Why Representation Matters and Why It’s Still Not Enough

Reflections on growing up brown, queer, and asian american..

Posted December 27, 2021 | Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

- Positive media representation can be helpful in increasing self-esteem for people of marginalized groups (especially youth).

- Interpersonal contact and exposure through media representation can assist in reducing stereotypes of underrepresented groups.

- Representation in educational curricula and social media can provide validation and support, especially for youth of marginalized groups.

Growing up as a Brown Asian American child of immigrants, I never really saw anyone who looked like me in the media. The TV shows and movies I watched mostly concentrated on blonde-haired, white, or light-skinned protagonists. They also normalized western and heterosexist ideals and behaviors, while hardly ever depicting things that reflected my everyday life. For example, it was equally odd and fascinating that people on TV didn’t eat rice at every meal; that their parents didn’t speak with accents; or that no one seemed to navigate a world of daily microaggressions . Despite these observations, I continued to absorb this mass media—internalizing messages of what my life should be like or what I should aspire to be like.

Because there were so few media images of people who looked like me, I distinctly remember the joy and validation that emerged when I did see those representations. Filipino American actors like Ernie Reyes, Nia Peeples, Dante Basco, and Tia Carrere looked like they could be my cousins. Each time they sporadically appeared in films and television series throughout my youth, their mere presence brought a sense of pride. However, because they never played Filipino characters (e.g., Carrere was Chinese American in Wayne's World ) or their racial identities remained unaddressed (e.g., Basco as Rufio in Hook ), I did not know for certain that they were Filipino American like me. And because the internet was not readily accessible (nor fully informational) until my late adolescence , I could not easily find out.

Through my Ethnic Studies classes as an undergraduate student (and my later research on Asian American and Filipino American experiences with microaggressions), I discovered that my perspectives were not that unique. Many Asian Americans and other people of color often struggle with their racial and ethnic identity development —with many citing how a lack of media representation negatively impacts their self-esteem and overall views of their racial or cultural groups. Scholars and community leaders have declared mottos like how it's "hard to be what you can’t see," asserting that people from marginalized groups do not pursue career or academic opportunities when they are not exposed to such possibilities. For example, when women (and women of color specifically) don’t see themselves represented in STEM fields , they may internalize that such careers are not made for them. When people of color don’t see themselves in the arts or in government positions, they likely learn similar messages too.

Complicating these messages are my intersectional identities as a queer person of color. In my teens, it was heartbreakingly lonely to witness everyday homophobia (especially unnecessary homophobic language) in almost all television programming. The few visual examples I saw of anyone LGBTQ involved mostly white, gay, cisgender people. While there was some comfort in seeing them navigate their coming out processes or overcome heterosexism on screen, their storylines often appeared unrealistic—at least in comparison to the nuanced homophobia I observed in my religious, immigrant family. In some ways, not seeing LGBTQ people of color in the media kept me in the closet for years.

How representation can help

Representation can serve as opportunities for minoritized people to find community support and validation. For example, recent studies have found that social media has given LGBTQ young people the outlets to connect with others—especially when the COVID-19 pandemic has limited in-person opportunities. Given the increased suicidal ideation, depression , and other mental health issues among LGBTQ youth amidst this global pandemic, visibility via social media can possibly save lives. Relatedly, taking Ethnic Studies courses can be valuable in helping students to develop a critical consciousness that is culturally relevant to their lives. In this way, representation can allow students of color to personally connect to school, potentially making their educational pursuits more meaningful.

Further, representation can be helpful in reducing negative stereotypes about other groups. Initially discussed by psychologist Dr. Gordon Allport as Intergroup Contact Theory, researchers believed that the more exposure or contact that people had to groups who were different from them, the less likely they would maintain prejudice . Literature has supported how positive LGBTQ media representation helped transform public opinions about LGBTQ people and their rights. In 2019, the Pew Research Center reported that the general US population significantly changed their views of same-sex marriage in just 15 years—with 60% of the population being opposed in 2004 to 61% in favor in 2019. While there are many other factors that likely influenced these perspective shifts, studies suggest that positive LGBTQ media depictions played a significant role.

For Asian Americans and other groups who have been historically underrepresented in the media, any visibility can feel like a win. For example, Gold House recently featured an article in Vanity Fair , highlighting the power of Asian American visibility in the media—citing blockbuster films like Crazy Rich Asians and Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings . Asian American producers like Mindy Kaling of Never Have I Ever and The Sex Lives of College Girls demonstrate how influential creators of color can initiate their own projects and write their own storylines, in order to directly increase representation (and indirectly increase mental health and positive esteem for its audiences of color).

When representation is not enough

However, representation simply is not enough—especially when it is one-dimensional, superficial, or not actually representative. Some scholars describe how Asian American media depictions still tend to reinforce stereotypes, which may negatively impact identity development for Asian American youth. Asian American Studies is still needed to teach about oppression and to combat hate violence. Further, representation might also fail to reflect the true diversity of communities; historically, Brown Asian Americans have been underrepresented in Asian American media, resulting in marginalization within marginalized groups. For example, Filipino Americans—despite being the first Asian American group to settle in the US and one of the largest immigrant groups—remain underrepresented across many sectors, including academia, arts, and government.

Representation should never be the final goal; instead, it should merely be one step toward equity. Having a diverse cast on a television show is meaningless if those storylines promote harmful stereotypes or fail to address societal inequities. Being the “first” at anything is pointless if there aren’t efforts to address the systemic obstacles that prevent people from certain groups from succeeding in the first place.

Instead, representation should be intentional. People in power should aim for their content to reflect their audiences—especially if they know that doing so could assist in increasing people's self-esteem and wellness. People who have the opportunity to represent their identity groups in any sector may make conscious efforts to use their influence to teach (or remind) others that their communities exist. Finally, parents and teachers can be more intentional in ensuring that their children and students always feel seen and validated. By providing youth with visual representations of people they can relate to, they can potentially save future generations from a lifetime of feeling underrepresented or misunderstood.

Kevin Leo Yabut Nadal, Ph.D., is a Distinguished Professor of Psychology at the City University of New York and the author of books including Microaggressions and Traumatic Stress .

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Alisa Acosta

Researcher, Designer, Educator

Representation, meaning, and language

In his interview with Eve Bearne, Gunther Kress argues that literacy is “that which is about representation” (Kress, in Bearne, 2005, p. 288). Because “literacy” implies something that is mediated through text, in my previous post I questioned the idea of what constitutes a “text.” After further consideration, I feel that representation is the key; therefore, for the purposes of this post I have decided to pursue representation a bit further.

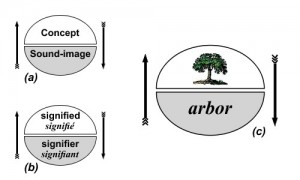

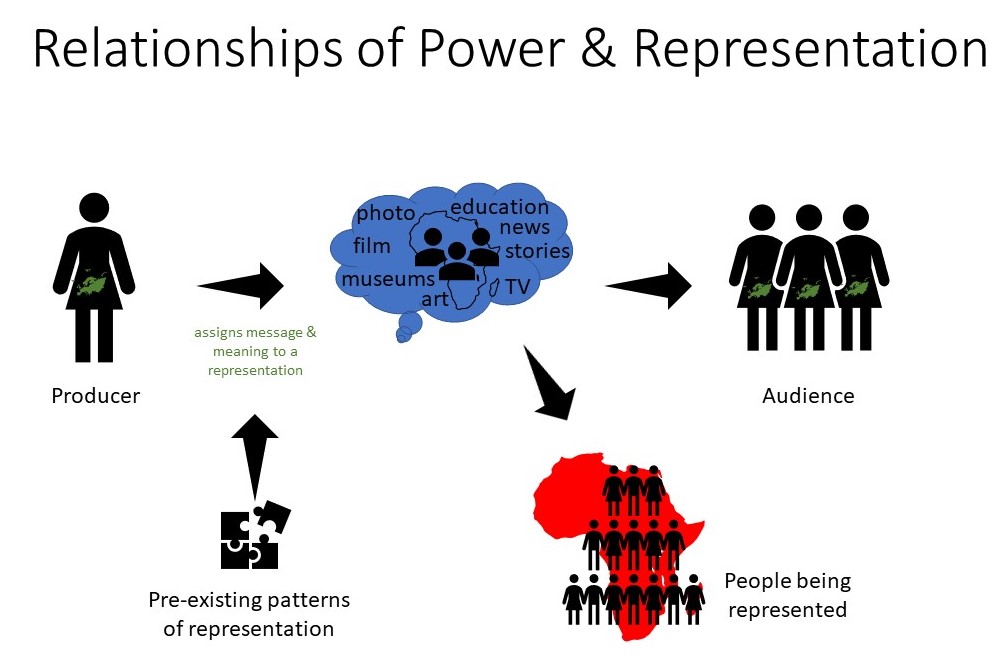

The following two graphics provide a visual model for the way I have come to understand representation through various readings (most notably, those by cultural theorist Stuart Hall). Although these models represent the culmination of my understanding, I thought it would be helpful to begin with these models and then proceed to deconstruct and explain them throughout the post.

Model 1: Theories of Representation

Cultural theorist Stuart Hall describes representation as the process by which meaning is produced and exchanged between members of a culture through the use of language, signs and images which stand for or represent things (Hall, 1997). However, there are several different theories that describe how language is used to represent the world; three of which are outlined above: reflective, intentional and constructionist.

With reflective approach to representation, language is said to function like a mirror; it reflects the true meaning of an object, person, idea or event as it already exists in the world. The Greek word ‘ mimesis’ is used for this purpose to describe how language imitates (or “mimics”) nature. Essentially, the reflective theory proposes that language works by simply reflecting or imitating a fixed “truth” that is already present in the real world (Hall, 1997).

The intentional approach argues the opposite, suggesting that the speaker or author of a particular work imposes meaning onto the world through the use of language. Words mean only what their author intends them to mean. This is not to say that authors can go making up their own private languages; communication – the essence of language – depends on shared linguistic conventions and shared codes within a culture. The author’s intended meanings/messages have to follow these rules and conventions in order to be shared and understood (Hall, 1997).

The constructionist approach (sometimes referred to as the constructivist approach) recognizes the social character of language and acknowledges that neither things in themselves nor the individual users of language can fix meaning (Hall, 1997). Meaning is not inherent within an object itself, rather we construct meaning using systems of representation (concepts and signs); I will elaborate upon these systems further in my second model. According to Hall:

“Constructivists do not deny the existence of the material world. However, it is not the material world which conveys meaning: it is the language system or whatever system we are using to represent our concepts. It is social actors who use the conceptual systems of their culture and the linguistic and other representational systems to construct meaning, to make the world meaningful and to communicate about that world meaningfully to others.” (Hall, 1997, p. 25)

There are two major variants of the constructionist approach: the semiotic approach, which was largely influenced by the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, and the discursive approach, which is associated with French philosopher Michel Foucault.

Semiotics is the study of signs in a culture (culture as language), though the semiotic approach doesn’t consider how, when or why language is used. Saussure believed that language was a rule-governed system that could be studied with the law-like precision of a science (deemed “structuralism”). He called this rule-governed structure “ la langue,” and referred to individual language acts as “ la parole” (Culler, 1976). Many found Saussure’s model appealing because they felt it offered a closed, structured, scientific approach to “the least scientific object of inquiry – culture” (Culler, 1976, p. 29).

“Saussure’s great achievement was to force us to focus on language itself, as a social fact; on the process of representation itself; on how language actually works and the role it plays in the production of meaning. In doing so, he saved language from the status of a mere transparent medium between things and meaning . He showed, instead, that representation was a practice .” (Hall, 1997, p. 34)

With the semiotic approach, in addition to words and images, objects themselves can function as signifiers in the production of meaning (Hall, 1997). Therefore from this perspective, going back to my previous post, my little book of plant pressings may in fact be considered a text since each little plant was chosen as a representative of an entire species. Because they were being used to represent certain species, it is not the actual plant clipping itself that carries the meaning, rather it is the symbolic function it serves in generalizing the morphology, physiology, taxonomy etc.

What Saussure failed to address, however, were questions related to power in language (Hall, 1997). Cultural theorists eventually rejected the idea that language could be studied with law-like precision, mainly because language doesn’t operate within a “closed” system as Saussure suggests. In a culture, language tends to operate across larger units of analysis – narratives, statements, groups of images, and whole discourses which operate across a variety of texts and areas of knowledge (Hall, 1997).

Michel Foucault used the word “ representation ” to refer to the production of knowledge (rather than just meaning) through the use of discourses (rather than just language) (Foucault, 1980). His conception of “discourse” was less concerned about whether things exist, as it was with where meaning comes from. Discourse is always context-dependent.

J.P. Gee uses the concept of Discourse to describe the “distinctive ways of speaking, listening, reading and writing, coupled with distinctive ways of acting, interacting, valuing, feeling, dressing, thinking, believing with other people and with various object, tools, and technologies so as to enact specific socially recognizable identities engaged in specific socially recognizable activities” (Gee, 2008, p. 155). As Foucault suggests in The Archaeology of Knowledge, “nothing has meaning outside of discourse” (Foucault, 1972).

Additionally, for Foucault the formation of discourses had the potential to sustain a “regime of truth” in a particular context. No form of thought could claim absolute truth, because “truth” was all relative; knowledge, linked to power, can make itself true .

“Here I believe one’s point of reference should not be the great model of language (langue) and signs, but that of war and battle. The history which bears and determines us has the form of a war rather than that of a language: relations of power not relations of meaning” (Foucault, 1980, p. 114-115)

Model 2: Systems of Representation

Meaning is always produced within language; it is the practice of representation, constructed through signifying. As described in the previous section, the “real world” itself does not convey meaning. Instead, meaning-making relies two different but related systems of representation: concepts and language .

Concepts are our mental representations of real-world phenomena. They may be constructed from physical, material objects that we can perceive through our senses (e.g. a chair, a flower, a tangerine), or they may be abstract things that we cannot directly see, feel, or touch (e.g. love, war, culture). In our minds, we organize, cluster, arrange and classify different concepts and build complex schema to describe the relations between them (Hall, 1997).

If we have a concept for something, we can say we know its meaning , but we cannot communicate this meaning without the second system of representation: language . Language can include written or spoken words, but it can also include visual images, gestures, body language, music, or other stimuli such as traffic lights (Hall, 1997). It is important to note that language is completely arbitrary, often bearing little resemblance to the things to which they refer. As Stuart Hall describes:

“Trees would not mind if we used the word SEERT – ‘trees’ written backwards – to represent the concept of them… it is not at all clear that real trees know that they are trees, and even less clear that they know that the word in English which represents the concept of themselves is written TREE whereas in French it is written ARBRE! As far as they are concerned, it could just as well be written COW or VACHE or indeed XYZ” (Hall, 1997, p. 21)

Codes govern the translation between concepts and language . These codes are culturally constructed and stabilize meanings within different languages and cultures. (Note: although meanings can be stabilized within a culture, they are never finally fixed. Social and linguistic conventions change over time as cultures evolve).

Saussure referred to the form , or the language used to refer to a concept, as “ the signifier,” and the corresponding idea it triggered in your head (the concept ) as “ the signified .” Together, these constituted “ the sign,” which he argued “are members of a system and are defined in relation to the other members of that system” (Culler, 1976, p. 19).

In order to produce meaning, signifiers have to be organized into a system of differences (Hall, 1997). For example, it is not the particular colours used in a traffic light that carries meaning – red, yellow, green, blue, pink, violet or vermillion are all arbitrary. What matters instead is that they are different and can be distinguished from one another. It is the difference between Red and Green which signifies – not the colours themselves, or even the words used to describe them (Hall, 1997).

Therefore, going back to my plant pressings dilemma, I am now inclined to argue that my book of plant clippings is in fact a text. My wild rose clipping, for example, serves as a material “ signifier ” to represent the concept of “ wild rose-ness ” (the idea ) through its physiological differences to the other plants contained in the book. Meaning is made through the fact that it represents wild roses – even though I could have chosen any other wild rose plant from which to take my representative sample. The book itself is transportable and no longer tied to its immediate context of production, which was an important criterion for Lankshear and Knobel’s definition.

However, after compiling this research on representation , I have also come to understand that the definition of “text” is less important than its interpretation:

“There is a necessary and inevitable imprecision about language… There is a constant sliding of meaning in all interpretation, a margin – something in excess of what we intend to say – in which other meanings overshadow the statement or the text; where other associations are awakened to life, giving what we say a different twist. So interpretation becomes an essential aspect of the process by which meaning is given and taken” (Hall, 1997, p. 32-33).

___________________________

References:

Bearne, E. (2005). Interview with Gunther Kress. Discourse: studies in the cultural politics of education. 26(3):287-299

Culler, J. (1976). Saussure. London: Fontana.

Foucault, M. (1972). The Archaeology of Knowledge. London: Tavistock.

Foucault, M. (1980). Power/Knowledge. Brighton: Harvester.

Gee, J.P. (2008). Chapter 8: Discourses and literacies. in Social linguistics and literacies: Ideology in discourses, 3rd edition. London: Routledge.

Hall, S. (Ed.) (1997). Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices. Chapter 1: Representation, meaning and language. London Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage in association with the Open University. pp. 15-64

Share this:

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

HUM2020: Introduction to the Humanities

sharing what is means to be human

Representation

The process of representation is shaped by social and cultural forces and systems of power. This lesson will examine the different types of representation used in the humanities, address the role of the humanities in creating representations, and explore the socio-cultural politics of representing and being represented in the humanities.

Lesson Objectives

- identify the role of symbols and representation in the humanities

- interpret symbolic meanings through different mediums in the humanities

- analyze the relationship between symbols, representation and power in the humanities

Symbols and Representation

Humans have a unique capacity to communicate meanings through representation , the process of producing symbols to represent ideas. Symbolic representation allows people to communicate about the past, present and future, and it also provides a means of conceptualizing abstract and intangible mediums such as feelings and emotions as well as philosophy, math, physics, and more.

Humans create symbols by assigning meanings to arbitrary signifiers. This means that the symbol itself does not possess an inherent quality or trait associated with the meaning it represents; the meaning has been assigned to the symbol by the creator. Consider language as an example. Language is a complex system of arbitrary symbols and their associated meanings (Saussure 1911) . Right now, you are looking at a collection of arbitrary symbols called ‘letters’ which are arranged together to form ‘words’ that are associated with meanings. There is nothing inherent to these letters that indicate their meanings. At some point in our lives, we both learned to associate these symbols with the same meanings, and through practice, we can now effortlessly translate the symbols into meanings without realizing we are doing it. It is through our shared knowledge of this collection of symbols and meanings, called ‘English,’ that we are able to communicate ideas about the past, present and future.

Can you understand the symbols and meanings below?

مع نفس المعاني، ومن خلال الممارسة العملية، يمكننا الآن ترجمة جهد الرموز والمعاني دون أن يدركوا أننا نفعل ذلك. ومن خلال معرفتنا المشتركة لهذه المجموعة من الرموز والمعاني، وتسمى باللغة الانجليزية، ونحن قادرون على توصيل الأفكار عن الماضي والحاضر والمستقبل

Δεν υπάρχει τίποτα που είναι συνυφασμένοι με αυτά τα σύμβολα που δείχνουν νοήματα. Σε κάποιο σημείο στη ζωή μας, εμείς οι δύο μάθει να συνδέσει αυτά τα σύμβολα με τα ίδια νοήματα, και μέσα από την πράξη, μπορούμε τώρα να μεταφράσει αβίαστα τα σύμβολα και τις έννοιες, χωρίς να συνειδητοποιούν το κάνουμε.

If you do not understand the system of symbols depicted in the above paragraphs, it is because you never learned to associate the system of arbitrary symbols with their assigned concepts or meanings. This shows how associations between symbols and meaning vary cross-culturally according to the unique experiences shared within a community.

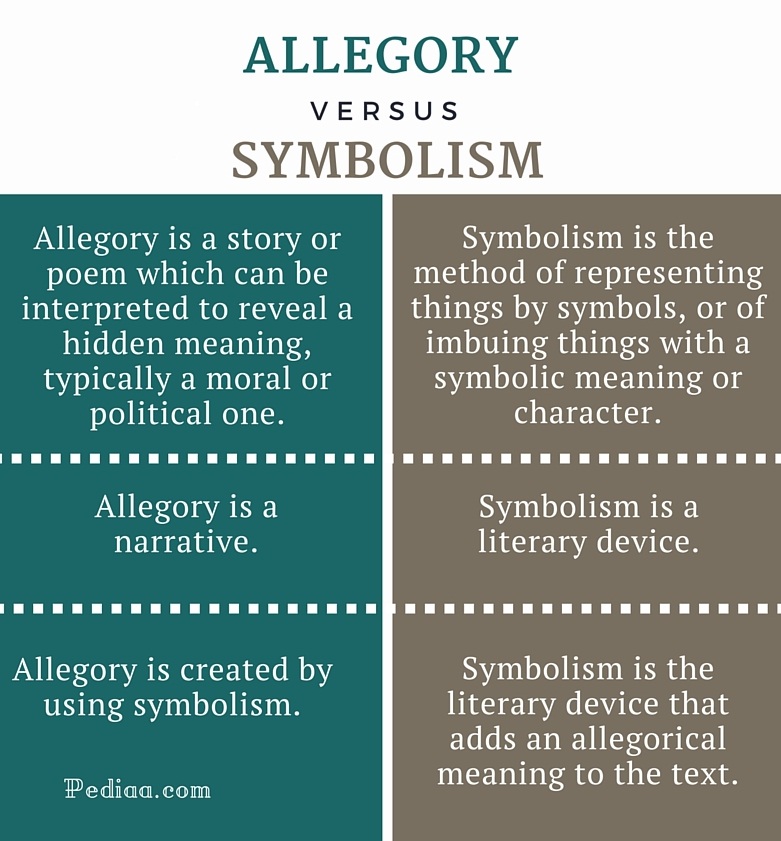

Symbolism and representation take many different forms. Writers use symbolism to strengthen their writing, making it more interesting and adding a layer of deeper meaning. Symbolic interpretation of religious scripture has a very long history. In the case of Christianity, for example, Bruno Barnhart (1989) points out that symbolic interpretation was the dominant mode of religious study for the first thousand years of Christian history. He argues that symbolism in the biblical narrative gives z deeper level of significance beyond the literal meaning.

Since ancient times, symbolism has been pervasive throughout all forms of art and literature as objects, colors, and scenarios have been used to represent meanings intended to establish an aura or mood that is not captured through simple literal translation. Plants, animals, weather, shapes and colors are common sources for symbol-making that have been used to convey complex meanings, ideas or a set of ideas.

The poem ‘Harlem,’ by Langston Hughes about the African-American experience during the first half of the 20th century, uses objects like ‘a raisin in the sun’ and a ‘festering sore’ to communicate what happens when dreams are put off or deferred. Hughes’s poem moves beyond simply describing the details of a scenario; through symbols he communicates complex emotions and feelings. This provides the reader an opportunity to connect with Hughes through the shared experience of what it feels like to have a dream deferred, or it also helps a reader empathize with the experience of another human being.

It is important to note, however, that symbols and meanings not only vary cross-culturally, the same symbol can also be used differently to communicate contradictory meanings. The color red, for example, may be used to communicate emotions such as anger, power, or anxiety while at the same time it can also represent love or embarrassment in different creative scenarios. In his short fictional story, The Red Room , Paul Bowles describes a red room within a villa that has a particularly odd feeling. Once the reader learns of the significance of the room, the color red, lends a creepy sinisterness. After reading the story, it seems unlikely that the colors mauve, beige, or blue would provide the same effect for Bowles. This is why it is important to not only learn about and identify the many different uses and modes for symbol-making, it is just as significant to situate symbology within its specific context.

It is impossible to thoroughly explore symbolism within a single lesson, or even a single semester. For now, however, we will take a brief look at a few of the most common types symbolic practices in the humanities and then move on to interrogate the ways that symbolism and representation can be situated within systems of power relations.

Symbolic Practices

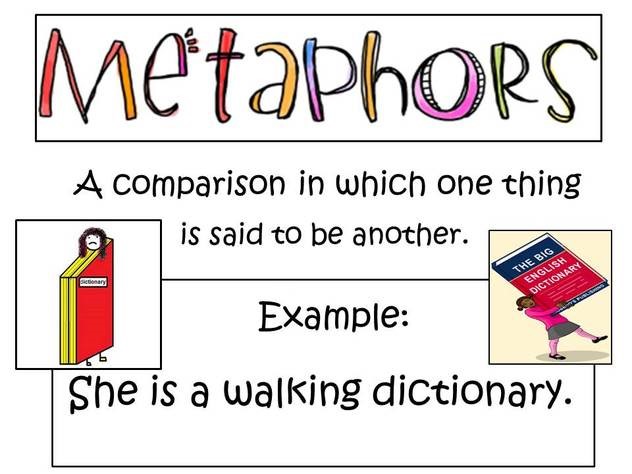

A metaphor is a figure of speech in which a word or phrase is applied to an object or action to which it is not literally applicable. A metaphor may provide clarity or identify hidden similarities between two different ideas. Metaphors are often compared with other types of figurative language, such as antithesis, hyperbole, metonymy and simile.

‘My love is like a red, red rose’ by Robert Burns (1759-1796) is one type of symbolism used in literature to represent romantic love, and more than 200 years later it continues to represent love in the primetime TV series, The Bachelor . Both metaphor and simile use comparisons between two objects or ideas,

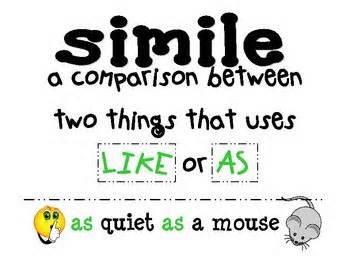

A simile makes a comparison of similarities between two different things. Unlike a metaphor, a simile draws on resemblance and relies on words such as “like” or “as” to make a direct comparison. Simile adds beauty and effect to literature. Simile can add appeal and attention to the senses by encouraging the imagination to envision what is being communicated. It also infuses a life-like quality by compelling readers to relate feelings and personal experiences. This makes it easier for the readers to understand the moods and meaning of a literary text. In Lord Jim , Joseph Conrad used simile to compare the helplessness of a soul to a small bird in a cage.

“I would have given anything for the power to soothe her frail soul, tormenting itself in its invincible ignorance like a small bird beating about the cruel wires of a cage.”

Allegory is another type of symbolism found in literature where the use of story elements such as the plot, setting, characters or objects are used to symbolize something else. George Orwell’s 1945 novel Animal Farm , uses allegorical meanings to make a commentary on oppressive institutions, and this type of symbolism remains throughout the entire literary work. In the plot of Animal Farm , the farm animals rise up against their human masters, and this mirrors and critiques the political events in Russia in the early 1900s. The animal characters symbolizing real-life political figures such as pig named Napolean, who takes charge.

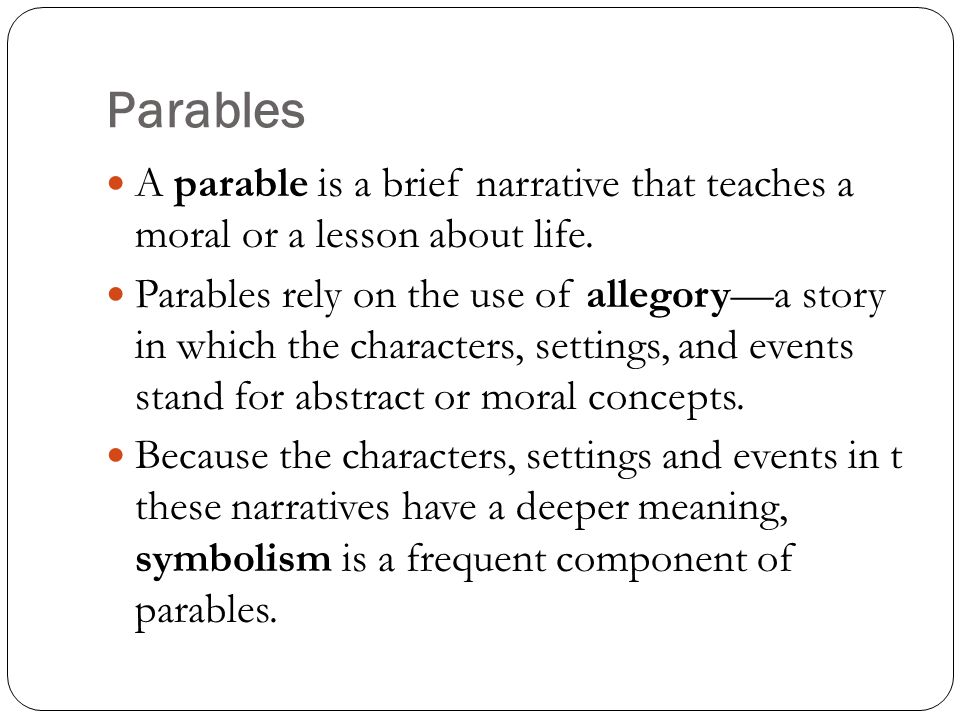

A parable is a short story that typically ends with a moral lesson. Common parables include The Boy Who Cried Wolf , The Turtle and the Rabbit , and The Good Samaritan. Parables rely on symbolism, similie, and metaphor to communicate a complex lesson in a succinct narrative. Parables are often used in religious texts such as the Upanishad, the Torah, the Bible, and the Quran.

In the second chapter of the Quran, ( Al Baqra 2: 259) for example, there is a story of a man who begins to doubt the ability of God to resurrect as he passes through a place where people died. Subsequently, God caused him to die, and then resurrected him after a hundred years. When God asked the man how long he slept, he replied only a day because the food he brought with him was still fresh. The man’s donkey, on the other hand, became a skeleton. God joined the bones, muscles, flesh and blood of the donkey and brought it back to life. This Islamic parable aims to teach a moral lesson in three ways: 1. God has control over all things and time; 2. God has power over life, death, resurrection and no other can have this power; and 3. Humans have no power, and they should put their faith only in God. Parables are great teaching tools to convey complicated moral and philosophical lessons in a way that is relatable and understandable to the reader’s personal experiences. Parables take common scenarios in day-to-day lives and use them to represent deeper meanings and messages. They are effective because the reader is guided to draw a conclusion and then apply the lesson’s principles in life.

There are a wide range of other forms of symbolic representation in the humanities, and we will take a closer look in future lessons. Now, we will examine the meanings and effects of symbolic representation of the body, particularly in terms if gender and race, within different mediums such as music videos, television, media and art.

Representing Bodies

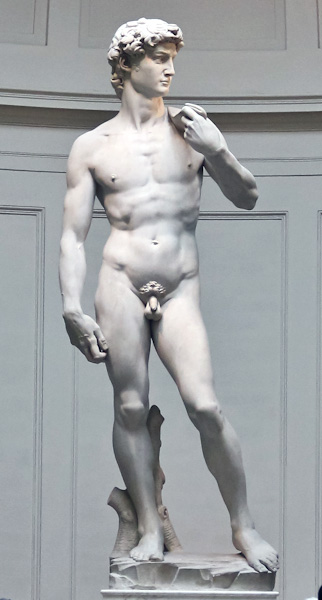

The human body has been a central focus within the humanities since prehistory. Depictions of the human body are included in ancient cave paintings, paleolithic sculptures such as the Venus of Willendorf, classical Greek and Roman statues such as the David, the Terracotta Soldiers of China, and modern television series such as Sex in the City . Throughout history the human body has been represented in an infinite number of ways. Yet the body is more than just a biological object, bodies are socialized through the meanings we assign to bodies. This is evident in the ideas and values that we assign to sex, gender, race, nationality and other categories that not only assign meanings to bodies, they also influence the way the bodies are treated as well as the right, roles and responsibilities that are assigned to people according to the ways the body is classified and categories. This makes it possible to interpret cultures and sociel systems by the ways that bodies are represented.

Watch the video below to get a sense of the multiplicity of ways the body has been represented in painting. Considr the wide variety of techniques and considerations artist takes through realism, depth, dimension, arrangement, proportion and more to assign meanings to the human symbolic form.

The video above describes how an artist’s decisions are oftentimes influenced by cultural values, ideas and motivations. In many cases, the artist nor the viewer may be aware of the values and ideas influencing the work. This complicates the manner in which bodies are represented in the humanities, because the representation of a body is a representation of the people, class and culture to which the body belongs. This makes it critical to examine who is creating the representation, who is being represented, and for whom is the representation created.

Gender, Race and Representation in the Humanities

The humanities provides a lens through which people view themselves and their own culture as well as the way people view groups and cultures they are not a part of. Movies, stories, news reports, photographs and art deliver information about peoples and cultures to an audience that may have little or no prior experience engaging with the peoples and cultures being represented. This is why it is important to think critically about the ways people are portrayed in the humanities.

Critical Theory is an analytical approach to assess and evaluate how power informs social interactions. Studying representations of race and gender in the humanities allows us to learn about race and gender relationships throughout history and across cultures. By studying gendered and racialized representations in the humanities (such as in language, literature, art, music, and popular media), we can interpret how meanings and ideas are assigned to gender and race by certain members of a particular society. This is why it is important to identify the producer of the imagery and the individual or group being produced.

In his documentary, Dream Worlds , Media Studies professor Sut Jhally, examines how representations of women, gender and heterosexual relationships in popular music videos reflects a culture of male entitlement and the hyper-sexualization of women as objects for men’s pleasure. He also reflects on the ways that these representations can influence social and sexual relationships in the real lives of the audience.

Sut Jhally critically examines representation of gender, sex and sexuality in specific music videos by investigating the relationship between those who created the representation (men) and who is being represented (women.) By doing this, he is able to address how status and power relationships between men and women inform and are informed by gendered relationships in the society where the videos are produced.

Along the same lines, Byron Hurt’s documentary film, Hip Hop Beyond Beats and Rhymes, critically examines how race and gender is represented in hip hop music and videos. Hurt’s investigation into the hip hop record industry reveals that the industry is controlled by white record label executives producing music and imagery for a predominantly young white male consumer base.

Although Hurt and Jhally rely on music videos from the 90s, music and media produced by current viral sensation, Takashi 69, shows that the same pejorative representations of race and gender are pervasive today.

Like music videos, a critical and comparative examination of visual art, literature and storytelling can reveal information about gender and race throughout history.

In her book, The Serpent and the Goddess , Mary Condren analyzes how the declining status of women in ancient Ireland during Christianization parallels changes in the mythology of Brigid. The pre-eminent Goddess in early Irish religious traditions was initially considered a powerful female diety and served as the patroness of poetry, smithing, medicine, arts and crafts, cattle and other livestock, sacred wells, and serpents. During the Christianization of Ireland, however, stories and myths about Brigid changed over time. Pre-Christian folklore initially presented her as a woman of immense power and a triple diety. After the arrival of the Christian Saxons, new stories protrayed her as a weak goddess. In time, the goddess Brigid was transformed into a Christian saint of the same name. According to medievalist Pamela Berger, Christian “monks took the ancient figure of the mother goddess and grafted her name and functions onto her Christian counterpart.” Today, St. Brigid is associated with perpetual, sacred flames, such as the one maintained by 19 nuns at her sanctuary in Kildare, Ireland. Both the goddess and saint are associated with holy wells, at Kildare and many other sites in the Celtic lands. Saint Brigid shares many of the goddess’s attributes and her feast day on 1 February was originally a pagan festival (Imbolc) marking the beginning of spring.

Cultural ideas about men and masculinity are also reproduced within the humanities. Ancient mythology of the Greeks and Romans reflects classical ideas about men, power and authority as well as gender relationships between men and men with women. Religious texts codify roles and expectations for men, relations with women, and men’s role in marriage and families.

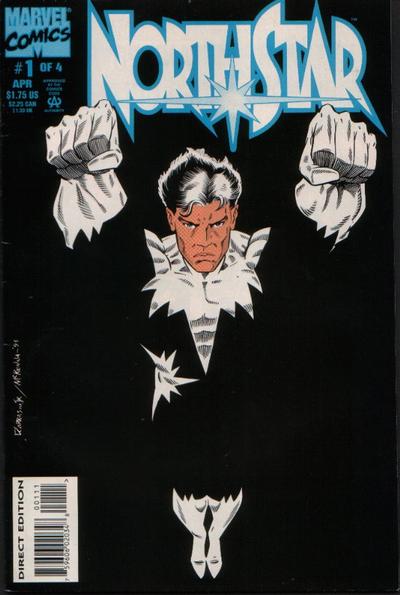

Representations of superheroes in popular American comics have traditionally presented a narrow focus on men, heroism, and masculinity. Representations of ‘superheroes’ provided hyper-masculinized representations for men and boys while at the same time challenging normative ideas. In the article, ‘ Superhero Masculinity ,’ Steven Jones points out that superheroes can represent new models for men and boys beyond power and authority by revealing binary or dual relationships such as superman and Clark Kent, Batman and Robin, and by presenting the first gay superhero, Northstar, in 1979 with an official coming out (‘I am gay’) in 1992. Changing representations of male superheroes reflects changing cultural norms and values about men, gender and sexuality.

Visit the MOMA learning module and read the brief lessons, The Body in Art and Constructing Gender.

The Politics of Power in Representing Races and Cultures

Critical theory in the late twentieth century identified how relationships of power and representation lend to distinctive patterns in the humanities. In most cases, representations are produced by those who have power, and the powerless are usually the ones being represented. This creates a bias in representative forms. In his book, Orientalism (1978), Edward Said points out the social and political implications associated with power and representation as he described the inconsistencies between representations of Arab men in media and film and his own experiences as an Arab man.

According to Said, representations of the Middle East and Arab cultures had nothing to do with the realities of life in the region and had everything to do with the unequal relationship of power in colonial domination. He defined Orientalism as a prejudiced outsider representation shaped by the attitudes of imperialists in order to justify the occupation of foreign territories and the exploitation of indigenous people who live in those territories. In essence, Said argues that those in power represent the people they oppress in ways that justify their oppression. (fo rmore on this, watch the documentary “ Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood vilifies a people on Vimeo.)

Said’s analysis primarily targets artistic representations of the Middle East by European artists and writers, yet his critique on representation and power has been expanded to address pejorative representations of colonized and oppressed people throughout the world; Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the indigenous populations of North America. It has informed more critical analysis of race and representation within a cultural group by scholars such as Stuart Hall. The video below gives a synopsis of the underlying thesis in Hall’s work.

The work of Said, Hall and other scholars of critical theory reveals patterns of Othering, a process of creating a representation of a person or group that appears foreign, alien and strange to the viewer. The ‘Other’ is created through Binary Opposition , a key concept in structuralism (a theory of sociology, anthropology and linguistics) that states that all elements of human culture can only be understood in relation to one another and how they function within a larger system or the overall environment. Light is defined in relationship to dark, good needs evil, etc. Binary oppositions are prevalent in the humanities where relationships between different groups of people (rich and poor, white and black, men and women, gay and straight, etc.) are represented. A key aspect of Othering is that the producer and the receiver of what is produced (audience, viewer, listener) are of the same group, but the person or people represented is excluded. These representations create or reinforce boundaries between groups of people and promote prejudice and discrimination of those who are othered in the representation due to fear induced by the representation.

As the identity lesson pointed out, the humanities also provides a platform for people to deconstruct pejorative representations from the past and reconstruct self-representations that present a new interpretation of life and culture from all perspectives. As artists, writers, film makers, philosophers and the like contribute to humanities as a practice, humanities as a field can benefit from the addition of diverse perspectives, unique experiences, and different ways of viewing the world. Literary works such as the novella, A Small Place by Jamaica Kincaid , provides a window into the lived experiences of post-colonialism in the Caribbean. Zora Neale Hurston ( Their Eyes were Watching God ) and Alice Walker ( The Color Purple ) are part of an elite league of African-American female writers who take the experiences of African American women from the margins and into the mainstream. Films produced by Spike Lee’s production company, 40 Acres and a Mule Filmworks , aims to redefine representations of blackness in Hollywood while the film, The Joy Luck Club , based on Amy Tan’ s first best-selling book, countered popular stereotypes about Asian women. African artists such as El Anatusi and Nnenna Okore are rocking the art world with a unique style that integrates ancient African techniques with cutting edge technologies.

As Thelma Golden points out in her Ted Talk below, the humanities not only reflects a culture, it can also provide a means to change it.

Symbols and Representation in the Humanities

When we enter into the next module which begins the analysis component in this course, it is important to contemplate the power of symbol-making and the socio-cultural politics of representation in the humanities as we dig deeper into various mediums such as literature, poetry, art, film, and other types of expression.

Questions to Consider

- What are symbols and how are they created?

- How can the human body be symbolic?

- How is critical theory applied in the humanities?

- Why is it important to identify the producer and the produced while engaging representations of people?

References and Readings

To learn more about symbols and representation in the humanities, explore the links below.

- Hall, S. (Ed.). (1997). Culture, media and identities. Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices. Sage Publications, Inc; Open University Press.

- Hall, Stuart. ‘Cultural Identity and Cinematic Representation’ in Permutations of Difference.

- Living Arts Originals website.

- ‘Symbols in Art: Who’s who?’ Smithsonian education.

- ‘Symbols in Art’ Britannica online .

- ‘Electronic Empires: Orientalism Revisted in the Military Shooter’ Hoglund

- Orientalism, Khan Academy

- Students Against Othering

- Byron Hurt. Hip Hop Beyond Beats and Rhymes (documentary)

What did you learn about symbols and representation in this lesson? Take the ungraded quiz below to find out.

[slickquiz id=5]

For Discussion in Canvas

In his article, Electronic Empires , Hoglund applied Edward Said’s theoretical perspective on Orientalism to show how the representations of Arab men in American video games contribute to a pattern of negative representations of Arab people created by people who are not members of the Arab community. Search the internet for another example of Orientalism / Othering in the humanities (film, art, song, games, etc.) and conduct your own analysis using Said’s and or Hall’s theoretical framework by answering the following questions:

- Who is represented and who is doing the representing?

- What types of meanings are assigned to the representation of the person or group?

- What type of bias or prejudice is communicated by the representation?

- In what ways does the representation serve to promote or justify the oppression, exploitation or inequality of the person or people being represented?

- Be sure to embed or include a weblink to the image or representation in your post.

For Your Creative Journal

Create an ‘alternative representation’ that goes against the grain of popular cultural representations, or stereotypes, that are pervasive in media such as art, film, and literature. Use a representation that is taken for granted and reverse it. You can express your alternative representation as a character, short story, image, song, or any medium you prefer. Provide a brief explanation of your representation.

When you complete this lesson, study your notes for this module and prepare to take the quiz before moving on to the next module, Analysis I .

Encyclopedia of Tourism pp 788–790 Cite as

Representation, cultural

- Carla A. Santos 3 &

- Erin McKenna 3

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2016

119 Accesses

Representation is a concept that has long engaged philosophers, sociolinguists, sociologists, and anthropologists. The term embodies a range of meanings and interpretations advanced by the works of Bourdieu ( 1991 ), Foucault ( 1972 ), Hall ( 1997 ), and Said ( 1978 ), among others. It can be defined both as a function of language and in social terms. As a function of language, the concept can be conceived of as the representation of empirical experience and as the representation of thoughts. In social terms, it can be conceived of as the linking of mass-mediated practices and social norms to the representation of particular social groups and the construction of their identities, as well as the complex and relational depiction of the interests of political subjects or issues (the foundational principle of a representative democracy). Consequently, the study of representation calls on the analysis of language, including social structure and cultural practices to understand how meanings are...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Bourdieu, P. 1991 Language and Symbolic Power. Cambridge: Polity.

Google Scholar

Dann, G. 1996 The Language of Tourism: A Sociolinguistic Perspective. Oxford: CABI.

Foucault, M. 1972 The Archaeology of Knowledge. New York: Pantheon.

Hall, S. 1997 Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. London: Sage.

Morgan, N., and A. Pritchard 1998 Tourism Promotion and Power: Creating Images, Creating Identities. Chichester: Wiley.

Spivak, G. 1988 Can the Subaltern Speak. In Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, C. Nelson and L. Grossberg, eds., pp.271-313. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Said, E. 1978 Orientalism. New York: Patheon.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Recreation, Sport and Tourism, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 601 E John Street, 61820, Champaign, IL, USA

Carla A. Santos & Erin McKenna

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Carla A. Santos .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

University of Wisconsin-Stout, Menomonie, USA

Jafar Jafari

The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China

Honggen Xiao

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg (outside the USA)

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Santos, C.A., McKenna, E. (2016). Representation, cultural. In: Jafari, J., Xiao, H. (eds) Encyclopedia of Tourism. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01384-8_159

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01384-8_159

Published : 25 June 2016

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-01383-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-01384-8

eBook Packages : Business and Management Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

22 Social Representations As Anthropology of Culture

Ivana Marková, Department of Psychology, University of Stirling, Stirling, Scotland, UK

- Published: 21 November 2012

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The Theory of Social Representations studies formation and transformation of meanings, knowledge, beliefs, and actions of complex social phenomena like democracy, human rights, or mental illness, in and through communication and culture. This chapter examines the nature of interdependence between social representing, communication, and culture. It first explains differences between mental, collective, and social representations with respect to culture and language. It then focuses on two meanings of social representing: first, on representations as a theory of social knowledge and second, representations as social and cultural phenomena and as interventions in social practices. Rationality of social representations is based on diverse modalities of knowing and believing shared by groups and communities; it is derived from historically and culturally established common sense. This perspective justifies the claim that social representations should be treated as anthropology of contemporary culture. Finally, the chapter discusses main concepts linking social representations, language, and culture.

In this chapter we explore interdependencies between social representing, language, communication, and culture. In contrast to individual representations, social representations are dynamic phenomena that are embedded in culture and formed and transformed in and through language and communication. The researchers of social representing aim to understand how citizens think, feel about, and act on phenomena that are in the center of societal, group, and individual interests and discourses, be they political, health-related, environmental, or otherwise. Such phenomena pose significant challenges for social psychology generally and social representing specifically. Their understanding cannot be fitted within narrow and static frameworks, which still dominate large parts of social sciences. Instead, the study of social phenomena requires researchers’ and practitioners’ creativity in broadening and deepening the scope of their disciplines. This involves a scholarly interest in the ways in which traditions and novel ideas enrich each other, in the ability to understand how the relatively stable and new phenomena struggle for dominance and transform one another and how these tensions and conflicts are reflected in thought and language. The Theory of Social Representations, we shall argue here, provides researchers and practitioners with the means of coping with such challenges and so ensures the credibility of social psychology as a scientific discipline.

Because the concepts of “representation” and “representing” are used in different fields of social sciences and psychology, the study of social representing must dispel confusions between social and individual representations, the problem or rationality and irrationality, and misunderstandings of meanings of concepts linking social representing with cultural anthropology. Such issues also pose challenges for social psychology as a social scientific discipline: Can we make it theoretically convincing and useful in practical interventions?

Representation and Culture

During its long history in European scholarship, the meaning of representation has undergone considerable changes and diversification. Today, there are three main meanings of representation in human and social sciences and in philosophy. They stem from diverse epistemological traditions, address different levels of analysis, and imply contrasting relations with respect to culture and language.

Mental Representation, Culture, and Language

The first meaning refers to mental representations. It has been associated, at least since the seventeenth century with philosophers René Descartes and John Locke, with glorification of the cognition of the individual and with mirroring of the objective reality. According to this tradition, the self's cognition is the only source of certain knowledge or representation of reality.