Causes and Effects of Animal Cruelty

What are the causes and effects of animal cruelty? What is the impact of animal abuse on the environment and society? How to stop it? Find the answers below.

- Presentation of the Problem

Animal abuse means acts of neglect or violence that cause the pain and suffering of domestic and wild animals. With the development of modern civilization, this problem and the attention to it have been continuously increasing. According to Tanner (2015), today, “condemnation of cruelty to animals is virtually unanimous” (p. 818). Despite the public disapproval of animal abuse, little is being done when the cases occur. Moreover, numerous acts of animal neglect are not generally considered as cruel due to the lack of awareness in society. Therefore, it is vitally important to understand the negative impact of animal maltreatment on society, particular individuals, and the animals to realize the seriousness of the problem and take decisive actions.

Impact & Causes of Animal Abuse: Presentation of the Problem

Humans stand in the most dominating position among all the species of Planet Earth. They are the ones who run farms, circuses and decide whether to buy, adopt, or abandon a pet. The influence of humans has even spread onto wild animals as they can kill them while hunting or destroy their environment. According to Cooper (2018), domestic animals and pets exist exclusively at human mercy. However, this should not mean that people are free to do anything they want to animals, but, instead, signifies the responsibility of humans for treating animals properly. Although the use of farm animals for food, leather, and fur is not considered cruel by most of society, the practices that provoke unnecessary suffering and pain should not be tolerated.

It should be mentioned that animal maltreatment commonly appears in two forms – passive and active. Passive cruelty is the act of making animals suffer without vicious motives, usually for commercial purposes. Hurting animals in such a way does not imply aggression from humans; nevertheless, such acts show irresponsibility from people in their attitude to animals. This type of animal cruelty comprises such phenomena as inhumane farming, training animals for entertainment shows, neglect, starvation, and abandonment. Acts of animal maltreatment are considered illegal in the US. However, they often happen throughout the country as it is difficult to prove them and to find out who is guilty.

As the reasons for passive cruelty often lie in ignorance or indifference, active cruelty means deliberate and aggressive actions against animals to hurt and torture them. Acts of violence against animals are studied more thoroughly by scholars from various fields of study as they touch different aspects of social life such as psychology, psychiatry, education studies, and criminalistics. Cruelty as a psychological issue, especially at a young age, is a subject of concern for parents and teachers, as such acts speak for psychical disorders.

Animal Cruelty Causes

The history of relationships between humans and animals is thousands of years long. Our predecessors used animals for food and work as we do now, but initially, this use was motivated by necessity. Today, people are not as much dependent on animals, as there are various sources of food, and they do not need to put animals to work as machines are more effective than horses or oxen. Despite this, the exploitation of animals has only increased with the development of civilization. The question is, what makes people act cruelly towards animals if it is not a necessity.

Several reasons cause people to be cruel to animals today. First of all, commercial motives should be mentioned as the desire to maximize profit from farming leads to animal exploitation, such as factory farming. Testing products on animals is also a step in pursuit of commercial goals. Entertaining shows with animals, such as circuses or bullfighting, were initially present in many cultures. However, the main reason that they are still present despite the modern-day awareness is that they bring money.

Secondly, ignorance and indifference are the reasons that mostly cause violence towards pets. Some people use cruel types of training or inhumane procedures such as declawing of cats without knowing that they hurt their pets. Other people do not care about pets and neglect them. For example, they can leave a cat or a dog at home alone for several days without food and water, or leave them freezing outside at night. Irresponsible treatment is illegal and should be punished, but such cases are rarely reported.

Sheer aggression is probably the most clamant reason for cruelty to animals. Psychologists who study the nature of delinquent behavior claim that there is no specific type of aggression aimed at animals. As Hoffer, Hargreaves-Company, Muirhead, and Meloy (2018) claim, it is possible to predict the violence to humans by assessing the abuse of young people to animals. Their research shows that, in most cases, animals become victims only because they are weaker and cannot protect themselves from human rudeness.

Animal Cruelty Effects

From the ethical point of view, cruelty to animals should not be tolerated. It is illegal to make animals feel pain or suffer, and it should be punished. However, punishment, as it is rare and weak, is not a deterrent to animal abuse. That is why the awareness should be raised about the effect of cruelty to animals on society. After taking the first look at commercial maltreatment of animals, it seems that there is no negative influence on society, as people seem only to benefit from it.

Nonetheless, factory farming can lead to the transmission of infections among animals. Such outbreaks of diseases transmitted through products of animal origin are registered in the US almost every year. In addition to this, the exploitation of animals, especially with entertaining purposes, leads to cultural and ethical degradation of society.

Indifference and ignorance of pets can have disastrous outcomes for them, as in the result of such treatment, many of them die, starve or become abandoned. Children, raised in families where cruelty to animals is tolerated, have the perception that it is a norm and are likely to continue this tradition. As a result of abandonment, cities are flooded with stray animals, which negatively influence the welfare of residents.

Psychologists say that there is a direct link between violence to animals and people (Bright et al., 2018). Deliberate, aggressive behavior to animals has been self-reported by numbers of juvenile offenders, as the study shows. According to Bright, Huq, Applebaum, and Hardt, animal abuse is a sign of delinquency: “Compared to the larger group of juvenile offenders, the children admitting to engaging in animal cruelty are younger at the time of the first arrest” (p. 287). Reporting and assessing such incidents is necessary, as it can serve for prediction and prevention of further aggression against humans.

The analysis of the effect cruelty to animals has on the society shows that there are numerous negative consequences of such acts, as there are no animal abuse cases that have absolutely no outcomes. The effects on humans are different, but the effect on animals is always the same – creatures capable of affection and devotion are suffering and dying. Viewing animals only as objects can not lead to effective and happy co-existence, whereas compassion and care provide mutual gain.

Bright, M. A., Huq, M. S., Spencer, T., Applebaum, J. W., & Hardt, N. (2018). Animal cruelty as an indicator of family trauma: Using adverse childhood experiences to look beyond child abuse and domestic violence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 76 , 287–296. Web.

Cooper, D. E. (2018). Animals and misanthropy . London, UK: Routledge.

Hoffer, T., Hargreaves-Company, H., Muirhead, Y., & Meloy, J. R. (2018). Violence in animal cruelty offenders. New York, NY: Springer Nature.

Tanner, J. (2015). Clarifying the concept of cruelty: What makes cruelty to animals cruel. The Heythrop Journal, 56 (5), 818–835. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, December 3). Causes and Effects of Animal Cruelty. https://ivypanda.com/essays/cruelty-to-animals-causes-and-effects/

"Causes and Effects of Animal Cruelty." IvyPanda , 3 Dec. 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/cruelty-to-animals-causes-and-effects/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'Causes and Effects of Animal Cruelty'. 3 December.

IvyPanda . 2019. "Causes and Effects of Animal Cruelty." December 3, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/cruelty-to-animals-causes-and-effects/.

1. IvyPanda . "Causes and Effects of Animal Cruelty." December 3, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/cruelty-to-animals-causes-and-effects/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Causes and Effects of Animal Cruelty." December 3, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/cruelty-to-animals-causes-and-effects/.

- Historical Maltreatment of Psychiatric Inpatients

- Animal Cruelty as an Ethical and Moral Problem

- Selling Pets and Pets’ Products: The Ethical Considerations Raised.

- The Main Causes of Youth Violence

- The Problem of Overpopulation

- Procrastination Essay

- Cultural Identity: Problems, Coping, and Outcomes

- Butterfly Effect with Premarital Sex

Animal cruelty facts and stats

What to know about animal abuse victims and legislative trends

The shocking number of animal cruelty cases reported every day is just the tip of the iceberg—most cases are never reported. Unlike violent crimes against people, cases of animal abuse are not compiled by state or federal agencies, making it difficult to calculate just how common they are. However, we can use the information that is available to try to understand and prevent cases of abuse.

Who abuses animals?

Cruelty and neglect cross all social and economic boundaries and media reports suggest that animal abuse is common in both rural and urban areas.

- Intentional cruelty to animals is strongly correlated with other crimes, including violence against people.

- Hoarding behavior often victimizes animals. Sufferers of a hoarding disorder may impose severe neglect on animals by housing far more than they are able to adequately take care of. Serious animal neglect (such as hoarding) is often an indicator of people in need of social or mental health services.

- Surveys suggest that those who intentionally abuse animals are predominantly men under 30, while those involved in animal hoarding are more likely to be women over 60.

Most common victims

The animals whose abuse is most often reported are dogs, cats, horses and livestock . Undercover investigations have revealed that animal abuse abounds in the factory farm industry. But because of the weak protections afforded to livestock under state cruelty laws, only the most shocking cases are reported, and few are ever prosecuted.

Organized cruelty

Dogfighting, cockfighting and other forms of organized animal cruelty go hand in hand with other crimes, and continues in many areas of the United States due to public corruption.

- The HSUS documented uniformed police officers at a cockfighting pit in Kentucky.

- The U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency has prosecuted multiple cases where drug cartels were running narcotics through cockfighting and dogfighting operations.

- Dozens of homicides have occurred at cockfights and dogfights.

- A California man was killed in a disagreement about a $10 cockfight bet .

The HSUS’s investigative team combats complacent public officials and has worked with the FBI on public corruption cases in Tennessee and Virginia. In both instances, law enforcement officers were indicted and convicted.

Correlation with domestic violence

Data on domestic violence and child abuse cases reveal that a staggering number of animals are targeted by those who abuse their children or spouses.

- There are approximately 70 million pet dogs and 74.1 million pet cats in the U.S. where 20 men and women are assaulted per minute (an average of around 10 million a year).

- In one survey, 71 % of domestic violence victims reported that their abuser also targeted pets.

- In one study of families under investigation for suspected child abuse, researchers found that pet abuse had occurred in 88 % of the families under supervision for physical abuse of their children.

To put a stop to this pattern of violence, the Humane Society Legislative Fund supported the Pets and Women’s Safety (PAWS) Act, introduced to Congress in 2015 as H.R. 1258 and S.B. 1559 and enacted as part of the farm bill passed by Congress and signed by President Trump in 2018. Once fully enacted, the PAWS Act helps victims of domestic abuse find the means to escape their abusers while keeping their companion animals safe—many victims remain in abusive households for fear of their pets’ safety.

State legislative trends

The HSUS has long led the push for stronger animal cruelty laws and provides training for law officials to detect and prosecute these crimes. With South Dakota joining the fight in March of 2014, animal cruelty laws now include felony provisions in all 50 states.

First vs. subsequent offense

Given that a fraction of animal cruelty acts are reported or successfully prosecuted, we are committed to supporting felony convictions in cases of severe cruelty.

- 49 states have laws to provide felony penalties for animal torture on the first offense.

- Only Iowa doesn’t have such a law.

- Animal cruelty laws typically cover intentional and egregious animal neglect and abuse.

Changes in federal tracking

On January 1, 2016, the FBI added cruelty to animals as a category in the Uniform Crime Report , a nationwide crime reporting system commonly used in homicide investigations. While only about a third of U.S. communities currently participate in the system, the data generated will help create a clearer picture of animal abuse and guide strategies for intervention and enforcement. Data collection covers four categories: simple/gross neglect, intentional abuse and torture, organized abuse (such as dogfighting and cockfighting) and animal sexual abuse.

We never know where disasters will strike or when animals may be in need of rescue, but we know we must be ready. Donate today to support all our lifesaving work.

Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

102 Cruelty to Animals Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

Title: 102 Cruelty to Animals Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Introduction:

Cruelty to animals is a distressing global issue that requires immediate attention. Writing an essay on this topic raises awareness, educates readers, and encourages them to take action against animal abuse. In this article, we present 102 cruelty to animals essay topic ideas and examples to help students, writers, and activists express their thoughts effectively.

- The impact of factory farming on animal welfare.

- The psychological consequences of animal cruelty on children.

- Animal experimentation: Finding alternative methods for scientific research.

- The connection between animal abuse and domestic violence.

- The role of the media in exposing and preventing animal cruelty.

- The ethical implications of using animals in entertainment industries.

- The importance of stricter animal cruelty laws and their enforcement.

- The impact of illegal wildlife trade on endangered species.

- The correlation between animal abuse and serial killers.

- The role of education in preventing cruelty to animals.

- The use of animals in circuses: Should it be banned?

- The impact of climate change on animal habitats.

- The role of animal shelters in combating cruelty and providing care.

- The effectiveness of therapy animals in healing trauma.

- The psychological benefits of adopting pets from shelters.

- The role of zoos in conservation efforts and animal welfare.

- The connection between animal cruelty and psychological disorders.

- The ethical implications of using animals for fur and leather production.

- The impact of deforestation on wildlife and biodiversity.

- The consequences of illegal poaching on wildlife populations.

- The role of social media in raising awareness about animal cruelty.

- The impact of animal agriculture on greenhouse gas emissions.

- The ethical concerns surrounding animal testing in the cosmetic industry.

- The impact of puppy mills on animal health and well-being.

- The connection between animal cruelty and youth delinquency.

- The role of legislation in preventing animal cruelty.

- The consequences of animal abandonment and neglect.

- The impact of trophy hunting on endangered species.

- The ethical implications of using animals in fashion shows.

- The connection between animal cruelty and mental health disorders in abusers.

- The role of animal-assisted therapy in treating mental health conditions.

- The consequences of unethical breeding practices on animal health.

- The impact of dogfighting and cockfighting on animal welfare.

- The correlation between animal cruelty and elder abuse.

- The role of technology in preventing and reporting animal cruelty.

- The consequences of animal cruelty in the tourism industry.

- The ethical concerns surrounding horse racing and animal exploitation.

- The connection between animal cruelty and child abuse.

- The impact of invasive species on native wildlife.

- The consequences of animal cruelty in the entertainment industry.

- The role of animal rights organizations in combating cruelty.

- The ethical implications of using animals for scientific experiments.

- The connection between animal cruelty and gang activities.

- The impact of animal cruelty on ecosystems.

- The consequences of animal hoarding on animal welfare.

- The role of veterinary professionals in identifying and reporting animal abuse.

- The ethical concerns surrounding the use of animals in advertisements.

- The connection between animal cruelty and substance abuse.

- The impact of animal cruelty on wildlife tourism.

- The consequences of animal cruelty in the pet breeding industry.

- The role of artists in raising awareness about animal abuse.

- The ethical implications of using animals in rodeos.

- The connection between animal cruelty and school violence.

- The impact of animal cruelty on the extinction of endangered species.

- The consequences of animal cruelty in the fashion industry.

- The role of animal rescue organizations in saving and rehabilitating abused animals.

- The ethical concerns surrounding using animals for entertainment in theme parks.

- The connection between animal cruelty and hate crimes.

- The impact of animal cruelty on marine life.

- The consequences of animal cruelty in the fur trade industry.

- The role of animal therapy in supporting victims of trauma.

- The ethical implications of using animals in advertising campaigns.

- The connection between animal cruelty and mental health disorders in victims.

- The impact of animal cruelty on wildlife management practices.

- The consequences of animal cruelty in the exotic pet trade.

- The role of legislation in banning animal testing for cosmetics.

- The ethical concerns surrounding using animals for experimentation in laboratories.

- The connection between animal cruelty and human overpopulation.

- The impact of animal cruelty on the tourism industry.

- The consequences of animal cruelty in the food processing industry.

- The role of animal sanctuaries in providing refuge for abused animals.

- The ethical implications of using animals in television commercials.

- The connection between animal cruelty and social inequality.

- The impact of animal cruelty on species conservation efforts.

- The consequences of animal cruelty in the leather industry.

- The role of wildlife conservation organizations in preventing animal abuse.

- The ethical concerns surrounding using animals for military purposes.

- The connection between animal cruelty and poverty.

- The impact of animal cruelty on the destruction of natural habitats.

- The consequences of animal cruelty in the pet food industry.

- The role of social workers in identifying and addressing animal abuse cases.

- The ethical implications of using animals in magic shows.

- The connection between animal cruelty and human trafficking.

- The impact of animal cruelty on the spread of zoonotic diseases.

- The consequences of animal cruelty in the cosmetic industry.

- The role of animal-assisted interventions in improving mental health.

- The ethical concerns surrounding using animals for product testing.

- The connection between animal cruelty and environmental degradation.

- The impact of animal cruelty on eco-tourism.

- The role of animal welfare organizations in advocating for legislative changes.

- The ethical implications of using animals in theme parks.

- The connection between animal cruelty and social isolation.

- The impact of animal cruelty on the illegal wildlife trade.

- The consequences of animal cruelty in the circus industry.

- The role of veterinarians in reporting and preventing animal abuse.

- The ethical concerns surrounding using animals for military experiments.

- The connection between animal cruelty and addiction.

- The impact of animal cruelty on sustainable agriculture practices.

- The consequences of animal cruelty in the dairy industry.

- The role of law enforcement agencies in combating animal abuse.

- The ethical implications of using animals in rodeo events.

Conclusion:

Cruelty to animals is a pressing issue that demands attention at various levels. By discussing these 102 essay topic ideas and examples, individuals can raise awareness, promote empathy, and encourage action to protect animals from abuse. It is crucial to remember that every voice matters, and by joining forces, we can create a world where animals are treated with kindness, respect, and compassion.

Want to create a presentation now?

Instantly Create A Deck

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Hassle Free

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2023 Pitchgrade

Home — Essay Samples — Law, Crime & Punishment — Animal Cruelty — Understanding Animal Cruelty: Causes, Effects, and Prevention

Understanding Animal Cruelty: Causes, Effects, and Prevention

- Categories: Animal Cruelty

About this sample

Words: 659 |

Published: Jan 30, 2024

Words: 659 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, definition and types of animal cruelty, causes of animal cruelty, effects of animal cruelty, legislation and prevention, case studies and examples, a. psychological factors, b. societal factors, a. animal welfare, b. human society, a. animal protection laws, b. education and awareness.

- Animal Welfare Act. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Retrieved from https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/animalwelfare/ct_awa_overview

- The Link Between Animal Abuse and Human Violence. National Link Coalition. Retrieved from https://nationallinkcoalition.org/resources/resources-for-professionals/link-between-animal-abuse-and-human-violence/

- The Humane Methods of Livestock Slaughter Act. United States Department of Justice. Retrieved from https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/usao/legacy/2010/09/30/usab5706.pdf

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr Jacklynne

Verified writer

- Expert in: Law, Crime & Punishment

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 1012 words

1 pages / 445 words

6 pages / 2522 words

3 pages / 1286 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Animal Cruelty

Martinez, Diana Rowe. “Rodeo Animals Are Not Abused.” Greenhaven Press, 2004 and Gale 2001. 07 May 2001. Opposing Viewpoints Context. Accessed 27 Oct. 2019.O’Connor, Jennifer. “Animal Abuse at The Rodeo.” New York Times, 07, [...]

National Link Coalition. 'Prevention.' https://www.americanhumane.org/fact-sheet/animal-abuse/

Homeless Animals is an issue that continues to affect communities across the globe. This essay seeks to delve into the multifaceted problem of homeless animals, exploring its root causes, the challenges it poses, and the various [...]

Homeless Animals in America is a complex and pressing issue that demands our attention and concerted efforts. This essay will delve into the specific challenges and dimensions of the crisis of homeless animals in the United [...]

In this essay, I will be investigating why using animals for entertainment should be banned. It is essential that this issue is explored in more depth due to the increases in news reports outlining the effects of this practice. [...]

In “Consider the Lobster” David Foster Wallace is given the opportunity to write a review for a magazine, Gourmet. Which is meant to cover the Maine Lobster Festival held in the summer of 2003. However the review was nothing [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Essay on Animal Cruelty

Students are often asked to write an essay on Animal Cruelty in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Animal Cruelty

Understanding animal cruelty.

Animal cruelty is the act of causing harm to animals. This includes physical violence, neglect, or overwork. It’s a serious issue that needs our attention.

Forms of Animal Cruelty

Animal cruelty takes many forms. It can be as obvious as hitting an animal or as subtle as not providing them with proper food and shelter.

Effects of Animal Cruelty

Animal cruelty not only hurts animals, but it also affects our society. It teaches the wrong values to children and often escalates to violence against people.

Preventing Animal Cruelty

Preventing animal cruelty starts with education. We need to teach respect for all living things, and laws need to be enforced to protect animals.

Also check:

- 10 Lines on Animal Cruelty

- Speech on Animal Cruelty

250 Words Essay on Animal Cruelty

Introduction.

Animal cruelty, a pressing global issue, is the inhumane and brutal treatment inflicted upon animals. It manifests in various forms, such as physical abuse, neglect, and exploitation. This essay delves into the profound implications of this issue and emphasizes the urgent need for effective solutions.

The Prevalence of Animal Cruelty

The ubiquity of animal cruelty is alarming. From industrialized farming to illegal wildlife trade, animals are subjected to immense suffering. Factory farming, for instance, confines animals to cramped, unsanitary conditions, causing physical and psychological distress. Similarly, the illegal wildlife trade threatens biodiversity and subjects animals to cruel transportation and handling practices.

Implications of Animal Cruelty

The implications of animal cruelty extend beyond the immediate suffering of animals. It has environmental repercussions, contributing to biodiversity loss and ecosystem imbalance. Moreover, it signifies a societal moral crisis. The way a society treats its most vulnerable members, including animals, reflects its ethical and moral standards.

Addressing Animal Cruelty

Addressing animal cruelty necessitates a comprehensive approach. Legislation against animal abuse and stricter law enforcement are essential. Moreover, fostering empathy and respect for animals through education can shift societal attitudes towards them. Additionally, consumer choices can influence industry practices, promoting animal welfare.

In conclusion, animal cruelty is a pressing issue with far-reaching implications. It is a reflection of our societal values and has profound environmental impacts. Addressing it requires concerted efforts at legislative, educational, and individual levels. Ultimately, the fight against animal cruelty is a fight for a more compassionate and sustainable world.

500 Words Essay on Animal Cruelty

Animal cruelty is a pervasive issue that transcends borders, cultures, and socioeconomic statuses. It is a deliberate infliction of harm or suffering upon animals, a behavior that can be motivated by a range of factors, from cultural norms to psychological disorders. The issue is not only a concern for animal rights advocates but also for society at large, as it reflects deeper problems within our societal structures and attitudes.

The Forms of Animal Cruelty

Animal cruelty manifests in various forms, often categorized into two primary types: active and passive. Active cruelty involves direct harm or violence towards animals, such as physical abuse or purposeful neglect. Passive cruelty, on the other hand, is characterized by negligence, such as failing to provide adequate food, water, shelter, or medical care for pets.

Industrial animal farming represents a systemic form of animal cruelty. Animals are often confined to cramped, unsanitary conditions, subjected to painful procedures without anesthesia, and denied their natural behaviors. This is a form of institutionalized cruelty, often overlooked due to the demand for cheap and abundant meat.

Implications on Society

Animal cruelty is not an isolated issue; it has broader implications for society. Research has established a correlation between animal cruelty and violent crimes against humans, including domestic abuse and murder. The “Link” theory suggests that animal abuse can be an indicator of potential human violence, reflecting a lack of empathy and a propensity for inflicting harm.

Moreover, animal cruelty can have significant environmental implications. Industrial animal farming contributes significantly to greenhouse gas emissions, deforestation, and water pollution. Thus, addressing animal cruelty is not only a moral obligation but also a crucial aspect of our broader efforts towards environmental sustainability.

Legal and Ethical Considerations

Legally, animal cruelty is a crime in many jurisdictions, but the enforcement and penalties vary widely. The lack of stringent laws and effective enforcement mechanisms often leads to a culture of impunity, where perpetrators face minimal consequences.

Ethically, animal cruelty challenges our moral responsibility towards non-human beings. The philosophy of animal rights argues that animals, like humans, have interests that deserve recognition and protection. Consequently, any form of cruelty or exploitation is a violation of their basic rights, necessitating a shift in our attitudes and behaviors towards animals.

Animal cruelty is a complex and multifaceted issue that requires a comprehensive approach to address effectively. It is a reflection of our societal attitudes towards animals and often indicative of broader social and environmental issues. Increased awareness, stronger legal frameworks, and a shift in societal attitudes are crucial to combat animal cruelty. As a society, we must recognize and respect the inherent dignity and worth of all living beings and strive towards a more compassionate, humane world.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Animal Abuse

- Essay on Science Fiction

- Essay on Science Exhibition

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Footnote leads to exploration of start of for-profit prisons in N.Y.

Should NATO step up role in Russia-Ukraine war?

It’s on Facebook, and it’s complicated

They can think, feel pain, love. isn’t it time animals had rights.

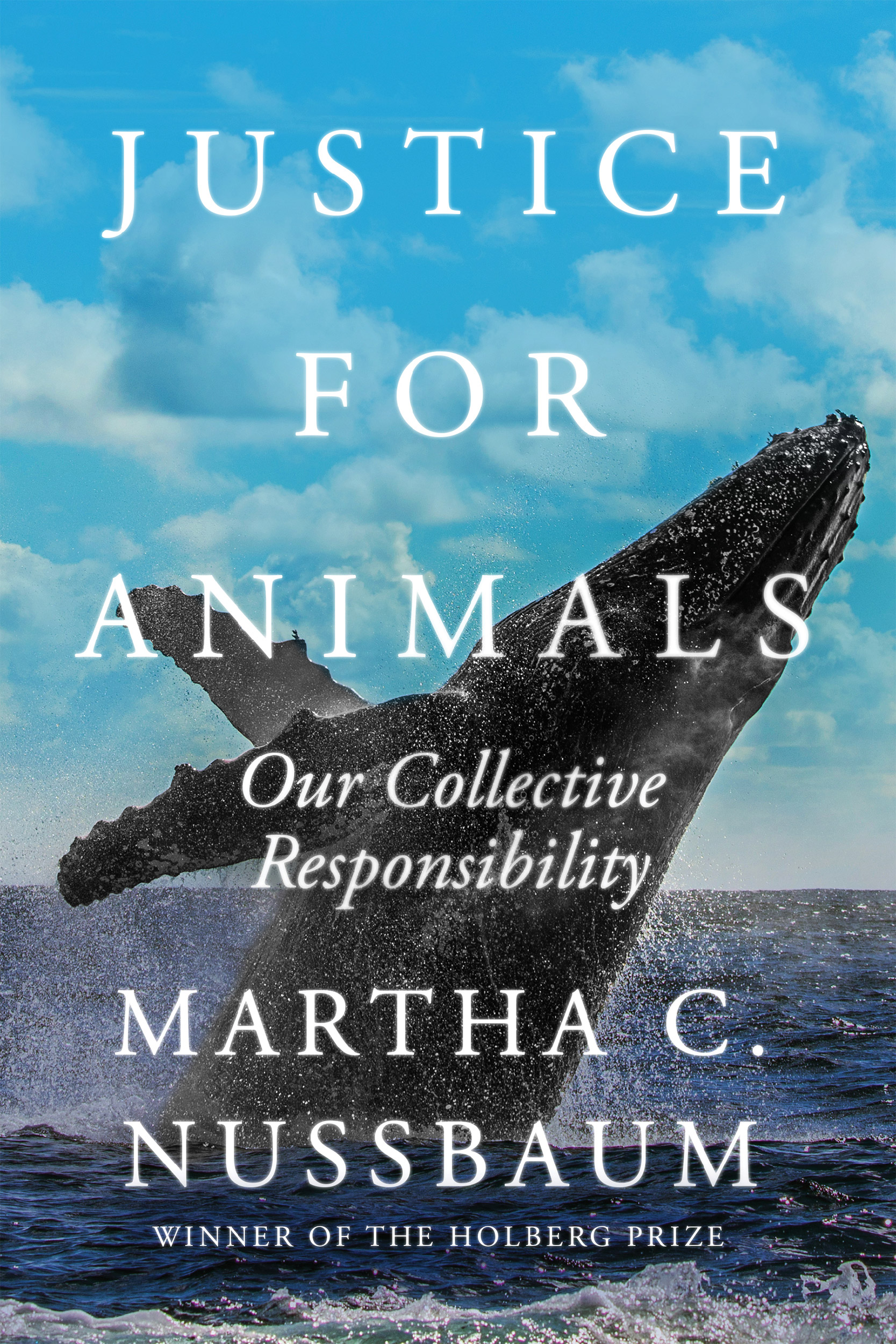

Martha Nussbaum lays out ethical, legal case in new book

Martha Nussbaum

Excerpted from “Justice for Animals: Our Collective Responsibility” by Martha C. Nussbaum, M.A. ’71, Ph.D. ’75

Animals are in trouble all over the world. Our world is dominated by humans everywhere: on land, in the seas, and in the air. No non-human animal escapes human domination. Much of the time, that domination inflicts wrongful injury on animals: whether through the barbarous cruelties of the factory meat industry, through poaching and game hunting, through habitat destruction, through pollution of the air and the seas, or through neglect of the companion animals that people purport to love.

In a way, this problem is age-old. Both Western and non-Western philosophical traditions have deplored human cruelty to animals for around two millennia. The Hindu emperor Ashoka (c. 304–232 bce), a convert to Buddhism, wrote about his efforts to give up meat and to forgo all practices that harmed animals. In Greece the Platonist philosophers Plutarch (46–119 ce) and Porphyry (c. 234–305 ce) wrote detailed treatises deploring human cruelty to animals, describing their keen intelligence and their capacity for social life, and urging humans to change their diet and their way of life. But by and large these voices have fallen on deaf ears, even in the supposedly moral realm of the philosophers, and most humans have continued to treat most animals like objects, whose suffering does not matter — although they sometimes make an exception for companion animals. Meanwhile, countless animals have suffered cruelty, deprivation, and neglect.

Because the reach of human cruelty has expanded, so too has the involvement of virtually all people in it. Even people who do not consume meat produced by the factory farming industry are likely to have used single-use plastic items, to use fossil fuels mined beneath the ocean and polluting the air, to dwell in areas in which elephants and bears once roamed, or to live in high-rise buildings that spell death for migratory birds. The extent of our own implication in practices that harm animals should make every person with a conscience consider what we can all do to change this situation. Pinning guilt is less important than accepting the fact that humanity as a whole has a collective duty to face and solve these problems.

So far, I have not spoken of the extinction of animal species, because this is a book about loss and deprivation suffered by individual creatures, each of whom matters. Species as such do not suffer loss. However, extinction never takes place without massive suffering of individual creatures: the hunger of a polar bear, starving on an ice floe, unable to cross the sea to hunt; the sadness of an orphan elephant, deprived of care and community as the species dwindles rapidly; the mass extinctions of song-bird species as a result of unbreathable air, a horrible death. When human practices hound species toward extinction, member animals always suffer greatly and live squashed and thwarted lives. Besides, the species themselves matter for creating diverse ecosystems in which animals can live well.

Extinctions would take place even without human intervention. Even in such cases we might have reasons to intervene to stop them, because of the importance of biodiversity. But scientists agree that today’s extinctions are between one thousand and ten thousand times higher than the natural extinction rate. (Our uncertainty is huge, because we are very ignorant of how many species there actually are, particularly where fish and insects are concerned.) Worldwide, approximately one-quarter of the world’s mammals and over 40 percent of amphibians are currently threatened with extinction. These include several species of bear, the Asian elephant (endangered), the African elephant (threatened), the tiger, six species of whale, the gray wolf, and so many more. All in all, more than 370 animal species are either endangered or threatened, using the criteria of the US Endangered Species Act, not including birds, and a separate list of similar length for birds. Asian songbirds are virtually extinct in the wild, on account of the lucrative trade in these luxury items. And many other species of birds have recently become extinct. Meanwhile, the international treaty called CITES that is supposed to protect birds (and many other creatures) is toothless and unenforced. The story of this book is not that story of mass extinction, but the sufferings of individual creatures that take place against this background of human indifference to biodiversity.

“The extent of our own implication in practices that harm animals should make every person with a conscience consider what we can all do to change this situation.”

There is a further reason why the ethical evasion of the past must end now. Today we know far more about animal lives than we did even 50 years ago. We know much too much for the glib excuses of the past to be offered without shame. Porphyry and Plutarch (and Aristotle before them) knew a lot about animal intelligence and sensitivity. But somehow humans find ways of “forgetting” what the science of the past has plainly revealed, and for many centuries most people, including most philosophers, thought animals were “brute beasts,” automata without a subjective sense of the world, without emotions, without society, and perhaps even without the feeling of pain.

Recent decades, however, have seen an explosion of high-level research covering all areas of the animal world. We now know more not only about animals long closely studied — primates and companion animals — but also about animals who are difficult to study — marine mammals, whales, fish, birds, reptiles, and cephalopods.

We know — not just by observation, but by carefully designed experimental work — that all vertebrates and many invertebrates feel pain subjectively, and have, more generally, a subjectively felt view of the world: the world looks like something to them. We know that all of these animals experience at least some emotions (fear being the most ubiquitous), and that many experience emotions like compassion and grief that involve more complex “takes” on a situation. We know that animals as different as dolphins and crows can solve complicated problems and learn to use tools to solve them. We know that animals have complex forms of social organization and social behavior. More recently, we have been learning that these social groups are not simply places where a rote inherited repertory is acted out, but places of complicated social learning. Species as different as whales, dogs, and many types of birds clearly transmit key parts of the species’ repertoire to their young socially, not just genetically.

What are the implications of this research for ethics? Huge, clearly. We can no longer draw the usual line between our own species and “the beasts,” a line meant to distinguish intelligence, emotion, and sentience from the dense life of a “brute beast.” Nor can we even draw a line between a group of animals we already recognize as sort of “like us” — apes, elephants, whales, dogs — and others who are supposed to be unintelligent. Intelligence takes multiple and fascinating forms in the real world, and birds, evolving by a very different path from humans, have converged on many similar abilities. Even an invertebrate such as the octopus has surprising capacities for intelligent perception: an octopus can recognize individual humans, and can solve complex problems, guiding one of its arms through a maze to obtain food using only its eyes. Once we recognize all this we can hardly be unchanged in our ethical thinking. To put a “brute beast” in a cage seems no more wrong than putting a rock in a terrarium. But that is not what we are doing. We are deforming the existence of intelligent and complexly sentient forms of life. Each of these animals strives for a flourishing life, and each has abilities, social and individual, that equip it to negotiate a decent life in a world that gives animals difficult challenges. What humans are doing is to thwart this striving — and this seems wrong.

But even though the time has come to recognize our ethical responsibility to the other animals, we have few intellectual tools to effect meaningful change. The third reason why we must confront what we are doing to animals now, today, is that we have built a world in which two of humanity’s best tools for progress, law and political theory, have, so far, no or little help to offer us. Law — both domestic and international — has quite a lot to say about the lives of companion animals, but very little to say about any other animals. Nor do animals in most nations have what lawyers call “standing”: that is, the status to bring a legal claim if they are wronged. Of course, animals cannot themselves bring a legal claim, but neither can most humans, including children, people with cognitive disabilities — and, to tell the truth, almost everybody, since people have little knowledge of the law. All of us need a lawyer to press our claims. But all the humans I have mentioned — including people with lifelong cognitive disabilities — count, and can bring a legal claim, assisted by an able advocate. The way we have designed the world’s legal systems, animals do not have this simple privilege. They do not count.

Law is built by humans using the theories they have. When those theories were racist, laws were racist. When theories of sex and gender excluded women, so too did law. And there is no denying that most political thought by humans the world over has been human-centered, excluding animals. Even the theories that purport to offer help in the struggle against abuse are deeply defective, built on an inadequate picture of animal lives and animal striving. As a philosopher and political theorist who is also deeply immersed in law and law teaching, I hope to change things with this book.

Copyright © 2022 by Martha Nussbaum. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Share this article

You might like.

Historian traces 19th-century murder case that brought together historical figures, helped shape American thinking on race, violence, incarceration

National security analysts outline stakes ahead of July summit

‘Spermworld’ documentary examines motivations of prospective parents, volunteer donors who connect through private group page

Epic science inside a cubic millimeter of brain

Researchers publish largest-ever dataset of neural connections

Pop star on one continent, college student on another

Model and musician Kazuma Mitchell managed to (mostly) avoid the spotlight while at Harvard

Finding right mix on campus speech policies

Legal, political scholars discuss balancing personal safety, constitutional rights, academic freedom amid roiling protests, cultural shifts

- Share full article

Opinion Guest Essay

Modern Zoos Are Not Worth the Moral Cost

Credit... Photographs by Peter Fisher for The New York Times

Supported by

By Emma Marris

Ms. Marris is an environmental writer and the author of the forthcoming book “Wild Souls: Freedom and Flourishing in the Non-Human World.”

- June 11, 2021

After being captives of the pandemic for more than a year, we have begun experiencing the pleasures of simple outings: dining al fresco, shopping with a friend, taking a stroll through the zoo. As we snap a selfie by the sea lions for the first time in so long, it seems worth asking, after our collective ordeal, whether our pleasure in seeing wild animals up close is worth the price of their captivity.

Throughout history, men have accumulated large and fierce animals to advertise their might and prestige. Power-mad men from Henry III to Saddam Hussein’s son Uday to the drug kingpin Pablo Escobar to Charlemagne all tried to underscore their strength by keeping terrifying beasts captive. William Randolph Hearst created his own private zoo with lions, tigers, leopards and more at Hearst Castle. It is these boastful collections of animals, these autocratic menageries, from which the modern zoo, with its didactic plaques and $15 hot dogs, springs.

The forerunners of the modern zoo, open to the public and grounded in science, took shape in the 19th century. Public zoos sprang up across Europe, many modeled on the London Zoo in Regent’s Park. Ostensibly places for genteel amusement and edification, zoos expanded beyond big and fearsome animals to include reptile houses, aviaries and insectariums. Living collections were often presented in taxonomic order, with various species of the same family grouped together, for comparative study.

The first zoos housed animals behind metal bars in spartan cages. But relatively early in their evolution, a German exotic animal importer named Carl Hagenbeck changed the way wild animals were exhibited. In his Animal Park, which opened in 1907 in Hamburg, he designed cages that didn’t look like cages, using moats and artfully arranged rock walls to invisibly pen animals. By designing these enclosures so that many animals could be seen at once, without any bars or walls in the visitors’ lines of sight, he created an immersive panorama, in which the fact of captivity was supplanted by the illusion of being in nature.

Mr. Hagenbeck’s model was widely influential. Increasingly, animals were presented with the distasteful fact of their imprisonment visually elided. Zoos shifted just slightly from overt demonstrations of mastery over beasts to a narrative of benevolent protection of individual animals. From there, it was an easy leap to protecting animal species.

The “educational day out” model of zoos endured until the late 20th century, when zoos began actively rebranding themselves as serious contributors to conservation. Zoo animals, this new narrative went, function as backup populations for wild animals under threat, as well as “ambassadors” for their species, teaching humans and motivating them to care about wildlife. This conservation focus “ must be a key component ” for institutions that want to be accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, a nonprofit organization that sets standards and policies for facilities in the United States and 12 other countries.

This is the image of the zoo I grew up with: the unambiguously good civic institution that lovingly cared for animals both on its grounds and, somehow, vaguely, in their wild habitats. A few zoos are famous for their conservation work. Four of the zoos and the aquarium in New York City, for instance, are managed by the Wildlife Conservation Society, which is involved in conservation efforts around the world. But this is not the norm.

While researching my book on the ethics of human interactions with wild species, “Wild Souls,” I examined how, exactly, zoos contribute to the conservation of wild animals.

A.Z.A. facilities report spending approximately $231 million annually on conservation projects. For comparison, in 2018, they spent $4.9 billion on operations and construction. I find one statistic particularly telling about their priorities: A 2018 analysis of the scientific papers produced by association members between 1993 and 2013 showed that just about 7 percent of them annually were classified as being about “biodiversity conservation.”

Zoos accredited by the A.Z.A. or the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria have studbooks and genetic pedigrees and carefully breed their animals as if they might be called upon at any moment to release them, like Noah throwing open the doors to the ark, into a waiting wild habitat. But that day of release never quite seems to come.

There are a few exceptions. The Arabian oryx, an antelope native to the Arabian Peninsula, went extinct in the wild in the 1970s and then was reintroduced into the wild from zoo populations. The California condor breeding program, which almost certainly saved the species from extinction, includes five zoos as active partners. Black-footed ferrets and red wolves in the United States and golden lion tamarins in Brazil — all endangered, as well — have been bred at zoos for reintroduction into the wild. An estimated 20 red wolves are all that remain in the wild.

The A.Z.A. says that its members host “more than 50 reintroduction programs for species listed as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act.” Nevertheless, a vast majority of zoo animals (there are 800,000 animals of 6,000 species in the A.Z.A.’s zoos alone ) will spend their whole lives in captivity, either dying of old age after a lifetime of display or by being culled as “surplus.”

The practice of killing “surplus” animals is kept quiet by zoos, but it happens, especially in Europe. In 2014, the director of the E.A.Z.A. at the time estimated that between 3,000 and 5,000 animals are euthanized in European zoos each year. (The culling of mammals specifically in E.A.Z.A. zoos is “usually not more than 200 animals per year,” the organization said.) Early in the pandemic, the Neumünster Zoo in northern Germany coolly announced an emergency plan to cope with lost revenue by feeding some animals to other animals, compressing the food chain at the zoo like an accordion, until in the worst-case scenario, only Vitus, a polar bear, would be left standing. The A.Z.A.’s policies allow for the euthanasia of animals, but the president of the association, Dan Ashe, told me, “it’s very rarely employed” by his member institutions.

Mr. Ashe, a former director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, suggested that learning how to breed animals contributes to conservation in the long term, even if very few animals are being released now. A day may come, he said, when we need to breed elephants or tigers or polar bears in captivity to save them from extinction. “If you don’t have people that know how to care for them, know how to breed them successfully, know how to keep them in environments where their social and psychological needs can be met, then you won’t be able to do that,” he said.

The other argument zoos commonly make is that they educate the public about animals and develop in people a conservation ethic. Having seen a majestic leopard in the zoo, the visitor becomes more willing to pay for its conservation or vote for policies that will preserve it in the wild. What Mr. Ashe wants visitors to experience when they look at the animals is a “sense of empathy for the individual animal, as well as the wild populations of that animal.”

I do not doubt that some people had their passion for a particular species, or wildlife in general, sparked by zoo experiences. I’ve heard and read some of their stories. I once overheard two schoolchildren at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo in Washington confess to each other that they had assumed that elephants were mythical animals like unicorns before seeing them in the flesh. I remember well the awe and joy on their faces, 15 years later. I’d like to think these kids, now in their early 20s, are working for a conservation organization somewhere. But there’s no unambiguous evidence that zoos are making visitors care more about conservation or take any action to support it. After all, more than 700 million people visit zoos and aquariums worldwide every year, and biodiversity is still in decline.

In a 2011 study , researchers quizzed visitors at the Cleveland, Bronx, Prospect Park and Central Park zoos about their level of environmental concern and what they thought about the animals. Those who reported “a sense of connection to the animals at the zoo” also correlated positively with general environmental concern. On the other hand, the researchers reported, “there were no significant differences in survey responses before entering an exhibit compared with those obtained as visitors were exiting.”

A 2008 study of 206 zoo visitors by some members of the same team showed that while 42 percent said that the “main purpose” of the zoo was “to teach visitors about animals and conservation,” 66 percent said that their primary reason for going was “to have an outing with friends or family,” and just 12 percent said their intention was “to learn about animals.”

The researchers also spied on hundreds of visitors’ conversations at the Bronx Zoo, the Brookfield Zoo outside Chicago and the Cleveland Metroparks Zoo. They found that only 27 percent of people bothered to read the signs at exhibits. More than 6,000 comments made by the visitors were recorded, nearly half of which were “purely descriptive statements that asserted a fact about the exhibit or the animal.” The researchers wrote , “In all the statements collected, no one volunteered information that would lead us to believe that they had an intention to advocate for protection of the animal or an intention to change their own behavior.”

People don’t go to zoos to learn about the biodiversity crisis or how they can help. They go to get out of the house, to get their children some fresh air, to see interesting animals. They go for the same reason people went to zoos in the 19th century: to be entertained.

A fine day out with the family might itself be justification enough for the existence of zoos if the zoo animals are all happy to be there. Alas, there’s plenty of heartbreaking evidence that many are not.

In many modern zoos, animals are well cared for, healthy and probably, for many species, content. Zookeepers are not mustache-twirling villains. They are kind people, bonded to their charges and immersed in the culture of the zoo, in which they are the good guys.

But many animals clearly show us that they do not enjoy captivity. When confined they rock, pull their hair and engage in other tics. Captive tigers pace back and forth, and in a 2014 study, researchers found that “the time devoted to pacing by a species in captivity is best predicted by the daily distances traveled in nature by the wild specimens.” It is almost as if they feel driven to patrol their territory, to hunt, to move, to walk a certain number of steps, as if they have a Fitbit in their brains.

The researchers divided the odd behaviors of captive animals into two categories: “impulsive/compulsive behaviors,” including coprophagy (eating feces), regurgitation, self-biting and mutilation, exaggerated aggressiveness and infanticide, and “stereotypies,” which are endlessly repeated movements. Elephants bob their heads over and over. Chimps pull out their own hair. Giraffes endlessly flick their tongues. Bears and cats pace. Some studies have shown that as many as 80 percent of zoo carnivores, 64 percent of zoo chimps and 85 percent of zoo elephants have displayed compulsive behaviors or stereotypies.

Elephants are particularly unhappy in zoos, given their great size, social nature and cognitive complexity. Many suffer from arthritis and other joint problems from standing on hard surfaces; elephants kept alone become desperately lonely; and all zoo elephants suffer mentally from being cooped up in tiny yards while their free-ranging cousins walk up to 50 miles a day. Zoo elephants tend to die young. At least 20 zoos in the United States have already ended their elephant exhibits in part because of ethical concerns about keeping the species captive.

Many zoos use Prozac and other psychoactive drugs on at least some of their animals to deal with the mental effects of captivity. The Los Angeles Zoo has used Celexa, an antidepressant, to control aggression in one of its chimps. Gus, a polar bear at the Central Park Zoo, was given Prozac as part of an attempt to stop him from swimming endless figure-eight laps in his tiny pool. The Toledo Zoo has dosed zebras and wildebeest with the antipsychotic haloperidol to keep them calm and has put an orangutan on Prozac. When a female gorilla named Johari kept fighting off the male she was placed with, the zoo dosed her with Prozac until she allowed him to mate with her. A 2000 survey of U.S. and Canadian zoos found that nearly half of respondents were giving their gorillas Haldol, Valium or another psychopharmaceutical drug.

Some zoo animals try to escape. Jason Hribal’s 2010 book, “Fear of the Animal Planet,” chronicles dozens of attempts. Elephants figure prominently in his book, in part because they are so big that when they escape it generally makes the news.

Mr. Hribal documented many stories of elephants making a run for it — in one case repairing to a nearby woods with a pond for a mud bath. He also found many examples of zoo elephants hurting or killing their keepers and evidence that zoos routinely downplayed or even lied about those incidents.

Elephants aren’t the only species that try to flee a zoo life. Tatiana the tiger, kept in the San Francisco Zoo, snapped one day in 2007 after three teenage boys had been taunting her. She somehow got over the 12-foot wall surrounding her 1,000-square-foot enclosure and attacked one of the teenagers, killing him. The others ran, and she pursued them, ignoring all other humans in her path. When she caught up with the boys at the cafe, she mauled them before she was shot to death by the police. Investigators found sticks and pine cones inside the exhibit, most likely thrown by the boys.

Apes are excellent at escaping. Little Joe, a gorilla, escaped from the Franklin Park Zoo in Boston twice in 2003. At the Los Angeles Zoo, a gorilla named Evelyn escaped seven times in 20 years. Apes are known for picking locks and keeping a beady eye on their captors, waiting for the day someone forgets to lock the door. An orangutan at the Omaha Zoo kept wire for lock-picking hidden in his mouth. A gorilla named Togo at the Toledo Zoo used his incredible strength to bend the bars of his cage. When the zoo replaced the bars with thick glass, he started methodically removing the putty holding it in. In the 1980s, a group of orangutans escaped several times at the San Diego Zoo. In one escape, they worked together: One held a mop handle steady while her sister climbed it to freedom. Another time, one of the orangutans, Kumang, learned how to use sticks to ground the current in the electrical wire around her enclosure. She could then climb the wire without being shocked. It is impossible to read these stories without concluding that these animals wanted out .

“I don’t see any problem with holding animals for display,” Mr. Ashe told me. “People assume that because an animal can move great distances that they would choose to do that.” If they have everything they need nearby, he argued, they would be happy with smaller territories. And it is true that the territory size of an animal like a wolf depends greatly on the density of resources and other wolves. But then there’s the pacing, the rocking. I pointed out that we can’t ask animals whether they are happy with their enclosure size. “That’s true,” he said. “There is always that element of choice that gets removed from them in a captive environment. That’s undeniable.” His justification was philosophical. In the end, he said, “we live with our own constraints.” He added, “We are all captive in some regards to social and ethical and religious and other constraints on our life and our activities.”

What if zoos stopped breeding all their animals, with the possible exception of any endangered species with a real chance of being released back into the wild? What if they sent all the animals that need really large areas or lots of freedom and socialization to refuges? With their apes, elephants, big cats, and other large and smart species gone, they could expand enclosures for the rest of the animals, concentrating on keeping them lavishly happy until their natural deaths. Eventually, the only animals on display would be a few ancient holdovers from the old menageries, animals in active conservation breeding programs and perhaps a few rescues.

Such zoos might even be merged with sanctuaries, places that take wild animals that because of injury or a lifetime of captivity cannot live in the wild. Existing refuges often do allow visitors, but their facilities are really arranged for the animals, not for the people. These refuge-zoos could become places where animals live. Display would be incidental.

Such a transformation might free up some space. What could these zoos do with it, besides enlarging enclosures? As an avid fan of botanical gardens, I humbly suggest that as the captive animals retire and die off without being replaced, these biodiversity-worshiping institutions devote more and more space to the wonderful world of plants. Properly curated and interpreted, a well-run garden can be a site for a rewarding “outing with friends or family,” a source of education for the 27 percent of people who read signs and a point of civic pride.

I’ve spent many memorable days in botanical gardens, completely swept away by the beauty of the design as well as the unending wonder of evolution — and there’s no uneasiness or guilt. When there’s a surplus, you can just have a plant sale.

Emma Marris is an environmental writer and the author of the forthcoming book “Wild Souls: Freedom and Flourishing in the Non-Human World.”

Photographs by Peter Fisher. Mr. Fisher is a photographer based in New York.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here’s our email: [email protected] .

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram .

Advertisement

Find anything you save across the site in your account

What Would It Mean to Treat Animals Fairly?

By Elizabeth Barber

A few years ago, activists walked into a factory farm in Utah and walked out with two piglets. State prosecutors argued that this was a crime. That they were correct was obvious: The pigs were the property of Smithfield Foods, the largest pork producer in the country. The defendants had videoed themselves committing the crime; the F.B.I. later found the piglets in Colorado, in an animal sanctuary.

The activists said they had completed a “rescue,” but Smithfield had good reason to claim it hadn’t treated the pigs illegally. Unlike domestic favorites like dogs, which are protected from being eaten, Utah’s pigs are legally classified as “livestock”; they’re future products, and Smithfield could treat them accordingly. Namely, it could slaughter the pigs, but it could also treat a pig’s life—and its temporary desire for food, space, and medical help—as an inconvenience, to be handled in whatever conditions were deemed sufficient.

In their video, the activists surveyed those conditions . At the facility—a concentrated animal-feeding operation, or CAFO —pregnant pigs were confined to gestation crates, metal enclosures so small that the sows could barely lie down. (Smithfield had promised to stop using these crates, but evidently had not.) Other pigs were in farrowing crates, where they had enough room to lie down but not enough to turn their bodies around. When the activists approached one sow, they found dead piglets rotting beneath her. Nearby, they found two injured piglets, whom they decided to take. One couldn’t walk because of a foot infection; the other’s face was covered in blood. According to Smithfield, which denied mistreating animals, the piglets were each worth about forty-two dollars, but both had diarrhea and other signs of illness. This meant they were unlikely to survive, and that their bodies would be discarded, just as millions of farm animals are discarded each year.

During the trial, the activists reiterated that, yes, they entered Smithfield’s property and, yes, they took the pigs. And then, last October, the jury found them not guilty. In a column for the Times , one of the activists—Wayne Hsiung, the co-founder of Direct Action Everywhere—described talking to one of the jurors, who said that it was hard to convict the activists of theft, given that the sick piglets had no value for Smithfield. But another factor was the activists’ appeal to conscience. In his closing statement, Hsiung, a lawyer who represented himself, argued that an acquittal would model a new, more compassionate world. He had broken the law, yes—but the law, the jury seemed to agree, might be wrong.

A lot has changed in our relationship with animals since 1975, when the philosopher Peter Singer wrote “ Animal Liberation ,” the book that sparked the animal-rights movement. Gestation crates, like the ones in Utah, are restricted in the European Union, and California prohibits companies that use them from selling in stores, a case that the pork industry fought all the way to the Supreme Court—and lost. In a 2019 Johns Hopkins survey, more than forty per cent of respondents wanted to ban new CAFO s. In Iowa, which is the No. 1 pork-producing state, my local grocery store has a full Vegan section. “Vegan” is also a shopping filter on Sephora, and most of the cool-girl brands are vegan, anyway. Wearing fur is embarrassing.

And yet Singer’s latest book, “ Animal Liberation Now ,” a rewrite of his 1975 classic, is less a celebratory volume than a tragic one—tragic because it is very similar to the original in refrain, which is that, big-picture-wise, the state of animal life is terrible. “The core argument I was putting forward,” Singer writes, “seemed so irrefutable, so undeniably right, that I thought everyone who read it would surely be convinced by it.” Apparently not. By some estimates, scientists in the U.S. currently use roughly fifteen million animals for research, including mice, rats, cats, dogs, birds, and nonhuman primates. As in the seventies, much of this research tries to model psychological ailments, despite scientists’ having written for decades that more research is needed to figure out whether animals—and which kind of animals—provide a useful analogue for mental illness in humans. When Singer was first writing, a leading researcher created psychopathic monkeys by raising them in isolation, impregnating them with what he called a “rape rack,” and studying how the mothers bashed their infants’ heads into the ground. In 2019, researchers were still putting animals through “prolonged stress”—trapping them in deep water, restraining them for long periods while subjecting them to the odor of a predator—to see if their subsequent behavior evidenced P.T.S.D. (They wrote that more research was needed.) Meanwhile, factory farms, which were newish in 1975, have swept the globe. Just four per cent of Americans are vegetarian, and each year about eighty-three billion animals are killed for food.

It’s for these animals, Singer writes, “and for all the others who will, unless there is a sudden and radical change, suffer and die,” that he writes this new edition. But Singer’s hopes are by now tempered. One obvious problem is that, in the past fifty years, the legal standing of animals has barely changed. The Utah case was unusual not just because of the verdict but because referendums on farm-animal welfare seldom occur at all. In many states, lawmakers, often pressured by agribusiness, have tried to make it a serious crime to enter a factory farm’s property. The activists in Utah hoped they could win converts at trial; they gambled correctly, but, had they been wrong, they could have gone to prison. As in 1975, it remains impossible to simply petition the justice system to notice that pigs are suffering. All animals are property, and property can’t take its owner to court.

Philosophers have debated the standing of animals for centuries. Pythagoras supposedly didn’t eat them, perhaps because he believed they had souls. Their demotion to “things” owes partly to thinkers like Aristotle, who called animals “brute beasts” who exist “for the sake of man,” and to Christianity, which, like Stoicism before it, awarded unique dignity to humans. We had souls; animals did not. Since then, various secular thinkers have given this idea a new name—“inherent value,” “intrinsic dignity”—in order to explain why it is O.K. to eat a pig but not a baby. For Singer, these phrases are a “last resort,” a way to clumsily distinguish humans from nonhuman animals. Some argue that our ability to tell right from wrong, or to perceive ourselves, sets us apart—but not all humans can do these things, and some animals seem to do them better. Good law doesn’t withhold justice from humans who are elderly or infirm, or those who are cognitively disabled. As a utilitarian, Singer cites the founder of that tradition, the eighteenth-century philosopher Jeremy Bentham, who argued that justice and equality have nothing to do with a creature’s ability to reason, or with any of its abilities at all, but with the fact that it can suffer. Most animals suffer. Why, then, do we not give them moral consideration?

Singer’s answer is “speciesism,” or “bias in favor of the interests of members of one’s own species.” Like racism and sexism, speciesism denies equal consideration in order to maintain a status quo that is convenient for the oppressors. As Lawrence Wright has written in this magazine , courts, when considering the confinement of elephants and chimpanzees, have conceded that such animals evince many of the qualities that give humans legal standing, but have declined to follow through on the implications of this fact. The reason for that is obvious. If animals deserved the same consideration as humans, then we would find ourselves in a world in which billions of persons were living awful, almost unimaginably horrible lives. In which case, we might have to do something about it.

Equal consideration does not mean equal treatment. As a utilitarian, Singer’s aim is to minimize the suffering in the world and maximize the pleasure in it, a principle that invites, and often demands, choices. This is why Singer does not object to killing mosquitos (if done quickly), or to using animals for scientific research that would dramatically relieve suffering, or to eating meat if doing so would save your life. What he would not agree with, though, is making those choices on the basis of perceived intelligence or emotion. In a decision about whether to eat chicken or pork, it is not better to choose chicken simply because pigs seem smarter. The fleeting pleasure of eating any chicken is trounced by its suffering in industrial farms, where it was likely force-fed, electrocuted, and perhaps even boiled alive.

Still, Singer’s emphasis on suffering is cause for concern to Martha Nussbaum , whose new book, “ Justice for Animals ,” is an attempt to settle on the ideal philosophical template for animal rights. Whereas Singer’s argument is emphatically emotion-free—empathy, in his view, is not just immaterial but often actively misleading—Nussbaum is interested in emotions, or at least in animals’ inner lives and desires. She considers several theories of animal rights, including Singer’s, before arguing that we should adopt her “capabilities approach,” which builds on a framework developed by the Nobel Prize-winning economist Amartya Sen, and holds that all creatures should be given the “opportunity to flourish.” For decades, Nussbaum has adjusted her list of what this entails for humans, which includes “being able to live to the end of a human life of normal length,” “being able to have attachments to things and people outside ourselves,” and having “bodily integrity”—namely, freedom from violence and “choice in matters of reproduction.” In “Justice for Animals,” she outlines some conditions for nonhuman flourishing: a natural life span, social relationships, freedom of movement, bodily integrity, and play and stimulation. Eventually, she writes, we would have a refined list for each species, so that we could insure flourishing “in the form of life characteristic to the creature.”

In imagining this better world, Nussbaum is guided by three emotions: wonder, anger, and compassion. She wants us to look anew at animals such as chickens or pigs, which don’t flatter us, as gorillas might, with their resemblance to us. What pigs do, and like to do, is root around in the dirt; lacquer themselves in mud to keep cool; build comfy nests in which to shelter their babies; and communicate with one another in social groups. They also seek out belly rubs from human caregivers. In a just world, Nussbaum writes, we would wonder at a pig’s mysterious life, show compassion for her desire to exist on her own terms, and get angry when corporations get in her way.

Some of Nussbaum’s positions are more actionable, policy-wise, than others. For example, she supports legal standing for animals, which raises an obvious question: How would a pig articulate her desires to a lawyer? Nussbaum notes that a solution already exists in fiduciary law: in the event that a person, like a toddler or disabled adult, cannot communicate their decisions or make sound ones, a representative is appointed to understand that person’s interests and advocate for them. Just as organizations exist to help certain people advance their interests, organizations could represent categories of animals. In Nussbaum’s future world, such a group could take Smithfield Foods to court.

Perhaps Nussbaum’s boldest position is that wild animals should also be represented by fiduciaries, and indeed be assured, by humans, the same flourishing as any other creature. If this seems like an overreach, a quixotic attempt to control a world that is better off without our meddling, Nussbaum says, first, to be realistic: there is no such thing as a truly wild animal, given the extent of human influence on Earth. (If a whale is found dead with a brick of plastic in its stomach, how “wild” was it?) Second, in Nussbaum’s view, if nature is thoughtless—and Nussbaum thinks it is—then perhaps what happens in “the wild” is not always for the best. No injustice can be ignored. If we aspire to a world in which no sentient creature can harm another’s “bodily integrity,” or impede one from exploring and fulfilling one’s capabilities, then it is not “the destiny of antelopes to be torn apart by predators.”

Here, Nussbaum’s world is getting harder to imagine. Animal-rights writing tends to elide the issue of wild-animal suffering for obvious reasons—namely, the scarcity of solutions. Singer covers the issue only briefly, and mostly to say that it’s worth researching the merit of different interventions, such as vaccination campaigns. Nussbaum, for her part, is unclear about how we would protect wild antelopes without impeding the flourishing of their predators—or without impeding the flourishing of antelopes, by increasing their numbers and not their resources. In 2006, when she previously discussed the subject, she acknowledged that perhaps “part of what it is to flourish, for a creature, is to settle certain very important matters on its own.” In her new book, she has not entirely discarded that perspective: intervention, she writes, could result in “disaster on a large scale.” But the point is to “press this question all the time,” and to ask whether our hands-off approach is less noble than it is self-justifying—a way of protecting ourselves from following our ideals to their natural, messy, inconvenient ends.

The enduring challenge for any activist is both to dream of almost-unimaginable justice and to make the case to nonbelievers that your dreams are practical. The problem is particularly acute in animal-rights activism. Ending wild-animal suffering is laughably hard (our efforts at ending human suffering don’t exactly recommend us to the task); obviously, so is changing the landscape of factory farms, or Singer wouldn’t be reissuing his book. In 2014, the British sociologist Richard Twine suggested that the vegan isn’t unlike the feminist of yore, in that both come across as killjoys whose “resistance against routinized norms of commodification and violence” repels those who prefer the comforts of the status quo. Wayne Hsiung, the Direct Action Everywhere activist, was only recently released from jail, after being sentenced for duck and chicken rescues in California. On his blog, he wrote that one reason the prosecution succeeded was that, unlike in Utah, he and his colleagues were cast as “weird extremists.”