The clockwork universe: is free will an illusion?

A growing chorus of scientists and philosophers argue that free will does not exist. Could they be right?

T owards the end of a conversation dwelling on some of the deepest metaphysical puzzles regarding the nature of human existence, the philosopher Galen Strawson paused, then asked me: “Have you spoken to anyone else yet who’s received weird email?” He navigated to a file on his computer and began reading from the alarming messages he and several other scholars had received over the past few years. Some were plaintive, others abusive, but all were fiercely accusatory. “Last year you all played a part in destroying my life,” one person wrote. “I lost everything because of you – my son, my partner, my job, my home, my mental health. All because of you, you told me I had no control, how I was not responsible for anything I do, how my beautiful six-year-old son was not responsible for what he did … Goodbye, and good luck with the rest of your cancerous, evil, pathetic existence.” “Rot in your own shit Galen,” read another note, sent in early 2015. “Your wife, your kids your friends, you have smeared all there [sic] achievements you utter fucking prick,” wrote the same person, who subsequently warned: “I’m going to fuck you up.” And then, days later, under the subject line “Hello”: “I’m coming for you.” “This was one where we had to involve the police,” Strawson said. Thereafter, the violent threats ceased.

It isn’t unheard of for philosophers to receive death threats. The Australian ethicist Peter Singer, for example, has received many, in response to his argument that, in highly exceptional circumstances, it might be morally justifiable to kill newborn babies with severe disabilities. But Strawson, like others on the receiving end of this particular wave of abuse, had merely expressed a longstanding position in an ancient debate that strikes many as the ultimate in “armchair philosophy”, wholly detached from the emotive entanglements of real life. They all deny that human beings possess free will. They argue that our choices are determined by forces beyond our ultimate control – perhaps even predetermined all the way back to the big bang – and that therefore nobody is ever wholly responsible for their actions. Reading back over the emails, Strawson, who gives the impression of someone far more forgiving of other people’s flaws than of his own, found himself empathising with his harassers’ distress. “I think for these people it’s just an existential catastrophe,” he said. “And I think I can see why.”

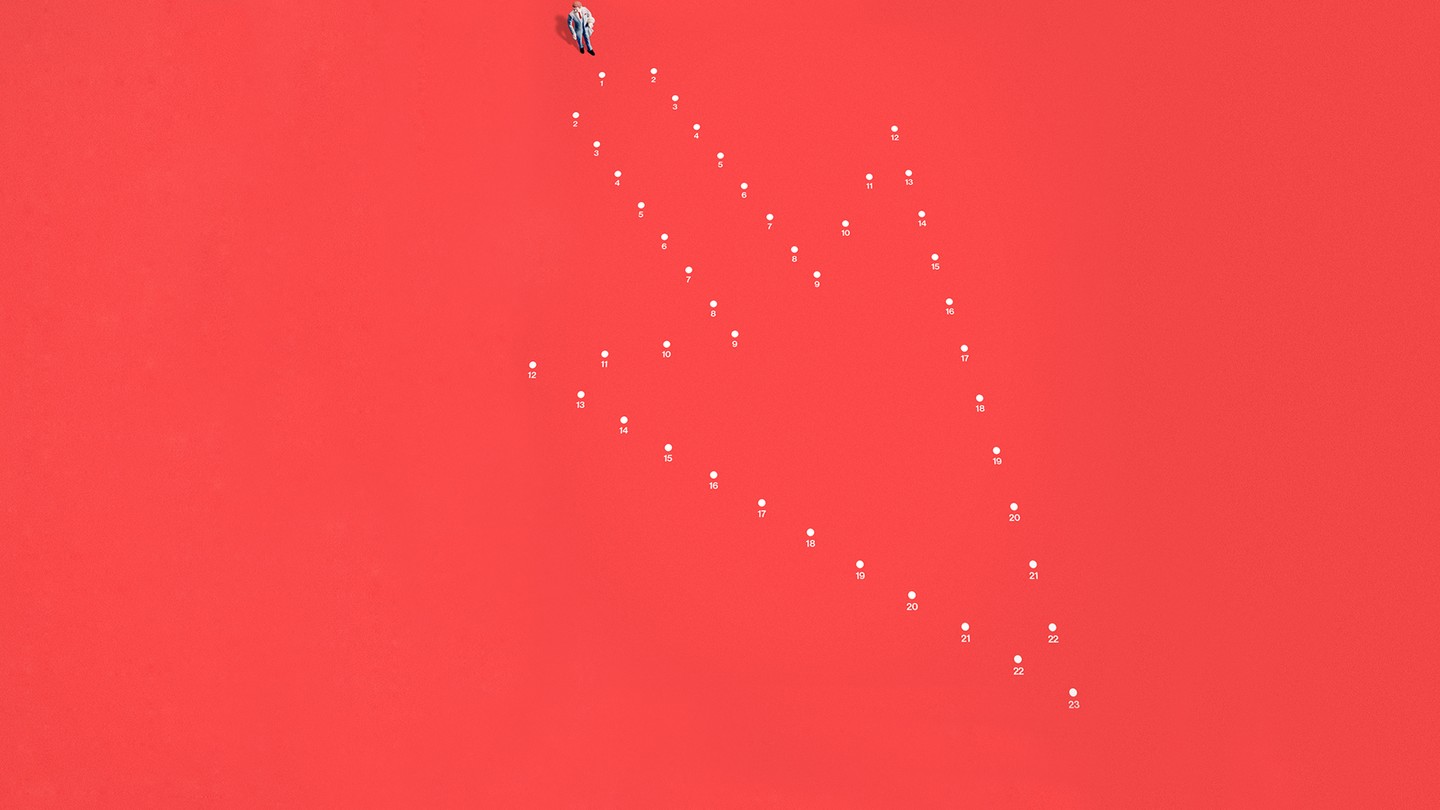

The difficulty in explaining the enigma of free will to those unfamiliar with the subject isn’t that it’s complex or obscure. It’s that the experience of possessing free will – the feeling that we are the authors of our choices – is so utterly basic to everyone’s existence that it can be hard to get enough mental distance to see what’s going on. Suppose you find yourself feeling moderately hungry one afternoon, so you walk to the fruit bowl in your kitchen, where you see one apple and one banana. As it happens, you choose the banana. But it seems absolutely obvious that you were free to choose the apple – or neither, or both – instead. That’s free will: were you to rewind the tape of world history, to the instant just before you made your decision, with everything in the universe exactly the same, you’d have been able to make a different one.

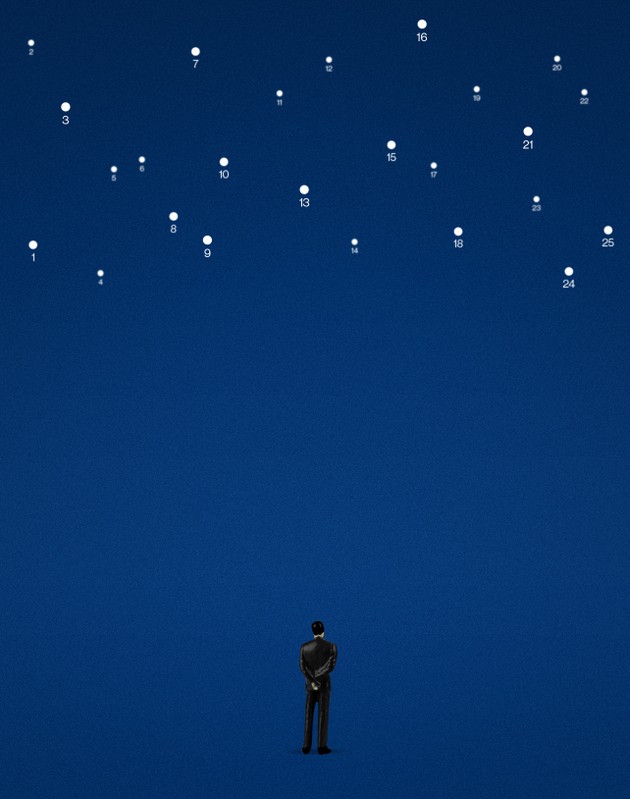

Nothing could be more self-evident. And yet according to a growing chorus of philosophers and scientists, who have a variety of different reasons for their view, it also can’t possibly be the case. “This sort of free will is ruled out, simply and decisively, by the laws of physics,” says one of the most strident of the free will sceptics, the evolutionary biologist Jerry Coyne. Leading psychologists such as Steven Pinker and Paul Bloom agree, as apparently did the late Stephen Hawking, along with numerous prominent neuroscientists, including VS Ramachandran, who called free will “an inherently flawed and incoherent concept” in his endorsement of Sam Harris’s bestselling 2012 book Free Will, which also makes that argument. According to the public intellectual Yuval Noah Harari, free will is an anachronistic myth – useful in the past, perhaps, as a way of motivating people to fight against tyrants or oppressive ideologies, but rendered obsolete by the power of modern data science to know us better than we know ourselves, and thus to predict and manipulate our choices.

Arguments against free will go back millennia, but the latest resurgence of scepticism has been driven by advances in neuroscience during the past few decades. Now that it’s possible to observe – thanks to neuroimaging – the physical brain activity associated with our decisions, it’s easier to think of those decisions as just another part of the mechanics of the material universe, in which “free will” plays no role. And from the 1980s onwards, various specific neuroscientific findings have offered troubling clues that our so-called free choices might actually originate in our brains several milliseconds, or even much longer, before we’re first aware of even thinking of them.

Despite the criticism that this is all just armchair philosophy, the truth is that the stakes could hardly be higher. Were free will to be shown to be nonexistent – and were we truly to absorb the fact – it would “precipitate a culture war far more belligerent than the one that has been waged on the subject of evolution”, Harris has written. Arguably, we would be forced to conclude that it was unreasonable ever to praise or blame anyone for their actions, since they weren’t truly responsible for deciding to do them; or to feel guilt for one’s misdeeds, pride in one’s accomplishments, or gratitude for others’ kindness. And we might come to feel that it was morally unjustifiable to mete out retributive punishment to criminals, since they had no ultimate choice about their wrongdoing. Some worry that it might fatally corrode all human relations, since romantic love, friendship and neighbourly civility alike all depend on the assumption of choice: any loving or respectful gesture has to be voluntary for it to count.

Peer over the precipice of the free will debate for a while, and you begin to appreciate how an already psychologically vulnerable person might be nudged into a breakdown, as was apparently the case with Strawson’s email correspondents. Harris has taken to prefacing his podcasts on free will with disclaimers, urging those who find the topic emotionally distressing to give them a miss. And Saul Smilansky, a professor of philosophy at the University of Haifa in Israel, who believes the popular notion of free will is a mistake, told me that if a graduate student who was prone to depression sought to study the subject with him, he would try to dissuade them. “Look, I’m naturally a buoyant person,” he said. “I have the mentality of a village idiot: it’s easy to make me happy. Nevertheless, the free will problem is really depressing if you take it seriously. It hasn’t made me happy, and in retrospect, if I were at graduate school again, maybe a different topic would have been preferable.”

Smilansky is an advocate of what he calls “illusionism”, the idea that although free will as conventionally defined is unreal, it’s crucial people go on believing otherwise – from which it follows that an article like this one might be actively dangerous. (Twenty years ago, he said, he might have refused to speak to me, but these days free will scepticism was so widely discussed that “the horse has left the barn”.) “On the deepest level, if people really understood what’s going on – and I don’t think I’ve fully internalised the implications myself, even after all these years – it’s just too frightening and difficult,” Smilansky said. “For anyone who’s morally and emotionally deep, it’s really depressing and destructive. It would really threaten our sense of self, our sense of personal value. The truth is just too awful here.”

T he conviction that nobody ever truly chooses freely to do anything – that we’re the puppets of forces beyond our control – often seems to strike its adherents early in their intellectual careers, in a sudden flash of insight. “I was sitting in a carrel in Wolfson College [in Oxford] in 1975, and I had no idea what I was going to write my DPhil thesis about,” Strawson recalled. “I was reading something about Kant’s views on free will, and I was just electrified. That was it.” The logic, once glimpsed, seems coldly inexorable. Start with what seems like an obvious truth: anything that happens in the world, ever, must have been completely caused by things that happened before it. And those things must have been caused by things that happened before them – and so on, backwards to the dawn of time: cause after cause after cause, all of them following the predictable laws of nature, even if we haven’t figured all of those laws out yet. It’s easy enough to grasp this in the context of the straightforwardly physical world of rocks and rivers and internal combustion engines. But surely “one thing leads to another” in the world of decisions and intentions, too. Our decisions and intentions involve neural activity – and why would a neuron be exempt from the laws of physics any more than a rock?

So in the fruit bowl example, there are physiological reasons for your feeling hungry in the first place, and there are causes – in your genes, your upbringing, or your current environment – for your choosing to address your hunger with fruit, rather than a box of doughnuts. And your preference for the banana over the apple, at the moment of supposed choice, must have been caused by what went before, presumably including the pattern of neurons firing in your brain, which was itself caused – and so on back in an unbroken chain to your birth, the meeting of your parents, their births and, eventually, the birth of the cosmos.

But if all that’s true, there’s simply no room for the kind of free will you might imagine yourself to have when you see the apple and banana and wonder which one you’ll choose. To have what’s known in the scholarly jargon as “contra-causal” free will – so that if you rewound the tape of history back to the moment of choice, you could make a different choice – you’d somehow have to slip outside physical reality. To make a choice that wasn’t merely the next link in the unbroken chain of causes, you’d have to be able to stand apart from the whole thing, a ghostly presence separate from the material world yet mysteriously still able to influence it. But of course you can’t actually get to this supposed place that’s external to the universe, separate from all the atoms that comprise it and the laws that govern them. You just are some of the atoms in the universe, governed by the same predictable laws as all the rest.

It was the French polymath Pierre-Simon Laplace, writing in 1814, who most succinctly expressed the puzzle here: how can there be free will, in a universe where events just crank forwards like clockwork? His thought experiment is known as Laplace’s demon, and his argument went as follows: if some hypothetical ultra-intelligent being – or demon – could somehow know the position of every atom in the universe at a single point in time, along with all the laws that governed their interactions, it could predict the future in its entirety. There would be nothing it couldn’t know about the world 100 or 1,000 years hence, down to the slightest quiver of a sparrow’s wing. You might think you made a free choice to marry your partner, or choose a salad with your meal rather than chips; but in fact Laplace’s demon would have known it all along, by extrapolating out along the endless chain of causes. “For such an intellect,” Laplace said, “nothing could be uncertain, and the future, just like the past, would be present before its eyes.”

It’s true that since Laplace’s day, findings in quantum physics have indicated that some events, at the level of atoms and electrons, are genuinely random, which means they would be impossible to predict in advance, even by some hypothetical megabrain. But few people involved in the free will debate think that makes a critical difference. Those tiny fluctuations probably have little relevant impact on life at the scale we live it, as human beings. And in any case, there’s no more freedom in being subject to the random behaviours of electrons than there is in being the slave of predetermined causal laws. Either way, something other than your own free will seems to be pulling your strings.

B y far the most unsettling implication of the case against free will, for most who encounter it, is what it seems to say about morality: that nobody, ever, truly deserves reward or punishment for what they do, because what they do is the result of blind deterministic forces (plus maybe a little quantum randomness). “For the free will sceptic,” writes Gregg Caruso in his new book Just Deserts, a collection of dialogues with his fellow philosopher Daniel Dennett, “it is never fair to treat anyone as morally responsible.” Were we to accept the full implications of that idea, the way we treat each other – and especially the way we treat criminals – might change beyond recognition.

Consider the case of Charles Whitman. Just after midnight on 1 August 1966, Whitman – an outgoing and apparently stable 25-year-old former US Marine – drove to his mother’s apartment in Austin, Texas, where he stabbed her to death. He returned home, where he killed his wife in the same manner. Later that day, he took an assortment of weapons to the top of a high building on the campus of the University of Texas, where he began shooting randomly for about an hour and a half. By the time Whitman was killed by police, 12 more people were dead, and one more died of his injuries years afterwards – a spree that remains the US’s 10th worst mass shooting.

Within hours of the massacre, the authorities discovered a note that Whitman had typed the night before. “I don’t quite understand what compels me to type this letter,” he wrote. “Perhaps it is to leave some vague reason for the actions I have recently performed. I don’t really understand myself these days. I am supposed to be an average reasonable and intelligent young man. However, lately (I can’t recall when it started) I have been a victim of many unusual and irrational thoughts [which] constantly recur, and it requires a tremendous mental effort to concentrate on useful and progressive tasks … After my death I wish that an autopsy would be performed to see if there is any visible physical disorder.” Following the first two murders, he added a coda: “Maybe research can prevent further tragedies of this type.” An autopsy was performed, revealing the presence of a substantial brain tumour, pressing on Whitman’s amygdala, the part of the brain governing “fight or flight” responses to fear.

As the free will sceptics who draw on Whitman’s case concede, it’s impossible to know if the brain tumour caused Whitman’s actions. What seems clear is that it certainly could have done so – and that almost everyone, on hearing about it, undergoes some shift in their attitude towards him. It doesn’t make the killings any less horrific. Nor does it mean the police weren’t justified in killing him. But it does make his rampage start to seem less like the evil actions of an evil man, and more like the terrible symptom of a disorder, with Whitman among its victims. The same is true for another wrongdoer famous in the free-will literature, the anonymous subject of the 2003 paper Right Orbitofrontal Tumor with Paedophilia Symptom and Constructional Apraxia Sign, a 40-year-old schoolteacher who suddenly developed paedophilic urges and began seeking out child pornography, and was subsequently convicted of child molestation. Soon afterwards, complaining of headaches, he was diagnosed with a brain tumour; when it was removed, his paedophilic urges vanished. A year later, they returned – as had his tumour, detected in another brain scan.

If you find the presence of a brain tumour in these cases in any way exculpatory, though, you face a difficult question: what’s so special about a brain tumour, as opposed to all the other ways in which people’s brains cause them to do things? When you learn about the specific chain of causes that were unfolding inside Charles Whitman’s skull, it has the effect of seeming to make him less personally responsible for the terrible acts he committed. But by definition, anyone who commits any immoral act has a brain in which a chain of prior causes had unfolded, leading to the act; if that weren’t the case, they’d never have committed the act. “A neurological disorder appears to be just a special case of physical events giving rise to thoughts and actions,” is how Harris expresses it. “Understanding the neurophysiology of the brain, therefore, would seem to be as exculpatory as finding a tumour in it.” It appears to follow that as we understand ever more about how the brain works, we’ll illuminate the last shadows in which something called “free will” might ever have lurked – and we’ll be forced to concede that a criminal is merely someone unlucky enough to find himself at the end of a causal chain that culminates in a crime. We can still insist the crime in question is morally bad; we just can’t hold the criminal individually responsible. (Or at least that’s where the logic seems to lead our modern minds: there’s a rival tradition , going back to the ancient Greeks, which holds that you can be held responsible for what’s fated to happen to you anyway.)

For Caruso, who teaches philosophy at the State University of New York, what all this means is that retributive punishment – punishing a criminal because he deserves it, rather than to protect the public, or serve as a warning to others – can’t ever be justified. Like Strawson, he has received email abuse from people disturbed by the implications. Retribution is central to all modern systems of criminal justice, yet ultimately, Caruso thinks, “it’s a moral injustice to hold someone responsible for actions that are beyond their control. It’s capricious.” Indeed some psychological research, he points out, suggests that people believe in free will partly because they want to justify their appetite for retribution. “What seems to happen is that people come across an action they disapprove of; they have a high desire to blame or punish; so they attribute to the perpetrator the degree of control [over their own actions] that would be required to justify blaming them.” (It’s no accident that the free will controversy is entangled in debates about religion: following similar logic, sinners must freely choose to sin, in order for God’s retribution to be justified.)

Caruso is an advocate of what he calls the “public health-quarantine” model of criminal justice, which would transform the institutions of punishment in a radically humane direction. You could still restrain a murderer, on the same rationale that you can require someone infected by Ebola to observe a quarantine: to protect the public. But you’d have no right to make the experience any more unpleasant than was strictly necessary for public protection. And you would be obliged to release them as soon as they no longer posed a threat. (The main focus, in Caruso’s ideal world, would be on redressing social problems to try stop crime happening in the first place – just as public health systems ought to focus on preventing epidemics happening to begin with.)

It’s tempting to try to wriggle out of these ramifications by protesting that, while people might not choose their worst impulses – for murder, say – they do have the choice not to succumb to them. You can feel the urge to kill someone but resist it, or even seek psychiatric help. You can take responsibility for the state of your personality. And don’t we all do that, all the time, in more mundane ways, whenever we decide to acquire a new professional skill, become a better listener, or finally get fit?

But this is not the escape clause it might seem. After all, the free will sceptics insist, if you do manage to change your personality in some admirable way, you must already have possessed the kind of personality capable of implementing such a change – and you didn’t choose that . None of this requires us to believe that the worst atrocities are any less appalling than we previously thought. But it does entail that the perpetrators can’t be held personally to blame. If you’d been born with Hitler’s genes, and experienced Hitler’s upbringing, you would be Hitler – and ultimately it’s only good fortune that you weren’t. In the end, as Strawson puts it, “luck swallows everything”.

G iven how watertight the case against free will can appear, it may be surprising to learn that most philosophers reject it: according to a 2009 survey, conducted by the website PhilPapers, only about 12% of them are persuaded by it. And the disagreement can be fraught, partly because free will denial belongs to a wider trend that drives some philosophers spare – the tendency for those trained in the hard sciences to make sweeping pronouncements about debates that have raged in philosophy for years, as if all those dull-witted scholars were just waiting for the physicists and neuroscientists to show up. In one chilly exchange, Dennett paid a backhanded compliment to Harris, who has a PhD in neuroscience, calling his book “remarkable” and “valuable” – but only because it was riddled with so many wrongheaded claims: “I am grateful to Harris for saying, so boldly and clearly, what less outgoing scientists are thinking but keeping to themselves.”

What’s still more surprising, and hard to wrap one’s mind around, is that most of those who defend free will don’t reject the sceptics’ most dizzying assertion – that every choice you ever make might have been determined in advance. So in the fruit bowl example, a majority of philosophers agree that if you rewound the tape of history to the moment of choice, with everything in the universe exactly the same, you couldn’t have made a different selection. That kind of free will is “as illusory as poltergeists”, to quote Dennett. What they claim instead is that this doesn’t matter: that even though our choices may be determined, it makes sense to say we’re free to choose. That’s why they’re known as “compatibilists”: they think determinism and free will are compatible. (There are many other positions in the debate, including some philosophers, many Christians among them, who think we really do have “ghostly” free will; and others who think the whole so-called problem is a chimera, resulting from a confusion of categories, or errors of language.)

To those who find the case against free will persuasive, compatibilism seems outrageous at first glance. How can we possibly be free to choose if we aren’t, in fact, you know, free to choose? But to grasp the compatibilists’ point, it helps first to think about free will not as a kind of magic, but as a mundane sort of skill – one which most adults possess, most of the time. As the compatibilist Kadri Vihvelin writes, “we have the free will we think we have, including the freedom of action we think we have … by having some bundle of abilities and being in the right kind of surroundings.” The way most compatibilists see things, “being free” is just a matter of having the capacity to think about what you want, reflect on your desires, then act on them and sometimes get what you want. When you choose the banana in the normal way – by thinking about which fruit you’d like, then taking it – you’re clearly in a different situation from someone who picks the banana because a fruit-obsessed gunman is holding a pistol to their head; or someone afflicted by a banana addiction, compelled to grab every one they see. In all of these scenarios, to be sure, your actions belonged to an unbroken chain of causes, stretching back to the dawn of time. But who cares? The banana-chooser in one of them was clearly more free than in the others.

“Harris, Pinker, Coyne – all these scientists, they all make the same two-step move,” said Eddy Nahmias, a compatibilist philosopher at Georgia State University in the US. “Their first move is always to say, ‘well, here’s what free will means’” – and it’s always something nobody could ever actually have, in the reality in which we live. “And then, sure enough, they deflate it. But once you have that sort of balloon in front of you, it’s very easy to deflate it, because any naturalistic account of the world will show that it’s false.”

Consider hypnosis. A doctrinaire free will sceptic might feel obliged to argue that a person hypnotised into making a particular purchase is no less free than someone who thinks about it, in the usual manner, before reaching for their credit card. After all, their idea of free will requires that the choice wasn’t fully determined by prior causes; yet in both cases, hypnotised and non-hypnotised, it was. “But come on, that’s just really annoying ,” said Helen Beebee, a philosopher at the University of Manchester who has written widely on free will, expressing an exasperation commonly felt by compatibilists toward their rivals’ more outlandish claims. “In some sense, I don’t care if you call it ‘free will’ or ‘acting freely’ or anything else – it’s just that it obviously does matter, to everybody, whether they get hypnotised into doing things or not.”

Granted, the compatibilist version of free will may be less exciting. But it doesn’t follow that it’s worthless. Indeed, it may be (in another of Dennett’s phrases) the only kind of “free will worth wanting”. You experience the desire for a certain fruit, you act on it, and you get the fruit, with no external gunmen or internal disorders influencing your choice. How could a person ever be freer than that?

Thinking of free will this way also puts a different spin on some notorious experiments conducted in the 80s by the American neuroscientist Benjamin Libet, which have been interpreted as offering scientific proof that free will doesn’t exist. Wiring his subjects to a brain scanner, and asking them to flex their hands at a moment of their choosing, Libet seemed to show that their choice was detectable from brain activity 300 milliseconds before they made a conscious decision. (Other studies have indicated activity up to 10 seconds before a conscious choice.) How could these subjects be said to have reached their decisions freely, if the lab equipment knew their decisions so far in advance? But to most compatibilists, this is a fuss about nothing. Like everything else, our conscious choices are links in a causal chain of neural processes, so of course some brain activity precedes the moment at which we become aware of them.

From this down-to-earth perspective, there’s also no need to start panicking that cases like Charles Whitman’s might mean we could never hold anybody responsible for their misdeeds, or praise them for their achievements. (In their defence, several free will sceptics I spoke to had their reasons for not going that far, either.) Instead, we need only ask whether someone had the normal ability to choose rationally, reflecting on the implications of their actions. We all agree that newborn babies haven’t developed that yet, so we don’t blame them for waking us in the night; and we believe most non-human animals don’t possess it – so few of us rage indignantly at wasps for stinging us. Someone with a severe neurological or developmental impairment would surely lack it, too, perhaps including Whitman. But as for everyone else: “ Bernie Madoff is the example I always like to use,” said Nahmias. “Because it’s so clear that he knew what he was doing, and that he knew that what he was doing was wrong, and he did it anyway.” He did have the ability we call “free will” – and used it to defraud his investors of more than $17bn.

To the free will sceptics, this is all just a desperate attempt at face-saving and changing the subject – an effort to redefine free will not as the thing we all feel, when faced with a choice, but as something else, unworthy of the name. “People hate the idea that they aren’t agents who can make free choices,” Jerry Coyne has argued. Harris has accused Dennett of approaching the topic as if he were telling someone bent on discovering the lost city of Atlantis that they ought to be satisfied with a trip to Sicily. After all, it meets some of the criteria: it’s an island in the sea, home to a civilisation with ancient roots. But the facts remain: Atlantis doesn’t exist. And when it felt like it wasn’t inevitable you’d choose the banana, the truth is that it actually was.

I t’s tempting to dismiss the free will controversy as irrelevant to real life, on the grounds that we can’t help but feel as though we have free will, whatever the philosophical truth may be. I’m certainly going to keep responding to others as though they had free will: if you injure me, or someone I love, I can guarantee I’m going to be furious, instead of smiling indulgently on the grounds that you had no option. In this experiential sense, free will just seems to be a given.

But is it? When my mind is at its quietest – for example, drinking coffee early in the morning, before the four-year-old wakes up – things are liable to feel different. In such moments of relaxed concentration, it seems clear to me that my intentions and choices, like all my other thoughts and emotions, arise unbidden in my awareness. There’s no sense in which it feels like I’m their author. Why do I put down my coffee mug and head to the shower at the exact moment I do so? Because the intention to do so pops up, caused, no doubt, by all sorts of activity in my brain – but activity that lies outside my understanding, let alone my command. And it’s exactly the same when it comes to those weightier decisions that seem to express something profound about the kind of person I am: whether to attend the funeral of a certain relative, say, or which of two incompatible career opportunities to pursue. I can spend hours or even days engaged in what I tell myself is “reaching a decision” about those, when what I’m really doing, if I’m honest, is just vacillating between options – until at some unpredictable moment, or when an external deadline forces the issue, the decision to commit to one path or another simply arises.

This is what Harris means when he declares that, on close inspection, it’s not merely that free will is an illusion, but that the illusion of free will is itself an illusion: watch yourself closely, and you don’t even seem to be free. “If one pays sufficient attention,” he told me by email, “one can notice that there’s no subject in the middle of experience – there is only experience. And everything we experience simply arises on its own.” This is an idea with roots in Buddhism, and echoed by others, including the philosopher David Hume: when you look within, there’s no trace of an internal commanding officer, autonomously issuing decisions. There’s only mental activity, flowing on. Or as Arthur Rimbaud wrote, in a letter to a friend in 1871: “I am a spectator at the unfolding of my thought; I watch it, I listen to it.”

There are reasons to agree with Saul Smilansky that it might be personally and societally detrimental for too many people to start thinking in this way, even if it turns out it’s the truth. (Dennett, although he thinks we do have free will, takes a similar position, arguing that it’s morally irresponsible to promote free-will denial.) In one set of studies in 2008, the psychologists Kathleen Vohs and Jonathan Schooler asked one group of participants to read an excerpt from The Astonishing Hypothesis by Francis Crick, co-discoverer of the structure of DNA, in which he suggests free will is an illusion. The subjects thus primed to doubt the existence of free will proved significantly likelier than others, in a subsequent stage of the experiment, to cheat in a test where there was money at stake. Other research has reported a diminished belief in free will to less willingness to volunteer to help others, to lower levels of commitment in relationships, and lower levels of gratitude.

Unsuccessful attempts to replicate Vohs and Schooler’s findings have called them into question. But even if the effects are real, some free will sceptics argue that the participants in such studies are making a common mistake – and one that might get cleared up rather rapidly, were the case against free will to become better known and understood. Study participants who suddenly become immoral seem to be confusing determinism with fatalism – the idea that if we don’t have free will, then our choices don’t really matter, so we might as well not bother trying to make good ones, and just do as we please instead. But in fact it doesn’t follow from our choices being determined that they don’t matter. It might matter enormously whether you choose to feed your children a diet rich in vegetables or not; or whether you decide to check carefully in both directions before crossing a busy road. It’s just that (according to the sceptics) you don’t get to make those choices freely.

In any case, were free will really to be shown to be nonexistent, the implications might not be entirely negative. It’s true that there’s something repellent about an idea that seems to require us to treat a cold-blooded murderer as not responsible for his actions, while at the same time characterising the love of a parent for a child as nothing more than what Smilansky calls “the unfolding of the given” – mere blind causation, devoid of any human spark. But there’s something liberating about it, too. It’s a reason to be gentler with yourself, and with others. For those of us prone to being hard on ourselves, it’s therapeutic to keep in the back of your mind the thought that you might be doing precisely as well as you were always going to be doing – that in the profoundest sense, you couldn’t have done any more. And for those of us prone to raging at others for their minor misdeeds, it’s calming to consider how easily their faults might have been yours. (Sure enough, some research has linked disbelief in free will to increased kindness.)

Harris argues that if we fully grasped the case against free will, it would be difficult to hate other people: how can you hate someone you don’t blame for their actions? Yet love would survive largely unscathed, since love is “the condition of our wanting those we love to be happy, and being made happy ourselves by that ethical and emotional connection”, neither of which would be undermined. And countless other positive aspects of life would be similarly untouched. As Strawson puts it, in a world without a belief in free will, “strawberries would still taste just as good”.

Those early-morning moments aside, I personally can’t claim to find the case against free will ultimately persuasive; it’s just at odds with too much else that seems obviously true about life. Yet even if only entertained as a hypothetical possibility, free will scepticism is an antidote to that bleak individualist philosophy which holds that a person’s accomplishments truly belong to them alone – and that you’ve therefore only yourself to blame if you fail. It’s a reminder that accidents of birth might affect the trajectories of our lives far more comprehensively than we realise, dictating not only the socioeconomic position into which we’re born, but also our personalities and experiences as a whole: our talents and our weaknesses, our capacity for joy, and our ability to overcome tendencies toward violence, laziness or despair, and the paths we end up travelling. There is a deep sense of human fellowship in this picture of reality – in the idea that, in our utter exposure to forces beyond our control, we might all be in the same boat, clinging on for our lives, adrift on the storm-tossed ocean of luck.

- The long read

- Philosophy (World news)

- Neuroscience

- Stephen Hawking

- Philosophy (Education)

Most viewed

There’s No Such Thing as Free Will

But we’re better off believing in it anyway.

F or centuries , philosophers and theologians have almost unanimously held that civilization as we know it depends on a widespread belief in free will—and that losing this belief could be calamitous. Our codes of ethics, for example, assume that we can freely choose between right and wrong. In the Christian tradition, this is known as “moral liberty”—the capacity to discern and pursue the good, instead of merely being compelled by appetites and desires. The great Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant reaffirmed this link between freedom and goodness. If we are not free to choose, he argued, then it would make no sense to say we ought to choose the path of righteousness.

Today, the assumption of free will runs through every aspect of American politics, from welfare provision to criminal law. It permeates the popular culture and underpins the American dream—the belief that anyone can make something of themselves no matter what their start in life. As Barack Obama wrote in The Audacity of Hope , American “values are rooted in a basic optimism about life and a faith in free will.”

So what happens if this faith erodes?

The sciences have grown steadily bolder in their claim that all human behavior can be explained through the clockwork laws of cause and effect. This shift in perception is the continuation of an intellectual revolution that began about 150 years ago, when Charles Darwin first published On the Origin of Species . Shortly after Darwin put forth his theory of evolution, his cousin Sir Francis Galton began to draw out the implications: If we have evolved, then mental faculties like intelligence must be hereditary. But we use those faculties—which some people have to a greater degree than others—to make decisions. So our ability to choose our fate is not free, but depends on our biological inheritance.

Explore the June 2016 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Galton launched a debate that raged throughout the 20th century over nature versus nurture. Are our actions the unfolding effect of our genetics? Or the outcome of what has been imprinted on us by the environment? Impressive evidence accumulated for the importance of each factor. Whether scientists supported one, the other, or a mix of both, they increasingly assumed that our deeds must be determined by something .

In recent decades, research on the inner workings of the brain has helped to resolve the nature-nurture debate—and has dealt a further blow to the idea of free will. Brain scanners have enabled us to peer inside a living person’s skull, revealing intricate networks of neurons and allowing scientists to reach broad agreement that these networks are shaped by both genes and environment. But there is also agreement in the scientific community that the firing of neurons determines not just some or most but all of our thoughts, hopes, memories, and dreams.

We know that changes to brain chemistry can alter behavior—otherwise neither alcohol nor antipsychotics would have their desired effects. The same holds true for brain structure: Cases of ordinary adults becoming murderers or pedophiles after developing a brain tumor demonstrate how dependent we are on the physical properties of our gray stuff.

Many scientists say that the American physiologist Benjamin Libet demonstrated in the 1980s that we have no free will. It was already known that electrical activity builds up in a person’s brain before she, for example, moves her hand; Libet showed that this buildup occurs before the person consciously makes a decision to move. The conscious experience of deciding to act, which we usually associate with free will, appears to be an add-on, a post hoc reconstruction of events that occurs after the brain has already set the act in motion.

The 20th-century nature-nurture debate prepared us to think of ourselves as shaped by influences beyond our control. But it left some room, at least in the popular imagination, for the possibility that we could overcome our circumstances or our genes to become the author of our own destiny. The challenge posed by neuroscience is more radical: It describes the brain as a physical system like any other, and suggests that we no more will it to operate in a particular way than we will our heart to beat. The contemporary scientific image of human behavior is one of neurons firing, causing other neurons to fire, causing our thoughts and deeds, in an unbroken chain that stretches back to our birth and beyond. In principle, we are therefore completely predictable. If we could understand any individual’s brain architecture and chemistry well enough, we could, in theory, predict that individual’s response to any given stimulus with 100 percent accuracy.

This research and its implications are not new. What is new, though, is the spread of free-will skepticism beyond the laboratories and into the mainstream. The number of court cases, for example, that use evidence from neuroscience has more than doubled in the past decade—mostly in the context of defendants arguing that their brain made them do it. And many people are absorbing this message in other contexts, too, at least judging by the number of books and articles purporting to explain “your brain on” everything from music to magic. Determinism, to one degree or another, is gaining popular currency. The skeptics are in ascendance.

This development raises uncomfortable—and increasingly nontheoretical—questions: If moral responsibility depends on faith in our own agency, then as belief in determinism spreads, will we become morally irresponsible? And if we increasingly see belief in free will as a delusion, what will happen to all those institutions that are based on it?

In 2002, two psychologists had a simple but brilliant idea: Instead of speculating about what might happen if people lost belief in their capacity to choose, they could run an experiment to find out. Kathleen Vohs, then at the University of Utah, and Jonathan Schooler, of the University of Pittsburgh, asked one group of participants to read a passage arguing that free will was an illusion, and another group to read a passage that was neutral on the topic. Then they subjected the members of each group to a variety of temptations and observed their behavior. Would differences in abstract philosophical beliefs influence people’s decisions?

Yes, indeed. When asked to take a math test, with cheating made easy, the group primed to see free will as illusory proved more likely to take an illicit peek at the answers. When given an opportunity to steal—to take more money than they were due from an envelope of $1 coins—those whose belief in free will had been undermined pilfered more. On a range of measures, Vohs told me, she and Schooler found that “people who are induced to believe less in free will are more likely to behave immorally.”

It seems that when people stop believing they are free agents, they stop seeing themselves as blameworthy for their actions. Consequently, they act less responsibly and give in to their baser instincts. Vohs emphasized that this result is not limited to the contrived conditions of a lab experiment. “You see the same effects with people who naturally believe more or less in free will,” she said.

In another study, for instance, Vohs and colleagues measured the extent to which a group of day laborers believed in free will, then examined their performance on the job by looking at their supervisor’s ratings. Those who believed more strongly that they were in control of their own actions showed up on time for work more frequently and were rated by supervisors as more capable. In fact, belief in free will turned out to be a better predictor of job performance than established measures such as self-professed work ethic.

Another pioneer of research into the psychology of free will, Roy Baumeister of Florida State University, has extended these findings. For example, he and colleagues found that students with a weaker belief in free will were less likely to volunteer their time to help a classmate than were those whose belief in free will was stronger. Likewise, those primed to hold a deterministic view by reading statements like “Science has demonstrated that free will is an illusion” were less likely to give money to a homeless person or lend someone a cellphone.

Further studies by Baumeister and colleagues have linked a diminished belief in free will to stress, unhappiness, and a lesser commitment to relationships. They found that when subjects were induced to believe that “all human actions follow from prior events and ultimately can be understood in terms of the movement of molecules,” those subjects came away with a lower sense of life’s meaningfulness. Early this year, other researchers published a study showing that a weaker belief in free will correlates with poor academic performance.

The list goes on: Believing that free will is an illusion has been shown to make people less creative, more likely to conform, less willing to learn from their mistakes, and less grateful toward one another. In every regard, it seems, when we embrace determinism, we indulge our dark side.

Few scholars are comfortable suggesting that people ought to believe an outright lie. Advocating the perpetuation of untruths would breach their integrity and violate a principle that philosophers have long held dear: the Platonic hope that the true and the good go hand in hand. Saul Smilansky, a philosophy professor at the University of Haifa, in Israel, has wrestled with this dilemma throughout his career and come to a painful conclusion: “We cannot afford for people to internalize the truth” about free will.

Smilansky is convinced that free will does not exist in the traditional sense—and that it would be very bad if most people realized this. “Imagine,” he told me, “that I’m deliberating whether to do my duty, such as to parachute into enemy territory, or something more mundane like to risk my job by reporting on some wrongdoing. If everyone accepts that there is no free will, then I’ll know that people will say, ‘Whatever he did, he had no choice—we can’t blame him.’ So I know I’m not going to be condemned for taking the selfish option.” This, he believes, is very dangerous for society, and “the more people accept the determinist picture, the worse things will get.”

Determinism not only undermines blame, Smilansky argues; it also undermines praise. Imagine I do risk my life by jumping into enemy territory to perform a daring mission. Afterward, people will say that I had no choice, that my feats were merely, in Smilansky’s phrase, “an unfolding of the given,” and therefore hardly praiseworthy. And just as undermining blame would remove an obstacle to acting wickedly, so undermining praise would remove an incentive to do good. Our heroes would seem less inspiring, he argues, our achievements less noteworthy, and soon we would sink into decadence and despondency.

Smilansky advocates a view he calls illusionism—the belief that free will is indeed an illusion, but one that society must defend. The idea of determinism, and the facts supporting it, must be kept confined within the ivory tower. Only the initiated, behind those walls, should dare to, as he put it to me, “look the dark truth in the face.” Smilansky says he realizes that there is something drastic, even terrible, about this idea—but if the choice is between the true and the good, then for the sake of society, the true must go.

Smilansky’s arguments may sound odd at first, given his contention that the world is devoid of free will: If we are not really deciding anything, who cares what information is let loose? But new information, of course, is a sensory input like any other; it can change our behavior, even if we are not the conscious agents of that change. In the language of cause and effect, a belief in free will may not inspire us to make the best of ourselves, but it does stimulate us to do so.

Illusionism is a minority position among academic philosophers, most of whom still hope that the good and the true can be reconciled. But it represents an ancient strand of thought among intellectual elites. Nietzsche called free will “a theologians’ artifice” that permits us to “judge and punish.” And many thinkers have believed, as Smilansky does, that institutions of judgment and punishment are necessary if we are to avoid a fall into barbarism.

Smilansky is not advocating policies of Orwellian thought control . Luckily, he argues, we don’t need them. Belief in free will comes naturally to us. Scientists and commentators merely need to exercise some self-restraint, instead of gleefully disabusing people of the illusions that undergird all they hold dear. Most scientists “don’t realize what effect these ideas can have,” Smilansky told me. “Promoting determinism is complacent and dangerous.”

Yet not all scholars who argue publicly against free will are blind to the social and psychological consequences. Some simply don’t agree that these consequences might include the collapse of civilization. One of the most prominent is the neuroscientist and writer Sam Harris, who, in his 2012 book, Free Will , set out to bring down the fantasy of conscious choice. Like Smilansky, he believes that there is no such thing as free will. But Harris thinks we are better off without the whole notion of it.

“We need our beliefs to track what is true,” Harris told me. Illusions, no matter how well intentioned, will always hold us back. For example, we currently use the threat of imprisonment as a crude tool to persuade people not to do bad things. But if we instead accept that “human behavior arises from neurophysiology,” he argued, then we can better understand what is really causing people to do bad things despite this threat of punishment—and how to stop them. “We need,” Harris told me, “to know what are the levers we can pull as a society to encourage people to be the best version of themselves they can be.”

According to Harris, we should acknowledge that even the worst criminals—murderous psychopaths, for example—are in a sense unlucky. “They didn’t pick their genes. They didn’t pick their parents. They didn’t make their brains, yet their brains are the source of their intentions and actions.” In a deep sense, their crimes are not their fault. Recognizing this, we can dispassionately consider how to manage offenders in order to rehabilitate them, protect society, and reduce future offending. Harris thinks that, in time, “it might be possible to cure something like psychopathy,” but only if we accept that the brain, and not some airy-fairy free will, is the source of the deviancy.

Accepting this would also free us from hatred. Holding people responsible for their actions might sound like a keystone of civilized life, but we pay a high price for it: Blaming people makes us angry and vengeful, and that clouds our judgment.

“Compare the response to Hurricane Katrina,” Harris suggested, with “the response to the 9/11 act of terrorism.” For many Americans, the men who hijacked those planes are the embodiment of criminals who freely choose to do evil. But if we give up our notion of free will, then their behavior must be viewed like any other natural phenomenon—and this, Harris believes, would make us much more rational in our response.

Although the scale of the two catastrophes was similar, the reactions were wildly different. Nobody was striving to exact revenge on tropical storms or declare a War on Weather, so responses to Katrina could simply focus on rebuilding and preventing future disasters. The response to 9/11 , Harris argues, was clouded by outrage and the desire for vengeance, and has led to the unnecessary loss of countless more lives. Harris is not saying that we shouldn’t have reacted at all to 9/11, only that a coolheaded response would have looked very different and likely been much less wasteful. “Hatred is toxic,” he told me, “and can destabilize individual lives and whole societies. Losing belief in free will undercuts the rationale for ever hating anyone.”

Whereas the evidence from Kathleen Vohs and her colleagues suggests that social problems may arise from seeing our own actions as determined by forces beyond our control—weakening our morals, our motivation, and our sense of the meaningfulness of life—Harris thinks that social benefits will result from seeing other people’s behavior in the very same light. From that vantage point, the moral implications of determinism look very different, and quite a lot better.

What’s more, Harris argues, as ordinary people come to better understand how their brains work, many of the problems documented by Vohs and others will dissipate. Determinism, he writes in his book, does not mean “that conscious awareness and deliberative thinking serve no purpose.” Certain kinds of action require us to become conscious of a choice—to weigh arguments and appraise evidence. True, if we were put in exactly the same situation again, then 100 times out of 100 we would make the same decision, “just like rewinding a movie and playing it again.” But the act of deliberation—the wrestling with facts and emotions that we feel is essential to our nature—is nonetheless real.

The big problem, in Harris’s view, is that people often confuse determinism with fatalism. Determinism is the belief that our decisions are part of an unbreakable chain of cause and effect. Fatalism, on the other hand, is the belief that our decisions don’t really matter, because whatever is destined to happen will happen—like Oedipus’s marriage to his mother, despite his efforts to avoid that fate.

When people hear there is no free will, they wrongly become fatalistic; they think their efforts will make no difference. But this is a mistake. People are not moving toward an inevitable destiny; given a different stimulus (like a different idea about free will), they will behave differently and so have different lives. If people better understood these fine distinctions, Harris believes, the consequences of losing faith in free will would be much less negative than Vohs’s and Baumeister’s experiments suggest.

Can one go further still? Is there a way forward that preserves both the inspiring power of belief in free will and the compassionate understanding that comes with determinism?

Philosophers and theologians are used to talking about free will as if it is either on or off; as if our consciousness floats, like a ghost, entirely above the causal chain, or as if we roll through life like a rock down a hill. But there might be another way of looking at human agency.

Some scholars argue that we should think about freedom of choice in terms of our very real and sophisticated abilities to map out multiple potential responses to a particular situation. One of these is Bruce Waller, a philosophy professor at Youngstown State University. In his new book, Restorative Free Will , he writes that we should focus on our ability, in any given setting, to generate a wide range of options for ourselves, and to decide among them without external constraint.

For Waller, it simply doesn’t matter that these processes are underpinned by a causal chain of firing neurons. In his view, free will and determinism are not the opposites they are often taken to be; they simply describe our behavior at different levels.

Waller believes his account fits with a scientific understanding of how we evolved: Foraging animals—humans, but also mice, or bears, or crows—need to be able to generate options for themselves and make decisions in a complex and changing environment. Humans, with our massive brains, are much better at thinking up and weighing options than other animals are. Our range of options is much wider, and we are, in a meaningful way, freer as a result.

Waller’s definition of free will is in keeping with how a lot of ordinary people see it. One 2010 study found that people mostly thought of free will in terms of following their desires, free of coercion (such as someone holding a gun to your head). As long as we continue to believe in this kind of practical free will, that should be enough to preserve the sorts of ideals and ethical standards examined by Vohs and Baumeister.

Yet Waller’s account of free will still leads to a very different view of justice and responsibility than most people hold today. No one has caused himself: No one chose his genes or the environment into which he was born. Therefore no one bears ultimate responsibility for who he is and what he does. Waller told me he supported the sentiment of Barack Obama’s 2012 “You didn’t build that” speech, in which the president called attention to the external factors that help bring about success. He was also not surprised that it drew such a sharp reaction from those who want to believe that they were the sole architects of their achievements. But he argues that we must accept that life outcomes are determined by disparities in nature and nurture, “so we can take practical measures to remedy misfortune and help everyone to fulfill their potential.”

Understanding how will be the work of decades, as we slowly unravel the nature of our own minds. In many areas, that work will likely yield more compassion: offering more (and more precise) help to those who find themselves in a bad place. And when the threat of punishment is necessary as a deterrent, it will in many cases be balanced with efforts to strengthen, rather than undermine, the capacities for autonomy that are essential for anyone to lead a decent life. The kind of will that leads to success—seeing positive options for oneself, making good decisions and sticking to them—can be cultivated, and those at the bottom of society are most in need of that cultivation.

To some people, this may sound like a gratuitous attempt to have one’s cake and eat it too. And in a way it is. It is an attempt to retain the best parts of the free-will belief system while ditching the worst. President Obama—who has both defended “a faith in free will” and argued that we are not the sole architects of our fortune—has had to learn what a fine line this is to tread. Yet it might be what we need to rescue the American dream—and indeed, many of our ideas about civilization, the world over—in the scientific age.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 13 May 2009

Is free will an illusion?

- Martin Heisenberg 1

Nature volume 459 , pages 164–165 ( 2009 ) Cite this article

14k Accesses

58 Citations

66 Altmetric

Metrics details

Scientists and philosophers are using new discoveries in neuroscience to question the idea of free will. They are misguided, says Martin Heisenberg. Examining animal behaviour shows how our actions can be free.

You have full access to this article via your institution.

Our influence on the future is something we take for granted as much as breathing. We accept that what will be is not yet determined, and that we can steer the course of events in one direction or another. This idea of freedom, and the sense of responsibility it bestows, seems essential to day-to-day existence.

Yet it is under attack as never before. Some scientists and philosophers argue that recent findings in neuroscience — such as data published last year suggesting that our brain makes decisions up to seven seconds before we become aware of them — along with the philosophical principle that any action must be dependent on preceding causes, imply that our behaviour is never self-generated and that freedom is an illusion 1 , 2 , 3 .

This debate has focused on humans and 'conscious free will'. Yet when it comes to understanding how we initiate behaviour, we can learn a lot by looking at animals. Although we do not credit animals with anything like the consciousness in humans, researchers have found that animal behaviour is not as involuntary as it may appear. The idea that animals act only in response to external stimuli has long been abandoned, and it is well established that they initiate behaviour on the basis of their internal states, as we do.

Before going into behaviour, I would like to take a step back and look at the nature of freedom and determinism at a more fundamental level. Almost 100 years ago, quantum physics eliminated a major obstacle to our understanding of this issue when it disposed of the idea of a Universe determined in every detail from the outset. It uncovered an inherent unpredictability in nature, in that we can never know precisely at a given moment all properties of a particle — such as both its position and its momentum.

How is this reflected at the level of everyday experience? At the scale of planets, quantum effects give way to the deterministic laws of classical mechanics. At an intermediate scale, however, they are occasionally amplified to become observable, for example when we measure radioactive decay. In general, life is an interplay between the deterministic and the random. There is plenty of evidence of chance at work in the brain: take the random opening and closing of ion channels in the neuronal membrane, or the miniature potentials of randomly discharging synaptic vesicles. Behaviour that is triggered by random events in the brain can be said to be truly 'active' — in other words, it has the quality of a beginning.

Evidence of randomly generated action — action that is distinct from reaction because it does not depend upon external stimuli — can be found in unicellular organisms. Take the way the bacterium Escherichia coli moves. It has a flagellum that can rotate around its longitudinal axis in either direction: one way drives the bacterium forward, the other causes it to tumble at random so that it ends up facing in a new direction ready for the next phase of forward motion. This 'random walk' can be modulated by sensory receptors, enabling the bacterium to find food and the right temperature.

What this tells us is that behavioural output can be independent of sensory input. This is in line with the fact that in the early development of individual organisms the motor system slightly precedes the sensory system. The same may have been true in evolution, as merely being dispersed in space should have been advantageous and should have favoured mobility.

What of more complex behaviour? With the emergence of multicellularity, individual cells lost their behavioural autonomy and organisms had to reinvent locomotion. Behaviours in complex organisms typically come in modules: the grasp reflex of the newborn, the syllables of birdsong, the rhythmic motion of the legs during walking. Some modules, such as the heartbeat, last from embryonic development until death; others, such as the snapping of a crocodile's jaw, last just fractions of a second. Some can take place in parallel, like walking and singing; others are mutually exclusive, such as sleeping and playing the piano. Some necessarily follow one another, like flight and landing. From beginning to end, the lives of animals and humans are an ongoing interweaving of these behavioural modules.

There is plenty of evidence that an animal's behaviour cannot be reduced to responses.

As with a bacterium's locomotion, the activation of behavioural modules is based on the interplay between chance and lawfulness in the brain. Insufficiently equipped, insufficiently informed and short of time, animals have to find a module that is adaptive. Their brains, in a kind of random walk, continuously pre-activate, discard and reconfigure their options, and evaluate their possible short-term and long-term consequences.

The physiology of how this happens has been little investigated. But there is plenty of evidence that an animal's behaviour cannot be reduced to responses. For example, my lab has demonstrated that fruit flies, in situations they have never encountered, can modify their expectations about the consequences of their actions. They can solve problems that no individual fly in the evolutionary history of the species has solved before. Our experiments show that they actively initiate behaviour 4 . Like humans who can paint with their toes, we have found that flies can be made to use several different motor outputs to escape a life-threatening danger or to visually stabilize their orientation in space 5 .

Does this tell us anything about freedom in human behaviour? Before I answer that, let's establish what I mean by freedom. One acknowledged definition comes from Immanuel Kant, who resolved that a person acts freely if he does of his own accord what must be done. Thus, my actions are not free if they are determined by something or someone else. As stated above, self-initiated action is not in conflict with physics and can be demonstrated in animals. So, humans can be considered free in their behaviour, in as much as their behaviour is self-initiated and adaptive.

Some define freedom as the ability to consciously decide how to act. I maintain that we need not be conscious of our decision-making to be free. What matters is that our actions are self-generated. Conscious awareness may help improve our behaviour, but it does not necessarily do so and is not essential. Why should an action become free from one moment to the next simply because we reflect upon it?

Kant's famous 'Third Antinomy' in his Critique of Pure Reason (1781) sees us on the one hand determined by natural law and on the other free because of our capacity to obey moral law. He would have been delighted to see this dilemma solved by quantum physics and behavioural biology.

Soon, C. S. Nature Neurosci. 11 , 543–545 (2008).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Libet, B. Behav. Brain Sci. 8 , 529–566 (1985).

Article Google Scholar

Wegner, D. M. The Illusion of Conscious Will (MIT Press, 2002).

Book Google Scholar

Heisenberg, M. Naturwissenschaften 70 , 70–78 (1983).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

Heisenberg, M. & Wolf, R. Vision in Drosophila in Studies of Brain Function Vol. XII , (ed. Braitenberg, V.) (Springer, 1984).

Google Scholar

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Martin Heisenberg is professor emeritus in the department of biology at the University of Würzburg, Germany. [email protected],

Martin Heisenberg

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Heisenberg, M. Is free will an illusion?. Nature 459 , 164–165 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/459164a

Download citation

Published : 13 May 2009

Issue Date : 14 May 2009

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/459164a

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Evolutionary perspective on human cognitive architecture in cognitive load theory: a dynamic, emerging principle approach.

- Slava Kalyuga

Educational Psychology Review (2023)

Austrian Economics and Compatibilist Freedom

- Igor Wysocki

- Łukasz Dominiak

Journal for General Philosophy of Science (2023)

Consciousness, decision making, and volition: freedom beyond chance and necessity

- Hans Liljenström

Theory in Biosciences (2022)

Can Reasons and Values Influence Action: How Might Intentional Agency Work Physiologically?

- Raymond Noble

- Denis Noble

Journal for General Philosophy of Science (2021)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

January 16, 2023

Free Will Is Only an Illusion if You Are, Too

New research findings, combined with philosophy, suggest free will is real but may not operate in the ways people expect

By Alessandra Buccella & Tomáš Dominik

francescoch/Getty Images

Imagine you are shopping online for a new pair of headphones. There is an array of colors, brands and features to look at. You feel that you can pick any model that you like and are in complete control of your decision. When you finally click the “add to shopping cart” button, you believe that you are doing so out of your own free will.

But what if we told you that while you thought that you were still browsing, your brain activity had already highlighted the headphones you would pick? That idea may not be so far-fetched. Though neuroscientists likely could not predict your choice with 100 percent accuracy, research has demonstrated that some information about your upcoming action is present in brain activity several seconds before you even become conscious of your decision.

As early as the 1960s, studies found that when people perform a simple, spontaneous movement, their brain exhibits a buildup in neural activity —what neuroscientists call a “readiness potential”—before they move. In the 1980s, neuroscientist Benjamin Libet reported this readiness potential even preceded a person’s reported intention to move, not just their movement. In 2008 a group of researchers found that some information about an upcoming decision is present in the brain up to 10 seconds in advance , long before people reported making the decision of when or how to act.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

These studies have sparked questions and debates . To many observers, these findings debunked the intuitive concept of free will. After all, if neuroscientists can infer the timing or choice of your movements long before you are consciously aware of your decision, perhaps people are merely puppets, pushed around by neural processes unfolding below the threshold of consciousness.

But as researchers who study volition from both a neuroscientific and philosophical perspective, we believe that there’s still much more to this story. We work with a collaboration of philosophers and scientists to provide more nuanced interpretations—including a better understanding of the readiness potential —and a more fruitful theoretical framework in which to place them. The conclusions suggest “free will” remains a useful concept, although people may need to reexamine how they define it.

Let’s start from a commonsense observation: much of what people do each day is arbitrary. We put one foot in front of the other when we start walking. Most of the time, we do not actively deliberate about which leg to put forward first. It doesn’t matter. The same is true for many other actions and choices. They are largely meaningless and irreflective.

Most empirical studies of free will—including Libet’s—have focused on these kinds of arbitrary actions. In such actions, researchers can indeed “read out” our brain activity and trace information about our movements and choices before we even realize we are about to make them. But if these actions don’t matter to us, is it all that notable that they are initiated unconsciously? More significant decisions—such as whether to take a job, get married or move to a different country—are infinitely more interesting and complex and are quite consciously made.

If we start working with a more philosophically grounded understanding of free will, we realize that only a small subset of our everyday actions is important enough to worry about. We want to feel in control of those decisions, the ones whose outcomes make a difference in our life and whose responsibility we feel on our shoulders. It is in this context—decisions that matter —that the question of free will most naturally applies.

In 2019 neuroscientists Uri Maoz, Liad Mudrik and their colleagues investigated that idea. They presented participants with a choice of two nonprofit organizations to which they could donate $1,000. People could indicate their preferred organization by pressing the left or right button. In some cases, participants knew that their choice mattered because the button would determine which organization would receive the full $1,000. In other cases, people knowingly made meaningless choices because they were told that both organizations would receive $500 regardless of their selection. The results were somewhat surprising. Meaningless choices were preceded by a readiness potential, just as in previous experiments. Meaningful choices were not , however. When we care about a decision and its outcome, our brain appears to behave differently than when a decision is arbitrary.

Even more interesting is the fact that ordinary people’s intuitions about free will and decision-making do not seem consistent with these findings. Some of our colleagues, including Maoz and neuroscientist Jake Gavenas, recently published the results of a large survey, with more than 600 respondents, in which they asked people to rate how “free” various choices made by others seemed. Their ratings suggested that people do not recognize that the brain may handle meaningful choices in a different way from more arbitrary or meaningless ones. People tend, in other words, to imagine all their choices—from which sock to put on first to where to spend a vacation—as equally “free,” even though neuroscience suggests otherwise.

What this tells us is that free will may exist, but it may not operate in the way we intuitively imagine. In the same vein, there is a second intuition that must be addressed to understand studies of volition. When experiments have found that brain activity, such as the readiness potential, precedes the conscious intention to act, some people have jumped to the conclusion that they are “not in charge.” They do not have free will, they reason, because they are somehow subject to their brain activity.

But that assumption misses a broader lesson from neuroscience. “We” are our brain. The combined research makes clear that human beings do have the power to make conscious choices. But that agency and accompanying sense of personal responsibility are not supernatural. They happen in the brain, regardless of whether scientists observe them as clearly as they do a readiness potential.

So there is no “ghost” inside the cerebral machine. But as researchers, we argue that this machinery is so complex, inscrutable and mysterious that popular concepts of “free will” or the “self” remain incredibly useful. They help us think through and imagine—albeit imperfectly—the workings of the mind and brain. As such, they can guide and inspire our investigations in profound ways—provided we continue to question and test these assumptions along the way.

Are you a scientist who specializes in neuroscience, cognitive science or psychology? And have you read a recent peer-reviewed paper that you would like to write about for Mind Matters? Please send suggestions to Scientific American ’s Mind Matters editor Daisy Yuhas at [email protected] .

“Free Will” is a philosophical term of art for a particular sort of capacity of rational agents to choose a course of action from among various alternatives. Which sort is the free will sort is what all the fuss is about. (And what a fuss it has been: philosophers have debated this question for over two millenia, and just about every major philosopher has had something to say about it.) Most philosophers suppose that the concept of free will is very closely connected to the concept of moral responsibility. Acting with free will, on such views, is just to satisfy the metaphysical requirement on being responsible for one's action. (Clearly, there will also be epistemic conditions on responsibility as well, such as being aware—or failing that, being culpably unaware—of relevant alternatives to one's action and of the alternatives' moral significance.) But the significance of free will is not exhausted by its connection to moral responsibility. Free will also appears to be a condition on desert for one's accomplishments (why sustained effort and creative work are praiseworthy); on the autonomy and dignity of persons; and on the value we accord to love and friendship. (See Kane 1996, 81ff. and Clarke 2003, Ch.1.)

Philosophers who distinguish freedom of action and freedom of will do so because our success in carrying out our ends depends in part on factors wholly beyond our control. Furthermore, there are always external constraints on the range of options we can meaningfully try to undertake. As the presence or absence of these conditions and constraints are not (usually) our responsibility, it is plausible that the central loci of our responsibility are our choices, or “willings.”

I have implied that free willings are but a subset of willings, at least as a conceptual matter. But not every philosopher accepts this. René Descartes, for example, identifies the faculty of will with freedom of choice, “the ability to do or not do something” (Meditation IV), and even goes so far as to declare that “the will is by its nature so free that it can never be constrained” (Passions of the Soul, I, art. 41). In taking this strong polar position on the nature of will, Descartes is reflecting a tradition running through certain late Scholastics (most prominently, Suarez) back to John Duns Scotus.