The 9 Parts of Speech: Definitions and Examples

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

A part of speech is a term used in traditional grammar for one of the nine main categories into which words are classified according to their functions in sentences , such as nouns or verbs. Also known as word classes , these are the building blocks of grammar.

Parts of Speech

- Word types can be divided into nine parts of speech:

- prepositions

- conjunctions

- articles/determiners

- interjections

- Some words can be considered more than one part of speech, depending on context and usage.

- Interjections can form complete sentences on their own.

Every sentence you write or speak in English includes words that fall into some of the nine parts of speech. These include nouns, pronouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions, articles/determiners, and interjections. (Some sources include only eight parts of speech and leave interjections in their own category.)

Learning the names of the parts of speech probably won't make you witty, healthy, wealthy, or wise. In fact, learning just the names of the parts of speech won't even make you a better writer. However, you will gain a basic understanding of sentence structure and the English language by familiarizing yourself with these labels.

Open and Closed Word Classes

The parts of speech are commonly divided into open classes (nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs) and closed classes (pronouns, prepositions, conjunctions, articles/determiners, and interjections). The idea is that open classes can be altered and added to as language develops and closed classes are pretty much set in stone. For example, new nouns are created every day, but conjunctions never change.

In contemporary linguistics , the label part of speech has generally been discarded in favor of the term word class or syntactic category . These terms make words easier to qualify objectively based on word construction rather than context. Within word classes, there is the lexical or open class and the function or closed class.

The 9 Parts of Speech

Read about each part of speech below and get started practicing identifying each.

Nouns are a person, place, thing, or idea. They can take on a myriad of roles in a sentence, from the subject of it all to the object of an action. They are capitalized when they're the official name of something or someone, called proper nouns in these cases. Examples: pirate, Caribbean, ship, freedom, Captain Jack Sparrow.

Pronouns stand in for nouns in a sentence. They are more generic versions of nouns that refer only to people. Examples: I, you, he, she, it, ours, them, who, which, anybody, ourselves.

Verbs are action words that tell what happens in a sentence. They can also show a sentence subject's state of being ( is , was ). Verbs change form based on tense (present, past) and count distinction (singular or plural). Examples: sing, dance, believes, seemed, finish, eat, drink, be, became

Adjectives describe nouns and pronouns. They specify which one, how much, what kind, and more. Adjectives allow readers and listeners to use their senses to imagine something more clearly. Examples: hot, lazy, funny, unique, bright, beautiful, poor, smooth.

Adverbs describe verbs, adjectives, and even other adverbs. They specify when, where, how, and why something happened and to what extent or how often. Examples: softly, lazily, often, only, hopefully, softly, sometimes.

Preposition

Prepositions show spacial, temporal, and role relations between a noun or pronoun and the other words in a sentence. They come at the start of a prepositional phrase , which contains a preposition and its object. Examples: up, over, against, by, for, into, close to, out of, apart from.

Conjunction

Conjunctions join words, phrases, and clauses in a sentence. There are coordinating, subordinating, and correlative conjunctions. Examples: and, but, or, so, yet, with.

Articles and Determiners

Articles and determiners function like adjectives by modifying nouns, but they are different than adjectives in that they are necessary for a sentence to have proper syntax. Articles and determiners specify and identify nouns, and there are indefinite and definite articles. Examples: articles: a, an, the ; determiners: these, that, those, enough, much, few, which, what.

Some traditional grammars have treated articles as a distinct part of speech. Modern grammars, however, more often include articles in the category of determiners , which identify or quantify a noun. Even though they modify nouns like adjectives, articles are different in that they are essential to the proper syntax of a sentence, just as determiners are necessary to convey the meaning of a sentence, while adjectives are optional.

Interjection

Interjections are expressions that can stand on their own or be contained within sentences. These words and phrases often carry strong emotions and convey reactions. Examples: ah, whoops, ouch, yabba dabba do!

How to Determine the Part of Speech

Only interjections ( Hooray! ) have a habit of standing alone; every other part of speech must be contained within a sentence and some are even required in sentences (nouns and verbs). Other parts of speech come in many varieties and may appear just about anywhere in a sentence.

To know for sure what part of speech a word falls into, look not only at the word itself but also at its meaning, position, and use in a sentence.

For example, in the first sentence below, work functions as a noun; in the second sentence, a verb; and in the third sentence, an adjective:

- The noun work is the thing Bosco shows up for.

- The verb work is the action he must perform.

- The attributive noun [or converted adjective] work modifies the noun permit .

Learning the names and uses of the basic parts of speech is just one way to understand how sentences are constructed.

Dissecting Basic Sentences

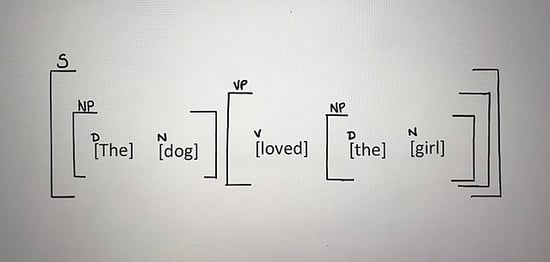

To form a basic complete sentence, you only need two elements: a noun (or pronoun standing in for a noun) and a verb. The noun acts as a subject and the verb, by telling what action the subject is taking, acts as the predicate.

In the short sentence above, birds is the noun and fly is the verb. The sentence makes sense and gets the point across.

You can have a sentence with just one word without breaking any sentence formation rules. The short sentence below is complete because it's a command to an understood "you".

Here, the pronoun, standing in for a noun, is implied and acts as the subject. The sentence is really saying, "(You) go!"

Constructing More Complex Sentences

Use more parts of speech to add additional information about what's happening in a sentence to make it more complex. Take the first sentence from above, for example, and incorporate more information about how and why birds fly.

- Birds fly when migrating before winter.

Birds and fly remain the noun and the verb, but now there is more description.

When is an adverb that modifies the verb fly. The word before is a little tricky because it can be either a conjunction, preposition, or adverb depending on the context. In this case, it's a preposition because it's followed by a noun. This preposition begins an adverbial phrase of time ( before winter ) that answers the question of when the birds migrate . Before is not a conjunction because it does not connect two clauses.

- Sentence Parts and Sentence Structures

- 100 Key Terms Used in the Study of Grammar

- Prepositional Phrases in English Grammar

- The Top 25 Grammatical Terms

- Foundations of Grammar in Italian

- Pronoun Definition and Examples

- What Is an Adverb in English Grammar?

- What Are the Parts of a Prepositional Phrase?

- Definition and Examples of Adjectives

- Definition and Examples of Function Words in English

- Lesson Plan: Label Sentences with Parts of Speech

- Sentence Patterns

- Nominal: Definition and Examples in Grammar

- Constituent: Definition and Examples in Grammar

- Adding Adjectives and Adverbs to the Basic Sentence Unit

- The Difference Between Gerunds, Participles, and Infinitives

- Daily Crossword

- Word Puzzle

- Word Finder

- Word of the Day

- Synonym of the Day

- Word of the Year

- Language stories

- All featured

- Gender and sexuality

- All pop culture

- Grammar Coach ™

- Writing hub

- Grammar essentials

- Commonly confused

- All writing tips

- Pop culture

- Writing tips

- interaction

reciprocal action, effect, or influence.

the direct effect that one kind of particle has on another, in particular, in inducing the emission or absorption of one particle by another.

the mathematical expression that specifies the nature and strength of this effect.

Origin of interaction

Other words from interaction.

- in·ter·ac·tion·al, adjective

Words Nearby interaction

- interacinous

- interactant

- interactionism

- interactive

- interactive engineering

- interactive fiction

- interactive video

Dictionary.com Unabridged Based on the Random House Unabridged Dictionary, © Random House, Inc. 2024

How to use interaction in a sentence

Part of the fun of going out to eat is the interaction , even at a distance, with staff.

In addition, the league is seeking to limit social interactions for teams on the road.

Board meetings are quickly increasing in their significance to foster consistent and vital interactions as an organization.

Pandemics are as much a product of human behavior as they are of biology, because a virus spreads via social interaction .

You find them, run and hide, though there is more interaction between monster and player in comparison to the first game.

After four or five months of casual interaction , they realized they both had lost a young parent to cancer.

Sometimes everything wrong with a larger dynamic is captured in one small interaction .

Otherwise, we morally erode the environment to be the type that makes interaction with others so difficult in the first place.

I think the first obvious thing we can do is videotape every police interaction —body cams, in-car cameras—you name it.

Still, after nearly a month at sea, I imagine they are eager to recharge, ready for interaction with the outside world.

Metaphysicians have argued endlessly as to the interaction of mind and matter.

Discusses the interaction between physical and mental things, and the possibility of freedom in a world of fixed causes.

The student of human progress is likely to be increasingly impressed with the interaction between ideas and institutions.

Thus, here also each element reinforces every other; all the factors of life are in constant interaction .

We see this complex process of the interaction of language and thought actually taking place under our eyes.

British Dictionary definitions for interaction

/ ( ˌɪntərˈækʃən ) /

a mutual or reciprocal action or influence

physics the transfer of energy between elementary particles, between a particle and a field, or between fields : See strong interaction , electromagnetic interaction , fundamental interaction , gravitational interaction , weak interaction , electroweak interaction

Derived forms of interaction

- interactional , adjective

Collins English Dictionary - Complete & Unabridged 2012 Digital Edition © William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1979, 1986 © HarperCollins Publishers 1998, 2000, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2012

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, understanding the 8 parts of speech: definitions and examples.

General Education

If you’re trying to learn the grammatical rules of English, you’ve probably been asked to learn the parts of speech. But what are parts of speech and how many are there? How do you know which words are classified in each part of speech?

The answers to these questions can be a bit complicated—English is a difficult language to learn and understand. Don’t fret, though! We’re going to answer each of these questions for you with a full guide to the parts of speech that explains the following:

- What the parts of speech are, including a comprehensive parts of speech list

- Parts of speech definitions for the individual parts of speech. (If you’re looking for information on a specific part of speech, you can search for it by pressing Command + F, then typing in the part of speech you’re interested in.)

- Parts of speech examples

- A ten question quiz covering parts of speech definitions and parts of speech examples

We’ve got a lot to cover, so let’s begin!

Feature Image: (Gavina S / Wikimedia Commons)

What Are Parts of Speech?

The parts of speech definitions in English can vary, but here’s a widely accepted one: a part of speech is a category of words that serve a similar grammatical purpose in sentences.

To make that definition even simpler, a part of speech is just a category for similar types of words . All of the types of words included under a single part of speech function in similar ways when they’re used properly in sentences.

In the English language, it’s commonly accepted that there are 8 parts of speech: nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, pronouns, conjunctions, interjections, and prepositions. Each of these categories plays a different role in communicating meaning in the English language. Each of the eight parts of speech—which we might also call the “main classes” of speech—also have subclasses. In other words, we can think of each of the eight parts of speech as being general categories for different types within their part of speech . There are different types of nouns, different types of verbs, different types of adjectives, adverbs, pronouns...you get the idea.

And that’s an overview of what a part of speech is! Next, we’ll explain each of the 8 parts of speech—definitions and examples included for each category.

There are tons of nouns in this picture. Can you find them all?

Nouns are a class of words that refer, generally, to people and living creatures, objects, events, ideas, states of being, places, and actions. You’ve probably heard English nouns referred to as “persons, places, or things.” That definition is a little simplistic, though—while nouns do include people, places, and things, “things” is kind of a vague term. I t’s important to recognize that “things” can include physical things—like objects or belongings—and nonphysical, abstract things—like ideas, states of existence, and actions.

Since there are many different types of nouns, we’ll include several examples of nouns used in a sentence while we break down the subclasses of nouns next!

Subclasses of Nouns, Including Examples

As an open class of words, the category of “nouns” has a lot of subclasses. The most common and important subclasses of nouns are common nouns, proper nouns, concrete nouns, abstract nouns, collective nouns, and count and mass nouns. Let’s break down each of these subclasses!

Common Nouns and Proper Nouns

Common nouns are generic nouns—they don’t name specific items. They refer to people (the man, the woman), living creatures (cat, bird), objects (pen, computer, car), events (party, work), ideas (culture, freedom), states of being (beauty, integrity), and places (home, neighborhood, country) in a general way.

Proper nouns are sort of the counterpart to common nouns. Proper nouns refer to specific people, places, events, or ideas. Names are the most obvious example of proper nouns, like in these two examples:

Common noun: What state are you from?

Proper noun: I’m from Arizona .

Whereas “state” is a common noun, Arizona is a proper noun since it refers to a specific state. Whereas “the election” is a common noun, “Election Day” is a proper noun. Another way to pick out proper nouns: the first letter is often capitalized. If you’d capitalize the word in a sentence, it’s almost always a proper noun.

Concrete Nouns and Abstract Nouns

Concrete nouns are nouns that can be identified through the five senses. Concrete nouns include people, living creatures, objects, and places, since these things can be sensed in the physical world. In contrast to concrete nouns, abstract nouns are nouns that identify ideas, qualities, concepts, experiences, or states of being. Abstract nouns cannot be detected by the five senses. Here’s an example of concrete and abstract nouns used in a sentence:

Concrete noun: Could you please fix the weedeater and mow the lawn ?

Abstract noun: Aliyah was delighted to have the freedom to enjoy the art show in peace .

See the difference? A weedeater and the lawn are physical objects or things, and freedom and peace are not physical objects, though they’re “things” people experience! Despite those differences, they all count as nouns.

Collective Nouns, Count Nouns, and Mass Nouns

Nouns are often categorized based on number and amount. Collective nouns are nouns that refer to a group of something—often groups of people or a type of animal. Team , crowd , and herd are all examples of collective nouns.

Count nouns are nouns that can appear in the singular or plural form, can be modified by numbers, and can be described by quantifying determiners (e.g. many, most, more, several). For example, “bug” is a count noun. It can occur in singular form if you say, “There is a bug in the kitchen,” but it can also occur in the plural form if you say, “There are many bugs in the kitchen.” (In the case of the latter, you’d call an exterminator...which is an example of a common noun!) Any noun that can accurately occur in one of these singular or plural forms is a count noun.

Mass nouns are another type of noun that involve numbers and amount. Mass nouns are nouns that usually can’t be pluralized, counted, or quantified and still make sense grammatically. “Charisma” is an example of a mass noun (and an abstract noun!). For example, you could say, “They’ve got charisma, ” which doesn’t imply a specific amount. You couldn’t say, “They’ve got six charismas, ” or, “They’ve got several charismas .” It just doesn’t make sense!

Verbs are all about action...just like these runners.

A verb is a part of speech that, when used in a sentence, communicates an action, an occurrence, or a state of being . In sentences, verbs are the most important part of the predicate, which explains or describes what the subject of the sentence is doing or how they are being. And, guess what? All sentences contain verbs!

There are many words in the English language that are classified as verbs. A few common verbs include the words run, sing, cook, talk, and clean. These words are all verbs because they communicate an action performed by a living being. We’ll look at more specific examples of verbs as we discuss the subclasses of verbs next!

Subclasses of Verbs, Including Examples

Like nouns, verbs have several subclasses. The subclasses of verbs include copular or linking verbs, intransitive verbs, transitive verbs, and ditransitive or double transitive verbs. Let’s dive into these subclasses of verbs!

Copular or Linking Verbs

Copular verbs, or linking verbs, are verbs that link a subject with its complement in a sentence. The most familiar linking verb is probably be. Here’s a list of other common copular verbs in English: act, be, become, feel, grow, seem, smell, and taste.

So how do copular verbs work? Well, in a sentence, if we said, “Michi is ,” and left it at that, it wouldn’t make any sense. “Michi,” the subject, needs to be connected to a complement by the copular verb “is.” Instead, we could say, “Michi is leaving.” In that instance, is links the subject of the sentence to its complement.

Transitive Verbs, Intransitive Verbs, and Ditransitive Verbs

Transitive verbs are verbs that affect or act upon an object. When unattached to an object in a sentence, a transitive verb does not make sense. Here’s an example of a transitive verb attached to (and appearing before) an object in a sentence:

Please take the clothes to the dry cleaners.

In this example, “take” is a transitive verb because it requires an object—”the clothes”—to make sense. “The clothes” are the objects being taken. “Please take” wouldn’t make sense by itself, would it? That’s because the transitive verb “take,” like all transitive verbs, transfers its action onto another being or object.

Conversely, intransitive verbs don’t require an object to act upon in order to make sense in a sentence. These verbs make sense all on their own! For instance, “They ran ,” “We arrived ,” and, “The car stopped ” are all examples of sentences that contain intransitive verbs.

Finally, ditransitive verbs, or double transitive verbs, are a bit more complicated. Ditransitive verbs are verbs that are followed by two objects in a sentence . One of the objects has the action of the ditransitive verb done to it, and the other object has the action of the ditransitive verb directed towards it. Here’s an example of what that means in a sentence:

I cooked Nathan a meal.

In this example, “cooked” is a ditransitive verb because it modifies two objects: Nathan and meal . The meal has the action of “cooked” done to it, and “Nathan” has the action of the verb directed towards him.

Adjectives are descriptors that help us better understand a sentence. A common adjective type is color.

#3: Adjectives

Here’s the simplest definition of adjectives: adjectives are words that describe other words . Specifically, adjectives modify nouns and noun phrases. In sentences, adjectives appear before nouns and pronouns (they have to appear before the words they describe!).

Adjectives give more detail to nouns and pronouns by describing how a noun looks, smells, tastes, sounds, or feels, or its state of being or existence. . For example, you could say, “The girl rode her bike.” That sentence doesn’t have any adjectives in it, but you could add an adjective before both of the nouns in the sentence—”girl” and “bike”—to give more detail to the sentence. It might read like this: “The young girl rode her red bike.” You can pick out adjectives in a sentence by asking the following questions:

- Which one?

- What kind?

- How many?

- Whose’s?

We’ll look at more examples of adjectives as we explore the subclasses of adjectives next!

Subclasses of Adjectives, Including Examples

Subclasses of adjectives include adjective phrases, comparative adjectives, superlative adjectives, and determiners (which include articles, possessive adjectives, and demonstratives).

Adjective Phrases

An adjective phrase is a group of words that describe a noun or noun phrase in a sentence. Adjective phrases can appear before the noun or noun phrase in a sentence, like in this example:

The extremely fragile vase somehow did not break during the move.

In this case, extremely fragile describes the vase. On the other hand, adjective phrases can appear after the noun or noun phrase in a sentence as well:

The museum was somewhat boring.

Again, the phrase somewhat boring describes the museum. The takeaway is this: adjective phrases describe the subject of a sentence with greater detail than an individual adjective.

Comparative Adjectives and Superlative Adjectives

Comparative adjectives are used in sentences where two nouns are compared. They function to compare the differences between the two nouns that they modify. In sentences, comparative adjectives often appear in this pattern and typically end with -er. If we were to describe how comparative adjectives function as a formula, it might look something like this:

Noun (subject) + verb + comparative adjective + than + noun (object).

Here’s an example of how a comparative adjective would work in that type of sentence:

The horse was faster than the dog.

The adjective faster compares the speed of the horse to the speed of the dog. Other common comparative adjectives include words that compare distance ( higher, lower, farther ), age ( younger, older ), size and dimensions ( bigger, smaller, wider, taller, shorter ), and quality or feeling ( better, cleaner, happier, angrier ).

Superlative adjectives are adjectives that describe the extremes of a quality that applies to a subject being compared to a group of objects . Put more simply, superlative adjectives help show how extreme something is. In sentences, superlative adjectives usually appear in this structure and end in -est :

Noun (subject) + verb + the + superlative adjective + noun (object).

Here’s an example of a superlative adjective that appears in that type of sentence:

Their story was the funniest story.

In this example, the subject— story —is being compared to a group of objects—other stories. The superlative adjective “funniest” implies that this particular story is the funniest out of all the stories ever, period. Other common superlative adjectives are best, worst, craziest, and happiest... though there are many more than that!

It’s also important to know that you can often omit the object from the end of the sentence when using superlative adjectives, like this: “Their story was the funniest.” We still know that “their story” is being compared to other stories without the object at the end of the sentence.

Determiners

The last subclass of adjectives we want to look at are determiners. Determiners are words that determine what kind of reference a noun or noun phrase makes. These words are placed in front of nouns to make it clear what the noun is referring to. Determiners are an example of a part of speech subclass that contains a lot of subclasses of its own. Here is a list of the different types of determiners:

- Definite article: the

- Indefinite articles : a, an

- Demonstratives: this, that, these, those

- Pronouns and possessive determiners: my, your, his, her, its, our, their

- Quantifiers : a little, a few, many, much, most, some, any, enough

- Numbers: one, twenty, fifty

- Distributives: all, both, half, either, neither, each, every

- Difference words : other, another

- Pre-determiners: such, what, rather, quite

Here are some examples of how determiners can be used in sentences:

Definite article: Get in the car.

Demonstrative: Could you hand me that magazine?

Possessive determiner: Please put away your clothes.

Distributive: He ate all of the pie.

Though some of the words above might not seem descriptive, they actually do describe the specificity and definiteness, relationship, and quantity or amount of a noun or noun phrase. For example, the definite article “the” (a type of determiner) indicates that a noun refers to a specific thing or entity. The indefinite article “an,” on the other hand, indicates that a noun refers to a nonspecific entity.

One quick note, since English is always more complicated than it seems: while articles are most commonly classified as adjectives, they can also function as adverbs in specific situations, too. Not only that, some people are taught that determiners are their own part of speech...which means that some people are taught there are 9 parts of speech instead of 8!

It can be a little confusing, which is why we have a whole article explaining how articles function as a part of speech to help clear things up .

Adverbs can be used to answer questions like "when?" and "how long?"

Adverbs are words that modify verbs, adjectives (including determiners), clauses, prepositions, and sentences. Adverbs typically answer the questions how?, in what way?, when?, where?, and to what extent? In answering these questions, adverbs function to express frequency, degree, manner, time, place, and level of certainty . Adverbs can answer these questions in the form of single words, or in the form of adverbial phrases or adverbial clauses.

Adverbs are commonly known for being words that end in -ly, but there’s actually a bit more to adverbs than that, which we’ll dive into while we look at the subclasses of adverbs!

Subclasses Of Adverbs, Including Examples

There are many types of adverbs, but the main subclasses we’ll look at are conjunctive adverbs, and adverbs of place, time, manner, degree, and frequency.

Conjunctive Adverbs

Conjunctive adverbs look like coordinating conjunctions (which we’ll talk about later!), but they are actually their own category: conjunctive adverbs are words that connect independent clauses into a single sentence . These adverbs appear after a semicolon and before a comma in sentences, like in these two examples:

She was exhausted; nevertheless , she went for a five mile run.

They didn’t call; instead , they texted.

Though conjunctive adverbs are frequently used to create shorter sentences using a semicolon and comma, they can also appear at the beginning of sentences, like this:

He chopped the vegetables. Meanwhile, I boiled the pasta.

One thing to keep in mind is that conjunctive adverbs come with a comma. When you use them, be sure to include a comma afterward!

There are a lot of conjunctive adverbs, but some common ones include also, anyway, besides, finally, further, however, indeed, instead, meanwhile, nevertheless, next, nonetheless, now, otherwise, similarly, then, therefore, and thus.

Adverbs of Place, Time, Manner, Degree, and Frequency

There are also adverbs of place, time, manner, degree, and frequency. Each of these types of adverbs express a different kind of meaning.

Adverbs of place express where an action is done or where an event occurs. These are used after the verb, direct object, or at the end of a sentence. A sentence like “She walked outside to watch the sunset” uses outside as an adverb of place.

Adverbs of time explain when something happens. These adverbs are used at the beginning or at the end of sentences. In a sentence like “The game should be over soon,” soon functions as an adverb of time.

Adverbs of manner describe the way in which something is done or how something happens. These are the adverbs that usually end in the familiar -ly. If we were to write “She quickly finished her homework,” quickly is an adverb of manner.

Adverbs of degree tell us the extent to which something happens or occurs. If we were to say “The play was quite interesting,” quite tells us the extent of how interesting the play was. Thus, quite is an adverb of degree.

Finally, adverbs of frequency express how often something happens . In a sentence like “They never know what to do with themselves,” never is an adverb of frequency.

Five subclasses of adverbs is a lot, so we’ve organized the words that fall under each category in a nifty table for you here:

It’s important to know about these subclasses of adverbs because many of them don’t follow the old adage that adverbs end in -ly.

Here's a helpful list of pronouns. (Attanata / Flickr )

#5: Pronouns

Pronouns are words that can be substituted for a noun or noun phrase in a sentence . Pronouns function to make sentences less clunky by allowing people to avoid repeating nouns over and over. For example, if you were telling someone a story about your friend Destiny, you wouldn’t keep repeating their name over and over again every time you referred to them. Instead, you’d use a pronoun—like they or them—to refer to Destiny throughout the story.

Pronouns are typically short words, often only two or three letters long. The most familiar pronouns in the English language are they, she, and he. But these aren’t the only pronouns. There are many more pronouns in English that fall under different subclasses!

Subclasses of Pronouns, Including Examples

There are many subclasses of pronouns, but the most commonly used subclasses are personal pronouns, possessive pronouns, demonstrative pronouns, indefinite pronouns, and interrogative pronouns.

Personal Pronouns

Personal pronouns are probably the most familiar type of pronoun. Personal pronouns include I, me, you, she, her, him, he, we, us, they, and them. These are called personal pronouns because they refer to a person! Personal pronouns can replace specific nouns in sentences, like a person’s name, or refer to specific groups of people, like in these examples:

Did you see Gia pole vault at the track meet? Her form was incredible!

The Cycling Club is meeting up at six. They said they would be at the park.

In both of the examples above, a pronoun stands in for a proper noun to avoid repetitiveness. Her replaces Gia in the first example, and they replaces the Cycling Club in the second example.

(It’s also worth noting that personal pronouns are one of the easiest ways to determine what point of view a writer is using.)

Possessive Pronouns

Possessive pronouns are used to indicate that something belongs to or is the possession of someone. The possessive pronouns fall into two categories: limiting and absolute. In a sentence, absolute possessive pronouns can be substituted for the thing that belongs to a person, and limiting pronouns cannot.

The limiting pronouns are my, your, its, his, her, our, their, and whose, and the absolute pronouns are mine, yours, his, hers, ours, and theirs . Here are examples of a limiting possessive pronoun and absolute possessive pronoun used in a sentence:

Limiting possessive pronoun: Juan is fixing his car.

In the example above, the car belongs to Juan, and his is the limiting possessive pronoun that shows the car belongs to Juan. Now, here’s an example of an absolute pronoun in a sentence:

Absolute possessive pronoun: Did you buy your tickets ? We already bought ours .

In this example, the tickets belong to whoever we is, and in the second sentence, ours is the absolute possessive pronoun standing in for the thing that “we” possess—the tickets.

Demonstrative Pronouns, Interrogative Pronouns, and Indefinite Pronouns

Demonstrative pronouns include the words that, this, these, and those. These pronouns stand in for a noun or noun phrase that has already been mentioned in a sentence or conversation. This and these are typically used to refer to objects or entities that are nearby distance-wise, and that and those usually refer to objects or entities that are farther away. Here’s an example of a demonstrative pronoun used in a sentence:

The books are stacked up in the garage. Can you put those away?

The books have already been mentioned, and those is the demonstrative pronoun that stands in to refer to them in the second sentence above. The use of those indicates that the books aren’t nearby—they’re out in the garage. Here’s another example:

Do you need shoes? Here...you can borrow these.

In this sentence, these refers to the noun shoes. Using the word these tells readers that the shoes are nearby...maybe even on the speaker’s feet!

Indefinite pronouns are used when it isn’t necessary to identify a specific person or thing . The indefinite pronouns are one, other, none, some, anybody, everybody, and no one. Here’s one example of an indefinite pronoun used in a sentence:

Promise you can keep a secret?

Of course. I won’t tell anyone.

In this example, the person speaking in the second two sentences isn’t referring to any particular people who they won’t tell the secret to. They’re saying that, in general, they won’t tell anyone . That doesn’t specify a specific number, type, or category of people who they won’t tell the secret to, which is what makes the pronoun indefinite.

Finally, interrogative pronouns are used in questions, and these pronouns include who, what, which, and whose. These pronouns are simply used to gather information about specific nouns—persons, places, and ideas. Let’s look at two examples of interrogative pronouns used in sentences:

Do you remember which glass was mine?

What time are they arriving?

In the first glass, the speaker wants to know more about which glass belongs to whom. In the second sentence, the speaker is asking for more clarity about a specific time.

Conjunctions hook phrases and clauses together so they fit like pieces of a puzzle.

#6: Conjunctions

Conjunctions are words that are used to connect words, phrases, clauses, and sentences in the English language. This function allows conjunctions to connect actions, ideas, and thoughts as well. Conjunctions are also used to make lists within sentences. (Conjunctions are also probably the most famous part of speech, since they were immortalized in the famous “Conjunction Junction” song from Schoolhouse Rock .)

You’re probably familiar with and, but, and or as conjunctions, but let’s look into some subclasses of conjunctions so you can learn about the array of conjunctions that are out there!

Subclasses of Conjunctions, Including Examples

Coordinating conjunctions, subordinating conjunctions, and correlative conjunctions are three subclasses of conjunctions. Each of these types of conjunctions functions in a different way in sentences!

Coordinating Conjunctions

Coordinating conjunctions are probably the most familiar type of conjunction. These conjunctions include the words for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so (people often recommend using the acronym FANBOYS to remember the seven coordinating conjunctions!).

Coordinating conjunctions are responsible for connecting two independent clauses in sentences, but can also be used to connect two words in a sentence. Here are two examples of coordinating conjunctions that connect two independent clauses in a sentence:

He wanted to go to the movies, but he couldn’t find his car keys.

They put on sunscreen, and they went to the beach.

Next, here are two examples of coordinating conjunctions that connect two words:

Would you like to cook or order in for dinner?

The storm was loud yet refreshing.

The two examples above show that coordinating conjunctions can connect different types of words as well. In the first example, the coordinating conjunction “or” connects two verbs; in the second example, the coordinating conjunction “yet” connects two adjectives.

But wait! Why does the first set of sentences have commas while the second set of sentences doesn’t? When using a coordinating conjunction, put a comma before the conjunction when it’s connecting two complete sentences . Otherwise, there’s no comma necessary.

Subordinating Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunctions are used to link an independent clause to a dependent clause in a sentence. This type of conjunction always appears at the beginning of a dependent clause, which means that subordinating conjunctions can appear at the beginning of a sentence or in the middle of a sentence following an independent clause. (If you’re unsure about what independent and dependent clauses are, be sure to check out our guide to compound sentences.)

Here is an example of a subordinating conjunction that appears at the beginning of a sentence:

Because we were hungry, we ordered way too much food.

Now, here’s an example of a subordinating conjunction that appears in the middle of a sentence, following an independent clause and a comma:

Rakim was scared after the power went out.

See? In the example above, the subordinating conjunction after connects the independent clause Rakim was scared to the dependent clause after the power went out. Subordinating conjunctions include (but are not limited to!) the following words: after, as, because, before, even though, one, since, unless, until, whenever, and while.

Correlative Conjunctions

Finally, correlative conjunctions are conjunctions that come in pairs, like both/and, either/or, and neither/nor. The two correlative conjunctions that come in a pair must appear in different parts of a sentence to make sense— they correlate the meaning in one part of the sentence with the meaning in another part of the sentence . Makes sense, right?

Here are two examples of correlative conjunctions used in a sentence:

We’re either going to the Farmer’s Market or the Natural Grocer’s for our shopping today.

They’re going to have to get dog treats for both Piper and Fudge.

Other pairs of correlative conjunctions include as many/as, not/but, not only/but also, rather/than, such/that, and whether/or.

Interjections are single words that express emotions that end in an exclamation point. Cool!

#7: Interjections

Interjections are words that often appear at the beginning of sentences or between sentences to express emotions or sentiments such as excitement, surprise, joy, disgust, anger, or even pain. Commonly used interjections include wow!, yikes!, ouch!, or ugh! One clue that an interjection is being used is when an exclamation point appears after a single word (but interjections don’t have to be followed by an exclamation point). And, since interjections usually express emotion or feeling, they’re often referred to as being exclamatory. Wow!

Interjections don’t come together with other parts of speech to form bigger grammatical units, like phrases or clauses. There also aren’t strict rules about where interjections should appear in relation to other sentences . While it’s common for interjections to appear before sentences that describe an action or event that the interjection helps explain, interjections can appear after sentences that contain the action they’re describing as well.

Subclasses of Interjections, Including Examples

There are two main subclasses of interjections: primary interjections and secondary interjections. Let’s take a look at these two types of interjections!

Primary Interjections

Primary interjections are single words, like oh!, wow!, or ouch! that don’t enter into the actual structure of a sentence but add to the meaning of a sentence. Here’s an example of how a primary interjection can be used before a sentence to add to the meaning of the sentence that follows it:

Ouch ! I just burned myself on that pan!

While someone who hears, I just burned myself on that pan might assume that the person who said that is now in pain, the interjection Ouch! makes it clear that burning oneself on the pan definitely was painful.

Secondary Interjections

Secondary interjections are words that have other meanings but have evolved to be used like interjections in the English language and are often exclamatory. Secondary interjections can be mixed with greetings, oaths, or swear words. In many cases, the use of secondary interjections negates the original meaning of the word that is being used as an interjection. Let’s look at a couple of examples of secondary interjections here:

Well , look what the cat dragged in!

Heck, I’d help if I could, but I’ve got to get to work.

You probably know that the words well and heck weren’t originally used as interjections in the English language. Well originally meant that something was done in a good or satisfactory way, or that a person was in good health. Over time and through repeated usage, it’s come to be used as a way to express emotion, such as surprise, anger, relief, or resignation, like in the example above.

This is a handy list of common prepositional phrases. (attanatta / Flickr)

#8: Prepositions

The last part of speech we’re going to define is the preposition. Prepositions are words that are used to connect other words in a sentence—typically nouns and verbs—and show the relationship between those words. Prepositions convey concepts such as comparison, position, place, direction, movement, time, possession, and how an action is completed.

Subclasses of Prepositions, Including Examples

The subclasses of prepositions are simple prepositions, double prepositions, participle prepositions, and prepositional phrases.

Simple Prepositions

Simple prepositions appear before and between nouns, adjectives, or adverbs in sentences to convey relationships between people, living creatures, things, or places . Here are a couple of examples of simple prepositions used in sentences:

I’ll order more ink before we run out.

Your phone was beside your wallet.

In the first example, the preposition before appears between the noun ink and the personal pronoun we to convey a relationship. In the second example, the preposition beside appears between the verb was and the possessive pronoun your.

In both examples, though, the prepositions help us understand how elements in the sentence are related to one another. In the first sentence, we know that the speaker currently has ink but needs more before it’s gone. In the second sentence, the preposition beside helps us understand how the wallet and the phone are positioned relative to one another!

Double Prepositions

Double prepositions are exactly what they sound like: two prepositions joined together into one unit to connect phrases, nouns, and pronouns with other words in a sentence. Common examples of double prepositions include outside of, because of, according to, next to, across from, and on top of. Here is an example of a double preposition in a sentence:

I thought you were sitting across from me.

You see? Across and from both function as prepositions individually. When combined together in a sentence, they create a double preposition. (Also note that the prepositions help us understand how two people— you and I— are positioned with one another through spacial relationship.)

Prepositional Phrases

Finally, prepositional phrases are groups of words that include a preposition and a noun or pronoun. Typically, the noun or pronoun that appears after the preposition in a prepositional phrase is called the object of the preposition. The object always appears at the end of the prepositional phrase. Additionally, prepositional phrases never include a verb or a subject. Here are two examples of prepositional phrases:

The cat sat under the chair .

In the example above, “under” is the preposition, and “the chair” is the noun, which functions as the object of the preposition. Here’s one more example:

We walked through the overgrown field .

Now, this example demonstrates one more thing you need to know about prepositional phrases: they can include an adjective before the object. In this example, “through” is the preposition, and “field” is the object. “Overgrown” is an adjective that modifies “the field,” and it’s quite common for adjectives to appear in prepositional phrases like the one above.

While that might sound confusing, don’t worry: the key is identifying the preposition in the first place! Once you can find the preposition, you can start looking at the words around it to see if it forms a compound preposition, a double preposition of a prepositional phrase.

10 Question Quiz: Test Your Knowledge of Parts of Speech Definitions and Examples

Since we’ve covered a lot of material about the 8 parts of speech with examples ( a lot of them!), we want to give you an opportunity to review and see what you’ve learned! While it might seem easier to just use a parts of speech finder instead of learning all this stuff, our parts of speech quiz can help you continue building your knowledge of the 8 parts of speech and master each one.

Are you ready? Here we go:

1) What are the 8 parts of speech?

a) Noun, article, adverb, antecedent, verb, adjective, conjunction, interjection b) Noun, pronoun, verb, adverb, determiner, clause, adjective, preposition c) Noun, verb, adjective, adverb, pronoun, conjunction, interjection, preposition

2) Which parts of speech have subclasses?

a) Nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs b) Nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, conjunctions, and prepositions c) All of them! There are many types of words within each part of speech.

3) What is the difference between common nouns and proper nouns?

a) Common nouns don’t refer to specific people, places, or entities, but proper nouns do refer to specific people, places, or entities. b) Common nouns refer to regular, everyday people, places, or entities, but proper nouns refer to famous people, places, or entities. c) Common nouns refer to physical entities, like people, places, and objects, but proper nouns refer to nonphysical entities, like feelings, ideas, and experiences.

4) In which of the following sentences is the emboldened word a verb?

a) He was frightened by the horror film . b) He adjusted his expectations after the first plan fell through. c) She walked briskly to get there on time.

5) Which of the following is a correct definition of adjectives, and what other part of speech do adjectives modify?

a) Adjectives are describing words, and they modify nouns and noun phrases. b) Adjectives are describing words, and they modify verbs and adverbs. c) Adjectives are describing words, and they modify nouns, verbs, and adverbs.

6) Which of the following describes the function of adverbs in sentences?

a) Adverbs express frequency, degree, manner, time, place, and level of certainty. b) Adverbs express an action performed by a subject. c) Adverbs describe nouns and noun phrases.

7) Which of the following answers contains a list of personal pronouns?

a) This, that, these, those b) I, you, me, we, he, she, him, her, they, them c) Who, what, which, whose

8) Where do interjections typically appear in a sentence?

a) Interjections can appear at the beginning of or in between sentences. b) Interjections appear at the end of sentences. c) Interjections appear in prepositional phrases.

9) Which of the following sentences contains a prepositional phrase?

a) The dog happily wagged his tail. b) The cow jumped over the moon. c) She glared, angry that he forgot the flowers.

10) Which of the following is an accurate definition of a “part of speech”?

a) A category of words that serve a similar grammatical purpose in sentences. b) A category of words that are of similar length and spelling. c) A category of words that mean the same thing.

So, how did you do? If you got 1C, 2C, 3A, 4B, 5A, 6A, 7B, 8A, 9B, and 10A, you came out on top! There’s a lot to remember where the parts of speech are concerned, and if you’re looking for more practice like our quiz, try looking around for parts of speech games or parts of speech worksheets online!

What’s Next?

You might be brushing up on your grammar so you can ace the verbal portions of the SAT or ACT. Be sure you check out our guides to the grammar you need to know before you tackle those tests! Here’s our expert guide to the grammar rules you need to know for the SAT , and this article teaches you the 14 grammar rules you’ll definitely see on the ACT.

When you have a good handle on parts of speech, it can make writing essays tons easier. Learn how knowing parts of speech can help you get a perfect 12 on the ACT Essay (or an 8/8/8 on the SAT Essay ).

While we’re on the topic of grammar: keep in mind that knowing grammar rules is only part of the battle when it comes to the verbal and written portions of the SAT and ACT. Having a good vocabulary is also important to making the perfect score ! Here are 262 vocabulary words you need to know before you tackle your standardized tests.

Ashley Sufflé Robinson has a Ph.D. in 19th Century English Literature. As a content writer for PrepScholar, Ashley is passionate about giving college-bound students the in-depth information they need to get into the school of their dreams.

Student and Parent Forum

Our new student and parent forum, at ExpertHub.PrepScholar.com , allow you to interact with your peers and the PrepScholar staff. See how other students and parents are navigating high school, college, and the college admissions process. Ask questions; get answers.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

- English Grammar

- Parts of Speech

Parts of Speech - Definition, 8 Types and Examples

In the English language , every word is called a part of speech. The role a word plays in a sentence denotes what part of speech it belongs to. Explore the definition of parts of speech, the different parts of speech and examples in this article.

Table of Contents

Parts of speech definition, different parts of speech with examples.

- Sentences Examples for the 8 Parts of Speech

A Small Exercise to Check Your Understanding of Parts of Speech

Frequently asked questions on parts of speech, what is a part of speech.

Parts of speech are among the first grammar topics we learn when we are in school or when we start our English language learning process. Parts of speech can be defined as words that perform different roles in a sentence. Some parts of speech can perform the functions of other parts of speech too.

- The Oxford Learner’s Dictionary defines parts of speech as “one of the classes into which words are divided according to their grammar, such as noun, verb, adjective, etc.”

- The Cambridge Dictionary also gives a similar definition – “One of the grammatical groups into which words are divided, such as noun, verb, and adjective”.

Parts of speech include nouns, pronouns, verbs, adverbs, adjectives, prepositions, conjunctions and interjections.

8 Parts of Speech Definitions and Examples:

1. Nouns are words that are used to name people, places, animals, ideas and things. Nouns can be classified into two main categories: Common nouns and Proper nouns . Common nouns are generic like ball, car, stick, etc., and proper nouns are more specific like Charles, The White House, The Sun, etc.

Examples of nouns used in sentences:

- She bought a pair of shoes . (thing)

- I have a pet. (animal)

- Is this your book ? (object)

- Many people have a fear of darkness . (ideas/abstract nouns)

- He is my brother . (person)

- This is my school . (place)

Also, explore Singular Nouns and Plural Nouns .

2. Pronouns are words that are used to substitute a noun in a sentence. There are different types of pronouns. Some of them are reflexive pronouns, possessive pronouns , relative pronouns and indefinite pronouns . I, he, she, it, them, his, yours, anyone, nobody, who, etc., are some of the pronouns.

Examples of pronouns used in sentences:

- I reached home at six in the evening. (1st person singular pronoun)

- Did someone see a red bag on the counter? (Indefinite pronoun)

- Is this the boy who won the first prize? (Relative pronoun)

- That is my mom. (Possessive pronoun)

- I hurt myself yesterday when we were playing cricket. (Reflexive pronoun)

3. Verbs are words that denote an action that is being performed by the noun or the subject in a sentence. They are also called action words. Some examples of verbs are read, sit, run, pick, garnish, come, pitch, etc.

Examples of verbs used in sentences:

- She plays cricket every day.

- Darshana and Arul are going to the movies.

- My friends visited me last week.

- Did you have your breakfast?

- My name is Meenakshi Kishore.

4. Adverbs are words that are used to provide more information about verbs, adjectives and other adverbs used in a sentence. There are five main types of adverbs namely, adverbs of manner , adverbs of degree , adverbs of frequency , adverbs of time and adverbs of place . Some examples of adverbs are today, quickly, randomly, early, 10 a.m. etc.

Examples of adverbs used in sentences:

- Did you come here to buy an umbrella? (Adverb of place)

- I did not go to school yesterday as I was sick. (Adverb of time)

- Savio reads the newspaper everyday . (Adverb of frequency)

- Can you please come quickly ? (Adverb of manner)

- Tony was so sleepy that he could hardly keep his eyes open during the meeting. (Adverb of degree)

5. Adjectives are words that are used to describe or provide more information about the noun or the subject in a sentence. Some examples of adjectives include good, ugly, quick, beautiful, late, etc.

Examples of adjectives used in sentences:

- The place we visited yesterday was serene .

- Did you see how big that dog was?

- The weather is pleasant today.

- The red dress you wore on your birthday was lovely.

- My brother had only one chapati for breakfast.

6. Prepositions are words that are used to link one part of the sentence to another. Prepositions show the position of the object or subject in a sentence. Some examples of prepositions are in, out, besides, in front of, below, opposite, etc.

Examples of prepositions used in sentences:

- The teacher asked the students to draw lines on the paper so that they could write in straight lines.

- The child hid his birthday presents under his bed.

- Mom asked me to go to the store near my school.

- The thieves jumped over the wall and escaped before we could reach home.

7. Conjunctions are a part of speech that is used to connect two different parts of a sentence, phrases and clauses . Some examples of conjunctions are and, or, for, yet, although, because, not only, etc.

Examples of conjunctions used in sentences:

- Meera and Jasmine had come to my birthday party.

- Jane did not go to work as she was sick.

- Unless you work hard, you cannot score good marks.

- I have not finished my project, yet I went out with my friends.

8. Interjections are words that are used to convey strong emotions or feelings. Some examples of interjections are oh, wow, alas, yippee, etc. It is always followed by an exclamation mark.

Examples of interjections used in sentences:

- Wow ! What a wonderful work of art.

- Alas ! That is really sad.

- Yippee ! We won the match.

Sentence Examples for the 8 Parts of Speech

- Noun – Tom lives in New York .

- Pronoun – Did she find the book she was looking for?

- Verb – I reached home.

- Adverb – The tea is too hot.

- Adjective – The movie was amazing .

- Preposition – The candle was kept under the table.

- Conjunction – I was at home all day, but I am feeling very tired.

- Interjection – Oh ! I forgot to turn off the stove.

Let us find out if you have understood the different parts of speech and their functions. Try identifying which part of speech the highlighted words belong to.

- My brother came home late .

- I am a good girl.

- This is the book I was looking for.

- Whoa ! This is amazing .

- The climate in Kodaikanal is very pleasant.

- Can you please pick up Dan and me on your way home?

Now, let us see if you got it right. Check your answers.

- My – Pronoun, Home – Noun, Late – Adverb

- Am – Verb, Good – Adjective

- I – Pronoun, Was looking – Verb

- Whoa – Interjection, Amazing – Adjective

- Climate – Noun, In – Preposition, Kodaikanal – Noun, Very – Adverb

- And – Conjunction, On – Preposition, Your – Pronoun

What are parts of speech?

The term ‘parts of speech’ refers to words that perform different functions in a sentence in order to give the sentence a proper meaning and structure.

How many parts of speech are there?

There are 8 parts of speech in total.

What are the 8 parts of speech?

Nouns, pronouns, verbs, adverbs, adjectives, prepositions, conjunctions and interjections are the 8 parts of speech.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

- Share Share

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

3.1: Language and Meaning

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 18449

Learning Objectives

- Explain how the triangle of meaning describes the symbolic nature of language.

- Distinguish between denotation and connotation.

- Discuss the function of the rules of language.

- Describe the process of language acquisition.

The relationship between language and meaning is not a straightforward one. One reason for this complicated relationship is the limitlessness of modern language systems like English (Crystal, 2005). Language is productive in the sense that there are an infinite number of utterances we can make by connecting existing words in new ways. In addition, there is no limit to a language’s vocabulary, as new words are coined daily. Of course, words aren’t the only things we need to communicate, and although verbal and nonverbal communication are closely related in terms of how we make meaning, nonverbal communication is not productive and limitless. Although we can only make a few hundred physical signs, we have about a million words in the English language. So with all this possibility, how does communication generate meaning?

You’ll recall that “generating meaning” was a central part of the definition of communication we learned earlier. We arrive at meaning through the interaction between our nervous and sensory systems and some stimulus outside of them. It is here, between what the communication models we discussed earlier labeled as encoding and decoding, that meaning is generated as sensory information is interpreted. The indirect and sometimes complicated relationship between language and meaning can lead to confusion, frustration, or even humor. We may even experience a little of all three, when we stop to think about how there are some twenty-five definitions available to tell us the meaning of word meaning ! (Crystal, 2005) Since language and symbols are the primary vehicle for our communication, it is important that we not take the components of our verbal communication for granted.

Language Is Symbolic

Our language system is primarily made up of symbols. A symbol is something that stands in for or represents something else. Symbols can be communicated verbally (speaking the word hello ), in writing (putting the letters H-E-L-L-O together), or nonverbally (waving your hand back and forth). In any case, the symbols we use stand in for something else, like a physical object or an idea; they do not actually correspond to the thing being referenced in any direct way. Unlike hieroglyphics in ancient Egypt, which often did have a literal relationship between the written symbol and the object being referenced, the symbols used in modern languages look nothing like the object or idea to which they refer.

The symbols we use combine to form language systems or codes. Codes are culturally agreed on and ever-changing systems of symbols that help us organize, understand, and generate meaning (Leeds-Hurwitz, 1993). There are about 6,000 language codes used in the world, and around 40 percent of those (2,400) are only spoken and do not have a written version (Crystal, 2005). Remember that for most of human history the spoken word and nonverbal communication were the primary means of communication. Even languages with a written component didn’t see widespread literacy, or the ability to read and write, until a little over one hundred years ago.

The symbolic nature of our communication is a quality unique to humans. Since the words we use do not have to correspond directly to a “thing” in our “reality,” we can communicate in abstractions. This property of language is called displacement and specifically refers to our ability to talk about events that are removed in space or time from a speaker and situation (Crystal, 2005). Animals do communicate, but in a much simpler way that is only a reaction to stimulus. Further, animal communication is very limited and lacks the productive quality of language that we discussed earlier.

As I noted in the chapter titled “Introduction to Communication Studies”, the earliest human verbal communication was not very symbolic or abstract, as it likely mimicked sounds of animals and nature. Such a simple form of communication persisted for thousands of years, but as later humans turned to settled agriculture and populations grew, things needed to be more distinguishable. More terms (symbols) were needed to accommodate the increasing number of things like tools and ideas like crop rotation that emerged as a result of new knowledge about and experience with farming and animal domestication. There weren’t written symbols during this time, but objects were often used to represent other objects; for example, a farmer might have kept a pebble in a box to represent each chicken he owned. As further advancements made keeping track of objects-representing-objects more difficult, more abstract symbols and later written words were able to stand in for an idea or object. Despite the fact that these transitions occurred many thousands of years ago, we can trace some words that we still use today back to their much more direct and much less abstract origins.

For example, the word calculate comes from the Latin word calculus , which means “pebble.” But what does a pebble have to do with calculations? Pebbles were used, very long ago, to calculate things before we developed verbal or written numbering systems (Hayakawa & Hayakawa, 1990). As I noted earlier, a farmer may have kept, in a box, one pebble for each of his chickens. Each pebble represented one chicken, meaning that each symbol (the pebble) had a direct correlation to another thing out in the world (its chicken). This system allowed the farmer to keep track of his livestock. He could periodically verify that each pebble had a corresponding chicken. If there was a discrepancy, he would know that a chicken was lost, stolen, or killed. Later, symbols were developed that made accounting a little easier. Instead of keeping track of boxes of pebbles, the farmer could record a symbol like the word five or the numeral 15 that could stand in for five or fifteen pebbles. This demonstrates how our symbols have evolved and how some still carry that ancient history with them, even though we are unaware of it. While this evolution made communication easier in some ways, it also opened up room for misunderstanding, since the relationship between symbols and the objects or ideas they represented became less straightforward. Although the root of calculate means “pebble,” the word calculate today has at least six common definitions.

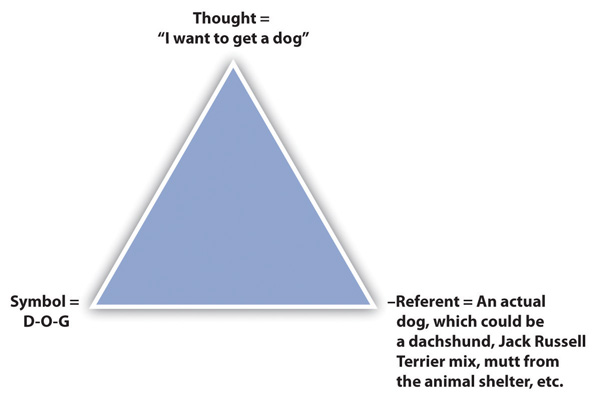

The Triangle of Meaning

The triangle of meaning is a model of communication that indicates the relationship among a thought, symbol, and referent and highlights the indirect relationship between the symbol and referent (Richards & Ogden, 1923). As you can see in Figure 3.1, the thought is the concept or idea a person references. The symbol is the word that represents the thought, and the referent is the object or idea to which the symbol refers. This model is useful for us as communicators because when we are aware of the indirect relationship between symbols and referents, we are aware of how common misunderstandings occur, as the following example illustrates: Jasper and Abby have been thinking about getting a new dog. So each of them is having a similar thought. They are each using the same symbol, the word dog , to communicate about their thought. Their referents, however, are different. Jasper is thinking about a small dog like a dachshund, and Abby is thinking about an Australian shepherd. Since the word dog doesn’t refer to one specific object in our reality, it is possible for them to have the same thought, and use the same symbol, but end up in an awkward moment when they get to the shelter and fall in love with their respective referents only to find out the other person didn’t have the same thing in mind.

Being aware of this indirect relationship between symbol and referent, we can try to compensate for it by getting clarification. Some of what we learned in the chapter titled “Communication and Perception”, about perception checking, can be useful here. Abby might ask Jasper, “What kind of dog do you have in mind?” This question would allow Jasper to describe his referent, which would allow for more shared understanding. If Jasper responds, “Well, I like short-haired dogs. And we need a dog that will work well in an apartment,” then there’s still quite a range of referents. Abby could ask questions for clarification, like “Sounds like you’re saying that a smaller dog might be better. Is that right?” Getting to a place of shared understanding can be difficult, even when we define our symbols and describe our referents.

Definitions

Definitions help us narrow the meaning of particular symbols, which also narrows a symbol’s possible referents. They also provide more words (symbols) for which we must determine a referent. If a concept is abstract and the words used to define it are also abstract, then a definition may be useless. Have you ever been caught in a verbal maze as you look up an unfamiliar word, only to find that the definition contains more unfamiliar words? Although this can be frustrating, definitions do serve a purpose.

Words have denotative and connotative meanings. Denotation refers to definitions that are accepted by the language group as a whole, or the dictionary definition of a word. For example, the denotation of the word cowboy is a man who takes care of cattle. Another denotation is a reckless and/or independent person. A more abstract word, like change , would be more difficult to understand due to the multiple denotations. Since both cowboy and change have multiple meanings, they are considered polysemic words. Monosemic words have only one use in a language, which makes their denotation more straightforward. Specialized academic or scientific words, like monosemic , are often monosemic, but there are fewer commonly used monosemic words, for example, handkerchief . As you might guess based on our discussion of the complexity of language so far, monosemic words are far outnumbered by polysemic words.

Connotation refers to definitions that are based on emotion- or experience-based associations people have with a word. To go back to our previous words, change can have positive or negative connotations depending on a person’s experiences. A person who just ended a long-term relationship may think of change as good or bad depending on what he or she thought about his or her former partner. Even monosemic words like handkerchief that only have one denotation can have multiple connotations. A handkerchief can conjure up thoughts of dainty Southern belles or disgusting snot-rags. A polysemic word like cowboy has many connotations, and philosophers of language have explored how connotations extend beyond one or two experiential or emotional meanings of a word to constitute cultural myths (Barthes, 1972). Cowboy , for example, connects to the frontier and the western history of the United States, which has mythologies associated with it that help shape the narrative of the nation. The Marlboro Man is an enduring advertising icon that draws on connotations of the cowboy to attract customers. While people who grew up with cattle or have family that ranch may have a very specific connotation of the word cowboy based on personal experience, other people’s connotations may be more influenced by popular cultural symbolism like that seen in westerns.

Language Is Learned

As we just learned, the relationship between the symbols that make up our language and their referents is arbitrary, which means they have no meaning until we assign it to them. In order to effectively use a language system, we have to learn, over time, which symbols go with which referents, since we can’t just tell by looking at the symbol. Like me, you probably learned what the word apple meant by looking at the letters A-P-P-L-E and a picture of an apple and having a teacher or caregiver help you sound out the letters until you said the whole word. Over time, we associated that combination of letters with the picture of the red delicious apple and no longer had to sound each letter out. This is a deliberate process that may seem slow in the moment, but as we will see next, our ability to acquire language is actually quite astounding. We didn’t just learn individual words and their meanings, though; we also learned rules of grammar that help us put those words into meaningful sentences.

The Rules of Language

Any language system has to have rules to make it learnable and usable. Grammar refers to the rules that govern how words are used to make phrases and sentences. Someone would likely know what you mean by the question “Where’s the remote control?” But “The control remote where’s?” is likely to be unintelligible or at least confusing (Crystal, 2005). Knowing the rules of grammar is important in order to be able to write and speak to be understood, but knowing these rules isn’t enough to make you an effective communicator. As we will learn later, creativity and play also have a role in effective verbal communication. Even though teachers have long enforced the idea that there are right and wrong ways to write and say words, there really isn’t anything inherently right or wrong about the individual choices we make in our language use. Rather, it is our collective agreement that gives power to the rules that govern language.

Some linguists have viewed the rules of language as fairly rigid and limiting in terms of the possible meanings that we can derive from words and sentences created from within that system (de Saussure, 1974). Others have viewed these rules as more open and flexible, allowing a person to make choices to determine meaning (Eco, 1976). Still others have claimed that there is no real meaning and that possibilities for meaning are limitless (Derrida, 1978). For our purposes in this chapter, we will take the middle perspective, which allows for the possibility of individual choice but still acknowledges that there is a system of rules and logic that guides our decision making.

Looking back to our discussion of connotation, we can see how individuals play a role in how meaning and language are related, since we each bring our own emotional and experiential associations with a word that are often more meaningful than a dictionary definition. In addition, we have quite a bit of room for creativity, play, and resistance with the symbols we use. Have you ever had a secret code with a friend that only you knew? This can allow you to use a code word in a public place to get meaning across to the other person who is “in the know” without anyone else understanding the message. The fact that you can take a word, give it another meaning, have someone else agree on that meaning, and then use the word in your own fashion clearly shows that meaning is in people rather than words. As we will learn later, many slang words developed because people wanted a covert way to talk about certain topics like drugs or sex without outsiders catching on.

Language Acquisition