- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 22 December 2022

Perpetuation of gender discrimination in Pakistani society: results from a scoping review and qualitative study conducted in three provinces of Pakistan

- Tazeen Saeed Ali ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8896-8766 1 , 2 ,

- Shahnaz Shahid Ali 1 ,

- Sanober Nadeem 3 ,

- Zahid Memon 4 ,

- Sajid Soofi 4 ,

- Falak Madhani 3 ,

- Yasmin Karim 5 ,

- Shah Mohammad 4 &

- Zulfiqar Ahmed Bhutta 6 , 7

BMC Women's Health volume 22 , Article number: 540 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

41k Accesses

4 Citations

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

Gender discrimination is any unequal treatment of a person based on their sex. Women and girls are most likely to experience the negative impact of gender discrimination. The aim of this study is to assess the factors that influence gender discrimination in Pakistan, and its impact on women’s life.

A mixed method approach was used in the study in which a systematic review was done in phase one to explore the themes on gender discrimination, and qualitative interviews were conducted in phase two to explore the perception of people regarding gender discrimination. The qualitative interviews (in-depth interviews and focus group discussions) were conducted from married men and women, adolescent boys and girls, Healthcare Professionals (HCPs), Lady Health Visitors (LHVs) and Community Midwives (CMWs). The qualitative interviews were analyzed both manually and electronically through QSR NVivo 10. The triangulation of data from the systematic review and qualitative interviews were done to explore the gender discrimination related issues in Pakistan.

The six major themes have emerged from the systematic review and qualitative interviews. It includes (1) Status of a woman in the society (2) Gender inequality in health (3) Gender inequality in education (4) Gender inequality in employment (5) Gender biased social norms and cultural practices and (6) Micro and macro level recommendations. In addition, a woman is often viewed as a sexual object and dependent being who lacks self identity unless being married. Furthermore, women are restricted to household and child rearing responsibilities and are often neglected and forced to suppress self-expression. Likewise, men are viewed as dominant figures in lives of women who usually makes all family decisions. They are considered as financial providers and source of protection. Moreover, women face gender discrimination in many aspects of life including education and access to health care.

Gender discrimination is deeply rooted in the Pakistani society. To prevent gender discrimination, the entire society, especially women should be educated and gendered sensitized to improve the status of women in Pakistan.

Peer Review reports

Gender discrimination refers to any situation where a person is treated differently because they are male or female, rather than based on their competency or proficiency [ 1 , 2 ]. Gender discrimination harms all of society and negatively impacts the economy, education, health and life expectancy [ 1 , 2 ]. Women and girls are most likely to experience the negative impacts of gender discrimination. It include inadequate educational opportunities, low status in society and lack of freedom to take decisions for self and family [ 1 , 3 ].

Likewise, gender discrimination is one of the human rights issues in Pakistan and is affecting huge proportion of women in the country [ 1 , 2 ]. In Pakistan, nearly 50% of the women lacks basic education [ 4 ]. In addition, women in Pakistan have lower health and nutritional status. Furthermore, most of the women are restricted in their homes with minimal or no rights to make choices, judgments, and decisions, that directly affect their living conditions and other familial aspects [ 2 ]. In contrast, men are considered dominant in the Pakistani society [ 5 ]. This subordination of women has negative influences on different stages of women’s life.

Study design

The mixed method study design was used. Systematic review was done in phase one and qualitative interviews; in-depth interviews (IDIs) and focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted in phase two.

The objective of the systematic review

To map a broad topic, gender discrimination/inequality research in Pakistan including women undergoing any form of intimate partner violence.

Systematic review

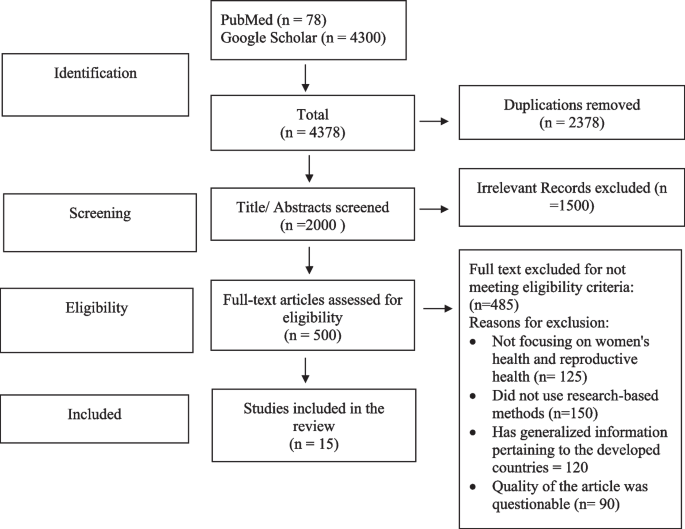

The three authors (TSA, SSA and SN) independently performed an extensive literature search using two databases: PubMed and Google Scholar and reports from organizations such as WHO and the Aurat Foundation. Quantitative and Boolean operators were used to narrow down the search results. The following keywords and phrases were used: Intimate partner violence (IPV), domestic violence, violence against women, domestic abuse, spousal violence, and Pakistan. Articles from 2008 to 2021 were assessed. The selection criteria of the articles included: women undergoing any form of IPV (physical, psychological, and sexual); quantitative study design; English as the publication language; and articles in which Pakistan was the study setting. The shortlisted articles were cross-checked by two of the authors (TSA, and SN) for final selection. The quality of the selected articles was reviewed using a STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) checklist, which ensured all articles followed a structured approach, including an introduction, methodology, results, and a discussion section. It was also determined that all selected articles are published in peer-reviewed journals and have been used nationally or internationally. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) chart was used for study selection (Fig. 1 ).

PRISMA Diagram to select the final articles

The selected articles were approved by one of the authors (TSA), who is an expert in the field of IPV. Articles were excluded: (i) If the study was not conducted in Pakistan; (ii) Studied spousal violence against men and (iii) Domestic violence involving in-laws or other family members. Furthermore, from the selected articles, the data were extracted by 3 authors (TSA, SSA, SN) by carefully studying the methodology and results. The methodology was entered into an extraction template in which location was summarized including the study design and sample size in the articles. The results covered: (i) The title, (ii) Authors, (iii) Publication year, (iv) Objectives of the research, (v) Population and Setting, (vi) Research design, (vii) Data collection methods, (ix) Results, (x) Perpetuating factors (xi) Recommendations and (xii) prevalence of Intimate Partners Violence (IPV) faced by women, which was further categorized into: (a) Psychological/emotional violence, (b) Physical violence, (c) Sexual violence, (d) Both combined and (e) Violence of any other type.

Qualitative data collection

Participants selection.

Purposeful sampling was done to recruit the participants for qualitative data collection. Participants included groups of married men and women aged between 18 to 49 years, groups of unmarried adolescent boys and girls aged between 14 to 21 years, and groups of healthcare professionals (HCPs), comprising of doctors, nurses, Lady Health Visitors (LHVs), Lady Health Workers (LHWs) and Community Midwives (CMWs). Ethics approval was obtained from the Aga Khan University, Ethics Review Committee.

Study sites

The selected study sites included two districts from Chitral (Upper and Lower Chitral), six districts from Gilgit (Gilgit, Ghizer, Hunza, Nagar, Astore, and Skardu), and two districts from Sindh (Matiari and Qambar Shadadkot). The following are the details of the data collection (Refer Table 1 ).

Data collection

Data were collected by conducting (IDIs) and (FGDs). The IDI and FGD interview guides were developed specifically for the study and reviewed based on the literature. IDIs were conducted with the healthcare industry administrators, Heads of the Departments (HODs), and HCPs of private and government health settings, including gynaecologists, LHWs, LHVs, and CMWs. The IDI interview guides comprised of the questions related to knowledge, sources of information, and attitudes regarding gender-based discrimination (how each gender is perceived in society and how physical and social differences in the roles of males and females affect an individual or society). The IDIs were conducted in Urdu and local language. The interviews were audio-recorded. Each IDIs lasted for 45–60 minutes.

Likewise, the FGDs were conducted using different interview guides, which were designed to assess the perception of adolescent girls and boys, married men and women and health care workers regarding gender discrimination in the society (perceptions of masculinity and femininity, and gender role expectations of a society). The FGDs were conducted in Urdu and local language. The interviews were audio-recorded. Each FGDs lasted for 60–120 minutes.

Data analysis

All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed in English. Training was provided to the data collectors, and they were supervised by the authors throughout the process to ensure transcriptions are written accurately and correctly, representing the actual data collected during interviews. Thematic analysis was carried out in four different steps. Firstly, manual analysis was done by the research team where transcriptions were thoroughly read, and codes were identified. These codes were combined according to their contextual similarity which followed the derivation of categories, based on which, themes were developed. Secondly, similar manual analysis was conducted by an expert data analyst. Thirdly, analysis was conducted using QSR NVivo 10. In the final step, all three analyses were combined and verified by the research team followed by the compilation of results.

Data integrity

To maintain the credibility or truthfulness of the data, the following strategies were used: (1) Prolonged engagement: Various distinct questions were asked related to the topic and participants were encouraged to share their statements with examples, (2) Triangulation: Data was analyzed by the author, expert data analyst and through QSR NVivo10, (3) Persistent observation: The authors read and reread the data, analyzed them recoded and relabeled codes and categories and revised the concepts accordingly, and (4) Transferability: The ability to generalize or transfer the findings to other context or settings, was ensured by explaining in detail the research context and its conclusions [ 6 ].

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics review committee (ERC), Aga Khan University. The ERC number is 2020-3606-11,489. To ensure voluntary participation of the study participants both verbal and written consent were obtained. For those who were younger than 18 years of age were given written assent, and their parent, or guardian’ verbally consented due to literacy issues. In addition to anonymity of the study participants were maintained by assigning codes to the study participants. To avoid loss of data, interview recordings were saved on a hard drive and in the email account of the author. The data on hard copies such as note pads used during IDIs and informed consents were kept in lock and key. All the data present in hard copy was scanned and saved in the hard drive with password protection. To ensure confidentiality, only the authors had access to hard and soft data of the study.

The studies selected were scrutinized to form a data extraction template with all the relevant data such as author, publication year, study title, purpose, design, setting, sampling, main results, perpetuating factors, and recommendations (Refer Table 2 , provided in the attachment). Most of the 20 studies included in the review were conducted in Pakistan however the most frequent study design was cross-sectional ( n = 9) followed by narrative research based on desk reviews ( n = 8), one was a case study, and two were cross-country comparison by using secondary data. Four studies were conducted in Province Punjab, three studies were conducted in KPK, and one in both KPK and Punjab. Only one study was conducted in Sindh province. The remaining used whole Pakistan in systematic review. The maximum sample size in a cross-sectional study was ( n = 506). Six major themes have emerged from the review which included (1) Status of Women in Society (2) Gender Inequality in Health (3) Gender Inequality in Education (4) Gender Inequality in Employment (5) Gender Biased Social Norms and Cultural Practices (6) Micro and Macro Level Recommendations.

Status of a woman in the society

The Pakistani women often face gender inequality [ 13 ]. Women are seen as a sexual object who are not allowed to take decision for self or their family. However, the male is seen as a symbol of power. Due to male ownership and the patriarchal structure of the Pakistani society women are submissive to men, their rights are ignored, and their identity is lost. Out of twenty, nine studies reported that a female can not take an independent decision, someone else decides on her behalf, mainly father before marriage then-husband and son [ 1 , 3 , 4 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 13 ]. The three studies report that women are not allowed to participate in elections or have very limited participation in politics. Furthermore, women often face inequalities and discrimination in access to health, education, and employment that have negative impact in their lives [ 1 , 2 ]. In addition, media often portrays women in the stereotyped role whose only responsibility is to look after the family and household chores [ 2 ]. Likewise, women have less access and control over financial and physical assets [ 13 ]. Similarly, in most of the low economic and tribal families’ women face verbal and physical abuse [ 8 ].

Gender inequality in health

Gender disparity in health is obvious in Pakistan. Women suffer from neglect of health and nutrition. They don’t have reproductive health rights, appropriate prenatal and postnatal care, and decision-making power for birth spacing those results in maternal mortality and morbidity [ 13 ]. Women can not take decision for her and her children’s health; she doesn’t have access to quality education and health services [ 13 , 15 ]. Furthermore, many papers report son preference [ 1 , 3 ]. Gender-based violence is also very common in Pakistan that leads to harmful consequences on the health and wellbeing of women [ 9 ].

Gender inequality in education

Low investment in girls’ education has been reported in almost all the papers reviewed. The major reason for low investment is low returns from girls, as boys are perceived to be potential head of the house and future bread winner [ 6 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 15 ]. One of the case study reports, people believe, Muslim women should be brought up in a way that they can fulfill the role of a good daughter, wife, and a mother; and education can have a “bad influence” to develop these characteristics in women [ 12 ]. If girls are educated, they become less obedient and evil and don’t take interest in household chores that is the primary responsibility of her [ 12 ]. Moreover, religious leaders have strong authority in rural areas. They often misuse Islamic teaching and educate parents that through education, women become independent and cannot become a good mother, daughter, and a wife. These teachings mostly hinder girl’s education. Other barriers in girls’ education are access to the facility and women’s safety. Five studies reported that most of the schools are on long distances and have co-education system that is perceived as un-Islamic. Parents are reluctant to send their daughters for education as they feel unsafe and threatened [ 1 , 4 , 12 , 13 , 15 ]. Poverty is another root cause of gender disparity in education, as parents cannot afford the education of their children and when there is a choice, preference is given to boys due to their perceived productive role in future. As a result, more dropouts and lower attainment of education by girls particularly living in rural areas [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 11 , 13 ].

Gender inequality in employment

Economic disparity due to gender inequality is an alarming issue in Pakistan. The low status of women in society, home care responsibilities, gender stereotyping, and social-cultural humiliated practices against women are the main hurdles in women’s growth and employment opportunities. Low education of females, restriction on mobility, lack of required skillsets, sex-segregated occupational choices are also big obstacles in the attainment of economic opportunities. Most of the women are out of employment, however those who are in economic stream are facing several challenges [ 7 ]. They face discrimination in all layers of the economy. Men are mostly on the leadership positions, fewer females are involved in decision making, wages are low for females if compared with males, workplace harassment and unfavourable work environment is common that hinders long stay in job [ 1 , 7 , 8 ]. Moreover, a study reported that in a patriarchal society very limited number of females are in business field and entrepreneurship. The main hurdles are capital unavailability, lack of role models, gender discrimination in business, cultural and local customs, and lack of training and education [ 8 ].

Gender biased social norms and cultural practices

The gender discrimination is deeply rooted in the Pakistani society. The gender disparity in Pakistan is evident at household level. It includes Distribution of food, education, health care, early and forced marriages, denial of inheritance right, mobility restriction, abuse, and violence [ 1 , 2 , 4 , 6 , 7 , 11 ]. Furthermore, birth of a boy child is celebrated, and the girl is seen as a burden. Likewise, household chores are duty of a female, and she cannot demand or expect any reward for it. On the other hand, male work has socio-economic value [ 2 , 7 , 15 ]. Furthermore, the female has limited decision making power and most of the decisions are done by male figures in a family or a leader of the tribe or community who is always a male. This patriarchal system is sustained and practiced under the name of Islamic teaching [ 2 , 12 , 13 ]. The prevalence of gender-based violence is also high, in form of verbal abuse, physical abuse, sexual assault, rape and forced sex, etc., In addition, it is usually considered a private matter and legal actions are not taken against it [ 8 ] . Moreover, Karo Kari or honor killing of a female is observed in Pakistan. It is justified as killing in the name of honor . Similarly, women face other forms of gender-based violence that include: (i) bride price (The family of the groom pay their future in-laws at the start of their marriage), (ii) Watta Satta (simultaneous marriage of a brother-sister pair from two households.), (iii) Vani (girls, often minors, are given in marriage or servitude to an aggrieved family as compensation to end disputes, often murder) and (iv) marriage with Quran (the male members of the families marry off their girl child to Holy Quran in order to take control of the property that legally belongs to the girl and would get transferred to her after marriage) [ 1 , 4 , 9 , 14 , 15 ]. Furthermore, the women are restricted to choose political career [ 13 ].

Micro and macro level recommendations

The women should have equal status and participation in all aspects of life that include, health, nutrition, education, employment, and politics [ 1 , 4 , 7 , 9 , 11 ]. Women empowerment should be reinforced at policy level [ 1 , 7 ]. For this, constitution of Pakistan should give equal rights to all citizens. Women should be educated about their rights [ 1 , 2 , 4 , 6 , 13 , 14 , 15 ]. To improve status of women, utmost intervention is an investment in girls education. If women is not educated she cannot fight for her rights. Gender parity can only be achieved if women is educated and allowed to participate in decision-making process of law and policies [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 9 , 11 , 14 ]. Similarly, access to health care services is women’s right. Quality education, adequate nutrition, antenatal and post-natal care services, skilled birth attendants, and access and awareness about contraceptives is important to improve women’s health and reduce maternal mortality.

Similarly, women should be given equal opportunities to take part in national development and economic activities of the country to reduce poverty. This is possible through fair employment opportunities, support in women’s own business, equitable policies at workplace and uniform wages and salaries. Besides these, female employees must be informed about their rights and privileges at workplace and employment [ 1 , 7 , 8 , 11 ]. Policy actions should be taken to increase the level of women’s participation in economic growth and entrepreneurship opportunities. There should be active actions to identify bottlenecks of gender parity and unlock growth potential of social institutions [ 5 ]. Another barrier for women empowerment is threatened and unsafe environment to thrive. There should be policies and legislation to protect women from harm, violence, and honor killing that ensure their health, safety, and wellbeing [ 4 , 12 ]. Educational institutions and mass media are two powerful sources that can bring change in society. Government must initiate mass media awareness campaign on gender discrimination at household level, educational institutes, and employment sectors to break discriminatory norms of patriarchal society and to reduce the monopoly of males in marketplace. Parent’s education on gender-equitable practices is also important to bring change at the microlevel. It includes gender-equitable child-rearing practices at home including boys mentoring because they think discrimination against females is a very normal practice and part of a culture [ 3 ]. There is insufficient data on women’s participation and gender parity in health, education, and employment. Thus, there is a strong need to identify effective interventions and relevant stakeholders to reduce the gender discrimination in Pakistan [ 5 ] .

Findings from primary data collection

The following are the major themes emerged from the primary data collection (Refer Table 3 ).

Theme 1: perception of women regarding gender discrimination in society

Woman as a sexual object.

Female participants highlighted that they are seen as “sexual objects” and “a mean of physical attraction” which prevents them from comfortably leaving their homes. One female participant explained this further as,

“We are asked to stay inside the house because men and boys would look at our body and may have bad intentions about us” (Adolescent girl, FGD).

Male participants echoed this narrative as they agreed that women are judged by their physical appearance, such as the shape of their bodies. A male participant stated,

“ Woman is a symbol of beauty and she's seen by the society as the symbol of sex for a man" (Male HCP, IDI).

A male participant reported,

“Women should cover themselves and stay inside the house” (married man, FGD).

One female participant verbalized,

“ We have breasts, and therefore, we are asked to dress properly". (adolescent girls, FGD).

Another stated,

“ Girls are supposed to dress properly and avoid eye contact with boys while walking on the road” (adolescent girls, FGD).

Women as dependent beings

One of the major study findings suggests the idea that women must be “helped” at all times, as they are naturally dependent upon other persons to protect them. One participant stated,

“If a woman is alone, she is afraid of the man's actions ” (adolescent girl, FGD).

Some female participants, however, agreed with this statement to some extent because they felt that men help women to fit into society. Oftentimes, judgment is passed for women without an accompanying male. Participants verbalized that wife cannot survive without husband and similarly daughter cannot live without her father. One participant mentioned,

“We are only allowed to go out when we have our father or brothers to accompany us” (Adolescent girl, FGD).

Other participants agreed with the sentiment differently. Since it is implied that men easily get attracted to women, having a male figure with female will protect her from naturally prying eyes. However, if she cannot be accompanied by a male, she must protect herself by covering fully and maintain distance with males.

Women’s autonomy

Female participants, especially young adolescent girls, shared how restrictions have affected their livelihoods. Participants expressed how easy it is for males to gain permission and leave the house, while females often have series of obstacles in front of them. A young girl stated,

“ There are lot of constraints when we see women in our culture. They must take care of everything at home, yet they must get everybody's permission to go five minutes away. Whereas a boy can go out of town and that too, without anyone’s permission. Looking at this, I wish I were a boy. I'd go wherever I want, and I could do whatever I want” (adolescent girl, FGD).

Males as an identity for females

Women are often identified through a prominent male figure in their life and are not considered to have individual personalities and identities. A female participant mentioned that,

“Woman is someone having a low status in society. People know her through their husband or father name” (married women, FGD).

Child’s upbringing responsibility

Culturally, it is expected from the female members of the family, often mothers, to rear children and take care of their upbringing. Male members, mainly fathers, are expected to look after finances. Thus, mothers usually take a greater portion of responsibility for child’s upbringing and blame in case of misconduct. A married woman explained that,

"If a girl does something, the mother is blamed for that. Even in our house, my mother-in-law talks to my mother if I argue or refuse for anything. This is the culture in my maiden home as well" (Married Woman, FGD).

Unrecognized contribution of women

Many female participants verbalized their concern for disregard they receive from their families despite contributing significantly. Women who perform major roles in maintaining the family and household chores are not recognized for their efforts. By doing cleaning, cooking and other duties, they keep family healthy and help keep costs low. One participant mentioned,

“If women don’t clean the house, it is extremely dirty. If women do not rear children, no one else would do it. We do so much for the family” (married woman, FGD).

Gender differences in daily activities

Both men and women struggle with self-expression as certain expectations from both genders hold people back from expressing their views and opinions. Men, for example, as indicated by participants, are expected to remain firm in challenging situations and not show emotions. Even for hobbies, participants shared that, parks and recreational activities are geared towards young boys and men, while girls and women are given more quiet and indoor activities. A female participant verbalized that,

“ Boys have a separate area where they play cricket and football daily but for girls like us, only indoor activities are arranged” (adolescent girl, FGD).

In places where males and females freely mix or live closely in one area, people often find themselves taking extra precautions in their actions, as to not be seen disgraceful by the community. One female participant reported,

“ Two communities are residing in our area. Events for females, such as sports day, are very rarely arranged. Even then we cannot fully enjoy because if we'll shout to cheer up other players, we would be scolded as our community is very cautious for portraying a soft image of females of our community ” (adolescent girl, FGD).

Another participant stated that,

“ After prayers, we cannot spend time with friends as people would point that girl and say that she always stays late after prayers to gossip when she is supposed to go home ” (adolescent girl, FGD).

Deprivation of women’s rights

A woman’s liberty has always struggled to be accepted and males are always favoured. Thus, women are given lower status. Participants highlighted that, in general, men are seen as superior to women. One participant stated,

“ Men are the masters of women…” (FGD married women).

On the other side, male suppress female liberty and women are unaware of their rights leaving them vulnerable to deprivation. A female participant explained,

“Women do not dominate society that's why people take away their rights from them” (married woman, FGD).

Female participants also shared that they see men as strong and dominant personalities, making them better decision makers regarding health care acquisition, family income, availing opportunities and producing offspring. One female participant verbalized,

“If there's one egg on the table and two children to be fed, it is considered that males should get it as it is believed that males need more nutrition than us” (HCP, IDI).

Another reported that,

“There is a lack of equal accessibility of health care facilities and lack of employment equality for women” (HCP, IDI).

Theme 2: perception of men regarding gender discrimination in society

Male dominance.

Inferiority and superiority are common phenomenon in Pakistan’s largely patriarchal society. This allows men to be seen as dominant, decision-maker of family and the sole bread winner. Women, however, are caught in a culture of subordination to men with little power over family and individual affairs. A female participant said,

“If we look at our society, men are dominant. They can do anything while a woman cannot, as she is afraid of the man's reactions [gussa] and aggression” (adolescent girl, FGD).

While another reported,

"In our society, husband makes his wife feel his superiority over her and would make her realize that it is him, who has all the authority and power” (married woman, FGD).

Preference for male child

There is often an extreme desire for birth of sons over daughters, which adds to the culture of gender discrimination in Pakistan. Male children are important to the family as they often serve their parents financially, once they are able. This is one of the main reasons that parents are more inclined towards birth of a male child rather than female. Consequently, education is prioritized for male children. Female participants expressed that their desire for a male child is to appease their husband’s family and reduce the pressure on her to fit in the house. According to a female participant,

“When my son was born, I was satisfied as now nobody would pressurize me. I noticed a huge difference in the behavior of my in-laws after I gave birth to my son. I felt I have an existence in their family” (married woman, FGD).

Participants highlighted that, women who have brothers are often more protected. According to a young participant,

“Brothers give us the confidence to move within the society because people think before saying anything about us” (adolescent girl, FGD).

Lack of communication among husband and wife

Married couples often lack communication and rarely discuss important matters with each other. Men often choose not to share issues with their wives as they believe they are not rational enough to understand the situation. A male participant stated,

“ Women are so sensitive to share anything. They can only reproduce and cook food inside the home” (married man, FGD).

Men are protectors

Many female participants considered men as a source of protection, as they manage finances and ensure safety of family members. They feel confident in man’s ability to contribute to their livelihoods. One participant mentioned,

“We go out when we have our father or brothers to accompany us” (Adolescent girl, FGD).

Another highlighted,

“Men are our protectors. We can only survive in the society because of them” (Married woman, FGD).

Theme 3: factors influencing gender discrimination

The role of family head.

A tight-knit family situation, difference of opinions, cultural values and generation gap can highly affect one’s view on gender. Participants highlighted the role of elders in the family who often favor their sons and male family members. Married women expressed that daughter in-laws often struggle to raise their voice or express their concerns in such family situation. One participant mentioned,

“We don’t take decisions on when to have the child or what method needs to be used for family planning. Our mothers-in-law decide and we must obey” (married woman, FGD).

The family system that often includes three generations living closely, allows traditional norms to carry forward, as opposed to a typical nuclear family. This includes attire, conduct, and relationships. One participant mentioned,

“I live with my mother-in-law. I must cover my head whenever I had to leave the house”. (Married woman, FGD).

Media influence

Media plays an important role in disseminating gender awareness. For example, advertisements of cooking oils and spices usually show young girls helping their mothers in kitchen, while men and boys are observed enjoying something else or not present. These short advertisements are impactful in perpetuating gender conduct solely for societal acceptance. One participant verbalized,

“Every household has a radio, on which different advertisements are going on. People get messages through media” (married man, FGD).

The study reveals that women are seen as sexual objects and therefore confined to their homes. Women are often judged on their physical appearance that hinders their autonomy in various aspects of life. Many women face difficulties in leaving their homes alone and require protection from men [ 3 ]. Men are, therefore, labeled as protectors while women are regarded as dependent beings who need man’s identity. The role of men inside the house is identified as authoritative, while women need approval from male because they are considered incapable of making appropriate decisions. Women are caretaker of their families and have primary responsibility of husband, children, and in-laws. However, these contributions are mostly unnoticed. These gender power differentials are so strong in households, that many women do not know their rights. Women comply with societal and cultural values that force them to become lesser beings in the society. Girls in society grow up and eventually adopt the traditional role of women [ 8 ]. Increased education and awareness level among communities can improve status of women in the Pakistani society [ 3 ].

Moreover, males have dominant role in the society [ 1 ]. Likewise, there is discrepancy in power structures between male and female in the family system that often leads to lack of communication especially between married couples as husbands do not share concerns with their wives nor ask for their advice, considering women incapable to understand anything [ 5 ].

Furthermore, a common phenomenon observed in the Pakistani society, is the strong desire for a male child, while the birth of a female child is mourned [ 5 ]. Girls are seen as a liability, while the birth of a male child is celebrated as it is believed that males will be the breadwinner of the family in the future [ 5 ]. Thus, preference for a male child leads to illegal termination of pregnancies with female fetuses in many situations [ 9 ]. In addition, some of the studies suggest that the preference for a son is significantly high in low socioeconomic areas if compared with the middle and upper ones. Men are seen as economic and social security providers of the household. Therefore, men are tagged as manhood in the society as it is considered that hierarchal familial structures are produced from them, and all powers are attributed to men. This increases the disparity of roles between men and women leading to gender discrimination [ 5 ]. Our study also reveals that media has important influence towards gender discrimination. It is commonly observed in the Pakistani TV advertisements, that household chores are mostly performed by women while men have professional roles in the society [ 6 ].

Thus, lack of female autonomy and empowerment are recognized as the major reasons of discrimination of women in our society. They do not have the means to participate in society, neither they are allowed to speak against traditions. Therefore, interventions are required to increase female autonomy and decision-making capacity. The other significant contributor to gender discrimination is male dominance, which must be brought down to empower women. To reduce this, communication is key between spouses, family members and community members. Gender discrimination has greater influence at different levels of Pakistani society. Certain schools and television advertisements portrays stereotypes, such as allowing boys to be active outdoors and forcing girls to remain indoors. Therefore, media channels and other public systems such as healthcare facilities and schooling systems must promote gender equity and equality. In terms of Sexual and Reproductive health (SRH), the health care facilities should play an important role in providing knowledge and effective treatment to both males and females. The SRH related services are often compromised for people due to lack of resources, staff, and attention. Schools and communities should play an important role in creating SRH related awareness among youth and adults that include puberty, pregnancy, and motherhood. SRH should also be made part of curriculum in educational institutes.

The use of group interviews allowed rapport development with communities. With multiple people present sharing similar views, many were inclined to give purposeful answers and recommendations regarding gender roles in communities. Based on previous literature searches, this study, to the best of our knowledge, has not been published in Pakistan at the community level. No other study explores the views of Pakistanis on gender discrimination with inclusion of multiple community groups and across multiple districts. In limitations, due to the topic’s sensitive topic, may have held back participants from answering fully and truthfully. Thus, considerable time was taken to develop trust and rapport. Therefore, it is possible that some study subjects might not have answered to the best of their ability. Furthermore, challenges were faced due to the COVID-19 pandemic and extreme weather conditions in some areas, as some participants could not reach the venue. Also, the lockdowns following the pandemic made it very difficult to gather 10–12 people at one place for the FGDs. Interviews could not be done virtually as the information was very sensitive.

Gender roles in Pakistani society are extremely complex and are transferred from generation to generation with minimal changes since ages. This study reveals some of the factors due to which women in Pakistan face gender discrimination. The cultural and societal values place women in a nurturing role in the Pakistani society. Through reinforcement of these roles by different family members, as well as by the dominant men in the society, women face adverse challenges to seek empowerment that will help them defy such repressive roles assigned to them. Gender discrimination is evident in public institutions such as healthcare facilities and schooling systems. Thus, administrative reorganization and improved awareness in the healthcare facilities, and appropriate education in schools for boys and girls will help decrease gender discrimination in the Pakistani societies.

Availability of data and materials

On request, the data will be available by hiding the IDs.

Though we have already provided the transcripts, yet there is a need of further information then kindly contact the corresponding author. Dr. Tazeen Saeed Ali: [email protected] .

Abbreviations

Aga Khan Foundation

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology

Intimate Partner Violence

Healthcare Professionals

Lady Health Visitors

Lady Health Workers

Community Midwives

In-Depth Interviews

Focus Group Discussions

Heads of the Departments

Sexual and Reproductive health

United Nations Population Fund

Ethics Review Committee

Iqbal H, Afzal S, Inayat M. Gender discrimination: implications for Pakistan security. IOSR J Humanit Soc Sci. 2012;1(4):16–25.

Article Google Scholar

Ejaz SS, Ara AA. Gender discrimination and the role of women in Pakistan. J Soc Sci Humanit. 2011;50(1):95–105.

Google Scholar

Delavande A, Zafar B. Gender discrimination and social identity: experimental evidence from urban Pakistan. FRB New York Staff Rep. 2013;593. Available at SSRN 2198386. 2013.

Bukhari MAHS, Gaho MGM, Soomro MKH. Gender inequality: problems & its solutions in Pakistan. Gov-Annu Res J Pol Sci. 2019;7(7):47–58.

Ferrant G, Kolev A. Does gender discrimination in social institutions matter for long-term growth?: cross-country evidence: EconPapers; 2016. Paris https://econpapers.repec.org/scripts/redir.pf?u=https%3A%2F%2Fdoi.org%2F10.1787%2F5jm2hz8dgls6-en;h=repec:oec:devaaa:330-en .

Kazimi AB, Shaikh MA, John S. Mothers role and perception in developing gender discrimination. Glob Polit Rev. 2019;4(2):20–8.

Alam A. Impact of gender discrimination on gender development and poverty alleviation. Sarhad J Agric. 2011;27(2):330–1.

Mahmood B, Sohail MM, Khalid S, Babak I. Gender-specific barriers to female entrepreneurs in Pakistan: a study in urban areas of Pakistan. J Educ Soc Behav Sci. 2012;2(4):339–52.

Tarar MG, Pulla V. Patriarchy, gender violence and poverty amongst Pakistani women: a social work inquiry. Int J Soc Work Hum Serv Pract. 2014;2(2):56–63.

Atif K, Ullah MZ, Afsheen A, Naqvi SAH, Raja ZA, Niazi SA. Son preference in Pakistan; a myth or reality. PakistanJ Med Sci. 2016;32(4):994.

Rabia M, Tanveer F, Gillani M, Naeem H, Akbar S. Gender inequality: a case study in Pakistan. Open J Soc Sci. 2019;7(03):369.

Shah S, Shah U. Girl education in rural Pakistan. Rev Int Sociol Educ. 2012;1(2):180–207.

Hamid A, Ahmed AM. An analysis of multi-dimensional gender inequality in Pakistan. Asian J Bus Manag. 2011;3(3):166–77.

Bhattacharya S. Status of women in Pakistan. J Res Soc Pakistan. 2014;51(1):179–211.

Butt BI, Asad AZ. Social policy and women status in Pakistan: a situation analysis. Orient Res J Soc Sci. 2016;1(1):47–62.

Khurshid N, Fiaz A, Khurshid J. Analyzing the impact of gender inequality on economic development in Pakistan: ARDL bound test cointegration analysis. Int J Econ Financ Issues. 2020;10(4):264–70.

Mahmood T, Aslam Shah P, Wasif NM. Sociological analysis of women’s empowerment in Pakistan. New Horiz. 2021;15(1):1–2.

Mumtaz S, Iqtadar S, Akther M, Niaz Z, Komal T, AbaidUllah S. Frequency and psychosocial determinants of gender discrimination regarding food distribution among families; 2022.

Li C, Ahmed N, Qalati S. Impact of gender-specific causes on women entrepreneurship: an opportunity structure for entrepreneurial women in rural areas. J Entrep Org Manag. 2022;8(1):2–10.

CAS Google Scholar

Ahmad A. Men’s perception of women regarding the internet usage in the Khyber agency Pakistan: an exploratory study. Global Mass Commun Rev. 2020;V(I):47–58.

Download references

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the research specialist, coordinator, and research associates for data collection, and the study participants for their time and valuable data. We would also like to appreciate and thank Mr. Adil Ali Saeed for helping us with the literature for the systematic review of the paper, and Ms. Amirah Nazir and Daman Dhunna for the overall cleaning of document. We are thankful to UNFPA and AKF for providing advisory and monitoring support. We would like to acknowledgment UNFPA Pakistan that through them the funding was received from Global Affairs Canada.

Global Affairs Canada (GAC). Project No: P006434; Arrangement #: 7414620.

Role of the funder: This is to declare that there was no role of the funding agency for planning and implementation of this study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Nursing and Midwifery, Aga Khan University, Stadium Road, P.O. Box 3500, Karachi, Pakistan

Tazeen Saeed Ali & Shahnaz Shahid Ali

Department of Community Health Sciences, Aga Khan University, Stadium Road, P.O. Box 3500, Karachi, Pakistan

Tazeen Saeed Ali

Aga Khan Health Services, Karachi, Pakistan

Sanober Nadeem & Falak Madhani

Center of Excellence Women & Child Health, Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan

Zahid Memon, Sajid Soofi & Shah Mohammad

Aga Khan Rural Service Pakistan, Gilgit, Pakistan

Yasmin Karim

Institute for Global Health, Karachi, Pakistan

Zulfiqar Ahmed Bhutta

Department of Paediatrics & Child Health, Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors have read and approved the manuscript. Their contribution is as follows: TSA contributed to proposal development, interview guide development, ERC approval, data supervision, data validation, systematic review, data analysis, manuscript development, and overall supervision. SSA assisted in proposal development, data collection supervision, data validation, systematic review, data analysis, and reviewed manuscript. SN, contributed in -literature Review, analysis of literature review and write up of findings. ZM reviewed interview guides, assisted in ERC approval, filed preparation for data collection, assisted in data validation and enhancing the approval processing, reviewed data analysis, and the final manuscript. SSA, contributed to proposal development, assisted in ERC approval, overall supervision, filed preparation for data collection and training of data collectors, assisted in data validation and enhancing the approval process and review of final manuscript. FM contributed to the interview guide development, facilitated field data collection, and contributed to the validation and analysis processes. Reviewed the final manuscript before submission. YK contributed to the interview guide development, facilitated field data collection, and contributed to the validation and analysis processes. Reviewed the final manuscript before submission. SM, contributed to proposal development, field preparation for data collection, validation, and review of the final manuscript. ZB, contributed to proposal development, brought the funding, assisted in ERC approval, overall supervision, data validation and enhancing the approval process and reviewed the final manuscript. He provided overall mentorship.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Tazeen Saeed Ali .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The ERC approval was taken from the Aga Khan University Ethics Review Committee for primary data collection. The ERC number is 2020-3606-11489. The written informed consent was taken from all the participants. For those who were younger than 18 years of age were given written assent, and their parent, or guardian verbally consented.

We declare that this is original research and all the authors have contributed to the proposal writing, funding management, data collection, analysis, and manuscript development.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Ali, T.S., Ali, S.S., Nadeem, S. et al. Perpetuation of gender discrimination in Pakistani society: results from a scoping review and qualitative study conducted in three provinces of Pakistan. BMC Women's Health 22 , 540 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-02011-6

Download citation

Received : 02 March 2022

Accepted : 16 October 2022

Published : 22 December 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-02011-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Gender discrimination

- Women discrimination

BMC Women's Health

ISSN: 1472-6874

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Advertisement

Gender Differences in Education: Are Girls Neglected in Pakistani Society?

- Published: 22 March 2023

Cite this article

- Humaira Kamal Pasha ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8894-5142 1 , 2

3636 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Differences in education between girls and boys persist in Pakistan, and the distribution of household resources and socioeconomic disparities are compounding the problem. This paper determines education attainment (primary to tertiary level) and current enrollment and explores underlying gender differences with reference to per capita income and socioeconomic characteristics of the household by using survey data of Pakistan (2005–2019) that have never been used in this context before. The potential endogeneity bias between income and education is addressed through the two-stage residual inclusion (2SRI) method that is appropriate for non-linear models used in this study. Findings indicate that income is likely to increase and facilitate a significant transition from primary- to tertiary-level education attainment. The boys have a higher likelihood to increase tertiary-level education attainment by household income. However, the probability of current enrollment is equivalent for girls and boys after controlling for endogeneity. The gender effects of Oaxaca-type decomposition indicate higher unexplained variation that describes a strong gender gap between boys and girls. The standard deviation for education inequality and gender gap ratio confirm that higher levels of discrimination and lower economic returns are associated with girls’ education, and individual and community attributes favor boys’ education. Findings suggest policies and educational strategies that focus on female education and lower-income households to build socioeconomic stability and sustainable human capital in the country.

Similar content being viewed by others

The impacts of gender inequality in education on economic growth in Tunisia: an empirical analysis

Khayria Karoui & Rochdi Feki

Predictors of the gender gap in household educational spending among school and college-going children in India

Rashmi Rashmi, Bijay Kumar Malik, … S. V. Subramanian

Gender Bias in Education in West Bengal

Amita Majumder & Chayanika Mitra

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

According to the Education for All (EFA) report, knowledge stimulates the stock of human capital in an economy (Karoui et al., 2018 ; Kim et al., 2021 ) and increases the probability of resources being equally distributed of regardless of gender, caste, color, or region (Heb, 2020 ; de Bruin et al., 2020 ). Gender equality in education is indispensable for developing countries like Pakistan which holds rich human capital to improve economic growth (Asif et al., 2019 ). The existence of patriarchy, cultural norms, regional conflicts, son preference, and traditional notions of womanhood regarding procreation, domestic chores, and early marriage have deep roots in society (Ashraf, 2018 ). All the impediments that women face have interconnected bases in prevailing gender differences and insufficient investment in education (Kleven et al., 2019 ) at the household and state level; these also negatively impact the economic growth in Pakistan (ur Rahman et al., 2018 ).

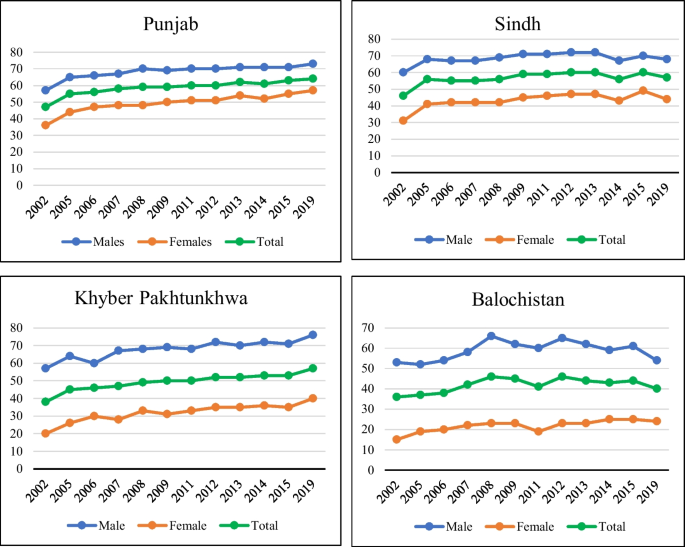

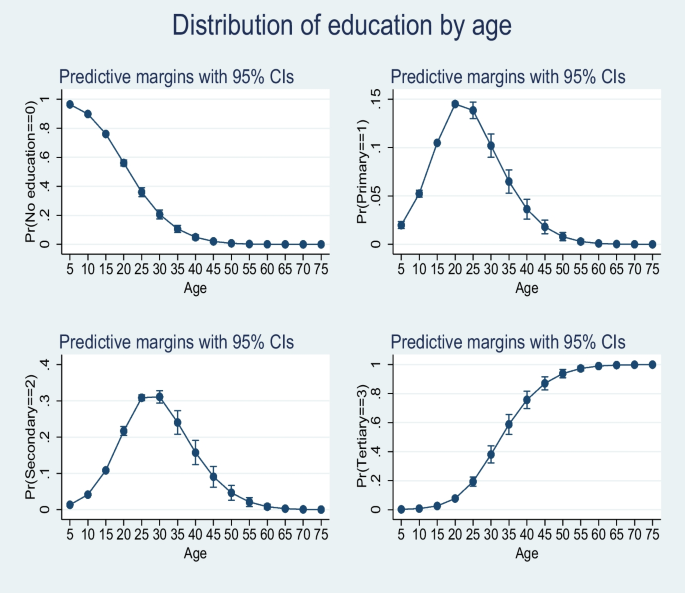

Some educational initiatives are working effectively in Pakistan but have not completely achieved. These include alternative learning programs (ALPs) for formal schools, digital innovations programs by the collaborations between UNICEF and UNESCO targeting the attainment of Sustainable Development Goals (Ministry of Federal Education, 2022), an EU partnership to implement a 5-year development program (Education Ministry of Balochistan, 2021), the Ilm- Possible Footnote 1 Project for Zero OOSC (out of school children), and equity-based critical learning (STEM, 2021). However, 22.84 million children of secondary school age have never enrolled in formal education (UNESCO Pakistan Country Strategic Document, 2018–2022). In addition, the literacy rate has declined from 62 to 58 % (World Bank Statistics, 2022) that has increased global inequality (Paris21 Strategy Agenda, 2030). This situation raises the question as to whether existing educational policies and projects are adequate for curbing the gender inequality in different provinces of Pakistan (see Fig. 1 ).

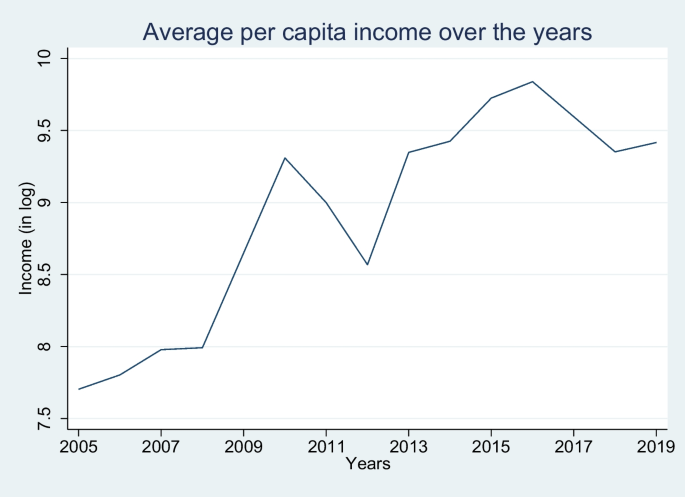

Literacy rate by province and gender in Pakistan. Source: Author construction based on data from PSLM Bureau of Statistics, Pakistan. Figure 2 displays the trend of per capita income from 2005 to 2019, one of the inevitable indicators of educational achievement. The statistics calculate a sharp drop in per capita income after 2010, which improved in 2012 but eventually declined after 2016

The country has been ranked 151 out of 153 countries by the Gender Parity Index. It has also been found that 21 % of boys and 32 % of girls in primary education have experienced gender-based discrimination (Human Rights Watch, 2018). Likewise, boys are 15 % more likely to have the opportunity to go to school than girls, as boys are viewed as financial assets by their parents. Evidently, if household income is equally distributed, girls perform outclass in grades (Yi et al., 2015 ), provide higher marginal returns to education (Whalley & Zhao, 2013 ), and achieve sustainable environment (Heb, 2020 ). The economic benefits that result from female education are as high as those that result from male education (Minasyan et al., 2019 ; Sen et al., 2019 ), particularly in relation to the achievement of tertiary education (Alfalih et al., 2021 ; Wu et al., 2020 ). In addition, although Pakistan has the largest young population in Asia, approximately 80 % of the female population has never participated in the labor market, and 130 million girls (those aged between 6 and 17 years) have never attended any form of educational institution (World Bank, 2020). Nevertheless, the latent demand for schooling remains associated with the socioeconomic status and purchasing power of the household (Asif et al., 2019 ). Likewise, parental and household treatment effects can formulate considerable gender gap that requires thorough investigation at micro level.

The aim of this study is to examine the relationship between gender differences in education and household income in Pakistan. Measuring gender differences with the help of microdata and through the use of qualitative and quantitative approaches is not easy in studies of human capital development (Najeeb, 2020 ). Nor is the investigation of the circumstances that lead to more investment in a male child than a female child a straightforward matter. Findings in this area remain inconclusive, which demonstrates a lack of research conducted at the household level in Pakistan (Minasyan, 2019 ). In addition, many studies of the effect of household income on education suffer from bias-related issues which arise as a result of measurement errors and spurious relationships. Some studies use corresponding variables, such as permanent income (Kingdon, 2005 ), or ignore endogeneity while controlling for children’s cognitive skills (Chevalier et al., 2002 ). Others deal with potential endogeneity by examining sector- or community-based union membership (Chevalier, 2013 ), government tax changes (Paul, 2002 ), and rented or owned lands with the caution of the weak instrument (Okabe, 2016 ).

This study determines education achievement using ordered logit and logit models by two outcome variables: education attainment (categorical variable) and current enrollment (binary variable). It seeks to examine the causes of the prevailing gender differences in Pakistan by examining the per capita income and socioeconomic characteristics of households. This study attempts to deal with underlying potential endogeneity using a novel approach for a non-linear model and examines extant inequalities and gender effects within households. This study finds a positive and robust relationship between gender and education attainment, and the significant transformation from primary- to tertiary-level education by per capita income of the household; this contradicts the results of Munshi ( 2017 ). The findings are significantly negative with regard to the relationship between gender and current enrollment, which is opposite to the findings of the study by Maitra ( 2003 ). After dealing with potential endogeneity using the two-stage residual inclusion (2SRI afterwards) method, the results contradict those of prior studies (Chevalier et al., 2002 ; Maitra, 2003 ), and they establish a clear link between education and income along with other socioeconomic characteristics. The findings show that inequalities in education, at the micro level, exert a more powerful impact on girls than boys in relation to reducing education attainment and current enrollment. Gender decomposition reveals that individual and community attributes favor boys’ education over that of girls.

This study contributes to the literature in the following ways. Firstly, there is a risk that the factors that influence education achievement remain mis-specified due to the fact that limited information is available about children’s environments and family structures. This is why it is vital to focus on the determinants of human capital at the micro level. Most existing studies focus on the role of education and the impact of gender inequalities in relation to their impact on economic growth across countries (Assoumou-Ella, 2019 ; Evans et al., 2021 ), within country at the macro level (Rammohan et al., 2018 ), and focus on only one education level (Lloyd et al., 2005 ). This study is the first to attempt to highlight the importance of the gender gap in relation to education attainment and current enrollment and confirm whether it exists or not. It does so by examining the link between per capita income and the socioeconomic characteristics of households using a repeated cross-sectional dataset that has not achieved much academic attention from scholars in relation to the country of Pakistan. Secondly, this study develops an empirical strategy for non-linear model to address the potential endogeneity by using 2SRI approach that remain ignored mostly. It exploits exogenous variations using income shocks, windfall income, and non-labor resources to examine the potential endogeneity between income and education (Banzragch et al., 2019 ; Chevalier et al., 2002 ). Lastly, while previous studies have argued that gender inequality influences economic growth (Kopnina, 2020 ), some of these studies contain troubling contradictions (Sirine, 2015 ), some do not find that gender inequality affects economic growth to a considerable degree (Maitra, 2003 ), and some investigate its unidirectional effect (Tansel & Bodur, 2012 ). This study captures discriminations effect in education investment in boys and girls by education inequalities and gender decomposition estimated at household level. It also adopts alternative specifications of gender inequalities to examine economic returns on education.

The rest of this study is structured as follows. The “Literature Review” section explains the importance of gender equality with reference to previous studies. The “Methodology and Data” section describes the methodology and the data used in this study. The “Empirical Results and Discussion” section presents the results and analysis, and the “Conclusion and Policy Implications” section concludes the study while also discussing policy implications and the limitations of the study.

Literature Review

Education is an essential element of the Cobb–Douglas production function (Saleem et al., 2019 ) that can improve human capital, promote economic growth, and curb poverty in the long term (Arshed et al., 2019 ). Many countries have experienced improvements in enrollment rates; however, their economic growth appears difficult to achieve. This mechanism of human capital can be revisited and revised by focusing on the equal distribution of education in economic and sustainable approach (Livingstone, 2018 ). The study of Duflo et al. ( 2021 ) examines the impact of free secondary education on gains in economic welfare after the completion the target of UPE (universal primary education). They use data relating to secondary high schools from 54 districts in Ghana to examine 1500 students enrolled in a scholarship program. They find that the program increased secondary-level education attainment by 27 % and further resulted in better learning skills and lower rates of early marriage and reduced fertility rates among girls. This suggests a potential movement toward the more equal treatment of the genders within households. However, they did not find any significant influence of education attainment on future employment. Using the Barro-Lee dataset of education attainment, Evans et al. ( 2021 ) estimate the gender gap and its effects on long-term economic growth. Instead taking the gender gap ratio, it prefers to employ difference of the education attainment between men and women. Their findings indicate that low levels of education in women are the reason why the gender gap has become so pronounced in many countries. This gap is revealed to be highly correlated with the age of the women and per capita income.

The study by Kopnina ( 2020 ) discusses the sustainable educational goals that are indispensable for progressive universal education and economic growth. It reveals alternative measures that might influence the circular economy and argues that gender differences will decrease as a result of investment in female education. It endorses the use of the term “empowerment education,” and particularly to refer to females who remain unempowered with regard to their financial independence and social status. They propose the direct influence of female education on the food patterns, efficient consumption of household and natural resources, and renewable energy that can handle growing population in a sustainable approach. Likewise, the study of de Bruin et al. ( 2020 ) finds that education and income can promote sustainability and reduce gender inequality. They use age, education, and different types of work to analyze the gender-differentiated impact of these factors on economic change.

Another study, that of Rammohan et al. ( 2018 ), examines gender disparity in education using district-level data in India and ordinary least squares (OLS) regression. To do so, they use data related to the gender gap between male and female education attainment, GDP per capita, and ethnicity. Their study finds that those living in wealthier districts are more inclined toward educating their daughters than those living in poor ones. Sahoo and Klasen ( 2021 ) focused on female participation in the STEM streams by using the variables: female, siblings, age, parental education, test scores, household size, and ethnicity. They reveal that girls are 20 % less likely to enroll in STEM streams than boys. The plausible explanation for lower female participation is associated with parental preferences and income disparity in the household. Maitra ( 2003 ) uses a probit model and a censored probit model simultaneously and finds that there is no gender difference in the current enrollment rates of boys and girls (6–12 years) but that there is a higher gap in relation to grade attainment for girls (13–24). The data used is from the Matlab Health and Socio-Economic Survey (MHSS) of rural Bangladesh, which surveys 149 villages. The explanatory variables include religion, household size, number of siblings, the head of the household’s education level and occupation, a log of per adult household expenditure, and household characteristics such as the number of bedrooms, access to water and a toilet, and the availability of electricity. The endogeneity issue of the income has dealt by taking the residual term of the log of the adult expenditure in the household.

The study of Davis et al. ( 2019 ) uses the World Value Survey (1981–2014) to capture individual effects on women’s status. They argue that individual decision-making can increase women’s education attainment, their choice to bear a child, and advance economic sustainability such as urbanization and the provision of basic necessities. The above effects provide economic benefits that further support gender equality and discourage the traditional role of women in the society. Robb et al. ( 2012 ) examine the gender differences in education attainment using data about university graduates and an ordered probit model. They find that female students perform better than their male counterparts but that they are less likely to obtain a first-class degree. It is shown that factors such as the type of institution, individual abilities, and the choice of subjects are not the reason for gender inequality; however, the effects of these factors increase the gender gap in relation to educational performance. The predict probabilities of their study explain that the likelihood that female students will attain a first-class degree is 5 %, compared with 8 % for male students. Other studies also advocate that reducing gender differences in education achievement can have transitional and long-term effects on women’s empowerment (Kabeer, 2021 ), legal protection (Durrani et al., 2018 ), employment (Najeeb et al., 2020 ), and sustainable growth (Heb, 2020 ).

Prior Literature in the Context of Pakistan

In the context of Pakistan, Ashraf et al. ( 2018 ) apply Dickey–Fuller generalized least squares (DF-GLS) to examine the impact of secondary school attainment on gender inequality. They employ multiple sources of data about Pakistan, namely, economic surveys, the National Assembly of Pakistan database, and the Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement (PSLM) survey. They use the Gender Inequality Index (GII) as the dependent variable. The findings show that economic deprivation can decrease women’s participation in the labor force and their education attainment. Notably, the external or spillover effects of education attainment on gender inequality are also crucial to understanding the lower purchasing power of the household. Qureshi ( 2007 ) conducts a bivariate regression analysis using the Learning and Educational Achievements in Punjab Schools (LEAPS) dataset to investigate whether the education attainment of an older sister impacts on the education attainment of younger children in the household. Mainly, it describes a spillover effect in education that remains unnoticed to receive its maximum economic benefit. It takes into account age, the father’s education level, the household head’s education level, the number of children, the infrastructure of the household, the regional languages, and the number of the districts in the province. The findings reveal 0.2 % of years of schooling increases in youngers boys by the older educated sister that can be the potential human capital in the future labor market. However, their study fails to analyze the spillover effect that an educated older brother has on a younger sister.

The study of Asif et al. ( 2019 ) demonstrates that the strong and significant impact of investment in education without gender bias creates other avenues for sustainable growth in Pakistan. Likewise, some studies investigate education investment to explore other dimensions including welfare gains in relation to eradicating hunger (Ali et al., 2021 ), the awareness of climate change by energy consumption and recyclable goods (Ali et al., 2019 ), the transformation of society into one with equal rights and zero violence (Durrani et al., 2018 ), the female leadership in entrepreneurial decision-making (Shaheen and Ahmad, 2022 ), and the voluntary effort toward food security and patterns of daily life (Qazlbash et al., 2021 ). Mahmood et al. ( 2012 ) use time-series data (1971–2009) to investigate the relationship between human capital investment and economic growth. In their work, autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) and OLS models show a positive relationship between high enrollment rates in education and economic growth rates in the short and long term.

A similar strategy is proposed by Zaman ( 2010 ), who also suggests that there is a correlation between female education and economic development. Interestingly, Lloyd et al. ( 2005 ) find that parents tend to prefer that girls and boys attend separate schools; however, availability of primary schools and type of school (public or private) also play key roles. The study of ur Rahman et al. ( 2018 ) finds that a solution to the vicious cycle of poverty comes in the form of increasing the education level of a household. By using logistic regression, they find a negative relationship between education and poverty in Pakistan. They emphasize the role of education plays in providing potential human capital for the labor market and even generating new and improved employment opportunities that result in better living standards and economic well-being. However, a key issue with regard to the aforementioned studies is that they do not propose well-specified econometric strategies with that can be implemented to tackle gender differences in education, while others fail to address the potential endogeneity in non-linear models and some remain unable to decompose gender effects within the household.

Methodology and Data

Data and variables.

This study uses repeated cross-sectional data from the PSLM survey conducted by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS) of the Government of Pakistan for the seven fully available rounds from 2005 to 2019 (2005–2006, 2007–2008, 2010–2011, 2011–2012, 2013–2014, 2015–2016, and 2018–2019). The survey was designed to provide social and economic indicators at the provincial and district level; starting in 2004, the survey aims to accurately describe the country. The sample size of the PSLM surveys is approximately 80,000 households. The total number of observations after pooling the data is 1,011,849.

This study uses two models for alternative measurements of the education achievement of boys and girls; the first model is education attainment (the highest completed schooling; aged 9–24 years), and the second model is current enrollment (aged 5–24 years). The boys and girls are restricted in first model to the 9–15, 16–19, and 20–24 age groups for primary-, secondary-, and tertiary-level education attainment, respectively. The following criteria are considered: additional year for class repetition by the students, late admission into schools, the completion standards of the Pakistan education system, and traditional age requirements for entering in school adopted in past studies (Maitra et al., 2003 ). In addition, boys and girls are restricted to not having the status of head or working person. In the first model, education attainment is a categorical outcome variable examines by the ordered logit model that can be defined as:

In the second model, current enrollment is a dichotomous outcome variable examines by logit model that can be described as:

The explanatory variables include dummy variables of the gender and age of boys and girls depending on models. Age is represented by a linear and quadratic term to control for birth cohort effects and capture non-linearity effects on education achievement. As age is directly proportional in contributing to cognitive skills and human capital, age square indicates marginal returns from age that decrease over time.

Other explanatory variables include the marital status of the household members (Kingdon, 2005 ). This study uses a series of dummy variables for the education level of individuals including the head of the household, parents, and other members of the household (i.e., those older than 24). This is because a joint-family structure is the majority form of family structure in Pakistan, and the head of the household is usually not the father but rather any elderly family member. Likewise, head’s personal treatment and decision-making influence on the education achievement. In addition, using parental education instead of maternal education is also feasible for gender difference analysis to avoid the issue of multicollinearity. Several tests are run to check for multicollinearity, including the variance inflation factor (VIF) and correlation matrix. The VIF for each predictor variable should be less than 10. It is 7.02 for the education attainment model and 4.12 for current enrollment model. Footnote 2 The siblings’ variable is used to control the reciprocal relationship between quantity and quality of education (Hazarika, 2001 ; Maitra, 2003 ). Occupational heterogeneity is controlled by different household members’ professions (McNabb, 2002 ) ranging from high-salaried (officer) to low-salaried (laborer) professions.

The variable of interest in this study is the per capita income of the household. It represents the household’s possible investment in education, which can maximize economic returns and minimize gender inequality. The availability of electricity, gas, and broadband internet access is a proxy for household infrastructure and technology advancement. The latter is of interest as it may impact on digital education, sustainable development, and the urgency of the micro- and macro-crisis such as health. The high demand to shift education from formal to virtual platforms during the COVID-19 pandemic has opened up new dimensions with regard to the acquisition of skills and knowledge. The other control variables consist of the dependency ratio, household size, ownership of house and any establishment other than agricultural land (ur Rahman et al., 2018 ), and ownership of the cultivating land for the personal use of the household (Sawada, 2009 ). Finally, community characteristics are controlled by including dummy variables for locations and number of the provinces of the country (Hazarika, 2001 ).

Empirical Strategy

The concept of the ordered logit model for education attainment is to incorporate intermediate continuous variable says y in the latent regression accompanied by the observed ( x i ) explanatory variables and the unobserved error term ( ε i ). The range of y is divided in adjacent intervals that comprise four categories—namely, 0 = no education, 1 = primary education, 2 = secondary education, and 3 = tertiary education—related to latent variable ( Y ∗ ). The structural model for latent education is:

where β is the vector of the parameters to be estimated; ε is the disturbance term, which is assumed to be independent across observations; and y ∗ can take value with observations.

For the discrete choices, the following are observing as:

Where Y is the category of education attainment, and τ denotes the threshold parameters, explaining the transition from one category of education attainment to another category. Consequently, τ must satisfy the rule according to τ 0 < τ 1 < τ 2 < τ 3 , as the ε i is logistically distributed. The resulting probabilities can be observed as:

Hence, the probability of outcome can imply as:

whereas the log likelihood function for ordered logistic regression is:

The function formulates the ordered logit model with multiple equations, whereas each equation presents the logit model (Williams, 2005 ). The econometric model is therefore:

Endogeneity Bias