Literary Devices & Terms

An acrostic is a piece of writing in which a particular set of letters—typically the first letter of each line, word, or paragraph—spells out a word or phrase with special significance to the text. Acrostics... (read full acrostic explanation with examples) An acrostic is a piece of writing in which a particular set of letters—typically the first letter of each line,... (read more)

An allegory is a work that conveys a hidden meaning—usually moral, spiritual, or political—through the use of symbolic characters and events. The story of "The Tortoise and The Hare" is a well-known allegory with a... (read full allegory explanation with examples) An allegory is a work that conveys a hidden meaning—usually moral, spiritual, or political—through the use of symbolic characters and... (read more)

Alliteration is a figure of speech in which the same sound repeats in a group of words, such as the “b” sound in: “Bob brought the box of bricks to the basement.” The repeating sound... (read full alliteration explanation with examples) Alliteration is a figure of speech in which the same sound repeats in a group of words, such as the... (read more)

In literature, an allusion is an unexplained reference to someone or something outside of the text. Writers commonly allude to other literary works, famous individuals, historical events, or philosophical ideas, and they do so in... (read full allusion explanation with examples) In literature, an allusion is an unexplained reference to someone or something outside of the text. Writers commonly allude to... (read more)

An anachronism is a person or a thing placed in the wrong time period. For instance, if a novel set in Medieval England featured a trip to a movie-theater, that would be an anachronism. Although... (read full anachronism explanation with examples) An anachronism is a person or a thing placed in the wrong time period. For instance, if a novel set... (read more)

Anadiplosis is a figure of speech in which a word or group of words located at the end of one clause or sentence is repeated at or near the beginning of the following clause or... (read full anadiplosis explanation with examples) Anadiplosis is a figure of speech in which a word or group of words located at the end of one... (read more)

An analogy is a comparison that aims to explain a thing or idea by likening it to something else. For example, a career coach might say, "Being the successful boss or CEO of a company... (read full analogy explanation with examples) An analogy is a comparison that aims to explain a thing or idea by likening it to something else. For... (read more)

An anapest is a three-syllable metrical pattern in poetry in which two unstressed syllables are followed by a stressed syllable. The word "understand" is an anapest, with the unstressed syllables of "un" and "der" followed... (read full anapest explanation with examples) An anapest is a three-syllable metrical pattern in poetry in which two unstressed syllables are followed by a stressed syllable.... (read more)

Anaphora is a figure of speech in which words repeat at the beginning of successive clauses, phrases, or sentences. For example, Martin Luther King's famous "I Have a Dream" speech contains anaphora: "So let freedom... (read full anaphora explanation with examples) Anaphora is a figure of speech in which words repeat at the beginning of successive clauses, phrases, or sentences. For... (read more)

An antagonist is usually a character who opposes the protagonist (or main character) of a story, but the antagonist can also be a group of characters, institution, or force against which the protagonist must contend.... (read full antagonist explanation with examples) An antagonist is usually a character who opposes the protagonist (or main character) of a story, but the antagonist can... (read more)

Antanaclasis is a figure of speech in which a word or phrase is repeated within a sentence, but the word or phrase means something different each time it appears. A famous example of antanaclasis is... (read full antanaclasis explanation with examples) Antanaclasis is a figure of speech in which a word or phrase is repeated within a sentence, but the word... (read more)

Anthropomorphism is the attribution of human characteristics, emotions, and behaviors to animals or other non-human things (including objects, plants, and supernatural beings). Some famous examples of anthropomorphism include Winnie the Pooh, the Little Engine that Could, and Simba from... (read full anthropomorphism explanation with examples) Anthropomorphism is the attribution of human characteristics, emotions, and behaviors to animals or other non-human things (including objects, plants, and supernatural beings). Some famous... (read more)

Antimetabole is a figure of speech in which a phrase is repeated, but with the order of words reversed. John F. Kennedy's words, "Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you... (read full antimetabole explanation with examples) Antimetabole is a figure of speech in which a phrase is repeated, but with the order of words reversed. John... (read more)

Antithesis is a figure of speech that juxtaposes two contrasting or opposing ideas, usually within parallel grammatical structures. For instance, Neil Armstrong used antithesis when he stepped onto the surface of the moon in 1969... (read full antithesis explanation with examples) Antithesis is a figure of speech that juxtaposes two contrasting or opposing ideas, usually within parallel grammatical structures. For instance,... (read more)

An aphorism is a saying that concisely expresses a moral principle or an observation about the world, presenting it as a general or universal truth. The Rolling Stones are responsible for penning one of the... (read full aphorism explanation with examples) An aphorism is a saying that concisely expresses a moral principle or an observation about the world, presenting it as... (read more)

Aphorismus is a type of figure of speech that calls into question the way a word is used. Aphorismus is used not to question the meaning of a word, but whether it is actually appropriate... (read full aphorismus explanation with examples) Aphorismus is a type of figure of speech that calls into question the way a word is used. Aphorismus is... (read more)

Aporia is a rhetorical device in which a speaker expresses uncertainty or doubt—often pretended uncertainty or doubt—about something, usually as a way of proving a point. An example of aporia is the famous Elizabeth Barrett... (read full aporia explanation with examples) Aporia is a rhetorical device in which a speaker expresses uncertainty or doubt—often pretended uncertainty or doubt—about something, usually as... (read more)

Apostrophe is a figure of speech in which a speaker directly addresses someone (or something) that is not present or cannot respond in reality. The entity being addressed can be an absent, dead, or imaginary... (read full apostrophe explanation with examples) Apostrophe is a figure of speech in which a speaker directly addresses someone (or something) that is not present or... (read more)

Assonance is a figure of speech in which the same vowel sound repeats within a group of words. An example of assonance is: "Who gave Newt and Scooter the blue tuna? It was too soon!" (read full assonance explanation with examples) Assonance is a figure of speech in which the same vowel sound repeats within a group of words. An example... (read more)

An asyndeton (sometimes called asyndetism) is a figure of speech in which coordinating conjunctions—words such as "and", "or", and "but" that join other words or clauses in a sentence into relationships of equal importance—are omitted.... (read full asyndeton explanation with examples) An asyndeton (sometimes called asyndetism) is a figure of speech in which coordinating conjunctions—words such as "and", "or", and "but"... (read more)

A ballad is a type of poem that tells a story and was traditionally set to music. English language ballads are typically composed of four-line stanzas that follow an ABCB rhyme scheme. (read full ballad explanation with examples) A ballad is a type of poem that tells a story and was traditionally set to music. English language ballads... (read more)

A ballade is a form of lyric poetry that originated in medieval France. Ballades follow a strict rhyme scheme ("ababbcbc"), and typically have three eight-line stanzas followed by a shorter four-line stanza called an envoi.... (read full ballade explanation with examples) A ballade is a form of lyric poetry that originated in medieval France. Ballades follow a strict rhyme scheme ("ababbcbc"),... (read more)

Bildungsroman is a genre of novel that shows a young protagonist's journey from childhood to adulthood (or immaturity to maturity), with a focus on the trials and misfortunes that affect the character's growth. (read full bildungsroman explanation with examples) Bildungsroman is a genre of novel that shows a young protagonist's journey from childhood to adulthood (or immaturity to maturity),... (read more)

Blank verse is the name given to poetry that lacks rhymes but does follow a specific meter—a meter that is almost always iambic pentameter. Blank verse was particularly popular in English poetry written between the... (read full blank verse explanation with examples) Blank verse is the name given to poetry that lacks rhymes but does follow a specific meter—a meter that is... (read more)

A cacophony is a combination of words that sound harsh or unpleasant together, usually because they pack a lot of percussive or "explosive" consonants (like T, P, or K) into relatively little space. For instance, the... (read full cacophony explanation with examples) A cacophony is a combination of words that sound harsh or unpleasant together, usually because they pack a lot of... (read more)

A caesura is a pause that occurs within a line of poetry, usually marked by some form of punctuation such as a period, comma, ellipsis, or dash. A caesura doesn't have to be placed in... (read full caesura explanation with examples) A caesura is a pause that occurs within a line of poetry, usually marked by some form of punctuation such... (read more)

Catharsis is the process of releasing strong or pent-up emotions through art. Aristotle coined the term catharsis—which comes from the Greek kathairein meaning "to cleanse or purge"—to describe the release of emotional tension that he... (read full catharsis explanation with examples) Catharsis is the process of releasing strong or pent-up emotions through art. Aristotle coined the term catharsis—which comes from the... (read more)

Characterization is the representation of the traits, motives, and psychology of a character in a narrative. Characterization may occur through direct description, in which the character's qualities are described by a narrator, another character, or... (read full characterization explanation with examples) Characterization is the representation of the traits, motives, and psychology of a character in a narrative. Characterization may occur through... (read more)

Chiasmus is a figure of speech in which the grammar of one phrase is inverted in the following phrase, such that two key concepts from the original phrase reappear in the second phrase in inverted... (read full chiasmus explanation with examples) Chiasmus is a figure of speech in which the grammar of one phrase is inverted in the following phrase, such... (read more)

The word cinquain can refer to two different things. Historically, it referred to any stanza of five lines written in any type of verse. More recently, cinquain has come to refer to particular types of... (read full cinquain explanation with examples) The word cinquain can refer to two different things. Historically, it referred to any stanza of five lines written in... (read more)

A cliché is a phrase that, due to overuse, is seen as lacking in substance or originality. For example, telling a heartbroken friend that there are "Plenty of fish in the sea" is such a... (read full cliché explanation with examples) A cliché is a phrase that, due to overuse, is seen as lacking in substance or originality. For example, telling... (read more)

Climax is a figure of speech in which successive words, phrases, clauses, or sentences are arranged in ascending order of importance, as in "Look! Up in the sky! It's a bird! It's a plane! It's... (read full climax (figure of speech) explanation with examples) Climax is a figure of speech in which successive words, phrases, clauses, or sentences are arranged in ascending order of... (read more)

The climax of a plot is the story's central turning point—the moment of peak tension or conflict—which all the preceding plot developments have been leading up to. In a traditional "good vs. evil" story (like many superhero movies)... (read full climax (plot) explanation with examples) The climax of a plot is the story's central turning point—the moment of peak tension or conflict—which all the preceding plot... (read more)

Colloquialism is the use of informal words or phrases in writing or speech. Colloquialisms are usually defined in geographical terms, meaning that they are often defined by their use within a dialect, a regionally-defined variant... (read full colloquialism explanation with examples) Colloquialism is the use of informal words or phrases in writing or speech. Colloquialisms are usually defined in geographical terms,... (read more)

Common meter is a specific type of meter that is often used in lyric poetry. Common meter has two key traits: it alternates between lines of eight syllables and lines of six syllables, and it... (read full common meter explanation with examples) Common meter is a specific type of meter that is often used in lyric poetry. Common meter has two key... (read more)

A conceit is a fanciful metaphor, especially a highly elaborate or extended metaphor in which an unlikely, far-fetched, or strained comparison is made between two things. A famous example comes from John Donne's poem, "A... (read full conceit explanation with examples) A conceit is a fanciful metaphor, especially a highly elaborate or extended metaphor in which an unlikely, far-fetched, or strained... (read more)

Connotation is the array of emotions and ideas suggested by a word in addition to its dictionary definition. Most words carry meanings, impressions, or associations apart from or beyond their literal meaning. For example, the... (read full connotation explanation with examples) Connotation is the array of emotions and ideas suggested by a word in addition to its dictionary definition. Most words... (read more)

Consonance is a figure of speech in which the same consonant sound repeats within a group of words. An example of consonance is: "Traffic figures, on July Fourth, to be tough." (read full consonance explanation with examples) Consonance is a figure of speech in which the same consonant sound repeats within a group of words. An example... (read more)

A couplet is a unit of two lines of poetry, especially lines that use the same or similar meter, form a rhyme, or are separated from other lines by a double line break. (read full couplet explanation with examples) A couplet is a unit of two lines of poetry, especially lines that use the same or similar meter, form... (read more)

A dactyl is a three-syllable metrical pattern in poetry in which a stressed syllable is followed by two unstressed syllables. The word “poetry” itself is a great example of a dactyl, with the stressed syllable... (read full dactyl explanation with examples) A dactyl is a three-syllable metrical pattern in poetry in which a stressed syllable is followed by two unstressed syllables.... (read more)

Denotation is the literal meaning, or "dictionary definition," of a word. Denotation is defined in contrast to connotation, which is the array of emotions and ideas suggested by a word in addition to its dictionary... (read full denotation explanation with examples) Denotation is the literal meaning, or "dictionary definition," of a word. Denotation is defined in contrast to connotation, which is... (read more)

The dénouement is the final section of a story's plot, in which loose ends are tied up, lingering questions are answered, and a sense of resolution is achieved. The shortest and most well known dénouement, it could be... (read full dénouement explanation with examples) The dénouement is the final section of a story's plot, in which loose ends are tied up, lingering questions are answered, and... (read more)

A deus ex machina is a plot device whereby an unsolvable conflict or point of tension is suddenly resolved by the unexpected appearance of an implausible character, object, action, ability, or event. For example, if... (read full deus ex machina explanation with examples) A deus ex machina is a plot device whereby an unsolvable conflict or point of tension is suddenly resolved by... (read more)

Diacope is a figure of speech in which a word or phrase is repeated with a small number of intervening words. The first line of Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy, "Happy families are all alike;... (read full diacope explanation with examples) Diacope is a figure of speech in which a word or phrase is repeated with a small number of intervening... (read more)

Dialogue is the exchange of spoken words between two or more characters in a book, play, or other written work. In prose writing, lines of dialogue are typically identified by the use of quotation marks... (read full dialogue explanation with examples) Dialogue is the exchange of spoken words between two or more characters in a book, play, or other written work.... (read more)

Diction is a writer's unique style of expression, especially his or her choice and arrangement of words. A writer's vocabulary, use of language to produce a specific tone or atmosphere, and ability to communicate clearly... (read full diction explanation with examples) Diction is a writer's unique style of expression, especially his or her choice and arrangement of words. A writer's vocabulary,... (read more)

Dramatic irony is a plot device often used in theater, literature, film, and television to highlight the difference between a character's understanding of a given situation, and that of the audience. More specifically, in dramatic... (read full dramatic irony explanation with examples) Dramatic irony is a plot device often used in theater, literature, film, and television to highlight the difference between a... (read more)

A dynamic character undergoes substantial internal changes as a result of one or more plot developments. The dynamic character's change can be extreme or subtle, as long as his or her development is important to... (read full dynamic character explanation with examples) A dynamic character undergoes substantial internal changes as a result of one or more plot developments. The dynamic character's change... (read more)

An elegy is a poem of serious reflection, especially one mourning the loss of someone who died. Elegies are defined by their subject matter, and don't have to follow any specific form in terms of... (read full elegy explanation with examples) An elegy is a poem of serious reflection, especially one mourning the loss of someone who died. Elegies are defined... (read more)

End rhyme refers to rhymes that occur in the final words of lines of poetry. For instance, these lines from Dorothy Parker's poem "Interview" use end rhyme: "The ladies men admire, I’ve heard, / Would shudder... (read full end rhyme explanation with examples) End rhyme refers to rhymes that occur in the final words of lines of poetry. For instance, these lines from... (read more)

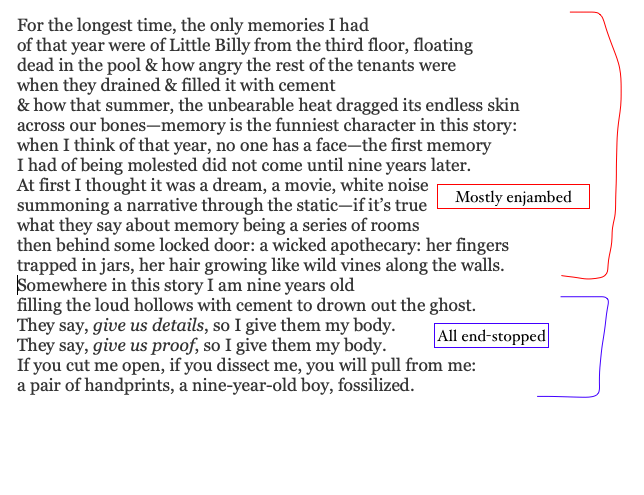

An end-stopped line is a line of poetry in which a sentence or phrase comes to a conclusion at the end of the line. For example, the poet C.P. Cavafy uses end-stopped lines in his... (read full end-stopped line explanation with examples) An end-stopped line is a line of poetry in which a sentence or phrase comes to a conclusion at the... (read more)

Enjambment is the continuation of a sentence or clause across a line break. For example, the poet John Donne uses enjambment in his poem "The Good-Morrow" when he continues the opening sentence across the line... (read full enjambment explanation with examples) Enjambment is the continuation of a sentence or clause across a line break. For example, the poet John Donne uses... (read more)

An envoi is a brief concluding stanza at the end of a poem that can either summarize the preceding poem or serve as its dedication. The envoi tends to follow the same meter and rhyme... (read full envoi explanation with examples) An envoi is a brief concluding stanza at the end of a poem that can either summarize the preceding poem... (read more)

Epanalepsis is a figure of speech in which the beginning of a clause or sentence is repeated at the end of that same clause or sentence, with words intervening. The sentence "The king is dead,... (read full epanalepsis explanation with examples) Epanalepsis is a figure of speech in which the beginning of a clause or sentence is repeated at the end... (read more)

An epigram is a short and witty statement, usually written in verse, that conveys a single thought or observation. Epigrams typically end with a punchline or a satirical twist. (read full epigram explanation with examples) An epigram is a short and witty statement, usually written in verse, that conveys a single thought or observation. Epigrams... (read more)

An epigraph is a short quotation, phrase, or poem that is placed at the beginning of another piece of writing to encapsulate that work's main themes and to set the tone. For instance, the epigraph of Mary... (read full epigraph explanation with examples) An epigraph is a short quotation, phrase, or poem that is placed at the beginning of another piece of writing to... (read more)

Epistrophe is a figure of speech in which one or more words repeat at the end of successive phrases, clauses, or sentences. In his Gettysburg Address, Abraham Lincoln urged the American people to ensure that,... (read full epistrophe explanation with examples) Epistrophe is a figure of speech in which one or more words repeat at the end of successive phrases, clauses,... (read more)

Epizeuxis is a figure of speech in which a word or phrase is repeated in immediate succession, with no intervening words. In the play Hamlet, when Hamlet responds to a question about what he's reading... (read full epizeuxis explanation with examples) Epizeuxis is a figure of speech in which a word or phrase is repeated in immediate succession, with no intervening... (read more)

Ethos, along with logos and pathos, is one of the three "modes of persuasion" in rhetoric (the art of effective speaking or writing). Ethos is an argument that appeals to the audience by emphasizing the... (read full ethos explanation with examples) Ethos, along with logos and pathos, is one of the three "modes of persuasion" in rhetoric (the art of effective... (read more)

Euphony is the combining of words that sound pleasant together or are easy to pronounce, usually because they contain lots of consonants with soft or muffled sounds (like L, M, N, and R) instead of consonants with harsh, percussive sounds (like... (read full euphony explanation with examples) Euphony is the combining of words that sound pleasant together or are easy to pronounce, usually because they contain lots of consonants with soft... (read more)

Exposition is the description or explanation of background information within a work of literature. Exposition can cover characters and their relationship to one another, the setting or time and place of events, as well as... (read full exposition explanation with examples) Exposition is the description or explanation of background information within a work of literature. Exposition can cover characters and their... (read more)

An extended metaphor is a metaphor that unfolds across multiple lines or even paragraphs of a text, making use of multiple interrelated metaphors within an overarching one. So while "life is a highway" is a... (read full extended metaphor explanation with examples) An extended metaphor is a metaphor that unfolds across multiple lines or even paragraphs of a text, making use of... (read more)

An external conflict is a problem, antagonism, or struggle that takes place between a character and an outside force. External conflict drives the action of a plot forward. (read full external conflict explanation with examples) An external conflict is a problem, antagonism, or struggle that takes place between a character and an outside force. External conflict... (read more)

The falling action of a story is the section of the plot following the climax, in which the tension stemming from the story's central conflict decreases and the story moves toward its conclusion. For instance, the traditional "good... (read full falling action explanation with examples) The falling action of a story is the section of the plot following the climax, in which the tension stemming from... (read more)

Figurative language is language that contains or uses figures of speech. When people use the term "figurative language," however, they often do so in a slightly narrower way. In this narrower definition, figurative language refers... (read full figurative language explanation with examples) Figurative language is language that contains or uses figures of speech. When people use the term "figurative language," however, they... (read more)

A figure of speech is a literary device in which language is used in an unusual—or "figured"—way in order to produce a stylistic effect. Figures of speech can be broken into two main groups: figures... (read full figure of speech explanation with examples) A figure of speech is a literary device in which language is used in an unusual—or "figured"—way in order to... (read more)

A character is said to be "flat" if it is one-dimensional or lacking in complexity. Typically, flat characters can be easily and accurately described using a single word (like "bully") or one short sentence (like "A naive... (read full flat character explanation with examples) A character is said to be "flat" if it is one-dimensional or lacking in complexity. Typically, flat characters can be easily... (read more)

Foreshadowing is a literary device in which authors hint at plot developments that don't actually occur until later in the story. Foreshadowing can be achieved directly or indirectly, by making explicit statements or leaving subtle... (read full foreshadowing explanation with examples) Foreshadowing is a literary device in which authors hint at plot developments that don't actually occur until later in the... (read more)

Formal verse is the name given to rhymed poetry that uses a strict meter (a regular pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables). This two-line poem by Emily Dickinson is formal verse because it rhymes and... (read full formal verse explanation with examples) Formal verse is the name given to rhymed poetry that uses a strict meter (a regular pattern of stressed and... (read more)

Free verse is the name given to poetry that doesn’t use any strict meter or rhyme scheme. Because it has no set meter, poems written in free verse can have lines of any length, from... (read full free verse explanation with examples) Free verse is the name given to poetry that doesn’t use any strict meter or rhyme scheme. Because it has... (read more)

Hamartia is a literary term that refers to a tragic flaw or error that leads to a character's downfall. In the novel Frankenstein, Victor Frankenstein's arrogant conviction that he can usurp the roles of God... (read full hamartia explanation with examples) Hamartia is a literary term that refers to a tragic flaw or error that leads to a character's downfall. In... (read more)

Hubris refers to excessive pride or overconfidence, which drives a person to overstep limits in a way that leads to their downfall. In Greek mythology, the legend of Icarus involves an iconic case of hubris:... (read full hubris explanation with examples) Hubris refers to excessive pride or overconfidence, which drives a person to overstep limits in a way that leads to... (read more)

Hyperbole is a figure of speech in which a writer or speaker exaggerates for the sake of emphasis. Hyperbolic statements are usually quite obvious exaggerations intended to emphasize a point, rather than be taken literally.... (read full hyperbole explanation with examples) Hyperbole is a figure of speech in which a writer or speaker exaggerates for the sake of emphasis. Hyperbolic statements... (read more)

An iamb is a two-syllable metrical pattern in poetry in which one unstressed syllable is followed by a stressed syllable. The word "define" is an iamb, with the unstressed syllable of "de" followed by the... (read full iamb explanation with examples) An iamb is a two-syllable metrical pattern in poetry in which one unstressed syllable is followed by a stressed syllable.... (read more)

An idiom is a phrase that conveys a figurative meaning that is difficult or impossible to understand based solely on a literal interpretation of the words in the phrase. For example, saying that something is... (read full idiom explanation with examples) An idiom is a phrase that conveys a figurative meaning that is difficult or impossible to understand based solely on... (read more)

Imagery, in any sort of writing, refers to descriptive language that engages the human senses. For instance, the following lines from Robert Frost's poem "After Apple-Picking" contain imagery that engages the senses of touch, movement,... (read full imagery explanation with examples) Imagery, in any sort of writing, refers to descriptive language that engages the human senses. For instance, the following lines... (read more)

Internal rhyme is rhyme that occurs in the middle of lines of poetry, instead of at the ends of lines. A single line of poetry can contain internal rhyme (with multiple words in the same... (read full internal rhyme explanation with examples) Internal rhyme is rhyme that occurs in the middle of lines of poetry, instead of at the ends of lines.... (read more)

Irony is a literary device or event in which how things seem to be is in fact very different from how they actually are. If this seems like a loose definition, don't worry—it is. Irony is a... (read full irony explanation with examples) Irony is a literary device or event in which how things seem to be is in fact very different from how... (read more)

Juxtaposition occurs when an author places two things side by side as a way of highlighting their differences. Ideas, images, characters, and actions are all things that can be juxtaposed with one another. For example,... (read full juxtaposition explanation with examples) Juxtaposition occurs when an author places two things side by side as a way of highlighting their differences. Ideas, images,... (read more)

A kenning is a figure of speech in which two words are combined in order to form a poetic expression that refers to a person or a thing. For example, "whale-road" is a kenning for... (read full kenning explanation with examples) A kenning is a figure of speech in which two words are combined in order to form a poetic expression... (read more)

A line break is the termination of one line of poetry, and the beginning of a new line. (read full line break explanation with examples) A line break is the termination of one line of poetry, and the beginning of a new line. (read more)

Litotes is a figure of speech and a form of understatement in which a sentiment is expressed ironically by negating its contrary. For example, saying "It's not the best weather today" during a hurricane would... (read full litotes explanation with examples) Litotes is a figure of speech and a form of understatement in which a sentiment is expressed ironically by negating... (read more)

Logos, along with ethos and pathos, is one of the three "modes of persuasion" in rhetoric (the art of effective speaking or writing). Logos is an argument that appeals to an audience's sense of logic... (read full logos explanation with examples) Logos, along with ethos and pathos, is one of the three "modes of persuasion" in rhetoric (the art of effective... (read more)

A metaphor is a figure of speech that compares two different things by saying that one thing is the other. The comparison in a metaphor can be stated explicitly, as in the sentence "Love is... (read full metaphor explanation with examples) A metaphor is a figure of speech that compares two different things by saying that one thing is the other.... (read more)

Meter is a regular pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables that defines the rhythm of some poetry. These stress patterns are defined in groupings, called feet, of two or three syllables. A pattern of unstressed-stressed,... (read full meter explanation with examples) Meter is a regular pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables that defines the rhythm of some poetry. These stress patterns... (read more)

Metonymy is a type of figurative language in which an object or concept is referred to not by its own name, but instead by the name of something closely associated with it. For example, in... (read full metonymy explanation with examples) Metonymy is a type of figurative language in which an object or concept is referred to not by its own... (read more)

The mood of a piece of writing is its general atmosphere or emotional complexion—in short, the array of feelings the work evokes in the reader. Every aspect of a piece of writing can influence its mood, from the... (read full mood explanation with examples) The mood of a piece of writing is its general atmosphere or emotional complexion—in short, the array of feelings the work evokes... (read more)

A motif is an element or idea that recurs throughout a work of literature. Motifs, which are often collections of related symbols, help develop the central themes of a book or play. For example, one... (read full motif explanation with examples) A motif is an element or idea that recurs throughout a work of literature. Motifs, which are often collections of... (read more)

A narrative is an account of connected events. Two writers describing the same set of events might craft very different narratives, depending on how they use different narrative elements, such as tone or point of view. For... (read full narrative explanation with examples) A narrative is an account of connected events. Two writers describing the same set of events might craft very different narratives,... (read more)

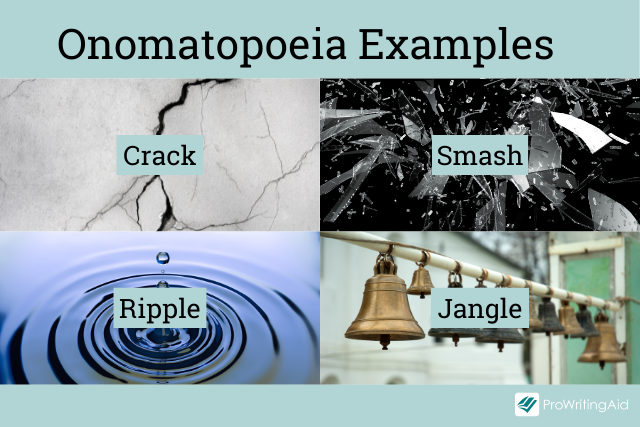

Onomatopoeia is a figure of speech in which words evoke the actual sound of the thing they refer to or describe. The “boom” of a firework exploding, the “tick tock” of a clock, and the... (read full onomatopoeia explanation with examples) Onomatopoeia is a figure of speech in which words evoke the actual sound of the thing they refer to or... (read more)

An oxymoron is a figure of speech in which two contradictory terms or ideas are intentionally paired in order to make a point—particularly to reveal a deeper or hidden truth. The most recognizable oxymorons are... (read full oxymoron explanation with examples) An oxymoron is a figure of speech in which two contradictory terms or ideas are intentionally paired in order to... (read more)

A paradox is a figure of speech that seems to contradict itself, but which, upon further examination, contains some kernel of truth or reason. Oscar Wilde's famous declaration that "Life is much too important to be... (read full paradox explanation with examples) A paradox is a figure of speech that seems to contradict itself, but which, upon further examination, contains some kernel... (read more)

Parallelism is a figure of speech in which two or more elements of a sentence (or series of sentences) have the same grammatical structure. These "parallel" elements can be used to intensify the rhythm of... (read full parallelism explanation with examples) Parallelism is a figure of speech in which two or more elements of a sentence (or series of sentences) have... (read more)

Parataxis is a figure of speech in which words, phrases, clauses, or sentences are set next to each other so that each element is equally important. Parataxis usually involves simple sentences or phrases whose relationships... (read full parataxis explanation with examples) Parataxis is a figure of speech in which words, phrases, clauses, or sentences are set next to each other so... (read more)

A parody is a work that mimics the style of another work, artist, or genre in an exaggerated way, usually for comic effect. Parodies can take many forms, including fiction, poetry, film, visual art, and... (read full parody explanation with examples) A parody is a work that mimics the style of another work, artist, or genre in an exaggerated way, usually... (read more)

Pathetic fallacy occurs when a writer attributes human emotions to things that aren't human, such as objects, weather, or animals. It is often used to make the environment reflect the inner experience of a narrator... (read full pathetic fallacy explanation with examples) Pathetic fallacy occurs when a writer attributes human emotions to things that aren't human, such as objects, weather, or animals.... (read more)

Pathos, along with logos and ethos, is one of the three "modes of persuasion" in rhetoric (the art of effective speaking or writing). Pathos is an argument that appeals to an audience's emotions. When a... (read full pathos explanation with examples) Pathos, along with logos and ethos, is one of the three "modes of persuasion" in rhetoric (the art of effective... (read more)

Personification is a type of figurative language in which non-human things are described as having human attributes, as in the sentence, "The rain poured down on the wedding guests, indifferent to their plans." Describing the... (read full personification explanation with examples) Personification is a type of figurative language in which non-human things are described as having human attributes, as in the... (read more)

Plot is the sequence of interconnected events within the story of a play, novel, film, epic, or other narrative literary work. More than simply an account of what happened, plot reveals the cause-and-effect relationships between... (read full plot explanation with examples) Plot is the sequence of interconnected events within the story of a play, novel, film, epic, or other narrative literary... (read more)

Point of view refers to the perspective that the narrator holds in relation to the events of the story. The three primary points of view are first person, in which the narrator tells a story from... (read full point of view explanation with examples) Point of view refers to the perspective that the narrator holds in relation to the events of the story. The... (read more)

Polyptoton is a figure of speech that involves the repetition of words derived from the same root (such as "blood" and "bleed"). For instance, the question, "Who shall watch the watchmen?" is an example of... (read full polyptoton explanation with examples) Polyptoton is a figure of speech that involves the repetition of words derived from the same root (such as "blood"... (read more)

Polysyndeton is a figure of speech in which coordinating conjunctions—words such as "and," "or," and "but" that join other words or clauses in a sentence into relationships of equal importance—are used several times in close... (read full polysyndeton explanation with examples) Polysyndeton is a figure of speech in which coordinating conjunctions—words such as "and," "or," and "but" that join other words... (read more)

The protagonist of a story is its main character, who has the sympathy and support of the audience. This character tends to be involved in or affected by most of the choices or conflicts that... (read full protagonist explanation with examples) The protagonist of a story is its main character, who has the sympathy and support of the audience. This character... (read more)

A pun is a figure of speech that plays with words that have multiple meanings, or that plays with words that sound similar but mean different things. The comic novelist Douglas Adams uses both types... (read full pun explanation with examples) A pun is a figure of speech that plays with words that have multiple meanings, or that plays with words... (read more)

A quatrain is a four-line stanza of poetry. It can be a single four-line stanza, meaning that it is a stand-alone poem of four lines, or it can be a four-line stanza that makes up... (read full quatrain explanation with examples) A quatrain is a four-line stanza of poetry. It can be a single four-line stanza, meaning that it is a... (read more)

A red herring is a piece of information in a story that distracts readers from an important truth, or leads them to mistakenly expect a particular outcome. Most often, the term red herring is used to refer... (read full red herring explanation with examples) A red herring is a piece of information in a story that distracts readers from an important truth, or leads them... (read more)

In a poem or song, a refrain is a line or group of lines that regularly repeat, usually at the end of a stanza in a poem or at the end of a verse in... (read full refrain explanation with examples) In a poem or song, a refrain is a line or group of lines that regularly repeat, usually at the... (read more)

Repetition is a literary device in which a word or phrase is repeated two or more times. Repetition occurs in so many different forms that it is usually not thought of as a single figure... (read full repetition explanation with examples) Repetition is a literary device in which a word or phrase is repeated two or more times. Repetition occurs in... (read more)

A rhetorical question is a figure of speech in which a question is asked for a reason other than to get an answer—most commonly, it's asked to make a persuasive point. For example, if a... (read full rhetorical question explanation with examples) A rhetorical question is a figure of speech in which a question is asked for a reason other than to... (read more)

A rhyme is a repetition of similar sounds in two or more words. Rhyming is particularly common in many types of poetry, especially at the ends of lines, and is a requirement in formal verse.... (read full rhyme explanation with examples) A rhyme is a repetition of similar sounds in two or more words. Rhyming is particularly common in many types... (read more)

A rhyme scheme is the pattern according to which end rhymes (rhymes located at the end of lines) are repeated in works poetry. Rhyme schemes are described using letters of the alphabet, such that all... (read full rhyme scheme explanation with examples) A rhyme scheme is the pattern according to which end rhymes (rhymes located at the end of lines) are repeated... (read more)

The rising action of a story is the section of the plot leading up to the climax, in which the tension stemming from the story's central conflict grows through successive plot developments. For example, in the story of "Little... (read full rising action explanation with examples) The rising action of a story is the section of the plot leading up to the climax, in which the tension stemming... (read more)

A character is said to be "round" if they are lifelike or complex. Round characters typically have fully fleshed-out and multi-faceted personalities, backgrounds, desires, and motivations. Jay Gatsby in F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby... (read full round character explanation with examples) A character is said to be "round" if they are lifelike or complex. Round characters typically have fully fleshed-out and... (read more)

Satire is the use of humor, irony, sarcasm, or ridicule to criticize something or someone. Public figures, such as politicians, are often the subject of satire, but satirists can take aim at other targets as... (read full satire explanation with examples) Satire is the use of humor, irony, sarcasm, or ridicule to criticize something or someone. Public figures, such as politicians,... (read more)

A sestet is a six-line stanza of poetry. It can be any six-line stanza—one that is, itself, a whole poem, or one that makes up a part of a longer poem. Most commonly, the term... (read full sestet explanation with examples) A sestet is a six-line stanza of poetry. It can be any six-line stanza—one that is, itself, a whole poem,... (read more)

Setting is where and when a story or scene takes place. The where can be a real place like the city of New York, or it can be an imagined location, like Middle Earth in... (read full setting explanation with examples) Setting is where and when a story or scene takes place. The where can be a real place like the... (read more)

Sibilance is a figure of speech in which a hissing sound is created within a group of words through the repetition of "s" sounds. An example of sibilance is: "Sadly, Sam sold seven venomous serpents to Sally and... (read full sibilance explanation with examples) Sibilance is a figure of speech in which a hissing sound is created within a group of words through the repetition... (read more)

A simile is a figure of speech that directly compares two unlike things. To make the comparison, similes most often use the connecting words "like" or "as," but can also use other words that indicate... (read full simile explanation with examples) A simile is a figure of speech that directly compares two unlike things. To make the comparison, similes most often... (read more)

Traditionally, slant rhyme referred to a type of rhyme in which two words located at the end of a line of poetry themselves end in similar—but not identical—consonant sounds. For instance, the words "pact" and... (read full slant rhyme explanation with examples) Traditionally, slant rhyme referred to a type of rhyme in which two words located at the end of a line... (read more)

A soliloquy is a literary device, most often found in dramas, in which a character speaks to him or herself, relating his or her innermost thoughts and feelings as if thinking aloud. In some cases,... (read full soliloquy explanation with examples) A soliloquy is a literary device, most often found in dramas, in which a character speaks to him or herself,... (read more)

A sonnet is a type of fourteen-line poem. Traditionally, the fourteen lines of a sonnet consist of an octave (or two quatrains making up a stanza of 8 lines) and a sestet (a stanza of... (read full sonnet explanation with examples) A sonnet is a type of fourteen-line poem. Traditionally, the fourteen lines of a sonnet consist of an octave (or... (read more)

A spondee is a two-syllable metrical pattern in poetry in which both syllables are stressed. The word "downtown" is a spondee, with the stressed syllable of "down" followed by another stressed syllable, “town”: Down-town. (read full spondee explanation with examples) A spondee is a two-syllable metrical pattern in poetry in which both syllables are stressed. The word "downtown" is a... (read more)

A stanza is a group of lines form a smaller unit within a poem. A single stanza is usually set apart from other lines or stanza within a poem by a double line break or... (read full stanza explanation with examples) A stanza is a group of lines form a smaller unit within a poem. A single stanza is usually set... (read more)

A character is said to be "static" if they do not undergo any substantial internal changes as a result of the story's major plot developments. Antagonists are often static characters, but any character in a... (read full static character explanation with examples) A character is said to be "static" if they do not undergo any substantial internal changes as a result of... (read more)

Stream of consciousness is a style or technique of writing that tries to capture the natural flow of a character's extended thought process, often by incorporating sensory impressions, incomplete ideas, unusual syntax, and rough grammar. (read full stream of consciousness explanation with examples) Stream of consciousness is a style or technique of writing that tries to capture the natural flow of a character's... (read more)

A syllogism is a three-part logical argument, based on deductive reasoning, in which two premises are combined to arrive at a conclusion. So long as the premises of the syllogism are true and the syllogism... (read full syllogism explanation with examples) A syllogism is a three-part logical argument, based on deductive reasoning, in which two premises are combined to arrive at... (read more)

Symbolism is a literary device in which a writer uses one thing—usually a physical object or phenomenon—to represent something more abstract. A strong symbol usually shares a set of key characteristics with whatever it is... (read full symbolism explanation with examples) Symbolism is a literary device in which a writer uses one thing—usually a physical object or phenomenon—to represent something more... (read more)

Synecdoche is a figure of speech in which, most often, a part of something is used to refer to its whole. For example, "The captain commands one hundred sails" is a synecdoche that uses "sails"... (read full synecdoche explanation with examples) Synecdoche is a figure of speech in which, most often, a part of something is used to refer to its... (read more)

A theme is a universal idea, lesson, or message explored throughout a work of literature. One key characteristic of literary themes is their universality, which is to say that themes are ideas that not only... (read full theme explanation with examples) A theme is a universal idea, lesson, or message explored throughout a work of literature. One key characteristic of literary... (read more)

The tone of a piece of writing is its general character or attitude, which might be cheerful or depressive, sarcastic or sincere, comical or mournful, praising or critical, and so on. For instance, an editorial in a newspaper... (read full tone explanation with examples) The tone of a piece of writing is its general character or attitude, which might be cheerful or depressive, sarcastic or sincere, comical... (read more)

A tragic hero is a type of character in a tragedy, and is usually the protagonist. Tragic heroes typically have heroic traits that earn them the sympathy of the audience, but also have flaws or... (read full tragic hero explanation with examples) A tragic hero is a type of character in a tragedy, and is usually the protagonist. Tragic heroes typically have... (read more)

A trochee is a two-syllable metrical pattern in poetry in which a stressed syllable is followed by an unstressed syllable. The word "poet" is a trochee, with the stressed syllable of "po" followed by the... (read full trochee explanation with examples) A trochee is a two-syllable metrical pattern in poetry in which a stressed syllable is followed by an unstressed syllable.... (read more)

Understatement is a figure of speech in which something is expressed less strongly than would be expected, or in which something is presented as being smaller, worse, or lesser than it really is. Typically, understatement is... (read full understatement explanation with examples) Understatement is a figure of speech in which something is expressed less strongly than would be expected, or in which something... (read more)

Verbal irony occurs when the literal meaning of what someone says is different from—and often opposite to—what they actually mean. When there's a hurricane raging outside and someone remarks "what lovely weather we're having," this... (read full verbal irony explanation with examples) Verbal irony occurs when the literal meaning of what someone says is different from—and often opposite to—what they actually mean.... (read more)

A villanelle is a poem of nineteen lines, and which follows a strict form that consists of five tercets (three-line stanzas) followed by one quatrain (four-line stanza). Villanelles use a specific rhyme scheme of ABA... (read full villanelle explanation with examples) A villanelle is a poem of nineteen lines, and which follows a strict form that consists of five tercets (three-line... (read more)

A zeugma is a figure of speech in which one "governing" word or phrase modifies two distinct parts of a sentence. Often, the governing word will mean something different when applied to each part, as... (read full zeugma explanation with examples) A zeugma is a figure of speech in which one "governing" word or phrase modifies two distinct parts of a... (read more)

- PDF downloads of each of the 136 Lit Terms we cover

- PDF downloads of 1900 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 39,983 quotes across 1900 Lit Guides

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

12.14: Sample Student Literary Analysis Essays

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 40514

- Heather Ringo & Athena Kashyap

- City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

The following examples are essays where student writers focused on close-reading a literary work.

While reading these examples, ask yourself the following questions:

- What is the essay's thesis statement, and how do you know it is the thesis statement?

- What is the main idea or topic sentence of each body paragraph, and how does it relate back to the thesis statement?

- Where and how does each essay use evidence (quotes or paraphrase from the literature)?

- What are some of the literary devices or structures the essays analyze or discuss?

- How does each author structure their conclusion, and how does their conclusion differ from their introduction?

Example 1: Poetry

Victoria Morillo

Instructor Heather Ringo

3 August 2022

How Nguyen’s Structure Solidifies the Impact of Sexual Violence in “The Study”

Stripped of innocence, your body taken from you. No matter how much you try to block out the instance in which these two things occurred, memories surface and come back to haunt you. How does a person, a young boy , cope with an event that forever changes his life? Hieu Minh Nguyen deconstructs this very way in which an act of sexual violence affects a survivor. In his poem, “The Study,” the poem's speaker recounts the year in which his molestation took place, describing how his memory filters in and out. Throughout the poem, Nguyen writes in free verse, permitting a structural liberation to become the foundation for his message to shine through. While he moves the readers with this poignant narrative, Nguyen effectively conveys the resulting internal struggles of feeling alone and unseen.

The speaker recalls his experience with such painful memory through the use of specific punctuation choices. Just by looking at the poem, we see that the first period doesn’t appear until line 14. It finally comes after the speaker reveals to his readers the possible, central purpose for writing this poem: the speaker's molestation. In the first half, the poem makes use of commas, em dashes, and colons, which lends itself to the idea of the speaker stringing along all of these details to make sense of this time in his life. If reading the poem following the conventions of punctuation, a sense of urgency is present here, as well. This is exemplified by the lack of periods to finalize a thought; and instead, Nguyen uses other punctuation marks to connect them. Serving as another connector of thoughts, the two em dashes give emphasis to the role memory plays when the speaker discusses how “no one [had] a face” during that time (Nguyen 9-11). He speaks in this urgent manner until the 14th line, and when he finally gets it off his chest, the pace of the poem changes, as does the more frequent use of the period. This stream-of-consciousness-like section when juxtaposed with the latter half of the poem, causes readers to slow down and pay attention to the details. It also splits the poem in two: a section that talks of the fogginess of memory then transitions into one that remembers it all.

In tandem with the fluctuating nature of memory, the utilization of line breaks and word choice help reflect the damage the molestation has had. Within the first couple of lines of the poem, the poem demands the readers’ attention when the line breaks from “floating” to “dead” as the speaker describes his memory of Little Billy (Nguyen 1-4). This line break averts the readers’ expectation of the direction of the narrative and immediately shifts the tone of the poem. The break also speaks to the effect his trauma has ingrained in him and how “[f]or the longest time,” his only memory of that year revolves around an image of a boy’s death. In a way, the speaker sees himself in Little Billy; or perhaps, he’s representative of the tragic death of his boyhood, how the speaker felt so “dead” after enduring such a traumatic experience, even referring to himself as a “ghost” that he tries to evict from his conscience (Nguyen 24). The feeling that a part of him has died is solidified at the very end of the poem when the speaker describes himself as a nine-year-old boy who’s been “fossilized,” forever changed by this act (Nguyen 29). By choosing words associated with permanence and death, the speaker tries to recreate the atmosphere (for which he felt trapped in) in order for readers to understand the loneliness that came as a result of his trauma. With the assistance of line breaks, more attention is drawn to the speaker's words, intensifying their importance, and demanding to be felt by the readers.

Most importantly, the speaker expresses eloquently, and so heartbreakingly, about the effect sexual violence has on a person. Perhaps what seems to be the most frustrating are the people who fail to believe survivors of these types of crimes. This is evident when he describes “how angry” the tenants were when they filled the pool with cement (Nguyen 4). They seem to represent how people in the speaker's life were dismissive of his assault and who viewed his tragedy as a nuisance of some sorts. This sentiment is bookended when he says, “They say, give us details , so I give them my body. / They say, give us proof , so I give them my body,” (Nguyen 25-26). The repetition of these two lines reinforces the feeling many feel in these scenarios, as they’re often left to deal with trying to make people believe them, or to even see them.

It’s important to recognize how the structure of this poem gives the speaker space to express the pain he’s had to carry for so long. As a characteristic of free verse, the poem doesn’t follow any structured rhyme scheme or meter; which in turn, allows him to not have any constraints in telling his story the way he wants to. The speaker has the freedom to display his experience in a way that evades predictability and engenders authenticity of a story very personal to him. As readers, we abandon anticipating the next rhyme, and instead focus our attention to the other ways, like his punctuation or word choice, in which he effectively tells his story. The speaker recognizes that some part of him no longer belongs to himself, but by writing “The Study,” he shows other survivors that they’re not alone and encourages hope that eventually, they will be freed from the shackles of sexual violence.

Works Cited

Nguyen, Hieu Minh. “The Study” Poets.Org. Academy of American Poets, Coffee House Press, 2018, https://poets.org/poem/study-0 .

Example 2: Fiction

Todd Goodwin

Professor Stan Matyshak

Advanced Expository Writing

Sept. 17, 20—

Poe’s “Usher”: A Mirror of the Fall of the House of Humanity

Right from the outset of the grim story, “The Fall of the House of Usher,” Edgar Allan Poe enmeshes us in a dark, gloomy, hopeless world, alienating his characters and the reader from any sort of physical or psychological norm where such values as hope and happiness could possibly exist. He fatalistically tells the story of how a man (the narrator) comes from the outside world of hope, religion, and everyday society and tries to bring some kind of redeeming happiness to his boyhood friend, Roderick Usher, who not only has physically and psychologically wasted away but is entrapped in a dilapidated house of ever-looming terror with an emaciated and deranged twin sister. Roderick Usher embodies the wasting away of what once was vibrant and alive, and his house of “insufferable gloom” (273), which contains his morbid sister, seems to mirror or reflect this fear of death and annihilation that he most horribly endures. A close reading of the story reveals that Poe uses mirror images, or reflections, to contribute to the fatalistic theme of “Usher”: each reflection serves to intensify an already prevalent tone of hopelessness, darkness, and fatalism.

It could be argued that the house of Roderick Usher is a “house of mirrors,” whose unpleasant and grim reflections create a dark and hopeless setting. For example, the narrator first approaches “the melancholy house of Usher on a dark and soundless day,” and finds a building which causes him a “sense of insufferable gloom,” which “pervades his spirit and causes an iciness, a sinking, a sickening of the heart, an undiscerned dreariness of thought” (273). The narrator then optimistically states: “I reflected that a mere different arrangement of the scene, of the details of the picture, would be sufficient to modify, or perhaps annihilate its capacity for sorrowful impression” (274). But the narrator then sees the reflection of the house in the tarn and experiences a “shudder even more thrilling than before” (274). Thus the reader begins to realize that the narrator cannot change or stop the impending doom that will befall the house of Usher, and maybe humanity. The story cleverly plays with the word reflection : the narrator sees a physical reflection that leads him to a mental reflection about Usher’s surroundings.

The narrator’s disillusionment by such grim reflection continues in the story. For example, he describes Roderick Usher’s face as distinct with signs of old strength but lost vigor: the remains of what used to be. He describes the house as a once happy and vibrant place, which, like Roderick, lost its vitality. Also, the narrator describes Usher’s hair as growing wild on his rather obtrusive head, which directly mirrors the eerie moss and straw covering the outside of the house. The narrator continually longs to see these bleak reflections as a dream, for he states: “Shaking off from my spirit what must have been a dream, I scanned more narrowly the real aspect of the building” (276). He does not want to face the reality that Usher and his home are doomed to fall, regardless of what he does.

Although there are almost countless examples of these mirror images, two others stand out as important. First, Roderick and his sister, Madeline, are twins. The narrator aptly states just as he and Roderick are entombing Madeline that there is “a striking similitude between brother and sister” (288). Indeed, they are mirror images of each other. Madeline is fading away psychologically and physically, and Roderick is not too far behind! The reflection of “doom” that these two share helps intensify and symbolize the hopelessness of the entire situation; thus, they further develop the fatalistic theme. Second, in the climactic scene where Madeline has been mistakenly entombed alive, there is a pairing of images and sounds as the narrator tries to calm Roderick by reading him a romance story. Events in the story simultaneously unfold with events of the sister escaping her tomb. In the story, the hero breaks out of the coffin. Then, in the story, the dragon’s shriek as he is slain parallels Madeline’s shriek. Finally, the story tells of the clangor of a shield, matched by the sister’s clanging along a metal passageway. As the suspense reaches its climax, Roderick shrieks his last words to his “friend,” the narrator: “Madman! I tell you that she now stands without the door” (296).

Roderick, who slowly falls into insanity, ironically calls the narrator the “Madman.” We are left to reflect on what Poe means by this ironic twist. Poe’s bleak and dark imagery, and his use of mirror reflections, seem only to intensify the hopelessness of “Usher.” We can plausibly conclude that, indeed, the narrator is the “Madman,” for he comes from everyday society, which is a place where hope and faith exist. Poe would probably argue that such a place is opposite to the world of Usher because a world where death is inevitable could not possibly hold such positive values. Therefore, just as Roderick mirrors his sister, the reflection in the tarn mirrors the dilapidation of the house, and the story mirrors the final actions before the death of Usher. “The Fall of the House of Usher” reflects Poe’s view that humanity is hopelessly doomed.

Poe, Edgar Allan. “The Fall of the House of Usher.” 1839. Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library . 1995. Web. 1 July 2012. < http://etext.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/PoeFall.html >.

Example 3: Poetry

Amy Chisnell

Professor Laura Neary

Writing and Literature

April 17, 20—

Don’t Listen to the Egg!: A Close Reading of Lewis Carroll’s “Jabberwocky”

“You seem very clever at explaining words, Sir,” said Alice. “Would you kindly tell me the meaning of the poem called ‘Jabberwocky’?”

“Let’s hear it,” said Humpty Dumpty. “I can explain all the poems that ever were invented—and a good many that haven’t been invented just yet.” (Carroll 164)

In Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass , Humpty Dumpty confidently translates (to a not so confident Alice) the complicated language of the poem “Jabberwocky.” The words of the poem, though nonsense, aptly tell the story of the slaying of the Jabberwock. Upon finding “Jabberwocky” on a table in the looking-glass room, Alice is confused by the strange words. She is quite certain that “ somebody killed something ,” but she does not understand much more than that. When later she encounters Humpty Dumpty, she seizes the opportunity at having the knowledgeable egg interpret—or translate—the poem. Since Humpty Dumpty professes to be able to “make a word work” for him, he is quick to agree. Thus he acts like a New Critic who interprets the poem by performing a close reading of it. Through Humpty’s interpretation of the first stanza, however, we see the poem’s deeper comment concerning the practice of interpreting poetry and literature in general—that strict analytical translation destroys the beauty of a poem. In fact, Humpty Dumpty commits the “heresy of paraphrase,” for he fails to understand that meaning cannot be separated from the form or structure of the literary work.

Of the 71 words found in “Jabberwocky,” 43 have no known meaning. They are simply nonsense. Yet through this nonsensical language, the poem manages not only to tell a story but also gives the reader a sense of setting and characterization. One feels, rather than concretely knows, that the setting is dark, wooded, and frightening. The characters, such as the Jubjub bird, the Bandersnatch, and the doomed Jabberwock, also appear in the reader’s head, even though they will not be found in the local zoo. Even though most of the words are not real, the reader is able to understand what goes on because he or she is given free license to imagine what the words denote and connote. Simply, the poem’s nonsense words are the meaning.

Therefore, when Humpty interprets “Jabberwocky” for Alice, he is not doing her any favors, for he actually misreads the poem. Although the poem in its original is constructed from nonsense words, by the time Humpty is done interpreting it, it truly does not make any sense. The first stanza of the original poem is as follows:

’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogroves,

An the mome raths outgrabe. (Carroll 164)

If we replace, however, the nonsense words of “Jabberwocky” with Humpty’s translated words, the effect would be something like this:

’Twas four o’clock in the afternoon, and the lithe and slimy badger-lizard-corkscrew creatures

Did go round and round and make holes in the grass-plot round the sun-dial:

All flimsy and miserable were the shabby-looking birds

with mop feathers,

And the lost green pigs bellowed-sneezed-whistled.

By translating the poem in such a way, Humpty removes the charm or essence—and the beauty, grace, and rhythm—from the poem. The poetry is sacrificed for meaning. Humpty Dumpty commits the heresy of paraphrase. As Cleanth Brooks argues, “The structure of a poem resembles that of a ballet or musical composition. It is a pattern of resolutions and balances and harmonizations” (203). When the poem is left as nonsense, the reader can easily imagine what a “slithy tove” might be, but when Humpty tells us what it is, he takes that imaginative license away from the reader. The beauty (if that is the proper word) of “Jabberwocky” is in not knowing what the words mean, and yet understanding. By translating the poem, Humpty takes that privilege from the reader. In addition, Humpty fails to recognize that meaning cannot be separated from the structure itself: the nonsense poem reflects this literally—it means “nothing” and achieves this meaning by using “nonsense” words.

Furthermore, the nonsense words Carroll chooses to use in “Jabberwocky” have a magical effect upon the reader; the shadowy sound of the words create the atmosphere, which may be described as a trance-like mood. When Alice first reads the poem, she says it seems to fill her head “with ideas.” The strange-sounding words in the original poem do give one ideas. Why is this? Even though the reader has never heard these words before, he or she is instantly aware of the murky, mysterious mood they set. In other words, diction operates not on the denotative level (the dictionary meaning) but on the connotative level (the emotion(s) they evoke). Thus “Jabberwocky” creates a shadowy mood, and the nonsense words are instrumental in creating this mood. Carroll could not have simply used any nonsense words.

For example, let us change the “dark,” “ominous” words of the first stanza to “lighter,” more “comic” words:

’Twas mearly, and the churly pells

Did bimble and ringle in the tink;

All timpy were the brimbledimps,

And the bip plips outlink.

Shifting the sounds of the words from dark to light merely takes a shift in thought. To create a specific mood using nonsense words, one must create new words from old words that convey the desired mood. In “Jabberwocky,” Carroll mixes “slimy,” a grim idea, “lithe,” a pliable image, to get a new adjective: “slithy” (a portmanteau word). In this translation, brighter words were used to get a lighter effect. “Mearly” is a combination of “morning” and “early,” and “ringle” is a blend of “ring” and "dingle.” The point is that “Jabberwocky’s” nonsense words are created specifically to convey this shadowy or mysterious mood and are integral to the “meaning.”

Consequently, Humpty’s rendering of the poem leaves the reader with a completely different feeling than does the original poem, which provided us with a sense of ethereal mystery, of a dark and foreign land with exotic creatures and fantastic settings. The mysteriousness is destroyed by Humpty’s literal paraphrase of the creatures and the setting; by doing so, he has taken the beauty away from the poem in his attempt to understand it. He has committed the heresy of paraphrase: “If we allow ourselves to be misled by it [this heresy], we distort the relation of the poem to its ‘truth’… we split the poem between its ‘form’ and its ‘content’” (Brooks 201). Humpty Dumpty’s ultimate demise might be seen to symbolize the heretical split between form and content: as a literary creation, Humpty Dumpty is an egg, a well-wrought urn of nonsense. His fall from the wall cracks him and separates the contents from the container, and not even all the King’s men can put the scrambled egg back together again!

Through the odd characters of a little girl and a foolish egg, “Jabberwocky” suggests a bit of sage advice about reading poetry, advice that the New Critics built their theories on. The importance lies not solely within strict analytical translation or interpretation, but in the overall effect of the imagery and word choice that evokes a meaning inseparable from those literary devices. As Archibald MacLeish so aptly writes: “A poem should not mean / But be.” Sometimes it takes a little nonsense to show us the sense in something.

Brooks, Cleanth. The Well-Wrought Urn: Studies in the Structure of Poetry . 1942. San Diego: Harcourt Brace, 1956. Print.

Carroll, Lewis. Through the Looking-Glass. Alice in Wonderland . 2nd ed. Ed. Donald J. Gray. New York: Norton, 1992. Print.

MacLeish, Archibald. “Ars Poetica.” The Oxford Book of American Poetry . Ed. David Lehman. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2006. 385–86. Print.

Attribution

- Sample Essay 1 received permission from Victoria Morillo to publish, licensed Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International ( CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 )

- Sample Essays 2 and 3 adapted from Cordell, Ryan and John Pennington. "2.5: Student Sample Papers" from Creating Literary Analysis. 2012. Licensed Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported ( CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 )

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

The 27 Poetic Devices You Need to Know

Alex Simmonds

The term "poetic device" refers to anything used by a poet—including sounds, shapes, rhythms, phrases, and words—to enhance the literal meaning of their poem . This could mean using rhythm and sound to pull the reader into the world of the poem, or adding figurative meaning to their literal words.

How Many Poetic Devices Are There?

Poetic devices—form, poetic devices—diction, poetic devices—punctuation, how to identify poetic devices.

There are hundreds, possibly even thousands, of different literary devices open to poets, some of them very obscure having not been used for centuries, and so this article will divide them into categories— Poetic Form , Poetic Diction , and Poetic Punctuation —and concentrate on the most used poetic devices, with examples, in each category.

First, we’ll look at poetic devices relating to form. Poetic form refers to how the poem is structured using stanzas, line length, rhyme, and rhythm. Clever use of poetic form can enhance the meaning or emotion the poet is trying to achieve.

What Are the Basic Poetic Devices of Form?

Again, there are a huge variety of formal choices open to a poet, but for the purposes of this article we can divide them into three categories: fixed verse , blank verse and free verse .

#1: Fixed Verse

Fixed verse poems follow traditional forms, based on formal rhyme schemes and specific patterns of stanza, refrain, and meter.

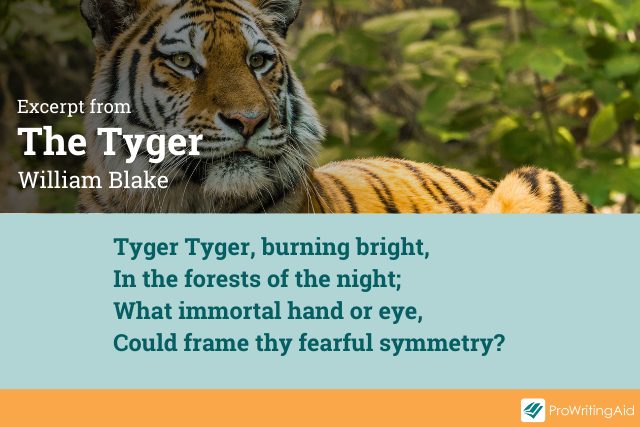

Types of fixed verse include limerick , haiku , ballad , villanelle , sestina , and rondeau . The most used, however, are odes and sonnets .

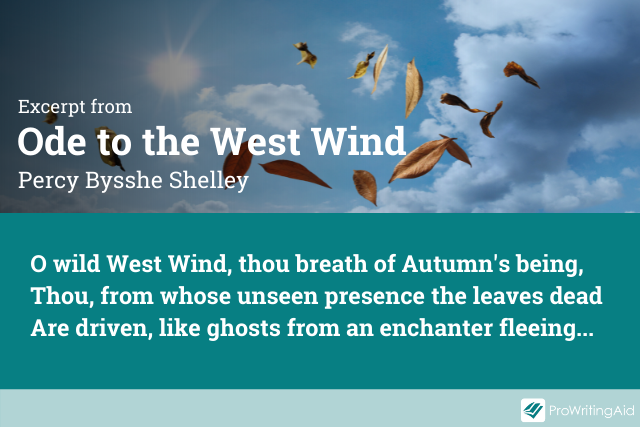

Odes are short, lyrical poems that are used to express emotions and praise. The Ode originated in ancient Greece as a way of praising an athletic victory, but later was adopted by the Romantics to convey emotion through intense or lofty language.

Odes vary in style and form but are nearly always formally structured. One of the most famous examples is Shelley’s Ode to the West Wind which is a poem written in iambic pentameter (combining an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable in groups of five.) The poem praises the quality of the wind and is a strong invocation of the poet as bringer of political change:

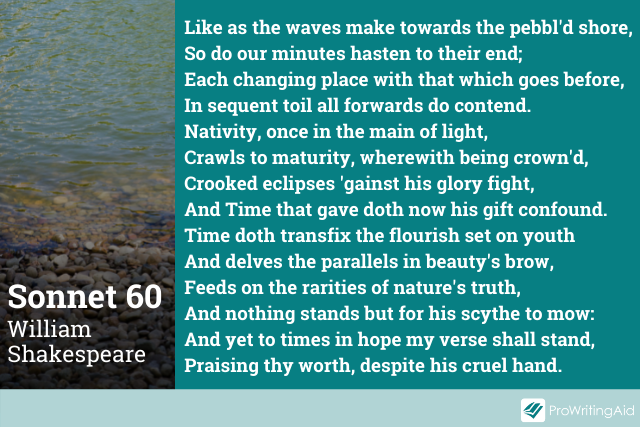

Perhaps the most famous type of fixed verse, the sonnet uses iambic pentameter in a fourteen-line poem, with a rhyme scheme of abab cdcd efef gg .

This fixed rhyme scheme can prompt unconventional phrasing, and gives the sonnet a sense of superiority over conventional speech, whilst at the same time the rhythm of the iambic pentameter keeps it feeling natural.

The sonnet has traditionally been used as a way of declaring love, most famously by Shakespeare in his 154-sonnet sequence that dramatized love, beauty, and the passing of time.

Whilst the most famous of these is Sonnet 18 ( "Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?" ) Sonnet 60, which examines the nature of passing time and its effect on human life, is worth looking at:

#2: Blank verse

Blank verse poems comprise unrhymed lines that use a regular meter—basically, a non-rhyming iambic pentameter.

Blank verse is the most influential of all English poetical forms and has regularly been used by all the great poets throughout the centuries.

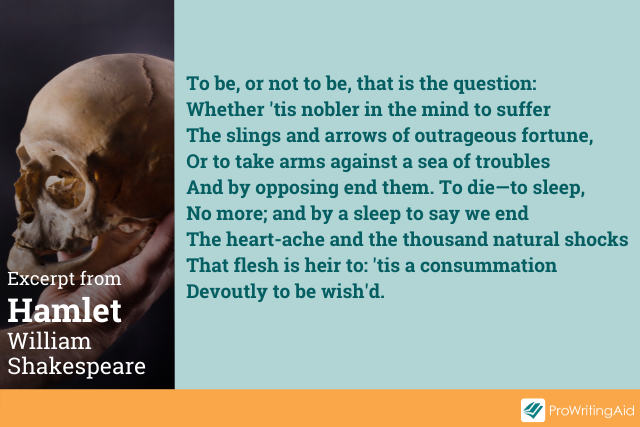

Christopher Marlowe used blank verse first, but once again it was Shakespeare who made the form his own. The most famous example in Shakespeare’s work is the "to be, or not to be" soliloquy from Hamlet (although in this speech, he doesn’t stick religiously to the ten syllables of iambic pentameter).

Notice how the rhythm accentuates the feeling of grandness as all of life and death are considered:

#3: Free Verse

Free verse poems remove the need for both formal rhyme and formal metric rhythm schemes. This allows the poem to be shaped completely by the poet. Removing this formality often allows the poet a far greater canvas on which to play.

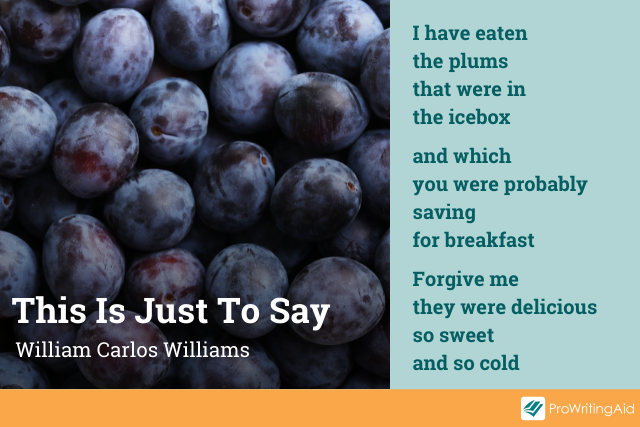

A fantastic example of free verse poetry is the short, imagist poem This Is Just to Say by William Carlos Williams.