Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

10 things we know about race and policing in the U.S.

Days of protests across the United States in the wake of George Floyd’s death in the custody of Minneapolis police have brought new attention to questions about police officers’ attitudes toward black Americans, protesters and others. The public’s views of the police, in turn, are also in the spotlight. Here’s a roundup of Pew Research Center survey findings from the past few years about the intersection of race and law enforcement.

How we did this

Most of the findings in this post were drawn from two previous Pew Research Center reports: one on police officers and policing issues published in January 2017, and one on the state of race relations in the United States published in April 2019. We also drew from a September 2016 report on how black and white Americans view police in their communities. (The questions asked for these reports, as well as their responses, can be found in the reports’ accompanying “topline” file or files.)

The 2017 police report was based on two surveys. One was of 7,917 law enforcement officers from 54 police and sheriff’s departments across the U.S., designed and weighted to represent the population of officers who work in agencies that employ at least 100 full-time sworn law enforcement officers with general arrest powers, and conducted between May and August 2016. The other survey, of the general public, was conducted via the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP) in August and September 2016 among 4,538 respondents. (The 2016 report on how blacks and whites view police in their communities also was based on that survey.) More information on methodology is available here .

The 2019 race report was based on a survey conducted in January and February 2019. A total of 6,637 people responded, out of 9,402 who were sampled, for a response rate of 71%. The respondents included 5,599 from the ATP and oversamples of 530 non-Hispanic black and 508 Hispanic respondents sampled from Ipsos’ KnowledgePanel. More information on methodology is available here .

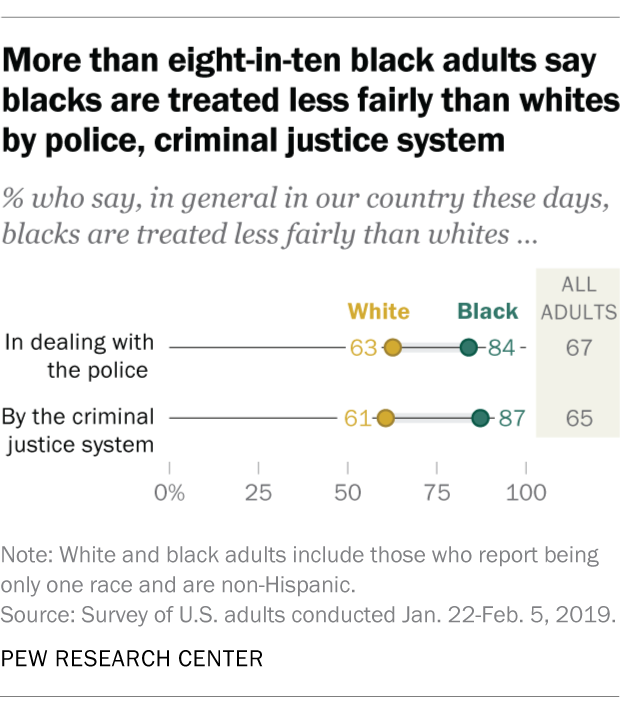

Majorities of both black and white Americans say black people are treated less fairly than whites in dealing with the police and by the criminal justice system as a whole. In a 2019 Center survey , 84% of black adults said that, in dealing with police, blacks are generally treated less fairly than whites; 63% of whites said the same. Similarly, 87% of blacks and 61% of whites said the U.S. criminal justice system treats black people less fairly.

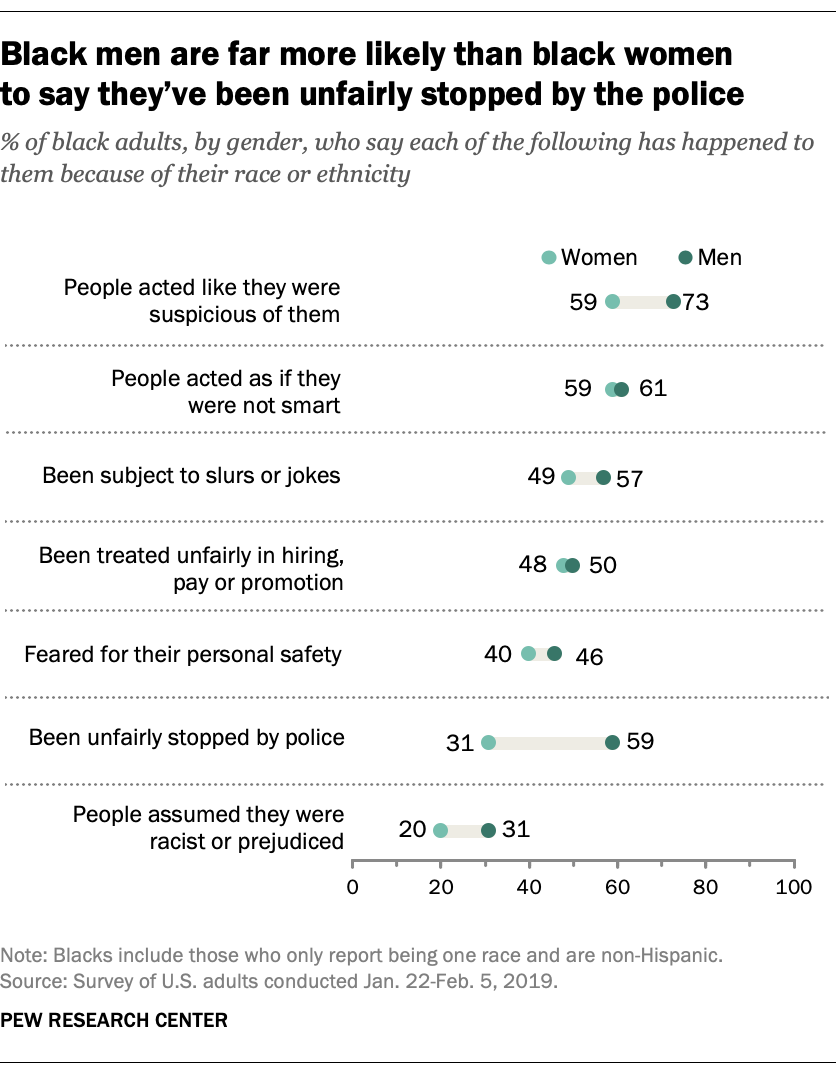

Black adults are about five times as likely as whites to say they’ve been unfairly stopped by police because of their race or ethnicity (44% vs. 9%), according to the same survey. Black men are especially likely to say this : 59% say they’ve been unfairly stopped, versus 31% of black women.

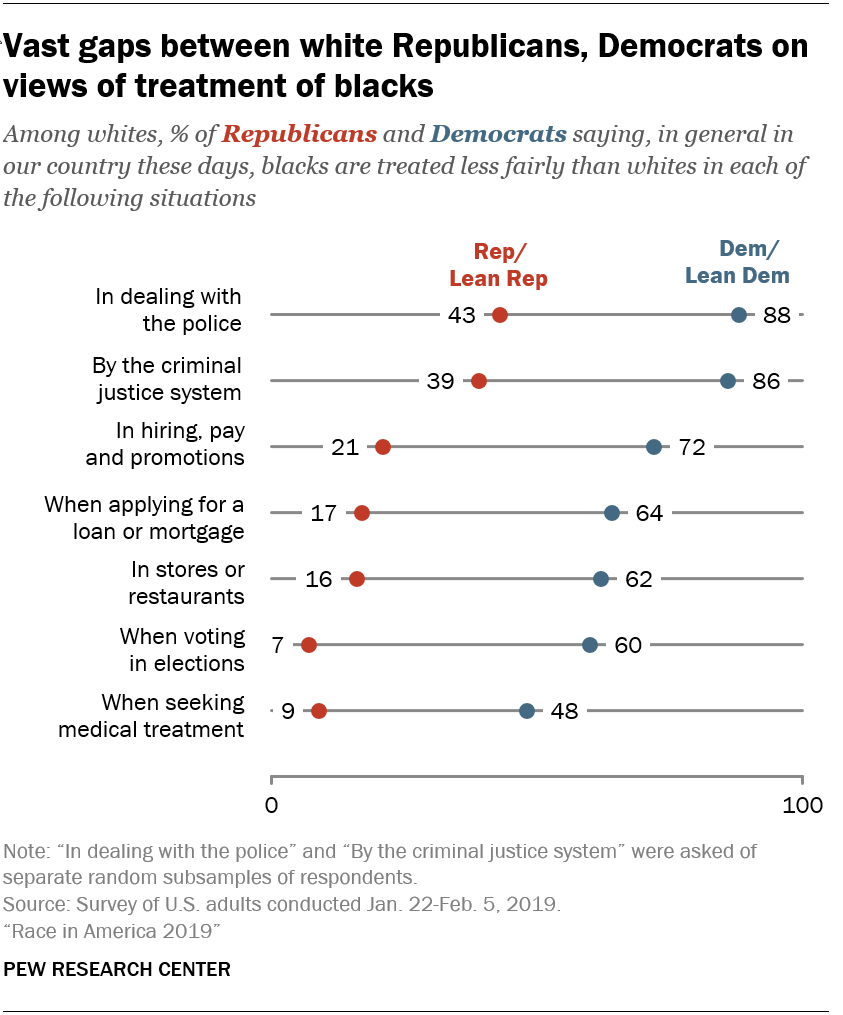

White Democrats and white Republicans have vastly different views of how black people are treated by police and the wider justice system. Overwhelming majorities of white Democrats say black people are treated less fairly than whites by the police (88%) and the criminal justice system (86%), according to the 2019 poll. About four-in-ten white Republicans agree (43% and 39%, respectively).

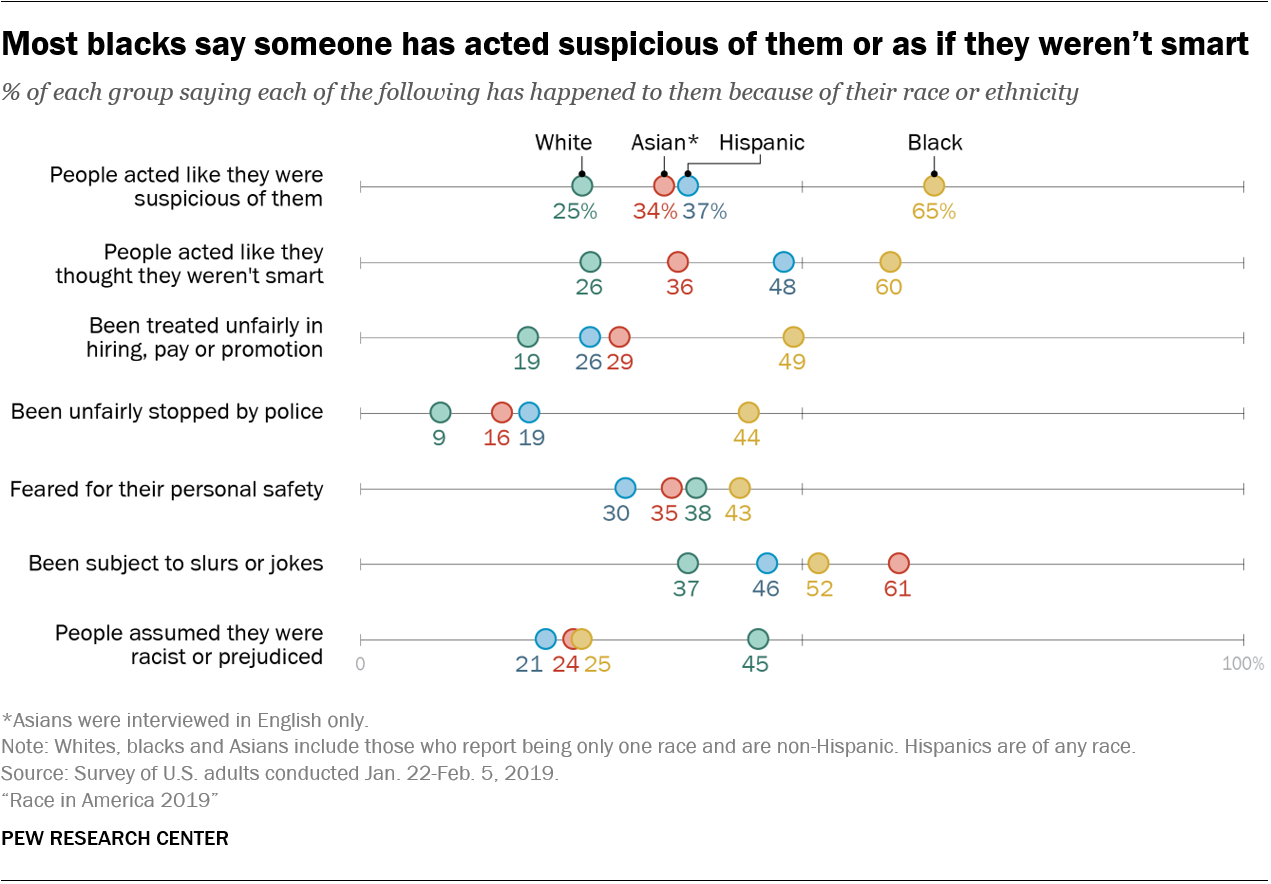

Nearly two-thirds of black adults (65%) say they’ve been in situations where people acted as if they were suspicious of them because of their race or ethnicity, while only a quarter of white adults say that’s happened to them. Roughly a third of both Asian and Hispanic adults (34% and 37%, respectively) say they’ve been in such situations, the 2019 survey found.

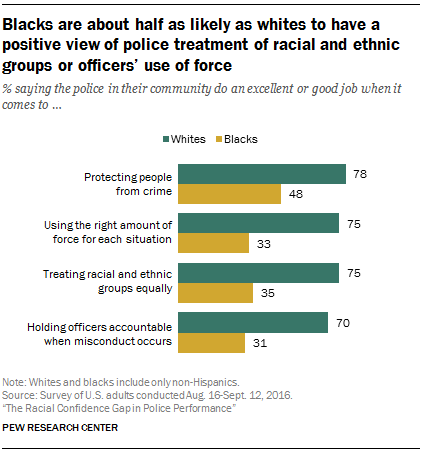

Black Americans are far less likely than whites to give police high marks for the way they do their jobs . In a 2016 survey, only about a third of black adults said that police in their community did an “excellent” or “good” job in using the right amount of force (33%, compared with 75% of whites), treating racial and ethnic groups equally (35% vs. 75%), and holding officers accountable for misconduct (31% vs. 70%).

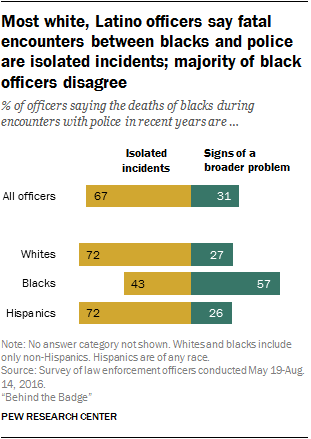

In the past, police officers and the general public have tended to view fatal encounters between black people and police very differently. In a 2016 survey of nearly 8,000 policemen and women from departments with at least 100 officers, two-thirds said most such encounters are isolated incidents and not signs of broader problems between police and the black community. In a companion survey of more than 4,500 U.S. adults, 60% of the public called such incidents signs of broader problems between police and black people. But the views given by police themselves were sharply differentiated by race: A majority of black officers (57%) said that such incidents were evidence of a broader problem, but only 27% of white officers and 26% of Hispanic officers said so.

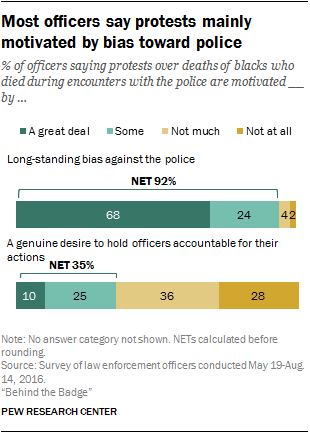

Around two-thirds of police officers (68%) said in 2016 that the demonstrations over the deaths of black people during encounters with law enforcement were motivated to a great extent by anti-police bias; only 10% said (in a separate question) that protesters were primarily motivated by a genuine desire to hold police accountable for their actions. Here as elsewhere, police officers’ views differed by race: Only about a quarter of white officers (27%) but around six-in-ten of their black colleagues (57%) said such protests were motivated at least to some extent by a genuine desire to hold police accountable.

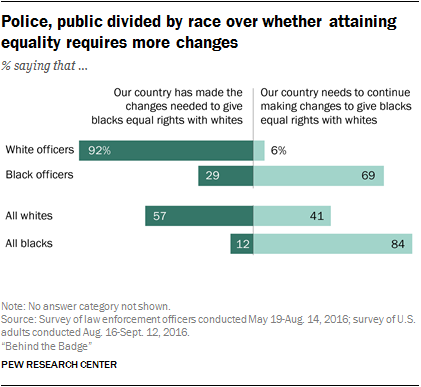

White police officers and their black colleagues have starkly different views on fundamental questions regarding the situation of blacks in American society, the 2016 survey found. For example, nearly all white officers (92%) – but only 29% of their black colleagues – said the U.S. had made the changes needed to assure equal rights for blacks.

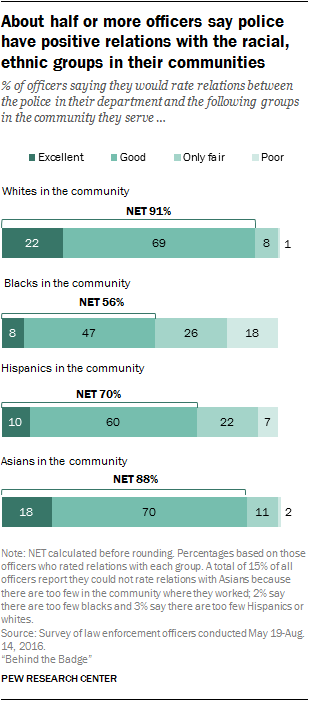

A majority of officers said in 2016 that relations between the police in their department and black people in the community they serve were “excellent” (8%) or “good” (47%). However, far higher shares saw excellent or good community relations with whites (91%), Asians (88%) and Hispanics (70%). About a quarter of police officers (26%) said relations between police and black people in their community were “only fair,” while nearly one-in-five (18%) said they were “poor” – with black officers far more likely than others to say so. (These percentages are based on only those officers who offered a rating.)

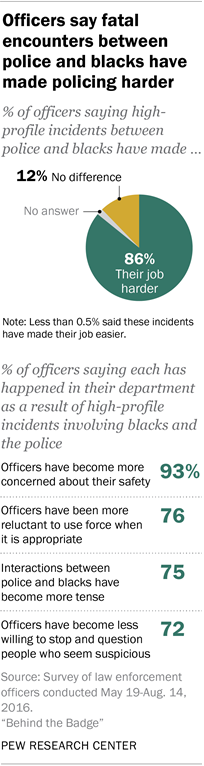

An overwhelming majority of police officers (86%) said in 2016 that high-profile fatal encounters between black people and police officers had made their jobs harder . Sizable majorities also said such incidents had made their colleagues more worried about safety (93%), heightened tensions between police and blacks (75%), and left many officers reluctant to use force when appropriate (76%) or to question people who seemed suspicious (72%).

- Criminal Justice

- Discrimination & Prejudice

- Racial Bias & Discrimination

Drew DeSilver is a senior writer at Pew Research Center .

Michael Lipka is an associate director focusing on news and information research at Pew Research Center .

Dalia Fahmy is a senior writer/editor focusing on religion at Pew Research Center .

What the data says about crime in the U.S.

Fewer than 1% of federal criminal defendants were acquitted in 2022, before release of video showing tyre nichols’ beating, public views of police conduct had improved modestly, black americans differ from other u.s. adults over whether individual or structural racism is a bigger problem, violent crime is a key midterm voting issue, but what does the data say, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Footnote leads to exploration of start of for-profit prisons in N.Y.

Should NATO step up role in Russia-Ukraine war?

It’s on Facebook, and it’s complicated

Protesters take a knee in front of New York City police officers during a solidarity rally for George Floyd, June 4, 2020.

AP Photo/Frank Franklin II

Solving racial disparities in policing

Colleen Walsh

Harvard Staff Writer

Experts say approach must be comprehensive as roots are embedded in culture

“ Unequal ” is a multipart series highlighting the work of Harvard faculty, staff, students, alumni, and researchers on issues of race and inequality across the U.S. The first part explores the experience of people of color with the criminal justice legal system in America.

It seems there’s no end to them. They are the recent videos and reports of Black and brown people beaten or killed by law enforcement officers, and they have fueled a national outcry over the disproportionate use of excessive, and often lethal, force against people of color, and galvanized demands for police reform.

This is not the first time in recent decades that high-profile police violence — from the 1991 beating of Rodney King to the fatal shooting of Michael Brown in 2014 — ignited calls for change. But this time appears different. The police killings of Breonna Taylor in March, George Floyd in May, and a string of others triggered historic, widespread marches and rallies across the nation, from small towns to major cities, drawing protesters of unprecedented diversity in race, gender, and age.

According to historians and other scholars, the problem is embedded in the story of the nation and its culture. Rooted in slavery, racial disparities in policing and police violence, they say, are sustained by systemic exclusion and discrimination, and fueled by implicit and explicit bias. Any solution clearly will require myriad new approaches to law enforcement, courts, and community involvement, and comprehensive social change driven from the bottom up and the top down.

While police reform has become a major focus, the current moment of national reckoning has widened the lens on systemic racism for many Americans. The range of issues, though less familiar to some, is well known to scholars and activists. Across Harvard, for instance, faculty members have long explored the ways inequality permeates every aspect of American life. Their research and scholarship sits at the heart of a new Gazette series starting today aimed at finding ways forward in the areas of democracy; wealth and opportunity; environment and health; and education. It begins with this first on policing.

Harvard Kennedy School Professor Khalil Gibran Muhammad traces the history of policing in America to “slave patrols” in the antebellum South, in which white citizens were expected to help supervise the movements of enslaved Black people.

Photo by Martha Stewart

The history of racialized policing

Like many scholars, Khalil Gibran Muhammad , professor of history, race, and public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School , traces the history of policing in America to “slave patrols” in the antebellum South, in which white citizens were expected to help supervise the movements of enslaved Black people. This legacy, he believes, can still be seen in policing today. “The surveillance, the deputization essentially of all white men to be police officers or, in this case, slave patrollers, and then to dispense corporal punishment on the scene are all baked in from the very beginning,” he told NPR last year.

Slave patrols, and the slave codes they enforced, ended after the Civil War and the passage of the 13th amendment, which formally ended slavery “except as a punishment for crime.” But Muhammad notes that former Confederate states quickly used that exception to justify new restrictions. Known as the Black codes, the various rules limited the kinds of jobs African Americans could hold, their rights to buy and own property, and even their movements.

“The genius of the former Confederate states was to say, ‘Oh, well, if all we need to do is make them criminals and they can be put back in slavery, well, then that’s what we’ll do.’ And that’s exactly what the Black codes set out to do. The Black codes, for all intents and purposes, criminalized every form of African American freedom and mobility, political power, economic power, except the one thing it didn’t criminalize was the right to work for a white man on a white man’s terms.” In particular, he said the Ku Klux Klan “took about the business of terrorizing, policing, surveilling, and controlling Black people. … The Klan totally dominates the machinery of justice in the South.”

When, during what became known as the Great Migration, millions of African Americans fled the still largely agrarian South for opportunities in the thriving manufacturing centers of the North, they discovered that metropolitan police departments tended to enforce the law along racial and ethnic lines, with newcomers overseen by those who came before. “There was an early emphasis on people whose status was just a tiny notch better than the folks whom they were focused on policing,” Muhammad said. “And so the Anglo-Saxons are policing the Irish or the Germans are policing the Irish. The Irish are policing the Poles.” And then arrived a wave of Black Southerners looking for a better life.

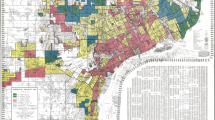

In his groundbreaking work, “ The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America ,” Muhammad argues that an essential turning point came in the early 1900s amid efforts to professionalize police forces across the nation, in part by using crime statistics to guide law enforcement efforts. For the first time, Americans with European roots were grouped into one broad category, white, and set apart from the other category, Black.

Citing Muhammad’s research, Harvard historian Jill Lepore has summarized the consequences this way : “Police patrolled Black neighborhoods and arrested Black people disproportionately; prosecutors indicted Black people disproportionately; juries found Black people guilty disproportionately; judges gave Black people disproportionately long sentences; and, then, after all this, social scientists, observing the number of Black people in jail, decided that, as a matter of biology, Black people were disproportionately inclined to criminality.”

“History shows that crime data was never objective in any meaningful sense,” Muhammad wrote. Instead, crime statistics were “weaponized” to justify racial profiling, police brutality, and ever more policing of Black people.

This phenomenon, he believes, has continued well into this century and is exemplified by William J. Bratton, one of the most famous police leaders in recent America history. Known as “America’s Top Cop,” Bratton led police departments in his native Boston, Los Angeles, and twice in New York, finally retiring in 2016.

Bratton rejected notions that crime was a result of social and economic forces, such as poverty, unemployment, police practices, and racism. Instead, he said in a 2017 speech, “It is about behavior.” Through most of his career, he was a proponent of statistically-based “predictive” policing — essentially placing forces in areas where crime numbers were highest, focused on the groups found there.

Bratton argued that the technology eliminated the problem of prejudice in policing, without ever questioning potential bias in the data or algorithms themselves — a significant issue given the fact that Black Americans are arrested and convicted of crimes at disproportionately higher rates than whites. This approach has led to widely discredited practices such as racial profiling and “stop-and-frisk.” And, Muhammad notes, “There is no research consensus on whether or how much violence dropped in cities due to policing.”

Gathering numbers

In 2015 The Washington Post began tracking every fatal shooting by an on-duty officer, using news stories, social media posts, and police reports in the wake of the fatal police shooting of Brown, a Black teenager in Ferguson, Mo. According to the newspaper, Black Americans are killed by police at twice the rate of white Americans, and Hispanic Americans are also killed by police at a disproportionate rate.

Such efforts have proved useful for researchers such as economist Rajiv Sethi .

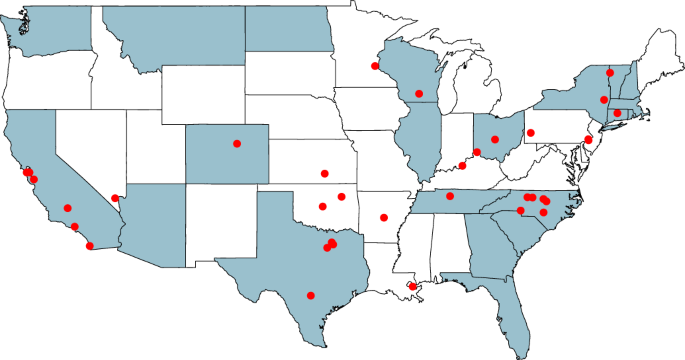

A Joy Foundation Fellow at the Harvard Radcliffe Institute , Sethi is investigating the use of lethal force by law enforcement officers, a difficult task given that data from such encounters is largely unavailable from police departments. Instead, Sethi and his team of researchers have turned to information collected by websites and news organizations including The Washington Post and The Guardian, merged with data from other sources such as the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the Census, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A Joy Foundation Fellow at the Harvard Radcliffe Institute, Rajiv Sethi is investigating the use of lethal force by law enforcement officers,

Courtesy photo

They have found that exposure to deadly force is highest in the Mountain West and Pacific regions relative to the mid-Atlantic and northeastern states, and that racial disparities in relation to deadly force are even greater than the national numbers imply. “In the country as a whole, you’re about two to three times more likely to face deadly force if you’re Black than if you are white” said Sethi. “But if you look at individual cities separately, disparities in exposure are much higher.”

Examining the characteristics associated with police departments that experience high numbers of lethal encounters is one way to better understand and address racial disparities in policing and the use of violence, Sethi said, but it’s a massive undertaking given the decentralized nature of policing in America. There are roughly 18,000 police departments in the country, and more than 3,000 sheriff’s offices, each with its own approaches to training and selection.

“They behave in very different ways, and what we’re finding in our current research is that they are very different in the degree to which they use deadly force,” said Sethi. To make real change, “You really need to focus on the agency level where organizational culture lies, where selection and training protocols have an effect, and where leadership can make a difference.”

Sethi pointed to the example of Camden, N.J., which disbanded and replaced its police force in 2013, initially in response to a budget crisis, but eventually resulting in an effort to fundamentally change the way the police engaged with the community. While there have been improvements, including greater witness cooperation, lower crime, and fewer abuse complaints, the Camden case doesn’t fit any particular narrative, said Sethi, noting that the number of officers actually increased as part of the reform. While the city is still faced with its share of problems, Sethi called its efforts to rethink policing “important models from which we can learn.”

Fighting vs. preventing crime

For many analysts, the real problem with policing in America is the fact that there is simply too much of it. “We’ve seen since the mid-1970s a dramatic increase in expenditures that are associated with expanding the criminal legal system, including personnel and the tasks we ask police to do,” said Sandra Susan Smith , Daniel and Florence Guggenheim Professor of Criminal Justice at HKS, and the Carol K. Pforzheimer Professor at the Radcliffe Institute. “And at the same time we see dramatic declines in resources devoted to social welfare programs.”

“You can have all the armored personnel carriers you want in Ferguson, but public safety is more likely to come from redressing environmental pollution, poor education, and unfair work,” said Brandon Terry, assistant professor of African and African American Studies and social studies.

Kris Snibble/Harvard file photo

Smith’s comment highlights a key argument embraced by many activists and experts calling for dramatic police reform: diverting resources from the police to better support community services including health care, housing, and education, and stronger economic and job opportunities. They argue that broader support for such measures will decrease the need for policing, and in turn reduce violent confrontations, particularly in over-policed, economically disadvantaged communities, and communities of color.

For Brandon Terry , that tension took the form of an ice container during his Baltimore high school chemistry final. The frozen cubes were placed in the middle of the classroom to help keep the students cool as a heat wave sent temperatures soaring. “That was their solution to the building’s lack of air conditioning,” said Terry, a Harvard assistant professor of African and African American Studies and social studies. “Just grab an ice cube.”

Terry’s story is the kind many researchers cite to show the negative impact of underinvesting in children who will make up the future population, and instead devoting resources toward policing tactics that embrace armored vehicles, automatic weapons, and spy planes. Terry’s is also the kind of tale promoted by activists eager to defund the police, a movement begun in the late 1960s that has again gained momentum as the death toll from violent encounters mounts. A scholar of Martin Luther King Jr., Terry said the Civil Rights leader’s views on the Vietnam War are echoed in the calls of activists today who are pressing to redistribute police resources.

“King thought that the idea of spending many orders of magnitude more for an unjust war than we did for the abolition of poverty and the abolition of ghettoization was a moral travesty, and it reflected a kind of sickness at the core of our society,” said Terry. “And part of what the defund model is based upon is a similar moral criticism, that these budgets reflect priorities that we have, and our priorities are broken.”

Terry also thinks the policing debate needs to be expanded to embrace a fuller understanding of what it means for people to feel truly safe in their communities. He highlights the work of sociologist Chris Muller and Harvard’s Robert Sampson, who have studied racial disparities in exposures to lead and the connections between a child’s early exposure to the toxic metal and antisocial behavior. Various studies have shown that lead exposure in children can contribute to cognitive impairment and behavioral problems, including heightened aggression.

“You can have all the armored personnel carriers you want in Ferguson,” said Terry, “but public safety is more likely to come from redressing environmental pollution, poor education, and unfair work.”

Policing and criminal justice system

Alexandra Natapoff , Lee S. Kreindler Professor of Law, sees policing as inexorably linked to the country’s criminal justice system and its long ties to racism.

“Policing does not stand alone or apart from how we charge people with crimes, or how we convict them, or how we treat them once they’ve been convicted,” she said. “That entire bundle of official practices is a central part of how we govern, and in particular, how we have historically governed Black people and other people of color, and economically and socially disadvantaged populations.”

Unpacking such a complicated issue requires voices from a variety of different backgrounds, experiences, and fields of expertise who can shine light on the problem and possible solutions, said Natapoff, who co-founded a new lecture series with HLS Professor Andrew Crespo titled “ Policing in America .”

In recent weeks the pair have hosted Zoom discussions on topics ranging from qualified immunity to the Black Lives Matter movement to police unions to the broad contours of the American penal system. The series reflects the important work being done around the country, said Natapoff, and offers people the chance to further “engage in dialogue over these over these rich, complicated, controversial issues around race and policing, and governance and democracy.”

Courts and mass incarceration

Much of Natapoff’s recent work emphasizes the hidden dangers of the nation’s misdemeanor system. In her book “ Punishment Without Crime: How Our Massive Misdemeanor System Traps the Innocent and Makes America More Unequal ,” Natapoff shows how the practice of stopping, arresting, and charging people with low-level offenses often sends them down a devastating path.

“This is how most people encounter the criminal apparatus, and it’s the first step of mass incarceration, the initial net that sweeps people of color disproportionately into the criminal system,” said Natapoff. “It is also the locus that overexposes Black people to police violence. The implications of this enormous net of police and prosecutorial authority around minor conduct is central to understanding many of the worst dysfunctions of our criminal system.”

One consequence is that Black and brown people are incarcerated at much higher rates than white people. America has approximately 2.3 million people in federal, state, and local prisons and jails, according to a 2020 report from the nonprofit the Prison Policy Initiative. According to a 2018 report from the Sentencing Project, Black men are 5.9 times as likely to be incarcerated as white men and Hispanic men are 3.1 times as likely.

Reducing mass incarceration requires shrinking the misdemeanor net “along all of its axes” said Natapoff, who supports a range of reforms including training police officers to both confront and arrest people less for low-level offenses, and the policies of forward-thinking prosecutors willing to “charge fewer of those offenses when police do make arrests.”

She praises the efforts of Suffolk County District Attorney Rachael Rollins in Massachusetts and George Gascón, the district attorney in Los Angeles County, Calif., who have pledged to stop prosecuting a range of misdemeanor crimes such as resisting arrest, loitering, trespassing, and drug possession. “If cities and towns across the country committed to that kind of reform, that would be a profoundly meaningful change,” said Natapoff, “and it would be a big step toward shrinking our entire criminal apparatus.”

Retired U.S. Judge Nancy Gertner cites the need to reform federal sentencing guidelines, arguing that all too often they have been proven to be biased and to result in packing the nation’s jails and prisons.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

Sentencing reform

Another contributing factor in mass incarceration is sentencing disparities.

A recent Harvard Law School study found that, as is true nationally, people of color are “drastically overrepresented in Massachusetts state prisons.” But the report also noted that Black and Latinx people were less likely to have their cases resolved through pretrial probation — a way to dismiss charges if the accused meet certain conditions — and receive much longer sentences than their white counterparts.

Retired U.S. Judge Nancy Gertner also notes the need to reform federal sentencing guidelines, arguing that all too often they have been proven to be biased and to result in packing the nation’s jails and prisons. She points to the way the 1994 Crime Bill (legislation sponsored by then-Sen. Joe Biden of Delaware) ushered in much harsher drug penalties for crack than for powder cocaine. This tied the hands of judges issuing sentences and disproportionately punished people of color in the process. “The disparity in the treatment of crack and cocaine really was backed up by anecdote and stereotype, not by data,” said Gertner, a lecturer at HLS. “There was no data suggesting that crack was infinitely more dangerous than cocaine. It was the young Black predator narrative.”

The First Step Act, a bipartisan prison reform bill aimed at reducing racial disparities in drug sentencing and signed into law by President Donald Trump in 2018, is just what its name implies, said Gertner.

“It reduces sentences to the merely inhumane rather than the grotesque. We still throw people in jail more than anybody else. We still resort to imprisonment, rather than thinking of other alternatives. We still resort to punishment rather than other models. None of that has really changed. I don’t deny the significance of somebody getting out of prison a year or two early, but no one should think that that’s reform.”

Not just bad apples

Reform has long been a goal for federal leaders. Many heralded Obama-era changes aimed at eliminating racial disparities in policing and outlined in the report by The President’s Task Force on 21st Century policing. But HKS’s Smith saw them as largely symbolic. “It’s a nod to reform. But most of the reforms that are implemented in this country tend to be reforms that nibble around the edges and don’t really make much of a difference.”

Efforts such as diversifying police forces and implicit bias training do little to change behaviors and reduce violent conduct against people of color, said Smith, who cites studies suggesting a majority of Americans hold negative biases against Black and brown people, and that unconscious prejudices and stereotypes are difficult to erase.

“Experiments show that you can, in the context of a day, get people to think about race differently, and maybe even behave differently. But if you follow up, say, a week, or two weeks later, those effects are gone. We don’t know how to produce effects that are long-lasting. We invest huge amounts to implement such police reforms, but most often there’s no empirical evidence to support their efficacy.”

Even the early studies around the effectiveness of body cameras suggest the devices do little to change “officers’ patterns of behavior,” said Smith, though she cautions that researchers are still in the early stages of collecting and analyzing the data.

And though police body cameras have caught officers in unjust violence, much of the general public views the problem as anomalous.

“Despite what many people in low-income communities of color think about police officers, the broader society has a lot of respect for police and thinks if you just get rid of the bad apples, everything will be fine,” Smith added. “The problem, of course, is this is not just an issue of bad apples.”

Efforts such as diversifying police forces and implicit bias training do little to change behaviors and reduce violent conduct against people of color, said Sandra Susan Smith, a professor of criminal justice Harvard Kennedy School.

Community-based ways forward

Still Smith sees reason for hope and possible ways forward involving a range of community-based approaches. As part of the effort to explore meaningful change, Smith, along with Christopher Winship , Diker-Tishman Professor of Sociology at Harvard University and a member of the senior faculty at HKS, have organized “ Reimagining Community Safety: A Program in Criminal Justice Speaker Series ” to better understand the perspectives of practitioners, policymakers, community leaders, activists, and academics engaged in public safety reform.

Some community-based safety models have yielded important results. Smith singles out the Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets program (known as CAHOOTS ) in Eugene, Ore., which supplements police with a community-based public safety program. When callers dial 911 they are often diverted to teams of workers trained in crisis resolution, mental health, and emergency medicine, who are better equipped to handle non-life-threatening situations. The numbers support her case. In 2017 the program received 25,000 calls, only 250 of which required police assistance. Training similar teams of specialists who don’t carry weapons to handle all traffic stops could go a long way toward ending violent police encounters, she said.

“Imagine you have those kinds of services in play,” said Smith, paired with community-based anti-violence program such as Cure Violence , which aims to stop violence in targeted neighborhoods by using approaches health experts take to control disease, such as identifying and treating individuals and changing social norms. Together, she said, these programs “could make a huge difference.”

At Harvard Law School, students have been studying how an alternate 911-response team might function in Boston. “We were trying to move from thinking about a 911-response system as an opportunity to intervene in an acute moment, to thinking about what it would look like to have a system that is trying to help reweave some of the threads of community, a system that is more focused on healing than just on stopping harm” said HLS Professor Rachel Viscomi, who directs the Harvard Negotiation and Mediation Clinical Program and oversaw the research.

The forthcoming report, compiled by two students in the HLS clinic, Billy Roberts and Anna Vande Velde, will offer officials a range of ideas for how to think about community safety that builds on existing efforts in Boston and other cities, said Viscomi.

But Smith, like others, knows community-based interventions are only part of the solution. She applauds the Justice Department’s investigation into the Ferguson Police Department after the shooting of Brown. The 102-page report shed light on the department’s discriminatory policing practices, including the ways police disproportionately targeted Black residents for tickets and fines to help balance the city’s budget. To fix such entrenched problems, state governments need to rethink their spending priorities and tax systems so they can provide cities and towns the financial support they need to remain debt-free, said Smith.

Rethinking the 911-response system to being one that is “more focused on healing than just on stopping harm” is part of the student-led research under the direction of Law School Professor Rachel Viscomi, who heads up the Harvard Negotiation and Mediation Clinical Program.

Jon Chase/Harvard file photo

“Part of the solution has to be a discussion about how government is funded and how a city like Ferguson got to a place where government had so few resources that they resorted to extortion of their residents, in particular residents of color, in order to make ends meet,” she said. “We’ve learned since that Ferguson is hardly the only municipality that has struggled with funding issues and sought to address them through the oppression and repression of their politically, socially, and economically marginalized Black and Latino residents.”

Police contracts, she said, also need to be reexamined. The daughter of a “union man,” Smith said she firmly supports officers’ rights to union representation to secure fair wages, health care, and safe working conditions. But the power unions hold to structure police contracts in ways that protect officers from being disciplined for “illegal and unethical behavior” needs to be challenged, she said.

“I think it’s incredibly important for individuals to be held accountable and for those institutions in which they are embedded to hold them to account. But we routinely find that union contracts buffer individual officers from having to be accountable. We see this at the level of the Supreme Court as well, whose rulings around qualified immunity have protected law enforcement from civil suits. That needs to change.”

Other Harvard experts agree. In an opinion piece in The Boston Globe last June, Tomiko Brown-Nagin , dean of the Harvard Radcliffe Institute and the Daniel P.S. Paul Professor of Constitutional Law at HLS, pointed out the Court’s “expansive interpretation of qualified immunity” and called for reform that would “promote accountability.”

“This nation is devoted to freedom, to combating racial discrimination, and to making government accountable to the people,” wrote Brown-Nagin. “Legislators today, like those who passed landmark Civil Rights legislation more than 50 years ago, must take a stand for equal justice under law. Shielding police misconduct offends our fundamental values and cannot be tolerated.”

Share this article

You might like.

Historian traces 19th-century murder case that brought together historical figures, helped shape American thinking on race, violence, incarceration

National security analysts outline stakes ahead of July summit

‘Spermworld’ documentary examines motivations of prospective parents, volunteer donors who connect through private group page

Epic science inside a cubic millimeter of brain

Researchers publish largest-ever dataset of neural connections

Pop star on one continent, college student on another

Model and musician Kazuma Mitchell managed to (mostly) avoid the spotlight while at Harvard

Finding right mix on campus speech policies

Legal, political scholars discuss balancing personal safety, constitutional rights, academic freedom amid roiling protests, cultural shifts

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

17 Racial Profiling

Robin S. Engel, School of Criminal Justice, University of Cincinnati

Derek Cohen is a Doctoral Student at the University of Cincinnati.

- Published: 01 April 2014

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The use of the term “racial profiling” gained popularity in the mid-1990s and originally referred to the reliance on race as an explicit criterion in “profiles” of offenders that some police organizations issued to guide police officer decision making. This essay traces the evolution of racial profiling, both in terms of terminology and police practice, from the “War on Drugs” in the 1980s to present day. The essay highlights changes in policies, legislation, litigation, and data collection across the country as mechanisms to control the use of racial profiling, particularly in terms of stops and stop outcomes (e.g., citations, arrests, searches, and seizures). It also critiques the research methods and statistical analyses often used by researchers who conduct studies of the prevalence, causes, and consequences of racially biased policing. The essay concludes by issuing a new call to action for future research in the area of racial profiling. Rather than seeking incremental improvements in data collection and methodology, this essay argues for a fundamental reconceptualization of research on race and policing.

T he history of race and policing in the United States is long and troubled. For centuries, the police in America were used as instruments of the state to enforce discriminatory laws and uphold the status quo of the time ( Richardson 1974 ; Monkonen 1981). The discriminatory treatment by police of minorities—and blacks in particular—was reflective of a socially unjust and biased society ( Kerner Commission 1968 ). While the systematic targeting and biased treatment endured by minorities at the hands of American police has been well documented ( Williams and Murphy 1990 ), significant progress has been made in the last several decades toward equity and legitimacy in American policing ( Walker 2003 ; Warren and Tomaskovic-Devey 2009 ; Bayley and Nixon 2010 ). Nevertheless, the legacy that this troubled past brings to modern policing bears repeating. A current concern in American society remains the use of race or ethnicity by police as reason for some form of coercive action. This police practice—often referred to as racial profiling—is widely recognized by politicians, the public, and even the police themselves as inherently problematic. Yet reducing this problem to a single term—racial profiling—simultaneously reduces the nuances surrounding the multifaceted and complicated issues regarding police, race, and crime in America.

In this essay, we first begin with a brief historical overview of the ground previously traveled as it relates to policing, race, and research. In our discussion, we note the historical application of racially-biased police practices as a result of policies arising from the “War on Drugs” in the 1980s. Thereafter we describe the use and definition of the term “racial profiling” and trace the resulting changes in policies, legislation, litigation, and data collection across the country. The changes in data collection in particular resulted in the development of a body of research designed specifically to determine racial/ethnic disparities in police treatment during pedestrian and traffic stops. We summarize this body of research, including a focus on stops and stop outcomes (e.g., citations, arrests, searches, and seizures), and offer a critique of the research methods and statistical analyses often used by researchers. Finally, we issue a new call to action for future research in the area of racial profiling. Rather than seeking incremental improvements in data collection and methodology, we argue for a fundamental reconceptualization of research on race and policing. While we note that this essay is predominately focused on the experiences and research surrounding one racial group (blacks) within one country (United States), it is widely applicable to other minority groups within the United States, as well as minority groups within other countries. Indeed, it seems that the core components of the American story of racial bias, policing, and research is widely generalizable across cultures.

This essay represents a broad examination of racial profiling in the United States, both from historical and contemporary perspectives. Section 17.1 of the essay describes the history of racial profiling, as it was originally developed as a tactic to detect and apprehend drug couriers along the I-95 corridor of the Eastern Seaboard. Section 17.1 also describes the initial efforts to collect data on racial profiling, as well as identifying the evolving definition of the term. Section 17.2 reviews the literature on racially-biased policing starting with the classic ethnographic work that first identified issues related to race and policing; it then examines the more recent empirical evidence on the extent to which racial and ethnic disparities have appeared evident during vehicle and pedestrian stops, citation outcomes, and searches and seizure. Section 17.3 offers a new collective research agenda to help us begin to determine if the observed racial disparities in stops, citations, and searches and seizures amounts to racial/ethnic bias and discrimination. That section also draws some conclusions as to the state of the science on racially-biased policing.

A number of conclusions can be drawn:

Despite large-scale data collection efforts, the extent of racially-biased policing in the United States remains largely unknown

Despite calls from researchers to reform institutional practices, increase accountability and supervision, and engage in better data collection, the evidence regarding the actual impact of such recommendations on racially-biased policing is nearly non-existent.

While many agencies can readily identify racial/ethnic disparities, they often cannot detect bias, and further cannot determine why these disparities exist or how to effectively reduce them.

As police agencies continue to promote and advance practices that have demonstrated effectiveness (e.g., hot spots and other types of focused policing strategies), it is likely that racial/ethnic disparities in stops and stop outcomes will continue or perhaps even increase based on differential offending patterns and saturation patrols in predominately minority areas.

More, and better, research is necessary if we are serious about both the role of science in policing and the need to reduce racial/ethnic bias in policing.

17.1 History of Racial Profiling

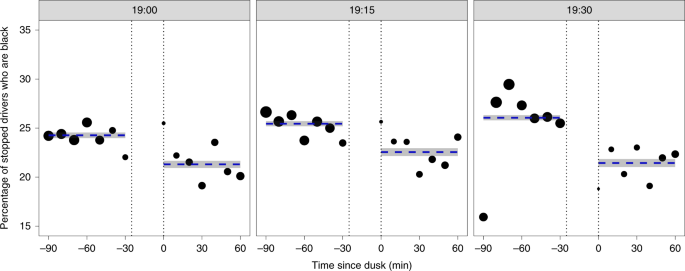

While the troubled history of race and policing in the United States is lengthy and complex, a more recent focus on racial profiling emerged in the last two decades. The use of the term “racial profiling” gained popularity in the mid-1990s and originally referred to the use of race as an explicit criterion in “profiles” of offenders that some police organizations issued to guide police officer decision-making ( Engel, Calnon, and Bernard 2001 ; Harris 2006 ). These profiles were used as part of a larger strategy for the “War on Drugs” from the 1980s and 1990s that led to dramatic changes in criminal justice strategies nationally, including the aggressive targeting of drug offenders at the street level and increased rates of incarceration and sentence length ( Scalia 2001 ; Harris 2006 ; Tonry 2011 ). Racial profiling specifically referred to criminal interdiction practices based on drug-courier profiles that were identified and provided to law enforcement officers through federal, state, and local law enforcement training. As part of police efforts to interdict drug trafficking on the nation’s highways, police agencies developed guidelines or “profiles” to help officers identify characteristics of drug couriers that could be used to target drivers and vehicles. This training sometimes identified subjects’ race and ethnicity as part of a larger “profile” of drug courier activity. The focus of this training was on Interstate highways on the East Coast, particularly around the I-95 corridor that linked Miami, Florida with cities and drug distribution points in the major mid-Atlantic and Northeastern cities ( Harris 1999 ; Engel, Calnon, and Bernard 2002 ). Based on this profile, police would make pretextual stops ( Whren v. U.S. , 517 U.S. 806 [1996]) and attempt to establish a legal basis to search for contraband.

Another police tactic resulting from the “War on Drugs” was the increased use of pedestrian stops, along with stop and frisk tactics ( Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 [1968]) to maximize the number of police-citizen encounters with individuals believed to be involved in criminal behavior. These targeted enforcement strategies were especially felt by young minority males, who were disproportionately subject to police surveillance and imprisonment for drug offenses ( Kennedy 1997 ; Walker 2001 ; Harris 2002 ; Tonry 2011 ). The controversy surrounding the aggressive use of traffic and pedestrian stops by police still exists today ( Fagan 2004 ; Gelman, Fagan, and Kiss 2007 ; Ridgeway and MacDonald 2009 ).

17.1.1 The Rise of Data Collection

High-profile litigation efforts in the states of New Jersey ( New Jersey v. Soto , 734 A.2d 350 [1996]) and Maryland ( Wilkins v. Maryland State Police , MJG 93-468 [1993]) alleging racial profiling by law enforcement agencies brought a discussion of these practices to the forefront of American public debate ( GAO 2000 ; Buerger and Farrell 2002 ; Harris 2002 ). Based on the notoriety and successful litigation involving these claims of racial profiling, the public, media, and politicians began to exert pressure on law enforcement to address perceived racial/ethnic bias, particularly as related to traffic stops ( Walker 2001 ; Barlow and Barlow 2002 ; Novak 2004 ). As a result of this pressure, law enforcement agencies and politicians across the country began erecting policies and legislation designed to “eliminate” racial profiling practices by local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies ( Harris 2002 , 2006 ; Tillyer, Engel, and Wooldredge 2008 ). These policies were often focused on traffic stops and included mandates to collect data regarding driver and passenger demographics from every traffic stop (regardless of disposition). The data collection efforts originally designed to uncover racial/ethnic disparities in vehicle stops were initiated by litigation, legislative mandate, and proactive action by law enforcement agencies to address community concerns ( Ramirez, McDevitt, and Farrell 2000 ; Davis 2001 ; Davis, Gillis, and Foster 2001 ; Tillyer, Engel, and Cherkauskas 2010 ). As noted by Tillyer et al. (2010) , by 2009, thirty-nine states had passed some form of legislation regarding racial profiling. Specifically, eleven states enacted legislation that prohibited racial profiling, five states mandated traffic-stop data collection, and twelve states both prohibited racial profiling and mandated data collection, while eight states had bills under consideration and three states had other forms of racial profiling policies.

The heavy focus on data collection during traffic stops was based in part on the original definition of racial profiling, but also because of the recognition that traffic stops are the most frequently occurring type of police-citizen interaction and can be initiated for a wide variety of reasons including legal violations, departmental policy requirements, and officer discretion ( Skolnick 1966 ; Walker 2001 ; Meehan and Ponder 2002 ; Alpert, MacDonald, and Dunham 2005 ). Analyses of the Police Public Contact Survey demonstrate that of the 19 percent of citizens surveyed who reported having some form of contact with police, the majority of these citizens (56 percent) indicated that contact occurred as the result of a traffic stop ( Durose, Schmitt, and Langan 2007 ). In addition, police officers have wide and often unfettered discretion when determining when to initiate traffic stops and the outcomes that motorists receive as a result of those stops ( Wilson 1968 ; Ramirez, McDevitt, and Farrell 2000 ; Lundman and Kaufmann 2003 ; Engel and Calnon 2004b ; Novak 2004 ; Engel 2005 ).

When initial claims of racial profiling during traffic stops were leveled against police, it was clear that law enforcement agencies across the country were poorly prepared to demonstrate, document, or defend their current practices. Quite simply, most law enforcement agencies did not routinely collect information about all motorists who were stopped by police, nor did they collect basic demographic information about those who were stopped (including race/ethnicity) ( Ramirez, McDevitt, and Farrell 2000 ). While many agencies did routinely collect information about citations and arrests, this information could not be compared to the population of all motorists stopped by police that did not result in further official action. Likewise, the population of drivers “eligible” to be stopped for traffic violations was also unknown. Described as the “benchmark” problem, the need to compare traffic stops to those eligible to be stopped created a new stream of research across the country ( Walker 2001 ; Engel and Calnon 2004b ). Unfortunately, as noted in more detail below, over two decades of subsequent research produced very little, as the benchmark problem has never been adequately addressed by the research community.

17.1.2 Defining Racial Profiling

The initial narrow focus on “racial profiling” did not adequately address a much larger issue in American police-community relations. Specifically, claims of inappropriate police targeting of minorities for purposes of enhanced criminal apprehension and punishment have been recognized throughout American history. While the term “racial profiling” referred directly to the specific policies and practices in the 1990s of targeting minorities traveling on interstates for increased scrutiny to obtain drug seizures, concerns of racial bias and illegitimate practices by police have existed for many decades. Therefore, researchers recognized the need to broaden the conversation by calling for examinations of all forms of police bias. A more comprehensive definition allowed policy makers, practitioners, and academics to better focus on issues of racial bias beyond drug profiles during traffic stops.

As noted by Fridell and Scott (2005) the term racial profiling has evolved over time. Despite the rather narrow definition of profiling that began with policing drug trafficking, the growing public consensus became that any and all decisions made by officers based solely or partially on the race of the suspect were considered racial profiling. It was this change from a narrowly defined term of profiling to an all-encompassing term that led Fridell et al. (2001) to first introduce the new term. They argued that some past definitions of profiling may have been too restrictive, focusing exclusively on “sole” reliance on race. They noted that police decision making is rarely based on any sole factor, including race. Furthermore, in focus groups with citizens and police officers, Fridell et al. (2001) noted that citizens defined profiling as encompassing any and all demonstrations of racial bias in policing and viewed it as widespread. On the other hand, for police officers “profiling” connoted only the narrow definition of sole reliance on race; therefore, they viewed it as a much rarer occurrence. The differing definitions of profiling led to defensiveness and frustration as the two groups talked past each other, thus the development of the new term, racially biased policing, which Fridell and her colleagues defined as follows: “Racially biased policing occurs when law enforcement inappropriately considers race or ethnicity in deciding with whom and how to intervene in an enforcement capacity.”

As noted by Engel (2008) , economists and other academics have identified two different types of police racial/ethnic bias: 1) “taste discrimination” or “disparate treatment” and 2) “statistical discrimination” or “disparate impact” ( Becker 1957 ; Arrow 1973 ). The difference between these two concepts is based on the individual intentions of police officers—in the former, racial/ethnic discrimination is the direct result of intentional police bias, while in the later, racial/ethnic discrimination is the result of factors other than individual police bias (i.e., deployment patterns, differences based on deployment patterns, offending behavior, etc.) ( Knowles, Perisco, and Todd 2001 ; Ayres 2002 , 2005 ; Persico and Castleman 2005 ). Accurately measuring and classifying these two general types of police bias, however, have proved difficult for researchers. A summary of the evidence regarding racially biased policing is reviewed below.

17.2 The Evidence