An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Health Hum Rights

- v.23(2); 2021 Dec

Climate Justice, Humans Rights, and the Case for Reparations

Audrey r. chapman.

Healey Professor of Medical Ethics and Humanities at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine, and an adjunct professor at the University of Connecticut Law School, USA.

A. Karim Ahmed

Honorary professor at the University of Cape Town, South Africa; an adjunct professor of occupational and environmental medicine at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine, USA; and a founding board member of the Global Council for Science and the Environment, Washington, DC, USA.

The global community is facing an existential crisis that threatens the web of life on this planet. Climate change, in addition to being a fundamental justice and ethical issue, constitutes a human rights challenge. It is a human rights challenge because it undermines the ability to promote human flourishing and welfare through the implementation of human rights, particularly the right to life and the right to health. It is also a human rights challenge because climate change disproportionately impacts poor and the vulnerable people in both low-income and high-income countries. Those living in many low-income countries are subject to the worst impacts of climate change even though they have contributed negligibly to the problem. Further, low-income countries have the fewest resources and capabilities at present to adapt or cope with the severe, long-lasting impacts of climate change. Building on human rights principles of accountability and redress for human rights violations, this paper responds to this injustice by seeking to make long-neglected societal amends through the implementation of the concept of climate reparations. After discussing the scientific evidence for climate change, its environmental and socioeconomic impacts, and the ethical and human rights justifications for climate reparations, the paper proposes the creation of a new global institutional mechanism, the Global Climate Reparations Fund, which would be linked with the United Nations Human Rights Council, to fund and take action on climate reparations. This paper also identifies which parties are most responsible for the current global climate crisis, both historically and currently, and should therefore fund the largest proportion of climate-related reparations.

Introduction

At the beginning of the third decade of the 21st century, we are confronting an unprecedented crisis of global climate change. However, neither the causes nor the impacts of climate change are equally shared among different regions of the world. While the first scientific evidence that global warming from the continuing emission of greenhouse gases posed an existential threat to life on earth was pointed out many decades ago, it did not become a priority concern for policy makers until recently. The scientific evidence now leaves no doubt that climate change is human induced. Above all, its current and potential environmental impacts and socioeconomic consequences are well documented and agreed on by the global scientific and policymaking communities. 1

In discussions about climate change and global warming, one policy issue that needs greater and more immediate attention is the question of who bears the primary ethical responsibility and financial obligation for addressing this crisis. There is increasing reason to believe that the severest consequences of global warming will fall most heavily on low-income countries and vulnerable groups who have been of priority concern to the human rights community. This paper examines the human rights dimensions of this problem, placing it within a climate justice context. The critical question we consider is this: What role should high-income countries undertake in meeting their obligation to not only significantly reduce and mitigate their current emissions of greenhouse gases but also to make reparations for the harm their emissions, both historically and at present, have inflicted on low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)?

Impact of climate change on the web of life

Today, climate change and its accompanying global warming are a fact of life. We have already reached a global mean temperature of 1.1°C over pre-industrial levels. 2 In its 2018 interim special report, the expert Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicted that a global temperature increase of 1.5°C over pre-industrial levels would occur sometime between 2030 and 2052, which could have catastrophic effects on the web of life on this planet. 3 In its most recent assessment report (published in August 2021), the IPCC concluded in no uncertain terms:

It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land. Widespread and rapid changes in the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere and biosphere … The scale of recent changes across the climate as a whole and the present state of many aspects of the climate system are unprecedented over many centuries to many thousand of years … Human-induced climate change is already affecting many weather and climate extremes in every region across the globe. Evidence of observed changes in extremes such as heatwaves, heavy precipitation, droughts, and tropical cyclones, and in particular, their attribution to human influence, has strengthened since AR5 [an assessment report published by IPCC in 2014]. 4

What is not entirely clear is where our future lies—whether we can slow this rate of increase or whether will we allow this trend to continue, with climatic conditions that would undermine the web of life and render many regions of our planet problematic for human flourishing.

Present and historical sources of greenhouse gas emissions

One way of assessing the contribution of current and past greenhouse gas emissions to global warming is to examine its major contributing component, namely carbon dioxide (CO 2 ), a major by-product of fossil fuel combustion. The estimated global annual emissions of CO 2 were about 5 billion metric tons in 1950, increasing to 22 billion metric tons by 1990, with the most recent estimate (2019) reaching over 36 billion metric tons. 5 This amounts to greater than a sevenfold increase in annual atmospheric CO 2 emissions in 70 years, while the world population rose only threefold in that same time frame (2.5 billion to 7.8 billion). 6 These figures reflect a sharp increase in per capita combustion of fossil fuels, which have provided the main source of energy for a fast-growing world economy. However, this dependence on fossil fuels has come at a high a price—a warming planet at the edge of a precipitous global calamity.

A significant contributor to global warming is the amount of greenhouse emissions emitted by high-income countries. A recent analysis conducted by the World Resources Institute points out the stark differences between top and bottom greenhouse gas emitters:

The top three greenhouse gas emitters—China, the European Union and the United States—contribute 41.5% of total global emissions, while the bottom 100 countries account for only 3.6%. Collectively, the top 10 emitters account for over two-thirds of global [greenhouse gas] emissions. 7

Currently, China leads the world in annual atmospheric carbon dioxide emissions, followed by the United States, India, the Russian Federation, and Japan. In the last decade, China overtook the United States as the largest annual source of emissions of CO 2 . In Table 1 , the top 10 annual emitters of CO 2 from fossil fuel combustion in 2018 are listed by country.

Top 10 current atmospheric CO 2 emitters from fossil fuel combustion

Source: International Energy Agency, IEA atlas of energy: CO 2 emissions from fuel combustion (Paris: International Energy Agency, 2021). Available at http://energyatlas.iea.org/#!/tellmap/1378539487/0.

With regard to historical greenhouse gas emissions, since the beginning of the industrial age in the mid-18th century, the United States has been by far the biggest contributor to atmospheric CO 2 . Table 2 lists the top 15 historical contributors.

List of largest historical emitters of atmospheric CO 2 (1751 to 2017)

Source: H. Ritchie, “Who has contributed most global CO 2 emissions?,” Our World in Data (2019). Available at https://ourworldindata.org/contributed-most-global-co2.

As can be seen in Table 2 , the United States and the European Union’s 28 countries (which included the United Kingdom until last year) are the largest cumulative contributors to present-day global warming, accounting for over half (51%) of the historical emissions of greenhouse gases. Additionally, the top 15 contributors account for over 88% of past cumulative CO 2 emissions.

Countries’ per capita annual emissions differ significantly. Table 3 presents the per capita CO 2 emissions of the top 21 countries in 2018, the latest year for which such data are available.

Per capita annual emissions of CO 2 by country (2018)

Source: Union of Concerned Scientists, Each country’s share of CO 2 emissions (August 12, 2020). Available at https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/each-countrys-share-co2-emissions.

The human rights impact of global climate change

Global climate change constitutes a major human rights challenge because the magnitude and severity of its adverse consequences will not be experienced equally by all people—rather, it will be felt most acutely in low-income populations and other groups already susceptible to human rights abuses. In her opening statement to the 42nd session of the Human Rights Council in 2019, Michele Bachelet, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, warned that “the human rights implications of currently projected levels of global heating are catastrophic.” 8 She went on to state that “climate change threatens the effective enjoyment of a range of human rights including those to life, water and sanitation, food, health, housing, self-determination, culture and development.” 9 Consistent with our call for a human rights response to climate change, she added that “states have a human rights obligation to prevent the foreseeable adverse effects of climate change and ensure that those affected by it, particularly those in vulnerable situations, have access to effective remedies and means of adaptation to enjoy lives of human dignity.” 10 She reiterated these concerns in 2021 in her statement to the 48th session of the Human Rights Council, stating that as the interlinked crises of climate change, pollution, and biodiversity loss multiply, “they will constitute the single greatest challenge to human rights in our era.” 11

Clearly, global climate change is already undermining the ability to promote human flourishing and welfare through the implementation of economic and social rights in many societies and will increasingly be problematic. The global climate crisis also affects the ability to protect and promote specific human rights. Among them are the right to life and the right to health, as well as several social determinants of the right to health, such as access to nutritious food, safe water, sanitation, and housing. In relation to public health, the adverse health consequences caused by climate change include heat-related disorders, greater incidence of water-related and vector-borne diseases, respiratory and allergic disorders, malnutrition, violence, and mental health problems. 12

Underscoring the impact of climate change on human health, more than 230 leading medical journals from a wide range of countries published a joint editorial a few weeks ahead of the 2021 COP26 climate conference in Glasgow to warn that the greatest threat to public health would be the failure to prevent the global temperature from rising above 1.5°C. The editorial echoes the warnings that health is already being harmed by global temperature increases. 13 Such health consequences will most severely impact infants and young children, especially those living in low-income countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. This is because, compared to adults, children require more food and water per unit of their body weight, are less able to survive extreme weather events, and are particularly susceptible to toxic chemicals, temperature changes, and diseases. 14 According to a recently published UNICEF report, one billion children are at extremely high risk of the impacts of the climate crisis. 15 The report indicates that the aggregate disease burden of children living in LMICs from climate-related outcomes, such as malnutrition, diarrhea, and malaria, is likely to increase. Henrietta Fore, UNICEF’s executive director, warns that “virtually no child’s life will be unaffected,” making climate change a children’s rights crisis. Moreover, she notes that children from countries that are least responsible will suffer most. 16

Among the people most vulnerable to climate change are members of minority and Indigenous groups, older individuals, people with chronic diseases and disabilities, and low-income people living in marginal environments. Climate change will make women’s responsibility for gathering water, food, and fuel for their households in poor countries more difficult. Because the lives of Indigenous people are so closely tied to the natural environment, they are likely to suffer both disproportionate physical loss and a sense of spiritual loss and a lack of well-being. 17 People who will be particularly susceptible to the health consequences of climate change also consist of many of the vulnerable groups of concern to the human rights community: those who are poor, members of minority groups, older people, people with chronic diseases and disabilities, and workers exposed to extreme heat. 18 Moreover, individuals from these communities will lack the resources to adapt to and cushion the blows from climate change. There is thus concern that the intranational socioeconomic disparities between affluent and disadvantaged groups due to the impacts of climate change may enter into a self-reinforcing vicious circle, whereby the initial inequality will result in disadvantaged groups suffering disproportionately, leading to greater subsequent inequality. 19

Most unjustly, even though individuals in LMICs have contributed negligibly to global warming, they are being subjected to the worst impacts of climate change currently and will be increasingly into the future. Eight of the 10 countries most affected by the quantifiable impacts of extreme weather events in 2019 were in the low-to lower-middle-income category and half were least-developed countries. 20 Small island states are particularly vulnerable to the sea level rise. Some of them, such as the Bahamas, Kiribati, the Marshall Islands, and the Maldives, are currently only a mere three to four meters above mean sea level. Like other LMICs, many of these small island states also have limited funds and poorly developed infrastructures, making it difficult for them to adapt to these challenges. 21 Likewise, Bangladesh, with its flat, low-lying and delta-exposed topography and high population density, is very vulnerable to sea level rise. 22 Much of the population in many LMICs lives in rural areas and is dependent on agriculture, a sector that is highly vulnerable to environmental conditions, particularly when it comes to steady access to a supply of water. African countries, already some the poorest and most disadvantaged countries, are among the most vulnerable to climate change because of multiple existing stresses and low adaptation capacity. Prolonged drought in many areas is drastically reducing water resources and food productivity, resulting in severe famine conditions. 23

Recently, the Human Rights Council, at its 48th session, adopted a resolution recognizing a new right: the right to a safe, clean, healthy, and sustainable environment. The resolution encourages member states to build capacity for efforts to protect the environment. It also asks member states to adopt policies for the enjoyment of the right. 24

Several Special Rapporteurs in the United Nations human rights system have mandates that overlap with policy issues related to the climate crisis; these include the Special Rapporteurs on health, on food, on safe water and sanitation, and on Indigenous peoples. The Special Rapporteur on human rights and the environment does so even more directly. During its 48th session in October 2021, the Human Rights Council also established a Special Rapporteur with a mandate to promote and protect human rights in the context of climate change. 25

The case for climate reparations

Human rights obligations require that states cooperate toward the promotion of human rights globally, and as the High Commissioner for Human Rights has stated, this should include adequate financing from those who can best afford it for climate change mitigation, adaptation, and rectification of damage. 26 Moreover, for equity to be at the center of the global response, countries that have disproportionately created this environmental crisis must do more to compensate for damages they have caused, particularly with respect to the most vulnerable countries. This brings us to the subject of reparations.

Reparations are generally understood as an effort to redress significant societal harm through acknowledgment of wrongdoing and through in-kind and monetary means. Reparatory justice also entails acceptance of responsibility, followed by undertaking measures that seek to address and repair societal injustices and widespread harms. 27 Applied to climate change, reparations would first entail identifying those entities—both countries and private corporations—whose greenhouse gas emissions have contributed the most to climate change. It would require countries and the international community to recognize the harms they have caused, in order to rectify the serious damage being inflicted disproportionately on low-income countries as a result of climate change. 28

Climate reparations are justified by the principles of fairness and equity. Here, the principles identified by philosopher Henry Shue are helpful to consider. 29 According to Shue, the “first principle” of equity is the following:

When a party has in the past taken an unfair advantage of others by imposing costs upon them without their consent, those who have been unilaterally put at a disadvantage are entitled to demand that in the future the offending party shoulder burdens that are unequal at least to the extent of the unfair advantage previously taken, in order to restore equality. 30

To put it more simply, those who have made a greater contribution to a harmful problem and received its benefit have an obligation to rectify it. According to Shue, in the area of development and the environment, the initiation of global warming by the process of industrialization, which has enriched the Global North but not the South, constitutes a clear example of this principle. In response to those who argue that today’s generation in the industrialized states should not be held responsible for damage done by previous generations, he points out that contemporary generations are reaping the benefits of rich industrial societies and have continued to contribute to global warming despite their awareness of its harmful consequences. 31 This means that the countries that have received most of the historical benefits of industrialization and enjoyed the highest income from oil and gas extraction should bear the burden of financing reparations to benefit the most affected low-income countries, which have generally made little contribution to the serious, long-lasting consequences of climate change.

Shue’s “second principle” of equity is related to certain parties’ greater ability to pay. This principle states, “Among a number of parties, all of whom are bound to contribute to some common endeavour, the parties who have the most resources normally should contribute the most to the endeavour.” 32 When applied to the climate crisis, this principle further places the equity burden on high-income countries, which are most able to pay for adaptation to the climate crisis, and not the low-income countries, which are least able to pay to make themselves more resilient to climate risks. This principle additionally lays at least some of the responsibility on the major corporations involved with fossil fuel extraction and sales.

Shue’s “third principle” of equity serves the purpose of avoiding making those who are already worst off even more worse off. According to Shue, in a situation of radical inequality, fairness demands that those people with less than enough for a decent human life be provided with enough. This principle of equity states:

When some people have less than enough for a decent human life, other people have far more than enough, and total resources available are so great that everyone could have at least enough without preventing some people from retaining considerably more than others have, it is unfair not to guarantee everyone at least an adequate minimum. 33

Maintaining a guarantee of an adequate minimum could mean either not interfering with others’ ability to maintain a minimum for themselves or embracing a stronger requirement to provide assistance to enable others to do so. One implication is that any agreement to cooperate made between one group of people having more than enough and another group of people who do not have enough cannot justifiably require those in the second group to make sacrifices. Applied to the climate crisis, countries that are operating climate harmful industrial processes cannot ask low-income countries, which are poor in large part because they have not industrialized, to make sacrifices in order to rectify the problem.

Taken together, these equity principles require that whatever needs to be done about global climate change, the costs should be borne by those most responsible and not by the countries currently most affected. In a detailed review of the key factors that should be considered in framing a rationale for climate reparations, Maxine Burkett states:

In the absence of a substantial commitment to remedy the harm faced by the climate vulnerable, reparations for damage caused by climate change can provide a comprehensive organising principle for claims against those most responsible while placing key ethics and justice concerns—concerns that have been heretofore woefully under-emphasised—at the centre of the climate debate. 34

Applied here, climate reparations would require raising funds and material resources from the governments in the countries most responsible historically for the climate crisis. We also propose that the major fossil fuel extraction corporations be held responsible for their role in contributing to climate change and therefore be asked to contribute to reparations. Not only have they profited financially over time, but these corporations have led a campaign over many years to deny the existence of human-induced climate change, funding scientists and lobbyists to do their bidding—and then when it was no longer possible to deny the existence of climate change, they argued that fossil fuel extraction and use were not the cause. 35

A one-off payment would not offer a permanent solution to the disproportionate impacts of climate change. Instead, climate reparations should be envisioned as a series of initiatives to raise financial assistance, transfer resources, and provide technical expertise to low-income and vulnerable countries, as well as requiring all countries, particularly the affluent industrialized countries in Western Europe, the United States, and China, to adopt significantly more carbon-free energy policies. 36

International framework to implement climate reparations

A program of global climate reparations requires an international mechanism for implementation. There is an existing institution—the Green Climate Fund (GCF)—intended to provide economic assistance to low-income countries detrimentally affected by climate change. The GCF was agreed to by the Conference of the Parties in 2010 under the aegis of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. It became operational a few years later, with administrative offices located in Incheon, South Korea. 37 It is currently the largest international fund dedicated to fighting climate change. Part of its mandate is to assist low-income countries in mitigating and adapting to climate change through project design and implementation. 38 Its 24-member board has equal representation from low- and high-income countries. Its funds are derived from public and private sources, including multilateral, regional and national development agencies; international and national banks; and private equity institutions. 38 It should be noted that the GCF operates on technical and economic grounds, not ethical or human rights principles.

Unfortunately, the GCF has been unable to raise sufficient funds to fulfill its mandate and meet the needs of the low-income countries most affected by climate change. At the COP15 held in 2009 in Copenhagen, Denmark, participating countries committed to raise US$100 billion per year by 2020 through public and private sources to fund climate-related programs. 39 While there is considerable controversy over what should be counted as part of that US$100 billion per year, one of the mechanisms for collecting and distributing these funds to low- and middle-income countries is the GCF. According to its latest annual report (2020), the GCF had raised US$2.1 billion, with another US$2.8 billion committed through private investments to programs related to mitigation (63%) and adaptation (37%). However, only US$1.5 billion of these funds were allocated to lower-income countries, African states, and climate-vulnerable countries, such as small island states. 40 It is believed that such a shortfall of climate-related funds can be laid primarily at the feet of many industrialized countries, whose financial contributions to the GCF have been quite disappointing to date. 41 Therefore, the present international mechanism for providing funds for climate-related programs is seriously failing to meet its intended purpose, let alone serve as the potentially chief instrument for a more ambitious climate reparations initiative.

We think that it is important to respond to climate change on the basis of equity and human rights rather than on economic or technical grounds, including with regard to the manner in which programs will be executed. It may well be that the reason the GCF has raised only a fraction of the funds committed 10 years ago at COP16 is in part because neither ethical nor human rights appeals have been made. Moreover, donations to the GCF have been voluntary and haphazard. There have been no formulas setting forth expected donations. A human rights and ethical approach centered on reparations principles with a related levy mechanism may be more effective in garnering financial support. The most recent IPCC report’s warning concerning the dire consequences of not lowering carbon dioxide emissions—documented by reports of rising temperatures, extreme weather events, and waves of wildfires in many regions—will hopefully convince policy makers that the effects of climate change are occurring now and are not something that will happen in the distant future. It might also spur them to respond in a more urgent and meaningful manner at the present time. Above all, an international assessment scheme for climate reparations based on criteria linked to responsibility for global climate change, as we recommend here, combined with high-visibility reporting on whether each country has made its rightful contributions, would likely provide greater motivation and accountability.

Therefore, we propose the establishment of a Global Climate Reparations Fund (GCRF) that would operate more consistently within human rights and equity principles and have a substantially more robust budget. The main goals of the envisioned GCRF would be to provide compensation for damages inflicted by climate change on low-income countries and small island states. This assistance would apply to those countries that have been or are being threatened by global climate change, in accordance with the level of loss and damages already experienced or those damages that are projected in the near term. Some middle-income countries confronting climate-induced problems, such as severe loss of water resources and other climate-related calamities, would also qualify for technical and financial assistance.

We anticipate that the proposed GCRF would be more successful than the GCF in raising climate-related funds for several reasons. As noted above, the worsening climate crisis and the warnings of expert bodies of a dire future provide an incentive to take more immediate action. The current plight of small island states and coastal communities provides additional motivation for the global community to initiate a joint response much more urgently. Also, the issue of reparations for past abuses and harms has received considerable currency historically and in recent years for several different purposes. Some well-known examples are financial payments made by the German government to Holocaust victims and their families beginning in 1952 through payments to the government of Israel; the Canadian government’s compensation in 2019 to Indigenous persons who were forcibly removed from their families and made to attend Indian residential schools to assimilate them into white society; and the US government’s payments in 1988 to Japanese Americans interned during World War II. In addition, several of the transitional justice commissions established in countries experiencing patterns of severe human rights abuses, violence, and conflict have gone beyond efforts to document the perpetrators to recommend some form of recompense to victims. Currently, the question of reparations for the labor of enslaved Black Africans is being discussed in the United States, including among several city governments and universities that have made financial commitments to provide long-deferred reparations for that purpose. 42 As mentioned above, we believe that framing contributions to a reparations fund as an ethical and human rights obligation is more likely to engender a successful monetary response than the GCF’s more technically related approach. Further, fundraising seems more likely to be effective if the contributions are assessed on the basis of formulaic criteria linked to responsibility for global climate change, as we recommend here.

We recommend that the GCRF be headquartered in Geneva, where it could operate as an innovative kind of Special Procedures mechanism under the Human Rights Council. This would emphasize that climate reparation is a human rights issue, with the fund’s collection and distribution of resources, as well as its operating procedures, determined by human rights principles. Like other Special Procedures expert working groups, its members would be appointed by the Human Rights Council, and it would issue reports to be reviewed by the council at least once a year. The role of this working group would be to make major decisions about priorities in countries receiving funding and to oversee operations and funding commitments.

What we have in mind is to model the operation of the GCRF after the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, often referred to as the Global Fund. The Global Fund was independently established in 2002, with administrative offices based in Geneva. 43 Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the Global Fund raised and invested some US$4 billion annually in grants to support programs and projects submitted by applicant countries. 44 Hopefully, the proposed GCRF would handle an even larger portfolio of funding.

Similar to the Global Fund, the GCRF would have a country-centered partnership model of shared governance that incorporates key stakeholders. We envision that it would provide funding on a priority basis to countries affected by climate change, with the use of the funds being determined by the recipient countries. In-kind and technical assistance could be provided if requested.

At present, the Global Fund has a secretariat to conduct day-to-day operations, oversee fundraising, and provide support for program implementation under the aegis of a broadly representative board. It operates through five subcommittees focusing on strategy development, governance oversight, commitment of financial resources, assessment of organizational performance, and resource mobilization and advocacy. 45 The proposed GCRF may need a somewhat similar structure, with working groups appointed by the Human Rights Council, which would serve as a governing body in order to make key policy decisions and oversee the distribution of funds.

Climate reparations financing

Consistent with Henry Shue’s first principle of equity, we propose that the funding for climate reparations come from the countries and private corporations most responsible historically for the CO 2 emissions that have caused the present climate crisis, along with the countries contributing the highest current levels of emissions that are intensifying climate change. Reflecting Shue’s second principle of equity, these countries and corporations also have the greatest means to do so. 46 In line with Shue’s third principle, this funding scheme for climate reparations would avoid making those who are already worst off even worse off. For this reason, it would not be appropriate to impose reparations charges on low-income countries. We would leave the precise formula as to how to levy these sources of funding to the leaders of the GCRF.

As seen in Table 2 , the United States (29%), European Union countries (22%), and China (12.7%) account for the largest cumulative amount of atmospheric CO 2 emissions since the start of the industrial age in the mid-eighteenth century. Therefore, we anticipate that these three would be a major source of climate reparations financing, with the funds levied in accordance with their overall historical contributions to atmospheric emissions. Russia, Japan, and India are also among the top six CO 2 emitters historically, but on a much smaller scale, and would be levied proportionately less in their contributions to climate reparations.

Table 1 lists those countries most responsible for current annual emissions of CO 2 . China, with 9.5 billion metric tons, is by far the leading emitter, contributing more than twice the amount as the United States, which is in second place. The other countries in the top 10 are India, the Russian Federation, Japan, Germany, South Korea, Iran, Canada, and Indonesia. If the countries of the European Union were listed as a group, they would most likely be the third-largest source of annual CO 2 emissions.

Table 3 lists the per capita atmospheric annual CO 2 emissions for 2018, the most recent year for which data are available. Unfortunately, these data do not provide a cumulative total for the countries in the European Union, as does Table 2 on largest historical emitters of atmospheric CO 2 . Given the major differences in countries’ populations, it is important to consider per capita emissions so that large-population middle-income countries such as China and India are not unduly penalized. In Table 3 , the order of responsibility for current emissions is quite different from the order in Table 2 on largest historical emitters. The 10 highest per capita atmospheric emitters are Saudi Arabia, Kazakhstan, Australia, the United States, Canada, South Korea, the Russian Federation, Japan, Germany, and Poland. We believe that these countries, particularly those near the top of the list, should also be major contributors to climate reparations funding.

In addition to imposing climate reparations based on countries’ historical emissions, we propose levying reparations in accordance with countries’ current levels of emissions. In this regard, we propose that a scheme of global carbon taxation or other financial contribution be levied in accordance with each country’s current annual total CO 2 emission levels (see Table 1 ), balanced with current per capita emissions (see Table 3 ). This dual source would complement the levy based on countries’ historical emissions (see Table 2 ). We think that such a measure is appropriate for assessing climate reparations because, as noted above, countries with large populations should not be unduly penalized for their numbers. A country’s total annual CO 2 emissions are also relevant for assessing climate reparations since this figure reflects public policies that result in excessive energy consumption, including both a lack of initiatives to reduce per capita emissions and decisions about the kind of energy sources to promote. Here, the fact that China is currently the biggest annual CO 2 emitter (9.5 billion metric tons) is due both to its population size and to its continuous construction of coal-fired power plants—currently outnumbering those in the rest of the world combined—in order to drive its economy. 47 The United States is in second place (4.9 billion metric tons), followed by India, Russia, Japan, Germany, South Korea, Iran, Canada, and Indonesia. The imposition of a global carbon tax would provide additional financial resources to the climate reparations fund, while encouraging countries to lower their CO 2 emissions by cutting their fossil fuel consumption.

Major corporate contributors to CO 2 emissions in the past 50 years should also be an important source of funding. Data compiled by the Climate Accountability Institute reveal that 20 private corporations have contributed over one-third of all energy-related carbon dioxide and methane emissions worldwide since 1965. Many of them also previously played a major role in financing campaigns promoting false and misleading information that climate change was not occurring, followed by campaigns claiming that even if it were, CO 2 emissions were not responsible. Twelve of the top 20 companies are state-owned entities, with Saudi Aramco topping the list. Other major contributors are Chevron (United States), Gazprom (Russia), ExxonMobil (United States), BP (United Kingdom), and Shell (the Netherlands). 48 Just as the countries mentioned above, these corporate giants should be required to donate generously to the climate reparations fund. Their claim that they were not directly responsible for how the petroleum and other fossil fuel products they extracted, transported, and marketed were used by consumers is a spurious argument, especially since their continual denial of global warming over the past half century has helped delay the global response to climate change. 49

Dealing in depth with the complex subject of climate-related migrations that will inevitably occur in a warming planet is beyond the scope of this paper, but responding to the forced displacement of large numbers of people due to the impacts of climate change will need to become yet another prong of climate reparations. The major international initiatives to assist with the impact of climate change envisioned here, if adopted, would help reduce the level of migration. However, they would not eliminate this challenge, since the international environmental refugee problem has already begun and will only grow in future years. In a recent article on this subject, the authors expressed their concern in fairly stark terms, anticipating that over the next 30 years, the global climate crisis will displace more than 140 million people within their own countries and drive many more across national borders. 50 The question of how to deal with the growing challenge of “climate refugees” is a greatly troubling one for which no easy solutions exist at present. Nevertheless, the countries whose emissions played the largest role in contributing to climate change should also bear the greatest responsibility in addressing the challenge, whether that be by financing resettlement programs or accepting refugees within their borders, or both.

The current climate crisis looms as one of the greatest challenges that humanity has ever faced. What makes it even more disturbing is the unequal nature of its adverse impacts, which fall heavily on those least responsible and most vulnerable. These populations are also unable to protect themselves from the disastrous consequences of climate change and global warming in the near term. It is debatable whether the world will meet the goal of the Paris Climate Agreement of limiting global temperature to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. This failure is likely to have increasingly disastrous consequences for many low-income countries. In recent years, the development of a conceptual framework for climate reparations has gained greater interest. 51 However, the means to achieve such an objective has remained elusive. It is doubtful that present-day mitigation and renewable energy programs alone in high-income countries will soften the blow of climate-related impacts on low-income countries in the future. It is therefore incumbent on policy makers to prepare for a series of worst-case scenarios in low-income countries and island states, such as those related to sea level rise, extreme weather events, water scarcity, loss of agricultural productivity, and vector-borne diseases. Financing adaptation programs and building resilience should be given the highest priority for most low-income countries. The assessment of reparation funds to enable these countries to do so should be based on responsibility for past carbon dioxide emissions, along with a carbon tax imposed on current annual emissions of countries and private corporate entities.

In the recently concluded COP26 meeting held in Glasgow, United Kingdom (October 31–November 13, 2021), the question of climate reparations to countries most affected by the impacts of climate change was prominently raised. While expressing disappointment that the previous goal of US$100 billion per year by 2020 had not been met, representatives at the meeting approved doubling such financial assistance for climate change adaptation by 2025. On a more controversial topic, funding for climate-related “loss and damage” currently suffered by low-income countries was acknowledged for the first time (in article VI of the final draft document), calling for “dialogue among parties, relevant organizations, and stakeholders to discuss the arrangements for the funding of activities.” 52

At present, an effective international financial mechanism is not in place to solicit and administer climate reparations funds to low-income countries in a timely manner. In our opinion, raising the funds and distributing climate-related reparations should be administered by a newly instituted agency overseen by the Human Rights Council, in conjunction with other multilateral agencies, thereby linking reparations to human rights standards, including equity, transparency, and accountability. These should be the chief objectives in establishing a human rights-oriented and well-funded Global Climate Reparations Fund.

We use cookies. Read more about them in our Privacy Policy .

- Accept site cookies

- Reject site cookies

A first global mapping of rights-based climate litigation reveals a need to explore just transition cases in more depth

Annalisa Savaresi and Joana Setzer have identified more than 100 climate cases that rely on human rights arguments to promote action on climate change – but also a growing body of ‘just transition’ cases that are questioning the distribution of the benefits and burdens that the drive to net-zero is creating. To better understand how the transition can be inclusive and respectful of human rights, this new frontier of litigation requires deeper exploration.

To develop a clearer and more comprehensive appreciation of the role of human rights law and remedies in the climate crisis, there is a need to consider all rights-based litigation concerning climate action. Yet to date, a focus on rights-based litigation that aligns with climate mitigation and adaptation objectives has dominated in the academic literature. We have previously referred to these cases as ‘near side of the moon’ cases , as they have become increasingly well-documented. Meanwhile, details of climate litigation that does not align with mitigation or adaptation have been neither systematically collected nor analysed – these are what we call ‘far side of the moon’ cases and they represent a significant gap in knowledge that requires further research.

The near side of the moon – cases aligned with climate action

We analysed 112 cases that relied in whole or in part on human rights arguments, brought up to May 2021. Comparing their characteristics with trends in general climate litigation reveals some striking peculiarities in rights-based climate cases.

Geographically , rights-based climate cases have been predominantly filed in Europe, followed by North America, Latin America, the Asia-Pacific and Africa. Most cases were recorded in regions endowed with regional human rights bodies that historically have been sympathetic towards the use of human rights complaints to pursue environmental objectives. Roughly 13 per cent of rights-based complaints have been lodged before international and regional human rights bodies. In general, most climate litigation cases have been brought in the US, followed by Europe and the Asia-Pacific, and only a very small number of the total number of climate cases (0.7 per cent) were filed before international bodies.

Chronologically , rights-based climate litigation is a recent phenomenon, featuring more prominently since the adoption of the Paris Agreement in 2015. Many of the cases are thus still pending. Of the 57 that have been decided, 56 per cent have found against applicants and 44 per cent in their favour, and not all of the court victories have been attributable to successful human rights arguments.

Applicants in rights-based climate litigation are typically individuals and groups – the main rights-bearers in law. This stands in contrast with general climate litigation, where corporate actors have historically initiated most climate cases, challenging regulations or the withdrawal of licences and permits. D efendants in climate cases are typically states and public authorities, who are the primary duty-bearers in human rights law. However, a small but rapidly increasing number of rights-based climate cases are specifically targeting corporations, asking domestic courts and non-judicial bodies to interpret corporate due diligence obligations in light of human rights law and of the temperature goal enshrined in the Paris Agreement. These cases have attracted considerable attention, due to their ground-breaking nature and potentially revolutionary impacts .

What kinds of rights and strategies?

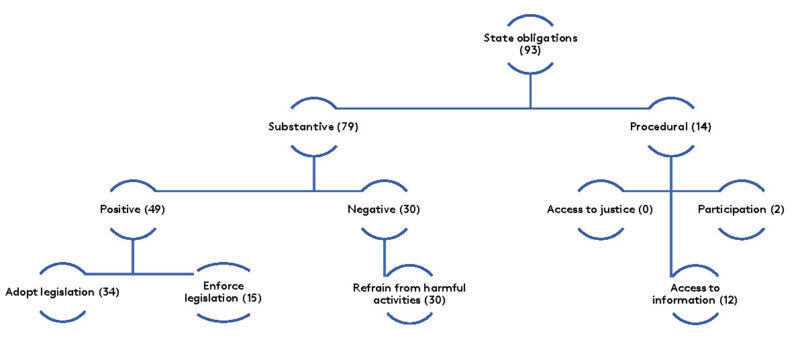

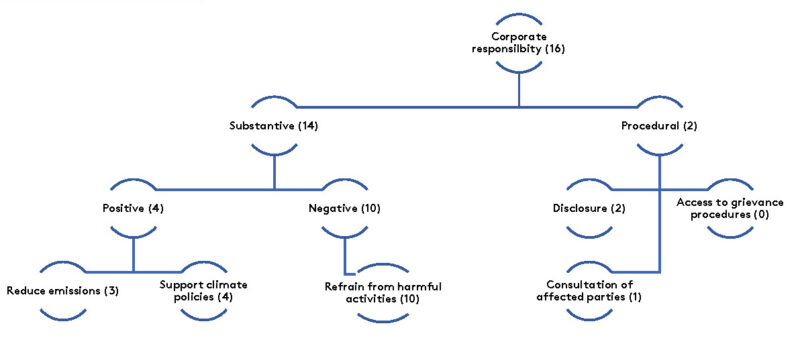

We have also identified the types of human rights most frequently invoked in rights-based climate cases against states (Figure 1) and against corporate actors (Figure 2).

Applicants in these cases often opt for a classic strategy in rights-based litigation: a demand for the fulfilment of substantive positive or negative obligation from states. Fewer cases rely on procedural human rights obligations.

Substantive positive obligations include asking states to take legislative and/or executive action to tackle environmental degradation that affects the enjoyment of human rights (e.g. Urgenda for mitigation and Torres Strait Islanders on adaptation) or demanding the enforcement of legislation (e.g. Leghari ). In the case of Institution of Amazonian Studies v. Brazil applicants also requested the legal recognition of a newly articulated human right – the right to a stable climate system.

Substantive negative obligations include refraining from authorising activities or adopting policies leading to environmental impacts that violate the enjoyment of human rights (e.g. Nature and Youth and Greenpeace Norway v. the Government of Norway ).

In rights-based climate cases brought against corporations, applicants typically argue that corporate actors have a positive duty to reduce emissions (e.g. Milieudefensie ) or a positive duty to support, rather than oppose, climate policies and their enforcement (e.g. Carbon Majors inquiry ). Applicants have also relied (sometimes simultaneously) on corporations’ negative duty to refrain from activities causing harm (the Carbon Majors inquiry being an example again here). Complaints relying on corporate procedural duties are scarce.

The far side of the moon – ‘just transition litigation’

There is a significant gap in our understanding of lawsuits in which human rights law and remedies are used to challenge measures and projects designed to deliver climate change adaptation and/or mitigation. In our paper we call these lawsuits ‘just transition litigation’, which we define as cases that rely in whole or in part on human rights arguments to question the distribution of the benefits and burdens of the transition away from fossil fuels and towards net-zero emissions.

Just transition litigation may marginally overlap with so-called ‘ anti-regulatory ’, ‘ defensive ’ or ‘ anti ’ climate litigation, but should be regarded as a self-standing type of litigation. Just transition litigation does not object to climate action per se , but rather to the way in which it is carried out and/or to its impact on the enjoyment of human rights. Examples include litigation targeting corporate actors and states for breaches of human rights obligations associated with the rights of Indigenous Peoples (e.g. ProDESK v. EDF ). International human rights bodies have also received complaints challenging measures to reduce forest emissions and the construction of hydroelectric dams , alleging breaches of human rights in respect to culture, food, water and the rights of Indigenous Peoples, for example.

Applicants have also alleged breaches of the right to access to justice in the authorisation of wind farms (e.g. Fägerskiöld v. Sweden ). Both the UK and the EU have been found to have breached their obligations under the Aarhus Convention for having adopted renewable energy laws and policies without adequate public participation.

This phenomenon of opposition to climate action on human rights grounds – which other scholars and databases have already identified but without analysing it systematically – is hardly a surprise. Fossil fuel-based economies may have created winners and losers but changing the status quo entails striking new equilibria between competing societal interests .Here, the notion of a ‘just transition’ has been invoked to highlight that the benefits of decarbonisation should be shared , and that those who stand to lose should be supported.

The rise of just transition litigation emphasises the importance of safeguarding both procedural and substantive rights, and of protecting individuals and groups from the arbitrary and unjust decisions of governments and corporations. Greater understanding of this litigation is necessary to appreciate the tensions associated with a transition towards zero carbon societies, and the ways in which they may be resolved through the adoption of a rights-based approach to climate change decision-making – as advocated for in the recent decision of the Human Rights Council to create a UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and Climate Change.

Mapping the whole of the moon

As both climate legislation and litigation mature, an increasing number of rights-based litigation cases will focus on the enforcement of extant climate legislation and on the protection of procedural rights. Future human rights law and remedies will continue to be used to propel the energy transition away from fossil fuels, while also protecting those most affected by it. There is a need to explore the new frontier of just transition litigation to better understand how governments and corporations can address climate change and deliver net-zero emissions, and enact an energy transition that is inclusive and in line with human rights.

Webinar on 30 March 2022: This commentary summarises the main findings of the authors’ contribution to a special issue of the Journal of Human Rights and the Environment on rights-based climate litigation published on 28 March 2022. The special issue is being launched by the Center for Climate Change, Energy and Environmental Law (CCEEL) at the Law School of the University of Eastern Finland on 30 March, during which the authors will present their paper. Register here to join the webinar.

Annalisa Savaresi is an Associate Professor, Center for Climate Change, Energy and Environmental Law , University of Eastern Finlandand Joana Setzer is an Assistant Professorial Research Fellow in Governance and Legislation at the Grantham Research Institute. The views in this commentary are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Grantham Research Institute.

Sign up to our newsletter

Loading metrics

Open Access

Climate change and security research: Conflict, securitisation and human agency

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation School of Agriculture, Policy and Development, University of Reading, Reading, United Kingdom

- Alex Arnall

Published: March 2, 2023

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pclm.0000072

- Reader Comments

Climate change has increasingly been understood as a security problem by researchers, policymakers and media commentators. This paper reviews two strands of work that have been central to the development of this understanding–namely 1) the links between global heating and violent conflict and 2) the securitisation of climate change–before outlining an agency-oriented perspective on the climate-security nexus. While providing sophisticated analyses of the connections between climate change and security, both the conflict and securitisation strands have encountered several epistemological challenges. I argue that the climate security concept can be revitalised in a progressive manner if a more dynamic, relational approach to understanding security is taken. Such an approach recognises people’s everyday capacities in managing their own safety as well as the security challenges involved in responding to a continually evolving threat such as climate change.

Citation: Arnall A (2023) Climate change and security research: Conflict, securitisation and human agency. PLOS Clim 2(3): e0000072. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pclm.0000072

Editor: Anamika Barua, Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati, INDIA

Copyright: © 2023 Alex Arnall. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, climate change has increasingly been understood as a security problem by a range of political actors, media commentators and researchers [ 1 ]. Part of a long-standing convention of securitising non-traditional threats, such as HIV/AIDS and transnational crime, that began in the late 1990s, climate change has, in the last 20 years, been lifted to the realms of ‘high politics’, such as those of the UN General Assembly and US military establishment. In general, there is consensus among researchers that climate change has the potential to undermine the securities of nation states and people. In addition, the existing insecurities that these entities experience (for example, due to political conflict or lack of economic opportunity) might be worsened by global heating [ 2 ]. However, how security is understood, the pathways and mechanisms via which it is connected to climate change, and what climate security (or lack of it) means for affected populations are issues of ongoing contention.

One of the complexities of these debates is that security means different things to different people [ 3 ] and organisations [ 4 ]. In general, security is defined as the condition of being free from danger or threat, either at a personal or collective level [ 5 ]. Threats can be real or imagined, imminent or in the future. Some researchers differentiate between ‘hard security’, referring to the actions of the military and related institutions, and ‘soft security’, which concerns how people access resources such as food and water [ 6 ]. Most common in climate change debates, however, is the division of security into ‘state security’ and ‘human security’ [ 7 ]. State security involves the capacities of countries “to manage climate-related threats to safeguard their sovereignty, military strength, and power in the international system” [ 8 , p.3]. Climate change risks undermining these capacities, threatening the opportunities and services that help people to sustain their lives and livelihoods. In the most extreme cases, climate change threatens the survival of entire countries, such as small island states located in the Pacific and Indian Oceans [ 9 ]. In contrast, human security “covers a variety of concerns ranging from the economy, the environment, the community, to health, the body and personal safety” [ 3 , p.92]. Human security does not just refer to physical needs but also to social and psychological ones, as well as the symbolic and cultural elements of identity [ 10 ].

The growth of interest in climate security can be traced back to wider concerns about environmental security that emerged in the 1980s, anxieties that were encapsulated by the World Commission on Environment and Development’s 1987 publication Our Common Future [ 11 ]. These concerns were accompanied by the reorientation of world powers at the end of the Cold War and the threat of global environmental change replacing the immediate dangers of nuclear war [ 12 ]. Since this time, climate change and security work has gained traction along two main strands. The first strand, according to Oels [ 13 ], concerns the risk of catastrophic climate change due to a failure of the international community to keep global heating below +2 degrees Celsius. Interest in this strand peaked in 2007 when the security implications of climate change were debated by the UN Security Council [ 14 , 15 ] and examined in reports produced by the US and UK security establishments [ 16 ]. The second strand, which emerged in the 1990s, concerns human security and, as outlined above, places greater emphasis on the wellbeing of people than on the security of states [ 17 ]. The human security strand was initially advanced through the UNDP’s 1994 Human Development Report [ 18 ] and culminated in the production of the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report in 2014, which contained an entire chapter on human security [ 19 ].

In the last 20 years, work along these two strands has resulted in a plethora of academic papers and government reports. It is not my intention in this present paper, however, to provide a broad review of all studies produced to date. Instead, my approach is to highlight two areas of climate security research that have received considerable attention in recent years and to discuss some of the challenges that these bodies of work have encountered. The first area concerns the possibility of global heating leading to intercommunal or interstate conflict. Epistemologically, researchers in this area take a positivist approach, viewing human or state security as a pre-existing condition that is capable of being located and measured through empirical examination. However, as I will argue, while this approach has been a focus of considerable scientific endeavour in recent years, there is as yet little consensus among researchers on the extent to which climate change is leading (or will lead) to changes in human propensity to violence [ 20 ], with some expressing doubts that a direct link can, or should, be established at all [ 21 ].

In contrast to positivism, researchers working in the second area take a constructivist approach to understanding the climate-security nexus, seeking to explain how security problems and solutions are established, represented and acted upon in society and towards what purposes. This approach is exemplified by the so-called ‘Copenhagen School’, which focuses on the discursive links between security threats and extreme remedies and countermeasures. Under this School, researchers claim that climate change has been ‘securitised’, which risks producing a series of perverse outcomes including the militarisation, technicalisation or depoliticization of climate change policy. However, I will argue that, despite the influence of this critique in academic circles, the effects of securitisation on the policies and activities of national governments have been limited to date. In other words, by focusing on the realm of the representational, the securitisation field has made little connection with what governments and organisations are doing ‘on the ground’.

With these limitations in mind, I then go on to suggest a third approach, one that engages with the idea of human agency, or “capacity to make a difference” [ 22 , p.14], in climate change and security debates. This approach emphasises that the conditions of security and insecurity are not static but rather relational, negotiated and historically structured. It also draws attention to people’s day-to-day capabilities in managing their own climate securities while recognising the challenges of negotiating intersectionality in the context of a continually evolving threat like climate change. In advancing these ideas, I hope to develop a more dynamic approach to climate security debates than has been the case to date. The next section considers scientific efforts to establish an empirical link between climate and human conflict followed by consideration of the Copenhagen School’s approach to climate security in section 3. Section 4 introduces key ideas concerning climate security and human agency, and section 5 provides the conclusion.

2. Connecting climate change and conflict

Researchers have proposed several theoretical causal mechanisms between climate change, security and conflict in recent years. Barnett [ 2 ], for example, suggested that political scale, the nature of governance within countries, and scarcity or abundance of natural resources are three key influencers on the likelihood of conflict emerging as a result of climate change. Similarly, Seter [ 23 ] identified three factors–economic hardship, resource levels and migration driven by economic change–connecting climate change and conflict, and Bretthauer [ 24 ] suggested that agricultural dependence and low levels of education increase the likelihood of armed conflict resulting from global heating. Other researchers have emphasised that, while direct links between climate change and conflict exist, there are multiple pathways between these “ranging from agriculture and economic productivity or demographic pressure to psychological mechanisms” [ 25 , p. 241]. This means that, rather than a ‘one scenario fits all’ approach, people’s particular experiences of environmental change in the context of wider social structures and processes are likely to create individual paths to insecurity [ 16 ]. Researchers have also argued that climate change acts as a ‘threat multiplier’ rather than a direct cause of human insecurity and violence [ 10 ]. In other words, regions already vulnerable to violent conflict due to low levels of human development are similarly vulnerable to the effects of climate change [ 26 , 27 ]. This latter argument raises the prospect of ‘double exposure’ to climate change and conflict occurring among populations [ 28 ].

Together, these studies suggest that numerous connections exist between climate change, environmental degradation and conflict. However, finding empirical evidence of these connections has been challenging. While long-term historical studies have established a measurable relationship between climatic change and large-scale human crises [ 29 , 30 ], most work looking at change over shorter timeframes has been inconclusive, with “not yet much evidence for climate change as an important driver of conflict” [ 31 , p.7]. There are some examples where such an effect has been determined, although these have tended to be extreme or isolated examples. For example, in their study of the causation of conflict and displacement in East Africa over the last 50 years, Owain and Maslin [ 32 , p.1] found that climate variations played little role, although they did conclude that “severe droughts were a contributing driver of refugees crossing international borders”. Fjeld and von Uexkull [ 33 , p.444] were similarly tentative, concluding that, in certain conditions, there is “some evidence that the effect of rainfall shortages on the risk of communal conflict is amplified in regions inhabited by politically excluded ethno-political groups”. And Abel et al. [ 25 , p.246], utilising data on refugee flows between 2006 and 2015 across 157 countries, found little evidence for a “robust link between climatic shocks, conflict and asylum seeking for the full period”. The only exception, the authors noted, is evidence of a causal link between 2010 and 2012 when “global refugee flow dynamics were dominated by asylum seekers originating from Syria and countries affected by the Arab spring, as well as flows related to war episodes in Sub-Saharan Africa”. In these studies, the main barrier to establishing a clear climate-security connection has been the very wide range of research designs, scales of analysis and case studies undertaken [ 25 ] as well as the “numerous intervening economic and political factors that determine adaptation capacity” [ 34 , p.1]. Taken together, these factors complicate scientific efforts.

Given these challenges, there have been calls in the literature for more research to uncover direct pathways and intermediate factors connecting climate change and conflict. As pointed out by von Uexkull and Buhaug [ 35 ], techniques of analysis and disaggregation in the climate security field are becoming more sophisticated all the time, meaning that such connections might become more demonstrable in the future. Nonetheless, other researchers have expressed discomfort with the general direction of this work, suggesting that “some studies in environmental security are in danger of promulgating a modern form of environmental determinism by suggesting that climate conditions directly and dominantly influence the propensity for violence among individuals, communities and states” [ 36 , p.76]. Similarly, some researchers have questioned the frequent portrayal of people exposed to climate change and conflict as ‘threats’ to Western countries [ 37 , 38 ]. Inevitably, any discussion of state and human security, whether linked to environmental change or not, will implicitly or explicitly involve the identification of ‘suspect communities’ that are more likely to become insecure and therefore subject to security measures to contain or manage them [ 39 ]. These concerns move the focus of debate away from seeing climate security and insecurity as empirically verifiable conditions towards consideration of how in/security is represented via discourse. This is the focus of the next section.

3. Securitisation of climate change

Researchers working on the securitisation of climate change seek to understand how the idea of climate security is constructed as a ‘matter of concern’, in whose interests this process operates, and the social, economic and political consequences for individuals and groups identified as security threats or problems. As outlined above, this body of work mainly draws upon the Copenhagen School of security studies, which highlights the risk of “discursive practices invoking (current or projected) climatic events as an existential threat, thereby justifying urgent measures in response” [ 40 , p.807]. These measures, in turn, may be exceptional or extraordinary in nature, including the build-up of military and police forces along national borders [ 6 ]. In this way, an essentially political problem concerning the distribution of costs and benefits of measures to tackle climate change becomes overwhelmed by “perverse responses that do not address the [root] causes of climate change and even position those affected most by it as threatening” [ 41 , p.46]. The securitisation of climate change, in other words, threatens to remove global heating from political debate while imposing an antagonistic approach that poses “a threat to the kind of peaceful international cooperation and development initiatives needed to respond equitably and effectively” [ 42 , p.234].

In this way, the Copenhagen School has presented the main challenge to those seeking to elevate climate security to the ‘high politics’ of the UN and other international bodies in an attempt to generate publicity and attention [ 43 ]. There is, however, debate over the degree to which the apocalyptic images frequently used in climate security debates have translated into ‘real world’ changes in government policy and practice [ 44 ]. This is because, as argued by Warner and Boas [ 45 ], the actors that are mobilising climate change as an existential threat have tended to advocate relatively mundane response measures rather than more exceptional ones, thereby relying “on solutions that are anchored in the present-day distribution of power and geopolitics” [ 10 , p.280] instead of addressing root causes [ 46 ]. According to Mason [40, p.808], this mundane approach is “designed to manage climate risks in a way that renders them less threatening to Western geopolitical and geo-economic interests” but is also grounded in “a depoliticised stance reflecting UN norms of neutrality and impartiality”. For example, Burnett and Mach [ 47 , p.2] cast doubt on whether the many climate risk reports and statements produced by the US Department of Defence in recent years “are regularly translated into institutionalized planning and decision-making”, limiting response measures to “selective integration” of climate considerations into previously established security indices and country plans. Similarly, Trombetta [ 48 , p.144] argued that the risk of climate-induced migration to the EU has “become subjected to the already existing European machinery of managing and controlling migration” that is consistent with the logic of governing human movement ‘from a distance’ [ 49 ].

An additional challenge for the securitisation of climate change argument is that, while climate security rhetoric has garnered considerable attention in recent decades, its prevalence and impact has been geographically uneven, often because the catastrophic scenarios presented by such rhetoric have been met with scepticism by some audiences [ 45 ]. In the main, it is the large multinational organisations located in the Global North that have adopted the language of climate security [ 4 ], especially the European Union [ 50 , 51 ]. In contrast, there has been a decline in the amount of securitising climate change language in some countries located in the Global South [ 12 ]. Boas [ 52 ], for example, documented how the Indian government rejected ‘alarmist’ ideas of climate security, dismissing them as a Western negotiating tactic designed to encourage more binding carbon mitigation targets. Similarly, von Lucke [ 53 ] argued that the securitisation of climate change in Mexico produced a limited effect on government policy due, in part, to the dominance of ‘hard’ security issues in the country, such as conflicts with drug cartels. In these cases, there is little consensus over what role, if any, intergovernmental organisations like the UN Security Council should adopt in encouraging the governments of developing countries to move climate security concerns higher up their political agendas [ 54 ]. Taken together, these studies cast doubt on the argument advanced by scholars that the securitisation of climate change is leading to extreme and exceptional measures.

4. Climate change, human security and agency

Both the positivist and constructivist approaches to understanding the climate change-security relationship outlined above underplay human agency, or the ways in which “individuals with different resources at their disposal (economic, cultural, political or environmental) are able to negotiate the more-or-less favourable circumstances into which they are born and raised” [ 5 ]. For example, Raleigh [ 36 , p.77] suggested that, “In arguing that communities directly or indirectly respond to increased temperatures by attacking their neighbours, competitors or the state, deterministic studies neglect the complex political calculus of governance, the agency of communities, and the multiple ways that people actually cope with challenging environmental conditions”. Most actors, therefore, are capable of exercising some kind of power [ 22 ]–of processing social experience and devising ways of coping with climate insecurity–in ways that do not resort to violence, even under the most difficult of circumstances [ 55 ]. Moreover, McDonald [ 41 , p.47] argued that, while being “explicit about the pathologies associated with ‘securitization’”, the Copenhagen School has fallen short in providing clear ideas about human agency. This ambiguity, in turn, “serves to reinforce international power inequalities and renders criteria for intervention by powerful states and international institutions less transparent and less accountable” [ 56 , p.113]. With these limitations in mind, the aim of this section is to outline an agency-oriented perspective on climate security. As set out in section 1, this perspective emphasises the relationality of security and insecurity over time and between different places as well as the centrality of people’s own everyday security practices. These dimensions are explained in greater depth below.

Writing about human security in the Caribbean, Noxolo [ 57 ] makes the important point that security and insecurity are deeply located, historically grounded and constantly produced and reproduced in relation to one another. Security and insecurity, therefore, are not new, future-oriented concepts that have arisen solely in the context of climate change but, instead, are conditions that have been experienced by marginalised individuals and groups over time. This is evident, for example, when considering the effects of climate change on tribal communities in the United States [ 58 ] or on groups that have been repeatedly subject to population relocation [ 59 ]. Moreover, the distribution and effects of security and insecurity are geographically unequal. Indeed, Philo [ 60 , p.1] described the highly uneven geographies of security and insecurity as “entangled” across networks existing at a range of spatial scales, from the local to the global. In other words, the processes through which security and insecurity come about in different places are closely linked, and the measures undertaken by some groups to ensure their own securities potentially undermine or trade off the securities of others. For example, with regard to the risk of theft and burglary, Valverde [ 61 , p.13] pointed out that “the private security guard who is concerned to protect only one building will be likely to displace disorderly people to the next block”. Similarly, an intervention carried out by one group to secure their livelihoods in a situation of prolonged drought–such as farmers extracting water from a river to irrigate their crops–might diminish the availability of this resource for others downstream, thus risking the latter group’s security.

More broadly, trade-offs can emerge at the level of the nation state between, for example, imperatives to ensure national energy security [ 62 ] and people’s human securities in accessing agricultural land and water [ 63 ]. Hydroelectric dams, for example, are frequently promoted as sources of ‘green energy’ that contribute to climate change mitigation efforts and that help rapidly developing countries secure a much-needed supply of electricity [ 64 ]. However, as has been widely documented by researchers and activists, such dams are also often a source of insecurity for local populations, many of whom are displaced by construction activities, infrastructure and reservoirs, losing access to valuable natural resources in the process [ 65 ]. Security trade-offs in climate change responses can also occur in relation to planned adaptation or resilience-building initiatives undertaken by governments or development agencies. For example, the resettlement of vulnerable populations out of areas deemed to be no longer safe due to weather-related extremes can lower direct exposure to environmental shocks and stresses but can also lead to communities being subjected to new forms of danger that risk further diminishing their climate securities. To illustrate, Arnall [ 66 ], working in Mozambique, showed how the government-led relocation of small scale farmers out of river valleys to nearby areas of higher elevation land helped to protect farmers against large-scale floods. However, relocation also increased farmer exposure to drought, with the outcome that many vulnerable groups in resettled communities were compelled to return to live in floodplains in order to continue their farming activities. Returning in this manner increased their food and income securities but also increased the risks of physical harms from floods.