Case Studies: Successful Events Using Event Software

Introduction.

In the evolving realm of event planning, success hinges on adapting to the target audience’s demands and creating memorable experiences. This compilation of case studies uncovers the success stories of prominent organizations such as GE Healthcare, leveraging modern platforms in the information technology sector. These stories illuminate the transformative power of event software in orchestrating successful product launches, virtual and hybrid events, and esports competitions across the United States and beyond. They highlight amplified customer satisfaction, enhanced security, significant cost savings, and insightful analytics, offering valuable lessons for event planners on the path to success. Delve into these customer stories to discover how the right platform can elevate your event planning strategies.

5 Event Case Studies

Case study 1: product launch by ge healthcare.

GE Healthcare leveraged a top-tier platform in the information technology sector to successfully launch a groundbreaking product. This case study emphasizes the crucial role of analytics in understanding the target audience, leading to a memorable experience and amplified customer satisfaction.

Case Study 2: Virtual Event In The United States

As the demand for virtual events surged, a prominent firm triumphed in hosting a large-scale virtual event using advanced event software. The event offered attendees an interactive experience and demonstrated impressive cost savings, making it a success story worth noting.

Case Study 3: Hybrid Event In The Information Technology Sector

In this customer story, an IT company adeptly bridged the gap between physical and digital spaces, setting up a hybrid event that attracted a broad audience. The event showcased the platform’s security features, underscoring the importance of safety in memorable experiences.

Case Study 4: Esports Competition

This case study recounts how a leading Esports organization used an event software platform to deliver an exceptional experience for attendees, from live streaming to real-time social media integration. This success story encapsulates the power of creating memorable experiences for a specific target audience.

Case Study 5: United Nations Conference

The United Nations harnessed event software to enhance the attendee experience at a crucial conference. With robust analytics, seamless security, and improved customer satisfaction, this case study is an example of how event planners can utilize technology for successful and impactful events.

The Skift Take: These case studies demonstrate the powerful role of event software platforms in facilitating successful events, from product launches to large-scale conferences. Leveraging technology, organizations like GE Healthcare and the United Nations have improved attendee experience, enhanced security, saved costs, and gained valuable insights. These success stories serve as a testament to the transformative potential of information technology in event planning.

Why Event Badges Will Never Be The Same Again [Case Study]

The digital revolution has forever changed the face of event badges. In our case study, we delve into how technology-driven badges have enhanced the event experience, providing not just identity verification, but also serving as a tool for networking, data collection, and improving overall attendee engagement.

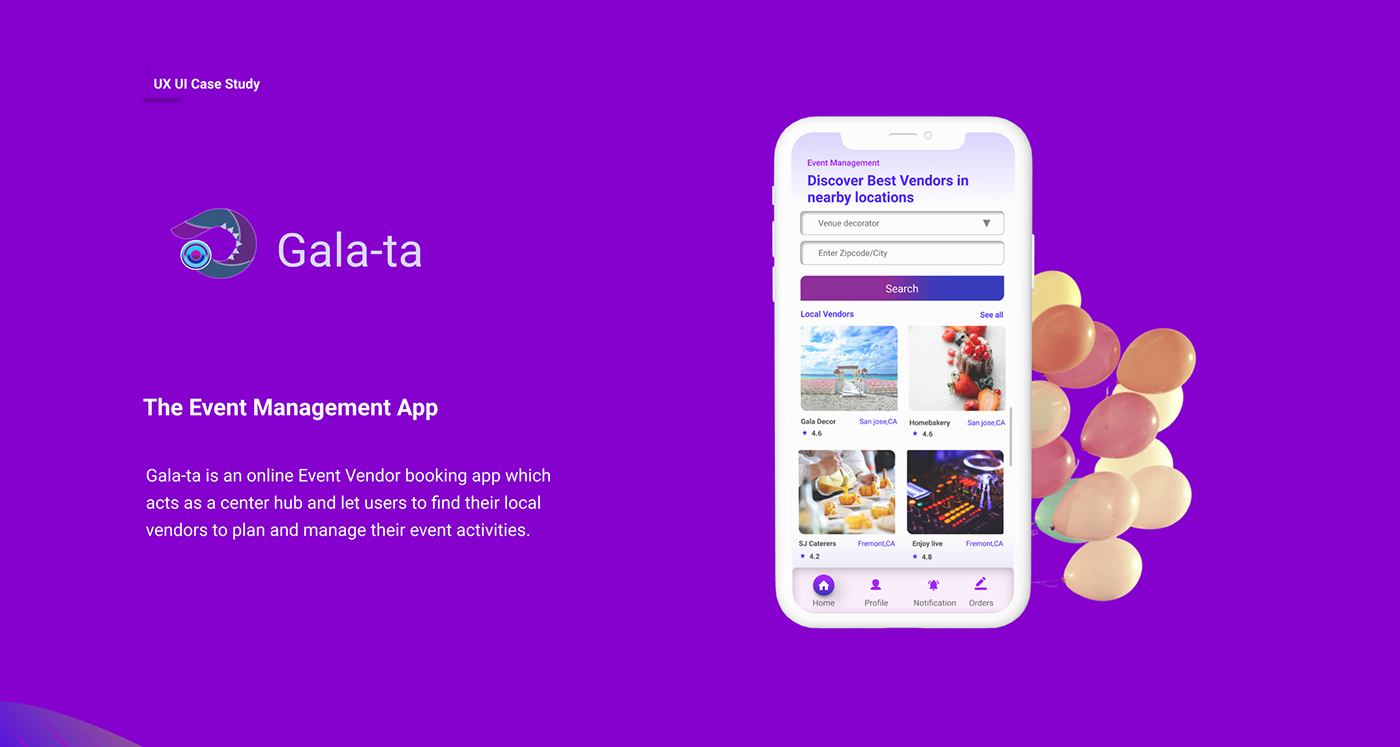

How To Increase Engagement With Your Event App By 350% [Case Study]

In this case study, we unravel the strategy behind a staggering 350% increase in event app engagement. Through a blend of user-friendly design, interactive features, and personalized content, the case underlines the power of a well-implemented event app in boosting attendee interaction and enhancing the overall event experience.

How To Meet Green [Case Study]

This case study explores the concept of sustainable event planning. It illustrates how a platform’s features can facilitate ‘green’ events, thereby reducing environmental impact while ensuring a memorable attendee experience. Such initiatives highlight the potential for event software to contribute meaningfully towards global sustainability goals.

How To Increase Attendance By 100+% [Case Study]

This case study explores the tactics employed by an organization which led to a remarkable doubling of event attendance. The successful campaign, powered by a robust event software platform, offered personalized communication, early bird incentives, and an appealing event agenda, demonstrating the potential of effective marketing strategies in boosting event turnout.

How This Event Boosted Their Success [Case Study]

This case study unravels the success journey of an event that significantly boosted their success using a comprehensive event software platform. The strategic use of interactive features, data insights, and exceptional planning led to a remarkable rise in attendee satisfaction and engagement, underlining the game-changing potential of technology in event management.

In the dynamic field of event planning. The power of leveraging advanced platforms in information technology, as demonstrated in the case studies, is clear. Success stories from esteemed organizations such as GE Healthcare. Underscore the invaluable role of event software in facilitating triumphant product launches, virtual and hybrid events, and even esports competitions. The benefits are manifold, including enhanced customer satisfaction, improved security, substantial cost savings, and the generation of valuable analytics to guide future strategies. These case studies serve as tangible proof that the right technology can significantly elevate the success of your event.

If these success stories inspire you to embrace the transformative power of event software. We invite you to experience the difference firsthand. Orderific is ready to demonstrate how our platform can elevate your event planning process. Book a demo with us today and begin your journey towards unprecedented event success.

What role do event case studies play in the event planning and management process?

Event case studies offer real-world examples of successful planning and management strategies, providing valuable insights and lessons.

How can event professionals benefit from studying real-world success stories in the industry?

They can gain practical knowledge, tactics, and inspiration to implement successful strategies in their own events.

What types of insights can event case studies provide for improving future events?

Event case studies provide actionable insights into effective planning strategies, attendee engagement, and ROI optimization.

Are there specific industries or event types that are commonly featured in case studies?

Yes, industries often featured include tech, healthcare, and entertainment, and event types range from corporate events to music festivals.

How can event planners effectively apply lessons learned from case studies to their own projects?

They can apply these lessons by tailoring the strategies highlighted in case studies. Which aligns with their event’s unique needs and goals.

Introduction Enhancing a new employee's onboarding experience is crucial in an increasingly digital world. Through our advanced onboarding software, we Read more

Introduction Artificial intelligence (AI) is revolutionizing the event planning industry, offering event planners innovative tools to craft immersive, personalized experiences. Read more

Introduction Event technology is rapidly evolving, presenting opportunities and challenges for event planners. The adoption of event tech can significantly Read more

Introduction The era of big data has ushered in an unprecedented opportunity for event organizers. The wealth of event data Read more

You might also like

15 fun cinco de mayo activities for kids, savor the best of culinary at boston restaurant week, sweet treats in san diego: nothing bundt cakes, event branding with event management software, event marketing strategies using software, why event management software is essential, get a free demo now, turn your food business into a smart restaurant for free with orderific pay at the table software.

- Skift Meetings

- Airline Weekly

- Daily Lodging Report

- Skift Research

Event Management

5 Event Case Studies

Skift Meetings Studio Team

January 13th, 2017 at 10:00 AM EST

Event planners are creating effective and successful events every single day, but on the whole we could do better with sharing event data and best practice. Here are 5 event case studies we can all learn from.

- LinkedIn icon

- facebook icon

Whether it is down to time, client confidentiality or protecting our ideas and ways of working eventprofs seem to struggle with shouting about our achievements and letting others benefit from our successes (or failures).

When a project is over we brainstorm and analyze internally within our team and with our clients but very few of us publish meaningful data and outcomes from our events for others to learn from and be inspired by. Perhaps this is one of the reasons why some executives struggle to appreciate the results and return that events can bring and why we still battle to protect event budgets in times of austerity?

As an industry we should work harder to crystallize the Return on Investment and Return on Objectives so there can be no doubt about the importance and relevance of events to the marketing mix. We need to demonstrate more clearly exactly how we added or created value through our events to prove that they are essential.

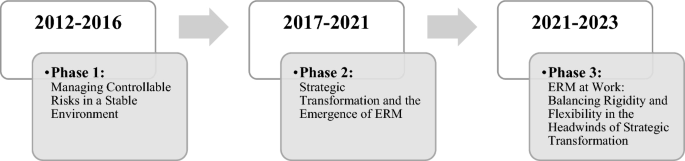

These 5 case studies from 2016 focus on events that achieved their objectives and share top tips on their learnings and data.

Why Event Badges Will Never Be the Same Again [Case Study]

The 2016 Seattle GeekWire Startup Day used technology to help attendees get more from networking opportunities at the event and improve the experience. Through smart event badges they were able to create a total of 9,459 positive matches between participants with shared interests and analyze more closely the supply and demand.

How to Increase Engagement with your Event App by 350% [Case Study]

![case study for event management How-to-Increase-Engagement-with-your-Event-App-by-350%-[Case-Study]](https://meetings.skift.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/How-to-Increase-Engagement-with-your-Event-App-by-350-Case-Study.jpg)

If you invest in a mobile app for your event you want to be sure that people will download and use it. This case study outlines how the MAISON&OBJET exhibition increased engagement with their event app by 350%

How To Meet Green [Case Study]

One of the objectives of the Canadian Medical Association Annual Meeting was to create the greenest event going. Focusing on three main areas, this is how they did it and the difference they made.

How to Increase Attendance by 100+% [Case Study]

Streamlining the registration process can have a big impact on workload and numbers. This case study shares how the Colorado Judicial Branch doubled the number of attendees for their largest conference and saved countless hours of administration time.

How This Event Boosted Their Success [Case Study]

Running regional events as part of a country-wide tour has plenty of challenges. This case study looks at how The Get Fit and Thick tour streamlined their processes for event success across the US.

In Conclusion

As these 5 case studies demonstrate, events can make a difference at a micro and macro level. As an industry let’s make a pledge to share our learnings, both positive and negative. By taking this bold step we can educate and support each other to run more effective events and further professionalize the event industry and spend event budget where they will yield the greatest results. We know the importance of events, and event technology , we need to do more to prove it to those that still need convincing.

New Bureau Launches to Meet High Demand for AI Speakers

Keynote speakers with expertise in artificial intelligence are in high demand as organizations embrace the new technology. One emerging speakers bureau is crafting bespoke sessions to meet client objectives.

New FTC Rule Addresses Common Event Scams

A new ruling by the Federal Trade Commission targets scammers seeking to rip off the business events industry, paving the way for direct monetary compensation from bad actors.

The New Age of Data-Driven Event Strategies

In the quest to navigate the event data deluge, the real challenge lies in separating insightful narratives from mere numbers. It's the human touch—crafting memorable experiences and compelling stories—that will ultimately define the success of events in the data-driven age.

Why Pipeline Is the Ultimate Goal of Building Communities

Sales pipeline and community engagement aren't inherently at odds. When the balance is right, companies can successfully foster, support and monetize communities that positively affect their profits.

How to Plan for Attendees with Dietary Requirements

Vegan, gluten-free, paleo, and nut allergies are just some of the dietary requirements that event professionals should be aware of.

Get the Skift Meetings Standup Newsletter

Our biweekly newsletter delivers fresh, original content – straight to your inbox, every Tuesday and Thursday.

- Industry Trends

- Attendee Engagement

- Event Marketing

- Event Planning

- Personal Development

- Data Management

- Personalisation

Case Studies

- Testimonials

- All Resources

If you do not know your client account name, please contact the Eventsforce support team:

E: [email protected] T: +44 20 3868 5338

- Book a Demo

The Content Hub for Tech-Savvy Event Planners

Every event is different, and we work with great organisations of all shapes and sizes to deliver cutting edge event technology solutions, boosting event success and increasing ROI. Why not see for yourself? And if you think we could help you in the same way, we’d love to start a conversation.

Eventsforce offers UKHSA agile solution for dynamic event needs

Eventsforce and the society for acute medicine (eventage), eventsforce and the national cancer research institute (ncri), "eventsforce was the best option for us" - wellcome, eventsforce and allianz insurance plc, eventsforce and santander.

"The Eventsforce onboarding team evaluated our situation and proposed a solution that made the entire process of event planning a whole lot easier. Tasks that were so time-consuming in the past - such as setting up registration forms, emailing invitations and managing delegate lists...

See why top corporates choose Eventsforce

Eventsforce and haymarket, are your events complying to gdpr, eventsforce and shsc events (nhs scotland), eventsforce and wellcome, eventsforce and schroders, eventsforce and the liberal democrats, our clients.

Our partnership approach is reflected across everything we do

Onboarding/training.

Our dedicated team of experienced event professionals will provide step-by-step guidance and training to help set out your event objectives and get the most out of your Eventsforce investment.

24/5 First-Class Support

Our friendly, knowledgeable support team is always ready to help with any questions you may have about your Eventsforce system. With a one-hour average response time, we also consistently smash industry ratings for customer support!

- Book A Demo

Based on your existing workflows, timings and objectives, we'll provide recommendations that will help you achieve success.

New Mobile App Launched - Drive attendee participation and build lasting relationships.

New mobile app launched - for simple events, tradeshows, or multi-stream conferences, new mobile app launched - find out more today.

Event Management

(Previously published as Festival Management & Event Tourism)

Editor-in-Chief: Mike Duignan www.MikeDuignan.com Volume 28, 2024

ISSN: 1525-9951; E-ISSN: 1943-4308 Softbound 8 numbers per volume

CiteScore 2022: 1.7 View CiteScore for Event Management

Go to previously published journal, Festival Management & Event Tourism

A welcome to the journal by Editor-in-Chief, Dr. Mike Duignan.

Journal Activity

Items viewed per month for this Journal through Ingenta Connect: February 2024

Table of Contents: 2,805 Abstracts: 35,817 Full Text Downloads: 1,223

Get Periodic Updates

Email (required) *

Yes, I would like to receive emails from Cognizant Communication Corporation. (You can unsubscribe anytime)

Aims & Scope

Event Management is the leading peer-reviewed international journal for the study and analysis of events and festivals, meeting the research and educational needs of this rapidly growing industry for more than 20 years.

- Publish high-quality interdisciplinary event studies work and therefore promote a broad spectrum of theoretical perspectives from management and organizational studies to sociology and social science.

- Encourage the study of all kinds of physical, digital, and hybrid events from small- to large-scale cultural and sporting events, festivals, meetings, conventions, exhibitions, to expositions, across a range of geographical and cultural contexts.

- Actively support authors to take a critical perspective concerning the power and potential of events as a force for social, economic, and environmental good, while challenging where events can do better and make a positive contribution to society.

- Promote bold, interesting, relevant research problems and questions. Examples include why events play a key role for individual and collective transformational experiences; how social movements like #BlackLivesMatter and #Metoo can be advanced by attaching to events like the Academy Awards; through to the way large-scale events are leveraged for urban regeneration and community development.

- Believe research insights are integral to high-quality learning and teaching and we encourage all authors to transform manuscript into a set of Event Management branded PowerPoint slides for colleagues to integrate into research informed and hybrid teaching approaches. Where provided by authors, slides will feature alongside each published manuscript for ease. All subscribing organizations and authors will have access to this library of learning and teaching content.

We offer authors four routes to publication, with simple submission guideline (see “Submission guidelines” tab).

- Research article – a traditional submission route of up to 10,000 words focused on contributing to theory.

- Research note – a short note of up to 2,000 words focused on providing novel and/or innovative insights to contribute to our body of theory and/or empirical knowledge. These can also include debates and/or commentaries.

- Event case study – a new route of up to 10,000 words providing in-depth empirical insights and application of existing theoretical ideas to a specific event or series of events.

- Event education – a new route of up to 10,000 words providing in-depth insights into events-related education policy and/or practice for colleagues to support high-quality international learning and teaching experiences.

Event Management is governed by a high-quality editorial board consisting of international leading experts across a range of disciplines and fields, including events, tourism, sport, hospitality, to business studies (see “ Editorial board ” tab).

Our double-blind peer review process is rigorous and supportive.

STEP 1: All manuscripts submitted to Event Management will go through a rigorous screening process by either the Editor-in-Chief or Deputy Editors to be desk rejected or progressed to one of 40+ Associate Editors who handle the review process.

STEP 2: An Associate Editor reviews the manuscript and decides whether to progress or rejected. If progressed, 2-3 members of the Editorial Advisory Board or those with appropriate expertise are invited to review with an average 2-3 rounds of peer review. Authors have 8 weeks to revise and resubmit for each round of peer review.

STEP 3: Toward the end of peer review the Associate Editor recommends a final decision to the Editor-in-Chief or Deputy Editor who makes the final decision and provides final constructive feedback where appropriate.

STEP 4: Manuscripts accepted are swiftly uploaded to our “Fast Track” system with a DOI while our editorial assistants work with authors to deal with author queries before final manuscripts are made available. FINAL PUBLISHED ARTICLES WILL BE MADE AVAILABLE AS FREE ACCESS (at no charge) ON INGENTA CONNECT FOR A PERIOD OF 15 DAYS and will be actively promoted by our Social Media Editor who works with authors to create a short tweet and author video alongside free links to promote colleagues’ work, across our Twitter and LinkedIn sites. (After the 15 days manuscripts will only be available to subscribers, unless the author has paid for the Open Access option.)

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Mike Duignan Associate Professor Rosen College of Hospitality Management University of Central Florida Orlando, FL, USA [email protected] Deputy Editors Leonie Lockstone-Binney , Griffith University, Australia James Kennell , University of Surrey, UK David McGillivray , University West of Scotland, UK Milena Parent , University of Ottawa, Canada Luke Potwarka , University of Waterloo, Canada Emma Wood , Leeds Beckett, UK Editorial Managing Editor Aaron Tkaczynski , University of Queensland, Australia

Regional Development Editor Ubaldino Couto , Macao Institute for Tourism Studies, China

Regional Editors

Australia and New Zealand Clifford Lewis , Charles Sturt University, Australia Effie Steriopoulos , William Angliss Institute, Australia

Canada Luke Potwarka , University of Waterloo, Canada Christine Van Winkle , University of Manitoba, Canada

Central, Western, and South Asia Jeetesh Kumar , Taylor’s University, Malaysia

China Chris Chen , University of Canterbury, New Zealand Shushu Chen , University of Birmingham, UK Zengxian (Jason) Liang , Sun Yat-sen University, China Ying (Tracy) Lu , University of Kentucky, USA

East Asia Meng Qu , Hokkaido University, Japan Europe Krzysztof Celuch , Nicolas Copernicus University, Poland Kristin Hallman , German Sport University Cologne, Germany Martin Schnitzer , University of Innsbruck, Austria Raphaela Stadler, Management Center Innsbruck, Austria Erose Sthapit , Manchester Metropolitan University, UK North Africa and Middle East Majd Megheirkouni , Leeds Trinity University, UK

Southeast Asia Supina Supina , Bunda Mulia University, Jakarta

South, Western, Eastern, and Central Africa Kayode Aleshinloye , University of Central Florida, USA Brendon Knott, Cape Peninsula University of Technology, South Africa

United Kingdom Marcus Hansen , Liverpool John Moores University, UK Ian Lamond , Leeds Beckett University, UK Jonathan Moss, Leeds Beckett University, UK Brianna Wyatt , Oxford Brookes University, UK

United States Ken Tsai , Iowa State University, USA Nicholas Wise , Arizona State University, USA

Social Media Editor Danielle Lynch , Technical University Dublin, Ireland

Podcasting Editors Alan Fyall , University of Central Florida, USA James Kennell , University of Surrey, UK

Awards Editor Leonie Lockstone-Binney , Griffith University, Australia

Curated Collections Editor Vacant position

Special Advisors Laurence Chalip , George Mason University, USA Alan Fyall, University of Central Florida, USA Leo Jago , University of Surrey, UK Adele Ladkin , Bournemouth University, UK Stephen Page , University of Hertfordshire, UK Holger Preuss , University of Mainz, Germany Richard Shipway , Bournemouth University, UK

Thought Leaders James Bulley OBE, CEO, Trivandi, UK Paul Bush OBE, Director of Events, VisitScotland, UK Sarah de Carvalho MBE, CEO, It’s a Penalty, UK Gary Grimmer , Founder and Chairman, Gaining Edge, Canada Richard Lapchick , Director, Institute for Sport and Social Justice, UK Genevieve Leclerc , CEO, #Meet4Impact, Canada Shona McCarthy , CEO, Edinburgh Festival Fringe Society, UK Nick Moran , Founder, Phantom Peak, UK John Siner, Founder, WhySportMatters, USA Lucy Spokes , Head of Public Engagement and former Director of the Cambridge Festival of Ideas, University of Cambridge, UK John Tasker , Founder, Massive, UK

Co-Founding Editors Donald Getz , University of Calgary, Canada Bruce Wicks , University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, USA

Associate Editors Tom Fletcher , Leeds Beckett University, UK ( Chair of the Associate Editors Board ) Kayode Aleshinloye , University of Central Florida, USA Jane Ali-Knight , Edinburgh Napier University, UK Charles Arcodia , Griffith University, Australia Sandro Carnicelli , University of the West of Scotland, UK Willem Coetzee , Western Sydney University, Australia Alba Colombo , Universitat Oberta de Catalunya, Spain Simon Darcy , University Technology Sydney, Australia Kate Dashper , Leeds Beckett University, UK Tracey Dickson , University of Canberra, Australia Sally Everett , Kings College London, UK Sheranne Fairley , The University of Queensland, Australia Kevin Filo , Griffith University, Australia Rebecca Finkel , Queen Margaret University, UK Chris Gaffney , New York University, USA Sandra Goh , Auckland University of Technology, New Zealand Kirsten Holmes , Curtin University, Australia Xin Jin , Griffith University, Australia Kiki Kaplanindou , University of Florida, USA Donna Kelly , New York University, USA James Kennell , University of Surrey, UK Zengxian (Jason) Liang , Sun Yat-sen University, China Qiuju (Betty) Luo , Sun Yat-sen University, China Eleni Michopoulou , University of Derby, UK Laura Misener , Western University, Canada Bri Newland , New York University, USA Ilaria Pappalepore , University of Westminster, UK Nikolaos Pappas , University of Sunderland, UK Greg Richards , Breda University of Applied Sciences, Netherlands Martin Robertson , Edinburgh Napier University, UK Martin Schnitzer , University of Innsbruck, Austria Louise Todd , Edinburgh Napier University, UK Christine Van Winkle , University of Manitoba, Canada Oscar Vorobjovas-Pinta , University of Tasmania, Australia Lewis Walsh , Anglia Ruskin University, UK Karin Weber , Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong Nicholas Wise , Arizona State University, USA Jinsheng (Jason) Zhu , Guilin Tourism University and Chiang Mai University, Thailand Vassillios Ziakas , University of Liverpool, UK

Editorial Advisory Board Rutendo Musikavanhu , Coventry University, UK ( Chair of the Editorial Advisory Board ) Emma Abson , Sheffield Hallam University, UK Eylin Aktaş , Pamukkale University, Turkey John Armbrecht , University of Gothenburg, Sweden Jarrett Bachman , Fairleigh Dickinson University, Canada Ken Backman , Clemson University, USA Sheila Backman , Clemson University, USA Carissa Baker , University of Central Florida, USA Jina Hyejin Bang , Florida International University, USA Rui Biscaia , University of Bath, UK Charles Bladen , Anglia Ruskin University, UK Soyoung Boo , Georgia State University, USA Glenn Bowdin , Leeds Beckett University, UK Ian Brittain , Coventry University, UK Alyssa Brown , University of Sunderland, UK Federica Burini , University of Bergamo, Italy Krzysztof Celuch , Nicolaus Copernicus University, Poland Jean-Loup Chappelet , University of Lausanne, Switzerland Guangzhou Chen , University of New Hampshire, USA Gyoyang Chen , Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand Brianna Clark , High Point University, USA Diana (Dee)) Clayton , Oxford Brooks University, UK J. Andres Coca-Stefaniak , University of Greenwich, UK Rui Costa , University of Aveiro, Portugal Juliet Davi s, Cardiff University, UK Leon Davis , Teeside University, UK Emma Delaney , University of Surrey, UK Valerio Della Salla , University of Bologna, UK Anthony Dixon , Troy University, USA Simon Down , University of Birmingham, UK and Högskolan Kristianstad, Sweden Colin Drake , Victoria University, Australia Jason Draper , University of Houston, USA Martin Falk , University of South-Eastern Norway, Norway Nicole Ferdinand , Oxford Brookes University, UK Miriam Firth , University of Manchester, UK Jenny Flynn , University of the West Scotland, UK Carmel Foley , University Technology Sydney, Australia Susanne Gellweiler , Dresden School of Management, Germany David Gogishvili , University of Lausanne, Switzerland John Gold , University College of London, UK Barbara Grabher , University of Graz, Austria Jeannie Hahm , University Central Florida, UK Kirsten Hallman , German Sport University Cologne, Germany Elizabeth Halpenny , University of Alberta, Canada Marcus Hansen , Liverpool John Moores University, UK Luke Harris , University of Birmingham, UK Najmeh Hassanli , University of Technology Sydney, Australia Burcin Hatipoglu , University New South Wales, Australia Ted Hayduck , New York University, USA Christopher Hautbois , University of Paris, France Claire Haven-Tang , Cardiff Metropolitan University, UK Freya Higgins-Desbiolles , University of South Australia, Australia Yoshifusa Ichii , Ritsumeikan University, Japan Jiyoung Im , Oklahoma State University, USA Dewi Jaimangal-Jones , Cardiff Metropolitan University, UK David Jarman , Edinburgh Napier University, UK Allan Jepson , Herts University, UK Eva Kassens-Noor , Michigan State University, USA Jamie Kenyon , Loughborough University, UK Seth Kirby , Nottingham Trent University, UK Brendon Knott , Cape Peninsula University of Technology, South Africa Nicole Koenig-Lewis , Cardiff University, UK Joerg Koenigstorfer , Technical University of Munich, Germany Maximiliano Korstanje , University of Palermo, Argentina Niki Koutrou , Bournemouth University, UK Martinettte Kruger , North-West University, South Africa Jeetesh Kumar , Taylor’s University, Malaysia Ian Lamond , Leeds Beckett University, UK Weng Si (Clara) Lei, Macao Institute for Tourism Studies, China Clifford Lewis , Charles Sturt University, Australia Jason Li , Sun Yat-sen University, China Ying (Tracy) Lu, University of Kentucky, USA Mervi Luonila , Center for Cultural Policy Research, Finland Erik Lundberg , University of Gothenburg, Sweden Emily Mace , Angila Ruskin University, UK Judith Mair , University of Queensland, Australia Matt McDowell , University of Edinburgh, UK Majd Megheirkouni , Leeds Trinity University, UK Jonathan Moss , Leeds Beckett University, UK James Musgrave , Leeds Beckett University, UK Barbara Neuhofer , University of Salzburg, Austria Margarida Abreu Novais , Griffith University, Australia Pau Obrador , Northumbria University, UK Danny O’Brien , Bond University, Australia Eric D. Olson , Metropolitan State University of Denver, USA Faith Ong , University of Queensland, Australia Emilio Fernandez Pena , Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona, Spain Marko Perić , University of Rijeka, Croatia Hongxia Qi , Victoria University Wellington, New Zealand Meng Qu (Mo), Hokkaido University, Japan Bernadette Quinn , Dublin Institute of Technology, Ireland Tareq Rasul , Australian Institute of Business, Australia Vanessa Ratten , La Trobe University, Australia Tiago Ribeiro , University of Lisbon, Portugal Alector Ribiero , University of Surrey, UK Ivana Rihova, Edinburgh Napier University, UK Giulia Rossetti, Oxford Brooks University, UK Darine Sabadova , University of Surrey, UK Katie Schlenker , University Technology Sydney, Australia Hugues Seraphin , Winchester University, UK Ranjit Singh , Pondicherry University, India Ryan Snelgrove , University of Waterloo, Canada Sarah Snell , Edinburgh Napier University, UK Sonny Son , University of South Australia, Australia Raphaela Stadler , Management Center Innsbruck, Austria Effie Steriopoulos , William Angliss Institute, Australia Nancy Stevenson , University of Westminster, UK Erose Sthapit , Manchester Metropolitan University, UK Ching-Hui (Joan) Su , Iowa State University, USA Kamilla Swart-Arries , Hamad Bin Khalifa University, Qatar Adam Talbot , Coventry University, UK Jessica Templeton , University of Greenwich, UK Aaron Tham , University of the Sunshine Coast, Australia Eleni Theodoraki , University of Dublin, UK Jill Timms , University of Surrey, UK Sylvia Trendafilova , University of Tennessee, USA Danai Varveri, Metropolitan College, Greece Peter Vlachos , University of Greenwich, UK Trudie Walters , Canterbury Museum and Lincoln University, New Zealand Xueli (Shirley) Wang , Tsinghua University, China Stephen Wassong , German Sport University, Germany Craig Webster , Ball State University, USA Jon Welty Peachey , Gordon College, USA Kim Werner , Hochschule Osnabrück, Germany Mark Wickham , University of Tasmania, Australia Jessica Wiitala , High Point University, USA Kyle Woosnam , University of Georgia, USA Jialin (Snow) Wu , University of Huddersfield, UK Sakura Yamamura , Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity, Germany Nicole Yu, The University of Queensland, Australia Pamela Zigomo , University of Greenwich, UK PhD/ECR Editorial Board Erik L. Lachance , University of Ottawa, Canada ( Chair of the PhD/ECR Editorial Board ) Oluwaseyi Aina , University of the West of Scotland, UK Sarah Ariai, University of Waterloo, Canada Elizabeth Ashcroft , University of Surrey, UK Jibin Baby , North Carolina State University, USA Jordan T. Bakhsh , University of Ottawa, Canada Sara Belotti , University of Bergamo, Italy Nicola Cade , University of Essex, UK Libby Carter , Birmingham City University, UK David Cook , Coventry University, UK Karen Davies, Cardiff Metropolitan University, UK Skyler Fleshman , University of Florida, USA Alexia Gignon , University of Gustave Eiffel, France Chris Hayes , Teeside University, UK Mu He , University of Alberta, Canada Meg Hibbins , University of Technology Sydney, Australia Jie Min Ho , Curtin University, Australia Montira Intason , Naresuan University, Thailand Shubham Jain , University of Cambridge, UK Orighomisan Jekhine , Leeds Beckett University, UK Denise Kamyuka , Western University, Canada Wanwisa Khampanya , University of Surrey, UK Jason King , Leeds Beckett University, UK Truc Le , Griffith University, Australia Kelly McManus , University of Waterloo, Canada Adam Pappas , University of Waterloo, Canada Heelye Park , Iowa State University, USA Jihye Park , University of Central Florida, USA Erin Pearson , Western University, Canada Benedetta Piccio , Edinburgh Napier University, UK Juliana Rodrigues Vieira Tkatch , University of Central Florida, USA Claire Roe , University of Derby, UK Briony Sharp , University of the West of Scotland, UK Smita Singh , Metropolitan State University of Denver, USA Darina Svobodova , University of Surrey, UK Georgia Teare , University of Ottawa, Canada Yann Tournesac , Leeds Beckett University, UK Katy Tse , University of Surrey, UK Beau Wanwisa , University of Surrey, UK Ryutaro Yamakita , University of Ottawa, Canada Emmy Yeung , University of Chester, UK Ryuta Yoda , Coventry University, UK Azadeh Zarei , The University of Queensland, Australia

Special Issue: Technology Enabled Competitiveness and Experiences in Events

The special issue is supported by the International Conference ( THE INC 2024 ) “Technology Enabled Competitiveness and Experiences in Tourism, Hospitality and Events”, which is the official conference of ATHENA (Association of Tourism Hospitality and Events Networks in Academia) , and will be held from 5th till 7th June 2024 in Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Guest Editors Dr. Eleni Michopoulou, University of Derby, United Kingdom Email: [email protected]

Dr. Iride Azara, University of Derby, United Kingdom Email: [email protected]

Prof. Nikolaos Pappas, University of Sunderland, United Kingdom Email: [email protected]

In recent years, several studies have been dedicated to event-related technological aspects, often under the prism of experience design, event thinking and interaction, or focusing on the artificial intelligence and robots. However, those studies have only just began to explore the underpinning principles and aspects of the contribution of technology in business competitiveness and the formulation of consumer experiences. Moreover, the event-related theoretical and applied aspects of technology need to be approached from a multidisciplinary point of view, to enable a better understanding of the internal and external dynamics that affect their evolution and development.

This special issue welcomes theoretical, empirical, experimental, and case study research contributions. These contributions should clearly address the theoretical and practical implications of the research in reference. Both conceptual and empirical work are welcome. The event-related technology enabled competitiveness and experiences can be viewed under a variety of prisms, including but not limited to:

- Competitiveness, sustainability and corporate social responsibility

- Consumer behaviour, decision-making, expectations, experience and satisfaction

- Smart events cities / destinations / infrastructure

- Culture, heritage, place -making and storytelling in events

- AR/VR/XR, Metaverse

- Human resources, equality, diversity, and labour operations in events

- Robotics, AI, Internet of Things, Big Data Analytics

- Emerging and innovative research methods and methodologies

- Sharing/gig economy, collaborative consumption, value co-creation

- Innovation, creativity and change management

- IT, ICT, e-tourism, social media, gamification and mobile technologies

- Marketing, advertising, branding and reputation management in events

- Policy, planning, and governance

- Health, well-being, quality of life and wellness

- Training and events education

- Other interdisciplinary areas related with events

Review Process Each paper submitted for publication consideration is subjected to the standard review process designated by the Event Management journal. Based on the recommendations of the reviewers, the Editor-in-chief along with the guest editors will decide whether particular submissions will be accepted, revised or rejected. Please note that the review process will start after the full paper submission deadline.

Submission Guidelines Please submit the papers to the journal’s online platform under the Submission Guidelines tab.

Full Paper Submission Deadline: Sunday, 16th March 2024. Expected Publication Date: Mid or end of 2025.

Note: Please be advised that the review process will start after the submission deadline.

All papers should follow the submission guidelines of the Event Management journal.

Submission Guidelines – Please view Cognizant AI Policy here

Our aim is to make initial submission to Event Management as simple as possible, for all submission routes. Authors can use the following information as a checklist before submitting.

HOW TO SUBMIT: All manuscripts to be submitted via this link:

WHAT TO SUBMIT: Authors are asked to submit four documents:

- Impact Statement

- Submission Checklist ( Click here for the Submission Checklist )

Please note: After you have received the first round of peer review comments and you are responding to reviewers’ comments, please ensure you attach a ‘Response to Reviewers’ document on Step 2: File Upload . This will make it easier for the reviewers to see where changes have been made in relation to peer review comments, and how and why you have attended to all peer reviewer points.

Cover letters are optional but we do encourage authors to also provide this to help detail the theoretical, empirical, and/or practical contribution of the manuscript.

WHAT TO INCLUDE IN YOUR “IMPACT STATEMENT”: up to 500 words detailing the potential or actual impact of this article on society.

WHAT TO INCLUDE IN YOUR “TITLE PAGE”: Please ensure all of the following headings are present and addressed:

- Title (20 words max)

- Author(s) name

- Affiliation (Department, Institution, City, (State), Country)

- Corresponding author and email address

- Corresponding author ORCID

- Declaration of interest

- Part of a Special Issue? If so, state the name of the Special Issue.

WHAT TO INCLUDE AND HOW TO FORMAT MANUSCRIPTS: We provide authors with the flexibility to format and organize manuscripts in they way they prefer for initial submission. Authors will then work with our editorial assistants after acceptance to conform with journal standardized format before publication. We do however have a simple checklist of things below we do require at initial submission stage:

Sections to include:

- Title (up to 20 words, in CAPITAL LETTERS and BOLD )

- Highlights (3-5 highlights, max 80 characters including spaces for each bullet point)

- Abstract (150 words max)

- Keywords (up to 8, placed immediately after the Abstract)

- A “Literature Review” and “Methodology” section must feature, unless not appropriate.

Formatting requirements

- Word document in Arial font, size 10 or 12.

- All manuscripts should be thoroughly checked for spelling and grammar.

- All in-text citations and References must be submitted following APA Publication Manual, 7th edition (see https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/apa_style/apa_formatting_and_style_guide/apa_changes_7th_edition.html and/or the 7th APA author quick guide changes ).

- For a sample published article choose an open access file on the online Ingenta Connect site ( https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/cog/em )

- Double spaced, with line numbering and page numbers.

- ‘Tables’ and high quality ‘Images’ and ‘Figures’ to be uploaded as separate files.

- Word counts indicated below are the maximum for all sections including tables, figure legends and appendices.

- Clearly identifiable headings with no more than three levels (see example below). 1. HEADING, 1.1 Sub-heading 1.1.1 Sub-sub-heading .

SUBMISSION TYPES:

- Research article (up to 10,000 words)—traditional full-length research articles contribute to theory.

- Research note (up to 2,500 words)—short pieces that are theoretically or methodologically relevant, novel and innovative that can be developed further and advanced by other scholars. Commentaries and debates can be submitted under this submission type too.

- Event case study (up to 10,000 words)—full-length empirically based research articles that rigorously apply theory but do not necessarily seek to develop theory. Authors must however stress the implications of empirical work beyond the event case study context.

- Event education (up to 10,000 words)—full-length pieces focusing on events-related learning and teaching innovation and impact on student education, experience, and performance.

GENERAL AND SPECIFIC QUESTIONS EDITORS AND REVIEWERS WILL CONSIDER WHEN EVALUATING MANUSCRIPTS

General questions:

- Is there a clear research issue or problem statement presented at the beginning that establishes the “so what” factor?

- Is the theoretical, methodological, or empirical contribution of the manuscript clearly stated? And is the significance of this contribution clearly stated?

- Is the manuscript interesting, bold, and/or innovative?

- Is the theoretical framework robust, providing a good conceptual grounding in relevant literature?

- Is the methodology designed and executed in a reliable and valid way?

- Is the manuscript written in a clear and concise way (without “academese”) and accessible to academic and nonacademic audiences?

- Is the argument written in an easy to follow and logical way?

- Are there clear conceptual and practical conclusions drawn on in the latter parts of the manuscript?

- Which of the following submission routes do you think the manuscript is best suited for: – Research article (strong theoretical or methodological contribution) – Research Note (shortened version with a strong theoretical or methodological contribution) – Event Case Study (limited theoretical or methodological contribution, but interesting empirical insights) – Events Education

Specific events-related questions:

- Does the manuscript present an analysis of contemporary events-related issues?

- Does the manuscript present a balanced perspective on the power and potential of events for good or for bad?

- Do you think this manuscript helps advance events research: how and why?

- Are there clear and well-justified recommendations to help advance the policy and practice of events in the future?

- Does the manuscript present a future academic research agenda that seeks to push the boundaries of events research?

- Is it clear how either descriptive or conceptual features of the event in question impacts on the empirical phenomenon in question? (In other words, does the author position the event simply as the “background” or “context” or are distinct features of the event recognized?)

NB: We ask this last question because in Event Management journal we want continue building a more conceptual understanding as to why events and festivals are particularly interesting organizational constructs to advance theory and knowledge, over let’s say other types of organizations like businesses or government institutions.

ONLINE FAST-TRACK PUBLICATION

Accepted manuscripts will be loaded to Fast Track with DOI links online. Fast Track is an early e-pub system whereby subscribers to the journal can start reading and citing the articles prior to their inclusion in a journal issue. Please note that articles published in Fast Track are not the final print publication with proofs. Once the accepted manuscript is ready to publish in an issue of the journal, the corresponding author will receive a proof from our Production Department for approval. Once approved and published, the Fast Track version of the manuscript is deleted and replaced with the final published article. Online Fast Track publication ensures that the accepted manuscripts can be read and cited as quickly as possible.

- Use of Copyright Material: Authors must attest their manuscript contains original work and provide proof of permission to reproduce any content(artwork, photographs, tables, etc.) in connection with their manuscript, also ensuring their work does not infringe on any copyright and that they have obtained permission for its use. It is important to note that any and all materials obtain via the Internet/social media (including but not limited to Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, etc.) fall under all copyright rules and regulations and permission for use must be obtained prior to publication.

- Copyright: Publications are copyrighted for the protection of authors and the publisher. A Transfer of Copyright Agreement will be sent to the author whose manuscript is accepted. The form must be completed and returned with the final manuscript files(s).

AUTHOR OPTIONS

Articles appearing in Event Management are available to be open access and may also contain color figures (not a condition for publication). Authors will be provided with an Author Option Form, which indicates the following options. The form must be completed and returned with the final manuscript file(s) even if the answer is “No” to the options. This form serves as confirmation of your choice for the options.

A Voluntary Submission Fee of $125.00 includes one free page of color and a 50% discount on additional color pages (color is discounted to $50.00 per color page). (Not a condition for publication).

Open Access is available for a fee of $200.00. Color would be discounted to $50.00 per color page. (Not a condition for publication).

The use of Color Figures in articles is an important feature. Your article may contain figures that should be printed in color. Color figures are available for a cost of $100.00 per color page. This amount would be discounted to $50.00 per color page if choosing to pay the voluntary submission fee or the open access option as indicated above. (Not a condition for publication).

If you choose any of the above options, a form will be sent with the amount due based on your selection, at proof stage. This form will need to be completed and returned with payment information and any corrections to the proof, prior to publication.

PAGE PROOFS

Page proofs will be sent electronically to the designated corresponding author prior to publication. Minor changes only are allowed at this stage. The designated corresponding author will receive a free pdf file of the final press article, which will be sent by email.

Although every effort is made by the publisher and editorial board to see that no inaccurate or misleading data, opinion, or statement appears in this Journal, they wish to make it clear that the data and opinions appearing in the articles and advertisements herein are the sole responsibility of the contributor or advertiser concerned. Accordingly, the publisher, the editorial board, editors, and their respective employees, officers, and agents accept no responsibility or liabilitywhatsoever for the consequences of any such inaccurate or misleading data, opinion, or statement.

Information about the conference CLICK HERE

Articles appearing in publications are available to be published as Open Access and/or with color figures. A voluntary submission fee is also an option if you choose to support this publication. These options are NOT required for publication of your article.

You may complete the Author Option Payment Form here .

The designated corresponding author will receive a free pdf file of the final press article via email.

Event Management (EM) Peer Review Policy

Peer review is the evaluation of scientific, academic, or professional work by others working in the same field to ensure only good scientific research is published.

In order to maintain these standards, Event Management (EM) utilizes a double-blind review process whereby the identity of the reviewers is not known to authors and the authors are not shown on the article being reviewed.

The peer review process for EM is laid out below:

STEP 1: An article is reviewed for quality, suitability and alignment to the submission formatting guidelines by the Editor-In-Chief and Deputy Editors, and authors will receive either a desk reject, or the article will be progressed to one of our Associate Editors.

STEP 2: If progressed, an Associate Editor will also review for quality and suitability. At this point they may suggest a rejection, or progress and invite reviewers to review the manuscript. We ask reviewers to submit their review within approx. 4-6 weeks (sometimes this can be quicker or slower) and decided is the paper should be an: ‘accept’, ‘minor revision’, ‘major revision’ or ‘reject’.

STEP 3: Authors will then have approx. 4-6 weeks to complete revisions and then resubmit to the journal. The peer review process will then continue until a decision is made by the Associate Editor.

STEP 4: At this point, the article will go to the Editor-In-Chief and Deputy Editors to make a final decision and suggest any final changes required before final acceptance.

STEP 5: After final acceptance, authors will then work with our editorial team to ensure that the article is correctly formatted and suitable for publication. Manuscripts will then be allocated a DOI and uploaded to our fast-track system to have a digital presence online. When the final article is uploaded, we then provide 15 DAYS FREE ACCESS to the article, which can be shared out to networks.

INTERESTED IN BECOMING A REVIEWER FOR EVENT MANAGEMENT JOURNAL?

As a reviewer for Event Management you would have the benefit of reading and evaluating current research in your area of expertise at its early state, thereby contributing to the integrity of scientific exploration.

If you are interested in becoming a reviewer for EM please contact the EIC: Mike Duignan at [email protected]

If you review three papers for one of the Cognizant journals ( Tourism Review International, Tourism Analysis, Event Management, Tourism Culture and Communication, Tourism in Marine Environments, and Gastronomy and Tourism ) within a one-year period, you will qualify for a free OPEN ACCESS article in one of the above journals.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The publishers and editorial board of Event Management have adopted the publication ethics and malpractice statements of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) https://publicationethics.org/core-practices and the COPE position statement regarding Authorship and AI Tools https://publicationethics.org/cope-position-statements/ai-author . These guidelines highlight what is expected of authors and what they can expect from the reviewers and editorial board in return. They also provide details of how problems will be handled. Briefly:

Editorial Board

Event Management is governed by an international editorial board consisting of experts in event management, tourism, business, sport, and related fields. Information regarding the editorial board members is listed on the inside front cover of the printed copy of the journal in addition to the homepage for the journal at: https://www.cognizantcommunication.com/journal-titles/event-management under the “Editorial Board” tab.

This editorial board conducts most of the manuscript reviews and plays a large role in setting the standards for research and publication in the field. The Editor-in-Chief receives and processes all manuscripts and from time to time will modify the editorial board to ensure a continuous improvement in quality.

The reviewers uphold a peer review process without favoritism or prejudice to gender, sexual orientation, religious/political beliefs, nationality, or geographical origin. Each submission is given equal consideration for acceptance based only on the manuscript’s importance, originality, academic integrity, and clarity and whether it is suitable for the journal in accordance with the Aims and Scope of the journal. They must not have a conflict of interest with the author(s) or work described. The anonymity of the reviewers must be maintained.

All manuscripts are sent out for blind review and the editor/editorial board will maintain the confidentiality of author(s) and their submitted research and supporting documentation, figures, and tables and all aspects pertaining to each submission.

Reviewers are expected to not possess any conflicts of interest with the authors. They should review the manuscript objectively and provide recommendations for improvements where necessary. Any unpublished information read by a reviewer should be treated as confidential.

Manuscripts must contain original material and must not have been published previously. Material accepted for publication may not be published elsewhere without the consent of the publisher. All rights and permissions must be obtained by the contributor(s) and should be sent upon acceptance of manuscripts for publication.

References, acknowledgments, figure legends, and tables must be properly cited and authors must attest their manuscript contains original work and provide proof of permission to reproduce any content (artwork, photographs, tables, etc.) in connection with their manuscript, also ensuring their work does not infringe on any copyright and that they have obtained permission for its use. It is important to note that any and all materials obtain via the Internet/social media (including but not limited to Face Book, Twitter, Instagram, etc.) falls under all copyright rules and regulations and permission for use must be obtained prior to publication.

Authors listed on a manuscript must have made a significant contribution to the study and/or writing of the manuscript. During revisions, authors cannot be removed without their permission and that of all other authors. All authors must also agree to the addition of new authors. It is the responsibility of the corresponding author to ensure that this occurs.

Financial support and conflicts of interest for all authors must be declared.

The reported research must be novel and authentic and the author(s) should confirm that the same data has not been and is not going to be submitted to another journal (unless already rejected). Plagiarism of the text/data will not be tolerated and could result in retraction of an accepted article.

When humans, animals, or tissue derived from them have been used, then mention of the appropriate ethical approval must be included in the manuscript.

The publishers agree to ensure, to the best of their abilities, that the information they publish is genuine and ethically sound. If publishing ethics issues come to light, not limited to accusations of fraudulent data or plagiarism, during or after the publication process, they will be investigated by the editorial board including contact with the authors’ institutions if necessary, so that a decision on the appropriate corrections, clarifications, or retractions can be made. The publishers agree to publish this as necessary so as to maintain the integrity of the academic record.

View All Abstracts

Access Current Articles (Volume 28, Number 2)

Volume 28, Number 2 Coming soon

Full text articles available: CLICK HERE

Back issues of this journal are available online. Order Here

Event Management is indexed in:

AMERICAN PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION/PsycINFO CAB INTERNATIONAL (CABI) C.I.R.E.T. EBSCO DISCOVERY SERVICES GOOGLE ANALYTICS I.B.S.S. /PROQUEST OCLC PRIMO CENTRAL PROQUEST SCOPUS SOUTHERN CROSS UNIVERSITY WEB OF SCIENCE EMERGING SOURCES CITATION INDEX WORLDCAT DISCOVERY SERVICES

Event Management is an “A” category journal with the ABDC (Australian Business Dean’s Council) https://abdc.edu.au/research/abdc-journal-list/

Publishing Information

Copyright Notice : It is a condition of publication that manuscripts submitted to this Journal have not been published and will not be simultaneously submitted or published elsewhere. By submitting a manuscript, the author(s) agree that the copyright for the article is transferred to the publisher, if and when the article is accepted for publication. The copyright covers the exclusive rights to reproduce and distribute the article, including reprints, photographic reproductions, microform, or any other reproductions of similar nature and translations. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without permission in writing from the copyright holder.

Photocopying information for users in the USA: The Item Fee Code for this publication indicates that authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by the copyright holder for libraries and other users registered with the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) Transactional Reporting Service Provided the stated fee for copying beyond that permitted by Section 107 or 108 of the United Stated Copyright Law is paid. The appropriate remittance of $60.00 per copy per article is paid directly to the Copyright Clearance Center Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danver, MA 01923. The copyright owner’s consent does not extend to copying for general distribution, for promotion, for creating new works, or for resale. Specific written permission must be obtained from the publisher for such copying. In case of doubt please contact Cognizant Communication Corporation.

The Item Fee Code for this publication is 1525-9951/10 $60.00

Copyright © 2024 Cognizant, LLC

Printed in the USA

Updated as of December 2023

Number of submissions: 184 Number of reviews requested: 631 Number of reviews received: 411 Approval rate: approximately 31% Average time between submission and publication: 86 days (11.9 weeks)

Robert N. Miranda, Publisher/Chairman Lori H. Miranda, President/COO

P.O. Box 37 Putnam Valley, NY 10579 USA

Phone: (845) 603-6440 Fax: (845) 603-6442

[email protected] [email protected]

About Cognizant

Cognizant Policies

Publications

Active Journals

Previously Published Journals

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use | Contact Us | Help

Copyright ©2024 Cognizant LLC. All rights reserved Cognizant Communication Corporation | P.O. Box 37 | Putnam Valley, NY 10579 | U.S.A.

.css-s5s6ko{margin-right:42px;color:#F5F4F3;}@media (max-width: 1120px){.css-s5s6ko{margin-right:12px;}} Join us: Learn how to build a trusted AI strategy to support your company's intelligent transformation, featuring Forrester .css-1ixh9fn{display:inline-block;}@media (max-width: 480px){.css-1ixh9fn{display:block;margin-top:12px;}} .css-1uaoevr-heading-6{font-size:14px;line-height:24px;font-weight:500;-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;color:#F5F4F3;}.css-1uaoevr-heading-6:hover{color:#F5F4F3;} .css-ora5nu-heading-6{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-box-pack:start;-ms-flex-pack:start;-webkit-justify-content:flex-start;justify-content:flex-start;color:#0D0E10;-webkit-transition:all 0.3s;transition:all 0.3s;position:relative;font-size:16px;line-height:28px;padding:0;font-size:14px;line-height:24px;font-weight:500;-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;color:#F5F4F3;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover{border-bottom:0;color:#CD4848;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover path{fill:#CD4848;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover div{border-color:#CD4848;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover div:before{border-left-color:#CD4848;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:active{border-bottom:0;background-color:#EBE8E8;color:#0D0E10;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:active path{fill:#0D0E10;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:active div{border-color:#0D0E10;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:active div:before{border-left-color:#0D0E10;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover{color:#F5F4F3;} Register now .css-1k6cidy{width:11px;height:11px;margin-left:8px;}.css-1k6cidy path{fill:currentColor;}

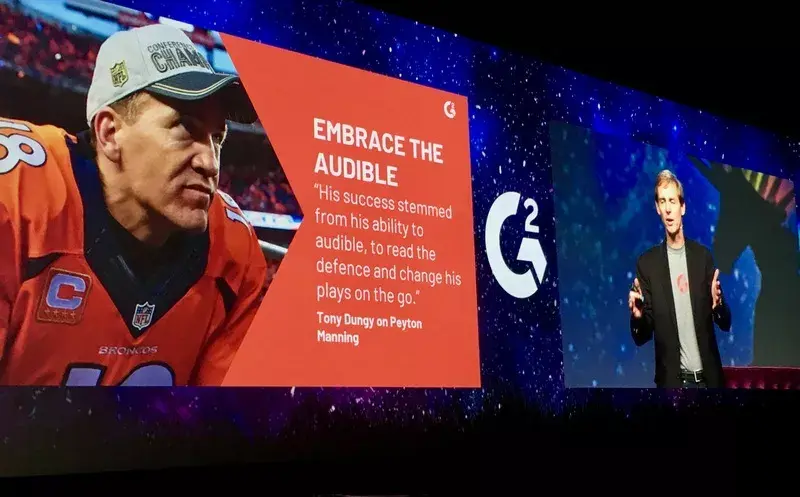

G2 produces 2X more global events with Asana

Expanding events program.

Events program has grown 2X year over year

Reduced planning time

Cut down event planning time by 80%

40+ hours saved per quarter on event check-in meetings

G2 is a B2B software and services review platform that millions of buyers and vendors rely on around the world. Events are a key channel the marketing team uses to engage these two audiences. Led by Adam Goyette, Vice President of Demand Generation, the events team produces 150+ events every year, from paid review booths for their clients to major conference sponsorships and demand generation dinners to build pipeline for their sales team.

To ensure all of these events go off without a hitch, Adam has a team of four full-time employees, 30+ contractors, and countless cross-functional partners to coordinate logistics, creative production, sales materials, and promotion. To support G2’s growing event needs, Adam knew he had to put processes and tools in place that would allow the team to scale.

As he looked to scale the team, Adam faced some common operational challenges:

Event plans were scattered across spreadsheets, emails, and meeting notes so there was no way to organize and track everything in one place or hold people accountable for tasks and deadlines.

Past event plans and vendor information were siloed in separate tools, making knowledge sharing a struggle when onboarding new teammates.

Event plans and processes weren’t standardized, so the team had to plan from scratch every time, resulting in missed steps and no way to continually optimize their processes.

The team struggled to delegate and assign work to others because they were used to managing every detail themselves. And since processes weren’t documented, it was difficult for cross-functional partners to jump into projects when needed.

Adam realized they needed to develop standard event processes to scale the program successfully. Additionally, their event plans needed to be accessible by everyone so they could coordinate with contractors, cross-functional partners, and vendors.

We’ve created templates for events we do often, which cuts down our planning time by 80%. Now the time we do spend on each event is used to customize it and improve it. ”

Centralizing event work and processes in one view

While the G2 marketing team had tried other work management tools in the past, none of them stuck. Then Ryan Bonnici joined the company as its Chief Marketing Officer and introduced the team to Asana, which he’d used with his teams at previous companies. Compared to other tools, Adam found Asana to be the most intuitive, flexible, and powerful solution for managing different event workflows and collaborating with cross-functional teammates.

As our team expanded, we needed a tool that allowed us to coordinate complex events and provide visibility into how plans were progressing without having to rely on email and meetings. Asana has made it easy to track every task and deadline in one place, which saves us 40+ hours a quarter in meetings. ”

To ensure adoption, the marketing team developed conventions and best practices to create event management processes at G2—all of which are standardized. The team then began planning, assigning, and tracking event work only in Asana. With a centralized system of record, work is no longer scattered across email, spreadsheets, and meetings notes. This ensures that event plans are trackable and accessible to the entire team for easier knowledge sharing and collaboration. Adam also invited contractors into Asana and then to relevant events they were supporting so they could coordinate logistics with the internal team in one place.

Successfully scaling the event program with Asana

Adam’s team has now centralized all of their event plans—vendor contracts, day-of checklists, creative production, and more—in Asana so everyone has visibility, and they’ve also created project templates with detailed workback schedules to reduce planning time. Additionally, the team has integrated Asana with Slack so they can turn messages into tasks—or take action on tasks right from Slack—when they’re on site at events. This helps them keep everything connected and allows them to work seamlessly, whether they’re in the office or on site.

Now that we’re managing events in Asana, we’ve been able to double the number of events we host, which has helped us generate more customer reviews for our vendors and create new sales pipeline for the company. ”

By centralizing and standardizing their event plans in Asana, the team has been able to scale successfully, reduce their planning time by 80%, and produce twice as many events across three continents to generate software reviews, drive sales pipeline, and hit revenue targets. They continue to optimize their event processes based on new learnings, and with ambitious plans to accelerate their growth, they’re ready to manage even more events with the help of Asana.

Read related customer stories

Spotify teams drive programs forward with Asana

Appen improves operating efficiency with Asana

Coupa scales to support customers with Asana

iCHEF supercharge productivity and collaboration with Asana

Get connected and scale your work

Empower your entire organization to do their best work with Asana.

Integrating Business Processes to Improve Travel Time Reliability (2011)

Chapter: chapter 5 - case studies: special-event management.

Below is the uncorrected machine-read text of this chapter, intended to provide our own search engines and external engines with highly rich, chapter-representative searchable text of each book. Because it is UNCORRECTED material, please consider the following text as a useful but insufficient proxy for the authoritative book pages.

C H A P T E R 5 Case Studies: Special-Event ManagementSpecial events present a unique case of demand fluctuation that causes traffic flow in the vicinity of the event to be radically dif- ferent from typical patterns. Special events can severely affect reliability of the transportation network, but because the events are often scheduled months or even years in advance, they offer an opportunity for planning to mitigate the impacts. Because large-scale events are recurring at event venues, it gives an opportunity for agencies to continually evaluate and refine strategies, impacts, and overall process improvements over time. In this section, case studies are presented that examine the processes developed for special-event management at the Kansas Speedway in Kansas City, Kans., and the Palace of Auburn Hills near Detroit, Mich. Kansas: Kansas Speedway In 2001, the Kansas Speedway opened for its first major NASCAR race. With attendance exceeding 110,000 people, it set a record as the largest single-day sporting event in the his- tory of Kansas. Attendance has continued to grow and now exceeds 135,000 for most major races. The traffic control strategies that were put into place to handle these major events were the result of years of planning between the Kansas Speed- way, Kansas Highway Patrol (KHP), Kansas Department of Transportation (KDOT), and the Kansas City Police Depart- ment. The process was successful in part because of the clear lines of responsibility that were defined for each agency and the strong spirit of cooperation and trust that was established before the first race was held. In preparation for this case study, representatives from KHP and KDOT were interviewed. Lt. Brian Basore and Lt. Paul Behm represented the KHP Troop A and were able to share their experience from many years of actively managing special events at the Kansas Speedway. The primary responsibilities of KHP are to operate the KHP Command Center that was estab- lished for the Kansas Speedway race events and to manage 45traffic on the freeways around the event. Representatives of KDOT who were interviewed included Leslie Spencer Fowler, ITS program manager, and Mick Halter, PE, who was formerly with KDOT as the District One metro engineer during the design and implementation of the Kansas Speedway. Fowler and Halter provided an excellent history of the development of the project, as well as a description of KDOTâs current opera- tional procedures used during races at the Kansas Speedway. KDOT maintains the CCTV cameras and portable DMS around the Speedway and assists KHP with traffic control on the freeways. Description This case study examines the development of the special-event management procedures for races at the Kansas Speedway. Par- ticular focus is given to the roles and responsibilities of the KHP and KDOT in developing the initial infrastructure and strate- gies that led to a successful special-event management process that has been used and refined for 8 years. One of the strongest recurring themes in development of this case study was the out- standing cooperation and partnerships that were developed between the agencies involved. Each agency has clearly defined responsibilities before and on race day, though no agency is considered in charge. They cooperate to safely and efficiently move vehicles from the freeways to city streets to the Kansas Speedway parking lots and then do the same process in reverse. Background of Agency The Kansas Speedway is a 1.5-mi oval race track suitable for many types of races, including Indy and NASCAR. Seating capacity is currently being expanded to 150,000 people, and parking capacity allows for 65,000 vehicles. The Speedway is located approximately 15 mi west of downtown Kansas City, near the intersection of I-70 and I-435, which serve as the pri- mary routes used by spectators attending the races. Events are

46held throughout the year, and there are typically two major race events each year when crowds reach capacity. The major- ity of parking is on Kansas Speedway property and is free for spectators. The Kansas Speedway provides attendants and directs vehicles into the parking areas. The primary agencies involved in traffic management for the Kansas Speedway include KHP Troop A in Kansas City, KDOT District One, and the Kansas City Police Department. KHP is responsible for traffic management on the freeways and for operation of the KHP Command Center, which is activated several days before major events and serves as the central com- munications center for all public agencies on race day. The full resources of Troop A (over 40 troopers) are used on race day, along with over 20 other troopers from around the state. KHP also deploys a helicopter to monitor traffic from the air and roving motorcycle units on race day. KDOT District One is responsible for maintaining five CCTV cameras and deploy- ing 12 portable DMSs on roads used to access the Speedway. The Kansas City Police Department provides officers for the city street network that links the freeways to the Kansas Speedway (1). Other participants in the process include Wyandotte County and the Kansas Turnpike Authority (KTA). Wyandotte County currently owns the WebEOC software used by all participat- ing agencies to share information and request assistance on race day (2). The KTA maintains I-70 near the Speedway. It is responsible for such maintenance tasks on this section of I-70 as snow and ice removal, guardrail, and signing and striping, although the section is not tolled. Process Development The Kansas Speedway opened for its first major event in sum- mer 2001. However, development of the process for special- event traffic management began long before Kansas City was even selected as the site for the racetrack. In the early 1990s the International Speedway Corpora- tion was searching for a new location for a race track in the Midwest. The track was expected to host several large events per year, including at least one to two major races that were expected to attract more than 100,000 people. Given the poten- tial positive economic benefit that such a facility could bring to an area, the International Speedway Corporation solicited pro- posal packages from several sites under consideration. Propos- als needed to address criteria established by the International Speedway Corporation for site selection, including accessibil- ity of the site to attendees. The effort to bring the race track to Kansas was led by Kansas City, with strong support from the governor and lieutenant governor of Kansas. Understanding the importance of accessibility, the governor directed KDOT to develop a plan and provide funding to make the necessary infrastructure improvements to handle race traffic for theSpeedway. The priority placed on this project by the governorâs office served as the first enabler to implementing the traffic management process. KDOT developed an extensive plan to accommodate the large number of vehicles expected to attend events at the Kansas Speedway. I-70 needed to be widened and a new inter- change was needed at 110th Street. US-24, which went through the proposed site of the track, needed to be completely realigned. Although not part of the original planning, CCTV cameras and portable DMS were also required to assist with traffic management. KDOT identified funding for each of their proposed infrastructure projects, and these projects were included in the package that was submitted to the International Speedway Corporation. More than a year before the first race event at the Kansas Speedway, all the agencies involved in traffic management began planning for the event. Agencies that participated in the planning included KHP, KDOT, KTA, Kansas City Police, Wyandotte County, and the Kansas Speedway. The Missouri DOT and Missouri Highway Patrol were also initially involved because there was concern that traffic could be affected east of the track into Missouri. (Once the Speedway opened, it turned out that this concern was unfounded as race traffic had only minor impacts on I-70 near the Speedway and did not affect traffic on I-70 in Missouri.) To facilitate traffic management planning, a consultant also was brought on-board early in the process. The success of the planning for traffic management was attributed to two primary factors. The first was the importance that the governor and Kansas City placed on the success of hosting major races at the Kansas Speedway. Millions of dol- lars were invested by the state and city to bring the race track to Kansas, and to recoup their investment they needed to suc- cessfully host large races. The visibility and importance of the first successful event was a great motivator for every agency involved. The second factor to which success was attributed was the personalities involved. Several of those interviewed for this case study noted that there were no egos in the room that got in the way. A sense of mutual respect among the agencies and for their work was a consistent factor in planning for traffic management. No single agency was designated as âin chargeâ; rather, each agency took responsibility for its piece and worked well with the other agencies to ensure overall success. The result of the planning efforts was a multilayered traffic plan with different agencies leading the layers. The first layer dealt with interstate traffic, which was KHPâs responsibility. The second layer dealt with traffic on local streets traveling between the interstates and the Kansas Speedway, this layer was the responsibility of the Kansas City Police Department. The third layer handled traffic entering or leaving the track property, which was the responsibility of the Kansas Speed- way. KDOT provided support to all three layers through