- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: April 20, 2023 | Original: October 7, 2010

Apartheid, or “apartness” in the language of Afrikaans, was a system of legislation that upheld segregation against non-white citizens of South Africa. After the National Party gained power in South Africa in 1948, its all-white government immediately began enforcing existing policies of racial segregation. Under apartheid, nonwhite South Africans—a majority of the population—were forced to live in separate areas from whites and use separate public facilities. Contact between the two groups was limited. Despite strong and consistent opposition to apartheid within and outside of South Africa, its laws remained in effect for the better part of 50 years. In 1991, the government of President F.W. de Klerk began to repeal most of the legislation that provided the basis for apartheid.

Apartheid in South Africa

Racial segregation and white supremacy had become central aspects of South African policy long before apartheid began. The controversial 1913 Land Act , passed three years after South Africa gained its independence, marked the beginning of territorial segregation by forcing Black Africans to live in reserves and making it illegal for them to work as sharecroppers. Opponents of the Land Act formed the South African National Native Congress, which would become the African National Congress (ANC).

Did you know? ANC leader Nelson Mandela, released from prison in February 1990, worked closely with President F.W. de Klerk's government to draw up a new constitution for South Africa. After both sides made concessions, they reached agreement in 1993, and would share the Nobel Peace Prize that year for their efforts.

The Great Depression and World War II brought increasing economic woes to South Africa, and convinced the government to strengthen its policies of racial segregation. In 1948, the Afrikaner National Party won the general election under the slogan “apartheid” (literally “apartness”). Their goal was not only to separate South Africa’s white minority from its non-white majority, but also to separate non-whites from each other, and to divide Black South Africans along tribal lines in order to decrease their political power.

Apartheid Becomes Law

By 1950, the government had banned marriages between whites and people of other races, and prohibited sexual relations between Black and white South Africans. The Population Registration Act of 1950 provided the basic framework for apartheid by classifying all South Africans by race, including Bantu (Black Africans), Coloured (mixed race) and white.

A fourth category, Asian (meaning Indian and Pakistani) was later added. In some cases, the legislation split families; a parent could be classified as white, while their children were classified as colored.

A series of Land Acts set aside more than 80 percent of the country’s land for the white minority, and “pass laws” required non-whites to carry documents authorizing their presence in restricted areas.

In order to limit contact between the races, the government established separate public facilities for whites and non-whites, limited the activity of nonwhite labor unions and denied non-white participation in national government.

Apartheid and Separate Development

Hendrik Verwoerd , who became prime minister in 1958, refined apartheid policy further into a system he referred to as “separate development.” The Promotion of Bantu Self-Government Act of 1959 created 10 Bantu homelands known as Bantustans. Separating Black South Africans from each other enabled the government to claim there was no Black majority and reduced the possibility that Black people would unify into one nationalist organization.

Every Black South African was designated as a citizen as one of the Bantustans, a system that supposedly gave them full political rights, but effectively removed them from the nation’s political body.

In one of the most devastating aspects of apartheid, the government forcibly removed Black South Africans from rural areas designated as “white” to the homelands and sold their land at low prices to white farmers. From 1961 to 1994, more than 3.5 million people were forcibly removed from their homes and deposited in the Bantustans, where they were plunged into poverty and hopelessness.

Opposition to Apartheid

Resistance to apartheid within South Africa took many forms over the years, from non-violent demonstrations, protests and strikes to political action and eventually to armed resistance.

Together with the South Indian National Congress, the ANC organized a mass meeting in 1952, during which attendees burned their pass books. A group calling itself the Congress of the People adopted a Freedom Charter in 1955 asserting that “South Africa belongs to all who live in it, Black or white.” The government broke up the meeting and arrested 150 people, charging them with high treason.

Sharpeville Massacre

In 1960, at the Black township of Sharpeville, the police opened fire on a group of unarmed Black people associated with the Pan-African Congress (PAC), an offshoot of the ANC. The group had arrived at the police station without passes, inviting arrest as an act of resistance. At least 67 people were killed and more than 180 wounded.

The Sharpeville massacre convinced many anti-apartheid leaders that they could not achieve their objectives by peaceful means, and both the PAC and ANC established military wings, neither of which ever posed a serious military threat to the state.

Nelson Mandela

By 1961, most resistance leaders had been captured and sentenced to long prison terms or executed. Nelson Mandela , a founder of Umkhonto we Sizwe (“Spear of the Nation”), the military wing of the ANC, was incarcerated from 1963 to 1990; his imprisonment would draw international attention and help garner support for the anti-apartheid cause.

On June 10, 1980, his followers smuggled a letter from Mandela in prison and made it public: “UNITE! MOBILIZE! FIGHT ON! BETWEEN THE ANVIL OF UNITED MASS ACTION AND THE HAMMER OF THE ARMED STRUGGLE WE SHALL CRUSH APARTHEID!”

President F.W. de Klerk

In 1976, when thousands of Black children in Soweto, a Black township outside Johannesburg, demonstrated against the Afrikaans language requirement for Black African students, the police opened fire with tear gas and bullets.

The protests and government crackdowns that followed, combined with a national economic recession, drew more international attention to South Africa and shattered any remaining illusions that apartheid had brought peace or prosperity to the nation.

The United Nations General Assembly had denounced apartheid in 1973, and in 1976 the UN Security Council voted to impose a mandatory embargo on the sale of arms to South Africa. In 1985, the United Kingdom and United States imposed economic sanctions on the country.

Under pressure from the international community, the National Party government of Pieter Botha sought to institute some reforms, including abolition of the pass laws and the ban on interracial sex and marriage. The reforms fell short of any substantive change, however, and by 1989 Botha was pressured to step aside in favor of another conservative president, F.W. de Klerk, who had supported apartheid throughout his political career.

When Did Apartheid End?

Though a conservative, De Klerk underwent a conversion to a more pragmatic political philosophy, and his government subsequently repealed the Population Registration Act, as well as most of the other legislation that formed the legal basis for apartheid. De Klerk freed Nelson Mandela on February 11, 1990.

A new constitution, which enfranchised Black citizens and other racial groups, took effect in 1994, and elections that year led to a coalition government with a nonwhite majority, marking the official end of the apartheid system.

The End of Apartheid. Archive: U.S. Department of State . A History of Apartheid in South Africa. South African History Online . South Africa: Twenty-Five Years Since Apartheid. The Ohio State University: Stanton Foundation .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

World History Project - 1750 to the Present

Course: world history project - 1750 to the present > unit 8.

- READ: End of Old Regimes

- BEFORE YOU WATCH: Decolonization and Nationalism Triumphant

- WATCH: Decolonization and Nationalism Triumphant

- READ: And Then Gandhi Came — Nationalism, Revolution, and Sovereignty

- READ: Decolonizing Women

- READ: Kwame Nkrumah (Graphic Biography)

- READ: The Middle East and the End of Empire

- READ: Chinese Communist Revolution

- BEFORE YOU WATCH: Chinese Communist Revolution

- WATCH: Chinese Communist Revolution

- BEFORE YOU WATCH: Resisting Colonialism — Through a Ghanaian Lens

- WATCH: Resisting Colonialism - Through a Ghanaian Lens

READ: Apartheid

- End of Empire

First read: preview and skimming for gist

Second read: key ideas and understanding content.

- What was apartheid?

- What were some apartheid laws and policies?

- In what ways does the author argue that apartheid was like Jim Crow in the US South?

- What did the Freedom Charter call for?

- How did the struggle against apartheid get caught up in the Cold War?

- What happened in 1976, in Soweto, that was so important?

- What kinds of international response did protests like these create?

Third read: evaluating and corroborating

- The end of apartheid was a group effort. What changes in “community” within South Africa helped end apartheid. What actions of global “networks” helped end the racist system? Why is it useful to view this important change through both frames?

- This article highlights the communities and networks that resisted apartheid. Can you explain any ways that global and local production and distribution were helpful in ending the system?

What is apartheid?

- Classifying all South Africans into racial categories: "white," "black," and "colored" (mixed race).

- Making it illegal for people to marry across those categories, or even to have sexual relations.

- Mandating segregation (separation of races) in schools and all public facilities.

- Moving all black South Africans into small areas referred to as "homelands" or Bantustans. In total, 30 million black South Africans—over 70 percent of the population—were moved onto 13 percent of South Africa's land.

- Restricting freedom of movement, requiring black South Africans to always carry a "pass book" showing their assigned race and "homeland." Being outside of one's "homeland" was cause for arrest.

- Forbidding black South Africans from owning land outside of the Bantustans.

- Forbidding black labor unions from striking.

- Making it illegal to protest, or to gather in groups large enough to start a protest.

- Denying black people the right to vote, except for local authorities in their Bantustans.

The anti-apartheid movement

A global response.

- Afrikaans is one of the official languages of South Africa. This language evolved from the Dutch, who settled in the area in the seventeenth century.

- Townships in South Africa are sections within urban areas that are usually underdeveloped and non-white.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Athol Fugard

Everything you need for every book you read..

Tsotsi represents South African apartheid (a system of legally enforced segregation and discrimination) as a racist structure that destroys Black South Africans’ lives—even when they aren’t experiencing direct, interpersonal racism. Many of the Black characters’ lives are destroyed by racist apartheid laws despite having little direct contact with racist white people. For example, the Black South African protagonist, Tsotsi , lost his mother in childhood because white police rounded up Black people, including her, whom they suspected of living or working in white areas without the required pass. While one of the policemen did display clear racist attitudes—he called Tsotsi’s mother “kaffir,” a South African racial slur—it was the law, not his individual beliefs, that empowered him to destroy Tsotsi’s family. Tsotsi’s mother’s abduction propelled Tsotsi into homelessness and gang membership. In this sense, though Tsotsi rarely interacts with white people, the racist and white supremacist structure of apartheid changed the direction of his whole life.

Other Black characters similarly suffer from the racist economic and legal structures of apartheid, whether or not they come into regular contact with racist white people: the beggar Morris Tshabalala is crippled in a mining accident as a Black worker in an industry where the profits and gold go to white people. The young mother Miriam Ngidi experiences the disappearance of her husband during his participation in a bus boycott—and although the novel does not explicitly state this fact, major bus boycotts in apartheid South Africa were often protests by the Black population against segregation and economic exploitation of Black workers, which exposed protesters like Miriam’s husband to retaliatory racial violence. And Tsotsi’s fellow gang member Boston becomes a criminal after he forges an employment history for an acquaintance who will go to jail due to racist apartheid laws unless he can prove he has a previous employer. Thus, Tsotsi represents how a racist legal and economic structure like apartheid can harm oppressed people independent of and in addition to the interpersonal prejudice they experience.

Apartheid and Racism ThemeTracker

Apartheid and Racism Quotes in Tsotsi

The knife was not only his weapon, but also a fetish, a talisman that conjured away bad spirits and established him securely in his life.

He didn’t see the man, he saw the type.

Gumboot had been allocated a plot near the centre. He was buried by the Reverend Henry Ransome of the Church of Christ the Redeemer in the township. The minister went through the ritual with uncertainty. He was disturbed, and he knew it and that made it worse. If only he had known the name of the man he was burying. This man, O Lord! What man? This one, fashioned in your likeness.

[Morris] looked at the street and the big cars with their white passengers warm inside like wonderful presents in bright boxes, and the carefree, ugly crowds of the pavement, seeing them all with baleful feelings.

It is for your gold that I had to dig. That is what destroyed me. You are walking on stolen legs. All of you.

Even in this there was no satisfaction. As if knowing his thoughts, they stretched their thin, unsightly lips into bigger smiles while the crude sounds of their language and laughter seemed even louder. A few of them, after buying a newspaper, dropped pennies in front of him. He looked the other way when he pocketed them.

Are his hands soft? he would ask himself, and then shake his head in anger and desperation at the futility of the question. But no sooner did he stop asking it than another would occur. Has he got a mother? This question was persistent. Hasn’t he got a mother? Didn’t she love him? Didn’t she sing him songs? He was really asking how do men come to be what they become. For all he knew others might have asked the same question about himself. There were times when he didn’t feel human. He knew he didn’t look it.

So she carried on, outwardly adjusting the pattern of her life as best she could, like taking in washing, doing odd cleaning jobs in the nearby white suburb. Inwardly she had fallen into something like a possessive sleep where the same dream is dreamt over and over again. She seldom smiled now, kept to herself and her baby, asked no favours and gave none, hoarding as it were the moments and things in her life.

On she came, until a foot or so away the chain stopped her, and although she pulled at this with her teeth until her breathing was tense and rattled she could go no further, so she lay down there, twisting her body so that the hindquarters fell apart and, like that, fighting all the time, her ribs heaving, she gave birth to the stillborn litter, and then died beside them.

Petah turned to David. ‘Willie no good. You not Willie. What is your name? Talk! Trust me, man. I help you.’

David’s eyes grew round and vacant, stared at the darkness. A tiny sound, a thin squeaking voice, struggled out: ‘David…’ it said, ‘David! But no more! He dead! He dead too, like Willie, like Joji.’

So he went out with them the next day and scavenged. The same day an Indian chased him away from his shop door, shouting and calling him a tsotsi. When they went back to the river that night, they started again, trying names on him: Sam, Willie, and now Simon, until he stopped them.

‘My name,’ he said, ‘is Tsotsi.’

The baby and David, himself that is, at first confused, had now merged into one and the same person. The police raid, the river, and Petah, the spider spinning his web, the grey day and the smell of damp newspapers were a future awaiting the baby. It was outside itself. He could sympathize with it in its defencelessness against the terrible events awaiting it.

‘What are you going to do with him?’

‘Keep him.’

He threw back his head, and she saw the shine of desperation on his forehead as he struggled with that mighty word. Why, why was he? No more revenge. No more hate. The riddle of the yellow bitch was solved—all of this in a few days and in as short a time the hold on his life by the blind, black, minute hands had grown tighter. Why?

‘Because I must find out,’ he said.

To an incredible extent a peaceful existence was dependent upon knowing just when to say no or yes to the white man.

It was a new day and what he had thought out last night was still there, inside him. Only one thing was important to him now. ‘Come back,’ the woman had said. ‘Come back, Tsotsi.’

I must correct her, he thought. ‘My name is David Madondo.’

He said it aloud in the almost empty street, and laughed. The man delivering milk heard him, and looking up said, ‘Peace my brother.’

‘Peace be with you’, David Madondo replied and carried on his way.

The slum clearance had entered a second and decisive stage. The white township had grown impatient. The ruins, they said, were being built up again and as many were still coming in as they carried off in lorries to the new locations or in vans to the jails. So they had sent in the bulldozers to raze the buildings completely to the ground.

They unearthed him minutes later. All agreed that his smile was beautiful, and strange for a tsotsi, and that when he lay there on his back in the sun, before someone had fetched a blanket, they agreed that it was hard to believe what the back of his head looked like when you saw the smile.

Apartheid, Its Causes and the Process Essay

The essay on Apartheid, its causes and the process itself is very limited in its explanations, has weak arguments and irrelevant evidence that does neither support nor explain the true reasons, process or the outcome of the struggle between the population and the government. The absence of thesis adds to the confusing structure of the essay, which does not have a clear tone and so, the reader is left with no factual information or true understanding of what really took place and how it happened.

The first point that is mentioned in the work is that the colonization by Europeans and their actions were characterized through the depletion of Gold and diamonds. This is used as a reason for colonization, which led to discrimination of people, based on their race and more specifically, visual color differences. This is not specific and does not explain the true reasons for the colonization. In reality, the white man was spreading the influence of the civilized world and the search for new territories to colonize was in place.

The developed nations were spreading their rule over the parts of the world where people lived more basic and independent lives. The primary causes for colonization were demands for power, greed and more territory (Ellis 90). The fact that people of Africa were of different race or color had nothing to do with the fact that they were oppressed and colonized. If they were of different race or color, the same thing would have happened.

The examples can be seen all over the world, from Asia to North and South America. Another real reason for the overtake of African native population was the fact that the colonizers had a better technology and more advanced weapons. The simple fact that they had the ability and tools to overtake a great amount of people with relative ease, gave them enough power to force their demands and rule over African people.

The work mentions that people were divided into whites, colored, Indians and Blacks. This point is completely irrelevant and has no value. The reality is that people who were colored, Indian and Black were separated from white people and whites were the ones who did the separating of themselves from the rest of the native population. Also, this separation does not show what it has led to. It is mentioned for no reason and is placed in the essay to support no real claim or other point, which could be valid and proved.

The major argument of the essay that Nelson Mandela and his movement were the ones that stopped the Apartheid, is not explained and is not at all clear (Shone 75). How it was done and through what forces is undetermined and unseen. The resistance of people against the white rule is mentioned but this fact is weak, as resistance is obvious at any time when one nation or people are taking over another.

It is stated that “Hundred of black men were sent to jail specifically Robin Island where all forms of abuse were exercised” (Buntman 33). This fact is weak in the following explanation of bonds between prisoners. It is not elaborated on—how did this abuse reflect in the further retaliation of the native population and what were the specific actions, strategies and resistance on the Roben Island.

The manifestation of the bonds is a very significant point historically, but the essay must show evidence that proves and compares how these strengths were used by the people. The same is true when the essay mentions the resistance by Nelson Mandela. It states that he organized a movement and that he was sent to jail.

How he organized the movement and what were the strong points is not explained at all. The mere fact that he was sent to jail does not show how this influenced the change in the resistance and what were the turning and considerable moments of the resistance that had their force over the colonizers is not produced as evidence. Also, Nelson Mandela is said to have been a great leader and supporter of African people.

In which ways he supported them, what were his actions and how specifically he used his authority, as well as understanding of the issue and reasoning in his support, is not clear. This adds to the total confusion and lack of facts throughout the essay. The second last paragraph of the essay mentions that women played an important role in the movement and resistance against the oppression and Apartheid. There are no examples or techniques given that display how women have used their resources to resist the colonization.

The general atmosphere and the reaction of the white men is stated: “Conditions were set to deny women access to urban areas as they were seen as a threat” (Lee 7). This actually, negates the explanation how women were important to the resistance and the role. It shows weakness of women, instead of their strength in helping the resistance.

Overall, it is clear that the essay does not have many facts in support of causes, process of the resistance and the outcome. The actions of the native population are mentioned very briefly and do not serve as clear explanations. Nelson Mandela’s presence in the essay is not specific enough and no points about his actions and influence are given.

Works Cited

Buntman, Fran Lisa. Robben Island and prisoner resistance to apartheid. New York, United States: Campbridge University Press, 2003. Print.

Ellis, Stephen. Comrades Against Apartheid: The Anc & the South African Communist Party in Exile . Bloomington, United States: Indiana University Press, 1992. Print.

Lee, Rebekah. African women and Apartheid: migration and settlement in urban South Africa. New York, United States: Tauris Academic Studies, 1974. Print.

Shone, Rob. Nelson Mandela: The Life of an African Statesman . New York, United States: The Rosen Publishing Group, 2006. Print.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, May 7). Apartheid, Its Causes and the Process. https://ivypanda.com/essays/apartheid/

"Apartheid, Its Causes and the Process." IvyPanda , 7 May 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/apartheid/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'Apartheid, Its Causes and the Process'. 7 May.

IvyPanda . 2019. "Apartheid, Its Causes and the Process." May 7, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/apartheid/.

1. IvyPanda . "Apartheid, Its Causes and the Process." May 7, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/apartheid/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Apartheid, Its Causes and the Process." May 7, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/apartheid/.

- Apartheid in South Africa

- Impact of Apartheid on Education in South Africa

- China's Economic Competitiveness With the USA

- Israeli Apartheid Ideology Towards Palestinians

- The Necessity to Fight Apartheid in South Africa

- Apartheid in South: Historical Lenses

- Amazon: Transnational Corporation in Online Retail

- Post-Apartheid Restorative Justice Reconciliation

- Black Consciousness Movement vs. Apartheid in South Africa

- South African Apartheid: Historical Lenses and Perception

- Nelson Mandela’s Use of Power

- Relationship Between Modern Imperialism and Economic Globalization

- Darfur Genocide

- Use of Arts in the Second World War by Nazi

- Rwandan Students, Ethnic Tensions Lurk

Home — Essay Samples — History — Apartheid — The Way Apartheid Affected South Africa

The Way Apartheid Affected South Africa

- Categories: Apartheid Segregation

About this sample

Words: 1164 |

Published: Nov 8, 2019

Words: 1164 | Pages: 3 | 6 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: History Social Issues

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 1464 words

6 pages / 2505 words

1 pages / 572 words

2 pages / 1023 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Apartheid

If it accepted that one's vision of the future is shaped by an interpretation of the present and past, then any discussion of the conditions of post-apartheid South Africa requires a thorough understanding of apartheid. An [...]

In one way or another every one of us is a victim of the most untransformed policy in this university. To those of you who deny this, comparing to other universities, how diverse is our student body? What about staff diversity? [...]

Humanity has been fortunate enough to make advancements in medicine as time goes on. Medicine, and the lack of it, plays an important role in Our Town. Emily’s death is a key part of the conflict in the play. The third act’s [...]

“This was the Coming” is arguably one of the most impactful lines in Daniel Black’s The Coming, mostly because it captures everything that the novel is dedicated to, which is “the memory and celebration of African souls lost [...]

In “Master Harold”… and the Boys, black Africans are treated as though they are not as important as the white Africans. Fugard represents black Africans as people who have been disenfranchised, segregated, and less [...]

It seems contradictory that a person could simultaneously be treated as both completely worthless and completely inexpendable. Despite the paradoxical nature of this statement, it perfectly describes the plight of black women in [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Society and Politics

- Art and Culture

- Biographies

- Publications

Land, Labour and Apartheid

Land and labour are two very important elements of the economic development of a society, and the way they are used will influence how the society develops. In South African history there has always been the fight for ownership of land and the need for cheap labour. Government policies over the years have tried to solve this problem in different ways.

At the start of the twentieth century, in 1910, the whole of South Africa was united under one government. Until this time, the Cape and Natal had been colonies controlled by the British, and the Transvaal and Free State were areas under Boer control. The South Africa War was fought at the end of the 19th century, leaving all the land in the hands of the British. The rights of the black population were generally not taken into account, although they did still live scattered across South Africa. Some black tribes had been forced off their land over the years and had resettled.

After the Union of South Africa, 1910, land in South Africa was divided. In 1913 the government passed the Land Act. This Act decided how the land in South Africa was going to be divided between black and white people. At this time there was no apartheid policy in place, but the government did want to prevent black and white people from mixing together. The policy is known as the policy of segregation, and would later be replaced with the policy of apartheid in 1948.

The 1913 Land Act set aside 7.5% of the land in South Africa for black people. The Act also said that black people could not get more land outside of their tribal areas. The Act caused a problem for black people who worked on white land but had their own piece of ground. These people, known as share-croppers, had to decide between working for the white farm owners or moving to areas set aside for black people. The situation with the 1913 Land Act became only very slightly better in 1936 when the Native Trust and Land Act increased the amount of land to just over 10% of South Africa.

During the same period the government saw the need for cheap labour to work on the mines and on farms. The government needed to make sure that people did come to the towns, and for this reason they introduced taxes that needed to be paid. This meant that young men left their families for a while to come to the cities to earn some money. This money was then given over to the chief to pay taxes. This became known as the system of migrant labour - people moved across the country, often far from home, to work for a short while and then return to their families. There were few job opportunities in the black areas, so they had to go to the cities to get cash to pay the government taxes.

The system of migrant labour led to some problems developing in black society:

- young men sometimes could not marry until they had done a certain amount of labour for the chief

- families were disrupted

- farms were left in the hands of women and young children

- men in the cities became used to the western way of life, and did not want to settle on the farms again

- the tribal and traditional society was broken up

The government also introduced laws to protect white labour - reserving certain jobs for white people only, and other jobs were kept for black people only. The jobs that white people did were normally better paid, although there were also some poor whites.

During Apartheid

The situation with regard to labour and land remained more or less the same during the apartheid period. With regard to labour, the policy of protected labour remained in place, strengthened by the Bantu Education Policy. The system of migrant labour continued, although more black people started settling in white areas, leading to the establishment of townships. Many men continued to come to the city without their wives, which led to the deterioration of the family system and unfaithfulness in marriages. Workers in the mines had to stay on the mine premises where their wives could not stay. They stayed in rooms with many other men. Women increasingly came to the towns to get work as domestic workers, leaving their children behind to be looked after by other family members.

The land laws were made stricter in the apartheid period, although the amount of land allocated to the black people did increase slightly. Black people were not allowed to live in white areas, and could not own land in these areas. This meant that those staying in townships could not own their land. The apartheid government also removed black people from some areas and declared these areas white. The apartheid government had a policy called the homeland policy. According to this policy, black people would all become citizens of independent black homelands. The government said that black people should settle in their own homeland, own land there and have political freedom there. Many black people were born in these urban areas and had never been to the countryside that was suddenly declared their 'homeland' by the white government. These homelands were usually not on the most fertile soil or in the best area, making economic success impossible, especially with the overcrowding and poor facilities. It was planned that all black people would eventually live in the 'homelands', and some would commute to work in the white areas. Essentially the 'homelands' were desolate, depressed labour pools for white business to obtain cheap workers. The apartheid state invented the idea of separate homelands that emphasized division and difference between the different tribes in South Africa' Sotho, Zulu, Xhosa, Tswana, Pedi, etc. This was a 'divide and rule' strategy which made up myths about how the government thought black people were completely separate from each other. The reason for this was that it made apartheid seem more logical (no mixing between races) and also ensured that the different groups could not all join together against the government. The truth was somewhat different: e.g. some tribes had been intermarrying for years and separation caused great sadness and social turmoil (e.g. the Shangaan and Venda). Some homelands that were created were Transkei, Ciskei, Bophuthatswana and Lebowa to name a few.

Collections in the Archives

Know something about this topic.

Towards a people's history

Write briefly about the struggle against Apartheid in South Africa. .

Answer: separation of people as per their race is known as apartheid. this racial discrimination was followed in south africa. the african national congress fought against apartheid in south africa. black people faced political emancipation. black people were facing discrimination, poverty, and suffering. black people were facing deprivation, which meant they did not have rightful benefits. black people lived in most inhumane, and harshest society as they faced racial discrimination due to a system put in place by white-skinned people. thousands of black people in south africa made unimaginable sacrifices to get freedom from racial discrimination and to have equal rights. the prominent south african people who fought against apartheid were oliver tambo, walter sisulu, chief luthuli, yusuf dadoo, bram fischer, robert subukwe and indeed the great nelson mandela. many black people of south africa showed strength and resilience even though they were attacked and tortured. men of color who wanted to fulfill the basic obligations in their life were isolated and punished. men of color were torn apart from their families. many countries broke off the diplomatic relations with south africa due to policy of apartheid. nelson mandela and african national congress spent their lifetime fighting against apartheid. nelson mandela spent 30 years in prison fighting against apartheid. finally, the first elections democratic elections were held in 1994. the african national congress won 252 seats of the 400 seats and mandela became the first ever black president of south africa..

who led the struggle against apartheid? state any four reasons particles followed in the system of apartheid in south africa

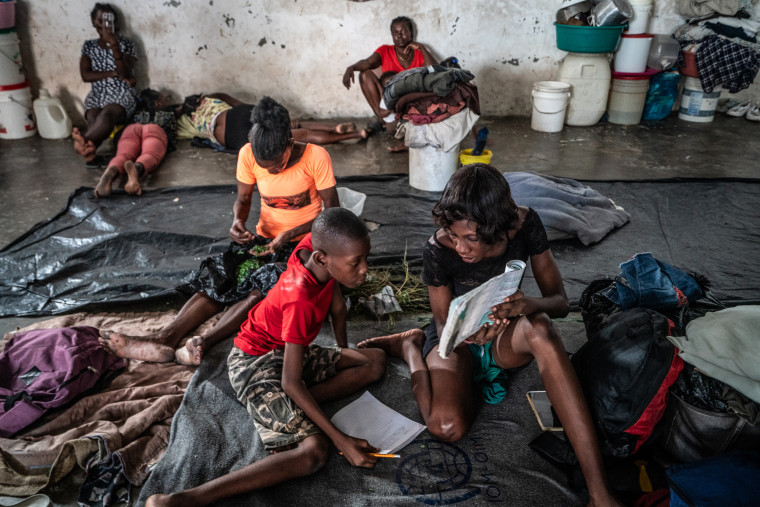

What to know about the crisis of violence, politics and hunger engulfing Haiti

A long-simmering crisis over Haiti’s ability to govern itself, particularly after a series of natural disasters and an increasingly dire humanitarian emergency, has come to a head in the Caribbean nation, as its de facto president remains stranded in Puerto Rico and its people starve and live in fear of rampant violence.

The chaos engulfing the country has been bubbling for more than a year, only for it to spill over on the global stage on Monday night, as Haiti’s unpopular prime minister, Ariel Henry, agreed to resign once a transitional government is brokered by other Caribbean nations and parties, including the U.S.

But the very idea of a transitional government brokered not by Haitians but by outsiders is one of the main reasons Haiti, a nation of 11 million, is on the brink, according to humanitarian workers and residents who have called for Haitian-led solutions.

“What we’re seeing in Haiti has been building since the 2010 earthquake,” said Greg Beckett, an associate professor of anthropology at Western University in Canada.

What is happening in Haiti and why?

In the power vacuum that followed the assassination of democratically elected President Jovenel Moïse in 2021, Henry, who was prime minister under Moïse, assumed power, with the support of several nations, including the U.S.

When Haiti failed to hold elections multiple times — Henry said it was due to logistical problems or violence — protests rang out against him. By the time Henry announced last year that elections would be postponed again, to 2025, armed groups that were already active in Port-au-Prince, the capital, dialed up the violence.

Even before Moïse’s assassination, these militias and armed groups existed alongside politicians who used them to do their bidding, including everything from intimidating the opposition to collecting votes . With the dwindling of the country’s elected officials, though, many of these rebel forces have engaged in excessively violent acts, and have taken control of at least 80% of the capital, according to a United Nations estimate.

Those groups, which include paramilitary and former police officers who pose as community leaders, have been responsible for the increase in killings, kidnappings and rapes since Moïse’s death, according to the Uppsala Conflict Data Program at Uppsala University in Sweden. According to a report from the U.N . released in January, more than 8,400 people were killed, injured or kidnapped in 2023, an increase of 122% increase from 2022.

“January and February have been the most violent months in the recent crisis, with thousands of people killed, or injured, or raped,” Beckett said.

Armed groups who had been calling for Henry’s resignation have already attacked airports, police stations, sea ports, the Central Bank and the country’s national soccer stadium. The situation reached critical mass earlier this month when the country’s two main prisons were raided , leading to the escape of about 4,000 prisoners. The beleaguered government called a 72-hour state of emergency, including a night-time curfew — but its authority had evaporated by then.

Aside from human-made catastrophes, Haiti still has not fully recovered from the devastating earthquake in 2010 that killed about 220,000 people and left 1.5 million homeless, many of them living in poorly built and exposed housing. More earthquakes, hurricanes and floods have followed, exacerbating efforts to rebuild infrastructure and a sense of national unity.

Since the earthquake, “there have been groups in Haiti trying to control that reconstruction process and the funding, the billions of dollars coming into the country to rebuild it,” said Beckett, who specializes in the Caribbean, particularly Haiti.

Beckett said that control initially came from politicians and subsequently from armed groups supported by those politicians. Political “parties that controlled the government used the government for corruption to steal that money. We’re seeing the fallout from that.”

Many armed groups have formed in recent years claiming to be community groups carrying out essential work in underprivileged neighborhoods, but they have instead been accused of violence, even murder . One of the two main groups, G-9, is led by a former elite police officer, Jimmy Chérizier — also known as “Barbecue” — who has become the public face of the unrest and claimed credit for various attacks on public institutions. He has openly called for Henry to step down and called his campaign an “armed revolution.”

But caught in the crossfire are the residents of Haiti. In just one week, 15,000 people have been displaced from Port-au-Prince, according to a U.N. estimate. But people have been trying to flee the capital for well over a year, with one woman telling NBC News that she is currently hiding in a church with her three children and another family with eight children. The U.N. said about 160,000 people have left Port-au-Prince because of the swell of violence in the last several months.

Deep poverty and famine are also a serious danger. Gangs have cut off access to the country’s largest port, Autorité Portuaire Nationale, and food could soon become scarce.

Haiti's uncertain future

A new transitional government may dismay the Haitians and their supporters who call for Haitian-led solutions to the crisis.

But the creation of such a government would come after years of democratic disruption and the crumbling of Haiti’s political leadership. The country hasn’t held an election in eight years.

Haitian advocates and scholars like Jemima Pierre, a professor at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, say foreign intervention, including from the U.S., is partially to blame for Haiti’s turmoil. The U.S. has routinely sent thousands of troops to Haiti , intervened in its government and supported unpopular leaders like Henry.

“What you have over the last 20 years is the consistent dismantling of the Haitian state,” Pierre said. “What intervention means for Haiti, what it has always meant, is death and destruction.”

In fact, the country’s situation was so dire that Henry was forced to travel abroad in the hope of securing a U.N. peacekeeping deal. He went to Kenya, which agreed to send 1,000 troops to coordinate an East African and U.N.-backed alliance to help restore order in Haiti, but the plan is now on hold . Kenya agreed last October to send a U.N.-sanctioned security force to Haiti, but Kenya’s courts decided it was unconstitutional. The result has been Haiti fending for itself.

“A force like Kenya, they don’t speak Kreyòl, they don’t speak French,” Pierre said. “The Kenyan police are known for human rights abuses . So what does it tell us as Haitians that the only thing that you see that we deserve are not schools, not reparations for the cholera the U.N. brought , but more military with the mandate to use all kinds of force on our population? That is unacceptable.”

Henry was forced to announce his planned resignation from Puerto Rico, as threats of violence — and armed groups taking over the airports — have prevented him from returning to his country.

Now that Henry is to stand down, it is far from clear what the armed groups will do or demand next, aside from the right to govern.

“It’s the Haitian people who know what they’re going through. It’s the Haitian people who are going to take destiny into their own hands. Haitian people will choose who will govern them,” Chérizier said recently, according to The Associated Press .

Haitians and their supporters have put forth their own solutions over the years, holding that foreign intervention routinely ignores the voices and desires of Haitians.

In 2021, both Haitian and non-Haitian church leaders, women’s rights groups, lawyers, humanitarian workers, the Voodoo Sector and more created the Commission to Search for a Haitian Solution to the Crisis . The commission has proposed the “ Montana Accord ,” outlining a two-year interim government with oversight committees tasked with restoring order, eradicating corruption and establishing fair elections.

For more from NBC BLK, sign up for our weekly newsletter .

CORRECTION (March 15, 2024, 9:58 a.m. ET): An earlier version of this article misstated which university Jemima Pierre is affiliated with. She is a professor at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, not the University of California, Los Angeles, (or Columbia University, as an earlier correction misstated).

Patrick Smith is a London-based editor and reporter for NBC News Digital.

Char Adams is a reporter for NBC BLK who writes about race.

- Share full article

Opinion Guest Essay

The Great Rupture in American Jewish Life

Credit... Daniel Benneworth-Gray

Supported by

By Peter Beinart

Mr. Beinart is the editor at large of Jewish Currents and a journalist and writer who has written extensively on the Middle East, Jewish life and American foreign policy.

- March 22, 2024

F or the last decade or so, an ideological tremor has been unsettling American Jewish life. Since Oct. 7, it has become an earthquake. It concerns the relationship between liberalism and Zionism, two creeds that for more than half a century have defined American Jewish identity. In the years to come, American Jews will face growing pressure to choose between them.

They will face that pressure because Israel’s war in Gaza has supercharged a transformation on the American left. Solidarity with Palestinians is becoming as essential to leftist politics as support for abortion rights or opposition to fossil fuels. And as happened during the Vietnam War and the struggle against South African apartheid, leftist fervor is reshaping the liberal mainstream. In December, the United Automobile Workers demanded a cease-fire and formed a divestment working group to consider the union’s “economic ties to the conflict.” In January, the National L.G.B.T.Q. Task Force called for a cease-fire as well. In February, the leadership of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the nation’s oldest Black Protestant denomination, called on the United States to halt aid to the Jewish state. Across blue America, many liberals who once supported Israel or avoided the subject are making the Palestinian cause their own.

This transformation remains in its early stages. In many prominent liberal institutions — most significantly, the Democratic Party — supporters of Israel remain not only welcome but also dominant. But the leaders of those institutions no longer represent much of their base. The Democratic majority leader, Senator Chuck Schumer, acknowledged this divide in a speech on Israel on the Senate floor last week. He reiterated his longstanding commitment to the Jewish state, though not its prime minister. But he also conceded, in the speech’s most remarkable line, that he “can understand the idealism that inspires so many young people in particular to support a one-state solution” — a solution that does not involve a Jewish state. Those are the words of a politician who understands that his party is undergoing profound change.

The American Jews most committed to Zionism, the ones who run establishment institutions, understand that liberal America is becoming less ideologically hospitable. And they are responding by forging common cause with the American right. It’s no surprise that the Anti-Defamation League, which only a few years ago harshly criticized Donald Trump’s immigration policies, recently honored his son-in-law and former senior adviser, Jared Kushner.

Mr. Trump himself recognizes the emerging political split. “Any Jewish person that votes for Democrats hates their religion,” he said in an interview published on Monday. “They hate everything about Israel, and they should be ashamed of themselves because Israel will be destroyed.” It’s typical Trumpian indecency and hyperbole, but it’s rooted in a political reality. For American Jews who want to preserve their country’s unconditional support for Israel for another generation, there is only one reliable political partner: a Republican Party that views standing for Palestinian rights as part of the “woke” agenda.

The American Jews who are making a different choice — jettisoning Zionism because they can’t reconcile it with the liberal principle of equality under the law — garner less attention because they remain further from power. But their numbers are larger than many recognize, especially among millennials and Gen Z. And they face their own dilemmas. They are joining a Palestine solidarity movement that is growing larger, but also more radical, in response to Israel’s destruction of Gaza. That growing radicalism has produced a paradox: A movement that welcomes more and more American Jews finds it harder to explain where Israeli Jews fit into its vision of Palestinian liberation.

The emerging rupture between American liberalism and American Zionism constitutes the greatest transformation in American Jewish politics in half a century. It will redefine American Jewish life for decades to come.

“A merican Jews,” writes Marc Dollinger in his book “Quest for Inclusion: Jews and Liberalism in Modern America,” have long depicted themselves as “guardians of liberal America.” Since they came to the United States in large numbers around the turn of the 20th century, Jews have been wildly overrepresented in movements for civil, women’s, labor and gay rights. Since the 1930s, despite their rising prosperity, they have voted overwhelmingly for Democrats. For generations of American Jews, the icons of American liberalism — Eleanor Roosevelt, Robert Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr., Gloria Steinem — have been secular saints.

The American Jewish love affair with Zionism dates from the early 20th century as well. But it came to dominate communal life only after Israel’s dramatic victory in the 1967 war exhilarated American Jews eager for an antidote to Jewish powerlessness during the Holocaust. The American Israel Public Affairs Committee, which was nearly bankrupt on the eve of the 1967 war, had become American Jewry’s most powerful institution by the 1980s. American Jews, wrote Albert Vorspan, a leader of Reform Judaism, in 1988, “have made of Israel an icon — a surrogate faith, surrogate synagogue, surrogate God.”

Given the depth of these twin commitments, it’s no surprise that American Jews have long sought to fuse them by describing Zionism as a liberal cause. It has always been a strange pairing. American liberals generally consider themselves advocates of equal citizenship irrespective of ethnicity, religion and race. Zionism — or at the least the version that has guided Israel since its founding — requires Jewish dominance. From 1948 to 1966, Israel held most of its Palestinian citizens under military law; since 1967 it has ruled millions of Palestinians who hold no citizenship at all. Even so, American Jews could until recently assert their Zionism without having their liberal credentials challenged.

The primary reason was the absence from American public discourse of Palestinians, the people whose testimony would cast those credentials into greatest doubt. In 1984, the Palestinian American literary critic Edward Said argued that in the West, Palestinians lack “permission to narrate” their own experience. For decades after he wrote those words, they remained true. A study by the University of Arizona’s Maha Nassar found that of the opinion articles about Palestinians published in The New York Times and The Washington Post between 2000 and 2009, Palestinians themselves wrote roughly 1 percent.

But in recent years, Palestinian voices, while still embattled and even censored , have begun to carry. Palestinians have turned to social media to combat their exclusion from the press. In an era of youth-led activism, they have joined intersectional movements forged by parallel experiences of discrimination and injustice. Meanwhile, Israel — under the leadership of Benjamin Netanyahu for most of the past two decades — has lurched to the right, producing politicians so openly racist that their behavior cannot be defended in liberal terms.

Many Palestine solidarity activists identify as leftists, not liberals. But like the activists of the Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter movements, they have helped change liberal opinion with their radical critiques. In 2002, according to Gallup , Democrats sympathized with Israel over the Palestinians by a margin of 34 points. By early 2023, they favored the Palestinians by 11 points. And because opinion about Israel cleaves along generational lines, that pro-Palestinian skew is much greater among the young. According to a Quinnipiac University poll in November, Democrats under the age of 35 sympathize more with Palestinians than with Israelis by 58 points.

Given this generational gulf, universities offer a preview of the way many liberals — or “progressives,” a term that straddles liberalism and leftism and enjoys more currency among young Americans — may view Zionism in the years to come. Supporting Palestine has become a core feature of progressive politics on many campuses. At Columbia, for example, 94 campus organizations — including the Vietnamese Students Association, the Reproductive Justice Collective and Poetry Slam, Columbia’s “only recreational spoken word club” — announced in November that they “see Palestine as the vanguard for our collective liberation.” As a result, Zionist Jewish students find themselves at odds with most of their politically active peers.

Accompanying this shift, on campus and beyond, has been a rise in Israel-related antisemitism. It follows a pattern in American history. From the hostility toward German Americans during World War I to violence against American Muslims after Sept. 11 and assaults on Asian Americans during the Covid pandemic, Americans have a long and ugly tradition of expressing their hostility toward foreign governments or movements by targeting compatriots who share a religion, ethnicity or nationality with those overseas adversaries. Today, tragically, some Americans who loathe Israel are taking it out on American Jews. (Palestinian Americans, who have endured multiple violent hate crimes since Oct. 7, are experiencing their own version of this phenomenon.) The spike in antisemitism since Oct. 7 follows a pattern. Five years ago, the political scientist Ayal Feinberg, using data from 2001 and 2014, found that reported antisemitic incidents in the United States spike when the Israeli military conducts a substantial military operation.

Attributing the growing discomfort of pro-Israel Jewish students entirely to antisemitism, however, misses something fundamental. Unlike establishment Jewish organizations, Jewish students often distinguish between bigotry and ideological antagonism. In a 2022 study , the political scientist Eitan Hersh found that more than 50 percent of Jewish college students felt “they pay a social cost for supporting the existence of Israel as a Jewish state.” And yet, in general, Dr. Hersh reported, “the students do not fear antisemitism.”

Surveys since Oct. 7 find something similar. Asked in November in a Hillel International poll to describe the climate on campus since the start of the war, 20 percent of Jewish students answered “unsafe” and 23 percent answered “scary.” By contrast, 45 percent answered “uncomfortable” and 53 percent answered “tense.” A survey that same month by the Jewish Electorate Institute found that only 37 percent of American Jewish voters ages 18 to 35 consider campus antisemitism a “very serious problem,” compared with nearly 80 percent of American Jewish voters over the age of 35.

While some young pro-Israel American Jews experience antisemitism, they more frequently report ideological exclusion. As Zionism becomes associated with the political right, their experiences on progressive campuses are coming to resemble the experiences of young Republicans. The difference is that unlike young Republicans, most young American Zionists were raised to believe that theirs was a liberal creed. When their parents attended college, that assertion was rarely challenged. On the same campuses where their parents felt at home, Jewish students who view Zionism as central to their identity now often feel like outsiders.

In 1979, Mr. Said observed that in the West, “to be a Palestinian is in political terms to be an outlaw.” In much of America — including Washington — that remains true. But within progressive institutions one can glimpse the beginning of a historic inversion. Often, it’s now the Zionists who feel like outlaws.

G iven the organized American Jewish community’s professed devotion to liberal principles, which include free speech, one might imagine that Jewish institutions would greet this ideological shift by urging pro-Israel students to tolerate and even learn from their pro-Palestinian peers. Such a stance would flow naturally from the statements establishment Jewish groups have made in the past. A few years ago, the Anti-Defamation League declared that “our country’s universities serve as laboratories for the exchange of differing viewpoints and beliefs. Offensive, hateful speech is protected by the Constitution’s First Amendment.”

But as pro-Palestinian sentiment has grown in progressive America, pro-Israel Jewish leaders have apparently made an exception for anti-Zionism. While still claiming to support free speech on campus, the ADL last October asked college presidents to investigate local chapters of Students for Justice in Palestine to determine whether they violated university regulations or state or federal laws, a demand that the American Civil Liberties Union warned could “chill speech” and “betray the spirit of free inquiry.” After the University of Pennsylvania hosted a Palestinian literature festival last fall, Marc Rowan, chair of the United Jewish Appeal-Federation of New York and chair of the board of advisers of Penn’s Wharton business school, condemned the university’s president for giving the festival Penn’s “imprimatur.” In December, he encouraged trustees to alter university policies in ways that Penn’s branch of the American Association of University Professors warn ed could “silence and punish speech with which trustees disagree.”

In this effort to limit pro-Palestinian speech, establishment Jewish leaders are finding their strongest allies on the authoritarian right. Pro-Trump Republicans have their own censorship agenda: They want to stop schools and universities from emphasizing America’s history of racial and other oppression. Calling that pedagogy antisemitic makes it easier to ban or defund. At a much discussed congressional hearing in December featuring the presidents of Harvard, Penn and M.I.T., the Republican representative Virginia Foxx noted that Harvard teaches courses like “Race and Racism in the Making of the United States as a Global Power” and hosts seminars such as “Scientific Racism and Anti-Racism: History and Recent Perspectives” before declaring that “Harvard also, not coincidentally but causally, was ground zero for antisemitism following Oct. 7.”

Ms. Foxx’s view is typical. While some Democrats also equate anti-Zionism and antisemitism, the politicians and business leaders most eager to suppress pro-Palestinian speech are conservatives who link such speech to the diversity, equity and inclusion agenda they despise. Elise Stefanik, a Trump acolyte who has accused Harvard of “caving to the woke left,” became the star of that congressional hearing by demanding that Harvard’s president , Claudine Gay, punish students who chant slogans like “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free.” (Ms. Gay was subsequently forced to resign following charges of plagiarism.) Elon Musk, who in November said that the phrase “from the river to the sea” was banned from his social media platform X (formerly Twitter), the following month declared , “D.E.I. must die.” The first governor to ban Students for Justice in Palestine chapters at his state’s public universities was Florida’s Ron DeSantis, who has also signed legislation that limits what those universities can teach about race and gender.

This alignment between the American Jewish organizational establishment and the Trumpist right is not limited to universities. If the ADL has aligned with Republicans who want to silence “woke” activists on campus, AIPAC has joined forces with Republicans who want to disenfranchise “woke” voters. In the 2022 midterm elections, AIPAC endorsed at least 109 Republicans who opposed certifying the 2020 election. For an organization single-mindedly focused on sustaining unconditional U.S. support for Israel, that constituted a rational decision. Since Republican members of Congress don’t have to mollify pro-Palestinian voters, they’re AIPAC’s most dependable allies. And if many of those Republicans used specious claims of Black voter fraud to oppose the democratic transfer of power in 2020 — and may do so again — that’s a price AIPAC seems to be prepared to pay.

F or the many American Jews who still consider themselves both progressives and Zionists, this growing alliance between leading Zionist institutions and a Trumpist Republican Party is uncomfortable. But in the short term, they have an answer: politicians like President Biden, whose views about both Israel and American democracy roughly reflect their own. In his speech last week, Mr. Schumer called these liberal Zionists American Jewry’s “silent majority.”

For the moment he may be right. In the years to come, however, as generational currents pull the Democratic Party in a more pro-Palestinian direction and push America’s pro-Israel establishment to the right, liberal Zionists will likely find it harder to reconcile their two faiths. Young American Jews offer a glimpse into that future, in which a sizable wing of American Jewry decides that to hold fast to its progressive principles it must jettison Zionism and embrace equal citizenship in Israel and Palestine, as well as in the United States.

For an American Jewish establishment that equates anti-Zionism with antisemitism, these anti-Zionist Jews are inconvenient. Sometimes, pro-Israel Jewish organizations pretend they don’t exist. In November, after Columbia suspended two anti-Zionist campus groups, the ADL thanked university leaders for acting “to protect Jewish students” — even though one of the suspended groups was Jewish Voice for Peace. At other times, pro-Israel leaders describe anti-Zionist Jews as a negligible fringe. If American Jews are divided over the war in Gaza, Andrés Spokoiny, the president and chief executive of the Jewish Funders Network, an organization for Jewish philanthropists, declared in December, “the split is 98 percent/2 percent.”

Among older American Jews, this assertion of a Zionist consensus contains some truth. But among younger American Jews, it’s false. In 2021, even before Israel’s current far-right government took power, the Jewish Electorate Institute found that 38 percent of American Jewish voters under the age of 40 viewed Israel as an apartheid state, compared with 47 percent who said it’s not. In November, it revealed that 49 percent of American Jewish voters ages 18 to 35 opposed Mr. Biden’s request for additional military aid to Israel. On many campuses, Jewish students are at the forefront of protests for a cease-fire and divestment from Israel. They don’t speak for all — and maybe not even most — of their Jewish peers. But they represent far more than 2 percent.

These progressive Jews are, as the U.S. editor of The London Review of Books, Adam Shatz, noted to me, a double minority. Their anti-Zionism makes them a minority among American Jews, while their Jewishness makes them a minority in the Palestine solidarity movement. Fifteen years ago, when the liberal Zionist group J Street was intent on being the “ blocking back ” for President Barack Obama’s push for a two-state solution, some liberal Jews imagined themselves leading the push to end Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Today, the prospect of partition has diminished, and Palestinians increasingly set the terms of activist criticism of Israel. That discourse, which is peppered with terms like “apartheid” and “decolonization," is generally hostile to a Jewish state within any borders.

There’s nothing antisemitic about envisioning a future in which Palestinians and Jews coexist on the basis of legal equality rather than Jewish supremacy. But in pro-Palestine activist circles in the United States, coexistence has receded as a theme. In 1999, Mr. Said argued for “a binational Israeli-Palestinian state” that offered “self-determination for both peoples.” In his 2007 book, “One Country,” Ali Abunimah, a co-founder of The Electronic Intifada, an influential source of pro-Palestine news and opinion, imagined one state whose name reflected the identities of both major communities that inhabit it. The terms “‘Israel’ and ‘Palestine’ are dear to those who use them and they should not be abandoned,” he argued. “The country could be called Yisrael-Falastin in Hebrew and Filastin-Isra’il in Arabic.”

In recent years, however, as Israel has moved to the right, pro-Palestinian discourse in the United States has hardened. The phrase “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free,” which dates from the 1960s but has gained new prominence since Oct. 7, does not acknowledge Palestine and Israel’s binational character. To many American Jews, in fact, the phrase suggests a Palestine free of Jews. It sounds expulsionist, if not genocidal. It’s an ironic charge, given that it is Israel that today controls the land between the river and the sea, whose leaders openly advocate the mass exodus of Palestinians and that the International Court of Justice says could plausibly be committing genocide in Gaza.

Palestinian scholars like Maha Nassar and Ahmad Khalidi argue that “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free” does not imply the subjugation of Jews. It instead reflects the longstanding Palestinian belief that Palestine should have become an independent country when released from European colonial control, a vision that does not preclude Jews from living freely alongside their Muslim and Christian neighbors. The Jewish groups closest to the Palestine solidarity movement agree: Jewish Voice for Peace’s Los Angeles chapter has argued that the slogan is no more anti-Jewish than the phrase “Black lives matter” is anti-white. And if the Palestine solidarity movement in the United States calls for the genocide of Jews, it’s hard to explain why so many Jews have joined its ranks. Rabbi Alissa Wise, an organizer of Rabbis for Cease-Fire, estimates that other than Palestinians, no other group has been as prominent in the protests against the war as Jews.

Still, imagining a “free Palestine” from the river to the sea requires imagining that Israeli Jews will become Palestinians, which erases their collective identity. That’s a departure from the more inclusive vision that Mr. Said and Mr. Abunimah outlined years ago. It’s harder for Palestinian activists to offer that more inclusive vision when they are watching Israel bomb and starve Gaza. But the rise of Hamas makes it even more essential.

Jews who identify with the Palestinian struggle may find it difficult to offer this critique. Many have defected from the Zionist milieu in which they were raised. Having made that painful transition, which can rupture relations with friends and family, they may be disinclined to question their new ideological home. It’s frightening to risk alienating one community when you’ve already alienated another. Questioning the Palestine solidarity movement also violates the notion, prevalent in some quarters of the American left, that members of an oppressor group should not second-guess representatives of the oppressed.

But these identity hierarchies suppress critical thought. Palestinians aren’t a monolith, and progressive Jews aren’t merely allies. They are members of a small and long-persecuted people who have not only the right but also the obligation to care about Jews in Israel, and to push the Palestine solidarity movement to more explicitly include them in its vision of liberation, in the spirit of the Freedom Charter adopted during apartheid by the African National Congress and its allies, which declared in its second sentence that “South Africa belongs to all who live in it, Black and white.”

For many American Jews, it is painful to watch their children’s or grandchildren’s generation question Zionism. It is infuriating to watch students at liberal institutions with which they once felt aligned treat Zionism as a racist creed. It is tempting to attribute all this to antisemitism, even if that requires defining many young American Jews as antisemites themselves.

But the American Jews who insist that Zionism and liberalism remain compatible should ask themselves why Israel now attracts the fervent support of Representative Stefanik but repels the African Methodist Episcopal Church and the United Automobile Workers. Why it enjoys the admiration of Elon Musk and Viktor Orban but is labeled a perpetrator of apartheid by Human Rights Watch and likened to the Jim Crow South by Ta-Nehisi Coates. Why it is more likely to retain unconditional American support if Mr. Trump succeeds in turning the United States into a white Christian supremacist state than if he fails.

For many decades, American Jews have built our political identity on a contradiction: Pursue equal citizenship here; defend group supremacy there. Now here and there are converging. In the years to come, we will have to choose.

Peter Beinart ( @PeterBeinart ) is a professor of journalism and political science at the Newmark School of Journalism at the City University of New York. He is also the editor at large of Jewish Currents and writes The Beinart Notebook , a weekly newsletter.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here’s our email: [email protected] .

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Instagram , TikTok , WhatsApp , X and Threads .

Advertisement

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Apartheid (Afrikaans: "apartness") is the name of the policy that governed relations between the white minority and the nonwhite majority of South Africa during the 20th century. Although racial segregation had long been in practice there, the apartheid name was first used about 1948 to describe the racial segregation policies embraced by the white minority government.

Introduction. South Africa is one of the countries with rich and fascinating history in the world. It is regarded as the most developed state in Africa and among the last to have an elected black president towards the end of the 20 th century. Besides its rich history, the South African state has abundant natural resources, fertile farms and a wide range of minerals including gold.

Apartheid called for the separate development of the different racial groups in South Africa. On paper it appeared to call for equal development and freedom of cultural expression, but the way it was implemented made this impossible. Apartheid made laws forced the different racial groups to live separately and develop separately, and grossly ...

Apartheid, the legal and cultural segregation of the non-white citizens of South Africa, ended in 1994 thanks to activist Nelson Mandela and F.W. de Klerk.

Apartheid existed as the official state policy in South Africa from 1948 to 1994. The term "apartheid" is an Afrikaans word which literally means "apartness," and it was used to segregate South ...

Apartheid (/ ə ˈ p ɑːr t (h) aɪ t / ə-PART-(h)yte, especially South African English: / ə ˈ p ɑːr t (h) eɪ t / ə-PART-(h)ayt, Afrikaans: [aˈpartɦɛit] ⓘ; transl. "separateness", lit. 'aparthood') was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the ...

The roots of apartheid can be found in the history of colonialism in South Africa and the complicated relationship among the Europeans that took up residence, but the elaborate system of racial laws was not formalized into a political vision until the late 1940s. That system, called apartheid ("apartness"), remained in place until the early ...

Apartheid resulted from white people's frustrations and their dissatisfactions by the then overwhelming presence of Black people in cities. The large numbers of Black people in cities threatened white people's power. To whites, it seemed like Black people would be difficult to control in cities than in Homelands.

EXPLAINING APARTHEID: DIFFERENT APPROACHES. How did apartheid come about? The Afrikaner Nationalist Approach. The Liberal Approach. The Radical Approach. The Social History Approach. THE GLITTER OF GOLD: LAYING THE FOUNDATIONS OF APARTHEID.

Apartheid and the myth of 'race' Africa's Apartheid struggle and were implemented under the Separate Amenities Act. Image source. The construct can be seen as a highly notorious term, despite it having no physical basis. This term was, however, heavily used in South Africa's pre- democracy phase, Apartheid.

Activists from every corner of the Earth, inspired by the actions of black South Africans, demanded an end to an unjust system known as apartheid. Apartheid is an Afrikaans 1 word meaning "apartness." It was a policy of legal discrimination and segregation directed at the black majority in South Africa.

The apartheid policies which the National Party government implemented after 1948 had serious implications for South African society. These policies institutionalized and entrenched racial discrimination in an unequal society where the white minority was privileged and the black majority was severely disadvantaged.

In Verwoerd's vision, South Africa's population contained four distinct racial groups—white, Black, Coloured, and Asian—each with an inherent culture. Because whites were the "civilized" group, they were entitled to control the state. The all-white Parliament passed many laws to legalize and institutionalize the apartheid system.

untitled. Chapter. 4 Resistance to apartheid. Critical Outcomes. • Work effectively with others as members of a team, organization and community. • Communicate effectively using visual, symbolic and/or language skills in various modes. • Demonstrate an understanding of the world as a set of related systems, by recognizing that problem ...

Tsotsi represents South African apartheid (a system of legally enforced segregation and discrimination) as a racist structure that destroys Black South Africans' lives—even when they aren't experiencing direct, interpersonal racism. Many of the Black characters' lives are destroyed by racist apartheid laws despite having little direct contact with racist white people.

Apartheid in South Africa Essay. Apartheid, the Afrikaans word for "apartness" was the system used in South Africa from the years 1948 to 1994. During these years the nearly 31.5 million blacks in South Africa were treated cruelly and without respect. They were given no representation in parliament even though they made up most of the country.