A Closer Look at Child Labor in the Philippines

- June 8, 2021

In May 2021, the story of a 10-year-old farm boy from Sultan Kudarat went viral online. Reymark received praises from the viewers for working tirelessly so he could put food on the table for his family. With his parents abandoning him to his ailing grandparents, the young boy is thus forced to labor together with his horse on the mountain. Though donations and outside help for Reymark poured in shortly after, it only highlighted the hard and long battle against child labor in the Philippines.

Reymark’s story is only one of the many instances of this harsh reality in the country. If anything, his story vividly illustrated the factors why child labor continues to exist. Millions of children who are born into poverty, broken families, and ingrained traditions are the common victims. Familial obligations would bind generations into a never-ending chain of servitude. This global dilemma haunts us, as child labor practices remain unsolved.

What is Child Labor?

Child labor, as defined by the International Labour Organization (ILO) , is work taken on by children and adolescents that is harmful for their well-being. These include work that deprives children of their childhood, their potential, and their dignity. Not classified as child labor are activities that help with their growth and welfare. Child work to be classified child labor mainly varies upon the child’s age, type, hours, and condition under which the children performed the work.

What are the Causes of Child Labor?

Millions of children who become victims of forced labor were born into poor families. They are essential for the survival as they contribute to the hard-earned income of their family. Their tasks include farming, hunting, child rearing, and eventually apprenticeship. In these instances, parents and guardians give little to no importance to the children’s formal schooling. And as the industrial revolution progressed, conditions for these children only worsened.

Nevertheless, as we advance in technology and industry, calls have become louder for rights to be put in place to protect children from a life of hardship and—worse—from shortened life from toil and labor. These institutional rights protect children from the worst forms of child labor such as enslavement, trafficking, and separation from their parents. Unfortunately, today impoverished parents and regions still subject children to child labor practices, mostly in parts of the world with high levels of poverty.

Number of Children Forced to Work

In their 2016 report, ILO estimated that there are 152 million children who are victims of child labor globally , almost half of whom are in hazardous work. These are children aged 5 to 17, with 64 million girls and 88 million boys. As defined by ILO, the worst forms of child labor are children being enslaved, separated from their families, exposed to serious hazards and illnesses, and left to fend for themselves on the streets.

Countries with the highest numbers of child laborers are war-stricken and also the poorest regions. Nigeria, Pakistan, and Afghanistan have the most child laborers not in school. The eradication of child labor on the side of this world seemed to have slowed down. In fact, the condition of child exploitation has worsened. In a data gathered by ILO, sub-Saharan Africa has, by far, the largest share of child laborers worldwide. 72.1 million African children are in child labor and 31.5 million are in hazardous work.

Child Labor in the Philippines

Sadly, Filipinos are no strangers to this. Poverty and culture are the biggest hindrances in the fight against child labor in our country. Children are being robbed off a period in their lives where they should experience education and prepare for adult life while under the protection and care of their parents. Many Filipino parents still rely on their children to work and bring them out of hardships. Like Reymark, some being forced to work at an early age, in essence stripping them of their formative stages for growth and education.

Another factor to consider is the parents’ knowledge of family planning. Parents with less education and knowledge of birth control and family planning would have an average of four or more children. While considered blessings, these children would eventually be a financial burden to the parents. These families do not make plans and are ignorant about the true cost of child rearing, from childhood to ideally graduating from college where one could get a minimum wage job.

Finally, tradition gets in the way. Children, even after graduating and moving out of their parents’ home, continue to provide financial help to their parents. This practice only foments the antiquated mindset that children are indebted to their parents, and that providing for them continuously is a sign of honoring and respecting them.

Key Statistics and How Child Labor Factors In

In a country whose minimum wage is PHP 7,385 per month, the cost of living for a family of four is PHP 80,000. Only college graduates could hope to pierce the minimum wage barrier. Other factors that hinder a family’s financial growth include the country’s high rate of teenage pregnancy and more than half of children being born out of wedlock. With the increase in the rate of poverty, there is a necessary need for families to put all their hands on deck in helping put food on their tables. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated this problem, with a recent ILO and UNICEF study revealing child labor on the rise for the country.

Many parents still strive to bring their children their much-needed time to study and grow in a formal learning environment. Nonetheless, for the poorest in the country, those living below the poverty line cannot afford to do so.

The country’s poorest families would have their children help in their parents’ small businesses. These include weaving and selling homemade cleaning products, flowers, or street food. Even worse, these children end up begging on the streets. Those living in rural communities work in their family’s fields to produce and sell crops or help their parents in the mines.

Meanwhile, in the country’s underbelly’s child labor problem, sexual predators and human traffickers hound Filipino children where modern-day slavery still lives on throughout the black markets of Asia. Legal framework protecting children from the most hazardous works is continually being established in the country. But there are still loopholes for predators to exploit Philippine laws and regulations.

Childhope Philippines and Our Crusade Against Child Labor

Childhope Philippines fights an uphill battle in promoting and protecting children’s rights on the city streets. The urban poor children who work on the streets of Metro Manila alone number between 50,000 to 70,000, while 50,000 is also the number of known Filipino domestic workers as per the country’s Labor and Employment department. With help from kindhearted donors these children do not have to fear for their daily bread.

Childhope provides accredited educational and child protection modules through its various programs and made up of volunteers specializing in their respective areas. The KalyEskwela program provides alternative learning to street children and vocational skills to older out-of-school youth.

In addition, health missions through KliniKalye provide ease of access to medicine and health consultations through its mobile clinics. Other programs include life skill training in computer literacy and sports, and social evaluation and rehabilitation for those who need it. It is the hope that the NGO provides social protection to the little ones as we brace for the true impact of a post-pandemic world.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to rage on, children’s welfare has never been more front and center. With our Street Education and Protection (STEP) Program , we at Childhope Philippines commit to helping children claim their rights to a better quality of life free from child labor and lack of education.

If you’d like to help them realize a brighter future, you may donate for our causes , which will be directly used toward programs that give these children a chance at a better life. But if you wish to be more hands-on about helping, contact us and be a volunteer today.

Subscribe to our Mailing List

©1989-2024 All Rights Reserved.

By providing an email address. I agree to the Terms of Use and acknowledge that I have read the Privacy Policy .

Child labor: The monster remains a threat in PH, worldwide

IMAGE BASED ON AFP PHOTOS

MANILA, Philippines—The fight against child labor has seen global progress in the past years. However, it remains to be a major challenge in many parts of the world as new data showed a rising number of children being forced into mostly hazardous work.

Child labor, as defined by the International Labour Organization (ILO), is “work that deprives children of their childhood, their potential, and their dignity, and that is harmful to physical and mental development.“

These include work that is:

- mentally, physically, socially, or morally dangerous and harmful to children

- interferes with their schooling by depriving them of the opportunity to attend school

- obliges them to leave school prematurely

- requires them to attempt to combine school attendance with excessively long and heavy work.

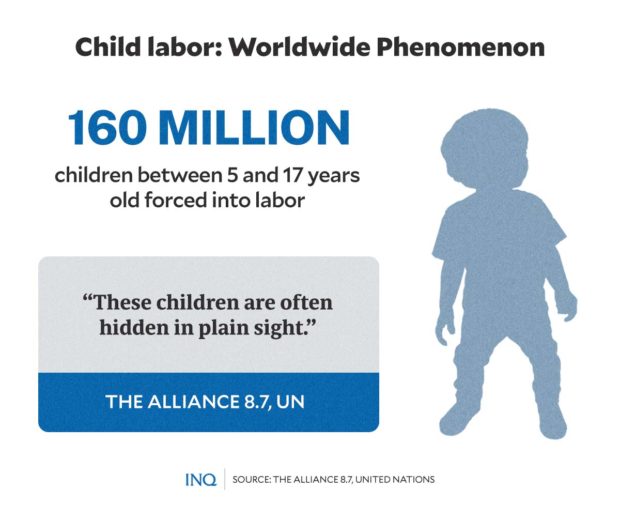

Data by Alliance 8.7—a global partnership for eradicating forced labor, modern slavery, human trafficking and child labor around the world—showed that across the globe, there are 160 million—or 1 in 10—children aged 5 to 17 engaged in child labor in 2020.

The good news, according to Alliance 8.7, is that between 2016 and 2020, there has been significant progress in addressing and reducing the number of children entering the workforce at a very early age.

Progress so far

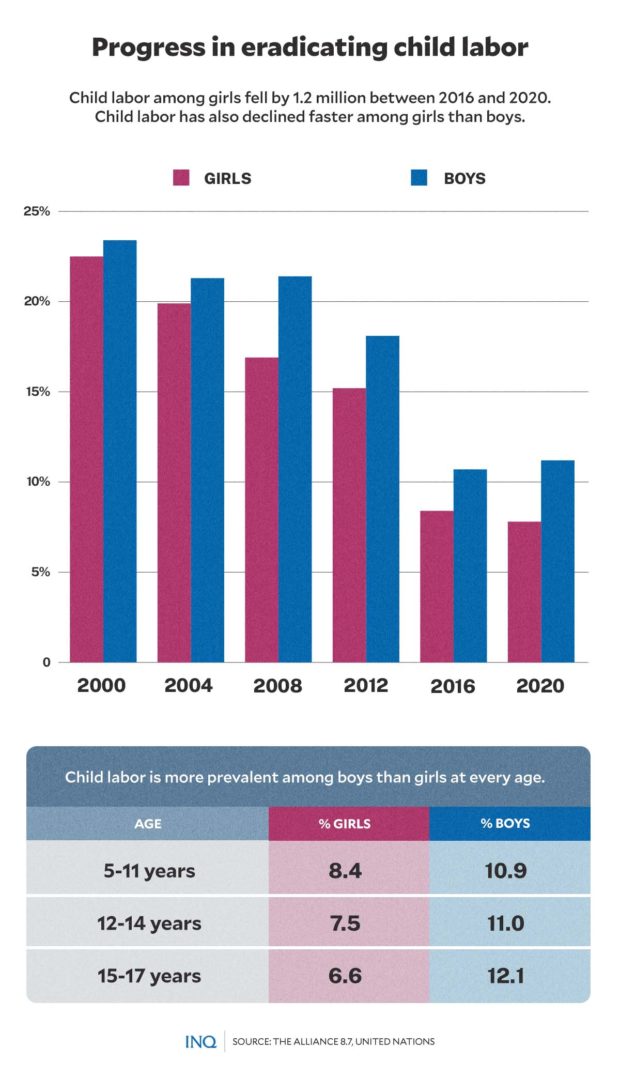

Alliance 8.7 noted that between 2016 and 2020, child labor among girls went down to 1.2 million cases. From 8.4 percent recorded in 2016, the share of young girls in child labor slipped to 7.8 percent in 2020.

Child labor among boys slightly rose from 10.7 percent in 2016 to 11.2 percent in 2020. The data likewise showed that child labor has been more prevalent among boys than girls at every age.

Figures also showed that since 2000, cases of child labor had declined faster among girls than boys.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

However, while Alliance 8.7 acknowledged that the numbers represent a “success story,” it explained that it does not present the full picture.

“Many girls engage in caregiving, cooking, and other domestic chores for long hours that interfere with their schooling. But the definition of child labour does not include such work–if it did, many more girls would be classified as child labourers,” it added.

Alliance 8.7 said child labor among those aged 12 to 14 years olds fell from 49.1 million cases in 2016 to 35.6 million in 2020.

However, the organization also saw “a worrying rise in child labor among very young children” or those who are just 5 to 11 years old. From 8.3 percent in 2016, the share of 5 to 11 year-old children forced to work rose to 9.7 percent in 2020.

Global progress stagnated

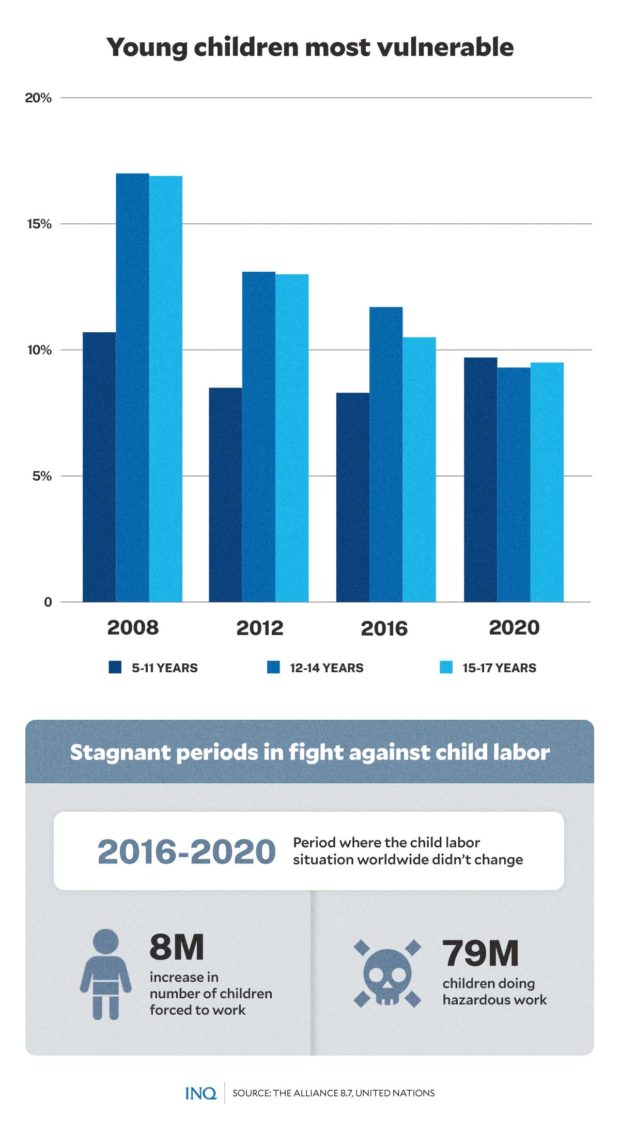

Global progress in the fight against child labor, however, stagnated from 2016 to 2020.

According to Alliance 8.7, over the four year period, the percentage of children in child labor around the globe remained unchanged while the absolute number of children forced to work went up by over 8 million.

From 151.6 million in 2016, the number of children in child labor rose to 160 million.

“This result is alarming. Global progress against child labour has stalled for the first time since the ILO began tracking it, two decades ago. Without urgent measures, the COVID-19 crisis is likely to push millions more children into child labour,” Alliance 8.7 said.

“This is our reality check. We have a global commitment to end child labour by 2025. If we do not act now on an unprecedented scale, the timeline for ending child labour will stretch years further into the future,” it added.

Nearly half of children forced to work in 2020—around 79 million—are doing so in hazardous conditions which directly endanger their health, safety, or moral development. The figure increased from 72.5 million in 2016.

“Hazardous work has persisted and expanded among younger children. This is particularly concerning, considering the common hazards that children are exposed to include harmful agrochemicals, physically strenuous tasks such as carrying heavy loads, exposure to extreme temperatures, use of dangerous tools, and worse,” said Alliance 8.7.

Child labor in PH

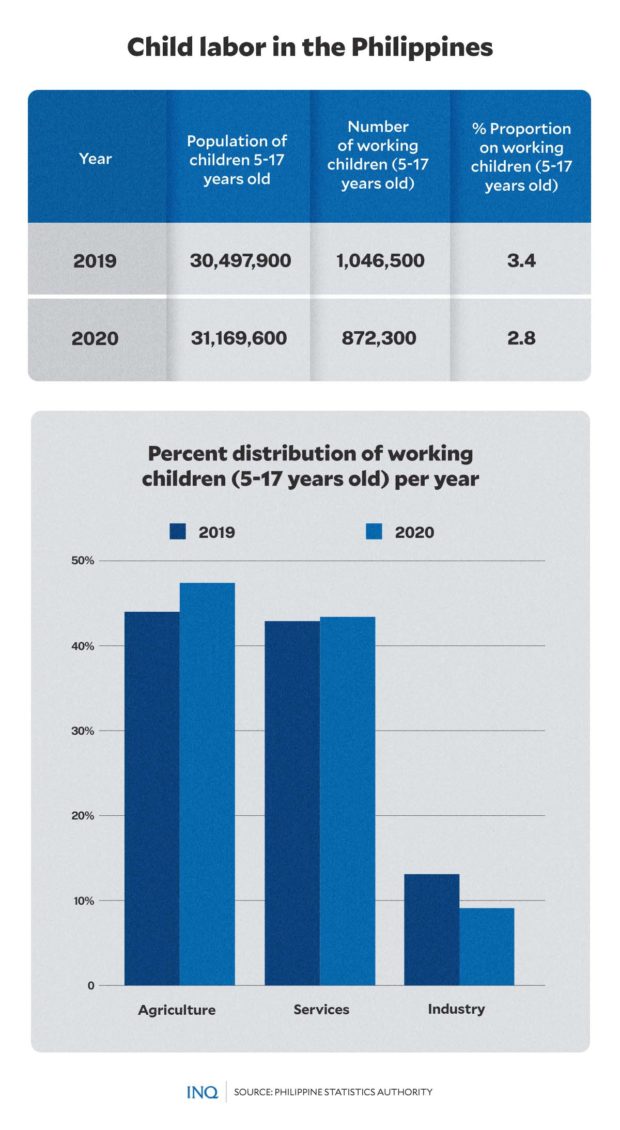

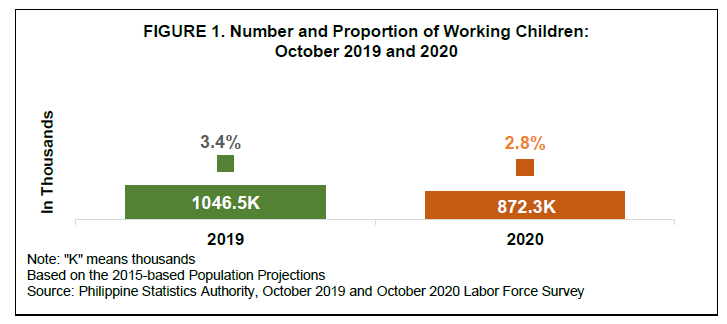

In the Philippines, as of 2020, there were 872,300 children aged 5 to 17 years old in child labor—or 2.8 percent of the age group’s total population, pegged at around 31,169,600, according to data released by the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA).

The figures slid from 1,046,500 children aged 5 to 17 in child labor recorded in 2019—or 3.4 percent of the total 30,497,900 children in the same age group that same year.

The PSA also noted that children belonging to the older age groups (5 to 17 years) were more likely to work than the younger ones. Majority of working children belonged to the age group 15 to 17 years of age, accounting for 68.9 percent of the total working children in 2020 and 67.4 percent in 2019.

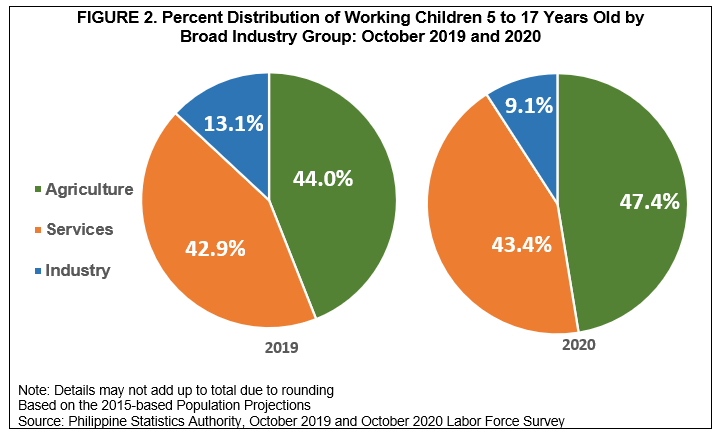

In 2020, the sector with the highest number of working children was agriculture—accounting for 43.4 percent of the total number of working children that year. It was followed by the services sector with 43.4 percent, and industry sector with 9.1 percent.

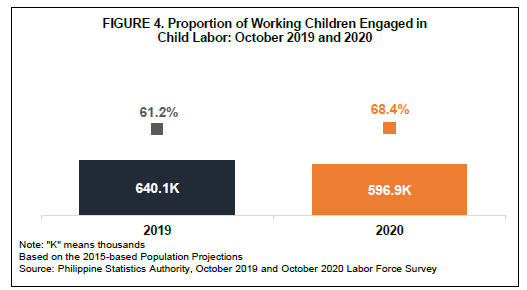

The proportion of children (5 to 17 years of age) engaged in hazardous work and long working hours, according to the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) administrative order, shot up from 61.2 percent in 2019 to 68.4 percent in 2020.

Unicef had expressed concern about the child labor situation in the Philippines, noting that millions of Filipino children might be pushed to work as a result of the COVID-19 crisis.

“As the pandemic wreaks havoc on family incomes, without support, many could resort to child labour,” ILO Director-General Guy Ryder previously said.

“Social protection is vital in times of crisis, as it provides assistance to those who are most vulnerable. Integrating child labour concerns across broader policies for education, social protection, justice, labour markets, and international human and labour rights makes a critical difference,” he added.

COVID-19, Unicef noted, could result in a rise in poverty and, therefore, an increase in child labor as households use every available means to survive.

“In times of crisis, child labour becomes a coping mechanism for many families,” said former Unicef Executive Director Henrietta Fore.

“As poverty rises, schools close and the availability of social services decreases, more children are pushed into the workforce. As we reimagine the world post-COVID, we need to make sure that children and their families have the tools they need to weather similar storms in the future. Quality education, social protection services and better economic opportunities can be game changers.”

Strengthening fight against child labor

Alliance 8.7 believes that without proper mitigation measures, an estimated 8.9 million more children will “likely be engaged in child labour by the end of 2022 due to the poverty impacts of the COVID-19 crisis.”

“Without accelerated action, we will not come close to our goal of eliminating child labour by 2030. Projections based on trends predict a mere 22% reduction in child labour over the next eight years,” it added.

To help reduce child labor worldwide and prevent the projected increase in the number of children engaged in hazardous work, Alliance 8.7 said policies that promote social protection programs would be crucial.

These include policies on improving access to health care and income security, as well as policies that promote decent work and gender equality.

In the Philippines, several laws are in place to protect the safety and welfare of children, including:

- Presidential Decree (P.D.) 442 Labor Code of the Philippines

- P.D. 603, The Child and Youth Welfare Code

- Republic Act (RA) 9231 or an Act Providing for the Elimination of the

- Worst Forms of Child Labor and Affording Stronger Protection for the

- Working Child, which amended RA No. 7610

- R.A. 9775, or Anti-Child Pornography Act

- R.A. 10361, or Domestic Workers Act

- R.A. 10364, or the Expanded Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act of 2012 that included as acts of trafficking the worst forms of child labor defined in

- Republic Act No. 9231

- R.A. 10821, or the Children’s Emergency Relief and Protection Act.

Last October, the Quezon City government also formed “Task Force Sapaguita” to protect children in the city from forced labor and abuse, following the increase in the number of minors selling sampaguita garlands in the city.

Subscribe to our daily newsletter

Task Force Sampaguita is currently helping profiled families by way of livelihood assistance, educational assistance, and more.

READ: QC gov’t forms task force against child labor, abuse

Last June, DOLE reported that over 90,000 children have already been removed from doing harmful work since the department started profiling child laborers—as part of the Philippine Development Plan 2017–2022 goal of reducing child labor cases by 30 percent.

READ: 90,000 child laborers nasagip ng DOLE

Related stories: ph slips in inclusion index, putting women, children at risk when 10-year-olds can’t read: the dulling of ph education, disclaimer: comments do not represent the views of inquirer.net. we reserve the right to exclude comments which are inconsistent with our editorial standards. full disclaimer, © copyright 1997-2024 inquirer.net | all rights reserved.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. By continuing, you are agreeing to our use of cookies. To find out more, please click this link.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Child Labour in the Philippines: Determinants and Effects

2000, Asian Economic Journal

Related Papers

Fernando Aldaba , Leonardo Lanzona

Aniceto Orbeta

Philippine Journal of …

Leonardo Lanzona

Cesar C Rufino

This study utilized the recently available public use raw data file of the 2011 round of the Annual Poverty Indicator Survey (APIS) to establish the latest stylized facts on the Philippine child labor situation. Public use file of the 2008 APIS was also used to generate comparative descriptives. It is also an attempt to jointly estimate the schooling and employment choices of Filipino children via the multinomial logistic model that used the four different permutations of schooling and employment as the mutually exclusive and exhaustive categories of choice. A value added feature of the study is the use of survey design consistent procedures in establishing the descriptives as well as the estimates of the main empirical model. Tabulated summaries of the results reveal some alarming developments in the child labor situation of the country. The outcome of the econometric modeling confirms the empirical relevance of certain covariates discussed in the literature concerning schooling/wo...

Ivory Myka Galang

The measured impact on child labor varies among the conditional cash transfer (CCT) programs with observed significant impact on children’s schooling. In the Philippines, the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps) was regarded by World Bank as one of the best targeted social protection programs in the world. This research investigated whether or not 4Ps has reduced the incidence of child laborers, particularly those aged 12 to 14 years. Using the Annual Poverty Indicator Surveys of 2011, propensity score matching method was implemented to estimate the treatment effects on the treated (ATT). The results indicated positive and significant impact on schooling outcomes, which ranged from 5.7 to 7.5 percentage points. The 4Ps helped in narrowing the gap between male and female in terms of school attendance. Moreover, greater impact was observed among older children. However, despite the significant school attendance increase caused by the program, the results showed no significant imp...

Dlsu Business & Economics Review

This study utilized the recently available public use raw data file of the 2011 round of the Annual Poverty Indicator Survey (APIS) to establish the latest stylized facts on the Philippine child labor situation. Public use file of the 2008 APIS was also used to generate comparative descriptives. It is also an attempt to jointly estimate the schooling and employment choices of Filipino children via the multinomial logit model that used the four different permutations of schooling and employment as the mutually exclusive and exhaustive categories of choice. A value added feature of the study is the use of survey design consistent procedures in establishing the descriptives as well as the estimates of the main empirical model. Tabulated summaries of the results reveal some alarming developments in the child labor situation of the country. The outcome of the econometric modeling confirms the empirical relevance of certain covariates discussed in the literature concerning schooling/work ...

This study uses the recently available public use raw data file of the 2011 round of the Annual Poverty Indicator Survey (APIS) to establish the latest stylized facts on the Philippine child labor situation. It is also an attempt to jointly estimate the schooling and employment choices of the Filipino child via the multinomial logistic model that used the four different permutations of schooling and employment as the mutually exclusive and exhaustive categories of choice. A value added feature of the study is the use of survey design consistent procedures in establishing the descriptives as well as the estimates of the main empirical model. Tabulated summaries of the results reveal some alarming developments in the child labor situation of the country. The outcome of the econometric modeling confirms the empirical relevance certain covariates discussed in the literature concerning schooling/work choice formation of children.

BULLETIN OF GEOGRAPHY. SOCIO–ECONOMIC SERIES

BAYU KHARISMA

The existence of child labor is a complex phenomenon and is often considered a logical consequence, in a household, of the economic needs of poverty-stricken families. This is due to several factors such as the condition of the child himself, the family background, and the influences of parents, culture and environment. This paper aims to determine the effect of household structure on child labor by comparing households headed by divorced single mothers and nuclear households that include a mother and father in Indonesia. This study uses cross-sectional data from the 2014 Indonesia Family Life Survey (IFLS) with the instrumental variable (IV) method. The results showed that, for the nuclear households that include a mother and father, the probability of child labor decreased, or that when a divorced single mother heads the household, the likelihood of child labor increases, including in rural areas. The same thing happens when households headed by divorced single mothers tend to increase the likelihood of sons being sent into the labor market. Thus, household structure has a vital role in determining the decisions of parents to engage their children in paid employment.

World Bank Discussion Papers

Abdul Latif

RELATED PAPERS

Joop van de Merwe

Annales Henri Poincaré

Herbert Spohn

Catherine Milne

pablo campos

Malaysian Journal of Analytical Science

Hannis Fadzillah Mohsin

Jennifer Blue

Raúl Delgado

Macalester International

Andrei Codrescu

3D thermal and rheological models of the southern Río de la Plata Craton (Argentina): implications for the initial stage of the Colorado rifting and the evolution of Sierras Australes

Sebastián E Vazquez Lucero

Elena Alonso Lebrero

wempi eka rusmana

Journal of Medical Virology

Demet Ulusoy Binan

Cornell University - arXiv

Chaitanya Avinash Gadre

lasallista.edu.co

Natalia garzón grajales

International Journal of Thermofluids

mohammad Abdelkareem

Gümüşhane Üniversitesi Sağlık Bilimleri Dergisi

ŞEHRİNAZ POLAT

Publication Division, Aligarh Muslim University Aligarh

Zafar Minhaj

Portuguese Journal of Nephrology & Hypertension

Joana Margarida Eugénio Santos

Adibah Hani Haron

Gaceta Judicial

Unidad Académica de Investigaciones Jurídicas del Poder Judicial del Estado de Guanajuato

Academic Pathology

Alan Ducatman

See More Documents Like This

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Essay on Child Labor In The Philippines

Students are often asked to write an essay on Child Labor In The Philippines in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Child Labor In The Philippines

What is child labor.

Child labor is when kids under the age of 18 work. It is a big problem in the Philippines. Many children have to work to help their families earn money. This stops them from going to school and playing like other kids.

Why Children Work

Children in the Philippines work for many reasons. Some families are very poor and need extra money. Other times, disasters or debts force kids to work. They might sell things, help on farms, or even work in dangerous places.

Effects on Children

Working can harm children’s health and stop them from learning in school. It can also make them feel sad or tired. Children should be able to learn and grow without having to work.

Fighting Child Labor

People in the Philippines are trying to stop child labor. The government makes laws to protect children and groups help by giving families money or food so kids don’t have to work. Everyone can help by caring about this issue.

250 Words Essay on Child Labor In The Philippines

Child labor is when kids under the age of 18 work. It is a big problem in many countries, including the Philippines. These children often do hard jobs instead of going to school. This can harm their health and stop them from learning properly.

Why Child Labor Happens in the Philippines

In the Philippines, many families are very poor. They need money to live, so they send their children to work. Sometimes, there are not enough schools, or they are too far away. This makes it hard for kids to study, so they start working at a young age.

Types of Work Children Do

Children in the Philippines do many kinds of jobs. Some work on farms, while others sell things on the streets. There are kids who work in factories or even inside mines. These jobs can be dangerous and very tiring.

The Effects on Children

When children work, they can get hurt or sick. They also miss out on learning and playing. This can make it hard for them to have a better future. They might not get good jobs when they grow up because they did not go to school when they were young.

Ending Child Labor

To stop child labor, the government and other groups are trying to help. They give money to poor families and make sure there are schools for children to attend. They also teach families why education is important for their kids. Stopping child labor can help children have a happier and healthier life.

500 Words Essay on Child Labor In The Philippines

Child labor is when kids under the age of 18 work. This work is often bad for their health and stops them from going to school. Many countries, including the Philippines, face this problem. In the Philippines, many children have to work to help their families earn money.

Why Do Children Work in the Philippines?

There are many reasons why children in the Philippines end up working. One big reason is poverty. When families do not have enough money, they may feel like they have no choice but to make their children work. Sometimes, there are not enough jobs for adults, so children work to bring in extra money. Also, some families live in places where it is normal for children to work, so they do not see it as a bad thing.

In the Philippines, children work in different kinds of jobs. Some work on farms, picking fruits and vegetables or helping with the animals. Others work in cities, selling things on the streets, cleaning cars, or working in small shops. There are also children who work in dangerous places like mines or factories, which can be very harmful to their health.

The Effects of Child Labor

Child labor can hurt children in many ways. It can make them sick or injured, especially if they work in unsafe conditions. It also keeps them from going to school and learning. Without education, it is hard for them to get good jobs when they grow up. This can mean they stay poor, and their own children might also have to work.

What Is Being Done?

The government of the Philippines knows that child labor is a problem and is trying to stop it. They have made rules that say children under a certain age should not work, and they should go to school instead. There are also groups that help children who are working by giving them a chance to go to school and learn skills for better jobs.

How Can We Help?

Everyone can help fight child labor. People can support organizations that work to stop child labor. They can also buy things that are not made by children. It is important to tell others about why child labor is bad, so more people can help make a change.

Child labor in the Philippines is a big problem that hurts children and keeps them from having a good future. By understanding why it happens and how it affects kids, people can work together to stop it. Children should be allowed to play, learn, and grow up healthy, not work in jobs meant for adults. It is up to everyone to make sure that children are protected and given the chance to have a better life.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Learning From Obstacles

- Essay on Learning Disabilities

- Essay on Learning Assessment

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Working Children and Child Labor Situation

Proportion of working children 5 to 17 years old was estimated at 2.8 percent.

The total population of children 5 to 17 years old was estimated at 31.17 million in 2020. This was higher than the total number of Filipino children 5 to 17 years of age registered in 2019 at 30.50 million.

Of the estimated 31.17 million children 5 to 17 years old in 2020, 872 thousand or 2.8 percent were working. This was lower than the proportion of working children 5 to 17 years old in 2019 estimated at 3.4 percent. (Figure 1 and Table A)

Working children was higher among boys compared to the girls. Of the 872 thousand working children in 2020, 582 thousand or 66.7 percent were boys while 291 thousand or 33.3 percent were girls. In 2019, 65.6 percent of the working children were boys while 34.4 percent were girls.

Children belonging to the older age groups (15 to 17 years) were more likely to work than the younger ones. Majority of the working children belonged to age group 15 to 17 years of age accounting for 68.9 percent of the total working children in 2020 and 67.4 percent in 2019. (Table B)

Majority of working children were in agriculture sector

By broad industry group, agriculture sector registered the highest proportion of working children in 2020 at 47.4 percent. The same sector had working children accounted for 44.0 percent of the total working children in 2019. In addition, working children in the services sector was the second largest group accounted for 43.4 percent of the total working children in 2020. Working children in the industry sector consistently accounted for the smallest contributing sector at 9.1 percent. (Figure 2 and Table B)

Majority of the working children worked 20 hours or less per week

Working children were asked on the actual number of hours worked during the reference week. Of the total working children, majority (53.0%) reported to have worked 20 hours or less per week in 2020. This was lower than the proportion of children who worked 20 hours or less per week in 2019 at 69.6 percent. Meanwhile, children who worked for 21 to 40 hours increased to 26.7 percent in 2020 from the 14.8 percent in 2019. (Table B)

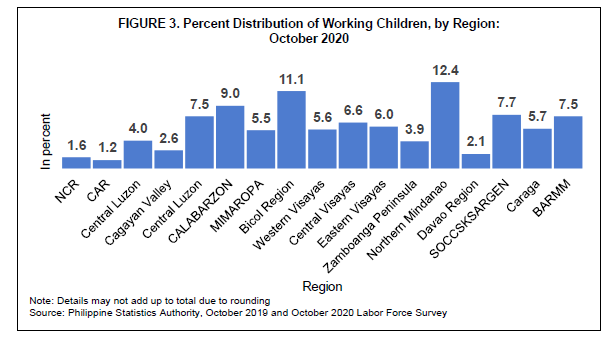

Working Children was highest in the Northern Mindanao

Across the regions, CALABARZON with about 4.22 million, National Capital Region (NCR) with nearly 3.35 million, and Central Luzon with around 3.26 million had the largest population of children 5 to 17 years old in 2020. In terms of proportion of working children, Northern Mindanao posted the highest at 7.2 percent in 2020 and 10.0 percent in 2019. (Table A)

In terms of the share of the working children, for every 100 working children in the country in 2020, around 12 (12.4%) resided in Northern Mindanao, 11 (11.1%) resided in Bicol Region, and 9 resided in CALABARZON. On the other hand, Cordillera Autonomous Region (1.2%), NCR (1.6%), Davao Region (2.1%), and Cagayan Valley (2.6%) each had less than 3 working children for every 100 working children in the country. (Figure 3 and Table B)

Child laborers in the country continued to drop in 2020

Child labor referred to in this report were those children 5 to 17 years of age engaged in hazardous work identified in the DOLE Administrative Order No. 149 or long working hours only.

The total number of working children considered engaged in child labor was estimated at 597 thousand in 2020. This magnitude of working children considered engaged in child labor was lower than the 640 thousand child laborers in 2019. (Table C)

In terms of proportion, 68.4 percent of the working children were engaged in child labor in 2020. This was higher than the estimate of 61.2 percent in 2019. (Figure 4 and Table C)

Of the estimated 597 thousand working children engaged in child labor in 2020, 435 thousand or 72.8 percent of them were boys while 162 thousand or 27.2 percent were girls. (Figure 5 and Table D)

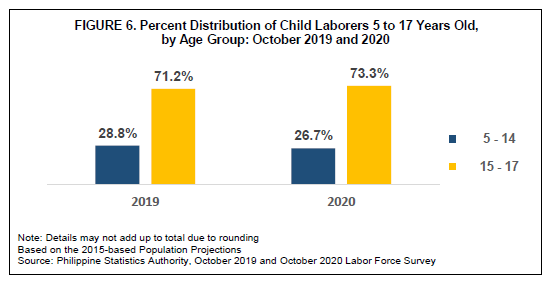

Across age groups, the largest proportion of working children considered engaged in child labor were in the ages 15 to 17 years at 73.3 percent in 2020. In the same manner, child laborers aged 15 to 17 years old comprised the largest share in 2019 at 71.2 percent. (Figure 6 and Table D)

Classified by broad industry group in 2020, about 63.6 percent of child laborers were in the agriculture sector, 28.6 percent were in the services sector, and 7.9 percent were in the industry sector. (Figure 7 and Table D)

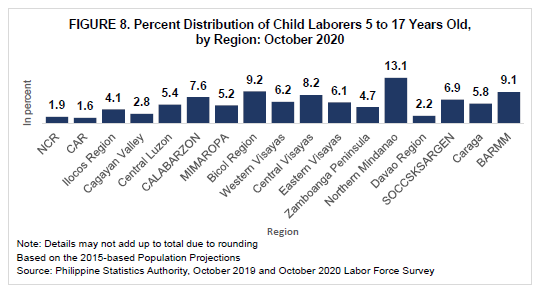

Thirteen in every 100 child laborers were in Northern Mindanao

Among the 17 regions, Northern Mindanao had the largest share of the country’s child laborers. For every 100 child laborers in the country in 2020, 13 (13.1%) were from Northern Mindanao, followed by Bicol Region with around 9 (9.2%) child laborers. Cordillera Administrative Region had the lowest share of child laborers at 1.6 percent followed by NCR at 1.9 percent and Davao Region at 2.2 percent in 2020. (Figure 8 and Table D)

The population of children aged 5 to 17 years old in 2020 was estimated at 31.17 million. This was higher than the total number of Filipino children 5 to 17 years of age in 2019 at 30.50 million.

Working children in 2020 were estimated at 2.8 percent of the 31.17 million children 5 to 17 years old. This was lower than the registered working children in 2019 at 3.4 percent.

In terms of the distribution of working children by broad industry group, agriculture sector remained dominant in 2020, followed by services sector, while industry sector remained the lowest contributor to the total working children.

Of the 872 thousand working children in 2020, 597 thousand or 68.4 percent were child laborers. Of these estimated child laborers, 73.3 percent were in age group 15 to 17 years. Moreover, 63.6 percent of the 597 thousand child laborers were found in the agriculture sector.

DENNIS S. MAPA, Ph.D. Undersecretary National Statistician and Civil Registrar General

Related Contents

Press conference on the january 2024 labor force survey (preliminary) results, unemployment rate in december 2023 was estimated at 3.1 percent, press conference on the december 2023 labor force survey (preliminary) results.

An official website of the United States government.

Here’s how you know

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Enforcing Trade Commitments

- Strengthening Labor Standards

- Combating Child Labor, Forced Labor, and Human Trafficking

- Cross-Cutting Issues

- Technical Assistance

- Monitoring, Evaluation, Research and Learning

- East Asia and Pacific

- Europe and Eurasia

- Middle East and Northern Africa

- South and Central Asia

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor

- List of Goods Produced By Child Labor or Forced Labor

- List of Products Produced by Forced or Indentured Child Labor

- Supply Chains Research

- Reports and Publications

- Grants and Contracts

- Sweat & Toil app

- Comply Chain

- Better Trade Tool

- ILAB Knowledge Portal

- Responsible Business Conduct and Labor Rights Info Hub

- Organizational Chart

- Laws and Regulations

- News Releases

- Success Stories

- Data and Statistics

- What Are Workers' Rights?

- Mission & Offices

- Careers at ILAB

- ILAB Diversity and Inclusion Statement

Child Labor and Forced Labor Reports

Philippines.

The Brutality of Sugar: Debt, Child Marriage and Hysterectomies

By Megha Rajagopalan and Qadri Inzamam. Photographs and video by Saumya Khandelwal.

This story was produced in collaboration with The Fuller Project. March 24, 2024

Archana Ashok Chaure has given her life to sugar.

She was married off to a sugar cane laborer in western India at about 14 — “too young,” she says, “to have any idea what marriage was.” Debt to her employer keeps her in the fields.

Last winter, she did what thousands of women here are pressured to do when faced with painful periods or routine ailments: She got a hysterectomy, and got back to work.

This keeps sugar flowing to companies like Coke and Pepsi.

Supported by

By Megha Rajagopalan and Qadri Inzamam

Photographs and Video by Saumya Khandelwal

This story was produced in collaboration with The Fuller Project.

The two soft-drink makers have helped turn the state of Maharashtra into a sugar-producing powerhouse. But a New York Times and Fuller Project investigation has found that these brands have also profited from a brutal system of labor that exploits children and leads to the unnecessary sterilization of working-age women.

Young girls are pushed into illegal child marriages so they can work alongside their husbands cutting and gathering sugar cane. Instead of receiving wages, they work to pay off advances from their employers — an arrangement that requires them to pay a fee for the privilege of missing work, even to see a doctor.

An extreme yet common consequence of this financial entrapment is hysterectomies. Labor brokers lend money for the surgeries, even to resolve ailments as routine as heavy, painful periods. And the women — most of them uneducated — say they have little choice.

Hysterectomies keep them working, undistracted by doctor visits or the hardship of menstruating in a field with no access to running water, toilets or shelter.

Removing a woman’s uterus has lasting consequences, particularly if she is under 40. In addition to the short-term risks of abdominal pain and blood clots, a hysterectomy is often accompanied by the removal of the ovaries, which brings about early menopause, raising the chance of heart disease, osteoporosis and other ailments.

But for many sugar laborers, the operation has a particularly grim outcome: Borrowing against future wages plunges them further into debt, ensuring that they return to the fields next season and beyond. Workers’ rights groups and the United Nations labor agency have defined such arrangements as forced labor.

“I had to rush to work immediately after the operation, as we had taken an advance,” Ms. Chaure said. “We neglect our health in front of money.”

Sugar producers and buyers have known about this abusive system for years. Coca-Cola’s consultants, for example, visited the fields and sugar mills of western India and, in 2019, reported that children were cutting sugar cane and laborers were working to repay their employers. They documented this in a report for the company, complete with an interview with a 10-year-old girl.

In an unrelated corporate report that year, the company said that it was supporting a program to “gradually reduce child labor” in India.

Labor abuse is endemic in Maharashtra, not limited to any particular mill or farm, according to a local government report and interviews with dozens of workers. Maharashtra sugar has been sweetening cans of Coke and Pepsi for more than a decade, according to an executive at NSL Sugars, which operates mills in the state.

PepsiCo, in response to a list of findings from The Times, confirmed that one of its largest international franchisees buys sugar from Maharashtra. The franchisee just opened its third manufacturing and bottling plant there. A new Coke factory is under construction in Maharashtra, and Coca-Cola confirmed that it, too, buys sugar in the state.

These companies use the sugar primarily for products sold in India, industry officials say. PepsiCo said the company and its partners purchase a small amount of sugar from Maharashtra, relative to total production in the state.

Both companies have published codes of conduct prohibiting suppliers and business partners from using child and forced labor.

“The description of the working conditions of sugar-cane cutters in Maharashtra is deeply concerning,” PepsiCo said in a statement. “We will engage with our franchisee partners to conduct an assessment to understand the sugar-cane cutter working conditions and any actions that may need to be taken.”

Coca-Cola declined to comment on a detailed list of questions.

The heartland of this exploitation is the district of Beed, an impoverished, rural region of Maharashtra that is home to much of the migrant sugar-cutting population. One local government report surveyed approximately 82,000 female sugar-cane workers from Beed, and found that about one in five had had hysterectomies. A separate, smaller government survey estimated the figure at one in three.

“The thinking of women is, if we get the surgery, then we’ll be able to work more,” said Deepa Mudhol-Munde, the district’s magistrate, or top civil servant.

The abuses continue — despite local government investigations, news reports and warnings from company consultants — because everyone says somebody else is responsible.

Big Western companies have policies pledging to root out human rights abuses in their supply chains. In practice, they seldom if ever visit the fields and largely rely on their suppliers, the sugar-mill owners, to oversee labor issues.

The mill owners, though, say that they do not actually employ the workers. They hire contractors to recruit migrants from far-off villages, transport them to the fields and pay their wages. How those workers are treated, the owners say, is between them and the contractors.

Those contractors are often young men whose only qualification is that they own a vehicle. They are merely doling out the mill owners’ money, they say. They could not possibly dictate working conditions or terms of employment.

Nobody pushes women to get hysterectomies as a form of population control. In fact, having children is commonplace. Because girls typically marry young, many have children in their teens.

Instead, they seek hysterectomies in hopes of stopping their periods, as a drastic form of uterine cancer prevention or to end the need for routine gynecological care.

“I couldn’t afford to miss work to see the doctor,” said Savita Dayanand Landge, a sugar-cane worker in her 30s who got a hysterectomy last year because she hoped it would end her need to visit doctors.

India is the world’s second largest sugar producer, and Maharashtra accounts for about a third of that production. In addition to supplying Indian and Western companies, the state has exported sugar to more than a dozen countries, where it disappeared into the global supply chain.

The abuses are born from the Maharashtra sugar industry’s peculiar setup. In other sugar regions, farm owners recruit local workers and pay them wages.

Maharashtra operates differently. About a million workers, typically from Beed, migrate for days to fields in the south and west. Throughout the harvest, from about October to March, they move from field to field, carting their belongings with them.

Instead of wages from farm owners, they receive an advance — often around $1,800 per couple, or roughly $5 a day per person for a six-month season — from a mill contractor. This century-old system reduces labor costs for sugar mills.

Our reporters interviewed people at every stage of the supply chain, including dozens of laborers, contractors, mill owners and former executives at multinational companies. The Times also examined medical records and interviewed doctors, lawmakers, government officials, researchers and aid workers who have spent careers examining the livelihoods of Maharashtra’s sugar workers.

Ms. Chaure is petite, barely five feet tall, with a tiny gold nose-ring in the shape of a flower and a grin that takes over her whole face. She speaks a million miles an hour and, when she feels particularly passionate, she grabs your wrist to make sure you are listening.

“It’s easy for people to take advantage of us,” she said, “because we have no education.” She has spent her life cutting sugar for a mill owned by NSL Sugars.

She began working in the sugar fields as a preteen and, now in her early 30s, she expects to continue for the rest of her life. The work has kept her family in the most grueling poverty, the kind that makes her skip meals so her three children have enough to eat.

Ms. Chaure knows there is nothing for her beyond sugar. But she hopes things will be different for her children.

‘There Wasn’t Any Option Left’

Ms. Chaure lay back on an operating-room cot last winter preparing for her hysterectomy. The hospital was bigger than any near her village, with clean floors and a busy, professional-looking staff.

As she looked at the white ceiling, the thought crossed her mind that, once she slipped out of consciousness, she might not come back.

Her hands trembled.

Who, she wondered, would look after her children?

“But since there wasn’t any option left for me,” she said, “I did it.”

Ms. Chaure had traveled to a city hospital hours from her village.

On a given day, the waiting room is crowded with patients from the countryside sitting nervously on metal chairs or cross-legged on the floor as a loudspeaker blares out names.

The women often have familiar ailments: pain that radiates down from their lower backs and prolonged or irregular periods that make work more difficult.

For Ms. Chaure, it was a heavy kind of ache, like a pull. She had pain in her hip, too. It pulsed down her leg and never seemed to go away. Her periods were irregular, which she suspected was from working all through her pregnancies, often forgoing food.

In the fields, Ms. Chaure, like the others, sleeps on the ground, spends hours a day hunched over and carries heavy loads on her head.

Tampons and pads are expensive and hard to find, and there is nowhere to dispose of them. Without access to running water, women address their periods in the fields, with reused cloth that they try to wash discreetly by hand.

“All the problems are intermingled with their personal hygiene and their economic condition. They have to work so hard,” said Dr. Ashok Belkhode, whose Maharashtra practice includes gynecology.

Hysterectomy is a routine surgery performed around the world, though infrequently for women in their 20s and 30s. In India, it is more common, including as a form of birth control, and other parts of the country also have high hysterectomy rates. But in Maharashtra’s sugar industry, everyone — contractors, other workers, even doctors — pushes women toward the surgery.

That is what happened to Ms. Landge, a mother of four with a red bindi and arms full of green bangles. She lives in a tiny concrete home atop a hill, overlooking her village and acres of farmland that turns the color of mustard seeds during the dry months.

Doctors prescribed painkillers and vitamins for her back and abdominal pain, but every appointment cost her a day’s wages and a fee for missing work.

“Everywhere I went,” Ms. Landge said, “hysterectomy was suggested.”

Ms. Chaure ended up on the operating table because a sonogram showed that she had ovarian cysts, her medical records show.

Instead of simply removing the cysts, her surgeon told her she should have a hysterectomy. She did not question the advice. She knew so many women who had done the same. She was terrified of getting cancer. And maybe this would end her pain, and the doctor visits.

“I might not be able to work well if the problems persist,” she said.

Years earlier, to pay one of her children’s medical bills, Ms. Chaure had sold a pair of gold earrings, a gift from her father worth about $30. Now there was nothing left to sell.

So she and her husband borrowed more money from their sugar contractor, promising to return next season to repay it. They already owed so much, Ms. Chaure figured, that they would have to go anyway.

The surgeon removed Ms. Chaure’s uterus, a cyst, an ovary and a fallopian tube. In an interview, her surgeon said it was necessary because the cyst was unusually large.

The Times shared details from Ms. Chaure’s file with Dr. Farinaz Seifi, the director of gynecology at Bridgeport Hospital and a professor at the Yale School of Medicine. “There was absolutely no indication for hysterectomy,” she said.

‘I Was Very Young’

In her wedding photographs, Ms. Chaure stares straight-faced into the camera. She had never met the groom. But that was normal. The same had happened to many of her friends.

Like many rural women in Maharashtra, Ms. Chaure does not know her exact age. She figures she was about 14 on her wedding day. It was two years after she dropped out of her village school so her parents could take her to the sugar fields.

“I was scared to get married,” she recalled, “really scared.”

She knew that marriage meant the end of something. She had dreamed of becoming a nurse. She could picture it — she would wear a crisp, clean uniform and work beneath a whirring ceiling fan, protected from the sun.

But marriage is the moment when many girls give up their futures, and their bodies, to sugar.

Every fall before the harvest, usually in October, the mill owners dispatch contractors to villages in Beed like Ms. Chaure’s to recruit laborers.

Child marriage is illegal in India and is regarded internationally as a human rights violation. Its roots in India run deep, and it has complex cultural and economic causes.

But in this part of Maharashtra, two economic incentives push girls into marriage.

First, sugar cutting is a two-person job. Husband-and-wife teams make twice as much as a man working alone. The two-person system is known as koyta, after the sickle that cuts the sugar cane.

Second, the longer that children accompany their parents in the field, the longer parents must support them. So families often seek to marry off daughters young, even in early adolescence.

“If we are married, their stress reduces and the responsibility is shifted to our husband’s shoulders,” Ms. Chaure said. “So they marry us off.”

Several women recalled being married only months after their first periods.

The links between marriage and sugar go so deep that girls were once married at the mill gates. Even now, weddings are often held before the harvest and the term “gate cane wedding” still comes up.

“Without koyta, there would be no reason to get married,” said Zhamabai Subhashratod, a 30-something sugar laborer who was married in her early teens and later had a hysterectomy.

Contractors, too, have an incentive to find brides, even if it means pressuring parents to marry off young daughters, said Tatwashil Baburao Kamble, the former head of Beed’s child-welfare committee.

“I’ve seen cases where the contractors tried to get it done before taking laborers to the farm — all their belongings were packed,” Mr. Kamble said. “All that was left was to get married.”

Some contractors even lend money for weddings.

“I’ve paid for weddings, for hospital bills,” said Bapurao Balbhim Shelke, a contractor who formerly worked for Dalmia Bharat Sugar.

“I just add the amount to the next year’s bill, and they can work it off,” said Dattu Ashruba Yadav, a contractor who lives in Beed. He said he had lent one couple 50,000 rupees, or about $600, for their wedding. That represents several months of a typical couple’s earnings.

Mira Govardhan Bhole has been working in the sugar fields since her marriage, about a year after her first period. Ms. Bhole is in her 30s but has a round baby face that always looks cheerful.

As a newlywed, she would disappear into cooking to avoid her husband.

When he told her she would have to cut sugar, she sobbed uncontrollably. “They brought me by throwing me in the vehicle,” she said. “I hadn’t even taken a bath or anything.”

In the field, she felt overwhelmed. There, sugar cane surrounds you, the stalks growing so high and close together that you can make out the sky only in patches.

The men bend forward, whipping machetes. The women usually do the rest.

First, they tear the sharp leaves off the cane. It takes practice. Pull downward and you will be fine, but stroke upward, even by accident, and the leaves make gashes as thin as paper cuts.

What Ms. Bhole remembers most about her first weeks is that her palms hurt so badly that she cried and cried.

After stripping the leaves, the women stack the cane in bundles.

They carry the bundles on their heads, then load them onto trucks.

Season after season, the weight can break down the disks in your neck, leaving a constant stiffness. If you ask doctors in the region what happens to the bodies of women in the sugar fields, this is the first injury they mention. Ms. Chaure has this problem, too, and she winces when she thinks about it.

More relentless, though, is the punishment of field life. The workday often ends after midnight, when trucks have hauled away the last of the day’s crop. Women sleep under tarpaulin tents with their families on thin mats cast onto the ground.

They wake as early as 4 a.m. to fetch water, build a fire, boil tea and cook lentils and vegetables. They wash clothes in a basin and then it is back to work, stripping and hauling sugar cane.

Workers said there were almost never official contracts or records tallying how much they cut. At the end of the season, contractors almost always declare that a balance remains.

“There is no possible way they could pay it back within one season,” said Ranjit Bhausaheb Waghmare, a contractor for Dalmia Bharat Sugar.

Dalmia supplies Coca-Cola in Maharashtra, according to S. Rangaprasad, who runs one of the mills there. Dalmia records also list Mondelez, the owner of Cadbury, as a customer. The company said it was “deeply concerned to hear allegations of labor issues at one of our suppliers. We will investigate.”

Pepsi’s franchisee also buys from Dalmia, but from mills outside the state, PepsiCo said.

Ms. Bhole sometimes fantasizes about a different life. A relative in a city a few hours away works as a housekeeper. The idea of getting paid to do chores sounds incredible.

But she says that no matter how hard she and her husband work, at the end of each season, her contractor says they still owe money. They have to return.

Worker-rights advocates say this is tantamount to bonded labor, a practice banned by law.

When Ms. Chaure’s husband took her to the fields after their wedding, she hoped they would be done in a season. That was more than 15 years ago. They are still in debt.

“We take an advance, repay some, and again take another advance,” she said.

The sugar mills keep all of this — child marriage, underage labor, wage debt and working conditions — at an arm’s length. Child marriage, they say, is a social problem that has nothing to do with the industry.

They say the contractors are responsible for the workers.

“The mill does not take on the burden of employing them,” said Mr. Rangaprasad, the head of a Dalmia mill.

Things Could Have Changed

Shubha Sekhar, a Coca-Cola executive who has focused on human rights in India, talked during the Covid pandemic to a group of university students. Speaking by videoconference, she described the challenges of operating in a country that Coke’s own documents identify as risky because of child and forced labor.

Typically, corporations buy from suppliers, she explained. With sugar, she said, at times “one doesn’t have visibility of what is happening beyond, in deep agriculture.”

But those deep fields are typically just outside the doors of Coke’s own suppliers. Sugar cane loses weight — and value — each minute after it is cut, so mills are usually built close to the farms.

All of the problems, including child marriage and hysterectomies, have been known in the region for years.

There was even a moment, not too long ago, when things might have changed.

In 2019, the newspaper The Hindu BusinessLine reported on an unusually high number of hysterectomies among female sugar-cane cutters in Maharashtra. In response, a state lawmaker, along with a team of researchers, launched an investigation. They surveyed thousands of women.

Their report that year described horrible working conditions and directly linked the high hysterectomy rate to the sugar industry. Unable to take time off during pregnancy or for doctor visits, women have no choice but to seek the surgery, the report concluded.

By happenstance, Coca-Cola issued its own report that year. After unrelated accusations out of Brazil and Cambodia about land-grabbing, Coca-Cola had hired a firm to audit its supply chain in several countries.

The auditors, from a group called Arche Advisors, visited 123 farms in Maharashtra and a neighboring state with a small sugar industry.

They found children at about half of them. Many had simply migrated with their families, but Arche’s report found children cutting, carrying and bundling sugar cane at 12 farms.

Nearly every laborer interviewed by reporters said children commonly worked in the sugar fields. The youngest ones do chores. Older ones perform all the work of cane cutters. A Times photographer saw children working in the fields.

The 2019 report includes an interview with a 10-year-old girl who “loves to go to school,” but instead works alongside her parents.

“She picks the cut cane and stacks it into a bundle, which her parents then load onto the truck,” the report says.

Arche noted that Coca-Cola suppliers did not provide toilets or shelter. And it cited “flags in the area of forced labor.” Only a few of the mills it surveyed had policies on bonded or child labor, and those applied only to the mills, not the farms.

The government report called on factories to provide water, toilets, basic sanitation and the minimum wage.

Few if any changes have been carried out.

Major buyers like PepsiCo and Coca-Cola say they hold their suppliers to exacting standards for labor rights. But that promise is only as good as their willingness to monitor thousands of farms at the base of their supply chains.

That rarely happens. An executive at NSL Sugars, a Coca-Cola and PepsiCo franchisee supplier that has mills around the country, said that soda-company representatives could be scrupulous in asking about sugar quality, production efficiency and environmental issues. Labor issues in the fields, he said, would almost never come up.

Soda-company inspectors seldom if ever visit the farms from which NSL sources its sugar cane, the executive said. The PepsiCo franchisee, Varun Beverages, did not respond to calls for comment.

Mill owners, too, rarely visit the fields. Executives at Dalmia and NSL Sugars say they keep virtually no records on their laborers.

“No one from the Dalmia factory has ever visited us in the tents or the fields,” said Anita Bhaisahab Waghmare, a laborer in her 40s who has worked at farms supplying Dalmia all her life and said she had a hysterectomy that she now regretted.

Ed Potter, the former head of global workplace rights at Coca-Cola, said the company had conducted many human rights audits during his tenure. But with so many suppliers, oversight can seem random.

“Imagine your hands going through some sand,” he said. “What you deal with is what sticks to your fingers. Most sand doesn’t stick to your fingers. But sometimes you get lucky.”

Sanjay Khatal, the managing director of a major lobbying group for sugar mills, said that mill owners could not provide any worker benefits without being seen as direct employers. That would raise costs and jeopardize the whole system.

“It is the very existence of the industry which can come into question,” he said.

One thing that changed after the government report was a rule intended to prevent unscrupulous doctors from profiting off unneeded surgeries.

“Some doctors have made it a way to earn more money,” said Dr. Chaitanya Kagde, a gynecologist at a government-run facility in Beed. (Though public hospitals offer hysterectomies free or at reduced cost, they are often far from rural women.)

The new rule required the civil surgeon, the district’s top health official, to approve hysterectomies.

But hysterectomies on younger women continue. Though many doctors agree that some surgeons perform them too often, they also note that patients request the surgery.

In an interview last May, Beed’s civil surgeon at the time, Suresh Sable, said the government should not second-guess doctors. “It’s not necessary to question their authority,” he said.

He said his office still approved 90 percent of hysterectomy requests.

One day last May, a few months after the harvest, Ms. Chaure and her husband made their way to the plot of land they farm near their home. It was 104 degrees. There was almost no shade or breeze and the air was so hot it took the shape of waves in the distance.

Her son, Aditya, was at the age where he was putting everything in his mouth — the back of a sticker, a Good Day biscuit, a pink toy watch. He was so preoccupied that he seemed to have forgotten to fuss.

Ms. Chaure, wearing a light floral sari, scooped him in one arm and hiked down the field.

It had been about six months since her hysterectomy and Ms. Chaure’s body hurt worse than usual.

Everything ached, especially her midsection. She was fed up with doctors and the work that had done this to her.

For the first time since being a teenager, she did not know whether she could migrate to cut sugar cane that season.

But the idea of borrowing more money without working to repay it terrified her.

She already stretched the family budget paper thin — growing tomatoes and peppers in a patch behind their home of concrete and corrugated metal.

“We have wasted our whole lives in this work,” she said.

By September, with the harvest looming, she still did not know if she could work. The contractor, she said, had been hassling her and her husband to take a bigger advance.

“It makes me so mad when those people say, ‘Nobody forced you to be a laborer,’” she said. She was washing her family’s clothes in a plastic bowl, slapping each garment against a rock. “Nobody chooses this life.”

It had been an exhausting few days. All three of her children had been coughing. The day before, she and her husband had fought, and he had hurled a basket of fresh cotton that she had just picked to the ground, covering it with mud. It could not be sold.

Finally, her husband left for the fields, to work alone. She stayed behind, resigned to the fact that it would push her family even deeper into poverty.

She worries about her children. She still harbors hopes for Aditya and his two big sisters, who are about 8 and 5 years old.

But Priyanka, the oldest, drove her crazy, skipping school to horse around with her younger siblings. Ms. Chaure remembers missing school herself, then dropping out. She remembers her dreams of being a nurse.

She wants things to be different for her daughter.

“I want her to be someone,” she said. “Do something in life.”

But for all her optimism, Ms. Chaure knows how tough it will be for her children, and how things are likely to go.

“They don’t like it,” she said. “But they need to get used to this life.”

This article was reported in collaboration with The Fuller Project, a journalism nonprofit that reports on global issues affecting women. Ankur Tangade contributed reporting. Produced by Nico Chilla .

Megha Rajagopalan is an international investigative reporter based in London. More about Megha Rajagopalan

Advertisement

- Skip to main content

Advancing social justice, promoting decent work

Ilo is a specialized agency of the united nations.

Gabay sa pagpapaunlad ng pamilyang Pilipino ukol sa child labour

Gabay sa pagpapaunlad ng pamilyang Pilipino: Modyul ukol sa child labour

Ang malawakang kahirapan, limitadong pagkamit ng edukasyon, at kakulangan sa pagpapatupad ng batas ay ilan sa mga dahilan ng pananatili ng problema ng pagkakaroon ng batang manggagawa sa mga rural na lugar. Ang pangmatagalang pagtanggal ng mga batang mangagagawa sa mga ito ay nangangailangan ng solusyon sa mismong ugat na pinanggagalingan ng problema at pagpapalaganap ng disenteng trabaho para sa mga may hustong gulang. Ang pagtutulungan ng mga institusyon at taong direktang nakikipag-ugnayan sa mga lugar na ito ay isang paraan upang masolusyunan ang problema.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

In the Philippines, there are 2.1 million child labourers aged 5 to 17 years old based on the 2011 Survey on Children of the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA). About 95 per cent of them are in hazardous work. Sixty-nine per cent of these are aged 15 to 17 years old, beyond the minimum allowable age for work but still exposed to hazardous work.

Childhope Philippines and Our Crusade Against Child Labor. Childhope Philippines fights an uphill battle in promoting and protecting children's rights on the city streets. The urban poor children who work on the streets of Metro Manila alone number between 50,000 to 70,000, while 50,000 is also the number of known Filipino domestic workers as ...

In 2022, the Philippines made moderate advancement in efforts to eliminate the worst forms of child labor. The government enacted the Expanded Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act to hold private sector entities responsible for addressing human trafficking. It also enacted the Anti-Online Sexual Abuse or Exploitation of Children and Anti-Child ...

Child labor in PH. In the Philippines, as of 2020, there were 872,300 children aged 5 to 17 years old in child labor—or 2.8 percent of the age group's total population, pegged at around ...

Child labour in the Philippines continues to affect an estimated 2.1 million children aged 5-17 years, about eight percent of this age group, according to the results of the Philippines 2011 Survey on Children (SOC, 2011).3 These numbers indicate clearly that the struggle against child labour has not yet been won in the country, and ...

there was a substantial reduction in demand for labor (including child labor) because of these factors, despite the increased labor force participation among children. • Of course the drop in the measured incidence of child labor between 1995 and 1998 could have been due to advocacy efforts already bearing some impact.

The Philippine child labor literature presents dete rminants of child labor that can be generally . categorized as either economic or sociocultura l. Essentially, the economic factors c an be .

The study aims: 1) to analyze the causes and consequences of child labor in the Philippines; and 2) to provide recommendations that will be the basis for developing integrated and sustainable interventions and/or enhancing existing government policies and programs, both economic and social, to address child labor. The influence of macro level parameters on households¿ decisions to allow ...

Children in the Philippines engage in the worst forms of child labor, including in commercial sexual exploitation, sometimes as a result of human trafficking, and in armed conflict. Children also perform dangerous tasks in agriculture and gold mining. (1-3,4-7) The Survey on Children indicated that 3.2 million children ages 5 to 17 engage in ...

study to review all the important studies available on child labor and assess key government policies affecting child labor in the Philippines. The paper provides an overview of the nature, extent and predominant forms of child labor in the country based on available data disaggregated by age, sex, geographic distribution, industry, and occupation.

This paper analyses the supply-side socioeconomic determinants of child labour in the Philippines using data from the National Household Survey and the Labour Force Survey of the Philippines. The research methodology is that of a sequential probit model which assumes that household decisions are made in a hierarchical manner.

At that time, that number represented 28% of the total population of that age group. Since then, child labour has continued to grow. In 1994, there were some 5 to 7 million working children in the Philippines (Sancho-Liao, 1994). Of those, 1.5 to 2 million were below the age of 10.

The authorities also cited the existence of child labor cases in the Poblacions in the provinces of Southern Leyte, Samar, Eastern Samar and Biliran. In Tacloban City, child labor cases were recorded from the four biggest barangays namely Barangay 37, Seawall District, Barangay 106 Sto. Nino, Barangay 1 and 4, which is located near the port area.

500 Words Essay on Child Labor In The Philippines What is Child Labor? Child labor is when kids under the age of 18 work. This work is often bad for their health and stops them from going to school. Many countries, including the Philippines, face this problem. In the Philippines, many children have to work to help their families earn money.

Philippine society, culture and history. Defining the problem: What is child labor? Child labor is the participation of children in a wide variety of work situations, on a more or less regular basis, to earn a livelihood for themselves or for others. Children's work may be paid or unpaid, and remuneration for their efforts may be made to adults

Abstract. It is the right of every child to have a healthy environment, formal education, and a loving family. However, poverty forces a child to work even in dangerous streets. In the Philippines, the Child Protection Law defined children as persons below eighteen (18) years of age or those over but are unable to fully take care of themselves ...

In mining towns, child labor incidence was 14 percent. The group noted that the youngest worker interviewed in the study was five years old, although the common age of child workers was 12. The ...

Of the estimated 597 thousand working children engaged in child labor in 2020, 435 thousand or 72.8 percent of them were boys while 162 thousand or 27.2 percent were girls. (Figure 5 and Table D) Across age groups, the largest proportion of working children considered engaged in child labor were in the ages 15 to 17 years at 73.3 percent in 2020.

Child Labor Trafficking in the Philippines. Child labor is defined as a work that deprives children of their childhood, their potential and dignity, and that is harmful to physical and mental development. A 2011 study by the International Labor Organization found out that there are 3.2 million Filipino children, age 5-17 years old, are engaged ...

† Determined by national law or regulation as hazardous and, as such, relevant to Article 3(d) of ILO C. 182. ‡ Child labor understood as the worst forms of child labor per se under Article 3(a)-(c) of ILO C. 182.. Philippine children are victims of online sexual abuse and exploitation of children (OSAEC), in which children perform sex acts at the direction of paying foreigners and local ...

Essay About Child Labour In The Philippines. Child Labor Child Labor According to a survey financed by the International Labor Organization (June 2011) there are 5.59 million child laborers toiling in the Philippines and almost of them are weakening in hazardous conditions. Hazardous child labor is defined as being likely to harm children's ...

It also assesses the terrain of child labor in the Philippines, and the research and advocacy experiences of those who have spent time to study such a complex, seemingly invisible reality in the 10 years between 1986-1995. ... A Review of Selected Studies and Policy Papers. Rosario Del Rosario, Melinda A. Bonga. Office of the Vice Chancellor ...

The sugar mills keep all of this — child marriage, underage labor, wage debt and working conditions — at an arm's length. Child marriage, they say, is a social problem that has nothing to do ...

ILO in the Philippines; Publications; ... (4Ps) upang ipalaganap ang pagkakaroon ng child labour-free na komunidad. Ito ay magsisilbing gabay ng mga katuwang na benepisyaryo para makakuha ng sapat na kaalaman, kakayahan, at saloobin upang matukoy ang isyu ng batang manggagawa. Bibigyang kapangyarihan nito ang mga gagamit sa: (a) pagpapakita ng ...