An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.85(4); 2007 Dec

Knowledge Transfer and Exchange: Review and Synthesis of the Literature

Knowledge transfer and exchange (KTE) is as an interactive process involving the interchange of knowledge between research users and researcher producers. Despite many strategies for KTE, it is not clear which ones should be used in which contexts. This article is a review and synthesis of the KTE literature on health care policy. The review examined and summarized KTE's current evidence base for KTE. It found that about 20 percent of the studies reported on a real-world application of a KTE strategy, and fewer had been formally evaluated. At this time there is an inadequate evidence base for doing “evidence-based” KTE for health policy decision making. Either KTE must be reconceptualized, or strategies must be evaluated more rigorously to produce a richer evidence base for future activity.

Knowledge transfer and exchange (KTE) is an interactive interchange of knowledge between research users and researcher producers ( Kiefer et al. 2005 ). The primary purposes of KTE are to increase the likelihood that research evidence will be used in policy and practice decisions and to enable researchers to identify practice and policy-relevant research questions. Even though there are many strategies for KTE, it currently is not clear which ones should be used in which contexts ( Lavis et al. 2003a ). To date, the complete literature on KTE as it pertains to health policy has not been reviewed in a single study. One reason is the challenges in adequately defining KTE across different literatures that tend to use varying terminology in articulating the underlying concept of information and evidence exchange between researchers and health policy decision makers. Accordingly, no summary of the current evidence regarding KTE strategy effectiveness in relation to health policy is available.

Our review was the first part of a larger study designed to find evidence-based KTE practices to inform the design of a specific KTE platform for a series of research projects referred to collectively as the “Alberta Depression Initiative” (ADI). This article reports on the review's findings. Another, separate article reports on the findings of a series of key informant interviews on KTE issues relevant to the ADI research program and also outlines the implications of both the review and interview findings for KTE in research programs like the ADI.

With the growing demands on health care resources and a general culture of accountability, greater emphasis is being placed on generating knowledge that can have a practical impact on the health system ( Lomas 1997 ). To this end, “knowledge transfer” emerged in the 1990s as a process by which research messages were “pushed” by the producers of research to the users of research ( Lavis et al. 2003b ). More recently, “knowledge exchange” emerged as a result of growing evidence that the successful uptake of knowledge requires more than one-way communication, instead requiring genuine interaction among researchers, decision makers, and other stakeholders ( Lavis et al. 2003b ).

While the value of and need for KTE has received wide support, both researchers and decision makers also acknowledge that they are driven by demands that may not be conducive to successful KTE. For researchers, these demands include challenges such as adapting the research cycle to fit real-world timelines, establishing relationships with decision makers, and justifying activities that fit poorly with traditional academic performance expectations ( CHSRF 1999 ). A perceived lack of knowledge of the research process, the traditional academic format of communication, research that is not relevant to practice-based issues, and a lack of timely results are often cited by those charged with making policy decisions as being barriers to using research findings ( CHSRF 1999 ). Both parties also frequently lament the lack of time and resources to participate in KTE.

Noting these challenges, a variety of mechanisms to facilitate KTE have been proposed, such as joint researcher–decision maker workshops, the inclusion of decision makers in the research process as part of interdisciplinary research teams, a collaborative definition of research questions, and the use of intermediaries that understand both roles known as “knowledge brokers” ( CHSRF 1999 ). In addition, interpersonal contact between researchers and decision makers is an oft-cited fundamental ingredient in successful KTE initiatives ( Thompson, Estabrooks, and Degner 2006 ). To date, however, “gold standard” approaches to KTE seem to be based, at best, on anecdotal evidence but mostly on experience and even rhetoric rather than on rigorous evidence. Our primary aim for this review was to examine and summarize the current evidence base for KTE in relation to health policy, resulting in an evidence-based resource for planning KTE processes.

We based our review on adaptations of systematic review methods used commonly for clinical research questions. In our case, we used a review process to address questions at the health policy level. Our methods were intended to be transparent, to include appraisal and validation steps in accordance with the principle of replicability but also to involve comparative and thematic synthesis rather than quantitative analysis, and to use gray literature sources to illuminate contextual issues identified from peer-reviewed studies ( Adair et al. 2006 ; Lavis et al. 2004 ).

Our literature review had four steps: (1) searching for abstracts, (2) selecting articles for inclusion through a relevancy rating process, (3) classifying and rating the selected articles, and (4) synthesizing and validating them. The steps of the review are shown in appendix A . Our initial goals were to ensure a broad capture of a relatively new and poorly defined field and then to identify a final set of the highest-quality and most relevant articles through a consensus screening of abstracts and a selection of articles.

The principal investigator and a medical research librarian developed and ran the search strategy in January 2006. They searched eight databases for English-language abstracts from 1997 to 2005: Medline, EMBASE, Cinahl, PsycINFO, EconLit, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, sociological abstracts, and social sciences abstracts. The gray literature also was reviewed, including the University of York HTA database, University of Laval KUUC database, New York Academy of Medicine Gray Literature Reports, and ABI Inform (ProQuest dissertations and theses).

We then reviewed reference lists in the identified papers and reports, as well as publication lists of international research centers and researchers known to us to have an interest in KTE. The primary search terms looked for were (the following and variations of) knowledge generation, knowledge translation, knowledge transfer, knowledge uptake, knowledge exchange, knowledge broker, and knowledge mobilization. We also used substitutes for knowledge, such as evidence, information, and data. Our focus in the review was on studies of KTE that could have either an impact on or implications for health care policies at an organizational, regional, provincial, and/or federal level. We attempted to keep the diffusion of innovation literature separate (e.g., Greenhalgh et al. 2004 ; Rogers 1995 ), although of course in some cases, the two literatures overlapped. Our strategy also resulted in some but not extensive overlap with “implementation research,” which has as its focus the set of activities created to carry out a given program (e.g., Fixsen et al. 2005 ). In this sense, the KTE literature can be viewed as a subset of a more broadly defined notion of implementation research that includes activities with practitioners, consumers, and policymakers but also has a greater focus on “transfer” then on information “exchange.”

The initial search yielded 4,250 abstracts. The research team drafted a relevancy criteria statement, tested it on a subset of one hundred abstracts, and discussed with the reviewers the differences in interpretation. They reached a high level of agreement (kappa = 0.78), indicating both clarity and consistency in the researchers' understanding. They talked about the discrepancies and settled on a final relevancy definition that they applied to the abstracts. The team's operational definition was “research conducting/implementing KTE and evaluating KTE between researchers and policy and decision makers.” We specifically excluded publications reflecting exchanges between researchers and clinicians, between providers, or between providers and consumers. One research team member screened the remainder of the identified abstracts and retrieved 150 full articles. A subsequent review of reference lists and KTE websites and research centers found an additional nineteen peer-reviewed articles.

We reviewed these 169 papers and assessed their relevancy, resulting in eighty-one studies that we sorted into implementation studies (i.e., the implementation of specific KTE strategies or evaluations of KTE approaches, n = 18) and nonimplementation papers and reports (i.e., reviews, commentaries, and surveys of relevant stakeholders pertaining to KTE but not reporting on implementation of an actual KTE strategy, n = 63). We then gave these studies a quality rating, using a fifteen-point scale for implementation studies that separately assessed the quality of the literature review, research design, data collection, analysis, and reporting of results, and a ten-point scale for the nonimplementation papers that qualitatively assessed the fit of the paper into the context of the literature, including the date of the paper, journal, and evidence of critical thought (see appendix B ). Two members of the team rated a subset of articles ( n = 20), resulting in a high level of agreement (kappa = 0.78). Discrepancies were discussed, and a consensus was reached in all cases. One member of the research team then rated the remaining papers. In order to limit the pool of studies to those perceived to be of higher quality, we had decided earlier to include only those studies that had an overall score higher than 7/10 or 10/15 on the respective rating scale. The first two subsections of the results focuses on these “higher-rated” studies.

After this, we identified a number of relevant, nonduplicative reports from the gray literature following the preceding strategies, noting that we continued to review all relevant gray literature reports until spring 2007. These reports were not formally rated as the peer-reviewed literature was, and we used them solely to supplement information that did not appear elsewhere. As such, we included information that in our view was (1) a novel addition to the peer-reviewed literature and (2) made a substantial contribution to the knowledge base of KTE as a whole. Key messages from these reports are outlined in the third section of the results.

As indicated, of the eighty-one papers that were quality rated, sixty-three were classified as nonimplementation studies. That is, they were opinion pieces, reviews, or surveys of stakeholders concerning KTE issues. Conversely, slightly more than 20 percent ( n = 18) of the studies reported on a real-world application of a KTE strategy. About 70 percent ( n = 56 of 81) were published from 2003 to 2005, with the remaining ( n = 25) published from 1997 to 2002, suggesting that the field is growing in interest and importance. Overall, thirty-four (of 63) nonimplementation studies were scored 7/10 or greater, and ten (of 18) implementation studies were scored 10/15 or better. Of these “higher-rated” articles ( n = 44), the lead author was located in Canada in 55 percent ( n = 25 of 44) of the studies. The study originated from the United Kingdom or Europe in 23 percent ( n = 10 of 44) of the cases, while 11 percent ( n = 5 of 44) were from the United States, and four studies were from elsewhere. Four reports were identified in the gray literature that, in our view, provide substantial additional information about or insight into KTE. The remaining sections of this article are based on these forty-eight studies or reports, that is, thirty-four of sixty-three nonimplementation studies, ten of eighteen implementation studies, and four gray literature reports.

We also should note the influence of the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation (CHSRF) on our review. Over the last decade, CHSRF has promulgated the use of the terms knowledge transfer and knowledge transfer and exchange . This use, paralleled by many prominent Canadian researchers, some with links to the CHSRF, has resulted in a preponderance of KTE-labeled papers in Canada. As such, on one level, the CHSRF's “marketing” of KTE evidently has been remarkably effective. On another level, however, as is described in the following sections in some detail, without an evaluation of KTE, the CHSRF's efforts may have been premature.

Nonimplementation Studies

The nonimplementation literature identified four major themes: (1) organizing frameworks for applying KTE strategies, (2) barriers and facilitators to KTE, (3) methods and issues for measuring the impact of research studies, and (4) perspectives from different stakeholder groups on what works and what does not work with respect to KTE. These themes were identified on the basis of the highest frequency of appearance in the literature as well as, in our view, the greatest importance for making decisions about the development of KTE strategies and how best to implement them.

Organizing Frameworks for Applying KTE Strategies

We chose five frameworks that had been developed to guide KTE initiatives, which are summarized in table 1 . Dobbins and colleagues (2002) proposed a framework that uses Rogers's Diffusion of Innovations theory (1995) to illustrate the adoption of research into clinical and policy decision making. In a review of the use of research in policymaking, Hanney and colleagues (2003) explored the factors enhancing this use, emphasizing the importance of actions at the interfaces between research producers and users while at the same time highlighting the relevance of “receptor capacity.” Such interaction should occur at various stages in the research process, for example, setting priorities, commissioning research, and communicating findings. Ebener and colleagues (2006) proposed using a knowledge map, or visual association of items, that includes both the knowledge type (i.e., what, how, why, where, and who) and the recipient (i.e., individual, group, organization, or network). This information is similar to components in Lavis and colleagues' (2003a) framework, which recommends five elements to consider when organizing KTE: message, target audience, messenger, knowledge transfer process and support system, and evaluation strategy. In regard to the fifth step, an objective for policymakers would be to inform debate, which is often more realistic than the objective to change decision-making outcomes. Finally, Jacobson, Butterill, and Goering (2003) developed a framework to increase researchers' familiarity with the intended user groups and context.

Organizing Frameworks for KTE Application

Barriers and Facilitators

The barriers and facilitators for KTE are well recognized as a result of dozens of studies and perhaps are the most frequently addressed topic area in the KTE literature on health policy decision making. These factors can be classified on individual and organizational levels and pertain to relationships between researchers and decision makers, modes of communication, time and timing, and context. Table 2 summarizes these factors. Owing to the attention paid to them in the literature, we discuss a number of the studies and concepts here in more detail.

Main KTE Barriers and Facilitators

In Norway, Innvaer and colleagues (2002) systematically reviewed twenty-four surveys of facilitators and barriers to the use of research evidence by health policymakers. The most frequently reported facilitators were personal contact between researchers and policymakers, clear summaries of findings with recommendations for action, good-quality research, and research that included effectiveness data. Other studies have also supported the use of face-to-face encounters as being key to KTE ( Greer 1988 ; Jacobson, Butterill, and Goering 2003 ; Lomas 2000a ; Roos and Shapiro 1999 ; Soumerai and Avorn 1990 ; Stocking 1985 ).

In a participatory evaluation of Manitoba's The Need to Know project, Bowen, Martens, and the Manitoba Need to Know Team (2005) interviewed community partners to identify the characteristics of effective KTE and found that the most important factors were based on relationships. The quality of relationships and the trust developed between the research partners were critical components. The mutual mistrust between policymakers and researchers has been noted elsewhere as a barrier to the use of research ( Choi et al. 2005 ; Trostle, Bronfman, and Langer 1999 ).

In their examination of pharmaceutical policymaking, Willison and MacLeod (1999) suggested that to improve the use of research, researchers must first decide who their audience is. Similar to what Lavis and colleagues (2003a) recommended, Willison and MacLeod emphasized that each audience has different information needs and communication styles and therefore the information must be appropriately tailored. Research should be presented in summary format, in simple language, and with clearly worded recommendations ( Reimer, Sawka, and James 2005 ; Willison and MacLeod 1999 ). Acceptable evidence for decision makers can be less rigorous than that for researchers and includes gray literature (i.e., government publications, consultants' reports, monographs, and conference proceedings) ( Hennink and Stephenson 2005 ; Weatherly, Drummond, and Smith 2002 ). One study noted that decision makers persistently valued experience more than they did research ( Trostle, Bronfman, and Langer 1999 ).

Another frequently recommended facilitator is the inclusion of key individuals, either decision makers or opinion leaders, in the research planning and design stages ( DeRoeck 2004 ; Lomas 2000b ; Ross et al. 2003 ; Vingilis et al. 2003 ; Whitehead et al. 2004 ; Willison and MacLeod 1999 ). Timeliness and the relevance of research also are important ( Dobbins et al. 2001 ; Frenk 1992 ; Hemsley-Brown 2004 ; Hennink and Stephenson 2005 ; Jacobson, Butterill, and Goering 2004 ; Mubyazi and Gonzalez-Block 2005 ; Stewart et al. 2005 ; Trostle, Bronfman, and Langer 1999 ). Since researchers tend to have longer time horizons than decision makers do, Willison and Macleod (1999) suggested that shorter-term objectives be included to address policymakers' needs. British researchers noted the potential for a “sleeper effect,” in which evidence is stored and not used until a more encouraging political climate develops ( Whitehead et al. 2004 ). Similarly, Martens and Roos (2005) referred to the importance of keeping information on hand until a favorable context prevails, a notion also alluded to by Roos and Shapiro (1999) regarding research on the use of prenatal care and the delivery of mental health services in Manitoba.

Bogenschneider and colleagues (2003) suggested that seminar series with different stakeholder groups be used to facilitate the exchange. The EUR–ASSESS project concluded that personal contact with policy staff was more effective than printed material ( Granados et al. 1997 ). This conclusion coincided with reviews by Grimshaw, Eccles, and Tetroe (2004) and Grimshaw and colleagues (2001) , which examined interventions used to influence the uptake of knowledge to change clinical practice. Educational outreach visits and interactive meetings were generally effective, and printed material and didactic meetings were the least effective. Although these reviews reveal important dissemination activities, on the surface there appears to be limited evidence regarding specifically how strategies should be applied to different stakeholder groups.

Although systematic reviews can inform policymaking ( Dobbins et al. 2001 ; Lavis et al. 2004 ; Lavis et al. 2006 ), it also is clear that factors aside from “evidence” (as traditionally defined by researchers) affect decision making. Evidence seldom has a rationally linear impact, given the complexity of the decision-making context ( Whiteford 2001 ). For example, both Frenk (1992) and Lomas (2000b) noted the importance of formal and informal institutional structures for decision making. This can include the distribution of responsibility and accountability as well as the roles of interest groups and policy networks in determining what information will be used according to particular values.

The researcher incentive system in universities also has been cited as a barrier. Fraser (2004) commented that the current professional incentive system (i.e., including publishing in peer-reviewed journals and acquiring grants for academic, as opposed to applied or translational research) is “diametrically opposed” to the needs of potential research users. Researchers, of course, are acutely aware of this challenge and may find themselves asking, with no clear answer, Whose responsibility is KTE? and Who will fund these KTE activities?

Waddell and colleagues (2005) examined the use of research in the context of competing influences on the Canadian policy process. Although policymakers used and valued research evidence, they also described three prevailing influences on the policy process that Waddell and colleagues termed inherent ambiguity , institutional constraints , and competing interests . When describing the process of policymaking, one interviewee commented that “facts and logic aren't deciding factors given that decision makers are faced with an immense amount of competing information on an immense range of subjects.” Institutional constraints include fragmentation across state and local levels of government, as well as across the health, education, social service, and justice sectors.

One recently proposed mechanism to facilitate KTE between researchers and decision makers is a knowledge broker, who is trained specifically in information exchange and has set aside time for the process. Vingilis and colleagues (2003) used the term connector to refer to people who help potential knowledge users determine their knowledge needs and help researchers translate, influence, and initiate KTE. Research on the use of knowledge brokers has been limited, however, and has prompted calls to examine the costs and benefits of this KTE strategy ( Pyra 2003 ) and also the quality of information resulting from knowledge broker–based KTE initiatives ( CHSRF 2000 ).

Finally, the use of health services research in policymaking may be enhanced by a government culture that nurtures an interest in and the value of research ( Bowen, Martens, and the Manitoba Need to Know Team 2005 ; Hennink and Stephenson 2005 ; Roos and Shapiro 1999 ; Whitehead et al. 2004 ).

Learning organizations move beyond employee training into organizational problem solving, innovation, and learning ( Stinson, Pearson, and Lucas 2006 ). This means graduating from simply updating a few practices or implementing initiatives to changing the organization's culture to instill the value of mutual learning ( Dowd 1999 ).

Measuring the Impact of the Research

Research organizations and funders are increasingly recognizing the importance of measuring the impact of health research on policies and practices. Documentary analysis, in-depth interviews, and questionnaires have been used to assess the impacts and outcomes of research knowledge. Several researchers have attempted to measure or score the impact of research on the development of public policy. In an exploratory study examining the role of health services research in Canadian provincial policymaking, Lavis and colleagues (2002) interviewed policymakers in Ontario and Saskatchewan. These interviews highlighted three avenues to the use of citable research: (1) the policymakers read printed material; (2) the policymakers interacted with the researchers; and (3) the researchers were involved with the working groups.

Landry, Amara, and Lamari (2001) looked at the use of social science research by interviewing Canadian university faculty members. They defined the use of research as a six-stage cumulative process from transmission to application, with intermediate stages of cognition, reference, adoption, and influence. Nearly half the respondents indicated that they transmitted findings to practitioners, professionals, and decision makers. However, when moving through the six stages, there was a marked increase in research findings rarely or never used. The most important determinants of utilization were the mechanisms linking researchers to users and the users' context. Knowledge utilization depended more heavily on factors regarding the behavior of the researchers and the users' context, or receptive capacity, than on attributes of the research products themselves ( Landry, Amara, and Lamari 2001 ).

Lavis and colleagues (2003b) devised an assessment tool for funders and research organizations to measure the impact of research. They described the following stages: (1) identify target audiences for research knowledge, (2) select appropriate categories of measures (e.g., producer–push, user–pull, or exchange measures), (3) select measures given resources and constraints, and (4) identify the data sources and/or collect new data, analyzing whether and, if so, how research knowledge was used in decision making. They recommended intermediate outcome measures such as whether a policy changed if resources were available to conduct case studies determining whether knowledge was used in the context of competing influences on decision-making processes.

In relation to this last point, examining how knowledge is used moves beyond whether it was used. Almost three decades ago, research knowledge was identified as being used in one of three ways: instrumental , conceptual , or symbolic ( Weiss 1979 ). An instrumental use is research knowledge that directly shapes policies and results in action; a conceptual use refers to a change in awareness or understanding of certain issues; and a symbolic use merely legitimizes existing policies or positions.

Finally, von Lengerke et al. (2004) suggested that health promotion policy using public health research is associated with the policy's impact if both strong social strategies and the political will to support a given policy are present at the same time. To test this assumption, they analyzed data from a survey of policymakers concerning four prevention and health promotion policies in six European countries. These authors found that research use was positively associated with policy output (i.e., the implementation of programs) and outcome (i.e., effectiveness) in contexts in which political interference was minimal.

Stakeholders' Perspectives

The fourth main theme identified in the nonimplementation studies has to do with perspectives on the relationship between KTE stakeholders and the potential effectiveness of KTE strategies. Table 3 outlines six studies from our review and the perspectives offered. While some of the key points raised can be found elsewhere in the KTE literature (e.g., the importance of relationship building and rapport between the researcher and decision maker), the main issue here is that different stakeholders across different contexts came to similar conclusions.

Stakeholders' Perspectives on KTE Relationships

Implementation Studies

Our review identified eighteen studies in which a specific KTE mechanism was employed or implemented, and ten of these were rated at 10/15 or higher on our quality index. As table 4 shows, there are numerous approaches to KTE. The focus of many of these interventions is on generating two-way communication, which is not surprising given the emphasis on this in the nonimplementation literature. The notion of a phased intervention to build relationships followed by facilitated meetings also arose.

Key KTE Strategies Identified in the Literature

The ten implementation studies synthesized here varied in topic area and context: five focused on health promotion and prevention; two looked at workplace health safety; and the remaining three involved mental health, child health, and cancer pain management, respectively (see table 5 ). The message communicators included researchers, decision makers, and knowledge brokers, and three studies did not specify the communicator. In all these studies, the amount of information available to assess the given KTE strategy varied widely.

Summary of KTE Implementation Studies Identified in the Literature

For example, some studies used more rigorous designs and/or based their assessment on predefined outcome measures. Kothari, Birch, and Charles (2005) used a quasi-experimental study design (i.e., one that had a comparison group) and qualitative methods in determining whether the uptake of information contained in a research report hinged on being involved in developing the report itself. Outcomes measured were the decision maker's understanding of the analysis and intent to use the research findings. Their findings suggested that in the study's time frame, interaction with the report was not associated with the decision makers' greater use. Kramer and Cole's (2003) multiple-case study applied qualitative methods to determine the impact of KTE based on a set of predefined outcome measures. In this study, the mode of communication was a plain-language booklet entitled the “Participative Ergonomic Blueprint.” The “Blueprint” is a facilitator's guide to implementing a successful participative ergonomics program as part of an employer's health and safety program. Finally, the work by Robinson and colleagues (2005) also included a wide range of outcome measures. The challenge here is that the use of multiple linking activities and outcomes makes it difficult for the reader to discern the individual impact of any one KTE strategy. The remaining studies were a mix of posttest studies, case studies, and case reports offering varying levels of evidence with respect to the strategy's effectiveness.

These studies also examined the presence of a formal, planned evaluation of the KTE strategy. From the information reported in these ten studies, only five seemed to have intended to formally evaluate their KTE strategies in advance, and an even smaller set ( n = 3), as alluded to earlier, had clearly defined outcome measures. It is also notable that not a single randomized controlled study of KTE was identified. While some studies reported observations of or reflections on the impact of the KTE strategy, generally these observations were not based on a formal evaluation including a research study design with already identified outcome measures. Of course, the intent of these studies was not necessarily to evaluate the KTE activity; in most cases, the emphasis was on the description of the transfer and exchange of information itself. However, owing to the lack of rigorous evaluation, there is little foundation for transferring findings from these studies to other or even similar contexts.

In short, based on these studies, we did not find an “off the shelf” set of recommendations for developing and implementing KTE strategies. This difficulty is due in part to the relatively small number of implementation studies across fields in health care and also to the even less formal and/or rigorous evaluation of these strategies.

Gray Literature

We included the gray literature in this review to supplement our findings from the peer-reviewed papers. We decided that four reports made a significant contribution to the literature being studied, and they are summarized in table 6 . The fourth report listed is particularly important, as it is the only study in our entire review that used a randomized control trial (RCT) design to assess KTE strategies. 1 Dobbins and colleagues (2007) conducted an RCT to test the effectiveness of KTE strategies in Canadian public health decision making on programs related to the promotion of physical activity and healthy body weight in children. The three progressively more active interventions were access to an online registry of systematic reviews evaluating public health interventions, targeted evidence messages, and knowledge brokering. The targeted messaging was significantly more effective in promoting evidence-informed decision making compared with the website and knowledge-brokering groups. The extent to which decision makers in public health organizations valued research evidence affected the knowledge-brokering activity. Knowledge brokering was more effective in those organizations that placed less value on research evidence and was less effective in those organizations that already recognized the importance of evidence-based decision making.

Summary of Gray Literature Reports

Note: a This study was presented at a conference but not yet published at the time of the review; and it was identified after the initial search.

The bulk of the literature on KTE in regard to health policy pertains to barriers and facilitators to implementation, as well as frameworks that can be used to organize and design KTE strategies, perspectives of KTE from various stakeholder groups, and ways to measure the impact of research on health policy. A smaller subset of the literature pertains to the implementation of KTE strategies for health policy decision making. Overall, these studies have undergone only limited evaluation, and for those that have been evaluated, generalizing findings to other contexts is extremely difficult.

Some of the key messages in the nonimplementation papers, which clearly reiterate Innvaer and colleagues' (2002) findings, are the importance of having personal contacts and building trust through quality relationships over time, in order to have a genuine exchange of information that results in some form of change. It also is clear that no one size fits all, with specific messages needing to be tailored to each audience. That said, what is not as clear from the literature is what works in what contexts and even where the responsibility for KTE rests. In addition, important advances have been made in measuring the impact of research ( Allen Consulting Group 2005 ; Kuruvilla et al. 2006 ). As a recent report from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research ( CIHR 2005 ) pointed out, indicators of the effect of health research are building capacity for training, informing policy, offering health benefits such as life expectancy and quality of life, and providing key economic benefits such as workplace productivity. This broader view of outcomes fits nicely with the perspectives of understanding organizational change and policy development more broadly and, as discussed later, in examining this question by drawing on information across multiple disciplines ( Greenhalgh et al. 2004 ).

Combining these insights with those from the implementation studies, the major finding of this review is that despite the rhetoric and growing perception in health services research circles of the “value” of KTE, there is actually very little evidence that can adequately inform what KTE strategies work in what contexts. Of course, existing studies can provide insight into KTE activity, but in our view, with the current state of the literature, there is insufficient evidence for conducting “evidence-based” KTE for health policy decision making.

This conclusion may explain why researchers and research funders have recently produced informative papers based on years of experience with KTE (e.g., Lomas 2007 ). As most would likely acknowledge, this experience falls short, however, in meeting the criteria as research evidence. We do not mean to suggest that those in the KTE field do not have important insights; rather, we are drawing a parallel to how many health services researchers have been critical of clinicians for drawing conclusions from case series reports, particularly since the advent of the evidence-based medicine movement. Viewed in this light, one call from our findings is the need for the greater application of formal and rigorous research designs to assess and evaluate the success of KTE strategies in specific contexts. Reporting on aspects of KTE such as barriers and facilitators does reveal the relevant issues to those interested in an interchange between researchers and decision makers. But in the end, primary research on KTE itself would be required in order to produce the evidence necessary to decide how best to allocate dedicated KTE resources.

Another of our findings is that KTE, at least as conceptualized to date, simply does not fit with the underlying politics of health policymaking. That is, noting limited rigorous implementation and evaluation of KTE strategies at the policy level, could it be that the concept of KTE in this context has been inappropriately transferred from clinical decision making? For the positivist, cause-and-effect translates in this context into knowledge that is transferred between researcher and decision maker in order to influence change. Of course, many scholars have recognized the many factors resulting in a particular action at the policy level (e.g., Mitton and Patten 2004 ; Whiteford 2001 ) and, indeed, the importance of context in knowledge utilization ( Dobrow et al. 2006 ). But more fundamentally, as Lewis (2007) pointed out, evidence-based decision making has not had the intended effect due to a myriad of reasons, not the least of which is that decisions at the policy level do not fit into neat little boxes that can be informed by technically oriented inputs. As such, it is important to ask whether those on the “KTE path” will ever be able to make significant strides forward. One may argue that KTE strategies need to be evaluated and refined, but the complexities of real-world policymaking and the misalignment between the evidence producers and the decision makers suggest that other literatures and disciplines, and indeed, other ways of thinking need to be given greater weight in these discussions.

Noting these arguments, introducing an evaluation component into KTE exercises, as has been called for elsewhere ( Pyra 2003 ), should be even more important, as it is not only the refinement but, perhaps more fundamentally, the justification of KTE that may be required. For example, it may be more beneficial to conduct an evaluation based on whether and how policy was informed, rather than simply the extent to which research was used ( Eager et al. 2003 ; Lavis et al. 2003a ). If there is to be a demonstrable impact, researchers must learn about the challenges and environment in which decision makers operate and determine how to present the information in a manner appropriate to the real-world environment ( Aaserud et al. 2005 ). But if there is consistently “no impact” through rigorous KTE endeavors across different contexts, it may be that KTE should not continue to be pursued. At this point, we do know, as stated by Lavis and colleagues (2003a, p. 240) in their survey of research organizations mentioned earlier, that “the directors [in funding organizations] were remarkably frank about not evaluating their knowledge transfer activities.”

If KTE activities continue to be pursued, then one way to conceptualize development, implementation, and evaluation is to consider what is under the control of the researchers and what falls under the influence of the policymakers. While this may magnify the perceived gap between these two main stakeholder groups, it can also serve to highlight which aspects of KTE should receive research grant funding and which contextual factors need to be addressed to the decision maker receiving the information. Similarly, much more effort is needed to articulate how knowledge is best transferred from decision makers to researchers and who is responsible for ensuring that this interaction and ultimate exchange takes place. With limited time and the ever-increasing demands on both groups, it is difficult to justify expending resources on ineffective strategies that ultimately are outside the control of either or both parties.

In our view, funding bodies can play a major role here, not only in requiring that detailed KTE plans be incorporated into research grants, but also in funding innovative fellowships such as residency placements in academic and health service delivery organizations and in funding more primary research on the evaluation of specific KTE strategies. On this last point, funders should support more rigorous study designs of KTE strategies, perhaps as a component of larger programs of research that include multiple studies with subsequent designs building directly on previous work. On the other hand, as Greenhalgh and colleagues (2004) point out, controlling for potential confounders in organizational and systems-level research may not be the most prudent way forward. While our study does not speak directly to this debate, we do suggest that at a minimum funders consider allocating resources to KTE endeavors as a pursuit in itself rather than as an “add-on,” as is so often the case at present.

Our review has several limitations. First, our method of including and excluding studies in our review could be criticized. Agreement on inclusion is not the same as the “worthiness” of scientific endeavor but rather merely suggests that individual research team members agree that a given paper “fits” with a relevancy statement outlined for the review. Furthermore, we based our synthesis on studies that, in our view, were of higher quality, but again, we relied on our own values in these judgments. Similarly, the search terms we selected likely reflect our understanding of the topic and our own biases. The fact that more than half the articles retrieved were by Canadian authors may suggest that we have brought a specific lens to this review that excluded other important and related works. Nonetheless, the review was intended to describe how KTE and closely related concepts are currently used, and it did not investigate broader notions such as knowledge diffusion, implementation research, or policy decision making. Nor was our intent to summarize the evolution of related theory. Thus we would argue that the review did address the field of KTE but does not suggest that others who label their work differently have not made important contributions.

Although KTE is not a new concept, it seems to be growing more important. Nonetheless, KTE as a field of research is still in its infancy. It is not hard to find opinion pieces and anecdotal reports about how to use KTE, but the limited reporting of KTE implementation and the even more limited formal evaluation of it leave those wanting to develop their own KTE efforts at a loss for evidence-based strategies. Relationships and institutional knowledge are clearly important themes, as is quality interaction with a few individuals, as opposed to a mass barrage of information to many. Even though no one size fits all, what is needed is more work to inform the application of KTE strategies across contexts to enable evidence-based practice. In our view, the only way to reach this is to conduct primary research on KTE, rather then seeing KTE as an “add-on” to other projects.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Alberta Depression Initiative, which is sponsored by the Government of Alberta (Alberta Health and Wellness) and administered by the Institute of Health Economics. Craig Mitton holds funding from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research and the Canada Research Chairs program. Scott Patten is a health scholar with the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research, and a fellow with the Institute of Health Economics. We are grateful for the assistance of Ms. Diane Lorenzetti, University of Calgary, in helping to develop and run the literature searches. We would also like to thank the editor and three reviewers for their insightful comments.

Steps in Literature Review

Quality Rating Sheets

Ref ID: ________

KTE Empirical Article Quality Rating Sheet

0 – not present or reported anywhere in the article

1 – present but low quality

2 – present and midrange quality

3 – present and high quality

________ 1. Literature Review: Directly related recent literature is reviewed and research gap(s) identified.

________ 2. Research Questions and Design: A priori research questions are stated, and hypotheses, a research purpose statement, and/or a general line of inquiry is outlined. A study design or research approach is articulated.

________ 3. Population and Sampling: The setting, target population, participants, and approach to sampling are outlined in detail.

________ 4. Data Collection and Capture: Key concepts/measures/variables are defined. A systematic approach to data collection is reported. Response or participation rate and/or completeness of information capture is reported.

________ 5. Analysis and Results Reporting: An approach to analysis and a plan to carry out that analysis is specified. Results are clear and comprehensive. Conclusions follow logically from findings.

________ /15 = Total Score

Ref ID: ________ KTE Nomempirical Article Quality Rating Sheet

Source: Adapted from Adair et al. 2006 .

1 Note that this study was not included in the implementation study section, as it was not found in the peer-reviewed literature at the time of our study.

- Aaserud M, Lewin S, Innvaer S, Paulsen E, Dehlgren A, Trommald M, Duley L, Zwarenstein M, Oxman A. Translating Research into Policy and Practice in Developing Countries: A Case Study of Magnesium Sulphate for Pre-eclampsia. BMC Health Services Research. 2005; 5 (68) [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Adair CE, Simpson L, Casebeer A, Birdsell J, Hayden K, Lewis S. Performance Measurement in Healthcare—Part I: Concepts and Trends from a State of the Science Review. Healthcare Policy. 2006; 1 (4):85–104. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Allen Consulting Group. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2005. Measuring the Impact of Publicly Funded Research. Report to the Australian Government Department of Education, Science and Training. [ Google Scholar ]

- Birdsell J, Thornley R, Landry R, Estabrooks C, Mayan M. Edmonton, Alberta: Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research; 2006. The Utilization of Health Research Results in Alberta. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bogenschneider K, Olsen JR, Linney KD, Mills J. Connecting Research and Policymaking: Implications for Theory and Practice from the Family Impact Seminars. Family Relations. 2003; 49 :327–39. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bowen S, Martens P Manitoba Need to Know Team. Demystifying Knowledge Translation: Learning from the Community. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. 2005; 10 (4):203–11. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Canadian Health Services Research Foundation (CHSRF) Issues in Linkage and Exchange between Researchers and Decision-Makers: Summary of workshop convened by CHSRF. 1999. May.

- Canadian Health Services Research Foundation (CHSRF) Health Services Research and … Evidence-Based Decision-Making. 2000. [accessed April 29, 2006]. Available at, http://www.chsrf.ca/knowledge_transfer/pdf/EBDM_e.pdf .

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Developing a CIHR Framework to Measure the Impact of Health Research. 2005. [accessed October 22, 2007]. Available at, http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/documents/meeting_synthesis_e.pdf .

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Ottawa: 2006. Evidence in Action, Acting on Evidence. A Casebook of Health Services and Policy Research Knowledge Translation Stories. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada. [ Google Scholar ]

- Choi B, Pang T, Lin V, Puska P, Sherman G, Goddard M, Ackland M, Sainsbury P, Stachenko S, Morrison H, Clottey C. Can Scientists and Policy Makers Work Together? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2005; 59 :632–37. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- DeRoeck D. The Importance of Engaging Policy-Makers at the Outset to Guide Research on and Introduction of Vaccines: The Use of Policy-Maker Surveys. Journal of Health Population Nutrition. 2004; 22 (3):322–30. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dobbins M, Cockerill R, Barnsley J, Ciliska D. Factors of the Innovation, Organization, Environment, and Individual That Predict the Influence That Five Systematic Reviews Had on Public Health Decisions. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care. 2001; 17 (4):467–78. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dobbins M, Ciliska D, Cockerill R, Barnsley J, DiCenso A. A Framework for the Dissemination and Utilization of Research for Healthcare Policy and Practice. Online Journal of Knowledge Synthesis for Nursing. 2002; 9 (7) [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dobbins M, DeCorby K, Robeson P, Cilisaka D, Thomas H, Hanna S, Manske S, Mercer S, O'Mara L, Cameron R. Ottawa: Canadian Cochrane Colloquium; 2007. The Power of Tailored Messaging: Preliminary Results from Canada's First Trial on Knowledge Brokering. February 12. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dobrow M, Goel V, Lemieux-Charles L, Black N. The Impact of Context on Evidence Utilization: A Framework for Expert Groups Developing Health Policy Recommendations. Social Science and Medicine. 2006; 63 :1811–24. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dowd JF. Learning Organizations: An Introduction. Managed Care Quarterly. 1999; 7 :43–50. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Eager K, Cromwell D, Owen A, Senior K, Gordon R, Green J. Health Services Research and Development in Practice: An Australian Experience. Journal of Health Services and Research Policy. 2003; 8 (S2):7–13. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ebener S, Khan A, Shademani R, Compernolle L, Beltran M, Lansang M, Lippman M. Knowledge Mapping as a Technique to Support Knowledge Translation. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2006; 84 (8):636–42. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, Friedman RM, Wallace F. Tampa: Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, National Implementation Research Network, University of South Florida; 2005. Implementation Research: A Synthesis of the Literature. FMHI Publication no. 231. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fraser I. Organizational Research with Impact: Working Backwards. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing. 2004; 1 (suppl.1):S52–S59. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Frenk J. Balancing Relevance and Excellence: Organizational Responses to Link Research with Decision-Making. Social Science and Medicine. 1992; 35 (11):1397–1404. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goering P, Butterill D, Jacobson N, Sturtevant D. Linkage and Exchange at the Organizational Level: A Model of Collaboration between Research and Policy. Journal of Health Services and Research Policy. 2003; 8 (S2):14–19. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Granados A, Jonsson E, Banta HD, Bero L, Bonair A, Cochet C. EUR–ASSESS Project Subgroup Report on Dissemination and Impact. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care. 1997; 13 (2):220–86. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Greenhalgh T, Robert G, MacFarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of Innovation in Service Organizations: Systematic Review and Recommendations. The Milbank Quarterly. 2004; 82 (4):581–629. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Greer A. The State of the Art versus the State of the Science: The Diffusion of New Medical Technologies into Practice. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care. 1988; 4 :5–26. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Grimshaw J, Eccles M, Tetroe J. Implementing Clinical Guidelines: Current Evidence and Future Implications. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions. 2004; 24 (suppl. 1):S31–S37. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Grimshaw J, Shirran RL, Thomas G, Mowatt C, Fraser L, Bero R, Grilli E, Harvey A, O'Brien MA. Changing Provider Behaviour: An Overview of Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Medical Care. 2001; 39 (suppl. 2):I12–I45. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hanney S, Gonzalez-Block M, Buxton M, Kogan M. The Utilization of Health Research in Policy-Making: Concepts, Examples and Methods of Assessment. Health Research Policy and Systems. 2003; 1 (2) [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hemsley-Brown J. Facilitating Research Utilization: A Cross-Sector Review of Research Evidence. International Journal of Public Sector Management. 2004; 17 (6):534–52. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hennink M, Stephenson R. Using Research to Inform Health Policy: Barriers and Strategies in Developing Countries. Journal of Health Communication. 2005; 10 :163–80. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Innvaer S, Vist G, Trommold M, Oxman A. Health Policy Makers' Perceptions of Their Use of Evidence: A Systematic Review. Journal of Health Services and Research Policy. 2002; 7 :239–44. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jacobson N, Butterill D, Goering P. Development of a Framework for Knowledge Translation: Understanding User Context. Journal of Health Services and Research Policy. 2003; 8 :94–99. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jacobson N, Butterill D, Goering P. Organizational Factors That Influence University-Based Researchers' Engagement in Knowledge Transfer Activity. Science Communication. 2004; 23 (3):246–59. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jacobson N, Butterill D, Goering P. Consulting as a Strategy for Knowledge Transfer. The Milbank Quarterly. 2005; 83 (2):299–321. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kiefer L, Frank J, Di Ruggerio E, Dobbins M, Manuel D, Gully P, Mowat D. Fostering Evidence-Based Decision-Making in Canada: Examining the Need for a Canadian Population and Public Health Evidence Centre and Research Network. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2005; 96 :I-1–I-19. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kothari A, Birch S, Charles C. “Interaction” and Research Utilisation in Health Policies and Programs: Does It Work? Health Policy. 2005; 71 (1):117–25. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kramer DM, Cole DC. Sustained, Intensive Engagement to Promote Health and Safety Knowledge Transfer to and Utilization by Workplaces. Science Communication. 2003; 25 (1):56–82. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kramer DM, Wells RP. Achieving Buy-In: Building Networks to Facilitate Knowledge Transfer. Science Communication. 2005; 26 (4):428–44. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kuruvilla S, Mays N, Pleasant A, Walt G. Describing the Impact of Health Research: A Research Impact Framework. BMC Health Services Research. 2006; 6 :134. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Landry R, Amara N, Lamari M. Utilization of Social Science Research in Canada. Research Policy. 2001; 30 :333–49. [ Google Scholar ]

- Landry R, Lyons R, Amara N, Warner G, Ziam S, Halilem N, Keroack M. Quebec City: Université Laval, Atlantic Health Promotion Research Centre, Dalhousie University; 2006. Knowledge Translation: Planning Tools for Stroke Researchers. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lavis J, Lomas J, Hamid M, Sewankambo NK. Assessing Country-Level Efforts to Link Research to Action. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2006; 84 (8):620–28. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lavis J, Posada F, Haines A, Osei E. Use of Research to Inform Public Policymaking. The Lancet. 2004; 364 :1615–21. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lavis J, Robertson J, Woodside C, McLeod C, Abelson J. How Can Research Organizations More Effectively Transfer Research Knowledge to Decision Makers? The Milbank Quarterly. 2003a; 81 :221–48. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lavis J, Ross S, Hurley J, Hohenadel J, Stoddart G, Woodward C, Abelson J. Examining the Role of Health Services Research in Public Policymaking. The Milbank Quarterly. 2002; 80 (1):125–54. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lavis J, Ross S, McLeod C, Gildiner A. Measuring the Impact of Health Research. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. 2003b; 8 :165–70. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lewis S. Toward a General Theory of Indifference to Research-Based Evidence. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. 2007; 12 (3):166–72. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Loiselle CG, Semenic S, Cote B. Sharing Empirical Knowledge to Improve Breastfeeding Promotion and Support: Description of a Research Dissemination Project. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing. 2005; 2 (1):25–32. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lomas J. Hamilton, Ontario: McMaster University Centre for Health Economics and Policy Analysis; 1997. Improving Research Dissemination and Uptake in the Health Sector: Beyond the Sound of One Hand Clapping. Policy Commentary C97-1. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lomas J. Connecting Research and Policy. ISUMA: Canadian Journal of Policy Research. 2000a; 1 (1):140–44. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lomas J. Using “Linkage and Exchange” to Move Research into Policy at a Canadian Foundation. Health Affairs. 2000b; 19 (3):236. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lomas J. The In-Between World of Knowledge Brokering. British Medical Journal. 2007; 334 :129–32. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Martens P, Roos N. When Health Services Researchers and Policy Makers Interact: Tales from the Tectonic Plates. Healthcare Policy. 2005; 1 (1):72–84. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mitton C, Patten S. Evidence Based Priority Setting: What Do the Decision Makers Think? Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. 2004; 9 (3):146–52. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mubyazi GM, Gonzalez-Block MA. Research Influence on Antimalarial Drug Policy Change in Tanzania: Case Study of Replacing Chloroquine with Sulfadoxine-Pyrimethamine as the First-Line Drug. Malaria Journal. 2005; 20 (4):51. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Philip KL, Backett-Milburn K, Cunningham-Burley S, Davis JB. Practising What We Preach? A Practical Approach to Bringing Research, Policy and Practice Together in Relation to Children and Health Inequalities. Health Education Research. 2003; 18 (5):568–79. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pyra K. Knowledge Translation: A Review of the Literature: Prepared for the Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation. 2003. [accessed April 29, 2006]. Available at, http://www.nshrf.ca/AbsPage.aspx?siteid=1&lang=1&id=1059 .

- Rashiq S, Barton P, Harstall C, Schopflocher D, Taenzer P Alberta Ambassador Program Team. The Alberta Ambassador Program: Delivering Health Technology Assessment Results to Rural Practitioners. BMC Medical Education. 2006; 6 (21) [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Reimer B, Sawka E, James D. Improving Research Transfer in the Addictions Field: A Perspective from Canada. Substance Use and Misuse. 2005; 40 (11):1707–20. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Robinson K, Elliott SJ, Driedger SM, Eyles J, O'Loughlin J, Riley B, Cameron R, Harvey D on behalf of the CHHDP Strategic and Research Advisory Groups. Using Linking Systems to Build Capacity and Enhance Dissemination in Heart Health Promotion: A Canadian Multiple-Case Study. Health Education Research. 2005; 20 (5):499–513. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 4th ed. New York: Free Press; 1995. [ Google Scholar ]

- Roos NP, Shapiro E. From Research to Policy: What Have We Learned? Medical Care. 1999; 37 (suppl. 6):JS291–305. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ross S, Lavis J, Rodriguez C, Woodside J, Denis JL. Partnership Experiences: Involving Decision-Makers in the Research Process. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. 2003; 8 (suppl. 2):26–34. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sibbald WJ, Kossuth J. The Ontario Health Care Evaluation Network and the Critical Care Research Network as Vehicles for Research Transfer. Medical Decision Making. 1998; 18 :9–16. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Soumerai S, Avorn J. Principles of Educational Outreach (“Academic Detailing”) to Improve Clinical Decision-Making. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1990; 263 :549–56. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stewart R, Wiggins M, Thomas J, Oliver S, Brunton G, Ellison GTH. Exploring the Evidence–Practice Gap: A Workshop Report on Mixed and Participatory Training for HIV Prevention in Southern Africa. Education for Health. 2005; 18 (2):224–35. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stinson L, Pearson D, Lucas B. Developing a Learning Culture: Twelve Tips for Individuals, Teams and Organizations. Medical Teacher. 2006; 28 (4):309–12. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stocking B. Initiative and Inertia: Case Studies in the NHS. London: Nuffield Trust; 1985. [ Google Scholar ]

- Thompson GN, Estabrooks CA, Degner LF. Clarifying the Concepts in Knowledge Transfer: A Literature Review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2006; 53 (6):691–701. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Trostle J, Bronfman M, Langer A. How Do Researchers Influence Decision-Makers? Case Studies of Mexican Policies. Health Policy and Planning. 1999; 14 (2):103–14. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vingilis E, Hartford K, Schrecker T, Mitchell B, Lent B, Bishop J. Integrating Knowledge Generation with Knowledge Diffusion and Utilization. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2003; 94 (6):468–71. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- von Lengerke T, Rutten A, Vinck J, Abel T, Kannas L, Luschen G, Diaz J, van der Zee J. Research Utilization and the Impact of Health Promotion Policy. Soz. Praventivmed. 2004; 49 :185–97. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Waddell C, Lavis J, Abelson J, Lomas J, Shepherd C, Bird-Gayson T, Giacomini M, Offord D. Research Use in Children's Mental Health Policy in Canada: Maintaining Vigilance amid Ambiguity. Social Science and Medicine. 2005; 61 :1649–57. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Weatherly H, Drummond M, Smith D. Using Evidence in the Development of Local Health Policies: Some Evidence from the United Kingdom. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care. 2002; 18 (4):771–81. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Weiss C. The Many Meanings of Research Utilization. Public Administration Review. 1979; 39 (5):426–31. [ Google Scholar ]

- Whiteford H. Can Research Influence Mental Health Policy? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2001; 35 :428–34. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Whitehead M, Petticrew M, Graham H, Macintyre S, Bambra C, Egan M. Evidence for Public Health Policy on Inequalities: 2: Assembling the Evidence Jigsaw. Journal of Epidemiology in Community Health. 2004; 58 :817–21. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Willison D, MacLeod S. The Role of Research Evidence in Pharmaceutical Policy-Making: Evidence When Necessary but Not Necessarily Evidence. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 1999; 5 (2):243–49. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Knowledge Transfer in Theory and Practice: A Guide to the Literature

A brief guide to the issues of Knowledge Transfer, taking into account the variety of terminology, methods, and subjects.

Related Papers

Dianne Hall

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences

Noor Alia Hanim Hassan

WTZ-Süd Working Paper

Markus Hayden

'Knowledge transfer' is a topic of general interest, being one of the key links between the research arena and both practice and civil society, yet it has attracted scant scholarly attention. Furthermore, prior research on knowledge transfer has typically focused on particular aspects, leading to the investigation of specific topics, such as exploitation, and of specific groups, such as researchers. Therefore, based on our previous research, the current study attempts to widen the scope of enquiry by interviewing experts in the field of knowledge transfer from both inside and outside of academia. This paper gives an insight into our research strategy and presents the preliminary findings that have been obtained from the first 12 interviews.

Advances in Methodology and Statistics

Helena Kovačič

Learning theory proposes that learning outcomes depend on the characteristics of actors involved in the process. Network theory adds additional dimension to studying learning process. According to several network scholars, relations between learning actors also affect their behaviour and performance. We present a framework for knowledge transfer process that allows a study of how results of a transfer are affected by the characteristics of source and recipient and connections between them. We apply this model to the survey of learning process within two European projects leading to different outcomes of the process. Results of the survey reveal close connection between the two sets of indicators and point to the holistic approach to examining knowledge transfer process.

Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A

Catherine Herfeld

Sajjad Mohammed Jasimuddin

Saša Rađenović

Theoretical Frameworks and Empirical Research

Denis St Jacques

… and institutions in regional innovation systems. …

Bart Nooteboom

Abstract: A central feature of innovation systems is that innovation arises from interaction between organizational units. This requires' cognitive distance'that is sufficiently large to yield novelty of combinations, but not too large for mutual understanding. Two problems and solutions in the transfer of knowledge, especially to small firms, are identified and discussed. There is a problem not only of expressing tacit knowledge, but also of absorbing new knowledge when it needs to replace existing tacit knowledge. Next to issues of learning or ...

Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes

Richard Moreland

RELATED PAPERS

Goran Shoan

Gabriela Luisa Eckel

Finda tyas Alfianti

Haron Crisóstomo Castañon Mattos

The Journal of Qazvin University of Medical Sciences

Ahmet Buğra HAMŞIOĞLU

Ezra Wafula

Arlina Dewi

European journal of heart failure

Virginia Bovolo

Sandra Velásquez

maria luisa Marchi

Christian M A N U E L Moreno Rocha

Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM

Volume 25 Number 2 July 2016

Rawshan Ara Perveen

Edumecentro

Michel Pérez Pino

Quality : Jurnal Kesehatan

Raden Candra

Revista Agrogeoambiental

Julierme Wagner da Penha (Inconfidentes)

Najmi Soraya

PSIKOSAINS (Jurnal Penelitian dan Pemikiran Psikologi)

Tugimin Supriyadi

Eliane Abreu

Ramli Cibro

Anne Shangrila Fuentes

2020 XXXIIIrd General Assembly and Scientific Symposium of the International Union of Radio Science

Ruben Alves

Clinical and Applied Thrombosis/Hemostasis

Serhat Vançelik

See More Documents Like This

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 13 September 2021

Use and effectiveness of policy briefs as a knowledge transfer tool: a scoping review

- Diana Arnautu 1 &

- Christian Dagenais 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 8 , Article number: 211 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

13k Accesses

15 Citations

100 Altmetric

Metrics details

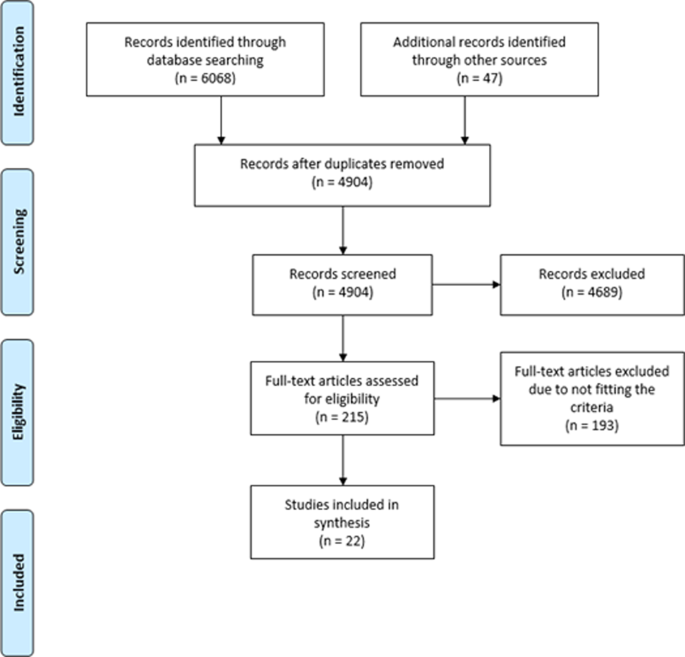

- Health humanities

- Medical humanities

There is a significant gap between researchers’ production of evidence and its use by policymakers. Several knowledge transfer strategies have emerged in the past years to promote the use of research. One of those strategies is the policy brief; a short document synthesizing the results of one or multiple studies. This scoping study aims to identify the use and effectiveness of policy briefs as a knowledge transfer strategy. Twenty-two empirical articles were identified, spanning 35 countries. Results show that policy briefs are considered generally useful, credible and easy to understand. The type of audience is an essential component to consider when writing a policy brief. Introducing a policy brief sooner rather than later might have a bigger impact since it is more effective in creating a belief rather than changing one. The credibility of the policy brief’s author is also a factor taken into consideration by decision-makers. Further research needs to be done to evaluate the various forms of uses of policy briefs by decision-makers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Artificial intelligence and illusions of understanding in scientific research

Lisa Messeri & M. J. Crockett

Adapted large language models can outperform medical experts in clinical text summarization

Dave Van Veen, Cara Van Uden, … Akshay S. Chaudhari

Globally representative evidence on the actual and perceived support for climate action

Peter Andre, Teodora Boneva, … Armin Falk

Introduction

Improving well-being and reducing health-related inequalities is a challenging endeavor for public policymakers. They must consider the nature and significance of the issue, the proposed interventions and their pros and cons such as their impact and acceptability (Lavis et al., 2012 ; Mays et al., 2005 ). Policymakers are members of a government department, legislature or other organization responsible for devising new regulations and laws (Cambridge University Press, 2019 ). They face the challenge of finding the best solutions to multiple health-related crises while being the most time and cost-effective possible. Limited by time and smothered by an overwhelming amount of information, some policymakers are likely to use cognitive shortcuts by selecting the “evidence” most appropriate to their political leanings (Baekgaard et al., 2019 ; Cairney et al., 2019 ; Oliver and Cairney, 2019 ).

To prevent snap decisions in policymaking, it is essential to develop tools to facilitate the dissemination and use of empirical research. Evidence-informed solutions might be an effective way to address these complicated questions since they derive knowledge from accurate and robust evidence instead of beliefs and provide a more holistic view of a problem. Although it may be possible for different stakeholders to agree on certain matters, a consensus is uncommon (Nutley et al., 2013 ). Using research evidence allows policymakers to decrease their bias towards an intervention’s perceived effectiveness. This leads to more confidence among policymakers on what to expect from an intervention as their decisions are guided by evidence (Lavis et al., 2004 ). However, trying to integrate research findings into the policy-making process comes with a whole new set of challenges, both for researchers and policymakers.

Barriers to evidence-informed policy

Barriers to evidence-informed policy can be defined in three categories: the research evidence is not available in an accessible format for the policymaker, the evidence is disregarded for political or ideological reasons and the evidence is not applicable to the political context (Hawkins and Pakhurst, 2016 ; Uzochukwu et al., 2016 ).

The first category of barriers refers to the availability and the type of evidence. The vast amount of information policymakers need to keep up-to-date in specific fields is a particular challenge to this barrier, leading to policymakers being frequently overwhelmed with the amount of information they need to go through regarding each case (Orandi and Locke, 2020 ). Decision-makers have reported a lack of competencies in finding, evaluating, interpreting or using certain evidence such as systematic reviews in their decision-making, leading to difficulty in accessing these reviews and identifying the key messages quickly (Tricco et al., 2015 ). Although policymakers use a broader variety of forms of evidence than previously examined in the literature, scholars have rarely been consulted and research evidence has rarely been seen as directly applicable (Oliver and de Vocht, 2017 ). The lack of awareness on the importance of research evidence and on the ways to access these resources also contribute to the gap between research and policy (Oliver et al., 2014 ; van de Goor et al., 2017 ). Some other frequently reported barriers to evidence use in policymaking were the poor access to timely, quality and relevant research evidence as well as the limited collaboration between policymakers and researchers (Oliver et al., 2014 ; Uzochukwu et al., 2016 ; van de Goor et al., 2017 ). Given the fact that research is only one input amongst all the others that policymakers must consider in their decision, it is no surprise that policymakers may disregard research evidence in favor of other sources of information (Uzochukwu et al., 2016 ).

The second category of barriers refers to policymakers’ ideology regarding research evidence and the presence of biases. Resistance to change and a lack of willingness by some policymakers to use research are two factors present when attempting to bridge the gap. This could be explained by certain sub-cultures of policymaking that grants little importance to evidence-informed solutions or by certain policymakers prioritizing their own opinion when research findings go against their expectations or against current policy (Koon et al., 2013 ; Uzochukwu et al., 2016 ). Policymakers tend to interpret new information based on their past attitudes and beliefs, much like the general population (Baekgaard et al., 2019 ). It also does not seem to persuade policymakers with beliefs opposed to the evidence, rather it increases the effect of attitudes on the interpretation of information by policymakers (Baekgaard et al., 2019 ). This highlights the importance of finding methods to disseminate tailored evidence in a way that policymakers will be open to receive and consider (Cairney and Kwiatkowski, 2017 ).

The third category of barriers refers to the evidence produced not always being tailor-made for application in different contexts (Uzochukwu et al., 2016 ; WHO, 2004 ). Indeed, the political context is an undeniable factor in the use of evidence in policymaking. Political and institutional factors such as the level of state centralization and democratization, the influence of external organizations and donors, the organization of bureaucracies and the social norms and values, can all affect the use of evidence in policy (Liverani et al., 2013 ). The elaboration of new policies implies making choices between different priorities while taking into consideration the limited resources available (Hawkins and Pakhurst, 2016 ). The evidence of research can always be contested or balanced with the potential negative consequences of the intervention in another domain, such as a health-care intervention having larger consequences on the economy. Even if the effectiveness of an intervention can be proved beyond doubt, this given issue might not be a priority for decision-makers, or it might involve unrealistic resources that would rather be granted to other issues. Policymakers need to stay aware of the political priorities identified and the citizens they need to justify their decisions to. In this sense, politics and institutions are not a barrier to the use of research but rather they are the context under which evidence must respond to (Cairney and Kwiatkowski, 2017 ; Hawkins and Parkhurst, 2016 ).

Summaries to prevent information overload

A great deal of research evidence has been developed but not enough of it is being disseminated in effective ways (Oliver and Boaz, 2019 ). Offering a summary of research results in an accessible format could facilitate policy discussion and ultimately improve the use of research and help policymakers with their decisions (Arcury et al., 2017 ; Cairney and Kwiatkowski, 2017 ). In this age of information overload, when too much information is provided, one can have trouble discerning what is most important and make a decision. It is not unlikely that policymakers will, after a brief glance, discard a large amount of information given to them (Beynon et al., 2012 ; Yang et al., 2003 ). Decision-makers oftentimes criticize the length and overly dense contents of research documents (Dagenais and Ridde, 2018 ; Oliver et al., 2014 ). Hence, summaries of research results could increase the odds of decision-makers reading and therefore using the evidence proposed by researchers.