You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

- Exhibitions

- Visit and Contact

- UCD Library

- Current Students

- News & Opinion

- Staff Directory

- UCD Connect

Harvard Style Guide: Images or photographs

- Introduction

- Harvard Tutorial

- In-text citations

- Book with one author

- Book with two or three authors

- Book with four or more authors

- Book with a corporate author

- Book with editor

- Chapter in an edited book

- Translated book

- Translated ancient texts

- Print journal article, one author

- Print journal article, two or three authors

- Print journal article, four or more authors

- eJournal article

- Journal article ePublication (ahead of print)

- Secondary sources

- Generative AI

- Images or photographs

- Lectures/ presentations

- Film/ television

- YouTube Film or Talk

- Music/ audio

- Encyclopaedia and dictionaries

- Email communication

- Conferences

- Official publications

- Book reviews

- Case studies

- Group or individual assignments

- Legal Cases (Law Reports)

- No date of publication

- Personal communications

- Repository item

- Citing same author, multiple works, same year

Back to Academic Integrity guide

Images or photographs (print)

Reference : Photographer/Creator Last name, Initial(s). (Year) Title of image/photograph [Photograph/Image]. Place of publication: Publisher.

Example : O’Meara, S. (2014) Orchid [Photograph]. Co. Clare: Collins Press.

In-Text-Citation :

- Author(s) Last name (Year)

- (Authors(s) Last name, Year)

- O’Meara (2014) shows a perfect example of the epipactis atrorubens.

- The velvety red of the epipactis atrorubens is captured beautifully in the above image (O’Meara, 2014)....

Still unsure what in-text citation and referencing mean? Check here .

Still unsure why you need to reference all this information? Check here .

Images or photographs (online)

Reference : Photographer/Creator Last name, Initial(s). (Year) Title of image/photograph . Available at: URL (Accessed Day Month Year).

Example : O’Meara, S. (2014) Orchid . Available at: www.theburrenorchidcollection.ie (Accessed 3 February 2014).

As detailed for Images/Photographs (print).

- << Previous: Podcast

- Next: Lectures/ presentations >>

- Last Updated: Mar 12, 2024 8:58 AM

- URL: https://libguides.ucd.ie/harvardstyle

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Cite an Online Image in Harvard Referencing

3-minute read

- 5th August 2020

Want to use an image you found online in your academic writing ? Read our guide below and find out how to cite an online image using Harvard referencing , including the in-text citations and reference list entry.

To cite an image found online in Harvard referencing, you need to give the creator’s surname and the year of creation in the in-text citations :

This picture depicts George V and Nicholas II in Berlin (Sandau, 1913).

If you name the creator in the main text, though, you only need to include the date in brackets. For example:

Sandau’s (1913) photograph depicts George V and Nicholas II in Berlin.

You won’t always be able to find the creator or date for images you find online, though. In these cases, you’ll need to adapt the citation accordingly:

- If you cannot find an image’s creator, give its title in italics (if you can’t find the title either, use a short description of what the picture depicts).

- When the date is missing, use the abbreviation ‘n.d.’ (short for ‘no date’).

This might work in practice as follows:

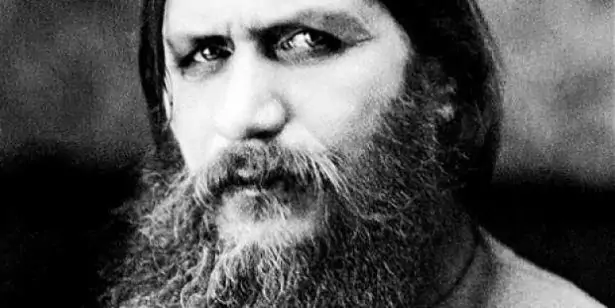

Rasputin was known for his piercing gaze ( Detail of Rasputin , n.d.).

Here, for instance, we give a description of the photo you can see below. And the reader would then use this description to look up the photo in the reference list, where you’ll provide full source information.

Online Images in a Harvard Reference List

The reference list format for an online image in Harvard referencing is:

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Creator surname, Initial. (year) Title of image , Collection (if applicable) [Online]. Available at URL (Accessed date).

So, for our first example above, the full reference would be:

Sandau, E. (1913) Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia (1868-1968), and King George V (1865-1936) , Royal Collection Trust [Online]. Available at https://www.mountainsandmegapixels.com/?lightbox=dataItem-kas62h851 (Accessed 4 March 2019).

As with citations, though, you’ll need to adapt the reference if you don’t have the creator’s name or year of production. The key points here are:

- When no creator name is available, use the image title (or a description) in its place. You will also use this to determine the position of the source in an alphabetical reference list.

- For images with no date, use ‘n.d.’ in place of the year.

Thus, we would reference the second example above as follows:

Detail of Rasputin (n.d.) [Online]. Available at http://www.referenced.co.uk/ten-historical-figures-who-died-unusual-deaths/ (Accessed 8 May 2020).

Harvard Variations and Proofreading

Harvard referencing is a style, not a system. Consequently, the exact format used for citations and references may vary. We’ve used the guidelines set out in the Open University’s guide to Harvard referencing [PDF] , but make sure to check your university’s style guide if you have one.

Whatever style of referencing you use, though, clarity and consistency are key. So, to make sure your academic writing is always error free, why not ask Proofed’s referencing experts to check your citations are all in order?

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Get help from a language expert. Try our proofreading services for free.

The 5 best ecommerce website design tools .

A visually appealing and user-friendly website is essential for success in today’s competitive ecommerce landscape....

The 7 Best Market Research Tools in 2024

Market research is the backbone of successful marketing strategies. To gain a competitive edge, businesses...

4-minute read

Google Patents: Tutorial and Guide

Google Patents is a valuable resource for anyone who wants to learn more about patents, whether...

How to Come Up With Newsletter Ideas

If used strategically, email can have a substantial impact on your business. In fact, according...

Free Online Peer Review Template

Having your writing peer-reviewed is a valuable process that can showcase the strengths and weaknesses...

How to Embed a Video in PowerPoint

Including a video in your PowerPoint presentation can make it more exciting and engaging. And...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Finding and referencing images: Referencing images

- Referencing images

- Finding images and videos

Introduction

In this guide, ' IMAGE ' is used to refer to any visual resource such as a diagram, graph, illustration, design, photograph, or video. They may be found in books, journals, reports, web pages, online video, DVDs and other kinds of media. This guide also refers to ‘ CREATOR ’. This could be an illustrator, photographer, author or organisation.

The examples are presented in Harvard (Bath) style and offer general guidelines on good practice. For essays, project reports, dissertations and theses, ask your School or Department which style they want you to use. Different referencing styles require the use of similar information but will be formatted differently. For more information on other referencing styles, visit our referencing guide .

Using images to illustrate or make clear the description and discussion in your text is useful, but it is important that you give due recognition to the work of other people that you present with your own. This will help to show the value of their work to your assignment and how your ideas fit with a wider body of academic knowledge.

It is just as important to properly cite and reference images as it is the journal articles, books and other information sources that you draw upon. If you do not, you could find yourself accused of plagiarism and/or copyright infringement.

Using images and copyright

For educational assignments it is sufficient to cite and reference any image used. If you publish your work in any way , including posting online, then you will need to follow copyright rules. It is your responsibility to find out whether, and in what ways, you are permitted to use an image in your coursework or publications. Please refer to our copyright guidance and ask for further assistance if you are unsure.

Some images are given limited rights for reuse by their creators. This is likely to be accompanied with a requirement to give recognition to their work and may limit the extent to which it can be modified. The ‘Creative Commons’ copyright licensing scheme offers creators a set of tools for telling people how they wish their work to be used. You can find out more about the different kinds of licence, and what they mean, on the organisation’s web pages .

What is a caption?

Any image that you use should be given a figure number and a brief description of what it is. Permission for use of an image in a published work should be acknowledged in the figure caption. Some organisations will require the permission statement to be given exactly as they specify. If they are required, permissions need to be stated in addition to the citing and referencing guidance given below.

Referencing images in PowerPoint slides

For a presentation you should include a brief citation under the image. Keep a reference list to hand (e.g. hidden slide) for questions. Making a public presentation or posting it online is publishing your work. You must include your references and observe permission and copyright rules.

Example of a caption

Figure 1. Library book. Reproduced with permission from: Rogers, T., 2015, University of Bath Library

Citing and referencing images

Citing images from a book or journal article.

If you wish to refer to images used in a book or journal, they are cited in the same way as text information , for example:

The functions and flow of genetic information within a plant cell can be visualised as a complex system (Campbell et al., 2015, pp. 282-283).

Campbell et al. (2015, pp. 282-283) have clearly illustrated how a plant cell functions.

If you were to include this example in an essay the caption and citation below the image would look similar to this:

Figure 7. The functions and flow of genetic information within a plant cell (Campbell et al., 2015, pp. 282-283).

The reference at the end of the work would be as recommended for a book reference in our general referencing guide .

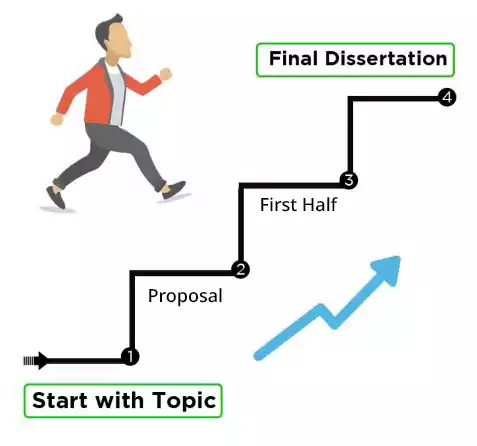

For a large piece of work such as a dissertation, thesis or report, a list of figures may be required at the front of the work after the contents page. Check with your department for information on specific requirements of your work.

Google images

When referencing an image found via Google you need to make sure that the information included in your reference relates to the original website that your search has found. Click on the image within the results to get to the original website and take your reference information from there. Take care to use credible sources with good quality information.

Citing and referencing images from a web page

If you use an image from a web page, blog or an online photograph gallery you should reference the individual image . Cite the image creator in the caption and year of publication. The creator may be different from the author of the web page or blog. They may be individual people or an organisation. Figure 2 below gives an example of an image with a corporate author:

List the image reference within your references list at the end of your work, using the format:

NASA, 2015. NASA astronaut Tim Kopra on Dec. 21 spacewalk [Online]. Washington: NASA. Available from: https://www.nasa.gov/image-feature/nasa-astronaut-tim-kopra-on-dec-21-spacewalk [Accessed 7 January 2015].

Wikipedia images

If you want to reference an image included in a Wikipedia article, double-click on the image to see all the information needed for your reference. This will open a new page containing information such as creator, image title, date and specific URL. The format should be:

Iliff, D., 2006. Royal Crescent in Bath, England - July 2006 [Online] . San Francisco: Wikimedia Foundation. Available from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Royal_Crescent_in_Bath,_England_-_July_2006.jpg [Accessed 7 January 2016].

Images and designs from exhibitions, museums or archives

If you want to reference an image or design that you have found in an exhibition, museum or archive, then you also need to observe copyright rules and reference the image correctly. The format is:

For example, if you want to reference an old black and white photograph from 1965 that is held in an archive at the University of Bath:

Bristol Region Building Record, 1965. Green Park House (since demolished), viewed from southwest [Photograph]. BRBR, D/877/1. Archives & Research Collections, University of Bath Library.

NB if you were to reproduce this archive image in your work, or any part of it (rather than just cite it), you would also need to note ‘© University of Bath Library’. This copyright note should be added to the image caption along with the citation.

Referencing your own images

If you take a photograph, you do not have to reference it. For sake of clarity you may want to add “Image by author” to the caption. If you create an original illustration or a diagram that you have produced from your own idea then you do not have to cite or reference them. If you generate an image from a graphics package, for example a molecular structure from chemistry drawing software, you do not need to cite the source of the image.

Referencing images that you adapt from elsewhere

If you use someone else’s work for an image then you must give them due credit. If you reproduce it by hand or using graphics software it is the same as if you printed, scanned or photocopied it. You must cite and reference the work as described in this guide. If the image is something that you have created in an earlier assignment or publication you need to reference earlier piece of work to avoid self-plagiarism. If you want to annotate information to improve upon, extend or change an existing image you must cite the original work. However, you would use the phrase ‘adapted from’ in your citation and reference the original work in your reference list.

AI generated images

If you have used an AI tool to generate an image you must acknowledge that tool as a source (see point 7 of the academic integrity statement ).

This content is not recoverable; it cannot be linked or retrieved. There is no published source that you can reference directly. Instead you would give an in-text, ‘personal communications’ citation , as described in part 15 of our 'Write a citation' guidance (from the Harvard Bath guide). This type of citation includes the author details followed by (pers. comm.) and the date of the communication.

For example, an image of a shark in a library generated with Craiyon with a ‘personal communications’ citation included in the image caption:

Figure 3. Shark in a library image generated using an AI tool (Craiyon, AI Image Generator (pers. comm.) 14 July 2022).

Online images and resources for your work

The library has compiled a list of useful audio-visual resources, including images, that can be used for essays or assignments. Visit the ' finding images and videos ' tab of this guide to find out more.

- Next: Finding images and videos >>

- Last Updated: Nov 6, 2023 3:07 PM

- URL: https://library.bath.ac.uk/images

- Jump to menu

- Student Home

- Accept your offer

- How to enrol

- Student ID card

- Set up your IT

- Orientation Week

- Fees & payment

- Academic calendar

- Special consideration

- Transcripts

- The Nucleus: Student Hub

- Referencing

- Essay writing

- Learning abroad & exchange

- Professional development & UNSW Advantage

- Employability

- Financial assistance

- International students

- Equitable learning

- Postgraduate research

- Health Service

- Events & activities

- Emergencies

- Volunteering

- Clubs and societies

- Accommodation

- Health services

- Sport and gym

- Arc student organisation

- Security on campus

- Maps of campus

- Careers portal

- Change password

How to Cite Images, Tables and Diagrams

The pages outlines examples of how to cite images, tables and diagrams using the Harvard Referencing method .

An image found online

In-text citations

Mention the image in the text and cite the author and date:

The cartoon by Frith (1968) describes ...

If the image has no named author, cite the full name and date of the image:

The map shows the Parish of Maroota during the 1840s (Map of the Parish of Maroota, County of Cumberland, District of Windsor 1840-1849)

List of References

Include information in the following order:

- author (if available)

- year produced (if available)

- title of image (or a description)

- Format and any details (if applicable)

- name and place of the sponsor of the source

- accessed day month year (the date you viewed/ downloaded the image)

- URL or Internet address (between pointed brackets).

Frith J 1968, From the rich man’s table, political cartoon by John Frith, Old Parliament House, Canberra, accessed 11 May 2007, <http: // www . oph.gov.au/frith/theherald-01.html>.

If there is no named author, put the image title first, followed by the date (if available):

Khafre pyramid from Khufu’s quarry 2007, digital photograph, Ancient Egypt Research Associates, accessed 2 August 2007, <http: // www . aeraweb.org/khufu_quarry.asp>.

Map of the Parish of Maroota, County of Cumberland, District of Windsor 1840-1849, digital image of cartographic material, National Library of Australia, accessed 13 April 2007, <http: // nla . gov.au/nla.map-f829>.

Online images/diagrams used as figures

Figures include diagrams, graphs, sketches, photographs and maps. If you are writing a report or an assignment where you include a visual as a figure, unless you have created it yourself, you must include a reference to the original source.

Figures should be numbered and labelled with captions. Captions should be simple and descriptive and be followed by an in-text citation. Figure captions should be directly under the image.

Cite the author and year in the figure caption:

Figure 1: Bloom's Cognitive Domain (Benitez 2012)

If you refer to the Figure in the text, also include a citation:

As can be seen from Figure 1 (Benitez 2012)

Provide full citation information:

Benitez J 2012, Blooms Cognitve Domain, digital image, ALIEM, accessed 2 August 2015, <https: // www . aliem.com/blooms-digital-taxonomy/>.

Online data in a table caption

In-text citation

If you reproduce or adapt table data found online you must include a citation. All tables should be numbered and table captions should be above the table.

Table 2: Agricultural water use, by state 2004-05 (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2006)

If you refer to the table in text, include a citation:

As indicated in Table 2, a total of 11 146 502 ML was used (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2006)

Include the name of the web page where the table data is found.

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2006, Water Use on Australian Farms , 2004-05, Cat. no. 4618.0, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, accessed 4 July 2007, <https: // www . abs.gov.au>.

FAQ and troubleshooting

Harvard referencing

- How to cite different sources

- How to cite references

- How to cite online/electronic sources

- Broadcast and other sources

- Citing images and tables

- FAQs and troubleshooting

- About this guide

- ^ More support

Study Hacks Workshops | All the hacks you need! 7 Feb – 10 Apr 2024

Hexamester 2: Library 101 Webinar 13 Mar 2024

- How it works

How to Cite an Image in Harvard Style?

Published by Alaxendra Bets at August 27th, 2021 , Revised On August 23, 2023

Images are inserted in a text and then referenced at the end of the manuscript. However, the in-text citations for an image are different from that of non-visual material. The in-text citation for an image is given below the image, where, instead of the author’s name, the image creator’s or photographer’s name is given, along with the image title and the year it was photographed.

In-Text and Reference List Format with Examples

Harvard referencing style uses the following basic format for citing and referencing an image file:

In-text citation: (Name of photographer or creator, Year of Publication)

Reference list entry: Author Surname, Author Initial. (Year Published). Title in italics. [Format, e.g., image] Available at: http://Website URL [Accessed Date Accessed].

For example:

In-text citation: Construct validity is usually thought of as the degree to which assessments measure what they are designed to measure, but since our assessments do much more than provide a score, we think of construct validity more broadly—as the degree to which our assessments accomplish what they are designed to accomplish. (Lectica, Inc, 2014)

Reference list entry: Lectica, Inc, (2014). Validity . [image] Available at: https://dts.lectica.org/_about/las_reliability_validity.php [Accessed 19 Oct. 2014].

However, some institutions also follow this basic format for the reference list entry:

Author(s) of the visual item – Surname and initials year of publication, Title of the visual item in italics, Extra information – photograph/painting etc., Publisher name, Place of publication.

Types of Citations Depending on Source of Image

Citations for image files in Harvard might slightly vary, depending on where the image was taken from.

1. Charts

Some academic texts include an image that is actually an image of a chart. Whereas some writers create their own charts or copy-paste charts from external sources, some might choose to take a screenshot of a chart from an external source and include that as an image file in their manuscript. In either case, acknowledging the chart’s original creators is compulsory.

Luckily, Harvard has made authors’ tasks easier by keeping the citation and referencing format the same for charts and images. After all, charts are treated in the same way as an image file in Harvard texts. A chart, cited in Harvard, would be cited in the following way, for instance:

In-text citation: (Newton 2007) to be placed directly below the chart or its image.

Reference list entry: Newton, AC 2007, Forest Ecology and Conservation: A Handbook of Techniques , Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

2. Personal images

If an image has been created by the writer themselves, it’s important that this is mentioned in the text. Otherwise, there will be confusion about whether an external source was referred to for the image.

In Harvard style, a personal image would be cited in the same way as an image created by someone else (as mentioned above), for example:

In-text citation: (Whyle 2008)

Reference list entry: Whyle, M 2008, Untitled [photographs of classroom displays], unpublished photographs.

Where the phrase ‘photographs of classroom displays’ refers to the format of the image, indicating it’s an image(s) of classroom displays.

1. Clipart images from online software libraries

Cliparts are also a form of image, except that they’re not naturally captured, like one would capture the image of a tree outside, for instance. Rather, cliparts are created using software in computer systems.

Even the everyday use software app in Windows, Paint, can be used to create clipart. Microsoft Word also has texts that are in the form of clipart. They’re textual pieces that are in the form of images.

Such an image is also treated as a normal image. As such, it’s cited in pretty much the same way too. However, in place of an author name, the name of the software and/or the corporation that created and/or uses that software is written instead, for example:

In-text citation: (Microsoft Clip Art Gallery 2010)

Reference list entry : Microsoft Clip Art Gallery 2010, Untitled [gymnast graphic], Microsoft Corporation.

Here, this image is untitled. The word ‘untitled’ is written without italicisation. However, if the title were present, it would have been included and in italics.

2. Images without creator’s/photographer’s name

Often times an image might be missing its creator’s or photographer’s name. Harvard referencing dictates that authors cite such an image in the same way as that mentioned above. However, the title of the image is treated as the name of the creator or photographer, for example:

( Confrontation during Hong Kong protests 2019) where ‘Confrontation during Hong Kong protests’ is the name of the image, and as the example shows, it’s being used as the creator’s/photographer’s name.

3. Images without creation or publication dates

As with every other type of material that is missing a date, Harvard also uses the ‘n.d’ abbreviation to indicate ‘no date’ for an image. Furthermore, for images without titles, a brief description of the image is included instead (for example, the phrase ‘photographs of classroom displays’ in the example above) in place of the title. This is followed by the date the image was accessed on or n.d. if not applicable. For example:

(Google, n.d.)

In-text citation: (LookPictures n.d.)

Reference list entry: LookPictures n.d., Love Picture Ducks , photograph,

http://www.lookpictures.net/gallery/Love-Pictures/1391/Love-Picture-Ducks/

[Accessed 16 April 2012].

Important point to note: Some institutions recommend not enclosing the format of the image file in [] in Harvard style, such as the t’rm ‘photog’aph’ in the above example shows. However, if this method or any other method for citation is to be followed, it should be kept consistent throughout the manuscript, not to mention in accordance with what the institution has officially recommended.

Citing images viewed in person

Citing images that are viewed physically by oneself, instead of on the internet, are considered to be viewed ‘in person.’ Once they are seen in person, the writer might decide to find them online and then include them in his or her manuscript. One might view an image in person when one sees an image in a/an:

- Art gallery

- Art exhibition

…and so on.

In Harvard referencing, such images are cited and referenced in the same way as an image originally obtained from an online source. Following are some examples of such ‘in-person sources of images.

The general format is again the same, that is:

Name of institution/art gallery/location insteadcreator’sor’s name in italics image was viewed in followed by when, not separated by any comma.

4. Image from a book

Name in italics followed by the year and page number if available. For examplGertsakis’sis’s work, Their eyes will tell you, everything and nothing , 2017, in Millner and Moore (2018, p. 138) …

5. Image from Flickr

Image title followed by date accessed. For example:

This photo showing a panorama of Austrian mountains (Crazzolara 2018) is of high quality.

6. Original artwork

Image title in italics followed by date accessed. For example:

JSutherland’snd’s masterly depiction of early morning light at an artist’s camp in Box Hill was particularly admired in her painting The Mushroom Gatherers (1895).

7. When works have been viewed in-situ

In-situ refers to the original situation in which an image was seen in person for the first time. The general format for citing such images is:

Is DamHirst’sst’s painting Veillove’sve’s secrets (2017) reminiscent of Aboriginal artist Emily KKngwarreye’sye’s workHere’sre’s an example of a Harvard style citation of an original work viewed in a temporary exhibition:

In Wishing Well , Ektoras (2014) demonstrates..

Hire an Expert Writer

Orders completed by our expert writers are

- Formally drafted in an academic style

- Free Amendments and 100% Plagiarism Free – or your money back!

- 100% Confidential and Timely Delivery!

- Free anti-plagiarism report

- Appreciated by thousands of clients. Check client reviews

Frequently Asked Questions

How do you cite art in text harvard.

When citing art in Harvard style:

- Use artist’s last name and year of creation in parentheses.

- Example: (Smith, 2022) for in-text citation.

- In bibliography, include artist, year, title, medium, and location.

- Format: Artist. (Year). Title. Medium. Location: Gallery/Museum.

You May Also Like

Sometimes citing the Movie, Television and Radio Programs in Harvard Style is very tricky. Here is the easiest guide to do so

This guide discusses how to cite a website in Harvard style. When citing information from the Internet, it is of utmost importance to cite a source carefully, since information on the Internet can vary widely. Your reference should be accurate to lead the reader directly to the accurate source.

You must cite any tables, maps, or figures that you use in your work in the text. Such citation is usually given at the end of the source

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

Referencing - BU Harvard 23-24 Full Guide: Images or Photographs

- Print Versions of Guide

- What information you need: author/date/page numbers

- Placing Citations

- Quotations/Paraphrasing/Summarising

- No author or identifiable person/organisation

- Author published more than one source in same year

- Inserting Pictures and Tables (Figures)

- More than one source cited

- Abbreviating organisation names

- Source cited or quoted in another source (citing second hand)

- Chapter author of an edited book

- Legislation - UK Statutes (Acts of Parliament)

- Personal communications e.g interviews, photographs

- Unpublished sources e.g lectures

- Scriptural citations(e.g. Bible or Koran/Qur'an)

- Finding information to create a reference list

- Reference list or Bibliography?

- Journal Article

- Guidelines or Codes of Practice (including public and private documents)

- Newspaper Article

- Magazine Article

- Conference (e.g. paper, presentation, poster)

- Reference books, Encyclopedias and Formularies

- Legislation and Cases

- Translated Materials (non-English sources)

- Standards and Patents

- Images or Photographs

- Computer Program

- Social Media (e.g. Twitter, Facebook, blogs, apps)

- Moving Images and Sound (e.g. YouTube, podcast, TV, film, song, radio)

- Data / Data Sets This link opens in a new window

- Tools & Apps

- Academic Offences This link opens in a new window

- Generative Artificial Intelligence (GAI) This link opens in a new window

- Tutorials & Quizzes

- Example Essay

- Online Learning & Videos

Images or Photos

Important Notes:

- When inserting images or photographs into your university work, add it as a figure and just follow our instructions how to layout and reference figures .

- If you have permission from BU academics who are setting and marking your assignments to use your own personal photographs, reference those using the instructions for personal communications .

- When using photos or images in your University work that you find online, we recommend using those that are copyright free / creative commons licensed . You will find a list of free to use image websites in our Copyright for Researchers guide .

Instructions how to reference an image or photograph

Click on the headings below for instructions

Online image or photo

Referencing an online image or photograph: details, order and format

Instructions for referencing an online image or photograph

Inserting and citing figures (e.g. table, diagram, chart, graph, map, picture, image, illustration, photograph , screenshot etc.) in the main text of your work:

The example above is a photograph, so you could copy and insert the photograph into your work adding this citation underneath it:

[PHOTOGRAPH OF MEMORIAL WOULD BE INSERTED HERE FOR EXAMPLE]

Figure 1: Brownsea Island Charles van Raalte memorial (Downer 2009)

Referring to figures in the main text of your work (following instructions from the 'Citing in the Text' tab of this guide, point 6)

Use the figure number, so in the example used above you would approach it like this for example:

- e.g. Figure 1 shows a photograph of Brownsea Island …

If you had taken the photograph yourself, you would indicate that in the citation:

- e.g. Figure 2: Brownsea Island (personal collection).

Referencing a figure at the end of your work

< Online image or photograph

Organisation/Photographer/Artist’s Surname/Family Name, INITIALS., Year. Title of image [type of image]. Place of publication: Publisher (of online image, if available). Available from: URL [Accessed Date].

- e.g. Downer, C., 2009. Brownsea Island Charles van Raalte memorial - geograph.org.uk - 1445875.jpg [photograph]. Dorset: geography.org.uk. Available from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Brownsea_Island,_Charles_van_Raalte_memorial_-_geograph.org.uk_-_1445875.jpg [Accessed 28 August 2016].

Print image or photo

Referencing a print image or photograph: details, order and format

Instructions for referencing a print image or photograph

Organisation/Photographer/Artist’s Surname/Family Name, INITIALS., Year. Title of image [type of image]. Place of publication: Publisher if available. Collection Details if available (Collection, Document number, Geographical Town/Place: Name of Library/Archive/Repository).

- e.g. McNally, K., 1974. Primary 7 children from Bangor Central Primary School display their ‘Let’s look at Ulster’ project on the early settlement of Beannchor [photograph]. Antrim: Ulster Television. ITA/IBA/Cable Authority archive, 5023/9, Bournemouth: Bournemouth University.

- << Previous: Standards and Patents

- Next: Computer Program >>

- Last Updated: Mar 12, 2024 4:04 PM

- URL: https://libguides.bournemouth.ac.uk/bu-referencing-harvard-style

Harvard Referencing Guide: Images - Figure from a book

- Introduction to the Guide

- The Harvard Referencing Method

- Cite Them Right Style

- Referencing Example

- Cite-Them-Right Text Book

- Online Tutorials

- Reference List / Bibliography

Introduction

- Short Quotations

- Long Quotations

- Single Author

- Two Authors

- Three Authors

- Four or More Authors

- 2nd Edition

- Chapter in an Edited Book

- Journal Article - Online

- Journal Article - Printed

- Newspaper Article - Online

- Newspaper Article - Printed

- Webpage - Introduction

- Webpage - Individual Authors

- Webpage - Corporate Authors

- Webpage - No Author - No Date

- Film / Movie

- TV Programme

- PowerPoint Presentations

- YouTube Video

- Images - Introduction

- Images - Figure from a book

- Images - Online Figure

- Images - Online Table

- Twitter Tweet

- Personal Communication

- Email message in a Public Domain

- Course notes on the VLE

- Computer Games

- Computer Program

- General Referencing Guide >>>

- APA Referencing Guide >>>

- IEEE Referencing Guide >>>

- Research Guide >>>

Images from Books

Images - From Books

Figure from a book

Images fall into two broad categories. These are ;

Figures . These include photographs, illustrations, drawings, diagrams, logos, graphs and maps etc.

Tables . These are simply word/numbers that are displayed in orderly rows as columns such as a sprea dshe et.

- Include a caption with a number and in-text citation - below the image for a figure but above the image for a table.

- Make a reference to the image at the relevant point in your text.

- Include a full reference in your Reference List/Bibliography

A reference to an image from a book will generally require the following elements:

- Author of the book

- Year of publication (in round brackets)

- Title of the book (in italics)

- Place of publication: Publisher

In-text citation

Full reference for the Reference List / Bibliography

Online figure

Online table

Harvard Referencing Guide: A - Z

- APA Referencing Guide >>>

- Bibliography

- Books / eBooks - 2 Authors

- Books / eBooks - 2nd Edition

- Books / eBooks - 3 Authors

- Books / eBooks - Individual Chapter

- Books / eBooks - Introduction

- Books / eBooks - More than 3 Authors

- Books / eBooks - Single Author

- Chapter in an edited book

- Cite Them Right - Style

- Cite Them Right - Text book

- Conversation - Personal

- Direct Quotations - Introduction

- Direct Quotations - Long

- Direct Quotations - Short

- Emails - In a Public Domain

- Emails - Personal

- Fax message

- General Referencing Guide >>>

- Harvard Referencing Method

- PowerPoint Presentation

- Reference List

- Skype Conversation - Personal

- Support - 'Cite Them Right' textbook

- Support - Online tutorials

- Text Message

- Webpage - Corporate Author

- Webpage - Individual Author

- << Previous: Images - Introduction

- Next: Images - Online Figure >>

- Last Updated: Mar 13, 2024 11:31 AM

- URL: https://libguides.wigan-leigh.ac.uk/HarvardReferencing

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Citing sources

How to Cite an Image | Photographs, Figures, Diagrams

Published on March 25, 2021 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on June 28, 2022.

To cite an image, you need an in-text citation and a corresponding reference entry. The reference entry should list:

- The creator of the image

- The year it was published

- The title of the image

- The format of the image (e.g., “photograph”)

- Its location or container (e.g. a website , book , or museum)

The format varies depending on where you accessed the image and which citation style you’re using: APA , MLA , or Chicago .

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Citing an image in apa style, citing an image in mla style, citing an image in chicago style, frequently asked questions about citations.

In an APA Style reference entry for an image found on a website , write the image title in italics, followed by a description of its format in square brackets. Include the name of the site and the URL. The APA in-text citation just includes the photographer’s name and the year.

The information included after the title and format varies for images from other containers (e.g. books , articles ).

When you include the image itself in your text, you’ll also have to format it as a figure and include appropriate copyright/permissions information .

Images viewed in person

For an artwork viewed at a museum, gallery, or other physical archive, include information about the institution and location. If there’s a page on the institution’s website for the specific work, its URL can also be included.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

In an MLA Works Cited entry for an image found online , the title of the image appears in quotation marks, the name of the site in italics. Include the full publication date if available, not just the year.

The MLA in-text citation normally just consists of the author’s last name.

The information included after the title and format differs for images contained within other source types, such as books and articles .

If you include the image itself as a figure, make sure to format it correctly .

A citation for an image viewed in a museum (or other physical archive, e.g. a gallery) includes the name and location of the institution instead of website information.

In Chicago style , images may just be referred to in the text without need for a citation or bibliography entry.

If you have to include a full Chicago style image citation , however, list the title in italics, add relevant information about the image format, and add a URL at the end of the bibliography entry for images consulted online.

Chicago also offers an alternative author-date citation style . Examples of image citations in this style can be found here .

For an image viewed in a museum, gallery, or other physical archive, you can again just refer to it in the text without a formal citation. If a citation is required, list the institution and the city it is located in at the end of the bibliography entry.

The main elements included in image citations across APA , MLA , and Chicago style are the name of the image’s creator, the image title, the year (or more precise date) of publication, and details of the container in which the image was found (e.g. a museum, book , website ).

In APA and Chicago style, it’s standard to also include a description of the image’s format (e.g. “Photograph” or “Oil on canvas”). This sort of information may be included in MLA too, but is not mandatory.

Untitled sources (e.g. some images ) are usually cited using a short descriptive text in place of the title. In APA Style , this description appears in brackets: [Chair of stained oak]. In MLA and Chicago styles, no brackets are used: Chair of stained oak.

For social media posts, which are usually untitled, quote the initial words of the post in place of the title: the first 160 characters in Chicago , or the first 20 words in APA . E.g. Biden, J. [@JoeBiden]. “The American Rescue Plan means a $7,000 check for a single mom of four. It means more support to safely.”

MLA recommends quoting the full post for something short like a tweet, and just describing the post if it’s longer.

In APA , MLA , and Chicago style citations for sources that don’t list a specific author (e.g. many websites ), you can usually list the organization responsible for the source as the author.

If the organization is the same as the website or publisher, you shouldn’t repeat it twice in your reference:

- In APA and Chicago, omit the website or publisher name later in the reference.

- In MLA, omit the author element at the start of the reference, and cite the source title instead.

If there’s no appropriate organization to list as author, you will usually have to begin the citation and reference entry with the title of the source instead.

Check if your university or course guidelines specify which citation style to use. If the choice is left up to you, consider which style is most commonly used in your field.

- APA Style is the most popular citation style, widely used in the social and behavioral sciences.

- MLA style is the second most popular, used mainly in the humanities.

- Chicago notes and bibliography style is also popular in the humanities, especially history.

- Chicago author-date style tends to be used in the sciences.

Other more specialized styles exist for certain fields, such as Bluebook and OSCOLA for law.

The most important thing is to choose one style and use it consistently throughout your text.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2022, June 28). How to Cite an Image | Photographs, Figures, Diagrams. Scribbr. Retrieved March 12, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/citing-sources/cite-an-image/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to cite a youtube video | mla, apa & chicago, how to cite a website | mla, apa & chicago examples, how to cite a book | apa, mla, & chicago examples, scribbr apa citation checker.

An innovative new tool that checks your APA citations with AI software. Say goodbye to inaccurate citations!

Finding Images

- Finding Still Images

- Finding Moving Images

Referencing your images

- Reverse image searching

- Academic Skills Gateway

- Book an ASC Appointment

Like any book or journal article, images created by someone else must be cited with a 'sufficient acknowledgment'. This means every time you use an image in an essay you must provide a citation where the image appears and then an entry in your reference list or bibliography. You must also provide a citation to any images you use in presentations, blogs or websites.

It is vital that you keep an accurate record of everything you consult when doing your work and cite what you have used clearly so that:

- You can find the original source again yourself

- Someone reading your work will be able to find the original source

- You can avoid plagiarism by making clear what is your work and what is in the source

You can maintain a record of the references you using either a bibliographic software package such as EndNote or by recording the details manually on reference cards.

For more information on quoting and managing references see the i-cite website

Sufficient Acknowledgment

To comply with copyright law, even within educational exceptions, you must always include a sufficient acknowledgment when using still and moving images. Think of this like referencing a text - if you did not include the reference you would be plagiarising another person's work.

A sufficient acknowledgement should include the following:

- Artist/ maker/ author

- Title of the work and date made

- Source of the reproduction/film

For example: Julia Margaret Cameron, The Mountain Nymph Sweet Liberty, 1866, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Image databases, like Bridgeman and Artstor, often include an acknowledgement for you to use which can be directly copied and pasted into your work.

When using an image from Flickr or Creative Commons, the name of the person who has uploaded the image can also be used. This is usually included in the details section of the image.

- << Previous: Copyright

- Next: Reverse image searching >>

- Last Updated: Sep 14, 2023 1:26 PM

- URL: https://libguides.bham.ac.uk/subjectsupport/skills/images

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Referencing

A Quick Guide to Harvard Referencing | Citation Examples

Published on 14 February 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on 15 September 2023.

Referencing is an important part of academic writing. It tells your readers what sources you’ve used and how to find them.

Harvard is the most common referencing style used in UK universities. In Harvard style, the author and year are cited in-text, and full details of the source are given in a reference list .

Harvard Reference Generator

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Harvard in-text citation, creating a harvard reference list, harvard referencing examples, referencing sources with no author or date, frequently asked questions about harvard referencing.

A Harvard in-text citation appears in brackets beside any quotation or paraphrase of a source. It gives the last name of the author(s) and the year of publication, as well as a page number or range locating the passage referenced, if applicable:

Note that ‘p.’ is used for a single page, ‘pp.’ for multiple pages (e.g. ‘pp. 1–5’).

An in-text citation usually appears immediately after the quotation or paraphrase in question. It may also appear at the end of the relevant sentence, as long as it’s clear what it refers to.

When your sentence already mentions the name of the author, it should not be repeated in the citation:

Sources with multiple authors

When you cite a source with up to three authors, cite all authors’ names. For four or more authors, list only the first name, followed by ‘ et al. ’:

Sources with no page numbers

Some sources, such as websites , often don’t have page numbers. If the source is a short text, you can simply leave out the page number. With longer sources, you can use an alternate locator such as a subheading or paragraph number if you need to specify where to find the quote:

Multiple citations at the same point

When you need multiple citations to appear at the same point in your text – for example, when you refer to several sources with one phrase – you can present them in the same set of brackets, separated by semicolons. List them in order of publication date:

Multiple sources with the same author and date

If you cite multiple sources by the same author which were published in the same year, it’s important to distinguish between them in your citations. To do this, insert an ‘a’ after the year in the first one you reference, a ‘b’ in the second, and so on:

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

A bibliography or reference list appears at the end of your text. It lists all your sources in alphabetical order by the author’s last name, giving complete information so that the reader can look them up if necessary.

The reference entry starts with the author’s last name followed by initial(s). Only the first word of the title is capitalised (as well as any proper nouns).

Sources with multiple authors in the reference list

As with in-text citations, up to three authors should be listed; when there are four or more, list only the first author followed by ‘ et al. ’:

Reference list entries vary according to source type, since different information is relevant for different sources. Formats and examples for the most commonly used source types are given below.

- Entire book

- Book chapter

- Translated book

- Edition of a book

Journal articles

- Print journal

- Online-only journal with DOI

- Online-only journal with no DOI

- General web page

- Online article or blog

- Social media post

Sometimes you won’t have all the information you need for a reference. This section covers what to do when a source lacks a publication date or named author.

No publication date

When a source doesn’t have a clear publication date – for example, a constantly updated reference source like Wikipedia or an obscure historical document which can’t be accurately dated – you can replace it with the words ‘no date’:

Note that when you do this with an online source, you should still include an access date, as in the example.

When a source lacks a clearly identified author, there’s often an appropriate corporate source – the organisation responsible for the source – whom you can credit as author instead, as in the Google and Wikipedia examples above.

When that’s not the case, you can just replace it with the title of the source in both the in-text citation and the reference list:

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

Harvard referencing uses an author–date system. Sources are cited by the author’s last name and the publication year in brackets. Each Harvard in-text citation corresponds to an entry in the alphabetised reference list at the end of the paper.

Vancouver referencing uses a numerical system. Sources are cited by a number in parentheses or superscript. Each number corresponds to a full reference at the end of the paper.

A Harvard in-text citation should appear in brackets every time you quote, paraphrase, or refer to information from a source.

The citation can appear immediately after the quotation or paraphrase, or at the end of the sentence. If you’re quoting, place the citation outside of the quotation marks but before any other punctuation like a comma or full stop.

In Harvard referencing, up to three author names are included in an in-text citation or reference list entry. When there are four or more authors, include only the first, followed by ‘ et al. ’

Though the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, there is a difference in meaning:

- A reference list only includes sources cited in the text – every entry corresponds to an in-text citation .

- A bibliography also includes other sources which were consulted during the research but not cited.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, September 15). A Quick Guide to Harvard Referencing | Citation Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 12 March 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/referencing/harvard-style/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, harvard in-text citation | a complete guide & examples, harvard style bibliography | format & examples, referencing books in harvard style | templates & examples, scribbr apa citation checker.

An innovative new tool that checks your APA citations with AI software. Say goodbye to inaccurate citations!

- TutorHome |

- IntranetHome |

- Contact the OU Contact the OU Contact the OU |

- Accessibility Accessibility

- StudentHome

- Help Centre

You are here

Help and support.

- Referencing and plagiarism

Quick guide to Harvard referencing (Cite Them Right)

- Site Accessibility: Library Services

Print this page

There are different versions of the Harvard referencing style. This guide is a quick introduction to the commonly-used Cite Them Right version. You will find further guidance available through the OU Library on the Cite Them Right Database .

For help and support with referencing and the full Cite Them Right guide, have a look at the Library’s page on referencing and plagiarism . If you need guidance referencing OU module material you can check out which sections of Cite Them Right are recommended when referencing physical and online module material .

This guide does not apply to OU Law undergraduate students . If you are studying a module beginning with W1xx, W2xx or W3xx, you should refer to the Quick guide to Cite Them Right referencing for Law modules .

Table of contents

In-text citations and full references.

- Secondary referencing

- Page numbers

- Citing multiple sources published in the same year by the same author

Full reference examples

Referencing consists of two elements:

- in-text citations, which are inserted in the body of your text and are included in the word count. An in-text citation gives the author(s) and publication date of a source you are referring to. If the publication date is not given, the phrase 'no date' is used instead of a date. If using direct quotations or you refer to a specific section in the source you also need the page number/s if available, or paragraph number for web pages.

- full references, which are given in alphabetical order in reference list at the end of your work and are not included in the word count. Full references give full bibliographical information for all the sources you have referred to in the body of your text.

To see a reference list and intext citations check out this example assignment on Cite Them Right .

Difference between reference list and bibliography

a reference list only includes sources you have referred to in the body of your text

a bibliography includes sources you have referred to in the body of your text AND sources that were part of your background reading that you did not use in your assignment

Back to top

Examples of in-text citations

You need to include an in-text citation wherever you quote or paraphrase from a source. An in-text citation consists of the last name of the author(s), the year of publication, and a page number if relevant. There are a number of ways of incorporating in-text citations into your work - some examples are provided below. Alternatively you can see examples of setting out in-text citations in Cite Them Right .

Note: When referencing a chapter of an edited book, your in-text citation should give the author(s) of the chapter.

Online module materials

(Includes written online module activities, audio-visual material such as online tutorials, recordings or videos).

When referencing material from module websites, the date of publication is the year you started studying the module.

Surname, Initial. (Year of publication/presentation) 'Title of item'. Module code: Module title . Available at: URL of VLE (Accessed: date).

OR, if there is no named author:

The Open University (Year of publication/presentation) 'Title of item'. Module code: Module title . Available at: URL of VLE (Accessed: date).

Rietdorf, K. and Bootman, M. (2022) 'Topic 3: Rare diseases'. S290: Investigating human health and disease . Available at: https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=1967195 (Accessed: 24 January 2023).

The Open University (2022) ‘3.1 The purposes of childhood and youth research’. EK313: Issues in research with children and young people . Available at: https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=1949633§ion=1.3 (Accessed: 24 January 2023).

You can also use this template to reference videos and audio that are hosted on your module website:

The Open University (2022) ‘Video 2.7 An example of a Frith-Happé animation’. SK298: Brain, mind and mental health . Available at: https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2013014§ion=4.9.6 (Accessed: 22 November 2022).

The Open University (2022) ‘Audio 2 Interview with Richard Sorabji (Part 2)’. A113: Revolutions . Available at: https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=1960941§ion=5.6 (Accessed: 22 November 2022).

Note: if a complete journal article has been uploaded to a module website, or if you have seen an article referred to on the website and then accessed the original version, reference the original journal article, and do not mention the module materials. If only an extract from an article is included in your module materials that you want to reference, you should use secondary referencing, with the module materials as the 'cited in' source, as described above.

Surname, Initial. (Year of publication) 'Title of message', Title of discussion board , in Module code: Module title . Available at: URL of VLE (Accessed: date).

Fitzpatrick, M. (2022) ‘A215 - presentation of TMAs', Tutor group discussion & Workbook activities , in A215: Creative writing . Available at: https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/forumng/discuss.php?d=4209566 (Accessed: 24 January 2022).

Note: When an ebook looks like a printed book, with publication details and pagination, reference as a printed book.

Surname, Initial. (Year of publication) Title . Edition if later than first. Place of publication: publisher. Series and volume number if relevant.

For ebooks that do not contain print publication details

Surname, Initial. (Year of publication) Title of book . Available at: DOI or URL (Accessed: date).

Example with one author:

Bell, J. (2014) Doing your research project . Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Adams, D. (1979) The hitchhiker's guide to the galaxy . Available at: http://www.amazon.co.uk/kindle-ebooks (Accessed: 23 June 2021).

Example with two or three authors:

Goddard, J. and Barrett, S. (2015) The health needs of young people leaving care . Norwich: University of East Anglia, School of Social Work and Psychosocial Studies.

Example with four or more authors:

Young, H.D. et al. (2015) Sears and Zemansky's university physics . San Francisco, CA: Addison-Wesley.

Note: You can choose one or other method to reference four or more authors (unless your School requires you to name all authors in your reference list) and your approach should be consistent.

Note: Books that have an editor, or editors, where each chapter is written by a different author or authors.

Surname of chapter author, Initial. (Year of publication) 'Title of chapter or section', in Initial. Surname of book editor (ed.) Title of book . Place of publication: publisher, Page reference.

Franklin, A.W. (2012) 'Management of the problem', in S.M. Smith (ed.) The maltreatment of children . Lancaster: MTP, pp. 83–95.

Surname, Initial. (Year of publication) 'Title of article', Title of Journal , volume number (issue number), page reference.

If accessed online:

Surname, Initial. (Year of publication) 'Title of article', Title of Journal , volume number (issue number), page reference. Available at: DOI or URL (if required) (Accessed: date).

Shirazi, T. (2010) 'Successful teaching placements in secondary schools: achieving QTS practical handbooks', European Journal of Teacher Education , 33(3), pp. 323–326.

Shirazi, T. (2010) 'Successful teaching placements in secondary schools: achieving QTS practical handbooks', European Journal of Teacher Education , 33(3), pp. 323–326. Available at: https://libezproxy.open.ac.uk/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/log... (Accessed: 27 January 2023).

Barke, M. and Mowl, G. (2016) 'Málaga – a failed resort of the early twentieth century?', Journal of Tourism History , 2(3), pp. 187–212. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/1755182X.2010.523145

Surname, Initial. (Year of publication) 'Title of article', Title of Newspaper , Day and month, Page reference.

Surname, Initial. (Year of publication) 'Title of article', Title of Newspaper , Day and month, Page reference if available. Available at: URL (Accessed: date).

Mansell, W. and Bloom, A. (2012) ‘£10,000 carrot to tempt physics experts’, The Guardian , 20 June, p. 5.

Roberts, D. and Ackerman, S. (2013) 'US draft resolution allows Obama 90 days for military action against Syria', The Guardian , 4 September. Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/sep/04/syria-strikes-draft-resolut... (Accessed: 9 September 2015).

Surname, Initial. (Year that the site was published/last updated) Title of web page . Available at: URL (Accessed: date).

Organisation (Year that the page was last updated) Title of web page . Available at: URL (Accessed: date).

Robinson, J. (2007) Social variation across the UK . Available at: https://www.bl.uk/british-accents-and-dialects/articles/social-variation... (Accessed: 21 November 2021).

The British Psychological Society (2018) Code of Ethics and Conduct . Available at: https://www.bps.org.uk/news-and-policy/bps-code-ethics-and-conduct (Accessed: 22 March 2019).

Note: Cite Them Right Online offers guidance for referencing webpages that do not include authors' names and dates. However, be extra vigilant about the suitability of such webpages.

Surname, Initial. (Year) Title of photograph . Available at: URL (Accessed: date).

Kitton, J. (2013) Golden sunset . Available at: https://www.jameskittophotography.co.uk/photo_8692150.html (Accessed: 21 November 2021).

stanitsa_dance (2021) Cossack dance ensemble . Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/COI_slphWJ_/ (Accessed: 13 June 2023).

Note: If no title can be found then replace it with a short description.

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Getting started with the online library

- Disabled user support

- Finding resources for your assignment

- Finding ejournals and articles

- Access eresources using Google Scholar

- Help with online resources

- Finding and using books and theses

- Finding information on your research topic

- Canllaw Cyflym i Gyfeirnodi Harvard (Cite Them Right)

- Quick guide to Cite Them Right referencing for Law modules

- The Classical Studies guide to referencing

- Bibliographic management

- What if I cannot find the reference type I need in my referencing guide?

- I have found a web page with no author, date or publisher - how do I reference it?

- Training and skills

- Study materials

- Using other libraries and SCONUL Access

- Borrowing at the Walton Hall Library

- OU Glossary

- Contacting the helpdesk

Smarter searching with library databases

Monday, 18 March, 2024 - 07:00

Learn how to access library databases, take advantage of the functionality they offer, and devise a proper search technique.

Library Helpdesk

Chat to a Librarian - Available 24/7

Other ways to contact the Library Helpdesk

The Open University

- Study with us

- Supported distance learning

- Funding your studies

- International students

- Global reputation

- Apprenticeships

- Develop your workforce

- News & media

- Contact the OU

Undergraduate

- Arts and Humanities

- Art History

- Business and Management

- Combined Studies

- Computing and IT

- Counselling

- Creative Writing

- Criminology

- Early Years

- Electronic Engineering

- Engineering

- Environment

- Film and Media

- Health and Social Care

- Health and Wellbeing

- Health Sciences

- International Studies

- Mathematics

- Mental Health

- Nursing and Healthcare

- Religious Studies

- Social Sciences

- Social Work

- Software Engineering

- Sport and Fitness

Postgraduate

- Postgraduate study

- Research degrees

- Masters in Art History (MA)

- Masters in Computing (MSc)

- Masters in Creative Writing (MA)

- Masters degree in Education

- Masters in Engineering (MSc)

- Masters in English Literature (MA)

- Masters in History (MA)

- Master of Laws (LLM)

- Masters in Mathematics (MSc)

- Masters in Psychology (MSc)

- A to Z of Masters degrees

- Accessibility statement

- Conditions of use

- Privacy policy

- Cookie policy

- Manage cookie preferences

- Modern slavery act (pdf 149kb)

Follow us on Social media

- Student Policies and Regulations

- Student Charter

- System Status

- Contact the OU Contact the OU

- Modern Slavery Act (pdf 149kb)

© . . .

- Anglia Ruskin University Library

- Library Support

Q. How do I reference my own taken photographs?

- General FAQ

- Plagiarism and Good Academic Practice

- Search & Access

- 3 Accessibility

- 5 Accounts and Logins

- 23 Borrowing

- 9 Databases

- 4 Dissertations and Theses

- 8 Electronic Resources

- 2 Exam Papers

- 11 Finding resources

- 12 Library Facilities

- 9 Library Membership

- 3 Plagiarism and Good Academic Practice

- 38 Referencing and Citing

- 12 Requests

- 5 SCONUL Access

- 2 Study Rooms/Pods

- 11 Training

- 16 University Information

- 49 Using the library

Answered By: Elaine Pocklington Last Updated: Jan 11, 2024 Views: 130630

Cite Them Right Harvard referencing style: Look under the tab "Media and Art" and find "Photographic Prints or Slides" suggested elements for a reference are: Artist/Photographer's name (if known), Year of production. Title of image . [type of medium] and Place of Publication

For Example: Beaton,C. (1956) Marilyn Monroe [Photograph]. (Marilyn Monroe's own private collection).

Referencing your own photographs, it should be as above with your name and year taken. Give it a title and reference it as a photograph from your own private collection.

Links & Files

- Referencing

- Study Skills Plus (Study Support)

- Cite Them Right

- Share on Facebook

Was this helpful? Yes 70 No 289

Comments (0)

Library help, related topics.

- Referencing and Citing

Harvard Referencing

- Summarising/Paraphrasing

- Citations/Direct Quotations

- Books (print or online)

- Electronic Journal Article

- Website/Web Document

- Journal/Magazine Article

- Academic publications

- Audiovisual material

- News Article (print or online)

- Figures/Tables

- Public documents

- Performance

- Reference List Example

- More Information

Figures & Graphs

Figures include diagrams and all types of graphs. An i m a ge, photo, illustration or screenshot displayed for scientific purposes is classed as a figure.

All figures in your paper must be referred to in the main body of the text. At the bottom of the figure is the title, explaining what the figure is showing and the legend, i.e. an explanation of what the symbols, acronyms or colours mean.

In-text citation:

The in-text reference is placed beneath the legend and title with the heading 'Figure' and starts with a sequential figure number (e.g. Figure 1, Figure 2).

Figure 1: PHYSICAL PRODUCTION, selected commodities, Australia, 2010-11 to 2015-16 ( Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics 2017)

If the source is from a book or journal (print or electronic) or from a web document with page numbers, add the page number to the in-text citation.

If the figure is altered in any way from the original source, add 'Modified from source', eg.

(Modified from source: Australian Bureau of Statistics 2017)

In main text:

Production of sugar in Australia was estimated at 34 million tonnes in 2015-16 (Figure 1).

Reference list:

References should be listed in the Harvard Referencing Style according to format.

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2017, Crops and plantations , Retrieved: 24 February, 2018 from http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Latestproducts/4632.0.55.001Main%20Features302015-16?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=4632.0.55.001&issue=2015-16&num=&view=

Tables are numerical values or text displayed in rows and columns.

Each table should be displayed with a brief explanatory title at the top.

Number all tables in the order they appear in the text.

Table 27.4 Immunity to selected bacterial infections

( Source: Knox et al. 2014, p. 669. )

If the table is altered in any way from the original source, add 'Modified from source'.

(Modified from source: Knox et al. 2014, p. 669. )

Some bacteria, like those that cause tuberculosis, have evolved the means of surviving and living within phagocytic macrophages (Table 27.4).

As Table 27.4 shows, some bacteria , like those that cause tuberculosis, have evolved the means of surviving an d living within phagocytic macrophages.

Knox, B., Ladiges, P., Evans, B. & Saint, R. 2014, Biology: an Australian focus , 5th edn, McGraw-Hill Education, North Ryde, NSW.

- << Previous: Image

- Next: Lectures >>

- Last Updated: Feb 16, 2024 12:56 PM

- URL: https://libguides.bhtafe.edu.au/harvard

Harvard Reference Generator

Referencing a photograph.

Please fill out ALL the details below, then click the button to generate your reference in the correct format.

About The Harvard Referencing Tool

If you're a student and have ever had to write reports, essays or a thesis, you will have had to reference the sources of information you have used. If you mention something that someone else has written/published, you need to give them credit by referencing their work.

The Harvard Referencing System is one of the preferred layouts for these references. It is a relatively strict way of arranging the bibliographical information.

This Harvard Reference Generator tool takes in the raw information - things like author, title, year of publication - and creates the reference in the correct form.

You can then highlight and copy this into the bibliography section of your report - arranging them alphabetically by authors' surnames .

You then reference this next to the relevant section within the main text of your essay in the format (Author, Year) such as (Smith, 1983) .

If you are citing more than one work from the same author in the same year , you add a letter to the year to differentiate them (not the first one, though)

Harvard Reference Photograph Format

The correct format for a Harvard Photo Citation is:

What's the point of a bibliography in a report or essay?

Cite A Online image or video in Harvard style

Powered by chegg.

- Select style:

- Archive material

- Chapter of an edited book

- Conference proceedings

- Dictionary entry

- Dissertation

- DVD, video, or film

- E-book or PDF

- Edited book

- Encyclopedia article

- Government publication

- Music or recording

- Online image or video

- Presentation

- Press release

- Religious text

Use the following template or our Harvard Referencing Generator to cite a online image or video. For help with other source types, like books, PDFs, or websites, check out our other guides. To have your reference list or bibliography automatically made for you, try our free citation generator .

Reference list

Place this part in your bibliography or reference list at the end of your assignment.

In-text citation

Place this part right after the quote or reference to the source in your assignment.

Popular Harvard Citation Guides

- How to cite a Book in Harvard style

- How to cite a Website in Harvard style

- How to cite a Journal in Harvard style

- How to cite a DVD, video, or film in Harvard style

- How to cite a Online image or video in Harvard style

Other Harvard Citation Guides

- How to cite a Archive material in Harvard style

- How to cite a Artwork in Harvard style

- How to cite a Blog in Harvard style

- How to cite a Broadcast in Harvard style

- How to cite a Chapter of an edited book in Harvard style

- How to cite a Conference proceedings in Harvard style

- How to cite a Court case in Harvard style

- How to cite a Dictionary entry in Harvard style

- How to cite a Dissertation in Harvard style

- How to cite a E-book or PDF in Harvard style

- How to cite a Edited book in Harvard style

- How to cite a Email in Harvard style

- How to cite a Encyclopedia article in Harvard style

- How to cite a Government publication in Harvard style

- How to cite a Interview in Harvard style

- How to cite a Legislation in Harvard style

- How to cite a Magazine in Harvard style

- How to cite a Music or recording in Harvard style

- How to cite a Newspaper in Harvard style

- How to cite a Patent in Harvard style

- How to cite a Podcast in Harvard style

- How to cite a Presentation or lecture in Harvard style

- How to cite a Press release in Harvard style

- How to cite a Religious text in Harvard style

- How to cite a Report in Harvard style

- How to cite a Software in Harvard style

- Free Tools for Students

- Harvard Referencing Generator

Free Harvard Referencing Generator

Generate accurate Harvard reference lists quickly and for FREE, with MyBib!

🤔 What is a Harvard Referencing Generator?

A Harvard Referencing Generator is a tool that automatically generates formatted academic references in the Harvard style.

It takes in relevant details about a source -- usually critical information like author names, article titles, publish dates, and URLs -- and adds the correct punctuation and formatting required by the Harvard referencing style.

The generated references can be copied into a reference list or bibliography, and then collectively appended to the end of an academic assignment. This is the standard way to give credit to sources used in the main body of an assignment.

👩🎓 Who uses a Harvard Referencing Generator?

Harvard is the main referencing style at colleges and universities in the United Kingdom and Australia. It is also very popular in other English-speaking countries such as South Africa, Hong Kong, and New Zealand. University-level students in these countries are most likely to use a Harvard generator to aid them with their undergraduate assignments (and often post-graduate too).

🙌 Why should I use a Harvard Referencing Generator?

A Harvard Referencing Generator solves two problems:

- It provides a way to organise and keep track of the sources referenced in the content of an academic paper.