- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: November 16, 2023 | Original: October 6, 2017

Hinduism is the world’s oldest religion, according to many scholars, with roots and customs dating back more than 4,000 years. Today, with more than 1 billion followers , Hinduism is the third-largest religion worldwide, after Christianity and Islam . Roughly 94 percent of the world’s Hindus live in India. Because the religion has no specific founder, it’s difficult to trace its origins and history. Hinduism is unique in that it’s not a single religion but a compilation of many traditions and philosophies: Hindus worship a number of different gods and minor deities, honor a range of symbols, respect several different holy books and celebrate with a wide variety of traditions, holidays and customs. Though the development of the caste system in India was influenced by Hindu concepts , it has been shaped throughout history by political as well as religious movements, and today is much less rigidly enforced. Today there are four major sects of Hinduism: Shaivism, Vaishnava, Shaktism and Smarta, as well as a number of smaller sects with their own religious practices.

Hinduism Beliefs, Symbols

Some basic Hindu concepts include:

- Hinduism embraces many religious ideas. For this reason, it’s sometimes referred to as a “way of life” or a “family of religions,” as opposed to a single, organized religion.

- Most forms of Hinduism are henotheistic, which means they worship a single deity, known as “Brahman,” but still recognize other gods and goddesses. Followers believe there are multiple paths to reaching their god.

- Hindus believe in the doctrines of samsara (the continuous cycle of life, death, and reincarnation) and karma (the universal law of cause and effect).

- One of the key thoughts of Hinduism is “atman,” or the belief in soul. This philosophy holds that living creatures have a soul, and they’re all part of the supreme soul. The goal is to achieve “moksha,” or salvation, which ends the cycle of rebirths to become part of the absolute soul.

- One fundamental principle of the religion is the idea that people’s actions and thoughts directly determine their current life and future lives.

- Hindus strive to achieve dharma, which is a code of living that emphasizes good conduct and morality.

- Hindus revere all living creatures and consider the cow a sacred animal.

- Food is an important part of life for Hindus. Most don’t eat beef or pork, and many are vegetarians.

- Hinduism is closely related to other Indian religions, including Buddhism , Sikhism and Jainism.

There are two primary symbols associated with Hinduism, the om and the swastika. The word swastika means "good fortune" or "being happy" in Sanskrit, and the symbol represents good luck . (A hooked, diagonal variation of the swastika later became associated with Germany’s Nazi Party when they made it their symbol in 1920.)

The om symbol is composed of three Sanskrit letters and represents three sounds (a, u and m), which when combined are considered a sacred sound. The om symbol is often found at family shrines and in Hindu temples.

Hinduism Holy Books

Hindus value many sacred writings as opposed to one holy book.

The primary sacred texts, known as the Vedas, were composed around 1500 B.C. This collection of verses and hymns was written in Sanskrit and contains revelations received by ancient saints and sages.

The Vedas are made up of:

- The Rig Veda

- The Samaveda

- Atharvaveda

Hindus believe that the Vedas transcend all time and don’t have a beginning or an end.

The Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita, 18 Puranas, Ramayana and Mahabharata are also considered important texts in Hinduism.

Origins of Hinduism

Most scholars believe Hinduism started somewhere between 2300 B.C. and 1500 B.C. in the Indus Valley, near modern-day Pakistan. But many Hindus argue that their faith is timeless and has always existed.

Unlike other religions, Hinduism has no one founder but is instead a fusion of various beliefs.

Around 1500 B.C., the Indo-Aryan people migrated to the Indus Valley, and their language and culture blended with that of the indigenous people living in the region. There’s some debate over who influenced whom more during this time.

The period when the Vedas were composed became known as the “Vedic Period” and lasted from about 1500 B.C. to 500 B.C. Rituals, such as sacrifices and chanting, were common in the Vedic Period.

The Epic, Puranic and Classic Periods took place between 500 B.C. and A.D. 500. Hindus began to emphasize the worship of deities, especially Vishnu, Shiva and Devi.

The concept of dharma was introduced in new texts, and other faiths, such as Buddhism and Jainism, spread rapidly.

Hinduism vs. Buddhism

Hinduism and Buddhism have many similarities. Buddhism, in fact, arose out of Hinduism, and both believe in reincarnation, karma and that a life of devotion and honor is a path to salvation and enlightenment.

But some key differences exist between the two religions: Many strains of Buddhism reject the caste system, and do away with many of the rituals, the priesthood, and the gods that are integral to Hindu faith.

Medieval and Modern Hindu History

The Medieval Period of Hinduism lasted from about A.D. 500 to 1500. New texts emerged, and poet-saints recorded their spiritual sentiments during this time.

In the 7th century, Muslim Arabs began invading areas in India. During parts of the Muslim Period, which lasted from about 1200 to 1757, Islamic rulers prevented Hindus from worshipping their deities, and some temples were destroyed.

Mahatma Gandhi

Between 1757 and 1947, the British controlled India. At first, the new rulers allowed Hindus to practice their religion without interference, but the British soon attempted to exploit aspects of Indian culture as leverage points for political control, in some cases exacerbating Hindu caste divisions even as they promoted westernized, Christian approaches.

Many reformers emerged during the British Period. The well-known politician and peace activist, Mahatma Gandhi , led a movement that pushed for India’s independence.

The partition of India occurred in 1947, and Gandhi was assassinated in 1948. British India was split into what are now the independent nations of India and Pakistan , and Hinduism became the major religion of India.

Starting in the 1960s, many Hindus migrated to North America and Britain, spreading their faith and philosophies to the western world.

Hindus worship many gods and goddesses in addition to Brahman, who is believed to be the supreme God force present in all things.

Some of the most prominent deities include:

- Brahma: the god responsible for the creation of the world and all living things

- Vishnu: the god that preserves and protects the universe

- Shiva: the god that destroys the universe in order to recreate it

- Devi: the goddess that fights to restore dharma

- Krishna: the god of compassion, tenderness and love

- Lakshmi: the goddess of wealth and purity

- Saraswati: the goddess of learning

Places of Worship

Hindu worship, which is known as “puja,” typically takes place in the Mandir (temple). Followers of Hinduism can visit the Mandir any time they please.

Hindus can also worship at home, and many have a special shrine dedicated to certain gods and goddesses.

The giving of offerings is an important part of Hindu worship. It’s a common practice to present gifts, such as flowers or oils, to a god or goddess.

Additionally, many Hindus take pilgrimages to temples and other sacred sites in India.

Hinduism Sects

Hinduism has many sects, and the following are often considered the four major denominations.

Shaivism is one of the largest denominations of Hinduism, and its followers worship Shiva, sometimes known as “The Destroyer,” as their supreme deity.

Shaivism spread from southern India into Southeast Asia and is practiced in Vietnam, Cambodia and Indonesia as well as India. Like the other major sects of Hinduism, Shaivism considers the Vedas and the Upanishads to be sacred texts.

Vaishnavism is considered the largest Hindu sect, with an estimated 640 million followers, and is practiced worldwide. It includes sub-sects that are familiar to many non-Hindus, including Ramaism and Krishnaism.

Vaishnavism recognizes many deities, including Vishnu, Lakshmi, Krishna and Rama, and the religious practices of Vaishnavism vary from region to region across the Indian subcontinent.

Shaktism is somewhat unique among the four major traditions of Hinduism in that its followers worship a female deity, the goddess Shakti (also known as Devi).

Shaktism is sometimes practiced as a monotheistic religion, while other followers of this tradition worship a number of goddesses. This female-centered denomination is sometimes considered complementary to Shaivism, which recognizes a male deity as supreme.

The Smarta or Smartism tradition of Hinduism is somewhat more orthodox and restrictive than the other four mainstream denominations. It tends to draw its followers from the Brahman upper caste of Indian society.

Smartism followers worship five deities: Vishnu, Shiva, Devi, Ganesh and Surya. Their temple at Sringeri is generally recognized as the center of worship for the denomination.

Some Hindus elevate the Hindu trinity, which consists of Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva. Others believe that all the deities are a manifestation of one.

Hindu Caste System

The caste system is a social hierarchy in India that divides Hindus based on their karma and dharma. Although the word “caste” is of Portuguese origin, it is used to describe aspects of the related Hindu concepts of varna (color or race) and jati (birth). Many scholars believe the system dates back more than 3,000 years.

The four main castes (in order of prominence) include:

- Brahmin: the intellectual and spiritual leaders

- Kshatriyas: the protectors and public servants of society

- Vaisyas: the skillful producers

- Shudras: the unskilled laborers

Many subcategories also exist within each caste. The “Untouchables” are a class of citizens that are outside the caste system and considered to be in the lowest level of the social hierarchy.

For centuries, the caste system determined most aspect of a person’s social, professional and religious status in India.

HISTORY Vault: Ancient History

From the Sphinx of Egypt to the Kama Sutra, explore ancient history videos.

When India became an independent nation, its constitution banned discrimination based on caste.

Today, the caste system still exists in India but is loosely followed. Many of the old customs are overlooked, but some traditions, such as only marrying within a specific caste, are still embraced.

Hindus observe numerous sacred days, holidays and festivals.

Some of the most well-known include:

- Diwali : the festival of lights

- Navaratri: a celebration of fertility and harvest

- Holi: a spring festival

- Krishna Janmashtami: a tribute to Krishna’s birthday

- Raksha Bandhan: a celebration of the bond between brother and sister

- Maha Shivaratri: the great festival of Shiva

Hinduism Facts. Sects of Hinduism . Hindu American Foundation. Hinduism Basics . History of Hinduism, BBC . Hinduism Fast Facts, CNN .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Religion in India: Tolerance and Segregation

- 1. Religious freedom, discrimination and communal relations

Table of Contents

- The dimensions of Hindu nationalism in India

- India’s Muslims express pride in being Indian while identifying communal tensions, desiring segregation

- Muslims, Hindus diverge over legacy of Partition

- Religious conversion in India

- Religion very important across India’s religious groups

- Near-universal belief in God, but wide variation in how God is perceived

- Across India’s religious groups, widespread sharing of beliefs, practices, values

- Religious identity in India: Hindus divided on whether belief in God is required to be a Hindu, but most say eating beef is disqualifying

- Sikhs are proud to be Punjabi and Indian

- 2. Diversity and pluralism

- 3. Religious segregation

- 4. Attitudes about caste

- 5. Religious identity

- 6. Nationalism and politics

- 7. Religious practices

- 8. Religion, family and children

- 9. Religious clothing and personal appearance

- 10. Religion and food

- 11. Religious beliefs

- 12. Beliefs about God

- Acknowledgments

- Appendix A: Methodology

- Appendix B: Index of religious segregation

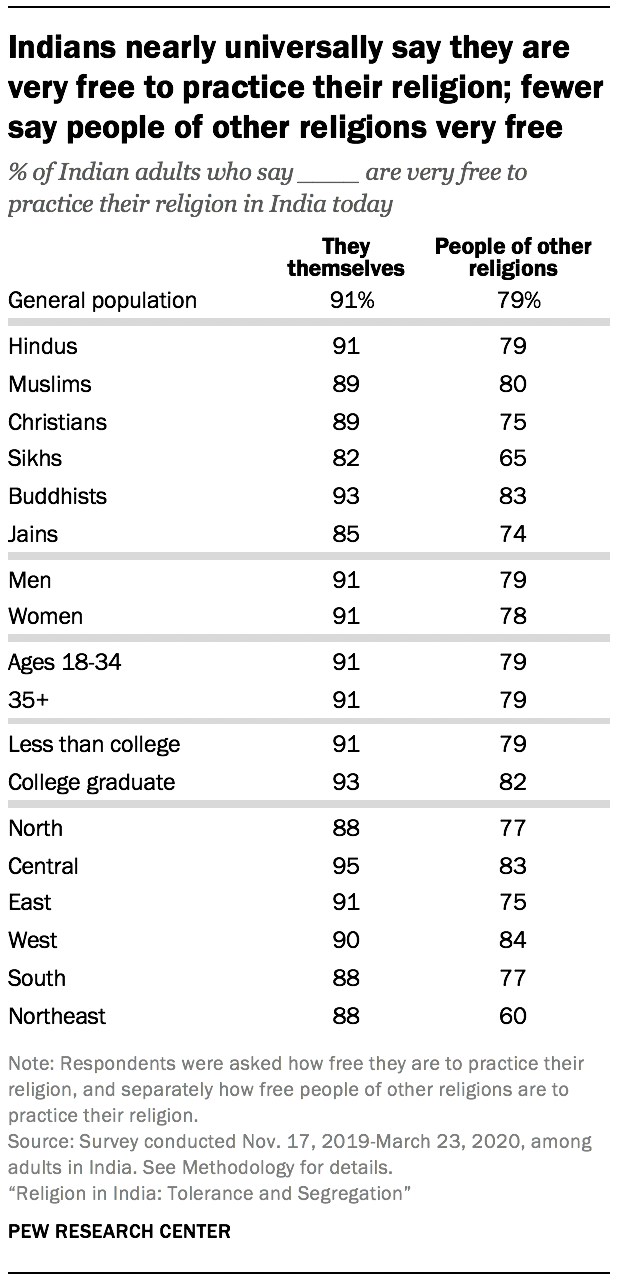

Indians generally see high levels of religious freedom in their country. Overwhelming majorities of people in each major religious group, as well as in the overall public, say they are “very free” to practice their religion. Smaller shares, though still majorities within each religious community, say people of other religions also are very free to practice their religion. Relatively few Indians – including members of religious minority communities – perceive religious discrimination as widespread.

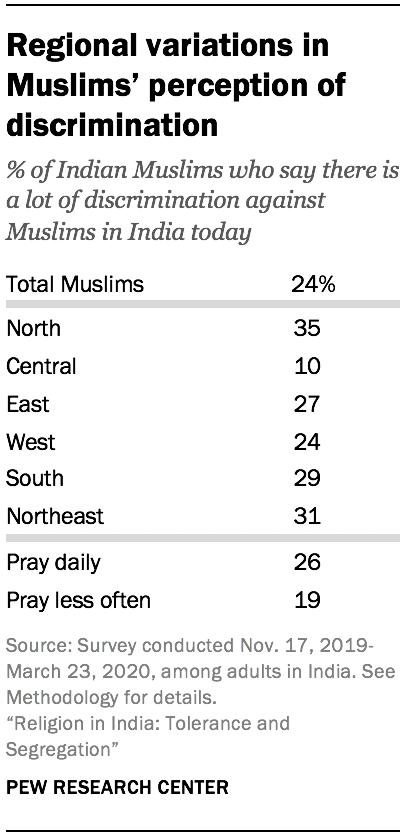

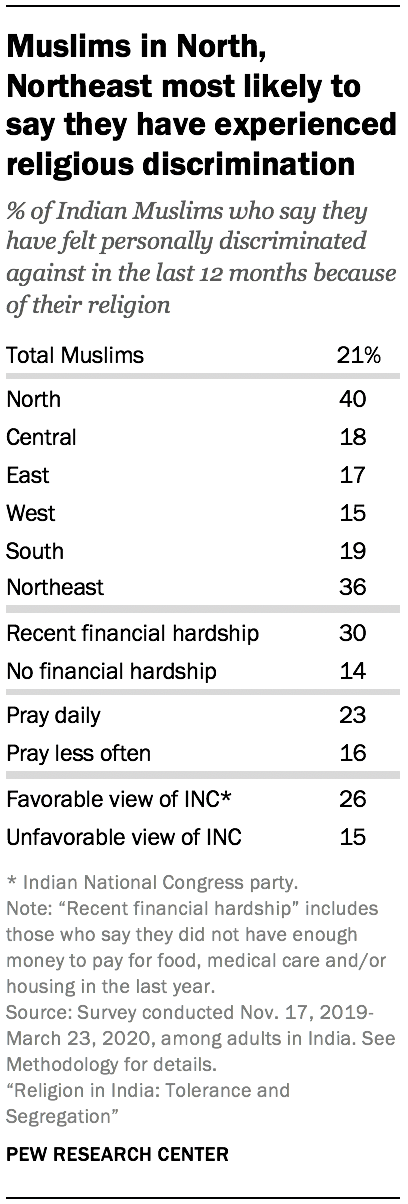

At the same time, perceptions of discrimination vary a great deal by region. For example, Muslims in the Central region of the country are generally less likely than Muslims elsewhere to say there is a lot of religious discrimination in India. And Muslims in the North and Northeast are much more likely than Muslims in other regions to report that they, personally, have experienced recent discrimination.

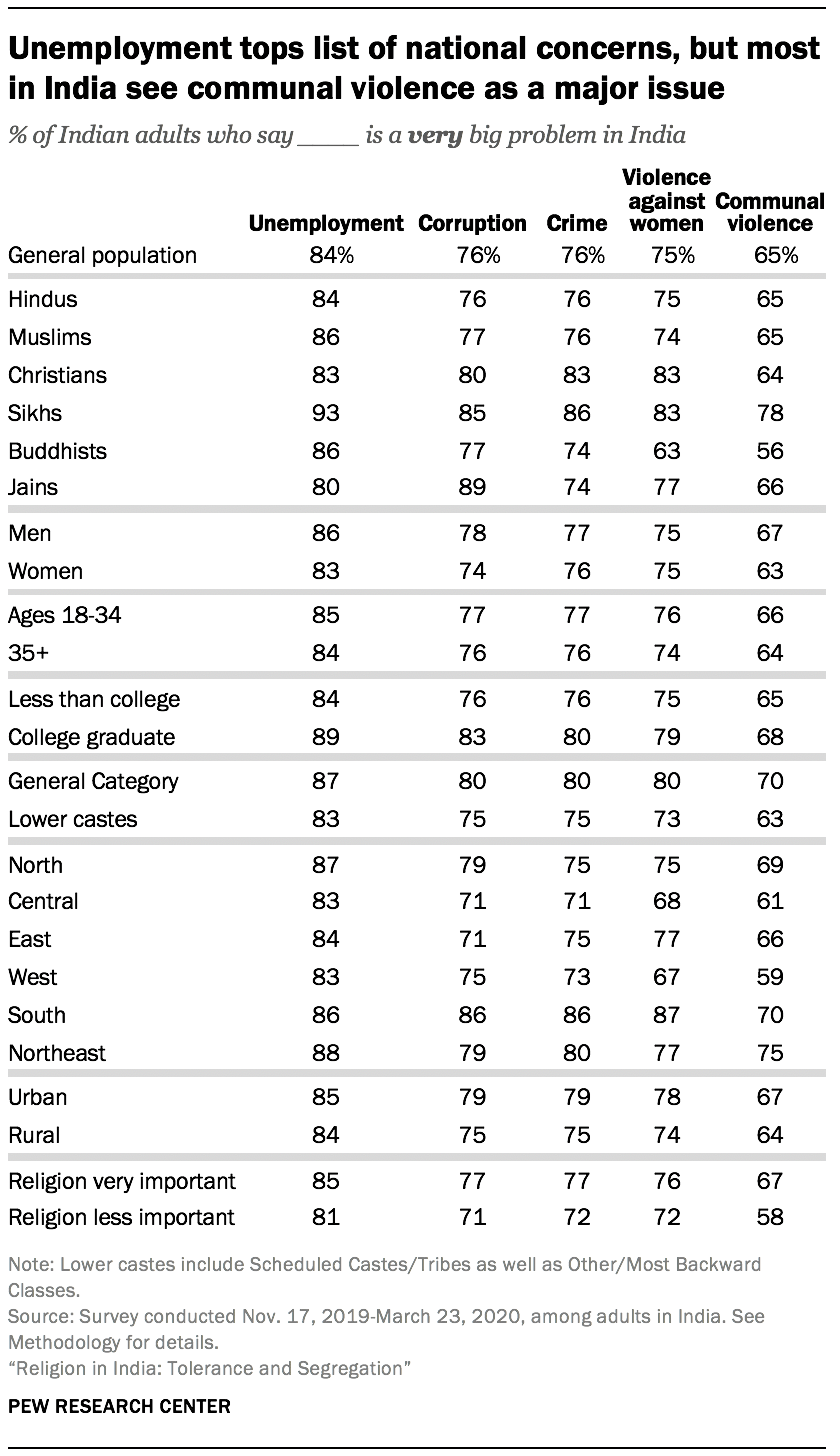

Indians also widely consider communal violence to be an issue of national concern (along with other problems, such as unemployment and corruption). Most people across different religious backgrounds, education levels and age groups say communal violence is a very big problem in India.

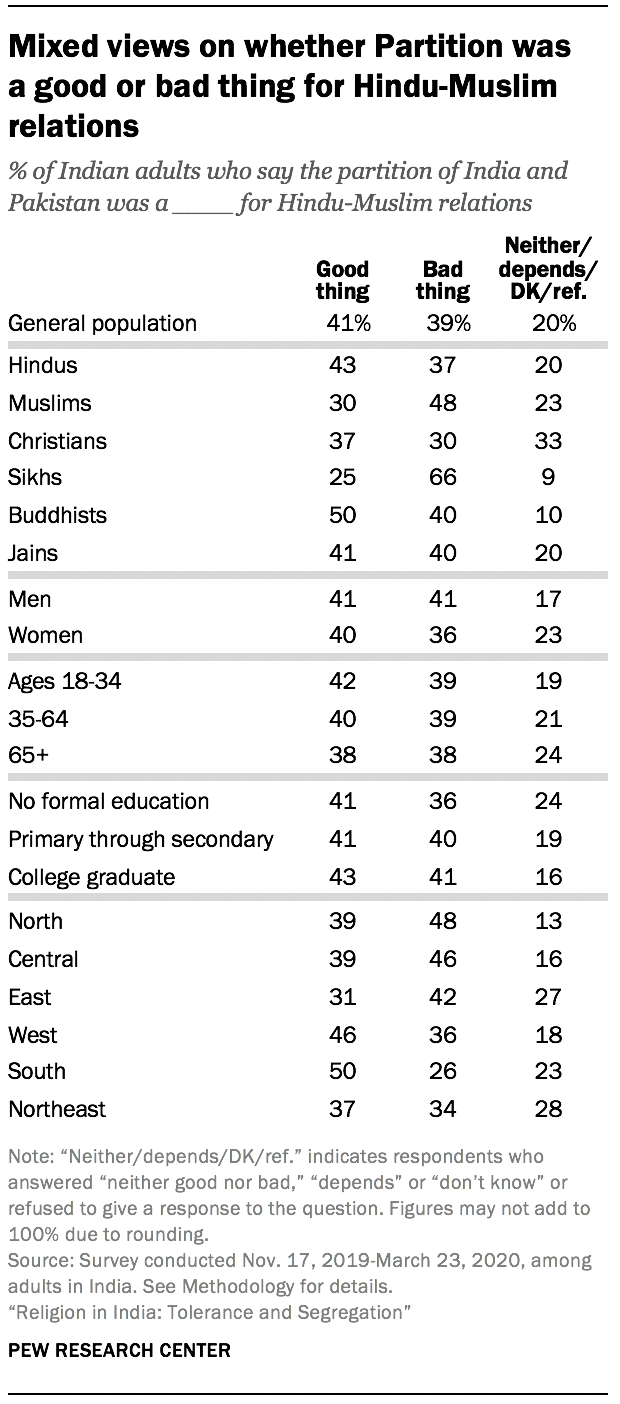

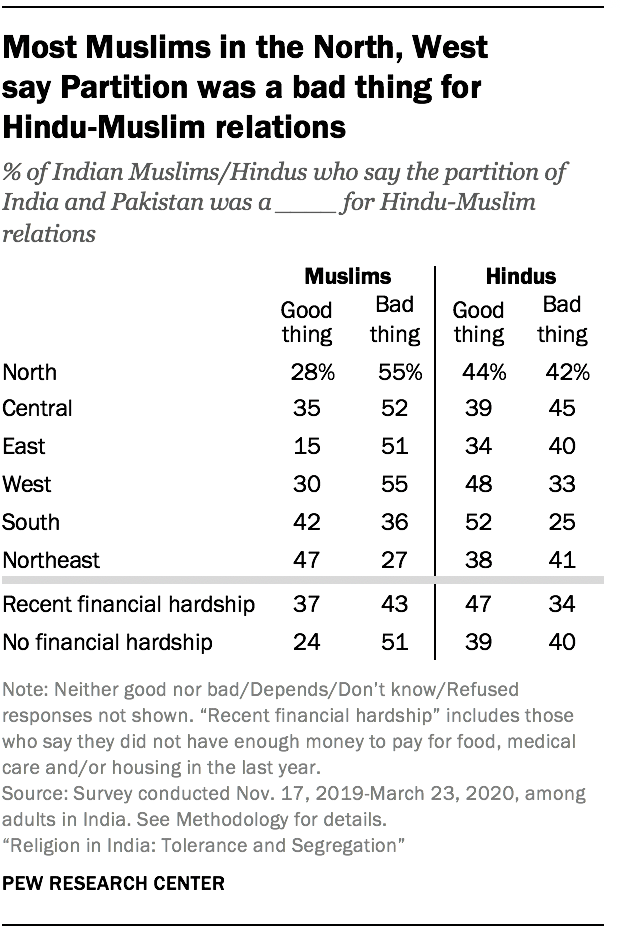

The partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947 remains a subject of disagreement. Overall, the survey finds mixed views on whether the establishment of Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan alleviated communal tensions or stoked them. On balance, Muslims tend to see Partition as a “bad thing” for Hindu-Muslim relations, while Hindus lean slightly toward viewing it as a “good thing.”

Most Indians say they and others are very free to practice their religion

The vast majority of Indians say they are very free today to practice their religion (91%), and all of India’s major religious groups share this sentiment: Roughly nine-in-ten Buddhists (93%), Hindus (91%), Muslims (89%) and Christians (89%) say they are very free to practice their religion, as do 85% of Jains and 82% of Sikhs.

Broadly speaking, Indians are more likely to view themselves as having a high degree of religious freedom than to say that people of other religions are very free to practice their faiths. Still, 79% of the overall public – and about two-thirds or more of the members of each of the country’s major religious communities – say that people belonging to other religions are very free to practice their faiths in India today.

Generally, these attitudes do not vary substantially among Indians of different ages, educational backgrounds or geographic regions. Indians in the Northeast are somewhat less likely than those elsewhere to see widespread religious freedom for people of other faiths – yet even in the Northeast, a solid majority (60%) say there is a high level of religious freedom for other religious communities in India.

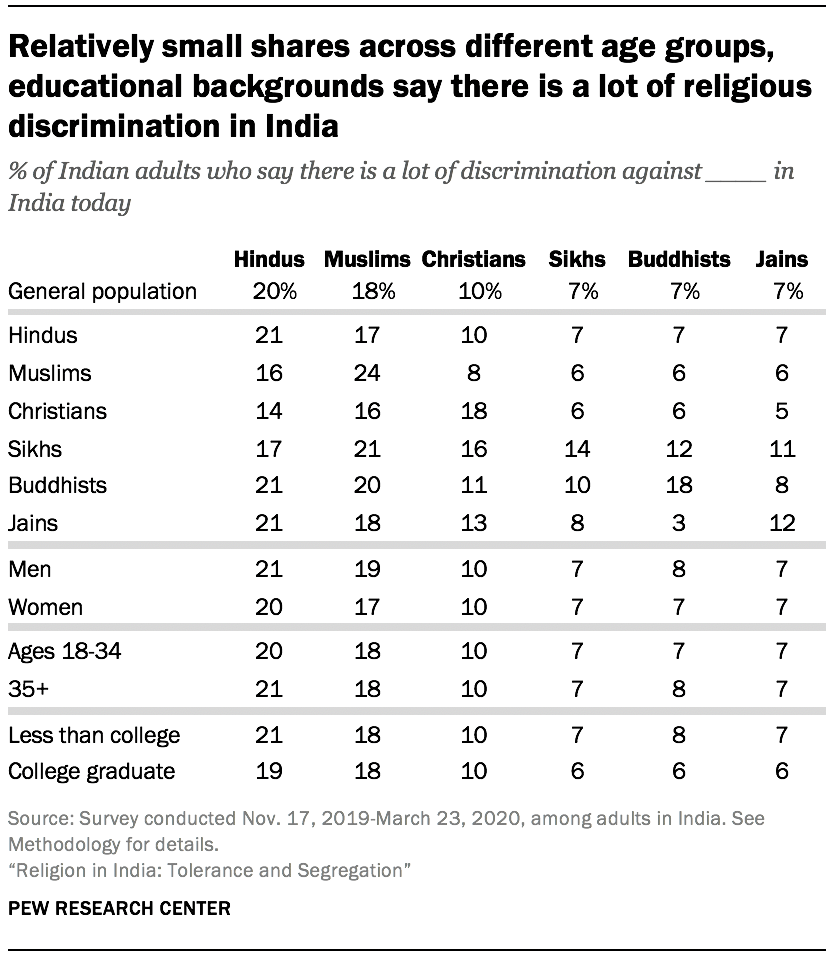

Most people do not see evidence of widespread religious discrimination in India

Most people in India do not see a lot of religious discrimination against any of the country’s six major religious groups. In general, Hindus, Muslims and Christians are slightly more likely to say there is a lot of discrimination against their own religious community than to say there is a lot of discrimination against people of other faiths. Still, no more than about one-quarter of the followers of any of the country’s major faiths say they face widespread discrimination.

Generally, Indians’ opinions about religious discrimination do not vary substantially by gender, age or educational background. For example, among college graduates, 19% say there is a lot of discrimination against Hindus, compared with 21% among adults with less education.

Within religious groups as well, people of different ages, as well as both men and women, tend to have similar opinions on religious discrimination.

However, there are large regional variations in perceptions of religious discrimination. For example, among Muslims who live in the Central part of the country, just one-in-ten say there is widespread discrimination against Muslims in India, compared with about one-third of those who live in the North (35%) and Northeast (31%). (For more information on measures of religious discrimination in the Northeast, see “ In Northeast India, people perceive more religious discrimination ” below.)

Among Muslims, perceptions of discrimination against their community can vary somewhat based on their level of religious observance. For instance, about a quarter of Muslims across the country who pray daily say there is a lot of discrimination against Muslims (26%), compared with 19% of Muslims nationwide who pray less often. This difference by observance is pronounced in the North, where 39% of Muslims who pray every day say there is a lot of discrimination against Muslims in India, roughly twice the share among those in the same region who pray less often (20%).

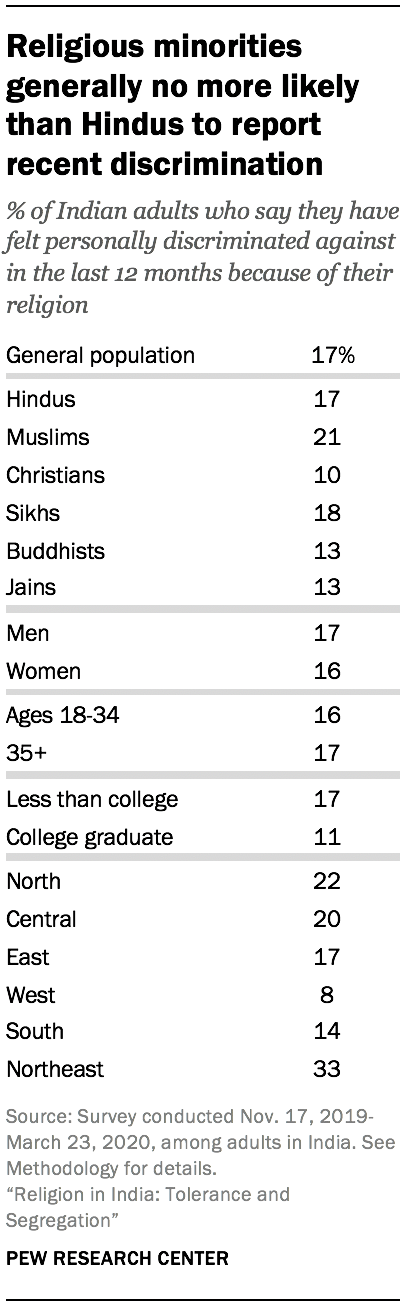

Most Indians report no recent discrimination based on their religion

The survey also asked respondents about their personal experiences with discrimination. In all, 17% of Indians report facing recent discrimination based on their religion. Roughly one-in-five Muslims (21%) and 17% of Hindus say that in the last 12 months they themselves have faced discrimination because of their religion, as do 18% of Sikhs. By contrast, Christians are less likely to say they have felt discriminated against because of their religion (10%), and similar shares of Buddhists and Jains (13% each) fall into this category.

Nationally, men and women and people belonging to different age groups do not differ significantly from each other in their experiences with religious discrimination. People who have a college degree, however, are somewhat less likely than those with less formal schooling to say they have experienced religious discrimination in the past year.

Within religious groups, experiences with discrimination vary based on region of residence and other factors. Among Muslims, for instance, 40% of those living in Northern India and 36% in the Northeast say they have faced recent religious discrimination, compared with no more than one-in-five in the Southern, Central, Eastern and Western regions.

Experiences with religious discrimination also are more common among Muslims who are more religious and those who report recent financial hardship (that is, they have not been able to afford food, housing or medical care for themselves or their families in the last year).

Muslims who have a favorable view of the Indian National Congress party (INC) are more likely than Muslims with an unfavorable view of the party to say they have experienced religious discrimination (26% vs. 15%). Among Northern Muslims, those who have a favorable view of the INC are much more likely than those who don’t approve of the INC to say they have experienced discrimination (45% vs. 23%). (Muslims in the country, and especially Muslims in the North, tend to say they voted for the Congress party in the 2019 election. See Chapter 6 .)

Hindus with less education and those who have recently experienced poverty also are more likely to say they have experienced religious discrimination.

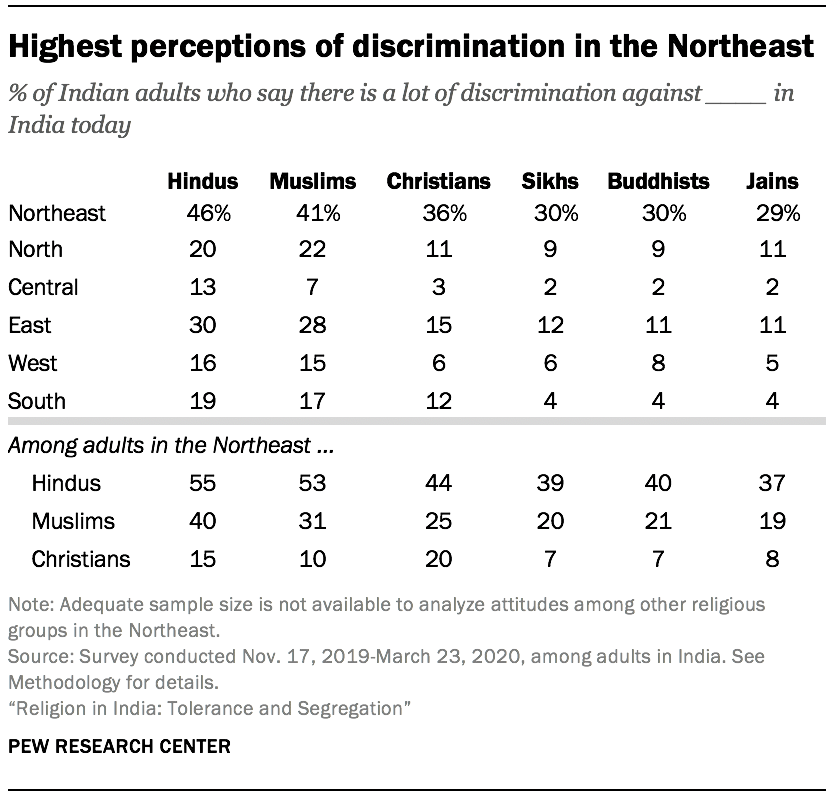

In Northeast India, people perceive more religious discrimination

Less than 5% of India’s population lives in the eight isolated states of the country’s Northeastern region. This region broadly lags behind the country in economic development indicators. And this small segment of the population has a linguistic and religious makeup that differs drastically from the rest of the country.

According to the 2011 census of India, Hindus are still the majority religious group (58%), but they are less prevalent in the Northeast than elsewhere (81% nationally). The smaller proportion of Hindus there is offset by the highest shares of Christians (16% vs. 2% nationally) and Muslims (22% vs. 13% nationally) in any region. And based on the survey, the region also has a higher share of Scheduled Tribes than any other region in the country (25% vs. 9% nationally), and half of Scheduled Tribe members in the Northeast are Christians.

Indians in the Northeast are more likely than those elsewhere to perceive high levels of religious discrimination. For example, roughly four-in-ten in the region say there is a lot of discrimination against Muslims in India, about twice the share of North Indians who say the same thing (41% vs. 22%).

Much of the Northeast’s perception of high religious discrimination is driven by Hindus in the region. A slim majority of Northeastern Hindus (55%) say there is widespread discrimination against Hindus in India, while almost as many (53%) say Muslims face a lot of discrimination. Substantial shares of Hindus in the Northeast say other religious communities also face such mistreatment.

The region’s other religious communities are less likely to say there is religious discrimination in India. For example, while 44% of Northeastern Hindus say Christians face a lot of discrimination, only one-in-five Christians in the Northeast perceive this level of discrimination against their own group. By contrast, at the national level, Christians are more likely than Hindus to see a lot of discrimination against Christians (18% vs. 10%).

People in the Northeast also are more likely to report experiencing religious discrimination. While 17% of individuals nationally say they personally have felt religious discrimination in the last 12 months, one-third of those surveyed in the Northeast say they have had such an experience. Northeastern Hindus, in particular, are much more likely than Hindus elsewhere to report recent religious discrimination (37% vs. 17% nationally).

Most Indians see communal violence as a very big problem in the country

Most Indians (65%) say communal violence – a term broadly used to describe violence between religious groups – is a “very big problem” in their country (the term was not defined for respondents). This includes identical shares of Hindus and Muslims (65% each) who say this.

But even larger majorities identify several other national problems. Unemployment tops the list of national concerns, with 84% of Indians saying this is a very big problem. And roughly three-quarters of Indian adults see corruption (76%), crime (76%) and violence against women (75%) as very big national issues. (The survey was designed and mostly conducted before the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic.)

Indians across nearly every religious group, caste category and region consistently rank unemployment as the top national concern. Buddhists, who overwhelmingly belong to disadvantaged castes, widely rank unemployment as a major concern (86%), while just a slim majority see communal violence as a very big problem (56%).

Sikhs are more likely than other major religious groups in India to say communal violence is a major issue (78%). This concern is especially pronounced among college-educated Sikhs (87%).

Among Hindus, those who are more religious are more likely to see communal violence as a major issue: Fully 67% of Hindus who say religion is very important in their lives consider communal violence a major issue, compared with 58% among those who say religion is less important to them.

Indians in different regions of the country also differ in their concern about communal violence: Three-quarters of Indians in the Northeast say communal violence is a very big problem, compared with 59% in the West. Concerns about communal violence are widespread in the national capital of Delhi, where 78% of people say this is a major issue. During fieldwork for this study, major protests broke out in New Delhi (and elsewhere) following the BJP-led government’s passing of a new bill, which creates an expedited path to citizenship for immigrants from some neighboring countries – but not Muslims.

Indians divided on the legacy of Partition for Hindu-Muslim relations

The end of Britain’s colonial rule in India, in 1947, was accompanied by the separation of Hindu-majority India from Muslim-majority Pakistan and massive migration in both directions. Nearly three-quarters of a century later, Indians are divided over the legacy of Partition.

About four-in-ten (41%) say the partition of India and Pakistan was a good thing for Hindu-Muslim relations, while a similar share (39%) say it was a bad thing. The rest of the population (20%) does not provide a clear answer, saying Partition was neither a good thing nor a bad thing, that it depends, or that they don’t know or cannot answer the question. There are no clear patterns by age, gender, education or party preference on opinions on this question.

Among Muslims, the predominant view is that Partition was a bad thing (48%) for Hindu-Muslim relations. Fewer see it as a good thing (30%). Hindus are more likely than Muslims to say Partition was a good thing for Hindu-Muslim relations (43%) and less likely to say it was a bad thing (37%).

Of the country’s six major religious groups, Sikhs have the most negative view of the role Partition played in Hindu-Muslim relations: Nearly two-thirds (66%) say it was a bad thing.

Most Indian Sikhs live in Punjab, along the border with Pakistan. The broader Northern region (especially Punjab) was strongly impacted by the partition of the subcontinent, and Northern Indians as a whole lean toward the position that Partition was a bad thing for Hindu-Muslim relations (48%) rather than a good thing (39%).

The South is the furthest region from the borders affected by Partition, and Southern Indians are about twice as likely to say that Partition was good as to say that it was bad for Hindu-Muslim relations (50% vs. 26%).

Attitudes toward Partition also vary considerably by region within specific religious groups. Among Muslims in the North and West, most say Partition was a bad thing for Hindu-Muslim relations (55% of Muslims in both regions). In the Eastern and Central parts of the country as well, Muslim public opinion leans toward the view that Partition was a bad thing for communal relations. By contrast, Muslims in the South and Northeast tend to see Partition as good for Hindu-Muslim relations.

Among Hindus, meanwhile, those in the North are closely divided on the issue, with 44% saying Partition was a good thing and 42% saying it was a bad thing. But in the West and South, Hindus tend to see Partition as a good thing for communal relations.

Poorer Hindus – that is, those who say they have been unable to afford basic necessities like food, housing and medical care in the last year – tend to say Partition was a good thing. But opinions are more divided among Hindus who have not recently experienced poverty (39% say it was a good thing, while 40% say it was a bad thing). Muslims who have not experienced recent financial hardship, however, are especially likely to see Partition as a bad thing: Roughly half (51%) say Partition was a bad thing for Hindu-Muslim relations, while only about a quarter (24%) see it as a good thing.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Beliefs & Practices

- Christianity

- International Political Values

- International Religious Freedom & Restrictions

- Interreligious Relations

- Other Religions

- Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures Project

- Religious Characteristics of Demographic Groups

- Religious Identity & Affiliation

- Religiously Unaffiliated

- Size & Demographic Characteristics of Religious Groups

How common is religious fasting in the United States?

8 facts about atheists, spirituality among americans, how people in south and southeast asia view religious diversity and pluralism, religion among asian americans, most popular, report materials.

- Questionnaire

- Overview (Hindi)

- இந்தியாவில் மதம்: சகிப்புத்தன்மையும் தனிப்படுத்துதலும்

- भारत में धर्म: सहिष्णुता और अलगाव

- ভারতে ধর্ম: সহনশীলতা এবং পৃথকীকরণ

- भारतातील धर्म : सहिष्णुता आणि विलग्नता

- Related: Religious Composition of India

- How Pew Research Center Conducted Its India Survey

- Questionnaire: Show Cards

- India Survey Dataset

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

Indian Culture

Religion has historically influenced Indian society on a political, cultural and economic level. There is a sense of pride associated with the country’s rich religious history as the traditions of Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism and Jainism all emerged out of India. Moreover, while a majority of people in India identify as Hindu (79.8%), the medley of religions that exist within the country continually impact contemporary society.

In India, religion is more publicly visible than it is in most English-speaking Western countries. This becomes evident when considering the numerous spaces that are thought to be sacred and holy. Examples include ‘ ashrams ’ (monasteries or congregation sites) consisting of large communities of scholars or monastics, temples ( mandir ), shrines and specific landscapes such as the Ganges river. There is a rich religious history visible in architecture, and it is not uncommon to find various places of worship, such as a Hindu temple, Muslim mosque and Christian church, all next to each other.

The 2011 Indian census indicated that 79.8% of Indians identified as Hindu, 14.2% identified as Muslim and 2.3% identified as Christian. A further 1.7% of the population identified as Sikh, 0.7% identified as Buddhist and 0.37% identified as Jain. Due to the massive population size of India, religious minorities still represent a significant number of people. For example, although only 0.37% of India may identify with Jainism, that still equates to over 4 million people. While not all religions in India can be discussed in detail, the following provides an overview of the major religions in the country as well as sizable religions that originated in India.

Hinduism in India

Hinduism – the most widely followed religion in India – can be interpreted diversely. Pinpointing what constitutes Hinduism is difficult, with some suggesting that it is an umbrella term that encompasses various religions and traditions within it. Nonetheless, Hinduism in all its forms has been particularly influential in Indian society.

Hinduism continues to thrive in modern-day India. The religion affects everyday life and social interactions among people through the many Hindu-inspired festivities, artistic works and temples. There is also a continuing revival of the classical ‘epic' narratives of the Ramayana (Rama’s Journey) and the Mahabharata (The Great Epic of the Bharata Dynasty) through the medium of film and television. The Krishna Lila (The Playful Activities of Krishna) is another popular tale among many villages.

It is common to find images of gods and goddesses in public and private spaces at all times of the year. The elephant-headed god, known as Ganesh , is particularly popular due to his believed ability to remove obstacles. Natural landscapes are also venerated, such as particular trees or rivers. The Hindu pantheon of deities extends into the hundreds of thousands due to the localised and regional incarnations of gods and goddesses. There are also many festivals celebrated throughout the country dedicated to the many Hindu narratives and deities.

Social Structure

One influential component of Hinduism impacting India is the large-scale caste system , known as the ‘ varna ’ system. The varna caste system represented the Hindu ideal of how society ought to be structured. This form of organisation classified society into four ideal categories: brahmin (priestly caste), kshatriya (warrior, royalty or nobility caste), vaishya (commoner or merchant caste) and shudra (artisan or labourer caste).

It is a hereditary system in that people are believed to be born into a family of a specific caste. Each caste has specific duties (sometimes known as ‘ dharma ’) they are expected to uphold as part of their social standing. For instance, a member of the Brahmin caste may be expected to attend to religious affairs (such as learning religious texts and performing rituals) while avoiding duties outside of their caste, such as cleaning. In contemporary times, Brahmin men who have been trained as priests often tend to temples and perform ritual activities on behalf of other members of Hindu society.

Islam in India

Islam is the second most followed religion in India, influencing the country's society, culture, architecture and artistry. The partition of the subcontinent in 1947 led to mass emigration of roughly 10 million Muslims to Pakistan and nearly as many Hindus and Sikhs from Pakistan into India. This event changed the demographics of both countries significantly and is continually felt throughout India.

Nonetheless, the Islamic community in India continues to play a considerable role in the development of the country. For example, the Muslim community in India has contributed to theological research and the establishment of religious facilities, institutes and universities. The mystical strain of Islam (Sufism) is also popular, with people gathering to watch Sufi dance performances. The majority of Muslims are Sunni, but there are also influential Shi'ite minorities in Gujarat. Most Sunnis reside in Jammu and Kashmir, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal and Kerala as well as major cities.

Sikhism in India

Originating in India, Sikhism is a monotheistic religion that promotes devotion to a formless God. The religion is centred on a tenet of service, humility and equality, encouraging its followers to seek to help those less fortunate or in need. For example, it is common for Sikhs to offer food to those visiting a gurdwara (the primary place of worship for Sikhs). One of the most recognised symbols of the Sikh community is a Sikh turban (known as a ‘ dastar ’ or a ‘ dumalla ’) worn by many men and some women. Since the partition of India and Pakistan, most Sikhs in India have resided in the Punjab region.

Buddhism in India

Buddhism originated as a countermovement to early Hinduism by presenting a universal ethic rather than basing ethical codes on an individual’s caste. The core doctrine of Buddhism, known as the ‘Four Noble Truths’, teaches that one can be liberated from the suffering that underpins the cycle of death and rebirth by practising the ‘Noble Eightfold Path’. Buddhism has become more widely practised in India over the last 30 years. This is partially due to the increased migration of exiled Buddhist monks from Tibet. However, its popularity has also increased as many from the 'untouchables' caste view it as a viable alternative to Hinduism in contemporary Indian society. Many Buddhists reside in the states of Maharashtra, Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir.

Jainism in India

Jainism also originated as a countermovement that opposed some of the teachings and doctrines of early Hinduism. In modern-day India, layperson Jains usually uphold the ethical principle of ‘ ahimsa ’ (‘non-harm’ or ‘non-violence’). As such, Jains tend to promote vegetarianism and animal welfare. Another common practice in the Jain lay community is samayika , a meditative ritual intended to strengthen one's spiritual discipline. Samayika is often practised in a religious setting, such as a temple, before a monk, or in one's home. Most Jains reside in Maharashtra, Gujarat and Rajasthan.

Christianity in India

Christianity is the third most followed religion in India, mostly concentrated in the far south and Mumbai. The most prominent denomination of Christianity in India is Roman Catholicism, but there are also localised Christian churches (such as the Church of North India and the Church of South India). Converts to Christianity have come mainly from traditionally disadvantaged minorities such as lower castes and tribal groups.

Get a downloadable PDF that you can share, print and read.

Grow and manage diverse workforces, markets and communities with our new platform

Essay on Religion and Politics in India

Students are often asked to write an essay on Religion and Politics in India in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Religion and Politics in India

Introduction.

Religion and politics in India are deeply intertwined. India is a land of diverse religions, and this diversity influences its political landscape.

Religious Influence

Religion plays a significant role in Indian politics. Many political parties are based on religious identities, leading to a blend of religion and politics.

Secularism in Politics

Despite the religious influence, India is a secular country. The government is committed to treating all religions equally, ensuring no discrimination.

Challenges and Conclusion

While the blend of religion and politics can create unity, it can also lead to conflicts. It’s crucial for India to maintain its secular nature while respecting religious diversity.

250 Words Essay on Religion and Politics in India

India, a country of diverse cultures and religions, has always found its politics deeply intertwined with religion. This amalgamation has significantly influenced the socio-political landscape of the nation, shaping its democratic ethos and electoral politics.

Historical Perspective

The birth of India as an independent nation was marked by a partition along religious lines, setting a precedent for the interplay between religion and politics. The political discourse in India has been marked by religious identity, with parties often using religion as a tool to mobilize voters.

Religion as a Political Tool

Religion in India is not just a spiritual matter; it’s a socio-political entity. Political parties capitalize on religious sentiments to foster a sense of identity and unity among their supporters. This strategy often leads to the polarization of society along religious lines, creating a breeding ground for communal tensions.

Secularism and Politics

The Indian constitution advocates for secularism, ensuring equal rights and freedom for all religions. However, the practical implementation often gets blurred with political interests. The selective use of secularism by political parties to appease certain religious groups has raised questions about the true essence of Indian secularism.

The intersection of religion and politics in India is a complex phenomenon. While religion plays a significant role in shaping political ideology and voter behavior, it also poses challenges to India’s secular fabric. Striking a balance between religious freedom and political integrity is crucial for the sustenance of India’s pluralistic democracy.

500 Words Essay on Religion and Politics in India

The interplay of religion and politics in india.

India is a country characterized by a rich cultural, religious, and political tapestry. The interplay of religion and politics in India is a complex and profoundly influential dynamic that shapes the nation’s social and political landscapes.

The Historical Context

The intertwining of religion and politics in India is deeply rooted in its historical context. The nation’s partition in 1947, based on religious lines, set the stage for religion to become a central player in political discourse. The political ideologies that emerged, such as secularism and communalism, were deeply influenced by religious considerations.

Religion in Political Discourse

Religion plays a significant role in the political discourse in India. Political parties often employ religious symbolism and rhetoric to mobilize support. This can be seen in the way political campaigns are often crafted around religious identities, with promises made to protect the interests of specific religious communities. This has led to a form of identity politics where religious affiliations often dictate political alignments.

Religious Mobilization and Vote Bank Politics

The concept of ‘vote bank’ politics has further entrenched the role of religion in Indian politics. Political parties often target specific religious communities, promising to protect their interests in return for their votes. This has created a situation where religion is used as a tool to garner political support, often leading to divisive politics and communal tensions.

The Challenges and Implications

While religion can provide a sense of identity and community, its intertwining with politics has led to a number of challenges. It has often resulted in divisive politics, fostering communal tensions and sometimes even leading to violence. The politicization of religion also undermines the secular ideals enshrined in the Indian constitution, which envisages India as a secular state where all religions are treated equally.

The Way Forward

The way forward lies in strengthening the secular fabric of the nation. This requires promoting a political culture where religion is not used as a tool for political gains. It involves fostering a sense of inclusive nationalism that transcends religious identities. Education and awareness can play a crucial role in this, helping to promote a culture of tolerance and mutual respect.

In conclusion, religion and politics in India are deeply intertwined, shaping the nation’s social and political landscapes. While this dynamic has led to challenges, it also presents opportunities for fostering a more inclusive and tolerant society. By promoting a culture of secularism and mutual respect, India can ensure that religion serves as a force for unity rather than division.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Regionalism in India

- Essay on Quit India Movement

- Essay on Proud to Be an Indian

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Essay on Indian Culture for Students and Children

500+ words essay on indian culture.

India is a country that boasts of a rich culture. The culture of India refers to a collection of minor unique cultures. The culture of India comprises of clothing, festivals, languages, religions, music, dance, architecture, food, and art in India. Most noteworthy, Indian culture has been influenced by several foreign cultures throughout its history. Also, the history of India’s culture is several millennia old.

Components of Indian Culture

First of all, Indian origin religions are Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism . All of these religions are based on karma and dharma. Furthermore, these four are called as Indian religions. Indian religions are a major category of world religions along with Abrahamic religions.

Also, many foreign religions are present in India as well. These foreign religions include Abrahamic religions. The Abrahamic religions in India certainly are Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Besides Abrahamic religions, Zoroastrianism and Bahá’í Faith are the other foreign religions which exist in India. Consequently, the presence of so many diverse religions has given rise to tolerance and secularism in Indian culture.

The Joint family system is the prevailing system of Indian culture . Most noteworthy, the family members consist of parents, children, children’s spouses, and offspring. All of these family members live together. Furthermore, the eldest male member is the head of the family.

Arranged marriages are the norm in Indian culture. Probably most Indians have their marriages planned by their parents. In almost all Indian marriages, the bride’s family gives dowry to bridegroom. Weddings are certainly festive occasions in Indian culture. There is involvement of striking decorations, clothing, music, dance, rituals in Indian weddings. Most noteworthy, the divorce rates in India are very low.

India celebrates a huge number of festivals. These festivals are very diverse due to multi-religious and multi-cultural Indian society. Indians greatly value festive occasions. Above all, the whole country joins in the celebrations irrespective of the differences.

Traditional Indian food, arts, music, sports, clothing, and architecture vary significantly across different regions. These components are influenced by various factors. Above all, these factors are geography, climate, culture, and rural/urban setting.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Perceptions of Indian Culture

Indian culture has been an inspiration to many writers. India is certainly a symbol of unity around the world. Indian culture is certainly very complex. Furthermore, the conception of Indian identity poses certain difficulties. However, despite this, a typical Indian culture does exist. The creation of this typical Indian culture results from some internal forces. Above all, these forces are a robust Constitution, universal adult franchise, secular policy , flexible federal structure, etc.

Indian culture is characterized by a strict social hierarchy. Furthermore, Indian children are taught their roles and place in society from an early age. Probably, many Indians believe that gods and spirits have a role in determining their life. Earlier, traditional Hindus were divided into polluting and non-polluting occupations. Now, this difference is declining.

Indian culture is certainly very diverse. Also, Indian children learn and assimilate in the differences. In recent decades, huge changes have taken place in Indian culture. Above all, these changes are female empowerment , westernization, a decline of superstition, higher literacy , improved education, etc.

To sum it up, the culture of India is one of the oldest cultures in the World. Above all, many Indians till stick to the traditional Indian culture in spite of rapid westernization. Indians have demonstrated strong unity irrespective of the diversity among them. Unity in Diversity is the ultimate mantra of Indian culture.

FAQs on Indian Culture

Q1 What are the Indian religions?

A1 Indian religions refer to a major category of religion. Most noteworthy, these religions have their origin in India. Furthermore, the major Indian religions are Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism.

Q2 What are changes that have taken place in Indian culture in recent decades?

A2 Certainly, many changes have taken place in Indian culture in recent decades. Above all, these changes are female empowerment, westernization, a decline of superstition, higher literacy, improved education, etc.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Your Article Library

Essay on different religions in india.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

India presents a baffling diversity in religious persuasions and faiths. Although the traditional religion of the land is Hinduism, many other faiths and belief systems, from tribal forms of religion to Buddhism, Christianity and Islam, have coexisted for centuries. They have created for themselves cultural niches within a shared space.

These faiths are indigenous (Indie) as well as introduced from outside (extra-Indic). The Indie religions have all evolved from early Hinduism, which has been undergoing changes in content and ritual practices in response to the prevailing cultural, ethno-lingual and ecological diversities in different regions of the country.

Within Hinduism, a number of sects, such as Vaisnavism and Saivism, emerged on the scene adding further diversity to the cultural mosaic. These sects have a specific geographic patterning of their own in the country. This shows how ideological differences and philosophical interpretations lead to diverse socio-cultural practices and the associated rituals based on religious faiths.

Thus it is evident that the differences in religious ideologies may lead to sect formation even within the same religion. These differences have led to the emergence of regional nuances in religious practices. In the same way, protest movements within Hinduism eventually led to the emergence of new faiths, such as Buddhism and Jainism.

These protest movements also led to reform within Hinduism. Another Indie religion—Sikhism—was genetically linked to these changes. In its original form it was a fine blend of the basic elements of Hinduism and Islam. Religious faiths which originated in West Asia, e.g., Christianity, Zoroastrianism and Islam, also found their followers in India. Initially following a sea route to India both Christianity and Islam had their early base in the littoral regions of South India, particularly the western coastal region, from where they spread into the interior parts.

Later missionary activity systematically organized by the Christian missions during the subsequent centuries, particularly the eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries, found many responsive groups among the tribes and the Hindu depressed castes. The spread of Islam In northern and western India was a later phenomenon. In fact, it followed the sequence of developments leading to the Muslim conquest of the northern parts of the country in the medieval period. Unlike the Christian missionary activity Islamic enterprise was never systematically organized.

However, the emergence of Muslim seats of power in the different regions of the country provided an added incentive to conversion. Evidently, coexistence of multiple faiths and a pervasive spirit of tolerance has been a distinguishing feature of the Indian society through the ages.

Social Expression of Religious Identity:

Although religion is a matter of personal faith, religious identity of an individual in India is often expressed at the social plane. Unlike the western world where mass celebration of the religious occasions is infrequent, more so the public display of festivities is rare, religious celebration in the oriental societies is a sociological phenomenon. The Indian society conforms to this norm. Mass festivals are common and the year is dotted with religious events, major as well as minor, which have far-reaching social implications.

In fact, in some religious groups, there are several occasions during the year when people publicly display their adherence to a certain form of religious ritual. For example, large processions are taken out with great zeal. Likewise, people offer mass prayers in mosques and churches on certain festivals.

Mass prayers are also held in mosques on every Friday. The celebration of festivals acquires dimensions which transcends the limits of the private sphere of life. They become occasions of public expression of religious identity. These practices have continued and co-existed giving strength to the pluralistic nature of India’s religion-cultural ethos.

Elements of Religious Identity:

The issue of religion, or religion-based identity, may be approached in several ways.

First, religion is a matter of faith, a personal affair and a philosophy of life of an individual or a group of individuals.

Secondly, and flowing from the first, followers of a certain religion, by virtue of their adherence to a common faith, may develop a community feeling. This leads to conscious or unconscious expression of solidarity with the followers of that religious faith. This community feeling characterizes all religious group formations.

Thirdly, a common code of social conduct based on a religious faith may lead to public expressions of a particular religious identity, e.g., dressing in a particular way, avoidance of certain items of food and mass assemblies and public demonstrations on religious occasions.

These divergent codes of conduct and socio-cultural practices eventually lead to a consciousness of religious and cultural differences. Followers of other religions are often ranked on a scale constructed in the light of a particular religious ideology and are then rated as superior, inferior or even untouchable.

If religion is a matter of personal faith, and there is little adherence to a publicly manifested code of conduct, it does not affect anybody. But if there is a public assertion of one’s religious identity expressed pronouncedly in dress ways, food ways, avoidance of or preference for certain items of food, cooking habits, eating habits, inhibitions in inter-dining and so on, a religious group acquires an identity of its own and gets differentiated from other religious groups on a social basis.

Other forms of discriminatory social behaviour follow. This promotes, on the one hand, an internal feeling of solidarity and, on the other, a feeling of division. Such divisive tendencies may acquire acute forms and may result in a variety of social conflicts. When groups are formed and perceived on religious basis social authority is often likely to be wielded by a priestly class (the authority of the church as in Roman Catholics or the authority of the Ulema as in Islam, although the two are not comparable in orientation and rigour).

This sooner or later acquires political nuances. When such a stage is reached, religion is likely to become the basis of social mobilization which eventually may lead to a social discord. The highest stage in this regimentation is reached when a state identifies itself with a particular religion and subjects the followers of other religions, or religious minorities, if any, to a discriminatory treatment. Theocratic states based on dissimilar religious formations may eventually confront each other in situations of war in an attempt to subjugate each other. Crusades were the best example of such conflicts when the contesting parties were fighting in the name of religion.

The above discussion shows that religion in the world societies has not always been purely a matter of simple faith. Actions of individuals or groups often transcend the limits of personal space. Then religion becomes a manifested basis of social differentiation.

In that role, it has far-reaching operational implications which do not always seem to hint at harmony or cohesion. At the same time, there is no gainsaying the fact that in the world society, religion as a moral philosophy has played a role of promoting harmony, peace and commitment to civilized public behaviour. The values inculcated by religious teachings are universal and reveal the essential unity of all religions.

Religion has acted as a civilizing force promoting humanism, respect for other forms of identity and a spirit of sacrifice in an Endeavour to achieve higher goals for human coexistence. Religion has induced individuals to subordinate themselves to the higher ideals of humanism and sacrifice their own comforts for the collective good of the humankind.

However, human history is also full of instances when religion-based spirit of harmony and compression has been largely ignored in order to establish the supremacy of a given religious formation. The same factors which are cohesive in a given formation become the basis of rivalry and competition between the different religious groups.

While it is true that religion promotes spiritualism, spiritual values have often been superseded by the human lust for secular authority and material well-being. Despite the religious teachings for good moral behaviour conflict between the good and the evil has continued through history.

Religion in Indian Society: Historical Background:

Let us now examine the place of religion in Indian society in its historical context. Religion is a form of social organization. While it is personalized, social expression of one’s religious identity leads to significant behavioural patterns. The attitudes adopted by different religious groups reveal that ideology is a determining force in social behaviour. People chalk out their social interaction modes in the light of the religious faith they profess. The ramifications of a differential pattern of social behaviour are seen in patterns of social interaction, celebration of festivals, organization of cultural activities, management of social space and personal manners.

Western education has brought about a certain degree of social transformation; nonetheless the hold of religious ideologies is too strong. At the same time, it is true that an enlightened class of Indians is thoroughly secular and capable of rising above the religious identities in all situations of crisis.

While Hinduism is the religion of the land, there is no one pan-Indian form of religion. In fact, Hinduism has been evolving through the ages. Moreover, it has interesting regional forms and each cultural region has its own distinguishing traits expressed in rituals, customs, ceremonies, festivals and social practices. An early form of Hinduism, based on the worship of mother goddess gradually changed into a religious form commonly referred to as Vedic Hinduism (Box 7.1).

The advent of Vedic religion led to drastic modification of the ancient faith around the middle of the second millennium B.C. While the Vedic religion remained as a superstructure, regional forms of faith based on a blending of local varieties with the newly introduced elements continued as a substratum. It is commonly known that the transformation of early Hinduism into Vedic form of religion started with the advent of the Indo-Aryan language, particularly Sanskrit, which became the vehicle for this change. The Vedic theology according to one interpretation “begins with the worship of the things of heaven, and ends with the worship of the things of earth”.

The gods of heaven included Surya, Savitar and Bhaga, which really implies the worship of sun in different forms. Then was the worship of the gods of the intermediate sky, Indra, and earth-born gods, Agni, Soma, etc. Gradually, the concept of sraddha, or periodical feast of the dead, led to the emergence of the cult of sacrifice.

The Rig-Veda recorded the practices and the rituals associated with the different forms of worship as the Vedic religion spread to other regions of India from its homeland in the Sapta-Sindhava region. It acquired distinct regional forms. The Hindu pantheon recognized a Super Being, an Atman or Parmatman which permeated all beings, including the gods they worshipped.

The Vedic theology was not a fixed set of ideas. In fact, it continued to evolve from the period of the Vedas to that of the Brahmanas and the Upanishads. During these evolutionary stages significant changes were registered in the Hindu philosophy and the very concept of gods underwent a change. As Brahmanism became rigid protest movements against the ascetic fraternity of the Brahmans were launched. These protest movements eventually led to the emergence of new faiths, such as Buddhism and Jainism. Buddhism was a heretical movement. Basically, it was a reformation movement and a protest against the ascendancy of the priestly class.

Buddhism, in its original form, was not a religion as such. It was simply a monastic organization. It insisted on a non-Brahmanic order. In its historical context, it appears that it was a culmination of the ongoing conflict between the Brahman and the Kshatriya. In the background of Magadha one can understand that the Kshatriya was in a dominating position. The fact that these protest movements originated in Magadha explains the nature of the caste conflict so peculiar of the region. Early Buddhism tried to disentangle people from the Brahmanical cult.

Among the basic elements of Buddhism were the sanctity of animal life (ahimsa) and the craving for salvation (nirvana). However, the early Buddhist gospels were a continuation of the old Hindu beliefs and ethics. Buddha laid an extraordinary stress on the issue of nirvana. It is a remarkable feature of India’s religious tolerance that in spite of its opposition to Brahmanical supremacy Buddhism co-existed with Brahmanism for more than a millennium. In its early days Buddhism benefited from its practice of holding sangha (congregation of monks or monastic order) in the propagation and consolidation of Buddhist faith.

Through these congregations Buddhist preachers redefined their position vis-a-vis the basic philosophical issues. It is also believed that Buddhism also benefited when the state adopted it perhaps as a state religion under Asoka. Asoka’s role in the propagation of Buddhism to other parts of the world, such as Sri Lanka and Central and Eastern Asia, is too well known. With the passage of time Buddhism got divided into two schools of thought—Hinayana and Mahayana.

The Mahayana school which developed under Kanishka promised salvation to the entire universe as against the Hinayana concept of salvation of the few. It is a known history that Buddhism started declining in its homeland while it flourished abroad. Hiuen Tsiang’s visit to India during 629-45 A.D. confirmed its general state of decay. It is understood that the main cause of this decline was Brahmanical revivalism attended by a reformation movement within Brahamanism.

The rise of Brahamanism is attributed to the efforts of Kumarila Bhatta, a Brahman preacher of Bihar and his disciple, Sankaracharya. There were other factors too. For example, the Buddhist creed was based on a high standard of morality, much higher than the level of common people.

Moreover, rejection of the sacrificial cult and abstraction of the concept of god acted as distracting factors, hastening the decay of Buddhism. The common Hindu was more interested in gods which were concrete objects of worship. Thus, the decline of Buddhism may be an outcome of the resurgence of Brahamanism as well as the natural decay of the Buddhist faith among the masses.

The ascetic fraternity of the Brahmans led to another protest movement which came to be known as Jainism. The movement emerged in the lifetime of Buddha himself. Like Buddha, its leader Vardhamana, popularly known as Mahavira Jina, also came from Magadha. The Brahman authority was so strong that these protest movements gained popularity.

Jainism also aimed at nirvana, although the Jain concept of nirvana was a little different than in Buddhism. Within Jainism a division between Svetambara and Digam-bara took place at an early stage. Svetambara originated in the northern and the western region of the country while Digambara had its base in the south. The Digambaras followed the principle of nudity. A third sect which consisted of Dhondias also emerged. Jainism received state patronage under the Chalukyas of Gujarat and Marwar. With this began the process of construction of famous Jain temples in different regions of the country. Unlike Buddhism, Jainism did not suffer a setback.

The Jain order survived without much of a conflict, external or internal. Today, the main Jain sanctuaries are situated in the isolated hills, such as Parasnath in Bengal, Palitana in Kathiawar and Mount Abu in Rajasthan. The census records show a successive decline in the numerical strength of Jain population. It may also be noted that the home of Jainism today lies in Gujarat and adjoining Marwar region of Rajasthan where the followers have been drawn mostly from among the trading communities and not in Bengal, Magadh or Orissa where the Jain faith originated.

Reform movements, initiated by Buddha and Mahavira, resulted in new formulations of ritual as well as social customs. There was a phase, although short-lived, in Indian history when the tide of Buddhism seemed to submerge the Hindu faith. Buddhism had its sway over a vast region from Bengal to Kashmir and from the Himalayas to Kaveri till a new Brahmanical upsurge brought an equally spectacular change.

The protest movements represented by Buddhism and Jainism also led to reformation within Brahmanism. These reform movements eventually resulted in the emergence of a new form of Hinduism which is currently in practice in all parts of India. Its basic elements consist of use of one sacred language (Sanskrit), through which the ritual is practised, pilgrimage to holy places and the rule of a priestly class which determines the life of the ordinary Hindu men and women. The religion of the peasant, although simpler in its theological content, is equally controlled by the Brahamanical authority.

In the course of time, two sects, viz., Vaisnavism and Sivaism emerged among the Hindus. While the former focuses on the worship of Visnu, the latter on the worship of Siva. Each sect has its own order of rituals performed on specific occasions. However, both the gods are worshipped by the common Hindu folk throughout the country.

Both Siva and Visnu are mentioned in the Mahabharata as two separate gods, and at the same time each represented by the other. The Hindu trinity of gods consists of both of them as well as a third god, Brahma, who was treated as the chief of the gods in the epic period. The modern belief is that while Brahma occupies a central position, he is represented by both Visnu and Siva and in their worship Brahma is also worshipped indirectly.

As pointed out earlier, a remarkable feature of Hindu society is a spirit of tolerance and accommodation of multiple forms of faith. It was because of this spirit of tolerance that other faiths which came from outside flourished. Christianity and Islam came from outside and the people embraced these faiths without much of a social conflict.

This has been a historic tradition that successive penetration by non- Indic religions was not resisted. Political conflicts were there between the local kingdoms and the invaders, but they did not result in religious conflicts. Gradually, these religious faiths created for themselves niches in the Indian social space.

As indicated earlier, among the Semitic religions, the earliest to make an impact in India was Christianity. Syrian Christians appeared on the west coast of India in the very first century of the Christian era. Later, in the seventh century A.D., Arab traders brought the message of Islam to the people living on the west coast of India. This happened much before the Muslim (political) conquest of northern India.

It is thus obvious that the religious composition of the Indian population has been changing with conversions from one faith to the other. The spatial patterns of distribution of different religious groups were also greatly modified by large scale migration following the partition of India in 1947. Partition brought about a significant change in the distribution and relative strength of different religious faiths in north western, northern and north eastern India.

Spatial Distribution of Religious Groups :

The different religious communities of India include major groups, such as the Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists and the Jains, as well as minor religious faiths, such as Jews and Zoiroastrians. Moreover, several tribal communities continue to retain faith in tribal religions based on totemism and animism. The Hindus account for 82 per cent of the total population and are the largest religious group in the country. However, in some districts, Muslims, Christians, Sikhs or the Buddhists are more numerous than the Hindus. Muslims are the largest minority group and account for 12.12 per cent of the total population.

Christians constitute 2.3 per cent of the population and the Sikhs 1.94 per cent. Buddhists and Jains are numerically insignificant accounting for 0.7 and 0.5 per cent of population respectively. It may be noted that while Hindus are generally found everywhere, other religious groups are concentrated in a few pockets only (Table 7.1).

It may be useful to identify the main patterns in the spatial distribution of the major religious groups in order to understand the role of religion in defining the parameters of Indian social space and the socio- cultural regionalism based on it.

Related Articles:

- Classification of Religious Groups in India: Indigenous and Extra-Indic

- Religious Movements in India

No comments yet.

Leave a reply click here to cancel reply..

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Advertisement

Supported by

news analysis

Why Did Modi Call India’s Muslims ‘Infiltrators’? Because He Could.

The brazenness of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s vilification of India’s largest minority group made clear he sees few checks at home or abroad on his power.

- Share full article

Modi Calls Muslims ‘Infiltrators’ in Speech During India Elections

Prime minister narendra modi of india was criticized by the opposition for remarks he made during a speech to voters in rajasthan state..

I’m sorry, this is a very disgraceful speech made by the prime minister. But, you know, the fact is that people realize that when he says the Congress Party is going to take all your wealth and give it to the Muslims, that this is just a nakedly communal appeal which normally any civilized election commission would disallow and warn the candidate for speaking like this.

By Mujib Mashal

Reporting from New Delhi

Prime Minister Narendra Modi, his power at home secured and his Hindu-first vision deeply entrenched, has set his sights in recent years on a role as a global statesman , riding India’s economic and diplomatic rise. In doing so, he has distanced himself from his party’s staple work of polarizing India’s diverse population along religious lines for its own electoral gain.

His silence provided tacit backing as vigilante groups continued to target non-Hindu minority groups and as members of his party routinely used hateful and racist language , even in Parliament, against the largest of those groups, India’s 200 million Muslims. With the pot kept boiling, Mr. Modi’s subtle dog whistles — with references to Muslim dress or burial places — could go a long way domestically while providing enough deniability to ensure that red carpets remained rolled out abroad for the man leading the world’s largest democracy.

Just what drove the prime minister to break with this calculated pattern in a fiery campaign speech on Sunday — when he referred to Muslims by name as “infiltrators” with “more children” who would get India’s wealth if his opponents took power — has been hotly debated. It could be a sign of anxiety that his standing with voters is not as firm as believed, analysts said. Or it could be just a reflexive expression of the kind of divisive religious ideology that has fueled his politics from the start.

But the brazenness made clear that Mr. Modi sees few checks on his enormous power. At home, watchdog institutions have been largely bent to the will of his Bharatiya Janata Party, or B.J.P. Abroad, partners increasingly turn a blind eye to what Mr. Modi is doing in India as they embrace the country as a democratic counterweight to China.

“Modi is one of the world’s most skilled and experienced politicians,” said Daniel Markey, a senior adviser in the South Asia program at the United States Institute of Peace. “He would not have made these comments unless he believed he could get away with it.”

Mr. Modi may have been trying to demonstrate this impunity, Mr. Markey said, “to intimidate the B.J.P.’s political opponents and to show them — and their supporters — just how little they can do in response.”

The prime minister sees himself as the builder of a new, modern India on the march toward development and international respect. But he also wants to leave a legacy that is distinctly different from that of the leaders who founded the country as a secular republic after British colonial rule.

Before joining its political offshoot, he spent more than a decade as a cultural foot soldier of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, or R.S.S., a right-wing organization founded in 1925 with the mission of making India a Hindu state. The group viewed it as treason when an independent India agreed to a partition that created Pakistan as a separate nation for Muslims, embraced secularism and gave all citizens equal rights. A onetime member went so far as to assassinate Mohandas K. Gandhi in outrage.

Over his decade in national power, Mr. Modi has been deeply effective in advancing some of the central items of the Hindu-right agenda. He abolished the semi-autonomy of the Muslim-majority state of Jammu and Kashmir. He enacted a citizenship law widely viewed as prejudiced against Muslims. And he helped see through the construction of a grand temple to the Hindu deity Ram on a plot long disputed between Hindus and Muslims.

The violent razing in 1992 of the mosque that had stood on that land — which Hindu groups said was built on the plot of a previous temple — was central to the national movement of Hindu assertiveness that ultimately swept Mr. Modi to power more than two decades later.

More profoundly, Mr. Modi has shown that the broader goals of a Hindu state can largely be achieved within the bounds of India’s constitution — by co-opting the institutions meant to protect equality.

Officials in his party have a ready rebuttal to any complaint along these lines. How could Mr. Modi discriminate against anyone, they say, if all Indian citizens benefit equally from his government’s robust welfare offerings — of toilets, of roofs over heads, of monthly rations?

That argument, analysts say, is telling in showing how Mr. Modi has redefined democratic power not as leadership within checks and balances, but as the broad generosity of a strongman, even as he has redefined citizenship in practice to make clear there is a second class.

Secularism — the idea that no religion will be favored over any other — has largely been co-opted to mean that no religion will be allowed to deny Hindus their dominance as the country’s majority, his critics say. Officials under Mr. Modi, who wear their religion on their sleeves and publicly mix prayer with politics, crack down on public expressions of other religions as breaching India’s secularism.

While right-wing officials promote conversion to Hinduism, which they describe as a “return home,” they have introduced laws within many of the states they govern that criminalize conversion from Hinduism. Egged on by such leaders, Hindu extremists have lynched Muslim men accused of transporting cows or beef and hounded them over charges of “love jihad” — or luring Hindu women. Vigilantes have frequently barged into churches and accosted priests they believe have engaged in proselytizing or conversion.

“What they have done is to create a permissive environment which encourages hate and valorizes hate,” said Harsh Mander, a former civil servant who is now a campaigner for social harmony.

In reference to Mr. Modi’s speech on Sunday, he added: “This open resort to this kind of hate speech will only encourage that hard-line Hindu right in society.”