The India growth story – the role of private equity and the 3D reset

India is uniquely positioned to benefit in the context of the 3D reset. We explore the dynamic private equity landscape and the role it plays in delivering India’s full growth potential.

The private equity market in India represents a deep, varied opportunity set plugged into many of the sectors catalysing India’s vibrant growth. And while public markets remain dominated by legacy industries, it is private markets where the companies leading India’s growth reside.

India’s private equity industry is rapidly maturing. As capital flows into the market, the pool of private equity management talent has deepened, and grown increasingly specialised. In the coming decades, we expect India to emerge as a genuine global power and believe investors seeking to participate in its rise cannot overlook private equity.

Here we explain the shape of India’s private equity industry today, and how we expect it to evolve. We also dig into why the Indian economy is uniquely positioned to benefit from the themes Schroders Capital expects to shape the next phase of the global economy. Decarbonisation, demographics and deglobalisation – what we collectively call the “3D Reset” – are set to propel the Indian economy to new heights, and the private equity industry will play a crucial role in its progress.

India private equity: Deep, maturing market, with exposure to key growth sectors

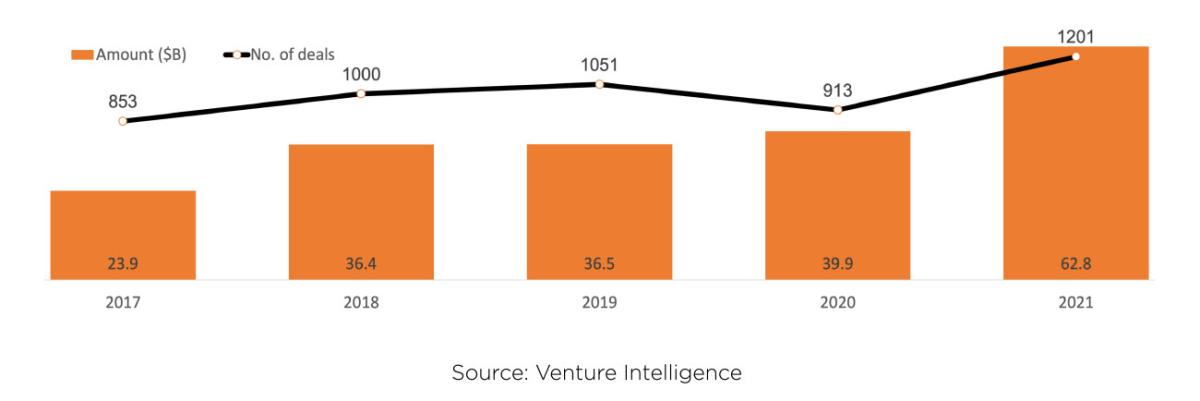

The private equity market in India has shown remarkable growth in recent years, with average annual investment volume of approximately $40 billion over the last five years. While there has been a decline in investment volume from the peak in 2021, this is in line with the global post-pandemic normalisation in deal-making activity. Nevertheless, private equity investments in India remain substantial, reflecting the continued interest and confidence of investors in the country's favourable economic conditions and growth potential.

Deal volume has grown by over 4x in the last decade

In the past, the private equity market in India has primarily focused on growth, non-control transactions, while buyouts represented a smaller part of the market. This was due to several factors, including the reluctance of family-owned businesses to engage with private equity firms, limited availability of managerial talent, and regulatory constraints on acquisition debt financing.

However, there has been a notable shift over the last decade, with the share of buyout transactions increasing from just 5% of investments in 2010 to 19% of investments in 2022. Control deals, involving collaboration with family-owned businesses, are gaining momentum as successful outcomes have been achieved. Furthermore, the Indian corporate ecosystem has matured, resulting in greater availability of managerial talent both domestically and globally.

India’s private equity market is mostly growth-stage, yet buyouts are on the rise

Venture Capital also represents a meaningful share of private equity activity. India has a vibrant start-up ecosystem, home to the third highest number of unicorns globally. This is driven by a culture of entrepreneurship, high-skilled talent, and rapid digital adoption. Indian startups are global leaders in enterprise software and fintech. They are also making strides in emerging deep tech areas such as space tech, an industry that has seen a surge in activity following India’s recent moon rover landing.

Most of India’s fast-growing private companies operate in precisely the sectors that stand to benefit from India’s growth trajectory, for example, consumer, healthcare, and technology. India’s public markets, conversely, are dominated by older companies in traditional sectors. Financial Services and Industrials represent 70% of the S&P BSE SENSEX market capitalisation while Consumer & Retail and Technology represent almost 60% of private equity deal volume.

Fast-growing sectors dominate private equity while legacy sectors prevail in private markets

Some investors cite concern about the availability of exit strategies for private-equity-backed companies in India. However, there have been a broad mix of exit channels. In 2022, 30% of exits were to strategic buyers, 40% to private equity buyers, and 30% through IPOs. The strong representation of IPOs reflects the recent easing of capital market regulations aimed at encouraging listings from companies on the path to profitability. We expect the diversity in exit types to continue, bolstered by an expanding investor base, further lifting of IPO listing restrictions, and strong interest from global corporates.

The most active private equity firms in India are global firms investing via regional rather than dedicated India funds. However, fundraising from dedicated India funds has quadrupled over the last decade, growing from $1.9 billion in 2012 to $8.0 billion in 2022. The average fund size has also increased from $86 million in 2012 to $160 million in 2022. Today, there are more than 200 private equity firms investing from dedicated India funds.

There has also been heightened interest from investors in Indian rupee denominated investments. Total AUM held by Category II Alternative Investment Funds (AIFs) grew by 45% year-on-year in 2022, highlighting the growing appeal amongst local investors for local onshore regulated structures. AIFs are a type of pooled investment vehicle incorporated in India, investing in alternative assets. Category II AIFs consist of private equity, private credit, and real estate funds. We expect India to follow China’s trajectory of substantial growth of the local market. The impressive growth of RMB denominated fundraising, which in 2022 totalled $300 billion, serves as a compelling indicator of the potential scale that India’s local market could achieve.

The 3D Reset and technology revolution create tailwinds in India

The global themes of decarbonisation, deglobalisation, demographic change, and the ongoing technology revolution continue to create challenges as well as opportunities across the spectrum of private asset investments. India is benefitting from these secular shifts. India has a young and growing population, its strong manufacturing base is attracting global corporations as a key China plus one partner, and the government is leaning into the energy transition with generous support for clean energy initiatives.

These are just some of the factors driving India’s projected ascent to become the third largest economy by 2028 with expected growth of 7% per annum. Consumer, tech-enabled business services, and healthcare are at the forefront of this growth, and private equity’s strong focus on these sectors makes it an attractive way to participate in India’s transformation.

The rise of the Indian consumer

While most large economies are grappling with demographic trends of population decline and labour shortages, India has attractive demographics with a median age of just 29 and a highly skilled and digitally enabled population. India’s GDP is expected to reach $6 trillion by 2030 and private consumption contributes roughly 60% of GDP, indicating a sizeable opportunity for consumer-focused companies. Furthermore, with online penetration in retail under 10%, there is significant white space for retail growth, especially with the rise of digital payments, improved digital accessibility, and a growing middle class.

Case study: Consumer sector

Schroders Capital made a direct investment in India's leading eyewear company in 2016. Since the investment, the company has scaled in India and beyond, tapping consumers in Asia and the Middle East. With rising digital adoption, the company has boosted its online presence while also expanding its retail footprint, evolving into an omnichannel player. Its store count has grown from 100 to more than 1,500 stores globally. Furthermore, by investing in manufacturing capacity and operational efficiencies, the company has increased sales of its own products, driving higher profit margins.

The opportunity in India’s long history as a tech enabled market leader

The IT sector has long been a vital part of India's economy. India has a tech workforce 10 times larger than that of the US and each year adds 10 million graduates to its talent pool. The trends of demographic change, deglobalisation, and decarbonisation have fuelled India's technology industry, especially in areas such as fintech and B2B marketplaces.

India is the third largest fintech market , surpassed only by the US and China. The catalyst for fintech innovation has been the rapid growth in mobile usage. This is underpinned by some of the world's lowest data rates, and world-leading digital infrastructure such as biometric digital IDs (Aadhaar) and instant real-time payments (Unified Payments Interface). Although payments initially drove this momentum, innovations in lending, wealth-tech, and blockchain technologies have also emerged.

Deglobalisation tendencies have raised India's status as a key global manufacturing hub. This shift is exemplified by the 'Make in India iPhone era', with an anticipated 25% of Apple’s iPhone production moving to India. But with this expansion in manufacturing, the demand for efficient supply chain management tools has increased. This has led to the emergence of digital-first B2B marketplaces that foster greater transparency, quality control, and efficient supply-demand matching.

There has also been substantial innovation in climate technologies, particularly in renewable energy and electric mobility. India will need to significantly expand its solar and wind capacity, requiring investments in equipment and components such as wind turbines, solar photovoltaic modules, and storage batteries. Two-wheelers have been a particular focus for innovation, as they account for 70% of vehicles in India, yet only 4% of them are currently electrified.

Case study: Tech enabled business services

Schroders Capital backed one of India’s leading B2B managed marketplaces in 2019, addressing the demand for efficient supply chain tools amid rapid economic growth. The company is transforming supply chain operations for SMEs through two core services. Its digital vendor management platform streamlines raw material procurement workflows, including order placement, invoicing, and real-time fulfilment tracking.

It also offers embedded financing, linking SMEs to lenders and providing analytics to inform credit scoring. Since inception in 2016, the company has expanded the marketplace to 500 enterprise customers and 8,000 vendors. It has also diversified into new industries and enhanced its analytics with AI.

Healthcare in India will be driven by private equity

The Indian healthcare sector is poised for growth, offering attractive opportunities for private capital. Healthcare delivery remains underserved, characterised by low insurance adoption, low public spending, insufficient infrastructure, and a lack of doctors.

Innovations such as telemedicine, insurtech, and AI-based diagnostics have emerged to solve some of these challenges, enabled by the digitisation of health records and cheap access to data. Healthcare spending is set for rapid growth over the coming years, presenting opportunities both in traditional market-leaders and digital-first business models.

The pharmaceuticals sector also shows strong potential for growth. India is a global leader in generics and vaccine manufacturing, accounting for 20% of global generic medicine exports and 60% of global vaccines production, according to research by Invest India. Growth tailwinds include the large and growing talent pool, diversification in supply chains away from China, and regulatory enablers such as Production Linked Incentives and the National Biopharma Mission. There is also vast potential for digitisation in pharma manufacturing, such as the use of AI in drug development.

Case study: Healthcare

Schroders Capital invested in one of India’s largest pharmaceutical contract development and manufacturing (CDMO) companies in 2021. The global CDMO market, which represents a $140 billion opportunity, is projected to grow at 6.9% over the next few years, according to Grand View Research. Indian CDMO players are well-positioned to capture this growth due to a large population for clinical trials and availability of technical expertise at competitive rates.

The company specialises in topical semi-solid formulations, which is a segment with high regulatory and technical entry barriers. Since the investment, the company has forward integrated into proprietary formulations, securing more than 21 US Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDA) approvals, and has established a front-end presence in the US and India. The company has also strengthened its R&D capabilities through expanding from generics to specialty topical products.

Improving diversification with an India private equity strategy

In addition to the attractive return potential, an India private equity strategy has been shown to add diversification to a global private equity portfolio.

We analysed investment results across our global private equity strategies. Interestingly, India private equity exhibited by far the lowest correlation, with a correlation coefficient of only 0.14 when compared for example to our Europe private equity strategy.

What leads our India private equity strategy to exhibit low correlation? India’s low export dependency and large domestic market cause company performance to be more closely tied to India’s intrinsic economic performance than the global macroeconomic cycle. Furthermore, our private equity strategy in India focuses on the growth stage, which is typically less export-dependent and uses less leverage. Performance is driven predominantly by winning local market share, product extension, and operational efficiencies.

An allocation to India private equity adds diversification

India's vibrant growth story, driven by demographic advantages, digital adoption, and a thriving entrepreneurial ecosystem, offers a compelling opportunity for private equity investment. The maturing private equity market, deeply embedded in sectors fuelling India's growth, provides a strong platform to access this potential. The country's ability to effectively harness the 3D Reset is set to boost its economy and private equity industry. By focusing on high growth sectors such as consumer, tech-enabled business services, and healthcare, we believe an investment strategy focused on India is not only attractive but also adds valuable diversification to a private equity portfolio.

Subscribe to our Insights

Visit our preference center, where you can choose which Schroders Insights you would like to receive

Important information

The views and opinions contained herein are those of Schroders’ investment teams and/or Economics Group, and do not necessarily represent Schroder Investment Management North America Inc.’s house views. These views are subject to change. This information is intended to be for information purposes only and it is not intended as promotional material in any respect.

Contact Schroders

- Media Contacts

- Worldwide locations

Please consider a fund's investment objectives, risks, charges and expenses carefully before investing. The Schroder mutual funds (the “Funds”) are distributed by The Hartford Funds, a member of FINRA . To obtain product risk and other information on any Schroders Fund, please click the following link . Read the prospectus carefully before investing. To obtain any further information call your financial advisor or call The Hartford Funds at 1-800-456-7526 for Individual Investors. The Hartford Funds is not an affiliate of Schroders plc.

Schroder Investment Management North America Inc. (“SIMNA”) is an SEC registered investment adviser, CRD Number 105820, providing asset management products and services to clients in the US and registered as a Portfolio Manager with the securities regulatory authorities in Canada. Schroder Fund Advisors LLC (“SFA”) is a wholly-owned subsidiary of SIMNA Inc. and is registered as a limited purpose broker-dealer with FINRA and as an Exempt Market Dealer with the securities regulatory authorities in Canada. SFA markets certain investment vehicles for which other Schroders entities are investment advisers.

For illustrative purposes only and does not constitute a recommendation to invest in the above-mentioned security/sector/country.

Schroders Capital is the private markets investment division of Schroders plc. Schroders Capital Management (US) Inc. (‘Schroders Capital US’) is registered as an investment adviser with the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).It provides asset management products and services to clients in the United States and Canada.For more information, visit www.schroderscapital.com

SIMNA, SFA and Schroders Capital are wholly owned subsidiaries of Schroders plc.

- Privacy Policy

- Important Information

- Social Media Guidelines

- Whistleblowing

- Program Overviews

- Stackable Credential Program

- Digital Assets Microcredential

- Private Debt Microcredential

- Fundamentals of Alternative Investments

- Financial Data Professional Charter

- Chapter Events

- Industry Events

- Thought Leadership

- Capital Decanted Podcast

- Educational Alpha Podcast

- Chronicles Newsletter

- Multimedia Library

- Publications

- Academic Partners

- Association Partners

- DEI Initiative

- CAIA Foundation

- Jobs at CAIA

- Official Merchandise

The Rise of India’s Private Equity Market

Download Report

India has reached a pivotal arc in its economic growth story, offering up broad reaching and significant investment opportunities. A key component is India’s Private Equity and Venture Capital (PEVC) sector, where unprecedented attention is leading to burgeoning growth and accompanying fruitful prospects.

This Is India’s Era

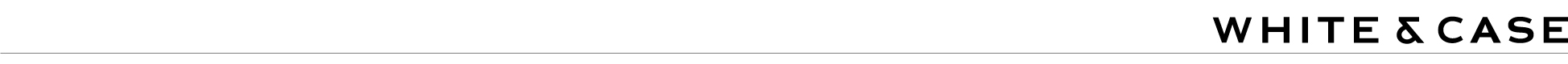

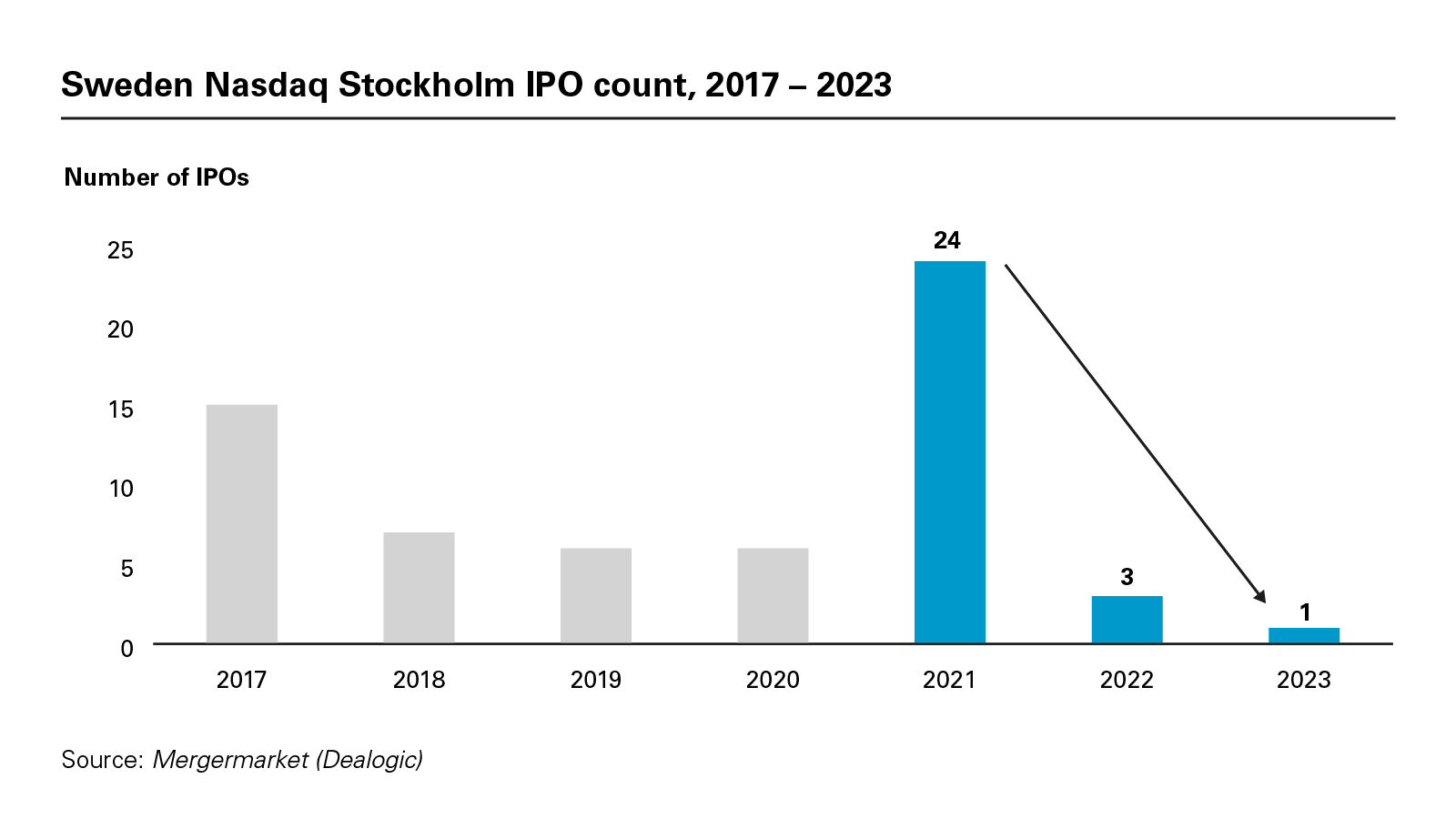

Private equity and venture capital investments by year.

India: A Compelling Story

In “CAIA Insights: The Rise of India’s Private Equity Market,” we showcase insights, spotlight opportunities, and summarize our call to action for this fast- evolving sector.

Read our new report, which includes commentary penned by leading PEVC industry specialists, to gain actionable intelligence and be informed.

©2024 Chartered Alternative Investment Analyst Association®

A business journal from the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania

Private Equity in India: What Excites Investors?

February 7, 2019 • 17 min read.

Despite obstacles, private equity in India is creating jobs and delivering real growth, according to investors at a recent Wharton India Economic Forum.

- Finance & Accounting

The private equity industry in India has evolved over the past two decades from nascent levels to a size and sophistication that global investors find attractive. PE investors in the country also find it encouraging that more teams of professional managers are available than earlier to run the businesses they target. Outcomes at those companies are decidedly better when those managers have some equity skin in the game.

Yet, India’s PE industry faces hurdles such as the absence of a well-developed capital market that would allow firms to leverage their equity with borrowings and thus put more money to work in the businesses they target. Regulatory obstacles and sudden changes to government policies are also common, and PE investors have learned to anticipate those. They also have the occasional brush with opacity or integrity issues with the existing managements at some of their target firms. A panel of executives heading the Indian arms of global of PE investment firms discussed those and other trends at the Wharton India Economic Forum held in early January in Mumbai, adding that they shared those views in their personal capacity, and not on behalf of their companies.

“The PE industry in India is maturing, but there is still plenty of room to grow,” said Vinay Nair, founder and chairman of 55ip, an investment services firm that counsels financial advisors and wealth managers on asset allocation strategies. Nair, who moderated the panel discussion, is also a visiting professor at Wharton and at the MIT Sloan School of Management, and an advisor to venture capital funds and fintech companies. He said that in 2004, when he started teaching a private equity class at Wharton, PE investments in India were under $2 billion annually, but have since grown to about $30 billion currently.

Over the last two decades, the PE industry in India has evolved to granular levels where investments can be segregated as seed capital, venture capital, growth private equity or buyouts, according to Shweta Jalan, managing director overseeing the India operations of Boston-based PE investment firm Advent International. As a “fast-growing emerging economy, India offers big opportunities for PE investments,” she noted. The market niche for buyouts of entire firms, in particular, has expanded in the last five-six years, with “control transactions,” where investors want to have a say in the management of their target firms, she said.

Amit Dixit, senior managing director and head of private equity at Blackstone India, identified three broad trends in India’s PE industry. One, deal sizes are getting bigger, he said, while acknowledging that he might be biased because his New York-headquartered firm tends to focus on relatively large transactions. “When we started in India 12 to 13 years back, it was rare to find a deal of $100 dollars or more,” he said. However, today, deals of $100 million each account for more than 70% of the total value of transactions, and 25% of those by volume, he added.

Second, Dixit saw a surge in India in control-oriented transactions, and noted they account for about a fifth of the total market by value. “What’s driving that is many of the founders of businesses, or first-generation families, don’t have succession plans in place, or their children are not willing or capable to take over the businesses,” he said. That setting opens up opportunities for professional owner-managers to buy those businesses.

Alongside, Indian companies have faced significant pressure in recent years to deliver decent returns on equity and reduce debt overhang, forcing them to shed non-core assets. “Even the largest conglomerates in India are focusing on the core and divesting non-core assets,” Dixit said. “That makes private equity the logical owner of the non-core assets they want to shed. Those two underlying drivers are making the market quite active for control transactions.”

“The talented management teams are not working for families; they would prefer to work for a professional owner who’s not only paying them a salary but also sharing in the wealth created.” –Amit Dixit

The third trend in India’s PE industry is that while it is not as competitive as, say, the U.S. or China, it is “a well-discovered market,” Dixit noted. “It’s rare now that you would buy low or sell high. You may get lucky once in a while, but chances are you may have to buy somewhat at a reasonable price and sell also somewhat at a reasonable price.” He noted that prior to 2007, India was “a classic stock pickers market,” and that the price-to-earnings ratio was below 10 for many listed companies. “Now you rarely see that.”

A Growing Community

That narrower price arbitrage window — thanks to more developed PE investing markets — could mean smaller returns for investors, unless they are able to significantly boost profits with better performance. “You have to have capability as a private equity firm to improve the profit performance of the company,” said Dixit. In order to achieve that, PE investors look to recruit people with the relevant operating backgrounds — not just investing backgrounds — to improve the EBITDA (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization) or the profit of the company.

“You are seeing a lot of operating talent now working with private equity firms, either at their companies or as operating partners or as executives-in-residence,” he added. “A huge community of private equity operators is emerging. We ourselves have a community of about 60 such operators whom we rely on when we take ownership of a company.”

Without doubt, PE investors place strong emphasis on the quality of the management teams they deploy to run the businesses in which they invest. “When we find professional teams who have entrepreneurial desire and the passion to build a business, we view it more as a partnership,” said Vishal Mahadevia, managing director of Warburg Pincus India.

“The hope is if the business does well, and we all do well, the team should make a ton of money,” said Mahadevia. “That is how we structure our deals with startups, with teams, and go out and buy businesses. We see so many more teams willing to do that in India than 10-15 years ago, when you wouldn’t even find a professional team willing to join a private equity-backed company because they figure it wouldn’t be in business very long.”

“The quality of the management team is the single biggest judgment call you have to make on the investment,” said Dixit. “Also, with the competition model, the same individual behaves very differently when they are a manager versus an owner. The owner behavior is what you want to drive and not the manager behavior. And the way you drive owner behavior is making them your partner and sharing your equity with them, which is a fundamental difference between a family ownership and a private equity ownership.”

According to Dixit, PE investors have created new sets of opportunities for talented managers that wouldn’t have existed in the earlier environment. “Value creation has been happening in India for the last 50 years by talented professionals, but they were working for families and had no equity in the game,” he said. “What’s changing now is we have come into the game. The talented management teams are not working for families; they would prefer to work for a professional owner who’s not only paying them a salary, but also sharing in the wealth created.”

In fact, the “most dramatic” change in India’s PE setting in the past decade has to do with “the quality of the entrepreneur,” said Mahadevia. He saw the emergence of “the professional entrepreneur,” who is typically “someone who’s been a professional manager in a conglomerate for many years and wants to go out, buy a business, or create and own a company,” but doesn’t have his or her own capital. “Private equity would back them, help them buy something, improve it, turn it around and then create a better company which is hopefully more valuable,” he said.

Mahadevia recalled that two decades ago, when private equity was in its inception in India, the public market was the only source of capital for entrepreneurs, and so most companies tended to be publicly listed. “For the first decade, we were investing in a private-equity type of transaction in an illiquid public company.” The evolution of the PE environment since then has led to larger-scale transactions and more control transactions. Going forward, he said the PE industry in India “needs a new ecosystem of entrepreneurs and managers whom we are able to back.”

“You have to believe that stuff will happen every once in a while and really make it very hard, and you just have to be prepared.” –Manas Tandon

The other big change has to do with “the value that we as investors ascribe to quality of governance, quality of entrepreneurs and the kind of people we partner with,” said Manas Tandon, managing director and head of India operations at Partners Group, a global private equity investment firm based in Baar, Switzerland. “Almost invariably, you see high-quality businesses and high-quality entrepreneurs being funded now.”

Nair noted that those trends “are largely consistent with the maturity of an evolving private equity industry.” In addition to PE investors executing more transactions where they gain management control of their target firms, there has also been a dispersion in the size of deals, making room beyond large deals for smaller deals, he said.

Uniquely Indian Challenges

Jalan added a note of caution to Tandon’s enthusiastic assessment of management quality at Indian PE targets. “It is a given that the governance is good, and integrity is high,” she said. “The one thing that is taken for granted in many other parts of the world is integrity of your partner, the promoter or the management team. In India, that is something you just have to double-check the day you sign the deal.”

It helps that private equity investors bring in safeguards with forensic auditors “who not only look at the numbers but even the quality of partners, their history, their history of partnerships, dealings with vendors, customers and their track record,” said Jalan. “We’ve had a bunch of very difficult learning experiences where companies have gone belly up or there have been huge integrity issues, which have resulted in loss of capital for the industry as a whole.”

At the same time, PE investors in the country face “structural constraints” such as the inability to raise debt and thereby boost the total amount of money they could deploy in their target firms, said Jalan. “Leverage is not available in India as it is in the West. We don’t get that advantage, so our money has to work doubly hard to make returns similar to what our peers do in the U.S.”

“A lot of private equity in India is about creating jobs and growing business. [PE firms] are not about [boosting] profitability by cutting costs; there is real growth.” –Manas Tandon

India’s regulatory mechanisms are among the structural challenges PE investors face, said Jalan. She referred to a 2006 deal where her firm Advent International and Temasek Holdings of Singapore, another private equity investor, bought a 34.37% equity stake in Crompton Greaves Consumer Electricals Ltd., a prominent Indian maker of fans, lights, pumps and other home appliances. They had bought that stake for Rs. 2,000 crores ($300 million) from Avantha Group, which belongs to the promoter group of Crompton Greaves, the Thapar family.

In the Crompton deal, Jalan said the investors had to secure approval from eight regulatory bodies. They included the Competition Commission of India, the Reserve Bank of India (India’s central bank), the Securities and Exchange Board of India (India’s capital markets regulator), the National Stock Exchange, and the courts, because it involved a demerger proposal at the parent company’s end. “You still have to navigate a lot of those hoops to get to do good transactions in India. It takes a long time for you to be able to get to the end game.”

Jalan saw imperfections also in price discovery in India. “At every point in time you feel valuations are high, and that is definitely a big challenge in the industry,” she said, although she acknowledged that such issues are common across geographies. Unrealistically high valuations happen to be a more acute challenge with respect to consumer goods companies, an area in which Advent International specializes, she added.

In addition to regulatory challenges, Tandon pointed to a Murphy’s Law type of a situation that PE investors have to face in India. He recalled saying to a colleague, “Anything that can go wrong will go wrong,” and his colleague’s response: “Twice.”

“Over the next decade or two, private equity is going to be a fantastic asset class – for investors, for professionals, and more importantly for the folks that make us all smart – the entrepreneurs.” –Vishal Mahadevia

Tandon offered several examples. In October 2010, government restrictions crippled the microfinance industry and all but shut it down. Back then, microfinance had become controversial when several suicides in India’s Andhra Pradesh state were attributed to the difficulties borrowers faced in repaying high-interest loans.

The Andhra Pradesh government, egged on by local politicians, introduced a series of constraints, “basically telling everyone not to pay back their loans,” Tandon recalled. “[Until then], the microfinance business was on fire; it was the fastest growing in our portfolio. One day, all of a sudden, the Andhra Pradesh government came out with rules on microfinance that completely made the whole space untenable. It was the fastest mark-down we have seen.”

Six years later, another government move hurt especially small and midsized businesses with cascading effects across the economy, Tandon said. He referred to India’s demonetization of high-value currency notes in late 2016 that effectively put 86% of the currency out of circulation, severely hampering the cash economy with extensive ripple effects that are felt to this day. “Again, the industry went through the same churn and the same challenges [as with the microfinance meltdown], and many firms had trouble coming back up to speed. That is the challenge you have to live with in India. You have to believe that stuff will happen every once in a while, and really make it very hard, and you just have to be prepared.”

In the wake of the demonetization exercise, a mortgage finance company that Partners Group had invested in found itself in dire straits when its borrowers were unable to make payments. The episode also found Partners Group thinking up some creative solutions to cope with the crisis. “Many of the people we lent to were self-employed and get their revenues in cash — shopkeepers and small contractors,” Tandon said. “Our guys stood in lines with our customers, making sure that they would deposit money in the bank, so that their payments could get cleared when their EMIs (equated monthly installments) were due. So that is the level of planning you have to do when these challenges present themselves, which is reasonably frequently in India.”

India’s PE industry has a long distance to go if one compares it with its U.S. counterpart, according to the panel participants. For example, transaction velocity is much higher in the U.S. than in India, said Dixit. “[Private equity] transactions in the U.S. start and finish in 90 days, and the entire ecosystem is built around it,” he added. “There’s so much precedence that you don’t have to negotiate from first principles. It’s still not the case in India, where a lot of stuff is negotiated from first principles, and transactions take very long for a variety of issues.”

“Whether it is currency demonetization or retrospective tax laws, those will be bumps along the journey, but that’s what makes it more exciting, and more fun for new entrants.” –Shweta Jalan

A lower degree of competition intensity is the second area where the Indian PE market is different from the U.S. market, said Dixit. Although it has improved in many ways, the PE industry in the country “is still not as productive a market [as in the U.S.] in terms of the people you deploy and the results they deliver in a given time frame.” For example, PE activity in the health care space is intense in the U.S., with some 20 firms actively investing in each of its different categories, such as health care services, pharmaceuticals, medical technology or biotechnology, and getting more granular within those sub-categories, he explained.

The source of PE capital is the third area where the Indian PE markets are different from those in, say other emerging markets like China. Nearly half the PE capital deployed in China is renminbi-denominated, but in India’s case, more than 95% of such funds are dollar-denominated, and are sourced from overseas investors, said Dixit. “The rupee capital is less than 5% of the market.”

Finding Returns Beyond the Challenges

On the positive side, the exciting aspect of doing PE deals in India is that they offer “the opportunity to grow and scale companies, taking advantage of extremely talented, world-class entrepreneurs,” said Mahadevia. He acknowledged that transaction velocity and structural deficiencies tug at the development of India’s PE industry, but he offered a piece of advice to cope with them. “One of the big differences [in India] is you need to have patience,” he said. “Everything does go wrong twice. You have to be patient through multiple cycles, as you build these companies. Over the next decade or two, private equity is going to be a fantastic asset class — for investors, for professionals, and more importantly for the folks that make us all smart, the entrepreneurs. So, I’m quite optimistic.”

Jalan agreed that PE investors who brace themselves for those hairpin bends in India’s regulatory system or other humps will do better than others. “Don’t expect it to be a smooth journey,” she said, “There will be lots of ups and downs.” She noted that her company faces similar obstacles with its fund in Latin America, another evolving PE market. “Whether it is currency demonetization or retrospective tax laws, those will be bumps along the journey, but that’s what makes it more exciting, and more fun for new entrants,” she told students and other audience members who may be considering a career in private equity in India. “In some ways, you will be building the industry from where it is to hopefully what would be a mature industry in 15 to 20 years.”

Tandon pointed to the ability to help create employment as another fulfilling aspect of doing PE deals in India. “A lot of private equity in India is about creating jobs and growing business,” he said. “They are not about [boosting] profitability by cutting costs; there is real growth. When you see businesses triple the number of employees over five or six years, it’s very gratifying, because there are very few careers that enable you to do that, and to see that from such a close distance.”

Another satisfying aspect for PE investors in India is when they leave their target firms in better shape than they were in before they made their investments. “Most businesses that we invest in don’t have the systems, the processes and the professional management necessary for growth,” Tandon said. “Just the ability to leave businesses five or six years later in much better shape, with systems, processes, and high-quality professional management teams, and say ‘I made a real difference to the way the business is run’ is gratifying, too.”

More From Knowledge at Wharton

How Financial Literacy Affects Household Debt and Bankruptcy | Sasha Indarte

How Stock Price Volatility in Closely Held Firms Distorts Capital Allocation

What Are Some of the Keys to Responsible Investing?

Looking for more insights.

Sign up to stay informed about our latest article releases.

Impact investing finds its place in India

Rising demand for socially responsible and purpose-driven finance has resulted in new ways of putting capital to work the world over. In the past decade, what is now known as “impact investing” has challenged the long-held view that social returns should be funded by philanthropy and financial returns should be funded by mainstream investors.

Stay current on your favorite topics

The global market for impact investments is projected to grow to $300 billion or more by 2020, 1 1. David Bank, “Steering impact investing toward a 2020 tipping point”, Impact Alpha, July 6 2017, news.impactalpha.com. according to the Global Steering Group on Impact Investment. Although this is still a fraction of the total private-equity assets under management (about $2.5 trillion in 2016 2 2. 2017 Preqin global private equity and venture capital report , Preqin, 2017, preqin.com. ), mainstream investors have entered the arena and are bringing scale to what was earlier considered a niche. And the dialogue is shifting rapidly from impact investing to “investing for impact.”

India is fast becoming a test bed for many of these activities. Between 2010 and 2016, India attracted over 50 active impact investors, who poured in more than $5.2 billion. About $1.1 billion was invested in 2016 alone. This article, based on our new report, Impact investing: Purpose-driven finance finds its place in India , looks at recent developments in the country and debunks some myths that have long surrounded these investments.

At the frontiers of impact: The India story

Impact investing can be a vehicle to fund, catalyze, and scale approaches that improve millions of lives. India is emerging as an attractive market for this type of investing. High demand for investments is likely to continue as a result of the growing population, underlying economic growth , stable financial markets with a strong rule of law, and large unmet social needs.

Cumulative investment in impact investments in India since 2010 has been $5.2 billion. In many ways, 2015 was a turning point, as investments crossed $1 billion (Exhibit 1). Much of the growth has come from a doubling or more of average deal size, which rose to $17.6 million in 2016, from $7.6 million in 2010. The volume of deals has remained stable, at about 60 to 80 a year, demonstrating the emphasis on scaling new models of impact.

We observe four trends shaping impact funding in India:

Diversified and complementary sources of capital

Total investments have grown as a wider set of investors began to participate. Impact investors and conventional private-equity (PE) and venture-capital (VC) firms bring critical and complementary skills to the table. While impact investors funded 65 percent of total deals by volume (including coinvestment deals with traditional PE funds), these deals account for 52 percent of investments by value. Over the years, as business models in sectors such as financial inclusion and clean energy have scaled, investor confidence has grown and impact investors have started participating in larger deals along with traditional PE investors, resulting in more investment from club deals. 3 3. Refers to deals where impact investors and conventional PE/VC investors participate together.

Bigger ticket sizes

Data for the past three years show a spurt in deal size. Investments in clean energy dipped in 2012–13 as projects were deferred after a delay in implementing tax incentives for green energy companies; the industry regained momentum after new policies were implemented. 4 4. CRISIL Insight: Wind-energy sector to see Rs.650 billion investments in 3 years , CRISIL January 2015, crisil.com. Our analysis also shows three drivers of growth in average investment size. First, business models of several companies in healthcare, microfinance, and skills training have matured in recent years. This has increased their ability to absorb larger investments. Second, demonstrated profitable exits in the social sector are providing more liquidity to enterprises and improving their ability to raise capital. Third, impact investors who de-risk business models and build capabilities are beginning to collaborate with growth PE investors that specialize in scaling and capital efficiency, and this is supporting impact enterprises’ financing across their life cycle.

Would you like to learn more about our Private Equity & Principal Investors Practice ?

More diverse sector spread.

At the start of this decade, investments in clean energy (wind, solar, and small hydropower generation) dominated impact investing in India. This changed sharply in 2013 as fund flows into clean energy slowed. Large investments in scale institutions in financial inclusion have offset some of this decline. Overall, the sector mix has changed. Clean energy amounted to roughly 40 percent of the deal value in 2014–16, declining from 60 percent in 2011–13, because of an increase in both the volume and value contribution from microfinance as the sector matured.

In terms of volume growth, too, there is increasing diversification. Investments in sectors such as education, healthcare, and agriculture have all grown during this period. Financial inclusion and clean energy accounted for 64 percent of the deals in 2016, compared with 88 percent of the total in 2010. This shows investors are finding investable business models and enterprises in sectors that were previously considered unattractive from a scale or returns perspective.

Alignment of investment objectives

General partners (GPs) continue to hold themselves to a high standard on the type of investments they make and the stages at which they invest. Even as GPs see the capabilities and business models of social enterprises mature, especially in sectors like financial inclusion, they largely remain focused on earlier-stage investments. Limited partners (LPs) appear less constrained by the stage of investment or measurement metrics. Overall, as the industry matures and more exits and returns are realized, LPs and GPs appear more aligned on investment criteria than ever. For example, there is greater convergence on criteria necessary for social investment, adding to LPs’ confidence.

Dispelling myths about investing for impact

Impact investing still has a long way to go as investors continue to struggle with preconceived notions and biases. Our analysis has led to a few counterintuitive insights.

Myth 1: Impact investing means lower returns

Impact investments in India have demonstrated an ability to employ capital sustainably and to meet the financial expectations of investors. An assessment of 48 exits between 2010 and 2015 shows that the investments produced a median internal rate of return (IRR) of about 10 percent (Exhibit 2). And 58 percent of the deals either met or exceeded the average expected market rate of about 7 percent. It may come as a surprise that the top one-third of deals yielded a median IRR of 34 percent, clearly indicating that it is possible to achieve profitable exits in social enterprises.

A sectoral analysis shows that financial inclusion stands out for profitable exits. Nearly 80 percent of the exits in financial inclusion were in the top two-thirds of IRR performance. Half the deals in clean energy and agriculture generated a similar financial performance, while those in healthcare and education have yet to catch up. With a limited sample set of only 17 exits outside financial inclusion, it is too early to evaluate the performance of the remaining sectors.

The correlation between size, volatility, and performance is evident (Exhibit 3), allowing investors to select the opportunities best suited to their skills and investment strategy. That volatility of returns decreases with increase in deal sizes is not to be taken for granted either. It’s an important outcome, an indicator that investors have expertise in seeding, growing, and scaling social enterprises and that they are able manage risk effectively.

Myth 2: Patient capital is a necessary prerequisite

Our analysis shows holding periods at exit have been about five years in both average and median terms. This is shorter than the approximately ten years that a typical investor with “patient” capital would expect. Deals yielded a wide range of IRR no matter the holding period. Viewed another way, this also implies that social enterprises with strong business models do not need long holding periods to generate value for shareholders.

Myth 3: Investing for impact is for impact investors only

Social investment calls for a wide set of investors if it aspires to maximize social welfare. Impact investors and conventional PE or VC funds play complementary roles. While both types of funds are active, impact investors usually back a greater number of smaller deals relative to PE and VC funds. Complementary skills by different players are useful at different stages of evolution of investee companies:

- Stage one needs early-stage investors with expertise in developing and establishing a viable business model, basic operations, and capital discipline.

- Stage two calls for skills in balancing economic returns with social impact, and the stamina to commit to and measure the dual bottom line.

- Stage three requires expertise in scaling up, refining processes, developing talent, and systematic expansion.

Impact investors are playing a big role in stimulating the growth of social enterprises. Impact funds were the first investors in 62 percent of all deals and in eight of the top ten microfinance institutions in India. This led to traction from conventional PE and VC funds, even as business models of underlying industries matured.

Conventional PE and VC funds too played a material role as they brought larger pools of capital, which accounted for about 70 percent of initial institutional funding by value. This is particularly important for capital-intensive and asset-heavy sectors like clean energy and microfinance. Overall, 48 percent of the capital in the industry was infused in deals by mainstream funds.

As club deals become more prevalent, they highlight the complementary role of both kinds of investor. Such deals are increasing: 32 percent of deals by value and 13 percent of deals by volume were done in partnership (Exhibit 4). As enterprises mature and impact investors remain involved, they are able to pull in funding from mainstream funds.

Equally important is the complementary role nonprofit organizations play in providing capacity with highly effective boots-on-the-ground capabilities. Nonprofits have typically been on the ground for longer periods and have developed cost-effective mechanisms for delivery and implementation. Impact investors could be seen as strategic investors in nonprofits who in turn play roles in scaling up and attracting talent, and who can deliver financial and operating leverage in return.

Myth 4: Social enterprises backed by impact investors are small investments whose impact is a drop in the ocean

Impact investments generated a median gross IRR of 10 percent in dollar-adjusted terms. More significantly, they touched the lives of 60 million to 80 million people in India—about the size of the population of France. And as these social enterprises scale, so will their impact.

The road ahead for impact investing in India

With a combination of high social needs with robust market forces, impact investors in India can make a strong case for growth. We believe impact investments have the potential to grow 20 to 24 percent a year between now and 2025, reaching $6 billion to $8 billion in deployment.

How impact investing can reach the mainstream

However, to fulfill this potential, the impact-investment industry and enabling ecosystem need to take a number of steps. Several topics could be addressed:

Pursue transparency measures. The industry should identify clear and well-defined metrics for measurement. For example, it could standardize dual-performance metrics relevant to India at a sector level with local and global industry bodies. It could also collaborate with credible third parties such as credit-rating agencies and chartered accountants to measure, audit, and report impact.

Expand funding. Unlocking additional sources of strategic capital is essential. To do so, the industry could work with the Indian government to leverage corporate-social-responsibility (CSR) funds for approved uses in the impact-investing ecosystem. In addition, the industry could work with the government to create a “bottom of pyramid” fund of funds. Furthermore, the industry could create an outcomes fund backed by philanthropists, which would enable funding not just for social enterprises but also to multiple partnering nonprofits. Other approaches include exploring retail investing participation or guiding social enterprises on ways to strengthen credit scores.

Explore market-backed innovations. The industry could explore a wider set of market mechanisms for investing. For example, it could broaden participation through instruments such as social- or development-impact bonds, with the support of specialized intermediaries. It could also provide incentive for dual goals through pay-for-performance schemes for investors and philanthropists, and create new platforms in the long run, such as a social stock exchange.

Develop governance and reporting. The industry could develop higher and more transparent standards for diligence and reporting. It could also apply standards of diligence, investment, and portfolio monitoring used in traditional investing.

Attract and develop talent. The industry should harness the attractiveness of the social-environmental impact proposition to promote greater professional participation in funds and portfolio companies. The way forward might include introducing professional certification programs with a social-investment focus; supporting social-sector CEOs with incubation, coaching, and board-advisory services; and revisiting compensation and performance incentives to help bridge the gap with comparable alternative investment funds.

Strengthen industry collaboration. Associations could work toward increasing awareness of the industry through forums and seminars, inviting regulators, social enterprises, CSR bodies, and conventional PE and VC investors. The industry could develop case studies for successful social enterprises beyond microfinance as well as explore more strategic coinvestment approaches to increase participation of other pools of capital that bring complementary skills.

Download the full report on which this article is based, Impact investing: Purpose-driven finance finds its place in India (PDF–1063 KB).

Vivek Pandit is a senior partner in McKinsey’s Mumbai office, and Toshan Tamhane is a senior partner in the Jakarta office.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

The changing landscape of social-impact investing

India’s ascent: Five opportunities for growth and transformation

Transforming last mile – connectivity in India through aviation

Strengthening India’s maritime sector: The role of GIFT IFSC

How India shops online

Generative AI in art: Exploring the intersection of technology and creativity

The India opportunity: Developing resilient electronics supply chains

Deals at a Glance

Unlocking opportunities in tax using GenAI

Mastering the art of long-term value creation

Transforming India’s mining landscape with autonomous technology

Value in motion

Building a better future of work

Loading Results

No Match Found

Deal origination and execution

Using our sector expertise and international reach, we help identify and assess potential acquisition and bolt-on targets. On the buy-side, we advise PE clients on their investment search, business planning and financial modelling, through to the approach, initial offer and bid tactics. Our deal professionals advise not just on the financial aspects of deals, including debt advisory , but across the wide range of operational and strategic activities.

Our integrated service includes financial, operational and commercial due diligence as well as sale and purchase agreement reviews and agreement support. Our specialist PE tax teams ensure that the deal is not only executed in a tax-efficient manner but also that the acquisition structure accommodates future plans for the business in terms of additional acquisitions.

Case studies

PwC has added value for the PE clients

Related content

Deals in india: annual review and outlook for 2021, deals in india - mid-year review and outlook for 2021, reflections: indian private equity in 2017, taking us-india economic relations to the next level, reflections: indian private equity in 2016, pe in india 2025: a 40-bn-usd decade beckons.

Bhavin Shah

Partner, Leader - Private Equity, PwC India

© 2018 - 2024 PwC. All rights reserved. PwC refers to the PwC network and/or one or more of its member firms, each of which is a separate legal entity. Please see www.pwc.com/structure for further details.

- Cookies info

- About Site Provider

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, venture capital and private equity in india: an analysis of investments and exits.

Journal of Indian Business Research

ISSN : 1755-4195

Article publication date: 22 March 2011

The venture capital and private equity (VCPE) industry in India has grown significantly in recent years. During five‐year period 2004‐2008, the industry growth rate in India was the fastest globally and it rose to occupy the number three slot worldwide in terms of quantum of investments. However, academic research on the Indian VCPE industry has been limited. This paper seeks to fill the gap in research on the recent trends in the Indian VCPE industry.

Design/methodology/approach

Studies on the VCPE transactions have traditionally focused on one of the components of the investment lifecycle, i.e. investments, monitoring, or exit. This study is based on analyzing the investment life cycle in its entirety, from the time of investment by the VCPE fund till the time of exit. The analysis was based on a total of 1,912 VCPE transactions involving 1,503 firms during the years 2004‐2008.

Most VCPE investments were in late stage financing and took place many years after the incorporation of the investee firm. The industry was also characterized by the short duration of the investments. The type of exit was well predicted by the type of industry, financing stage, region of investment, and type of VCPE fund.

Originality/value

This paper highlights some of the key areas to ensure sustainable growth of the industry. Early stage funding opportunities should be increased to ensure that there is a strong pipeline of investment opportunities for late stage investors. VCPE investments should be seen as long‐term investments and not as “quick flips”. To achieve this, it is important to have a strong domestic VCPE industry which can stay invested in the portfolio company for a longer term.

- Venture capital

- Equity capital

- Investments

Rajan Annamalai, T. and Deshmukh, A. (2011), "Venture capital and private equity in India: an analysis of investments and exits", Journal of Indian Business Research , Vol. 3 No. 1, pp. 6-21. https://doi.org/10.1108/17554191111112442

Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2011, Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Product details

Join 307,012+ Monthly Readers

Get Free and Instant Access To The Banker Blueprint : 57 Pages Of Career Boosting Advice Already Downloaded By 115,341+ Industry Peers.

- Break Into Investment Banking

- Write A Resume or Cover Letter

- Win Investment Banking Interviews

- Ace Your Investment Banking Interviews

- Win Investment Banking Internships

- Master Financial Modeling

- Get Into Private Equity

- Get A Job At A Hedge Fund

- Recent Posts

- Articles By Category

The Private Equity Case Study: The Ultimate Guide

If you're new here, please click here to get my FREE 57-page investment banking recruiting guide - plus, get weekly updates so that you can break into investment banking . Thanks for visiting!

The private equity case study is an especially intimidating part of the private equity recruitment process .

You’ll get a “case study” in virtually any private equity interview process , whether you’re interviewing at the mega-funds (Blackstone, KKR, Apollo, etc.), middle-market funds , or smaller, startup funds.

The difference is that each one gives you a different type of case study, which means you need to prepare differently:

What Should You Expect in a Private Equity Case Study?

There are three different types of “case studies”:

- Type #1: A “ paper LBO ,” calculated with pen-and-paper or in your head, in which you build a simple leveraged buyout model and use round numbers to guesstimate the IRR.

- Type #2: A 1-3-hour timed LBO modeling test , either on-site or via Zoom and email. This is a pure speed test , so proficiency in the key Excel shortcuts and practice with many modeling tests are essential.

- Type #3: A “take-home” LBO model and presentation, in which you might have a few days up to a week to pick a company, research it, build a model, and make a recommendation for or against an acquisition of the company.

We will focus on the “take-home” private equity case study here because the other types already have their own articles/tutorials or will have them soon.

If you’re interviewing within the fast-paced, on-cycle recruiting process with large funds in the U.S. , you should expect timed LBO modeling tests (type #2).

If the firm interviews dozens of candidates in a single weekend, there’s no time to give everyone open-ended case studies and assess them.

You might also get time-pressured LBO modeling tests in early rounds in other financial centers, such as London .

The open-ended case studies – type #3 – are more common at smaller funds, in off-cycle recruiting, and outside the U.S.

Although you have more time to complete them, they’re significantly more difficult because they require critical thinking skills and outside research.

One common misconception is that you “need” to build a complex model for these case studies.

But that is not true at all because they’re judging you mostly on your investment thesis , your presentation, and your ability to answer questions afterward.

No one cares if your LBO model has 200 rows, 500 rows, or 5,000 rows – they care about how well you make the case for or against the company.

This open-ended private equity case study is often the final step between the interview and the job offer, so it is critically important.

The Private Equity Case Study, in Parts

This is another technical tutorial, so I’ve embedded the corresponding YouTube video below:

Table of Contents:

- 4:32: Part 1: Typical Case Study Prompt

- 6:07: Part 2: Suggested Time Split for a 1-Week Case Study

- 8:01: Part 3: Screening and Selecting a Company

- 14:16: Part 4: Gathering Data and Doing Industry Research

- 22:51: Part 5: Building a Simple But Effective Model

- 26:32: Part 6: Drafting an Investment Recommendation

Files & Resources:

- Case Study Prompt (PDF)

- Private Equity Case Study Slides (PDF)

- Cars.com – Highlighted 10-K (PDF)

- Cars.com – Investor Presentation (PDF)

- Cars.com – Excel Model (XL)

- Cars.com – Investment Recommendation Presentation (PDF)

We’re going to use Cars.com in this example, which is one of the many case studies in our Advanced Financial Modeling course:

Advanced Financial Modeling

Learn more complex "on the job" investment banking models and complete private equity, hedge fund, and credit case studies to win buy-side job offers.

The full course includes a detailed, step-by-step walkthrough rather than this summary, an additional advanced LBO model, and other complex case studies for investment banking, hedge funds, and credit.

Part 1: Typical Private Equity Case Study Prompt

In some cases, they’ll give you a company to analyze, but in others, you’ll have to screen for companies yourself and pick one.

It’s easier if they give you the company and the supporting documents like the Information Memorandum , but you’ll also have less time to complete the case study.

The prompt here is very open-ended: “We like these types of deals and companies, so pick one and present it to us.”

The instructions are helpful in one way: they tell us explicitly not to build a full 3-statement model and to focus on the market and strategy rather than an “extremely complex model.”

They also hint very strongly that the model must include sensitivities and/or scenarios:

Part 2: Suggested Time Split for a 1-Week Private Equity Case Study

You have 7 days to complete this case study, which may seem like a lot of time.

But the problem is that you probably don’t have 8-12 hours per day to work on this.

You’re likely working or studying full-time, which means you might have 2-3 hours per day at most.

So, I would suggest the following schedule:

- Day #1: Read the document, understand the PE firm’s strategy, and pick a company to analyze.

- Days #2 – 3: Gather data on the company’s industry, its financial statements, its revenue/expense drivers, etc.

- Days #4 – 6: Build a simple LBO model (<= 300 rows), ideally using an existing template to save time.

- Day #7: Outline and draft your presentation, let the numbers drive your decisions, and support them with the qualitative factors.

If the presentation is shorter (e.g., 5 slides rather than 15) or longer, you could tweak this schedule as needed.

But regardless of the presentation length, you should spend MORE time on the research, data gathering, and presentation than on the LBO model itself.

Part 3: Screening and Selecting a Company

The criteria are simple and straightforward here: “The firm aims to find undervalued companies with stagnant or declining core businesses that can be acquired at reasonable valuation multiples and then turn them around via restructuring, divestitures, and add-on acquisitions.”

The industry could be consumer, media/telecom, or software, with an ideal Purchase Enterprise Value of $500 million to $1 billion (sometimes up to $2 billion).

Reading between the lines, I would add a few criteria:

- Consistent FCF Generation and 10-20%+ FCF Yields: Strategies such as turnarounds and add-on acquisitions all require cash flow. If the company doesn’t generate much Free Cash Flow , it will have to issue Debt to fund these strategies, which is risky because it makes the deal very dependent on the exit multiple.

- Relatively Lower EBITDA Multiples: If the company has a “stagnant or declining” core business, you don’t want to pay 20x EBITDA for it. An ideal range might be 5-10x, but 10-15x could be OK if there are good growth opportunities. The IRR math also gets tougher at high EBITDA multiples because the maximum Debt in most deals is 5-6x.

- Clean Financial Statements and Enough Detail for Revenue and Expense Projections: You don’t want companies with 2-page-long Cash Flow Statements or Balance Sheets with 100 line items; you can’t spare the time required to simplify and consolidate these statements. And you need some detail on the revenue and expenses because forecasting revenue as a simple percentage growth rate is a bad idea in this context.

We used this process to screen for companies here:

- Step 1: Do a high-level screen of companies in these 3 sectors based on industry, Equity Value or Enterprise Value, and geography.

- Step 2: Quickly review the list of ~200 companies to narrow the sector.

- Step 3: After picking a specific sector, narrow the choices to the top few companies and pick one of them.

In software , many of the companies traded at very high multiples (30x+ EBITDA), and others had negative EBITDA , so we dropped this sector.

In consumer/retail , the companies had more reasonable multiples (5-10x), but most also had low margins and weak FCF generation.

And in media/telecom , quite a few companies had lower multiples, but the FCF math was challenging because many companies had high CapEx requirements (at least on the telecom side).

We eliminated companies with very high multiples, negative EBITDA, and exorbitant CapEx, which left this set:

Within this set, we then eliminated companies with negative FCF, minimal information on revenue/expenses, somewhat-higher multiples, and those whose businesses were declining too much (e.g., 20-30% annual declines).

We settled on Cars.com because it had a 9.4x EBITDA multiple at the time of this screen, a declining business with modest projected growth, 25-30% margins, and reasonable FCF generation with FCF yields between 10% and 15%.

If you don’t have Capital IQ for this exercise, you’ll have to rely on FinViz and use P / E multiples as a proxy for EBITDA multiples.

You can click through to each company to view the P / FCF multiples, which you can flip around to get the FCF yields.

In this case, don’t even bother looking for revenue and expense information until you have your top 2-3 candidates.

Part 4: Gathering Data and Doing Industry Research

Once you have the company, you can spend the next few days skimming through its most recent annual report and investor presentation, focusing on its financial statements and revenue/expense drivers.

With Cars.com, it’s clear that the company’s “Dealer Customers” and Average Revenue per Dealer will be key drivers:

The company also has significant website traffic and earns advertising revenue from that, but it’s small next to the amount it earns from charging car dealers to use its services:

It’s clear from this quick review that we’ll need some outside research to estimate these drivers, as the company’s filings and investor presentation have little.

Fortunately, it’s easy to Google the number of new and used car dealers in the U.S. and estimate the market size and share like that:

The company’s market share has been declining , and we expect that trend to continue, but it’s not clear how rapid the decline will be.

Consumers are increasingly buying directly from other consumers, and dealers have less reason to use the company’s marketplace services than in past years.

We create an area for these key drivers, with scenarios for the most uncertain one:

You might be wondering why there’s no assumed uptick in market share since this is supposed to be a “turnaround” case study.

The short answer is that we think the company is unlikely to “turn around” its core business in this time frame, so it will have to move into new areas via bolt-on acquisitions .

For example, maybe it could acquire smaller firms that sell software and services to dealers, or it could acquire physical or online car dealerships directly.

Another option is to acquire companies that can better monetize Cars.com’s large and growing web traffic – such as companies that sell auto finance leads.

As part of this process, we also need to research smaller companies to acquire, but there isn’t much to say about this part.

It comes down to running searches on Capital IQ for smaller companies in related industries and entering keywords like “auto” in the business description field.

In terms of the other financial statement drivers , many expenses here are simple percentages of revenue, but we could also link them to the employee count.

We also link the website traffic to the sales & marketing spending to capture the spending required for growth in that area.

Finally, we need to input the financial statements for the company, which is not that hard since they’re already fairly clean:

It might be worth consolidating a few items here, but the Income Statement and partial Cash Flow Statement are mostly fine, which means the Excel versions are close to the ones in the annual report.

Part 5: Building a Simple But Effective Model

The case study instructions state that a full 3-statement model is not necessary – but even if they had not, such a model would rarely be worthwhile.

Remember that LBO models, just like DCF models , are based on cash flow and EBITDA multiples ; the full statements add almost nothing since you can track the Cash and Debt balances separately.

In terms of model complexity, a single-sheet LBO with 200-300 rows in Excel is fine for this exercise.

You’re not going to get “extra credit” for a super-complex LBO model that takes days to understand.

The key schedules here are:

- Transaction Assumptions – Including the purchase price, exit assumptions, scenarios, and tranches of debt. Skip the working capital adjustment unless they specifically ask for it. For more on these nuances, see our coverage of Enterprise Value vs. purchase price and cash-free debt-free deals .

- Sources & Uses – Short and simple but required to calculate the Investor Equity.

- Revenue, Expense, and Cash Flow Drivers – These don’t need to be super-complex; the goal is to go beyond projecting revenue as a simple percentage growth rate.

- Income Statement and Partial Cash Flow Statement – The goal is to calculate Free Cash Flow because that drives Debt repayment and Cash generation in an LBO.

- Add-On Acquisitions – These are part of the “turnaround strategy” in this deal, so they’re quite important.

- Debt Schedule – This one is quite simple here because the deal is not dependent on financial engineering.

- Returns Calculations – The IPO vs. M&A exit options add a bit of complexity.

- Sensitivity Tables – It’s difficult to draft the investment recommendation without these.

Skip anything that makes your life harder, such as circular references in Excel (to avoid these, use the beginning Cash and Debt balances to calculate interest).

We pay special attention to the add-on acquisitions here, with support for their revenue and EBITDA contributions:

The Debt Schedule features a Revolver, Term Loans, and Subordinated Notes:

The Returns Calculations are also simple; we do assume a bit of Multiple Expansion because of the company’s higher growth rate by the end:

Could we simplify this model even further?

I don’t think the M&A vs. IPO exit options mentioned above are necessary, and we could also drop the “Growth” vs. “Value” options for the add-on acquisitions:

Especially if we recommend against the deal, it’s not that important to analyze which type of add-on acquisition works best.

It would be more difficult to drop the scenarios and Excel sensitivity tables , but we could restructure them a bit and fold the scenario into a sensitivity table.

All investing is probabilistic, and there’s a huge range of potential outcomes – so it’s difficult to make a serious investment recommendation without examining several outcomes.

Even if we think this deal is spectacular, we must consider cases in which it goes poorly and how we might reduce those risks.

Part 6: Drafting an Investment Recommendation

For a 15-slide recommendation, I would recommend this structure:

- Slides 1 – 2: Recommendation for or against the deal, your criteria, and why you selected this company.

- Slides 3 – 7: Qualitative factors that support or refute the deal (market, competition, growth opportunities, etc.). You can also explain your proposed turnaround strategy, such as the add-on acquisitions, here.

- Slides 8 – 13: The numbers, including a summary of the LBO model, multiples vs. comps (not a detailed valuation), etc. Focus on the assumptions and the output from the sensitivity tables.

- Slide 14: Risk factors for a positive recommendation, and the counter-factual (“what would change your mind?”) for a negative one. You can also explain the potential impact of each risk on the returns and how you could mitigate these risks.

- Slide 15: Restate your conclusions from Slide 1 and present your best arguments here. You could also change the slide formatting or visuals to make it seem new.

“OK,” you say, “but how do you actually make an investment decision?”

The easiest method is to set criteria for the IRR or multiple of invested capital in each case and say, “Yes” if the deal achieves those numbers and “No” if it does not.

For example, maybe the targets are a 30% IRR in the Upside case, a 20% IRR in the Base case, and a 1.0x multiple in the Downside case (i.e., avoid losing money).

We do achieve those numbers in this deal, but the decision could go either way because the deal is highly dependent on the add-on acquisitions.

Without these acquisitions, the deal does not work; the IRR falls by 10%+ across all the scenarios and turns negative in the Downside case.

We need at least 5 good acquisition candidates matching very specific financial profiles ($100 million Purchase Enterprise Value and a 15x EBITDA purchase multiple with 10% revenue growth or 5x EBITDA with 3% growth).

The presentation includes some examples of potential matches:

While these examples are better than nothing, the case is not that strong because:

- Most of these companies are too big or too small to fit into the strategy proposed here of ~$100 million in annual acquisitions.

- The acquisition strategy is unclear ; acquiring and integrating dealerships (even online ones) would be very, very different from acquiring software/data/media companies.

- And since the auto software market is very niche, there’s probably not a long list of potential acquisition candidates beyond the few we found.

We end up saying, “Yes” in this recommendation, but you could easily reach the opposite conclusion because you believe the supporting data is weak.

In short: For a 1-week open-ended case study, this approach is fine, but this specific deal would probably not stand up to a more detailed on-the-job analysis.

The Private Equity Case Study: Final Thoughts

Similar to time-pressured LBO modeling tests, you can get better at the open-ended private equity case study by “putting in the reps.”

But each rep is more time-consuming, and if you have a demanding full-time job, it may be unrealistic to complete multiple practice case studies before the real thing.

Also, even with significant practice, you can’t necessarily reduce the time required to research an industry and specific companies within it.

So, it’s best to pick companies and industries you already know and have several Excel and PowerPoint templates ready to go.

If you’re targeting smaller funds that use off-cycle recruiting, the first part should be easy because you should be applying to funds that match your industry/deal/client background.