- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Student Opinion

Should We Get Rid of Homework?

Some educators are pushing to get rid of homework. Would that be a good thing?

By Jeremy Engle and Michael Gonchar

Do you like doing homework? Do you think it has benefited you educationally?

Has homework ever helped you practice a difficult skill — in math, for example — until you mastered it? Has it helped you learn new concepts in history or science? Has it helped to teach you life skills, such as independence and responsibility? Or, have you had a more negative experience with homework? Does it stress you out, numb your brain from busywork or actually make you fall behind in your classes?

Should we get rid of homework?

In “ The Movement to End Homework Is Wrong, ” published in July, the Times Opinion writer Jay Caspian Kang argues that homework may be imperfect, but it still serves an important purpose in school. The essay begins:

Do students really need to do their homework? As a parent and a former teacher, I have been pondering this question for quite a long time. The teacher side of me can acknowledge that there were assignments I gave out to my students that probably had little to no academic value. But I also imagine that some of my students never would have done their basic reading if they hadn’t been trained to complete expected assignments, which would have made the task of teaching an English class nearly impossible. As a parent, I would rather my daughter not get stuck doing the sort of pointless homework I would occasionally assign, but I also think there’s a lot of value in saying, “Hey, a lot of work you’re going to end up doing in your life is pointless, so why not just get used to it?” I certainly am not the only person wondering about the value of homework. Recently, the sociologist Jessica McCrory Calarco and the mathematics education scholars Ilana Horn and Grace Chen published a paper, “ You Need to Be More Responsible: The Myth of Meritocracy and Teachers’ Accounts of Homework Inequalities .” They argued that while there’s some evidence that homework might help students learn, it also exacerbates inequalities and reinforces what they call the “meritocratic” narrative that says kids who do well in school do so because of “individual competence, effort and responsibility.” The authors believe this meritocratic narrative is a myth and that homework — math homework in particular — further entrenches the myth in the minds of teachers and their students. Calarco, Horn and Chen write, “Research has highlighted inequalities in students’ homework production and linked those inequalities to differences in students’ home lives and in the support students’ families can provide.”

Mr. Kang argues:

But there’s a defense of homework that doesn’t really have much to do with class mobility, equality or any sense of reinforcing the notion of meritocracy. It’s one that became quite clear to me when I was a teacher: Kids need to learn how to practice things. Homework, in many cases, is the only ritualized thing they have to do every day. Even if we could perfectly equalize opportunity in school and empower all students not to be encumbered by the weight of their socioeconomic status or ethnicity, I’m not sure what good it would do if the kids didn’t know how to do something relentlessly, over and over again, until they perfected it. Most teachers know that type of progress is very difficult to achieve inside the classroom, regardless of a student’s background, which is why, I imagine, Calarco, Horn and Chen found that most teachers weren’t thinking in a structural inequalities frame. Holistic ideas of education, in which learning is emphasized and students can explore concepts and ideas, are largely for the types of kids who don’t need to worry about class mobility. A defense of rote practice through homework might seem revanchist at this moment, but if we truly believe that schools should teach children lessons that fall outside the meritocracy, I can’t think of one that matters more than the simple satisfaction of mastering something that you were once bad at. That takes homework and the acknowledgment that sometimes a student can get a question wrong and, with proper instruction, eventually get it right.

Students, read the entire article, then tell us:

Should we get rid of homework? Why, or why not?

Is homework an outdated, ineffective or counterproductive tool for learning? Do you agree with the authors of the paper that homework is harmful and worsens inequalities that exist between students’ home circumstances?

Or do you agree with Mr. Kang that homework still has real educational value?

When you get home after school, how much homework will you do? Do you think the amount is appropriate, too much or too little? Is homework, including the projects and writing assignments you do at home, an important part of your learning experience? Or, in your opinion, is it not a good use of time? Explain.

In these letters to the editor , one reader makes a distinction between elementary school and high school:

Homework’s value is unclear for younger students. But by high school and college, homework is absolutely essential for any student who wishes to excel. There simply isn’t time to digest Dostoyevsky if you only ever read him in class.

What do you think? How much does grade level matter when discussing the value of homework?

Is there a way to make homework more effective?

If you were a teacher, would you assign homework? What kind of assignments would you give and why?

Want more writing prompts? You can find all of our questions in our Student Opinion column . Teachers, check out this guide to learn how you can incorporate them into your classroom.

Students 13 and older in the United States and Britain, and 16 and older elsewhere, are invited to comment. All comments are moderated by the Learning Network staff, but please keep in mind that once your comment is accepted, it will be made public.

Jeremy Engle joined The Learning Network as a staff editor in 2018 after spending more than 20 years as a classroom humanities and documentary-making teacher, professional developer and curriculum designer working with students and teachers across the country. More about Jeremy Engle

The Cord News

The Case Against Homework

Hades2k, https://www.flickr.com/photos/hades2k/7437152606

According to Stanford research, “56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress.”

Daniel Hampton , Staff Writer March 4, 2022

Homework has been systematically ruining students’ home lives for decades.

Homework is a concept that seems fine on paper; however, in practice, it works to limit the creativity of students and slow their lives down. Students who work jobs or have families to take care of tend to have too much homework that affects other parts of their lives , especially if the volume of homework is quite high. Students already spend 5-8 hours every day in school — adding homework on top of jobs or other outside activities is too much for your average student.

Fundamentally, school is really a full-time job for students. With another job, you’re almost working two full-time jobs or a full-time job and a part-time job at the same time. Imagine working 12 hours almost every day and having extra work on top of that.

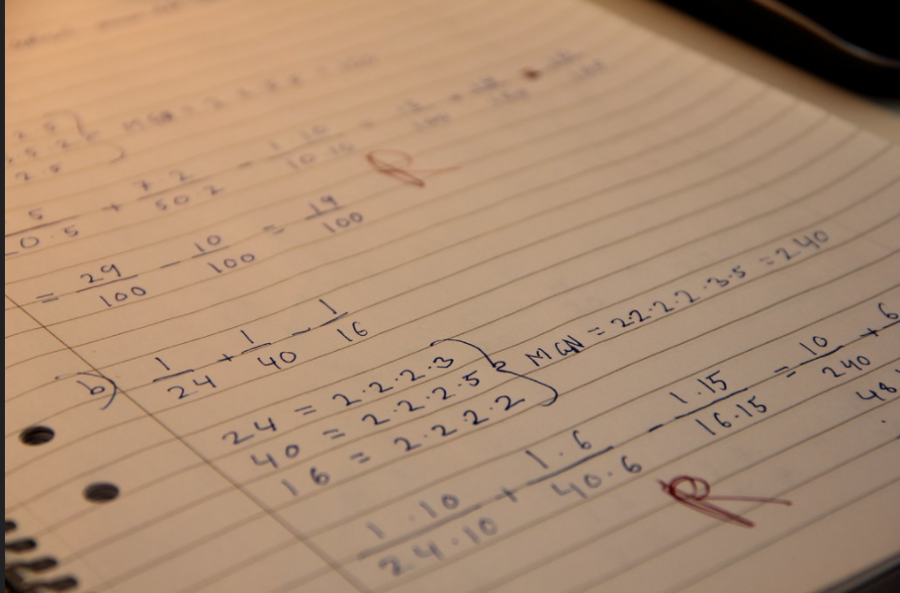

Students who have long work-weeks, along with homework, will get overwhelmed extremely quickly, decreasing their performance in school and at work. For instance, with math homework (which can be particularly confusing), students can spend hours trying to do it, only to end up making no further progress. I, myself, have spent hours doing homework, and it is definitely time-consuming when I’m lost.

While homework overwhelms students, it also limits freedom to explore creative arts. Students who have passions such as video creation, singing, or video games have less time to do creative arts because of homework. These same students might already have limited free time, and adding homework on top of this does not help at all. Students’ hidden passions are often taken away or restrained just because they’re being forced to “practice outside of class,” when there are other parts of life they need to focus on too.

Students can be burned out from homework, and it can affect their performance in school. By that I mean students who spend great amounts of time doing homework often stay up late at night, reducing the amount of sleep they get, and hurting themselves. Homework burns students out, tires them, and reduces their grades the next day due to the inability to finish assignments. Due to the inconsistent length of assignments, it can be quite difficult to plan around homework.

Homework objectively does not improve school performance. A study by Adam Maltese and reported on by The Huffington Post (the IU School of Education assistant professor) found that “There was no relationship whatsoever between time spent on homework and course grade.”

Stanford research also found that “ 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress.” This Stanford research paper went on to say, “S tudents said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems.”

A common argument for homework is that it reduces screen time. This can be refuted, however, because although it might reduce screen time, it also leads to a more sedentary lifestyle. Not to mention, most homework assignments are done on school-provided Chromebooks.

Another argument for homework is that it is self-paced learning time, but this argument can be refuted by pointing out that in-class time can also provide self-paced learning. Teachers can provide time for studying or self-paced learning in class.

Note that I am not calling for a universal ban on homework, just a restriction of the amount of homework that we receive. Each day, students should only be provided 1-2 homework assignments per class. Although this may not sound like a lot, in reality, that is actually plenty of outside-of-class practice.

Homework is an example of an old idea that no longer functions as it used to, and in this day and age, it needs to be fixed.

Daniel is a sophomore and a first-year writer for The Cord News.

- Polls Archive

- Dakota Ridge High School 16 Mullen 9 Apr 19 / Men's Varsity Lacrosse

- Dakota Ridge High School 10 Evergreen 6 Apr 17 / Men's Varsity Lacrosse

- Dakota Ridge High School 2 Valor Christian 21 Apr 16 / Women's Varsity Lacrosse

- Dakota Ridge High School 7 Horizon 13 Apr 15 / Women's Varsity Lacrosse

- Dakota Ridge High School 11 Air Academy 10 Apr 12 / Men's Varsity Lacrosse

Animals Deserve Our All

Parents Should be Held Responsible for the Actions of Their Children

It’s Time for Gender Neutral Restrooms in Colorado

My Parents Don’t Let Me Use Social Media, and I’m Okay With That

Summer and Spring Are Just Better Than Winter and Fall

We Destroyed Our Planet, Now It’s Time to Fix It

Why is 18 the Age of Adulthood?

America Must Step Forward by Implementing a Maximum Age for Presidents

Reflecting … and Goodbye

The IB Diploma Program: A Review

The Student News Site of Dakota Ridge High School

Comments (0)

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request More Info

Fill out the form below and a member of our team will reach out right away!

" * " indicates required fields

Is Homework Necessary? Education Inequity and Its Impact on Students

The Problem with Homework: It Highlights Inequalities

How much homework is too much homework, when does homework actually help, negative effects of homework for students, how teachers can help.

Schools are getting rid of homework from Essex, Mass., to Los Angeles, Calif. Although the no-homework trend may sound alarming, especially to parents dreaming of their child’s acceptance to Harvard, Stanford or Yale, there is mounting evidence that eliminating homework in grade school may actually have great benefits , especially with regard to educational equity.

In fact, while the push to eliminate homework may come as a surprise to many adults, the debate is not new . Parents and educators have been talking about this subject for the last century, so that the educational pendulum continues to swing back and forth between the need for homework and the need to eliminate homework.

One of the most pressing talking points around homework is how it disproportionately affects students from less affluent families. The American Psychological Association (APA) explained:

“Kids from wealthier homes are more likely to have resources such as computers, internet connections, dedicated areas to do schoolwork and parents who tend to be more educated and more available to help them with tricky assignments. Kids from disadvantaged homes are more likely to work at afterschool jobs, or to be home without supervision in the evenings while their parents work multiple jobs.”

[RELATED] How to Advance Your Career: A Guide for Educators >>

While students growing up in more affluent areas are likely playing sports, participating in other recreational activities after school, or receiving additional tutoring, children in disadvantaged areas are more likely headed to work after school, taking care of siblings while their parents work or dealing with an unstable home life. Adding homework into the mix is one more thing to deal with — and if the student is struggling, the task of completing homework can be too much to consider at the end of an already long school day.

While all students may groan at the mention of homework, it may be more than just a nuisance for poor and disadvantaged children, instead becoming another burden to carry and contend with.

Beyond the logistical issues, homework can negatively impact physical health and stress — and once again this may be a more significant problem among economically disadvantaged youth who typically already have a higher stress level than peers from more financially stable families .

Yet, today, it is not just the disadvantaged who suffer from the stressors that homework inflicts. A 2014 CNN article, “Is Homework Making Your Child Sick?” , covered the issue of extreme pressure placed on children of the affluent. The article looked at the results of a study surveying more than 4,300 students from 10 high-performing public and private high schools in upper-middle-class California communities.

“Their findings were troubling: Research showed that excessive homework is associated with high stress levels, physical health problems and lack of balance in children’s lives; 56% of the students in the study cited homework as a primary stressor in their lives,” according to the CNN story. “That children growing up in poverty are at-risk for a number of ailments is both intuitive and well-supported by research. More difficult to believe is the growing consensus that children on the other end of the spectrum, children raised in affluence, may also be at risk.”

When it comes to health and stress it is clear that excessive homework, for children at both ends of the spectrum, can be damaging. Which begs the question, how much homework is too much?

The National Education Association and the National Parent Teacher Association recommend that students spend 10 minutes per grade level per night on homework . That means that first graders should spend 10 minutes on homework, second graders 20 minutes and so on. But a study published by The American Journal of Family Therapy found that students are getting much more than that.

While 10 minutes per day doesn’t sound like much, that quickly adds up to an hour per night by sixth grade. The National Center for Education Statistics found that high school students get an average of 6.8 hours of homework per week, a figure that is much too high according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). It is also to be noted that this figure does not take into consideration the needs of underprivileged student populations.

In a study conducted by the OECD it was found that “after around four hours of homework per week, the additional time invested in homework has a negligible impact on performance .” That means that by asking our children to put in an hour or more per day of dedicated homework time, we are not only not helping them, but — according to the aforementioned studies — we are hurting them, both physically and emotionally.

What’s more is that homework is, as the name implies, to be completed at home, after a full day of learning that is typically six to seven hours long with breaks and lunch included. However, a study by the APA on how people develop expertise found that elite musicians, scientists and athletes do their most productive work for about only four hours per day. Similarly, companies like Tower Paddle Boards are experimenting with a five-hour workday, under the assumption that people are not able to be truly productive for much longer than that. CEO Stephan Aarstol told CNBC that he believes most Americans only get about two to three hours of work done in an eight-hour day.

In the scope of world history, homework is a fairly new construct in the U.S. Students of all ages have been receiving work to complete at home for centuries, but it was educational reformer Horace Mann who first brought the concept to America from Prussia.

Since then, homework’s popularity has ebbed and flowed in the court of public opinion. In the 1930s, it was considered child labor (as, ironically, it compromised children’s ability to do chores at home). Then, in the 1950s, implementing mandatory homework was hailed as a way to ensure America’s youth were always one step ahead of Soviet children during the Cold War. Homework was formally mandated as a tool for boosting educational quality in 1986 by the U.S. Department of Education, and has remained in common practice ever since.

School work assigned and completed outside of school hours is not without its benefits. Numerous studies have shown that regular homework has a hand in improving student performance and connecting students to their learning. When reviewing these studies, take them with a grain of salt; there are strong arguments for both sides, and only you will know which solution is best for your students or school.

Homework improves student achievement.

- Source: The High School Journal, “ When is Homework Worth the Time?: Evaluating the Association between Homework and Achievement in High School Science and Math ,” 2012.

- Source: IZA.org, “ Does High School Homework Increase Academic Achievement? ,” 2014. **Note: Study sample comprised only high school boys.

Homework helps reinforce classroom learning.

- Source: “ Debunk This: People Remember 10 Percent of What They Read ,” 2015.

Homework helps students develop good study habits and life skills.

- Sources: The Repository @ St. Cloud State, “ Types of Homework and Their Effect on Student Achievement ,” 2017; Journal of Advanced Academics, “ Developing Self-Regulation Skills: The Important Role of Homework ,” 2011.

- Source: Journal of Advanced Academics, “ Developing Self-Regulation Skills: The Important Role of Homework ,” 2011.

Homework allows parents to be involved with their children’s learning.

- Parents can see what their children are learning and working on in school every day.

- Parents can participate in their children’s learning by guiding them through homework assignments and reinforcing positive study and research habits.

- Homework observation and participation can help parents understand their children’s academic strengths and weaknesses, and even identify possible learning difficulties.

- Source: Phys.org, “ Sociologist Upends Notions about Parental Help with Homework ,” 2018.

While some amount of homework may help students connect to their learning and enhance their in-class performance, too much homework can have damaging effects.

Students with too much homework have elevated stress levels.

- Source: USA Today, “ Is It Time to Get Rid of Homework? Mental Health Experts Weigh In ,” 2021.

- Source: Stanford University, “ Stanford Research Shows Pitfalls of Homework ,” 2014.

Students with too much homework may be tempted to cheat.

- Source: The Chronicle of Higher Education, “ High-Tech Cheating Abounds, and Professors Bear Some Blame ,” 2010.

- Source: The American Journal of Family Therapy, “ Homework and Family Stress: With Consideration of Parents’ Self Confidence, Educational Level, and Cultural Background ,” 2015.

Homework highlights digital inequity.

- Sources: NEAToday.org, “ The Homework Gap: The ‘Cruelest Part of the Digital Divide’ ,” 2016; CNET.com, “ The Digital Divide Has Left Millions of School Kids Behind ,” 2021.

- Source: Investopedia, “ Digital Divide ,” 2022; International Journal of Education and Social Science, “ Getting the Homework Done: Social Class and Parents’ Relationship to Homework ,” 2015.

- Source: World Economic Forum, “ COVID-19 exposed the digital divide. Here’s how we can close it ,” 2021.

Homework does not help younger students.

- Source: Review of Educational Research, “ Does Homework Improve Academic Achievement? A Synthesis of Researcher, 1987-2003 ,” 2006.

To help students find the right balance and succeed, teachers and educators must start the homework conversation, both internally at their school and with parents. But in order to successfully advocate on behalf of students, teachers must be well educated on the subject, fully understanding the research and the outcomes that can be achieved by eliminating or reducing the homework burden. There is a plethora of research and writing on the subject for those interested in self-study.

For teachers looking for a more in-depth approach or for educators with a keen interest in educational equity, formal education may be the best route. If this latter option sounds appealing, there are now many reputable schools offering online master of education degree programs to help educators balance the demands of work and family life while furthering their education in the quest to help others.

YOU’RE INVITED! Watch Free Webinar on USD’s Online MEd Program >>

Be Sure To Share This Article

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

Top 11 Reasons to get Your Master of Education Degree

Free 22-page Book

- Master of Education

Related Posts

Academic Freedom and Freedom of Expression

Last updated: August 24, 2023, PDF available here .

Frequently Asked Questions

This document is designed to answer common questions about academic freedom, free speech, and freedom of expression in an academic environment. It’s a living document and will be revisited regularly. If you have additional questions or would like to suggest updates to this FAQ, please contact Jennifer Ivers, Associate Dean for Faculty Affairs, at [email protected] . (Please note that this document does cover a lot of ground, so we encourage you to read through all the sections before reaching out to suggest additions.)

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Academic freedom means that researchers and instructors—indeed all Harvard Chan School academic appointees, regardless of their tenure status—have the freedom to investigate, write, publish, teach, and speak about issues in their field of expertise without interference from politicians, donors, funders, trustees, board members, School leadership, or others in positions of power. They can expect critical scrutiny of their academic scholarship from peers but are protected from other forms of pressure.

Academic freedom also ensures that academic appointees can speak freely about the governance of their own institution without fear of retaliation.

The goal is to protect the free exchange of ideas and scholarship, even when they are controversial. Harvard University considers academic freedom an essential value, as noted in the University-Wide Statement on Rights and Responsibilities .

Students have a form of academic freedom. They have the right to express their views in the classroom, including the right to challenge or disagree with course material — what the American Association of University Professors calls the right “to take reasoned exception to the data or views offered” in the course. They can also register concerns about course content with their departmental curriculum committee or the Harvard Chan Committee on Educational Policy . Students do not , however, have the right to opt out of learning course material, or demonstrating that learning on exams and assignments.

Like faculty, students have the right to critique their academic institutions and to express their views as private citizens on matters unrelated to their coursework. They have the right to expect that these expressions will not affect their grades; their academic performance must be evaluated strictly on their demonstrated mastery of the course material.

The School and University do have the right to set policies regarding the time and manner of certain forms of expression, which can impose limits on students’ freedom. Students do not, for instance, have the right to noisily disrupt a class or drown out a guest speaker with protest chants. The Harvard Chan student handbook spells out detailed guidelines for protest and dissent that seek to support free expression without compromising the School’s core educational and research missions.

Academic freedom protects faculty and students from retaliation for expressing their views, but it does not insulate them from critique—even intense, sustained critique—of those views.

Protected speech may at times collide with other deeply held values of our community, such as inclusivity and belonging. As such, it may draw strong critiques, spark intense debates, or generate sustained protest. Strong academic institutions make space for this type of debate, which is reflective of a healthy diversity of viewpoints.

The norm in any academic institution, and the firm expectation at Harvard Chan School, is that controversial speech should be challenged on its substance, through evidence-based debates— not with attacks on the character of the speaker or with calls for coercive or administrative consequences from the School. Such debates should be robust, but always civil. And they should be grounded in an understanding of the principles of academic freedom, which protect faculty and students from disciplinary action for expressing their views on academic matters, as long as they do not violate university policies on discrimination, bullying , and sexual harassment.

Yes. For instance, academic appointees must follow professional guidelines on ethics as well as all applicable laws and regulations when conducting research.

They may need to submit a proposed course to a program or departmental review committee before getting approval to teach it. And they are not free to teach material that would be deemed categorically false by their academic peers.

In addition, all members of the Harvard community must adhere to the University’s policies on bullying, discrimination, and harassment.

Finally, academic freedom does not excuse academic appointees from having to comply with administrative processes or practices adopted for the orderly operation of the School.

Traditionally, the principle of academic freedom has also covered the right of students and academic appointees to speak freely as private citizens without fear of censorship or discipline from their institution.

The Harvard Chan School firmly upholds this right. It also urges all members of the community to use this right responsibly by exercising free speech rights as private citizens with integrity, honesty, accuracy, and respect. In addition, members of the community, especially academic appointees whose titles may carry considerable weight in the public eye, should make clear they are not speaking for the University, their School, or any Harvard department, laboratory, center, or office when they speak out in their capacity as private citizens.

Unfortunately, the power dynamics inherent in academic institutions as well as the external pressures involved with funding and career advancement can make some academic appointees reluctant to pursue specific research, express their views about the institution, or publicly criticize tenured faculty, senior faculty, and/or School leadership, even though academic freedom protects their right to do so.

Students also often feel they are in a vulnerable position and thus may not be comfortable exercising their right to free expression, either inside or outside the classroom. For instance, they may be concerned that challenging faculty or administrators on campus—or sharing controversial views as private citizens—could harm their chances for academic success and career advancement.

Harvard Chan School is committed to supporting community members who seek to address and defuse these power dynamics and training others to do so as well.

ACADEMIC FREEDOM AND USE OF A HARVARD TITLE

Yes, for identification purposes or as needed to describe their work at the School, provided that it is clear they are not speaking for the University or the School.

This is perfectly acceptable. Academic freedom protects the right of academic appointees (as well as students) to speak out as private citizens.

However, the Harvard Chan School strongly recommends that academic appointees clearly state that they are speaking not as scholars, but as private citizens, when commenting on matters outside their field of study. They should also be careful to make clear that their views are their own, and do not reflect any official institutional position.

Note that academic appointees can also choose not to use their Harvard Chan School title and affiliation when speaking out.

Yes. This is a well-defined right within the umbrella of academic freedom.

Yes. The School strongly recommends that they also include a statement that makes clear they are not speaking on behalf of the institution. For more information, see the University’s Guidelines for Using Social Media .

All members of the Harvard community must adhere to the University’s Use of Names and Insignias policy . Among other principles, it requires Harvard affiliates to use accurate titles to represent their current roles.

ACADEMIC FREEDOM IN THE CLASSROOM

Faculty do have a right to share their personal views, but they should consider how doing so can impact classroom dynamics—both in that discussion and throughout the course—and be clear about their goals for, and the academic value of, sharing such views. Among such considerations is the fact that there are unequal power dynamics in a classroom setting. When faculty share their political, ideological, religious, or other personal views beyond the academic content of a class, those views could be experienced as an endorsement or could have a chilling effect on student participation.

For resources about best pedagogical practices and navigating classroom dynamics see Harvard Graduate School of Education Instructional Resources , FAS’s Derek Bok Center , and Teaching and Learning at Harvard Chan.

Yes, instructors may invite any speaker, as long as those speakers conduct themselves professionally, behave respectfully, and do not harass, bully, or discriminate against anyone.

Faculty should also consider other approaches for introducing multiple perspectives on a given topic, such as setting up a mock debate in class with students assigned to represent different perspectives; bringing in a panel of individuals who represent varied perspectives; or showing a video offering a different point of view, followed by class discussion.

Both faculty and students are expected to conduct themselves in a professional manner in the classroom, consistent with relevant School and University policies .

If a speaker in the classroom or elsewhere on campus is expected to draw protests, organizers of the talk should speak with School leadership and the Harvard University Police Department well in advance to ensure time for adequate planning to protect safety and prevent disruption of the School’s regular operations. And those organizing the protests should be mindful of the School’s guidelines on dissent and protest .

ACADEMIC FREEDOM AND INCLUSIVITY

As a community, we strive to provide support to and facilitate dialogue among all individuals affected by any controversy surrounding free speech.

In addition, the Harvard Chan School seeks to provide students (as well as faculty and staff) with the skills they need to engage in substantive and respectful discussion with individuals who hold very different world views. These skills are essential both for a vibrant academic community and for public health leadership in the wider world.

Academic appointees are expected to ensure an inclusive environment.

More specifically, they must adhere to all School and University policies. These include policies related to non-discrimination, bullying, research integrity, Title IX, research collaboration and co-authorship, outside activities, confidentiality of student records, and many more.

It’s important to note that even when a single incident may not rise to the level of a policy violation, an accumulation of such incidents may damage the environment for research, teaching, and/or learning.

Individuals who feel they have been harmed by such incidents should consult the office that manages related policies (e.g., Human Resources, Student Affairs, Faculty Affairs, Office of Diversity and Inclusion, Office of Regulatory Affairs and Research Compliance, etc.) to begin a conversation about how to address their experiences, either formally or informally.

Our guidelines for protest and dissent are spelled out in the student handbook.

Students should be mindful of other policies that may intersect with their rights to protest. For instance, they have a free speech right to walk out of class, but they should understand that this could affect their grades under the School’s attendance policy.

Members of the community should also be mindful of our institutional values, which hold that ideas should be debated on their merits and protests should not devolve into personal attacks or derogatory language or insinuations about the speaker. Students should be mindful that disagreement—even intense disagreement that rises to the level of offense or alienation due to the content of a speaker’s expression—does not entitle them to disrupt a speaker or otherwise interfere with members of the School in the performance of their normal duties and activities.

All members of the Harvard University community must adhere to the new University Policies on Non-Discrimination and Anti-Bullying , as well as policies on sexual harassment and other forms of misconduct. We urge all members of the School community to acquaint themselves with the standards expressed in these Policies, including in particular the definitions of discrimination and bullying and the Anti-Bullying Policy’s commentary on academic freedom:

This Policy should also be construed within the context of the University’s enduring commitment to academic freedom and free inquiry, and the conception of the University as a place that must encourage reasoned dissent and the free exchange of ideas, beliefs, and opinions, however unpopular. This Policy is not intended to constrain the freedom of Harvard community members to engage in academic disagreements or to discuss controversial matters, criticize the administration or University policies, or take part in political protest. (Anti-Bullying Policy at 13-14.)

Members of the community can make complaints through the processes established by the University and the School; those complaints will be reviewed and adjudicated through the established protocols.

HISTORY OF ACADEMIC FREEDOM

The concept has been around for centuries, but its most well-known and widely adopted articulation for academic appointees is contained in the Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure endorsed by the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) and the Association of American Colleges and Universities in 1940.

In 1967, the AAUP and numerous other academic bodies issued a Joint Statement on Rights and Freedoms of Students , which covers academic freedom and free expression for students.

THREATS TO ACADEMIC FREEDOM

Some faculty are concerned that the divisive political climate in the U.S. has contributed to self-censorship: i.e. , that academics may be reluctant to research and/or write on controversial issues for fear of sparking criticism on social media and beyond. They may also be reluctant to assign readings, invite speakers, or launch classroom discussions that could generate a backlash on campus.

In addition, some state legislatures have sought to regulate the content of academic instruction at public colleges and universities within their jurisdictions, particularly on matters that are politically controversial. And some funders may explicitly or implicitly seek to direct outcomes of research they support.

Students, like faculty, may feel uneasy about generating a backlash by speaking out, especially if they hold viewpoints that put them in a minority in their institution. Students may also have the added concern that challenging faculty or administrators at their institution could harm their chances for career advancement by making it harder for them to get good letters of recommendation or prestigious opportunities on campus.

The Harvard Crimson surveyed the Faculty of Arts and Sciences on this and other questions in 2023 and received 386 responses. Among respondents, who may not be a representative sample, nearly 76% said academic freedom is under threat in America. However, 61% said Harvard puts appropriate emphasis on academic freedom.

In April 2023, more than 90 faculty members from across Harvard University formed a new Council on Academic Freedom at Harvard , with the goal of defending academic freedom, free speech, and rational discourse.

The University’s long-standing University-Wide Statement on Rights and Responsibilities articulates Harvard’s vision of institutional and community-wide support for open and constructive academic discourse. We urge all members of our community to read and consider the University-Wide Statement .

RELATED CONCEPTS

Academic freedom primarily refers to the right of academic appointees to research, publish, and teach within their area of expertise. It also covers their right to speak out on other matters as private citizens without fear of retribution from the university. As noted in this document, students are also covered in some respects by academic freedom.

Free speech is a legal concept: The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution protects written and spoken speech, as well as expressive conduct (such as burning a flag) from interference by the government. There are some limitations here: Government can impose some restrictions on the “time, place, and manner” of speech, for instance by requiring permits for a protest march, and certain forms of expression may fall outside the protection of the First Amendment and be subject to regulation, such as defamation, disclosure of classified information, speech that incites violence, and legal obscenity.

In addition, the First Amendment does not apply to private companies or institutions, including private universities such as Harvard.

Freedom of expression is the broad principle that human beings have the right to speak their views. It’s incorporated in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as a fundamental human right. It’s important to note that certain forms of expression may be unlawful, such as slander, disclosure of classified information, or incitement to violence.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

- FAQ on academic freedom from the American Association of University Professors, which provided useful material for this FAQ

- Campus Free Expression: A New Roadmap , a report from the Bipartisan Policy Center

- Harvard’s University-Wide Statement on Rights and Responsibilities

- The faculty-led Council on Academic Freedom at Harvard

- Lancet correspondence on the need for ethical standards for academic behavior

- AP article on a group of universities seeking to elevate free expression on campus

- AAUP statement on collegiality as a criterion for faculty evaluation

- Presentation on bullying and incivility in the academic workplace

- Explorations of academic freedom in various contexts from Northern Illinois University’s Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning

News from the School

Bethany Kotlar, PhD '24, studies how children fare when they're born to incarcerated mothers

Soccer, truffles, and exclamation points: Dean Baccarelli shares his story

Health care transformation in Africa highlighted at conference

COVID, four years in

Student Rights at School: Six Things You Need To Know

While the Constitution protects the rights of students at school, many school officials are unaware of students’ legal protections, or simply ignore them.

When heading back to school this year, make sure to know your rights and ensure that your school treats every student fairly and equally. The ACLU has a long tradition of fighting to protect students’ rights, and is always ready to speak with you on a confidential basis. If you believe that your rights have been violated, don’t hesitate to contact your local ACLU affiliate.

Here are six things you need to know about your rights at school:

1. Speech rights

In the landmark Supreme Court case Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969), the ACLU successfully challenged a school district’s decision to suspend three students for wearing armbands in protest of the Vietnam War. The court declared that students and teachers do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”

The First Amendment ensures that students cannot be punished for exercising free speech rights, even if school administrators don’t approve of what they are saying. Unfortunately, where legal protections are weak, schools are threatening student’s speech – and their privacy – by requiring them to reveal the contents of their social media accounts, cell phones, laptops, and other personal technologies. The ACLU is fighting for new state laws around the country that would provide stronger student privacy protections.

Over the years, the ACLU has successfully defended the right of students to wear an anti-abortion armband , a pro-LGBT t-shirt , and shirts critical of political figures. The ACLU has even defended the rights of high school students who wanted to protest the ACLU .

Contact the ACLU if you believe your school is trying to limit your First Amendment rights.

2. Dress codes

While schools are allowed to establish dress codes, students have a right to express themselves.

Dress codes are all too often used to target and shame girls, force students to conform to gender stereotypes and punish students who wear political and countercultural messages. Such policies can be used as cover for racial discrimination, by targeting students of color over supposed “gang” symbols or punishing students for wearing natural hairstyles and hair extensions. Dress codes can also infringe on a student’s religious rights by barring rosaries, headscarves and other religious symbols.

Schools must make the case that a certain kind of dress is disruptive to school activities. They cannot use dress codes to punish girls, people of color, transgender and gender non-conforming students and free speech.

If you are told to comply with a dress code that you believe is discriminatory, contact the ACLU. Complying with the dress code will not prevent you from challenging it at a later date.

3. Immigrant rights

Schools cannot discriminate against students on the basis of race, color, national origin. Undocumented children cannot be denied their right to a free public education, but some schools continue to create exclusionary policies. Last year, the ACLU sued several school districts for requiring families to prove their immigration status in order to enroll their children in school.

Students with limited English proficiency cannot be turned away by schools, which must provide them with language instruction.

Contact the ACLU’s Immigrants’ Rights Project if you have observed or experienced discrimination based on immigration status or national origin in school.

4. Disability rights

Public schools are prohibited by federal law from discriminating against people with disabilities, and cannot deny them equal access to academic courses, field trips, extracurricular activities, school technology, and health services.

Sometimes, educators and administrators discriminate by refusing to make necessary medical accommodations, restricting access to educational activities and opportunities, ignoring harassment and bullying, and failing to train staff on compliance with state and federal laws.

Schools have a duty to defend students with disabilities from bullying and biased treatment, and the ACLU is working to ensure that the rights of these students are protected.

5. LGBT rights

Bullying of LGBT students can be pervasive at schools, and is all too often ignored or encouraged by the schools themselves. LGBT students have a right to be who they are and express themselves at school. Students have a right to be out of the closet at school, and schools cannot skirt their responsibility to create a safe learning environment and address incidents of harassment.

Public schools are not allowed to threaten to “out” students to their families, overlook bullying, force students to wear clothing inconsistent with their gender identity or bar LGBT-themed clubs or attire . Transgender and gender non-conforming students often face hostile environments in which school officials refuse to refer to students by their preferred gender pronouns or provide access to appropriate bathroom and locker room facilities.

If you find that your school is undermining your rights, contact your local ACLU affiliate or the ACLU LGBT Project . Be sure to report incidents of bullying or bias to a school principal or counselor and remember to keep detailed notes of your interactions with officials and make copies of any paperwork that the school asks you to fill out.

6. Pregnancy discrimination

Since Title IX, the federal law barring sex discrimination in education, was passed in 1972, schools have been prohibited from excluding pregnant students and students with children. Yet schools often push such students to drop out by making it impossible to complete classwork, preventing them from participating in extracurricular activities, refusing to accommodate schedule adjustments, punishing them with unwarranted disciplinary actions, and pressuring them to transfer or quit school altogether.

Denying these students an education, access to school activities and reasonable accommodations violates their rights. Public schools must ensure that pregnant students have access to the same accommodations that students with temporary medical conditions are given, including the ability to make up missed classwork and learn in a safe, nonjudgmental environment. Schools are also not allowed to punish students who choose to terminate a pregnancy or reveal a student’s private medical information.

If you believe that your school is treating you unfairly for being pregnant, ending a pregnancy, or having a child, contact the ACLU’s Women’s Rights Project .

Learn More About the Issues on This Page

- Juvenile Justice

Related Content

It's Time to End Solitary Confinement: Ian Manuel's Story

The Consequences of Police in Schools: A North Carolina Case Study

Under Public and Legal Pressure, Louisiana Finally Moves Children Out of Angola Prison

Appeals Court Allows Louisiana to Keep Children in Angola Prison

College of Liberal Arts

Academic freedom in the classroom.

Students’s Guide to Academic Freedom in the Classroom

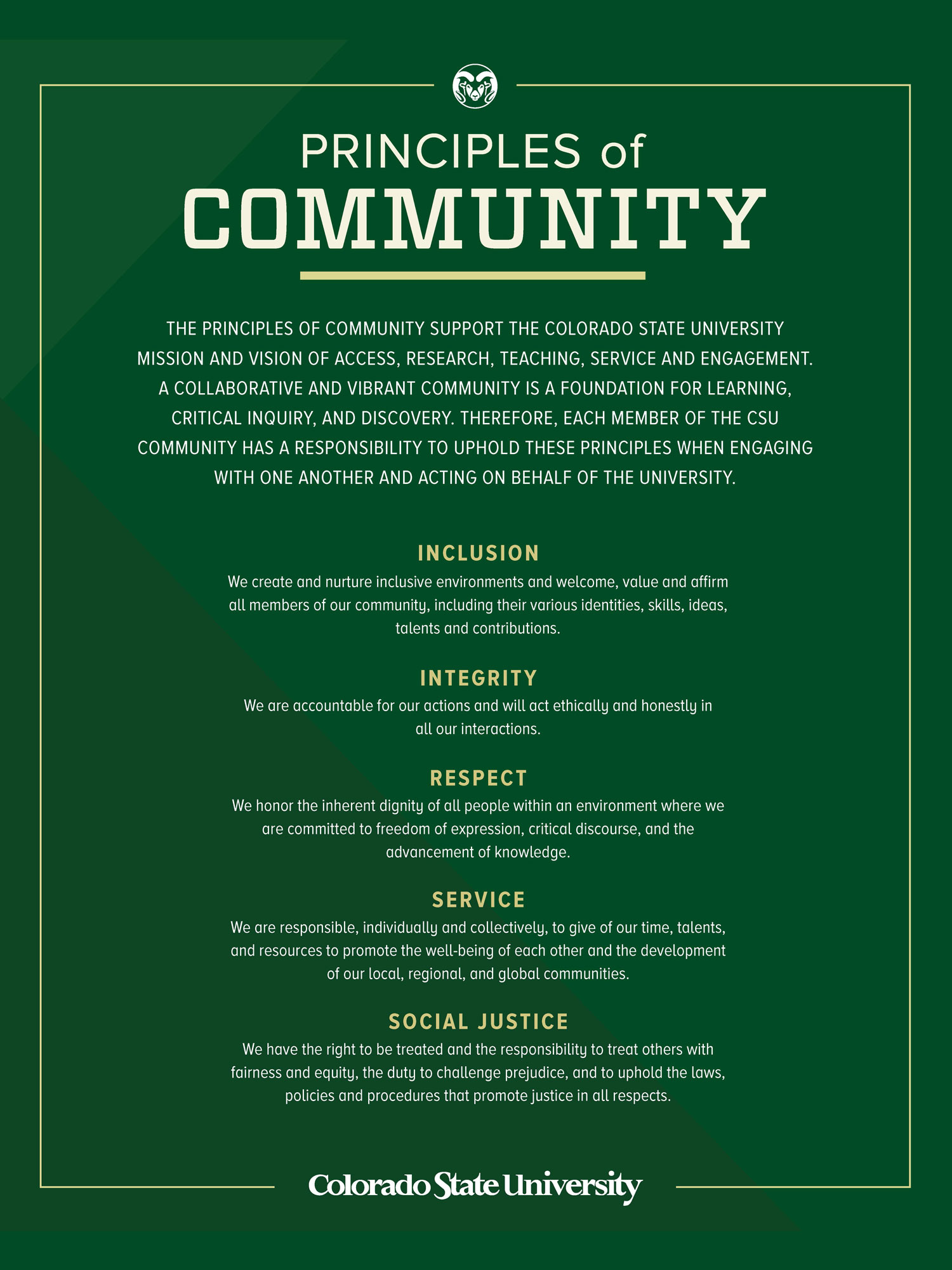

Colorado State University’s guiding principles emphasize that all members of the university community share in the pursuit of knowledge and development of students. The College of Liberal Arts celebrates the central role of free speech in upholding these guiding principles.

Colorado State University has official policies around free speech, academic freedom, and campus climate that establish codes of conduct. Relevant policies are linked at the end of this document.

Your professor wants you to have the freedom to learn.

The freedom for students to learn, explore, and challenge ideas while building and sharing your own opinions is the foundation of what is called academic freedom .

The freedom to learn . This freedom protects students from unfair treatment by instructors based on the student’s opinions and beliefs. It recognizes that student opinions are valuable and should be able to be expressed without fear of retribution by the leader of the class. At the same time, the freedom to learn obligates students to follow class assignments and master course content, even if they disagree with it.

Professors and institutions of higher education also have academic freedom that protects them in complementary but different ways.

Back to top

Academic freedom protects your right to your own ideas and views.

Academic freedom protects you when you disagree with your instructor or other students in the context of class discussions and assignments.

Academic freedom gives you three specific protections:

- The protection of freedom of expression in the classroom. Students are free to take “reasoned exception” to concepts and theories presented in their classes and to disagree with opinions they hear from their instructors, even as they continue to be responsible for learning assigned course content

- The protection against improper academic evaluation. Students are shielded from “prejudiced or capricious” evaluation of their academic performance by instructors

- The protection against improper disclosure. A student’s “views, beliefs, and political opinions” shared with a professor during professional interactions should be kept confidential and should not be shared by the professor with others

Things to know about Academic Freedom:

- CSU affirms that academic freedom means that no student should be penalized because of political opinions that differ from a professor’s. Every student should feel comfortable in the right to listen critically and challenge a professor’s opinions.

- Academic freedom is granted to professors (tenured, tenure-track, non-tenure track faculty and instructors), students (undergraduate and graduate), and institutions of higher education like CSU.

- The academic freedom for these groups is not identical; rather, these freedoms are complementary, working together to ensure the academic freedom of the entire university community.

“The faculty of Colorado State University considers freedom of discussion, inquiry, and expression to be in keeping with the history and traditions of our country and to be a cornerstone of education in a democracy.”

– CSU Memorandum of Understanding on Academic Freedom

Academic freedom is not the same as Freedom of Speech.

In the classroom, academic freedom means you have the right and responsibility to participate in a welcoming and inclusive learning environment.

Freedom in Public Speech . On CSU campus, public areas like the Lory Student Center Plaza are “open to all individuals for the purpose of exercising free speech and assembly.” This means that the CSU community has the right to express their views, no matter how controversial, in public areas unless that expression is disruptive or unsafe.

Classroom Speech Is Different. According to CSU policy on Freedom of Speech, classrooms have different rules than public areas. Classrooms are considered non-public areas – that is, places “normally not intended to be open to the general public for purposes of expressive activities or gatherings.” Non-public areas do not fall under the same policies about free speech that public areas do.

That means that certain types of speech allowed in the plaza are not allowed in classrooms, including demonstrations, amplified sound, and signage, as well as “any activity that interferes with academic or operational functions.” Discriminatory or harassing speech are also not allowed.

Things to know about the First Amendment:

- Outside of the classroom, the campus constitutes a looser zone of largely unrestricted speech, as guaranteed by the First Amendment.

- True threats to, and/or harassment of, individuals are not protected speech anywhere. They each have a specific legal definition and are usually determined on a case-by-case basis.

The First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States

“ Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble … ”

Respect and support the academic freedom of professors.

Recognize that professors have equally valuable and complementary academic freedoms that must be respected, including the freedom to discuss controversial or challenging topics.

The freedom to teach . This aspect of academic freedom protects the right of instructors to teach their subject-matter however they choose without interference from the institution, the government, or their discipline. It recognizes professors as experts and protects them from punishment for discussing challenging or controversial topics as long as those topics are relevant to the subject of the class.

Exercise your academic freedoms within the Principles of Community.

As you challenge ideas and express yourself in the classroom, make sure you do so with a spirit of inclusion, integrity, respect, service, and social justice according to the CSU P rinciples of Community .

In class, controversial topics can and do arise, especially in the subjects taught in CLA. Other students may express sentiments you find noxious or abhorrent. Current events, particularly in a contentious election year, may provoke you to sincere and genuine outrage that you feel compelled to share.

Inclusion, integrity, respect, service, and social justice. These goals for how we interact with each other means considering our own voice alongside the voices of those around us in the spirit of these Principles of Community. You can and should exercise your discretion when tensions arise, potentially responding directly to offensive speech in the classroom with speech of your own, bearing in mind that your responsibility as a student is to treat others with respect and dignity.

Respect and support the academic freedoms of other students.

Be sure to respect other students’ academic freedom by listening to those you disagree with and responding with your own ideas and opinions in a respectful manner.

The central role of inclusivity. CSU’s land grant mission of access emphasizes that all are welcome to come and learn with us. When someone express ideas that offend others in class, a proper response is often more speech. Engage your instructors and fellow students in a respectful way that doesn’t hinder their academic freedom or yours.

Students should feel empowered to engage with difficult or offensive speech in a respectful and direct manner if the speech relates to class material.

Feeling welcomed in the classroom. CSU’s inclusivity policy makes instructors responsible for “creating and sustaining a welcoming, accessible and inclusive campus.” This means actively valuing all voices and contributors, while working to eliminate intentional and unintentional incidents of bias.

Our Principles of Community , along with CSU policy, emphasize students’ right to a classroom environment that allows them to think freely and learn for themselves. That means different opinions must be welcome in our classrooms, even if those opinions are unpopular.

Recognize your academic freedom is not unlimited.

When you express your disagreement with a professor or fellow student, avoid discriminatory, threatening, and disruptive language and behavior. Students are responsible for upholding the Student Conduct Code when exercising their academic freedom.

Avoid threats, discrimination, and harassment . An important aspect of participating in an inclusive learning environment is following the CSU Student Conduct Code, which prohibits behavior that “disrupts or interferes with teaching, classroom, or other educational interactions,” including “verbal abuse, threats, coercion, or other conduct, through any method of communication, which threatens or endangers the physical or psychological health, safety, or welfare of any person.”

Similarly, CSU prohibits harassment or discrimination in order to provide an environment that is free from “discrimination based on race, age, creed, color, religion, national origin or ancestry, sex, gender, disability, veteran status, genetic information, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, or pregnancy.”

These guidelines do not mean you can’t bring up about controversial or emotionally charged topics in the classroom, but they do emphasize the need for respectful, open dialogue.

Follow up if you feel your academic freedom has been constrained.

You have the right to discuss with your professor any constraints you feel have been placed on your academic freedom.

If you feel your freedom to learn, freedom of expression, protection against improper academic evaluation, or protection against improper disclosure have been violated, you have the right to address the issue. The Student Resolution Center can assist students with how to start this conversation with their instructors.

To address issues that arise:

- First, make an appointment to discuss the issue with your instructor or professor. Ask another faculty or staff member to accompany you to the meeting if you feel the need to do so.

- For the meeting, write up a clear and detailed description of the issue to help you explain and keep a record

- If the issue remains unresolved, seek guidance from the Student Resolution Center for next steps.

CSU has several ways you can report concerns about the behavior of CSU community members, including:

- Incidence of Bias reporting - A bias incident is any conduct, speech, or expression, motivated in whole or in part by bias or prejudice that is meant to intimidate, demean, mock, degrade, marginalize, or threaten individuals or groups based on that individual or group’s actual or perceived identities.

- Student Conduct Code violation reporting – The Student Conduct Code defines University intervention, resolution options and possible disciplinary action related to the behavior of both individual students and student organizations.

- Tell Someone - If you are concerned about safety or mental health – your own or someone else’s –call (970) 491-1350 or complete the online referral form.

CSU Policies relevant to Academic Freedom, Freedom of Speech, and Classroom Climate

- Student Conduct Code, Prohibited Student Behavior pp. 3 – 6

- Free Speech and Peaceful Assembly

- Freedom of Expression and Inquiry

- Inclusive Physical and Virtual Campus

- Discrimination, Harassment, Sexual Harassment, Sexual Misconduct, Domestic Violence, Dating Violence, Stalking, and Retaliation

- “ Memorandum of Understanding on Academic Freedom ” (2004)

- “Academic Freedom” in Section E.8: Academic Faculty and Administrative Professional Manual of Colorado State University

Learn more about Academic Freedom

- The 1940 Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure

- The 1967 Joint Statement on Rights and Freedoms of Students

- The 1993 Report on the Joint Statement on Rights and Freedoms of Students

- “ Freedom of Expression and Inquiry ” and “ Student Rights ” in the Colorado State University Catalog

- Cary Nelson, “ Defining Academic Freedom ,” Inside Higher Ed , December 21, 2010

- Henry Reichman, “ On Students Academic Freedom ,” Inside Higher Ed , December 4, 2015

Submit to Digest

Student free speech rights on the internet: summary of the recent case law, written by laura fishwick - edited by adam lewin.

Introduction

The most recent U.S. Supreme Court case to address the legality of school-imposed punishment for student expression was more than forty years ago in Tinker v. Des Moines Indep. Cmty. Sch. Dist. , 393 U.S. 503 (1969). In that seminal case , the Supreme Court found that a state’s interest in maintaining its educational system can justify limitations on students’ First Amendment rights to the extent necessary to maintain an effective learning environment. Id. In Tinker , school officials suspended students for wearing black arm bands to protest the Vietnam War. Articulating the standard still used by courts today, [1] the Court held that a school may regulate student speech or expression if school officials can reasonably conclude that such speech caused or is likely to cause a “material and substantial” disruption to school activities. Id. at 513 (finding no substantial disruption because the protests were non-violent and did not interfere with class activities).

Tinker and subsequent Supreme Court cases have not addressed whether a school may regulate student speech that occurs off campus or online and is not connected to a school event, but that nonetheless causes disruption on campus or in the classroom. Further complicating the analysis of on campus, off campus, and online speech are additional factors such as the location where recorded activity takes place before it is posted online, and the location of the computer used to upload data onto the Internet. This comment explores the recent lower court decisions applying the Tinker standard to school-enforced limits on student speech made on the Internet. In cases of off campus or online speech, some courts have responded to the fact that Tinker involved on campus speech by requiring the school to show a substantial nexus between the speech and the school before applying Tinker . Beyond the nexus inquiry, courts move onto Tinker and examine the intensity of on campus discussions surrounding the expression, the burden the expression places on the administration, and whether the expression contains violent content.

The Threshold Question

Lower courts are divided on the issue of whether to ask a threshold question — is there a sufficient nexus between the off campus speech and the school — before reaching Tinker ’s “material and substantial disruption” test. The majority of district courts have not required this threshold inquiry, but some courts, notably the Second Circuit, have required that a nexus be shown by proving that it was “reasonably foreseeable” that the speech would reach a school’s campus. See J.C. v. Beverly Hills Unified Sch. Dist. , 711 F. Supp. 2d 1094, 1107 (C.D. Cal. 2010) (summarizing the rift among courts on the nexus threshold question). Courts that ask the nexus question are concerned with whether the student, at the time he posted the expression, should have foreseen that the speech would enter and affect activities on campus. This standard is different from the Tinker standard, discussed in the next section, which is concerned with whether the expression has caused or foreseeably will cause substantial disruption on campus, from the perspective of the school officials when they decided to punish the student or prevent the conduct.

Many courts find that schools may regulate any speech which causes or is likely to cause a substantial disruption of school activities whether or not there is a nexus between the speech and the school. See Beverly Hills , 711 F. Supp. 2d at 1107. For example in Harrell , the court did not consider the nexus issue where a school punished a college student for his comments on an online forum as part of the curriculum for an online class. Harrell v. S. Oregon Univ. , No. 08-3037-CL, 2009 WL 3562732, *5–6 (D. Or. 2009), aff’d , 381 Fed. Appx. 731 (9th Cir. 2010). In another case, the Western District of Pennsylvania applied Tinker without regard to the geographic origin of the speech where a student composed a degrading “top-ten” list that he distributed to friends over email, and where one recipient brought the list to campus. See Killion v. Franklin Reg’l Sch. Dist ., 136 F. Supp. 2d 446, 455 (W.D. Pa. 2001); see also , O.Z. v. Bd. of Trustees of Long Beach Unified Sch. Dist. , No. CV 08-5671 ODW, 2008 WL 4396895, *4 (C.D. Cal. 2008) (applying Tinker where a student created a video off campus depicting a graphic dramatization of a teacher’s murder, which he posted online); Beussink v. Woodland R-IV Sch. Dist. , 30 F. Supp. 2d 1175, 1180 (E.D.Mo. 1998) (applying Tinker where a student created a website while he was off campus that criticized school authorities, and another student showed the website to a teacher). Courts that bypass the nexus question generally do not give their reasoning for doing so but simply choose to not consider the issue.

Many other courts choose not to address whether the nexus test should be used when the resolution of the issue is not essential to the outcome of the case. See e.g. , J.S. ex rel. Snyder v. Blue Mountain , 650 F.3d 915, 926 (3d Cir. 2011) cert. denied , 2012 WL 117558 (U.S. Jan. 17, 2011) (No. 11-502); T.V. & M.K. v. Smith-Green Cmty. Sch. Corp. , No. 1:09-CV-290-PPS, 2011 WL 3501698, *11 (N.D. Ind. 2011). In Beverly Hills , the Central District Court of California found that because the threshold question as framed by the Second Circuit would have been easily met, it did not need to decide whether or not a nexus inquiry was necessary before moving to Tinker . 711 F.Supp.2d at 1107–09. The plaintiff in that case, a high school student, posted on YouTube a video of another student making disparaging and defamatory comments of a third student. Id. at 1097–98. The court found that it was foreseeable that the video would reach the school’s campus because the plaintiff posted the video on a weeknight, contacted five to ten students to tell them to watch the video after it was posted, contacted the subject of the video, and made the kind of defamatory and derogatory comments that would compel a parent to bring the video to the attention of school officials. Beverly Hills , 711 F.Supp.2d at 1107–09. Even though students did not have access to the video while on campus due to the school’s restrictive Internet policies, the court still found the “reasonable foreseeability” nexus standard could have been satisfied, were it necessary, because administrators had access to the video while on campus. Id.

However, as mentioned earlier, a minority of courts require a showing of “a sufficient nexus” before they will confront the Tinker standard. These courts though are divided when it comes to defining this term. The requirement that the speech be sufficiently related to the school for Tinker to apply was first articulated by the Second Circuit in Thomas v . Bd. of Educ., Granville Cent. Sch. Dist. , 607 F.2d 1043, 1050 (2d Cir. 1979). In Thomas , the court found that Tinker was inapplicable where students created a satirical newspaper that they deliberately tried to keep off campus because “all but an insignificant amount of relevant activity in this case was deliberately designed to take place beyond the schoolhouse gate.” Similarly in a later case, the Fifth Circuit found Tinker inapplicable where a student brought a violent drawing that his brother had made at home two years earlier to school because the brother did not take any action to increase the chances that the drawing would make its way to campus and the drawing was not “publicized in a way certain to result in its appearance at [the School].” Porter v. Ascension Parish Sch. Bd. , 393 F.3d 608, 615–20 (5th Cir. 2004).

Several decades after Thomas , the Second Circuit addressed online speech in Wisniewski and adopted the “reasonably foreseeable” test to determine whether there was sufficient nexus between the speech and the school. Wisniewski v. Bd. of Educ. of the Weedsport Ctr. Sch. Dist. , 494 F.3d 34, 39–40 (2d Cir. 2007). In Wisniewski, school officials suspended a middle school student for using an AOL Instant Messaging avatar that depicted a pistol firing a bullet at a man’s head above the message “kill [the student’s English teacher].” Id. at 35–36. The court required that the student’s expression reaching school property be reasonably foreseeable before applying Tinker , and found foreseeability because the image was of a violent nature and because the student had transmitted the image to fifteen other students during a three week period. Id. at 39–40.

In another case involving online expression before the Second Circuit, school officials had reprimanded a high school student for emailing students and parents and posting a message on her personal blog that criticized the school for canceling a school event, encouraging students and parents to complain to the school. Doninger v. Niehof , 642 F.3d 334, 345–47 (2nd Cir. 2011), cert denied , 2011 WL 3204853 (2011). Applying the standard found in Wisniewski , the court found that it was reasonably foreseeable that the student’s message would disrupt school activities or administration because it directly encouraged students and parents to contact the school. Id. at 48–50 (holding that “a student may be disciplined for expressive conduct, even conduct occurring off school grounds, when this conduct ‘would foreseeably create a risk of substantial disruption within the school environment,’ at least when it was similarly foreseeable that the off-campus expression might also reach campus”).

Other courts have set more vague standards for finding a sufficient nexus between the expression and the school. For example, the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania found a sufficient nexus in Bethlehem where a student had created a website — that he had accessed during class and informed other students about — containing violent, highly threatening, and derogatory comments about school officials. J.S. v. Bethlehem Area Sch. Dist. , 807 A.2d 847, 666 (Pa. 2002) (specifying that purely off campus speech would “arguably be subject to some higher level of First Amendment protection”). Without citing the Second Circuit’s foreseeability test, the court reasoned that such a nexus existed because of the easy access that students and school officials had to the website, and because school officials were subjects of the website. Id. at 667–68.

Despite requiring a threshold showing of a nexus before they will apply the Tinker standard, few courts, if any, have found that a sufficient nexus does not exist between online speech and a school when applying the “reasonably foreseeable” test. As the Beverly Hills court noted, cases requiring this threshold question “more readily find a sufficient nexus where speech over the Internet is involved.” Beverly Hills , 711 F.Supp.2d at 1108. This is most likely due to the uniquely pervasive and widely accessible nature of the Internet, because of which it is foreseeable that almost anything posted online may be viewed in schools by students, teachers, and administrators, thereby satisfying the foreseeability nexus threshold test.

Even though it is nearly always satisfied in cases of online speech, this test shows no signs of disappearing, and courts continue to administer the threshold nexus test before asking whether the expression did in fact or was foreseeably likely to cause substantial disruption. The persistence of the nexus test may be explained by the fact that courts do not undergo different analyses for online speech and off campus speech, and many courts even tend to view online speech as a subset of off campus speech. Unlike cases of online speech, courts do find that some off campus speech cases fail to satisfy the sufficient nexus test. See, e.g. , Porter , 393 F.3d at 615–20; Thomas , 607 F.2d at 1050. In this sense, asking whether there is a sufficient nexus in cases of online speech is a vestigial question of the pre-Internet era.

Despite the absence in the case law of courts finding that online speech did not foreseeably reach campus, one can imagine cases that might fail the nexus test: where the student did not consent to uploading a recording of the speech onto the Internet, or where the student actively tried to keep the expression away from the school. Such cases would be analogous to Thomas and Porter , discussed above, where the courts found that Tinker did not apply because the students involved either did not play a role in bringing the off campus speech onto campus or actively tried to keep the speech off campus. On the other hand, even private online communications can be easily shared, making it unrealistic to expect that most online speech would not reach a school’s campus.

The future utility of the nexus test should not be understated. It may be seen as a way for courts to avoid applying the Tinker substantial disruption test in cases of valuable online speech made by students that is not directed at the school or its students. See Blue Mountain , 650 F.3d at 939 (Smith, J., concurring) (observing that applying Tinker in all cases would allow school officials “to regulate students’ expressive activity no matter where it takes place, when it occurs, or what subject matter it involves — so long as it causes a substantial disruption at school”). The Supreme Court in Tinker could not have intended to allow schools to regulate all student expression that occurs anywhere simply because it happens to disrupt school activities. A student might upload a blog post discussing a sensitive political or social topic that is unrelated to the school or its students but that causes substantial disruption at the school. Allowing a school to punish that student might raise serious constitutional issues. An easy way for courts to avoid this problem would be to use a nexus test and to find that such speech cannot be regulated because it does not have a sufficient nexus with the school.

Tinker ’s Substantial Disruption Standard

Beyond the nexus inquiry, the Tinker substantial disruption test requires a showing that either actual substantial disruption to school activities occurred on campus or that school officials reasonably foresaw substantial disruption and acted to prevent that disruption or deter future disruption. Tinker , 393 U.S. at 513. Though no actual disruption is required for school officials to have reasonably foreseen disruption, Tinker required school officials to at least have evidence of future substantial disruption, more than an “undifferentiated fear or apprehension of disturbance.” Id. at 508. The Court also required something more than “a mere desire to avoid the discomfort and unpleasantness that always accompany an unpopular viewpoint.” Id. For example, in holding that substantial disruption was not foreseeable, the court in Smith-Green rejected the School’s arguments that the principal had experience with similar situations that caused a disturbance and wanted to “get off on the right foot” at the start of the school year, finding that more evidence was required. Smith-Green , 2011 WL 3501698, at *14 . The court in Bowler also found that substantial disruption was not reasonably foreseeable where students would need to go through a complex series of steps to be disturbed by links on a student’s website that the student had advertised on posters hung around the school. Bowler v. Town of Hudson , 514 F. Supp. 2d 168, 177–78 (D. Mass. 2007).

First, in determining the extent of the disruption, courts explore the magnitude of student discussions in classrooms and around campus. The speech at issue must actually or foreseeably disrupt classroom activities, more than merely causing discussion of the speech among students. See Beverly Hills , 711 F. Supp. 2d at 1111. In Harrell , the court found that a university student, who had criticized and put-down his professor and other students many times in two online class forums, had substantially disrupted class activity because his hostility caused many students in the class to stop participating online or to become significantly discouraged from doing so. Harrell , 2009 WL 3562732, at *4, 6 (one teacher commented that the student had “shredd[ed] the other students’ espirit de corps irreparably”). This case is contrasted with Blue Mountain , where the court noted in dicta that no actual disruption had occurred after the plaintiff student created a fake MySpace profile for her school principal, which depicted the principal as a pedophile and sex addict, because only a few students discussed the profile with the plaintiff at school and did not interrupt class time apart from discussions led by a few teachers. 650 F.3d at 928.

Courts also consider whether school administrators are pulled away from their ordinary tasks to respond to the effects of the student’s speech. See Beverly Hills , 711 F. Supp. 2d at 1113–14. In Doninger , for example, the court found substantial disruption where the student’s conduct resulted in “a deluge of calls and emails” for the principal and superintendent “and many upset students.” 642 F.3d at 51. At the other end of the spectrum, in Smith-Green , the court found no evidence of actual substantial disruption because only two parents complained to the administration and there was otherwise no disruption to any school activity. 2011 WL 3501698, at *12–13.