- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- Patient Perspectives

- Methods Corner

- ESC Content Collections

- Author Guidelines

- Instructions for reviewers

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Read & Publish

- About European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing

- About ACNAP

- About European Society of Cardiology

- ESC Publications

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, why patient journey mapping, how is patient journey mapping conducted, use of technology in patient journey mapping, future implications for patient journey mapping, conclusions, patient journey mapping: emerging methods for understanding and improving patient experiences of health systems and services.

Lemma N Bulto and Ellen Davies Shared first authorship.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Lemma N Bulto, Ellen Davies, Janet Kelly, Jeroen M Hendriks, Patient journey mapping: emerging methods for understanding and improving patient experiences of health systems and services, European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing , 2024;, zvae012, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjcn/zvae012

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Patient journey mapping is an emerging field of research that uses various methods to map and report evidence relating to patient experiences and interactions with healthcare providers, services, and systems. This research often involves the development of visual, narrative, and descriptive maps or tables, which describe patient journeys and transitions into, through, and out of health services. This methods corner paper presents an overview of how patient journey mapping has been conducted within the health sector, providing cardiovascular examples. It introduces six key steps for conducting patient journey mapping and describes the opportunities and benefits of using patient journey mapping and future implications of using this approach.

Acquire an understanding of patient journey mapping and the methods and steps employed.

Examine practical and clinical examples in which patient journey mapping has been adopted in cardiac care to explore the perspectives and experiences of patients, family members, and healthcare professionals.

Quality and safety guidelines in healthcare services are increasingly encouraging and mandating engagement of patients, clients, and consumers in partnerships. 1 The aim of many of these partnerships is to consider how health services can be improved, in relation to accessibility, service delivery, discharge, and referral. 2 , 3 Patient journey mapping is a research approach increasingly being adopted to explore these experiences in healthcare. 3

a patient-oriented project that has been undertaken to better understand barriers, facilitators, experiences, interactions with services and/or outcomes for individuals and/or their carers, and family members as they enter, navigate, experience and exit one or more services in a health system by documenting elements of the journey to produce a visual or descriptive map. 3

It is an emerging field with a clear patient-centred focus, as opposed to studies that track patient flow, demand, and movement. As a general principle, patient journey mapping projects will provide evidence of patient perspectives and highlight experiences through the patient and consumer lens.

Patient journey mapping can provide significant insights that enable responsive and context-specific strategies for improving patient healthcare experiences and outcomes to be designed and implemented. 3–6 These improvements can occur at the individual patient, model of care, and/or health system level. As with other emerging methodologies, questions have been raised regarding exactly how patient journey mapping projects can best be designed, conducted, and reported. 3

In this methods paper, we provide an overview of patient journey mapping as an emergent field of research, including reasons that mapping patient journeys might be considered, methods that can be adopted, the principles that can guide patient journey mapping data collection and analysis, and considerations for reporting findings and recognizing the implications of findings. We summarize and draw on five cardiovascular patient journey mapping projects, as examples.

One of the most appealing elements of the patient journey mapping field of research is its focus on illuminating the lived experiences of patients and/or their family members, and the health professionals caring for them, methodically and purposefully. Patient journey mapping has an ability to provide detailed information about patient experiences, gaps in health services, and barriers and facilitators for access to health services. This information can be used independently, or alongside information from larger data sets, to adapt and improve models of care relevant to the population that is being investigated. 3

To date, the most frequent reason for adopting this approach is to inform health service redesign and improvement. 3 , 7 , 8 Other reasons have included: (i) to develop a deeper understanding of a person’s entire journey through health systems; 3 (ii) to identify delays in diagnosis or treatment (often described as bottlenecks); 9 (iii) to identify gaps in care and unmet needs; (iv) to evaluate continuity of care across health services and regions; 10 (v) to understand and evaluate the comprehensiveness of care; 11 (vi) to understand how people are navigating health systems and services; and (vii) to compare patient experiences with practice guidelines and standards of care.

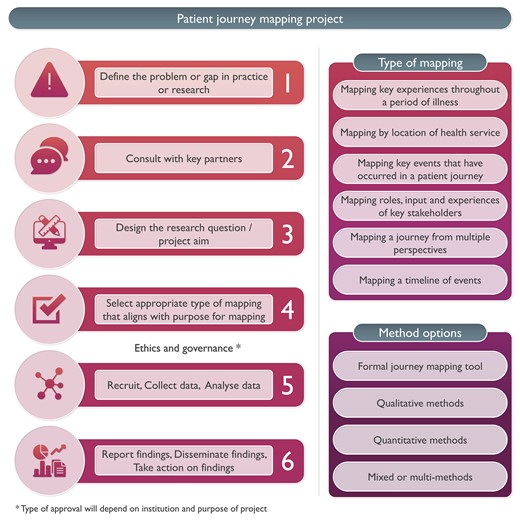

Patient journey mapping approaches frequently use six broad steps that help facilitate the preparation and execution of research projects. These are outlined in the Central illustration . We acknowledge that not all patient journey mapping approaches will follow the order outlined in the Central illustration , but all steps need to be considered at some point throughout each project to ensure that research is undertaken rigorously, appropriately, and in alignment with best practice research principles.

Steps for conducing patient journey mapping.

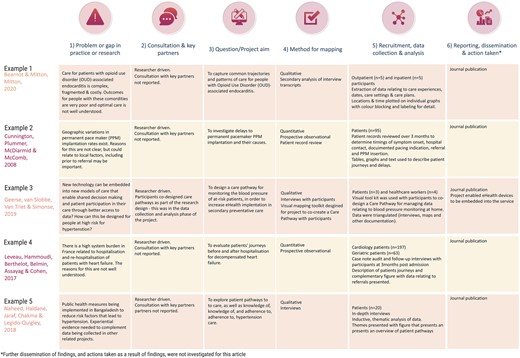

Five cardiovascular patient journey mapping research examples have been included in Figure 1 , 12–16 to provide specific context and illustrate these six steps. For each of these examples, the problem or gap in practice or research, consultation processes, research question or aim, type of mapping, methods, and reporting of findings have been extracted. Each of these steps is then discussed, using these cardiovascular examples.

Examples of patient journey mapping projects.

Define the problem or gap in practice or research

Developing an understanding of a problem or gap in practice is essential for facilitating the design and development of quality research projects. In the examples outlined in Figure 1 , it is evident that clinical variation or system gaps have been explored using patient journey mapping. In the first two examples, populations known to have health vulnerabilities were explored—in Example 1, this related to comorbid substance use and physical illness, 13 and in Example 2, this related to geographical location. 13 Broader systems and societal gaps were explored in Examples 4 and 5, respectively, 15 , 16 and in Example 3, a new technologically driven solution for an existing model of care was tested for its ability to improve patient outcomes relating to hypertension. 14

Consultation, engagement, and partnership

Ideally, consultation with heathcare providers and/or patients would occur when the problem or gap in practice or research is being defined. This is a key principle of co-designed research. 17 Numerous existing frameworks for supporting patient involvement in research have been designed and were recently documented and explored in a systematic review by Greenhalgh et al . 18 While none of the five example studies included this step in the initial phase of the project, it is increasingly being undertaken in patient partnership projects internationally (e.g. in renal care). 17 If not in the project conceptualization phase, consultation may occur during the data collection or analysis phase, as demonstrated in Example 3, where a care pathway was co-created with participants. 14 We refer readers to Greenhalgh’s systematic review as a starting point for considering suitable frameworks for engaging participants in consultation, partnership, and co-design of patient journey mapping projects. 18

Design the research question/project aim

Conducting patient journey mapping research requires a thoughtful and systematic approach to adequately capture the complexity of the healthcare experience. First, the research objectives and questions should be clearly defined. Aspects of the patient journey that will be explored need to be identified. Then, a robust approach must be developed, taking into account whether qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods are more appropriate for the objectives of the study.

For example, in the cardiac examples in Figure 1 , the broad aims included mapping existing pathways through health services where there were known problems 12 , 13 , 15 , 16 and documenting the co-creation of a new care pathway using quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods. 14

In traditional studies, questions that might be addressed in the area of patient movement in health systems include data collected through the health systems databases, such as ‘What is the length of stay for x population’, or ‘What is the door to balloon time in this hospital?’ In contrast, patient mapping journey studies will approach asking questions about experiences that require data from patients and their family members, e.g. ‘What is the impact on you of your length of stay?’, ‘What was your experience in being assessed and undergoing treatment for your chest pain?’, ‘What was your experience supporting this patient during their cardiac admission and discharge?’

Select appropriate type of mapping

The methods chosen for mapping need to align with the identified purpose for mapping and the aim or question that was designed in Step 3. A range of research methods have been used in patient journey mapping projects involving various qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods techniques and tools. 4 Some approaches use traditional forms of data collection, such as short-form and long-form patient interviews, focus groups, and direct patient observations. 18 , 19 Other approaches use patient journey mapping tools, designed and used with specific cultural groups, such as First Nations peoples using artwork, paintings, sand trays, and photovoice. 17 , 20 In the cardiovascular examples presented in Figure 1 , both qualitative and quantitative methods have been used, with interviews, patient record reviews, and observational techniques adopted to map patient journeys.

In a recent scoping review investigating patient journey mapping across all health care settings and specialities, six types of patient journey mapping were identified. 3 These included (i) mapping key experiences throughout a period of illness; (ii) mapping by location of health service; (iii) mapping by events that occurred throughout a period of illness; (iv) mapping roles, input, and experiences of key stakeholders throughout patient journeys; (v) mapping a journey from multiple perspectives; and (vi) mapping a timeline of events. 3 Combinations or variations of these may be used in cardiovascular settings in the future, depending on the research question, and the reasons mapping is being undertaken.

Recruit, collect data, and analyse data

The majority of health-focused patient journey mapping projects published to date have recruited <50 participants. 3 Projects with fewer participants tend to be qualitative in nature. In the cardiovascular examples provided in Figure 1 , participant numbers range from 7 14 to 260. 15 The 3 studies with <20 participants were qualitative, 12 , 14 , 16 and the 2 with 95 and 260 participants, respectively, were quantitative. 13 , 15 As seen in these and wider patient journey mapping examples, 3 participants may include patients, relatives, carers, healthcare professionals, or other stakeholders, as required, to meet the study objectives. These different participant perspectives may be analysed within each participant group and/or across the wider cohort to provide insights into experiences, and the contextual factors that shape these experiences.

The approach chosen for data collection and analysis will vary and depends on the research question. What differentiates data analysis in patient journey mapping studies from other qualitative or quantitative studies is the focus on describing, defining, or exploring the journey from a patient’s, rather than a health service, perspective. Dimensions that may, therefore, be highlighted in the analysis include timing of service access, duration of delays to service access, physical location of services relative to a patient’s home, comparison of care received vs. benchmarked care, placing focus on the patient perspective.

The mapping of individual patient journeys may take place during data collection with the use of mapping templates (tables, diagrams, and figures) and/or later in the analysis phase with the use of inductive or deductive analysis, mapping tables, or frameworks. These have been characterized and visually represented in a recent scoping review. 3 Representations of patient journeys can also be constructed through a secondary analysis of previously collected data. In these instances, qualitative data (i.e. interviews and focus group transcripts) have been re-analysed to understand whether a patient journey narrative can be extracted and reported. Undertaking these projects triggers a new research cycle involving the six steps outlined in the Central illustration . The difference in these instances is that the data are already collected for Step 5.

Report findings, disseminate findings, and take action on findings

A standardized, formal reporting guideline for patient journey mapping research does not currently exist. As argued in Davies et al ., 3 a dedicated reporting guide for patient journey mapping would be ill-advised, given the diversity of approaches and methods that have been adopted in this field. Our recommendation is for projects to be reported in accordance with formal guidelines that best align with the research methods that have been adopted. For example, COREQ may be used for patient journey mapping where qualitative methods have been used. 20 STROBE may be used for patient journey mapping where quantitative methods have been used. 21 Whichever methods have been adopted, reporting of projects should be transparent, rigorous, and contain enough detail to the extent that the principles of transparency, trustworthiness, and reproducibility are upheld. 3

Dissemination of research findings needs to include the research, healthcare, and broader communities. Dissemination methods may include academic publications, conference presentations, and communication with relevant stakeholders including healthcare professionals, policymakers, and patient advocacy groups. Based on the findings and identified insights, stakeholders can collaboratively design and implement interventions, programmes, or improvements in healthcare delivery that overcome the identified challenges directly and address and improve the overall patient experience. This cyclical process can hopefully produce research that not only informs but also leads to tangible improvements in healthcare practice and policy.

Patient journey mapping is typically a hands-on process, relying on surveys, interviews, and observational research. The technology that supports this research has, to date, included word processing software, and data analysis packages, such as NVivo, SPSS, and Stata. With the advent of more sophisticated technological tools, such as electronic health records, data analytics programmes, and patient tracking systems, healthcare providers and researchers can potentially use this technology to complement and enhance patient journey mapping research. 19 , 20 , 22 There are existing examples where technology has been harnessed in patient journey. Lee et al . used patient journey mapping to verify disease treatment data from the perspective of the patient, and then the authors developed a mobile prototype that organizes and visualizes personal health information according to the patient-centred journey map. They used a visualization approach for analysing medical information in personal health management and examined the medical information representation of seven mobile health apps that were used by patients and individuals. The apps provide easy access to patient health information; they primarily import data from the hospital database, without the need for patients to create their own medical records and information. 23

In another example, Wauben et al. 19 used radio frequency identification technology (a wireless system that is able to track a patient journey), as a component of their patient journey mapping project, to track surgical day care patients to increase patient flow, reduce wait times, and improve patient and staff satisfaction.

Patient journey mapping has emerged as a valuable research methodology in healthcare, providing a comprehensive and patient-centric approach to understanding the entire spectrum of a patient’s experience within the healthcare system. Future implications of this methodology are promising, particularly for transforming and redesigning healthcare delivery and improving patient outcomes. The impact may be most profound in the following key areas:

Personalized, patient-centred care : The methodology allows healthcare providers to gain deep insights into individual patient experiences. This information can be leveraged to deliver personalized, patient-centric care, based on the needs, values, and preferences of each patient, and aligned with guideline recommendations, healthcare professionals can tailor interventions and treatment plans to optimize patient and clinical outcomes.

Enhanced communication, collaboration, and co-design : Mapping patient interactions with health professionals and journeys within and across health services enables specific gaps in communication and collaboration to be highlighted and potentially informs responsive strategies for improvement. Ideally, these strategies would be co-designed with patients and health professionals, leading to improved care co-ordination and healthcare experience and outcomes.

Patient engagement and empowerment : When patients are invited to share their health journey experiences, and see visual or written representations of their journeys, they may come to understand their own health situation more deeply. Potentially, this may lead to increased health literacy, renewed adherence to treatment plans, and/or self-management of chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease. Given these benefits, we recommend that patients be provided with the findings of research and quality improvement projects with which they are involved, to close the loop, and to ensure that the findings are appropriately disseminated.

Patient journey mapping is an emerging field of research. Methods used in patient journey mapping projects have varied quite significantly; however, there are common research processes that can be followed to produce high-quality, insightful, and valuable research outputs. Insights gained from patient journey mapping can facilitate the identification of areas for enhancement within healthcare systems and inform the design of patient-centric solutions that prioritize the quality of care and patient outcomes, and patient satisfaction. Using patient journey mapping research can enable healthcare providers to forge stronger patient–provider relationships and co-design improved health service quality, patient experiences, and outcomes.

None declared.

Farmer J , Bigby C , Davis H , Carlisle K , Kenny A , Huysmans R , et al. The state of health services partnering with consumers: evidence from an online survey of Australian health services . BMC Health Serv Res 2018 ; 18 : 628 .

Google Scholar

Kelly J , Dwyer J , Mackean T , O’Donnell K , Willis E . Coproducing Aboriginal patient journey mapping tools for improved quality and coordination of care . Aust J Prim Health 2017 ; 23 : 536 – 542 .

Davies EL , Bulto LN , Walsh A , Pollock D , Langton VM , Laing RE , et al. Reporting and conducting patient journey mapping research in healthcare: a scoping review . J Adv Nurs 2023 ; 79 : 83 – 100 .

Ly S , Runacres F , Poon P . Journey mapping as a novel approach to healthcare: a qualitative mixed methods study in palliative care . BMC Health Serv Res 2021 ; 21 : 915 .

Arias M , Rojas E , Aguirre S , Cornejo F , Munoz-Gama J , Sepúlveda M , et al. Mapping the patient’s journey in healthcare through process mining . Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020 ; 17 : 6586 .

Natale V , Pruette C , Gerohristodoulos K , Scheimann A , Allen L , Kim JM , et al. Journey mapping to improve patient-family experience and teamwork: applying a systems thinking tool to a pediatric ambulatory clinic . Qual Manag Health Care 2023 ; 32 : 61 – 64 .

Cherif E , Martin-Verdier E , Rochette C . Investigating the healthcare pathway through patients’ experience and profiles: implications for breast cancer healthcare providers . BMC Health Serv Res 2020 ; 20 : 735 .

Gilburt H , Drummond C , Sinclair J . Navigating the alcohol treatment pathway: a qualitative study from the service users’ perspective . Alcohol Alcohol 2015 ; 50 : 444 – 450 .

Gichuhi S , Kabiru J , M’Bongo Zindamoyen A , Rono H , Ollando E , Wachira J , et al. Delay along the care-seeking journey of patients with ocular surface squamous neoplasia in Kenya . BMC Health Serv Res 2017 ; 17 : 485 .

Borycki EM , Kushniruk AW , Wagner E , Kletke R . Patient journey mapping: integrating digital technologies into the journey . Knowl Manag E-Learn 2020 ; 12 : 521 – 535 .

Barton E , Freeman T , Baum F , Javanparast S , Lawless A . The feasibility and potential use of case-tracked client journeys in primary healthcare: a pilot study . BMJ Open 2019 ; 9 : e024419 .

Bearnot B , Mitton JA . “You’re always jumping through hoops”: journey mapping the care experiences of individuals with opioid use disorder-associated endocarditis . J Addict Med 2020 ; 14 : 494 – 501 .

Cunnington MS , Plummer CJ , McDiarmid AK , McComb JM . The patient journey from symptom onset to pacemaker implantation . QJM 2008 ; 101 : 955 – 960 .

Geerse C , van Slobbe C , van Triet E , Simonse L . Design of a care pathway for preventive blood pressure monitoring: qualitative study . JMIR Cardio 2019 ; 3 : e13048 .

Laveau F , Hammoudi N , Berthelot E , Belmin J , Assayag P , Cohen A , et al. Patient journey in decompensated heart failure: an analysis in departments of cardiology and geriatrics in the Greater Paris University Hospitals . Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2017 ; 110 : 42 – 50 .

Naheed A , Haldane V , Jafar TH , Chakma N , Legido-Quigley H . Patient pathways and perceptions of treatment, management, and control Bangladesh: a qualitative study . Patient Prefer Adherence 2018 ; 12 : 1437 – 1449 .

Bateman S , Arnold-Chamney M , Jesudason S , Lester R , McDonald S , O’Donnell K , et al. Real ways of working together: co-creating meaningful Aboriginal community consultations to advance kidney care . Aust N Z J Public Health 2022 ; 46 : 614 – 621 .

Greenhalgh T , Hinton L , Finlay T , Macfarlane A , Fahy N , Clyde B , et al. Frameworks for supporting patient and public involvement in research: systematic review and co-design pilot . Health Expect 2019 ; 22 : 785 – 801 .

Wauben LSGL , Guédon ACP , de Korne DF , van den Dobbelsteen JJ . Tracking surgical day care patients using RFID technology . BMJ Innov 2015 ; 1 : 59 – 66 .

Tong A , Sainsbury P , Craig J . Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups . Int J Qual Health Care 2007 ; 19 : 349 – 357 .

von Elm E , Altman DG , Egger M , Pocock SJ , Gøtzsche PC , Vandenbroucke JP , et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies . Lancet 2007 ; 370 (9596): 1453 – 1457 .

Wilson A , Mackean T , Withall L , Willis EM , Pearson O , Hayes C , et al. Protocols for an Aboriginal-led, multi-methods study of the role of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers, practitioners and Liaison officers in quality acute health care . J Aust Indigenous HealthInfoNet 2022 ; 3 : 1 – 15 .

Lee B , Lee J , Cho Y , Shin Y , Oh C , Park H , et al. Visualisation of information using patient journey maps for a mobile health application . Appl Sci 2023 ; 13 : 6067 .

Author notes

- cardiovascular system

- health personnel

- health services

- health care systems

- narrative discourse

Email alerts

Related articles in pubmed, citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1873-1953

- Print ISSN 1474-5151

- Copyright © 2024 European Society of Cardiology

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Patients’ Lived Experiences During the Transplant and Cellular Therapy Journey pp 9–17 Cite as

Creating a Patient-Centered Case Study

- Jennifer Holl 5 ,

- Lisa Wesinger 6 ,

- Judi Gentes 7 ,

- Carissa Morton 8 &

- Jean Coffey 9

- First Online: 25 August 2023

61 Accesses

Case studies provide an invaluable record of professional clinical practice and have been used in medicine since the late 1800s to describe both traditional and unusual presentations of specific disease pathologies. In medicine, case studies traditionally take a detached, objective approach to outlining the clinical course of a disease and its treatment. In keeping with the holistic approach to patient care found in nursing and using the theoretical foundations established in Jean Watson’s Theory of Human Caring as well as the Relationship-Based Care Model, this research team sought to revolutionize the case study paradigm and deconstruct the traditional case study approach, placing the patient, instead of the provider, at the center of the narrative. This new case study method intercalates the clinicians’ analysis of the case with the patient’s commentary. This chapter outlines the methods and theoretical underpinnings used to create a patient-centered case study and seeks to provide nurses with a creative alternative to the traditional, objective case study approach. Implications for future research include whether using patient-centered case studies, instead of traditional case studies, provide a valuable learning tool to educate nurses.

- Qualitative research

- Phenomenology

- Relationship-based care

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Bergen A, While A. A case for case studies: exploring the use of case study design in community nursing research. J Adv Nurs. 2000;31(4):926–34.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Benner P. Interpretive phenomenology. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1994.

Google Scholar

Gary JC, Hudson CE. Reverse engineering: strategy to teach evidence-based practice to online RN-to-BSN students. Nurse Educ. 2016;41(2):83–5.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Koloroutis M, editor. Relationship-based care: a model for transforming practice. Minneapolis: Creative Health Care Management; 2004.

Luck L, Jackson D, Usher K. Case study: a bridge across the paradigms. Nurs Inq. 2006;13(2):103–9.

Meyer CB. A case in case study methodology. Field Methods. 2001;13:329–52.

Article Google Scholar

Noble H, Smith J. Issues of validity and reliability in qualitative research. Evid Based Nurs. 2015;18(2):34–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2015-102054 .

Polit DF, Beck CT. Essentials of nursing research: appraising evidence for nursing practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014.

Smith J, Flowers P, Larkin M. Interpretative phenomenological analysis: theory, method and research. London: Sage; 2013.

Taylor R, Thomas-Gregory A. Case study research. Nurs Stand. 2015;29(41):36–40.

Watson J. Nursing: the philosophy and science of caring. Rev. ed. Boulder: University Press of Colorado; 2008.

Yin RK. Case study research: design and methods. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2014.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Hematology/Oncology, Dartmouth Health, Lebanon, NH, USA

Jennifer Holl

Transplant and Cellular Therapy, Dartmouth Health, Lebanon, NH, USA

Lisa Wesinger

Oncology/Hematology, Dartmouth Health, Lebanon, NH, USA

Judi Gentes

Dartmouth Health, Dartmouth Cancer Center, St. Johnsbury, VT, USA

Carissa Morton

School of Nursing, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, USA

Jean Coffey

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jean Coffey .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Dartmouth Health, Dartmouth–Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, NH, USA

John M. Hill Jr.

School Nursing, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, USA

Thomas Long

Elizabeth B. McGrath

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Holl, J., Wesinger, L., Gentes, J., Morton, C., Coffey, J. (2023). Creating a Patient-Centered Case Study. In: Coffey, J., Hill Jr., J.M., Long, T., McGrath, E.B. (eds) Patients’ Lived Experiences During the Transplant and Cellular Therapy Journey. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-25602-8_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-25602-8_2

Published : 25 August 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-25601-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-25602-8

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 04 December 2019

“Patient Journeys”: improving care by patient involvement

- Matt Bolz-Johnson 1 ,

- Jelena Meek 2 &

- Nicoline Hoogerbrugge 2

European Journal of Human Genetics volume 28 , pages 141–143 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

24k Accesses

18 Citations

25 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cancer genetics

- Cancer screening

- Cancer therapy

- Health policy

“I will not be ashamed to say ‘ I don’t know’ , nor will I fail to call in my colleagues…”. For centuries this quotation from the Hippocratic oath, has been taken by medical doctors. But what if there are no other healthcare professionals to call in, and the person with the most experience of the disease is sitting right in front of you: ‘ your patient ’.

This scenario is uncomfortably common for patients living with a rare disease when seeking out health care. They are fraught by many hurdles along their health care pathway. From diagnosis to treatment and follow-up, their healthcare pathway is defined by a fog of uncertainties, lack of effective treatments and a multitude of dead-ends. This is the prevailing situation for many because for rare diseases expertise is limited and knowledge is scarce. Currently different initiatives to involve patients in developing clinical guidelines have been taken [ 1 ], however there is no common method that successfully integrates their experience and needs of living with a rare disease into development of healthcare services.

Even though listening to the expertise of a single patient is valuable and important, this will not resolve the uncertainties most rare disease patients are currently facing. To improve care for rare diseases we must draw on all the available knowledge, both from professional experts and patients, in order to improve care for every single patient in the world.

Patient experience and satisfaction have been demonstrated to be the single most important aspect in assessing the quality of healthcare [ 2 ], and has even been shown to be a predictor of survival rates [ 3 ]. Studies have evidenced that patient involvement in the design, evaluation and designation of healthcare services, improves the relevance and quality of the services, as well as improves their ability to meet patient needs [ 4 , 5 , 6 ]. Essentially, to be able to involve patients, the hurdles in communication and initial preconceptions between medical doctors and their patients need to be resolved [ 7 ].

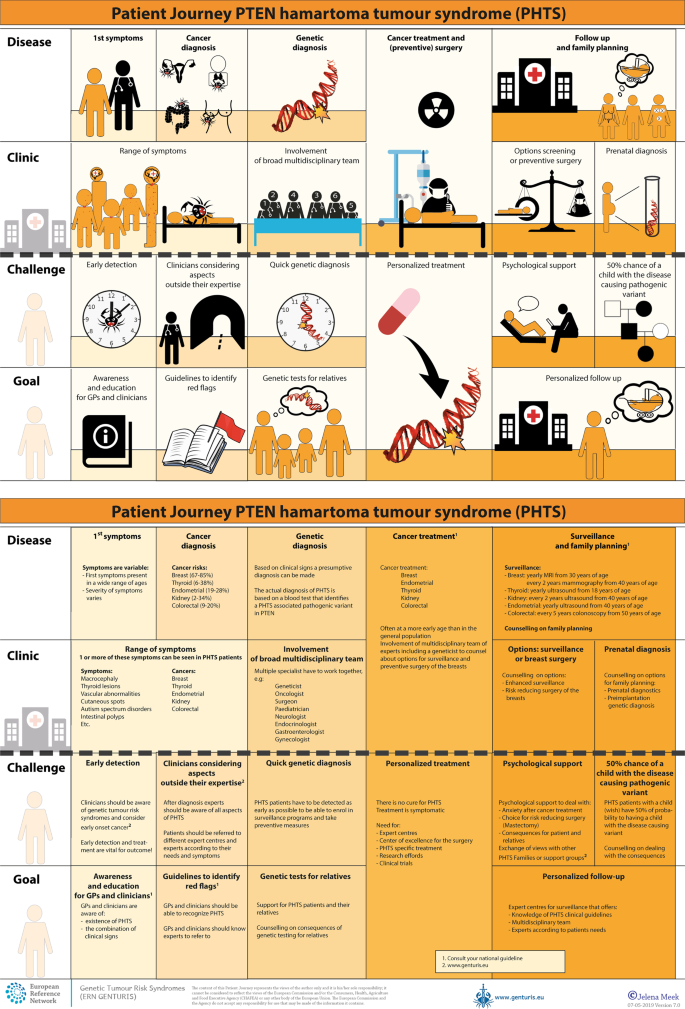

To tackle the current hurdles in complex or rare diseases, European Reference Networks (ERN) have been implemented since March 2017. The goal of these networks is to connect experts across Europe, harnessing their collective experience and expertise, facilitating the knowledge to travel instead of the patient. ERN GENTURIS is the Network leading on genetic tumour risk syndromes (genturis), which are inherited disorders which strongly predispose to the development of tumours [ 8 ]. They share similar challenges: delay in diagnosis, lack of cancer prevention for patients and healthy relatives, and therapeutic. To overcome the hurdles every patient faces, ERN GENTURIS ( www.genturis.eu ) has developed an innovative visual approach for patient input into the Network, to share their expertise and experience: “Patient Journeys” (Fig. 1 ).

Example of a Patient Journey: PTEN Hamartoma Tumour Syndrome (also called Cowden Syndrome), including legend page ( www.genturis.eu )

The “Patient Journey” seeks to identify the needs that are common for all ‘ genturis syndromes ’, and those that are specific to individual syndromes. To achieve this, patient representatives completed a mapping exercise of the needs of each rare inherited syndrome they represent, across the different stages of the Patient Journey. The “Patient Journey” connects professional expert guidelines—with foreseen medical interventions, screening, treatment—with patient needs –both medical and psychological. Each “Patient Journey” is divided in several stages that are considered inherent to the specific disease. Each stage in the journey is referenced under three levels: clinical presentation, challenges and needs identified by patients, and their goal to improve care. The final Patient Journey is reviewed by both patients and professional experts. By visualizing this in a comprehensive manner, patients and their caregivers are able to discuss the individual needs of the patient, while keeping in mind the expertise of both professional and patient leads. Together they seek to achieve the same goal: improving care for every patient with a genetic tumour risk syndrome.

The Patient Journeys encourage experts to look into national guidelines. In addition, they identify a great need for evidence-based European guidelines, facilitating equal care to all rare patients. ERN GENTURIS has already developed Patient Journeys for the following rare diseases ( www.genturis.eu ):

PTEN hamartoma tumour syndrome (PHTS) (Fig. 1 )

Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC)

Lynch syndrome

Neurofibromatosis Type 1

Neurofibromatosis Type 2

Schwannomatosis

A “Patient Journey” is a personal testimony that reflects the needs of patients in two key reference documents—an accessible visual overview, supported by a detailed information matrix. The journey shows in a comprehensive way the goals that are recognized by both patients and clinical experts. Therefore, it can be used by both these parties to explain the clinical pathway: professional experts can explain to newly identified patients how the clinical pathway generally looks like, whereas their patients can identify their specific needs within these pathways. Moreover, the Patient Journeys could serve as a guide for patients who may want to write, in collaboration with local clinicians, diaries of their journeys. Subsequently, these clinical diaries can be discussed with the clinician and patient representatives. Professionals coming across medical obstacles during the patient journey can contact professional experts in the ERN GENTURIS, while patients can contact the expert patient representatives from this ERN ( www.genturis.eu ). Finally, the “Patient Journeys” will be valuable in sharing knowledge with the clinical community as a whole.

Our aim is that medical doctors confronted with rare diseases, by using Patient Journeys, can also rely on the knowledge of the much broader community of expert professionals and expert patients.

Armstrong MJ, Mullins CD, Gronseth GS, Gagliardi AR. Recommendations for patient engagement in guideline development panels: a qualitative focus group study of guideline-naive patients. PloS ONE 2017;12:e0174329.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gupta D, Rodeghier M, Lis CG. Patient satisfaction with service quality as a predictor of survival outcomes in breast cancer. Supportive Care Cancer Off J Multinatl Assoc Supportive Care Cancer. 2014;22:129–34.

Google Scholar

Gupta D, Lis CG, Rodeghier M. Can patient experience with service quality predict survival in colorectal cancer? J Healthc Qual Off Publ Natl Assoc Healthc Qual. 2013;35:37–43.

Sharma AE, Knox M, Mleczko VL, Olayiwola JN. The impact of patient advisors on healthcare outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:693.

Fonhus MS, Dalsbo TK, Johansen M, Fretheim A, Skirbekk H, Flottorp SA. Patient-mediated interventions to improve professional practice. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;9:Cd012472.

PubMed Google Scholar

Cornman DH, White CM. AHRQ methods for effective health care. Discerning the perception and impact of patients involved in evidence-based practice center key informant interviews. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2017.

Chalmers JD, Timothy A, Polverino E, Almagro M, Ruddy T, Powell P, et al. Patient participation in ERS guidelines and research projects: the EMBARC experience. Breathe (Sheff, Engl). 2017;13:194–207.

Article Google Scholar

Vos JR, Giepmans L, Rohl C, Geverink N, Hoogerbrugge N. Boosting care and knowledge about hereditary cancer: european reference network on genetic tumour risk syndromes. Fam Cancer 2019;18:281–4.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

This work is generated within the European Reference Network on Genetic Tumour Risk Syndromes – FPA No. 739547. The authors thank all ERN GENTURIS Members and patient representatives for their work on the Patient Journeys (see www.genturis.eu ).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

SquareRootThinking and EURORDIS – Rare Diseases Europe, Paris, France

Matt Bolz-Johnson

Human Genetics, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

Jelena Meek & Nicoline Hoogerbrugge

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Nicoline Hoogerbrugge .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Bolz-Johnson, M., Meek, J. & Hoogerbrugge, N. “Patient Journeys”: improving care by patient involvement. Eur J Hum Genet 28 , 141–143 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-019-0555-6

Download citation

Received : 07 August 2019

Revised : 04 October 2019

Accepted : 01 November 2019

Published : 04 December 2019

Issue Date : February 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-019-0555-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Care trajectories of surgically treated patients with a prolactinoma: why did they opt for surgery.

- Victoria R. van Trigt

- Ingrid M. Zandbergen

- Nienke R. Biermasz

Pituitary (2023)

Designing rare disease care pathways in the Republic of Ireland: a co-operative model

- E. P. Treacy

Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases (2022)

Rare disease education in Europe and beyond: time to act

- Birute Tumiene

- Harm Peters

- Gareth Baynam

Development of a patient journey map for people living with cervical dystonia

- Monika Benson

- Alberto Albanese

- Holm Graessner

Der klinische Versorgungspfad zur multiprofessionellen Versorgung seltener Erkrankungen in der Pädiatrie – Ergebnisse aus dem Projekt TRANSLATE-NAMSE

- Daniela Choukair

- Min Ae Lee-Kirsch

- Peter Burgard

Monatsschrift Kinderheilkunde (2022)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Open access

- Published: 31 August 2023

The hospital-to-home care transition experience of home care clients: an exploratory study using patient journey mapping

- Marianne Saragosa 1 , 2 ,

- Sonia Nizzer 2 ,

- Sandra McKay 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 &

- Kerry Kuluski 7 , 8

BMC Health Services Research volume 23 , Article number: 934 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

1801 Accesses

Metrics details

Care transitions have a significant impact on patient health outcomes and care experience. However, there is limited research on how clients receiving care in the home care sector experience the hospital-to-home transition. An essential strategy for improving client care and experience is through client engagement efforts. The study's aim was to provide insight into the care transition experiences and perspectives of home care clients and caregivers of those receiving home care who experienced a hospital admission and returned to home care services by thematically and illustratively mapping their collective journey.

This study applied a qualitative descriptive exploratory design using a patient journey mapping approach. Home care clients and their caregivers with a recent experience of a hospital discharge back to the community were recruited. A conventional inductive approach to analysis enabled the identification of categories and a collective patient journey map. Follow-up interviews supported the validation of the map.

Seven participants (five clients and two caregivers) participated in 11 interviews. Participants contributed to the production of a collective journey map and the following four categories and themes: (1) Touchpoints as interactions with the health system; Life is changing ; (2) Pain points as barriers in the health system: Sensing nobody is listening and Trying to find a good fit ; (3) Facilitators to positive care transitions: Developing relationships and gaining some continuity and Trying to advocate, and (4) Emotional impact: Having only so much emotional capacity .

Conclusions

The patient journey map enabled a collective illustration of the care transition depicted in touchpoints, pain points, enablers, and feelings experienced by home care recipients and their caregivers. Patient journey mapping offers an opportunity to acknowledge home care clients and their caregivers as critical to quality care delivery across the continuum.

Peer Review reports

In 2021 nearly 921,700 Canadian households reported accessing formal home care [ 1 ]. The general population uses home care services for various needs, such as recovery after hospital discharge, supporting end-of-life care, or managing chronic conditions, disabilities, or mental illnesses. Internationally, variations exist within and between countries in home care organization, policies, and availability of services [ 2 ], and targeted population groups within home care systems [ 3 , 4 ]. With the population aging and citizens living with disability, reliance on the home care system in combination with substantial care by unpaid caregivers enables people to live safely in their own homes. While most home care recipients (hereafter referred to as ‘client’) are 65 years and older, home care services are also provided to adults with long-term disabilities younger than 65 years [ 1 ].

Hospitalization and the period immediately following hospital discharge are particularly critical periods. The Canadian Institute for Health Information reports that 9.3% of patients discharged from the hospital are readmitted within 30 days [ 5 ]. Factors cited as predictors of readmission include hospital length of stay, patient acuity, and comorbidity [ 6 ]. Patient-reported challenges that arise during the hospital-to-home care transition require further exploration.

Understanding patient experience is important and is increasingly recognized as a quality measure, clinical effectiveness, and patient safety [ 7 ]. Patient experience is a multifaceted concept that spans a range of patient health setting/environment experiences, including lived and care experiences, clinical interactions, organizational features of care, and process measures [ 8 ]. Despite more attention on patient experience, it remains understudied in the formal home care sector [ 9 ]. The care transition experience in home care clients also requires more attention [ 10 ]. Client engagement efforts are an important strategy for improving client care and experience. Client engagement describes a partnership of clients, families, and health care professionals working together to improve the client experience [ 11 ]. Previous home care research has reported on client interest in direct care and care planning and less so on broader organizational improvement efforts [ 11 ]. However, through structured processes and engaging with older adults as experts in their lived experiences it is possible for community-dwelling service recipients to be partners in bettering health care services [ 12 ].

Journey mapping is a research approach that evolved from the market research industry to gain insight into how patients navigate and experience complex health services and systems [ 13 , 14 , 15 ]. As a “patient-oriented” activity, patient journey mapping is undertaken to understand the barriers, facilitators, experiences, and interactions with services or providers for those entering, navigating, and exiting a health system by documenting and producing an illustrated map [ 13 ]. Of the existing literature, patient journey mapping has been effectively used to understand the patient experience [ 16 , 17 , 18 ], improve the quality of care [ 7 , 19 ], and for informing health service redesign/improvement [ 13 , 15 , 20 ]. Journey maps go beyond a static view of patients' perspectives by illustrating key moments in a patient’s journey, including important touchpoints, pain points, and the emotions experienced [ 7 , 21 ]. For home care clients, mapping their journey from the hospital to home in a concise and visually compelling story may shed light on the multi-level barriers and challenges that they face, and has the potential to inspire new initiatives that improve the client experience. Using patient journey mapping, this study aimed to understand and characterize the care transition experiences for home care clients and unpaid caregivers after they transition from hospital to home with home care services. The objective of this study is to use patient journey mapping to characterize home care clients and caregivers’ experiences of home care services after transitioning from hospital to home.

Study design and setting

To achieve this aim, we used a qualitative descriptive exploratory design with a patient journey mapping approach. The study involved a large-scale not-for-profit charitable organization providing home care and support services in select Southern Ontario urban regions in Canada. For the purposes of this study, we recruited clients being served by the home care agency within one of the urban regions that provides both in-home personal and nursing care services. The Health Sciences Research Ethics Board of the University of Toronto (REB Human Protocol #31,494) provided ethics approval for this study.

Participants and data collection

We applied a purposeful sampling strategy using pre-determined selection criteria to identify and recruit potential participants. We approached clients if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) recipient of home care services from the aforementioned organization during the study period; (2) experienced a hospital admission and transitioned back home with home care upon discharge in 2021; (3) living in the community (i.e., private home, retirement home or assisted living setting that offers support services to help maintain independence); (4) aged 18 or older; (5) ability to provide informed consent and communicate verbally; (6) were not receiving palliative care; and (7) the ability to communicate in conversational English. Similarly, caregivers could be involved if they could communicate in English and self-identify as unpaid or privately paid caregivers to a home care client who met the abovementioned inclusion criteria. Unpaid family and friend caregivers and privately paid caregiver supports were required to be working with older adults living independently in their home [ 22 ]. Caregivers were recruited after clients were enrolled in the study using the same targeted measures as clients. We targeted only clients who resumed home care services, given that this enabled us to identify and invite them to participate in the study.

Three recruitment strategies were used including: social media, digital, and mailout. First, the home care organization’s client digital newsletter promoted the study through an electronic post encouraging interested clients to contact the researcher. Second, a master list of clients that were previously admitted to hospital and resumed home care services between January 1, 2021, to November 15, 2021, was generated from the organization’s administrative database. A study invitation letter was sent to potential study participants either electronically or by mail using the master list of clients, depending on the availability of the email address on file, starting with the most recently documented hospital holds in November 2021. In keeping with previous literature on hospital-to-home transitions, the aim was to conduct initial interviews between two and four weeks post-discharge [ 23 ]. A longer timespan between hospital discharge and the first client interview (i.e., > 45 days) could negatively impact clients’ ability to recall events [ 24 ]. Prospective participants contacted the researcher via email or phone to share their interest in the study. Once it was determined that potential participants met the inclusion criteria, they received the consent form for their review by email and provided informed verbal consent prior to data collection.

The study team delineated two distinct data collection phases:

Phase 1: Initial interview : During the initial interview, the first author (MS) verbally collected demographic information and asked questions about the home—hospital—home care trajectory. Using a semi-structured interview guide, interview questions covered topics such as the precipitating factors to the care transition, what worked well and what was missing in terms of services and how care was delivered, and touchpoints with providers and services along the way. Examples of patient journey mapping interview guides were used to develop interview questions [ 13 , 25 , 26 ]. Further, the interview guide was piloted with a client partner with lived experience transitioning from hospital-to-home to ensure the questions were clear and relevant. As themes began to emerge during interviews, the semi-structured interview questions were modified using probing questions to gather more in-depth descriptions of emerging themes.

Phase 2: Follow-up interview : Interviews were analyzed after the first interview and findings from phase 1 were used to create a patient journey map. The same participants were then invited to participate in a follow-up interview to review the journey map [aggregated client-level data], validate its content, suggest changes, and discuss how challenges along their journey could be addressed. If they agreed to participate in the second interview, they received the draft patient journey map through email or mail beforehand.

Data analysis

Three of the initial participants were lost to follow-up resulting in eleven interviews, conducted from April 2022 to August 2022, which were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Interviews ranged from 46 to 108 min, with an average length of 52 min. Interview transcripts were analyzed iteratively using content and thematic analysis [ 27 ] to generate a collective patient journey map. We used an inductive 3-phase approach including: preparation (reading data thoroughly, immersion), organizing (open coding, developing a coding scheme, grouping the data), and reporting (generating themes reflected in the patient journey map and a conceptual understanding of the phenomenon) [ 27 ]. Members of the study team (MS, SN) with qualitative research and clinical experience worked together to develop a coding scheme by identifying broad open codes, such as “touch point,” “pain point,” “facilitator,” and “feelings.” The agreed upon coding scheme was used to analyze transcripts and develop a codebook with the broad codes and associated narratives. From this document, we developed the collective patient journey map. Further data grouping occurred, enabling us to identify overarching categories and themes from the clients’ and caregivers’ perspectives.

Strategies to increase the quality of our research process are collectively known as an assessment of trustworthiness and are encapsulated by the following three domains [ 28 , 29 ]. (1) Credibility techniques that were applied involved prolonged engagement with participants across two interviews, assessment of the researcher's own influence on the research process known as reflexivity, and member checking by sharing interpretations during follow-up interviews. (2) Dependability was enhanced by following an analytical plan and having multiple coders. (3) Credibility is grounded in a team of expert researchers in qualitative methods, home care delivery, and patient engagement, who frequently met to discuss the data and emerging insights.

A total of seven participants (five home care clients and two caregivers of individuals receiving home care) completed seven initial interviews, and four completed a follow-up interview for a total of 11 interviews (Table 1 ). Most participants identified as female (n = 5) and were on average 66 years of age (range 44 to 88 years). Caregivers (n = 2) identified as a spouse and a paid private caregiver, with neither providing respite care.

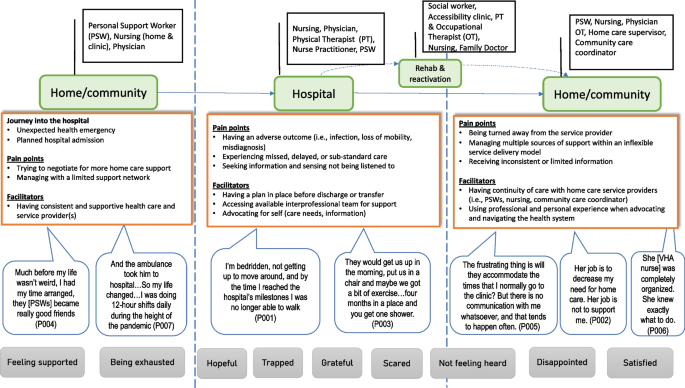

Participants were engaged in the production of a collective journey map (Fig. 1 ). The following four categories and themes emerged as key experiences in participants’ journey transitioning from hospital-to-home: (1) Touchpoints; Life is changing ; (2) Pain points: Sensing nobody is listening and trying to find a good fit ; (3) Facilitators: Developing relationships gaining some continuity, and trying to advocate, and (4) Emotional impact: Having only so much emotional capacity .

Illustration depicting the collective journey map

Touchpoints as interactions with the health system – Life is changing

Participants described service touchpoints experienced by home care clients as they transitioned from hospital to home. Participant narratives highlight the complexity of the care transitions, including the variety of providers and multiple sectors involved. Participant 6 described:

“ A podiatrist told me the condition of my right foot did not look good and that I should probably go in to emerge and have them do an assessment. I did do that, and I wound up being admitted to the hospital, and within a couple of days, they did a partial amputation on my right foot. Then I was admitted to rehab for a two-week stay .” (P006)

Experiences of health system touchpoints were also described by participant 004 as:

“ After 2 months of Rehab I realized if I had to do long-term care, I could but I didn’t want to, it was that simple if I could get support at home then I would, so the discharge planner started to work on how to get him support and how many times a day we would need it and that’s how we ended up with multiple agencies because we need 4 times a day .” (P004)

While most participants described the hospitalizations as unplanned, acute situations, two individuals had planned surgeries. Regardless of the context for admission, many participants often noted that exacerbations of chronic conditions or an acute episode of illness had a life-altering impact on them or the person they cared for. For this reason, participants left the hospital setting with greater intensity in care needs than before admission. For example, one participant described the significant physical decline in coping with a hospital-acquired infection, while another explicitly noted how life had changed for her and her husband after hospital admission in an increase in touchpoints, mainly because of the pandemic,

“ We have three agencies so our life is really coo-coo compared to then when it was all just one agency and one coordinator and if you needed something special you knew exactly who to call like if you had a dental appointment you knew who to call for extra support on this day, can move this hour to here it was fine, things were more flexible.” (P004)

Pain points as barriers in the health system

Pain points were described as critical moments that hindered quality care transitions from the participants' perspective. Two themes emerged as Sensing nobody is listening and Trying to find a good fit and were discussed as communication and care coordination challenges.

Sensing nobody is listening

Several participants observed that their opinions about their treatment plan went unnoticed by the health care providers. In some cases, not being heard contributed to patient harm, including adverse outcomes and missed or delayed care. The harmful events included losing mobility and continence due to bed restrictions post-surgery, hospital-acquired infection, and a procedure-related incident. Participant 001 described feeling unheard as:

“ It was supposed to be an overnight stay, and then go home, stay overnight, one or two nights, I’ll be fine and ready to go home. It didn't turn out that way because the hospital insisted on reaching a few milestones that my body wasn't ready for, like being able to go to the toilet on my own, instead of relying on a catheter, and that takes a few days, so I’m bedridden, not getting up to move around and not getting any exercise, and by the time I reached the hospital's milestones I was no longer able to walk .” (P001) “After a week he was in the hospital, maybe 10 days after, the doctor said, ‘I want to take out the stitches now.’ And I said, ‘I know [name], and I feel that maybe we could just wait a little bit.’ ‘So no. I'm taking them out. And I'm the doctor. You're not.’ So he took the stitches out and left the room, and then there were loops of small bowel coming out of the hole…So they had to rush him up to the emergency and do another operation. So that delayed everything.” (P007)

Many participants described instances of emotional harm in the case of not receiving clear communication from health care providers and feeling frustrated and unsupported. One participant reported this experience as receiving “different stories” (P002) depending on whom you spoke to, while another individual said fragmented communication between a hospital clinic and a community provider about her leg dressing left her “removed from the situation” noted in the following quote:

“ It's probably almost like being back in high school. That's sometimes how I feel, to be honest, a couple of times I've left there in tears because it's just like nobody is listening to me. Nobody is listening to what I need. And I'm going home, and it's [leg wound] leaking all over my floor and it's frustrating not to have that communication piece. It's just like I'm there, and it doesn't matter what my experience is .” (P005)

Trying to find a good fit

Most participants noted the absence of continuity of care among home care providers as a pain point when they transitioned home from the hospital. This transpired for home care clients who required more home care hours upon discharge, which could no longer be accommodated by one service provider alone. Service coverage by multiple home care agencies had participants trying to find “a good fit” (P002) as they had to coordinate not only fluctuating schedules but different home care workers and communication practices:

“ There's a definite ‘Oh, my God, here we go again, training new people.’ And we've had it throughout the year, something's happened to somebody and they've gone. And then we start with somebody new. We have not been able to get consistent care in the evening since he left. This morning, I just got a call that one of the other—that’s now the fifth agency, believe it or not, is saying they could try and pick it up in the evening and for me to call them and see what we can work out .” (P004)

The changing service providers impacted the clients and caregivers, who often noted that they had to “train” the incoming staff about their or the person they care for personal needs. A new home care provider for some is like “starting from scratch” (P002), which has become more problematic because of COVID-19 and workforce shortages in health care:

“ The agency that was doing my PSW [personal support worker] care could not, at that time, provide me with the service, so I had to start with a new home care agency so the PSWs switched. Again, starting with new people and a new agency and retraining and trying to find a good fit. The biggest barriers have been with the agency and starting from scratch .” (P002)

For one participant, to maintain a consistent PSW and comfort with care, the client chose to remain in her bed for 20 h to accommodate this worker’s schedule and explained her rationale for this decision in the following quote:

“ I stay in bed from 5:00 at night to 1:00 in the afternoon every Thursday, so that kind of sucks, but nobody can do anything about it. I have a PSW coming at different hours every day and if I want the same PSW she is not available until 1 in the afternoon. It's better for me to have the same PSW because it gets exhausting to remind them to do everything .” (P001)

Facilitators to positive care transitions

Facilitators are positive system and client-level factors that helped to support the transition and the adjustment to being home. This theme comprises two sub-themes that consider the importance of relationships and advocacy for quality care transitions.

Developing relationships and gaining some continuity

Many participants described existing relationships with home care providers as tight-knit bonds that strengthened over time. As such, these relationships were central to their care transition journey because the home care providers knew them well, including their baseline functioning, family, and household, and were often a driving force behind changes to the service plan. These longer-term relationships also enabled providers to flag medical inconsistencies among clients. For example, continuity of care in home care nursing resulted in an escalation in care because of a client’s deteriorating symptoms according to one participant,

“ She sent me back to the hospital when I was in A-fib (heart arrhythmia) because she knew what my normal was and she knew that this was not normal .” (P002)

The continuity of care in service providers has also acted as a safety net for other participants who rely on one or more key people to help coordinate and deliver care in the community. One participant described an extensive network of providers: the community care coordinator, a home care supervisor, an interdisciplinary primary care program, and a personal support worker. Collectively, this team has enabled her and her husband to stay at home safely as they age.

“ I have to say that the home care supervisor has been so caring, and she's done everything that you can to get the time that we've been allotted by the care coordinator, and all it did was just reconfirmed to us that we were not going to go into an institution and that we are staying home .” (P003)

Trying to advocate

All the participants reported being an advocate for themselves or the person they care for as a facilitator for a better transition experience. Advocating appeared to express their needs and requests firmly, and when supporting the participants drew from their professional skills or previous care transitions. For example, one participant managed to secure a transfer to an inpatient rehabilitation facility for additional physical therapy. Once she realized that her prior home care agency could not support her service plan, she called the home care supervisor at that agency directly.

“ I think I kind of felt that the squeaky wheel gets the worm, so to be turned away from the home care agency after having been with them for 5 years, it just floored me and scared me. To be told ‘no’ I think that was the social worker that told me, so I had to say to her ‘Hello, can you re-visit that and see if I can get back in? Rather than relying on the social worker, I phoned directly to the home care agency and spoke to my coordinator who used to schedule me. ” (P001)

Advocating for respite care through home care by one caregiver participant did not result in a service change and instead created frustration and tension for this individual. According to this participant, despite phone calls, letter writing, and an in-person meeting with the community care coordinator, their needs went unheard, and an escalation in the advocacy process seemed to be justified in this case noted in the following example,

“ So I feel I walk with integrity, and I feel she [community care coordinator] needs a wake-up call. And I will facilitate that. And it may be 20 pages, but I don't care. I've got nothing to lose. I don't care right now in my life. I will just push and push and push and push, and I'll say, ‘Well, then, I'll go to your ombudsman then. Because if you're not going to cooperate with the care plan and support me with [name’s] care, I want to make sure that everyone in the industry knows it. " (P007)

Emotional impact

The final category of feelings is framed by the theme, Having only so much emotional capacity to illustrate the emotional impact of these care transitions on clients and caregivers.

Having only so much emotional capacity

The participants described a mixture of primarily negative feelings when faced with unexpected challenges related to hospitalization and transition back to the community. When hospitalized, several participants felt “trapped” (P001) and “scared,” and “helpless” (P003) because of their lack of control over their situation. Once discharged from the hospital, certain feelings persisted. For example, one person expressed feeling worried about the availability of care to meet a future need based on prior experiences when,

“ My coordinator is coming out next week and because every 90 days I’m supposed to be assessed and that’s the opportunity to get support, but really her job is to decrease my need for home care…I worry because I'm due for another hospitalization to have that surgery. And I know that I'm going to come home needing more service, and I'm worried I'm not going to get it .” (P002)

In another example, the participant called out feeling “diminished” and “worthless” when their request for an extra hour of personal support for respite went unheeded by the community care coordinator. In turn, this individual felt “taken for granted” rather than validated after many years of providing private caregiving service to a mother-son dyad,

“ So when you've been told three times in a row, ‘You're not going to get that extra hour,’ for me, it diminishes all my 27 years of work. ‘Well, I'm worthless.’ I have to go through those emotions .” (P007)

When participants expressed positive emotions of feeling “respected” and “appreciated,” they described the enabling factors as sensing that the providers were invested in their care and wellbeing, having their questions answered and listened to, and being engaged in critical discussions by the providers. These positive excerpts indicated that these participants perceived quality care being delivered and the presence of an adequate level of support to meet their complex care needs.

“ She [physiatrist] doesn't miss a thing. She is very attentive. Will explain things in detail. When she admitted me to Rehab for the two-week stay, my wife nicknamed her St. Name…Because my wife was at her wit’s end trying to figure out what to do. And, uh the doctor basically took that out of her hands and took over .” (P006)

This study provides an overarching illustration of the patient journey of home care recipients from hospitalization to the return to the community and resumed home care service. The findings offer insights into the touchpoints, pain points, facilitators, and feelings experienced and perceived by these clients regarding their journey. We derived categories and themes from our data that highlighted issues with communication and continuity of care. All participants identified factors that mitigated negative transition experiences, such as relying on long-standing relationships and advocating for themselves. The findings contribute to the focus on the care transition needs of home care clients and the optimization of a more integrated health system.

In many countries worldwide, patients receiving home care services typically live with comorbid conditions, with high functional and cognitive impairment rates [ 30 , 31 , 32 ]. Sinn and colleagues observed that in Ontario, Canada, 7.3% of patients died, 16.6% were hospitalized, and 44.4% visited the emergency department within 90 days of being admitted to home care [ 30 ]. Unsurprisingly, most of the participants in our study had hospitalizations that resulted in significant functional decline and hospital-acquired infection. In this context, individuals leave the hospital with higher medical complexities, and they or their family members receiving home care require additional support to remain in their own homes. Our finding supports previous studies that describe the post-discharge period as a vulnerable time for these patients [ 33 , 34 ]. More specifically, adaptation to life after the hospital is experienced as challenging when health problems compound daily activities such as laundry, meal preparation, and meeting basic needs like toileting [ 33 ].

During their transition journey, participants reported not feeling listened to and having limited information about their treatment and discharge plan while navigating between hospital-to-home. In a few cases, patients experienced harm that could have been prevented including loss of mobility, hospital-acquired infection, functional decline, and emotional damage. Further, adverse health outcomes contributed to delayed discharge from the hospital, resulting in additional usage of health care resources upon return home.

Hospital-based patient harm remains an ongoing issue. In Canada in 2021/22, 5.8% of patients experienced hospital harm during acute hospital admission [ 35 ]. Internationally, the pooled rate of hospital harm is 6% of patients across medical settings [ 36 ]. These findings are consistent with other research on communication failures between patients and health care providers [ 37 ] and the experience and impacts of hospital-based patient harm [ 38 ]. Similar to our findings, patient-provider miscommunication is often identified as a quality and safety concern by patients even without an adverse event [ 37 ]. Participants’ experiences of feeling unheard is detrimental, regardless if negative health outcomes or physical harm is caused.

Participants experienced challenges with the continuity of home care service providers, namely PSWs, once discharged home. The challenge stemmed from workforce constraints that resulted in either the home care organization being unable to resume service or the client needing assistance from multiple agencies to meet higher care demands. As a result of COVID-19, home care agencies faced extreme challenges in providing high-quality, in-home client care, including the adoption of virtual care use. The home care sector also experienced personal protective equipment shortages and staffing constraints caused by COVID-19 infection [ 39 , 40 ]. These issues are compounded by unprecedented home and community care staffing shortages observed in a tripling of staff vacancies—a 331% increase in PSW openings from 2020 to 2021 [ 41 ]. Our findings show that home care clients not only value and desire consistency in home care service providers, but they also make sacrifices to achieve consistency in care. Despite critical issues of delivering continuity of care, there is limited literature exploring challenges of scheduling consistency for PSWs in home care delivery and pressures this causes for delivering high-quality care [ 10 , 42 ]. Other research has detailed the importance of consistent PSWs in building trusting relationships with clients and families and delivering tailored care to match client needs and preferences [ 10 , 43 ]. In our study, patients receiving homecare and their family caregivers described relational continuity with home care providers as an enabler of quality transitions. Participants also discussed continuity of care from home and community care workers prevented harm and contributed to a safety net in the community. The linkage between quality home care and continuity of care in the literature [ 44 ], and broadly speaking, relational continuity in health care has led to more effective and efficient diagnosis and management of health problems and a means of building patient trust [ 45 ]. In our study we found that when established home care services were disrupted by planned or unplanned hospitalizations and homecare was resumed, the disruption in relational continuity was destabilizing for clients and caregivers and may contribute to potential safety issues.