How COVID-19 pandemic changed my life

Table of Contents

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is one of the biggest challenges that our world has ever faced. People around the globe were affected in some way by this terrible disease, whether personally or not. Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, many people felt isolated and in a state of panic. They often found themselves lacking a sense of community, confidence, and trust. The health systems in many countries were able to successfully prevent and treat people with COVID-19-related diseases while providing early intervention services to those who may not be fully aware that they are infected (Rume & Islam, 2020). Personally, this pandemic has brought numerous changes and challenges to my life. The COVID-19 pandemic affected my social, academic, and economic lifestyle positively and negatively.

Social and Academic Changes

One of the changes brought by the pandemic was economic changes that occurred very drastically (Haleem, Javaid, & Vaishya, 2020). During the pandemic, food prices started to rise, affecting the amount of money my parents could spend on goods and services. We had to reduce the food we bought as our budgets were stretched. My family also had to eliminate unhealthy food bought in bulk, such as crisps and chocolate bars. Furthermore, the pandemic made us more aware of the importance of keeping our homes clean, especially regarding cooking food. Lastly, it also made us more aware of how we talked to other people when they were ill and stayed home with them rather than being out and getting on with other things.

Furthermore, COVID-19 had a significant effect on my academic life. Immediately, measures to curb the pandemic were announced, such as closing all learning institutions in the country; my school life changed. The change began when our school implemented the online education system to ensure that we continued with our education during the lockdown period. At first, this affected me negatively because when learning was not happening in a formal environment, I struggled academically since I was not getting the face-to-face interaction with the teachers I needed. Furthermore, forcing us to attend online caused my classmates and me to feel disconnected from the knowledge being taught because we were unable to have peer participation in class. However, as the pandemic subsided, we grew accustomed to this learning mode. We realized the effects on our performance and learning satisfaction were positive, as it seemed to promote emotional and behavioral changes necessary to function in a virtual world. Students who participated in e-learning during the pandemic developed more ownership of the course requirement, increased their emotional intelligence and self-awareness, improved their communication skills, and learned to work together as a community.

If there is an area that the pandemic affected was the mental health of my family and myself. The COVID-19 pandemic caused increased anxiety, depression, and other mental health concerns that were difficult for my family and me to manage alone. Our ability to learn social resilience skills, such as self-management, was tested numerous times. One of the most visible challenges we faced was social isolation and loneliness. The multiple lockdowns made it difficult to interact with my friends and family, leading to loneliness. The changes in communication exacerbated the problem as interactions moved from face-to-face to online communication using social media and text messages. Furthermore, having family members and loved ones separated from us due to distance, unavailability of phones, and the internet created a situation of fear among us, as we did not know whether they were all right. Moreover, some people within my circle found it more challenging to communicate with friends, family, and co-workers due to poor communication skills. This was mainly attributed to anxiety or a higher risk of spreading the disease. It was also related to a poor understanding of creating and maintaining relationships during this period.

Positive Changes

In addition, this pandemic has brought some positive changes with it. First, it had been a significant catalyst for strengthening relationships and neighborhood ties. It has encouraged a sense of community because family members, neighbors, friends, and community members within my area were all working together to help each other out. Before the pandemic, everybody focused on their business, the children going to school while the older people went to work. There was not enough time to bond with each other. Well, the pandemic changed that, something that has continued until now that everything is returning to normal. In our home, it strengthened the relationship between myself and my siblings and parents. This is because we started spending more time together as a family, which enhanced our sense of understanding of ourselves.

The pandemic has been a challenging time for many people. I can confidently state that it was a significant and potentially unprecedented change in our daily life. By changing how we do things and relate with our family and friends, the pandemic has shaped our future life experiences and shown that during crises, we can come together and make a difference in each other’s lives. Therefore, I embrace wholesomely the changes brought by the COVID-19 pandemic in my life.

- Haleem, A., Javaid, M., & Vaishya, R. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 pandemic in daily life. Current medicine research and practice , 10 (2), 78.

- Rume, T., & Islam, S. D. U. (2020). Environmental effects of COVID-19 pandemic and potential strategies of sustainability. Heliyon , 6 (9), e04965.

- ☠️ Assisted Suicide

- Affordable Care Act

- Breast Cancer

- Genetic Engineering

- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- 2024 election

- TikTok’s fate

- Supreme Court

- Winter warming

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

Artists, novelists, critics, and essayists are writing the first draft of history.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66606035/1207638131.jpg.0.jpg)

The world is grappling with an invisible, deadly enemy, trying to understand how to live with the threat posed by a virus . For some writers, the only way forward is to put pen to paper, trying to conceptualize and document what it feels like to continue living as countries are under lockdown and regular life seems to have ground to a halt.

So as the coronavirus pandemic has stretched around the world, it’s sparked a crop of diary entries and essays that describe how life has changed. Novelists, critics, artists, and journalists have put words to the feelings many are experiencing. The result is a first draft of how we’ll someday remember this time, filled with uncertainty and pain and fear as well as small moments of hope and humanity.

At the New York Review of Books, Ali Bhutto writes that in Karachi, Pakistan, the government-imposed curfew due to the virus is “eerily reminiscent of past military clampdowns”:

Beneath the quiet calm lies a sense that society has been unhinged and that the usual rules no longer apply. Small groups of pedestrians look on from the shadows, like an audience watching a spectacle slowly unfolding. People pause on street corners and in the shade of trees, under the watchful gaze of the paramilitary forces and the police.

His essay concludes with the sobering note that “in the minds of many, Covid-19 is just another life-threatening hazard in a city that stumbles from one crisis to another.”

Writing from Chattanooga, novelist Jamie Quatro documents the mixed ways her neighbors have been responding to the threat, and the frustration of conflicting direction, or no direction at all, from local, state, and federal leaders:

Whiplash, trying to keep up with who’s ordering what. We’re already experiencing enough chaos without this back-and-forth. Why didn’t the federal government issue a nationwide shelter-in-place at the get-go, the way other countries did? What happens when one state’s shelter-in-place ends, while others continue? Do states still under quarantine close their borders? We are still one nation, not fifty individual countries. Right?

Award-winning photojournalist Alessio Mamo, quarantined with his partner Marta in Sicily after she tested positive for the virus, accompanies his photographs in the Guardian of their confinement with a reflection on being confined :

The doctors asked me to take a second test, but again I tested negative. Perhaps I’m immune? The days dragged on in my apartment, in black and white, like my photos. Sometimes we tried to smile, imagining that I was asymptomatic, because I was the virus. Our smiles seemed to bring good news. My mother left hospital, but I won’t be able to see her for weeks. Marta started breathing well again, and so did I. I would have liked to photograph my country in the midst of this emergency, the battles that the doctors wage on the frontline, the hospitals pushed to their limits, Italy on its knees fighting an invisible enemy. That enemy, a day in March, knocked on my door instead.

In the New York Times Magazine, deputy editor Jessica Lustig writes with devastating clarity about her family’s life in Brooklyn while her husband battled the virus, weeks before most people began taking the threat seriously:

At the door of the clinic, we stand looking out at two older women chatting outside the doorway, oblivious. Do I wave them away? Call out that they should get far away, go home, wash their hands, stay inside? Instead we just stand there, awkwardly, until they move on. Only then do we step outside to begin the long three-block walk home. I point out the early magnolia, the forsythia. T says he is cold. The untrimmed hairs on his neck, under his beard, are white. The few people walking past us on the sidewalk don’t know that we are visitors from the future. A vision, a premonition, a walking visitation. This will be them: Either T, in the mask, or — if they’re lucky — me, tending to him.

Essayist Leslie Jamison writes in the New York Review of Books about being shut away alone in her New York City apartment with her 2-year-old daughter since she became sick:

The virus. Its sinewy, intimate name. What does it feel like in my body today? Shivering under blankets. A hot itch behind the eyes. Three sweatshirts in the middle of the day. My daughter trying to pull another blanket over my body with her tiny arms. An ache in the muscles that somehow makes it hard to lie still. This loss of taste has become a kind of sensory quarantine. It’s as if the quarantine keeps inching closer and closer to my insides. First I lost the touch of other bodies; then I lost the air; now I’ve lost the taste of bananas. Nothing about any of these losses is particularly unique. I’ve made a schedule so I won’t go insane with the toddler. Five days ago, I wrote Walk/Adventure! on it, next to a cut-out illustration of a tiger—as if we’d see tigers on our walks. It was good to keep possibility alive.

At Literary Hub, novelist Heidi Pitlor writes about the elastic nature of time during her family’s quarantine in Massachusetts:

During a shutdown, the things that mark our days—commuting to work, sending our kids to school, having a drink with friends—vanish and time takes on a flat, seamless quality. Without some self-imposed structure, it’s easy to feel a little untethered. A friend recently posted on Facebook: “For those who have lost track, today is Blursday the fortyteenth of Maprilay.” ... Giving shape to time is especially important now, when the future is so shapeless. We do not know whether the virus will continue to rage for weeks or months or, lord help us, on and off for years. We do not know when we will feel safe again. And so many of us, minus those who are gifted at compartmentalization or denial, remain largely captive to fear. We may stay this way if we do not create at least the illusion of movement in our lives, our long days spent with ourselves or partners or families.

Novelist Lauren Groff writes at the New York Review of Books about trying to escape the prison of her fears while sequestered at home in Gainesville, Florida:

Some people have imaginations sparked only by what they can see; I blame this blinkered empiricism for the parks overwhelmed with people, the bars, until a few nights ago, thickly thronged. My imagination is the opposite. I fear everything invisible to me. From the enclosure of my house, I am afraid of the suffering that isn’t present before me, the people running out of money and food or drowning in the fluid in their lungs, the deaths of health-care workers now growing ill while performing their duties. I fear the federal government, which the right wing has so—intentionally—weakened that not only is it insufficient to help its people, it is actively standing in help’s way. I fear we won’t sufficiently punish the right. I fear leaving the house and spreading the disease. I fear what this time of fear is doing to my children, their imaginations, and their souls.

At ArtForum , Berlin-based critic and writer Kristian Vistrup Madsen reflects on martinis, melancholia, and Finnish artist Jaakko Pallasvuo’s 2018 graphic novel Retreat , in which three young people exile themselves in the woods:

In melancholia, the shape of what is ending, and its temporality, is sprawling and incomprehensible. The ambivalence makes it hard to bear. The world of Retreat is rendered in lush pink and purple watercolors, which dissolve into wild and messy abstractions. In apocalypse, the divisions established in genesis bleed back out. My own Corona-retreat is similarly soft, color-field like, each day a blurred succession of quarantinis, YouTube–yoga, and televized press conferences. As restrictions mount, so does abstraction. For now, I’m still rooting for love to save the world.

At the Paris Review , Matt Levin writes about reading Virginia Woolf’s novel The Waves during quarantine:

A retreat, a quarantine, a sickness—they simultaneously distort and clarify, curtail and expand. It is an ideal state in which to read literature with a reputation for difficulty and inaccessibility, those hermetic books shorn of the handholds of conventional plot or characterization or description. A novel like Virginia Woolf’s The Waves is perfect for the state of interiority induced by quarantine—a story of three men and three women, meeting after the death of a mutual friend, told entirely in the overlapping internal monologues of the six, interspersed only with sections of pure, achingly beautiful descriptions of the natural world, a day’s procession and recession of light and waves. The novel is, in my mind’s eye, a perfectly spherical object. It is translucent and shimmering and infinitely fragile, prone to shatter at the slightest disturbance. It is not a book that can be read in snatches on the subway—it demands total absorption. Though it revels in a stark emotional nakedness, the book remains aloof, remote in its own deep self-absorption.

In an essay for the Financial Times, novelist Arundhati Roy writes with anger about Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s anemic response to the threat, but also offers a glimmer of hope for the future:

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.

From Boston, Nora Caplan-Bricker writes in The Point about the strange contraction of space under quarantine, in which a friend in Beirut is as close as the one around the corner in the same city:

It’s a nice illusion—nice to feel like we’re in it together, even if my real world has shrunk to one person, my husband, who sits with his laptop in the other room. It’s nice in the same way as reading those essays that reframe social distancing as solidarity. “We must begin to see the negative space as clearly as the positive, to know what we don’t do is also brilliant and full of love,” the poet Anne Boyer wrote on March 10th, the day that Massachusetts declared a state of emergency. If you squint, you could almost make sense of this quarantine as an effort to flatten, along with the curve, the distinctions we make between our bonds with others. Right now, I care for my neighbor in the same way I demonstrate love for my mother: in all instances, I stay away. And in moments this month, I have loved strangers with an intensity that is new to me. On March 14th, the Saturday night after the end of life as we knew it, I went out with my dog and found the street silent: no lines for restaurants, no children on bicycles, no couples strolling with little cups of ice cream. It had taken the combined will of thousands of people to deliver such a sudden and complete emptiness. I felt so grateful, and so bereft.

And on his own website, musician and artist David Byrne writes about rediscovering the value of working for collective good , saying that “what is happening now is an opportunity to learn how to change our behavior”:

In emergencies, citizens can suddenly cooperate and collaborate. Change can happen. We’re going to need to work together as the effects of climate change ramp up. In order for capitalism to survive in any form, we will have to be a little more socialist. Here is an opportunity for us to see things differently — to see that we really are all connected — and adjust our behavior accordingly. Are we willing to do this? Is this moment an opportunity to see how truly interdependent we all are? To live in a world that is different and better than the one we live in now? We might be too far down the road to test every asymptomatic person, but a change in our mindsets, in how we view our neighbors, could lay the groundwork for the collective action we’ll need to deal with other global crises. The time to see how connected we all are is now.

The portrait these writers paint of a world under quarantine is multifaceted. Our worlds have contracted to the confines of our homes, and yet in some ways we’re more connected than ever to one another. We feel fear and boredom, anger and gratitude, frustration and strange peace. Uncertainty drives us to find metaphors and images that will let us wrap our minds around what is happening.

Yet there’s no single “what” that is happening. Everyone is contending with the pandemic and its effects from different places and in different ways. Reading others’ experiences — even the most frightening ones — can help alleviate the loneliness and dread, a little, and remind us that what we’re going through is both unique and shared by all.

Will you help keep Vox free for all?

At Vox, we believe that clarity is power, and that power shouldn’t only be available to those who can afford to pay. That’s why we keep our work free. Millions rely on Vox’s clear, high-quality journalism to understand the forces shaping today’s world. Support our mission and help keep Vox free for all by making a financial contribution to Vox today.

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Next Up In Culture

Sign up for the newsletter today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

Thanks for signing up!

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

3 reasons why Kate Middleton’s royal scandal got so out of control

Fani Willis’s Trump prosecution can move forward — if she drops her ex from the case

Why abortion politics might not carry Democrats again in 2024

This AI says it has feelings. It’s wrong. Right?

How to think about Boeing’s recent safety issues

How the world has radically cut child deaths, in one chart

Two Years In: How the Pandemic Changed Our Lives

From remote work to major life developments, the COVID-19 era left its mark on Duke staff and faculty

- Share this story on facebook

- Share this story on twitter

- Share this story on reddit

- Share this story on linkedin

- Get this story's permalink

- Print this story

Two years ago this week, the novel coronavirus fully took hold in the United States. While it had been in the country earlier, the second week of March 2020 was when cases spiked, and soon after, Duke University President Vincent E. Price announced in an “urgent message” that faculty and staff who could work from home should do so.

Masking and social distancing policies became the norm while businesses, schools and offices went quiet.

As some safety measures ease , COVID-19 has infected nearly 80 million Americans and left nearly 970,000 dead. As the pandemic raged with variants, education, research and health care continued across Duke University and Duke University Health System at a high level.

And many of us are forever changed.

“I think we, as a people, are different,” said Duke Associate Professor of Medicine Jon Bae, a co-convener for the mental and emotional well-being portion of Healthy Duke. “In the last two years, people have learned different ways of working, different ways of living and different ways to take appreciation for things.”

Jon Boylan is one of those.

The past two years have drawn Boylan closer to his wife, Katie, a steadying influence during uncertain times. But starting a family against the backdrop of a global pandemic has given him a deeper respect for how forces outside of our control can alter plans.

“I wasn’t one of those people who had time to learn how to bake bread or anything,” Boylan said. “But I think in terms of personal growth, a lot happened.”

We caught up with some Duke colleagues to hear how their lives are different two years into the pandemic.

Committing to Self-Care

“For me, I thought, ‘How do I have a rich, full life amid all of this and keep a positive attitude?’” Thomas said.

She decided that she needed a goal that she could work toward until the world opened up. Already with a long list of outdoors adventures under her belt, Thomas decided to plan a summer 2021 trip to Nepal to hike the summit of the 21,247-foot Mera Peak.

For the next several months, Thomas began running, working out at a socially distanced gym, and incorporating as many walks as possible into her day. While the trip to Nepal was the goal, the exercise to prepare for it became a central piece of her self-care routine.

“I just love being outside, it’s very restorative,” Thomas said. “And I like physical challenges, I get the rush of endorphins from that. So putting those two things together just helps me out mentally. Even just a short walk can help me focus.”

Eventually, travel complications required Thomas to postpone the trip to Nepal. Instead, she flew to Spain and, over three weeks in September and October of 2021, she hiked 335 miles on the Camino de Santiago pilgrim trail.

“It was basically like a walking meditation for three weeks,” said Thomas, who is now exercising with an eye toward a 2023 Nepal trip. “It’s really an incredible experience.”

Defining Your Purpose

But she said COVID-19 tested everyone’s resolve.

“You just don’t know how you’re going to react to something until you’re in it,” Casey said.

In March 2020, Casey was the clinical team lead for Duke Raleigh’s ICU, a managerial role with less hands-on patient care. But it wasn’t far into the pandemic before Casey’s desire to help patients led her to return to a clinical nurse role.

There, she saw the virus’ danger up close. At one point in the summer of 2020, 13 of the 15 beds in the ICU were occupied by COVID-19 patients on ventilators. With no visitors allowed for COVID-19 patients, Casey witnessed several wrenching goodbyes said over cellphone.

Her challenges didn’t end when she left work. With four children and a husband who’s a police officer in Durham, at home, Casey faced stress from home schooling and a spouse also on COVID-19’s front lines.

While many ICU nurses ask to be transferred to different units due to the emotional strain, Casey was inspired by seeing colleagues bravely push forward, giving comfort and dignity to patients facing dire situations. She also said that, as the pandemic wore on, the bond between ICU nurses grew stronger.

As hard as these past two years have been, Casey, who still serves in the ICU and recently began working toward an Acute Care Nurse Practitioner certificate through the Duke University School of Nursing , said the pandemic experience has only deepened her connection to her work.

“We all faced this as a challenge, personally, emotionally and professionally, and hopefully learned to grow through it and be better if this ever happens again,” Casey said.

Taking Charge of Physical Health

After the pandemic required many Duke staff and faculty members to work remotely , sending Carbuccia from working in the bustling Smith Warehouse to his Mebane home, the IT Analyst with Duke’s Office of Information Technology found himself making healthier choices without even thinking.

Instead of eating lunch out or grabbing meals from events in his on-campus workspace, Carbuccia found himself eating homemade breakfasts, lunches and dinners. Scrambled eggs with vegetables, or simply prepared salmon filets are some of current favorites.

And without a commute, he has time for walks around his neighborhood before and after work.

Carbuccia saw the result of these changes a few months into the pandemic when he stepped on the scale and saw that he’d lost 26 pounds.

“When I stepped on the scale, I said, ‘Holy Moses! I lost a lot of weight, and I wasn’t even planning to!’” Carbuccia said.

A Better Mental Space

And each day also involved a roughly 30-minute commute along I-85 to her home in Graham, where the heavy traffic made her feel especially anxious, leaving her tense when she arrived at work or home.

But the past two years saw her work go fully remote, and now a move to a hybrid arrangement featuring one day of on-site each week. She cherishes the time she can spend working from home, often with her two dogs – Marx, a Boston Terrier, and Duke, a rescue – lounging at her feet.

“Working at home, I feel like my mental health is in a better place,” said Herrera, a wife and mother of three.

Herrera isn’t alone in her appreciation of remote work. According to a Pew Research Center report from February 2022, approximately six in 10 workers who can do their jobs from home are working remotely most or all of the time.

Herrera said her hybrid schedule leaves her feeling mentally fresh when she begins her workday and better able to transition between work and personal life.

“I’m happier,” Herrera said. “I’m more at ease.”

Learning on the Fly

“Even though some of us had experience working remotely, it was still new,” said Roberts, who’s worked at Duke for nearly a decade. “Regardless of how much experience you had, I don’t think we were mentally or technologically ready for that quick of a transition.”

Roberts recalls PRMO leaders moving quickly to get desktops, monitors, laptops, cameras and headsets in the hands of team members. She also recalls many of her colleagues working diligently to familiarize themselves with new tools and programs, such as the collaboration platform Jabber, that were different from what was used in the PRMO offices on South Alston Avenue in Durham.

Roberts and her colleagues also had to learn how to collaborate with one another when communication came by email and chat messages instead of a quick face-to-face conversation.

Working each day from her home in Franklinton, Roberts continues to help Duke Health patients with billing concerns. She’s part of a large team that gelled amid the pandemic and kept the pace of customer support high.

With PRMO keeping colleagues connected with department meetings and team-building Zoom events, Roberts said these past two years have given her a new appreciation of the resilience of her colleagues.

“It made me proud because nobody skipped a beat,” Roberts said. “Everybody took accountability. While some of our thinking and the logic behind how we normally do things had to change, I’m proud that it was still a really seamless transition for us.”

Finding Flexibility

“This is something that would have never happened before the pandemic,” said Atkinson, a regulatory coordinator with the Duke Department of Surgery .

Like many administrators in Duke’s research areas, Atkinson has been working fully remote since the pandemic began, trading in her fourth-floor workspace in Erwin Terrace for a spot at home. The change reshaped Atkinson’s day-to-day routine in a drastic way, ridding her of a commute that ate up two hours each day.

Now, with more time to spend with her son, West, born before the pandemic, and her 10-month-old daughter, Iris, Atkinson, who has worked for Duke for nearly seven years, has the flexibility that allows her to feel rooted. And with more balance, she hopes to let the roots of her family, as well as the cucumbers, tomatoes and peppers that will be in the ground soon, grow strong.

“I’ve attempted a very small garden each year, but we have a very shady lot,” Atkinson said. “But this year, we’re putting it in the front, where we get a lot of sun, and West is helping me, so it’s going to work.”

A World of Change

In late 2019, she met Neil Gallagher at a party and hit it off. The pair dated for the next few months and, when the pandemic forced everyone to limit contact with others, they decided to keep each other in their quarantine bubble.

“It was one of those easy connections where we were really comfortable with each other,” said Meyer, who shared the story of her mental health journey with Working@Duke just before the coronavirus outbreak.

Over the next several months, the pair grew closer and, by the end of 2020, they’d begun talking about getting engaged and starting a family. Those plans hit warp speed when they found out Meyer was pregnant in early 2021. Not long after, they were engaged and later married in a small ceremony in Raleigh in July of last year.

And over a few hectic days in early October, the pair closed on a house together in Raleigh and Meyer gave birth to a healthy baby girl named Maggie.

Now in a very different spot in life from where she was when the pandemic began, Meyer said she greets each day with a new feeling of purpose and strong sense of gratitude.

“I think my husband and I have been keenly aware of how odd it’s been and how many blessing we’ve had at a time when life has been really hard for a lot of people,” Meyer said.

How has the pandemic changed your life? Send us your story and photographs through our story idea form or write [email protected] .

Follow Working@Duke on Twitter and Facebook .

Link to this page

Copy and paste the URL below to share this page.

I Thought We’d Learned Nothing From the Pandemic. I Wasn’t Seeing the Full Picture

M y first home had a back door that opened to a concrete patio with a giant crack down the middle. When my sister and I played, I made sure to stay on the same side of the divide as her, just in case. The 1988 film The Land Before Time was one of the first movies I ever saw, and the image of the earth splintering into pieces planted its roots in my brain. I believed that, even in my own backyard, I could easily become the tiny Triceratops separated from her family, on the other side of the chasm, as everything crumbled into chaos.

Some 30 years later, I marvel at the eerie, unexpected ways that cartoonish nightmare came to life – not just for me and my family, but for all of us. The landscape was already covered in fissures well before COVID-19 made its way across the planet, but the pandemic applied pressure, and the cracks broke wide open, separating us from each other physically and ideologically. Under the weight of the crisis, we scattered and landed on such different patches of earth we could barely see each other’s faces, even when we squinted. We disagreed viciously with each other, about how to respond, but also about what was true.

Recently, someone asked me if we’ve learned anything from the pandemic, and my first thought was a flat no. Nothing. There was a time when I thought it would be the very thing to draw us together and catapult us – as a capital “S” Society – into a kinder future. It’s surreal to remember those early days when people rallied together, sewing masks for health care workers during critical shortages and gathering on balconies in cities from Dallas to New York City to clap and sing songs like “Yellow Submarine.” It felt like a giant lightning bolt shot across the sky, and for one breath, we all saw something that had been hidden in the dark – the inherent vulnerability in being human or maybe our inescapable connectedness .

More from TIME

Read More: The Family Time the Pandemic Stole

But it turns out, it was just a flash. The goodwill vanished as quickly as it appeared. A couple of years later, people feel lied to, abandoned, and all on their own. I’ve felt my own curiosity shrinking, my willingness to reach out waning , my ability to keep my hands open dwindling. I look out across the landscape and see selfishness and rage, burnt earth and so many dead bodies. Game over. We lost. And if we’ve already lost, why try?

Still, the question kept nagging me. I wondered, am I seeing the full picture? What happens when we focus not on the collective society but at one face, one story at a time? I’m not asking for a bow to minimize the suffering – a pretty flourish to put on top and make the whole thing “worth it.” Yuck. That’s not what we need. But I wondered about deep, quiet growth. The kind we feel in our bodies, relationships, homes, places of work, neighborhoods.

Like a walkie-talkie message sent to my allies on the ground, I posted a call on my Instagram. What do you see? What do you hear? What feels possible? Is there life out here? Sprouting up among the rubble? I heard human voices calling back – reports of life, personal and specific. I heard one story at a time – stories of grief and distrust, fury and disappointment. Also gratitude. Discovery. Determination.

Among the most prevalent were the stories of self-revelation. Almost as if machines were given the chance to live as humans, people described blossoming into fuller selves. They listened to their bodies’ cues, recognized their desires and comforts, tuned into their gut instincts, and honored the intuition they hadn’t realized belonged to them. Alex, a writer and fellow disabled parent, found the freedom to explore a fuller version of herself in the privacy the pandemic provided. “The way I dress, the way I love, and the way I carry myself have both shrunk and expanded,” she shared. “I don’t love myself very well with an audience.” Without the daily ritual of trying to pass as “normal” in public, Tamar, a queer mom in the Netherlands, realized she’s autistic. “I think the pandemic helped me to recognize the mask,” she wrote. “Not that unmasking is easy now. But at least I know it’s there.” In a time of widespread suffering that none of us could solve on our own, many tended to our internal wounds and misalignments, large and small, and found clarity.

Read More: A Tool for Staying Grounded in This Era of Constant Uncertainty

I wonder if this flourishing of self-awareness is at least partially responsible for the life alterations people pursued. The pandemic broke open our personal notions of work and pushed us to reevaluate things like time and money. Lucy, a disabled writer in the U.K., made the hard decision to leave her job as a journalist covering Westminster to write freelance about her beloved disability community. “This work feels important in a way nothing else has ever felt,” she wrote. “I don’t think I’d have realized this was what I should be doing without the pandemic.” And she wasn’t alone – many people changed jobs , moved, learned new skills and hobbies, became politically engaged.

Perhaps more than any other shifts, people described a significant reassessment of their relationships. They set boundaries, said no, had challenging conversations. They also reconnected, fell in love, and learned to trust. Jeanne, a quilter in Indiana, got to know relatives she wouldn’t have connected with if lockdowns hadn’t prompted weekly family Zooms. “We are all over the map as regards to our belief systems,” she emphasized, “but it is possible to love people you don’t see eye to eye with on every issue.” Anna, an anti-violence advocate in Maine, learned she could trust her new marriage: “Life was not a honeymoon. But we still chose to turn to each other with kindness and curiosity.” So many bonds forged and broken, strengthened and strained.

Instead of relying on default relationships or institutional structures, widespread recalibrations allowed for going off script and fortifying smaller communities. Mara from Idyllwild, Calif., described the tangible plan for care enacted in her town. “We started a mutual-aid group at the beginning of the pandemic,” she wrote, “and it grew so quickly before we knew it we were feeding 400 of the 4000 residents.” She didn’t pretend the conditions were ideal. In fact, she expressed immense frustration with our collective response to the pandemic. Even so, the local group rallied and continues to offer assistance to their community with help from donations and volunteers (many of whom were originally on the receiving end of support). “I’ve learned that people thrive when they feel their connection to others,” she wrote. Clare, a teacher from the U.K., voiced similar conviction as she described a giant scarf she’s woven out of ribbons, each representing a single person. The scarf is “a collection of stories, moments and wisdom we are sharing with each other,” she wrote. It now stretches well over 1,000 feet.

A few hours into reading the comments, I lay back on my bed, phone held against my chest. The room was quiet, but my internal world was lighting up with firefly flickers. What felt different? Surely part of it was receiving personal accounts of deep-rooted growth. And also, there was something to the mere act of asking and listening. Maybe it connected me to humans before battle cries. Maybe it was the chance to be in conversation with others who were also trying to understand – what is happening to us? Underneath it all, an undeniable thread remained; I saw people peering into the mess and narrating their findings onto the shared frequency. Every comment was like a flare into the sky. I’m here! And if the sky is full of flares, we aren’t alone.

I recognized my own pandemic discoveries – some minor, others massive. Like washing off thick eyeliner and mascara every night is more effort than it’s worth; I can transform the mundane into the magical with a bedsheet, a movie projector, and twinkle lights; my paralyzed body can mother an infant in ways I’d never seen modeled for me. I remembered disappointing, bewildering conversations within my own family of origin and our imperfect attempts to remain close while also seeing things so differently. I realized that every time I get the weekly invite to my virtual “Find the Mumsies” call, with a tiny group of moms living hundreds of miles apart, I’m being welcomed into a pocket of unexpected community. Even though we’ve never been in one room all together, I’ve felt an uncommon kind of solace in their now-familiar faces.

Hope is a slippery thing. I desperately want to hold onto it, but everywhere I look there are real, weighty reasons to despair. The pandemic marks a stretch on the timeline that tangles with a teetering democracy, a deteriorating planet , the loss of human rights that once felt unshakable . When the world is falling apart Land Before Time style, it can feel trite, sniffing out the beauty – useless, firing off flares to anyone looking for signs of life. But, while I’m under no delusions that if we just keep trudging forward we’ll find our own oasis of waterfalls and grassy meadows glistening in the sunshine beneath a heavenly chorus, I wonder if trivializing small acts of beauty, connection, and hope actually cuts us off from resources essential to our survival. The group of abandoned dinosaurs were keeping each other alive and making each other laugh well before they made it to their fantasy ending.

Read More: How Ice Cream Became My Own Personal Act of Resistance

After the monarch butterfly went on the endangered-species list, my friend and fellow writer Hannah Soyer sent me wildflower seeds to plant in my yard. A simple act of big hope – that I will actually plant them, that they will grow, that a monarch butterfly will receive nourishment from whatever blossoms are able to push their way through the dirt. There are so many ways that could fail. But maybe the outcome wasn’t exactly the point. Maybe hope is the dogged insistence – the stubborn defiance – to continue cultivating moments of beauty regardless. There is value in the planting apart from the harvest.

I can’t point out a single collective lesson from the pandemic. It’s hard to see any great “we.” Still, I see the faces in my moms’ group, making pancakes for their kids and popping on between strings of meetings while we try to figure out how to raise these small people in this chaotic world. I think of my friends on Instagram tending to the selves they discovered when no one was watching and the scarf of ribbons stretching the length of more than three football fields. I remember my family of three, holding hands on the way up the ramp to the library. These bits of growth and rings of support might not be loud or right on the surface, but that’s not the same thing as nothing. If we only cared about the bottom-line defeats or sweeping successes of the big picture, we’d never plant flowers at all.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Why We're Spending So Much Money Now

- The Fight to Free Evan Gershkovich

- Meet the 2024 Women of the Year

- John Kerry's Next Move

- The Quiet Work Trees Do for the Planet

- Breaker Sunny Choi Is Heading to Paris

- Column: The Internet Made Romantic Betrayal Even More Devastating

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

You May Also Like

Read our research on: TikTok | Podcasts | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

In Their Own Words, Americans Describe the Struggles and Silver Linings of the COVID-19 Pandemic

The outbreak has dramatically changed americans’ lives and relationships over the past year. we asked people to tell us about their experiences – good and bad – in living through this moment in history..

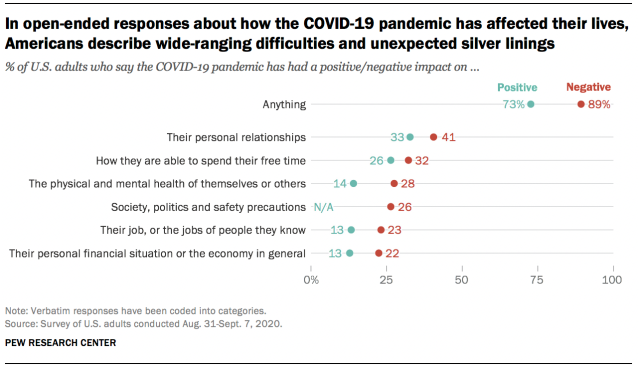

Pew Research Center has been asking survey questions over the past year about Americans’ views and reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic. In August, we gave the public a chance to tell us in their own words how the pandemic has affected them in their personal lives. We wanted to let them tell us how their lives have become more difficult or challenging, and we also asked about any unexpectedly positive events that might have happened during that time.

The vast majority of Americans (89%) mentioned at least one negative change in their own lives, while a smaller share (though still a 73% majority) mentioned at least one unexpected upside. Most have experienced these negative impacts and silver linings simultaneously: Two-thirds (67%) of Americans mentioned at least one negative and at least one positive change since the pandemic began.

For this analysis, we surveyed 9,220 U.S. adults between Aug. 31-Sept. 7, 2020. Everyone who completed the survey is a member of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

Respondents to the survey were asked to describe in their own words how their lives have been difficult or challenging since the beginning of the coronavirus outbreak, and to describe any positive aspects of the situation they have personally experienced as well. Overall, 84% of respondents provided an answer to one or both of the questions. The Center then categorized a random sample of 4,071 of their answers using a combination of in-house human coders, Amazon’s Mechanical Turk service and keyword-based pattern matching. The full methodology and questions used in this analysis can be found here.

In many ways, the negatives clearly outweigh the positives – an unsurprising reaction to a pandemic that had killed more than 180,000 Americans at the time the survey was conducted. Across every major aspect of life mentioned in these responses, a larger share mentioned a negative impact than mentioned an unexpected upside. Americans also described the negative aspects of the pandemic in greater detail: On average, negative responses were longer than positive ones (27 vs. 19 words). But for all the difficulties and challenges of the pandemic, a majority of Americans were able to think of at least one silver lining.

Both the negative and positive impacts described in these responses cover many aspects of life, none of which were mentioned by a majority of Americans. Instead, the responses reveal a pandemic that has affected Americans’ lives in a variety of ways, of which there is no “typical” experience. Indeed, not all groups seem to have experienced the pandemic equally. For instance, younger and more educated Americans were more likely to mention silver linings, while women were more likely than men to mention challenges or difficulties.

Here are some direct quotes that reveal how Americans are processing the new reality that has upended life across the country.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivered Saturday mornings

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

How to Write About Coronavirus in a College Essay

Students can share how they navigated life during the coronavirus pandemic in a full-length essay or an optional supplement.

Writing About COVID-19 in College Essays

Getty Images

Experts say students should be honest and not limit themselves to merely their experiences with the pandemic.

The global impact of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, means colleges and prospective students alike are in for an admissions cycle like no other. Both face unprecedented challenges and questions as they grapple with their respective futures amid the ongoing fallout of the pandemic.

Colleges must examine applicants without the aid of standardized test scores for many – a factor that prompted many schools to go test-optional for now . Even grades, a significant component of a college application, may be hard to interpret with some high schools adopting pass-fail classes last spring due to the pandemic. Major college admissions factors are suddenly skewed.

"I can't help but think other (admissions) factors are going to matter more," says Ethan Sawyer, founder of the College Essay Guy, a website that offers free and paid essay-writing resources.

College essays and letters of recommendation , Sawyer says, are likely to carry more weight than ever in this admissions cycle. And many essays will likely focus on how the pandemic shaped students' lives throughout an often tumultuous 2020.

But before writing a college essay focused on the coronavirus, students should explore whether it's the best topic for them.

Writing About COVID-19 for a College Application

Much of daily life has been colored by the coronavirus. Virtual learning is the norm at many colleges and high schools, many extracurriculars have vanished and social lives have stalled for students complying with measures to stop the spread of COVID-19.

"For some young people, the pandemic took away what they envisioned as their senior year," says Robert Alexander, dean of admissions, financial aid and enrollment management at the University of Rochester in New York. "Maybe that's a spot on a varsity athletic team or the lead role in the fall play. And it's OK for them to mourn what should have been and what they feel like they lost, but more important is how are they making the most of the opportunities they do have?"

That question, Alexander says, is what colleges want answered if students choose to address COVID-19 in their college essay.

But the question of whether a student should write about the coronavirus is tricky. The answer depends largely on the student.

"In general, I don't think students should write about COVID-19 in their main personal statement for their application," Robin Miller, master college admissions counselor at IvyWise, a college counseling company, wrote in an email.

"Certainly, there may be exceptions to this based on a student's individual experience, but since the personal essay is the main place in the application where the student can really allow their voice to be heard and share insight into who they are as an individual, there are likely many other topics they can choose to write about that are more distinctive and unique than COVID-19," Miller says.

Opinions among admissions experts vary on whether to write about the likely popular topic of the pandemic.

"If your essay communicates something positive, unique, and compelling about you in an interesting and eloquent way, go for it," Carolyn Pippen, principal college admissions counselor at IvyWise, wrote in an email. She adds that students shouldn't be dissuaded from writing about a topic merely because it's common, noting that "topics are bound to repeat, no matter how hard we try to avoid it."

Above all, she urges honesty.

"If your experience within the context of the pandemic has been truly unique, then write about that experience, and the standing out will take care of itself," Pippen says. "If your experience has been generally the same as most other students in your context, then trying to find a unique angle can easily cross the line into exploiting a tragedy, or at least appearing as though you have."

But focusing entirely on the pandemic can limit a student to a single story and narrow who they are in an application, Sawyer says. "There are so many wonderful possibilities for what you can say about yourself outside of your experience within the pandemic."

He notes that passions, strengths, career interests and personal identity are among the multitude of essay topic options available to applicants and encourages them to probe their values to help determine the topic that matters most to them – and write about it.

That doesn't mean the pandemic experience has to be ignored if applicants feel the need to write about it.

Writing About Coronavirus in Main and Supplemental Essays

Students can choose to write a full-length college essay on the coronavirus or summarize their experience in a shorter form.

To help students explain how the pandemic affected them, The Common App has added an optional section to address this topic. Applicants have 250 words to describe their pandemic experience and the personal and academic impact of COVID-19.

"That's not a trick question, and there's no right or wrong answer," Alexander says. Colleges want to know, he adds, how students navigated the pandemic, how they prioritized their time, what responsibilities they took on and what they learned along the way.

If students can distill all of the above information into 250 words, there's likely no need to write about it in a full-length college essay, experts say. And applicants whose lives were not heavily altered by the pandemic may even choose to skip the optional COVID-19 question.

"This space is best used to discuss hardship and/or significant challenges that the student and/or the student's family experienced as a result of COVID-19 and how they have responded to those difficulties," Miller notes. Using the section to acknowledge a lack of impact, she adds, "could be perceived as trite and lacking insight, despite the good intentions of the applicant."

To guard against this lack of awareness, Sawyer encourages students to tap someone they trust to review their writing , whether it's the 250-word Common App response or the full-length essay.

Experts tend to agree that the short-form approach to this as an essay topic works better, but there are exceptions. And if a student does have a coronavirus story that he or she feels must be told, Alexander encourages the writer to be authentic in the essay.

"My advice for an essay about COVID-19 is the same as my advice about an essay for any topic – and that is, don't write what you think we want to read or hear," Alexander says. "Write what really changed you and that story that now is yours and yours alone to tell."

Sawyer urges students to ask themselves, "What's the sentence that only I can write?" He also encourages students to remember that the pandemic is only a chapter of their lives and not the whole book.

Miller, who cautions against writing a full-length essay on the coronavirus, says that if students choose to do so they should have a conversation with their high school counselor about whether that's the right move. And if students choose to proceed with COVID-19 as a topic, she says they need to be clear, detailed and insightful about what they learned and how they adapted along the way.

"Approaching the essay in this manner will provide important balance while demonstrating personal growth and vulnerability," Miller says.

Pippen encourages students to remember that they are in an unprecedented time for college admissions.

"It is important to keep in mind with all of these (admission) factors that no colleges have ever had to consider them this way in the selection process, if at all," Pippen says. "They have had very little time to calibrate their evaluations of different application components within their offices, let alone across institutions. This means that colleges will all be handling the admissions process a little bit differently, and their approaches may even evolve over the course of the admissions cycle."

Searching for a college? Get our complete rankings of Best Colleges.

10 Ways to Discover College Essay Ideas

Tags: students , colleges , college admissions , college applications , college search , Coronavirus

2024 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

College Admissions: Get a Step Ahead!

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S. News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

Ask an Alum: Making the Most Out of College

You May Also Like

Ways to maximize campus life.

Anayat Durrani March 14, 2024

8 People to Meet on Your College Campus

Sarah Wood March 12, 2024

Completing College Applications on Time

Cole Claybourn March 12, 2024

Colleges Must Foster Civil Debate

Jonathan Koppell March 12, 2024

The Complete Guide to the TOEFL

Sarah Wood March 8, 2024

Unique College Campus Visits

Sarah Wood March 7, 2024

MBA Programs Fail to Attract Women

Joy Jones March 7, 2024

12 Colleges With the Most NBA Players

Cole Claybourn March 1, 2024

Higher Education on the Edge

Alan Mallach Feb. 29, 2024

Disability Accommodations in College

Anayat Durrani Feb. 23, 2024

The Student Voice of Austin Community College District

COVID-19: How a Pandemic Changed The Way We Live

Whether a student or a professor, or working at an office, or at a store, life has changed. As the number of cases in Travis and Williamson County continues to rise, life will continue to be different and will never be the same.

By: Angela Murillo Martinez

It is no surprise that nobody’s life is the same as it was before the pandemic occurred. Whether a student or a professor, or working at an office, or at a store, life has changed. As the number of cases in Travis and Williamson County continues to rise, life will continue to be different and will never be the same. Many have had to embrace change as they’ve had to continue working or even going to school, and as time continues it becomes more of a new reality. New routines are being built and embraced openly as there is no other option, but to continue in the midst of a pandemic.

According to the CDC, as of July 25th, the total number of cases in the whole United States is 4,099,310. A major spike in cases occurred as many states allowed public spaces to re-open such as stores, amusement parks, churches, workplaces, and many more. In the state of Texas, it is reported that there are 369,826 cases. Although the number of cases continues to rise in the state, public spaces in the state continue to remain open. In Williamson County alone, so far 5,145 cases have been reported in one day, and in Travis County, 18,939 cases have been reported.

It is important to remember to follow safety procedures to avoid furthering the spread of COVID-19 and to make sure that everyone remains healthy and safe. If one finds themselves going out, don’t forget to bring a face covering. As of the third of July, all Texans are required to wear face masks in public spaces. Failure to comply with such orders may result in a warning at first and in further violations, one can be fined up to $250. Additionally, it is important to respect the space of others and maintain a six feet distance when out in public. The Texas Health and Human Services also recommends washing one’s hands often with soap and water for 20 seconds and also mentions avoiding touching one’s face with unwashed hands. Amongst other actions shared on their website to prevent the spread of COVID-19, an important one is too often disinfected surfaces that are often touched by others.

With this being said, people have to keep working, students have to continue going to school, and in general, life has to continue. The only difference now is exactly how life is being continued by people. For Stephanie Murillo, a student studying criminal justice and obtaining her paralegal certification, she has had to not only adjust to a new job but also adjust to working from home and taking online classes. It had been only two weeks at her new job as a court clerk when her office was closed and she had to start working remotely. Now it’s been five months and she’s had to learn everything through zoom calls and emails, while also managing her online classes. She admits that it has been hard having to manage to work at home and taking online classes, especially since her hours at work have extended. No longer being able to follow the usual seven to five schedule she had been following before the pandemic. “Before I was able to leave work at five and it would stay there, and I would be able to come home or go to school.

But now I just feel like I work extra hours because my office is my room.” On top of that, she admits that taking her classes online has required more time and commitment. To her, it seems that her days have only gotten longer and the workload has become heavier.

Furthermore, she has felt it was a difficult transition to have to learn everything she needed to know remotely and to also learn how to manage all the technology necessary to continue. “I was in the process of learning my new position but then when the pandemic started, I had to be trained in something that was new to my co-workers, which was working remotely from home.” Despite the difficulties and challenges she has had to face, she has grown to like working from home and admits that she will find it difficult to return to the office. Although she’s been told that they will return to the office since June, so far the official date is still uncertain and continues to change as the situation escalates. They have planned to return to the office on August 17th, though this isn’t a set date. So for now, she continues to work remotely and learn as much as she can while being physically apart from her co-workers.

For other students such as Kylie Birchfield, a talented photographer studying photography, she’s had more time to focus on her passion. Though she did find the last couple of months left in the Spring semester difficult as a result of transitioning to online classes, she has found herself with more free time on her hands as a result of the pandemic. Not only has she been able to work more on her own personal photography projects, but she’s also been able to get an internship with Austin Woman Magazine . “I know not a lot of people have gotten good things out of this, but for me, I’ve had a lot of good things come out of it.” In her internship with the magazine, she has been able to do a feature with them on COVID-19 where she photographed three women who find themselves on the front lines of the fight against the pandemic.

She has found that as more people spend more time on social media, the more people she has finding her page and lining up to work with her. Although now, there are certain safety procedures she follows to avoid furthering the spread of COVID-19 such as maintaining a distance and wearing a mask when working with others. As the previously mentioned guidelines are more implement into one’s new daily routine, she often has to remind herself of bringing her masks and maintaining a distance at photoshoots.

“Sometimes I have to rethink what I’m doing in photoshoots. I can’t get up close, can’t move their hair, I have to ask them to move their hair around.”

With this being said, she continues to find herself with more opportunities and considers this a “kickstart” for her career. Despite losing her job as a result of the pandemic, she finds herself blessed to have the free time she has now and has been using it to do what she loves.

Others like Mary Monk, a student studying Government, no longer finds herself having to commute to her classes. Hence, saving her time that she would spend taking the bus and traveling from class to class. While she did find it hard to transition to online classes at the end of the Spring semester, she realized that in most of her classes they were easy to finish without meeting in person. As a result of the pandemic, she has found it hard to find an internship or a

“Your Freshman summer is supposed to be the time where you get internships and jobs, and it’s so hard because I applied to so many internships and they’ve just been like ‘oh, we have to see because of COVID’… So it’s been really difficult in that regard,” said Monk

Although Monk was used to her friends going to different schools and living far, resulting in not being able to see each other often. She now finds herself talking more consistently with them through text and video calls.

“With family, at first, I think we were all on the same page, but as time goes on, and people are in their homes for longer, our family gets a little divisive on what we should be doing, and what caution we should be taking,” said Monk

But as far as her immediate family, she finds herself at home with them safely and spending more time together as they are unable to go out. As she continues to take online classes, she sees this as an opportunity to further her studies.

“I feel like I can take on more than I probably thought I could if I had to do them all in person because with actually going to school, physically, you have to take into account how long it’s going to take you to go from one building to another.”

Now, Monk takes her classes online, her room becomes her classroom and she no longer has to leave it to attend class. She plans that if the pandemic continues on for longer, which she thinks it will, she will most definitely take more classes and hopes to find an internship that can begin to prepare her for her career.

Despite being unable to meet on campus or be physical together, organizations are still continuing to meet through video calls. One of those organizations being the German club, which has met every three weeks during the summer. Although there are certain things that have changed and other things that they are no longer able to do since moving to video calls, the club hasn’t changed that much. “We do the same things, we just do them differently. We used to play board games, and we obviously don’t do that anymore, but we played hangman at a bunch of the meetings I remember going to, and we still play hangman online,” said the club president Lauren Sanders.

Though their group has gotten smaller since they transitioned to video calls, they have built a small, defined group who all meet together and converse in both German and English. They do admit that it has been harder to get people involved since they are no longer able to put posters around the Highland campus or have people show up after German class, but still, they continue to meet and encourage that all those interested in German no matter the level of expertise, to join them.

Since the pandemic started, the club never planned on stopping and quickly continued moving forward.

“I thought the club was going to end, seeing how things were going, only a few of us were left. But when they were saying, we have to decide who’s going to be the president, treasurer, and secretary, ‘I was like ok, we’re still doing this. I’m in’ and I mean it’s something to do when I’m at the house quarantining all day,” said Emiliano Antunano.

This same resilience has kept them going through the pandemic and continues to push them despite having to continue meeting online in the upcoming fall semester. The club which consists of German speakers of all levels has a supportive and welcoming community, where they are all helping each other improve their German, but also keep each other company in the midst of the pandemic. In the words of a club

member,

“I hope to go to the in-person meeting when all this ends since I haven’t been able to go to those since I joined after all this happened,” said Marshall Brown.

While life had seemed to pause at the beginning of the pandemic, people were unable to continue like this forever, and life has had to continue. As people begin to return to work at their offices or at stores or begin to go out again or return to campus, it doesn’t mean that the pandemic has completely gone away. If anything, the number of cases continues to rise, and therefore, everyone should continue to be careful to protect not only their health but the health of others. Everyone is having to face a new reality and is experiencing new routines, so no one is alone in this situation. Although life continues with uncertainty, if everyone works together and follows the necessary precautions, soon we’ll be able to all be together again on campus.

For this and more stories like this

College essay samples

How 2020 and covid-19 changed my life.

Usually people like the New Year not only because they expect something unusual and great to happen during holidays, but also they hope that the coming year is going to bring a lot of positive changes to their lives and that they will gain new opportunities for self- realization, will have new contacts and friends and so on.

When the year 2020 started, I could not even imagine what kind of significant changes it was going to bring into my life as well as to the lives of millions of people worldwide. I think nobody could expect that we will have to face an absolutely different reality and cope with absolutely different problems, which we were used to in our normal lives. I am convinced that the year 2020 has impacted each single individual on our planet to some extent.

I heard a lot about thinking positively before, but I have always associated it with some minor everyday things, like for example conflicting with your parents. You should not feel desperate, just relax and do your best to solve the problem and leave the conflict in the past. Or when you have a difficult exam for example, you should not be tense and stressed, this will not help you to do your best during it or you might even fail. Instead, it is better to think positively and try your hardest.

The year 2020 has shown to me that the real meaning of thinking positively is much deeper and more serious in comparison to everyday problems. I have found out that there are much more problems in our lives, than I could imagine before. First of all you should constantly feel under the pressure of the risks, related to the virus. Everybody has ageing family members and realization of the fact of their current vulnerability makes you change your attitude to them and to communication with them in a different way.

Actually, any close person is at risk, thus you constantly feel that you want to protect your family, your close people from getting sick and risking their lives. I have some of my friends, who started to have psychological problems, because of the isolation and COVID -19 dangers. I did my best to support them and here I remembered again about the real meaning of thinking positively. You should think positively for the sake of other people, who turn out to be not that strong as you, either physically or mentally.

The year 2020 has revealed to me other life truths as well. For example I have learnt to appreciate the things, which I used to accept as ordinary ones before. I appreciate the opportunity to spend time with my beloved people, I appreciate the time spent outside, in the park for example, I started to like any kind of weather, as it is not that important, whether it is raining, or it is hot, you can always find the ways to comfort yourself if you continue to think positively.

I learnt how to notice some nice things and to focus upon them, instead of thinking about dangers, related to coronavirus and plunging into depression. I have experienced the pleasure of physical exercise without any specially organized conditions, just at home or in the park near my home. From now on my regular sport activities contribute to my way of positive thinking. I continue to exercise my positive thinking and to add new notes and aspects to it. I become more open towards new experiences and ideas in my life and this is the most important change, which happened to me in 2020.

Do you like this essay?

Our writers can write a paper like this for you!

Order your paper here .

- High contrast

- About UNICEF

- Where we work

- Explore careers

- Working in emergencies

- Diversity and inclusion

- Leadership recruitment

- Support UNICEF

- Search jobs

- Candidate login

Search UNICEF

"my view of life changed when i got covid-19", agnes barongo, communication for development specialist in uganda, realized firsthand the impact of covid-19 on women's lives.

On March 8 , it's International Women's Day . This year’s theme is " Women in leadership: Achieving an equal future in a COVID-19 world ", celebrating the tremendous efforts by women around the world in shaping a more equal future and recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. At UNICEF , we want to celebrate the achievements of women in leadership positions, and also those who display leadership qualities.

Throughout the whole month of March 2021, the Women's Month , we publish the stories of only a few of the many women who make a difference in UNICEF every day. Today, we host the interview of Agnes Barongo , our Communications for Development (C4D) Specialist in UNICEF U ganda

My life view changed just before Christmas when I got COVID-19. I was utterly shocked and kept asking how I could fail at observing the prevention protocols. Now I truly understand the psychological and physical meaning of living with COVID19. Not everyone is fortunate to have ready access to social services, so I am fortunate. But the experience provided me with further compassion and determination to keep doing the best to ensure less fortunate citizens get access to the right information and services that can save their lives

Agnes Barongo

Communications for Development (C4D) Specialist, Uganda

Who are you and what is your role at UNICEF?

I hail from Hoima District, located in mid-western Uganda. It is one of 135 districts in the Republic of Uganda that has a total population of 45.7 million people. Its capital, Hoima City, has just been converted into a city as part of the development agenda to upgrade Municipal Town Councils around the nation. I work as a Communication for Development Specialist based in Kampala City, the capital of the Republic of Uganda. My main responsibilities centre on ensuring that bottlenecks to the adoption of positive behaviourial and societal practices are addressed at different levels in our society from the household, to the community, to the district and national levels. I work with the Education and Child Protection teams in UNICEF, Government and Civil Society Organizations to have these addressed in the first and second decades of a child’s life. Presently, I work in 30 focus districts and with eight government line ministries to ensure that both at the community and national levels, there are systems running in place to support vulnerable children to have access to education and child protection social services.

How did COVID-19 impact your life, both on professional as well as on personal level?

On a professional level COVID-19 provided me with a revisit to emergency work that I had already been supporting as the alternative focal point in the Communication for Development Unit, under the Communications and Partnerships Section in UNICEF Uganda Country Office. I had already been part of the emergency interventions supporting the Ministry of Health under the Public Health Emergency Operations Centre and National Task Force during the 2017 Marburg outbreak in Eastern Uganda and the 2018 – 2019 Ebola Virus Disease outbreak in Western Uganda. Health emergencies being a cross-sectoral programme I had already experienced what it means to ensure that the all the education and child protection stakeholders convene to discuss and take action on addressing the virulent outbreaks. I also was able to understand in these two outbreaks the vital importance of being vigilant and being the example to demonstrating how to stick to Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) when it came to personal and team safety measures. When COVID-19 broke out, I was on leave, however, my prior experience with emergencies and virulent outbreaks made me more conscious and empathetic to the communities around me. Not everyone responds to directives set out by government or district officials. My job continues to provide me with perspectives on how there needs to be a re-invention each time to see how best to encourage people to keep adhering to positive social and behaviourial practices that would keep them safe from obtaining any deadly virus of epidemic proportions, infecting people and dying a death that could be prevented. I found myself greeting strangers, advising them on the protocols for protecting themselves from COVID-19. I also did get into situations where I would inquire from a service delivery point why there was no sanitizer, washing point or temperature gun present. Of course, in these circumstances, it was imperative to have a demonstrative level of understanding, humility but at the same time determination in getting the safety protocols message across to the people in the communities I interacted in. At a personal level, the COVID-19 situation made me learn to understand my family better. During lockdown, there were various moments of epiphany, living in a household with extended family members. Inadvertently, the proximity helped me to understand and become more empathetic to the individual challenges we as humans face daily. I am less judgmental now when it comes to reviewing cases of violence because I realized that our upbringing colluding with our immediate environment and personal difficulties in attaining a sustainable living, can bring out the worst behaviourial traits. I try not to make excuses but at least I have a more varied approach to making inquiries into trying to understand what drives each human being to perform an act of violence against family or strangers.

My life view changed just before Christmas when I got COVID-19. I was utterly shocked and kept asking how I could fail at observing the prevention protocols. However, it also made me ensure that I paid acute attention to treatment. I reported daily to the UN doctor in charge and took medication and monitored my vitals. When I went for the exit COVID-19 test, I was extremely nervous and did not sleep the night before. The following day when I got my results, there was an explosion of relief. Now I truly understand the psychological and physical meaning of living with COVID19. I am a better person when it comes to vigilance in observing prevention protocols and to the occasional dismay of my family, I keep repeating the SOPs because I understand firsthand how the pandemic has impacted on me.