- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Personal Finance

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- March Madness

- AP Top 25 Poll

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Personal finance

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

Trans kids’ treatment can start younger, new guidelines say

This photo provided by Laura Short shows Eli Bundy on April 15, 2022 at Deception Pass in Washington. In South Carolina, where a proposed law would ban transgender treatments for kids under age 18, Eli Bundy hopes to get breast removal surgery next year before college. Bundy, 18, who identifies as nonbinary, supports updated guidance from an international transgender health group that recommends lower ages for some treatments. (Laura Short via AP)

FILE - Dr. David Klein, right, an Air Force Major and chief of adolescent medicine at Fort Belvoir Community Hospital, listens as Amanda Brewer, left, speaks with her daughter, Jenn Brewer, 13, as the teenager has blood drawn during a monthly appointment for monitoring her treatment at the hospital in Fort Belvoir, Va., on Sept. 7, 2016. Brewer is transitioning from male to female. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin, File)

- Copy Link copied

A leading transgender health association has lowered its recommended minimum age for starting gender transition treatment, including sex hormones and surgeries.

The World Professional Association for Transgender Health said hormones could be started at age 14, two years earlier than the group’s previous advice, and some surgeries done at age 15 or 17, a year or so earlier than previous guidance. The group acknowledged potential risks but said it is unethical and harmful to withhold early treatment.

The association provided The Associated Press with an advance copy of its update ahead of publication in a medical journal, expected later this year. The international group promotes evidence-based standards of care and includes more than 3,000 doctors, social scientists and others involved in transgender health issues.

The update is based on expert opinion and a review of scientific evidence on the benefits and harms of transgender medical treatment in teens whose gender identity doesn’t match the sex they were assigned at birth, the group said. Such evidence is limited but has grown in the last decade, the group said, with studies suggesting the treatments can improve psychological well-being and reduce suicidal behavior.

Starting treatment earlier allows transgender teens to experience physical puberty changes around the same time as other teens, said Dr. Eli Coleman, chair of the group’s standards of care and director of the University of Minnesota Medical School’s human sexuality program.

But he stressed that age is just one factor to be weighed. Emotional maturity, parents’ consent, longstanding gender discomfort and a careful psychological evaluation are among the others.

“Certainly there are adolescents that do not have the emotional or cognitive maturity to make an informed decision,” he said. “That is why we recommend a careful multidisciplinary assessment.”

The updated guidelines include recommendations for treatment in adults, but the teen guidance is bound to get more attention. It comes amid a surge in kids referred to clinics offering transgender medical treatment , along with new efforts to prevent or restrict the treatment.

Many experts say more kids are seeking such treatment because gender-questioning children are more aware of their medical options and facing less stigma.

Critics, including some from within the transgender treatment community, say some clinics are too quick to offer irreversible treatment to kids who would otherwise outgrow their gender-questioning.

Psychologist Erica Anderson resigned her post as a board member of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health last year after voicing concerns about “sloppy” treatment given to kids without adequate counseling.

She is still a group member and supports the updated guidelines, which emphasize comprehensive assessments before treatment. But she says dozens of families have told her that doesn’t always happen.

“They tell me horror stories. They tell me, ‘Our child had 20 minutes with the doctor’” before being offered hormones, she said. “The parents leave with their hair on fire.’’

Estimates on the number of transgender youth and adults worldwide vary, partly because of different definitions. The association’s new guidelines say data from mostly Western countries suggest a range of between a fraction of a percent in adults to up to 8% in kids.

Anderson said she’s heard recent estimates suggesting the rate in kids is as high as 1 in 5 — which she strongly disputes. That number likely reflects gender-questioning kids who aren’t good candidates for lifelong medical treatment or permanent physical changes, she said.

Still, Anderson said she condemns politicians who want to punish parents for allowing their kids to receive transgender treatment and those who say treatment should be banned for those under age 18.

“That’s just absolutely cruel,’’ she said.

Dr. Marci Bowers, the transgender health group’s president-elect, also has raised concerns about hasty treatment, but she acknowledged the frustration of people who have been “forced to jump through arbitrary hoops and barriers to treatment by gatekeepers ... and subjected to scrutiny that is not applied to another medical diagnosis.’’

Gabe Poulos, 22, had breast removal surgery at age 16 and has been on sex hormones for seven years. The Asheville, North Carolina, resident struggled miserably with gender discomfort before his treatment.

Poulos said he’s glad he was able to get treatment at a young age.

“Transitioning under the roof with your parents so they can go through it with you, that’s really beneficial,’’ he said. “I’m so much happier now.’’

In South Carolina, where a proposed law would ban transgender treatments for kids under age 18, Eli Bundy has been waiting to get breast removal surgery since age 15. Now 18, Bundy just graduated from high school and is planning to have surgery before college.

Bundy, who identifies as nonbinary, supports easing limits on transgender medical care for kids.

“Those decisions are best made by patients and patient families and medical professionals,’’ they said. “It definitely makes sense for there to be fewer restrictions, because then kids and physicians can figure it out together.’’

Dr. Julia Mason, an Oregon pediatrician who has raised concerns about the increasing numbers of youngsters who are getting transgender treatment, said too many in the field are jumping the gun. She argues there isn’t strong evidence in favor of transgender medical treatment for kids.

“In medicine ... the treatment has to be proven safe and effective before we can start recommending it,’’ Mason said.

Experts say the most rigorous research — studies comparing treated kids with outcomes in untreated kids — would be unethical and psychologically harmful to the untreated group.

The new guidelines include starting medication called puberty blockers in the early stages of puberty, which for girls is around ages 8 to 13 and typically two years later for boys. That’s no change from the group’s previous guidance. The drugs delay puberty and give kids time to decide about additional treatment; their effects end when the medication is stopped.

The blockers can weaken bones, and starting them too young in children assigned males at birth might impair sexual function in adulthood, although long-term evidence is lacking.

The update also recommends:

—Sex hormones — estrogen or testosterone — starting at age 14. This is often lifelong treatment. Long-term risks may include infertility and weight gain, along with strokes in trans women and high blood pressure in trans men, the guidelines say.

—Breast removal for trans boys at age 15. Previous guidance suggested this could be done at least a year after hormones, around age 17, although a specific minimum ag wasn’t listed.

—Most genital surgeries starting at age 17, including womb and testicle removal, a year earlier than previous guidance.

The Endocrine Society, another group that offers guidance on transgender treatment, generally recommends starting a year or two later, although it recently moved to start updating its own guidelines. The American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Medical Association support allowing kids to seek transgender medical treatment, but they don’t offer age-specific guidance.

Dr. Joel Frader, a Northwestern University a pediatrician and medical ethicist who advises a gender treatment program at Chicago’s Lurie Children’s Hospital, said guidelines should rely on psychological readiness, not age.

Frader said brain science shows that kids are able to make logical decisions by around age 14, but they’re prone to risk-taking and they take into account long-term consequences of their actions only when they’re much older.

Coleen Williams, a psychologist at Boston Children’s Hospital’s Gender Multispecialty Service, said treatment decisions there are collaborative and individualized.

“Medical intervention in any realm is not a one-size-fits-all option,” Williams said.

Follow AP Medical Writer Lindsey Tanner at @LindseyTanner.

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Young Children Do Not Receive Medical Gender Transition Treatment

By Kate Yandell

Posted on May 22, 2023

SciCheck Digest

Families seeking information from a health care provider about a young child’s gender identity may have their questions answered or receive counseling. Some posts share a misleading claim that toddlers are being “transitioned.” To be clear, prepubescent children are not offered transition surgery or drugs.

Some children identify with a gender that does not match their sex assigned at birth. These children are referred to as transgender, gender-diverse or gender-expansive. Doctors will listen to children and their family members, offer information, and in some cases connect them with mental health care, if needed.

But for children who have not yet started puberty, there are no recommended drugs, surgeries or other gender-transition treatments.

Recent social media posts shared the misleading claim that medical institutions in North Carolina are “transitioning toddlers,” which they called an “experimental treatment.” The posts referenced a blog post published by the Education First Alliance, a conservative nonprofit in North Carolina that says many schools are engaging in “ideological indoctrination” of children and need to be reformed.

The group has advocated the passage of a North Carolina bill to restrict medical gender-transition treatment before age 18. There are now 18 states that have taken action to restrict medical transition treatments for minors .

A widely shared article from the Epoch Times citing the blog post bore the false headline: “‘Transgender’ Toddlers as Young as 2 Undergoing Mutilation/Sterilization by NC Medical System, Journalist Alleges.” The Epoch Times has a history of publishing misleading or false claims. The article on transgender toddlers then disappeared from the website, and the Epoch Times published a new article clarifying that young children are not receiving hormone blockers, cross-sex hormones or surgery.

Representatives from all three North Carolina institutions referenced in the social media posts told us via emailed statements that they do not offer surgeries or other transition treatments to toddlers.

East Carolina University, May 5: ECU Health does not offer gender affirming surgery to minors nor does the health system offer gender affirming transition care to toddlers.

ECU Health elaborated that it does not offer puberty blockers and only offers hormone therapy after puberty “in limited cases,” as recommended in national guidelines and with parental or guardian consent. It also said that it offers interdisciplinary gender-affirming primary care for LGBTQ+ patients, including access to services such as mental health care, nutrition and social work.

“These primary care services are available to any LGBTQ+ patient who needs care. ECU Health does not provide gender-related care to patients 2 to 4 years old or any toddler period,” ECU said.

University of North Carolina, May 12: To be clear: UNC Health does not offer any gender-transitioning care for toddlers. We do not perform any gender care surgical procedures or medical interventions on toddlers. Also, we are not conducting any gender care research or clinical trials involving children. If a toddler’s parent(s) has concerns or questions about their child’s gender, a primary care provider would certainly listen to them, but would never recommend gender treatment for a toddler. Gender surgery can be performed on anyone 18 years old or older .

Duke Health, May 12: Duke Health has provided high-quality, compassionate, and evidence-based gender care to both adolescents and adults for many years. Care decisions are made by patients, families and their providers and are both age-appropriate and adherent to national and international guidelines. Under these professional guidelines and in accordance with accepted medical standards, hormone therapies are explicitly not provided to children prior to puberty and gender-affirming surgeries are, except in exceedingly rare circumstances, only performed after age 18.

Duke and UNC both called the claims that they offer gender-transition care to toddlers false, and ECU referred to the “intentional spreading of dangerous misinformation online.”

Nor do other medical institutions offer gender-affirming drug treatment or surgery to toddlers, clinical psychologist Christy Olezeski , director of the Yale Pediatric Gender Program, told us, although some may offer support to families of young children or connect them with mental health care.

The Education First Alliance post also states that a doctor “can see a 2-year-old girl play with a toy truck, and then begin treatment for gender dysphoria.” But simply playing with a certain toy would not meet the criteria for a diagnosis of gender dysphoria, according to the medical diagnostic manual used by health professionals.

“With all kids, we want them to feel comfortable and confident in who they are. We want them to feel comfortable and confident in how they like to express themselves. We want them to be safe,” Olezeski said. “So all of these tenets are taken into consideration when providing care for children. There is no medical care that happens prior to puberty.”

Medical Transition Starts During Adolescence or Later

The Education First Alliance blog post does not clearly state what it means when it says North Carolina institutions are “transitioning toddlers.” It refers to treatment and hormone therapy without clarifying the age at which it is offered.

Only in the final section of the piece does it include a quote from a doctor correctly stating that children are not offered surgery or drugs before puberty.

To spell out the reality of the situation: The North Carolina institutions are not providing surgeries or hormone therapy to prepubescent children, nor is this standard practice in any part of the country.

Programs and physicians will have different policies, but widely referenced guidance from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health and the Endocrine Society lays out recommended care at different ages.

Drugs that suppress puberty are the first medical treatment that may be offered to a transgender minor, the guidelines say. Children may be offered drugs to suppress puberty beginning when breast buds appear or testicles increase to a certain volume, typically happening between ages 8 to 13 or 9 to 14, respectively.

Generally, someone may start gender-affirming hormone therapy in early adolescence or later, the American Academy for Pediatrics explains . The Endocrine Society says that adolescents typically have the mental capacity to participate in making an informed decision about gender-affirming hormone therapy by age 16.

Older adolescents who want flat chests may sometimes be able to get surgery to remove their breasts, also known as top surgery, Olezeski said. They sometimes desire to do this before college. Guidelines do not offer a specific age during adolescence when this type of surgery may be appropriate. Instead, they explain how a care team can assess adolescents on a case-by-case basis.

A previous version of the WPATH guidelines did not recommend genital surgery until adulthood, but the most recent version, published in September 2022, is less specific about an age limit. Rather, it explains various criteria to determine whether someone who desires surgery should be offered it, including a person’s emotional and cognitive maturity level and whether they have been on hormone therapy for at least a year.

The Endocrine Society similarly offers criteria for when someone might be ready for genital surgery, but specifies that surgeries involving removing the testicles, ovaries or uterus should not happen before age 18.

“Typically any sort of genital-affirming surgeries still are happening at 18 or later,” Olezeski said.

There are no comprehensive statistics on the number of gender-affirming surgeries performed in the U.S., but according to an insurance claims analysis from Reuters and Komodo Health Inc., 776 minors with a diagnosis of gender dysphoria had breast removal surgeries and 56 had genital surgeries from 2019 to 2021.

Research Shows Benefits of Affirming Gender Identity

Young children do not get medical transition treatment, but they do have feelings about their gender and can benefit from support from those around them. “Children start to have a sense of their own gender identity between the ages of 2 1/2 to 3 years old,” Olezeski said.

Programs vary in what age groups they serve, she said, but some do support families of preschool-aged children by answering questions or providing mental health care.

Transgender children are at increased risk of some mental health problems, including anxiety and depression. According to the WPATH guidelines, affirming a child’s gender through day-to-day changes — also known as social transition — may have a positive impact on a child’s mental health. Social transition “may look different for every individual,” Olezeski said. Changes could include going by a different name or pronouns or altering one’s attire or hair style.

Two studies of socially transitioned children — including one with kids as young as 3 — have found minimal or no difference in anxiety and depression compared with non-transgender siblings or other children of similar ages.

“Research substantiates that children who are prepubertal and assert an identity of [transgender and gender diverse] know their gender as clearly and as consistently as their developmentally equivalent peers who identify as cisgender and benefit from the same level of social acceptance,” the AAP guidelines say, adding that differences in how children identify and express their gender are normal.

Social transitions largely take place outside of medical institutions, led by the child and supported by their family members and others around them. However, a family with questions about their child’s gender or social transition may be able to get information from their pediatrician or another medical provider, Olezeski said.

Although not available everywhere, specialized programs may be particularly prepared to offer care to a gender-diverse child and their family, she said. A child may get a referral to one of these programs from a pediatrician, another specialty physician, a mental health care professional or their school, or a parent may seek out one of these programs.

“We have created a space where parents can come with their youth when they’re young to ask questions about how to best support their child: what to do if they have questions, how to get support, what do we know about the best research in terms of how to allow kids space to explore their identity, to explore how they like to express themselves, and then if they do identify as trans or nonbinary, how to support the parents and the youth in that,” Olezeski said of specialized programs. Parents benefit from the support, and then the children also benefit from support from their parents.

WPATH says that the child should be the one to initiate a social transition by expressing a “strong desire or need” for it after consistently articulating an identity that does not match their sex assigned at birth. A health care provider can then help the family explore benefits and risks. A child simply playing with certain toys, dressing a certain way or enjoying certain activities is not a sign they would benefit from a social transition, the guidelines state.

Previously, assertions children made about their gender were seen as “possibly true” and support was often withheld until an age when identity was believed to become fixed, the AAP guidelines explain. But “more robust and current research suggests that, rather than focusing on who a child will become, valuing them for who they are, even at a young age, fosters secure attachment and resilience, not only for the child but also for the whole family,” the guidelines say.

Mental Health Care Benefits

A gender-diverse child or their family members may benefit from a referral to a psychologist or other mental health professional. However, being transgender or gender-diverse is not in itself a mental health disorder, according to the American Psychological Association , WPATH and other expert groups . These organizations also note that people who are transgender or gender-diverse do not all experience mental health problems or distress about their gender.

Psychological therapy is not meant to change a child’s gender identity, the WPATH guidelines say .

The form of therapy a child or a family might receive will depend on their particular needs, Olezeski said. For instance, a young child might receive play-based therapy, since play is how children “work out different things in their life,” she said. A parent might work on strategies to better support their child.

One mental health diagnosis that some gender-diverse people may receive is gender dysphoria . There is disagreement about how useful such a diagnosis is, and receiving such a diagnosis does not necessarily mean someone will decide to undergo a transition, whether social or medical.

UNC Health told us in an email that a gender dysphoria diagnosis “is rarely used” for children.

Very few gender-expansive kids have dysphoria, the spokesperson said. “ Gender expansion in childhood is not Gender Dysphoria ,” UNC added, attributing the explanation to psychiatric staff (emphasis is UNC’s). “The psychiatric team’s goal is to provide good mental health care and manage safety—this means trying to protect against abuse and bullying and to support families.”

Social media posts incorrectly claim that toddlers are being diagnosed with gender dysphoria based on what toys they play with. One post said : “Three medical schools in North Carolina are diagnosing TODDLERS who play with stereotypically opposite gender toys as having GENDER DYSPHORIA and are beginning to transition them!!”

There are separate criteria for diagnosing gender dysphoria in adults and adolescents versus children, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. For children to receive this diagnosis, they must meet six of eight criteria for a six-month period and experience “clinically significant distress” or impairment in functioning, according to the diagnostic manual.

A “strong preference for the toys, games or activities stereotypically used or engaged in by the other gender” is one criterion, but children must also meet other criteria, and expressing a strong desire to be another gender or insisting that they are another gender is required.

“People liking to play with different things or liking to wear a diverse set of clothes does not mean that somebody has gender dysphoria,” Olezeski said. “That just means that kids have a breadth of things that they can play with and ways that they can act and things that they can wear . ”

Editor’s note: SciCheck’s articles providing accurate health information and correcting health misinformation are made possible by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The foundation has no control over FactCheck.org’s editorial decisions, and the views expressed in our articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the foundation.

Rafferty, Jason. “ Gender-Diverse & Transgender Children .” HealthyChildren.org. Updated 8 Jun 2022.

Coleman, E. et al. “ Standards of Care for the Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse People, Version 8 .” International Journal of Transgender Health. 15 Sep 2022.

Rachmuth, Sloan. “ Transgender Toddlers Treated at Duke, UNC, and ECU .” Education First Alliance. 1 May 2023.

North Carolina General Assembly. “ Senate Bill 639, Youth Health Protection Act .” (as introduced 5 Apr 2023).

Putka, Sophie et al. “ These States Have Banned Youth Gender-Affirming Care .” Medpage Today. Updated 17 May 2023.

Davis, Elliott Jr. “ States That Have Restricted Gender-Affirming Care for Trans Youth in 2023 .” U.S. News & World Report. Updated 17 May 2023.

Montgomery, David and Goodman, J. David. “ Texas Legislature Bans Transgender Medical Care for Children .” New York Times. 17 May 2023.

Ji, Sayer. ‘ Transgender’ Toddlers as Young as 2 Undergoing Mutilation/Sterilization by NC Medical System, Journalist Alleges .” Epoch Times. Internet Archive, Wayback Machine. Archived 6 May 2023.

McDonald, Jessica. “ COVID-19 Vaccines Reduce, Not Increase, Risk of Stillbirth .” FactCheck.org. 9 Nov 2022.

Jaramillo, Catalina. “ Posts Distort Questionable Study on COVID-19 Vaccination and EMS Calls .” FactCheck.org. 15 June 2022.

Spencer, Saranac Hale. “ Social Media Posts Misrepresent FDA’s COVID-19 Vaccine Safety Research .” FactCheck.org. 23 Dec 2022.

Jaramillo, Catalina. “ WHO ‘Pandemic Treaty’ Draft Reaffirms Nations’ Sovereignty to Dictate Health Policy .” FactCheck.org. 2 Mar 2023.

McCormick Sanchez, Darlene. “ IN-DEPTH: North Carolina Medical Schools See Children as Young as Toddlers for Gender Dysphoria .” The Epoch Times. 8 May 2023.

ECU health spokesperson. Emails with FactCheck.org. 12 May 2023 and 19 May 2023.

UNC Health spokesperson. Emails with FactCheck.org. 12 May 2023 and 19 May 2023.

Duke Health spokesperson. Email with FactCheck.org. 12 May 2023.

Olezeski, Christy. Interview with FactCheck.org. 16 May 2023.

Hembree, Wylie C. et al. “ Endocrine Treatment of Gender-Dysphoric/Gender-Incongruent Persons: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline .” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1 Nov 2017.

Emmanuel, Mickey and Bokor, Brooke R. “ Tanner Stages .” StatPearls. Updated 11 Dec 2022.

Rafferty, Jason et al. “ Ensuring Comprehensive Care and Support for Transgender and Gender-Diverse Children and Adolescents .” Pediatrics. 17 Sep 2018.

Coleman, E. et al. “ Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender-Nonconforming People, Version 7 .” International Journal of Transgenderism. 27 Aug 2012.

Durwood, Lily et al. “ Mental Health and Self-Worth in Socially Transitioned Transgender Youth .” Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 27 Nov 2016.

Olson, Kristina R. et al. “ Mental Health of Transgender Children Who Are Supported in Their Identities .” Pediatrics. 26 Feb 2016.

“ Answers to Your Questions about Transgender People, Gender Identity, and Gender Expression .” American Psychological Association website. 9 Mar 2023.

“ What is Gender Dysphoria ?” American Psychiatric Association website. Updated Aug 2022.

Vanessa Marie | Truth Seeker (indivisible.mama). “ Three medical schools in North Carolina are diagnosing TODDLERS who play with stereotypically opposite gender toys as having GENDER DYSPHORIA and are beginning to transition them!! … ” Instagram. 7 May 2023.

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Tests & Procedures

- Feminizing hormone therapy

Feminizing hormone therapy typically is used by transgender women and nonbinary people to produce physical changes in the body that are caused by female hormones during puberty. Those changes are called secondary sex characteristics. This hormone therapy helps better align the body with a person's gender identity. Feminizing hormone therapy also is called gender-affirming hormone therapy.

Feminizing hormone therapy involves taking medicine to block the action of the hormone testosterone. It also includes taking the hormone estrogen. Estrogen lowers the amount of testosterone the body makes. It also triggers the development of feminine secondary sex characteristics. Feminizing hormone therapy can be done alone or along with feminizing surgery.

Not everybody chooses to have feminizing hormone therapy. It can affect fertility and sexual function, and it might lead to health problems. Talk with your health care provider about the risks and benefits for you.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Available Sexual Health Solutions at Mayo Clinic Store

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

Why it's done

Feminizing hormone therapy is used to change the body's hormone levels. Those hormone changes trigger physical changes that help better align the body with a person's gender identity.

In some cases, people seeking feminizing hormone therapy experience discomfort or distress because their gender identity differs from their sex assigned at birth or from their sex-related physical characteristics. This condition is called gender dysphoria.

Feminizing hormone therapy can:

- Improve psychological and social well-being.

- Ease psychological and emotional distress related to gender.

- Improve satisfaction with sex.

- Improve quality of life.

Your health care provider might advise against feminizing hormone therapy if you:

- Have a hormone-sensitive cancer, such as prostate cancer.

- Have problems with blood clots, such as when a blood clot forms in a deep vein, a condition called deep vein thrombosis, or a there's a blockage in one of the pulmonary arteries of the lungs, called a pulmonary embolism.

- Have significant medical conditions that haven't been addressed.

- Have behavioral health conditions that haven't been addressed.

- Have a condition that limits your ability to give your informed consent.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

Stay Informed with LGBTQ+ health content.

Receive trusted health information and answers to your questions about sexual orientation, gender identity, transition, self-expression, and LGBTQ+ health topics. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing to our LGBTQ+ newsletter.

You will receive the first newsletter in your inbox shortly. This will include exclusive health content about the LGBTQ+ community from Mayo Clinic.

If you don't receive our email within 5 minutes, check your SPAM folder, then contact us at [email protected] .

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

Research has found that feminizing hormone therapy can be safe and effective when delivered by a health care provider with expertise in transgender care. Talk to your health care provider about questions or concerns you have regarding the changes that will happen in your body as a result of feminizing hormone therapy.

Complications can include:

- Blood clots in a deep vein or in the lungs

- Heart problems

- High levels of triglycerides, a type of fat, in the blood

- High levels of potassium in the blood

- High levels of the hormone prolactin in the blood

- Nipple discharge

- Weight gain

- Infertility

- High blood pressure

- Type 2 diabetes

Evidence suggests that people who take feminizing hormone therapy may have an increased risk of breast cancer when compared to cisgender men — men whose gender identity aligns with societal norms related to their sex assigned at birth. But the risk is not greater than that of cisgender women.

To minimize risk, the goal for people taking feminizing hormone therapy is to keep hormone levels in the range that's typical for cisgender women.

Feminizing hormone therapy might limit your fertility. If possible, it's best to make decisions about fertility before starting treatment. The risk of permanent infertility increases with long-term use of hormones. That is particularly true for those who start hormone therapy before puberty begins. Even after stopping hormone therapy, your testicles might not recover enough to ensure conception without infertility treatment.

If you want to have biological children, talk to your health care provider about freezing your sperm before you start feminizing hormone therapy. That procedure is called sperm cryopreservation.

How you prepare

Before you start feminizing hormone therapy, your health care provider assesses your health. This helps address any medical conditions that might affect your treatment. The evaluation may include:

- A review of your personal and family medical history.

- A physical exam.

- A review of your vaccinations.

- Screening tests for some conditions and diseases.

- Identification and management, if needed, of tobacco use, drug use, alcohol use disorder, HIV or other sexually transmitted infections.

- Discussion about sperm freezing and fertility.

You also might have a behavioral health evaluation by a provider with expertise in transgender health. The evaluation may assess:

- Gender identity.

- Gender dysphoria.

- Mental health concerns.

- Sexual health concerns.

- The impact of gender identity at work, at school, at home and in social settings.

- Risky behaviors, such as substance use or use of unapproved silicone injections, hormone therapy or supplements.

- Support from family, friends and caregivers.

- Your goals and expectations of treatment.

- Care planning and follow-up care.

People younger than age 18, along with a parent or guardian, should see a medical care provider and a behavioral health provider with expertise in pediatric transgender health to discuss the risks and benefits of hormone therapy and gender transitioning in that age group.

What you can expect

You should start feminizing hormone therapy only after you've had a discussion of the risks and benefits as well as treatment alternatives with a health care provider who has expertise in transgender care. Make sure you understand what will happen and get answers to any questions you may have before you begin hormone therapy.

Feminizing hormone therapy typically begins by taking the medicine spironolactone (Aldactone). It blocks male sex hormone receptors — also called androgen receptors. This lowers the amount of testosterone the body makes.

About 4 to 8 weeks after you start taking spironolactone, you begin taking estrogen. This also lowers the amount of testosterone the body makes. And it triggers physical changes in the body that are caused by female hormones during puberty.

Estrogen can be taken several ways. They include a pill and a shot. There also are several forms of estrogen that are applied to the skin, including a cream, gel, spray and patch.

It is best not to take estrogen as a pill if you have a personal or family history of blood clots in a deep vein or in the lungs, a condition called venous thrombosis.

Another choice for feminizing hormone therapy is to take gonadotropin-releasing hormone (Gn-RH) analogs. They lower the amount of testosterone your body makes and might allow you to take lower doses of estrogen without the use of spironolactone. The disadvantage is that Gn-RH analogs usually are more expensive.

After you begin feminizing hormone therapy, you'll notice the following changes in your body over time:

- Fewer erections and a decrease in ejaculation. This will begin 1 to 3 months after treatment starts. The full effect will happen within 3 to 6 months.

- Less interest in sex. This also is called decreased libido. It will begin 1 to 3 months after you start treatment. You'll see the full effect within 1 to 2 years.

- Slower scalp hair loss. This will begin 1 to 3 months after treatment begins. The full effect will happen within 1 to 2 years.

- Breast development. This begins 3 to 6 months after treatment starts. The full effect happens within 2 to 3 years.

- Softer, less oily skin. This will begin 3 to 6 months after treatment starts. That's also when the full effect will happen.

- Smaller testicles. This also is called testicular atrophy. It begins 3 to 6 months after the start of treatment. You'll see the full effect within 2 to 3 years.

- Less muscle mass. This will begin 3 to 6 months after treatment starts. You'll see the full effect within 1 to 2 years.

- More body fat. This will begin 3 to 6 months after treatment starts. The full effect will happen within 2 to 5 years.

- Less facial and body hair growth. This will begin 6 to 12 months after treatment starts. The full effect happens within three years.

Some of the physical changes caused by feminizing hormone therapy can be reversed if you stop taking it. Others, such as breast development, cannot be reversed.

While on feminizing hormone therapy, you meet regularly with your health care provider to:

- Keep track of your physical changes.

- Monitor your hormone levels. Over time, your hormone dose may need to change to ensure you are taking the lowest dose necessary to get the physical effects that you want.

- Have blood tests to check for changes in your cholesterol, blood sugar, blood count, liver enzymes and electrolytes that could be caused by hormone therapy.

- Monitor your behavioral health.

You also need routine preventive care. Depending on your situation, this may include:

- Breast cancer screening. This should be done according to breast cancer screening recommendations for cisgender women your age.

- Prostate cancer screening. This should be done according to prostate cancer screening recommendations for cisgender men your age.

- Monitoring bone health. You should have bone density assessment according to the recommendations for cisgender women your age. You may need to take calcium and vitamin D supplements for bone health.

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies of tests and procedures to help prevent, detect, treat or manage conditions.

Feminizing hormone therapy care at Mayo Clinic

- Tangpricha V, et al. Transgender women: Evaluation and management. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Oct. 10, 2022.

- Erickson-Schroth L, ed. Medical transition. In: Trans Bodies, Trans Selves: A Resource by and for Transgender Communities. 2nd ed. Kindle edition. Oxford University Press; 2022. Accessed Oct. 10, 2022.

- Coleman E, et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. International Journal of Transgender Health. 2022; doi:10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644.

- AskMayoExpert. Gender-affirming hormone therapy (adult). Mayo Clinic; 2022.

- Nippoldt TB (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. Sept. 29, 2022.

- Gender dysphoria

- Doctors & Departments

- Care at Mayo Clinic

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Let’s celebrate our doctors!

Join us in celebrating and honoring Mayo Clinic physicians on March 30th for National Doctor’s Day.

May 12, 2022

What the Science on Gender-Affirming Care for Transgender Kids Really Shows

Laws that ban gender-affirming treatment ignore the wealth of research demonstrating its benefits for trans people’s health

By Heather Boerner

As attacks against transgender kids increase in the U.S., Minnesotans hold a rally at the state’s capitol in Saint Paul in March 2022 to support trans kids in Minnesota and Texas and around the country.

Michael Siluk/UCG/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Editor’s Note (3/30/23): This article from May 2022 is being republished to highlight the ways that ongoing anti-trans legislation is harmful and unscientific.

For the first 40 years of their life, Texas resident Kelly Fleming spent a portion of most years in a deep depression. As an adult, Fleming—who uses they/them pronouns and who asked to use a pseudonym to protect their safety—would shave their face in the shower with the lights off so neither they nor their wife would have to confront the reality of their body.

What Fleming was experiencing, although they did not know it at the time, was gender dysphoria : the acute and chronic distress of living in a body that does not reflect one’s gender and the desire to have bodily characteristics of that gender. While in therapy, Fleming discovered research linking access to gender-affirming hormone therapy with reduced depression in transgender people. They started a very low dose of estradiol, and the depression episodes became shorter, less frequent and less intense. Now they look at their body with joy.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

So when Fleming sees what authorities in Texas , Alabama , Florida and other states are doing to bar transgender teens and children from receiving gender-affirming medical care, it infuriates them. And they are worried for their children, ages 12 and 14, both of whom are agender—a identity on the transgender spectrum that is neither masculine nor feminine.

“I’m just so excited to see them being able to present themselves in a way that makes them happy,” Fleming says. “They are living their best life regardless of what others think, and that’s a privilege that I did not get to have as a younger person.”

Laws Based on “Completely Wrong” Information

Currently more than a dozen state legislatures or administrations are considering—or have already passed—laws banning health care for transgender young people. On April 20 the Florida Department of Health issued guidance to withhold such gender-affirming care. This includes social gender transitioning—acknowledging that a young person is trans, using their correct pronouns and name, and supporting their desire to live publicly as the gender of their experience rather than their sex assigned at birth. This comes nearly two months after Texas Governor Greg Abbott issued an order for the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services to investigate for child abuse parents who allow their transgender preteens and teenagers to receive medical care. Alabama recently passed SB 184 , which would make it a felony to provide gender-affirming medical care to transgender minors. In Alabama, a “minor” is defined as anyone 19 or younger.

If such laws go ahead, 58,200 teens in the U.S. could lose access to or never receive gender-affirming care, according to the Williams Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles. A decade of research shows such treatment reduces depression, suicidality and other devastating consequences of trans preteens and teens being forced to undergo puberty in the sex they were assigned at birth).

The bills are based on “information that’s completely wrong,” says Michelle Forcier, a pediatrician and professor of pediatrics at Brown University. Forcier literally helped write the book on how to provide evidence-based gender care to young people. She is also an assistant dean of admissions at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University. Those laws “are absolutely, absolutely incorrect” about the science of gender-affirming care for young people, she says. “[Inaccurate information] is there to create drama. It’s there to make people take a side.”

The truth is that data from more than a dozen studies of more than 30,000 transgender and gender-diverse young people consistently show that access to gender-affirming care is associated with better mental health outcomes—and that lack of access to such care is associated with higher rates of suicidality, depression and self-harming behavior. (Gender diversity refers to the extent to which a person’s gendered behaviors, appearance and identities are culturally incongruent with the sex they were assigned at birth. Gender-diverse people can identify along the transgender spectrum, but not all do.) Major medical organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) , the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry , the Endocrine Society , the American Medical Association , the American Psychological Association and the American Psychiatric Association , have published policy statements and guidelines on how to provide age-appropriate gender-affirming care. All of those medical societies find such care to be evidence-based and medically necessary.

AAP and Endocrine Society guidelines call for developmentally appropriate care, and that means no puberty blockers or hormones until young people are already undergoing puberty for their sex assigned at birth. For one thing, “there are no hormonal differences among prepubertal children,” says Joshua Safer, executive director of the Mount Sinai Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery in New York City and co-author of the Endocrine Society’s guidelines. Those guidelines provide the option of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues (GnRHas), which block the release of sex hormones, once young people are already into the second of five puberty stages—marked by breast budding and pubic hair. These are offered only if a teen is not ready to make decisions about puberty. Access to gender-affirming hormones and potential access to gender-affirming surgery is available at age 16—and then, in the case of transmasculine youth, only mastectomy, also known as top surgery. The Endocrine Society does not recommend genital surgery for minors.

Before puberty, gender-affirming care is about supporting the process of gender development rather than directing children through a specific course of gender transition or maintenance of cisgender presentation, says Jason Rafferty, co-author of AAP’s policy statement on gender-affirming care and a pediatrician and psychiatrist at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Rhode Island. “The current research suggests that, rather than predicting or preventing who a child might become, it’s better to value them for who they are now—even at a young age,” Rafferty says.

A Safe Environment to Explore Gender

A 2021 systematic review of 44 peer-reviewed studies found that parent connectedness, measured by a six-question scale asking about such things as how safe young people feel confiding in their guardians or how cared for they feel in the family, is associated with greater resilience among teens and young adults who are transgender or gender-diverse. Rafferty says he sees his role with regard to prepubertal children as offering a safe environment for the child to explore their gender and for parents to ask questions. “The gender-affirming approach is not some railroad of people to hormones and surgery,” Safer says. “It is talking and watching and being conservative.”

Only once children are older, and if the incongruence between the sex assigned to them at birth and their experienced gender has persisted, does discussion of medical transition occur. First a gender therapist has to diagnose the young person with gender dysphoria .

After a gender dysphoria diagnosis—and only if earlier conversations suggest that hormones are indicated—guidelines call for discussion of fertility, puberty suppression and hormones. Puberty-suppressing medications have been used for decades for cisgender children who start puberty early, but they are not meant to be used indefinitely. The Endocrine Society guidelines recommend a maximum of two years on GnRHa therapy to allow more time for children to form their gender identity before undergoing puberty for their sex assigned at birth, the effects of which are irreversible.

“[Puberty blockers] are part of the process of ‘do no harm,’” Forcier says, referencing a popular phrase that describes the Hippocratic Oath, which many physicians recite a version of before they begin to practice.

Hormone blocker treatment may have side effects. A 2015 longitudinal observational cohort study of 34 transgender young people found that, by the time the participants were 22 years old, trans women experienced a decrease in bone mineral density. A 2020 study of puberty suppression in gender-diverse and transgender young people found that those who started puberty blockers in early puberty had lower bone mineral density before the start of treatment than the public at large. This suggests, the authors wrote, that GnRHa use may not be the cause of low bone mineral density for these young people. Instead they found that lack of exercise was a primary factor in low bone-mineral density, especially among transgender girls.

Other side effects of GnRHa therapy include weight gain, hot flashes and mood swings. But studies have found that these side effects—and puberty delay itself—are reversible , Safer says.

Gender-affirming hormone therapy often involves taking an androgen blocker (a chemical that blocks the release of testosterone and other androgenic hormones) and estrogen in transfeminine teens, and testosterone supplementation in transmasculine teens. Such hormones may be associated with some physiological changes for adult transgender people. For instance, transfeminine people taking estrogen see their so-called “good” cholesterol increase. By contrast, transmasculine people taking testosterone see their good cholesterol decrease. Some studies have hinted at effects on bone mineral density, but these are complicated and also depend on personal, family history, exercise, and many other factors in addition to hormones.”

And while some critics point to decade-old study and older studies suggesting very few young people persist in transgender identity into late adolescence and adulthood, Forcier says the data are “misleading and not accurate.” A recent review detailed methodological problems with some of these studies . New research in 17,151 people who had ever socially transitioned found that 86.9 percent persisted in their gender identity. Of the 2,242 people who reported that they reverted to living as the gender associated with the sex they were assigned at birth, just 15.9 percent said they did so because of internal factors such as questioning their experienced gender but also because of fear, mental health issues and suicide attempts. The rest reported the cause was social, economic and familial stigma and discrimination. A third reported that they ceased living openly as a trans person because doing so was “just too hard for me.”

The Harms of Denying Care

Data suggest the effects of denying that care are worse than whatever side effects result from delaying sex-assigned-at-birth puberty. And medical society guidelines conclude that the benefits of gender-affirming care outweigh the risks. Without gender-affirming hormone therapy, cisgender hormones take over, forcing body changes that can be permanent and distressing.

A 2020 study of 300 gender-incongruent young people found that mental distress—including self-harm, suicidal thoughts and depression— increased as the children were made to proceed with puberty according to their assigned sex. By the time 184 older teens (with a median age of 16) reached the stage in which transgender boys began their periods and grew breasts and transgender girls’ voice dropped and facial hair began to appear, 46 percent had been diagnosed with depression, 40 percent had self-harmed, 52 percent had considered suicide, and 17 percent had attempted it—rates significantly higher than those of gender-incongruent children who were a median of 13.9 years old or of cisgender kids their own age.

Conversely, access to gender-affirming hormones in adolescence appears to have a protective effect. In one study, researchers followed 104 teens and young adults for a year and asked them about their depression, anxiety and suicidality at the time they started receiving hormones or puberty blockers and again at the three-month, six-month and one-year mark. At the beginning of the study, which was published in JAMA Network Open in February 2022, more than half of the respondents reported moderate to severe depression, half reported moderate to severe anxiety, and 43.3 percent reported thoughts of self-harm or suicide in the past two weeks.

But when the researchers analyzed the results based on the kind of gender-affirming care the teens had received, they found that those who had access to puberty blockers or gender-affirming hormones were 60 percent less likely to experience moderate to severe depression. And those with access to the medical treatments were 73 percent less likely to contemplate self-harm or suicide.

“Delays in prescribing puberty blockers and hormones may in fact worsen mental health symptoms for trans youth,” says Diana Tordoff, an epidemiology graduate student at the University of Washington and co-author of the study.

That effect may be lifelong. A 2022 study of more than 21,000 transgender adults showed that just 41 percent of adults who wanted hormone therapy received it, and just 2.3 percent had access to it in adolescence. When researchers looked at rates of suicidal thinking over the past year in these same adults, they found that access to hormone therapy in early adolescence was associated with a 60 percent reduction in suicidality in the past year and that access in late adolescence was associated with a 50 percent reduction.

For Fleming’s kids in Texas, gender-affirming hormones are not currently part of the discussion; not all trans people desire hormones or surgery to feel affirmed in their gender. But Fleming is already looking at jobs in other states to protect their children’s access to such care, should they change their mind. “Getting your body closer to the gender [you] identify with—that is what helps the dysphoria,” Fleming says. “And not giving people the opportunity to do that, making it harder for them to do that, is what has made the suicide rate among transgender people so high. We just—trans people are just trying to survive.”

IF YOU NEED HELP If you or someone you know is struggling or having thoughts of suicide, help is available. Call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 (TALK), use the online Lifeline Chat or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741.

- Public Health

Gender Transition Medications and Surgeries for Children in the U.S.

Key takeaways.

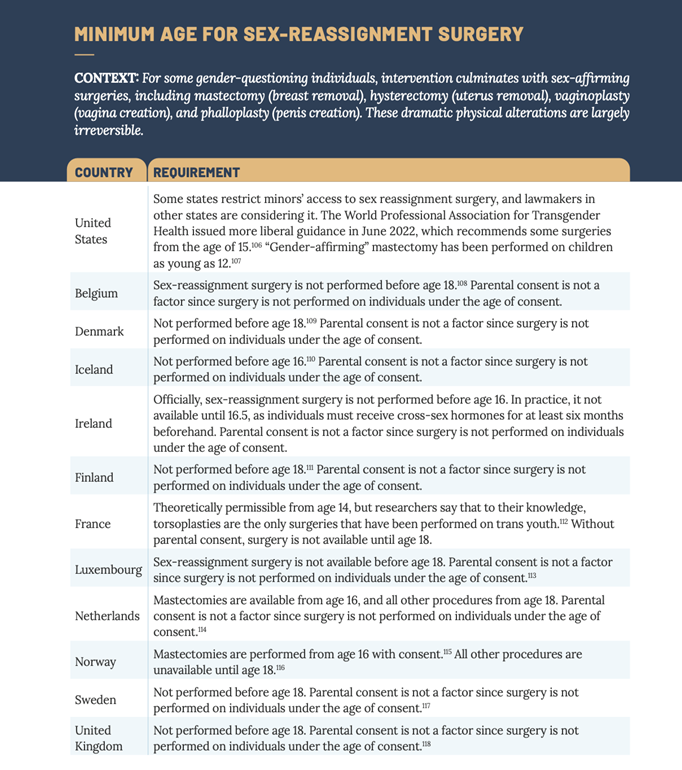

The U.S. currently has the most permissive laws surrounding transgender treatments for children compared to peer Western and Northern European nations.

Only 12–27% of children with gender dysphoria—a condition where one’s perceived gender identity differs from their biological sex—carry it into adulthood, yet many children in the U.S. are still eligible for irreversible therapies and surgeries.

Many puberty blockers given to children are prescribed for off-label (unapproved) use and can have dangerous side effects, including lowered bone density, stunted growth, and permanent infertility. There is limited research on the long-term effects of transgender interventions on children and little evidence of mental health benefits.

Policymakers should adopt policies to protect children from potentially harmful and irreversible sex reassignment surgeries and medications.

Executive Summary:

Rates of transgenderism in children have rapidly increased in recent years in the U.S., which has sparked discussions between parents, schools, policymakers, and medical professionals alike over how to discuss and treat the issue. On one end of the spectrum, activist groups and a vocal subset of the medical establishment have promoted what is euphemistically known as “gender-affirming care,” whereby children with transgender inclinations are being encouraged to undertake potentially irreversible surgical and hormonal interventions with unknown long-term consequences. The interventions range from preventing normal pubertal development to surgical procedures removing healthy breast tissue and genitalia. Recognizing the potential for significant harm, and with over 300,000 youths between the ages of 13–17 in the U.S. now identifying as transgender, some states are setting policies designed to protect children from such irreversible treatments made at a critical time in their physical, mental, and emotional development ( Herman, Flores, & O’Neil, 2022 ).

By castigating those who disagree with these procedures as “transphobic,” the people calling for the immediate normalization of these surgeries and treatments have dismissed valid concerns. Many important questions have arisen based on emerging evidence from systematic reviews, whistleblowers, detransitioners, and findings of a new clinical phenomenon of rapid onset of the condition in adolescence rather than early childhood. The fervor of the argument for “gender-affirming care” is not matched by any strength of evidence establishing that such treatments are either safe or effective for promoting long-term well-being. On the contrary, Americans have significant reasons to be instead concerned about the effects of such radical interventions undertaken on children.

Indeed, the American people recognize the riskiness of such treatments on children, with most registered voters believing that “gender-affirming care” for children should be illegal. Moreover, around 85% of children with gender dysphoria do not carry this condition into adolescence—making the notion of using permanent treatments to address temporary conditions quite troubling ( Hembree et al., 2017 ). Nevertheless, many medical professionals in the U.S. are using an “affirm-early/affirm-often” approach when it comes to dealing with children who have gender dysphoria, and they often recommend puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and/or sex-change surgeries.

Though other nations have shied away from such an approach in recent years, a recent review of eligibility criteria for sex-reassignment surgery found that children in the U.S. have access to the procedure at younger ages than minors in Western and Northern Europe ( Do No Harm, 2023a ). The same holds true with the prescription of puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones. Today, some states in the U.S. have more permissive laws than Western and Northern European nations. Not only is there little evidence that some of these “treatments” do anything to benefit the mental health of a child, but studies have shown mounting evidence that transgender drugs and surgical procedures have negative side effects for children. Moreover, many of the drugs prescribed to children for such procedures are prescribed for unapproved use.

A contrasting approach to the prevailing “gender-affirming” philosophy of interventions does exist. It can be described as the “first, do no harm” model, which holds that the risks of medical and surgical interventions outweigh the benefits, and states that doctors should focus on other options, such as exploratory psychotherapy, while ensuring strong mental and social support ( Schwartz, 2021 ; SEGM, 2021a ). The non-profit “Do No Harm,” which consists of numerous physicians and healthcare professionals, has started an education campaign to protect minors from gender ideology and has, like other non-profit groups, concluded that it is appropriate for state lawmakers to now intervene ( Do No Harm, 2023a ; Do No Harm, 2023b ; Do No Harm, 2023c ; Brown & Stathatos, 2022 ). The Society for Evidence Based Gender Medicine (SEGM) has also highlighted the lack of quality evidence and recommended that the medical community urgently address concerns with current practices while endorsing the approach to “first, do no harm” ( SEGM, 2023 ; SEGM, 2021b ). Policymakers in the U.S. should consider all of this data and adopt policies that protect children from potentially harmful and irreversible procedures.

This report builds upon the foundation set by Do No Harm and SEGM by compiling knowledge from a diversified set of resources to understand the history and diagnosis of gender dysphoria, explore different treatment models for the condition, and investigate how other countries approach the issue relative to how it is dealt with in the U.S. Finally, this report reviews how the American people perceive this issue and then outlines state actions to protect children.

Section One: Defining Gender Dysphoria and Understanding the Role of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

To fully understand pediatric gender medicine, it is critical to start with the diagnostic history of gender dysphoria and the evolution of the primary tool used by clinicians to make the diagnosis. Originally published in 1952 by the American Psychiatric Association (APA), the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is considered the “go-to” reference for the characterization and diagnosis of mental disorders in the U.S. and much of the world ( Kawa & Giordano, 2012 ).

The DSM is translated into over 20 languages and is the leading mental disorder diagnostic resource, exerting heavy influence in the field of psychiatry and across society over the last 70 years ( Kawa & Giordano, 2012 ). This resource is used by clinicians, researchers, policymakers, courts, and insurance companies alike. The DSM is now on volume five, with each edition reflecting a change of definitions and inclusions intended to represent current medical thinking—some with significant impact. As an example, between DSM-II to DSM-III, the number of mental disorder categories rose from 182 to 265, partly due to a shift from considering mental disorders as psychological states to considering them discrete disease categories based on symptoms—a shift one source noted as “an attempt to ‘re-medicalize’ American psychiatry” ( Kawa & Giordano, 2012 ). The most recent version, DSM-5 (the version updated its notation from Roman numerals to numbers), included nearly 300 mental disorders and took 14 years of planning and preparation to publish ( Suris et al. 2016 ).

It was not until DSM-III (1980) that any term related to gender dysphoria was included. The term used in the DSM-III was “transsexualism,” and then was later changed to “gender identity disorder in adults and adolescents” in the DSM-IV released in 1994. In 2013, the DSM-5 was released and again changed the term to “gender dysphoria” ( APA, 2017 ). Given the above history regarding the DSM, it is also important to note that the symptom-based disease categorization of the DSM-III led to an increase in psychopharmacological interventions.

The revised text version of the DSM-5, the DSM-5-TR, was published in 2022. This edition included significant updates, notably the direction to use “culturally-sensitive language,” such as changing “desired gender” to “experienced gender” and changing “cross-sex medical procedure” to “gender-affirming medical treatment” ( APA, 2022a ).

The DSM-5-TR definition of gender dysphoria in adolescents and adults is as follows:

“ … a marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and their assigned gender, lasting at least 6 months, as manifested by at least two of the following:

A marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and primary and/or secondary sex characteristics (or in young adolescents, the anticipated secondary sex characteristics)

A strong desire to be rid of one’s primary and/or secondary sex characteristics because of a marked incongruence with one’s experienced/expressed gender (or in young adolescents, a desire to prevent the development of the anticipated secondary sex characteristics)

A strong desire for the primary and/or secondary sex characteristics of the other gender

A strong desire to be of the other gender (or some alternative gender different from one’s assigned gender)

A strong desire to be treated as the other gender (or some alternative gender different from one’s assigned gender)

A strong conviction that one has the typical feelings and reactions of the other gender (or some alternative gender different from one’s assigned gender),”

( APA, 2022b ).

Additionally, the DSM-5-TR definition of gender dysphoria in children is as follows:

“ … a marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and assigned gender, lasting at least 6 months, as manifested by at least six of the following (one of which must be the first criterion):

A strong desire to be of the other gender or an insistence that one is the other gender (or some alternative gender different from one’s assigned gender)

In boys (assigned gender), a strong preference for cross-dressing or simulating female attire; or in girls (assigned gender), a strong preference for wearing only typical masculine clothing and a strong resistance to the wearing of typical feminine clothing

A strong preference for cross-gender roles in make-believe play or fantasy play

A strong preference for the toys, games or activities stereotypically used or engaged in by the other gender

A strong preference for playmates of the other gender

In boys (assigned gender), a strong rejection of typically masculine toys, games, and activities and a strong avoidance of rough-and-tumble play; or in girls (assigned gender), a strong rejection of typically feminine toys, games, and activities

A strong dislike of one’s sexual anatomy

A strong desire for the physical sex characteristics that match one’s experienced gender,”

Notably, the diagnostic criteria for both include association of the condition with clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning ( APA, 2022b ).

Because of the millions of lives impacted by the DSM, researchers have raised concerns about potential political and financial biases of authors contributing to the clinical reference book. The Society for Humanistic Psychology has been a leader in elevating concerns over the DSM-5 and was critical in launching a petition of over 15,000 concerned mental health professionals and groups from around the world ( Kamens, Elkins, & Robbins, 2017 ). Topping the list of their concerns is a conflict of interest among the authors. Many DSM panel members have direct financial ties to the pharmaceutical industry, and several of the disorders call for pharmacological treatment as the first-line intervention ( Cosgrove & Krimsky, 2012 ).

It is also worth noting that the DSM-5-TR included other considerable “cultural changes.” Published in 2022 as a text revision to the latest DSM-5, the DSM-5-TR changed (among other things) the term “race/racial” to “racialized” to underscore that race is a social construct ( Blanchfield, 2022 ). It also changed “Latino/Latina” to “Latinx” to promote gender equality and discontinued the use of “minority” and “non-White” to avoid creating a social hierarchy ( Blanchfield, 2022 ).

The DSM-5 was designed to include cultural, racial, and gender considerations. As a part of their review and rationale for updating the DSM-5, “a DSM-5 Culture and Gender Study Group was appointed to provide guidelines for the work group literature reviews and data analyses that served as the empirical rationale for draft changes” to ensure that cultural factors were included in revisions ( Regier et al. 2013 ). Although these considerations were included in the DMS-5, updates were made in the DSM-5-TR in “response to concerns that race, ethnoracial differences, racism and discrimination be handled appropriately” ( APA, 2022c ). The strategies used to address these concerns were 1) a 19-person review committee on cultural issues and 2) a 10-person Ethnoracial Equity and Inclusion Work Group made up of practitioners from diverse backgrounds ( APA, 2022c ). Given that the DSM is the mental disorder diagnostic tool used in much of the world, it is critical to note the changes that have been made in response to social, cultural, and political pressures rather than a change in medical data and scientific evidence.

Section Two: The Treatment of Gender Dysphoria

Today, U.S. government agencies and many medical professional groups have signaled their support for these types of treatments. Under the Biden Administration, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services states that for children, “early gender-affirming care is crucial to overall health and well-being” ( HHS Office of Population Affairs, n.d.). Many medical professionals in the U.S. accept an “affirm-only/affirm-early” approach to gender transition, which strives to implement interventions (including hormonal or surgical) to help a child better align with his or her “gender identity” ( Do No Harm, 2023a ). Though surgery and hormonal treatments are permanent, evidence indicates that about 85% of cases of children with gender dysphoria do not persist into adolescence ( Hembree et al., 2017 ). Nevertheless, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) embraces the approach of early medical intervention for children and adolescents ( Rafferty et al., 2018 ).

Along with the AAP, multiple medical professional guidelines explain that the appropriate treatment of gender dysphoria in children and adolescents should be used in a “gender-affirmative care model” (GACM) and may include:

Psychotherapy;

Hormone or Puberty Blockers;

Cross-Sex Hormone Therapy; and/or

Sex Reassignment Surgery

The GACM allows youth to progress through some or all interventions depending on timing and pubertal maturity ( Brown & Stathatos, 2022 ; Rafferty et al., 2018 ). Psychotherapy has an important distinction; it has a primary role in another model of care known as “first, do no harm” ( Rafferty et al., 2018 ; Schwartz, 2021 ). In this model, medical and surgical interventions are considered to carry greater risk than benefit for youth, a position well summarized by psychologist David Schwartz, Ph.D.:

… in the treatment of children and adolescents, no matter what the diagnosis, encouraging mastectomy, ovariectomy, uterine extirpation, penile disablement, tracheal shave, the prescription of hormones which are out of line with the genetic make-up of the child, or puberty blockers, are all clinical practices which run an unacceptably high risk of doing harm ( SEGM, 2021 ).

Many of the puberty blockers and cross-sex hormone therapies used to treat gender dysphoria in children are prescribed off-label (for a purpose not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)). Therefore, they can pose a greater risk, including the risk of unknown long-term effects, to the children who receive them. In 2021, the Texas Attorney General launched an investigation into two pharmaceutical companies for allegedly advertising and promoting the off-label use of puberty blockers without disclosing any of their risks ( Attorney General of Texas, 2021 ). In 2022, the FDA also issued a new warning for commonly used puberty blockers, including “recommendations to monitor patients taking GnRH agonists for signs and symptoms of pseudotumor cerebri, including headache, papilledema, blurred or loss of vision, diplopia, pain behind the eye or pain with eye movement, tinnitus, dizziness and nausea” ( FDA, 2022 ). Despite these facts, a growing number of children are being prescribed these drugs for unapproved uses.

There are significant side effects and limited research on the long-term impacts and efficacy of various treatments used in a GACM of gender dysphoria in children. Patients and parents are advised that the use of puberty blockers in children may be associated with lower bone density, stunted growth, fertility issues, and underdevelopment of genital tissue ( Mayo Clinic, 2022 ; St. Louis Children’s Hospital, n.d.; Brown & Stathatos, 2022 ). Moreover, a study conducted in England demonstrated similar negative side effects, such as lowered bone density and stunted growth, without showing a change in the psychological well-being of the children studied ( Carmichael et al., 2021, p. 18 ; Brown & Stathatos, 2022 ). Cross-sex hormones prescribed to children also demonstrated a plethora of side effects, including blood clots in veins and permanent infertility ( CDC, n.d .; NHS England, 2016, p. 8 ; Brown & Stathatos, 2022 ). Importantly, cross-sex hormones can result in the development of secondary sex characteristics such as the development of breasts in male-to-female patients and deepening of the voice in female-to-male patients that, though desired at the time, are irreversible ( NHS England, 2020b ; Brown & Stathatos, 2022 ). Moreover, the neurocognitive effects of pubertal suppression are unknown. International experts are in consensus about the need to assess long-term effects and have stated that: “Taken as a whole, the existing knowledge about puberty and the brain raises the possibility that suppressing sex hormone production during this period could alter neurodevelopment in complex ways—not all of which may be beneficial” ( Chen et al. 2020 ).

Proponents of a GACM frequently claim that it is the only way to improve mental health and reduce suicide risk in youth. However, a 40-year cohort study from Sweden on transsexual individuals undergoing sex-reassignment surgery—one of the most comprehensive long-term studies available—found that high suicide risk persisted after surgical procedures at a rate 19.1 times higher than the general population ( Dhejne et al., 2011 ). Another Swedish population study with one of the largest cohorts established to date evaluated (in a corrected analysis from the original publication) mental health outcomes among transgender individuals who received surgical interventions and those who did not and found “no advantage of surgery in relation to subsequent mood or anxiety disorder-related health care visits or prescriptions or hospitalizations following suicide attempts” ( Branstrom, & Pachankis, 2019 ; Kalin, 2020 ).

Treatment protocols for gender dysphoria often follow the guidelines of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), the Endocrine Society (an international medical professional association), and the American Association of Pediatrics (AAP). However, a recent review article from the Manhattan Institute outlined significant flaws with the recommendations from each organization based on the evidence available in the academic literature and from best practices in other countries ( Sapir, 2022 ). Notably, the AAP position paper, which supported early affirmation and treatment of gender dysphoria in childhood, was fact-checked by psychologist James Cantor, Ph.D., of the Toronto Sexuality Center. Dr. Cantor found that the AAP position paper omitted information regarding the low frequency of gender dysphoria persisting from childhood to adolescence ( Cantor, 2020 ). He also found that the AAP paper, when rejecting “watchful waiting,” misrepresented citations regarding the approach that aims to put pharmacologic or surgical intervention on hold while the patient receives other supportive care and counseling ( Cantor, 2020 ).

Additionally, the Endocrine Society’s “clinical practice guideline” from 2017 assesses the quality of evidence for each of its recommendations ( Hembree et al., 2017 ). All six recommendations specifically related to treatment for adolescents found only a “low” or “very low” quality of evidence ( Hembree et al., 2017 ). One recommendation (2.5) that is listed as a weak recommendation with a very low quality of evidence is particularly concerning: