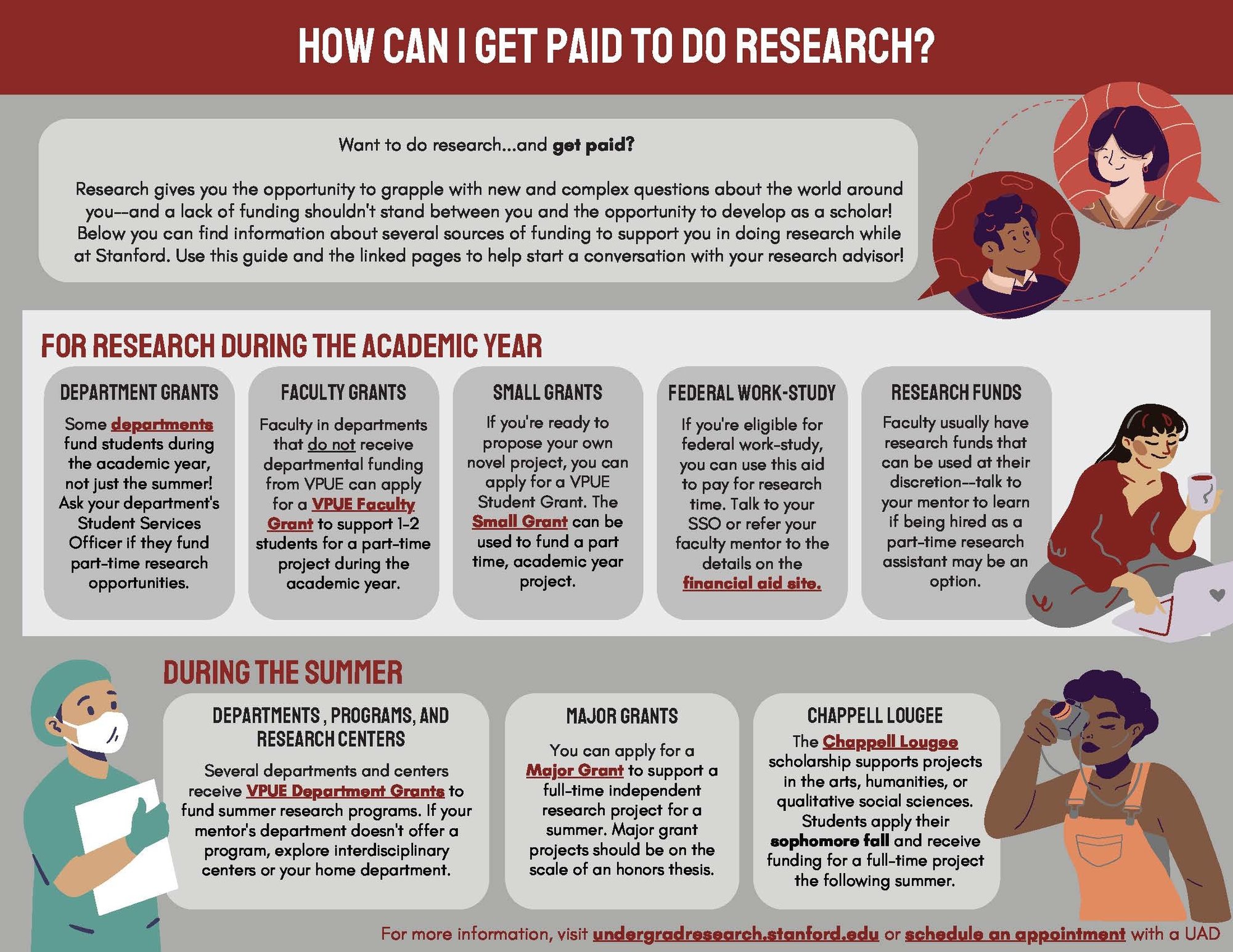

If you are affiliated with a college or university, contact your department office. Some colleges and universities have an office for sponsored programs, which coordinates grant requests and helps researchers with finding grant opportunities.

Also ask your peers and colleagues about funding sources. Please note that many national organizations may have local chapters that may run their own funding programs. National chapters might not know what their local chapters are offering, so it is up to you to check at each level.

Another approach is to find a nonprofit with a similar interest that will act as your fiscal sponsor. In this arrangement, you might qualify for more funding opportunities. Click here to learn learn more about fiscal sponsorship.

Some grantmakers offer support for individual projects. Candid offers the following resources that can help researchers find grants:

Foundation Directory is our searchable database of grantmakers. Perform an advanced search by Transaction Type: Grants to Individuals, in addition to search terms for Subject Area and Geographic Focus. For more detailed search help, please see our article, Find your next scholarship, fellowship, or grant on Foundation Directory Professional.

Subscribe to search from your own location, or search for free at our Candid partner locations .

If you are unfamiliar with the process of grantseeking, you may want to start with these:

- Introduction to Finding Grants , our free tutorial

- Our students and researchers resources

See more Knowledge Base articles related to this topic:

- How do I write a grant proposal for my individual project? Where can I find samples? - Where can I find information about financial aid as a graduate student?

More articles for individual grantseekers

Have a question about this topic? Ask us!

Candid's Online Librarian service will answer your questions within two business days.

Explore resources curated by our staff for this topic:

Staff-recommended websites.

Includes requests for research proposals. Records include funding organization(s), brief description of eligibility and application requirements, deadline, and link to original notice. Searchable by subject or keyword. Subscribe for a free weekly email digest or RSS feed.

Where to Search for Funding

Sponsored by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, this page includes links to free and fee-based grant funding resources.

Grants & Funding: NIH Central Resource

The Office of Extramural Research offers grants in the form of fellowships and support for research projects in the field of biomedicine.

One of the largest funders of humanities programs in the United States. Grants typically go to cultural institutions, such as museums, archives, libraries, colleges, universities, public television, and radio stations, and to individual scholars.

Active Funding Opportunities--Recently Announced

Promotes and advances scientific progress in the United States by competitively awarding grants and cooperative agreements for research and education in the sciences, mathematics, and engineering.

The official site for federal award recipients, it ties together all federal award information including federal assistance and contracting opportunities.

The "electronic storefront for federal grants," organized by topic. Selecting a topic provides links to funding pages for the 26 federal grantmaking agencies, some of which support individual research projects. It offers users “full service electronic grant administration” with guidelines and grant applications available online.

On the Art of Writing Proposals

Eight pages of proposal writing advice for scholarly researchers.

Grant Proposals (or Give me the money!)

This handout will help you write and revise grant proposals for research funding in all academic disciplines (sciences, social sciences, humanities, and the arts). Targeted primarily to graduate students and faculty, but also helpful to undergraduates who are seeking funding for research (e.g. for a senior thesis). Includes sample budget and project timeline.

Scholar Rescue Fund

Provides fellowships for established scholars whose lives and work are threatened in their home countries. One-year fellowships support temporary academic positions at universities, colleges and other higher learning institutions in safe locations anywhere in the world, enabling them to pursue their academic work. If safe return is not possible, the scholar may use the fellowship period to identify a longer-term opportunity.

Social Science Research Council

Supports fellowships and grant programs in the social sciences. The Fellowship and Prizes section of the web site provides access to information on current funding opportunities and online applications.

Awards & Grants

Describes more than 450 organizations that grant fellowships, awards, and prizes to historians. Some of this information is available online only to members of AHA.

Staff-recommended books

The Grant Writer's Handbook: How To Write A Research Proposal And Succeed

Find: Amazon | Free eBook

Grant Seeking in Higher Education: Strategies and Tools for College Faculty

Sign up for our newsletter.

What is research funding, how does it influence research, and how is it recorded? Key dimensions of variation

- Open access

- Published: 16 September 2023

- Volume 128 , pages 6085–6106, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Mike Thelwall ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6065-205X 1 , 2 ,

- Subreena Simrick ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0170-6940 3 ,

- Ian Viney ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9943-4989 4 &

- Peter Van den Besselaar ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8304-8565 5 , 6

4773 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Evaluating the effects of some or all academic research funding is difficult because of the many different and overlapping sources, types, and scopes. It is therefore important to identify the key aspects of research funding so that funders and others assessing its value do not overlook them. This article outlines 18 dimensions through which funding varies substantially, as well as three funding records facets. For each dimension, a list of common or possible variations is suggested. The main dimensions include the type of funder of time and equipment, any funding sharing, the proportion of costs funded, the nature of the funding, any collaborative contributions, and the amount and duration of the grant. In addition, funding can influence what is researched, how and by whom. The funding can also be recorded in different places and has different levels of connection to outputs. The many variations and the lack of a clear divide between “unfunded” and funded research, because internal funding can be implicit or unrecorded, greatly complicate assessing the value of funding quantitatively at scale. The dimensions listed here should nevertheless help funding evaluators to consider as many differences as possible and list the remainder as limitations. They also serve as suggested information to collect for those compiling funding datasets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Exploring the effectiveness, efficiency and equity (3e’s) of research and research impact assessment

Obtaining Support and Grants for Research

Myths, Challenges, Risks and Opportunities in Evaluating and Supporting Scientific Research

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Academic research grants account for billions of pounds in many countries and so the funders may naturally want to assess their value for money in the sense of financing desirable outcomes at a reasonable cost (Raftery et al., 2016 ). Since many of the benefits of research are long term and difficult to identify or quantify financially, it is common to benchmark against previous results or other funders to judge progress and efficiency. This is a complex task because academic funding has many small and large variations and is influenced by, and may influence, many aspects of the work and environment of the funded academics (e.g., Reale et al., 2017 ). The goal of this article is to support future analyses of the effectiveness or influence of grant funding by providing a typology of the important dimensions to be considered in evaluations (or otherwise acknowledged as limitations). The focus is on grant funding rather than block funding.

The ideal way to assess the value of a funding scheme would be a counterfactual analyses that showed its contribution by identifying what would have happened without the funding. Unfortunately, counterfactual analyses are usually impossible because of the large number of alternative funding sources. Similarly, comparisons between successful and unsuccessful bidders are faced with major confounding factors that include groups not winning one grant winning another (Neufeld, 2016 ), and complex research projects attracting funding of different kinds from multiple sources (Langfeldt et al., 2015 ; Rigby, 2011 ). Even analyses with effective control groups, such as a study of funded vs. unfunded postdocs (Schneider & van Leeuwen, 2014 ), cannot separate the effect of the funding from the success of the grant selection process: were better projects funded or did the funding or reviewer feedback improve the projects? Although qualitative analyses of individual projects help to explain what happened to the money and what it achieved, large scale analyses are sometimes needed to inform management decision making. For example: would a funder get more value for money from larger or smaller, longer or shorter, more specific or more general grants? For such analyses, many simplifying assumptions need to be made. The same is true for checks of the peer review process of research funders. For example, a funder might compute the average citation impact of publications produced by their grants and compare it to a reference set. This reference set might be as outputs from the rejected set or outputs from a comparable funder. The selection of the reference set is crucial for any attempt to identify the added value of any funding, however defined. For example, comparing the work of grant winners with that of high-quality unsuccessful applicants (e.g., those that just failed to be funded) would be useful to detect the added value of the money rather than the success of the procedure to select winners, assuming that there is little difference in potential between winners and narrow losers (Van den Besselaar & Leydesdorff, 2009 ). Because of the need to make comparisons between groups of outputs based on the nature of their funding, it is important to know the major variations in academic research funding types.

The dimensions of funding analysed in previous evaluations can point to how the above issues have been tackled. Unfortunately, most evaluations of the effectiveness, influence, or products of research funding (however defined) have probably been private reports for or by research funders, but some are in the public domain. Two non-funder studies have analysed whether funding improves research in specific contexts: peer review scores for Scoliosis conference submissions (Roach et al., 2008 ), and the methods of randomised controlled trials in urogynecology (Kim et al., 2018 ). Another compared research funded by China with that funded by the EU (Wang et al., 2020 ). An interesting view on the effect of funding on research output suggests that a grant does not necessarily always result in increased research output compared to participation in a grant competition (Ayoubi et al., 2019 ; Jonkers et al., 2017 ). Finally, a science-wide study of funding for journal articles from the UK suggested that it associated with higher quality research in at least some and possibly all fields (the last figure in: Thelwall et al., 2023 ).

From a different perspective, at least two studies have investigated whether academic funding has commercial value. The UK Medical Research Council (MRC) has analysed whether medical spinouts fared better if they were from teams that received MRC funding rather than from unsuccessful applicants, suggesting that funding helped spin-outs to realise commercial value from their health innovations (Annex A2.7 of: MRC, 2019 ). Also in the UK, firms participating in UK research council funded projects tended to grow faster afterwards compared to comparator firms (ERC, 2017 ).

Discussing the main variations in academic research funding types to inform analyses of the value of research funding is the purpose of the current article. Few prior studies seem to have introduced any systematic attempt to characterise the key dimensions of research funding, although some have listed several different types (e.g., four in: Garrett-Jones, 2000 ; three in: Paulson et al., 2011 ; nine in: Versleijen et al., 2007 ). The focus of the current paper is on grant-funded research conducted at least partly by people employed by an academic institution rather than by people researching as part of their job in a business, government, or other non-academic organisation. The latter are presumably funded usually by their employer, although they may sometimes conduct collaborative projects with academics or win academic research funding. The focus is also on research outputs, such as journal articles, books, patents, performances, or inventions, rather than research impacts or knowledge generation. Nevertheless, many of the options apply to the more general case. The list of dimensions relevant to evaluating the value of research funding has been constructed from a literature review of academic research about funding and insights from discussions with funders and analyses of funding records. The influence of funding on individual research projects is analysed, rather than systematic effects of funding, such as at the national level (e.g., for this, see: Sandström & Van den Besselaar, 2018 ; Van den Besselaar & Sandström, 2015 ). The next sections discuss dimensions in difference in the funding awarded, the influence of the funding on the research, and the way in which the funding is recorded.

Funding sources

There are many types of funders of academic research (Hu, 2009 ). An effort to distinguish between types of funding schemes based on a detailed analysis of the Dutch government budget and the annual reports of the main research funders in the Netherlands found the following nine types of funding instruments (Versleijen et al., 2007 ), but the remainder of this section gives finer-grained breakdown of types. The current paper is primarily concerned with all these except for the basic funding category, which includes the block grants that many universities receive for general research support. Block grants were originally uncompetitive but now may also be fully competitive, as in the UK where they depend on Research Excellence Framework scores, or partly competitive as in the Netherlands, where they partly depend on performance-based parameters like PhD completions (see also: Jonkers & Zacharewicz, 2016 ).

Contract research (project—targeted—small scale)

Open competition (project—free—small scale)

Thematic competition (project—targeted—small scale)

Competition between consortia (project—targeted—large scale)

Mission oriented basic funding (basic—targeted—large scale)

Funding of infrastructure and equipment (basic—targeted—diverse)

Basic funding for universities and public research institutes (basic—free—large scale)

International funding of programs and institutes (basic, both, mainly large scale)

EU funding (which can be subdivided in the previous eight types)

Many studies of the influence of research funding have focused on individual funders (Thelwall et al, 2016 ) and funding agencies’ (frequently unpublished) internal analyses presumably often compare between their own funding schemes, compare overall against a world benchmark, or check whether a funding scheme performance has changed over time (BHF, 2022 ). Public evaluations sometimes analyse individual funding schemes, particularly for large funders (e.g., Defazio et al., 2009 ). The source of funding for a project could be the employing academic institution, academic research funders, or other organisations that sometimes fund research. There are slightly different sets of possibilities for equipment and time funding.

Who funded the research project (type of funder)?

A researcher may be funded by their employer, a specialist research funding organisation (e.g., government-sponsored or non-profit) or an organisation that needs the research. Commercial funding seems likely to have different requirements and goals from academic funding (Kang & Motohashi, 2020 ), such as a closer focus on product or service development, different accounting rules, and confidentiality agreements. The source of funding is an important factor in funding analysis because funders have different selection criteria and methods to allocate and monitor funding. This is a non-exhaustive list.

Self-funded or completely unfunded (individual). Although the focus of this paper is on grant funding, this (and the item below) may be useful to record because it may partly underpin projects with other sources and may form parts of comparator sets (e.g., for the research of unfunded highly qualified applicants) in other contexts.

University employer. This includes funding reallocated from national competitive (e.g., performance-based research funding: Hicks, 2012 ) or non-competitive block research grants, from teaching income, investments and other sources that are allocated for research in general rather than equipment, time, or specific projects.

Other university (e.g., as a visiting researcher on a collaborative project).

National academic research funder (e.g., the UK’s Economic and Social Research Council: ESRC).

International academic research funder (e.g., European Union grants).

Government (contract, generally based on a tender and not from a pot of academic research funding)

Commercial (contract or research funding), sometimes called industry funding.

NGO (contract or research funding, e.g., Cancer Research charity). Philanthropic organisations not responsible to donors may have different motivations to charities, so it may be useful to separate the two sometimes.

Who funded the time needed for the research?

Research typically needs both people and equipment, and these two are sometimes supported separately. The funding for a researcher, if any, might be generic and implicit (it is part of their job to do research) or explicit in terms of a specified project that needs to be completed. Clinicians can have protected research time too: days that are reserved for research activities as part of their employment, including during advanced training (e.g., Elkbuli et al., 2020 ; Voss et al., 2021 ). For academics, research time is sometimes “borrowed” from teaching time (Bernardin, 1996 ; Olive, 2017 ). Time for a project may well be funded differently between members, such as the lead researcher being institutionally supported but using a grant to hire a team of academic and support staff. Inter-institutional research may also have a source for each team. The following list covers a range of different common arrangements.

Independent researcher, own time (e.g., not employed by but emeritus or affiliated with a university).

University researcher, own time (e.g., holidays, evenings, weekends).

University, percentage of the working time of academic staff devoted for research. In some countries this is large related to the amount of block finding versus project funding (Sandström & Van den Besselaar, 2018 ).

University, time borrowed from other activities (e.g., teaching, clinical duties, law practice).

Funder, generic research time funding (e.g., Gates chair of neuropsychology, long term career development funding for a general research programme).

University/Funder, specific time allocated for research programme (e.g., five years to develop cybersecurity research expertise).

University/Funder, employed for specific project (e.g., PhD student, postdoc supervised by member of staff).

University/Funder, specific time allocated for specific study (e.g., sabbatical to write a book).

Who funded the equipment or other non-human resources used in the research?

The resources needed for a research project might be funded as part of the project by the main funder, it may be already available to the researcher (e.g., National Health Service equipment that an NHS researcher could expect to access), or it may be separately funded and made available during the project (e.g., Richards, 2019 ). Here, “equipment” includes data or samples that are access-controlled as well as other resources unrelated to pay, such as travel. These types can be broken down as follows.

Researcher’s own equipment (e.g., a musician’s violin for performance-based research or composition; an archaeologist’s Land Rover to transport equipment to a dig).

University equipment, borrowed/repurposed (e.g., PC for teaching, unused library laptop).

University equipment, dual purpose (e.g., PC for teaching and research, violin for music teaching and research).

University/funder equipment for generic research (e.g., research group’s shared microbiology lab).

University/funder equipment research programme (e.g., GPU cluster to investigate deep learning).

University/funder equipment for specific project (e.g., PCs for researchers recruited for project; travel time).

University/funder equipment for single study (e.g., travel for interviews).

Of course, a funder may only support the loan or purchase of equipment on the understanding that the team will find other funding for research projects using it (e.g., “Funding was provided by the Water Research Commission [WRC]. The Covidence software was purchased by the Water Research fund”: Deglon et al., 2023 ). Getting large equipment working for subsequent research (e.g., a space telescope, a particle accelerator, a digitisation project) might also be the primary goal of a project.

How many funders contributed?

Although many projects are funded by a single source, some have multiple funders sharing the costs by agreement or by chance (Davies, 2016 ), and the following seem to be the logical possibilities for cost sharing.

Partially funded from one source, partly unfunded.

Partially funded from multiple sources, partly unfunded.

Fully funded from multiple sources.

Fully funded from a single source.

As an example of unplanned cost sharing, a researcher might have their post funded by one source and then subsequently bid for funding for equipment and support workers to run a large project. This project would then be part funded by the two sources, but not in a coordinated way. It seems likely that a project with a single adequate source of funding might be more efficient than a project with multiple sources that need to be coordinated. Conversely, a project with multiple funders may have passed through many different quality control steps or shown relevance to a range of different audiences. Those funded by multiple sources may also be less dependent on individual funders and therefore more able to autonomously follow their own research agenda, potentially leading to more innovative research.

How competitive was the funding allocation process?

Whilst government and charitable funding is often awarded on a competitive basis, the degree of competition (e.g., success rate) clearly varies between countries and funding calls and changes over time. In contrast, commercial funding may be gained without transparent competition (Kang & Motohashi, 2020 ), perhaps as part of ongoing work in an established collaboration or even due to a chance encounter. In between these, block research grants and prizes may be awarded for past achievements, so they are competitive, but the recipients are relatively free to spend on any type of research and do not need to write proposals (Franssen et al., 2018 ). Similarly, research centre grants may be won competitively but give the freedom to conduct a wide variety of studies over a long period. This gives the following three basic dimensions.

The success rate from the funding call (i.e., the percentage of initial applicants that were funded) OR

The success rate based on funding awarded for past performance (e.g., prize or competitive block grant, although this may be difficult to estimate) OR

The contract or other funding was allocated non-competitively (e.g., non-competitive block funding).

How was the funding decision made?

Who decides on which researchers receive funding and through which processes is also relevant (Van den Besselaar & Horlings, 2011 ). This is perhaps one of the most important considerations for funders.

The procedure for grant awarding: who decided and how?

There is a lot of research into the relative merits of different selection criteria for grants, such as a recent project to assess whether randomisation could be helpful (Fang & Casadevall, 2016 ; researchonresearch.org/experimental-funder). Peer review, triage, and deliberative committees are common, but not universal, components (Meadmore et al., 2020 ) and sources of variation include whether non-academic stakeholders are included within peer review teams (Luo et al., 2021 ), whether one or two stage submissions are required (Gross & Bergstrom, 2019 ) and whether sandpits are used (Meadmore et al., 2020 ). Although each procedure may be unique in personnel and fine details, broad information about it would be particularly helpful in comparisons between funders or schemes.

What were the characteristics of the research team?

The characteristics of successful proposals or applicants are relevant to analyses of competitive calls (Grimpe, 2012 ), although there are too many to list individually. Some deserve some attention here.

What are the characteristics of the research team behind the project or output (e.g., gender, age, career status, institution)?

What is the track record of the research team (e.g., citations, publications, awards, previous grants, service work).

Gender bias is an important consideration and whether it plays a role is highly disputed in the literature. Recent findings suggest that there is gender bias in reviews, but not success rates (Bol et al., 2022 ; Van den Besselaar & Mom, 2021 ). Some funding schemes have team requirements (e.g., established vs. early career researcher grants) and many evaluate applicants’ track records. Applicants’ previous achievements may be critical to success for some calls, such as those for established researchers or funding for leadership, play a minor role in others, or be completely ignored (e.g., for double blind grant reviewing). In any case, research team characteristics may be important for evaluating the influence of the funding or the fairness of the selection procedure.

What were the funder’s goals?

Funding streams or sources often have goals that influence what type of research can be funded. Moreover, researchers can be expected to modify their aspirations to align with the funding stream. The funder may have different types of goal, from supporting aspects of the research process to supporting relevant projects or completing a specific task (e.g., Woodward & Clifton, 1994 ), to generating societal benefits (Fernández-del-Castillo et al., 2015 ).

A common distinction is between basic and applied research, and the category “strategic research” has also been used to capture basic research aiming at long term societal benefits (Sandström, 2009 ). The Frascati Manual uses Basic Research, Applied Research and Experimental Development instead (OECD, 2015 ), but this is more relevant for analyses that incorporate industrial research and development.