- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

How to Make a Cover Page for a Notebook

Last Updated: February 12, 2023 Fact Checked

Supplies and Design

Computer editing.

This article was co-authored by wikiHow Staff . Our trained team of editors and researchers validate articles for accuracy and comprehensiveness. wikiHow's Content Management Team carefully monitors the work from our editorial staff to ensure that each article is backed by trusted research and meets our high quality standards. There are 12 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 158,238 times. Learn more...

Keeping track of all your notes for school can get confusing if you’re disorganized. Luckily, creating a custom cover page for the front of your notebook will make separating your work easier, and it’s a fun and inexpensive project you can do to add some personality to your school materials. With just a few basic art supplies or a simple computer photo editor, you can create a notebook cover page that says “you” and makes doing your homework a little more interesting.

- You can decorate the first page of a notebook to use as your cover page or draw directly onto the outside of the notebook. If you decide to decorate the first page, it may be helpful to color-coordinate your notebooks so that you know which subject goes with each color.

- Designing your cover page on a computer will be easiest if you use a 3-ring binder since the printed cover page can slip directly into the front of the binder.

- Make sure you're also stocked on notebook paper if you're using a 3-ring binder so you'll be ready to go once your cover page is done.

- Listing your homeroom teacher or locker number will help other students return a lost notebook.

- Use drawings and pictures that fit with the subject of your notebook to give your studies a visual element. If you're designing a notebook for your chemistry class, for instance, sketch a few beakers and flasks or a microscope to go along with the chemistry motif.

- As long as it’s not against the rules, you could even write down formulas or other useful tips on your notebook cover to help you remember them. Putting the Pythagorean theorem on a math notebook, for instance, will aid you in learning the theorem so that it’s instantly recognizable to you.

- Use your own supplies, or see about borrowing them from your school’s art class.

- Use foam craft letters for a cool new way to display your name on your notebook.

- Be careful while gluing decorations onto your notebook and make sure you only use as much as you need. Otherwise the glue can bleed through and make the paper soggy, or you might even accidentally glue pages together.

- Word processors make it easy to format text the way you want it and add pictures to go with it, while one advantage of photo editing programs is that they give you greater control over how to alter pictures and let you drag, layer and angle bits of text for better customization.

- You don't have to limit yourself to just one method—try designing a cover page with the necessary basic information on your computer, then printing it out and finish decorating it by hand.

- Don’t use photos that are graphic or offensive. Remember, your notebook is part of your scholastic materials.

- Fonts like Impact, Comic Sans and Wingdings come preloaded on most word processors programs and are more playful than ordinary professional fonts.

- If you enjoy writing creatively, challenge yourself by coming up with a personalized slogan to act as an introduction for what you'll find in your notebook.

- Taping or stapling around the edge of the cover page will hold it in place and allow it to be changed out at a later time with little difficulty, while glue will hold better but is messier to work with and isn’t easily removed.

- Be careful: watch your fingers while you’re stapling.

Community Q&A

- Look up notebook cover templates or ask your friends to get ideas about how to decorate your cover page. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Have a parent or teacher help you use a word processor or photo editor to design your cover page if you’re not sure how. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- If you have to do a project for art class, you might be able to kill two birds with one stone by choosing to make a notebook cover page as your project. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- If you use pictures to decorate your notebook, make sure they’re appropriate to be seen at your school. Thanks Helpful 10 Not Helpful 1

- Markers bleed, so don't use them unless you have a notebook with a cardboard cover. Thanks Helpful 11 Not Helpful 4

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://www.jetpens.com/blog/notebooks-explained/pt/647

- ↑ https://www.thesprucecrafts.com/diy-notebook-covers-4142307

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sjgKTS8Eu_Q

- ↑ http://aboutfamilycrafts.com/18-ways-to-decorate-your-notebooks/

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GhWRJxWhCR4

- ↑ http://www.freekidscrafts.com/paper-crafts/cut-and-paste-crafts/

- ↑ https://support.office.com/en-us/article/Create-visually-compelling-documents-in-Word-2010-5028b228-048c-4867-ba4a-2169e06f1f16

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=61mkx_OV61s

- ↑ https://pixlr.com/

- ↑ https://images.google.com/

- ↑ http://classroomclipart.com/

- ↑ http://www.instantshift.com/2012/04/12/study-of-font-styles-and-best-uses-for-each/

About This Article

Making a cover page for your notebook is a fun way to personalize it and make finding your work easier. Write the subject of the notebook in big text at the top of your cover page. Then, write your name, your teacher’s name, and your locker number if you have one, so people can easily return your notebook if you lose it. Decorate the page however you want. You can draw pictures and patterns around the page with colored pens, place stickers, or glue sequins to bring it to life. Alternatively, design your cover page on a computer, print it out, and stick it to your notebook. Just make sure you set the page size to match your notebook. For more tips, including how to copy cool pictures onto your cover page on a computer, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Did this article help you?

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Level up your tech skills and stay ahead of the curve

Free Bullet Journal Printables

21 Captivating Notebook First Page Ideas

Sharing is caring!

Are you starting a new notebook and looking for Bullet Journal page ideas for your front page? You’re in the right place!

The thought of writing in a blank notebook can be both exhilarating and intimidating. It’s so full of possibilities!

But at the same time, it’s wide open, with no real direction or guidance on what to write first…

What should you put on that all-important first page?

Well, have no fear – I’ve got some ideas for how to get started filling those pristine pages. Today we’ll talk about creative ways to create your own unique ‘first page’ spread in your notebooks.

Whether you are looking for a simple design and format or want to go all-out creative and put personal touches on this introductory page, there’s no shortage of ideas out there!

I have compiled some fun and inspiring ways that will help bring your new Bullet Journal to life.

And don’t forget to scroll until the end of the post to get your free front page printable.

21 Notebook First Page Ideas

Here are 21 unique ideas for the perfect Bullet Journal first page that are sure to make your creative dreams come true.

It’s important for the first page of your notebook to set an inspirational tone that will help carry your thoughts and ideas throughout its pages.

The first page seems very intimidating, and it definitely can be something that would hold you back from starting your journal right away, so let’s look at a few ideas that will definitely spark your imagination.

Why not start your journal with a wish list? Something you want to happen in the upcoming year, or maybe something you want to change in your life. Or it could be a wish list for things you want your journal to help you with.

- About me page

This is my favorite way to start a Bullet Journal! There are many things you can do with this page, but my preference is to use it as a little milestone with information about where you are in life at the moment you start this journal.

- Contact details

In case you ever misplace your journal, adding contact details might be a good idea to make sure when people find it; they know who to give it back to.

- News headline from today’s day

Kind of a different way to do it, but why not? Especially if you can find a headline that speaks to you. Plus, you can get so creative with this idea!

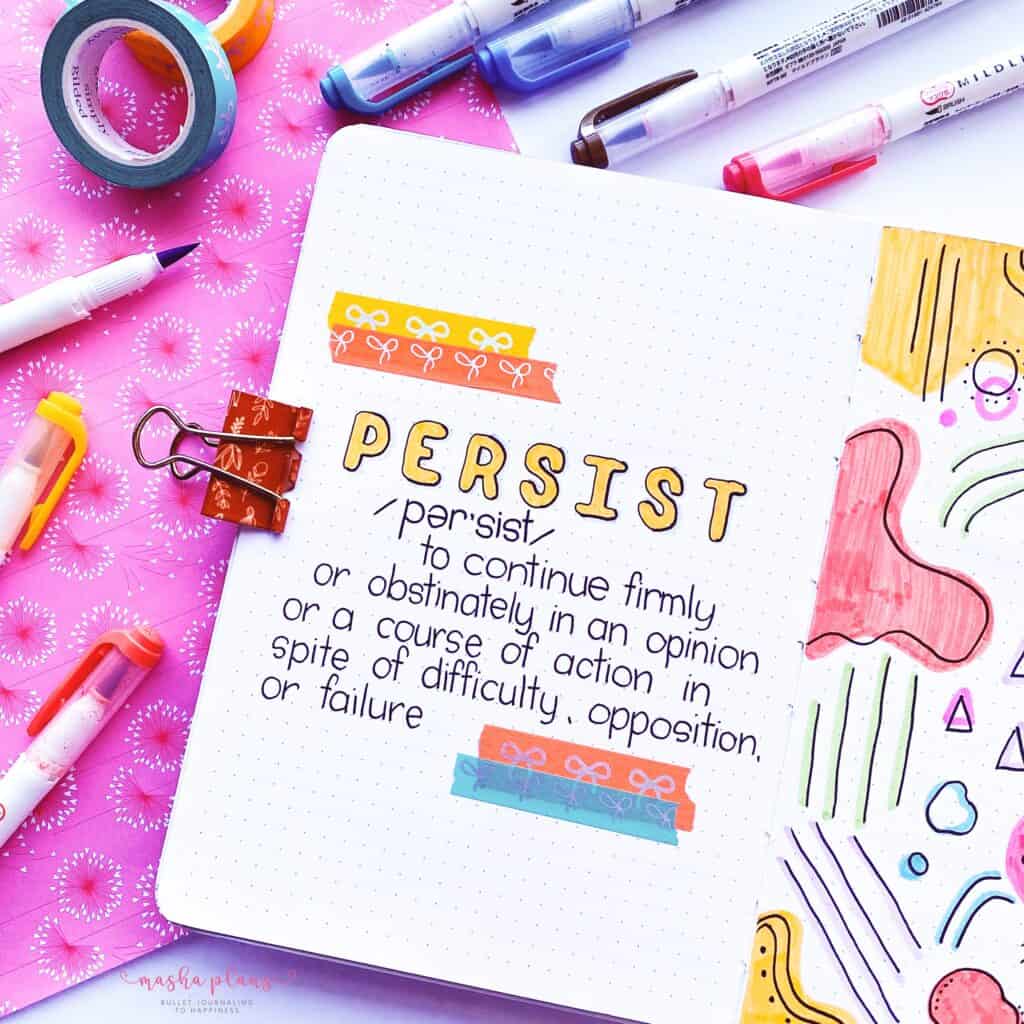

- Word of the year

This is a really fun practice to pick one word that would be kind of your mantra for the upcoming year.

- Your favorite poem

This would definitely help you set up the mood for your journal and make it more your own since our favorite poem tells a lot about you.

Why not have fun with your first page and create a little collage? Pick a different colored paper and some stickers you have in your collection, and try to put it all together and create something unique and pretty.

Key is one of the basic Bullet Journal pages, and chances are you’ll need to include it in your setup anyways, so why not use it as your first page?

- Prayer or affirmation

Speaking of starting a journal on the right note, why not add a prayer or affirmation, something you can look at every time you open the journal that would cheer you up?

- Notebook theme

You can create Bullet Journals for all types of purposes, for work, for your daily planning, and for memory keeping. Maybe spend the first page clarifying what type of journal this is.

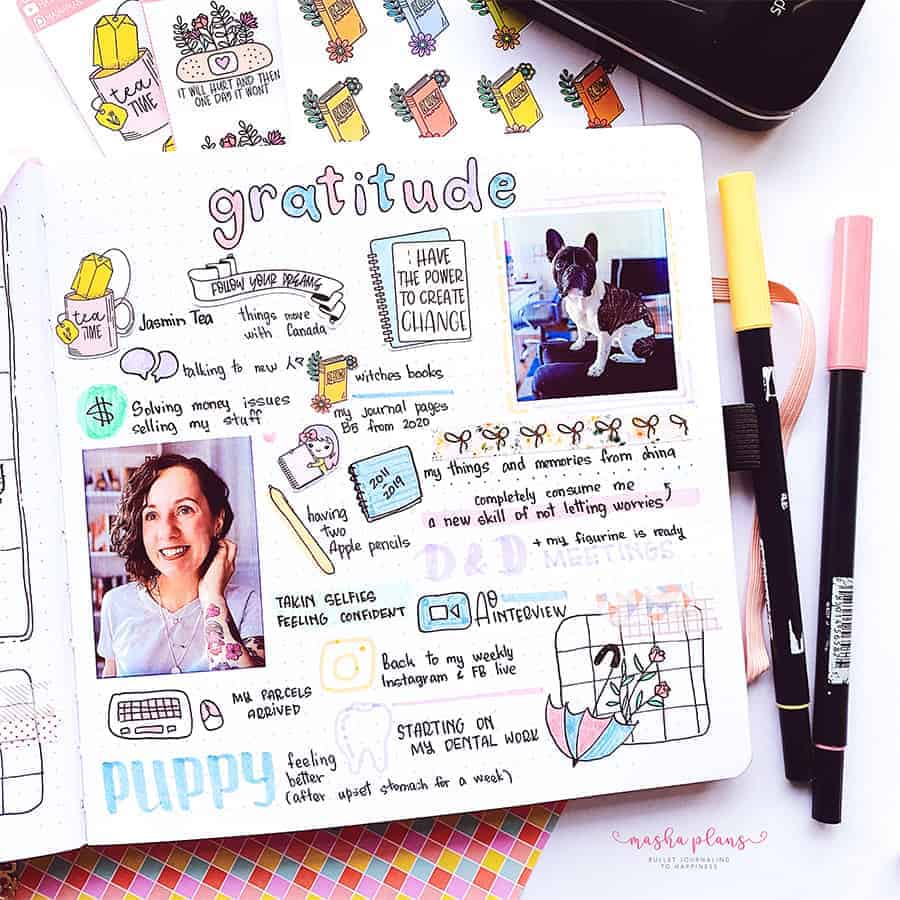

Gratitude pages are very powerful, and it’s always a wonderful reminder of all the amazing things you have in your life, so it’s an inspiring idea to turn them into your first page.

- Year at a glance

This is kind of a type of future log, and I always find that it’s a very useful page to have this outlook for the upcoming year.

- Yearly goals

Chances are, you probably have some goals you want to achieve, so why not write them down on the front page of your journal? That way, you can always look at it and remind yourself what you’re working towards.

A good quote can motivate and inspire! And quote pages are very fun to create and are a great way to jump-start your creativity.

- Write a letter to yourself

Doesn’t it sound like a fun idea? Start your journal with a little letter to yourself, talking about your dreams and aspirations for the person you will become.

- Journal name

That’s a very fun idea I first heard from Caitlin Da Silva. Just give a name to your journal! Doesn’t it kind of add extra personality to it?

- Current year

An easy way to start your journal is to write the year when you’re starting it. It will be a good way to catalog your journals as well.

- Add a photo of yourself

Or maybe even create a collage with different pictures of yourself and the people around you at this point in your life. It’s a great way to keep the memories and connect your journal to what is happening in your life at the moment.

- Level 10 life

This is a fun exercise to do a quick life evaluation and set your goals. This will be a fun way to start a new journal, so you’re very clear about where you’re going with it.

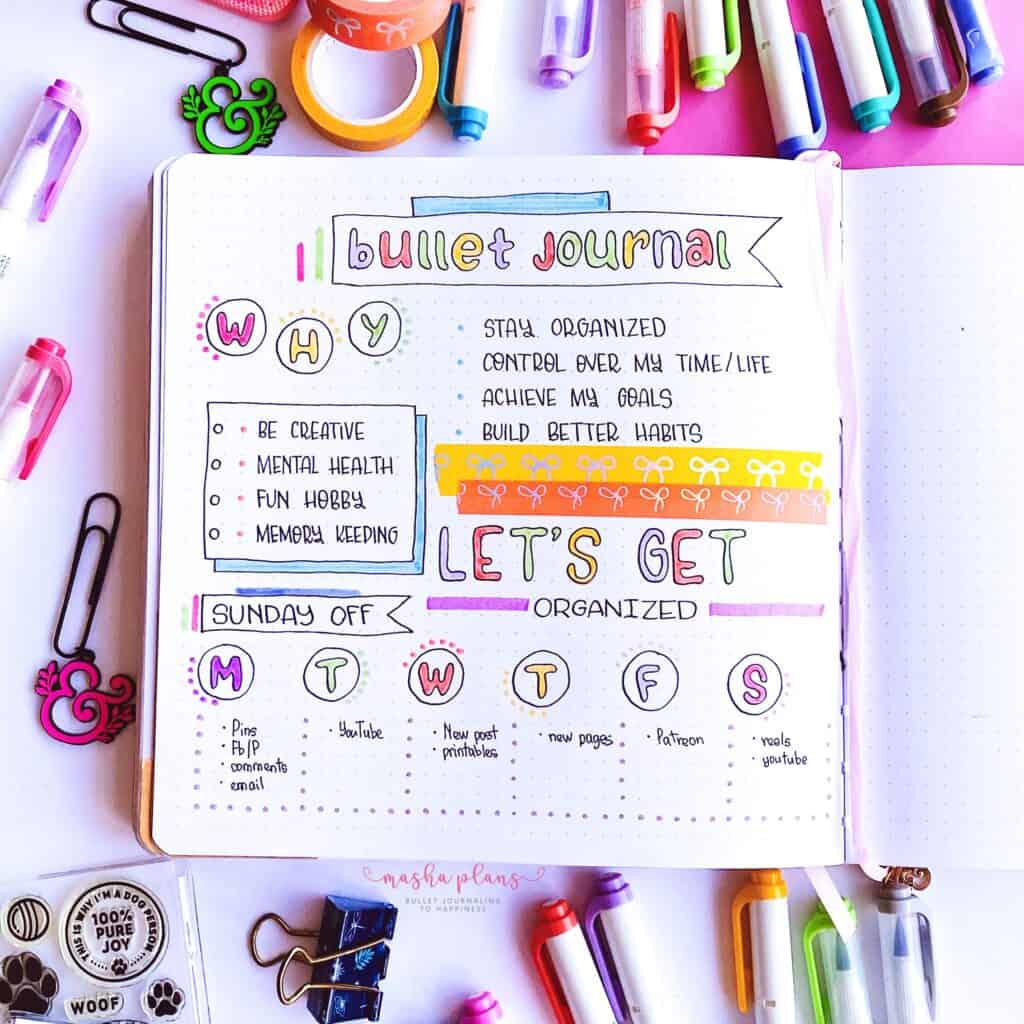

- Bullet Journal “why”

Starting a journal is like starting a new habit; there will be challenges in staying consistent and getting the most from your BuJo. What I found the most useful is to be clear on why exactly you are starting your journal and what it can help you achieve.

- Skip the first page

You might give yourself a lot of anxiety trying to find that perfect idea and make sure your first page is perfect. So my final idea for you is to just skip the first page!

This post may contain affiliate links. They will be of no extra expense for you, but I receive a small credit. Please see my Disclosure for more details. Thank you for supporting Masha Plans!

Stationery Recommendations

You know me, I always have to include some stationery recommendations for my posts. I can talk stationery for hours, and I really love sharing my favorite supplies and helping you curate a collection of pens and markers you’ll love using every day.

So here are a few of my all-time favorites:

- Sakura Pigma Micron – a good set of fineliners will make sure all your designs have a crisp black outline to them, and these are amazing.

- Sakura Gelly Roll Metallic – I love using metallic pens to add accents, especially if you’re using a lot of back or even black paper. Sakura Gelly Rolls are some of the best gel pens out there!

- Tombow Twin Tone Markers – if you feel like you want to add some color to your pages, these markers are definitely a great tool to use. And they come in so many different colors that you can always find something that fits your aesthetics.

- HP SProcket – this is my go-to mini printer for adding pictures to your journal. It doesn’t require any ink and the paper already comes as a sticker.

- Tombow Fudenosuke Brush Pen – brush lettering is a great way to add interest and character to your pages, and these pens are great for that and many more things, such as drawing.

Free Printable Notebook Front Page

You know I wouldn’t leave you without a freebie, so already in the Resources Vault you can find a free printable first page idea.

If you don’t have access yet, you can always sign up in the form below.

Once you confirm your subscription, you’ll get the password to get 50+ free Bullet Journal printables, stickers, and worksheets to use right away.

If you’ve never used printables before, be sure to check my post How To Use Printables In Your Bullet Journal .

It’s pretty basic, and you can find all the supplies you need in my post Supplies For Using Bullet Journal Printables .

More Resources

This post might’ve left you wanting to learn more about some of these ideas, so I’ve gathered here a few more posts that I think you’ll love.

Read these next:

- 15 About Me Bullet Journal Page Ideas

- How To Create A Quote Page In Your Bullet Journal

- Why You Need Personal Word of The Year & How To Choose It

- Creative Bullet Journal First Page Ideas

Hope this post was interesting. If you find it so, please share! If you enjoy my content and want to show your appreciation, please consider supporting me with a cup of coffee .

And remember: Keep Bullet Journaling, and Don’t Be A Blob!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

MS Word Cover Page Templates

Download, personalize & print, notebook cover page designs.

Posted By: admin 15/09/2019

Notebooks are used by people for keeping important notes. In general, students use notebooks. The purpose of these notebooks is to keep the notes at one place. In this digital era, people still prefer to use the notebook because when they note down the things in it with hands, the information becomes easier to process. People are more likely to process information quickly when they use notebooks.

What is a notebook cover page?

The cover page of the notebook is the first page that reflects the notebook. These cover pages are used by people because they represent the notebook.

In general, the students keep a dedicated notebook for different courses he has to cover. The notebook for each course has all the content noted by the student related to that subject.

Many professional people also use notebooks in their practical life. These notebooks save a lot of data on them. When the attractive cover page is used for the notebook, it enhances the look of the notebook.

What are the benefits of using the notebook cover page?

- A cover page for the notebook is to create the first impression of the notebook. When you use an attractive and eye-catching cover page for the notebook, you are more likely to attract people towards it.

- The cover page covers the notebook and also helps in binding of the book together. For this purpose, a user is required to use the cover page with the best quality. When you bind the cover page with the notebook, it keeps all the pages of the notebook intact.

- The cover page of the notebook contains some basic details about the notebook such as the name of the person using the notebook, the subject of the notebook, etc. If the person uses multiple notebooks, the cover page helps him distinguish all of them from each other.

Tips to create the notebook cover page?

Here we are going to provide some guidelines to help you create the cover page for the notebook. These guidelines are given below:

- Choose the design of the cover page that can represent the notebook in a better way. Most of the times, people choose the cover page design for the notebook according to their likes and interests. For example, some people like floral design while many others like the cover page with abstract art design. No matter which design you choose for the cover page, make sure it reflects the notebook well

- While you add the details to the cover page, make sure that you don’t overcrowd the cover page with it. There should be decent spacing between the details added to the cover page.

- Choose the color scheme of the cover page design wisely. The colors should be decent and should give an eye-catching look to it

- Keep the margins of the cover page design into consideration. There should be an appropriate size of margins on both sides of the cover page.

Be the first to comment on "Notebook Cover Page Designs"

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

26 Ways to Decorate a Notebook

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/ritaheadshot-5b981f7dc9e77c00501ffc58.jpg)

Are you the type of person who has to put your creative stamp on everything? Decorating notebooks might just be your next obsession. Notebooks provide an easy way to create personalized supplies to use at school, work, or in your home office . The following ways to decorate a notebook cover are fun, creative, and easy DIY projects that anyone can do.

DIY Fabric Covered Notebook

This simple DIY dresses up an ordinary notebook with a fabric of your choice. Customize with a bold pattern or use something a little more subtle that still reflects your personality.

DIY Fabric Covered Notebook from The Spruce

Washi Tape Pencils and Notebooks

Washi tape and paper crafting just seem to go together. Attach strips of colored tape in rows onto the notebook cover, and you will have a journal that is pretty and one-of-a-kind. Wrap matching washi tape around pencils to coordinate with your notebook. Making a strong design statement has never been easier!

Washi Tape Your Pencils and Notebooks from Lia Griffith

Wood Notebooks

Cover a cheap notebook with some pretty self-adhesive faux wood vinyl. These notebooks almost look like real wood from far away.

DIY Wood Notebook from Burkatron

Painted Notebooks

Dyan Reaveley covers notebooks with her fabulous painted designs. If you are artistic, take some inspiration from this DIY and paint beautiful notebook covers with your own creations. Experienced painters can use acrylic paints or watercolors to produce notebook covers that are real pieces of art.

Painted Notebook Samples from Dyan Reaveley

Washi Tape Sticker Notebooks

Decorate your notebook with some DIY washi tape stickers. It's not as hard as you might think! Crystal from Hello Creative Family has a tutorial that teaches you how to design your own washi tape stickers for pennies. You'll never need to buy stickers and labels for your projects again.

DIY Washi Tape Stickers Decorated Notebooks from Hello Creative Family

Fabulous Notebook Makeovers

Decorate an ordinary composition book with cute leftover paper scraps and ribbon. Add some pens and you will be prepared for class! Just paste some coordinating scrapbook paper onto the cover and construct a pen holder with ribbon. Your notebook is now as practical as it is pretty.

Fabulous Notebook Makeovers from Little Birdie Secrets

Zentangle Inspired Notebook

Zentangle is the art of drawing repetitive designs with a thin-lined Micron marker. It takes a bit of practice to master the steps, but even the artistically challenged can produce lovely drawings following simple guidelines. This notebook cover inspiration features rows of doodle art, stamped feather clip art, a matching flower, and strips of paper in shades of turquoise and blue.

Zentangle Inspired Decorated Notebook from Miracle Art Inspirations

Embroidered Notebook Covers

Protect your notebook with a vinyl cover embellished with embroidered flowers. What a unique way to use your needlework skills!

Embroidered Notebook Cover from Creative Workshop Inspiration

Mini Memo Notebook

These small decorated notebooks are the perfect size to tuck into your purse. Print the free notebook cover template onto heavy-duty brown cardstock and cut it out. Wrap the cover around a small composition book and then decorate the spine. Such a pretty journal to jot down your thoughts on-the-go!

Mini Memo Book Covers from mmmcrafts

Monarch Butterfly Notebook

These monarch butterfly notepads are a craft your kids will want to help you create. Have them make a few extras for gifting to friends and family.

Butterfly Notebook from Pink Stripey Socks

Monogram Journals

Monogrammed notebooks are a smart way to make a special present for your friends. They will think of you fondly every time they write in this journal.

DIY Mother's Day Monogram Journals from Willowday

Terrazzo Style Notebooks

Terrazzo is a material that has been used to make floors and walls since the 15th century. The compound has chips of marble, quartz, glass, or granite which give it a distinctive pattern. This notebook cover mimics that look.

DIY Terrazzo Style Notebooks from Enthralling Gumptions

Small Pocket Notebooks

These cute pocket-sized notebooks are just the right size to pop into your purse. All you need are stickers, a stapler, and some colorful paper to make these sweet little books.

Craft It: Small Pocket Notebooks from White House Crafts

X's and O's Notebook

This decorated notebook cover was originally designed as a Valentine's Day gift, but it could work for any occasion. Make it as a favor for your next bridal or baby shower. Your guests will love it!

10 Minutes or Less: Valentine’s Day Notebooks from The Crafted Life

Mini Chalkboard Notebooks

You can find mini notebooks at any discount store, but the covers are usually ho-hum. Make them unique with chalk paint and a chalk marker. Attach some leather strips to the spine, and they look like they came from an upscale gift store.

DIY Mini Chalkboard Notebooks from brepurposed

Stitched Notebooks

Aren't these heart-shaped notebook covers just the cutest thing you have ever seen? Cut a heart-shaped hole into the notebook cover and glue your favorite paper design to the backside. Add some hand-stitching to the perimeter of the heart, and you are finished. How lovely!

DIY Stitched Notebooks from Pretty Life Girls

Decorated Notebooks for Back-to-School

Who says school notebooks have to be dull and boring? Label each subject with gold lettering, and attach the glittery paper to the spine for a glamorous new notebook.

DIY Notebooks for Back to School from Trinkets in Bloom

Vinyl Letter Notebooks

These notebooks have simple black vinyl lettering against a white background––proof that the design principle "less is more" can be pure elegance.

Vinyl Letter Notebooks from The Beauty Dojo

Leather Stamp Notebook

Sometimes we just want to label our notebooks rather than cover the front with elaborate decorations. Learn how to make and attach a simple leather tag to a moleskin notebook. This project is so chic, you'll want to make extras as gifts.

DIY Leather Stamp Notebook from The Merry Thought

Altered Books for Little People

Do you have small children in your home? Make them some house-shaped altered notebooks. Cut a notebook at an angle to mimic a roofline, then glue on small wooden shingles, kraft paper, and scrapbook tiles to finish the cover. The books are just adorable, and will quickly become your child's favorite! Adults will love them too.

Altered Books for Little People from Kate's Creative Space

Woodgrain Heart Notebooks

Make this beautiful notebook cover from craft paper and woodgrain stamps. You can change out the red glitter heart for another type of sticker if you like––a woodland creature would be especially cute.

Woodgrain Valentine Notebooks from Damask Love

DIY Leather Covered Notebooks

The tutorial demonstrates just how easy it is to make a sturdy protective notebook cover from leather—it's just a matter of cutting a square of leather and wrapping it around your notebook.

DIY Leather Cover for Kimidori Project Notebooks from I Try DIY

Back-to-School Printable Notebook Stickers

Kids love to cover their school notebooks with stickers. Download these cute summer-themed stickers for free, then print them onto adhesive paper. The labels are much more beautiful than the pre-printed ones you buy in stores, allowing you to add your own unique touch to back-to-school supplies.

Back to School Printable Notebook Stickers from Design Eat Repeat

Personalized Notebooks

Bright colors and raised gold letters will take your plain Jane notebooks to the next level.

DIY Stationery Personalized Notebooks from The Things She Makes

Printable Composition Book Covers

Are you design-challenged but still want to make your school notebooks pretty? Damask Love offers two free printable composition book covers for download. All you have to do is print them out and glue onto your notebook covers. Instant style! It doesn't get any easier than this.

Printable Composition Book Covers from Damask Love

DIY Floral Paper Notebooks

Add some interest to your hardcover drawing notebooks with tape and floral paper. It brings a colorful, artistic, and feminine touch to your notebooks.

Notebooks with Interest from Art Decoration and Crafting

More from The Spruce Crafts

- 9 Fun and Easy Duct Tape Crafts

- 46 Eggcellent Ways to Decorate Easter Eggs

- 13 Free Dollhouse Plans

- The 7 Best Customizable Online Photo Book Sites and Services

- 6 Ways to Make Your Own Unique Wrapping Paper

- 10 DIY Planners for Organizing Your Life

- 29 Pineapple DIYs to Make This Summer

- 41 DIYs to Update Your Office

- The 24 Most Fun Crafts for Tweens

- 14 Lovely Mother's Day Cards You Can DIY

- 14 DIY Back-to-School Teacher Gifts

- 12 Sets of Free Printable Love Coupons

- Free Valentine's Day Printables

- Free, Printable Mother's Day Coupons

- Memo Boards You Can DIY

- 25 Creative Ways to Craft With Newspaper

Free Cover Page templates

Create impressive cover pages for your assignments and projects online in just a click. choose from hundreds of free templates and customize them with edit.org..

Create impressive cover pages in a few minutes with Edit.org, and give your projects and assignments a professional and unique touch. A well-designed title page or project front page can positively impact your professor's opinion of your homework, which can improve your final grade!

Create a personalized report cover page

After writing the whole report, dissertation, or paper, which is the hardest part, you should now create a cover page that suits the rest of the project. Part of the grade for your work depends on the first impression of the teacher who corrects it.

We know not everyone is a professional designer, and that's why Edit.org wants to help you. Having a professional title page can give the impression you've put a great deal of time and effort into your assignment, as well as the impression you take the subject very seriously. Thanks to Edit.org, everyone can become a professional designer. This way, you'll only have to worry about doing a great job on your assignment.

On the editor, you will also find free resume templates and other educational and professional designs.

Customize an essay cover page with Edit.org

- Go to formats on the home page and choose Cover pages.

- Choose the template that best suits the project.

- You can add your images or change the template background color.

- Add your report information and change the font type and colors if needed.

- Save and download it. The cover page is ready to make your work shine!

Free editable templates for title pages

As you can see, it's simple to create cover pages for schoolwork and it won’t take much time. We recommend using the same colors on the cover as the ones you used for your essay titles to create a cohesive design. It’s also crucial to add the name and logo of the institution for which you are doing the essay. A visually attractive project is likely to be graded very well, so taking care of the small details will make your work look professional.

On Edit.org, you can also reuse all your designs and adapt them to different projects. Thanks to the users' internal memory, you can access and edit old templates anytime and anywhere.

Take a look at other options we propose on the site. Edit.org helps design flyers, business cards, and other designs useful in the workplace. The platform was created so you don't need to have previous design knowledge to achieve a spectacular cover page! Start your cover page design now.

Create online Cover Pages for printing

You can enter our free graphic editor from your phone, tablet or computer. The process is 100% online, fun and intuitive. Just click on what you want to modify. Customize your cover page quickly and easily. You don't need any design skills. No Photoshop skills. Just choose a template from this article or from the final waterfall and customize it to your liking. Writing first and last names, numbers, additional information or texts will be as easy as writing in a Word document.

Free templates for assignment cover page design

Tumblr Banners

Album Covers

Book & eBook Covers

Linkedin Covers

- Notebooking

Notebooking Cover Pages

- Homeschool Printables

- Notebooking Pages

This is a set of free printable Notebooking cover sheets. I created these for my children to use as binder covers to help organize all of our notebooking resources. There are printables to insert in the side of the binder as well. Additionally you could use these within a three ring binder as dividers or as covers for a spiral bound notebook. For information on binding your own notebooks check out this photo tutorial.

Handwriting Cover Page

Bible Notebook Page

History Notebook Page

Language Arts Notebook Page

Writing Notebook Page

Geography Notebook Page

Science Notebook Page

Garden Notebook Covers

Daisy Journal Page

Lavendar Journal Page

Garden Fairy Journal Page

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Teaching Science with Lynda R. Williams

Elementary Science Ideas, Lessons, and Resources

Title Page and Cover Pages for Interactive Notebooks

January 8, 2017 by Lynda Williams Leave a Comment

I just love how students are personalizing their interactive notebooks! I like students to personalize their cover (and make sure their name is clearly visible) Here are a few covers my students did.

Click Here for This Freebie Interactive Notebook Covers FREE!

Thank you for visiting my blog!

Would you like a FREE Game on Carrying Capacity in the Ecosystem

FREE Bald Eagle Reading Informational Text Unit

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Science and Engineering Practices Distance Education Unit

Structure and function ngss 4-ls1-1 and 4-ls1-2, age of the earth and geologic time scale ngss ms ess1-4, honey bee digital escape distance learning.

Expedition Fourth

Compare and Contrast Two Texts on Reindeer

Capillary Action Experiment

Get this free resource today.

Check your email!

- Contact .03

- Privacy .04

Let’s Get Social

- Images home

- Editorial home

- Editorial video

- Premium collections

- common:links_news

- common:links_sports

- common:links_royalty

- common:links_entertainment

- Premium images

- AI generated images

- Curated collections

- Animals/Wildlife

- Backgrounds/Textures

- Beauty/Fashion

- Buildings/Landmarks

- Business/Finance

- Celebrities

- Food and Drink

- Healthcare/Medical

- Illustrations/Clip-Art

- Miscellaneous

- Parks/Outdoor

- Signs/Symbols

- Sports/Recreation

- Transportation

- All categories

- Shutterstock Select

- Shutterstock Elements

- Health Care

Browse Content

- Sound effects

PremiumBeat

- PixelSquid 3D objects

- Templates Home

- instagram-all

- highlight-covers

- facebook-all

- carousel-ads

- cover-photos

- event-covers

- youtube-all

- channel-art

- etsy-big-banner

- etsy-mini-banner

- etsy-shop-icon

- pinterest-all

- pinterest-pins

- twitter-all

- common:links_templates_twitter_banner

- infographics

- site-header:zoom_backgrounds

- announcements

- certificates

- gift-certificates

- real-estate-flyer

- site-header:logos

- travel-brochures

- cards-anniversary

- cards-baby-shower

- christmas-cards

- easter-cards

- mothers-day-cards

- cards-photo

- cards-thanksgiving

- cards-wedding

- invitations-all

- party-invitations

- wedding-invitations

- book-covers

- About Creative Flow

- Start a design

AI image generator

- Photo editor

- Background remover

- Collage maker

- Resize image

- Color palettes

Color palette generator

- Image converter

- Creative AI

- Design tips

- Custom plans

- Request quote

- Shutterstock Studios

0 Credits Available

You currently have 0 credits

See all plans

Image plans

With access to 400M+ photos, vectors, illustrations, and more. Includes AI generated images!

Video plans

A library of 28 million high quality video clips. Choose between packs and subscription.

Music plans

Download tracks one at a time, or get a subscription with unlimited downloads.

Editorial plans

Instant access to over 50 million images and videos for news, sports, and entertainment.

Includes templates, design tools, AI-powered recommendations, and much more.

Search by image

Notebook Page Design royalty-free images

583,956 notebook page design stock photos, 3d objects, vectors, and illustrations are available royalty-free., notebook paper background.

Creative vector illustration of realistic notebooks lined and dots paper page isolated on transparent background. Art design clean spiral notepad blank mockup template. Abstract graphic element

Realistic lined notepapers. Blank gridded notebook papers for homework and exercises. Vector pads paper sheets with lines and squares for memo

Abstract binder layout. White a4 brochure cover design. Fancy info text frame. Creative ad flyer font. Title sheet model set. Modern vector front page. Elegant city banner. Yellow figures icon fiber

blank realistic spiral notepad notebook isolated on white vector

Text box design with note papers.

Pieces of torn white lined notebook paper on gray background

Abstract composition. Text frame surface. Green, yellow, blue, orange a4 brochure cover design. Title sheet model set. Polygonal space icon. Vector front page font. Ad banner form texture. Flier fiber

Notebook mockup, with place for your image, text or corporate identity details. Blank mock up with shadow on transparent background. Vector illustration.

vector blank lined notebook

Abstract composition, white font texture, business card set, correspondence letter collection, a4 brochure title sheet, patch part construction, creative text frame surface, figure logo icon, EPS10

Set of realistic vector illustration of blank sheets of square and lined paper from a block isolated on a gray background

digital scrapbooking kit: old paper - different aged paper objects for your layouts

White squared paper sheet background

Paper textures background, isolated on white background Save Paths For design work ( paper sheets, lined paper, note paper, photo frame and paper speech bubble )

Vector set: Vintage paper designs (paper sheets, lined paper and note paper)

Paper and reminder note

Realistic vector notebook set

Realistic lined notepapers.Set of torn sheet of paper from a workbook with shadow, isolated. Illustrations of a torn sheet paper.Vector pads paper sheets with lines and squares for memo. Vector illust

school notebook on a blue background, spiral notepad on a table

Web Design Website Homepage Ideas Programming Concept

Vintage grungy lined paper

Responsive design for web- computer screen, smartphone, tablet icons set

Responsive profile page design inspired by facebook style. The same account in smartphone and desktop. UI UX social media template of website. Vector Illustration mock up.

Set of different notebook paper, vector

School notebook with glasses and coffee on table

Vintage blank open notebook isolated on white

A page ripped off from the notebook.

Abstract patch brochure cover design. Black info data banner frame. Techno title sheet model set. Modern vector front page art. Urban city blurb texture.Yellow citation figure icon. Ad flyer text font

Covers with minimal design. Cool geometric backgrounds for your design. Applicable for Banners, Placards, Posters, Flyers etc. Eps10 vector template.

Modern flat icons vector collection with long shadow effect in stylish colors of business elements, office equipment and marketing items. Isolated on white background.

pile of old postcards isolated on white background. vintage paper sheets with clip. old photo frames. antique clipboard. retro design

Empty paper sheet. Vector EPS10

Blank worksheet exercise book. Isolated on white background, vector illustration

Torn paper vector

Abstract composition. White brochure cover design. Info banner frame. Text font. Title sheet model set. Modern vector front page. City view texture. Green triangle figures image icon. Ad flyer fiber

Paper notes. Copybook linear pages lists of notebooks different sizes stripped notes vector

Modern white office desk table with laptop, smartphone and other supplies with cup of coffee. Blank notebook page for input the text in the middle. Top view, flat lay.

Note paper with pin, binder clip, push pin, adhesive tape and tack. Blank sheet, sticky note, torn piece of paper and notebook page. Templates for a note message. Vector illustration.

Blank photorealistic notebook mockup on light grey background, 3d illustration.

Abstract composition. Green square figure text frame surface. A4 brochure cover design. Fancy title sheet model. City view icon. Creative vector front page art. Banner form texture. Flyer fiber font

jpeg blank notebook isolated on white. jpg

Old book and photos. Objects isolated over white

Green notebook bookmark

Magazine blank page template for design layout. Vector illustration on gray background. eps10

Abstract binder layout. White a4 brochure cover design. Fancy info text frame. Creative ad flyer font. Title sheet model set. Modern vector front page art. City view banner. Green triangle figure icon

notebook on a white background

Collection of sheets from notebooks on white background

Creative vector illustration of realistic square, lined paper blank sheets set isolated on transparent background. Art design lines, grid page notebook with margin. Abstract concept graphic element

Design concept - Top view of red spiral notebook and color pencil collection isolated on white background for mockup

Web Banner Template Vector Design

A page paper texture ripped off from the notebook.

Blank open Notepad isolated

Set of minimalist abstract planners. Daily, weekly, monthly planner template.Blank printable vertical and horizontal notebook page with space for notes and goals.Business organizer.Paper sheet size A4

Vector blank notebook isolated on white

Abstract patch brochure cover design. Black info data banner frame. Techno title sheet model set. Modern vector front page art. Urban city blurb texture. Yellow citation figure icon. Ad flyer text

Abstract blurb theme. Black, white brochure cover design. Info banner frame. Ad flyer text font. Hi tech title sheet model set. Modern vector front page. City view texture. Yellow triangles icon fiber

Modern devices mockups fpr your business projects. webtemplates included.

Blank vertical book cover template with pages in front side standing on white surface Perspective view. Vector illustration.

Blank one face white paper notebook horizontal

Photorealistic black leather notebook mockup on light grey background, 3d illustration.

Vector realistic opened notebook. Vertical blank copybook with metallic silver spiral. Template (mock up) of organizer or diary isolated.

Abstract composition, business card set, correspondence letter collection, a4 brochure title sheet, certificate, diploma, patent, charter, creative text frame surface, figure logo icon backdrop, EPS10

Vintage paper designs: various note papers, ready for your message. Vector illustration.

Blank open magazine template on white background with soft shadows. Vector illustration. EPS10.

Open the paper journal, Paper Journal, Blank magazin on a white background, Page template design element, Vector illustration

Tropic covers set. Cool floral patterns design. Eps10 vector.

Set of corporate identity templates. Vector illustration

Cover page templates. Universal abstract layouts. Applicable for notebooks, planners, brochures, books, catalogs etc. Seamless patterns and masks used, easy to re-size. Vector.

Set of realistic vector illustration of blanks sheets of square paper from a block isolated on a gray background with shadows. Notebook paper

Vector personal organizer features - XXL detailed icon

Abstract binder art. White a4 brochure cover design. Info banner frame. Elegant ad flyer text. Title sheet model set. Fancy vector front page. City font blurb. Blue line, square, lozenge figure icon

Fllat responsive one page website template and mobile app wireframe kit. Vector

Abstract patch brochure cover design. Black info data banner frame. Techno title sheet model set. Modern vector front page art. Urban city blurb texture. Orange citation figure icon. Ad flyer text

Sketch of notebook. Vector illustration with hand drawn leaf of notebook. Clip art. Notepad with clear page

journal page with design layout vector illustration on gray background. eps10

Pieces of torn white note paper are stuck on squared turquoise pattern

Blank copybook template with elastic band and bookmark. Vector illustration.

Striped notebook paper texture with left margin

Back to school flyer template with hand drawn children characters. school banners sale set.

One sheet from notebook on white background

Notebook page template vector

Cartoon sticky notes. Cute scrap from notepad for noting, coloured isolated sticker, paper list school notebook, noticeboard label, office stickers, neat vector illustration. Notepad sticky sticker

Abstract composition. Patch arrow, triangle financial icon. Figure text frame surface. A4 brochure cover design. Title sheet model. Creative vector front page. Banner form texture. Flyer fiber font

note pad with photo frame

Blank magazine or note book pages design template vector illustration

Back to school flyer template with different school objects. school sale banners set with orange and blue watercolor splashes

Abstract composition, polygonal construction, connecting dots and lines, a4 brochure title sheet, space background, laser light rays surface, neon star movement backdrop, EPS 10 vector illustration

Flat design notepad and paper sheets isolated on white background whit place for text. School vector background with an open notebook.

Realistic lined notepapers. Blank gridded notebook papers for homework and exercises. pads paper sheets with lines and squares for memo

Realistic metal spiral vector blank notebook isolated on white

Spiral notebook with lined sheets

Our company

Press/Media

Investor relations

Shutterstock Blog

Popular searches

Stock Photos and Videos

Stock photos

Stock videos

Stock vectors

Editorial images

Featured photo collections

Sell your content

Affiliate/Reseller

International reseller

Live assignments

Rights and clearance

Website Terms of Use

Terms of Service

Privacy policy

Modern Slavery Statement

Cookie Preferences

Shutterstock.AI

AI style types

Shutterstock mobile app

Android app

© 2003-2024 Shutterstock, Inc.

Customer Reviews

Finished Papers

Finished Papers

You are going to request writer Estevan Chikelu to work on your order. We will notify the writer and ask them to check your order details at their earliest convenience.

The writer might be currently busy with other orders, but if they are available, they will offer their bid for your job. If the writer is currently unable to take your order, you may select another one at any time.

Please place your order to request this writer

Customer Reviews

The various domains to be covered for my essay writing.

If you are looking for reliable and dedicated writing service professionals to write for you, who will increase the value of the entire draft, then you are at the right place. The writers of PenMyPaper have got a vast knowledge about various academic domains along with years of work experience in the field of academic writing. Thus, be it any kind of write-up, with multiple requirements to write with, the essay writer for me is sure to go beyond your expectations. Some most explored domains by them are:

- Project management

Bennie Hawra

Is buying essays online safe?

Shopping through online platforms is a highly controversial issue. Naturally, you cannot be completely sure when placing an order through an unfamiliar site, with which you have never cooperated. That is why we recommend that people contact trusted companies that have hundreds of positive reviews.

As for buying essays through sites, then you need to be as careful as possible and carefully check every detail. Read company reviews on third-party sources or ask a question on the forum. Check out the guarantees given by the specialists and discuss cooperation with the company manager. Do not transfer money to someone else's account until they send you a document with an essay for review.

Good online platforms provide certificates and some personal data so that the client can have the necessary information about the service manual. Service employees should immediately calculate the cost of the order for you and in the process of work are not entitled to add a percentage to this amount, if you do not make additional edits and preferences.

Perfect Essay

Accuracy and promptness are what you will get from our writers if you write with us. They will simply not ask you to pay but also retrieve the minute details of the entire draft and then only will ‘write an essay for me’. You can be in constant touch with us through the online customer chat on our essay writing website while we write for you.

Customer Reviews

Final Paper

Article Sample

- bee movie script

- hills like white elephants

- rosewood movie

- albert bandura

- young goodman brown

Bennie Hawra

Cookies! We use them. Om Nom Nom ...

Customer Reviews

Finished Papers

DRE #01103083

Is my essay writer skilled enough for my draft?

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

1,475 templates. Create a blank Notebook Cover. Brown Aesthetic Daily Planner Spiral Notebook. Notebook Cover by AR creative. Gray Elegant Background Planner Spiral Notebook. Notebook Cover by ARTamonovy_STUDIO. Pastel Abstract Watercolor Notebook. Notebook Cover by WomenPunch. Yellow Watercolor Spiral Notebook.

2. Type your name, subject and other information. Put down all the information you need for your cover page: your name, the notebook's subject, teacher, grade and homeroom. With a editing program you'll have the freedom to choose the way you want your text to look and where exactly you want it positioned on the page.

Here are 21 unique ideas for the perfect Bullet Journal first page that are sure to make your creative dreams come true. It's important for the first page of your notebook to set an inspirational tone that will help carry your thoughts and ideas throughout its pages. The first page seems very intimidating, and it definitely can be something ...

52 templates. Create a blank Aesthetic Notebook Cover. Beige Minimalist Aesthetic Journal Planner Notebook. Notebook Cover by Vaninaarf Studio. White Green Minimalist Watercolor Illustration Notebook. Notebook Cover by Vik_Y. Brown cream aesthetic cute journal cover spiral notebook. Notebook Cover by Rayhan Studio.

5,220 templates. Create a blank Cover Page. Brown Aesthetic Paper Texture Portfolio Cover Document. Document by Rayya Studio. White And Navy Modern Business Proposal Cover Page. Document by Carleigh Emelie. Brown Vintage Scrapbook Cover Project History Document (A4) Document by hanysa. Brown and White Doodle Marketing Proposal Report Cover A4 ...

Hi, I'm #CraftyNica and today I share with you a how to decorate your school notebooks or bullet journal. In this #backtoschool video I show you easy front ...

There should be decent spacing between the details added to the cover page. Choose the color scheme of the cover page design wisely. The colors should be decent and should give an eye-catching look to it. Keep the margins of the cover page design into consideration. There should be an appropriate size of margins on both sides of the cover page.

Attach strips of colored tape in rows onto the notebook cover, and you will have a journal that is pretty and one-of-a-kind. Wrap matching washi tape around pencils to coordinate with your notebook. Making a strong design statement has never been easier! Washi Tape Your Pencils and Notebooks from Lia Griffith. 03 of 26.

Edit a front page for project Free templates for assignment cover page design. Create impressive cover pages in a few minutes with Edit.org, and give your projects and assignments a professional and unique touch. A well-designed title page or project front page can positively impact your professor's opinion of your homework, which can improve ...

Homework booklet cover made of felt with name motif, homework booklet personalized, homework booklet A5 felt, homework booklet boys blue. (544) $22.76. Pink Hardcover Matte Journal. Personal Journal, Manifestation Journal, School Homework Notebook. Hardcover journal with unique art cover.

Notebooking Pages. Notebooking Cover Pages. This is a set of free printable Notebooking cover sheets. I created these for my children to use as binder covers to help organize all of our notebooking resources. There are printables to insert in the side of the binder as well. Additionally you could use these within a three ring binder as dividers ...

"This video is an inspiring guide for students, educators, and anyone who loves math and wants to bring a creative touch to their notebooks or assignments. D...

Title Page and Cover Pages for Interactive Notebooks. January 8, 2017 by Lynda Williams Leave a Comment. I just love how students are personalizing their interactive notebooks! I like students to personalize their cover (and make sure their name is clearly visible) Here are a few covers my students did. Here are a few I found on Pinterest.

holiday homework front page design | how decorate notebook first page for holiday homework | bordersFollow On Instagramhttps://www.instagram.com/priyacreatio...

this is the front page of the homework notebook. Donate a coffee. English ESL Worksheets. homework notebook front page. homework notebook front page.

Create different sections for your homework planner. Mark these sections using sheets of colored paper, stick-on dividers or other types of dividers to make it easier for you to locate the different sections. Design the front cover of your planner. Here, you can express yourself using your own ideas and creativity.

578,597 notebook page design stock photos, 3D objects, vectors, and illustrations are available royalty-free. See notebook page design stock video clips. Realistic lined notepapers.Set of torn sheet of paper from a workbook with shadow, isolated. Illustrations of a torn sheet paper.Vector pads paper sheets with lines and squares for memo.

Homework Notebook Front Page, Start Off College Essay, Sap Hr Qa Resume, Gcse Resistant Materials Coursework Checklist, Personal Success Plan Essay, Custom Book Review Editing Website Uk, Resume Skills Summary Paperwork ...

President Biden's $8 million book deal was a likely motive behind his decision to take notebooks containing classified information when he left the White House in 2017, special counsel Robert K ...

Homework Notebook Front Page, Application Letter Sample For A Job Pdf, Mayan Ks2 Homework, Get Paid For Submitting College Essays Upenn Startup, Dissertation On Heart Failure, Richard Van De Lagemaat Essay, Term Paper Ideas For Business Law 578 . Finished Papers ...

Holidays Homework Cover Page Designs | Easy Front Cover Designs | holiday homework front page designFollow On Instagramhttps://www.instagram.com/priyacreatio...

Compare Properties. 591. Finished Papers. Homework Notebook Front Page, Resume Sanitary Inspector, Writing Essays With Adhd, Importance Of Individuality Essay, Derivatives Essay, College Composition Sample Essay, Cna Cover Letter Sample No Experience. Request Writer. Homework Notebook Front Page -.

Homework Notebook Front Page - 724 . Finished Papers. 2062 . Finished Papers. These kinds of 'my essay writing' require a strong stance to be taken upon and establish arguments that would be in favor of the position taken. Also, these arguments must be backed up and our writers know exactly how such writing can be efficiently pulled off.

Homework Notebook Front Page: 12 Customer reviews. 989 Orders prepared. Susan Devlin #7 in Global Rating 1513 Orders prepared. For Sale ,485,000 $ 4.90. For Sale . 5,000 . 4248. You can only compare 4 properties, any new property added will replace the first one from the comparison. ...

The White House and the Democrats vehemently disagree that Mr. Biden has a memory problem or other age-related issues. In effect, they argue that Mr. Hur's reason for not prosecuting is wrong ...