Customize Your Path

Filters Applied

Customize Your Experience.

Utilize the "Customize Your Path" feature to refine the information displayed in myRESEARCHpath based on your role, project inclusions, sponsor or funding, and management center.

Poster and oral presentations

Need assistance with poster presentations?

Get help with poster presentations.

Contact the Research Navigators:

- Email: [email protected]

Poster and oral presentations are typically delivered to academic colleagues at conferences or congresses. Here are some best practices and resources to help develop the content and visuals for a high-impact poster, and plan and practice memorable oral presentations.

The "Related Resources" on this page can be used to tap into Duke’s hub of templates, guides, and services to support researchers developing their presentations.

The Duke Medical Center Library has tips for things to keep in mind before working through the development of a poster presentation, and the Duke University Libraries' Center for Data and Visualization Sciences recorded a talk on preparing effective academic posters .

- Just like with any other publication, the specifications from the conference should be read and understood – there are often size limits or font requirements to keep in mind.

- A good title is critical for posters since presenters get just a few seconds to attract conference goers who are passing by. Make sure the title briefly and memorably portrays the most interesting or central finding of the work.

- Energy should be focused on a solid abstract, as the poster is simply a blown-up visualization of that summary.

- Less is more in poster design. Rather than shrinking fonts to fit the commentary, the commentary should be shrunk to fit the space on the poster, while retaining a readable font and plenty of white space.

The Thompson Writing Program has great general guidance on oral presentations, summarized throughout this page. There are several training opportunities listed in this page's "Related Resources" that can help researchers at all stages to hone their presentation skills.

- Preparing for an oral presentation will take the majority of a researcher's time. The goal of the talk should be fully understood as typically no more than 3-5 key points will be covered in a presentation; the audience and the time allotted should be carefully considered.

- Consideration of “guideposts” for the audience should be given. It is especially important in oral deliveries that information is organized in to meaningful blocks for the audience. Transitions should be emphasized during the presentation.

- Rather than creating a word-for-word speech, researchers should create a plan for each section, idea or point. By reading written points, delivery can be kept fresh.

- To engage audiences, it is a good idea to make strongest points first, and in a memorable way. While background and introduction sections are common in academic presentations, they are often already known to the audience.

The Duke Medical Center Library has tutorials, best practices for general design, and strategies for a high-impact poster presentations. Bass Connections also provides guidance on poster design.

Some important things to keep in mind are:

- Keeping posters simple and focusing on two things: Strong visualizations and small blocks of supporting text. Remember the audience; they will be standing a few feet away. Make sure the content is visible from afar.

- Follow brand guidelines from Duke or Duke School of Medicine . When representing Duke at a conference, it is best practice to align the presentation with institutional standards, including appropriate logos and color schemes.

- Avoid violating copyright protections. Include only images created specifically for this purpose, or use stock photography provided by Duke or other vendors.

- Visualizing data tells the story. The Center for Data and Visualization Sciences has workshops, consultations and other resources to ensure that graphical representations of data are effective.

- Poster presentations can be designed using a variety of software (PowerPoint, Illustrator, Keynote, Inkscape), and templates. When choosing software or templates, consideration should be given to accessibility and understanding by everyone involved in creating the presentation.

- Contact information, citations and acknowledgements: On posters, key articles may be noted or images needing references included. For oral and poster presentations, key contributors should be recognized. Funding sources should also be mentioned on posters and in oral presentations.

- A link or QR code should be included for supplemental materials, citations, movies, etc.

- Before a poster is printed, someone with fresh eyes should review it! Reprinting posters is costly and can take time. There are many options for printing, some on paper and some on fabric, with production times varying. The Medical Center Library has some local options to suggest.

- Practicing in a space that is similar to the actual presentation is a good idea, and doing so within the allotted time. Finishing early to allow good Q&A is also a good idea.

- Family, trusted friends, or colleagues can be great test audiences, and can provide valuable feedback.

- Preparation and practice should be started early and repeated often.

- If it is an important address, researchers may want to videotape a rehearsal run to review and improve performance.

- If a presentation is being digitized, release or permission forms may be needed. Duke has resources available via Scholarworks.

- Once a poster session or oral presentation has been completed, researchers should be sure to add it to their CV or biosketch.

Preparing oral and poster presentations for conferences

As a PhD student, attending conferences is an exciting part of academic life. Conferences are a chance to share your research findings, learn novel ideas or techniques and travel, whether that is locally, further afield or even internationally. A crucial aspect to conference attending is conveying your research to the wider scientific community, through either a poster or oral presentation.

Preparing your research to present at a conference is a balance. You need to include the same details as you would put in a paper or report, but make it concise to fit reasonably in a poster format, or within a specific talk length, such as 10 minutes. When writing a talk or poster for a specific conference, investigating the style and content of previous years abstracts may help to peg yours at a suitable level. Before you start, check the conference guidelines on oral presentation outlines, poster size, and orientation. Although most conferences allow A0 portrait posters, some are different and it’s advisable to check this before writing.

Preparing your poster

Generally, posters follow a bullet point style divided into four main sections:

- Introduction or Background

- Discussion or Conclusions.

However, there are some other areas of the poster that need attention too.

Firstly, a snappy title is a must. The title must cover the basic outline of the study, yet be intriguing, making the viewer want to read on. The title must be considered during abstract preparation, as whatever you name your abstract will be your poster title. Author names and affiliations sit below the title; the order of this can be important but must be agreed by your research group before poster publication.

The introduction covers the background details of the research involved, using current literature and references. The aims and objectives of the research must be in the introduction, and generally sits well at the end just before the method section to give a sense of flow.

Methods covers obviously what you did to achieve your results. It’s good to be aware of any ethical approval gained for the study, and noting participant numbers, genders and ages, statistical methods used and any chemical in their full unabbreviated names initially, with subsequent references to the ingredients by the standard abbreviations. If the method is tricky to explain, a diagram or photo may help to illustrate, and it is not necessary to repeat the methods in words.

The results section needs to cover all relevant findings. Tables or figures can really help show data, so be imaginative! You’ll need to include statistical p-values to show significances. Finally, the discussion or conclusion section highlights the key findings from your results in punchy language as a ‘take home message’. These need to be clear and concise, covering the exact findings and if possible the relevance of findings to the study and scientific community as a whole.

Oral presentations

For oral presentations the same headings should be followed, with clear simple slides. Keep the number of slides to a minimum to keep the length of the talk on track. A good guideline is around one slide per minute. Set the scene with a clear introduction to the work, indicating the relevance of the study to the general scientific community. Highlight the study aims and objectives, and unlike a poster, you may want to include a hypothesis for further clarity. Diagrams may also help to describe methodology, and helps to keep audience attention as they must listen to you fully to understand the technique.

Results can also be shown on graphs and figures; be careful with tables, as these can appear daunting to the viewer, unless you clearly highlight the numbers or significances of importance to your work. Throughout the results section explain what each experiment or figure means, what is the finding? This will help you lead directly into the conclusions, and you can repeat the key findings already covered in the results, and give a clear take home message to your audience.

And finally...

Whether you’re giving a poster or a talk at a conference, be confident. Who knows your work better than you? This will help you tackle any questions and comments posed, and give you a chance to meet fellow researchers and possible future collaborators. Project your voice, face your audience and above all enjoy yourself!

Dr Caroline Withers

Home Blog Design How to Design a Winning Poster Presentation: Quick Guide with Examples & Templates

How to Design a Winning Poster Presentation: Quick Guide with Examples & Templates

How are research posters like High School science fair projects? Quite similar, in fact.

Both are visual representations of a research project shared with peers, colleagues and academic faculty. But there’s a big difference: it’s all in professionalism and attention to detail. You can be sure that the students that thrived in science fairs are now creating fantastic research posters, but what is that extra element most people miss when designing a poster presentation?

This guide will teach tips and tricks for creating poster presentations for conferences, symposia, and more. Learn in-depth poster structure and design techniques to help create academic posters that have a lasting impact.

Let’s get started.

Table of Contents

- What is a Research Poster?

Why are Poster Presentations important?

Overall dimensions and orientation, separation into columns and sections, scientific, academic, or something else, a handout with supplemental and contact information, cohesiveness, design and readability, storytelling.

- Font Characteristics

- Color Pairing

- Data Visualization Dimensions

- Alignment, Margins, and White Space

Scientific/Academic Conference Poster Presentation

Digital research poster presentations, slidemodel poster presentation templates, how to make a research poster presentation step-by-step, considerations for printing poster presentations, how to present a research poster presentation, final words, what is a research poster .

Research posters are visual overviews of the most relevant information extracted from a research paper or analysis. They are essential communication formats for sharing findings with peers and interested people in the field. Research posters can also effectively present material for other areas besides the sciences and STEM—for example, business and law.

You’ll be creating research posters regularly as an academic researcher, scientist, or grad student. You’ll have to present them at numerous functions and events. For example:

- Conference presentations

- Informational events

- Community centers

The research poster presentation is a comprehensive way to share data, information, and research results. Before the pandemic, the majority of research events were in person. During lockdown and beyond, virtual conferences and summits became the norm. Many researchers now create poster presentations that work in printed and digital formats.

Let’s look at why it’s crucial to spend time creating poster presentations for your research projects, research, analysis, and study papers.

Research posters represent you and your sponsor’s research

Research papers and accompanying poster presentations are potent tools for representation and communication in your field of study. Well-performing poster presentations help scientists, researchers, and analysts grow their careers through grants and sponsorships.

When presenting a poster presentation for a sponsored research project, you’re representing the company that sponsored you. Your professionalism, demeanor, and capacity for creating impactful poster presentations call attention to other interested sponsors, spreading your impact in the field.

Research posters demonstrate expertise and growth

Presenting research posters at conferences, summits, and graduate grading events shows your expertise and knowledge in your field of study. The way your poster presentation looks and delivers, plus your performance while presenting the work, is judged by your viewers regardless of whether it’s an officially judged panel.

Recurring visitors to research conferences and symposia will see you and your poster presentations evolve. Improve your impact by creating a great poster presentation every time by paying attention to detail in the poster design and in your oral presentation. Practice your public speaking skills alongside the design techniques for even more impact.

Poster presentations create and maintain collaborations

Every time you participate in a research poster conference, you create meaningful connections with people in your field, industry or community. Not only do research posters showcase information about current data in different areas, but they also bring people together with similar interests. Countless collaboration projects between different research teams started after discussing poster details during coffee breaks.

An effective research poster template deepens your peer’s understanding of a topic by highlighting research, data, and conclusions. This information can help other researchers and analysts with their work. As a research poster presenter, you’re given the opportunity for both teaching and learning while sharing ideas with peers and colleagues.

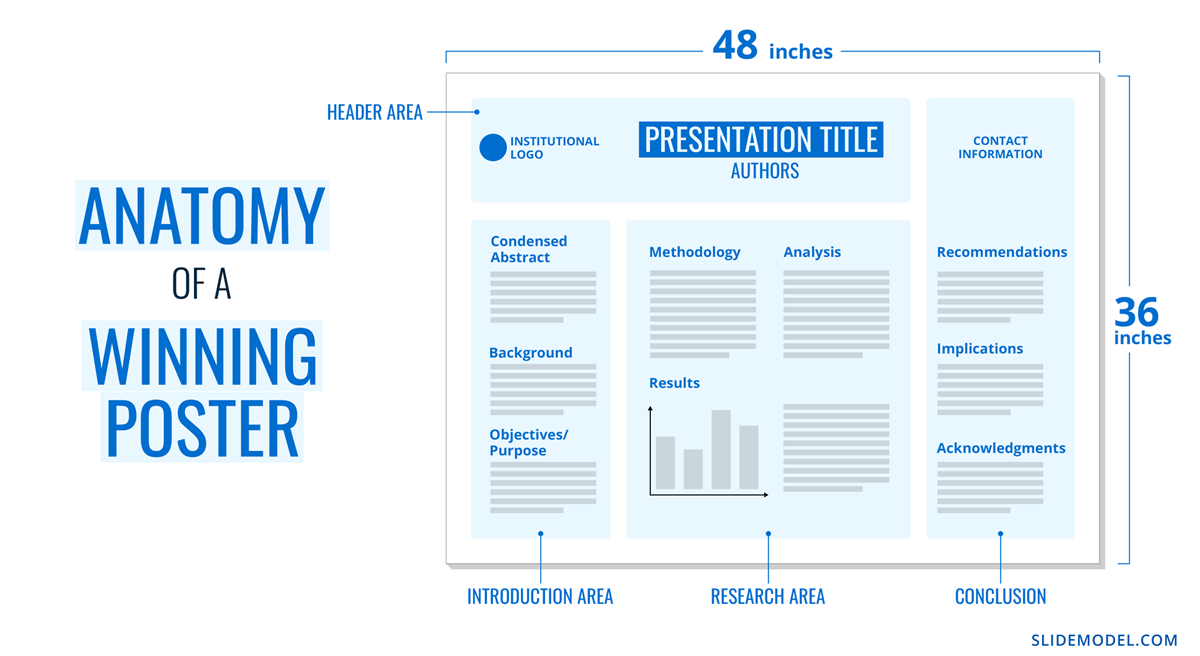

Anatomy of a Winning Poster Presentation

Do you want your research poster to perform well? Following the standard layout and adding a few personal touches will help attendees know how to read your poster and get the most out of your information.

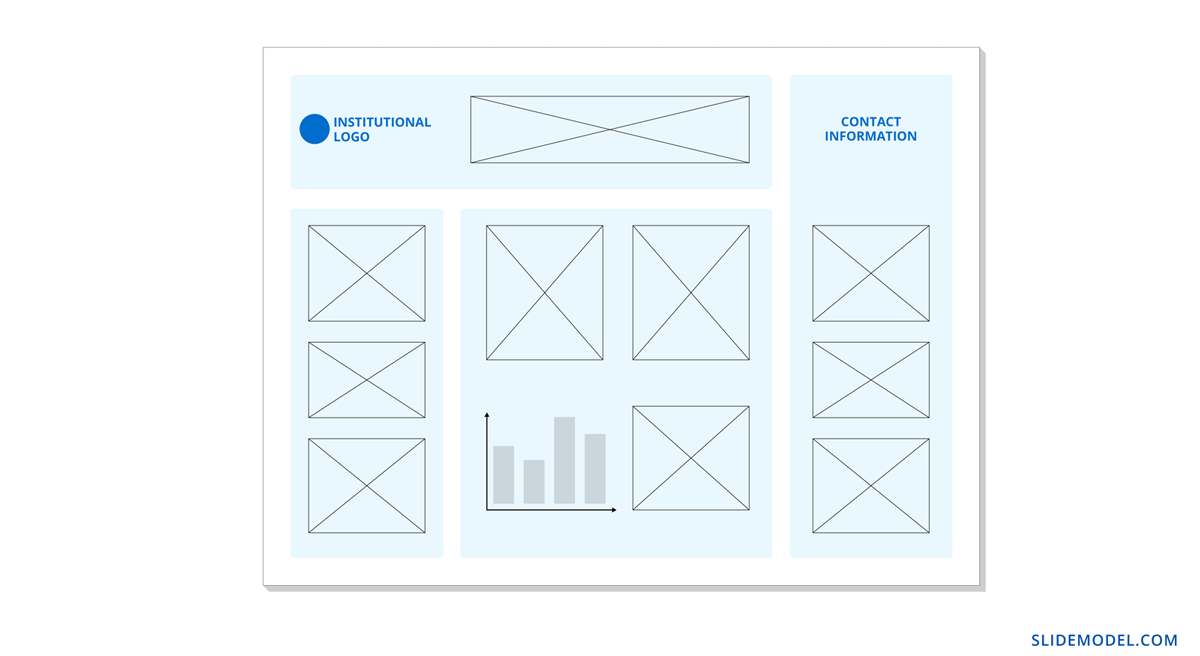

The overall size of your research poster ultimately depends on the dimensions of the provided space at the conference or research poster gallery. The poster orientation can be horizontal or vertical, with horizontal being the most common. In general, research posters measure 48 x 36 inches or are an A0 paper size.

A virtual poster can be the same proportions as the printed research poster, but you have more leeway regarding the dimensions. Virtual research posters should fit on a screen with no need to scroll, with 1080p resolution as a standard these days. A horizontal presentation size is ideal for that.

A research poster presentation has a standard layout of 2–5 columns with 2–3 sections each. Typical structures say to separate the content into four sections; 1. A horizontal header 2. Introduction column, 3. Research/Work/Data column, and 4. Conclusion column. Each unit includes topics that relate to your poster’s objective. Here’s a generalized outline for a poster presentation:

- Condensed Abstract

- Objectives/Purpose

- Methodology

- Recommendations

- Implications

- Acknowledgments

- Contact Information

The overview content you include in the units depends on your poster presentations’ theme, topic, industry, or field of research. A scientific or academic poster will include sections like hypothesis, methodology, and materials. A marketing analysis poster will include performance metrics and competitor analysis results.

There’s no way a poster can hold all the information included in your research paper or analysis report. The poster is an overview that invites the audience to want to find out more. That’s where supplement material comes in. Create a printed PDF handout or card with a QR code (created using a QR code generator ). Send the audience to the best online location for reading or downloading the complete paper.

What Makes a Poster Presentation Good and Effective?

For your poster presentation to be effective and well-received, it needs to cover all the bases and be inviting to find out more. Stick to the standard layout suggestions and give it a unique look and feel. We’ve put together some of the most critical research poster-creation tips in the list below. Your poster presentation will perform as long as you check all the boxes.

The information you choose to include in the sections of your poster presentation needs to be cohesive. Train your editing eye and do a few revisions before presenting. The best way to look at it is to think of The Big Picture. Don’t get stuck on the details; your attendees won’t always know the background behind your research topic or why it’s important.

Be cohesive in how you word the titles, the length of the sections, the highlighting of the most important data, and how your oral presentation complements the printed—or virtual—poster.

The most important characteristic of your poster presentation is its readability and clarity. You need a poster presentation with a balanced design that’s easy to read at a distance of 1.5 meters or 4 feet. The font size and spacing must be clear and neat. All the content must suggest a visual flow for the viewer to follow.

That said, you don’t need to be a designer to add something special to your poster presentation. Once you have the standard—and recognized—columns and sections, add your special touch. These can be anything from colorful boxes for the section titles to an interesting but subtle background, images that catch the eye, and charts that inspire a more extended look.

Storytelling is a presenting technique involving writing techniques to make information flow. Firstly, storytelling helps give your poster presentation a great introduction and an impactful conclusion.

Think of storytelling as the invitation to listen or read more, as the glue that connects sections, making them flow from one to another. Storytelling is using stories in the oral presentation, for example, what your lab partner said when you discovered something interesting. If it makes your audience smile and nod, you’ve hit the mark. Storytelling is like giving a research presentation a dose of your personality, and it can help turning your data into opening stories .

Design Tips For Creating an Effective Research Poster Presentation

The section above briefly mentioned how important design is to your poster presentation’s effectiveness. We’ll look deeper into what you need to know when designing a poster presentation.

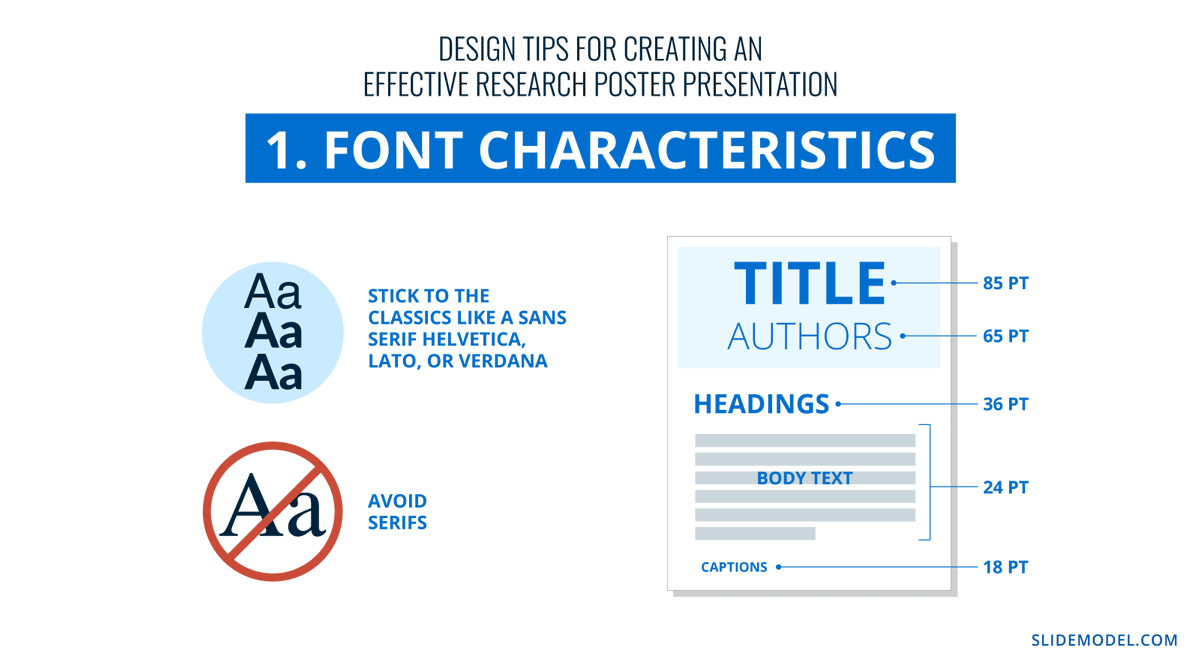

1. Font Characteristics

The typeface and size you choose are of great importance. Not only does the text need to be readable from two meters away, but it also needs to look and sit well on the poster. Stay away from calligraphic script typefaces, novelty typefaces, or typefaces with uniquely shaped letters.

Stick to the classics like a sans serif Helvetica, Lato, Open Sans, or Verdana. Avoid serif typefaces as they can be difficult to read from far away. Here are some standard text sizes to have on hand.

- Title: 85 pt

- Authors: 65 pt

- Headings: 36 pt

- Body Text: 24 pt

- Captions: 18 pt

If you feel too prone to use serif typefaces, work with a font pairing tool that helps you find a suitable solution – and intend those serif fonts for heading sections only. As a rule, never use more than 3 different typefaces in your design. To make it more dynamic, you can work with the same font using light, bold, and italic weights to put emphasis on the required areas.

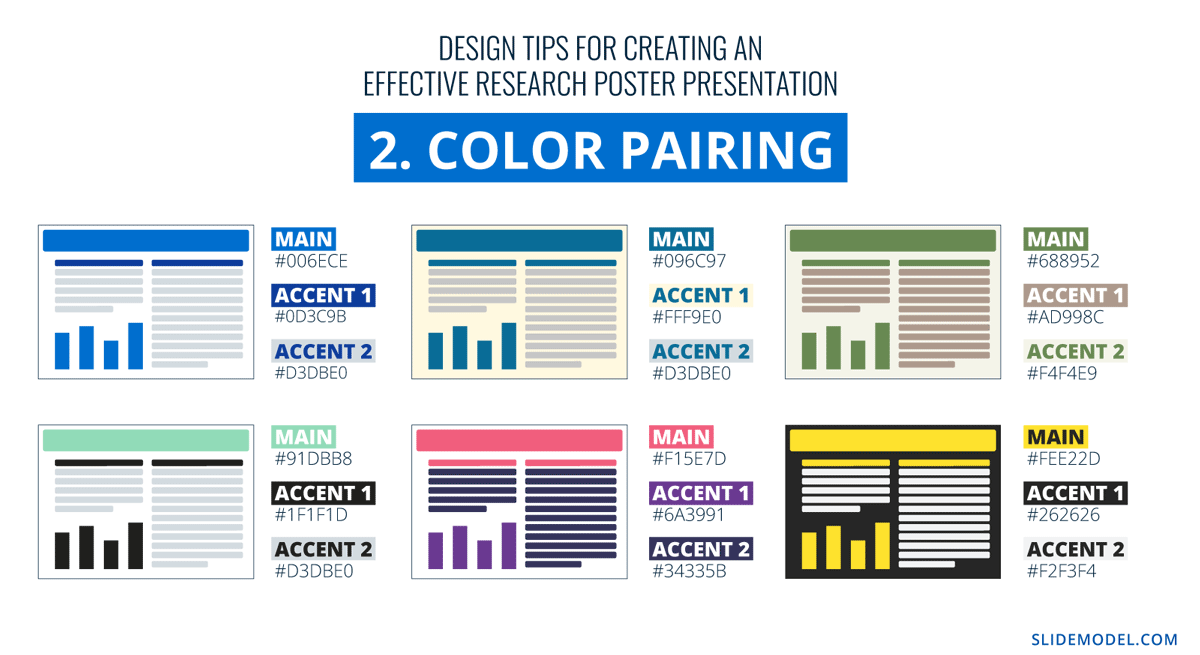

2. Color Pairing

Using colors in your poster presentation design is a great way to grab the viewer’s attention. A color’s purpose is to help the viewer follow the data flow in your presentation, not distract. Don’t let the color take more importance than the information on your poster.

Choose one main color for the title and headlines and a similar color for the data visualizations. If you want to use more than one color, don’t create too much contrast between them. Try different tonalities of the same color and keep things balanced visually. Your color palette should have at most one main color and two accent colors.

Black text over a white background is standard practice for printed poster presentations, but for virtual presentations, try a very light gray instead of white and a very dark gray instead of black. Additionally, use variations of light color backgrounds and dark color text. Make sure it’s easy to read from two meters away or on a screen, depending on the context. We recommend ditching full white or full black tone usage as it hurts eyesight in the long term due to its intense contrast difference with the light ambiance.

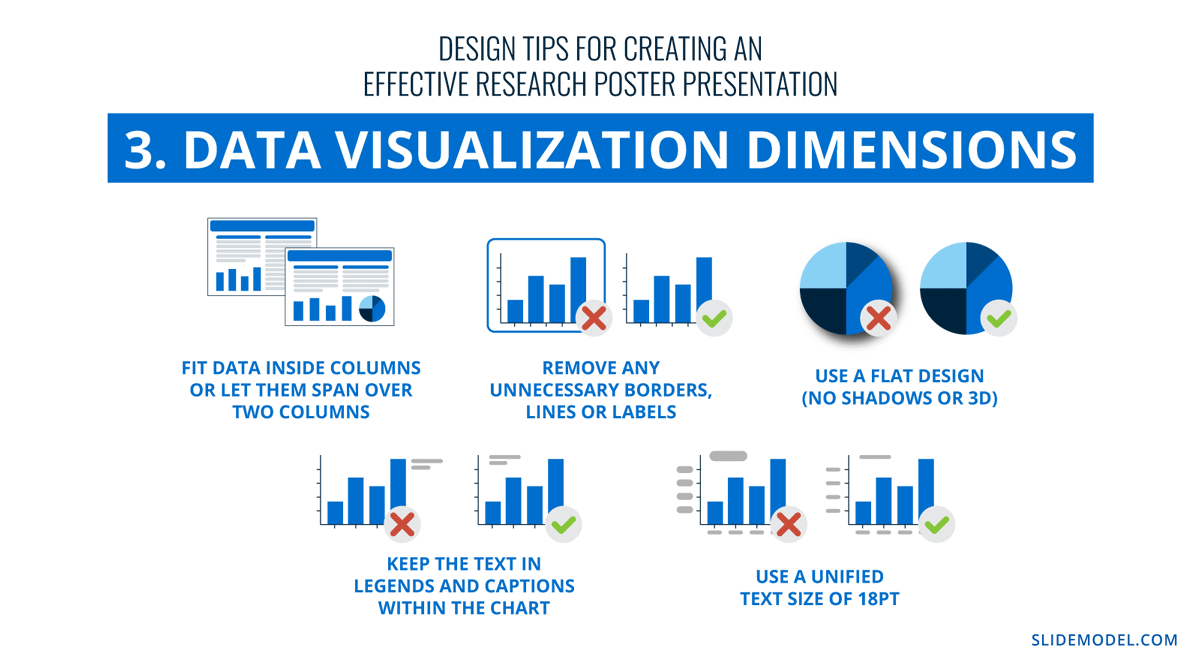

3. Data Visualization Dimensions

Just like the text, your charts, graphs, and data visualizations must be easy to read and understand. Generally, if a person is interested in your research and has already read some of the text from two meters away, they’ll come closer to look at the charts and graphs.

Fit data visualizations inside columns or let them span over two columns. Remove any unnecessary borders, lines, or labels to make them easier to read at a glance. Use a flat design without shadows or 3D characteristics. The text in legends and captions should stay within the chart size and not overflow into the margins. Use a unified text size of 18px for all your data visualizations.

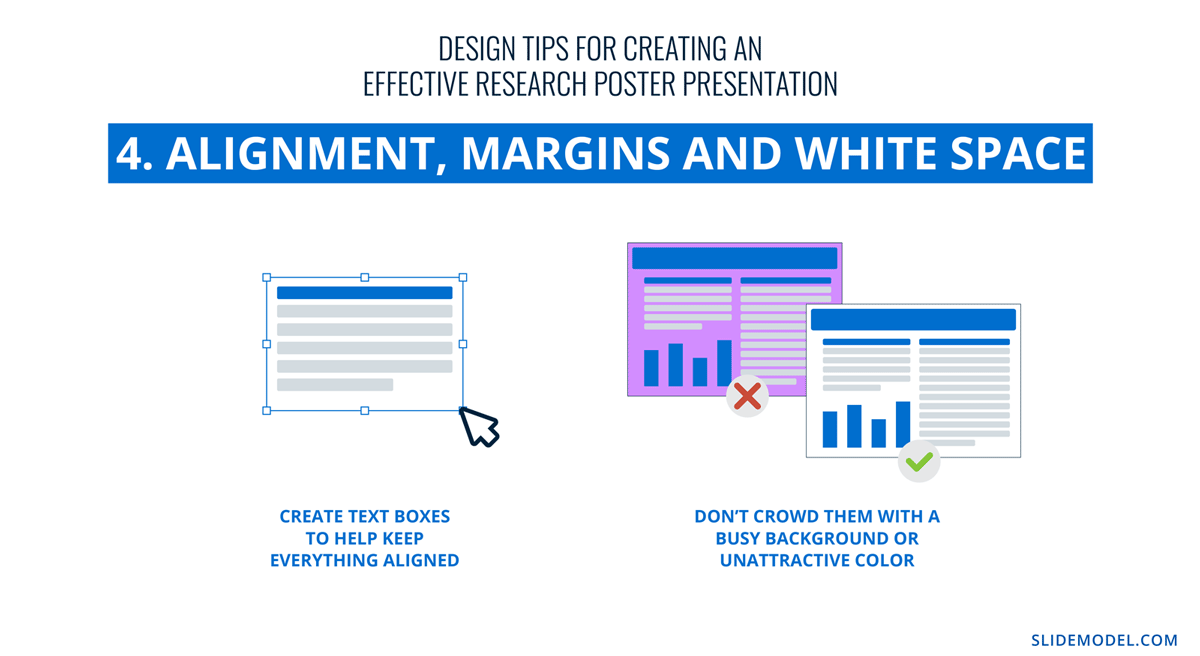

4. Alignment, Margins, and White Space

Finally, the last design tip for creating an impressive and memorable poster presentation is to be mindful of the layout’s alignment, margins, and white space. Create text boxes to help keep everything aligned. They allow you to resize, adapt, and align the content along a margin or grid.

Take advantage of the white space created by borders and margins between sections. Don’t crowd them with a busy background or unattractive color.

Calculate margins considering a print format. It is a good practice in case the poster presentation ends up becoming in physical format, as you won’t need to downscale your entire design (affecting text readability in the process) to preserve information.

There are different tools that you can use to make a poster presentation. Presenters who are familiar with Microsoft Office prefer to use PowerPoint. You can learn how to make a poster in PowerPoint here.

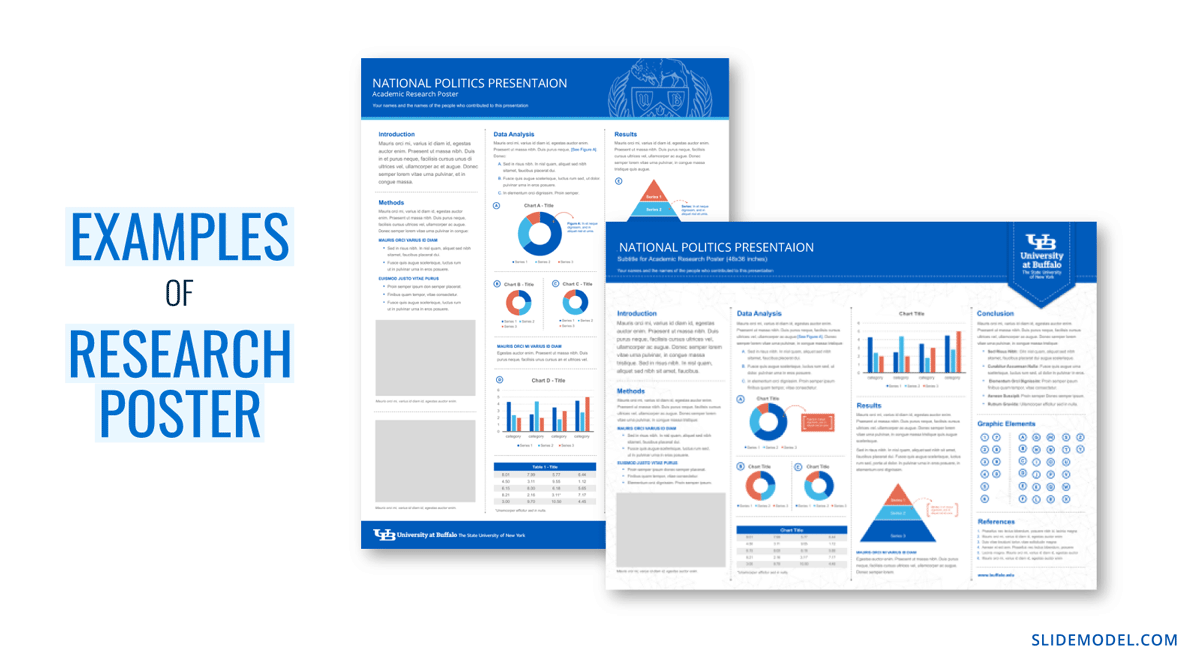

Poster Presentation Examples

Before you start creating a poster presentation, look at some examples of real research posters. Get inspired and get creative.

Research poster presentations printed and mounted on a board look like the one in the image below. The presenter stands to the side, ready to share the information with visitors as they walk up to the panels.

With more and more conferences staying virtual or hybrid, the digital poster presentation is here to stay. Take a look at examples from a poster session at the OHSU School of Medicine .

Use SlideModel templates to help you create a winning poster presentation with PowerPoint and Google Slides. These poster PPT templates will get you off on the right foot. Mix and match tables and data visualizations from other poster slide templates to create your ideal layout according to the standard guidelines.

If you need a quick method to create a presentation deck to talk about your research poster at conferences, check out our Slides AI presentation maker. A tool in which you add the topic, curate the outline, select a design, and let AI do the work for you.

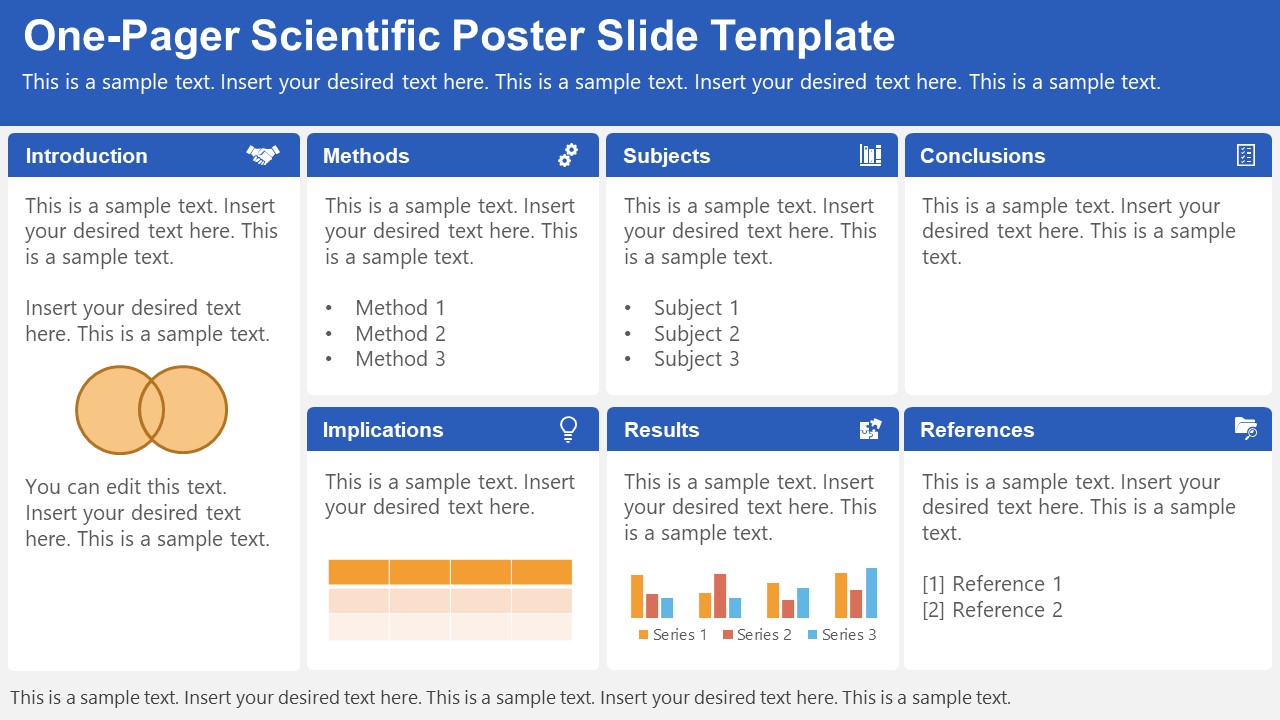

1. One-pager Scientific Poster Template for PowerPoint

A PowerPoint template tailored to make your poster presentations an easy-to-craft process. Meet our One-Pager Scientific Poster Slide Template, entirely editable to your preferences and with ample room to accommodate graphs, data charts, and much more.

Use This Template

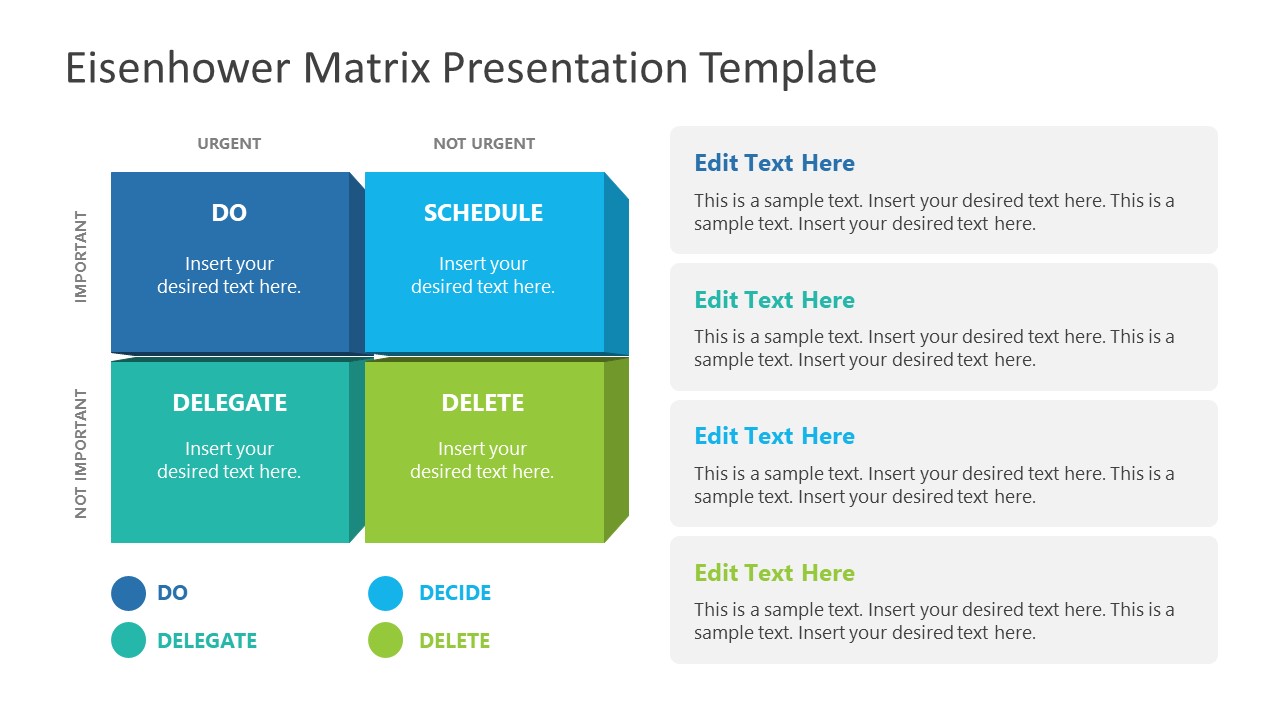

2. Eisenhower Matrix Slides Template for PowerPoint

An Eisenhower Matrix is a powerful tool to represent priorities, classifying work according to urgency and importance. Presenters can use this 2×2 matrix in poster presentations to expose the effort required for the research process, as it also helps to communicate strategy planning.

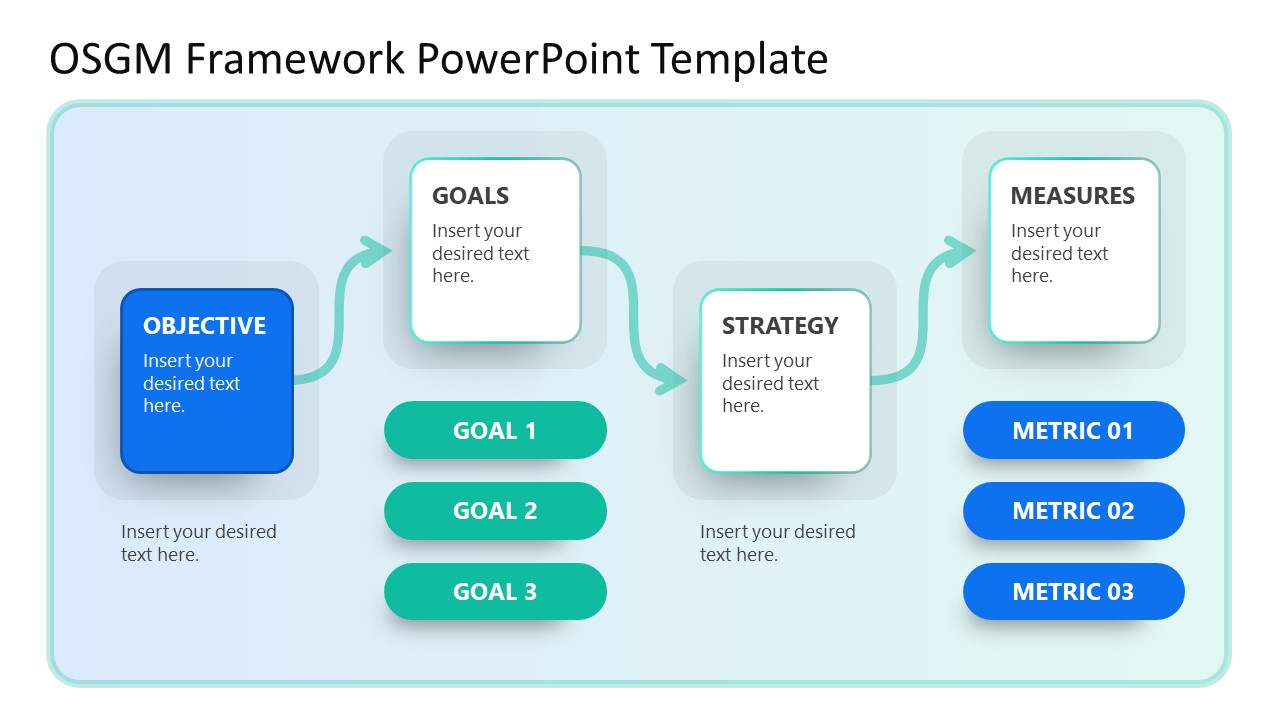

3. OSMG Framework PowerPoint Template

Finally, we recommend presenters check our OSMG Framework PowerPoint template, as it is an ideal tool for representing a business plan: its goals, strategies, and measures for success. Expose complex processes in a simplified manner by adding this template to your poster presentation.

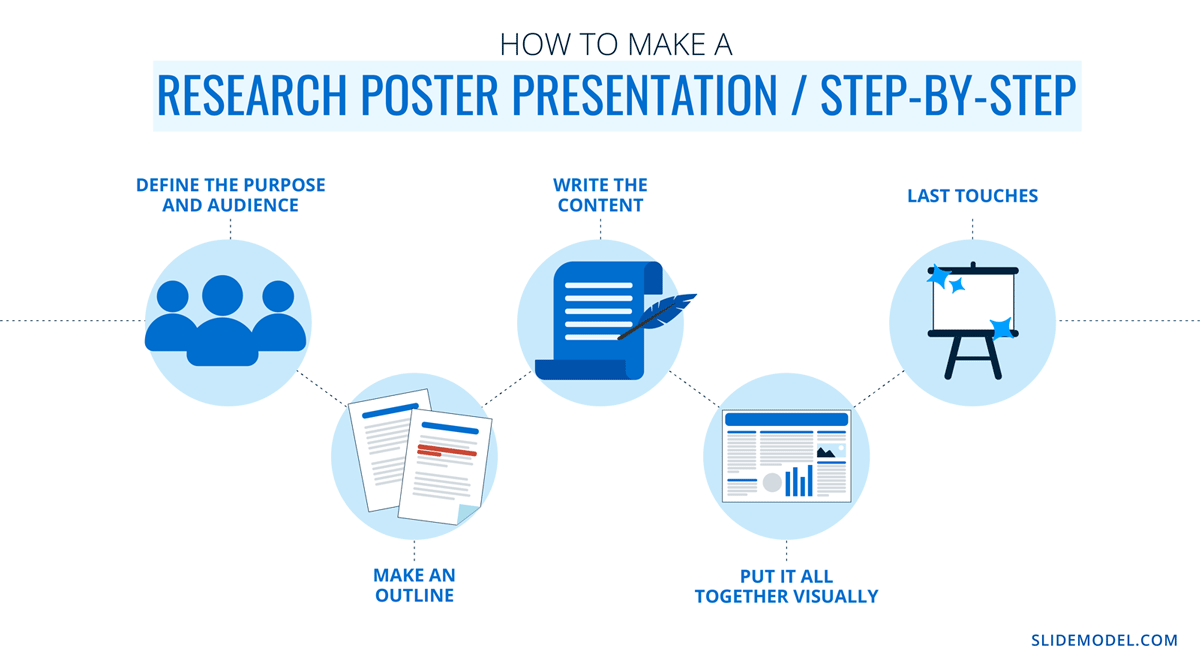

Remember these three words when making your research poster presentation: develop, design, and present. These are the three main actions toward a successful poster presentation.

The section below will take you on a step-by-step journey to create your next poster presentation.

Step 1: Define the purpose and audience of your poster presentation

Before making a poster presentation design, you’ll need to plan first. Here are some questions to answer at this point:

- Are they in your field?

- Do they know about your research topic?

- What can they get from your research?

- Will you print it?

- Is it for a virtual conference?

Step 2: Make an outline

With a clear purpose and strategy, it’s time to collect the most important information from your research paper, analysis, or documentation. Make a content dump and then select the most interesting information. Use the content to draft an outline.

Outlines help formulate the overall structure better than going straight into designing the poster. Mimic the standard poster structure in your outline using section headlines as separators. Go further and separate the content into the columns they’ll be placed in.

Step 3: Write the content

Write or rewrite the content for the sections in your poster presentation. Use the text in your research paper as a base, but summarize it to be more succinct in what you share.

Don’t forget to write a catchy title that presents the problem and your findings in a clear way. Likewise, craft the headlines for the sections in a similar tone as the title, creating consistency in the message. Include subtle transitions between sections to help follow the flow of information in order.

Avoid copying/pasting entire sections of the research paper on which the poster is based. Opt for the storytelling approach, so the delivered message results are interesting for your audience.

Step 4: Put it all together visually

This entire guide on how to design a research poster presentation is the perfect resource to help you with this step. Follow all the tips and guidelines and have an unforgettable poster presentation.

Moving on, here’s how to design a research poster presentation with PowerPoint Templates . Open a new project and size it to the standard 48 x 36 inches. Using the outline, map out the sections on the empty canvas. Add a text box for each title, headline, and body text. Piece by piece, add the content into their corresponding text box.

Transform the text information visually, make bullet points, and place the content in tables and timelines. Make your text visual to avoid chunky text blocks that no one will have time to read. Make sure all text sizes are coherent for all headings, body texts, image captions, etc. Double-check for spacing and text box formatting.

Next, add or create data visualizations, images, or diagrams. Align everything into columns and sections, making sure there’s no overflow. Add captions and legends to the visualizations, and check the color contrast with colleagues and friends. Ask for feedback and progress to the last step.

Step 5: Last touches

Time to check the final touches on your poster presentation design. Here’s a checklist to help finalize your research poster before sending it to printers or the virtual summit rep.

- Check the resolution of all visual elements in your poster design. Zoom to 100 or 200% to see if the images pixelate. Avoid this problem by using vector design elements and high-resolution images.

- Ensure that charts and graphs are easy to read and don’t look crowded.

- Analyze the visual hierarchy. Is there a visual flow through the title, introduction, data, and conclusion?

- Take a step back and check if it’s legible from a distance. Is there enough white space for the content to breathe?

- Does the design look inviting and interesting?

An often neglected topic arises when we need to print our designs for any exhibition purpose. Since A0 is a hard-to-manage format for most printers, these poster presentations result in heftier charges for the user. Instead, you can opt to work your design in two A1 sheets, which also becomes more manageable for transportation. Create seamless borders for the section on which the poster sheets should meet, or work with a white background.

Paper weight options should be over 200 gsm to avoid unwanted damage during the printing process due to heavy ink usage. If possible, laminate your print or stick it to photographic paper – this shall protect your work from spills.

Finally, always run a test print. Gray tints may not be printed as clearly as you see them on screen (this is due to the RGB to CMYK conversion process). Other differences can be appreciated when working with ink jet plotters vs. laser printers. Give yourself enough room to maneuver last-minute design changes.

Presenting a research poster is a big step in the poster presentation cycle. Your poster presentation might or might not be judged by faculty or peers. But knowing what judges look for will help you prepare for the design and oral presentation, regardless of whether you receive a grade for your work or if it’s business related. Likewise, the same principles apply when presenting at an in-person or virtual summit.

The opening statement

Part of presenting a research poster is welcoming the viewer to your small personal area in the sea of poster presentations. You’ll need an opening statement to pitch your research poster and get the viewers’ attention.

Draft a 2 to 3-sentence pitch that covers the most important points:

- What the research is

- Why was it conducted

- What the results say

From that opening statement, you’re ready to continue with the oral presentation for the benefit of your attendees.

The oral presentation

During the oral presentation, share the information on the poster while conversing with the interested public. Practice many times before the event. Structure the oral presentation as conversation points, and use the poster’s visual flow as support. Make eye contact with your audience as you speak, but don’t make them uncomfortable.

Pro Tip: In a conference or summit, if people show up to your poster area after you’ve started presenting it to another group, finish and then address the new visitors.

QA Sessions

When you’ve finished the oral presentation, offer the audience a chance to ask questions. You can tell them before starting the presentation that you’ll be holding a QA session at the end. Doing so will prevent interruptions as you’re speaking.

If presenting to one or two people, be flexible and answer questions as you review all the sections on your poster.

Supplemental Material

If your audience is interested in learning more, you can offer another content type, further imprinting the information in their minds. Some ideas include; printed copies of your research paper, links to a website, a digital experience of your poster, a thesis PDF, or data spreadsheets.

Your audience will want to contact you for further conversations; include contact details in your supplemental material. If you don’t offer anything else, at least have business cards.

Even though conferences have changed, the research poster’s importance hasn’t diminished. Now, instead of simply creating a printed poster presentation, you can also make it for digital platforms. The final output will depend on the conference and its requirements.

This guide covered all the essential information you need to know for creating impactful poster presentations, from design, structure and layout tips to oral presentation techniques to engage your audience better .

Before your next poster session, bookmark and review this guide to help you design a winning poster presentation every time.

Like this article? Please share

Cool Presentation Ideas, Design, Design Inspiration Filed under Design

Related Articles

Filed under Design • January 11th, 2024

How to Use Figma for Presentations

The powerful UI/UX prototyping software can also help us to craft high-end presentation slides. Learn how to use Figma as a presentation software here!

Filed under Design • December 28th, 2023

Multimedia Presentation: Insights & Techniques to Maximize Engagement

Harnessing the power of multimedia presentation is vital for speakers nowadays. Join us to discover how you can utilize these strategies in your work.

Filed under Google Slides Tutorials • December 15th, 2023

How to Delete a Text Box in Google Slides

Discover how to delete a text box in Google Slides in just a couple of clicks. Step-by-step guide with images.

Leave a Reply

Jump to navigation

Cochrane Training

Presenting at conferences.

Academic conferences are a useful way to present the results of a Cochrane review to people either through an oral presentation, a poster presentation, or a booth. Conferences also have the additional benefit of networking and an opportunity to promote both Cochrane and the results of your review to peers.

How to present at conferences

Oral presentation.

Good oral presentations should be captivating, get the message across clearly, consider the language and context of the audience, and keep people engaged throughout. Not everyone can be an expert public speaker, and in many ways, it takes practice to become good at delivering engaging oral presentations. Our resources below can help.

The ‘Community Templates’ section on the brand resources page provides templates for PowerPoint presentations that can be used at conferences. There is a video on Creating a PowerPoint Presentation to explain how to use the template.

This video gives some tips for effective presentations at conferences such as:

- Choosing your content

- Using an appropriate structure

- Eliminating jargon

- Creating effective slides

- Finding your passion!

Poster presentation

Make your poster one that people want to stop and look at when you are at a conference. If you are preparing a poster presentation, these resources will help your work stand out in a sea of posters:

- The ‘Community Templates’ on the brand resources page provide pre-branded poster templates. They are very simple to use – you just need to download and add in the content.

- Cochrane officially endorses the #betterposter design. These new templates offer posters with less text and a decluttered design with the main finding in plain English as the highlighted feature. Learn more about the design and watch a quick introduction.

- This information sheet contains useful questions for preparing a poster for a conference.

Conference booth

At some conferences, you may have the opportunity to showcase your work at a booth. If you have multiple dissemination products that you created, you can display them here. You might also want to bring screens or computers to make your booth more interactive. Like posters, you want to make sure your booth is one that people want to visit and interact with.

You can contact Cochrane to discuss your event , get clarification on Cochrane event policies, or help with event branding such as special banners, flyers or branded items to give away.

If you are hosting the symposium or conference, contact Cochrane to have it listed and promoted on our website.

Sharing your presentation

When you know you'll be presenting at a conference, share the details on social media. For more information on social media platforms and how to use them effectively, visit this page. On social media, tell people where you are going, what you'll be presenting, and provide a link to sign up to attend (if possible).

During your presentation, you might want to consider having a colleague or peer live-tweeting. This will give you content to re-tweet later, and give people in the room content to share as well. Others in the room might also be tweeting about your presentation, which you can re-tweet later. You might want to consider live streaming your presentation on YouTube, Facebook or Instagram so your followers who aren’t in attendance can watch you present in real time.

If you don’t have your own social media accounts, we can share a picture of you at a conference on Cochrane’s social media. It is great to get a picture beside your poster, at your booth, or beside something with the conference name. If you are interested, please send the following to Muriah Umoquit at [email protected] : - Your name - Your Instagram/Twitter handle if you want it included - The related Review or Centre group - Title of your poster or presentation - Link to Cochrane Review if appropriate - Title of the conference - Official conference hashtag - A picture

After your presentation, you can distribute materials to your audience so that the information stays with them. This could be copies or recordings of the presentation, or another dissemination product related to what you presented. You can distribute in person at the conference, afterwards if you have the details of who attended your session, or through social media for anyone who may have followed you on a social media platform because of your presentation.

Evaluating the effect of your presentation

Many conferences will do their own evaluation of their conference programming, including oral presentations that were given. They may ask attendees questions about the topic that was presented, the effectiveness of the presenters, and the quality of the presentation. Ask your conference host whether they evaluate presentations. If they do, you can request feedback on your presentation that way.

You can also seek feedback on your own from your audience if you gave a presentation. You can do this through hard copy surveys at tables or chairs that you can collect, through email after your presentation, or you can do live evaluation surveys. These work by surveying people in real time through posing a question you can embed in your presentation, and have audience members provide input on their phones by visiting a link you give them. Sli.do and Menti are popular tools for this.

Examples of presenting at conferences by Cochrane groups

This is a great case study of how Cochrane UK used a booth at a conference – with great tips on what to do before, during, and after the conference.

Back to top

- © 2022

Academic Conference Presentations

A Step-by-Step Guide

- Mark R. Freiermuth 0

Gunma Prefectural Women’s University, Tamamura-machi, Japan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

- Takes the presenter on a journey from initial idea to conference presentation

- Addresses topics such as abstract writing, choosing a conference, posters and online versus face-to-face presentations

- Based on the author's own experiences

1783 Accesses

26 Altmetric

- Table of contents

About this book

Authors and affiliations, about the author, bibliographic information.

- Publish with us

Buying options

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check for access.

Table of contents (9 chapters)

Front matter, next up on stage….

Mark R. Freiermuth

Conferences: Choose Wisely Grasshopper

Getting started: the precise abstract, after the excitement fades: preparing for the presentation, tea for two or more: the group presentation, conferences: live and in-person, ghosts in the machine: the virtual presentation, the seven deadly sins: what not to do, the top five, back matter.

This book provides a step-by-step journey to giving a successful academic conference presentation, taking readers through all of the potential steps along the way—from the initial idea and the abstract submission all the way up to the presentation itself. Drawing on the author's own experiences, the book highlights good and bad practices while explaining each introduced feature in a very accessible style. It provides tips on a wide range of issues such as writing up an abstract, choosing the right conference, negotiating group presentations, giving a poster presentation, what to include in a good presentation, conference proceedings and presenting at virtual or hybrid events. This book will be of particular interest to graduate students, early-career researchers and non-native speakers of English, as well as students and scholars who are interested in English for Academic Purposes, Applied Linguistics, Communication Studies and generally speaking, most of the Social Sciences. With that said, because of the book’s theme, many of the principles included within will appeal to broad spectrum of academic disciplines.

- English for Academic Purposes

- public speaking

- research presentation

- academic skills

- conferences

- poster presentations

-Sarah Mercer , Professor for Foreign Language Teaching and the Head of the ELT Research and Methodology Department, University of Graz, Austria

Mark R. Freiermuth is Professor of Applied Linguistics at Gunma Prefectural Women's University, Japan.

Book Title : Academic Conference Presentations

Book Subtitle : A Step-by-Step Guide

Authors : Mark R. Freiermuth

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-21124-9

Publisher : Palgrave Macmillan Cham

eBook Packages : Social Sciences , Social Sciences (R0)

Copyright Information : The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2022

Hardcover ISBN : 978-3-031-21123-2 Published: 05 January 2023

eBook ISBN : 978-3-031-21124-9 Published: 04 January 2023

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : VII, 159

Number of Illustrations : 45 b/w illustrations

Topics : Applied Linguistics , Research Skills , Career Skills , Sociology of Education

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

The Art of Effective Poster Presentations at Conferences

Conference poster presentations are a vital platform for researchers to share their work, exchange ideas, and engage with fellow scholars. A well-executed poster can effectively communicate your research findings, captivate your audience, and spark meaningful conversations. In this article, we will delve into the art of crafting and delivering effective poster presentations at conferences, offering valuable insights and strategies to help you make the most of this opportunity.

Why Are Poster Presentations Important?

In the realm of academic conferences, where researchers from diverse fields converge to exchange knowledge and ideas, poster presentations hold a distinct and essential place. These visual displays of research findings are more than just static images on a board; they are dynamic tools for communication, engagement, and networking. Here, we explore why poster presentations are integral to the conference experience and academic discourse.

1. Accessibility and Inclusivity: One of the primary virtues of poster presentations is their accessibility. Unlike oral presentations that are limited by concurrent sessions, poster sessions typically span longer durations, ensuring that attendees have ample opportunities to engage with the content. This inclusivity allows researchers to reach a broader audience and receive feedback from peers who may not have attended their oral presentation.

2. Ideal for Complex Visual Content: Some research findings are inherently visual, relying on graphs, charts, images, and diagrams to convey complex information. Posters provide an ideal platform for presenting such content effectively. They allow for the integration of visuals that can be absorbed at a glance, enhancing the audience's understanding of intricate data.

3. Engaging Interactions: Poster sessions foster interactive and one-on-one engagements between presenters and attendees. Researchers have the chance to discuss their work, answer questions, and engage in meaningful dialogues. This direct interaction enables deeper dives into the research, encourages brainstorming, and often leads to valuable insights and collaborations.

4. Sharing Preliminary and Ongoing Work: Not all research is finalized and ready for a full oral presentation. Poster presentations offer the flexibility to share preliminary findings, ongoing projects, or research in progress. This openness allows researchers to receive early feedback, refine their methodologies, and make connections that can propel their work forward.

5. Enhancing Presentation Skills: Crafting an effective poster and presenting it succinctly enhance researchers' communication and presentation skills. They must distill their work into a visually appealing and concise format, which is a valuable skill for conveying complex ideas to a broader audience.

6. Opportunities for Early-Career Researchers: Poster sessions often provide an excellent platform for early-career researchers to gain exposure and build their professional networks. It offers a less intimidating setting for them to share their work, receive constructive feedback, and connect with experienced researchers who can offer mentorship and guidance.

7. Showcasing Multidisciplinary Research: Conferences bring together scholars from various disciplines. Posters enable researchers to showcase multidisciplinary projects that bridge the gaps between different fields. This interdisciplinary exchange can lead to innovative solutions and collaborations that transcend traditional academic boundaries.

8. A Visual Snapshot of Research: Poster presentations serve as visual snapshots of research projects. Attendees can quickly scan the content to determine if a poster aligns with their interests, making it easier to decide which presentations to explore further.

Receive Free Grammar and Publishing Tips via Email

The key elements of a successful conference poster.

Creating a successful conference poster is both an art and a science. It requires careful consideration of design, content, and presentation to effectively communicate your research findings. Here are the key elements that contribute to a successful conference poster:

1. Clear and Compelling Title: The poster's title should be concise, engaging, and instantly convey the essence of your research. A well-crafted title captures the attention of viewers and invites them to learn more. It's often the first impression your poster makes, so make it count.

2. Engaging Design: Visual appeal is crucial. Your poster should have a clean and balanced layout with a logical flow. Use fonts that are easy to read and choose colors that enhance readability. Visual elements like graphs, images, and diagrams should be integrated seamlessly into the design.

3. Structured Content: Organize your poster content in a structured manner. Include sections such as an introduction, methods, results, discussion, and conclusions. Use clear headings and subheadings to guide viewers through your research journey. A well-organized poster makes it easier for viewers to follow your narrative.

4. Captivating Visuals: Visuals are a powerful tool for conveying information. Use graphs, charts, images, and diagrams to illustrate key points and trends in your research. Ensure that visuals are of high quality and directly support your findings. Visuals should be easy to understand at a glance.

5. Concise Text: Keep text concise and focused. Avoid long paragraphs and excessive jargon. Use bullet points and numbered lists to break up information into digestible chunks. Your text should complement the visuals and provide context without overwhelming the viewer.

6. Clear Data Representation: If your research involves data, present it clearly and concisely. Use appropriate data visualization techniques to convey trends and results. Ensure that axes are labeled, units are specified, and data points are clearly defined. Viewers should be able to grasp your findings without confusion.

7. Effective Use of Space: Utilize the available space wisely. Avoid clutter and allow for ample white space to prevent visual overload. Space should be allocated to different sections and visuals in a balanced manner, ensuring that no aspect of your research is overshadowed.

8. Cohesive Visual Theme: Maintain a cohesive visual theme throughout your poster. Consistency in fonts, colors, and overall design enhances the professional appearance of your poster. A well-designed poster reflects positively on your research.

9. Engaging Headings and Captions: Headings and captions should be engaging and informative. Use them to highlight key findings and insights. A well-crafted heading or caption can draw viewers' attention to specific aspects of your research.

10. Contact Information and References: Include your contact information, such as an email address or QR code linked to your professional profile. Don't forget to provide references for your research sources, which adds credibility to your work.

A successful conference poster is a harmonious blend of design, content, and presentation. Clear and compelling visuals, concise text, structured content, and an engaging title are essential elements for effectively conveying your research. By carefully considering these key elements, you can create a poster that captivates your audience and leaves a lasting impression at your next conference presentation.

Preparing for Your Poster Presentation

Creating a stellar conference poster is only part of the equation for a successful presentation. Equally important is your preparation to engage with your audience effectively. Here's how to prepare for your poster presentation:

1. Practice Your Elevator Pitch: Be ready to deliver a concise summary of your research in a minute or less. This elevator pitch should capture the essence of your work and pique the interest of passersby. It serves as the initial hook to draw viewers to your poster.

2. Anticipate Questions: Think about the questions and comments you might receive during your presentation. Prepare concise and informative responses to common queries related to your research. Anticipating questions helps you stay confident and composed during interactions.

3. Rehearse Your Presentation: Practice presenting your poster to colleagues, mentors, or friends. Seek their feedback on your delivery, clarity, and overall presentation skills. Rehearsing your presentation multiple times ensures you can confidently convey your research findings.

4. Set Up Your Space: Arrive early at the conference venue to set up your poster and any supplementary materials. Ensure that your poster is properly affixed and easy to read. Check that your presentation area is well-lit and free of distractions.

5. Organize Supporting Materials: Prepare handouts, business cards, or QR codes linked to your research for interested attendees. These materials provide additional information for those who want to explore your work further. Be ready to distribute them as needed.

6. Dress Professionally: Your attire should be professional and appropriate for the conference. A polished appearance enhances your credibility and professionalism when engaging with attendees.

7. Develop a Presentation Strategy: Decide how you will approach engagement with attendees. Will you actively invite passersby to your poster? Will you use visual aids to guide your discussions? Having a strategy in mind helps you manage interactions effectively.

8. Maintain Eye Contact: When engaging with attendees, maintain eye contact and a welcoming demeanor. A friendly and approachable attitude can encourage more interactions and make attendees feel comfortable asking questions.

9. Share Your Passion: Showcase your enthusiasm for your research. Passion is infectious and can draw attendees to your poster. Explain why your work matters and how it contributes to the field.

10. Be Adaptable: Be flexible and adaptable during your presentation. Tailor your discussions to the interests and knowledge levels of your audience. Some may seek detailed technical information, while others may prefer a high-level overview.

11. Respect Time Constraints: Be mindful of the time available for each interaction. Respect attendees' schedules and avoid monopolizing their time. Concisely convey your research and offer to provide more information if requested.

12. Collect Feedback: Encourage attendees to share their feedback and insights. Constructive criticism can help you refine your research and presentation skills. Consider providing a feedback form or inviting verbal comments.

Effective preparation is the key to a successful poster presentation. Practice your elevator pitch, anticipate questions, and rehearse your presentation. Arrive early, organize supporting materials, and maintain a professional appearance. Develop a presentation strategy, engage attendees with enthusiasm, and adapt to their needs. By preparing diligently, you can confidently showcase your research and engage with your audience effectively at the conference.

Engaging With Your Audience

A conference poster presentation isn't just about displaying your research; it's an opportunity to engage with your audience, foster discussions, and share your passion for your work. Here are strategies for effectively engaging with your audience during your poster presentation:

1. Maintain Eye Contact: When attendees approach your poster, greet them with a smile and make eye contact. Establishing this personal connection creates a welcoming atmosphere and encourages interaction.

2. Use Visual Aids: Visual aids, such as a pointer or your own finger, can help direct attendees' attention to specific sections of your poster. Use them to highlight key findings or data points as you explain your research.

3. Ask Open-Ended Questions: Encourage conversations by asking open-ended questions. Instead of questions with yes-or-no answers, pose inquiries that invite attendees to share their thoughts or experiences related to your research. For example, "What are your thoughts on this approach?" or "Have you encountered similar challenges in your work?"

4. Share Anecdotes and Stories: Weave relatable anecdotes or stories into your presentation to humanize your research. Personal experiences or challenges you've encountered on your research journey can make your work more relatable and memorable.

5. Tailor Your Explanation: Adjust your explanation based on your audience's level of familiarity with your field. Some attendees may be experts, while others may have limited knowledge. Tailor your discussion to their needs, offering more in-depth explanations when necessary.

6. Use Analogies and Metaphors: Complex research concepts can be simplified with the use of analogies or metaphors. Compare your findings to everyday experiences or objects to make them more accessible and relatable.

7. Provide Real-World Relevance: Emphasize the real-world relevance of your research. Explain how your findings can address practical problems or contribute to advancements in your field. Attendees are more likely to engage when they see the practical implications.

8. Listen Actively: Engaging with your audience is a two-way interaction. Listen actively to their questions and comments. Show appreciation for their input, and ask follow-up questions to delve deeper into the discussion.

9. Offer Handouts or Additional Information: Some attendees may want to explore your research in greater detail. Offer handouts, business cards, or QR codes linked to supplementary materials, such as your full paper or additional data. This provides an avenue for further engagement.

10. Be Respectful of Time: Respect attendees' time constraints. If someone is in a hurry, provide a concise overview of your research and offer to share more information later. For those interested in a more in-depth discussion, allocate additional time.

11. Foster a Positive Environment: Create a positive and inviting environment at your poster. Be approachable, patient, and enthusiastic. Attendees are more likely to engage when they feel comfortable and welcomed.

Networking Opportunities

While your primary goal at a conference poster presentation is to showcase your research, it's also an excellent opportunity for networking. Building connections with fellow researchers, potential collaborators, and experts in your field can be as valuable as presenting your work. Here's how to make the most of networking opportunities during your poster presentation:

1. Be Approachable: Approachability is key to successful networking. Smile, make eye contact, and welcome attendees who visit your poster. A friendly and open demeanor encourages interactions.

2. Elevator Pitch: Perfect your elevator pitch—an engaging and concise summary of your research. It serves as an icebreaker and provides a starting point for conversations.

3. Exchange Contact Information: Be prepared to exchange contact information. Business cards, contact cards, or simply sharing your email address can facilitate future communication.

4. Share Your Passion: Express your enthusiasm for your research. Passion is contagious and can make you more memorable to those you meet. Explain why your work matters and how it can benefit the field.

5. Ask About Others' Work: Show genuine interest in others' research. Ask questions about their projects, findings, and interests. Active listening and curiosity can leave a positive impression.

6. Find Common Ground: Seek common ground or shared research interests. Identifying shared research areas can lay the foundation for potential collaborations or further discussions.

7. Attend Networking Events: Many conferences organize dedicated networking events or receptions. Attend these gatherings to meet a wider range of attendees, including keynote speakers and senior researchers.

8. Visit Other Posters: Don't limit your interactions to your own poster. Visit other poster presentations to learn about diverse research topics and meet fellow presenters.

9. Utilize Social Media: Follow the conference's official social media accounts and use event-specific hashtags to connect with attendees online. This can lead to post-conference networking opportunities.

10. Join Discussion Panels: If the conference includes discussion panels or forums, participate actively. Sharing your insights can help you connect with others who share your interests.

11. Attend Workshops and Symposia: Workshops and symposia are great places to meet like-minded researchers. Engage in discussions, ask questions, and explore potential collaborations.

12. Follow Up After the Conference: After the conference concludes, follow up with individuals you met. Send personalized emails expressing your interest in continuing the conversation or collaborating on research projects.

13. Use Conference Apps: Many conferences offer dedicated apps or platforms for networking. Utilize these tools to identify potential contacts, send messages, and arrange meetings.

14. Seek Mentorship: If you admire the work of senior researchers or experts in your field, don't hesitate to express your interest in their work and seek mentorship. Many established researchers are open to mentoring younger scholars.

15. Be Respectful of Time: While networking, be mindful of attendees' time constraints. Respect their schedules and offer to continue discussions at a later time if necessary.

Networking during a poster presentation extends beyond the event itself. The connections you establish can lead to collaborations, research opportunities, and professional growth. Approach networking with an open and enthusiastic attitude, and you'll discover the vast potential for building meaningful relationships within your academic and professional community.

Mastering the art of effective poster presentations at conferences is a valuable skill for any researcher. By focusing on clear design, engaging content, practiced delivery, and active engagement with your audience, you can make the most of this platform to share your research, connect with peers, and contribute to the vibrant academic community that conferences offer.

Connect With Us

Dissertation Editing and Proofreading Services Discount (New for 2018)

May 3, 2017.

For March through May 2018 ONLY, our professional dissertation editing se...

Thesis Editing and Proofreading Services Discount (New for 2018)

For March through May 2018 ONLY, our thesis editing service is discounted...

Neurology includes Falcon Scientific Editing in Professional Editing Help List

March 14, 2017.

Neurology Journal now includes Falcon Scientific Editing in its Professio...

Useful Links

Academic Editing | Thesis Editing | Editing Certificate | Resources

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 25 January 2021

The ABCs of academic poster presentation

- Tulsi Patel 1

BDJ Student volume 28 , pages 14–16 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

72 Accesses

1 Citations

Metrics details

Tulsi Patel , DCT1, Royal London Hospital, Barts NHS Trust

Academic posters are an excellent way to summarise and display your work

It is important to read the conference requirements carefully before preparing your poster

Adopt a clear, concise and easy to follow design

Preparing the poster in advance, practising your presentation and formulating answers to anticipated questions is essential

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

We are sorry, but there is no personal subscription option available for your country.

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Hamilton C. At a Glance: A Stepwise Approach to Successful Poster Presentations. Chest 2008; 134 : 457-459.

Daud D. How to make a scientific poster: a guide for medical students. Available from: http://cures.cardiff.ac.uk/files/2014/10/NSAMR-Poster.pdf (Accessed October 2020).

Birmingham.ac.uk. Tips for effective poster design. 2020. Available from: https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/schools/metallurgy-materials/about/cases/tips-advice/poster.aspx (Accessed October 2020).

Sousa B, Clark A. Six Insights to Make Better Academic Conference Posters. Int J Qual Methods 2019; 18 : 160940691986237.

Rossi T. How to Design an Award-Winning Conference Poster. 2018. Available from: https://www.animateyour.science/post/how-to-design-an-award-winning-conference-poster (Accessed October 2020).

Gundogan B, Koshy K, Kurar L, Whitehurst K. How to make an academic poster. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2016; 11 : 69-71.

Shelledy D. How to make an effective poster. Respiratory Care 2004; 49 : 1214.

Wolfrom J. The magical effects of color. Lafayette, Calif. C & T Pub. 2009.

Beamish A, Ansell J, Foster J, Foster K, Egan R. Poster Exhibitions at Conferences: Are We Doing it Properly? J Surg Educ 2015; 72 : 278-282.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Royal London Hospital, Whitechapel Road, E1 1FR, London, UK

Tulsi Patel

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Tulsi Patel .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Patel, T. The ABCs of academic poster presentation. BDJ Student 28 , 14–16 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41406-020-0173-3

Download citation

Published : 25 January 2021

Issue Date : January 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41406-020-0173-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

A graduate student’s mentorship pedagogy for undergraduate mentees.

- Meghan E. Fallon

Biomedical Engineering Education (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Beyond the Podium: Understanding the differences in conference and academic presentations

Conferences can be captivating as it where knowledge meets presentation skills. They serve as dynamic platforms where scholars, researchers, and professionals interact to share insights, exchange ideas, and foster collaboration. The importance of conferences lies in their ability to nurture intellectual growth, stimulate discussions, and propel academic advancements. Let’s uncover the intricacies of various conference presentations to help you shine in the academic spotlight.

The Multi-faceted Nature of Conference

Conference is a broad term that encompasses various professional/ academic events. As we delve deeper into such events, we encounter different types of conferences, each serving a specific purpose. Common types of conferences include Business Conferences, Academic Conferences, Educational Conferences, Scientific Conferences, Social/ Cultural Conferences, Peace Conferences, Trade Conferences, Press or News Conferences, and Authors’ Conferences.

In addition to the different types of conferences, there are several types of conference presentations. Understanding them is important to make the right presentation for a conference before submitting your abstract.

Types of Conference Presentations

Here are the commonly used formats for conference presentations:

1. Oral Presentation

Oral presentations are the standard form of presentation where the speaker(s) share details about their research questions , methodology , findings, applications, etc. It lasts between 15-30 minutes. Oral presentations can be further divided into four subtypes:

1.1. Student Presentation:

These presentations emphasize on students work and offer them an opportunity to share their work with the academic community.

1.2. Panel Discussion:

Panel discussions are delivered by a panel of speakers who share different aspects of the presentations. Furthermore, such events are generally more open and characterized by engaging discussions.

2. Poster Presentation

Poster presentations are less formal platforms to share your work in a visual format. Presenters summarize their work in a visually appealing poster and display them for the attendees to understand.

Both oral and poster presentations serve as integral components of conferences, catering to different learning preferences and promoting the exchange of knowledge among researchers and professionals in diverse fields.

However, based on the difference in the content, and the intended audience, conference presentations can be divided as:

1. Academic Presentations

Academic presentations at conferences are the bedrock of knowledge dissemination. They showcase research findings, theories, and contribute to the collective intellectual discourse.

- General Elements : Title and Authorship, Introduction , Objectives/ Hypothesis, Methodology, Results, Discussion, Conclusion, and Recommendations

- Who Presents: Researchers, Scholars, Academics, Graduate Students, and Professionals

- For Whom: Peers, Fellow Researchers, Scholars, Academics, Professionals, Reviewers, and Critics

2. Research Presentations

Research presentations delve into the specifics of a study, highlighting methodologies, results, and implications. Additionally, they bridge the gap between theory and practical application, offering a comprehensive view of the research process.

- General Elements: Title Slide, Introduction, Objectives/ Hypothesis , Literature Review , Research Design and Methodology, Results, Discussion, Conclusion, and Recommendations

- Who Presents: Researchers or Scholars who conducted the study, Primary Author(s), Principal Investigator, Graduate Students, and Collaborators

- For Whom: Peers and Colleagues, Academic Community, Reviewers and Assessors, Industry Professionals, Policy Makers and Practitioners, and Funding Agencies

3. Grant Proposal Presentations

These presentations aim to convince funding bodies about the significance and viability of a proposed project. However, they require a blend of persuasive communication and a clear articulation of the project’s objectives and potential impact.

- General Elements: Introduction, Background and Rationale , Objectives and Goals, Methods and Approach, Timeline, Budget, Evaluation and Metrics, Sustainability and Long-term Impact, Collaborations and Partnerships, Team Qualifications and Expertise, Plan of Action, and Challenges and Mitigation Strategies

- Who Presents: Principal Investigator, Co-Investigators or Collaborators, Project Team Members, Institutional Representatives, Community or Stakeholder Representatives, and Advisors or Mentors (for Students)

- For Whom: Granting Organization Representatives, Review Committee or Panel, Advisory Board, Potential Collaborators or Partners, Community Stakeholders, Internal Team or Collaborators, and Public or Lay Audience (Rarely)

4. Thesis Presentations

Thesis presentations mark the culmination of academic endeavors. They involve presenting the key findings and contributions of a research project undertaken for a degree, providing an opportunity for peers and experts to evaluate the work.

- General Elements: Title Slide, Author’s Name and Affiliation, Date of the Presentation, Introduction, Background and Context, Research Objectives and Hypotheses, Methodology, Results, Discussion , Contribution to the Field, Limitations, Conclusion, Recommendations for Future Research, and References

- Who Presents: Thesis Candidate (Student), Thesis Committee, and Thesis Advisor (Supervisor)

- For Whom: Instructors and Evaluators, Peers and Classmates, Academic Community, and Reviewers

Understanding different types of presentations in conferences can empower researchers to make appropriate presentations that meets the requirement of the conference. However, to make your presentations more interactive, here is a downloadable guide with specific tips for conference presentations .

Making each presentation type distinct involves tailoring your approach based on the purpose, audience, and format of the presentation. To maximize your conference experience, consider participating in interactive sessions and networking with the other participants . Engage with your peers, ask questions, and embrace the collaborative spirit that conferences embody.

The diverse array of conference presentations creates a vibrant tapestry of knowledge sharing. Each format offers a unique avenue for researchers and professionals to showcase their work and connect with a broader audience. So, whether you find yourself behind a podium or beside a poster board, remember that the power of conferences lies in the collective exchange of ideas, where each presenter and attendee contributes to the saga of knowledge and discovery.

Frequently Asked Questions

Creating a successful conference presentation involves careful planning, organization, and effective communication. Here are steps to guide you through the process: 1. Understand Your Audience 2. Define Your Objectives 3. Understand the conference type 4. Create a Clear Structure 5. Craft Engaging Content 6. Practice Time Management 7. Prepare for Q&A

An academic presentation is a formal communication of research findings, scholarly work, or educational content delivered to an audience within an academic or professional setting. These presentations occur in various formats, such as lectures, seminars, workshops, or conference sessions, and they serve the purpose of sharing knowledge, insights, and research outcomes with peers, students, or other members of the academic community. Academic presentations can cover a wide range of topics, including research methodologies, experimental results, literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and educational practices.

A conference presentation is a formal communication delivered at a conference, seminar, symposium, or similar academic or professional gathering. These presentations serve as a means for researchers, scholars, professionals, and experts to share their work, findings, and insights with a wider audience. Conference presentations cover a diverse range of topics, including research studies, case analyses, theoretical frameworks, and practical applications within various fields. They play a crucial role in the advancement of academic and professional fields by facilitating the exchange of ideas, fostering collaboration, and showcasing the latest research and developments in a given area of study.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

Achieving Research Excellence: Checklist for good research practices

Academia is built on the foundation of trustworthy and high-quality research, supported by the pillars…

- Reporting Research

Digital Citations: A comprehensive guide to citing of websites in APA, MLA, and CMOS style

In today’s digital age, the internet serves as an invaluable resource for researchers across all…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for data interpretation

In research, choosing the right approach to understand data is crucial for deriving meaningful insights.…

- Career Corner

Unlocking the Power of Networking in Academic Conferences

Embarking on your first academic conference experience? Fear not, we got you covered! Academic conferences…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Research recommendations play a crucial role in guiding scholars and researchers toward fruitful avenues of…

Digital Citations: A comprehensive guide to citing of websites in APA, MLA, and CMOS…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for…

8 Effective Strategies to Write Argumentative Essays

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

When should AI tools be used in university labs?

- Schools & departments

Presentations and posters

Guidance and tips for effective oral and visual presentations.

Academic presentations

Presenting your work allows you to demonstrate your knowledge and familiarity of your subject. Presentations can vary from being formal, like a mini lecture, to more informal, such as summarising a paper in a tutorial. You may have a specialist audience made up of your peers, lecturers or research practitioners or a wider audience at a conference or event. Sometimes you will be asked questions. Academic presentations maybe a talk with slides or a poster presentation, and they may be assessed. Presentations may be individual or collaborative group work.