- Daily Pinoy News

- Submit an Article

The Pinoy Site

Philippine Infos and More

- Buhay Student

- Forwarded Messages

- Motivational

- Pantasya Balita

- Pilipinas Info

- Problemang Pinas

- Visiting the PH

Republic Act No. 11479: The Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020 [Full Text]

Ang Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020 ay inaprubahan bilang isang ganap na batas nuong July 3, 2020 sa layuning supilin ang terorismo sa Pilipinas.

Ang mga Panukalang Batas na pinagmulan nito ay ang House Bill No. 6875 at Senate Bill No. 1083.

Ilang mga petisyon laban sa Batas na ito ang mga isinampa na sa Korte Suprema ng iba’t-ibang grupo.

Narito ang kumpletong nilalaman ng Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020.

References:

- Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020 (Wikipedia)

- Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020 (Official Gazette)

- Philippines: Anti-terror act faces top court challenges

************************************************************************************ ************************************************************************************

S. No. 1083 H. No. 6875

Republic of the Philippines Congress of the Philippines Metro Manila Eighteenth Congress First Regular Session

Begun and held in Metro Manila, on Monday, the twenty-second day of July, two thousand nineteen.

[Republic Act No. 11479]

AN ACT TO PREVENT, PROHIBIT AND PENALIZE TERRORISM, THEREBY REPEALING REPUBLIC ACT NO. 9372, OTHERWISE KNOWN AS THE “HUMAN SECURITY ACT OF 2007”

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the Philippines in Congress assembled:

SECTION 1. Short Title. – This Act shall henceforth be known as “The Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020”.

SEC. 2. Declaration of Policy. – It is declared a policy of the State to protect life, liberty, and property from terrorism, to condemn terrorism as inimical and dangerous to the national security of the country and to the welfare of the people, and to make terrorism a crime against the Filipino people, against humanity, and against The Law of Nations.

In the implementation of the policy stated above, the State shall uphold the basic rights and fundamental liberties of the people as enshrined in the Constitution.

The State recognizes that the fight against terrorism requires a comprehensive approach, comprising political, economic, diplomatic, military, and legal means duly taking into account the root causes of terrorism without acknowledging these as justifications for terrorist and/or criminal activities. Such measures shall include conflict management and post-conflict peace building, addressing the roots of conflict by building state capacity and promoting equitable economic development.

Nothing in this Act shall be interpreted as a curtailment, restriction or diminution of constitutionally recognized powers of the executive branch of the government. It is to be understood, however, that the exercise of the constitutionally recognized powers of the executive department of the government shall not prejudice respect for human rights which shall be absolute and protected at all times.

SEC. 3. Definition of Terms. – as used in this Act:

(a) Critical Infrastructure shall refer to an asset or system, whether physical or virtual, so essential to the maintenance of vital societal functions or to the delivery of essential public services that the incapacity or destruction of such systems and assets would have a debilitating impact on national defense and security, national economy, public health or safety, the administration of justice, and other functions analogous thereto. It may include, but is not limited to, an asset or system affecting telecommunications, water and energy supply, emergency services, food security, fuel supply, banking and finance, transportation, radio and television. information systems and technology, chemical and nuclear sectors;

(b) Designated Person shall refer to:

Any individual, group of persons, organizations, or associations designated and/or identified by the United Nations Security Council, or another jurisdiction, or supranational jurisdiction as a terrorist, one who finances terrorism, or a terrorist organization or group; or

Any person, organization, association, or group of persons designated under paragraph 3 of Section 25 of this Act.

For purposes of this Act, the above definition shall be in addition to the definition of designated persons under Section 3(e) of Republic Act No. 10168, otherwise known as the “Terrorism Financing Prevention and Suppression Act of 2012”.

(c) Extraordinary Rendition shall refer to the transfer of a person, suspected of being a terrorist or supporter of a terrorist organization, association, or group of persons to a foreign nation for imprisonment and interrogation on behalf of the transferring nation. The extraordinary rendition may be done without framing any formal charges, trial, or approval of the court.

(d) International Organization shall refer to an organization established by a treaty or other instrument governed by international law and possessing its own international legal personality;

(e) Material Support shall refer to any property, tangible or intangible, or service, including currency or monetary instruments or financial securities, financial services, lodging, training, expert advice or assistance, safehouses, false documentation or identification, communications equipment, facilities. weapons, lethal substances, explosives, personnel (one or more individuals who may be or include oneself), and transportation;

(f) Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction shall refer to the transfer and export of chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear weapons, their means of delivery and related materials;

(g) Proposal to Commit Terrorism is committed when a person who has decided to commit any of the crimes defined and penalized under the provisions of this Act proposes its execution to some other person or persons;

(h) Recruit shall refer to any act to encourage other people to join a terrorist individual or organization, association or group of persons proscribed under Section 26 of this Act, or designated by the United Nations Security Council as a terrorist organization, or organized for the purpose of engaging in terrorism;

(i) Surveillance Activities shall refer to the act of tracking down, following, or investigating individuals or organizations; or the tapping, listening, intercepting, and recording of messages. conversations, discussions, spoken or written words, including computer and network surveillance, and other communications of individuals engaged in terrorism as defined hereunder;

(j) Supranational Jurisdiction shall refer to an international organization or union in which the power and influence of member states transcend national boundaries or interests to share in decision-making and vote on issues concerning the collective body, i.e. the European Union;

(k) Training shall refer to the giving of instruction or teaching designed to impart a specific skill in relation to terrorism as defined hereunder, as opposed to general knowledge;

(l) Terrorist Individual shall refer to any natural person who commits any of the acts defined and penalized under Sections 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10,11 and 12 of this Act;

(m) Terrorist Organization, Association or Group of Persons shall refer to any entity organized for the purpose of engaging in terrorism, or those proscribed under Section 26 hereof or the United Nations Security Council-designated terrorist organization; and

(n) Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) shall refer to chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear weapons which are capable of a high order of destruction or causing mass casualties. It excludes the means of transporting or propelling the weapon where such means is a separable and divisible part from the weapon.

SEC. 4. Terrorism. – Subject to Section 49 of this Act, terrorism is committed by any person who, within or outside the Philippines, regardless of the stage of execution:

(a) Engages in acts intended to cause death or serious bodily injury to any person, or endangers a person’s life;

(b) Engages in acts intended to cause extensive damage or destruction to a government or public facility, public place or private property;

(c) Engages in acts intended to cause extensive interference with, damage or destruction to critical infrastructure;

(d) Develops, manufactures, possesses, acquires, transports, supplies or uses weapons, explosives or of biological, nuclear, radiological or chemical weapons; and

(e) Release of dangerous substances, or causing fire, floods or explosions when the purpose of such act, by its nature and context, is to intimidate the general public or a segment thereof, create an atmosphere or spread a message of fear, to provoke or influence by intimidation the government or any international organization, or seriously destabilize or destroy the fundamental political, economic, or social structures of the country, or create a public emergency or seriously undermine public safety, shall be guilty of committing terrorism and shall suffer the penalty of life imprisonment without the benefit of parole and the benefits of Republic Act No. 10592, otherwise known as “An Act Amending Articles 29, 94, 97, 98 and 99 of Act No. 3815, as amended, otherwise known as the Revised Penal Code”: Provided, That, terrorism as defined in this section shall not include advocacy, protest, dissent, stoppage of work, industrial or mass action, and other similar exercises of civil and political rights, which are not intended to cause death or serious physical harm to a person, to endanger a person’s life, or to create a serious risk to public safety.

SEC. 5. Threat to Commit Terrorism. – Any person who shall threaten to commit any of the acts mentioned in Section 4 hereof shall suffer the penalty of imprisonment of twelve (12) years.

SEC. 6. Planning, Training, Preparing, and Facilitating the Commission of Terrorism. – It shall be unlawful for any person to participate in the planning, training, preparation and facilitation in the commission of terrorism, possessing objects connected with the preparation for the commission of terrorism, or collecting or making documents connected with the preparation of terrorism. Any person found guilty of the provisions of this Act shall suffer the penalty of life imprisonment without the benefit of parole and the benefits of Republic Act No. 10592.

SEC. 7. Conspiracy to Commit Terrorism. – Any conspiracy to commit terrorism as defined and penalized under Section 4 of this Act shall suffer the penalty of life imprisonment without the benefit of parole and the benefits of Republic Act No. 10592.

There is conspiracy when two (2) or more persons come to an agreement concerning the commission of terrorism as defined in Section 4 hereof and decide to commit the same.

SEC. 8. Proposal to Commit Terrorism. – Any person who proposes to commit terrorism as defined in Section 4 hereof shall suffer the penalty of imprisonment of twelve (12) years.

SEC. 9. Inciting to Commit Terrorism. – Any person who, without taking any direct part in the commission of terrorism, shall incite others to the execution of any of the acts specified in Section 4 hereof by means of speeches, proclamations, writings, emblems, banners or other representations tending to the same end, shall suffer the penalty of imprisonment of twelve (12) years.

SEC. 10. Recruitment to and Membership in a Terrorist Organization. – Any person who shall recruit another to participate in, join, commit or support terrorism or a terrorist individual or any terrorist organization, association or group of persons proscribed under Section 26 of this Act, or designated by the United Nations Security Council as a terrorist organization, or organized for the purpose of engaging in terrorism, shall suffer the penalty of life imprisonment without the benefit of parole and the benefits of Republic Act No. 10592.

The same penalty shall be imposed on any person who organizes or facilitates the travel of individuals to a state other than their state of residence or nationality for the purpose of recruitment which may be committed through any of the following means:

(a) Recruiting another person to serve in any capacity in or with an armed force in a foreign state, whether the armed force forms part of the armed forces of the government of that foreign state or otherwise;

(b) Publishing an advertisement or propaganda for the purpose of recruiting persons to serve in any capacity in or with such an armed force;

(c) Publishing an advertisement or propaganda containing any information relating to the place at which or the manner in which persons may make applications to serve or obtain information relating to service in any capacity in or with such armed force or relating to the manner in which persons may travel to a foreign state for the purpose of serving in any capacity m or with such armed force; or

(d) Performing any other act with the intention of facilitating or promoting the recruitment of persons to serve in any capacity in or with such armed force.

Any person who shall voluntarily and knowingly join any organization, association or group of persons knowing that such organization, association or group of persons is proscribed under Section 26 of this Act, or designated by the United Nations Security Council as a terrorist organization, or organized for the purpose of engaging in terrorism, shall suffer the penalty of imprisonment of twelve (12) years.

SEC. 11. Foreign Terrorist. – The following acts are unlawful and shall suffer the penalty of life imprisonment without the benefit of parole and the benefits of Republic Act No. 10592:

(a) For any person to travel or attempt to travel to a state other than his/her state of residence or nationality, for the pw-pose of perpetrating, planning, or preparing for, or participating in terrorism, or providing or receiving terrorist training;

(b) For any person to organize or facilitate the travel of individuals who travel to a state other than their states of residence or nationality knowing that such travel is for the purpose of perpetrating, planning, training, or preparing for, or participating in terrorism or providing or receiving terrorist training; or

(c) For any person residing abroad who comes to the Philippines to participate in perpetrating, planning, training, or preparing for, or participating in terrorism or provide support for or facilitate or receive terrorist training here or abroad.

SEC. 12. Providing Material Support to Terrorists. – Any person who provides material support to any terrorist individual or terrorist organization, association or group of persons committing any of the acts punishable under Section 4 hereof, knowing that such individual or organization, association, or group of persons is committing or planning to commit such acts, shall be liable as principal to any and all terrorist activities committed by said individuals or organizations, in addition to other criminal liabilities he/she or they may have incurred in relation thereto.

SEC. 13. Humanitarian Exemption. – Humanitarian activities undertaken by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), the Philippine Red Cross (PRC), and other state-recognized impartial humanitarian partners or organizations in conformity with the International Humanitarian Law (IHL), do not fall within the scope of Section 12 of this Act.

SEC. 14. Accessory. – Any person who, having knowledge of the commission of any of the crimes defined and penalized under Section 4 of this Act, without having participated therein, takes part subsequent to its commission in any of the following manner: (a) by profiting himself/herself or assisting the offender to profit by the effects of the crime; (b) by concealing or destroying the body of the crime, or the effects, or instruments thereof, in order to prevent its discovery; or (c) by harboring, concealing, or assisting in the escape of the principal or conspirator of the crime, shall be liable as an accessory and shall suffer the penalty of imprisonment of twelve (12) years.

No person, regardless of relationship or affinity, shall be exempt from liability under this section.

SEC. 15. Penalty for Public Official. – If the offender found guilty of any of the acts defined and penalized under any of the provisions of this Act is a public official or employee, he/she shall be charged with the administrative offense of grave misconduct and/or disloyalty to the Republic of the Philippines and the Filipino people, and be meted with the penalty of dismissal from the service, with the accessory penalties of cancellation of civil service eligibility, forfeiture of retirement benefits and perpetual absolute disqualification from running for any elective office or holding any public office.

SEC. 16. Surveillance of Suspects and Interception and Recording of Communications. – The provisions of Republic Act No. 4200. otherwise known as the “Anti-Wire Tapping Law” to the contrary notwithstanding, a law enforcement agent or military personnel may, upon a written order of the Court of Appeals secretly wiretap, overhear and listen to, intercept, screen, read, surveil, record or collect, with the use of any mode, form, kind or type of electronic, mechanical or other equipment or device or technology now known or may hereafter be known to science or with the use of any other suitable ways and means for the above purposes, any private communications, conversation, discussion/s, data, information, messages in whatever form, kind or nature, spoken or written words (a) between members of a judicially declared and outlawed terrorist organization, as provided in Section 26 of this Act; (b) between members of a designated person as defined in Section 3(e) of Republic Act No. 10168; or (c) any person charged with or suspected of committing any of the crimes defined and penalized under the provisions of this Act: Provided, That, surveillance, interception and recording of communications between lawyers and clients, doctors and patients, journalists and their sources and confidential business correspondence shall not be authorized.

The law enforcement agent or military personnel shall likewise be obligated to (1) file an ex-parte application with the Court of Appeals for the issuance of an order, to compel telecommunications service providers (TSP) and internet service providers (ISP) to produce all customer information and identification records as well as call and text data records, content and other cellular or internet metadata of any person suspected of any of the crimes defined and penalized under the provisions of this Act; and (2) furnish the National Telecommunications Commission (NTC) a copy of said application. The NTC shall likewise be notified upon the issuance of the order for the purpose of ensuring immediate compliance.

SEC. 17. Judicial Authorization, Requisites. – The authorizing division of the Court of Appeals shall issue a written order to conduct the acts mentioned in Section 16 of this Act upon:

(a) Filing of an ex parte written application by law enforcement agent or military personnel, who has been duly authorized in writing by the Anti-Terrorism Council (ATC); and

(b) After examination under oath or affirmation of the applicant and the witnesses he/she may produce, the issuing court determines:

(1) that there is probable cause to believe based on personal knowledge of facts or circumstances that the crimes defined and penalized under Sections 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 of this Act has been committed, or is being committed, or is about to be committed; and

(2) that there is probable cause to believe based on personal knowledge of facts or circumstances that evidence, which is essential to the conviction of any charged or suspected person for, or to the solution or prevention of, any such crimes, will be obtained.

SEC. 18. Classification and Contents of the Order of the Court. – The written order granted by the authorizing division of the Court of Appeals as well as the application for such order, shall be deemed and are hereby declared as classified information. Being classified information, access to the said documents and any information contained in the said documents shall be limited to the applicants, duly authorized personnel of the ATC, the hearing justices, the clerk of court and duly authorized personnel of the hearing or issuing court. The written order of the authorizing division of the Court of Appeals shall specify the following: (a) the identity, such as name and address, if known, of the person or persons whose communications, messages, conversations, discussions, or spoken or written words are to be tracked down, tapped, listened to, intercepted, and recorded; and, in the case of radio, electronic, or telephonic (whether wireless or otherwise) communications, messages, conversations, discussions, or spoken or written words, the electronic transmission systems or the telephone numbers to be tracked down, tapped, listened to, intercepted, and recorded and their locations or if the person or persons suspected of committing any of the crimes defined and penalized under the provisions of this Act are not fully known, such person or persons shall be the subject of continuous surveillance; (b) the identity of the law enforcement agent or military personnel, including the individual identity of the members of his team, judicially authorized to undertake surveillance activities; (c) the offense or offenses committed, or being committed, or sought to be prevented; and, (d) the length of time within which the authorization shall be used or carried out.

SEC. 19. Effective Period of Judicial Authorization. – Any authorization granted by the Court of Appeals, pursuant to Section 17 of this Act, shall only be effective for the length of time specified in the written order of the authorizing division of the Court of Appeals which shall not exceed a period of sixty (60) days from the date of receipt of the written order by the applicant law enforcement agent or military personnel.

The authorizing division of the Court of Appeals may extend or renew the said authorization to a non-extendible period, which shall not exceed thirty (30) days from the expiration of the original period: Provided, That the issuing court is satisfied that such extension or renewal is in the public interest: and Provided, further, That the ex parte application for extension or renewal, which must be filed by the original applicant, has been duly authorized in writing by the ATC.

In case of death of the original applicant or in case he/she is physically disabled to file the application for extension or renewal, the one next in rank to the original applicant among the members of the team named in the original written order shall file the application for extension or renewal: Provided, finally, That, the applicant law enforcement agent or military personnel shall have thirty (30) days after the termination of the period granted by the Court of Appeals as provided in the preceding paragraphs within which to file the appropriate case before the Public Prosecutor’s Office for any violation of this Act.

For purposes of this provision, the issuing court shall require the applicant law enforcement or military official to inform the court, after the lapse of the thirty (30)-day period of the fact that an appropriate case for violation of this Act has been filed with the Public Prosecutor’s Office.

SEC. 20. Custody of Intercepted and Recorded Communications. – All tapes, discs, other storage devices, recordings, notes, memoranda, summaries, excerpts and all copies thereof obtained under the judicial authorization granted by the Court of Appeals shall, within forty-eight (48) hours after the expiration of the period fixed in the written order or the extension or renewal granted thereafter, be deposited with the issuing court in a sealed envelope or sealed package, as the case may be, and shall be accompanied by a joint affidavit of the applicant law enforcement agent or military personnel and the members of his/her team.

In case of death of the applicant or in case he/she is physically disabled to execute the required affidavit, the one next in rank to the applicant among the members of the team named in the written order of the authorizing division of the Court of Appeals shall execute with the members of the team that required affidavit.

It shall be unlawful for any person, law enforcement agent or military personnel or any custodian of the tapes, discs, other storage devices recordings, notes, memoranda, summaries, excerpts and all copies thereof to remove, delete, expunge, incinerate, shred or destroy in any manner the items enumerated above in whole or in part under any pretext whatsoever.

Any person who removes, deletes, expunges, incinerates, shreds or destroys the items enumerated above shall suffer the penalty of imprisonment of ten (10) years.

SEC. 21. Contents of Joint Affidavit. – The joint affidavit of the law enforcement agent or military personnel shall state: (a) the number of tapes, discs, and recordings that have been made; (b) the dates and times covered by each of such tapes, discs, and recordings; and (c) the chain of custody or the list of persons who had possession or custody over the tapes, discs and recordings.

The joint affidavit shall also certify under oath that no duplicates or copies of the whole or any part of any of such tapes, discs, other storage devices, recordings, notes, memoranda, summaries, or excerpts have been made, or, if made, that all such duplicates and copies are included in the sealed envelope or sealed package, as the case may be, deposited with the authorizing division of the Court of Appeals.

It shall be unlawful for any person, law enforcement agent or military personnel to omit or exclude from the joint affidavit any item or portion thereof mentioned in this section.

Any person, law enforcement agent or military officer who violates any of the acts proscribed in the preceding paragraph shall suffer the penalty of imprisonment of ten (10) years.

SEC. 22. Disposition of Deposited Materials. – The sealed envelope or sealed package and the contents thereof, referred to in Section 20 of this Act, shall be deemed and are hereby declared classified information. The sealed envelope or sealed package shall not be opened, disclosed, or used as evidence unless authorized by a written order of the authorizing division of the Court of Appeals which written order shall be granted only upon a written application of the Department of Justice (DOJ) duly authorized in writing by the ATC to file the application with proper written notice to the person whose conversation, communication, message, discussion or spoken or written words have been the subject of surveillance, monitoring, recording and interception to open, reveal, divulge, and use the contents of the sealed envelope or sealed package as evidence.

The written application, with notice to the party concerned, for the opening, replaying, disclosing, or using as evidence of the sealed package or the contents thereof, shall clearly state the purpose or reason for its opening, replaying, disclosing, or its being used as evidence.

Violation of this section shall be penalized by imprisonment of ten (10) years.

SEC. 23. Evidentiary Value of Deposited Materials. – Any listened to, intercepted, and recorded communications, messages, conversations, discussions, or spoken or written words, or any part or parts thereof, or any information or fact contained therein, including their existence, content, substance, purport, effect, or meaning, which have been secured in violation of the pertinent provisions of this Act, shall be inadmissible and cannot be used as evidence against anybody in any judicial, quasi-judicial, legislative, or administrative investigation, inquiry, proceeding, or hearing.

SEC. 24. Unauthorized or Malicious Interceptions and/ or Recordings. – Any law enforcement agent or military personnel who conducts surveillance activities without a valid judicial authorization pursuant to Section 17 of this Act shall be guilty of this offense and shall suffer the penalty of imprisonment of ten (10) years. All information that have been maliciously procured should be made available to the aggrieved party.

SEC. 25. Designation of Terrorist Individual, Groups of Persons, Organizations or Associations. – Pursuant to our obligations under United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) No. 1373, the ATC shall automatically adopt the United Nations Security Council Consolidated List of designated individuals, group of persons, organizations, or associations designated and/or identified as a terrorist, one who finances terrorism, or a terrorist organization or group.

Request for designations by other jurisdictions or supranational jurisdictions may be adopted by the ATC after determination that the proposed designee meets the criteria for designation of UNSCR No.1373. ·

The ATC may designate an individual, groups of persons, organization, or association, whether domestic or foreign, upon a finding of probable cause that the individual, groups of persons, organization, or association commit, or attempt to commit, or conspire in the commission of the acts defined and penalized under Sections 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 of this Act.

The assets of the designated individual, groups of persons, organization or association above-mentioned shall be subject to the authority of the Anti-Money Laundering Council (AMLC) to freeze pursuant to Section II of Republic Act No. 10168.

The designation shall be without prejudice to the proscription of terrorist organizations, associations, or groups of persons under Section 26 of this Act.

SEC. 26. Proscription of Terrorist Organizations, Association, or Group of Persons. – Any group of persons, organization or association, which commits any of the acts defined and penalized under Sections 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 of this Act, or organized for the purpose of engaging in terrorism shall, upon application of the DOJ before the authorizing division of the Court of Appeals with due notice and opportunity to be heard given to the group of persons, organization or association, be declared as a terrorist and outlawed group of persons, organization or association, by the said Court.

The application shall be filed with an urgent prayer for the issuance of a preliminary order of proscription. No application for proscription shall be filed without the authority of the ATC upon the recommendation of the National Intelligence Coordinating Agency (NICA).

SEC. 27. Preliminary Order of Proscription. – Where the Court has determined that probable cause exists on the basis of the verified application which is sufficient in form and substance, that the issuance of an order of proscription is necessary to prevent the commission of terrorism, he/she shall, within seventy-two (72) hours from the filing of the application, issue a preliminary order of proscription declaring that the respondent is a terrorist and an outlawed organization or association within the meaning of Section 26 of this Act.

The court shall immediately commence and conduct continuous hearings, which should be completed within six (6) months from the time the application has been filed, to determine whether:

(a) The preliminary order of proscription should be made permanent;

(b) A permanent order of proscription should be issued in case no preliminary order was issued; or

(c) A preliminary order of proscription should be lifted. It shall be the burden of the applicant to prove that the respondent is a terrorist and an outlawed organization or association within the meaning of Section 26 of this Act before the court issues an order of proscription whether preliminary or permanent.

The permanent order of proscription herein granted shall be published in a newspaper of general circulation. It shall be valid for a period of three (3) years after which, a review of such order shall be made and if circumstances warrant, the same shall be lifted.

SEC. 28. Request to Proscribe from Foreign Jurisdictions and Supranational Jurisdictions. – Consistent with the national interest, all requests for proscription made by another jurisdiction or supranational jurisdiction shall be referred by the Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) to the ATC to determine, with the assistance of the NICA, if proscription under Section 26 of this Act is warranted. If the request for proscription is granted, the ATC shall correspondingly commence proscription proceedings through the DOJ.

SEC. 29. Detention Without Judicial Warrant of Arrest. – The provisions of Article 125 of the Revised Penal Code to the contrary notwithstanding, any law enforcement agent or military personnel, who, having been duly authorized in writing by the ATC has taken custody of a person suspected of committing any of the acts defined and penalized under Sections 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 of this Act, shall, without incurring any criminal liability for delay in the delivery of detained persons to the proper judicial authorities, deliver said suspected person to the proper judicial authority within a period of fourteen (14) calendar days counted from the moment the said suspected person has been apprehended or arrested, detained, and taken into custody by the law enforcement agent or military personnel. The period of detention may be extended to a maximum period of ten (10) calendar days if it is established that (1) further detention of the person/s is necessary to preserve evidence related to terrorism or complete the investigation; (2) further detention of the person/s is necessary to prevent the commission of another terrorism; and (3) the investigation is being conducted properly and without delay.

Immediately after taking custody of a person suspected of committing terrorism or any member of a group of persons, organization or association proscribed under Section 26 hereof, the law enforcement agent or military personnel shall notify in writing the judge of the court nearest the place of apprehension or arrest of the following facts: (a) the time, date, and manner of arrest; (b) the location or locations of the detained suspect/s and (c) the physical and mental condition of the detained suspect/s. The law enforcement agent or military personnel shall likewise furnish the ATC and the Commission on Human Rights (CHR) of the written notice given to the judge.

The head of the detaining facility shall ensure that the detained suspect is informed of his/her rights as a detainee and shall ensure access to the detainee by his/her counsel or agencies and entities authorized by law to exercise visitorial powers over detention facilities.

The penalty of imprisonment of ten (10) years shall be imposed upon the police or law enforcement agent or military personnel who fails to notify any judge as provided in the preceding paragraph.

SEC. 30. Rights of a Person under Custodial Detention. – The moment a person charged with or suspected of committing any of the acts defined and penalized under Sections 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 of this Act is apprehended or arrested and detained, he/she shall forthwith be informed, by the arresting law enforcement agent or military personnel to whose custody the person concerned is brought, of his/her right: (a) to be informed of the nature and cause of his/her arrest, to remain silent and to have competent and independent counsel preferably of his/her choice. If the person cannot afford the services of counsel of his/her choice, the law enforcement agent or military personnel concerned shall immediately contact the free legal assistance unit of the Integrated Bar of the Philippines (IBP) or the Public Attorney’s Office (PAO). It shall be the duty of the free legal assistance unit of the IBP or the PAO thus contacted to immediately visit the person/s detained and provide him/her with legal assistance. These rights cannot be waived except in writing and in the presence of his/her counsel of choice; (b) informed of the cause or causes of his/her detention in the presence of his legal counsel; (c) allowed to communicate freely with his/her legal counsel and to confer with them at any time without restriction; (d) allowed to communicate freely and privately without restrictions with the members of his/her family or with his/her nearest relatives and to be visited by them; and, (e) allowed freely to avail of the service of a physician or physicians of choice.

SEC. 31. Violation of the Rights of a Detainee. – The penalty of imprisonment of ten (10) years shall be imposed upon any law enforcement agent or military personnel who has violated the rights of persons under their custody, as provided for in Sections 29 and 30 of this Act.

Unless the law enforcement agent or military personnel who violated the rights of a detainee or detainees as stated above is duly identified, the same penalty shall be imposed on the head of the law enforcement unit or military unit having custody of the detainee at the time the violation was done.

SEC. 32. Official Custodial Logbook and Its Contents. – The law enforcement custodial unit in whose care and control the person suspected of committing any of the acts defined and penalized under Sections 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 of this Act has been placed under custodial arrest and detention shall keep a securely and orderly maintained official logbook, which is hereby declared as a public document and opened to and made available for the inspection and scrutiny of the lawyer of the person under custody or any member of his/her family or relative by consanguinity or affinity within the fourth civil degree or his/her physician at any time of the day or night subject to reasonable restrictions by the custodial facility. The logbook shall contain a clear and concise record of: (a) the name, description, and address of the detained person; (b) the date and exact time of his/her initial admission for custodial arrest and detention; (c) the name and address of the physician or physicians who examined him/her physically and medically; (d) the state of his/her health and physical condition at the time of his/her initial admission for custodial detention; (e) the date and time of each removal of the detained person from his/her cell for interrogation or for any purpose; (f) the date and time of his/her return to his/her cell; (g) the name and address of the physician or physicians who physically and medically examined him/her after each interrogation; (h) a summary of the physical and medical findings on the detained person after each of such interrogation; (i) the names and addresses of his/her family members and nearest relatives, if any and if available; (j) the names and addresses of persons, who visit the detained person; (k) the date and time of each of such visit; (l) the date and time of each request of the detained person to communicate and confer with his/her legal counsel or counsels; (m) the date and time of each visit, and date and time of each departure of his/her legal counsel or counsels; and (n) all other important events bearing on and all relevant details regarding the treatment of the detained person while under custodial arrest and detention.

The said law enforcement custodial unit shall, upon demand of the aforementioned lawyer or members of the family or relatives within the fourth civil degree of consanguinity or affinity of the person under custody or his/her physician, issue a certified true copy of the entries of the logbook relative to the concerned detained person subject to reasonable restrictions by the custodial facility. This certified true copy may be attested by the person who has custody of the logbook or who allowed the party concerned to scrutinize it at the time the demand for the certified true copy is made.

The law enforcement custodial unit who fails to comply with the preceding paragraphs to keep an official logbook shall suffer the penalty of imprisonment of ten (10) years.

SEC. 33. No Torture or Coercion in Investigation and Interrogation. – The use of torture and other cruel, inhumane and degrading treatment or punishment, as defined in Sections 4 and 5 of Republic Act No. 9745 otherwise known as the “Anti-Torture Act of 2009,” at any time during the investigation or interrogation of a detained suspected terrorist is absolutely prohibited and shall be penalized under said law. Any evidence obtained from said detained person resulting from such treatment shall be, in its entirety, inadmissible and cannot be used as evidence in any judicial, quasi-judicial, legislative, or administrative investigation, inquiry, proceeding, or hearing.

SEC. 34. Restriction on the Right to Travel. – Prior to the filing of an information for any violation of Sections 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 of this Act, the investigating prosecutor shall apply for the issuance of a precautionary hold departure order (PHDO) against the respondent upon a preliminary determination of probable cause in the proper Regional Trial Court.

Upon the filing of the information regarding the commission of any acts defined and penalized under the provisions of this Act, the prosecutor shall apply with the court having jurisdiction for the issuance of a hold departure order (HDO) against the accused. The said application shall be accompanied by the complaint-affidavit and its attachments, personal details, passport number, and a photograph of the accused, if available.

In cases where evidence of guilt is not strong, and the person charged is entitled to bail and is granted the same, the court, upon application by the prosecutor, shall limit the right of travel of the accused to within the municipality or city where he/she resides or where the case is pending, in the interest of national security and public safety, consistent with Article III, Section 6 of the Constitution. The court shall immediately furnish the DOJ and the Bureau of Immigration (BI) with the copy of said order. Travel outside of said municipality or city, without the authorization of the court, shall be deemed a violation of the terms and conditions of his/her bail, which shall be forfeited as provided under the Rules of Court.

He/she may also be placed under house arrest by order of the court at his/her usual place of residence.

While under house arrest, he/she may not use telephones, cellphones, e-mails, computers, the internet, or other means of communications with people outside the residence until otherwise ordered by the court.

If the evidence of guilt is strong, the court shall immediately issue an HDO and direct the DFA to initiate the procedure for the cancellation of the passport of the accused.

The restrictions above-mentioned shall be terminated upon the acquittal of the accused or of the dismissal of the case filed against him/her or earlier upon the discretion of the court on motion of the prosecutor or of the accused.

SEC. 35. Anti-Money Laundering Council Authority to Investigate, inquire into and Examine Bank Deposits. – Upon the issuance by the court of a preliminary order of proscription or in case of designation under Section 25 of this Act, the AMLC, either upon its own initiative or at the request of the ATC, is hereby authorized to investigate: (a) any property or funds that are in any way related to financing of terrorism as defined and penalized under Republic Act No. 10168, or violation of Sections 4, 6, 7, 10, 11 or 12 of this Act; and (b) property or funds of any person or persons in relation to whom there is probable cause to believe that such person or persons are committing or attempting or conspiring to commit, or participating in or facilitating the financing of the aforementioned sections of this Act.

The AMLC may also enlist the assistance of any branch, department, bureau, office, agency or instrumentality of the government, including government-owned and -controlled corporations in undertaking measures to counter the financing of terrorism, which may include the use of its personnel, facilities and resources.

For purposes of this section and notwithstanding the provisions of Republic Act No. 1405, otherwise known as the “Law on Secrecy of Bank Deposits”. as amended; Republic Act No. 6426, otherwise known as the “Foreign Currency Deposit Act of the Philippines”, as amended; Republic Act No. 8791, otherwise known as “The General Banking Law of 2000” and other laws, the AMLC is hereby authorized to inquire into or examine deposits and investments with any banking institution or non-bank financial institution and their subsidiaries and affiliates without a court order.

SEC. 36. Authority to Freeze. – Upon the issuance by the court of a preliminary order of proscription or in case of designation under Section 25 of this Act, the AMLC, either upon its own initiative or request of the ATC, is hereby authorized to issue an ex parte order to freeze without delay: (a) any property or funds that are in any way related to financing of terrorism as defined and penalized under Republic Act No. 10168, or any violation of Sections 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 or 12 of this Act; and (b) property or funds of any person or persons in relation to whom there is probable cause to believe that such person or persons are committing or attempting or conspiring to commit, or participating in or facilitating the financing of the aforementioned sections of this Act.

The freeze order shall be effective for a period not exceeding twenty (20) days. Upon a petition filed by the AMLC before the expiration of the period, the effectivity of the freeze order may be extended up to a period not exceeding six (6) months upon order of the Court of Appeals: Provided, That, the twenty-day period shall be tolled upon filing of a petition to extend the effectivity of the freeze order.

Notwithstanding the preceding paragraphs, the AMLC, consistent with the Philippines’ international obligations, shall be authorized to issue a freeze order with respect to property or funds of a designated organization, association, group or any individual to comply with binding terrorism-related resolutions, including UNSCR No. 1373 pursuant to Article 41 of the charter of the UN. Said freeze order shall be effective until the basis for the issuance thereof shall have been lifted. During the effectivity of the freeze order, an aggrieved party may, within twenty (20) days from issuance, file with the Court of Appeals a petition to determine the basis of the freeze order according to the principle of effective judicial protection: Provided, That the person whose property or funds have been frozen may withdraw such sums as the AMLC determines to be reasonably needed for monthly family needs and sustenance including the services of counsel and the family medical needs of such person.

However, if the property or funds subject of the freeze order under the immediately preceding paragraph are found to be in any way related to financing of terrorism as defined and penalized under Republic Act No. 10168, or any violation of Sections 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 or 12 of this Act committed within the jurisdiction of the Philippines, said property or funds shall be the subject of civil forfeiture proceedings as provided under Republic Act No. 10168.

SEC. 37. Malicious Examination of a Bank or a Financial Institution. – Any person who maliciously, or without authorization, examines deposits, placements, trust accounts, assets, or records in a bank or financial institution in relation to Section 36 hereof, shall suffer the penalty of four (4) years of imprisonment.

SEC. 38. Safe Harbor. – No administrative, criminal or civil proceedings shall lie against any person acting in good faith when implementing the targeted financial sanctions as provided under pertinent United Nations Security Resolutions.

SEC. 39. Bank Officials and Employees Defying a Court Authorization. – An employee, official, or a member of the board of directors of a bank, or financial institution, who after being duly served with the written order of authorization from the Court of Appeals, refuses to allow the examination of the deposits, placements, trust accounts, assets, and records of a terrorist or an outlawed group of persons, organization or association, in accordance with Sections 25 and 26 hereof, shall suffer the penalty of imprisonment of four (4) years.

SEC. 40. Immunity and Protection of Government Witnesses. – The immunity and protection of government witnesses shall be governed by the provisions of Republic Act No. 6981, otherwise known as “The Witness Protection, Security and Benefits Act”.

SEC. 41. Penalty for Unauthorized Revelation of Classified Materials. – The penalty of imprisonment of ten (10) years shall be imposed upon any person, law enforcement agent or military personnel, judicial officer or civil servant who, not being authorized by the Court of Appeals to do so, reveals in any manner or form any classified information under this Act. The penalty imposed herein is without prejudice and in addition to any corresponding administrative liability the offender may have incurred for such acts.

SEC. 42. Infidelity in the Custody of Detained Persons. – Any public officer who has direct custody of a detained person under the provisions of this Act and, who, by his deliberate act, misconduct or inexcusable negligence, causes or allows the escape of such detained person shall be guilty of an offense and shall suffer the penalty of ten (10) years of imprisonment.

SEC. 43. Penalty for Furnishing False Evidence, Forged Document, or Spurious Evidence. – The penalty of imprisonment of six (6) years shall be imposed upon any person who knowingly furnishes false testimony, forged document or spurious evidence in any investigation or hearing conducted in relation to any violations under this Act.

SEC. 44. Continuous Trial. – In cases involving crimes defined and penalized under the provisions of this Act, the judge concerned shall set the case for continuous trial on a daily basis from Monday to Thursday or other short-term trial calendar to ensure compliance with the accused’s right to speedy trial.

SEC. 45. Anti-Terrorism Council. – An Anti-Terrorism Council (ATC) is hereby created. The members of the ATC are: (1) the Executive Secretary, who shall be its Chairperson; (2) the National Security Adviser who shall be its Vice Chairperson; and (3) the Secretary of Foreign Affairs; (4) the Secretary of National Defense; (5) the Secretary of the Interior and Local Government; (6) the Secretary of Finance; (7) the Secretary of Justice; (8) the Secretary of Information and Communications Technology; and (9) the Executive Director of the Anti-Money Laundering Council (AMLC) Secretariat as its other members.

The ATC shall implement this Act and assume the responsibility for the proper and effective implementation of the policies of the country against terrorism. The ATC shall keep records of its proceedings and decisions. All records of the ATC shall be subject to such security classifications as the ATC may, in its judgment and discretion, decide to adopt to safeguard the safety of the people, the security of the Republic, and the welfare of the nation.

The NICA shall be the Secretariat of the ATC. The ATC shall define the powers, duties, and functions of the NICA as Secretariat of the ATC. The Anti-Terrorism Council-Program Management Center (ATC-PMC) is hereby institutionalized as the main coordinating and program management arm of the ATC. The ATC shall define the powers, duties, and functions of the ATC-PMC. The Department of Science and Technology (DOST), the Department of Transportation (DOTr), the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE), the Department of Education (DepEd), the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD), the Presidential Adviser for Peace, Reunification and Unity (PAPRU, formerly PAPP), the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM), the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI), the BI, the Office of Civil Defense (OCD), the Intelligence Service of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (ISAFP), the Philippine Center on Transnational Crimes (PCTC), the Philippine National Police (PNP) intelligence and investigative elements, the Commission on Higher Education (CHED), and the National Commission on Muslim Filipinos (NCMF) shall serve as support agencies of the ATC.

The ATC shall formulate and adopt comprehensive, adequate, efficient, and effective plans, programs, or measures to prevent, counter, suppress, or eradicate the commission of terrorism in the country and to protect the people from such acts. In pursuit of said mandate, the ATC shall create such focus programs to prevent and counter terrorism as necessary, to ensure the counterterrorism operational awareness of concerned agencies, to conduct legal action and to pursue legal and legislative initiatives to counter terrorism, prevent and stem terrorist financing, and to ensure compliance with international commitments to counterterrorism-related protocols and bilateral and/or multilateral agreements, and identify the lead agency for each program, such as:

(a) Preventing and countering violent extremism program – The program shall address the conditions conducive to the spread of terrorism which include, among others: ethnic, national, and religious discrimination; socio-economic disgruntlement; political exclusion; dehumanization of victims of terrorism; lack of good governance; and prolonged unresolved conflicts by winning the hearts and minds of the people to prevent them from engaging in violent extremism. It shall identify, integrate, and synchronize all government and non¬-government initiatives and resources to prevent radicalization and violent extremism, thus reinforce and expand an after¬-care program;

(b) Preventing and combating terrorism program – The program shall focus on denying terrorist groups access to the means to carry out attacks to their targets and formulate response to its desired impact through decisive engagements. The program shall focus on operational activities to disrupt and combat terrorism activities and attacks such as curtailing, recruitment, propaganda, finance and logistics, the protection of potential targets, the exchange of intelligence with foreign countries, and the arrest of suspected terrorists;

(c) International affairs and capacity building program – The program shall endeavor to build the State’s capacity to prevent and combat terrorism by strengthening the collaborative mechanisms between and among ATC members and support agencies and facilitate cooperation among relevant stakeholders, both local and international, in the battle against terrorism; and

(d) Legal affairs program – The program shall ensure respect for human rights and adherence to the rule of law as the fundamental bases of the fight against terrorism. It shall guarantee compliance with the same as well as with international commitments to counter-terrorism-related protocols and bilateral and/or multilateral agreements.

Nothing herein shall be interpreted to empower the ATC to exercise any judicial or quasi-judicial power or authority.

SEC. 46. Functions of the Council. – In pursuit of its mandate in the previous Section, the ATC shall have the following functions with due regard for the rights of the people as mandated by the Constitution and pertinent laws:

(a) Formulate and adopt plans, programs, and preventive and counter-measures against terrorists and terrorism in the country;

(b) Coordinate all national efforts to suppress and eradicate terrorism in the country and mobilize the entire nation against terrorism prescribed in this Act;

(c) Direct the speedy investigation and prosecution of all persons detained or accused for any crime defined and penalized under this Act;

(d) Monitor the progress of the investigation and prosecution of all persons accused and/or detained for any crime defined and penalized under the provisions of this Act;

(e) Establish and maintain comprehensive database information systems on terrorism, terrorist activities, and counter-terrorism operations;

(f) Enlist the assistance of and file the appropriate action with the AMLC to freeze and forfeit the funds, bank deposits, placements, trust accounts, assets and property of whatever kind and nature belonging (i) to a person suspected of or charged with alleged violation of any of the acts defined and penalized under Sections 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 of this Act, (ii) between members of a judicially declared and outlawed terrorist organization or association as provided in Section 26 of this Act; (iii) to designated persons defined under Section 3(e) of R. A. No. 10168; (iv) to an individual member of such designated persons; or (v) any individual, organization, association or group of persons proscribed under Section 26 hereof;

(g) Grant monetary rewards and other incentives to informers who give vital information leading to the apprehension, arrest, detention, prosecution, and conviction of person or persons found guilty for violation of any of the acts defined and penalized under Sections 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 of this Act: Provided, That, no monetary reward shall be granted to informants unless the accused’s demurrer to evidence has been denied or the prosecution has rested its case without such demurrer having been filed;

(h) Establish and maintain coordination with and the cooperation and assistance of other states, jurisdictions, international entities and organizations in preventing and combating international terrorism;

(i) Take action on relevant resolutions issued by the UN Security Council acting under Chapter VII of the UN Charter; and consistent with the national interest, take action on foreign requests to designate terrorist individuals, associations, organizations or group of persons;

G) Take measures to prevent the acquisition and proliferation by terrorists of weapons of mass destruction;

(k) Lead in the formulation and implementation of a national strategic plan to prevent and combat terrorism;

(l) Request the Supreme Court to designate specific divisions of the Court of Appeals or Regional Trial Courts to handle all cases involving the crimes defined and penalized under this Act;

(m) Require other government agencies, offices and entities and officers and employees and non-government organizations, private entities and individuals to render assistance to the ATC in the performance of its mandate; and

(n) Investigate motu propio or upon complaint any report of abuse, malicious application or improper implementation by any person of the provisions of this Act.

SEC. 47. Commission on Human Rights (CHR). – The CHR shall give the highest priority to the investigation and prosecution of violations of civil and political rights of persons in relation to the implementation of this Act.

SEC. 48. Ban on Extraordinary Rendition. – No person suspected or convicted of any of the crimes defined and penalized under the provisions of Sections 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 or 12 of this Act shall be subjected to extraordinary rendition to any country.

SEC. 49. Extraterritorial Application. – Subject to the provision of any treaty of which the Philippines is a signatory and to any contrary provision of any law of preferential application, the provisions of this Act shall apply:

(a) To a Filipino citizen or national who commits any of the acts defined and penalized under Sections 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 of this Act outside the territorial jurisdiction of the Philippines;

(b) To individual persons who, although physically outside the territorial limits of the Philippines, commit any of the crimes mentioned in Paragraph (a) hereof inside the territorial limits of the Philippines;

(c) To individual persons who, although physically outside the territorial limits of the Philippines, commit any of the said crimes mentioned in Paragraph (a) hereof on-board Philippine ship or Philippine airship;

(d) To individual persons who commit any of said crimes mentioned in Paragraph (a) hereof within any embassy, consulate, or diplomatic premises belonging to or occupied by the Philippine government in an official capacity:

(e) To individual persons who, although physically outside the territorial limits of the Philippines, commit said crimes mentioned in Paragraph (a) hereof against Philippine citizens or persons of Philippine descent, where their citizenship or ethnicity was a factor in the commission of the crime; and

(f) To individual persons who, although physically outside the territorial limits of the Philippines, commit said crimes directly against the Philippine government.

In case of an individual who is neither a citizen or a national of the Philippines who commits any of the crimes mentioned in Paragraph (a) hereof outside the territorial limits of the Philippines, the Philippines shall exercise jurisdiction only when such individual enters or is inside the territory of the Philippines: Provided, That, in the absence of any request for extradition from the state where the crime was committed or the state where the individual is a citizen or national, or the denial thereof, the ATC shall refer the case to the BI for deportation or to the DOJ for prosecution in the same manner as if the act constituting the offense had been committed in the Philippines.

SEC. 50. Joint Oversight Committee. – Upon the effectivity of this Act, a Joint Congressional Oversight Committee is hereby constituted. The Committee shall be composed of twelve (12) members with the chairperson of the Committee on Public Order of the Senate and the House of Representatives as members and five (5) additional members from each House to be designated by the Senate President and the Speaker of the House of Representatives, respectively. The minority shall be entitled to a pro-rata representation but shall have at least two (2) representatives in the Committee.

In the exercise of its oversight functions, the Joint Congressional Oversight Committee shall have the authority to summon law enforcement or military officers and the members of the ATC to appear before it, and require them to answer questions and submit written reports of the acts they have done in the implementation of this Act and render an annual report to both Houses of Congress as to its status and implementation.

SEC. 51. Protection of Most Vulnerable Groups. – There shall be due regard for the welfare of any suspects who are elderly, pregnant, persons with disability, women and children while they are under investigation, interrogation or detention.

SEC. 52. Management of Persons Charged Under this Act. – The Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP) and the Bureau of Corrections (BuCoR) shall establish a system of assessment and classification for persons charged for committing terrorism and preparatory acts punishable under this Act. Said system shall cover the proper management, handling, and interventions for said persons detained.

Persons charged under this Act shall be detained in existing facilities of the BJMP and the BuCoR.

SEC. 53. Trial of Persons Charged Under this Act. – Any person charged for violations of Sections 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 or 12 of this Act shall be tried in special courts created for this purpose. In this regard, the Supreme Court shall designate certain branches of the Regional Trial Courts as anti¬-terror courts whose jurisdiction is exclusively limited to try violations of the above-mentioned provisions of this Act.

Persons charged under the provisions of this Act and witnesses shall be allowed to remotely appear and provide testimonies through the use of video-conferencing and such other technology now known or may hereafter be known to science as approved by the Supreme Court.

SEC. 54. Implementing Rules and Regulations. – The ATC and the DOJ, with the active participation of police and military institutions, shall promulgate the rules and regulations for the effective implementation of this Act within ninety (90) days after its effectivity. They shall ensure the full dissemination of such rules and regulations to both Houses of Congress, and all officers and members of various law enforcement agencies.

SEC. 55. Separability Clause. – If for any reason any part or provision of this Act is declared unconstitutional or invalid, the other parts or provisions hereof which are not affected thereby shall remain and continue to be in full force and effect.

SEC. 56. Repealing Clause. – Republic Act No. 9372, otherwise known as the “Human Security Act of 2007”, is hereby repealed. All laws, decrees, executive orders, rules or regulations or parts thereof, inconsistent with the provisions of this Act are hereby repealed, amended, or modified accordingly.

SEC. 57. Saving Clause. – All judicial decisions and orders issued, as well as pending actions relative to the implementation of Republic Act No. 9372, otherwise known as the “Human Security Act of 2007”, prior to its repeal shall remain valid and effective.

SEC. 58. Effectivity. – This Act shall take effect fifteen (15) days after its complete publication in the Official Gazette or in at least two (2) newspapers of general circulation.

ALAN PETER S. CAYETANO Speaker of the House of Representatives

VICENTE C. SOTTO III President of the Senate

This Act was passed by the Senate of the Philippines as Senate Bill No. 1083 on February 26, 2020, and adopted by the House of Representatives as an amendment to House Bill No. 6875 on June 5, 2020, respectively.

JOSE LUIS G. MONTALES Secretary General House of Representatives

MYRA MARIE D. VILLARICA Secretary of the Senate

Approved: July 03, 2020

RODRIGO ROA DUTERTE President of the Philippines

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Discover more from the pinoy site.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

VERA FILES FACT SHEET: Mga kailangan mong malaman tungkol sa panukalang anti-terrorism bill ng Senado

Basahin sa Ingles

Ipinasa ng Senado sa third at final reading noong Peb. 26 ang Senate Bill 1083 , o “Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020,” isang panukala na naglalayong i-update at ipawalang-bisa ang ilang mga probisyon ng Human Security Act ( HSA ) at “ palakasin ” ang kakayahan ng bansa na labanan ang terorismo.

Labinsiyam na mga senador ang bumoto pabor sa panukalang batas; tanging mga senador ng minorya na sina Francis “Kiko” Pangilinan at Risa Hontiveros ang bumoto laban dito. Sa pagpapaliwanag ng kanyang boto, sinabi ni Pangilinan na ang mga pagbabago sa HSA ay “nakakabahala” at maaaring gamitin ang batas na “isang mas masamang kasangkapan sa panunupil, sa halip na isang instrumento para hadlangan ang mga terorista,” habang si Hontiveros, sa isang pakikipanayam sa media, ay nagsabing ang “demokratiko kalayaan “ay hindi dapat isakripisyo “sa pangalan ng seguridad.”

Paano naiiba ang iminungkahing Anti-Terrorism law ng Senado sa HSA? Narito ang tatlong bagay na kailangan mong malaman:

1. Pinalalawak ng panukalang batas ang kahulugan ng terrorist acts.

Ang HSA, na ipinatupad noong 2007, ay tumutukoy sa terorismo bilang paglabag sa ilang mga probisyon ng Revised Penal Code — tulad ng piracy, paghihimagsik, insureksyon, kudeta, murder, kidnapping at serious illegal detention — para sa layuning maghasik ng “malawak at pambihirang takot at panic “sa mga tao upang “pilitin ang pamahalaan na bumigay sa kahilingang labag sa batas.” (Tingnan ang VERA FILES FACT SHEET: Bakit peligroso ang ‘red-tagging’ )

Sa ilalim ng Anti-Terrorism bill, sa kabilang banda, ang terorismo ay pagsasagawa ng mga tao sa loob o labas ng bansa ng ilang mga pagkilos, “anuman mang yugto ng pagsasakatuparan,” para matakot ang buo, o isang seksyon ng publiko, at lumikha ng isang “kapaligirang saklot ng takot” upang:

- pukawin o impluwensyahan [sa pamamagitan ng] pananakot ang pamahalaan o alinman sa mga internasyonal na organisasyon;

- ibagsak o sirain ang mga pangunahing istrukturang pampulitika, pang-ekonomiya, o panlipunan ng bansa;

- lumikha ng isang pampublikong emergency; o,

- pahinain nang husto ang kaligtasan ng publiko.

Ang mga gawaing ito, na may parusang pagkabilanggo ng habang buhay na walang parole, ay:

Pinalawak rin ng panukalang batas ang mga uri ng kasong terorismo:

Ang ilan sa mga pagkilos na ito ay dati nang isinasaalang-alang bilang paunang mga krimen sa terorismo at hindi mismo mga gawaing terorista. Sinabi ni Sen. Panfilo “Ping” Lacson, ang sponsor ng panukalang batas, na ang panukalang batas ay naging mas “proactive” at “direkta” dahil sa pag-alis ng mga predicate na krimen.

2. Pinalawig ng panukalang batas ang panahon ng detensyon ng pinaghihinalaang terorista matapos maaresto ng walang warrant at tinanggal ang P500,000 na multa para sa mga nagkakamaling mga opisyal.

Sa ilalim ng HSA, ang isang tao na naaresto nang walang warrant dahil sa terorismo ay maaaring makulong nang maximum na tatlong araw, at dapat na iharap, bago ang detensyon, sa pinakamalapit na hukom, na magpapasya kung ang suspek ay dumaan sa alinman sa pisikal, moral o psychological na pagpapahirap, bukod sa iba pang mga gawain.

Ang pagkabigo na palayain ang suspek sa tamang oras o iharap ang mga ito sa hukom ay magreresulta sa parusang pagkabilanggo sa loob ng 10 hanggang 12 taon.

Ang Sec. 29 ng panukalang batas, sa kabilang banda, ay naglalayong palawakin ang mga araw ng pagkakulong sa 14, na maaaring pahabain ng 10 pang araw, kung kinakailangan, upang mapanatili ang katibayan, maiwasan ang darating na pag-atake ng terorista, o maayos na magtapos ang pagsisiyasat.

Hindi nito isinama ang probisyon na nag-uutos sa mga tagapagpatupad ng batas na iharap ang pinaghihinalaang terorista sa pinakamalapit na hukom bago ikulong. Ang pagpapanatili sa suspek ng higit sa 14 na araw nang walang mga kondisyon para sa extension ay may parusa ng 10 taong pagkakabilanggo.

Ang parehong mga panukala ay nagbibigay ng mga karapatan sa nakulong, kabilang ang isang logbook sa mga pamamaraan at mga bisita ng nakakulong, ang kanilang karapatan na magkaroon ng abugado, ang kanilang karapatan sa privacy, at ang kanilang mga karapatan sa pagtanggap ng bisita.

Ang panukalang batas, gayunpaman, ay tinanggal ang probisyon tungkol sa danyos para sa hindi napatunayang kaso ng terorismo sa ilalim ng Sec. 50 ng HSA, na nagbibigay sa sinumang inaakusahan at hindi napatunayan na terorista ng P500,000 para sa bawat araw na ginugol sa detensyon. Sinabi ni Lacson na ang probisyon na ito ang dahilan ng pag-aatubili ng mga tagapagpatupad ng batas na magsampa ng mga kaso batay sa HSA dahil sa takot na magbayad ng multa.

3. Ang panukalang batas ay nagpapalawak ng panahon na maaaring subaybayan ang komunikasyon ng isang tao.

Kasalukuyang pinapayagan ng HSA nang hanggang 30 araw na pagsubaybay sa mga komunikasyon sa telepono ng suspek, kung may probable cause at ang tagapagpatupad ng batas o mga tauhan ng militar ay nakakuha ng permiso mula sa Court of Appeals. Ang panahon ng pag wiretap ay maaaring mapalawig o ma renew ng hindi hihigit sa 30 araw kung ang kaso ay para sa interes ng publiko at ang orihinal na aplikante ay humingi ng pahintulot para dito.

Ang Sec. 16 ng anti-terrorism bill, sa kabilang banda, ay pinalawak ang orihinal na 30-araw hanggang 60 araw, ngunit pinapanatili ang panahon at mga kinakailangan para sa isang extension.

Sa parehong mga kaso, ang mga komunikasyon sa pagitan ng mga abogado at kliyente, mga doktor at mga pasyente, mamamahayag at pinagkukunan ng impormasyon, at kumpidensyal na sulat kaugnay ng negosyo ay hindi pinapayagan na ma-record.

Mga Pinagmulan

Senate of the Philippines, Senate OKs bill repealing the Anti-Terrorism Law , Feb. 26, 2020

Senate of the Philippines, Senate Bill No. 1083

Official Gazette, Republic Act No. 9372

Interaksyon, Questions, fears over ‘human rights violations’ as Senate OKs new Anti Terrorism bill , Feb. 28, 2020

Senate of the Philippines, Explanation of No Vote of Sen. Francis “Kiko” Pangilinan on Senate Bill No. 1083 , Feb. 26, 2020

ANC 24/7, Anti-terrorism act may be used to target groups expressing dissent, says Hontiveros | Headstart , Feb. 27, 2020

National Union of Peoples’ Lawyers official Facebook page, Press Statement on the Passage of Senate Bill No. 1083 , Feb. 28, 2020

Senate of the Philippines, Sotto: Anti-Terror Act , Feb. 27, 2020

Panfilo ‘Ping’ Lacson, Interview on DZBB: Proactive na Tayo vs Terorismo, Feb. 28, 2020

Panfilo ‘Ping’ Lacson, Kapihan sa Senado forum, Feb. 27, 2020

(Ginagabayan ng code of principles ng International Fact-Checking Network sa Poynter, ang VERA Files ay sumusubaybay sa mga maling pahayag, flip-flops, nakaliligaw na mga pahayag ng mga pampublikong opisyal at kilalang personalidad, at pinasisinungalingan ang mga ito gamit ang tunay na ebidensya. Alamin ang inisyatibong ito at aming pamamaraan .)

Read other interesting stories:

Click thumbnails to read related articles.

VERA FILES FACT SHEET: What you need to know about the Senate’s anti-terrorism bill

VERA FILES FACT CHECK: Roque’s claim that Duterte ‘did not ask’ for anti-terror bill needs context; errs in saying Senate passed measure in previous Congress

Vera files fact check: pahayag ni roque na ‘hindi hiningi’ ni duterte ang anti-terror bill nangangailangan ng konteksto; mali sa pagsasabi na naipasa ng senado ang panukalang batas sa nakaraang kongreso.

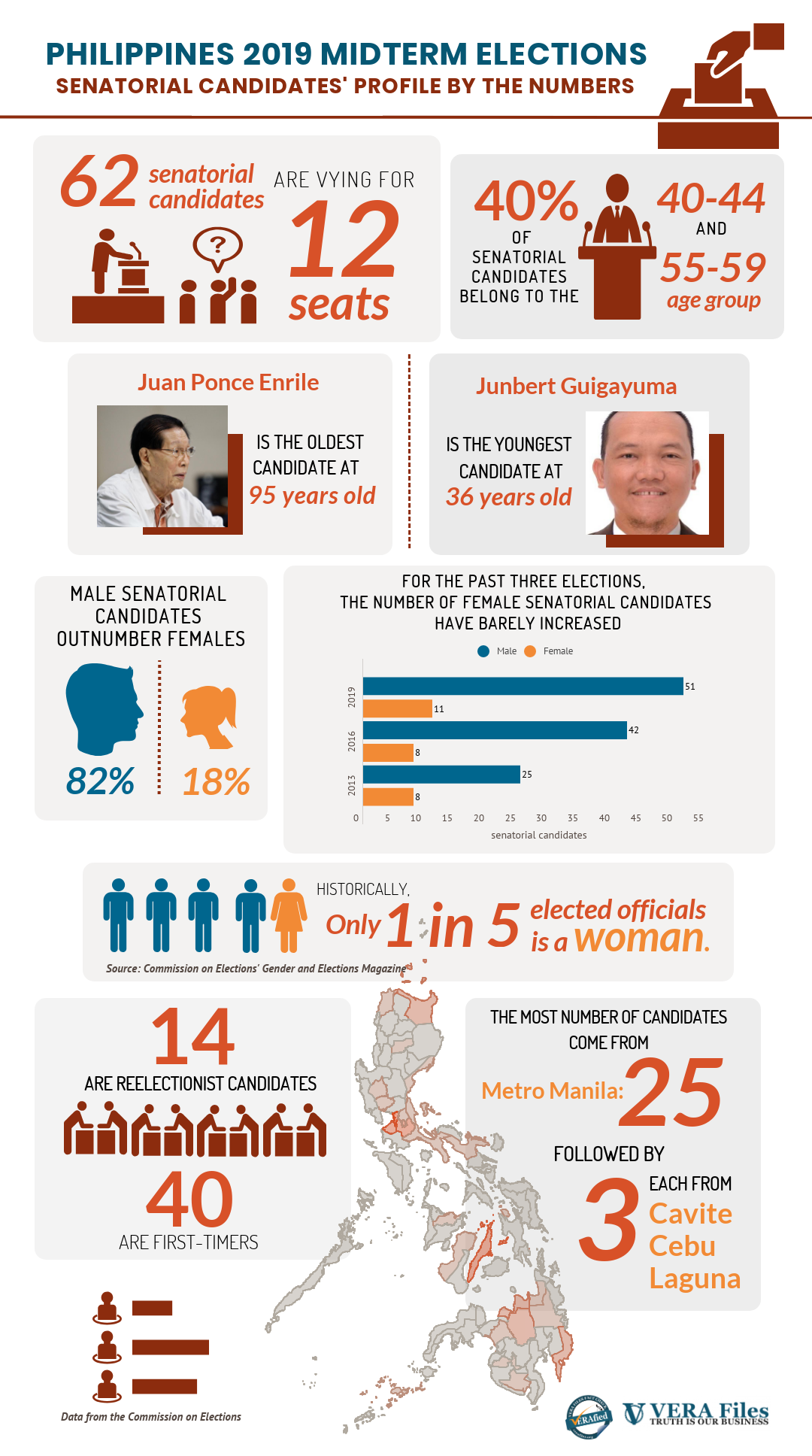

VERA FILES FACT SHEET: By the numbers: Candidates for national posts

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Reddit

- Save to your Google bookmark

- Save to Pocket

TELETABLOIDISTA

Social media, bakit mahalaga ang anti-terror law.

Napirmahan na po ni Pangulong Rodrigo Duterte bilang batas ang Republic Act 11479 o ang Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020 nitong Biyernes, July 3 matapos ang masusing pag-aaral ng mga abugado ng gobyerno.

Maituturing pong isa ito sa mga naging tampok na pangyayari sa unang linggo ng Hulyo dahil matagal itong inabangan ng maraming Pilipino.

Ang paglagda po ni Pangulo Duterte sa Anti-Terrorism Law ay isa pong patunay na seryoso ang kanyang administrasyon na matuldukan ang terorismo na matagal ng nagdudulot ng kaguluhan at karahasan sa bansa na ang mga biktima ay mga inosenteng Pilipino.

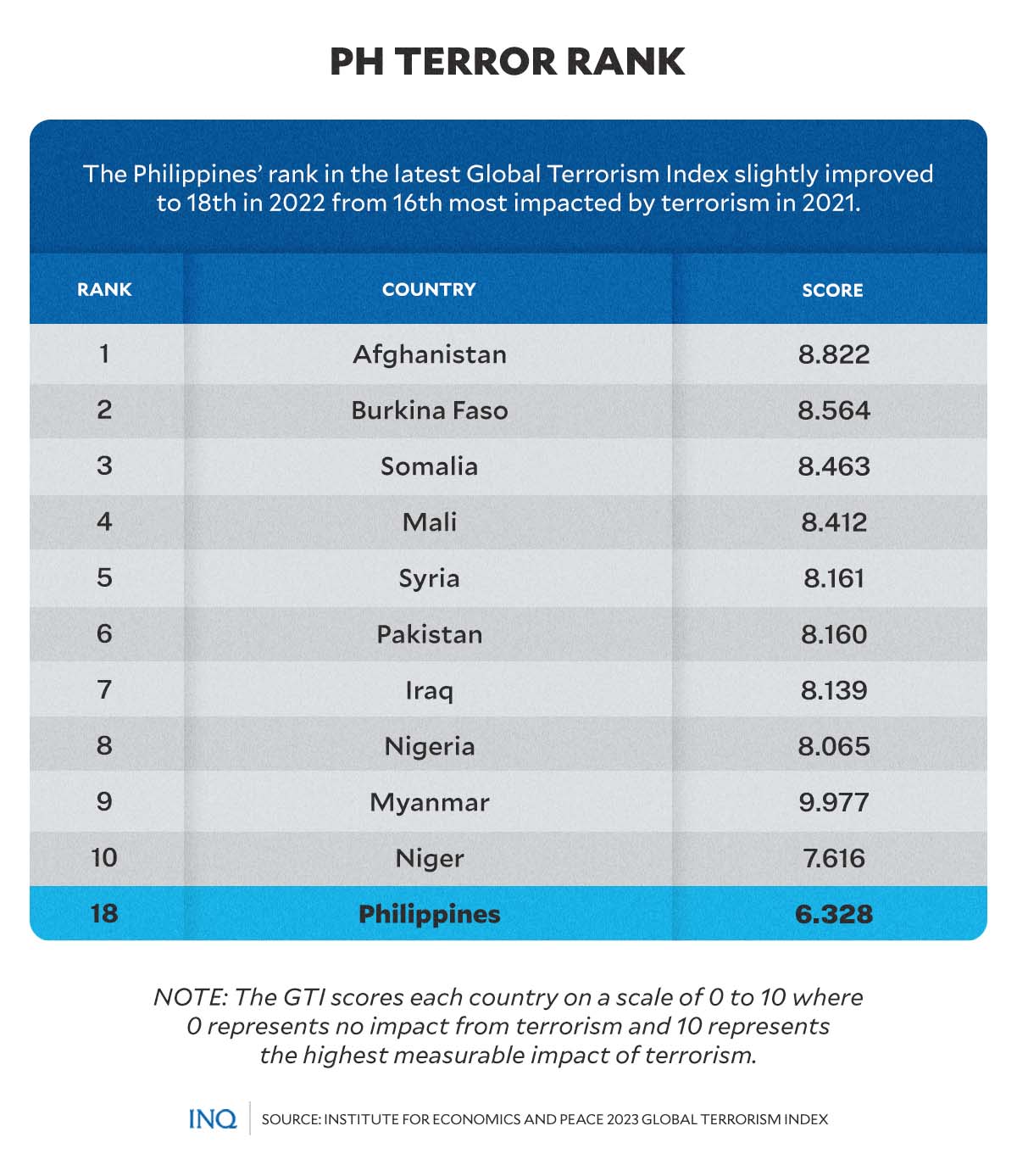

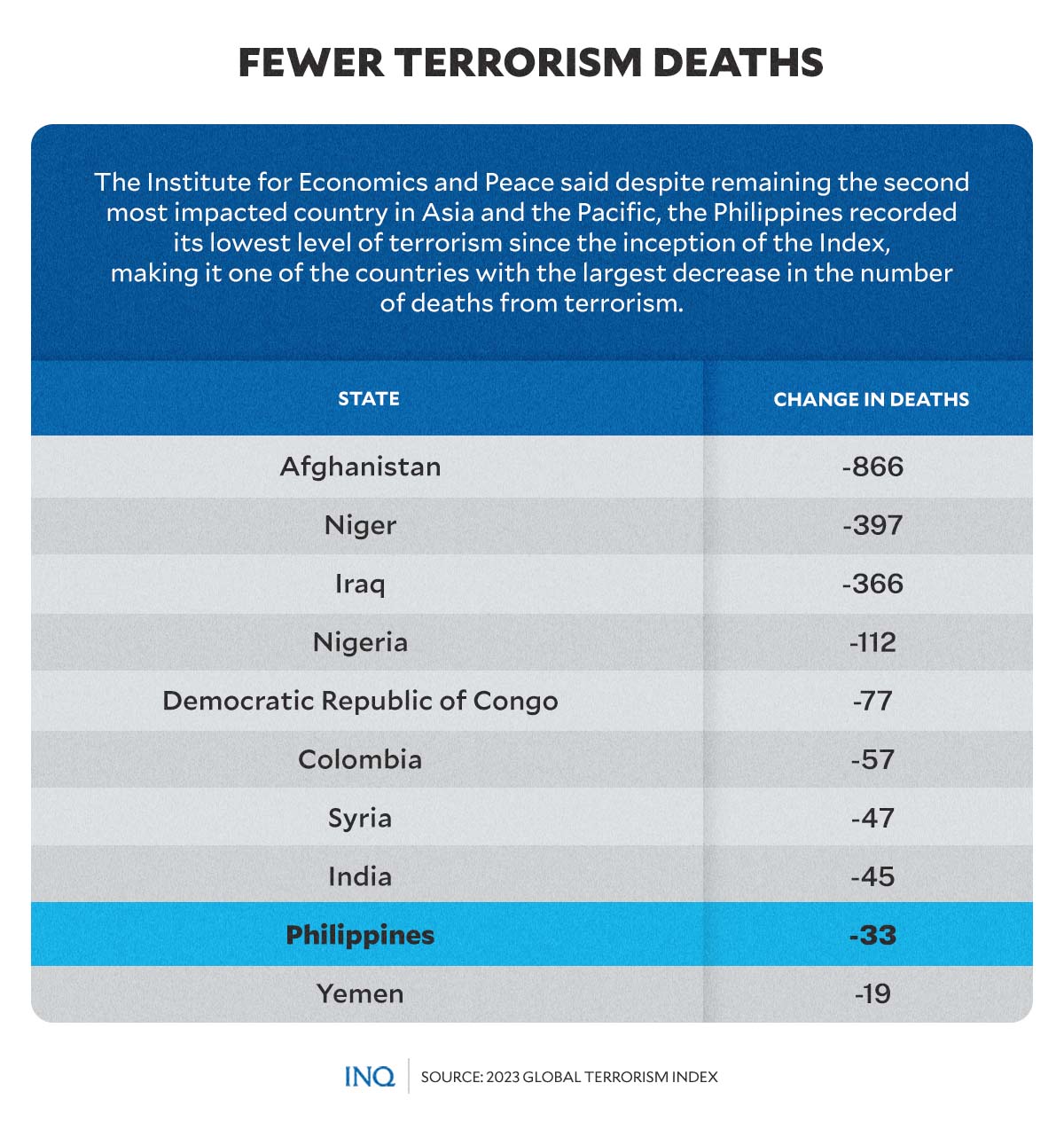

Isa po ang Pilipinas sa mga bansang nakakaranas ng terorismo. Patunay dito ang pagkakalagay ng bansa sa listahan ng Global Terrorism Index of 2019, dahilan kaya naman pursigedo ang Duterte administration na mawakasan na ito .

Sa pamamagitan po ng bagong nilagdaang batas, aasahan ang mga mas pinaigting na mekanismong ilalatag ng gobyerno para mahadlangan ang mga banta at mga pagtatangka ng mga terorista sa sambayanan kabilang na po ang mga dayuhang terorista na nagtatangkang magtatag ng kanilang lokal na grupo sa ating bansa.

May mga safeguards po ang bagong Anti-Terror Law na titiyak sa karapatang pantao at laban sa pang-aabuso.

Sinisiguro ko po na ang aking tanggapan, ang Presidential Communications Operations Office (PCOO) ay makikipagtulungan sa lahat ng ahensiya ng gobyerno para matugunan ang problema sa terorismo ng hindi malalabag ang karapatang pantao at rule of law.

Mayroon po tayong dating batas kontra-terorismo, subalit may mga butas ito kaya nabuo ang bagong Anti-Terror Act of 2020 para mas lalong bigyan ng ngipin ang paglaban sa mga terorista at tiyaking mapanagot ang mga ito sa kanilang mga kasalanang nagawa sa mamamayan at sa bansa.

Marami ang kontra sa bagong batas na ito dahil sa paniwala ng ilang grupo at oposisyon na gagamitin ito ng Duterte administration laban sa mga kritiko ng gobyerno. Pero walang batayan ang kanilang paniniwala laban sa Anti-Terror Law.

Batay po sa depenisyon, ang terorismo ay isang aksiyon ng isang tao o grupo sa loob o labas ng Pilipinas na ang layunin ay pumatay at magdulot ng matinding pinsala o maglagay sa panganib sa buhay ng isang tao o kaya ay manira ng mga pasilidad ng gobyerno o ng pribadong ari-arian sa pamamagitan ng mga armas, pampasabog, biologocal , nuclear , radiological o chemical weapons.

Wala pong pinipiling lugar, oras at araw ang mga terorista sa kanilang paghahasik ng karahasan kaya ito ang nais ng gobyerno na mahadlangan para sa kaligtasan at seguridad ng mga Pilipino.

Para po mas maintindihan ng mamamayan ang bagong batas, bibigyan ko po kayo ng mga halimbawa ng mga malalagim na kaganapan sa bansa na kagagawan ng mga terorista.

Isa na rito ang Marawi Siege kung saan sinakop ng mga terorista ang maunlad na lungsod ng Marawi, at winasak ang buong siyudad kasabay ang pagwasak sa buhay at ari-arian ng libo-libong mamamayan nito. Daan-daang sundalo at sibilyan ang nagbuwis ng buhay dahil sa kagagawang ito ng mga terorista.

Sa lungsod po ni Pangulong Duterte sa Davao City, ilang mga pag-atake po ang ginawa ng mga terorista na nagresulta sa pagkamatay ng maraming sibilyan. Kabilang na po dito ang pambobomba sa Davao airport noong 2003, pagpapasabog sa St. Peter’s Cathedral, pagpapasabog sa Sasa Wharf at noong 2016 bago pa lamang nakakaupo si Pangulong Duterte ay inatake ng mga terorista ang Night Market sa Davao City.

Bukod pa ito sa mga insidente ng karahasan at suicide bombing sa mga lugar ng Basilan, Sulu at Tawi Tawi.

Bakit ko po inisa-isa ang mga insidenteng ito? Para po malaman ng mga tao kung gaano kalala ang pinsalang dinulot ng mga terorista sa buhay ng mga pamilyang nawalan ng mahal sa buhay dahil sa kanilang mga ginagawa.