- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

Young-Onset Dementia—New Insights for an Underappreciated Problem

- 1 Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota

- Original Investigation Global Prevalence of Young-Onset Dementia Stevie Hendriks, MSc; Kirsten Peetoom, PhD; Christian Bakker, PhD; Wiesje M. van der Flier, PhD; Janne M. Papma, PhD; Raymond Koopmans, PhD; Frans R. J. Verhey, MD, PhD; Marjolein de Vugt, PhD; Sebastian Köhler, PhD; Young-Onset Dementia Epidemiology Study Group; Adrienne Withall, PhD; Juliette L. Parlevliet, MD, PhD; Özgül Uysal-Bozkir, PhD; Roger C. Gibson, PhD; Susanne M. Neita, PhD; Thomas Rune Nielsen, PhD; Lise C. Salem, PhD; Jenny Nyberg, PhD; Marcos Antonio Lopes, PhD; Jacqueline C. Dominguez, PhD; Ma Fe De Guzman, PhD; Alexander Egeberg, MD, PhD; Kylie Radford, PhD; Tony Broe, PhD; Mythily Subramaniam, PhD; Edimansyah Abdin, PhD; Amalia C. Bruni, PhD; Raffaele Di Lorenzo, PhD; Kate Smith, PhD; Leon Flicker, PhD; Merel O. Mol, MSc; Maria Basta, PhD; Doris Yu, PhD; Golden Masika, PhD; Maria S. Petersen, PhD; Luis Ruano, MD, PhD JAMA Neurology

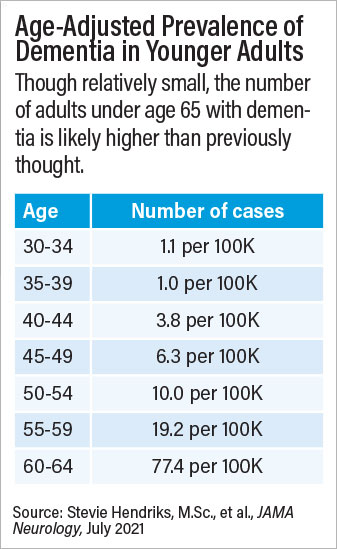

At one time in the not-too-distant past, young-onset dementia (YOD) was considered a disease, whereas later-onset dementia (LOD) was considered the inevitable consequence of aging. We now reject such a formulation, but within that misguided dichotomy is a recognition of the dramatic differences in prevalence and incidence of YOD compared with LOD. In this issue of JAMA Neurology , Hendriks et al 1 quantitate dementia prevalence in persons aged 30 to 64 years through a meta-analysis of 74 individual studies.

Read More About

Knopman DS. Young-Onset Dementia—New Insights for an Underappreciated Problem. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(9):1055–1056. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.1760

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Neurology in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Young-Onset Dementia More Prevalent Than Previously Estimated

- Nick Zagorski

Search for more papers by this author

A meta-analysis of 95 studies from around the world suggests that nearly 4 million adults globally may experience dementia before age 65.

Though considered a disease of the elderly, dementia can strike younger adults as well (Alois Alzheimer’s first patient was a woman who began experiencing memory loss and delusions in her 40s). Yet attention to patients with rare young-onset dementia—typically characterized as dementia before age 65—often pales in comparison to that given to the estimated 45 million adults living with late-onset dementia.

A large meta-analysis conducted by Sebastian Köhler, Ph.D., an associate professor of psychiatry and neuropsychology at Maastricht University in the Netherlands, and colleagues suggests young-onset dementia may be more common than previously estimated. Making use of data from 95 individual studies encompassing 2.7 million adults in more than 30 countries, the researchers calculated a global prevalence rate of 119.0 cases of young-onset dementia per 100,000 people. This figure is more than double that of previous estimates and equates to about 200,000 cases of young-onset dementia in the United States and nearly 4 million globally.

“Although this is higher than previously thought, it is probably an underestimation owing to lack of high-quality data,” senior author Köhler and colleagues wrote in JAMA Neurology . They noted that data on adults under age 50 were sparse, as were data from low- and middle- income countries.

The authors also excluded studies that focused on at-risk population groups like patients with HIV, noted Brian Draper, M.D., a conjoint professor of psychiatry at the University of New South Wales in Australia, who specializes in young-onset dementia. “The bulk of dementia research is related to diseases like Alzheimer’s or frontotemporal dementia, but these secondary dementias that arise from other disorders that can impact the brain should not be discounted,” he said. Draper has done a lot of work with alcohol-related dementia, which overlaps with Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, a condition in which chronic alcohol use leads to vitamin B deficiency and subsequent neurodegeneration.

Draper told Psychiatric News that the reduced attention to secondary dementias is not entirely from scientists or physicians. “There has been pushback from patients and advocacy groups for conditions like HIV to avoid associating these disorders with dementia due to stigma,” he said. As a result, he said, places like alcohol treatment centers do not often provide dementia screening, which contributes to patients slipping through the cracks.

“From a personal management and clinical care perspective, it’s imperative to diagnose young-onset dementia as soon as possible,” Draper continued. “By and large, people who develop dementia earlier in life have a faster rate of cognitive decline, yet they live longer with the disease”—a factor that may be due to younger patients having fewer comorbidities at the time of dementia diagnosis.

In an editorial that accompanied Köhler’s JAMA Neurology article, David Knopman, M.D., a professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, wrote: “Young-onset dementia is a particularly disheartening diagnosis because it affects individuals in their prime years, in the midst of their careers, and while raising families,” he wrote. “Most dementia care is geared for older patients, and as a consequence, services are rarely available to address the needs of someone diagnosed with dementia in their 50s who has dependent children at home and a spouse who must continue working. Understanding the prevalence and incidence of [young-onset dementia] is a first step in addressing this challenge.”

In comments to Psychiatric News , Knopman said that the results of the meta-analysis offered an important perspective on the rates of dementia over time and the relative risks in older versus younger adults. Overall, the study suggests that about 3% of all dementia cases in the United States are in adults under age 65. However, most of these cases were in adults aged 55 to 64.

“Among the really young, where the burden would be greatest, dementia is exceedingly rare,” Knopman said. In the age range of 30 to 34, for example, Köhler’s meta-analysis calculated a prevalence of 1 case of dementia per 100,000 people. “At that level, routine screening is out of the question,” he said. “So, on a practical level, how can physicians identify a problem they might encounter once a decade?”

It’s a pertinent question for psychiatrists, Draper said, since work by him and others has shown that chronic, treatment-resistant depression can be an early symptom of young-onset dementia. “If you have a middle-aged patient with treatment-resistant depression who begins complaining of memory problems, you should entertain [underlying] dementia as a possibility,” he said.

Draper noted that Alzheimer’s disease—which is the most common cause of dementia in older adults—is less dominant in young-onset cases. More commonly, younger patients may experience Disorders like frontotemporal dementia and Huntington’s disease are more common. This is why psychiatrists need to look at more than just cognition in younger people, as behavioral (personality changes) and/or physical symptoms (such as gait disturbances) are most likely to emerge first, he said.

“There is no specific pattern that can help diagnose patients at an individual level,” Knopman said. “But if physicians keep an open mind that dementia exists before 65, that can help awareness.”

Firsthand clinical experience is also valuable, Knopman continued. “Once you have seen one patient with dementia, it helps make future diagnoses much easier. If more clinicians could do a geriatric rotation, that would help diagnosis tremendously.”

The meta-analysis was supported by the Gieskes-Strijbis Foundation, Alzheimer Netherlands, and the Dutch Young-Onset Dementia Knowledge Centre. ■

“Global Prevalence of Young-Onset Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis” is posted here .

- Open access

- Published: 02 January 2022

What do health professionals need to know about young onset dementia? An international Delphi consensus study

- Leah Couzner 1 ,

- Sally Day 1 ,

- Brian Draper 2 ,

- Adrienne Withall 3 ,

- Kate E. Laver 4 ,

- Claire Eccleston 5 ,

- Kate-Ellen Elliott 5 ,

- Fran McInerney 5 &

- Monica Cations 1 , 4

BMC Health Services Research volume 22 , Article number: 14 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

3128 Accesses

7 Citations

7 Altmetric

Metrics details

People with young onset dementia (YOD) have unique needs and experiences, requiring care and support that is timely, appropriate and accessible. This relies on health professionals possessing sufficient knowledge about YOD. This study aims to establish a consensus among YOD experts about the information that is essential for health professionals to know about YOD.

An international Delphi study was conducted using an online survey platform with a panel of experts ( n = 19) on YOD. In round 1 the panel individually responded to open-ended questions about key facts that are essential for health professionals to understand about YOD. In rounds 2 and 3, the panel individually rated the collated responses in terms of their importance in addition to selected items from the Dementia Knowledge Assessment Scale. The consensus level reached for each statement was calculated using the median, interquartile range and percentage of panel members who rated the statement at the highest level of importance.

The panel of experts were mostly current or retired clinicians (57%, n = 16). Their roles included neurologist, psychiatrist and neuropsychiatrist, psychologist, neuropsychologist and geropsychologist, physician, social worker and nurse practitioner. The remaining respondents had backgrounds in academia, advocacy, or other areas such as law, administration, homecare or were unemployed. The panel reached a high to very high consensus on 42 (72%) statements that they considered to be important for health professionals to know when providing care and services to people with YOD and their support persons. Importantly the panel agreed that health professionals should be aware that people with YOD require age-appropriate care programs and accommodation options that take a whole-family approach. In terms of identifying YOD, the panel agreed that it was important for health professionals to know that YOD is aetiologically diverse, distinct from a mental illness, and has a combination of genetic and non-genetic contributing factors. The panel highlighted the importance of health professionals understanding the need for specialised, multidisciplinary services both in terms of diagnosing YOD and in providing ongoing support. The panel also agreed that health professionals be aware of the importance of psychosocial support and non-pharmacological interventions to manage neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Conclusions

The expert panel identified information that they deem essential for health professionals to know about YOD. There was agreement across all thematic categories, indicating the importance of broad professional knowledge related to YOD identification, diagnosis, treatment, and ongoing care. The findings of this study are not only applicable to the delivery of support and care services for people with YOD and their support persons, but also to inform the design of educational resources for health professionals who are not experts in YOD.

Peer Review reports

Young onset dementia (YOD), in which dementia symptoms develop prior to 65 years of age, accounts for up to 8% of all dementia diagnoses [ 1 ]. Young onset dementia is associated with significant challenges for both the individual and their support persons, which may differ to those experienced in late onset dementia (LOD) [ 2 ]. At the time of diagnosis people with YOD are often employed, and they and their supporters may be forced to leave the workforce. This presents financial ramifications [ 2 , 3 ]. They may be balancing caring responsibilities for young children and/or ageing parents and experience a shift in identity from that of a provider to a recipient of support [ 2 , 4 ]. People with YOD are also often physically healthy and active yet may experience a loss of empowerment and independence as their symptoms progress [ 4 ]. Other psychological impacts include shock or embarrassment about being diagnosed with a condition commonly associated with older adults, loss of purpose, and relationship strain [ 4 , 5 , 6 ]. Supporters of people with YOD report greater difficulty managing dementia-related behavioural disturbances than those providing support for someone with LOD [ 7 ]. Other effects reported by support persons include stress, depression, frustration, grief, guilt, loneliness, fear of the future, and social isolation [ 6 , 8 ].

People with YOD have unique needs and experiences, and as such require care to be provided by health professionals with sufficient knowledge and skills. A lack of awareness among health professionals about YOD may contribute to the average 4.7 year diagnosis delay from the onset of symptoms, with misdiagnosis being one reason [ 9 , 10 ]. However recent work by O’Malley et al. has identified, using expert consensus, key elements in the diagnostic workup of YOD to aide decision making for clinicians [ 11 ]. After diagnosis, the use of formal support services in the community may delay the need for permanent residential care and can provide respite and access to peer support [ 3 ]. However, services providing dementia-related support are often designed for older adults. These services are known to lack acceptability for people diagnosed with YOD. Reasons for this include a lack of age-appropriate services, poor service accessibility (e.g. lack of transport, held during work time, lack of child care), inadequate security for physically agile participants, affordability issues, a lack of continuity of care and inadequate information provision about YOD and the support available [ 3 , 12 , 13 ].

It is therefore important that health professionals possess adequate knowledge and skills about YOD presentation, identification, diagnosis, treatment, and care to provide services and information that are timely, appropriate, and accessible. A preliminary step to addressing this is to determine the information that health professionals require to provide this care. This study aims to establish a consensus among those with YOD expertise about the key information that is important for health professionals to know and understand about YOD. This data can then be utilised to inform the upskilling of YOD professionals and in the development of tools to track their knowledge.

The Delphi technique is a multistage method used to obtain a consensus among a panel of experts on a particular topic [ 14 ]. The process involves the iterative distribution of a series of questionnaires asking the participant to rank a list of items or statements in order of importance. When completing the second and subsequent questionnaires, participants are provided with the results of the previous questionnaire and are encouraged to reconsider their individual responses. The process continues until a consensus has been reached, or no further changes are being made [ 15 , 16 ]. The number of iterations or “rounds” varies, but three rounds can offer a balance between rigour and participant burden [ 15 ]. The questionnaires are completed anonymously and via mail or email, minimising the risk of individual participants influencing the rest of the group [ 17 ].

In this Delphi study, three feedback rounds were conducted using an online secure survey platform. The three phases in this study were: (a) identifying key information about young onset dementia, (b) rating agreed knowledge statements, and (c) confirming group consensus via item ratings. The procedure for this study was modelled on a previous study conducted by members of our research team that identified consensus opinion about key information about dementia more generally [ 18 ].

Participants

Participants selected for a Delphi study directly influence the quality of the data generated [ 15 , 19 ]. It is vital that participants possess in-depth knowledge or experience about the topic being explored. The ideal panel size has not been established, but 10 to 30 participants is recommended in the literature [ 19 , 20 ]. In this study, experts on young onset dementia were identified through networks of the research team in the areas of clinical care, psychology, research and education, advocacy and lived experience. Participants were required to have either lived experience or professional experience regarding YOD, be able to read and write in English and provide informed consent. These experts were invited to participate via an email invitation from the study team. Passive snowballing recruitment was also used meaning the experts were encouraged to forward the email invitation to others they considered experts in the area of young onset dementia who would be willing to participate in the study. The research was reviewed and approved by the Flinders University Social and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee (8331).

Experts were contacted via email from the study team throughout the project, and two follow up emails were sent for the second and third rounds. If the experts did not respond or participate in that round they were considered to have withdrawn from the study. All study participants were anonymous to each other and were identifiable to the study team only through their email address (to enable contact of participating experts at each round of the Delphi). Data collection was undertaken using an online survey platform, Qualtrics.

Round one (June 2020): gathering information

In the first round, the panel of experts were presented with the following open-ended questions:

What key facts are essential to understanding young onset dementia? Participants were provided with five concept areas to consider: (a) causes and characteristics, (b) symptoms and progression, (c) assessment and diagnosis, (d) prevention and treatment, and (e) care.

What key facts about young onset dementia are different to late onset dementia and the same as late onset dementia?

What key facts about young onset dementia are frequently misunderstood by health professionals?

These questions were modelled on those used in the development of the Dementia Knowledge Assessment Scale (DKAS) and in consultation with the research team. The questions were selected to identify information that the experts considered important for health professionals with differing levels of knowledge and experience in YOD to understand. The responses were then independently reviewed by two researchers on the project team who collated them to produce a list of statements that reflected the range of information provided. Where possible, the experts’ own words were used to maintain authenticity and reduce researcher bias. This process resulted in a list of 48 statements representing the information that the experts deemed to be essential in understanding YOD. Statements from the Dementia Knowledge Assessment Scale [ 18 ] were also included to build on existing work.

Round two (August 2020): rating knowledge statements

In the second round, the statements identified in round 1 were presented to the panel of experts. They were asked to rate each statement in terms of how essential it was for knowledge of YOD among health professionals from 1 (not important at all) to 5 (very important), or N/A, indicating that they perceived that the statement was not applicable to YOD. This rating scale was selected in accordance with that used in the development of the Dementia Knowledge Assessment Scale [ 21 ]. The responses were then analysed by two researchers on the project team to calculate the level of consensus achieved for each statement.

Round three (November 2020): obtaining consensus

In round 3, participants were presented with the same list of statements, accompanied by each statement’s median rating (group score) and consensus level from the previous round. Participants were not informed which statements had been deemed not applicable as this was collected for analytical purposes only. Participants were asked to review this new information, and again rate each statement on the same scale of 1 to 5. The responses were then analysed to ascertain the level of consensus reached by the participants for each statement. This allowed for comparisons to be made between the results of rounds 2 and 3, where little change would indicate a stability of the consensus levels.

Measurement and analysis

When using the Delphi technique, consensus is typically considered to have been reached when a certain percentage of the responses fall within a pre-determined range, for example 70% of participants rating 3 or higher on a four-point Likert scale [ 15 ]. The statistics commonly used in Delphi studies are measures of central tendency (mean, median and mode) and dispersion (standard deviation and interquartile range (IQR)). This allows for the combined group response to be presented, reflecting the responses of every panel member [ 15 , 22 ].

This study utilised the scoring systems reported by Annear and colleagues and van der Steen and colleagues [ 21 , 23 ] to build on existing work and allow for comparisons between the YOD information identified as essential in this study and that identified as essential to dementia more broadly in previous work. The scoring system is based on the median score and IQR for each statement, and the percentage of participants who scored the statement as either important or very important (the two highest levels). Full consensus was defined as a median score of 5, an IQR of 0, and 100% of participants rating the statement with the highest possible score of 5. Very high consensus was considered to be a median score of 5, an IQR of 0 and ≥ 80% scoring a 4 or 5. High consensus was defined as a median score of 5, an IQR ≤1 and ≥ 80% scoring a 4 or 5. Moderate consensus was considered to be a median score of 4–5, an IQR ≤2 and ≥ 60% scoring a 4 or 5. No consensus (low agreement) was defined as a median score of 4–5 and either IQR ≤2 or ≥ 60% scoring a 4 or 5. Statements with median scores between 2 and 4 were deemed to demonstrate no consensus (no agreement) [ 21 , 23 ].

Forty-six experts on YOD were identified via professional networks and invited to participate in the Delphi study. Of those, twenty-eight individuals completed the first round (61% response rate). Sixteen of the twenty-eight participants remained in the study until completion (57% completion rate), with one additional participant completing round 3 only. Most round 1 participants were from Australia ( n = 15, 54%), followed by Canada, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Norway. Fifty-seven percent ( n = 16) of respondents in round 1 identified themselves as being a current or retired clinician, or having dual clinical and academic roles. The clinical roles included neurologist, psychiatrist and neuropsychiatrist, psychologist, neuropsychologist and geropsychologist, physician, social worker and nurse practitioner. The remaining respondents had backgrounds in academia, advocacy, or other areas such as law, administration, homecare or were unemployed. The characteristics of the participants are summarised in Table 1 .

Round 1: gathering information

Twenty-eight participants responded to the open-ended questions presented in round 1. Their responses were independently reviewed by two researchers and collated into a list of 48 statements summarising the information provided (Table 2 ). These statements were then compared to those in theDKAS [ 18 ]. The DKAS was selected as it is a validated assessment of dementia knowledge based upon dementia information identified as essential using expert consensus, although not YOD-specific. Ten DKAS statements were identified as not corresponding to any of the statements based on the participant responses in this study. To utilise and build on the existing knowledge, 10 statements closely based on statements from the DKAS were added to the original 48 statements. The statements were grouped into six categories: characteristics, causes and prevention, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, and care.

Round 2: rating knowledge statements

In round 2, the participants were provided with the 58 statements developed in round 1 and asked to rate the importance of each statement on a scale from 1 (not important at all) to 5 (very important), or alternatively identify the statement as being not applicable to YOD. Nineteen participants provided responses in round 2. No statements achieved full consensus, however 16 statements (28%) achieved very high consensus. Very high consensus items most commonly related to post-diagnosis care for people with YOD ( n = 6, 38%).

Round 3: obtaining consensus

In round 3, participants were asked to rate the same statements for a second time. They were also provided with the median rankings and consensus levels from round two. Seventeen participants completed round 3 of the study, with consensus ratings displayed in Table 3 . As with round 2, no statements achieved full consensus, however all statements met some level of agreement. In total, 28% ( n = 16) of statements achieved very high consensus, 46% ( n = 26) reached high consensus, and 24% ( n = 14) reached moderate consensus. Three percent ( n = 2) of statements failed to achieve a consensus, reaching only low levels of agreement.

The statement that “young people with dementia require age-appropriate care programs and accommodation options” ranked highest, with 94% of participants rating the statement with the highest possible score of 5. At least one statement from each thematic category met very high consensus, except for “causes and prevention”. Of the statements that achieved very high consensus, the most prevalent themes were treatment ( n = 5, 31%) and care ( n = 5, 31%). Nineteen percent ( n = 3) related to the diagnosis of YOD, 13% ( n = 2) focused on the characteristics of YOD and 6% ( n = 1) referred to the symptoms of YOD.

Eight statements were identified by participants as not being applicable to YOD, most commonly “there are medications that can slow down the progression of some types of young onset dementia” ( n = 4). Two participants considered the statement “neuropsychiatric (i.e., behavioural and psychological) symptoms are more common in young people with dementia than older people” not relevant to YOD.

The additional 10 statements that were included from the DKAS [ 18 ] all reached consensus, with 10% (n = 1) reaching very high consensus, 40% (n = 4) reaching high consensus and 50% ( n = 5) reaching moderate consensus. Although these statements were not identified spontaneously by the experts, they were nonetheless deemed as important information for health professionals to know about YOD.

The panel of experts in this study reached high to very high consensus on 42 statements (out of 58) that they considered to be important for health professionals to know when providing care and services to people with YOD and their families. There was agreement across all thematic categories, indicating the importance of broad professional knowledge related to YOD identification, diagnosis, treatment, and ongoing care. These data can be used to inform efforts to upskill YOD professionals and track their knowledge and skills over time.

Identification and aetiology

Young onset dementia is an umbrella term that refers to a broad and heterogeneous range of illnesses, and in many cases occurs secondarily to another condition (for example, Huntington’s disease or alcohol use disorders) [ 24 ]. Common symptoms are not limited to cognitive impairment; depression, language impairments, and changes in behaviour or personality are regularly reported particularly by those with frontotemporal dementias [ 25 ]. Physical symptoms can include seizures, peripheral neuropathy, visual impairments, ataxia, skin lesions, headaches and visual impairment [ 26 ]. It is important for health professionals to be aware of the symptoms and stages of YOD as the range of clinical presentations and overlap of symptoms across YOD subtypes can delay the receipt of a diagnosis and often result in a dismissal of symptoms, or misdiagnosis [ 4 , 27 ].

The diversity in presentation, cause, and course of YOD was evident in many of the consensus statements, including that YOD is aetiologically diverse, refers to the emergence of dementia symptoms prior to the age of 65, is distinct from a mental illness, and is not a normal part of the ageing process. Consensus was also reached for facts that are commonly mistaken about YOD, including that most cases of YOD are not directly inherited (i.e. autosomal-dominant) and have a combination of genetic and non-genetic contributing factors. However when cases of directly-inherited occur, they tend to be associated with a younger age of onset [ 28 ]. It is notable that we did not reach consensus on the statement “Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of young onset dementia”, despite this being supported by extensive research literature [ 29 ]. This may reflect a view among our experts that the diversity in causes of YOD is more important for health professionals to know, especially as Alzheimer’s disease does not predominate in this population to the same extent as in late life.

The panel also highlighted the importance of a healthy lifestyle for reducing the risk of the most common forms of young onset dementia [ 21 ], similar to a previous Delphi study that concluded that this knowledge is essential for dementia more broadly. Several non-genetic risk factors have been identified for YOD, including low participation in cognitive leisure activities, low educational attainment, stroke, transient ischemic attack and very heavy alcohol use [ 30 , 31 ]. Other potentially modifiable risk factors for dementia include physical inactivity, smoking, hypertension, obesity, diabetes, depression and low social contact [ 32 , 33 ]. Awareness of these risk factors can enable health professionals to encourage lifestyle modifications that may positively ameliorate the development and clinical course of YOD.

Delayed diagnosis and misdiagnosis of YOD are very common, with delays often related to the presence of depression or mild cognitive impairment [ 9 ]. Timely and accurate diagnosis is difficult as rarer forms of dementia and non-amnestic presentations are more common at younger ages than among older people [ 34 ]. As such, it is recommended that the diagnostic process for YOD include a formal cognitive assessment, full medical history including family history, risk assessment, physical examination including neurological examination, assessment of psychiatric, psychological and behavioural symptoms, functional assessment, neuroimaging and, where appropriate, amyloid imaging and genetic biomarkers [ 11 , 26 ]. This was acknowledged by our expert panel, who agreed that it was important for health professionals to know that a comprehensive, specialist, multi-disciplinary assessment is required, and identified the benefit of neuropsychological testing and the need to rule out reversible causes of impairment prior to diagnosing YOD. Knowledge about the need to conduct a comprehensive assessment will not only aid in making a timely, accurate diagnosis, but allow for the identification of co-existing symptoms and the initiation of symptom management and support services [ 35 ]. Additionally, it will provide an opportunity for accurate prognosis and future planning.

Treatment and care

The expert panel echoed published recommendations [ 3 , 13 ] that people with YOD require tailored, specialised, multidisciplinary services to support them following diagnosis. Research recommends the provision of support that addresses the physical, mental and social needs of people with YOD [ 32 ]. Programs that reduce social isolation and provide meaningful activities and continued engagement in skills or activities performed prior to diagnosis have been well received by people experiencing YOD and their supporters [ 3 , 4 , 12 , 36 ]. Psychosocial interventions are also recommended to manage neuropsychiatric symptoms, rather than using psychotropic medications which may be ineffective and associated with adverse effects [ 32 ]. These concepts were all agreed as essential knowledge by our panel of experts.

Most importantly, the panel agreed that health professionals should be aware that young people with dementia require age-appropriate care programs and accommodation options that take a whole-family approach. People with YOD and their support persons have expressed dissatisfaction with services that are designed for older adults. Difficulty relating to older participants, lack of security for physically agile people with YOD, and services being offered during business hours without childcare have been identified as reasons for which services targeted at people with LOD are not appropriate for people with YOD [ 3 ]. Previous research has recommended that care instead be tailored to the individual and also their family and/or support persons [ 4 , 26 ]. Support persons of people with YOD report very high rates of stress and burden [ 6 , 37 ] and children can experience a loss of care from both parents as a result.

Finally, our panel emphasised the significant financial impact of YOD. People with YOD may have to leave the workforce earlier than planned and before they are eligible to receive superannuation or pensions. This may result in their care partner being required to increase their working hours, or they may need to cease work to support them [ 5 , 6 , 26 ]. Research has shown that the impact of this can result in reduced access to services from diagnosis through to placement in residential care [ 3 ]. Holistic care for people with YOD therefore requires that health professionals are aware of these additional impacts on family members and friends.

Strengths and limitations

This international Delphi consensus study provides expert guidance about the knowledge that professionals working with people with YOD, and their families need to have to provide best-practice care. There are nonetheless important limitations to this work. Although many countries were represented, a large proportion of participants lived in Australia. This may introduce a geographical bias, and a more equal distribution of countries may provide a greater range of responses and experiences upon which to draw. Another limitation was the predominance of researchers and clinicians in the sample, particularly by round 3. Greater representation from health professionals providing YOD care in the disability and aged care sectors and individuals with a lived experience of YOD may provide a more thorough exploration of the topic. An established limitation of the Delphi study methodology is that it can be time consuming for participants to undertake. This may have contributed to the reduction in response rate over the course of this study. However, this is an issue common to other published Delphi studies [ 20 , 38 , 39 , 40 ] and the number of participants who completed round 3 within the recommended sample size for this method [ 19 , 20 ].

This international Delphi study has established the key pieces of information that experts consider essential for health professionals to understand about YOD to enable to them to deliver best-practice care. The statements indicate the breadth of knowledge that health professionals should be expected to know and can be used to guide the design and delivery of diagnostic, treatment, and support services for people with YOD and their support persons. Additionally, the statements can be used in the development of training and education materials to improve the awareness and understanding of YOD among health professionals providing care to this varied group of clients.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available in a de-identified format from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Prince M, Wimo A, Guerchet M, Ali G-C, Wu Y-T, Prina M, et al. World Alzheimer Report 2015: The global impact of dementia: An analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends. 2015 [cited 2021 Mar 24]; Available from: https://www.alzint.org/resource/world-alzheimer-report-2015/

Mayrhofer A, Shora S, Tibbs M-A, Russell S, Littlechild B, Goodman C. Living with young onset dementia: reflections on recent developments, current discourse, and implications for policy and practice. Ageing Society. 2020:1–9.

Cations M, Withall A, Horsfall R, Denham N, White F, Trollor J, et al. Why aren’t people with young onset dementia and their supporters using formal services? Results from the INSPIRED study. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0180935.

Article Google Scholar

Sansoni J, Duncan C, Grootemaat P, Capell J, Samsa P, Westera A. Younger onset dementia: a review of the literature to inform service development. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2016;31(8):693–705.

Roach P, Drummond N, Keady J. ‘Nobody would say that it is Alzheimer’s or dementia at this age’: family adjustment following a diagnosis of early-onset dementia. J Aging Stud. 2016;36:26–32.

van Vliet D, de Vugt ME, Bakker C, Koopmans RTCM, Verhey FRJ. Impact of early onset dementia on caregivers: a review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(11):1091–100.

Arai A, Matsumoto T, Ikeda M, Arai Y. Do family caregivers perceive more difficulty when they look after patients with early onset dementia compared to those with late onset dementia? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(12):1255–61.

Kaiser S, Panegyres PK. The psychosocial impact of young onset dementia on spouses. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2007;21(6):398–402.

Draper B, Cations M, White F, Trollor J, Loy C, Brodaty H, et al. Time to diagnosis in young-onset dementia and its determinants: the INSPIRED study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31(11):1217–24.

van Vliet D, de Vugt ME, Bakker C, Pijnenburg Y. a. L, Vernooij-Dassen MJFJ, Koopmans RTCM, et al. time to diagnosis in young-onset dementia as compared with late-onset dementia. Psychol Med. 2013;43(2):423–32.

O’Malley M, Parkes J, Stamou V, LaFontaine J, Oyebode J, Carter J. International consensus on quality indicators for comprehensive assessment of dementia in young adults using a modified e-Delphi approach. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;35(11):1309–21.

Millenaar JK, Bakker C, Koopmans RTCM, Verhey FRJ, Kurz A, de Vugt ME. The care needs and experiences with the use of services of people with young-onset dementia and their caregivers: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31(12):1261–76.

Stamou V, Fontaine JL, Gage H, Jones B, Williams P, O’Malley M, et al. Services for people with young onset dementia: the ‘Angela’ project national UK survey of service use and satisfaction. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;36(3):411–22.

Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(4):1008–15.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Hsu C-C, Sandford B. The Delphi Technique: Making Sense of Consensus. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2007;12(12):Article 10.

Keeney S, Hasson F, McKenna H. Consulting the oracle: ten lessons from using the Delphi technique in nursing research. J Adv Nurs. 2006;53(2):205–12.

Dalkey NC. The Delphi method: an experimental study of group opinion. Rand Corporation; 1969. Available from: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_memoranda/RM5888.html

Annear MJ, Toye C, Elliott K-EJ, McInerney F, Eccleston C, Robinson A. Dementia knowledge assessment scale (DKAS): confirmatory factor analysis and comparative subscale scores among an international cohort. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):168.

Okoli C, Pawlowski SD. The Delphi method as a research tool: an example, design considerations and applications. Inf Manage. 2004;42(1):15–29.

de Villiers PMR de, de Villiers PJT de, Kent AP. The Delphi technique in health sciences education research. Med Teach 2005;27(7):639–643.

Annear MJ, Toye C, McInerney F, Eccleston C, Tranter B, Elliott K-E, et al. What should we know about dementia in the 21st century? A Delphi consensus study. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15(1):5.

Yousuf M. Using Experts` Opinions Through Delphi Technique. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2019;12(12):Article 4.

van der Steen JT, Radbruch L, Hertogh CMPM, de Boer ME, Hughes JC, Larkin P, et al. White paper defining optimal palliative care in older people with dementia: a Delphi study and recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care. Palliat Med. 2014;28(3):197–209.

Withall A, Draper B, Seeher K, Brodaty H. The prevalence and causes of younger onset dementia in eastern Sydney. Aust Int Psychogeriatrics. 2014;26(12):1955–65.

Rossor MN, Fox NC, Mummery CJ, Schott JM, Warren JD. The diagnosis of young-onset dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(8):793–806.

Draper B, Withall A. Young onset dementia. Intern Med J. 2016;46(7):779–86.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Spreadbury JH, Kipps CM. Understanding important issues in young-onset dementia care: the perspective of healthcare professionals. Neurodegenerative Disease Manag. 2018;8(1):37–47.

Jarmolowicz AI, Chen H-Y, Panegyres PK. The patterns of inheritance in early-onset dementia: Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2015;30(3):299–306.

Vieira RT, Caixeta L, Machado S, Silva AC, Nardi AE, Arias-Carrión O, et al. Epidemiology of early-onset dementia: a review of the literature. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2013;9:88–95.

Cations M, Draper B, Low L-F, Radford K, Trollor J, Brodaty H, et al. Non-genetic risk factors for degenerative and vascular young onset dementia: results from the INSPIRED and KGOW studies. Rouch I, editor. JAD. 2018;62(4):1747–58.

Cations M, Withall A, Draper B. Modifiable risk factors for young onset dementia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32(2):138–43.

Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the lancet commission. Lancet. 2020;396(10248):413–46.

Norton S, Matthews FE, Barnes DE, Yaffe K, Brayne C. Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: an analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(8):788–94.

Koedam ELGE, Lauffer V, van der Vlies AE, van der Flier WM, Scheltens P, Pijnenburg YAL. Early-versus late-onset Alzheimer’s disease: more than age alone. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;19(4):1401–8.

Masellis M, Sherborn K, Neto PR, Sadovnick DA, Hsiung G-YR, Black SE, et al. Early-onset dementias: diagnostic and etiological considerations. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2013;5(1):S7.

Richardson A, Pedley G, Pelone F, Akhtar F, Chang J, Muleya W, et al. Psychosocial interventions for people with young onset dementia and their carers: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016;28(9):1441–54.

Svanberg E, Spector A, Stott J. The impact of young onset dementia on the family: a literature review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(3):356–71.

Macfarlane L, Owens G, Cruz BDP. Identifying the features of an exercise addiction: a Delphi study. J Behav Addict. 2016;5(3):474–84.

Wong HS, Curry NS, Davenport RA, Yu L-M, Stanworth SJ. A Delphi study to establish consensus on a definition of major bleeding in adult trauma. Transfusion. 2020;60(12):3028–38.

Murphy F, Doody O, Lyons R, Gallen A, Nolan M, Killeen A, et al. The development of nursing quality care process metrics and indicators for use in older persons care settings: a Delphi-consensus study. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75(12):3471–84.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support of Ian Gladstone, Michael King, and Sue King in completing this research.

This research was funded by a Dementia Australia Research Foundation project grant. MC is supported by a Hospital Research Foundation Early Career Fellowship and a Medical Research Future Fund and National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator Grant. KEL is supported by an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Research Award. KEE is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council and Australian Research Council Dementia Research Development Fellowship.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

College of Education, Social Work and Psychology, Flinders University, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia

Leah Couzner, Sally Day & Monica Cations

School of Psychiatry, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Brian Draper

School of Public Health and Community Medicine, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Adrienne Withall

College of Medicine and Public Health, Flinders University, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia

Kate E. Laver & Monica Cations

University of Tasmania, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia

Claire Eccleston, Kate-Ellen Elliott & Fran McInerney

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

MC conceptualised and designed the study. SD led the data collection and analysis with input from LC. LC and SD drafted the manuscript which was refined by BD, KEL, CE, FM and MC. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Monica Cations .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The study was approved by the Flinders University Social and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee (reference number 8331). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Potential participants were provided with an information sheet explaining the study and what their voluntary participation would involve. Participants were informed in the recruitment email and on the participant information sheet that their completion of the questionnaire would be accepted as their consent to participate.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

MC has been employed in the past 5 years to assist with data collection for Alzheimer’s disease drug trials funded by Janssen and Merck. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Couzner, L., Day, S., Draper, B. et al. What do health professionals need to know about young onset dementia? An international Delphi consensus study. BMC Health Serv Res 22 , 14 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-07411-2

Download citation

Received : 21 June 2021

Accepted : 13 December 2021

Published : 02 January 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-07411-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Young onset dementia

- Health professionals

- Delphi study

BMC Health Services Research

ISSN: 1472-6963

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Developing dementia: The existential experience of the quality of life with young-onset dementia - A longitudinal case study

Affiliations.

- 1 Norwegian National Advisory, Vestfold Hospital Trust, Unit on Ageing and Health, Norway; Norwegian Social Research (NOVA), Oslo Metropolitan University, Norway.

- 2 Norwegian National Advisory Unit on Ageing and Health, Vestfold Hospital Trust, Norway; University of South-Eastern Norway, Norway.

- 3 Center for Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders, Institute of Psychiatry, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

- PMID: 30058371

- DOI: 10.1177/1471301218789990

Keywords: coping; early-onset dementias; existential needs; health care; health promotion; subjective experiences; young persons.

Publication types

- Case Reports

- Adaptation, Psychological*

- Age of Onset*

- Dementia / diagnosis*

- Longitudinal Studies

- Middle Aged

- Quality of Life / psychology*

Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- Winter 2024 | VOL. 36, NO. 1 CURRENT ISSUE pp.A5-81

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

The Diagnostic Challenge of Young-Onset Dementia Syndromes and Primary Psychiatric Diseases: Results From a Retrospective 20-Year Cross-Sectional Study

- Paraskevi Tsoukra , M.D., M.Sc. ,

- Dennis Velakoulis , F.R.A.N.Z.C.P., M.B.B.S. ,

- Pierre Wibawa , M.B.B.S. ,

- Charles B. Malpas , Ph.D., F.C.C.N. ,

- Mark Walterfang , F.R.A.N.Z.C.P., M.B.B.S. ,

- Andrew Evans , F.R.A.N.Z.C.P., M.B.B.S. ,

- Sarah Farrand , F.R.A.N.Z.C.P., M.B.B.S. ,

- Wendy Kelso , C.C.N., M.A.P.S. ,

- Dhamidhu Eratne , F.R.A.N.Z.C.P., M.B.Ch.B. ,

- Samantha M. Loi , F.R.A.N.Z.C.P., M.B.B.S .

Search for more papers by this author

Distinguishing a dementia syndrome from a primary psychiatric disease in younger patients can be challenging and may lead to diagnostic change over time. The investigators aimed to examine diagnostic stability in a cohort of patients with younger-onset neurocognitive disorders.

A retrospective review of records was conducted for patients who were admitted to an inpatient neuropsychiatry service unit between 2000 and 2019, who were followed up for at least 12 months, and who received a diagnosis of young-onset dementia at any time point. Initial diagnosis included Alzheimer’s disease-type dementia (N=30), frontotemporal dementia (FTD) syndromes (N=44), vascular dementia (N=7), mild cognitive impairment (N=10), primary psychiatric diseases (N=6), and other conditions, such as Lewy body dementia (N=30).

Among 127 patients, 49 (39%) had a change in their initial diagnoses during the follow-up period. Behavioral variant FTD (bvFTD) was the least stable diagnosis, followed by dementia not otherwise specified and mild cognitive impairment. Compared with patients with a stable diagnosis, those who changed exhibited a higher cognitive score at baseline, a longer follow-up period, greater delay to final diagnosis, and no family history of dementia. Patients whose diagnosis changed from a neurodegenerative to a psychiatric diagnosis were more likely to have a long psychiatric history, while those whose diagnosis changed from a psychiatric to a neurodegenerative one had a recent manifestation of psychiatric symptoms.

Conclusions:

Misdiagnosis of younger patients with neurocognitive disorders is not uncommon, especially in cases of bvFTD. Late-onset psychiatric symptoms may be the harbinger to a neurodegenerative disease. Close follow-up and monitoring of these patients are necessary.

Young-onset dementia, a dementia syndrome with onset under the age of 65, accounts for approximately 8% of all people with dementia ( 1 ). The presenting symptoms of young-onset dementia may be atypical and differ from those seen in late-onset dementia ( 2 ). The differential diagnosis of young-onset dementia can be broad ( 3 ) and includes neurological, neurodegenerative, and primary psychiatric disorders. The clinical distinction can be most difficult in patients with this type of dementia and prominent frontal or white matter change, as seen in the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) ( 4 , 5 ), the “frontal variant” of Alzheimer’s disease ( 6 ), white matter disorders, such as leukodystrophies ( 7 , 8 ), or vascular dementias ( 9 , 10 ). Such patients may commonly present with personality, mood, or behavioral changes, including apathy, social withdrawal, mood disturbance, stereotyped/compulsive behaviors, disinhibition, or social inappropriateness.

Distinguishing a primary psychiatric disorder from a frontotemporal syndrome can be challenging ( 11 , 12 ), especially in patients with a long-standing history of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, given the potential overlap at the level of cognition and/or psychiatric symptomatology ( 13 ). In a proportion of patients with young-onset dementia, the difficulty in diagnosis may lead to diagnostic change over time from a psychiatric to a neurodegenerative diagnosis or vice versa. While some studies ( 13 , 14 ) have described patients with a psychiatric diagnosis subsequently diagnosed with an underlying neurodegenerative condition, few studies have specifically addressed the question of diagnostic stability or change in patients with younger-onset dementia.

In a recent study, Perry et al. ( 15 ) examined diagnostic stability across neurodegenerative diseases in patients seen on at least two occasions in a tertiary memory service, aiming to identify factors that could influence diagnostic change. The investigators reviewed clinical records of patients diagnosed with bvFTD, language variants FTD, Alzheimer’s disease, corticobasal syndrome, and progressive supranuclear palsy. Diagnostic change occurred frequently in patients with bvFTD (32%) and was more common in patients with possible bvFTD (70%) compared with probable bvFTD (15%). In 22% of bvFTD patients, the diagnosis changed to a nondementia diagnosis, such as multiple sclerosis, or a psychiatric diagnosis, such as bipolar disorder.

Krudop et al. ( 16 ) examined patients presenting to a specialized memory clinic who were initially diagnosed as having bvFTD. After a 2-year follow-up period, 49% of these patients underwent a change in diagnosis. Thirty-two percent were reclassified with a primary psychiatric diagnosis, most commonly mood disorders, while 17% received other neurologic diagnoses, most commonly neurodegenerative diagnoses.

Woolley et al. ( 17 ) examined rates and risk factors for prior psychiatric diagnoses of neurodegenerative diseases (including Alzheimer’s, bvFTD, and primary progressive aphasia, among others) and reported that 28% of participants were initially given a psychiatric diagnosis. Of the dementia diagnoses, bvFTD was significantly more often initially misdiagnosed as a primary psychiatric condition, with depression being the most common diagnosis.

While the available studies have shown that diagnostic change is bidirectional (i.e., diagnoses may change from neurodegenerative to psychiatric or vice versa), individual studies have been largely unidirectional in that they have either focused on diagnostic change in patients initially diagnosed with dementia ( 15 , 16 ) or have looked retrospectively at rates of prior psychiatric diagnoses in patients with neurodegenerative diseases ( 17 ). In the present study, we aimed to address this limitation by examining diagnostic stability in both directions by investigating diagnostic change in a cohort of patients with younger-onset neurocognitive disorders referred to a neuropsychiatry service.

Study Design and Participants

An inpatient diagnostic admission to neuropsychiatry between 2000 and 2019

At least one inpatient or outpatient follow-up (≥12 months) assessment with neuropsychiatry

A diagnosis of younger-onset dementia or mild cognitive impairment at any time point between 2000 and 2019

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Melbourne Health Ethics Committee.

Demographic and Clinical Variables

Patients’ files were reviewed for the following information: age (at symptom onset and hospital admission), sex, education, alcohol and tobacco consumption, medical comorbidities, presenting symptoms, psychiatric history, and family history.

Diagnostic Information

Both inpatient and outpatient assessments included evaluation by a multidisciplinary team, consisting of a neuropsychiatrist, a neurologist, a neuropsychologist, an occupational therapist, and a social worker. Rating instruments included the Neuropsychiatry Unit Cognitive Assessment Tool (NUCOG) ( 18 ) and the Mini-Mental State Examination ( 19 ) to assess bedside cognition and the Global Assessment of Functioning scale to assess level of function. Investigations included blood and urine tests, structural and functional imaging of the brain (MRI, single-photon emission computed tomography, positron emission tomography [PET]), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis. Genetic testing was performed where clinically indicated in the presence of a strong family history. Following all multidisciplinary and multimodal assessments, a consensus diagnosis was made for all patients and recorded in the clinical file. Each patient’s inpatient and outpatient medical records were reviewed to collate diagnoses made through the patient’s time with neuropsychiatry.

All diagnoses (initial and final) were made based on established contemporaneous diagnostic criteria (DSM-IV and DSM-5) ( 20 – 23 ).

Diagnoses were grouped into the following six categories: Alzheimer’s-type dementia, FTD (including bvFTD, semantic and nonfluent variant primary progressive aphasia, and FTD with motor neuron disease [FTD-MND]), vascular dementia (VaD), mild cognitive impairment, primary psychiatric diseases (including major depressive disorder, bipolar affective disorder, and schizophrenia), and other diseases not categorized in any of the previous groups, such as Lewy body dementias (including Parkinson’s disease dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies), progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal ganglionic degeneration, and dementia not otherwise specified.

Diagnostic Outcomes

No diagnostic change

Change from a neurodegenerative diagnosis to another neurodegenerative or neurological condition (e.g., from dementia not otherwise specified to Alzheimer’s disease)

Change from a neurodegenerative diagnosis to a primary psychiatric diagnosis (e.g., from bvFTD to schizophrenia)

Change from a psychiatric diagnosis to a neurodegenerative diagnosis (e.g., from major depressive disorder to bvFTD)

We considered patients whose diagnosis was switched from a neurodegenerative to a psychiatric disorder (or vice versa) as having a “between-category” diagnostic change, while change within the neurodegenerative category was considered a “within-category” change.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are reported as means with standard deviations. Categorical variables are reported as frequencies (%). As a result of our small sample size and after testing for normality, Mann-Whitney U tests were performed to test differences in numerical variables between diagnostically stable and unstable groups. Pearson’s chi-square tests of independence were performed to compare dichotomous variables and determine differences in psychiatric and family history across the categories of change. A two-sided p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS, version 25 (IBM, Armonk, N.Y.).

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 462 patients were identified as having a dementia syndrome or mild cognitive impairment. Of these, 195 individuals were excluded, either because they were not followed up (N=156) or were followed up for less than 12 months (N=39). We excluded patients whose age at symptom onset was >65 years (N=77). Patients diagnosed with genetically confirmed dementia disorders, such as Huntington’s disease and Niemann-Pick disease type C, at their first inpatient admission were not included in our analysis. A total of 127 patients met inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis ( Figure 1 ).

FIGURE 1. Eligibility criteria for study inclusion among patients admitted to an inpatient neuropsychiatry service unit between 2000 and 2019 and received a diagnosis of young-onset dementia a

a HD=Huntington’s disease; NPC=Niemann-Pick disease type C.

Of the 127 patients who met inclusion criteria, 82 were male (64.6%), the mean age at onset was 50.1 years (SD=8.6), the mean duration of symptoms until initial diagnosis was 3.1 years (SD=2.2), and the mean time of follow-up was 40 months (SD=28.1). A detailed summary of participants’ baseline characteristics is presented in Table 1 .

TABLE 1. Baseline characteristics at first presentation among young-onset dementia patients who met study inclusion criteria

Patients who were not followed up by neuropsychiatry (N=156) included patients who returned to private or public specialist care or were lost to follow-up. Compared with the 127 patients who met inclusion criteria, these patients were older at admission (mean age: 57.6 years versus 51.0 years, p<0.05) and at symptom onset (mean age: 54.4 years versus 47.8 years, p<0.05). The most common diagnoses among patients who were not followed up were Alzheimer’s disease (21.9%) and VaD (12.4%).

Diagnostic Change

The key finding among patients who met inclusion criteria was that there was a change of diagnosis during the study period for 39% of these patients (N=49). bvFTD was the least stable diagnosis, with almost half of patients (47.1%) undergoing a diagnostic change. Dementia not otherwise specified was the second least stable diagnosis, with 16% of patients shifting to another neurodegenerative/neurological or psychiatric condition. Changes in Alzheimer’s and VaD dementia were less common (10.2% and 4.1%, respectively). No patients diagnosed with a language variant FTD (semantic dementia [N=6]), nonfluent primary progressive aphasia (N=3), or FTD-MND (N=1) had a diagnostic change. Male participants had a change more frequently than females (69.4% and 30.6%, respectively). Changes in the 49 patients presenting with unstable diagnoses are summarized in Table 2 .

a AD=Alzheimer’s disease; FTD=frontotemporal dementia; VaD=vascular dementia.

b The patient’s diagnosis changed from behavioral variant FTD to semantic variant FTD.

TABLE 2. Changes between initial and final diagnoses during the follow-up period among patients with young-onset dementia a

For the patients initially diagnosed with bvFTD, five later received “other” diagnoses, including hereditary spastic paraplegia, central nervous system (CNS) vasculitis, Parkinson’s disease dementia, and dementia not otherwise specified, while one patient within the FTD group was rediagnosed as having the semantic variant. Patients presenting with an unclear condition at first admission (categorized in the “other” group) had their diagnosis revised at subsequent visits to more specific diseases, such as multiple system atrophy, Parkinson’s disease dementia, paraneoplastic encephalitis, or mild cognitive impairment. Two patients diagnosed with progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal ganglionic degeneration at first admission were switched to bvFTD and dementia with Lewy bodies, respectively.

Comparison of Patients With No Change in Diagnosis With Those With a Diagnostic Change

Compared with patients with a stable diagnosis, patients with a diagnostic change exhibited a higher NUCOG score at baseline (mean=74.9, 95% CI=70.8, 79.1 versus mean=65.4, 95% CI=60.8, 69.9, p<0.05), a longer follow-up period (mean=47.5 months, 95% CI=38.5, 56.5 versus mean=35.3 months, 95% CI=29.7, 41, p<0.05), and a greater delay to final diagnosis (mean=5.7 years, 95% CI=4.7, 6.7 versus mean=3.1 years, 95% CI=2.6, 3.6, p<0.01) and were more likely to have a history of hypertension (30.6% versus 15.4%, χ 2 =4.1, p<0.05). Patients with a family history of dementia were more likely to have a stable diagnosis compared with those who did not report family history (48.1% versus 20.8%, χ 2 =9.3, p<0.01). No difference was detected between the two groups regarding age at onset, education, smoking habits, and alcohol consumption.

Categories of Diagnostic Change

Within-category diagnostic change..

Of the 49 patients whose initial diagnosis was revised, 30 (23.6%) underwent a within-category diagnostic change. For two patients who were initially diagnosed with bvFTD, the change to a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease was influenced by CSF and amyloid PET biomarkers. Another participant had the diagnosis revised from bvFTD to hereditary spastic paraplegia after undergoing genetic testing. Genetics led to a change from mild cognitive impairment to Huntington’s disease in one patient. Patients given a diagnosis of dementia not otherwise specified at the time of first admission had a more precise diagnosis of bvFTD, posterior cortical atrophy, and chronic inflammatory encephalopathy when they were subsequently seen at follow-up. Two patients with Alzheimer’s disease developed common vascular copathology, while three cases of mild cognitive impairment were revised to Parkinson’s disease dementia (N=2) and progressive supranuclear palsy (N=1).

For the 49 patients who had a diagnostic change during follow-up, those who reported a negative psychiatric history were more likely to have a within-category change than those who reported a positive psychiatric history (χ 2 =4.8, p<0.05; odds ratio=4.6, 95% CI=1.1, 19.4). No differences were detected in terms of medical comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia) and alcohol and tobacco consumption.

Between-category diagnostic change.

Thirteen patients (10.2% of the total group) switched from a neurodegenerative to a psychiatric diagnosis (subtype I).

Six patients (4.7% of the total group) switched from a psychiatric to a neurodegenerative diagnosis (subtype II).

Further clinical details of these 19 patients are presented in Table 3 . Of the 13 patients in the first subtype (patients 1–13; Table 3 ), six had schizophrenia, three had bipolar disorder, one had depression, and three had no evidence of a progressive neurodegenerative disorder. Of the six patients with the second subtype (patients 14–19; Table 3 ), half developed an FTD diagnosis.

a AD=Alzheimer’s disease; BPAD=bipolar affective disorder; bvFTD=behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia; Nil=negative history of psychiatric symptoms; NOS=not otherwise specified; NR=not reported; OCD=obsessive-compulsive disorder; STM=short-term memory; VaD=vascular dementia.

TABLE 3. Clinical details of patients with a between-category diagnostic change a

There was no difference between these two subtypes in the age at which participants first exhibited symptoms (subtype I: mean age=47.6 years versus subtype II: mean age=51.6 years, p=0.32). Of the participants in this between-category diagnostic change group, 84.2% (N=16) reported a positive history of psychiatric symptoms (depressive, psychotic). The presence of cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and smoking) was not associated with a diagnostic change in this group.

Patients in subtype I (i.e., those who changed from a neurodegenerative to a psychiatric diagnosis) were more likely to have a long psychiatric history (>10 years, N=8/13; 61.5%) compared with patients in subtype II (i.e., those who switched from a psychiatric to a neurodegenerative diagnosis), the majority of which had a recent manifestation of psychiatric symptoms (<10 years, N=5/6; 83.3%) (χ 2 =7.2, p<0.05).

This study examined bidirectional diagnostic stability across neurodegenerative and psychiatric diseases in a cohort of patients diagnosed with younger-onset dementia at presentation or subsequent follow-up in a single tertiary specialist clinical service. Several important findings emerged from this investigation. Of 127 patients, 49 (39%) had their initial diagnoses revised during the follow-up period. The observed diagnostic changes included change from neurodegenerative disease to another neurodegenerative or neurological condition (24%), from a neurodegenerative diagnosis to a psychiatric diagnosis (10%), and from a psychiatric diagnosis to a neurodegenerative diagnosis (5%). Alzheimer’s disease-type dementia was the most stable diagnosis over time. Consistent with previous literature, a diagnosis of bvFTD was found to be the most likely diagnosis to change during the follow-up period. For patients with a diagnosis of bvFTD, their diagnosis changed to another neurodegenerative or neurological diagnosis (24%) or to a psychiatric diagnosis (21%). On the other hand, 60% of patients finally diagnosed with bvFTD were given an initial diagnosis of depression, a finding consistent with that of Woolley et al. ( 17 ). Finally, we identified that a higher score on cognitive testing at baseline, a negative family history of dementia, and a positive psychiatric history were associated with a greater likelihood of diagnostic change.

From a clinical and patient perspective, the most significant diagnostic changes were the between-category changes (i.e., when the diagnosis changed from neurodegenerative to psychiatric or vice versa). In 19 patients who presented with a between-category change, the presence and duration of psychiatric symptoms played a significant role in the reconsideration of the patients’ initial diagnosis. Eight of the nineteen patients (42%) had a psychiatric history >10 years at the time of an initial diagnosis of a dementia. In all eight patients, the initial dementia diagnosis was subsequently revised to a psychiatric diagnosis based on lack of progression and, in some cases, improvement of cognitive impairment. Eight of the 19 patients (42%) had a history of psychiatric symptoms <10 years. More than half of these eight patients, who were initially diagnosed with a psychiatric condition (63%), were subsequently diagnosed with a neurodegenerative disease. It was believed that in these individuals, the late-onset psychiatric symptoms reflected a prodromal phase of an underlying neurodegenerative condition.