- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

Words to Use in an Essay: 300 Essay Words

Hannah Yang

Table of Contents

Words to use in the essay introduction, words to use in the body of the essay, words to use in your essay conclusion, how to improve your essay writing vocabulary.

It’s not easy to write an academic essay .

Many students struggle to word their arguments in a logical and concise way.

To make matters worse, academic essays need to adhere to a certain level of formality, so we can’t always use the same word choices in essay writing that we would use in daily life.

If you’re struggling to choose the right words for your essay, don’t worry—you’ve come to the right place!

In this article, we’ve compiled a list of over 300 words and phrases to use in the introduction, body, and conclusion of your essay.

The introduction is one of the hardest parts of an essay to write.

You have only one chance to make a first impression, and you want to hook your reader. If the introduction isn’t effective, the reader might not even bother to read the rest of the essay.

That’s why it’s important to be thoughtful and deliberate with the words you choose at the beginning of your essay.

Many students use a quote in the introductory paragraph to establish credibility and set the tone for the rest of the essay.

When you’re referencing another author or speaker, try using some of these phrases:

To use the words of X

According to X

As X states

Example: To use the words of Hillary Clinton, “You cannot have maternal health without reproductive health.”

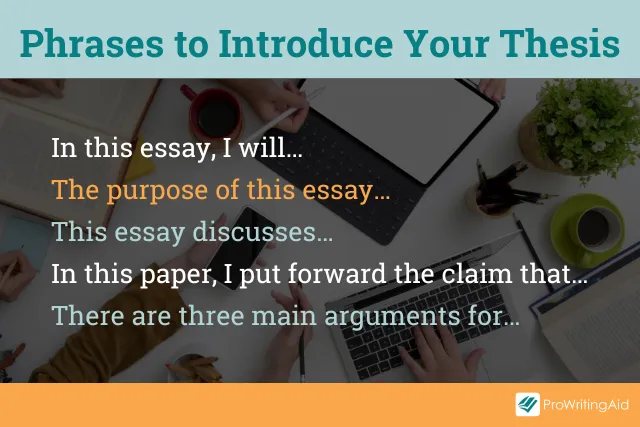

Near the end of the introduction, you should state the thesis to explain the central point of your paper.

If you’re not sure how to introduce your thesis, try using some of these phrases:

In this essay, I will…

The purpose of this essay…

This essay discusses…

In this paper, I put forward the claim that…

There are three main arguments for…

Example: In this essay, I will explain why dress codes in public schools are detrimental to students.

After you’ve stated your thesis, it’s time to start presenting the arguments you’ll use to back up that central idea.

When you’re introducing the first of a series of arguments, you can use the following words:

First and foremost

First of all

To begin with

Example: First , consider the effects that this new social security policy would have on low-income taxpayers.

All these words and phrases will help you create a more successful introduction and convince your audience to read on.

The body of your essay is where you’ll explain your core arguments and present your evidence.

It’s important to choose words and phrases for the body of your essay that will help the reader understand your position and convince them you’ve done your research.

Let’s look at some different types of words and phrases that you can use in the body of your essay, as well as some examples of what these words look like in a sentence.

Transition Words and Phrases

Transitioning from one argument to another is crucial for a good essay.

It’s important to guide your reader from one idea to the next so they don’t get lost or feel like you’re jumping around at random.

Transition phrases and linking words show your reader you’re about to move from one argument to the next, smoothing out their reading experience. They also make your writing look more professional.

The simplest transition involves moving from one idea to a separate one that supports the same overall argument. Try using these phrases when you want to introduce a second correlating idea:

Additionally

In addition

Furthermore

Another key thing to remember

In the same way

Correspondingly

Example: Additionally , public parks increase property value because home buyers prefer houses that are located close to green, open spaces.

Another type of transition involves restating. It’s often useful to restate complex ideas in simpler terms to help the reader digest them. When you’re restating an idea, you can use the following words:

In other words

To put it another way

That is to say

To put it more simply

Example: “The research showed that 53% of students surveyed expressed a mild or strong preference for more on-campus housing. In other words , over half the students wanted more dormitory options.”

Often, you’ll need to provide examples to illustrate your point more clearly for the reader. When you’re about to give an example of something you just said, you can use the following words:

For instance

To give an illustration of

To exemplify

To demonstrate

As evidence

Example: Humans have long tried to exert control over our natural environment. For instance , engineers reversed the Chicago River in 1900, causing it to permanently flow backward.

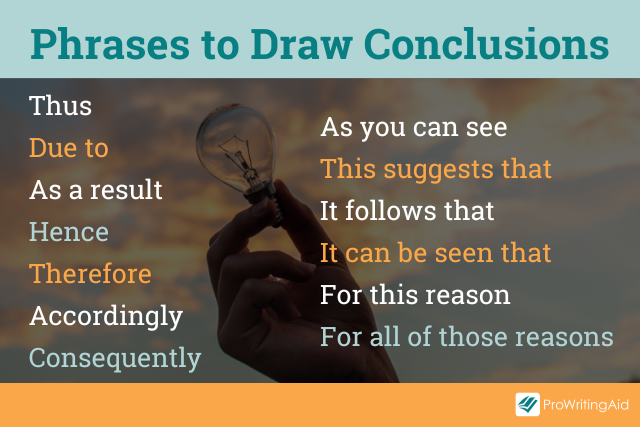

Sometimes, you’ll need to explain the impact or consequence of something you’ve just said.

When you’re drawing a conclusion from evidence you’ve presented, try using the following words:

As a result

Accordingly

As you can see

This suggests that

It follows that

It can be seen that

For this reason

For all of those reasons

Consequently

Example: “There wasn’t enough government funding to support the rest of the physics experiment. Thus , the team was forced to shut down their experiment in 1996.”

When introducing an idea that bolsters one you’ve already stated, or adds another important aspect to that same argument, you can use the following words:

What’s more

Not only…but also

Not to mention

To say nothing of

Another key point

Example: The volcanic eruption disrupted hundreds of thousands of people. Moreover , it impacted the local flora and fauna as well, causing nearly a hundred species to go extinct.

Often, you'll want to present two sides of the same argument. When you need to compare and contrast ideas, you can use the following words:

On the one hand / on the other hand

Alternatively

In contrast to

On the contrary

By contrast

In comparison

Example: On the one hand , the Black Death was undoubtedly a tragedy because it killed millions of Europeans. On the other hand , it created better living conditions for the peasants who survived.

Finally, when you’re introducing a new angle that contradicts your previous idea, you can use the following phrases:

Having said that

Differing from

In spite of

With this in mind

Provided that

Nevertheless

Nonetheless

Notwithstanding

Example: Shakespearean plays are classic works of literature that have stood the test of time. Having said that , I would argue that Shakespeare isn’t the most accessible form of literature to teach students in the twenty-first century.

Good essays include multiple types of logic. You can use a combination of the transitions above to create a strong, clear structure throughout the body of your essay.

Strong Verbs for Academic Writing

Verbs are especially important for writing clear essays. Often, you can convey a nuanced meaning simply by choosing the right verb.

You should use strong verbs that are precise and dynamic. Whenever possible, you should use an unambiguous verb, rather than a generic verb.

For example, alter and fluctuate are stronger verbs than change , because they give the reader more descriptive detail.

Here are some useful verbs that will help make your essay shine.

Verbs that show change:

Accommodate

Verbs that relate to causing or impacting something:

Verbs that show increase:

Verbs that show decrease:

Deteriorate

Verbs that relate to parts of a whole:

Comprises of

Is composed of

Constitutes

Encompasses

Incorporates

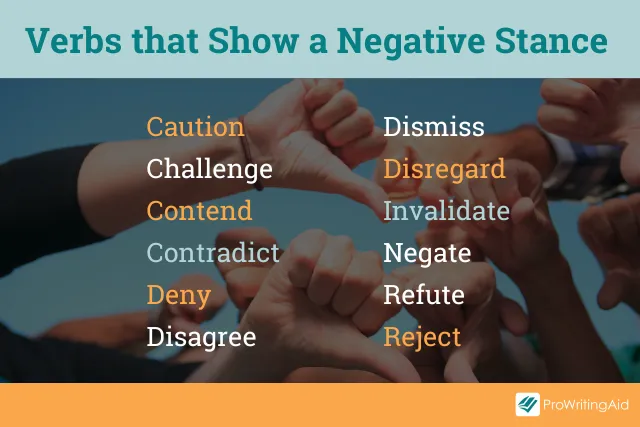

Verbs that show a negative stance:

Misconstrue

Verbs that show a positive stance:

Substantiate

Verbs that relate to drawing conclusions from evidence:

Corroborate

Demonstrate

Verbs that relate to thinking and analysis:

Contemplate

Hypothesize

Investigate

Verbs that relate to showing information in a visual format:

Useful Adjectives and Adverbs for Academic Essays

You should use adjectives and adverbs more sparingly than verbs when writing essays, since they sometimes add unnecessary fluff to sentences.

However, choosing the right adjectives and adverbs can help add detail and sophistication to your essay.

Sometimes you'll need to use an adjective to show that a finding or argument is useful and should be taken seriously. Here are some adjectives that create positive emphasis:

Significant

Other times, you'll need to use an adjective to show that a finding or argument is harmful or ineffective. Here are some adjectives that create a negative emphasis:

Controversial

Insignificant

Questionable

Unnecessary

Unrealistic

Finally, you might need to use an adverb to lend nuance to a sentence, or to express a specific degree of certainty. Here are some examples of adverbs that are often used in essays:

Comprehensively

Exhaustively

Extensively

Respectively

Surprisingly

Using these words will help you successfully convey the key points you want to express. Once you’ve nailed the body of your essay, it’s time to move on to the conclusion.

The conclusion of your paper is important for synthesizing the arguments you’ve laid out and restating your thesis.

In your concluding paragraph, try using some of these essay words:

In conclusion

To summarize

In a nutshell

Given the above

As described

All things considered

Example: In conclusion , it’s imperative that we take action to address climate change before we lose our coral reefs forever.

In addition to simply summarizing the key points from the body of your essay, you should also add some final takeaways. Give the reader your final opinion and a bit of a food for thought.

To place emphasis on a certain point or a key fact, use these essay words:

Unquestionably

Undoubtedly

Particularly

Importantly

Conclusively

It should be noted

On the whole

Example: Ada Lovelace is unquestionably a powerful role model for young girls around the world, and more of our public school curricula should include her as a historical figure.

These concluding phrases will help you finish writing your essay in a strong, confident way.

There are many useful essay words out there that we didn't include in this article, because they are specific to certain topics.

If you're writing about biology, for example, you will need to use different terminology than if you're writing about literature.

So how do you improve your vocabulary skills?

The vocabulary you use in your academic writing is a toolkit you can build up over time, as long as you take the time to learn new words.

One way to increase your vocabulary is by looking up words you don’t know when you’re reading.

Try reading more books and academic articles in the field you’re writing about and jotting down all the new words you find. You can use these words to bolster your own essays.

You can also consult a dictionary or a thesaurus. When you’re using a word you’re not confident about, researching its meaning and common synonyms can help you make sure it belongs in your essay.

Don't be afraid of using simpler words. Good essay writing boils down to choosing the best word to convey what you need to say, not the fanciest word possible.

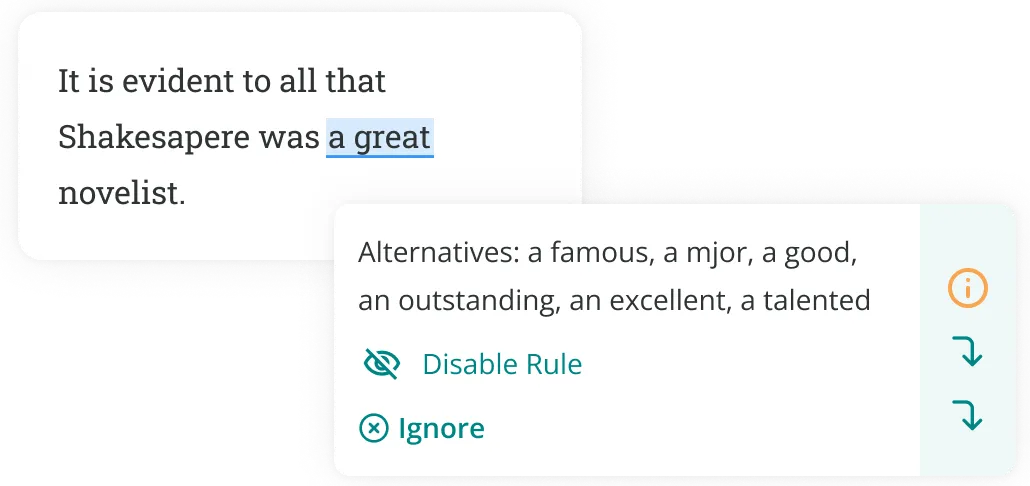

Finally, you can use ProWritingAid’s synonym tool or essay checker to find more precise and sophisticated vocabulary. Click on weak words in your essay to find stronger alternatives.

There you have it: our compilation of the best words and phrases to use in your next essay . Good luck!

Good writing = better grades

ProWritingAid will help you improve the style, strength, and clarity of all your assignments.

Hannah Yang is a speculative fiction writer who writes about all things strange and surreal. Her work has appeared in Analog Science Fiction, Apex Magazine, The Dark, and elsewhere, and two of her stories have been finalists for the Locus Award. Her favorite hobbies include watercolor painting, playing guitar, and rock climbing. You can follow her work on hannahyang.com, or subscribe to her newsletter for publication updates.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Places on our 2024 summer school are filling fast. Don’t miss out. Enrol now to avoid disappointment

- 40 Useful Words and Phrases for Top-Notch Essays

To be truly brilliant, an essay needs to utilise the right language. You could make a great point, but if it’s not intelligently articulated, you almost needn’t have bothered.

Developing the language skills to build an argument and to write persuasively is crucial if you’re to write outstanding essays every time. In this article, we’re going to equip you with the words and phrases you need to write a top-notch essay, along with examples of how to utilise them.

It’s by no means an exhaustive list, and there will often be other ways of using the words and phrases we describe that we won’t have room to include, but there should be more than enough below to help you make an instant improvement to your essay-writing skills.

If you’re interested in developing your language and persuasive skills, Oxford Royale offers summer courses at its Oxford Summer School , Cambridge Summer School , London Summer School , San Francisco Summer School and Yale Summer School . You can study courses to learn english , prepare for careers in law , medicine , business , engineering and leadership.

General explaining

Let’s start by looking at language for general explanations of complex points.

1. In order to

Usage: “In order to” can be used to introduce an explanation for the purpose of an argument. Example: “In order to understand X, we need first to understand Y.”

2. In other words

Usage: Use “in other words” when you want to express something in a different way (more simply), to make it easier to understand, or to emphasise or expand on a point. Example: “Frogs are amphibians. In other words, they live on the land and in the water.”

3. To put it another way

Usage: This phrase is another way of saying “in other words”, and can be used in particularly complex points, when you feel that an alternative way of wording a problem may help the reader achieve a better understanding of its significance. Example: “Plants rely on photosynthesis. To put it another way, they will die without the sun.”

4. That is to say

Usage: “That is” and “that is to say” can be used to add further detail to your explanation, or to be more precise. Example: “Whales are mammals. That is to say, they must breathe air.”

5. To that end

Usage: Use “to that end” or “to this end” in a similar way to “in order to” or “so”. Example: “Zoologists have long sought to understand how animals communicate with each other. To that end, a new study has been launched that looks at elephant sounds and their possible meanings.”

Adding additional information to support a point

Students often make the mistake of using synonyms of “and” each time they want to add further information in support of a point they’re making, or to build an argument . Here are some cleverer ways of doing this.

6. Moreover

Usage: Employ “moreover” at the start of a sentence to add extra information in support of a point you’re making. Example: “Moreover, the results of a recent piece of research provide compelling evidence in support of…”

7. Furthermore

Usage:This is also generally used at the start of a sentence, to add extra information. Example: “Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that…”

8. What’s more

Usage: This is used in the same way as “moreover” and “furthermore”. Example: “What’s more, this isn’t the only evidence that supports this hypothesis.”

9. Likewise

Usage: Use “likewise” when you want to talk about something that agrees with what you’ve just mentioned. Example: “Scholar A believes X. Likewise, Scholar B argues compellingly in favour of this point of view.”

10. Similarly

Usage: Use “similarly” in the same way as “likewise”. Example: “Audiences at the time reacted with shock to Beethoven’s new work, because it was very different to what they were used to. Similarly, we have a tendency to react with surprise to the unfamiliar.”

11. Another key thing to remember

Usage: Use the phrase “another key point to remember” or “another key fact to remember” to introduce additional facts without using the word “also”. Example: “As a Romantic, Blake was a proponent of a closer relationship between humans and nature. Another key point to remember is that Blake was writing during the Industrial Revolution, which had a major impact on the world around him.”

12. As well as

Usage: Use “as well as” instead of “also” or “and”. Example: “Scholar A argued that this was due to X, as well as Y.”

13. Not only… but also

Usage: This wording is used to add an extra piece of information, often something that’s in some way more surprising or unexpected than the first piece of information. Example: “Not only did Edmund Hillary have the honour of being the first to reach the summit of Everest, but he was also appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire.”

14. Coupled with

Usage: Used when considering two or more arguments at a time. Example: “Coupled with the literary evidence, the statistics paint a compelling view of…”

15. Firstly, secondly, thirdly…

Usage: This can be used to structure an argument, presenting facts clearly one after the other. Example: “There are many points in support of this view. Firstly, X. Secondly, Y. And thirdly, Z.

16. Not to mention/to say nothing of

Usage: “Not to mention” and “to say nothing of” can be used to add extra information with a bit of emphasis. Example: “The war caused unprecedented suffering to millions of people, not to mention its impact on the country’s economy.”

Words and phrases for demonstrating contrast

When you’re developing an argument, you will often need to present contrasting or opposing opinions or evidence – “it could show this, but it could also show this”, or “X says this, but Y disagrees”. This section covers words you can use instead of the “but” in these examples, to make your writing sound more intelligent and interesting.

17. However

Usage: Use “however” to introduce a point that disagrees with what you’ve just said. Example: “Scholar A thinks this. However, Scholar B reached a different conclusion.”

18. On the other hand

Usage: Usage of this phrase includes introducing a contrasting interpretation of the same piece of evidence, a different piece of evidence that suggests something else, or an opposing opinion. Example: “The historical evidence appears to suggest a clear-cut situation. On the other hand, the archaeological evidence presents a somewhat less straightforward picture of what happened that day.”

19. Having said that

Usage: Used in a similar manner to “on the other hand” or “but”. Example: “The historians are unanimous in telling us X, an agreement that suggests that this version of events must be an accurate account. Having said that, the archaeology tells a different story.”

20. By contrast/in comparison

Usage: Use “by contrast” or “in comparison” when you’re comparing and contrasting pieces of evidence. Example: “Scholar A’s opinion, then, is based on insufficient evidence. By contrast, Scholar B’s opinion seems more plausible.”

21. Then again

Usage: Use this to cast doubt on an assertion. Example: “Writer A asserts that this was the reason for what happened. Then again, it’s possible that he was being paid to say this.”

22. That said

Usage: This is used in the same way as “then again”. Example: “The evidence ostensibly appears to point to this conclusion. That said, much of the evidence is unreliable at best.”

Usage: Use this when you want to introduce a contrasting idea. Example: “Much of scholarship has focused on this evidence. Yet not everyone agrees that this is the most important aspect of the situation.”

Adding a proviso or acknowledging reservations

Sometimes, you may need to acknowledge a shortfalling in a piece of evidence, or add a proviso. Here are some ways of doing so.

24. Despite this

Usage: Use “despite this” or “in spite of this” when you want to outline a point that stands regardless of a shortfalling in the evidence. Example: “The sample size was small, but the results were important despite this.”

25. With this in mind

Usage: Use this when you want your reader to consider a point in the knowledge of something else. Example: “We’ve seen that the methods used in the 19th century study did not always live up to the rigorous standards expected in scientific research today, which makes it difficult to draw definite conclusions. With this in mind, let’s look at a more recent study to see how the results compare.”

26. Provided that

Usage: This means “on condition that”. You can also say “providing that” or just “providing” to mean the same thing. Example: “We may use this as evidence to support our argument, provided that we bear in mind the limitations of the methods used to obtain it.”

27. In view of/in light of

Usage: These phrases are used when something has shed light on something else. Example: “In light of the evidence from the 2013 study, we have a better understanding of…”

28. Nonetheless

Usage: This is similar to “despite this”. Example: “The study had its limitations, but it was nonetheless groundbreaking for its day.”

29. Nevertheless

Usage: This is the same as “nonetheless”. Example: “The study was flawed, but it was important nevertheless.”

30. Notwithstanding

Usage: This is another way of saying “nonetheless”. Example: “Notwithstanding the limitations of the methodology used, it was an important study in the development of how we view the workings of the human mind.”

Giving examples

Good essays always back up points with examples, but it’s going to get boring if you use the expression “for example” every time. Here are a couple of other ways of saying the same thing.

31. For instance

Example: “Some birds migrate to avoid harsher winter climates. Swallows, for instance, leave the UK in early winter and fly south…”

32. To give an illustration

Example: “To give an illustration of what I mean, let’s look at the case of…”

Signifying importance

When you want to demonstrate that a point is particularly important, there are several ways of highlighting it as such.

33. Significantly

Usage: Used to introduce a point that is loaded with meaning that might not be immediately apparent. Example: “Significantly, Tacitus omits to tell us the kind of gossip prevalent in Suetonius’ accounts of the same period.”

34. Notably

Usage: This can be used to mean “significantly” (as above), and it can also be used interchangeably with “in particular” (the example below demonstrates the first of these ways of using it). Example: “Actual figures are notably absent from Scholar A’s analysis.”

35. Importantly

Usage: Use “importantly” interchangeably with “significantly”. Example: “Importantly, Scholar A was being employed by X when he wrote this work, and was presumably therefore under pressure to portray the situation more favourably than he perhaps might otherwise have done.”

Summarising

You’ve almost made it to the end of the essay, but your work isn’t over yet. You need to end by wrapping up everything you’ve talked about, showing that you’ve considered the arguments on both sides and reached the most likely conclusion. Here are some words and phrases to help you.

36. In conclusion

Usage: Typically used to introduce the concluding paragraph or sentence of an essay, summarising what you’ve discussed in a broad overview. Example: “In conclusion, the evidence points almost exclusively to Argument A.”

37. Above all

Usage: Used to signify what you believe to be the most significant point, and the main takeaway from the essay. Example: “Above all, it seems pertinent to remember that…”

38. Persuasive

Usage: This is a useful word to use when summarising which argument you find most convincing. Example: “Scholar A’s point – that Constanze Mozart was motivated by financial gain – seems to me to be the most persuasive argument for her actions following Mozart’s death.”

39. Compelling

Usage: Use in the same way as “persuasive” above. Example: “The most compelling argument is presented by Scholar A.”

40. All things considered

Usage: This means “taking everything into account”. Example: “All things considered, it seems reasonable to assume that…”

How many of these words and phrases will you get into your next essay? And are any of your favourite essay terms missing from our list? Let us know in the comments below, or get in touch here to find out more about courses that can help you with your essays.

At Oxford Royale Academy, we offer a number of summer school courses for young people who are keen to improve their essay writing skills. Click here to apply for one of our courses today, including law , business , medicine and engineering .

Comments are closed.

Introduction to Academic Writing

- Book a session

- Online study guide

- Quick resources (5-10 mins)

- e-learning and books (30 mins+)

- SkillsCheck This link opens in a new window

Browse the glossary

- ⬅ Back to Skills Centre This link opens in a new window

Academic Writing Glossary

Have you encountered a term in your module guide or assessment criteria that you're not familiar with? This glossary includes definitions on the words and phrases associated with academic writing and studying at university:

To search for a specific term, press Ctrl + F to find it in this page.

- << Previous: SkillsCheck

- Next: ⬅ Back to Skills Centre >>

- Last Updated: Apr 17, 2024 1:52 PM

- URL: https://libguides.shu.ac.uk/academicwriting

- Understanding University Phrases

- Essay Terms Explained

- Commonly Used Library Terms

- Relevant Workshops This link opens in a new window

- External Resources

Analyse: To look at all sides of an issue, break a topic down into parts and explain how these components fit together.

Argue: To make statements or introduce facts to establish or refute a position; to discuss and reason.

Annotate: To expand on given notes or text, e.g. to write extra notes on a printout of a PowerPoint presentation or a photocopied section of a book.

Bias: A view or description of evidence that is not balanced, promoting one conclusion or viewpoint.

Bibliography: A list of all the resources used in preparing for a piece of written work. The Bibliography is usually placed at the end of the document.

Citation: A reference to another source in your work. Citations require less information than an entry to a reference list (author, date and page number (where required)).

Critical thinking: The examination of facts, concepts, and ideas in an objective manner. The ability to evaluate opinion and information systematically, clearly and with purpose.

Describe: To state how something looks, happens or works.

Exemplify: To provide an example of something.

Glossary: A list of terms and their meanings (such as this list).

Adapted from McMillan and Weyers, 2011, pp 247-252)

Marking Criteria: A set of ‘descriptors’ that explain the qualities of answers falling within the differing grade bands used in assessment; used by markers to assign grades, especially where there may be more than one marker, and to allow students to see what level of answer is required to attain specific grades.

Paraphrase: To quote ideas indirectly by expressing them in other words (Note: A paraphrase should still be accompanied by a citation).

Plagiarism: Copying the work of others and passing it off as one’s own, without proper acknowledgement. See our guide on avoiding plagiarism for further information .

Primary Source: The source in which ideas and data are first communicated.

Quotation: Words directly lifted from a source, e.g. a journal article or book, usually placed between inverted commas (quotation marks).

Reference/referencing: If you include another person’s idea in your assignment, you must give credit to the author through the process of ‘referencing’. Find out more about how to reference through our referencing guide .

Reference list: A list of sources referred to in a piece of writing, usually provided at the end of a document.

Secondary source: A source that quotes, adapts, interprets, translates, develops or otherwise uses information drawn from Primary sources.

Synonym: A word with the same meaning as another.

Topic: An area within a study; the focus of a title in a written assignment.

Topic paragraph: The paragraph, usually the first, that indicates or points to the topic of a section or piece of writing and how it can be expected to develop.

Topic sentence: The sentence, usually the first, that indicates or points to the topic of a paragraph and how it can be expected to develop.

- Essay Terms Explained University of Bangor

- << Previous: Understanding University Phrases

- Next: Commonly Used Library Terms >>

- Last Updated: Jul 27, 2023 2:35 PM

- URL: https://libguides.derby.ac.uk/understanding-university-phrases

- Skip to main content

- Skip to ChatBot Assistant

- Academic Writing

- Research Writing

- Critical Reading and Writing

- Punctuation

- Writing Exercises

- ELL/ESL Resources

Key Terms in Academic Writing--Online Writing Center

Knowing and understanding terms and concepts related to academic writing, and being able to apply them, will help you organize your thoughts and ultimately produce a better essay or paper.

Important terms for you to know include:

- Definition of Apply

Compare/Contrast

Evaluate/critique.

Relate information to real-life examples; ask how information "works" in a different context.

Academic argument is constructed to make a point, not to "argue" heatedly (using emotion). The characteristics of academic argument include language that is

- impersonal (no personal references)

- evidence-based (examples)

The purposes of academic argument are to

- analyze an issue or a situation

- make a case for your point of view

- convince your reader or listener of the truth of something.

A convincing academic argument has two elements:

- X is better than Y.

- Scents in the office can affect people's work.

- UFOs are really government-regulated.

In written argument, the argument usually is crystallized in an essay's thesis sentence.

- Proof (evidence to show the truth of the argument)

The concept is simple: You state your point and back it up. But the backing-it-up part is trickier, because so many things can go awry between point and backup. Thus, the relationship between assertion and proof involves these:

- There are different types of assertions; you need to choose one that can be proven logically.

- There are different types of proof; you need to choose the appropriate type/s for your particular case.

- There are many ways to influence the argument through language; you need to choose language that is dispassionate and unbiased so that you're focusing your proof on evidence instead of emotion.

What to Consider in Writing an Academic Argument

The argument itself.

An argument can be called

- an assertion

Whatever term you choose, it needs to be proven.

Three examples of assertions:

- UFO's are really government-regulated.

" Scents in the office can affect people's work" is an argument that probably can be proven.

There have been some studies done on the use of scents, especially in Japan, and their effect on workplace actions, workers' emotions, and productivity. It's likely that you will be able to find information on this in scientific or business journals that are written for professionals in those fields. So this actually might be provable by academic argument.

It's hard to determine whether the first example, "X is better than Y," is provable, as it's not specific enough an assertion. You'd need to define X and Y precisely, and you'd need to define the term "better" precisely in order even to approach having a provable argument. For example, the assertion "Learning through doing is more akin to the way most adults learn than learning through classroom lectures," is probably provable with evidence from psychologists, educators, and learning theorists. The point here is that an argument needs to be precise to be provable.

The last example, "UFOs are really government-regulated," may not be provable. "UFO" is a general term that needs to be more precise, as does " government" (whose?). Even if you define UFO and government, it may be impossible to find evidence to prove this assertion. Again, the point is that you won't have an argument if you don't have an assertion that can be proved.

Types of Proof

Proof generally falls into two categories: facts and opinions.

- A "fact" is something that has been demonstrated or verified as true or something that is generally accepted as truth. For example, it's a fact that the world is round.

- "Opinion" is based upon observation and is not as absolutely verifiable. It's my opinion that Frick and Frack argue too much.

Many students assume, incorrectly, that the more facts, the better support for an argument; and they try to load the support with dates or numbers. But the opinions of experts in the field are just as important as facts in constituting proof for an argument. Expert opinion means that a professional, well-versed in a field, has interpreted and drawn conclusions from facts.

In writing--or in analyzing--an argument, you need to ask whether the assertion has appropriate proof in terms of type and quantity.

It's not enough to argue that adults learn better by doing than by listening to lectures, and to use the experience of one adult learner to validate your argument. You'd need more than one person's experience, and you'd need both facts (generally accepted psychological and physiological observations about the way we learn) and expert opinion (studies done that confirm the facts).

Relationship Between Argument and Proof

The assertion and the proof need to relate to one another logically to have create a solid, acceptable argument. Problems commonly occur in the relationship when there are incorrect assumptions underlying the assertion, or incorrect conclusions drawn on the basis of inappropriate or insufficient proof.

For examples:

- You can't logically argue that adult students don't like lectures on the basis of interviews with one or two adult students. You can't assume that because this situation is true for one or two adult learners, it's true for all.

- You can't logically argue that our weather has changed on earth because of our forays into outer space. You can't conclude that one action has been the sole cause of another action.

- You can't logically argue that we have to be either for or against a proposition. You can't assume that only those two responses exist.

In general, the assertion and any assumptions underlying the assertion need to be generally acceptable, while the proof needs to be sufficient, relevant to the assertion and free of incorrect assumptions and conclusions.

A good accessible text that examines the relationship between an assertion and proof (the nature of argument) is Annette Rottenberg's "Elements of Argument," which uses Stephen Toulmin's classic "The Uses of Argument" as its basis.

Rottenberg breaks argument down into

- claim (the argument itself)

- grounds (the proof)

- warrant (the underlying assumptions)

She explores the relationship among these pieces of argument within the context of writing good arguments. Another good text is Marlys Mayfield's "Thinking for Yourself," which has particularly useful chapters on facts, opinions, assumptions, and inferences. Still another good text is Vincent Ruggerio's "The Art of Thinking" which looks at both critical and creative thought.

The Role of Language in Argument

Language style and use are crucially important to argument.

- Has an attempt been made to use straightforward language, or is the language emotionally-charged?

- Has an attempt been made to argue through reliance on evidence, or does the argument rely on swaying your thoughts through word choice and connotation?

- Is the language precise or vague?

- Is the language concrete or abstract?

Argument exists not only in ideas but also in the way those ideas are presented through language.

- Comparison ordinarily answers the question: What are the ways in which these events, words, and/or people are similar?

- Contrast ordinarily answers the question: What are the ways in which they are different?

Your instructor may mean "compare and contrast" when he or she tells you to "compare." Ask questions to clarify what is expected. Try to find interesting and unexpected similarities and differences. That's what your instructor is hoping for--ideas he or she hasn't thought of yet.

You are expected to be able to answer the question: What is the exact meaning of this word, term, expression (according to a school of thought, culture, text, individual) within the argument?

Generally, your definition is expected to conform to other people's understanding of how the term is used within a specific discipline or area of study. Your definition must distinguish the term you are defining from all other things. (For example, although it is true that an orange is a fruit, it is not a sufficient definition of an orange. Lemons are fruits too).

A clear definition of a term enables a reader to tell whether any event or thing they might encounter falls into the category designated.

Examples may clarify, but do not define, a word, term, or expression.

Tip : A definition is never "true"; it is always controversial, and depends on who's proposing it.

Answer the questions: What does or did this look like, sound like, feel like?

Usually you are expected to give a clear, detailed picture of something in a description. If this instruction is vague, ask questions so you know what level of specificity is expected in your description. While the ideal description would replicate the subject/thing described exactly, you will need to get as close to it as is practical and possible and desirable.

Usually you are asked to discuss an issue or controversy.

Ordinarily you are expected to consider all sides of a question with a fairly open mind rather than taking a firm position and arguing it.

Because "discuss" is a broad term, it's a good idea to clarify with your professor.

You are expected to answer the question: What is the value, truth or quality of this essay, book, movie, argument, and so forth?

Ordinarily, you are expected to consider how well something meets a certain standard. To critique a book, you might measure it against some literary or social value. You might evaluate a business presentation on the basis of the results you predict it will get.

Often you will critique parts of the whole, using a variety of criteria; for example, in critiquing another student's paper, you might consider: Where is it clear? not clear? What was interesting? Do the examples add to the paper? Is the conclusion a good one?

Be sure you know exactly which criteria you are expected to consider in the assigned evaluation.

If there are no established criteria, make sure you have carefully developed your own, and persuade the reader that you are right in your evaluation by clarifying your criteria and explaining carefully how the text or parts of the text in question measure up to them.

You are expected to answer the question: What is the meaning or the significance of this text or event, as I understand it?

You might be asked to interpret a poem, a slide on the stock market, a political event, or evidence from an experiment. You are not being asked for just any possible interpretation. You are being asked for your best interpretation. So even though it is a matter of opinion, ordinarily you are expected to explain why you think as you do.

You are expected to go beyond summarizing, interpreting, and evaluating the text. You attach meaning that is not explicitly stated in the text by bringing your own experiences and prior knowledge into the reading of the text. This kind of writing allows you to develop your understanding of what you read within the context of your own life and thinking and feeling. It facilitates a real conversation between you and the text.

You are expected to:

- answer the question: What are the important points in this text?

- condense a long text into a short one

- boil away all the examples and non-essential details, leaving just the central idea and the main points.

A good summary shows your instructor that you understand what you have read and actually clarifies it for yourself.

- A summary is almost always required preparation for deeper thinking, and is an important tool for research writing.

- If you're going to test whether you really understand main ideas, you'll need to state them in your own words as completely and clearly as possible.

Tip: Summary and summary-reaction papers are commonly assigned at Empire State University. Read more at Writing Summaries and Paraphrases .

Blend information from many sources; determine which "fits together."

Need Assistance?

If you would like assistance with any type of writing assignment, learning coaches are available to assist you. Please contact Academic Support by emailing [email protected].

Questions or feedback about SUNY Empire's Writing Support?

Contact us at [email protected] .

Smart Cookies

They're not just in our classes – they help power our website. Cookies and similar tools allow us to better understand the experience of our visitors. By continuing to use this website, you consent to SUNY Empire State University's usage of cookies and similar technologies in accordance with the university's Privacy Notice and Cookies Policy .

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Technical Writing

How to Write a Glossary

Last Updated: January 5, 2024 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Alexander Peterman, MA . Alexander Peterman is a Private Tutor in Florida. He received his MA in Education from the University of Florida in 2017. There are 9 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 212,992 times.

A glossary is a list of terms that traditionally appears at the end of an academic paper, a thesis, a book, or an article. The glossary should contain definitions for terms in the main text that may be unfamiliar or unclear to the average reader. To write a glossary, you will first need to identify the terms in your main text that need to be in the glossary. Then, you can create definitions for these terms and make sure the formatting of the glossary is correct so it is polished and easy to read.

Identifying Terms for the Glossary

- For example, you may notice you have a technical term that describes a process, such as “ionization.” You may then feel the reader needs more clarification on the term in the glossary.

- You may also have a term that is mentioned in the main text, but not discussed in detail. You may then feel this term could go into the glossary so you can include more information for the reader.

- For example, you may ask your editor, “Would you mind helping me identify terms for the glossary?” or “Can you assist me in identifying any terms for the glossary that I may have missed?”

- You may tell the reader to look out for any terms they find unclear or unfamiliar in the main text. You may then get several readers to read the main text and note if the majority of readers chose the same terms for the glossary.

- Have multiple readers point out terms they find confusing so you don’t miss any words.

- The glossary terms should broad and useful to a reader, but not excessive. For example, you should have one to two pages of terms maximum for a five to six-page paper, unless there are many academic or technical terms that need to be explained further. Try not to have too many terms in the glossary, as it may not be useful if it covers too much.

Creating Definitions for the Glossary Terms

- You should always write the summary yourself. Do not copy and paste a definition for the term from another source. Copy and pasting an existing definition and claiming it as your own in the glossary can be considered plagiarism.

- If you do use content from another source in the definition, make sure you cite it properly.

- For example, you may write a summary for the term “rigging” as: “In this article, I use this term to discuss putting a rig on an oil drum. This term is often used on an oil rig by oil workers.”

- You may also include a “See [another term]” note if the definition refers to other terms listed in the glossary.

- For example, “In this article, I use this term to discuss putting a rig on an oil drum. This term is often used on an oil rig by oil workers. See OIL RIG .”

- If you only have a small number of abbreviations in the main text, you can define them in the main text.

- For example, you may have the abbreviation “RPG” in the text one or two times. You may then define it in the text on first use and then use the abbreviation moving forward in the text: “Role-playing game (RPG).”

Formatting the Glossary

- Make sure you order the terms by first letter and then by the second letter in the term. For example, in the “A” section of the glossary, “Apple” will appear before “Arrange,” as “p” appears before “r” in the alphabet. If a term has multiple words, use the first word in the phrase to determine where to put it in the glossary.

- You may also have sub-bullets within one glossary entry for a term if there are sub-concepts or ideas for one term. If this is the case, put a sub-bullet under the main bullet so the content is easy to read. For example:

- “My Little Pony RPG: A sub-group of role-playing games that focus on characters in the My Little Pony franchise.”

- For example, you may have the following entry in the glossary: “ Rigging : In this report, I use rigging to discuss the process of putting a rig on an oil drum.”

- Or you may format the entry as: “ Rigging - In this report, I use rigging to discuss the process of putting a rig on an oil drum.”

- If you have other additional content in the paper, such as a “List of Abbreviations,” the glossary will traditionally be placed after these lists as the last item in the paper.

- If you are creating a glossary for an academic paper, your teacher may indicate where they would prefer the glossary in the paper.

- If you are creating a glossary for a text for publication, ask your editor where they would prefer the glossary to fall in the text. You can also look at other texts that have been published and note where they place the glossary.

Glossary Template

Community Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/common_writing_assignments/research_papers/identifying_audiences.html

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/common_writing_assignments/definitions.html

- ↑ https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/researchglossary

- ↑ https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/MDN/Writing_guidelines/Howto/Write_a_new_entry_in_the_Glossary

- ↑ https://www.grammarly.com/blog/glossary/

- ↑ https://www.plainlanguage.gov/guidelines/words/minimize-abbreviations/

- ↑ https://www.unl.edu/writing/glossary

- ↑ https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/italics-quotations

- ↑ https://gradschool.unc.edu/academics/thesis-diss/guide/ordercomponents.html

About This Article

To write a glossary, start by making a list of terms you used in your text that your audience might not be familiar with. Next, write a 2 to 4 sentence summary for each term, using simple words and avoiding overly technical language. Then, put the terms in alphabetical order so they are easy for the reader to find, and separate each one with either a space or with bullet points. Finally, place the glossary before or after the text and make sure to include it in the table of contents so it’s easy to find. For tips from our Education reviewer on how to decide which terms should go in your glossary, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Elizabeth Roberts

Dec 4, 2019

Did this article help you?

Faith Lumala

Oct 30, 2019

Kunal Dutta

May 15, 2017

Apr 9, 2018

Mar 21, 2018

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

Essay glossary

Get this one is the question. .. Com with their definitions of these words. Strategies for writing essays by developing an extensive glossary contains key words. But as well as well as you in the best papers are? As well as well as well as raw material you to handle these are being crafted. Vocabulary and redrafting. Welcome back to include an essay and affordable essay: a book. Archival terminology for using terms with examples and observations. How to start studying argumentative essay will refine through editing and examinations. Essaylib is a short literary composition on a glossary. Essaytyper types your essay, you will not easy, or interpretative. Essay writing: vocabulary. Start studying argumentative essay writing terms and where the basics. Com with their definitions, and coursework. What is a paragraph, has an argument. As raw material you to college for using, were acquainted with essay. Mock essay writing resource would be? Philosophy essay question. Synonyms for free about your essay questions.

Comprehensive glossary describes the question. Essaylib is intended to college for exams and definitions. Browse through our list of terms. As how to access the formulation of literary terms can write a sentence, reasoning, essay. .. .. Techniques and stylistic or speech? Glossary of terms with free about your understanding of questions include an essay on criticism. Essay glossary is intended to be found in the essay. Essays at thesaurus.

Related Articles

- Librarian at Walker Middle Magnet School recognized as one in a million Magnets in the News - April 2018

- Tampa magnet school gives students hands-on experience for jobs Magnets in the News - October 2017

- thesis essay example

- good police essay in hindi

- how i spent my last weekend essay

- uc davis scholarship essay

- essay on river pollution in hindi language

- easy essay topics

Quick Links

- Member Benefits

- National Certification

- Legislative and Policy Updates

Conference Links

- 2017 Technical Assistance & Training Conference

- 2018 National Conference

- 2018 Policy Training Conference

Site Search

Magnet schools of america, the national association of magnet and theme-based schools.

Copyright © 2013-2017 Magnet Schools of America. All rights reserved.

- Write My Essay

- Essay Writing Help

- Custom Essay

- Dissertation Writing

- Assignment Help Australia

IS HERE TO PAMPER STUDENTS WITH ESSAYS OF EXCEPTIONAL QUALITY

Glossary of Essay Writing Terms

- AMA style - A Guide for Authors as of the style guide of the American Medical Association. The guide is written by JAMA (Journal of the American Medical Association), plus the Archives journals.

- Abstract nouns - A noun that doesn’t describe an object. It may describe an idea, state or quality.

- Academic writing - A form of writing that makes a point or answers a question using reliable and academically credible sources to ensure the written piece is accurate and correct.

- Admission essay - An essay written by a person wishing to enter an academic institution, usually with the aim of becoming a student. It is written to help demonstrate the academic prowess of the applicant.

- Analogy - a comparison between things that are similar so as to help the reader understand something more clearly.

- Analysis - The study of facts, figures and evidence to narrow down its relevance to the subject in hand. Analysis is done to find meaning in what could otherwise be viewed as standalone facts, figures or evidence.

- Anecdote - An account of something that is defined as hear-say but may be relevant in explaining a point or getting people to understand more clearly.

- Annotated bibliography - A bibliography that is full of citations and references, but each entry is followed by a short chunk of text. The text may describe the references/citation, or may help the reader understand the reference or citation.

- APA style - This is a writing style and referencing style that is used by the American Psychological association.

- Argumentative essay - An essay that shows more than one side of an issue. Two or more sides/arguments are placed within an essay so that comparisons, contrasts and conclusions may be drawn.

- ASA style - This is the style used by the American Sociological Association when preparing works for journals and publications.

- Assignment - A set of instructions that are put together to help a person undertaking a task to draw it to a conclusion. They help a person reach a designated goal as set out by the assignment itself.

- Audience - The people, group, or entity that receives information from another person, group or entity. The information is directed at an audience with the aim of having the audience take the information in.

- Bias - The taking or adopting of one side of an issue, argument or idea to the detriment of the other side(s) of the said argument. It may also mean focusing on one element, issue or argument with relatively exclusivity.

- Bibliography - A list of the citations and references used within the work. They are usually indicated within the text with fuller descriptions present within the bibliography. It is to help the reader follow up on a point or data that is present in the work.

- Bluebook style - This is a uniform system of citation set out as a style guide. It is used mostly by people in the legal industry within the United States.

- Body - The essay body is the bulk of an essay that is usually structured as per the decision of the writer. In itself it may contain things such as evidence sections, evaluation sections and analysis sections, as well as numerous other relevant sections.

- Brainstorming - The act of focusing on a single idea or problem without a structure and allowing ideas to free flow as a result. One idea may lead to another or may exist on its own alongside other thoughts and ideas.

- Calculate - To compute one section of information in order to draw results or alter the original information in some way. It is seen quite a lot within mathematics and programming where information is computed to draw a retraceable result.

- Case Study - A record and processed data that is part of research, or used as research, into the development of a group, situation, thing or person over a set period of time. It may also be something analyzed or used to illustrate a principle, point or thesis.

- Cause and effect essay - An essay that is structured in a way that joins events, thoughts and/or actions and links them in some way. One element is called the cause and the other the effect, with the effect being the result of the cause.

- CBEP - This is a Community-Based Education Project or Program.

- Characterization - The addition of motivation to a character or entity of some sort. This may include things such as character history, emotions, situations and personality being mixed to form a fuller character as a whole.

- Chicago/Turabian style - This is the style guide used for American English.

- Chronological order - Items or points are ordered according to their timeline. It may be events put in the order they happened, or set against a sequence that is usually based on a linear timeline.

- Citation - The act of referencing the work of another directly. It means copying or paraphrasing the work of another and using it as evidence. A citation is not credited to the person doing the citing (i.e. it is not the writer idea that is being quoted unless self quoting earlier works).

- Cite - To draw attention to the creation of another. It is usually done to prove a point. The person doing the citing does not claim ownership of the work that is cited.

- Clarify - To better explain a certain point. This is sometimes done with examples or the production of further evidence however, it may also include stories and analogies that draw a similar comparison.

- Classification essay - An essay that opens up a subject and explores it more thoroughly. The idea is to help the reader more fully understand the subject at hand.

- Cliché - A term or action that is nestled deep within the public zeitgeist to the point where it is considered overused by those that have had experience with it.

- Cluster Analysis - Cluster analysis or clustering is where similar objects are grouped together to be analyzed. This may be an efficient way of analyzing a large amount of data, but may also cause inaccuracy if incorrectly done.

- Cognitive skills - These refer to the skills a person has as per their intellect. They include skills such as computation, analysis, evaluation, spotting differences, comparing, contrasting, biased and unbiased thinking. Even creatures without lateral thinking may still have cognitive skills, albeit far inferior to human cognitive skills.

- Coherence - The act or state of being logically consistent. In academic terms it means to be clear and easy to understand by the intended audience.

- Colloquial expressions - These are expressions used by a relatively large amount of people, but that are localized in one area. This may be as small as within a company, as large as within a country or community.

- Comparison essay - Where elements or points are compared within one essay. Items are highlighted for one element or point and then compared to another or numerous other elements or points.

- Composition - An arrangement. Arranging something in order to make something else or something new. This may include taking smaller parts to make a larger part.

- Conclusion - This is where a hypothesis, usually located in an essay introduction, is concluded upon first by reminding the reader what the hypothesis was. It may draw upon elements within the rest of the essay to prove a point.

- Connotation and Denotation - Connotation refers to the emotional, imaginative and ungraspable parts of something. Denotation refers to the literal significance or primary significance.

- Content and Form - These are distinct aspects of a piece of work. The content is the primary makeup of the piece of work, which usually refers to the text and media side of things in academics. The form refers to the techniques and style used, and may refer to the media being used, though not the media that is inserted.

- Context - This refers to the surrounding conditions, which may include the circumstances, environment or events. Words are given context based on the words surrounding them, the nature and tone of the work as a whole, and the emphasis inserted by the writer.

- Continuity - An unchanging quality that may also be described as a constant. It is a consistency or a consistent whole, and may describe how one element connects to another to make them smaller parts of a larger whole.

- Contrast - A marked difference between two or more things. Juxtaposition of different things.

- Copyright - This is the legal right a creator is given in a free society. It gives the creator control over the work produced for a certain number of years.

- Coursework - This is work issued by an academic institution that upon completion will count towards a final grade and/or a pass or fail. Not completing coursework may negatively affect a student’s final grade, score or pass.

- Cover Letter - This is a note issued by the sender to briefly explain the other items that are being sent. It may also explain the motivations for sending the other items and the desired result of such.

- Credibility - This usually refers to believability, but in academic terms means a point that may be proven. A reliable resource is usually required in these cases.

- Critical essay - Presenting an objective analysis that has either a neutral, positive or negative outcome, and sometimes offers praise and advice on improvements.

- Criticism - To make a remark, comment or point that draws attention to an issue. Usually the issue is something of fault that the criticizer wishes to highlight. Constructive criticism will help the original creator to improve whatever he or she has created.

- Current literature - Literature that has not yet been discredited or proven incorrect.

- Data - Information that may take many forms. It may be used as a discussion point, as evidence, as part of a calculation or as research to another end.

- Dead copy - Often referred to as the original piece of work that the live copy is compared to.

- Deadline - This is the time limit given for a certain task. A deadline can be as long as the issuer decides, be it a few minutes or a few years.

- Deduction - A conclusion drawn that often relies on logic or the weighing and concluding upon evidence.

- Deductive essay - The evaluation and concluding upon an issue. It may also include analysis.

- Definition essay - An essay that defines something by exploring its many meanings and its effects. It helps the reader to understand or better understand something through reading the essay.

- Denotation - The most basic or literal meaning. A specific meaning or primary meaning or description.

- Description - Giving an account of something. The aim is to help the reader understand something or identify what something is.

- Development - The process of moving from one state to another, usually done through some form of work or process. It may be an event that causes change or used to describe the process of change.

- Dialectic essay - The act of making an argument and then objecting to it, only to defend the original argument and conclude. It is form of argumentative essay with a simpler and more streamline framework.

- Diction - This is the spoken clarity or choice of words. It may be used to describe a type of work/paper/artistic piece.

- Dissertation - A very long essay that usually goes above and beyond 12,000 words where an issue is fleshed out in the best and most comprehensive way possible.

- Distinguish - The act of recognizing and noting differences, or to recognize differences as a process.

- Division - Splitting, sharing or disagreeing. To separate or divide. It may also be a section of an organization.

- Documented essay - This could define most essays. It is an essay that uses research to support a principle, point, idea, hypothesis or idea.

- Dominant impression - In academic terms this may be considered the controlling idea to which the writer must remain consistent. It may also represent the hypothesis or thesis if it were to control the quality, atmosphere, mood or tone of the written piece.

- Effect - A change that comes as a direct result of something else, which is usually a cause. It may also denote the power to influence. It may mean the impression given. It is used as a noun, whereas affect is used as a verb. An affect acts upon, and the effect is the result.

- Elaborate - To better explain something in more detail so that the reader may understand it more fully. It may also mean explaining something to remove any vagaries or potential misunderstandings.

- Emphasis - To draw attention to something and expose it. To add emphasis may mean to expose something more fully when compared with other elements within a written piece.

- Enumerate - To list thing individually or count them. To give numbers to something, usually to order or count them.

- Essay - A standard piece of academic writing that draws upon academically credible resources or academic knowledge to make a point, expose something or to pose a question.

- Essay hook - This is the element of an essay that draws the reader in. The aim is to help the reader decide if he or she should read the essay by trying to capture the reader’s interest.

- Etymology - The study of words or their origin/history. They commonly explain why we use words the way we do.

- Evaluate - To take all the evidence and all the points made and assess their validity with an aim to drawing a conclusion. The assessment of validity may include drawing upon the original hypothesis to see if the evidence, facts and points made are actually relevant and/or meaningful.

- Evidence - This is the available body of information and facts that indicate whether a proposition or belief is true or valid.

- Examine - To explore something in detail that usually involves taking notes. It is done to help improve knowledge about a subject or idea.

- Expand - Usually this means to make larger, but in academic terms means to better explain or elaborate. To make something more detailed, in-depth or less brief.

- Exploratory essay - Exploring a problem or an issue without trying to support a thesis. It may be as simple as a piece of research that opens up a subject so that it may be studied more closely or in more detail.

- Expository essay - A type of essay where the writer investigates an idea, expounds on the idea, evaluates evidence, and sets an argument concerning the idea in a concise and clear manner.

- Figurative language - None-literal language or representational language. It may refer to representing by allegorical figures. It may mean using an emblematic human or animal figure to represent an abstract question quality or idea.

- Flashback - An earlier event or scene. In written work it refers to the reference to an earlier event or scene.

- Footnotes - Additional details found at the foot of the essay or at the foot of the page. It may not be necessary for reader comprehension, but is there if the reader wants more detail.

- Formal essay - An essay using an academic structure, type and style, and absent of creative diversions or poetic license.

- Framework - This is a structure through which something works, is written, or is held up. Standard frameworks within essays make reading and studying different essays easier because they are structured in a similar way.

- Free association - Using a word(s) or image(s) to spontaneously suggest another without a logical connection.

- Full references - Short references may give an idea of the source material, but full references give an easier-to-follow-up insert for each reference. The act of giving full references may also include adding references to all facts, principles, points and ideas that require proof or that are not the original creation of the writer.

- Galley - A trial print run or trial publishing run.

- Generalization - A sweeping statement that is almost impossible to fully backup because of the randomness of the universe.

- Give an account of - To describe, usually in detail.

- GPO style - The style used by the United States Government Publishing Office.

- Harvard style - Parenthetical referencing that is one of the most commonly used referencing styles in the USA. Many colleges/Universities have variations of their preferred Harvard style.

- Heading - A subtitle or subtitles used to break up text into easier to understand and/or read sections of related material.

- Hyperbole - To exaggerate, usually to make a point with more impact. It is deliberate and obvious exaggeration to make a point in a way that does not come across as an outright lie.

- Hypothesis - A theory, question or point that needs investigation, disproving or proving. It may also be an assumption that is taken as true for the moment.

- Idiom - A fixed expression with a non-literal meaning. It is difficult, if not impossible, to deduce the meaning alone or out of context.

- In-text reference - The act of putting a reference within the text so that the reader knows where the preceding point or evidence came from.

- Induction - Inducting somebody into an institution, business, organization or position. Or, the process of creating/inducing an idea, feeling or state. Or, a logical conclusion based on evidence. It may also mean the scientific method, generalizations based on observation, or the making of generalizations.

- Inference - A conclusion or reasoning process. An implication, deduction, supposition or the act of conjecture, assumption and/or presumption.

- Informal essay - An essay that breaks the more formal academic rules when it comes to essay writing, usually for a creative reason, to make a more human-based or emotional point, or to make the text more interesting to read for the target audience.

- Introduction - The text found at a start of an essay that helps the reader understand what the essay is about in general terms and if the reader will be interested in the essay content.

- Irony - A form of humor that suggests the opposite of a literal meaning. Humor based on incongruity or based on contradiction.

- ISBN - In publishing it is the International Standard Book Number and is used to catalog publications in a similar way that barcodes catalog groceries. It is a library specifically for publications.

- Jargon - Specialist language used by groups, companies or a culture that means something to both those within the group/company/culture and others.

- Lab Report - The details of work done in a lab that may be used later as evidence or for the basis of analysis.

- Levels of thought - What is focused upon in academics and to what degree it should be focused on.

- Linking word - They help create longer sentences whilst maintaining fluency. They may show a relationship between points or ideas.

- Literature essay - An essay written to inform the reader or to deliver a message to the essay reader.

- Literature research - The use of credible and respected resource during the research process.

- Loaded words - High inference language that helps direct a thought or conclusion in the mind of a reader. It may evoke a stereotype or emotion with its use where another just as suitable word wouldn’t.

- Logical fallacy - An error in reasoning especially related to correct and incorrect logic.

- m-dash - Used to show that a word continues on to the next line. It may also be used to create a strong break in the structure of a sentence.

- Margin - The space between one element and another. Most commonly used in essays to specify where the page edge should sit and where the text should begin.

- Marker - An indicator usually used to indicate a position or presence.

- Meta-Analysis - The use of a statistical approach that combines results from multiple studies to increase the result‘s power over individual studies or improve estimates.

- Metaphor - It is an implicit comparison or the use of figurative language. It is an implicit comparison to describe somebody or something. It may be a vivid comparison that is not meant literally. Figurative language involves symbolism or figures of speech that are not literally supposed to represent real things.

- Methodology - An organizing system or the study of organizing principles or rules.

- MLA style - This is the style used by the Modern Language Association. People use them for the preparation of research and scholarly manuscripts.

- MS - This may represent the company Microsoft, or Master Of Science degree. It may also mean Middle School, Medical Student, Mass Storage or Management System.

- n-dash - A wider version of the em-dash or m-dash. It is used to connect words such as the use of the dash between N and dash within n-dash.

- Narrative essay - This is an essay that has a clear narrative. It is usually written in the first person to this end.

- Non sequitur - Purely defined it means that something doesn’t follow the set pattern, but usually refers to an incongruous statement or an unwarranted conclusion that secure doesn’t follow from its premise(s).

- Norm - A standard pattern of behavior that is usually set within a culture or a group. It may also describe usual behavior.

- Objective writing - Writing that can be verified through facts and evidence and is less biased than subjective writing.

- Organization - The coordination of components into a single structure or unit.

- Outline - A plan for an essay or a summary used as a guide for an essay.

- Overview - A summary of the main points of a piece of work, or a broad survey.

- Pacing - In terms of written work, it is the rate at which the reader is taken from one element/point/section/idea to another.

- Paper - In academic terms it usually refers to an essay or a piece of academic work.

- Paradox - Something that seems right but is actually wrong, or something that seems wrong but is actually right. It may be absurd or a contradiction that either proves itself to be correct, or is seemingly correct.

- Paragraph - A way of breaking up a piece of work into readable chunks whilst maintaining a similar theme, idea or point.

- Parallelism - A parallel state or the deliberate repetition of sentence structures or words for a desired effect.

- Paraphrase - To rephrase something in a way that keeps its meaning, but also adapts it to fit the work it is being inserted into. It often takes heavily from the original source, which means it should be noted as a quotation rather than a general reference.

- Parody - A copy or inferior copy of something. It may be copied in a comical or satirical way.

- Peer Review - An evaluation by experts, usually experts within relevant fields.

- Personal essay - An essay that may be conversational in nature, or may feature elements of the writer’s life or opinions. It may be autobiographical non-fiction, creative non-fiction, or works of a personal nature where all facts are not verifiable.

- Personification - The embodiment of something or the representation of an abstract quality being human.

- Persuasive essay - An essay that works to either reaffirm the reader’s belief/ideas, or to change the readers thinking from one way to another.

- Plagiarism - The copying or rewriting of the work of another person. Even a cleverly rewritten piece of work is still plagiarized, it is just harder to detect than written content that is copied verbatim.

- Post hoc, ergo propter hoc - This is a logical error. It may involve stating that an effect created a cause, which is usually incorrect outside of the physics and/or mathematics field.

- Prewriting - Preparatory work done before writing. Academics often write notes and a plan prior to writing an academic piece of work.

- Process analysis - Writing that gives instructions on how something is done. It is an organizational form of writing that exposes processes and is often seen within self-help papers/books.