Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Midwifery continuity of care: A scoping review of where, how, by whom and for whom?

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Maternal, Child, and Adolescent Health Program, Burnet Institute, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, Mater Research, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Maternal, Child, and Adolescent Health Program, Burnet Institute, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, Melbourne Medical School, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Maternal, Newborn, Child, and Adolescent Health, World Health Organisation, Geneva, Switzerland

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Roles Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Women and Children’s Health, Kings College London, London, United Kingdom

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Maternal, Child, and Adolescent Health Program, Burnet Institute, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

- Billie F. Bradford,

- Alyce N. Wilson,

- Anayda Portela,

- Fran McConville,

- Cristina Fernandez Turienzo,

- Caroline S. E. Homer

- Published: October 5, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000935

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

Systems of care that provide midwifery care and services through a continuity of care model have positive health outcomes for women and newborns. We conducted a scoping review to understand the global implementation of these models, asking the questions: where, how, by whom and for whom are midwifery continuity of care models implemented? Using a scoping review framework, we searched electronic and grey literature databases for reports in any language between January 2012 and January 2022, which described current and recent trials, implementation or scaling-up of midwifery continuity of care studies or initiatives in high-, middle- and low-income countries. After screening, 175 reports were included, the majority (157, 90%) from high-income countries (HICs) and fewer (18, 10%) from low- to middle-income countries (LMICs). There were 163 unique studies including eight (4.9%) randomised or quasi-randomised trials, 58 (38.5%) qualitative, 53 (32.7%) quantitative (cohort, cross sectional, descriptive, observational), 31 (19.0%) survey studies, and three (1.9%) health economics analyses. There were 10 practice-based accounts that did not include research. Midwives led almost all continuity of care models. In HICs, the most dominant model was where small groups of midwives provided care for designated women, across the antenatal, childbirth and postnatal care continuum. This was mostly known as caseload midwifery or midwifery group practice. There was more diversity of models in low- to middle-income countries. Of the 175 initiatives described, 31 (18%) were implemented for women, newborns and families from priority or vulnerable communities. With the exception of New Zealand, no countries have managed to scale-up continuity of midwifery care at a national level. Further implementation studies are needed to support countries planning to transition to midwifery continuity of care models in all countries to determine optimal model types and strategies to achieve sustainable scale-up at a national level.

Citation: Bradford BF, Wilson AN, Portela A, McConville F, Fernandez Turienzo C, Homer CSE (2022) Midwifery continuity of care: A scoping review of where, how, by whom and for whom? PLOS Glob Public Health 2(10): e0000935. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000935

Editor: Ahmed Waqas, University of Liverpool, UNITED KINGDOM

Received: June 3, 2022; Accepted: September 5, 2022; Published: October 5, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Bradford et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All data are in the Supporting information files.

Funding: This review was commissioned by the World Health Organization Department of Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health and Ageing and funded through a grant received from Merck Sharp and Dohme Corp (MSD). CFT is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration (ARC) South London, a NIHR Global Health Research Group (NIHR133232) and a NIHR Development and Skills Award (NIHR301603). CSEH is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Fellowship (APP1137745). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Continuity of care is a concept rooted in primary care involving the care of individuals (rather than populations) over time by the same care provider. It encompasses relational continuity, informational continuity and management continuity [ 1 ]. In the primary care setting, continuity of care has been shown to reduce mortality and hospitalisations, and increase patient satisfaction [ 2 ]. Continuity of care also has an important place in chronic care settings, such as palliative care [ 3 ].

In the maternal and newborn care setting, midwife-led continuity of care refers to a model whereby care is provided by the same midwife, or small team of midwives, during pregnancy, labour and birth, and the postnatal periods with referral to specialist care as needed [ 4 ]. Midwife-led also refers to a model of care which is provided there is a distinct occupational group of midwives [ 5 ] and the person is fully qualified, regulated and deployed only as a midwife. This contrasts to systems in many countries (most countries in Africa for and South East Asia for example) where nurse-midwives are rotated to either nursing or midwifery duties. Midwife-led continuity models in a small number of HICs have been associated with lower rates of preterm birth (24% reduction), and lower fetal loss before and after 24 weeks and neonatal deaths (16%) less likely to lose their babies overall (combined reduction in fetal loss and neonatal death) for women at low and mixed risk of complications compared to other models of care. In addition, women are less likely to experience interventions and more likely to report positive experiences of care [ 4 ]. A Cochrane review of reviews of interventions during pregnancy to prevent preterm birth also found that these models had clear benefit in reducing preterm birth and perinatal death [ 6 ]. Women prefer the personalised experience provided by such models, leading to trust between midwife and woman and empowerment of both women and midwives [ 7 ].

Models of care that provide continuity across the childbearing continuum are complex interventions, and the pathway of influence that produces these positive outcomes is unclear. A number of plausible hypotheses require further investigation. For example, it could be that midwives provide a mechanism that enables effective and equitable care to be provided by better coordination, navigation and referral; and/or that relational continuity and advocacy engenders trust and confidence between women and midwives, resulting in women feeling safer, less stressed and more respected [ 4 ]. Access to organisational infrastructure, innovative partnerships, and robust community networks has been found crucial to overcome barriers, address women’s, newborns’ and parents’ needs and ensure quality of care [ 8 ].

Inequity is a key driver of adverse perinatal outcome, both between and within countries. Some observational studies of midwife-led continuity of care models in socially and economically disadvantaged populations in high-income countries (HIC) have reported significant reductions in pre-term birth and caesarean sections in diverse cohorts of women in the United Kingdom [ 9 – 12 ]. In Australia, a study of maternity care during significant floods in Queensland showed that midwife-led continuity of care mitigated the social and emotional impacts of the floods [ 13 ]. Another Australian study showed reduced preterm births amongst Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who received midwife-led continuity of care [ 14 ]. These studies suggest that women who typically experience a greater burden of adverse perinatal outcome, may derive greater benefit from continuity of care. However, understanding how continuity per se may mitigate inequities in maternal and newborn health remains a research priority.

Despite evidence supporting midwife-led continuity of care and guidelines from the World Health Organization which recommend midwife-led continuity-of-care models for pregnant women in settings with well-functioning midwifery programmes [ 15 – 17 ] only a small proportion of women internationally have access to such care. The current evidence suggests that access to midwife-led continuity of care models is largely confined to a small number of HICs notably Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United Kingdom [ 17 ] where a distinct occupational group of midwives has been a central part of the health systems for decades. Barriers to implementation of midwifery-led continuity of care exist across all country income levels and include a lack of local health system financing, shortage of personnel including administrative and other support staff [ 4 ]. It is not clear to what extent midwife-led continuity of care has been implemented in low- to middle-income countries (LMIC). Many LMICs have a model of predominantly nurse-midwives who are deployed to both nursing and midwifery duties, often preventing midwife-led continuity of care models. Advancing understanding around which countries have implemented continuity of care models for maternal and newborn health, how, for whom, and in what context, is crucial for successful implementation, scale-up and sustainability.

The overall aim of this review was to understand the global implementation of midwifery continuity of care, asking the questions: Where, how, by whom and for whom are midwifery continuity of care initiatives implemented?

Materials and methods

A scoping review was undertaken guided by the approach described by Arksey and O’Malley [ 18 ] and further defined by Levac and colleagues [ 19 ]. The following five steps were followed: i) identifying the research question; ii) identifying the relevant literature; iii) study selection, iv) charting the data; and v) collating, summarising and reporting the results.

We used the broad definition of midwifery from The Lancet Series on Midwifery as our starting point, that is, “skilled, knowledgeable, and compassionate care for childbearing women, newborn infants and families across the continuum from pre-pregnancy, pregnancy, birth, postpartum and the early weeks of life [ 20 ]. Midwifery continuity of care was defined as care delivered by the same known care provider or care provider team across two or more parts in the care continuum–antenatal, intrapartum, postnatal and neonatal periods. In some settings, continuity of care may be provided by cadre other than midwives, for example, nurses or physicians. Thus, eligible papers could include care providers that were midwives and non-midwives, such as, nurses, community health workers and physicians. We excluded reports on care primarily by traditional birth attendants (TBA).

Identifying the relevant literature—Search strategy and selection criteria

In order to develop the search strategy, a preliminary search of PubMed and Google scholar using the terms ‘midwifery or midwife-led continuity of care’ were used to locate key systematic and scoping reviews on the topic and identify relevant search terms for the systematic search strategy (see S1 Text for the search strategy). We then searched the following electronic databases: MEDLINE, CENTRAL, CINAHL, PsychINFO and Web of Science. A subject librarian reviewed search terms, keywords and strategies. In addition, we searched PubMed, Google Scholar, PROSPERO, Scopus and Dimensions and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry platform. We conducted the search on the 20 February 2022 and included publications (peer reviewed studies and reports) in the past 10 years.

A key area of interest was implementation of continuity of midwifery care in LMICs but we recognised that reports of implementation may be published in formats other than peer reviewed publications. Eligible papers therefore included implementation studies or reports of implementation of midwifery continuity of care in the grey literature. We sourced grey literature through online searches on the websites of relevant professional groups, United Nations agencies and non-government organisations (NGO). We circulated a call for relevant materials through online list servs (email groups) and through midwifery contacts. The International Confederation of Midwives assisted by emailing all member associations asking for any relevant reports.

Eligible reports could report on midwifery continuity of care efforts in HICs and LMICs. Reports from implementation efforts by government programmes, private providers, professional organisations, NGOs and universities and research studies of any design were eligible for inclusion. Protocols that reported studies that were underway, but not concluded, were also eligible. Opinion pieces, editorials and other materials, which included details of midwifery continuity of care initiatives, were also eligible. Publications in any language were eligible. The search was limited to reports published in the last ten years (January 2012 to January 2022) to ensure the information was contemporary and therefore of greatest relevance to policy makers.

Reports identified through both peer-reviewed and grey literature databases were hand-searched for other potentially relevant studies. These included reference lists of relevant systematic reviews, and published conference abstracts, as well as any reports forwarded to authors in response to a call for notification of new or ongoing initiatives from key global stakeholder organisations, such as the International Confederation of Midwives.

Reports were excluded they if reported on midwifery continuity of care in general but did not report on a continuity of care practice initiative. We excluded systematic and literature reviews although their reference lists were searched for relevant primary studies.

Study selection

All reports identified through database searching were imported into Endnote referencing programme (Endnote 20, Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia), and duplicates removed. Remaining citations (n = 5789) were uploaded into systematic review software Covidence (Covidence 2022, Veritas Health Innovations, Melbourne). Two authors independently conducted initial title and abstract screening and undertook full-text review. A third author screened a random selection of 10% of studies and discrepancies were discussed and resolved.

Charting the data

The following information was extracted for all included reports: country, income-level (as defined by the World Bank [ 21 ], study design (if applicable), setting (urban/rural and community-based or facility-based), novel or scaled-up initiative, model of care, level of continuity (antenatal and intrapartum, antenatal and postnatal, intrapartum and postnatal) and cadre of care providers, (e.g. mix of providers involved). We also collected information on the inclusion of priority population groups–these are groups of people who are persistently disadvantaged by existing systems of power with demographic features known to be associated with adverse perinatal outcomes, such as ethnic minorities, urban and remote women, socially disadvantaged, and Indigenous women. We have described these specific groups as priority rather than vulnerable populations [ 22 ]. Reporting of the scoping review findings follows the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) format (see S1 Checklist ) and reference ( Fig 1 ) [ 23 ]. Appraisal of study quality or meta-analysis was not undertaken.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000935.g001

In total, 6595 references were identified from electronic peer-reviewed databases, 821 duplicate records were removed prior to uploading to Covidence, a further 634 duplicates were removed by automation. Of the 5136 remaining references, 4728 did not meet the inclusion criteria. A further 256 references were excluded at the full-text stage as either: they did not describe continuity of care according to our pre-determined criteria (167); did not include primary source data (42); were duplicates (41); or did not have insufficient detail regarding the model of care (6). One hundred and fifty-two (152) peer-reviewed publications were eligible based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. A further 23 reports were identified following the grey literature search, bringing the total to 175 ( Fig 1 ). Details are listed in S1 Table .

Of the 175 individual reports, 152 (86.8%) were peer reviewed publications, 18 (10.3%) were conference abstracts, and the remaining five (3%) were published or unpublished reports. Reports primarily reported on birth outcomes (n = 54, 31%), women’s (including some partners’) views and experiences (n = 47, 27%) and midwives (including doctors) views and experiences (n = 33, 19%). There were 18 reporting on the model of care more broadly, including implementation challenges (n = 18, 10%), and 14 (7%) that were focussed on the experience of midwifery students providing continuity of care as part of their education. The majority of these student-focused reports were from Australia. Fewer reports focussed on the experience of midwifery managers (n = 3, 2%), while four were cost analyses (2%).

There were 163 unique studies including eight (4.9%) randomised or quasi randomised trials, 58 (38.5%) qualitative, 53 (32.7%) quantitative (cohort, cross sectional, descriptive, observational), 31 (19.0%) survey studies, and three (1.9%) health economics analyses. There were 10 practice-based accounts that did not include research.

‘The where’: Country and setting

Of the 175 included reports, the majority (n = 157, 90%) were from HICs and 18 (10%) from LMICs ( Table 1 ). Most were from Australia, (n = 71, 41%), followed by the United Kingdom (England, Scotland, Wales) (24, 14%), Sweden (13, 8%), Canada (8, 5%), Denmark (6, 4%), New Zealand (7, 4%), Japan (5, 3%), with less than five reports described initiatives conducted in Belgium, Finland, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Netherlands, Norway, Singapore, Switzerland and the United States of America (USA). In the LMICs, three from Palestine, three from China, two each from Bangladesh and Indonesia, and one from each of the remaining countries.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000935.t001

Overall, most midwifery continuity of care models were based in urban areas (n = 126, 72%). In HIC, three-quarters of services (n = 118, 75%) were urban-based, whereas in LMICs just under half (n = 8, 44%) were urban-based. Hospital or facility-based services were most common across all income levels (n = 124, 72% overall).

‘The how’: Describing the way continuity of care is provided

There were a number of different terms used to define the model of care, and the level of continuity provided across the continuum of care varied with no single term used. Overall, the most common terms were caseload midwifery (n = 63, 36%), midwifery-led continuity (n = 60, 34%), or team/midwifery group practice (n = 40, 23%). Most described services designed so that the same providers provided care across the continuum–antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal (n = 159, 91%). There were eight which described continuity only across the antenatal and postpartum periods [ 24 – 31 ] (excluding labour and birth), and five reported [ 32 – 36 ] (including 3 unique examples) where the continuity was provided only across antenatal and intrapartum periods without postpartum care.

In HICs, the most dominant approach is where small groups of midwives provide care for designated women, known as caseload midwifery or midwifery group practice in countries like Australia [ 37 ], the United Kingdom [ 9 ], Denmark [ 38 ], Sweden [ 39 ], and Singapore [ 40 ] where the number of midwives is usually two to four. In other countries, for example, Japan [ 41 ] and Switzerland [ 42 ], the approach is also called team midwifery and the number of midwives is five or more.

The continuity of care services were located as part of the usual hospital [ 37 , 43 ], in an alongside birth centre [ 44 – 46 ] or in a free-standing birth centre [ 47 ]. Some midwife-led continuity of care services were offered through homebirth practices, either as part of the hospital system [ 48 , 49 ] or as a private service [ 50 ]. Most services were based in urban areas but there were some examples from rural areas in Australia [ 51 – 53 ], Sweden [ 54 – 56 ] and Scotland [ 57 ] ( Table 2 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000935.t002

Although midwife-led continuity of care was available in a number of countries, mostly high-income with a cadre of midwives, in select facilities and locations, it was generally not scaled-up nationally. The exception being New Zealand, where the Lead Maternity Carer model is national allowing to midwives provide continuity of care to all women regardless of risk, in either caseloading or small community-based group practices, under a national funding arrangement and with medical or other collaboration when required [ 58 ].

In LMICs there was greater diversity in structure of arrangements for provision of midwifery continuity of care models. Models of care included a lead midwife delivering care across the continuum [ 59 , 60 ], midwives on-call for women during labour who they had previously seen for antenatal care [ 61 ], and a midwifery continuity of care team that ran in parallel with an obstetric team [ 62 ]. An initiative in Ethiopia involved the same midwife providing antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal care to the same women [ 63 , 64 ]. An initiative in Kenya involved midwifery care across the childbearing continuum, embedded within a family planning and HIV care service [ 65 ]. One initiative in China [ 66 ] facilitated continuity of care for women wishing to have a vaginal birth, where efforts were made for women to see the same midwife for intrapartum and postnatal care. In the Palestinian initiative [ 67 – 69 ], midwives were allocated geographical areas to provide antenatal and postnatal care for between 50–100 women. One initiative in Bangladesh [ 70 ] and another in Iran [ 71 ] involved teams of midwives providing care in a private midwifery clinic associated with two local hospitals.

Similar to HICs, continuity of care services were located as part of the usual hospital services (eg in Pakistan [ 59 , 72 ], China [ 61 ], Ethiopia [ 63 , 64 ], Palestine [ 67 – 69 ] or in community health centres or maternity clinics, for example in Bangladesh [ 60 , 70 ], Kenya [ 65 ] and Afghanistan [ 73 ]. Most services were based in urban or semi-urban areas but there were some examples from rural areas, for example, Palestine [ 67 – 69 ], Bangladesh [ 70 ], Afghanistan [ 73 ] and Indonesia [ 74 ].

Reports from China [ 62 ], Ethiopia [ 63 ], Iran [ 71 ], Kenya [ 65 ] and Pakistan [ 59 ] provided some degree of continuity of care across all antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal periods. Two reports, one from China [ 61 ] and the one from Kenya [ 65 ] provided care across antenatal and intrapartum. A study in China [ 66 ] involved the provision of midwife-led care at antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal time points, but continuity of care with the same/a known provider was only guaranteed at intrapartum and postnatal time points. S1 Table provides more details on each of the initiatives and S2 Table gives additional detail on models of care from LMICs.

The ‘by whom’: Providers of midwifery continuity of care

Midwives were the dominant provider of continuity of care across all settings. Services were mostly midwife-led with some reports including other cadre as well. Integration with existing services including systems for referral to obstetric services when needed was usual.

In HIC, almost all models of continuity of midwifery care involved care provided by midwives and/or midwifery students. A small number included midwives and other cadre. For example, programs with midwives and Aboriginal Health Workers (Indigenous health providers) [ 14 , 75 – 78 ]; collaborations with general practitioners, obstetricians or a social worker [ 44 , 79 – 81 ]. Just two examples did not include midwives; a model in Finland where continuity of care is provided by a nurse who takes care of the family from the pregnancy until the child reaches school age [ 26 , 82 ], and an example in Ireland [ 83 ], where continuity of care was provided by a privately practising obstetrician.

All except two of the continuity of care initiatives in LMICs were midwife-led. The initiative from Ghana [ 84 ] was provided by midwives, nurses and doctors while the one in Kenya [ 65 ] was provided by community based midwives who may have nursing or midwifery qualifications and other health professional with obstetric skills who reside in the community.

There were 16 reports which described midwifery students providing continuity of care, most of these were from Australia, Norway and Indonesia [ 74 , 85 – 101 ]. Midwifery students were placed with women, providing continuity of care to a defined number of women over their education program, as a way to engage them in this model of care [ 91 , 94 ].

The ‘for whom’: Priority groups for continuity of care initiatives

Of the 175 initiatives, 44 (25.5%) of these were implemented for women and newborns with risk of adverse outcomes ( Table 3 ). These included women from Indigenous communities, refugee and migrant populations, young mothers, women living in rural and remote areas, women who experience socioeconomic disadvantage, women with a history of substance abuse, chronic illness, and ethnic minority groups. The majority were from Australia [ 23 ], United Kingdom [ 9 ] and Canada [ 3 ]. There were four examples from LMICs, these were designed primarily for rural and remote communities in Palestine [ 67 – 69 ], Bangladesh [ 70 ], Afghanistan [ 73 ] and Kenya [ 84 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000935.t003

This scoping reviewed aimed to map where, how, by whom, and for whom are midwifery continuity of care models are being implemented globally. The majority of models identified were in HICs, largely in Australia and the United Kingdom. Notably, all countries where five or more continuity of midwifery care initiatives were identified in the last 10 years are high-income and provide free public healthcare to their citizens and have a distinct cadre of midwives which makes this possible (Australia, Canada, Denmark, Japan, New Zealand, Sweden, and United Kingdom). Only 18 initiatives were identified in LMICs.

There is a growing body of literature demonstrating beneficial effects of midwifery continuity of care [ 4 , 8 ]. Midwifery continuity of care is a complex, multi-faceted intervention and teasing out which elements impart benefit to recipients of care is difficult. We found that almost all papers included in this review, involved continuity of care initiatives led by midwives or midwifery students (with midwife supervision). This was despite casting the net wide to identify continuity of care initiatives provided by any health provider across two or parts of the maternal and newborn care continuum.

Reviews of continuity of care in maternal and newborn care have focused on midwife-led continuity of care compared with other models of care such as doctor-led and shared care models [ 4 , 102 ]. However, a previous integrative review of midwife-led care in LMICs, found that just over half of studies included in the review included only midwives, with other cadres of health professionals including nurses, nurse-midwives, doctors, traditional birth attendants and family planning workers [ 103 ]. Whilst there is scope for other non-midwife health providers to provide continuity of care, such as family physicians [ 104 ]and community health workers [ 105 ], which may particularly be of value in LMICs countries where there is a shortage of midwives [ 106 ], there are few studies or reports available about these continuity of care models and their benefits. Although other cadre are not precluded from providing continuity of care, this review has shown that in the global literature, continuity of care across the maternal and newborn continuum is reported to be almost exclusively provided by midwives and is a significant area of quality improvement and research interest for midwives.

An encouraging finding from this review was the significant proportion of initiatives in HICs which focussed on women and newborns with vulnerabilities related to social and economic determinants of health (23.2%). The evidence that such initiatives are feasible for a diverse range of priority groups across many countries could demonstrate recognition of the benefits of continuity of care in improving outcomes for those with greater social and economic barriers to good health outcomes. This has implications for future research in that previous studies exploring childbirth outcomes from midwifery continuity of care frequently involve low-risk women [ 4 ], or women who had self-selected to be part of a midwife-led care project and thus are more likely to experience a positive outcome. This review has revealed that initiatives in a range of settings involve groups acknowledged to be at increased risk of adverse outcome. Larger scale and robust studies of midwifery continuity of care initiatives involving populations who experience social and economic disadvantage, and/or are at increased obstetric risk are both feasible and desirable.

Implications for policy, practice, research

This review has revealed that most studies, or reports, on midwifery continuity of care describe models led by midwives within HICs. Despite the benefits of midwife-led continuity of care, none of these countries has managed to scale-up this approach to being the standard of care at a national level, other than New Zealand. This highlights the organisational challenges of widespread implementation and the importance of system-level reform to enable countries to transition to this model of care and to scale-up. This reform means having adequate funding, support to enable midwives to be educated, and regulated, to work to their full scope of practice including flexibility and autonomy, self-managed time, team space, telephone access, and being able to work safely in the community and having access to transport and referral services [ 8 , 107 ].

Fewer than 10% of initiatives included in this review were from LMICs and only one was a clinical trial. The greatest burden of maternal and newborn deaths and stillbirths exists in LMICs. In HICs, midwife-led continuity of care has potential to reduce preventable maternal and newborn mortality and morbidity and stillbirths, however system-level reform and ensuring an enabling environment is still key [ 44 ]. The lack of midwifery continuity of care initiatives in LMICs, highlights the need for greater investment to ensure well-functioning midwifery systems can be developed with monitoring, evaluation and research to understand the effect of different models and associated benefits and/or challenges in different contexts. Operational research that identifies the barriers, facilitators and blockages to implementing models of midwifery continuity of care is needed, including in settings where there are shortages of midwives. In order to facilitate transition to, and scale-up of, midwifery continuity of care in LMICs, key considerations include strengthening midwifery education and regulation and ensuring the presence of an enabling environment [ 66 , 73 ].

Future systematic and scoping review studies would be enhanced by clear reporting of midwifery continuity model type, implementation details (including on midwife competence, scope of practice, deployment) and degree of continuity achieved within published studies and reports. Establishment of a classification system for this purpose would also enhance implementation efforts. One example of a classification system in a country which has an identifiable cadre of midwives is the Maternity Care Classification System (MaCCS) which was developed to classify, record and report data about maternity models of care in Australia [ 108 , 109 ]. The MaCCS includes a series attributes including the target groups, profession of provider, the caseload size, the extent of planned continuity of care and the location of care to come up with 11 major model categories (see S3 Table for details) [ 110 ]. This classification system is now being included in all routine data systems in Australia so that, in the future, outcomes by model of care will be reported. While this is developed for one high-income country, an adaptation for global utility could be useful.

Measuring the extent to which continuity of care is achieved is the second key area. The health insurance industry in the USA has developed measures to assess patterns of visits to providers and therefore, the level of continuity of care [ 111 ]. The measures include the Bice-Boxerman Continuity of Care Index (measures the degree of coordination required between different providers during an episode), the Herfindahl Index (the degree of coordination required between different providers during an episode), the Usual Provider of Care (the concentration of care with a primary provider) and Sequential Continuity of Care Index (the number of handoffs of information required between providers). The Usual Provider of Care index has also been used to assess continuity of care in general practice in the UK, that is, to assess the proportion of a patient’s contacts that was with their most regularly seen doctor [ 112 ]. For example, if a patient had 10 general practitioner contacts, including six with the same doctor, then their usual provider of care index score would be 0.6. With the exception of one study, none of the papers in this review had applied such indexes. This is an important consideration for the future.

Strengths and limitations

This review provides a summary of midwifery continuity of care efforts globally. As countries look to strengthen midwifery and quality of care for women and newborns during pregnancy, childbirth and postnatal periods, understanding implementation in all resource settings is important. In this review the broad criteria for inclusion allowed for identifying the maximum number of implementation efforts in LMICs to be identified. Despite the efforts to reach out, and although no language filters were applied, search terms were in English thus we may have missed some ongoing efforts. We also did not measure, or account for, the skills and competencies in the different cadres providing care, or if they are always deployed as midwives or provide details about the profile/qualifications of the healthcare providers, the way the midwifery system function, if any affiliation to healthcare centres, support systems, health costs and coverage or safety outcome indicators as these were reported differently or not at all across the papers. Finally, in this review we were not able to reliably determine the extent to which women receiving care were able to see the same individual care provider. Relational continuity is a key element of continuity of care, and possible mechanism for beneficial effects, which requires repeat contact over time between individual care providers and recipients of care.

Conclusions

This review mapped midwifery continuity of care initiatives globally. The majority of initiatives identified were in HICs, with fewer identified in LMICs. Almost all initiatives identified in LMICs were led by midwives (some of whom worked in a model in which they were also deployed as nurses), despite our efforts to identify models led by other skilled health professionals. Almost no countries have managed to scale-up midwifery continuity of care to being the standard of care at a national level. This highlights the organisational challenges of widespread implementation and the importance of system-level reform to enable these models of care to scale-up. Nevertheless, examples of successful implementation of midwifery continuity of care in low-resource settings reported show that advances in this area are possible.

A number of initiatives identified in HICs focused on women and newborns at risk of adverse outcomes, demonstrating the value of midwifery continuity of care in populations who experience social and economic disadvantage and vulnerabilities. There is a need for further research on midwifery continuity of care models in LMICs, and strategies to facilitate transition to, and scale-up of, midwifery continuity of care initiatives globally.

Supporting information

S1 text. search strategy..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000935.s001

S1 Table. All included items.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000935.s002

S2 Table. Additional details from low- and middle-income countries.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000935.s003

S3 Table. Major model categories in MaCCS.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000935.s004

S1 Checklist. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses extension for scoping reviews.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000935.s005

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Rana Islamiah Zahroh, PhD student and researcher at the University of Melbourne in Australia for assistance mapping the data. Thanks also to Rosemary Rowe, Subject Librarian at Faculty of Health, Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand and to Allisyn Moran and Joao Paolo Souza (WHO) for useful feedback and advice.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 5. World Health Organization. Global strategic directions for nursing and midwifery 2021–2025. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021.

- 15. World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

- 16. World Health Organization. WHO recommendations: intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

- 17. World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on maternal and newborn care for a positive postnatal experience. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022.

- 21. World Bank. World Development Indicators 2022. https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=world-development-indicators .

- 24. Cummins A, Griew K, Devonport C, Ebbett W, Catling C, Baird K. Exploring the value and acceptability of an antenatal and postnatal midwifery continuity of care model to women and midwives, using the Quality Maternal Newborn Care Framework. Women and Birth. 2021.

- 31. Health Synergy and Collaborative Business. Logan Community Maternity and Child Health Hubs Cost Analysis. Brisbane: Synergy Health and Business Collaborative; 2021.

- 35. Markesjö G. Women’s experience of pregnancy and childbirth in a continuity of care model. A qualitative study at Huddinge Hospital. Stockholm: Karolinska Institute; 2019.

- 36. Holroyd M. Midwives experiences of working within the project “Min Barnmorska”. Stockholm: Karolinska Institute; 2019.

- 63. Hailemeskel S, Alemu K, Christensson K, Tesfahun E, Lindgren H. Midwife-led continuity of care improved maternal and neonatal health outcomes in north Shoa zone, Amhara regional state, Ethiopia: A quasi-experimental study. Women and Birth. 2021.

- 70. Rahman S. Midwife led Care Centre in a Government Facility: Charikata Union Health and Family Welfare Centre (UH&FWC), Jaintiapur, Sylhet. 2021 Wednesday, Apr 20, 2022.

- 85. Baird K, Hastie C, Stanton P, Gamble J. Learning to be a midwife: Midwifery students’ experiences of an extended placement within a midwifery group practice. Women and Birth. 2021.

- 94. Newton M, Faulks F, Bailey C, Davis J, Vermeulen M, Tremayne A, et al. Continuity of care experiences: A national cross-sectional survey exploring the views and experiences of Australian students and academics. Women and Birth. 2021.

- 99. Tickle N, Gamble J, Creedy D. Clinical outcomes for women who had continuity of care experiences with midwifery students. Women and Birth. 2021.

- 106. UNFPA. State of the World’s Midwifery New York: United Nations Population Fund; 2021.

- 107. World Health Organization. Strengthening quality midwifery education for Universal Health Coverage 2030: framework for action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019.

- 108. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Maternity Care Classification System: Maternity Model of Care Data Set Specification national pilot report November 2014. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2014.

Midwife-led birthing centres in four countries: a case study

- Open access

- Published: 17 October 2023

- Volume 23 , article number 1105 , ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Oliva Bazirete 1 , 2 ,

- Kirsty Hughes 2 ,

- Sofia Castro Lopes 3 ,

- Sabera Turkmani 4 ,

- Abu Sayeed Abdullah 5 ,

- Tasleem Ayaz 6 ,

- Sheila E. Clow 7 ,

- Joshua Epuitai 8 ,

- Abdul Halim 5 ,

- Zainab Khawaja 9 ,

- Scovia Nalugo Mbalinda 10 ,

- Karin Minnie 11 ,

- Rose Chalo Nabirye 8 ,

- Razia Naveed 9 ,

- Faith Nawagi 10 ,

- Fazlur Rahman 5 ,

- Saad Ibrahim Rasheed 9 ,

- Hania Rehman 9 ,

- Andrea Nove 2 ,

- Mandy Forrester 12 ,

- Shree Mandke 12 ,

- Sally Pairman 12 &

- Caroline S. E. Homer 4

1957 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Midwives are essential providers of primary health care and can play a major role in the provision of health care that can save lives and improve sexual, reproductive, maternal, newborn and adolescent health outcomes. One way for midwives to deliver care is through midwife-led birth centres (MLBCs). Most of the evidence on MLBCs is from high-income countries but the opportunity for impact of MLBCs in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) could be significant as this is where most maternal and newborn deaths occur. The aim of this study is to explore MLBCs in four low-to-middle income countries, specifically to understand what is needed for a successful MLBC.

A descriptive case study design was employed in 4 sites in each of four countries: Bangladesh, Pakistan, South Africa and Uganda. We used an Appreciative Inquiry approach, informed by a network of care framework. Key informant interviews were conducted with 77 MLBC clients and 33 health service leaders and senior policymakers. Fifteen focus group discussions were used to collect data from 100 midwives and other MLBC staff.

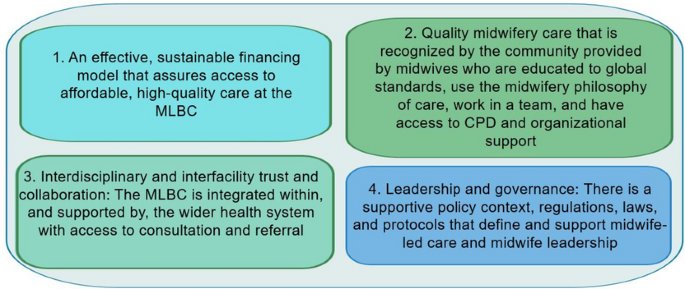

Key enablers to a successful MLBC were: (i) having an effective financing model (ii) providing quality midwifery care that is recognised by the community (iii) having interdisciplinary and interfacility collaboration, coordination and functional referral systems, and (iv) ensuring supportive and enabling leadership and governance at all levels.

The findings of this study have significant implications for improving maternal and neonatal health outcomes, strengthening healthcare systems, and promoting the role of midwives in LMICs. Understanding factors for success can contribute to inform policies and decision making as well as design tailored maternal and newborn health programmes that can more effectively support midwives and respond to population needs. At an international level, it can contribute to shape guidelines and strengthen the midwifery profession in different settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Reasons for home delivery and use of traditional birth attendants in rural Zambia: a qualitative study

Cephas Sialubanje, Karlijn Massar, … Robert AC Ruiter

Iranian midwives’ lived experiences of providing continuous midwife-led intrapartum care: a qualitative study

Leila Amiri-Farahani, Maryam Gharacheh, … Sally Pezaro

Why do women not deliver in health facilities: a qualitative study of the community perspectives in south central Ethiopia?

Meselech Assegid Roro, Emebet Mahmoud Hassen, … Mesganaw Fantahun Afework

Access to quality sexual, reproductive, maternal, newborn and adolescent health care is essential for countries to achieve universal health coverage (UHC). Midwives are key in this endeavour. Midwives have the potential to impact maternal and newborn health outcomes, if they are adequately educated, deployed and supported in an enabling work environment. Universal access to midwife-delivered interventions could prevent two-thirds of the world’s maternal and newborn deaths and stillbirths [ 1 ].

Midwife-led birthing centres (MLBCs) are an option in many countries [ 2 ]. MLBCs are usually provided at a primary care level, have a dedicated space providing childbirth care where midwives are the lead professionals and have arrangements for consultation and referral to secondary and tertiary-level services if needed. Some MLBCs are close to, or an integral part of, a maternity or general hospital (called “alongside” or “on-site” centres) while others are situated apart from hospitals (called “stand-alone” or “freestanding” centres).

MLBCs that are appropriately integrated into the health system have been found to improve maternal and neonatal outcomes by providing woman-centred, high-quality, cost-effective, and safe care [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ]. A recent Cochrane review examined 15 trials with 17,674 women from high-income countries and found that midwife-led continuity of care offers various favourable outcomes for women when compared to other care models [ 9 ].

Most of the evidence on MLBCs is from high-income countries, but the impact of MLBCs in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) could be significant as this is where the vast majority of maternal and newborn mortality and morbidity occurs [ 10 ]. However, we cannot assume that research findings from HICs can be generalised to other settings. For example, MLBC clients in HICs tend to belong to more wealthy demographics, [ 3 ] whereas in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), MLBCs primarily cater to clients from disadvantaged and marginalized communities [ 11 ]. The weak referral systems evident in many LMICs may compromise the safety of women and newborns who use MLBCs, especially if the MLBC is a freestanding one (the most prevalent type in LMICs [ 11 ]), whereas in HICs the evidence indicates better outcomes in freestanding MLBCs [ 3 ]. Further, in low-income nations, MLBC services are predominantly offered by private, not-for-profit entities. Consequently, the accessibility of care for clients from underprivileged and marginalized backgrounds heavily relies on sustained support from these sources [ 11 ].

Our previous work has shown that MLBCs exist in at least 24 LMICs [ 11 ]. Much of the evidence about these MLBCs was collected in a survey and there was limited information in the peer reviewed literature, especially understanding how the MLBCs were successful. The aim of this study therefore, was to explore MLBCs in four low- and middle income countries, specifically to understand what is needed for a successful MLBC.

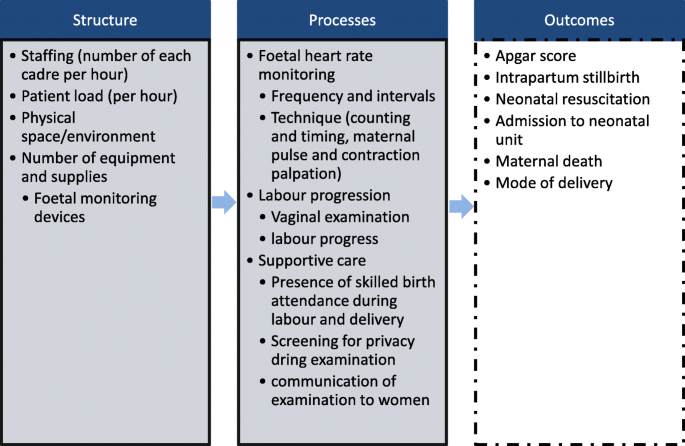

Study design

A descriptive study with four case study countries was undertaken using an Appreciative Inquiry approach [ 12 ]. Appreciative Inquiry is a participatory technique designed to initiate a positive conversation about experiences, needs, and proposed solutions [ 13 , 14 ]. The study was guided by a networks of care (NOC) framework with four domains: agreement and enabling environment, operational standards, quality/efficiency/responsibility, and learning and adaptation. The domains include access, quality of care, financing, community buy in, referral systems, supply and resources of health services [ 15 ]. The NOC framework guided site selection, data collection approaches and the initial analytic processes. The project established an expert advisory group (EAG) that included experts in MLBCs from high-, middle- and low-income contexts and representatives of the International Confederation of Midwives (ICM), World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and World Bank. This EAG met three times during the project to provide advice and guidance.

Prior to commencing the study, human research ethics approval was received through the Alfred Hospital HREC in Australia and from a relevant ethics committee within each of the four countries.

Country and site selection

Country selection was informed by a literature review and scoping survey, [ 11 , 16 ] and consultation with ICM and the EAG. The main inclusion criteria were: (a) the country was classed by the World Bank in 2022 as low-, lower-middle, or upper-middle income, (b) there was evidence from the literature and the survey that the country had at least four MLBCs that were either in the public sector or well-integrated within the national health system, (c) good research capacity within the country, and (d) data was available for an economic analysis (to be reported separately). Each country was invited to participate through the national Ministry of Health (MoH) with the ICM member association (MA).

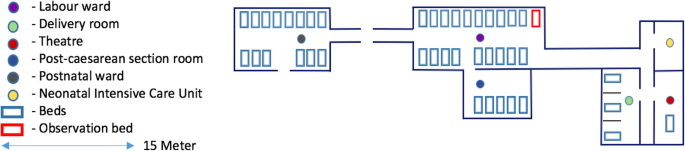

Four study sites were selected in each country based on a desk review of the literature and in consultation with the MoH, the MA, the national research team, the site manager(s) and other relevant stakeholders (Table 1 ). To be counted as an MLBC, a facility had to be a dedicated space providing childbirth care where midwives were the lead professionals providing care. The midwives were those recognised in each country as midwives. The MLBCs may also have other staff including nurses, lay health workers, assistants-in-midwifery, laboratory technician and pharmacy staff.

Study participants, recruitment and data collection

Three groups of informants were purposively selected in each country: health service leaders (defined as midwives, doctors, policymakers, or program planners who, within the preceding two years, had held a leadership role within the maternity care system at a national or sub-national level), MLBC staff (92% of whom were midwives) currently working at one of the selected MLBCs (Table S 1 : **Definitions of a midwife by country participating in this study**), and MLBC clients (women aged 18 or over who had planned to give birth in one of the selected MLBCs within the preceding six months, including those who had been transferred to another facility). Leaders were selected in consultation with the MoH and the ICM MA. Staff and clients were nominated by the MLBC managers.

Leaders, staff and clients were interviewed separately. Staff were interviewed in focus group discussions (FGDs), or individually if the MLBC was operated by a single midwife. All interviews with clients and staff were conducted in the most appropriate language for that informant or site. The leader interviews were conducted in the informant’s preferred language. FGDs were conducted in a private location at or close to the MLBC. The FGDs lasted between 60 and 90 min and the individual interviews between 30 and 60 min. The majority of the interviews (105/125; 84%) were conducted in person, with the others on the phone or online using Zoom or MS Teams. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed in the original language before being translated into English for analysis. The researchers recorded field notes during and after gathering data in order to document the nonverbal cues and significant details observed from the respondents. The study was conducted from September 2022- April 2023.

A total of 210 informants participated: 34–66 per country (Table 2 ).

Data collection tools were developed by the research team based on a NOC framework [ 15 ] and guided by the Appreciative Inquiry approach [ 14 ]. We did not provide a definition of “successful” for the study participants. Rather, we asked them to describe and explore what was working well; and explored what was valued by the participants, including their vision of the ‘ideal’ situation. These aspects of the Appreciative Inquiry approach provided evidence for what makes a ‘successful’ MLBC from the perspectives of the three participant types.

The country research team had a virtual orientation training with international consultants on data collection using the Appreciative Inquiry approach and the team in each country consisted of members with expertise in qualitative research methodology, maternal health and health care. There was a team of 20 researchers in the countries who undertook the data collection. Of these, 15 were women, and 5 were men and all were nationals in the individual country.

Data analysis

Data analysis was undertaken concurrently with data collection and was initiated after the completion of the first interviews. The translated transcripts were read by a team of four analysts (all women: OB, KH, SCL and ST) who used NVivo software to help organize the data for further analysis. Data were initially categorized under the 4 overarching themes represented in the NOC framework: 1) agreement and enabling environment, 2) operational standards, 3) quality, efficiency and responsibility, 4) learning and adaptation [ 15 ]. The next step interrogated the initial analysis asking: (i) What are the enablers, i.e. factors that make MLBCs successful (as defined by individual informants)? (ii) What are the main challenges facing MLBCs? (iii) Do these enablers and challenges vary according to MLBC type (freestanding vs alongside/onsite) and sector (private vs public)? We identified the themes from each of these questions by country and by participant group using an inductive approach and then searched for commonalities and differences. These findings were presented back to the country teams who had collected the data to ensure that the interpretation was sound. Revisions were made and further cross-checking and refinement took place. We then combined the findings across the matrix of country and participant group to produce the synthesized results.

The results are presented initially by context and then what is needed for a successful MLBC. The wider analysis also included the key barriers facing MLBCs and differences between private/public and freestanding/alongside MLBCs (Table S 2 : **Barriers facing by MLBCs and key differences between different types of MLBCs**).

The four selected countries have different strengths and challenges in relation to maternal and newborn health indicators as indicated by Table S 3 (Table S3** Key maternal and newborn health statistics for the four countries**).

What is needed for a successful MLBC?

Although the findings varied by country, four universal themes described the enabling factors influencing successful MLBCs as illustrated by Fig. 1 . These were: (1) an effective financing model (2) quality midwifery care that is recognised by the community (3) interdisciplinary and interfacility collaboration, coordination and functional referral systems, and (4) supportive and enabling leadership and governance at all levels.

Facilitators of success for midwife-led birthing centres

An effective financing model

A number of different financing models for MLBCs services were identified. These included external funding model (non-governmental organizations (NGOs), donors, faith-based organizations, among others), governmental funding model and a combination of two or more funding models. All four countries had external funding models with funders including UN agencies and NGOs, but few South African MLBCs have external funding. Partnerships with these external funders helped to make childbirth care affordable at MLBCs and provided support through donations, as seen in Bangladesh, Pakistan and Uganda. These partnerships improved service utilisation as seen in Bangladesh:

“Mostly people from the neighbourhood areas come here. They only need to pay for transportation … several NGOs are providing incentives. In that case, a mother is given BDT 500 for a normal delivery. The medication is available here ... It doesn’t cost much. Incentives are supported by UNFPA and [specific programmes], sometimes helps with referrals.” (Staff Bangladesh)

Sometimes, however, the support was limited and staff had to use their own funds:

“NGOs provided us with a painted delivery room … I spent my own money to renovate windows, walls, and doors. They [NGOs] do not understand that we are working without any facilities on a low income.” (Staff Pakistan)

In South Africa, public sector health care included public MLBCs, where pregnant women and children under the age of 6 years are entitled to free health care at the point of care. Government support was also observed in the public health sector in Bangladesh and Pakistan where the government provides infrastructure for MLBCs and the public MLBCs offer free healthcare services. Free services promoted accessibility:

“I will come here again. I like it here; their way of communicating is very good. I didn’t have to pay anything here; everything is done here for free ... Since it is free and the government pays the expenses here, my relatives will come here happily.” (User Bangladesh)

“Mostly our clients are poor and can’t access private services. So they come here… normal delivery is easily done here, and every medicine is free” (Staff Pakistan).

In Uganda, where the selected MLBCs are all private (some for-profit and some not for profit), priority is given to providing health care to the service user, with payment being made later or some initiative to substitute the cost of care, for example, work in exchange. Two staff members explained:

“ … you do not know if she has money or if she doesn’t have money. So you have to first deliver then after she can tell you “I will send the money”.” (Staff Uganda)

“We ask that people either give about five thousand shillings if they can but it is not required or that they can we have some work exchange. People can come and work for a bit and do digging or different things.” (Staff Uganda)

Different financial models according to the context of the country and flexibility were important to ensure that service users have access to necessary health care without facing financial hardship.

Quality midwifery care that is recognised by the community

Successful MLBCs were those recognised by the community as providing quality care in a respectful way. Respect and maintenance of confidentiality for women accessing the MLBC and being treated with dignity and compassion were all important. Midwives in the MLBCs supported physiological labour and birth, catering to the women’s cultural and language needs, establishing strong relationships and ensuring continuity of care. Quality midwifery care included being provided with accurate and unbiased information about their options, being enabled to make informed decisions about their care, and being supported in their choices. Service users explained:

“…someone understands that you are in pain and they comfort you knowing that if she distances herself from you, you can even die. That love that she is there with you at every point, taking care of you and when you say that I have failed here she is there with you. When you need something she is there with you 24/7. She cares about you and wants your baby to be born well, that nothing happens but for the wellbeing of you and your baby.” (User Uganda)

“She [the midwife] never scolded me or anything like that. She treated me with love and respect. She always answered any question I had. She gave me reassurance and told me that I can call for her whenever I need help.” (User Pakistan)

The examples from Bangladesh and South Africa highlight the value that women placed on receiving care that was respectful, supported physiological labour and birth and reduced the risk of unnecessary interventions:

“The service providers helped me by respecting my decision to have a normal delivery. I may need something that tells them what they need to look at carefully. In terms of language, there was no difference between them, whether they were poor or rich. Everyone is treated equally.” (User Bangladesh)

“I wanted proper care for me and my child. I knew early that I wanted to give birth naturally and I knew that my chances for natural birth would be more reduced when going to a doctor [at a hospital] than going to a midwife [at an MLBC].” (User South Africa).

This support of physiology was not at the expense of a healthy baby: “… She [the midwife] cares about you and wants your baby to be born well, that nothing happens but for the wellbeing of you and your baby” (User Uganda).

Midwives in MLBCs ensured that women felt welcomed and supported. The staff and leaders recognised that this built trust and was important:

“Patients trust this [MLBC] as we provide good service, take care of their privacy and their self-respect as well.” (Staff Pakistan)

“First of all, respect for maternity care is encouraging for [MLBCs]. …When mothers come to these places and see that they can open up, get respect, and give birth the way they want, they gain confidence.” (Leader Bangladesh)

In South Africa, the involvement of partners and family members during childbirth was highly valued by some MLBC users. They said that midwives accommodated family members and this partner involvement increased awareness of the MLBC:

“ They [the MLBC] were very accommodating, because initially I thought that I am going to give birth with my husband there and then my two sisters came along and then they were very accommodating and then they also involved them throughout like from the labour process and then also assistance …”(User South Africa)

Cultural and linguistic sensitivity were critical factors in the success of MLBCs. For instance, in Pakistan, service users highlighted that midwives acknowledged and respected the cultural values, beliefs, and practices of the communities they served. The midwives encouraged open communication with the women in their care, which allowed for the sharing of cultural practices and beliefs. Many women from Pakistan felt that the midwives in the MLBC respected their privacy, observed purdah (female seclusion) requirements, and communicated with them in their preferred language:

“We are Baravi speakers. She guides me in Baravi language. She was concerned about my privacy [so] there were no male members in her birth station.” (User Pakistan ).

“She took care of our purdah during check-ups and during childbirth as well.” (User Pakistan ).

Building a good relationship with MLBC users was important to provide quality midwifery services and the evidence to relationship is built on trust between midwives and community and on word of mouth:

“ I think it's the relationship between the client and the midwife and the respectful and kind care that is provided by the midwife. It also depends on the feedback that you receive from other people like your sister or your relatives and a lot of community’s trust is built in that way. So I think the [MLBCs] are affordable, acceptable and provide clean quality care and then there are the sources of comfort and respect ”. (Leader-Pakistan)

“What I found very interesting is that the men/partners become the biggest advocates of midwife-led care or birth centres. They are the ones that then tell their friends, listen you know that this is a good place to give birth.” ( Staff South Africa)

Midwives identified that different aspects of quality of care were key to success, including care across the continuum, and providing remote services. Many MLBCs – especially the freestanding ones—also provided antenatal care. For example:

“ that relationship begins from antenatal … it can begin when we go to the community and we talk about the availability of this facility [the MLBC], so the relationship begins. And then when they come, the way we talk to them, the way when we are examining them, touching them and talking to them as a family, husband and wife … that puts us together.” (Staff Uganda)

“The tasks here are the antenatal care (ANC) check-ups of pregnant mothers, ensuring four visits and quality control of the visits. They also provide remote ANC service through mobile. Many who do not come are called and brought for treatment. Also, the check-ups and various investigations at ANC are done in the hospital itself .” (Staff Bangladesh)

After birth, MLBCs users were also encouraged to attend scheduled postpartum appointments. In some MLBCs, users were provided with cards to contact the MLBC if any complication arises after discharge:

“ They gave us a card while we were going home from here. A contact number was given on that card so that I could contact them if any complications arose. ” (User Bangladesh).

“… she [the midwife] was already planning to come the following day, but she said if anything concerns you in this next 24 hours you can just give me a call you know I can come to the house.” (User South Africa).

Respectful care is a key contributor to success but is still a challenge to achieve, especially when there are midwife shortages. In some settings, clients experienced long wait times, inadequate communication, and lack of timely access to necessary care, especially for the referrals which did not always take place in a timely manner. To address this and ensure success, supportive counselling sessions were organised for midwives at MLBCs in South Africa:

“We used to have a psychologist … because … to be a midwife sometimes can be very draining because they have been long in labour and sometimes you must look after two patients and you don’t have patience all the time because we are also human, you also coming with the baggage so that it came in that the leader must also look at the staff as a person.” (Staff-South Africa)

A key to a successful MLBC was the recognition that the centre provided quality care. Midwives were seen as integral to this success but needed access to ongoing education to ensure they were up-to-date with knowledge and skills. In service training was described as an essential component of ensuring that midwives at MLBCs have the knowledge, skills and attitudes necessary to provide high-quality care. Medical doctors, UN agencies and NGOs provided training that included refresher training, neonatal resuscitation and ultrasound:

“Many NGOs are providing training to fill gaps. NGOs include UNICEF, UNFPA. UNICEF provides us with a wide range of logistical support.” (Leader Bangladesh)

“In three months, basically we get a refresher on different subjects, its normally about the staff need" [referring to Essential Steps in Managing Obstetric Emergencies, Helping Babies Breathe training].” (Staff South Africa)

“We went to Karachi and attended ultrasound training and that was very good. Everyone from here went there one by one from training and that was good. Our knowledge increases from that training.” (Staff Pakistan)

Interdisciplinary and interfacility collaboration, coordination and functional referral systems

Collaboration, coordination and functional referral systems are needed for successful MLBCs. While the MLBC midwives are the lead professionals, collaboration with obstetricians, nurses, and other support staff and working as a wider team were important. “ I would say the common goal that we are having, no mother and child should die. Teamwork is key amongst all of us the midwife fraternity [sic].” (Leader Uganda). This sense of collaboration and teamwork was also expressed in South Africa and Pakistan:

“Yes I want to say what makes my day is everyone getting along and more patients giving birth and it is smooth, happy team work day, everyone is smiling, there is no fighting … It can get very hot and steamy in the labour ward, and … I do find that we all have good relationships with each other under those situations and we can still make good decisions now walking away from that knowing that you did the best with what we had.” (Staff South Africa)

“…We deal with everything together. ….. Our doctors are also very cooperative.” (Staff Pakistan).

Good coordination included flexibility in how the service is organised and enabled continuity of care:

”I liked that idea that even if my midwife was unavailable, there were back up ones that I could meet ahead of time and get to know a little bit about care, yeah just bit more of personal care.” (User South Africa)

Staff also valued being able to organise and coordinate their own work:

“That depends on us [how] we have to divide it [the work] shift wise. Sometimes we divide the burden in the shifts so that not all the burden is on the first shift. So we have to make those policies ourselves. We don’t have any pressure from our admin or head office. This is the work we do on our own with their cooperation and there isn’t any more change needed in that.” (Staff Pakistan)

A well-functioning referral system was critical for successful MLBCs to ensure that, when needed, women received appropriate and timely care at a referral hospital with advanced care. The referral system was facilitated by effective communication and coordination from MLBCs to referral hospitals. Staff and leaders explained:

“So, from up to down, we have free communication, policies and protocols that determine which patient is where, and they are appropriately referred and referred back again.” (Leader South Africa)

“There were identified sites where we would refer the patients and you ring the doctor before you send the patient. So, even if it’s like APH [Antepartum haemorrhage], PPH [Postpartum haemorrhage], now the doctor would say do a,b,c,d as you are coming with this patient and that was really beautiful. So having connections of where to refer, so that by the time the patient reaches there, there is somebody waiting for the patient.” (Staff Uganda)

“I like working here in an [MLBC] which is adjacent to the main labour ward because if there is any complication there are those intrapartum emergencies like shoulder dystocia, PPH, uterine inversion, so you are just close to labour ward of the hospital for further management.” (Staff South Africa)

“What I liked about this clinic is that they are able to quickly see the problem if you have it, then when they see that it is not theirs and they will not be able to help it, they are able to refer you to higher people who will be able to help you.” (User South Africa)

Some sites ensured there was feedback about the transfer or systems where staff keep in touch via phone with service users. For example in Bangladesh, leaders found this feedback important in order to ensure that service users get enough support to maintain health:

“...the patient is then transported by us to another health facility with a midwife. Even after the referral, we keep in touch with the mother every day through her mobile phone.” (Leader Bangladesh).

Supportive and enabling leadership and governance at all levels

Effective leadership and governance systems enabled successful MLBCs. Governance mechanisms in different forms were described and included policy, governmental support and recognition, coordination meetings, support for continues professional development and monitoring and evaluation to ensure the MLBCs function and are effective. Government support to MLBCs was seen as a contributing factor to quality of care and hence reduction in maternal and child mortality rates:

“The government supports this service led by midwives. That is why the government has created separate midwives for maternal and child health and is providing full cooperation. They are providing as much support as needed. The main objective of the government is to reduce maternal and child mortality rates and increase institutional deliveries. It is for these reasons that the government is supporting midwives.” (Staff Bangladesh)

“Well, we get support from the government in the sense that they recognize our practice, and we can transfer patients to [institution names].” (Staff South Africa)

“The district is very supportive. You can’t run this type of, you know, activity without support from the district and the community.” (Staff Uganda)

“[MLBCs] have developed good setups and made a good network but it all depends on how much support they got. It depends on how your seniors, supervisor, NGO or the government held your hand. So that is very important. Once they are backed up, they can do wonders.” (Leader Pakistan)

Coordination meetings and regular supervision involving MLBCs brought together stakeholders to discuss improving the quality and accessibility of MLBC services. Coordination meetings enabled MLBC staff, government officials, healthcare providers, community leaders and other stakeholders to share information and experiences and contribute to effective functioning:

“We have quarterly meetings … to review the performance of each facility. We have also monthly meetings for the in-charges to review our performance and then we also do quarterly supervision and we have tools that guide us that we use to assess the quality-of-care services. Then we also have, they also submit reports to the district and we enter them into our system.” (Leader Uganda)

“There was a monthly perinatal meeting and later there was ESMOE [Essential Steps in Managing Obstetric Emergencies]. So, I suppose I then also got to know how they function and then later on [community obstetrician] kind of really coordinated the [MLBCs] in Cape Town and he set up a meeting called MOUSE [Midwife Obstetric Units Support Executive].” (Leader South Africa)

It was also highlighted by staff in South Africa that availability of guidelines and protocols at the disposal of midwives facilitate in decision-making for transfer. Leaders in Pakistan also had guidelines and frameworks but these were not applied in private MLBCs:

“We do have written guidelines and protocols in labour ward and in the antenatal clinic that we follow especially when it comes to transfers, what to transfer, so we work according to the protocol.” [Staff South Africa]

“In the infrastructure [MLBC], there should be midwifery led policies rather than medical policies. There should be a midwifery led service framework and the policies should be according to it. So that women can get midwifery services rather than medical services.” (Leader Pakistan)

Effective leadership and governance play a crucial role in enabling the timely and accurate reporting of data, ensuring evidence-based services at MLBCs. The establishment of reliable monitoring and evaluation mechanisms at MLBCs is an essential element for their successful operation and impact.:

“Evidence is mainly maintained by register books. We maintain it step by step from entry to discharge ... Thus, evidence-based services are ensured. We have been given a register of maternity services from the government. We fill up the form as given there.” (Leader Bangladesh)

“ In the government centres, the data is present in two ways. Firstly it is present in the paper form where there are separate registers for antenatal patients, delivery and for postnatal. Now in the government centers of Punjab, a new system of registration called EMR has started, which is known as Electronic Medical Reporting. Through it, every patient’s registration is being done through an application.” (Staff Pakistan)

“We report to the district every month. They have a tool that they give us but then we also keep our own private records. So we record with, you know, we have our paper charts that we have on each client and then we have someone who takes those paper charts and puts them into a larger book and then we take that book once a month and we digitize it.” (Staff Uganda)

The need to accelerate progress on maternal and newborn health and wellbeing is widely recognised. Action is required to increase the availability and accessibility of maternal and newborn health care, and also to improve quality of care (including respectful care). Expanding access to MLBCs is one means of achieving these objectives. Prior to this study, most of the evidence about MLBCs came from high-income countries, and the extent to which conclusions based on this evidence were transferable to LMICs was not clear. This study in four LMICs demonstrates that MLBCs are a feasible and acceptable model of care in a wide range of settings. The findings highlight that leadership support, availability of adequate resources, and workforce development as potential factors contributing to the successful implementation of MLBCs in LMICs.

Scaling-up the MLBC model of care to reach more women in more countries requires attention to be paid to the enablers identified in this study. High level themes describing enablers are: (i) having an effective financing model (ii) providing quality midwifery care that is recognised by the community (iii) having interdisciplinary and interfacility collaboration, coordination and functional referral systems, and (iv) ensuring supportive and enabling leadership and governance at all levels. With these enablers in place, the potential for MLBCs to contribute to improved maternal and newborn health and wellbeing is enormous. Our findings are discussed in view of evidence from both LMICs and HICs (high-income countries).