Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Working with sources

- Synthesizing Sources | Examples & Synthesis Matrix

Synthesizing Sources | Examples & Synthesis Matrix

Published on July 4, 2022 by Eoghan Ryan . Revised on May 31, 2023.

Synthesizing sources involves combining the work of other scholars to provide new insights. It’s a way of integrating sources that helps situate your work in relation to existing research.

Synthesizing sources involves more than just summarizing . You must emphasize how each source contributes to current debates, highlighting points of (dis)agreement and putting the sources in conversation with each other.

You might synthesize sources in your literature review to give an overview of the field or throughout your research paper when you want to position your work in relation to existing research.

Table of contents

Example of synthesizing sources, how to synthesize sources, synthesis matrix, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about synthesizing sources.

Let’s take a look at an example where sources are not properly synthesized, and then see what can be done to improve it.

This paragraph provides no context for the information and does not explain the relationships between the sources described. It also doesn’t analyze the sources or consider gaps in existing research.

Research on the barriers to second language acquisition has primarily focused on age-related difficulties. Building on Lenneberg’s (1967) theory of a critical period of language acquisition, Johnson and Newport (1988) tested Lenneberg’s idea in the context of second language acquisition. Their research seemed to confirm that young learners acquire a second language more easily than older learners. Recent research has considered other potential barriers to language acquisition. Schepens, van Hout, and van der Slik (2022) have revealed that the difficulties of learning a second language at an older age are compounded by dissimilarity between a learner’s first language and the language they aim to acquire. Further research needs to be carried out to determine whether the difficulty faced by adult monoglot speakers is also faced by adults who acquired a second language during the “critical period.”

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

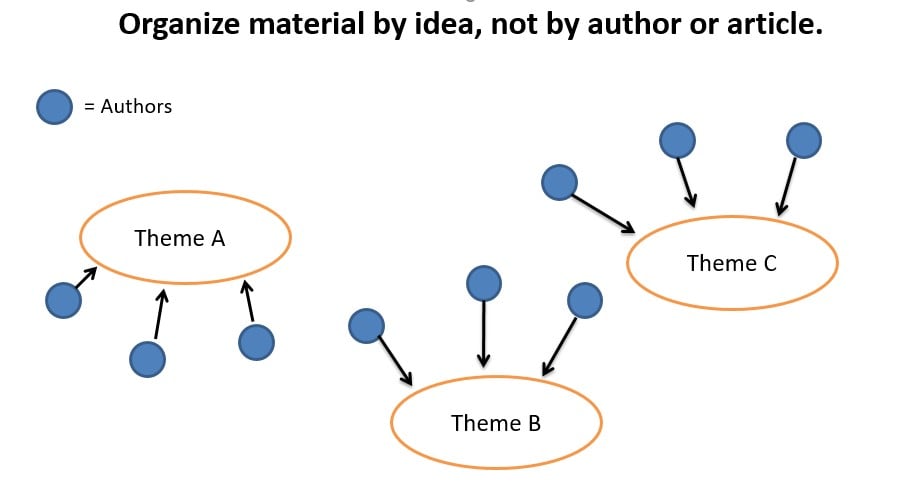

To synthesize sources, group them around a specific theme or point of contention.

As you read sources, ask:

- What questions or ideas recur? Do the sources focus on the same points, or do they look at the issue from different angles?

- How does each source relate to others? Does it confirm or challenge the findings of past research?

- Where do the sources agree or disagree?

Once you have a clear idea of how each source positions itself, put them in conversation with each other. Analyze and interpret their points of agreement and disagreement. This displays the relationships among sources and creates a sense of coherence.

Consider both implicit and explicit (dis)agreements. Whether one source specifically refutes another or just happens to come to different conclusions without specifically engaging with it, you can mention it in your synthesis either way.

Synthesize your sources using:

- Topic sentences to introduce the relationship between the sources

- Signal phrases to attribute ideas to their authors

- Transition words and phrases to link together different ideas

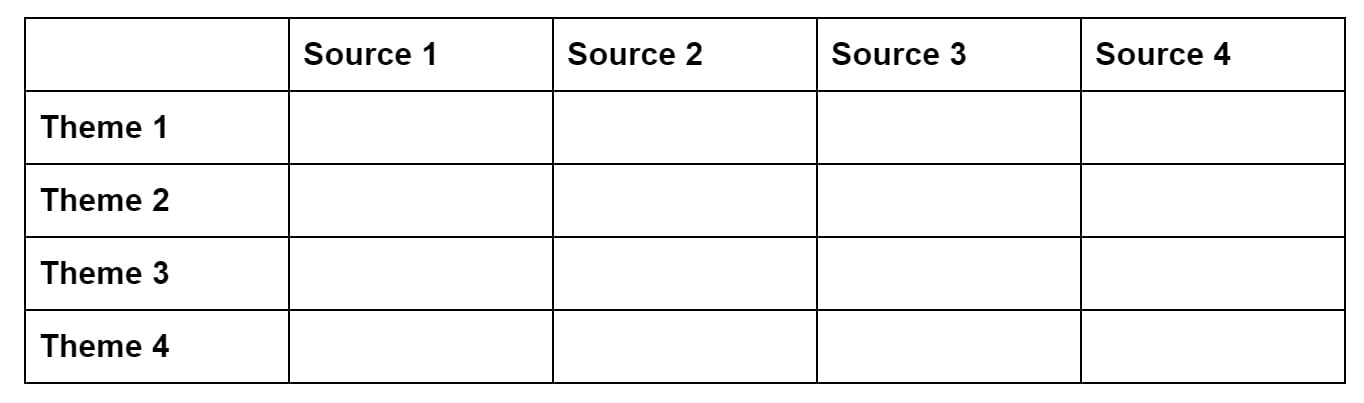

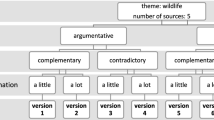

To more easily determine the similarities and dissimilarities among your sources, you can create a visual representation of their main ideas with a synthesis matrix . This is a tool that you can use when researching and writing your paper, not a part of the final text.

In a synthesis matrix, each column represents one source, and each row represents a common theme or idea among the sources. In the relevant rows, fill in a short summary of how the source treats each theme or topic.

This helps you to clearly see the commonalities or points of divergence among your sources. You can then synthesize these sources in your work by explaining their relationship.

If you want to know more about ChatGPT, AI tools , citation , and plagiarism , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- ChatGPT vs human editor

- ChatGPT citations

- Is ChatGPT trustworthy?

- Using ChatGPT for your studies

- What is ChatGPT?

- Chicago style

- Paraphrasing

Plagiarism

- Types of plagiarism

- Self-plagiarism

- Avoiding plagiarism

- Academic integrity

- Consequences of plagiarism

- Common knowledge

Scribbr Citation Checker New

The AI-powered Citation Checker helps you avoid common mistakes such as:

- Missing commas and periods

- Incorrect usage of “et al.”

- Ampersands (&) in narrative citations

- Missing reference entries

Synthesizing sources means comparing and contrasting the work of other scholars to provide new insights.

It involves analyzing and interpreting the points of agreement and disagreement among sources.

You might synthesize sources in your literature review to give an overview of the field of research or throughout your paper when you want to contribute something new to existing research.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

Topic sentences help keep your writing focused and guide the reader through your argument.

In an essay or paper , each paragraph should focus on a single idea. By stating the main idea in the topic sentence, you clarify what the paragraph is about for both yourself and your reader.

At college level, you must properly cite your sources in all essays , research papers , and other academic texts (except exams and in-class exercises).

Add a citation whenever you quote , paraphrase , or summarize information or ideas from a source. You should also give full source details in a bibliography or reference list at the end of your text.

The exact format of your citations depends on which citation style you are instructed to use. The most common styles are APA , MLA , and Chicago .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Ryan, E. (2023, May 31). Synthesizing Sources | Examples & Synthesis Matrix. Scribbr. Retrieved March 12, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/working-with-sources/synthesizing-sources/

Is this article helpful?

Eoghan Ryan

Other students also liked, signal phrases | definition, explanation & examples, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, how to find sources | scholarly articles, books, etc..

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Synthesizing Sources

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

When you look for areas where your sources agree or disagree and try to draw broader conclusions about your topic based on what your sources say, you are engaging in synthesis. Writing a research paper usually requires synthesizing the available sources in order to provide new insight or a different perspective into your particular topic (as opposed to simply restating what each individual source says about your research topic).

Note that synthesizing is not the same as summarizing.

- A summary restates the information in one or more sources without providing new insight or reaching new conclusions.

- A synthesis draws on multiple sources to reach a broader conclusion.

There are two types of syntheses: explanatory syntheses and argumentative syntheses . Explanatory syntheses seek to bring sources together to explain a perspective and the reasoning behind it. Argumentative syntheses seek to bring sources together to make an argument. Both types of synthesis involve looking for relationships between sources and drawing conclusions.

In order to successfully synthesize your sources, you might begin by grouping your sources by topic and looking for connections. For example, if you were researching the pros and cons of encouraging healthy eating in children, you would want to separate your sources to find which ones agree with each other and which ones disagree.

After you have a good idea of what your sources are saying, you want to construct your body paragraphs in a way that acknowledges different sources and highlights where you can draw new conclusions.

As you continue synthesizing, here are a few points to remember:

- Don’t force a relationship between sources if there isn’t one. Not all of your sources have to complement one another.

- Do your best to highlight the relationships between sources in very clear ways.

- Don’t ignore any outliers in your research. It’s important to take note of every perspective (even those that disagree with your broader conclusions).

Example Syntheses

Below are two examples of synthesis: one where synthesis is NOT utilized well, and one where it is.

Parents are always trying to find ways to encourage healthy eating in their children. Elena Pearl Ben-Joseph, a doctor and writer for KidsHealth , encourages parents to be role models for their children by not dieting or vocalizing concerns about their body image. The first popular diet began in 1863. William Banting named it the “Banting” diet after himself, and it consisted of eating fruits, vegetables, meat, and dry wine. Despite the fact that dieting has been around for over a hundred and fifty years, parents should not diet because it hinders children’s understanding of healthy eating.

In this sample paragraph, the paragraph begins with one idea then drastically shifts to another. Rather than comparing the sources, the author simply describes their content. This leads the paragraph to veer in an different direction at the end, and it prevents the paragraph from expressing any strong arguments or conclusions.

An example of a stronger synthesis can be found below.

Parents are always trying to find ways to encourage healthy eating in their children. Different scientists and educators have different strategies for promoting a well-rounded diet while still encouraging body positivity in children. David R. Just and Joseph Price suggest in their article “Using Incentives to Encourage Healthy Eating in Children” that children are more likely to eat fruits and vegetables if they are given a reward (855-856). Similarly, Elena Pearl Ben-Joseph, a doctor and writer for Kids Health , encourages parents to be role models for their children. She states that “parents who are always dieting or complaining about their bodies may foster these same negative feelings in their kids. Try to keep a positive approach about food” (Ben-Joseph). Martha J. Nepper and Weiwen Chai support Ben-Joseph’s suggestions in their article “Parents’ Barriers and Strategies to Promote Healthy Eating among School-age Children.” Nepper and Chai note, “Parents felt that patience, consistency, educating themselves on proper nutrition, and having more healthy foods available in the home were important strategies when developing healthy eating habits for their children.” By following some of these ideas, parents can help their children develop healthy eating habits while still maintaining body positivity.

In this example, the author puts different sources in conversation with one another. Rather than simply describing the content of the sources in order, the author uses transitions (like "similarly") and makes the relationship between the sources evident.

How to Synthesize Written Information from Multiple Sources

Shona McCombes

Content Manager

B.A., English Literature, University of Glasgow

Shona McCombes is the content manager at Scribbr, Netherlands.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, Ph.D., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years experience of working in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

When you write a literature review or essay, you have to go beyond just summarizing the articles you’ve read – you need to synthesize the literature to show how it all fits together (and how your own research fits in).

Synthesizing simply means combining. Instead of summarizing the main points of each source in turn, you put together the ideas and findings of multiple sources in order to make an overall point.

At the most basic level, this involves looking for similarities and differences between your sources. Your synthesis should show the reader where the sources overlap and where they diverge.

Unsynthesized Example

Franz (2008) studied undergraduate online students. He looked at 17 females and 18 males and found that none of them liked APA. According to Franz, the evidence suggested that all students are reluctant to learn citations style. Perez (2010) also studies undergraduate students. She looked at 42 females and 50 males and found that males were significantly more inclined to use citation software ( p < .05). Findings suggest that females might graduate sooner. Goldstein (2012) looked at British undergraduates. Among a sample of 50, all females, all confident in their abilities to cite and were eager to write their dissertations.

Synthesized Example

Studies of undergraduate students reveal conflicting conclusions regarding relationships between advanced scholarly study and citation efficacy. Although Franz (2008) found that no participants enjoyed learning citation style, Goldstein (2012) determined in a larger study that all participants watched felt comfortable citing sources, suggesting that variables among participant and control group populations must be examined more closely. Although Perez (2010) expanded on Franz’s original study with a larger, more diverse sample…

Step 1: Organize your sources

After collecting the relevant literature, you’ve got a lot of information to work through, and no clear idea of how it all fits together.

Before you can start writing, you need to organize your notes in a way that allows you to see the relationships between sources.

One way to begin synthesizing the literature is to put your notes into a table. Depending on your topic and the type of literature you’re dealing with, there are a couple of different ways you can organize this.

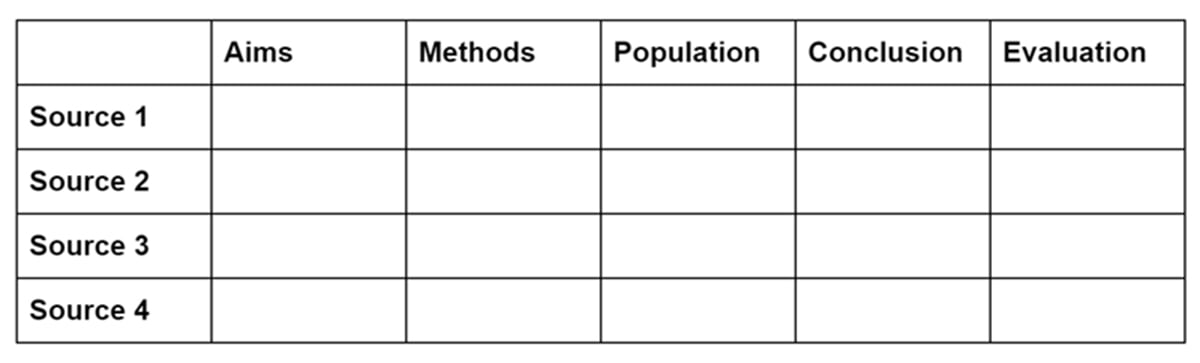

Summary table

A summary table collates the key points of each source under consistent headings. This is a good approach if your sources tend to have a similar structure – for instance, if they’re all empirical papers.

Each row in the table lists one source, and each column identifies a specific part of the source. You can decide which headings to include based on what’s most relevant to the literature you’re dealing with.

For example, you might include columns for things like aims, methods, variables, population, sample size, and conclusion.

For each study, you briefly summarize each of these aspects. You can also include columns for your own evaluation and analysis.

The summary table gives you a quick overview of the key points of each source. This allows you to group sources by relevant similarities, as well as noticing important differences or contradictions in their findings.

Synthesis matrix

A synthesis matrix is useful when your sources are more varied in their purpose and structure – for example, when you’re dealing with books and essays making various different arguments about a topic.

Each column in the table lists one source. Each row is labeled with a specific concept, topic or theme that recurs across all or most of the sources.

Then, for each source, you summarize the main points or arguments related to the theme.

The purposes of the table is to identify the common points that connect the sources, as well as identifying points where they diverge or disagree.

Step 2: Outline your structure

Now you should have a clear overview of the main connections and differences between the sources you’ve read. Next, you need to decide how you’ll group them together and the order in which you’ll discuss them.

For shorter papers, your outline can just identify the focus of each paragraph; for longer papers, you might want to divide it into sections with headings.

There are a few different approaches you can take to help you structure your synthesis.

If your sources cover a broad time period, and you found patterns in how researchers approached the topic over time, you can organize your discussion chronologically .

That doesn’t mean you just summarize each paper in chronological order; instead, you should group articles into time periods and identify what they have in common, as well as signalling important turning points or developments in the literature.

If the literature covers various different topics, you can organize it thematically .

That means that each paragraph or section focuses on a specific theme and explains how that theme is approached in the literature.

Source Used with Permission: The Chicago School

If you’re drawing on literature from various different fields or they use a wide variety of research methods, you can organize your sources methodologically .

That means grouping together studies based on the type of research they did and discussing the findings that emerged from each method.

If your topic involves a debate between different schools of thought, you can organize it theoretically .

That means comparing the different theories that have been developed and grouping together papers based on the position or perspective they take on the topic, as well as evaluating which arguments are most convincing.

Step 3: Write paragraphs with topic sentences

What sets a synthesis apart from a summary is that it combines various sources. The easiest way to think about this is that each paragraph should discuss a few different sources, and you should be able to condense the overall point of the paragraph into one sentence.

This is called a topic sentence , and it usually appears at the start of the paragraph. The topic sentence signals what the whole paragraph is about; every sentence in the paragraph should be clearly related to it.

A topic sentence can be a simple summary of the paragraph’s content:

“Early research on [x] focused heavily on [y].”

For an effective synthesis, you can use topic sentences to link back to the previous paragraph, highlighting a point of debate or critique:

“Several scholars have pointed out the flaws in this approach.” “While recent research has attempted to address the problem, many of these studies have methodological flaws that limit their validity.”

By using topic sentences, you can ensure that your paragraphs are coherent and clearly show the connections between the articles you are discussing.

As you write your paragraphs, avoid quoting directly from sources: use your own words to explain the commonalities and differences that you found in the literature.

Don’t try to cover every single point from every single source – the key to synthesizing is to extract the most important and relevant information and combine it to give your reader an overall picture of the state of knowledge on your topic.

Step 4: Revise, edit and proofread

Like any other piece of academic writing, synthesizing literature doesn’t happen all in one go – it involves redrafting, revising, editing and proofreading your work.

Checklist for Synthesis

- Do I introduce the paragraph with a clear, focused topic sentence?

- Do I discuss more than one source in the paragraph?

- Do I mention only the most relevant findings, rather than describing every part of the studies?

- Do I discuss the similarities or differences between the sources, rather than summarizing each source in turn?

- Do I put the findings or arguments of the sources in my own words?

- Is the paragraph organized around a single idea?

- Is the paragraph directly relevant to my research question or topic?

- Is there a logical transition from this paragraph to the next one?

Further Information

How to Synthesise: a Step-by-Step Approach

Help…I”ve Been Asked to Synthesize!

Learn how to Synthesise (combine information from sources)

How to write a Psychology Essay

Pasco-Hernando State College

Synthesizing Information from Sources

- Finding and Evaluating Sources (Critical Analysis)

Paraphrasing

Summarizing.

- MLA Documentation

- APA Documentation

- Writing a Research Paper

- Sample Essay with Sources - Atlantis

- Sample Essay with Sources - Bullying

Related Pages

Research papers (research essays) must include information from sources. This is called synthesizing or integrating your sources.

There are three ways to incorporate information from other sources into your paper: quoting, paraphrasing, and summarizing. Good research papers should include at least quoting and paraphrasing and preferably also summarizing. The method you choose depends on which is the best way to make the point you are trying to make in using that particular information from the source. It is very important to remember that even if you are not using the exact words of the author as when you paraphrase or summarize, you must give a source citation.

Every sentence with information from a source must give credit to the source by citing the source. It is NOT all right to have a few sentences from a source and then give credit to the source. A reader would not know how many, if any at all, of the preceding sentences had information from that source. A quote, paraphrase, or summary without a citation giving credit to the source is plagiarism.

Quotations are best used when used sparingly. A common error in many papers is the overuse of quotations. When a paper contains too many quotations the reader may become bored or conclude that you have no ideas of your own. Keep quotations short and only use them when a paraphrase would not capture the meaning or reflect the author’s specific choice of words. You may also wish to introduce a quote if you plan on disagreeing with the source since using the exact words helps the reader understand the differences between your position and the position in the source and helps to show that you are fairly representing the source.

When you do decide to use quotations, make sure that you do not simply cut the words out and drop them into your paper. You will need to give a brief introduction to the quote to let readers understand the context of the words and their relationship to your argument. Quotes that do not reflect the meaning of the author within the context are considered out-of-context . Quotes should not be used out-of-context to convey a meaning not intended by the author. In addition, quotes must be incorporated logically into a sequence of sentences.

Incorrect use:

People pay higher prices for organic food. “The FDA simply does not have enough agents to do thorough inspections” (Jones).

Corrected use:

People pay higher prices for organic food. Jones makes a good point when he explains how really impossible it is at this time to tell whether foods are grown without certain chemicals or pesticides to justify these higher prices. “The FDA simply does not have enough agents to do thorough inspections” (Jones).

Quotations must also be incorporated grammatically.

Original Quotation:

Jones continues to explain, “No proof that pesticides were not used.”

Corrected use:

Jones continues to explain that there is “no proof that pesticides were not used.”

Substitutions, Additions, and Omissions in Quotations:

Quotations can be modified; however, proper punctuation must be used to indicate the substitutions, additions, and omissions. Any such substitutions, additions or omissions should not result in quoting out of context where the meaning of the quote is changed.

- Brackets, also called square brackets, are used to show that the original quote has been modified.

- An ellipsis (three periods in a row) is used to show that words have been omitted.

Original Quotation:

“Besides, step-families offer unique advantages as well. One example is the increase in available emotional support and, other resources from the larger, more extended family. Another is the opportunity the children have for learning how to cope with an ever changing and complicated world due to the social and emotional complexity of their own step family environment” (Pinto).

Quotation Modified to Substitute an Uppercase for a Lowercase:

Pinto acknowledges that blended families can also offer positive aspects. Pinto indicates that “[o]ne example is the increase in available emotional support and, other resources from the larger, more extended family.”

See how a small letter o was substituted for the capital O since using the word that changes what is in the quote to a continuation of a sentence started outside the quote.

Quotation Modified for Clarity:

Pinto continues, “Another [advantage] is the opportunity the children have for learning how to cope with an ever changing and complicated world due to the social and emotional complexity of their own step family environment.”

The word advantage was added to make the subject clear.

Quotation Modified to Eliminate Unnecessary Words:

Pinto explains, “One example is the increase in available emotional support … from the larger, more extended family.”

See how the ellipsis shows the omission of words.

Length of Quotes:

While research essays should primarily be your own ideas and analysis of sources, sometimes, such as when the author’s words cannot be adequately paraphrased to convey the intended meaning, it is appropriate to include a long quote.

If you are quoting for more than four lines (not sentences), you need to set the quote off from the text. Indent the quote one inch from the left margin, and do not surround the quote with quotation marks. The quote should be double spaced as with the rest of the paper.

Helen Keller, though born both deaf and blind, was no coward. This can be seen in her views on the worth of life:

Security is mostly a superstition. It does not exist in nature, nor do the children of men as a whole experience it. Avoiding danger is no safer in the long run than outright exposure. Life is either a daring adventure, or nothing.

Paraphrasing is a restatement of the sources ideas into your own words. Quotations should only be used in paraphrases when there are special words or wording that cannot be paraphrased. Because the same information that the author provided is being used, a paraphrase is often as long as the original source. Since paraphrases are information from a source, every sentence with paraphrased information must cite the source even if exact words are not quoted.

Even through a sentence with paraphrased information must cite the source, any exact words from the source must be in quotation marks. Failing to use quotation marks on exact words is plagiarism even if the sentence give credit to the source.

Proper note-taking while doing research will help avoid plagiarism. Notes should include quotation marks around any exact words taken from sources.

Another problem students may have with paraphrasing is that the language used in the paraphrase should be an accurate accounting of the source’s ideas. Good paraphrasing doesn’t just capture the ideas of the source. They don’t include your own opinions or omit important information. Just like in a quotation, be sure to either introduce the source at the beginning of your paraphrase or cite the source at the end of the sentence so that the reader knows these are not your ideas, but ideas from your source.

Jones thinks the answer to reducing water usage is to raise water rates.

OR – The answer to reducing water usage is to raise water rates (Jones).

A Good Paraphrase:

has all the main ideas included with no new ideas added.

is different enough from the original to be your own writing.

- refers directly to the original source

Quotation:

“Besides, step-families offer unique advantages as well. One example is the increase in available emotional support and other resources from the larger, more extended family. Another is the opportunity the children have for learning how to cope with an ever-changing and complicated world due to the social and emotional complexity of their own step family environment” (Pinto).

Unacceptable Paraphrase:

Step-families have advantages too. One is that there is more emotional support when there are more people. Also, children can cope better with life if they start dealing with problems when they’re young.

- This paraphrase uses too much of the original’s wording and sentence structure.

- It does not properly introduce or cite the original source.

- It does not accurately convey the ideas of the source.

Improved Paraphrase:

Although there are many criticisms leveled against mixed families, Pinto gives some reasons for hope. First, Pinto says that blended families are often larger and can provide more “emotional support” and other aid for the children. Pinto continues by explaining that because of the emotional and social complications that arise in a blended family, children are more able to deal with the complexities of today’s changing world.

A summary is similar to a paraphrase in that you again use your own words. This time, however, not all the details are included. You must decide what the source’s main points are and condense them into a few concise sentences. For this reason summaries are often much shorter than the original source. Summaries should not use exact quotes from the source except in those unusual situations where there is a special word or phrase that cannot be expressed in your own words.

Like all of the other methods of incorporating source information into your paper, it is important to not plagiarize, either by forgetting to quote the original if you use the same words, or by not clearly introducing the information as having come from the source.

A Good Summary:

- contains only the most important information

- is concise; it should always be shorter than the original

- paraphrases any information taken from the source

- does not use exact wording (quotes) except for special word or words that cannot be expressed otherwise

Unacceptable Summary:

Step-families have advantages too. One is that there is more emotional support when there are more people. And there are other resources because there are more family members. Also, children can cope better with life if they start dealing with problems when they’re young.

- This summary contains more than just the most important information.

- It is not concise

- It does not refer back to the source

Improved Summary: Pinto believes that blended families can provide more emotional support and resources and help children learn to cope more effectively in a complex world.

Since a summary contains sentences with information from a source, each sentence must cite the source if you use a summary in your research paper. However, there are times when you have an assignment in a class which asks for a summary. In that case, the instructor may not require that the source be cited in each sentence as long as it is given credit at the beginning or end and there is no question it is a summary of a source. If the assignment asks for an analysis of a particular source along with your opinion, then each sentence with information from the source must cite the source in order to distinguish it from your analysis. This is not strictly a summary since summaries contain only key ideas from the source and not your opinion or analysis.

Important Notes

Separation of personal feelings:.

Sometimes, it is difficult to separate our personal feelings about the content of a source when we paraphrase or summarize. It is critical to be able to objectively paraphrase and summarize. Research is not about finding sources which support your position. Research is about finding the variety of opinions on the issue, evaluating them, and then deciding what your position is. You will be reading and using information you do not agree with.

Use of Summaries in Research Papers:

- Printer-friendly version

Literature Review How To

- Things To Consider

- Synthesizing Sources

- Video Tutorials

- Books On Literature Reviews

What is Synthesis

What is Synthesis? Synthesis writing is a form of analysis related to comparison and contrast, classification and division. On a basic level, synthesis requires the writer to pull together two or more summaries, looking for themes in each text. In synthesis, you search for the links between various materials in order to make your point. Most advanced academic writing, including literature reviews, relies heavily on synthesis. (Temple University Writing Center)

How To Synthesize Sources in a Literature Review

Literature reviews synthesize large amounts of information and present it in a coherent, organized fashion. In a literature review you will be combining material from several texts to create a new text – your literature review.

You will use common points among the sources you have gathered to help you synthesize the material. This will help ensure that your literature review is organized by subtopic, not by source. This means various authors' names can appear and reappear throughout the literature review, and each paragraph will mention several different authors.

When you shift from writing summaries of the content of a source to synthesizing content from sources, there is a number things you must keep in mind:

- Look for specific connections and or links between your sources and how those relate to your thesis or question.

- When writing and organizing your literature review be aware that your readers need to understand how and why the information from the different sources overlap.

- Organize your literature review by the themes you find within your sources or themes you have identified.

- << Previous: Things To Consider

- Next: Video Tutorials >>

- Last Updated: Nov 30, 2018 4:51 PM

- URL: https://libguides.csun.edu/literature-review

Report ADA Problems with Library Services and Resources

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

15.7: Synthesizing Sources

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 58424

- Lumen Learning

Learning Objectives

- Evaluate how good source synthesis and integration builds credibility

What is Synthesis?

Synthesis is the combining of two or more things to produce something new. When you read and write, you will be asked to synthesize by taking ideas from what you read and combining them to form new ideas.

Synthesizing Sources

Once you have analyzed the texts involved in your research and taken notes, you must turn to the task of writing your essay. The goal here is not simply to summarize your findings. Critical writing requires that you communicate your analysis, synthesis, and evaluation of those findings to your audience .

You analyze and synthesize even before you compose your first draft. In an article called, “Teaching Conventions of Academic Discourse,” Teresa Thonney outlines six standard features of academic writing. Use the list to help frame your purpose and to ensure that you are adopting the characteristics of a strong academic writer as you synthesize from various sources:

- Writers state the value of their work and announce their plan for their papers.

- Writers adopt a voice of authority.

- Writers respond to what others have said about their topic.

- Writers acknowledge that others might disagree with the position they have taken.

- Writers use academic and discipline-specific vocabulary.

- Writers emphasize evidence, often in tables, graphs, and images.

Cooking With Your Sources

Let’s return to the example of Marvin, who is working on his research assignment. Marvin already learned from the online professor that he should spend time walking with his sources (knowing where to find them) and talking to his sources (knowing who is conversing about them and what they are saying). Now Marvin will learn the importance of cooking with his sources, or creating the right recipe for an excellent paper.

O-Prof: Let’s take a look at the third metaphor: cooking. When you cook with sources, you process them in new ways. Cooking, like writing, involves a lot of decisions. For instance, you might decide to combine ingredients in a way that keeps the full flavor and character of each ingredient.

Marvin: Kind of like chili cheese fries? I can taste the flavor of the chili, the cheese, and the fries separately.

O-Prof: Yes. But other food preparation processes can change the character of the various ingredients. You probably wouldn’t enjoy gobbling down a stick of butter, two raw eggs, a cup of flour, or a cup of sugar (well, maybe the sugar!). But if you mix these ingredients and expose them to a 375-degree temperature, chemical reactions transform them into something good to eat, like a cake.

Marvin: You’re making me hungry. But what do chili cheese fries and cakes have to do with writing?

O-Prof: Sometimes, you might use direct quotes from your sources, as if you were throwing walnuts whole into a salad. The reader will definitely “taste” your original source. Other times, you might paraphrase ideas and combine them into an intricate argument. The flavor of the original source might be more subtle in the latter case, with only your source documentation indicating where your ideas came from. In some ways, the writing assignments your professors give you are like recipes. As an apprentice writing cook, you should analyze your assignments to determine what “ingredients” (sources) to use, what “cooking processes” to follow, and what the final “dish” (paper) should look like. Let’s try a few sample assignments. Here’s one:

Assignment 1: Critique (given in a human development course)

We’ve read and studied Freud’s theory of how the human psyche develops; now it’s time to evaluate the theory. Read at least two articles that critique Freud’s theory, chosen from the list I provided in class. Then, write an essay discussing the strengths and weaknesses of Freud’s theory.

Assume you’re a student in this course. Given this assignment, how would you describe the required ingredients, processes, and product?

Marvin thinks for a minute, while chewing and swallowing a mouthful of apple.

Marvin: Let’s see if I can break it down:

Ingredients

- everything we’ve read about Freud’s theory

- our class discussions about the theory

- two articles of my choice taken from the list provided by the instructor

Processes : I have to read those two articles to see their criticisms of Freud’s theory. I can also review my notes from class, since we discussed various critiques. I have to think about what aspects of Freud’s theory explain human development well, and where the theory falls short—like in class, we discussed how Freud’s theory reduces human development to sexuality alone.

Product : The final essay needs to include both strengths and weaknesses of Freud’s theory. The professor didn’t specifically say this, but it’s also clear I need to incorporate some ideas from the two articles I read—otherwise why would she have assigned those articles?

O-Prof: Good. How about this one?

Assignment 3: Research Paper (given in a health and environment course)

Write a 6–8-page paper in which you explain a health problem related to water pollution (e.g., arsenic poisoning, gastrointestinal illness, skin disease, etc.). Recommend a potential way or ways this health problem might be addressed. Be sure to cite and document the sources you use for your paper.

Ingredients : No specific guidance here, except that sources have to relate to water pollution and health. I’ve already decided I’m interested in how bottled water might help with health where there’s water pollution. I’ll have to pick a health problem and find sources about how water pollution can cause that problem. Gastrointestinal illness sounds promising. I’ll ask the reference librarian where I’d be likely to find good articles about water pollution, bottled water, and gastrointestinal illness.

Process : There’s not very specific information here about what process to use, but our conversation’s given me some ideas. I’ll use scholarly articles to find the connection between water pollution and gastrointestinal problems, and whether bottled water could prevent those problems.

Product : Obviously, my paper will explain the connection between water and gastrointestinal health. It’ll evaluate whether bottled water provides a good option in places where the water’s polluted, then give a recommendation about what people should do. The professor did say I should address any objections readers might raise—for instance, bottled water may turn out to be a good option, but it’s a lot more expensive than tap water. Finally, I’ll need to provide in-text citations and document my sources in a reference list.

O-Prof: You’re on your way. Think for a minute about these assignments. Did you notice that the “recipes” varied in their specificity?

Marvin: Yeah. The first assignment gave me very specific information about exactly what source “ingredients” to use. But in the second assignment, I had to figure it out on my own. And the processes varied, too. In the second assignment—my own assignment—I’ll have to use content from my sources to support my recommendation.

O-Prof: Different professors provide different levels of specificity in their writing assignments. If you have trouble figuring out the “recipe,” ask the professor for more information. Keep in mind that when it comes to “cooking with sources,” no one expects you to be an executive chef the first day you get to college. Over time, you’ll become more expert at writing with sources, more able to choose and use sources on your own.

Watch this video to learn more about the synthesis process.

Building Credibility through Source Integration

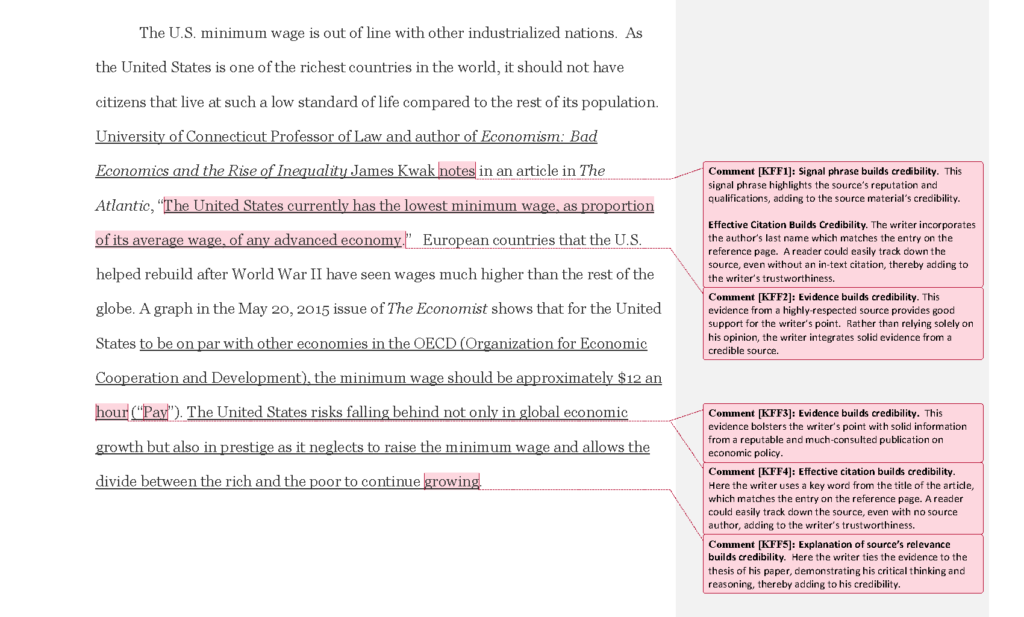

Writers are delighted when they find good sources because they know they can use those sources to make their writing stronger. Skillful integration of those sources adds to an argument’s persuasiveness but also builds the credibility of the argument and the writer.

Well-integrated sources build credibility in several ways. First, the source material adds evidence and support to your argument, making it more persuasive. Second, the signal phrase highlights the reputation and qualifications of the source, thereby adding to the source material’s credibility. Third, effective citation makes it easy for your reader to find and investigate the original source, building your credibility as a trustworthy writer. Finally, your thorough explanation of the source’s relevance to your argument demonstrates your critical thinking and reasoning , another avenue to increased credibility.

Notice in the example below how the student is able to synthesize multiple sources on the minimum wage in the United States in order to demonstrate familiarity with and respond to other voices on the topic. The writer is also able to state with authority their own perspective on the minimum wage and economic inequality based on the effective discussion and synthesis of sources.

Student Example

In the activity below, you’ll practice building your synthesis based on your analysis and thinking about other source material.

Examine the use of signal phrases, direct quotations from an outside source, citation, and explanation of relevance to consider how well the writer’s source integration builds credibility.

https://lumenlearning.h5p.com/content/1291006520432442118/embed

Synthesis, then, is the final step in the process of using sources. Good writers strive to include other voices in conversation, and they do so using direct quotes, paraphrase, and summary. The most important step, however, in integrating source material, is synthesis where we compare, contrast, and combine those other voices in order to fairly and accurately represent the existing conversation on the topic and thus to demonstrate how our ideas fit into or respond to that existing conversation.

Contributors and Attributions

- Revision and Adaptation. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Incorporating Your Sources Into Your Paper. Provided by : Boundless. Located at : www.boundless.com/writing/textbooks/boundless-writing-textbook/the-research-process-2/understanding-your-sources-265/understanding-your-sources-62-8498/. Project : Boundless Writing. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Synthesizing Sources from Chapter 4 and Integrating Sources from Chapter 5: Critical Thinking, Source Evaluations, and Analyzing Academic Writing. Authored by : Denise Snee, Kristin Houlton, Nancy Heckel. Edited by Kimberly Jacobs. Located at : lgdata.s3-website-us-east-1.amazonaws.com/docs/679/734444/Snee_2012_Research_Analysis_and_Writing.pdf. Project : Research, Analysis, and Writing. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Critical Thinking, Source Evaluations, and Analyzing Academic Writing. Authored by : Denise Snee, Kristin Houlton, Nancy Heckel. Edited by Kim Jacobs. Located at : digitalcommons.apus.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1001&context=epresscoursematerials. Project : Research, Analysis, and Writing. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- OWL at Excelsior College: Signal Phrases Activity. Provided by : Excelsior College OWL. Located at : http://owl.excelsior.edu/research-and-citations/drafting-and-integrating/drafting-and-integrating-signal-phrases-activity/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Synthesizing Activity. Provided by : Excelsior OWL. Located at : https://owl.excelsior.edu/orc/what-to-do-after-reading/synthesizing/synthesizing-activity-1/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Walk, Talk, Cook, Eat: A Guide to Using Sources. Authored by : Cynthia R. Haller. Located at : www.saylor.org/site/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/writing-spaces-readings-on-writing-vol-2.pd. Project : Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing Vol. 2.. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Synthesis: Definition & Examples. Provided by : WUWriting Center. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sLhkalJe7Zc . License : All Rights Reserved . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

The Sheridan Libraries

- Write a Literature Review

- Sheridan Libraries

- Find This link opens in a new window

- Evaluate This link opens in a new window

Get Organized

- Lit Review Prep Use this template to help you evaluate your sources, create article summaries for an annotated bibliography, and a synthesis matrix for your lit review outline.

Synthesize your Information

Synthesize: combine separate elements to form a whole.

Synthesis Matrix

A synthesis matrix helps you record the main points of each source and document how sources relate to each other.

After summarizing and evaluating your sources, arrange them in a matrix or use a citation manager to help you see how they relate to each other and apply to each of your themes or variables.

By arranging your sources by theme or variable, you can see how your sources relate to each other, and can start thinking about how you weave them together to create a narrative.

- Step-by-Step Approach

- Example Matrix from NSCU

- Matrix Template

- << Previous: Summarize

- Next: Integrate >>

- Last Updated: Sep 26, 2023 10:25 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.jhu.edu/lit-review

- Memberships

- Institutional Members

- Teacher Members

WRITING / Synthesis

Academic Synthesis

What is synthesis ?

Synthesis is a key feature of analytical academic writing. It is the skill of being able to combine a number of sources in a clause, paragraph or text to either support an argument or refute it. We also synthesise sources to be able to compare and contrast ideas and to further expand on a point. It is important that the writer shows the reader that they have researched the subject matter extensively in order to not only demonstrate how a variety of sources can agree or disagree but also to present more balanced arguments.

Academic Synthesis Video

A short 8-minute video on what synthesis is.

PDF Lesson Download

Academic Synthesis: synthesising sources

This lesson is designed to support students in their understanding and use of synthesising sources. It includes noticing the use of sources in context, a language focus with examples, two guided writing practice activities, a freer practice paragraph writing task with model answer and teacher’s notes – see worksheet example. Time: 120mins. Level *** ** [ B1/B2/C1] TEACHER MEMBERSHIP / INSTITUTIONAL MEMBERSHIP

Terms & Conditions of Use

Paragraph example of synthesis.

Look at this paragraph containing synthesised sources. Highlight the citations / in-text references and their corresponding point made.

Coursework versus examination assessment

Using assignment essays for assessment supports learning better than the traditional examination system. It is considered that course-work assignment essays can lessen the extreme stress experienced by some students over ‘sudden death’ end of semester examinations and reduce the failure rate (Langdon, 2016). Study skills research by Peters et al. (2018) support assessment by assignment because research assignments can be used to assess student learning mid-course and so provide them with helpful feedback. They also consider that assignment work lends itself to more critical approaches which help the students to learn the discourse of their subjects. In contrast, Abbot (2008) and Cane (2018) both argue that assignments are inefficient, costly to manage and are the cause of plagiarism problems in universities. A key argument is that “assessment by examination is a clean-cut approach as you obtain students’ knowledge under supervised circumstances” (Bable, 2008, p.20). The weight of evidence, however, would suggest that it is a fairer and more balanced approach to have some assessment by assignment rather than completely by examinations.

Using assignment essays for assessment supports learning better than the traditional examination system. It is considered that course-work assignment essays can lessen the extreme stress experienced by some students over ‘sudden death’ end of semester examinations and r educe the failure rate (Langdon, 2016) . Study skills research by Peters et al. (2018) support assessment by assignment because r esearch assignments can be used to assess student learning mid-course and so provide them with helpful feedback. They also consider that assignment work lends itself to more critical approaches which help the students to learn the discourse of their subjects . In contrast, Abbot (2008) and Cane (2018) both argue that assignments are inefficient, costly to manage and are the cause of plagiarism problems in universities. A key argument is that “assessment by examination is a clean-cut approach as you obtain students’ knowledge under supervised circumstances” (Bable, 2008, p.20) . The weight of evidence, however, would suggest that it is a fairer and more balanced approach to have some assessment by assignment rather than completely by examinations.

Language Focus

The writer synthesises two sources to be able to support their argument for assignment examinations.

It is considered that course-work assignment essays can lessen the extreme stress experienced by some students over ‘sudden death’ end of semester examinations and reduce the failure rate (Langdon, 2016) . Study skills research by Peters et al. (2018) support assessment by assignment because research assignments can be used to assess student learning mid-course and so provide them with helpful feedback.

The writer synthesises two connected sources to be show the opposing views to assignment based examinations.

In contrast, Abbot (2008) and Cane (2018) both argue that assignments are inefficient, costly to manage and are the cause of plagiarism problems in universities.

The writer synthesises another relevant source through quotation to further support the point against assignment-based examinations.

A key argument is that “assessment by examination is a clean-cut approach as you obtain students’ knowledge under supervised circumstances” (Bable, 2008, p.20) .

The writer could synthesise a number of sources together to show they have applied comprehensive academic research into the topic.

Study skills research by Jones et al. (2010), UCL (2016), Wilson (2017) and Peters (2018) support assessment by assignment because research assignments can be used to assess student learning mid-course and so provide them with helpful feedback.

Study skills research supports assessment by assignment because research assignments can be used to assess student learning mid-course and so provide them with helpful feedback (Jones et al., 2010; UCL, 2016; Wilson, 2017 & Peters, 2018) .

Integral and non-integral referencing

When synthesising sources, it is important to incorporate and reference them accurately. This can be done in two ways:

- Integral citations are where the author is the main subject of clause and only the year is placed in brackets. A reporting verb ( argue, claim, suggest etc.) is required to introduce the rest of the clause.

2. In non-integral citations, both the author and year is stated in parenthesis at the end of a clause. There must also be a comma separating the name and year.

Synthesis Practice

Suggested answer

Although the main goal of the World Bank is to reduce poverty and foster economic growth in developing countries (Johnson, 2018) , Williams (2019) highlights that there has been an increase in the level of poverty in Africa.

For a detailed worksheet and more exercises – buy the download below.

Arnold (2019) asserts that the decline of printed newspapers is mainly due to increased online activity overall. As we spend more time on the Internet in general than we did ten years previously, the more likely we are to search for news stories through search engines or blogs (James, 2020).

Academic Synthesis Download

Academic Synthesis: synthesising sources

Memberships (Teacher / Institutional)

Full access to everything - £80 / £200 / £550

Join today * x

More downloads

- Harvard Referencing Guide

- APA 7th Edition Referencing Guide

Referencing Guide: Harvard

This is a basic reference guide to citing and creating a reference list or a bibliography. It shows the correct way to create in-text citations and reference lists for books, journals, online newspapers and websites. Web page link . TEACHER MEMBERSHIP / INSTITUTIONAL MEMBERSHIP

Free Download

Referencing Guide: APA 7th Edition

Referencing: harvard referencing worksheet 1 .

Two part worksheet that is a paragraph and reference list. Students have to put in the correct in-text reference. The second part is a reference list exercise where students have to put the sections in the correct order. A nice lesson to introduce students to referencing and becoming aware of key referencing principles. Level ** ** * [B1/B2/C1] Example / Webpage link / TEACHER MEMBERSHIP / INSTITUTIONAL MEMBERSHIP

£4.00 – Add to cart Checkout Added to cart

Referencing: Harvard Referencing Worksheet 2

This lesson supports students in their understanding and use of Harvard referencing. It contains six worksheets: a discussion on referencing, a noticing activity, a reordering task, an error identification exercise, a sentence completion task, a gap-fill activity and a reference list task. Level ** ** * [B1/B2/C1] Example / Webpage link / TEACHER MEMBERSHIP / INSTITUTIONAL MEMBERSHIP

£5.00 – Add to cart Checkout Added to cart

Two part worksheet that is a paragraph and reference list. Students have to put in the correct in-text reference. The second part is a reference list exercise where students have to put the sections in the correct order. A nice lesson to introduce students to referencing and becoming aware of key referencing principles. Level ** ** * [B1/B2/C1] Example / Webpage link / TEACHER MEMBERSHIP / INSTITUTIONAL MEMBERSHIP

This lesson supports students in their understanding and use of APA referencing. It contains six worksheets: a discussion on referencing, a noticing activity, a reordering task, an error identification exercise, a sentence completion task, a gap-fill activity and a reference list task. Level ** ** * [B1/B2/C1] Example / Webpage link / TEACHER MEMBERSHIP / INSTITUTIONAL MEMBERSHIP

How to use www.citethisforme.com

This lesson is an introduction to using the online reference generator: www.citethisforme.com. It begins by providing a step-by-step guide to using the application and its many functions. The lesson is a task-based activity where students use the reference generator to create bibliography citations. Worksheet example Time: 60mins. Level *** ** [ B1/B2/C1] / Video / TEACHER MEMBERSHIP / INSTITUTIONAL MEMBERSHIP

Paraphrasing Lesson – how to paraphrase effectively

It starts by discussing the differences between quotation, paraphrase and summary. It takes students through the basics of identifying keywords, finding synonyms and then changing the grammatical structure. There is plenty of practice, all with efficient teacher’s notes. Level ** ** * [B1/B2/C1] Example / TEACHER MEMBERSHIP / INSTITUTIONAL MEMBERSHIP

Paraphrasing Lesson 2 – improve your paraphrasing skills

This lesson helps students to improve their paraphrasing skills. The guided learning approach includes a text analysis activity where students identify the paraphrasing strategies, five sentence-level tasks to practise the strategies and two paragraph-level exercises to build on the previous tasks.. Level ** ** * [B1/B2/C1] Example / TEACHER MEMBERSHIP / INSTITUTIONAL MEMBERSHIP

Writing a paragraph – using quotes about smoking

Students are given a worksheet with nine quotes taken from The New Scientist, BBC News, The Economist, etc… and choose only three. They use these three quotes to write a paragraph trying to paraphrase the quotes and produce a cohesion piece of writing. Level ** ** * [B1/B2/C1] Example / TEACHER MEMBERSHIP / INSTITUTIONAL MEMBERSHIP

Reporting Verbs

Use the verbs in the box to put into the sentences on the worksheet. Each sentence has a description of the type of verb needed. Check the grammar of the verb too! Web page link . TEACHER MEMBERSHIP / INSTITUTIONAL MEMBERSHIP

More Writing Resources

Academic phrases, academic style [1], academic style [2], academic style [3], academic style [4], academic word list , writing websites, error correction, hedging [1], hedging [2], nominalisation, noun phrases [1], noun phrases [2], the syllabus, referencing, in-text referencing, harvard ref. [1], harvard ref. [2], apa ref [1], apa ref [2], ref. generators, reference lists, reporting verbs, credible sources, evaluating sources, academic integrity, 'me' in writing, writer's voice , writing skills, paraphrasing [1], paraphrasing [2], paraphrase (quotes), summary writing , summary language, critical thinking, analysis & evaluation, fact vs opinion, argument essays, spse essays, sentence str. [1], sentence str. [2], sentence str. [3], punctuation, academic posters new, structure , essay structure, introductions, thesis statements, paragraphing, topic sentences [1], topic sentences [2], definitions, exemplification , conclusions, linking words, parallelism, marking criteria, more digital resources and lessons.

online resources

Medical English

New for 2024

DropBox Files

Members only

Instant Lessons

OneDrive Files

Topic-lessons

Feedback Forms

6-Week Course

SPSE Essays

Free Resources

Charts and graphs

AEUK The Blog

12-Week Course

Advertisement:.

OASIS: Writing Center

Video transcripts, analyzing & synthesizing sources: synthesis: definition and examples.

Last updated 11/8/2016

Video Length: 2:50

Visual: The screen shows the Walden University Writing Center logo along with a pencil and notebook. “Walden University Writing Center.” “Your writing, grammar, and APA experts” appears in center of screen. The background changes to the title of the video with open books in the background.

Audio: Guitar music plays.

Visual: Slide changes to the title “Moving Towards Synthesis” and the following:

Interpreting, commenting on, explaining, discussion of, or making connections between MULTIPLE ideas and sources for the reader.

Often answers questions such as:

- What do these things mean when put together?

- How do you as the author interpret what you’ve presented?

Audio : Synthesis is a lot like, I like to say it's like analysis on steroids. It's a lot like analysis, where analysis is you're commenting or interpreting one piece of evidence or one idea, one paraphrase or one quote. Synthesis is where you take multiple pieces of evidence or multiple sources and their ideas and you talk about the connections between those ideas or those sources. And you talk about where they intersect or where they have commonalities or where they differ. And that's what synthesis is. But really, in synthesis, when we have synthesis, it really means we're working with multiple pieces of evidence and analyzing them.

Visual: Slide changes to the title “Examples of Synthesis” and the following example:

Ang (2016) found that small businesses that followed the theory of financial management reduced business costs by 12%, while Sonfield (2015) found that this theory reduced costs by 17%. These studies together confirmed that adopting the theory of financial management reduces costs for U.S. small businesses.

Audio: So here's an example for you. In this eaxmple we have Ang (2016), that's source number 1, right? Then Sonfield (2015), that's source number 2. They are both using this theory and found that it reduced costs by both 12% and 17%. So this is my evidence, right?

I have one sentence, but two pieces of evidence, because we're working with two different sources, Ang and Sonfield, one and two. In my next sentence, my last sentence here, we have my piece of synthesis. Because I'm taking these two sources and saying that they both found something very similar. They confirmed that adopting the theory for financial management reduces costs for small businesses. So I'm showing the commonality between these two sources. So it's a very, sort of, not simple, but, you know, clean approach to synthesis. It's a very direct approach to kind of showing the similarities between these two sources. So that's an example of synthesis, okay.

Visual : The following example is added to the slide:

Sharpe (2016) observed an increase in students’ ability to focus after they had recess. Similarly, Barnes (2015) found that hands-on activities also helped students focus. Both of these techniques have worked well in my classroom, helping me to keep my students engaged in learning.

Audio: Another example here. So Sharpe found that one thing helps students. Barnes found another thing helps students focus. Two different sources, two different ideas. In the bold sentence of synthesis, I'm taking these two ideas together and talking about how they have both worked well in my classroom.

The synthesis that we have here kind of take two different approaches. The first example is more about how these studies confirm something. The second example is about how these two ideas can be useful in my own practice, I'm applying it to my own practice, or the author is applying it to their own practice in the classroom. But they both are examples of synthesis and taking different pieces of evidence showing how they work together or relate, okay.

I kind of like to think of synthesis as taking two pieces of a puzzle. So each piece of evidence is a piece of the puzzle. And you're putting together those pieces for the reader and saying, look, this is the overall picture, right? This is what we can see, when these two pieces--or three pieces--of the puzzle are put together. So it's kind of like putting together a puzzle.

Visual: “Walden University Writing Center. Questions? E-mail [email protected] ” appears in center of screen.

- Previous Page: Analyzing & Synthesizing Sources: Analysis in Paragraphs

- Next Page: Analyzing & Synthesizing Sources: Synthesis in Paragraphs

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Summarizing and synthesizing

Part 3: Chapter 10

Questions to consider

A. What distinguishes a synthesis from a summary?

B. How much “author voice” is present relative to source material?

C. What is the nature of the material contributed to a synthesis by the author?

The purpose of synthesizing

Combining separate elements into a whole is the basic dictionary definition of synthesis. It is a way to make connections between numerous and varied source materials. A literature review presents a synthesis of material, grouped by topic, to create a broad and comprehensive view of the literature relevant to a research question. Here, the research questions are often modified to the realities of the information, or information may be selected or rejected based on relevance. This organizational approach helps in understanding the information and structuring the review.

Because research is an iterative process, it is not unusual to go back and search information sources for more material while remaining within the parameters of the topic and research questions. It can be difficult to cope with “everything” on a topic; the need to carefully select based on relevancy is ongoing.

The synthesis must demonstrate a critical analysis of the papers assembled as well as an integration of the analytical results. All included sources must be directly relevant and the synthesis writer should make a significant contribution. As part of an introduction or literature review, the syntheses not only illustrate the evolution of research on an issue, but the writer’s own commentary on what this information means .

Many writers begin the synthesis process by creating a grid, table, or an outline organizing summaries of the source material to discover or extend common themes with the collection. The summary grid or outline provides a researcher an overview to compare, contrast and otherwise investigate the relationships and potential deficiencies. [1]

Language in Action

- How many different sources are used in the synthesis (excerpted from “Does international work experience pay off? The relationship between international work experience, employability and career success: A 30-country, multi-industry study” ) that follows? (IWE: international work experience)

- How do the sources contribute to the message of the paragraph?

- What are the elements of a strong synthesis?

- What information is contributed by the authors themselves?

1 Taking stock of the literature, several characteristics stand out that limit our understanding of the IWE−career success relationship. 2 First, many studies focus on individuals soon after their return from an IWE or while they are still expatriates (Kraimer et al., 2016). 3 These findings may therefore report results pertaining to a short-lived career phase. 4 Given that careers develop over time, and success, especially in the form of promotions and salary increases, may take some time to materialise, it is perhaps not surprising that findings have been mixed. 5 Some authors note that there are short-term, career-related costs of IWE and the career ‘payoff’ occurs after a time lag for which cross-sectional studies may not account (Benson & Pattie, 2008; Biemann & Braakmann, 2013). 6 Second, the majority of studies use samples consisting only of individuals with IWE (Jokinen et al., 2008; Stahl et al., 2009; Suutari et al., 2018). 7 Large samples that include both individuals with and without IWE are needed to provide the variance needed to identify the influence of IWE on career success (e.g., Andresen & Biemann, 2013). 8 Third, studies tend to focus on the baseline question of whether IWE or IWE-specific characteristics (e.g., host country, developmental nature of assignment) are related to a particular career success variable (e.g., Bücker et al., 2016; Jokinen et al., 2008; Stahl et al., 2009). 9 Yet there may be an indirect relationship between IWE and career success (Zhu et al., 2016). 10 More complex models that examine the possible impact of mediating variables are thus needed (Mayrhofer et al., 2012). 11 Lastly, while studies acknowledge that findings from specific countries/nationalities, industries, organisations or occupational roles may not be transferable to all individuals with IWE (Biemann & Braakmann, 2013; Schmid & Wurster, 2017; Suutari et al., 2018), the specific role of national context is rarely considered. 12 However, careers do not develop in a vacuum. 13 Contextual factors play an important role in moderating the career impact of various career experiences such as IWE (Shen et al., 2015). [2]

Organizing the material

Beginning the synthesis process by creating a grid, table, or an outline for summaries of sources offers an overview of the material along with findings and common themes. The summary, grid, or outline will allow quick comparison of the material and reveal gaps in information. [3]

The process of building a “library” from which to draw information is critical in developing the defense, argument or justification of a research study. While field and laboratory research is often engaging and interesting, understanding the backstory and presenting it as an explanation of a proposed method or approach is essential in obtaining funding and/or the necessary committee approval.

Returning to the foundational skill of producing a summary , and combining that with the maintenance of a system to manage source material and details, an annotated bibliography can be both an intellectual structure that reveals connections among sources and a means to initiating – on a manageable level – the arduous writing.

Example – Two entries from an annotated bibliography

Nafisi, A. (2003). Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Memoir in Books. New York: Random House.

A brave teacher in Iran met with seven of her most committed female students to discuss forbidden Western classics over the course of a couple of years, while Islamic morality squads staged raids, universities fell under the control of fundamentalists, and artistic expression was suppressed. This powerful memoir weaves the stories of these women with those of the characters of Jane Austen, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Henry James, and Vladimir Nabokov and extols the liberating power of literature.

Obama, B. (2007). Dreams from My Father. New York: Random House.

This autobiography extends from a childhood in numerous locations with a variety of caregivers (a single parent, grandparents, boarding school) to an exploration of individual heritage and family in Africa, revealing a broken/blended family, abandonment and reconnection, and unresolved endings. Obama describes his existence on the margins of society, the racial tension within his biracial family, and his own identity conflict and turmoil.

Using a chart or grid

Below is a model of a basic table for organizing source material.

Exercise #1

- Read the excerpts from three sources below. Determine the common topic and themes.

- Complete a table like the one above using information from these three sources.

1 Completion of a dissertation is an intense activity. 2 For both groups [completers and non-], the advisor and the student’s family and spouse served as the major source of emotional support and are most heavily invested in the dissertation. 3 Other students and the balance of the dissertation committee were rated as providing little support. 4 Since work on the dissertation is highly individual and there are no College organized groups of students working on the dissertation that meet regularly, the process can be a lonely one. 5 Great independence and a strong sense of direction is required. 6 Although many students rated themselves as having little experience with research, students are dependent on their own resources and on those closest to them. 7 It was noted that graduates rated emotional support from all sources more highly than students rated it. 8 This may be a significant factor associated with dissertation completion.

9 The scales and checklists suggest that there are identifiable differences between the two groups. 10 Since the differences are not great, the implications are that with some modification of procedures, a greater proportion of students can become graduates. 11 Emotional support, financial support, experience with research, familiarity with university and college dissertation requirements, and ready access to university resources and advisors may be factors to build into a modified system to achieve a greater proportion of graduates.

Kluever, R., Green, K. E., Lenz, K., Miller, M. M., & Katz, E. (1995). Graduates and ABDs in colleges of education: Characteristics and implications for the structure of doctoral programs. In Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association. San Francisco, CA. Retrieved from the ERIC database .

1 In this writing group, students evaluated their goal achievement, reflected on the obstacles before them, and set new targets. 2 This process encouraged them to achieve their goals, and they could modify or start a new target instead of giving up. 3 The students also received positive feedback and support from other members of the group. 4 This positive environment helped the students view failure as part of the nature of writing a thesis.

5 On the other hand, daily monitoring encouraged the students to focus more on the process and less on the outcome; therefore, they experienced daily success instead of feeling a failure when the goals were not achievable.

Patria, B., & Laili, L. (2021). Writing group program reduces academic procrastination: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Psychology , 9 (1), 1–157. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00665-9

1 The promotion of awareness of the tension between core qualities and ideals, and inner obstacles, in particular limiting thoughts, in combination with guidelines for overcoming the tension by being aware of one’s ideals and character strengths is characteristic of the core reflection approach and appears to have a strong potential for diminishing academic procrastination behavior. 2 These results make clear that a positive psychological approach focusing on strengths can be beneficial for diminishing students’ academic procrastination. 3 In particular, supporting and regenerating character strengths can be an effective approach for overcoming academic procrastination.