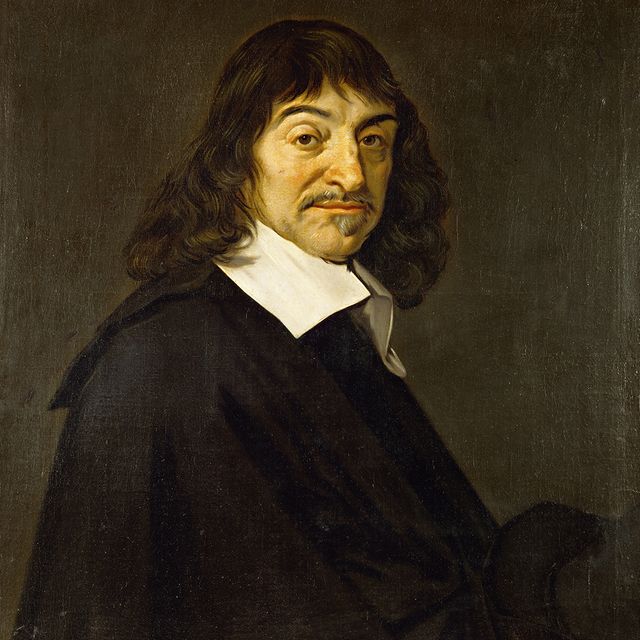

René Descartes

Philosopher and mathematician René Descartes is regarded as the father of modern philosophy for defining a starting point for existence, “I think; therefore I am.”

(1596-1650)

Who Was René Descartes?

René Descartes was extensively educated, first at a Jesuit college at age 8, then earning a law degree at 22, but an influential teacher set him on a course to apply mathematics and logic to understanding the natural world. This approach incorporated the contemplation of the nature of existence and of knowledge itself, hence his most famous observation, “I think; therefore I am.”

Descartes was born on March 31, 1596, in La Haye en Touraine, a small town in central France, which has since been renamed after him to honor its most famous son. He was the youngest of three children, and his mother, Jeanne Brochard, died within his first year of life. His father, Joachim, a council member in the provincial parliament, sent the children to live with their maternal grandmother, where they remained even after he remarried a few years later. But he was very concerned with good education and sent René, at age 8, to boarding school at the Jesuit college of Henri IV in La Flèche, several miles to the north, for seven years.

Descartes was a good student, although it is thought that he might have been sickly, since he didn’t have to abide by the school’s rigorous schedule and was instead allowed to rest in bed until midmorning. The subjects he studied, such as rhetoric and logic and the “mathematical arts,” which included music and astronomy, as well as metaphysics, natural philosophy and ethics, equipped him well for his future as a philosopher. So did spending the next four years earning a baccalaureate in law at the University of Poitiers. Some scholars speculate that he may have had a nervous breakdown during this time.

Descartes later added theology and medicine to his studies. But he eschewed all this, “resolving to seek no knowledge other than that of which could be found in myself or else in the great book of the world,” he wrote much later in Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting the Reason and Seeking Truth in the Sciences , published in 1637.

So he traveled, joined the army for a brief time, saw some battles and was introduced to Dutch scientist and philosopher Isaac Beeckman, who would become for Descartes a very influential teacher. A year after graduating from Poitiers, Descartes credited a series of three very powerful dreams or visions with determining the course of his study for the rest of his life.

Becoming the Father of Modern Philosophy

Descartes is considered by many to be the father of modern philosophy, because his ideas departed widely from current understanding in the early 17th century, which was more feeling-based. While elements of his philosophy weren’t completely new, his approach to them was. Descartes believed in basically clearing everything off the table, all preconceived and inherited notions, and starting fresh, putting back one by one the things that were certain, which for him began with the statement “I exist.” From this sprang his most famous quote: “I think; therefore I am.”

Since Descartes believed that all truths were ultimately linked, he sought to uncover the meaning of the natural world with a rational approach, through science and mathematics—in some ways an extension of the approach Sir Francis Bacon had asserted in England a few decades prior. In addition to Discourse on the Method , Descartes also published Meditations on First Philosophy and Principles of Philosophy , among other treatises.

Although philosophy is largely where the 20th century deposited Descartes—each century has focused on different aspects of his work—his investigations in theoretical physics led many scholars to consider him a mathematician first. He introduced Cartesian geometry, which incorporates algebra; through his laws of refraction, he developed an empirical understanding of rainbows; and he proposed a naturalistic account of the formation of the solar system, although he felt he had to suppress much of that due to Galileo’s fate at the hands of the Inquisition. His concern wasn’t misplaced—Pope Alexander VII later added Descartes’ works to the Index of Prohibited Books.

Later Life, Death and Legacy

Descartes never married, but he did have a daughter, Francine, born in the Netherlands in 1635. He had moved to that country in 1628 because life in France was too bustling for him to concentrate on his work, and Francine’s mother was a maid in the home where he was staying. He had planned to have the little girl educated in France, having arranged for her to live with relatives, but she died of a fever at age 5.

Descartes lived in the Netherlands for more than 20 years but died in Stockholm, Sweden, on February 11, 1650. He had moved there less than a year before, at the request of Queen Christina, to be her philosophy tutor. The fragile health indicated in his early life persisted. He habitually spent mornings in bed, where he continued to honor his dream life, incorporating it into his waking methodologies in conscious meditation, but the queen’s insistence on 5 am lessons led to a bout of pneumonia from which he could not recover. He was 53.

Sweden was a Protestant country, so Descartes, a Catholic, was buried in a graveyard primarily for unbaptized babies. Later, his remains were taken to the abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, the oldest church in Paris. They were moved during the French Revolution, and were put back later—although urban legend has it that only his heart is there and the rest is buried in the Panthéon.

Descartes’ approach of combining mathematics and logic with philosophy to explain the physical world turned metaphysical when confronted with questions of theology; it led him to a contemplation of the nature of existence and the mind-body duality, identifying the point of contact for the body with the soul at the pineal gland. It also led him to define the idea of dualism: matter meeting non-matter. Because his previous philosophical system had given man the tools to define knowledge of what is true, this concept led to controversy. Fortunately, Descartes himself had also invented methodological skepticism, or Cartesian doubt, thus making philosophers of us all.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: René Descartes

- Birth Year: 1596

- Birth date: March 31, 1596

- Birth City: La Haye, Touraine

- Birth Country: France

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Philosopher and mathematician René Descartes is regarded as the father of modern philosophy for defining a starting point for existence, “I think; therefore I am.”

- Education and Academia

- Writing and Publishing

- Journalism and Nonfiction

- Astrological Sign: Aries

- Jesuit College of Henri IV

- University of Poitiers

- Nacionalities

- Death Year: 1650

- Death date: February 11, 1650

- Death City: Stockholm

- Death Country: Sweden

- I think; therefore I am." ("Cogito ergo sum.")

- It is not enough to have a good mind; the main thing is to use it well.

- If you would be a real seeker after truth, it is necessary that at least once in your life you doubt, as far as possible, all things.

Philosophers

Francis Bacon

Auguste Comte

Charles-Louis de Secondat

Saint Thomas Aquinas

William James

John Stuart Mill

Jean-Paul Sartre

Biography Online

Rene Descartes biography

Early Life Rene Descartes

Rene Descartes was born in La Haye en Touraine, France on 31 March 1596. His family were Roman Catholics, though they lived in a Protestant Huguenots area of Poitou. His mother died when he was one year old, and he was brought up by his grandmother and great uncle.

The young Descartes studied at a Jesuit College in La Flèche, where he received a modern education, including maths, physics and the recent works of Galileo. After college, he studied at the University of Poitiers to gain a degree in law.

In 1616, he travelled to Paris in order to practise as a lawyer – according to the wishes of his father. But, Descartes was restless in practising law, he travelled frequently seeking to gain a variety of experiences. In 1618, he joined the Dutch States Army in Breda, where he concentrated on the study of military engineering, which included more study of mathematics.

Visions of a new philosophy

In November 1619, while Descartes was stationed in Neuburg an der Donau, he stated that he received heavenly visions, while he was shut in his room. He felt a divine spirit had infused his mind with the vision of a new philosophy and also the idea of combining mathematics and philosophy.

Descartes had always sought to be independently minded – never relying on books he read; this vision increased his independence of thought and is a characteristic aspect of his philosophy and mathematical work.

In 1620, Descartes left the army and visited several countries before returning to France. He was now motivated to write his own philosophical treatises. His first work was Regulae ad directionem ingenii (1928) Rules for the Direction of the Mind . It set out some of Descartes principles for philosophy and the sciences. In particular, it expressed the importance of relying on reason and the use of mental faculties to methodically work out the truth.

Rule III states:

“As regards any subject we propose to investigate, we must inquire not what other people have thought, or what we ourselves conjecture, but what we can clearly and manifestly perceive by intuition or deduce with certainty.”

– Rene Descartes

Descartes frequently moved in his early years, but he came to settle in the Netherlands, and it was here that he did most of his writings. As well as philosophy, Descartes continued his mathematical studies. He enrolled in Leiden University and studied mathematics and astronomy.

Discourse on the Method

In 1637, Descartes published some of his most important works, including Discours de la méthode . This stated, with Descartes’ characteristic clarity, the importance of methodically never accepting anything as true – which had not been properly examined.

Although Descartes remained a committed Catholic throughout his life, his writings were still controversial for the time period. In 1633, Galileo’s works were put on the prohibited list, and his own Cartesian philosophy was condemned at the University of Utrecht. In 1663, shortly after his death, his works were placed on the Index of Prohibited Works by the Pope.

Ironically, Descartes claimed his meditations were aimed to defend the Catholic faith – through the use of reason and not just relying on faith. However in retrospective, many believe Descartes’ willingness to start with doubt, marked an important shift in philosophy and religious faith. No longer was Descartes stating that the authority of the church and scripture should be assumed – Descartes shifted the proof of truth onto human reason; this was a very influential aspect of the Enlightenment and marked an erosion of authority by the Church.

Descartes willingness to doubt the existence of God led many contemporaries to doubt his real faith. Some believed Descartes might have been a secret Deist, who gave the impression of being a committed Catholic for practical reasons. A biographer of Descartes, Gaukroger states that Descartes remained a committed Catholic throughout his life – but, he had a complementary desire to discover the truth through reason.

Moral Philosophy

Queen Christina of Sweden and Rene Descartes

Descartes wrote on a variety of subjects, relating to philosophy. In 1649, he published 1649 Les Passions de l’âme (Passions of the Soul) a work which sprung from a long correspondence with Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia concerning issues of morality and psychology. This work led to Descartes being invited to the Royal Court of Sweden by Queen Christina.

In 1650, Descartes reluctantly travelled to Sweden and gave the Queen several philosophy lessons early in the morning. However, it was not a success; there was a lack of understanding between the two. More seriously, in the cold castle, Descartes contracted a form of pneumonia, and he died shortly later on 11 February 1650.

Personal life

He had a relationship with a servant girl Helena Jans van der Strom. With Helena, he fathered a child and was distraught when she died in 1640.

Descartes pioneered a new approach to modern philosophy, which was different from the preceding Aristotelian approach. Descartes took great pride in stating that his conclusions were reached from his own deduction and not relying on the works of others.

Descartes methodology of philosophy involved beginning with a metaphysical doubt about everything and from this basis of ‘being unsure of anything’ – seeing what he could prove to be true.

Cogito ergo Sum (“I think therefore I am”)

From this basis of doubt, Descartes started by deducting that the first thing he could be sure of was his own thoughts. If he was doubting, then there must be someone doing the doubting. It is this that led to his famous dictum Cogito Ergo Sum (“I think therefore I am”). Descartes believed that it was only his capacity to think and deduction that was reliable – he believed relying on the senses were open to doubt.

From this premise, Descartes was able to offer an ontological proof of a benevolent God Descartes believed that the idea of God’s existence was immediately inferable from a “clear and distinct” idea of a supremely perfect being.

An aspect of Descartes philosophy was the distinction of the mind (or soul) and body. Descartes wrote how the mind could control the body and vice versa.

From Descartes’ philosophy, he later developed a form of moral philosophy which were effective for functioning in the real world. This involved obeying laws and customs of the country in which he lived, avoiding extremes and adopting practices which were judicious to those around you. His third principle expresses the importance he attached to controlling the mind and desires.

“Endeavor always to conquer myself rather than fortune, and change my desires rather than the order of the world, and in general, accustom myself to the persuasion that, except our own thoughts, there is nothing absolutely in our power; so that when we have done our best in things external to us, our ill-success cannot possibly be failure on our part.”

Rene Descartes, Discourse on the Method, Chapter III

Mathematics

Descartes developed Cartesian or analytic geometry, which uses algebra to describe geometry. His work on algebra was influential in the later work of Isaac Newton (on calculus and cubic equations) and Gottfried Leibniz (infinitesimal calculus).

Descartes was also a polymath, who also investigated a wide range of fields, including optics, astronomy and music.

Major works of Descartes include

1618. Musicae Compendium. – a work on the aesthetics of music

1626–1628. Regulae ad directionem ingenii (Rules for the Direction of the Mind).

1637. Discours de la méthode (Discourse on the Method).

1637. La Géométrie (Geometry).

1641. Meditationes de Prima Philosophia (Meditations on First Philosophy),

1644. Principia Philosophiae (Principles of Philosophy)

1649. Les passions de l’âme (Passions of the Soul). Dedicated to Princess Elisabeth of the Palatinate.

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “Biography of Rene Descartes”, Oxford, www.biographyonline.net 31 March 2015.

Rene Descartes – Meditations and Other Metaphysical Writings

Rene Descartes – Meditations and Other Metaphysical Writings at Amazon

Rene Descartes – Biography

Rene Descartes -Biography at Amazon

Related pages

One Comment

thank you i love this site it is really helpful

- October 23, 2016 4:31 AM

- By person thats a mouse

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

René descartes (1596—1650).

Descartes attempted to address the former issue via his method of doubt. His basic strategy was to consider false any belief that falls prey to even the slightest doubt. This “hyperbolic doubt” then serves to clear the way for what Descartes considers to be an unprejudiced search for the truth . This clearing of his previously held beliefs then puts him at an epistemological ground-zero. From here Descartes sets out to find something that lies beyond all doubt. He eventually discovers that “I exist” is impossible to doubt and is, therefore, absolutely certain. It is from this point that Descartes proceeds to demonstrate God ’s existence and that God cannot be a deceiver. This, in turn, serves to fix the certainty of everything that is clearly and distinctly understood and provides the epistemological foundation Descartes set out to find.

Once this conclusion is reached, Descartes can proceed to rebuild his system of previously dubious beliefs on this absolutely certain foundation. These beliefs, which are re-established with absolute certainty, include the existence of a world of bodies external to the mind, the dualistic distinction of the immaterial mind from the body, and his mechanistic model of physics based on the clear and distinct ideas of geometry. This points toward his second, major break with the Scholastic Aristotelian tradition in that Descartes intended to replace their system based on final causal explanations with his system based on mechanistic principles. Descartes also applied this mechanistic framework to the operation of plant, animal and human bodies, sensation and the passions. All of this eventually culminating in a moral system based on the notion of “generosity.”

The presentation below provides an overview of Descartes’ philosophical thought as it relates to these various metaphysical, epistemological, religious, moral and scientific issues, covering the wide range of his published works and correspondence.

Table of Contents

- Against Scholasticism

- Descartes’ Project

- Cogito, ergo sum

- The Nature of the Mind and its Ideas

- The Causal Arguments

- The Ontological Argument

- Absolute Certainty and the Cartesian Circle

- How to Avoid Error

- The Real Distinction

- The Mind-Body Problem

- Existence of the External World

- The Nature of Body

- Animal and Human Bodies

- Sensations and Passions

- The Provisional Moral Code

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

René Descartes was born to Joachim Descartes and Jeanne Brochard on March 31, 1596 in La Haye, France near Tours. He was the youngest of the couple’s three surviving children. The oldest child, Pierre, died soon after his birth on October 19, 1589. His sister, Jeanne, was probably born sometime the following year, while his surviving older brother, also named Pierre, was born on October 19, 1591. The Descartes clan was a bourgeois family composed of mostly doctors and some lawyers. Joachim Descartes fell into this latter category and spent most of his career as a member of the provincial parliament.

After the death of their mother, which occurred soon after René’s birth, the three Descartes children were sent to their maternal grandmother, Jeanne Sain, to be raised in La Haye and remained there even after their father remarried in 1600. Not much is known about his early childhood, but René is thought to have been a sickly and fragile child, so much so that when he was sent to board at the Jesuit college at La Fleche on Easter of 1607. There, René was not obligated to rise at 5:00am with the other boys for morning prayers but was allowed to rest until 10:00am mass. At La Fleche, Descartes completed the usual courses of study in grammar and rhetoric and the philosophical curriculum with courses in the “verbal arts” of grammar, rhetoric and dialectic (or logic) and the “mathematical arts” comprised of arithmetic, music, geometry and astronomy. The course of study was capped off with courses in metaphysics, natural philosophy and ethics. Descartes is known to have disdained the impractical subjects despite having an affinity for the mathematical curriculum. But, all things considered, he did receive a very broad liberal arts education before leaving La Fleche in 1614.

Little is known of Descartes’ life from 1614-1618. But what is known is that during 1615-1616 he received a degree and a license in civil and canon law at the University of Poiters. However, some speculate that from 1614-1615 Descartes suffered a nervous breakdown in a house outside of Paris and that he lived in Paris from 1616-1618. The story picks up in the summer of 1618 when Descartes went to the Netherlands to become a volunteer for the army of Maurice of Nassau. It was during this time that he met Isaac Beekman, who was, perhaps, the most important influence on his early adulthood. It was Beekman who rekindled Descartes’ interest in science and opened his eyes to the possibility of applying mathematical techniques to other fields. As a New Year’s gift to Beekman, Descartes composed a treatise on music, which was then considered a branch of mathematics, entitled Compendium Musicae . In 1619 Descartes began serious work on mathematical and mechanical problems under Beekman’s guidance and, finally, left the service of Maurice of Nassau, planning to travel through Germany to join the army of Maximilian of Bavaria.

It is during this year (1619) that Descartes was stationed at Ulm and had three dreams that inspired him to seek a new method for scientific inquiry and to envisage a unified science. Soon afterwards, in 1620, he began looking for this new method, starting but never completing several works on method, including drafts of the first eleven rules of Rules for the Direction of the Mind . Descartes worked on and off on it for years until it was finally abandoned for good in 1628. During this time, he also worked on other, more scientifically oriented projects such as optics. In the course of these inquiries, it is possible that he discovered the law of refraction as early as 1626. It is also during this time that Descartes had regular contact with Father Marin Mersenne, who was to become his long time friend and contact with the intellectual community during his 20 years in the Netherlands.

Descartes moved to the Netherlands in late 1628 and, despite several changes of address and a few trips back to France, he remained there until moving to Sweden at the invitation of Queen Christina in late 1649. He moved to the Netherlands in order to achieve solitude and quiet that he could not attain with all the distractions of Paris and the constant intrusion of visitors. It is here in 1629 that Descartes began work on “a little treatise,” which took him approximately three years to complete, entitled The World . This work was intended to show how mechanistic physics could explain the vast array of phenomena in the world without reference to the Scholastic principles of substantial forms and real qualities, while also asserting a heliocentric conception of the solar system. But the condemnation of Galileo by the Inquisition for maintaining this latter thesis led Descartes to suppress its publication. From 1634-1636, Descartes finished his scientific essays Dioptique and Meteors , which apply his geometrical method to these fields. He also wrote a preface to these essays in the winter of 1635/1636 to be attached to them in addition to another one on geometry. This “preface” became The Discourse on Method and was published in French along with the three essays in June 1637. And, on a personal note, during this time his daughter, Francine, was born in 1635, her mother being a maid at the home where Descartes was staying. But Francine, at the age of five, died of a fever in 1640 when he was making arrangements for her to live with relatives in France so as to ensure her education.

Descartes began work on Meditations on First Philosophy in 1639. Through Mersenne, Descartes solicited criticism of his Meditations from amongst the most learned people of his day, including Antoine Arnauld, Peirre Gassendi, and Thomas Hobbes . The first edition of the Meditations was published in Latin in 1641 with six sets of objections and his replies. A second edition published in 1642 also included a seventh set of objections and replies as well as a letter to Father Dinet in which Descartes defended his system against charges of unorthodoxy. These charges were raised at the Universities of Utrecht and Leiden and stemmed from various misunderstandings about his method and the supposed opposition of his theses to Aristotle and the Christian faith.

This controversy led Descartes to post two open letters against his enemies. The first is entitled Notes on a Program posted in 1642 in which Descartes refutes the theses of his recently estranged disciple, Henricus Regius, a professor of medicine at Utrecht. These Notes were intended not only to refute what Descartes understood to be Regius’ false theses but also to distance himself from his former disciple, who had started a ruckus at Utrecht by making unorthodox claims about the nature of human beings. The second is a long attack directed at the rector of Utrecht, Gisbertus Voetius in the Open Letter to Voetius posted in 1643. This was in response to a pamphlet anonymously circulated by some of Voetius’ friends at the University of Leiden further attacking Descartes’ philosophy. Descartes’ Open Letter led Voetius to have him summoned before the council of Utrecht, who threatened him with expulsion and the public burning of his books. Descartes, however, was able to flee to the Hague and convince the Prince of Orange to intervene on his behalf.

In the following year (1643), Descartes began an affectionate and philosophically fruitful correspondence with Princess Elizabeth of Bohemia, who was known for her acute intellect and had read the Discourse on Method . Yet, as this correspondence with Elizabeth was beginning, Descartes was already in the midst of writing a textbook version of his philosophy entitled Principles of Philosophy , which he ultimately dedicated to her. Although it was originally supposed to have six parts, he published it in 1644 with only four completed: The Principles of Human Knowledge, The Principles of Material Things, The Visible Universe, and The Earth. The other two parts were to be on plant and animal life and on human beings, but he decided it would be impossible for him to conduct all the experiments necessary for writing them. Elizabeth probed Descartes about issues that he had not dealt with in much detail before, including free will, the passions and morals. This eventually inspired Descartes to write a treatise entitled The Passions of the Soul , which was published just before his departure to Sweden in 1649. Also, during these later years, the Meditations and Principles were translated from Latin into French for a wider, more popular audience and were published in 1647.

In late 1646, Queen Christina of Sweden initiated a correspondence with Descartes through a French diplomat and friend of Descartes’ named Chanut. Christina pressed Descartes on moral issues and a discussion of the absolute good. This correspondence eventually led to an invitation for Descartes to join the Queen’s court in Stockholm in February 1649. Although he had his reservations about going, Descartes finally accepted Christina’s invitation in July of that year. He arrived in Sweden in September 1649 where he was asked to rise at 5:00am to meet the Queen to discuss philosophy, contrary to his usual habit, developed at La Fleche, of sleeping in late,. His decision to go to Sweden, however, was ill-fated, for Descartes caught pneumonia and died on February 11, 1650.

2. The Modern Turn

A. against scholasticism.

Descartes is often called the “Father of Modern Philosophy,” implying that he provided the seed for a new philosophy that broke away from the old in important ways. This “old” philosophy is Aristotle’s as it was appropriated and interpreted throughout the later medieval period. In fact, Aristotelianism was so entrenched in the intellectual institutions of Descartes’ time that commentators argued that evidence for its the truth could be found in the Bible. Accordingly, if someone were to try to refute some main Aristotelian tenet, then he could be accused of holding a position contrary to the word of God and be punished. However, by Descartes’ time, many had come out in some way against one Scholastic-Aristotelian thesis or other. So, when Descartes argued for the implementation of his modern system of philosophy, breaks with the Scholastic tradition were not unprecedented.

Descartes broke with this tradition in at least two fundamental ways. The first was his rejection of substantial forms as explanatory principles in physics. A substantial form was thought to be an immaterial principle of material organization that resulted in a particular thing of a certain kind. The main principle of substantial forms was the final cause or purpose of being that kind of thing. For example, the bird called the swallow. The substantial form of “swallowness” unites with matter so as to organize it for the sake of being a swallow kind of thing. This also means that any dispositions or faculties the swallow has by virtue of being that kind of thing is ultimately explained by the goal or final cause of being a swallow. So, for instance, the goal of being a swallow is the cause of the swallow’s ability to fly. Hence, on this account, a swallow flies for the sake of being a swallow. Although this might be true, it does not say anything new or useful about swallows, and so it seemed to Descartes that Scholastic philosophy and science was incapable of discovering any new or useful knowledge.

Descartes rejected the use of substantial forms and their concomitant final causes in physics precisely for this reason. Indeed, his essay Meteorology , that appeared alongside the Discourse on Method , was intended to show that clearer and more fruitful explanations can be obtained without reference to substantial forms but only by way of deductions from the configuration and motion of parts. Hence, his point was to show that mechanistic principles are better suited for making progress in the physical sciences. Another reason Descartes rejected substantial forms and final causes in physics was his belief that these notions were the result of the confusion of the idea of the body with that of the mind. In the Sixth Replies , Descartes uses the Scholastic conception of gravity in a stone, to make his point. On this account, a characteristic goal of being a stone was a tendency to move toward the center of the earth. This explanation implies that the stone has knowledge of this goal, of the center of the earth and of how to get there. But how can a stone know anything, since it does not think? So, it is a mistake to ascribe mental properties like knowledge to entirely physical things. This mistake should be avoided by clearly distinguishing the idea of the mind from the idea of the body. Descartes considered himself to be the first to do this. His expulsion of the metaphysical principles of substantial forms and final causes helped clear the way for Descartes’ new metaphysical principles on which his modern, mechanistic physics was based.

The second fundamental point of difference Descartes had with the Scholastics was his denial of the thesis that all knowledge must come from sensation. The Scholastics were devoted to the Aristotelian tenet that everyone is born with a clean slate, and that all material for intellectual understanding must be provided through sensation. Descartes, however, argued that since the senses sometimes deceive, they cannot be a reliable source for knowledge. Furthermore, the truth of propositions based on sensation is naturally probabilistic and the propositions, therefore, are doubtful premises when used in arguments. Descartes was deeply dissatisfied with such uncertain knowledge. He then replaced the uncertain premises derived from sensation with the absolute certainty of the clear and distinct ideas perceived by the mind alone, as will be explained below.

b. Descartes’ Project

In the preface to the French edition of the Principles of Philosophy , Descartes uses a tree as a metaphor for his holistic view of philosophy. “The roots are metaphysics, the trunk is physics, and the branches emerging from the trunk are all the other sciences, which may be reduced to three principal ones, namely medicine, mechanics and morals” (AT IXB 14: CSM I 186). Although Descartes does not expand much more on this image, a few other insights into his overall project can be discerned. First, notice that metaphysics constitutes the roots securing the rest of the tree. For it is in Descartes’ metaphysics where an absolutely certain and secure epistemological foundation is discovered. This, in turn, grounds knowledge of the geometrical properties of bodies, which is the basis for his physics. Second, physics constitutes the trunk of the tree, which grows up directly from the roots and provides the basis for the rest of the sciences. Third, the sciences of medicine, mechanics and morals grow out of the trunk of physics, which implies that these other sciences are just applications of his mechanistic science to particular subject areas. Finally, the fruits of the philosophy tree are mainly found on these three branches, which are the sciences most useful and beneficial to humankind. However, an endeavor this grand cannot be conducted haphazardly but should be carried out in an orderly and systematic way. Hence, before even attempting to plant this tree, Descartes must first figure out a method for doing so.

Aristotle and subsequent medieval dialecticians set out a fairly large, though limited, set of acceptable argument forms known as “syllogisms” composed of a general or major premise, a particular or minor premise and a conclusion. Although Descartes recognized that these syllogistic forms preserve truth from premises to conclusion such that if the premises are true, then the conclusion must be true, he still found them faulty. First, these premises are supposed to be known when, in fact, they are merely believed, since they express only probabilities based on sensation. Accordingly, conclusions derived from merely probable premises can only be probable themselves, and, therefore, these probable syllogisms serve more to increase doubt rather than knowledge Moreover, the employment of this method by those steeped in the Scholastic tradition had led to such subtle conjectures and plausible arguments that counter-arguments were easily constructed, leading to profound confusion. As a result, the Scholastic tradition had become such a confusing web of arguments, counter-arguments and subtle distinctions that the truth often got lost in the cracks. ( Rules for the Direction of the Mind, AT X 364, 405-406 & 430: CSM I 11-12, 36 & 51-52).

Descartes sought to avoid these difficulties through the clarity and absolute certainty of geometrical-style demonstration. In geometry, theorems are deduced from a set of self-evident axioms and universally agreed upon definitions. Accordingly, direct apprehension of clear, simple and indubitable truths (or axioms) by intuition and deductions from those truths can lead to new and indubitable knowledge. Descartes found this promising for several reasons. First, the ideas of geometry are clear and distinct, and therefore they are easily understood unlike the confused and obscure ideas of sensation. Second, the propositions constituting geometrical demonstrations are not probabilistic conjectures but are absolutely certain so as to be immune from doubt. This has the additional advantage that any proposition derived from some one or combination of these absolutely certain truths will itself be absolutely certain. Hence, geometry’s rules of inference preserve absolutely certain truth from simple, indubitable and intuitively grasped axioms to their deductive consequences unlike the probable syllogisms of the Scholastics.

The choice of geometrical method was obvious for Descartes given his previous success in applying this method to other disciplines like optics. Yet his application of this method to philosophy was not unproblematic due to a revival of ancient arguments for global or radical skepticism based on the doubtfulness of human reasoning. But Descartes wanted to show that truths both intuitively grasped and deduced are beyond this possibility of doubt. His tactic was to show that, despite the best skeptical arguments, there is at least one intuitive truth that is beyond all doubt and from which the rest of human knowledge can be deduced. This is precisely the project of Descartes’ seminal work, Meditations on First Philosophy .

In the First Meditation , Descartes lays out several arguments for doubting all of his previously held beliefs. He first observes that the senses sometimes deceive, for example, objects at a distance appear to be quite small, and surely it is not prudent to trust someone (or something) that has deceived us even once. However, although this may apply to sensations derived under certain circumstances, doesn’t it seem certain that “I am here, sitting by the fire, wearing a winter dressing gown, holding this piece of paper in my hands, and so on”? (AT VII 18: CSM II 13). Descartes’ point is that even though the senses deceive us some of the time, what basis for doubt exists for the immediate belief that, for example, you are reading this article? But maybe the belief of reading this article or of sitting by the fireplace is not based on true sensations at all but on the false sensations found in dreams. If such sensations are just dreams, then it is not really the case that you are reading this article but in fact you are in bed asleep. Since there is no principled way of distinguishing waking life from dreams, any belief based on sensation has been shown to be doubtful. This includes not only the mundane beliefs about reading articles or sitting by the fire but even the beliefs of experimental science are doubtful, because the observations upon which they are based may not be true but mere dream images. Therefore, all beliefs based on sensation have been called into doubt, because it might all be a dream.

This, however, does not pertain to mathematical beliefs, since they are not based on sensation but on reason. For even though one is dreaming, for example, that, 2 + 3 = 5, the certainty of this proposition is not called into doubt, because 2 + 3 = 5 whether the one believing it is awake or dreaming. Descartes continues to wonder about whether or not God could make him believe there is an earth, sky and other extended things when, in fact, these things do not exist at all. In fact, people sometimes make mistakes about things they think are most certain such as mathematical calculations. But maybe people are not mistaken just some of the time but all of the time such that believing that 2 + 3 = 5 is some kind of persistent and collective mistake, and so the sum of 2 + 3 is really something other than 5. However, such universal deception seems inconsistent with God’s supreme goodness. Indeed, even the occasional deception of mathematical miscalculation also seems inconsistent with God’s goodness, yet people do sometimes make mistakes. Then, in line with the skeptics, Descartes supposes, for the sake of his method, that God does not exist, but instead there is an evil demon with supreme power and cunning that puts all his efforts into deceiving him so that he is always mistaken about everything, including mathematics.

In this way, Descartes called all of his previous beliefs into doubt through some of the best skeptical arguments of his day But he was still not satisfied and decided to go a step further by considering false any belief that falls prey to even the slightest doubt. So, by the end of the First Meditation , Descartes finds himself in a whirlpool of false beliefs. However, it is important to realize that these doubts and the supposed falsehood of all his beliefs are for the sake of his method: he does not really believe that he is dreaming or is being deceived by an evil demon; he recognizes that his doubt is merely hyperbolic. But the point of this “methodological” or ‘hyperbolic” doubt is to clear the mind of preconceived opinions that might obscure the truth. The goal then is to find something that cannot be doubted even though an evil demon is deceiving him and even though he is dreaming. This first indubitable truth will then serve as an intuitively grasped metaphysical “axiom” from which absolutely certain knowledge can be deduced. For more, see Cartesian skepticism .

4. The Mind

A. cogito, ergo sum.

In the Second Meditation , Descartes tries to establish absolute certainty in his famous reasoning: Cogito, ergo sum or “I think, therefore I am.” These Meditations are conducted from the first person perspective, from Descartes.’ However, he expects his reader to meditate along with him to see how his conclusions were reached. This is especially important in the Second Meditation where the intuitively grasped truth of “I exist” occurs. So the discussion here of this truth will take place from the first person or “I” perspective. All sensory beliefs had been found doubtful in the previous meditation, and therefore all such beliefs are now considered false. This includes the belief that I have a body endowed with sense organs. But does the supposed falsehood of this belief mean that I do not exist? No, for if I convinced myself that my beliefs are false, then surely there must be an “I” that was convinced. Moreover, even if I am being deceived by an evil demon, I must exist in order to be deceived at all. So “I must finally conclude that the proposition, ‘I am,’ ‘I exist,’ is necessarily true whenever it is put forward by me or conceived in my mind” (AT VII 25: CSM II 16-17). This just means that the mere fact that I am thinking, regardless of whether or not what I am thinking is true or false, implies that there must be something engaged in that activity, namely an “I.” Hence, “I exist” is an indubitable and, therefore, absolutely certain belief that serves as an axiom from which other, absolutely certain truths can be deduced.

b. The Nature of the Mind and its Ideas

The Second Meditation continues with Descartes asking, “What am I?” After discarding the traditional Scholastic-Aristotelian concept of a human being as a rational animal due to the inherent difficulties of defining “rational” and “animal,” he finally concludes that he is a thinking thing, a mind: “A thing that doubts, understands, affirms, denies, is willing, is unwilling, and also imagines and has sense perceptions” (AT VII 28: CSM II 19). In the Principles , part I, sections 32 and 48, Descartes distinguishes intellectual perception and volition as what properly belongs to the nature of the mind alone while imagination and sensation are, in some sense, faculties of the mind insofar as it is united with a body. So imagination and sensation are faculties of the mind in a weaker sense than intellect and will, since they require a body in order to perform their functions. Finally, in the Sixth Meditation , Descartes claims that the mind or “I” is a non-extended thing. Now, since extension is the nature of body, is a necessary feature of body, it follows that the mind is by its nature not a body but an immaterial thing. Therefore, what I am is an immaterial thinking thing with the faculties of intellect and will.

It is also important to notice that the mind is a substance and the modes of a thinking substance are its ideas. For Descartes a substance is a thing requiring nothing else in order to exist. Strictly speaking, this applies only to God whose existence is his essence, but the term “substance” can be applied to creatures in a qualified sense. Minds are substances in that they require nothing except God’s concurrence, in order to exist. But ideas are “modes” or “ways” of thinking, and, therefore, modes are not substances, since they must be the ideas of some mind or other. So, ideas require, in addition to God’s concurrence, some created thinking substance in order to exist (see Principles of Philosophy , part I, sections 51 & 52). Hence the mind is an immaterial thinking substance, while its ideas are its modes or ways of thinking.

Descartes continues on to distinguish three kinds of ideas at the beginning of the Third Meditation , namely those that are fabricated, adventitious, or innate. Fabricated ideas are mere inventions of the mind. Accordingly, the mind can control them so that they can be examined and set aside at will and their internal content can be changed. Adventitious ideas are sensations produced by some material thing existing externally to the mind. But, unlike fabrications, adventitious ideas cannot be examined and set aside at will nor can their internal content be manipulated by the mind. For example, no matter how hard one tries, if someone is standing next to a fire, she cannot help but feel the heat as heat. She cannot set aside the sensory idea of heat by merely willing it as we can do with our idea of Santa Claus, for example. She also cannot change its internal content so as to feel something other than heat–say, cold. Finally, innate ideas are placed in the mind by God at creation. These ideas can be examined and set aside at will but their internal content cannot be manipulated. Geometrical ideas are paradigm examples of innate ideas. For example, the idea of a triangle can be examined and set aside at will, but its internal content cannot be manipulated so as to cease being the idea of a three-sided figure. Other examples of innate ideas would be metaphysical principles like “what is done cannot be undone,” the idea of the mind, and the idea of God.

Descartes’ idea of God will be discussed momentarily, but let’s consider his claim that the mind is better known than the body. This is the main point of the wax example found in the Second Meditation . Here, Descartes pauses from his methodological doubt to examine a particular piece of wax fresh from the honeycomb:

It has not yet quite lost the taste of the honey; it retains some of the scent of flowers from which it was gathered; its color shape and size are plain to see; it is hard, cold and can be handled without difficulty; if you rap it with your knuckle it makes a sound. (AT VII 30: CSM II 20)

The point is that the senses perceive certain qualities of the wax like its hardness, smell, and so forth. But, as it is moved closer to the fire, all of these sensible qualities change. “Look: the residual taste is eliminated, the smell goes away, the color changes, the shape is lost, the size increases, it becomes liquid and hot” (AT VII 30: CSM II 20). However, despite these changes in what the senses perceive of the wax, it is still judged to be the same wax now as before. To warrant this judgment, something that does not change must have been perceived in the wax.

This reasoning establishes at least three important points. First, all sensation involves some sort of judgment, which is a mental mode. Accordingly, every sensation is, in some sense, a mental mode, and “the more attributes [that is, modes] we discover in the same thing or substance, the clearer is our knowledge of that substance” (AT VIIIA 8: CSM I 196). Based on this principle, the mind is better known than the body, because it has ideas about both extended and mental things and not just of extended things, and so it has discovered more modes in itself than in bodily substances. Second, this is also supposed to show that what is unchangeable in the wax is its extension in length, breadth and depth, which is not perceivable by the senses but by the mind alone. The shape and size of the wax are modes of this extension and can, therefore, change. But the extension constituting this wax remains the same and permits the judgment that the body with the modes existing in it after being moved by the fire is the same body as before even though all of its sensible qualities have changed. One final lesson is that Descartes is attempting to wean his reader from reliance on sense images as a source for, or an aid to, knowledge. Instead, people should become accustomed to thinking without images in order to clearly understand things not readily or accurately represented by them, for example, God and the mind. So, according to Descartes, immaterial, mental things are better known and, therefore, are better sources of knowledge than extended things.

a. The Causal Arguments

At the beginning of the Third Meditation only “I exist” and “I am a thinking thing” are beyond doubt and are, therefore, absolutely certain. From these intuitively grasped, absolutely certain truths, Descartes now goes on to deduce the existence of something other than himself, namely God. Descartes begins by considering what is necessary for something to be the adequate cause of its effect. This will be called the “Causal Adequacy Principle” and is expressed as follows: “there must be at least as much reality in the efficient and total cause as in the effect of that cause,” which in turn implies that something cannot come from nothing (AT VII 40: CSM II 28). Here Descartes is espousing a causal theory that implies whatever is possessed by an effect must have been given to it by its cause. For example, when a pot of water is heated to a boil, it must have received that heat from some cause that had at least that much heat. Moreover, something that is not hot enough cannot cause water to boil, because it does not have the requisite reality to bring about that effect. In other words, something cannot give what it does not have.

Descartes goes on to apply this principle to the cause of his ideas. This version of the Causal Adequacy Principle states that whatever is contained objectively in an idea must be contained either formally or eminently in the cause of that idea. Definitions of some key terms are now in order. First, the objective reality contained in an idea is just its representational content; in other words, it is the “object” of the idea or what that idea is about. The idea of the sun, for instance, contains the reality of the sun in it objectively. Second, the formal reality contained in something is a reality actually contained in that thing. For example, the sun itself has the formal reality of extension since it is actually an extended thing or body. Finally, a reality is contained in something eminently when that reality is contained in it in a higher form such that (1) the thing does not possess that reality formally, but (2) it has the ability to cause that reality formally in something else. For example, God is not formally an extended thing but solely a thinking thing; however, he is eminently the extended universe in that it exists in him in a higher form, and accordingly he has the ability to cause its existence. The main point is that the Causal Adequacy Principle also pertains to the causes of ideas so that, for instance, the idea of the sun must be caused by something that contains the reality of the sun either actually (formally) or in some higher form (eminently).

Once this principle is established, Descartes looks for an idea of which he could not be the cause. Based on this principle, he can be the cause of the objective reality of any idea that he has either formally or eminently. He is formally a finite substance, and so he can be the cause of any idea with the objective reality of a finite substance. Moreover, since finite substances require only God’s concurrence to exist and modes require a finite substance and God, finite substances are more real than modes. Accordingly, a finite substance is not formally but eminently a mode, and so he can be the cause of all his ideas of modes. But the idea of God is the idea of an infinite substance. Since a finite substance is less real than an infinite substance by virtue of the latter’s absolute independence, it follows that Descartes, a finite substance, cannot be the cause of his idea of an infinite substance. This is because a finite substance does not have enough reality to be the cause of this idea, for if a finite substance were the cause of this idea, then where would it have gotten the extra reality? But the idea must have come from something. So something that is actually an infinite substance, namely God, must be the cause of the idea of an infinite substance. Therefore, God exists as the only possible cause of this idea.

Notice that in this argument Descartes makes a direct inference from having the idea of an infinite substance to the actual existence of God. He provides another argument that is cosmological in nature in response to a possible objection to this first argument. This objection is that the cause of a finite substance with the idea of God could also be a finite substance with the idea of God. Yet what was the cause of that finite substance with the idea of God? Well, another finite substance with the idea of God. But what was the cause of that finite substance with the idea of God? Well, another finite substance . . . and so on to infinity. Eventually an ultimate cause of the idea of God must be reached in order to provide an adequate explanation of its existence in the first place and thereby stop the infinite regress. That ultimate cause must be God, because only he has enough reality to cause it. So, in the end, Descartes claims to have deduced God’s existence from the intuitions of his own existence as a finite substance with the idea of God and the Causal Adequacy Principle, which is “manifest by the natural light,” thereby indicating that it is supposed to be an absolutely certain intuition as well.

b. The Ontological Argument

The ontological argument is found in the Fifth Meditation and follows a more straightforwardly geometrical line of reasoning. Here Descartes argues that God’s existence is deducible from the idea of his nature just as the fact that the sum of the interior angles of a triangle are equal to two right angles is deducible from the idea of the nature of a triangle. The point is that this property is contained in the nature of a triangle, and so it is inseparable from that nature. Accordingly, the nature of a triangle without this property is unintelligible. Similarly, it is apparent that the idea of God is that of a supremely perfect being, that is, a being with all perfections to the highest degree. Moreover, actual existence is a perfection, at least insofar as most would agree that it is better to actually exist than not. Now, if the idea of God did not contain actual existence, then it would lack a perfection. Accordingly, it would no longer be the idea of a supremely perfect being but the idea of something with an imperfection, namely non-existence, and, therefore, it would no longer be the idea of God. Hence, the idea of a supremely perfect being or God without existence is unintelligible. This means that existence is contained in the essence of an infinite substance, and therefore God must exist by his very nature. Indeed, any attempt to conceive of God as not existing would be like trying to conceive of a mountain without a valley – it just cannot be done.

6. The Epistemological Foundation

A. absolute certainty and the cartesian circle.

Recall that in the First Meditation Descartes supposed that an evil demon was deceiving him. So as long as this supposition remains in place, there is no hope of gaining any absolutely certain knowledge. But he was able to demonstrate God’s existence from intuitively grasped premises, thereby providing, a glimmer of hope of extricating himself from the evil demon scenario. The next step is to demonstrate that God cannot be a deceiver. At the beginning of the Fourth Meditation, Descartes claims that the will to deceive is “undoubtedly evidence of malice or weakness” so as to be an imperfection. But, since God has all perfections and no imperfections, it follows that God cannot be a deceiver. For to conceive of God with the will to deceive would be to conceive him to be both having no imperfections and having one imperfection, which is impossible; it would be like trying to conceive of a mountain without a valley. This conclusion, in addition to God’s existence, provides the absolutely certain foundation Descartes was seeking from the outset of the Meditations . It is absolutely certain because both conclusions (namely that God exists and that God cannot be a deceiver) have themselves been demonstrated from immediately grasped and absolutely certain intuitive truths.

This means that God cannot be the cause of human error, since he did not create humans with a faculty for generating them, nor could God create some being, like an evil demon, who is bent on deception. Rather, humans are the cause of their own errors when they do not use their faculty of judgment correctly. Second, God’s non-deceiving nature also serves to guarantee the truth of all clear and distinct ideas. So God would be a deceiver, if there were a clear and distinct idea that was false, since the mind cannot help but believe them to be true. Hence, clear and distinct ideas must be true on pain of contradiction. This also implies that knowledge of God’s existence is required for having any absolutely certain knowledge. Accordingly, atheists, who are ignorant of God’s existence, cannot have absolutely certain knowledge of any kind, including scientific knowledge.

But this veridical guarantee gives rise to a serious problem within the Meditations , stemming from the claim that all clear and distinct ideas are ultimately guaranteed by God’s existence, which is not established until the Third Meditation . This means that those truths reached in the Second Meditation , such as “I exist” and “I am a thinking thing,” and those principles used in the Third Meditation to conclude that God exists, are not clearly and distinctly understood, and so they cannot be absolutely certain. Hence, since the premises of the argument for God’s existence are not absolutely certain, the conclusion that God exists cannot be certain either. This is what is known as the “Cartesian Circle,” because Descartes’ reasoning seems to go in a circle in that he needs God’s existence for the absolute certainty of the earlier truths and yet he needs the absolute certainty of these earlier truths to demonstrate God’s existence with absolute certainty.

Descartes’ response to this concern is found in the Second Replies . There he argues that God’s veridical guarantee only pertains to the recollection of arguments and not the immediate awaRenéss of an argument’s clarity and distinctness currently under consideration. Hence, those truths reached before the demonstration of God’s existence are clear and distinct when they are being attended to but cannot be relied upon as absolutely certain when those arguments are recalled later on. But once God’s existence has been demonstrated, the recollection of the clear and distinct perception of the premises is sufficient for absolutely certain and, therefore, perfect knowledge of its conclusion (see also the Fifth Meditation at AT VII 69-70: CSM II XXX).

b. How to Avoid Error

In the Third Meditation , Descartes argues that only those ideas called “judgments” can, strictly speaking, be true or false, because it is only in making a judgment that the resemblance, conformity or correspondence of the idea to things themselves is affirmed or denied. So if one affirms that an idea corresponds to a thing itself when it really does not, then an error has occurred. This faculty of judging is described in more detail in the Fourth Meditation . Here judgment is described as a faculty of the mind resulting from the interaction of the faculties of intellect and will. Here Descartes observes that the intellect is finite in that humans do not know everything, and so their understanding of things is limited. But the will or faculty of choice is seemingly infinite in that it can be applied to just about anything whatsoever. The finitude of the intellect along with this seeming infinitude of the will is the source of human error. For errors arise when the will exceeds the understanding such that something laying beyond the limits of the understanding is voluntarily affirmed or denied. To put it more simply: people make mistakes when they choose to pass judgment on things they do not fully understand. So the will should be restrained within the bounds of what the mind understands in order to avoid error. Indeed, Descartes maintains that judgments should only be made about things that are clearly and distinctly understood, since their truth is guaranteed by God’s non-deceiving nature. If one only makes judgments about what is clearly and distinctly understood and abstains from making judgments about things that are not, then error would be avoided altogether. In fact, it would be impossible to go wrong if this rule were unwaveringly followed.

7. Mind-Body Relation

A. the real distinction.

One of Descartes’ main conclusions is that the mind is really distinct from the body. But what is a “real distinction”? Descartes explains it best at Principles , part 1, section 60. Here he first states that it is a distinction between two or more substances. Second, a real distinction is perceived when one substance can be clearly and distinctly understood without the other and vice versa. Third, this clear and distinct understanding shows that God can bring about anything understood in this way. Hence, in arguing for the real distinction between mind and body, Descartes is arguing that 1) the mind is a substance, 2) it can be clearly and distinctly understood without any other substance, including bodies, and 3) that God could create a mental substance all by itself without any other created substance. So Descartes is ultimately arguing for the possibility of minds or souls existing without bodies.

Descartes argues that mind and body are really distinct in two places in the Sixth Meditation . The first argument is that he has a clear and distinct understanding of the mind as a thinking, non-extended thing and of the body as an extended, non-thinking thing. So these respective ideas are clearly and distinctly understood to be opposite from one another and, therefore, each can be understood all by itself without the other. Two points should be mentioned here. First, Descartes’ claim that these perceptions are clear and distinct indicates that the mind cannot help but believe them true, and so they must be true for otherwise God would be a deceiver, which is impossible. So the premises of this argument are firmly rooted in his foundation for absolutely certain knowledge. Second, this indicates further that he knows that God can create mind and body in the way that they are being clearly and distinctly understood. Therefore, the mind can exist without the body and vice versa.

The second version is found later in the Sixth Meditation where Descartes claims to understand the nature of body or extension to be divisible into parts, while the nature of the mind is understood to be “something quite simple and complete” so as not to be composed of parts and is, therefore, indivisible. From this it follows that mind and body cannot have the same nature, for if this were true, then the same thing would be both divisible and not divisible, which is impossible. Hence, mind and body must have two completely different natures in order for each to be able to be understood all by itself without the other. Although Descartes does not make the further inference here to the conclusion that mind and body are two really distinct substances, it nevertheless follows from their respective abilities to be clearly and distinctly understood without each other that God could create one without the other.

b. The Mind-Body Problem

The famous mind-body problem has its origins in Descartes’ conclusion that mind and body are really distinct. The crux of the difficulty lies in the claim that the respective natures of mind and body are completely different and, in some way, opposite from one another. On this account, the mind is an entirely immaterial thing without any extension in it whatsoever; and, conversely, the body is an entirely material thing without any thinking in it at all. This also means that each substance can have only its kind of modes. For instance, the mind can only have modes of understanding, will and, in some sense, sensation, while the body can only have modes of size, shape, motion, and quantity. But bodies cannot have modes of understanding or willing, since these are not ways of being extended; and minds cannot have modes of shape or motion, since these are not ways of thinking.

The difficulty arises when it is noticed that sometimes the will moves the body, for example, the intention to ask a question in class causes the raising of your arm, and certain motions in the body cause the mind to have sensations. But how can two substances with completely different natures causally interact? Pierre Gassendi in the Fifth Objections and Princess Elizabeth in her correspondence with Descartes both noted this problem and explained it in terms of contact and motion. The main thrust of their concern is that the mind must be able to come into contact with the body in order to cause it to move. Yet contact must occur between two or more surfaces, and, since having a surface is a mode of extension, minds cannot have surfaces. Therefore, minds cannot come into contact with bodies in order to cause some of their limbs to move. Furthermore, although Gassendi and Elizabeth were concerned with how a mental substance can cause motion in a bodily substance, a similar problem can be found going the other way: how can the motion of particles in the eye, for example, traveling through the optic nerve to the brain cause visual sensations in the mind, if no contact or transfer of motion is possible between the two?

This could be a serious problem for Descartes, because the actual existence of modes of sensation and voluntary bodily movement indicates that mind and body do causally interact. But the completely different natures of mind and body seem to preclude the possibility of this interaction. Hence, if this problem cannot be resolved, then it could be used to imply that mind and body are not completely different but they must have something in common in order to facilitate this interaction. Given Elizabeth’s and Gassendi’s concerns, it would suggest that the mind is an extended thing capable of having a surface and motion. Therefore, Descartes could not really come to a clear and distinct understanding of mind and body independently of one another, because the nature of the mind would have to include extension or body in it.

Descartes, however, never seemed very concerned about this problem. The reason for this lack of concern is his conviction expressed to both Gassendi and Elizabeth that the problem rests upon a misunderstanding about the union between mind and body. Though he does not elaborate to Gassendi, Descartes does provide some insight in a 21 May 1643 letter to Elizabeth. In that letter, Descartes distinguishes between various primitive notions. The first is the notion of the body, which entails the notions of shape and motion. The second is the notion of the mind or soul, which includes the perceptions of the intellect and the inclinations of the will. The third is the notion of the union of the soul with the body, on which depend the notion of the soul’s power to move the body and the body’s power to cause sensations and passions in the soul.

The notions entailed by or included in the primitive notions of body and soul just are the notions of their respective modes. This suggests that the notions depending on the primitive notion of the union of soul and body are the modes of the entity resulting from this union. This would also mean that a human being is one thing instead of two things that causally interact through contact and motion as Elizabeth and Gassendi supposed. Instead, a human being, that is, a soul united with a body, would be a whole that is more than the sum of its parts. Accordingly, the mind or soul is a part with its own capacity for modes of intellect and will; the body is a part with its own capacity for modes of size, shape, motion and quantity; and the union of mind and body or human being, has a capacity for its own set of modes over and above the capacities possessed by the parts alone. On this account, modes of voluntary bodily movement would not be modes of the body alone resulting from its mechanistic causal interaction with a mental substance, but rather they would be modes of the whole human being. The explanation of, for example, raising the arm would be found in a principle of choice internal to human nature and similarly sensations would be modes of the whole human being. Hence, the human being would be causing itself to move and would have sensations and, therefore, the problem of causal interaction between mind and body is avoided altogether. Finally, on the account sketched here, Descartes’ human being is actually one, whole thing, while mind and body are its parts that God could make exist independently of one another.

However, a final point should be made before closing this section. The position sketched in the previous couple of paragraphs is not the prevalent view among scholars and requires more justification than can be provided here. Most scholars understand Descartes’ doctrine of the real distinction between mind and body in much the same way as Elizabeth and Gassendi did such that Descartes’ human being is believed to be not one, whole thing but two substances that somehow mechanistically interact. This also means that they find the mind-body problem to be a serious, if not fatal, flaw of Descartes’ entire philosophy. But the benefit of the brief account provided here is that it helps explain Descartes’ lack of concern for this issue and his persistent claims that an understanding of the union of mind and body would put to rest people’s concerns about causal interaction via contact and motion.

8. Body and the Physical Sciences

A. existence of the external world.

In the Sixth Meditation , Descartes recognizes that sensation is a passive faculty that receives sensory ideas from something else. But what is this “something else”? According to the Causal Adequacy Principle of the Third Meditation , this cause must have at least as much reality either formally or eminently as is contained objectively in the produced sensory idea. It, therefore, must be either Descartes himself, a body or extended thing that actually has what is contained objectively in the sensory idea, or God or some creature more noble than a body, who would possess that reality eminently. It cannot be Descartes, since he has no control over these ideas. It cannot be God or some other creature more noble than a body, for if this were so, then God would be a deceiver, because the very strong inclination to believe that bodies are the cause of sensory ideas would then be wrong; and if it is wrong, there is no faculty that could discover the error. Accordingly, God would be the source of the mistake and not human beings, which means that he would be a deceiver. So bodies must be the cause of the ideas of them, and therefore bodies exist externally to the mind.

b. The Nature of Body

In part II of the Principles , Descartes argues that the entire physical universe is corporeal substance indefinitely extended in length, breadth, and depth. This means that the extension constituting bodies and the extension constituting the space in which those bodies are said to be located are the same. Here Descartes is rejecting the claim held by some that bodies have something over and above extension as part of their nature, namely impenetrability, while space is just penetrable extension in which impenetrable bodies are located. Therefore, body and space have the same extension in that body is not impenetrable extension and space penetrable extension, but rather there is only one kind of extension. Descartes maintains further that extension entails impenetrability, and hence there is only impenetrable extension. He goes on to state that: “The terms ‘place’ and ‘space,’ then, do not signify anything different from the body which is said to be in a place . . .” (AT VIIIA 47: CSM I 228). Hence, it is not that bodies are in space but that the extended universe is composed of a plurality or plenum of impenetrable bodies. On this account, there is no place in which a particular body is located, but rather what is called a “place” is just a particular body’s relation to other bodies. However, when a body is said to change its place, it merely has changed its relation to these other bodies, but it does not leave an “empty” space behind to be filled by another body. Rather, another body takes the place of the first such that a new part of extension now constitutes that place or space.

Here an example should prove helpful. Consider the example of a full wine bottle. The wine is said to occupy that place within the bottle. Once the wine is finished, this place is now constituted by the quantity of air now occupying it. Notice that the extension of the wine and that of the air are two different sets of bodies, and so the place inside the wine bottle was constituted by two different pieces of extension. But, since these two pieces of extension have the same size, shape and relation to the body surrounding it, that is, the bottle, it is called one and the same “place” even though, strictly speaking, it is made up of two different pieces of extension. Therefore, so long as bodies of the same shape, size and position continue to replace each other, it is considered one and the same place.

This assimilation of a place or space with the body constituting it gives rise to an interesting philosophical problem. Since a place is identical with the body constituting it, how does a place retain its identity and, therefore, remain the “same” place when it is replaced by another body that now constitutes it? A return to the wine bottle example will help to illustrate this point. Recall that first the extension of the wine constituted the place inside the bottle and then, after the wine was finished, that place inside the body was constituted by the extension of the air now occupying it. So, since the wine’s extension is different from the air’s extension, it seems to follow that the place inside the wine bottle is not the exactly same place but two different places at two different times. It is difficult to see how Descartes would address this issue.

Another important consequence of Descartes’ assimilation of bodies and space is that a vacuum or an empty space is unintelligible. This is because an empty space, according to Descartes, would just be a non-extended space, which is impossible. A return to the wine bottle will further illustrate this point. Notice that the place inside the wine bottle was first constituted by the wine and then by air. These are two different kinds of extended things, but they are extended things nonetheless. Accordingly, the place inside the bottle is constituted first by one body (the wine) and then by another (air). But suppose that all extension is removed from the bottle so that there is an “empty space.” Now, distance is a mode requiring extension to exist, for it makes no sense to speak of spatial distance without space or extension. So, under these circumstances, no mode of distance could exist inside the bottle. That is, no distance would exist between the bottle’s sides, and therefore the sides would touch. Therefore, an empty space cannot exist between two or more bodies.

Descartes’ close assimilation of body and space, his rejection of the vacuum, and some textual issues have lead many to infer an asymmetry in his metaphysics of thinking and extended things. This asymmetry is found in the claim that particular minds are substances for Descartes but not particular bodies. Rather, these considerations indicate to some that only the whole, physical universe is a substance, while particular bodies, for example, the wine bottle, are modes of that substance. Though the textual issues are many, the main philosophical problem stems from the rejection of the vacuum. The argument goes like this: particular bodies are not really distinct substances, because two or more particular bodies cannot be clearly and distinctly understood with an empty space between them; that is, they are not separable from each other, even by the power of God. Hence, particular bodies are not substances, and therefore they must be modes. However, this line of reasoning is a result of misunderstanding the criterion for a real distinction. Instead of trying to understand two bodies with an empty space between them, one body should be understood all by itself so that God could have created a world with that body, for example, the wine bottle, as its only existent. Hence, since it requires only God’s concurrence to exist, it is a substance that is really distinct from all other thinking and extended substances. Although difficulties also arise for this argument from Descartes’ account of bodily surfaces as a mode shared between bodies, these are too complex to address here. But, suffice it to say that the textual evidence is also in favor of the claim that Descartes, despite the unforeseen problem about surfaces, maintained that particular bodies are substances. The most telling piece of textual evidence is found in a 1642 letter to Gibeuf:

From the simple fact that I consider two halves of a part of matter, however small it may be, as two complete substances . . . I conclude with certainty that they are really divisible. (AT III 477: CSMK 202-203