Trafficked: Three survivors of human trafficking share their stories

Date: Monday, 29 July 2019

This story was originally published on Medium.com/@UN_Women

Across the world, millions of women and girls live in the long shadows of human trafficking. Whether ensnared by force, coercion, or deception, they live in limbo, in fear, in pain.

Because human trafficking operates in darkness, it’s difficult to get exact numbers of victims. However, the vast majority of detected trafficking victims are women and girls, and three out of four are trafficked for the purpose of sexual exploitation .

Wherever there is poverty, conflict and gender inequality, women’s and girls’ lives are at-risk for exploitation. Human trafficking is a heinous crime that shatters lives, families and dreams.

On World Day against Trafficking in Persons, three women survivors tell us their stories. Their words are testament to their incredible resilience and point toward the urgency for action to prosecute perpetrators and support survivors along their journeys to restored dignity, health and hope.

Karimova comes full circle.

When she was 22 years old, Luiza Karimova left her home in Uzbekistan and travelled to Osh, Kyrgyzstan with the hopes of finding work. However, without a Kyrgyz ID or university degree, Karimova struggled to find employment. When a woman offered her a waitressing job in Bishkek, the capital city in the north of Kyrgyzstan, she welcomed the opportunity.

But things took a turn for the worse after arriving in Bishkek. Karimova recalls that, “They held us in an apartment and took away our passports. They told us that we’d be photographed again for our new employment documents, to be registered as waitresses. It felt strange, but we believed them.”

Then, Karimova and the other women were put on a plane to Dubai, handed fake passports instead of their real ones, and shepherded to an apartment after landing. “We were to be sex slaves and do whatever the clients wanted. The next day I was sent to a nightclub and told that I would have to earn at least 10,000 USD by the end of the month,” says Karimova.

For 18 months, her life was consumed by the nightclub work. Upon leaving the club one evening, Karimova saw a police car approaching, and instead of running away, she stayed to let the police arrest her.

“I was deported back to Osh, and since my ID was fake, I spent a year in jail. I filed a police report, and three of the traffickers were captured”.

However, after being released from prison, Karimova was left to live on the streets, ashamed and unemployed. She went back to work in the sex industry until she was approached by Podruga, an organization that assists women subjected to sex and drug trafficking. “They offered me work. I wasn’t sure that I would fit in, but slowly I began to trust them,” she says.

Now, Karimova works to prevent the exact situation in which she found herself. As an outreach worker with Podruga, she visits saunas and other places where sex workers may be. “I often meet girls who dream of going to Turkey and Dubai, to earn more. I tell them, ‘please don’t go...There is nothing good for you there.’”

To prevent their futures from unfolding as hers did, Karimova provides the women with health and safety resources and information about legal aid. “To stop trafficking of women and girls, we have to inform people about the full consequences of human trafficking and how to detect the signs. It is critical to start raising awareness about this in schools, starting young, so that they do not become victims.”

To read more of Karimova’s story and her work to prevent human trafficking in Kyrgyzstan, see her full interview .

Life in limbo.

In the Lake Chad region of West Africa, the Boko Haram insurgency has taken a drastic toll on millions of families. Thousands of people leave home every day, putting their lives in the hands of smugglers in search of a better life.

At 17 years old, Mary did just that. She felt there was no future for her in her home of Benin City, Nigeria, so she sought opportunities elsewhere. She was put into contact with a man, Ben, who promised to pay her way to Italy and use his connections to find her a restaurant job.

Soon after meeting Ben, Mary was called to his house and made to swear that she wouldn’t try to run away. In March 2016, she, along with a group of boys and girls, left for Libya—a stop along their route to Europe.

In Libya, Mary found herself in peril. “Ben took two of us girls one night. He gave the other girl to another man, and he said to me if I didn't sleep with him, he would give me to another man and not bring me to Europe. He raped me,” Mary says.

She wanted out but had no means of contacting anyone back home. “I had to stay there for months until they called me to go on the boat,” she says.

When she was finally put on a boat to Italy, Mary was informed she would be living in a camp and work as a prostitute—unjust conditions that she had never agreed to and couldn’t escape.

“I can't go stand on the side of the road in the name of money," she says, her voice rising. "I have a future. Standing there, selling myself, would destroy my life. My dignity. Everything.”

Now, the people who paid Mary’s way to Italy are demanding money and threatening her mother back in Nigeria. Her voice falters as she explains that, “they said they would do something very bad to her if I don't send money.”

She waits in anguish until her documents are processed. “I'm so sad. I'm under so much pressure. I don't know what to do… I just want to be free. I want it to be over, even for just one day.”

Despite the immense suffering she’s experienced as a victim of human trafficking, Mary’s dream of a better life holds strong. “One day I will have my documents, I will have an education, I will have work,” she says with hope. She wants to become a lawyer and serve those who’ve been trafficked like she has. “I want to give justice to the girls that have to use their bodies for work.”

For more of Mary’s story and UNICEF’s efforts to end the trafficking of children, read the full article .

“I no longer feel alone.”

Khawng Nu, now 24 years old, is from Kachin, a conflict affected and impoverished state in northern Myanmar. There are few job opportunities, so when a woman from her village offered her work in a Chinese factory, Khawng Nu accepted the offer. However, upon arriving in China, Khawng Nu quickly learned that she had been deceived. The situation wasn’t at all what she was told it would be.

Khawng Nu had been trafficked to birth babies, a type of trafficking that accounts for 20 per cent of the trafficking of women in Myanmar . Khawng Nu recalls seeing more than 40 women on the floor of the building where she was kept, some as young as 16.

“They give pills to women and inject them with sperm for them to carry babies for Chinese men,” explains Khawng Nu. They were beaten and bullied at any sign of resistance.

Once the baby was born, the women would supposedly receive 1 million MMK (USD 632).

Khawng Nu managed to send a message home to her family, and, with the help of community leaders, the trafficking broker in her village was arrested, although he refused to disclose Khawng Nu’s location.

Eventually, Khawng Nu’s family was able to gather enough money from neighbors to pay the ransom for her return. When she came home to her village, Khawng Nu shared the names of other girls she had met in China with local authorities, and five were rescued and brought back.

Through the help of a local organization that partners with UN Women, Htoi Gender and Development Foundation, Khawng Nu is working toward a brighter future. “At first, when I returned, I felt ashamed and I didn’t want to show my face,” she recalls. “Now, after meeting with other women trafficking survivors through the peer group organized by Htoi, I no longer feel alone and seeing that there are other women who went through the same experience gave me courage.”

Read the full article for more of Khawng Nu’s story and how UN Women is working to end human trafficking in Myanmar.

- ‘One Woman’ – The UN Women song

- UN Under-Secretary-General and UN Women Executive Director Sima Bahous

- Kirsi Madi, Deputy Executive Director for Resource Management, Sustainability and Partnerships

- Nyaradzayi Gumbonzvanda, Deputy Executive Director for Normative Support, UN System Coordination and Programme Results

- Guiding documents

- Report wrongdoing

- Programme implementation

- Career opportunities

- Application and recruitment process

- Meet our people

- Internship programme

- Procurement principles

- Gender-responsive procurement

- Doing business with UN Women

- How to become a UN Women vendor

- Contract templates and general conditions of contract

- Vendor protest procedure

- Facts and Figures

- Global norms and standards

- Women’s movements

- Parliaments and local governance

- Constitutions and legal reform

- Preguntas frecuentes

- Global Norms and Standards

- Macroeconomic policies and social protection

- Sustainable Development and Climate Change

- Rural women

- Employment and migration

- Facts and figures

- Creating safe public spaces

- Spotlight Initiative

- Essential services

- Focusing on prevention

- Research and data

- Other areas of work

- UNiTE campaign

- Conflict prevention and resolution

- Building and sustaining peace

- Young women in peace and security

- Rule of law: Justice and security

- Women, peace, and security in the work of the UN Security Council

- Preventing violent extremism and countering terrorism

- Planning and monitoring

- Humanitarian coordination

- Crisis response and recovery

- Disaster risk reduction

- Inclusive National Planning

- Public Sector Reform

- Tracking Investments

- Strengthening young women's leadership

- Economic empowerment and skills development for young women

- Action on ending violence against young women and girls

- Engaging boys and young men in gender equality

- Sustainable development agenda

- Leadership and Participation

- National Planning

- Violence against Women

- Access to Justice

- Regional and country offices

- Regional and Country Offices

- Liaison offices

- UN Women Global Innovation Coalition for Change

- Commission on the Status of Women

- Economic and Social Council

- General Assembly

- Security Council

- High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development

- Human Rights Council

- Climate change and the environment

- Other Intergovernmental Processes

- World Conferences on Women

- Global Coordination

- Regional and country coordination

- Promoting UN accountability

- Gender Mainstreaming

- Coordination resources

- System-wide strategy

- Focal Point for Women and Gender Focal Points

- Entity-specific implementation plans on gender parity

- Laws and policies

- Strategies and tools

- Reports and monitoring

- Training Centre services

- Publications

- Government partners

- National mechanisms

- Civil Society Advisory Groups

- Benefits of partnering with UN Women

- Business and philanthropic partners

- Goodwill Ambassadors

- National Committees

- UN Women Media Compact

- UN Women Alumni Association

- Editorial series

- Media contacts

- Annual report

- Progress of the world’s women

- SDG monitoring report

- World survey on the role of women in development

- Reprint permissions

- Secretariat

- 2023 sessions and other meetings

- 2022 sessions and other meetings

- 2021 sessions and other meetings

- 2020 sessions and other meetings

- 2019 sessions and other meetings

- 2018 sessions and other meetings

- 2017 sessions and other meetings

- 2016 sessions and other meetings

- 2015 sessions and other meetings

- Compendiums of decisions

- Reports of sessions

- Key Documents

- Brief history

- CSW snapshot

- Preparations

- Official Documents

- Official Meetings

- Side Events

- Session Outcomes

- CSW65 (2021)

- CSW64 / Beijing+25 (2020)

- CSW63 (2019)

- CSW62 (2018)

- CSW61 (2017)

- Member States

- Eligibility

- Registration

- Opportunities for NGOs to address the Commission

- Communications procedure

- Grant making

- Accompaniment and growth

- Results and impact

- Knowledge and learning

- Social innovation

- UN Trust Fund to End Violence against Women

- About Generation Equality

- Generation Equality Forum

- Action packs

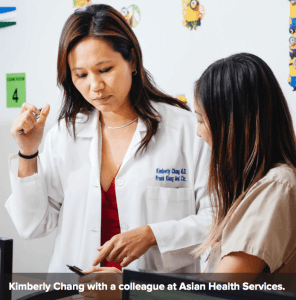

A Case of Human Trafficking

A disheartening encounter with a young patient convinced physician Kimberly Chang, MPH ’15, that medical professionals can play a key role in protecting victims of coerced sex and labor.

Kimberly Chang was fresh out of medical residency in 2003 when a 14-year-old girl stumbled into her exam room at Asian Health Services in Oakland, California. Reeking of marijuana, with bloodshot eyes and bruises all over her body, the girl asked to be checked for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).

Chang, MPH ’15, diagnosed several STDs in the teen—and, with a sinking realization, also determined that her patient was being forced into sex, addicted to drugs, and getting beaten up regularly. Over the next few years, Chang would see the scenario repeated again and again among her mostly poor, immigrant patients.

Yet she continued to view her job as primarily treating their medical problems—until the day a young teen girl arrived at the clinic, acutely ill. She had a high fever, a racing heart rate, and a rash all over her body. She’d lost 30 pounds in three months. But she refused to go to the hospital because she feared she’d be arrested on a previous warrant for prostitution.

Chang spent the entire evening negotiating with her. The girl was willing to drive only with her “purchaser”—a man who bought unprotected sex from her three times a week. For two hours, Chang tried to persuade the man to drop the girl off at the emergency room. They never made it, and it took another day before Chang and her colleagues tracked down the girl through her MySpace page and community contacts. This time, Chang personally arranged for someone to drive her to the hospital, where she spent two months recovering.

“But guess what happened when she got out?” Chang asks, still incredulous. “She was sent to jail.” Although the teenager was essentially an abused child, the police and courts considered her a criminal. That 2008 crisis became the catalyst for all that followed in Chang’s career. She evolved from physician to physician-activist to—bolstered by her new master’s degree from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health—policy advocate. Today, she is propelled by a strong belief that human trafficking should not be a law enforcement but rather a public health issue.

TEACHING PATIENTS THEIR RIGHTS

Chang grew up in Honolulu, Hawaii, in an ethnically Chinese family. Only recently did she learn that her great-grandmother, born in Vietnam, was kidnapped by pirates and sold into slavery in Hong Kong before escaping and starting a family in Hawaii as a plantation worker. “Given the work that I’m doing now,” Chang observes, “I thought that was an interesting connection.”

As a young child, Chang would watch her mother, a speech pathologist, work with children with cerebral palsy. “That care and compassion made a big impact,” she says. At age 12, she set out to be a doctor, calculating to the exact year when she would begin her training as a physician and proceeding straight through college, medical school, and residency before landing at Asian Health Services as a family doctor.

Many of her teen patients came in high on drugs and physically battered. She learned to speak with them bluntly yet sympathetically, to identify who was being forced into sex, and to care for them without judgment. She also made a point of teaching them their rights. In the case of adult patients working as domestic help, for example, she’d explain: “It’s not OK for your employer to hold your passport and stop you from leaving the country.”

Chang was soon promoted to director of a satellite clinic of Asian Health Services. The site served 10 Asian refugee communities but had to turn down many more for lack of language abilities and staff. “It bothered me when I thought about who gets access and who doesn’t. Where is health equity in this?” she says. “I felt I needed to acquire the policy tools to be able to elevate the issues of immigrant and refugee health and of trafficking in the health care, community health, and public health arenas.”

That quest brought her to Harvard Chan through the Commonwealth Fund Mongan Fellowship in Minority Health Policy . There, Chang met people who, like her, were working for populations shut out of mainstream culture and medicine. Her driving goal: to turn human trafficking into a frontline health issue. “How could I make the health care system stronger, so that it could go toe-to-toe with the criminal justice system?” she recalls. “Harvard Chan has given me a platform to make practical changes and reach more patients—not just through my health center but through every health center that wants to take on this issue.”

Commonwealth Fellowship program director Joan Y. Reede, MPH ’90, SM ’92, notes that Chang stood out for her compassion, her creativity—and her impatience at the slow pace of change. “Kim is an extraordinary individual who does not recognize how extraordinary she is,” Reede says. “She hadn’t realized her full potential when she arrived, and over the course of the year she had an awakening that you can make a difference—not by aiming low, but by aiming high.”

Helping young people avoid the sex trade, or get out early, can slow the problem downstream. “By reducing the number of victims,” says Chang, “you can reduce the number of traffickers.”

At Commencement, Chang received the School’s Dr. Fang-Ching Sun Memorial Award for her commitment to vulnerable populations. According to Reede, “It comes out of a deep awareness of the responsibility that accompanies the title of physician—to take care of everyone—and an understanding that the system has that responsibility as well.”

LOOKING UPSTREAM

With MPH in hand, Chang is back at her clinic in Oakland, where she continues to see patients part time. In collaboration with the Association of Asian Pacific Community Health Organizations , she’s also putting into action a policy brief she wrote while at Harvard Chan for the Health Resources and Services Administration, part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). In line with that effort, she hopes to collaborate with HHS to create pilot models at federally qualified health centers for step-by-step protocols for trafficking victims, from outreach to long-term chronic care, providing the medical roadmap she wishes she’d had when starting out as a community doctor.

As befits a newly minted public health professional, Chang is also looking upstream at original causes. She believes the first step to stop trafficking at its source is to treat it as a disease. “I see this as community surveillance,” she says. “We talked to the Cambodian elders about this problem, and they started looking out and noticing that, oh, their daughters aren’t just going out and having fun. They’re coming home with bruises.”

Although Chang’s patients were typically trafficked by men outside the family—pimps and boyfriends, for example—it’s not uncommon for people to traffic their own family members for economic reasons. Targeting the poverty that leads these families to such desperate measures is critical, Chang says. So is persuading them to reassess what may have become commonplace—in the exam room, in schools, at community gatherings. “We need to change the social norm,” she says, “and redefine what communities consider acceptable.”

In the complex world of trafficking, a victim today may become a recruiter tomorrow. Chang contends that helping young people avoid the trade, or get out early, can slow the problem downstream. “By reducing the number of victims,” she says, “you can reduce the number of traffickers.”

On a more systemic level, Chang urges public health leaders to join initiatives against human trafficking. “At the moment, most of these are run by criminal justice,” she says. “There’s a scarcity of health care and public health in there.”

LIFE AFTER TRAFFICKING

Looking back at her most disturbing cases, Chang has seen that the right treatment and policies can change lives. The first 14-year-old girl who came in high and bruised? Chang treated her STDs, encouraged her to leave the sex trade, and wrote her a letter of support to get into a health assistant training program. Now in her twenties and in a stable relationship, the young woman has a new outlook on life. “Her main challenge today,” notes Chang, “is college algebra.”

But not all stories from the clinic have happy endings. Chang lost touch with the 15-year-old patient who went to jail for prostitution. She heard the girl became pregnant and was still engaged in sex work. Yet such setbacks don’t discourage Chang.

“I have the privilege of being asked the question, ‘How do you not get demoralized?’ My patients don’t have that privilege,” she explains. “I don’t get demoralized because I have the power to change things. If I don’t use that power, who will?”

Karen Brown is a public radio reporter and freelance writer based in Western Massachusetts who specializes in health and mental health issues.

Watch a video or listen to a podcast of Kimberly Chang and other Harvard Chan students.

News from the School

Bethany Kotlar, PhD '24, studies how children fare when they're born to incarcerated mothers

Soccer, truffles, and exclamation points: Dean Baccarelli shares his story

Health care transformation in Africa highlighted at conference

COVID, four years in

By Margaret Henderson

While human trafficking has existed for centuries, communities are paying new attention to the problem. Some high-profile cases — such as the massage parlor investigation in Jupiter, Florida, in March 2019 — have generated extensive media coverage about a specific type of trafficking. There have also been improvements in legislation that address associated crimes, public funding opportunities that focus community attention on improved interventions and response, and — perhaps most importantly — evolving cultural attitudes that are willing to name the illegal behaviors as unacceptable.

Human trafficking involves the use of force, fraud, or coercion to compel another person to perform labor or a sex act for the profit of a third person. Victims can be adults or children, foreign or domestic born. The trafficking can involve purely labor or purely commercial sex or can be a blend of both.

The forms and dynamics of trafficking can vary widely and typically take advantage of local community characteristics. A convention center or military base might generate a market for sex trafficking, for example, whereas seasonal farm work and restaurants might generate a market for labor trafficking (see sidebar, “Environmental Conditions That Enable Trafficking”).

Tracking Trends

The Polaris Project is affiliated with the National Human Trafficking Hotline. Using statistics from callers, the project identified 25 business models of human trafficking. 1 In research conducted in 2018 by the School of Government at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, focus groups of local government workers in the state reviewed the business models to assess which might be visible to staff of any department. 2 (See sidebar, “Business Models of Human Trafficking Most Visible to Local Government Staff.”)

This research illuminated the critical importance of training first responders and inspectors for any purpose—environmental health, code enforcement, fire codes, and so forth. But the focus groups also pointed out the importance of building awareness more broadly among staff who work in libraries, handle registration or licensing functions, manage water/sewer/solid waste/recycling, respond to parking violations or nuisance calls, or work in public waiting areas.

SIDEBAR: ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITIONS THAT ENABLE TRAFFICKING

The following are environmental conditions that enable sex or labor trafficking, either by generating a market for the act, amplifying a vulnerability, transporting victims, or facilitating contact with buyers.

- Tourist destinations

- Large public events

- Seasonal farm work

- Online advertising opportunities

- Highway rest stops

- Military bases

- International borders

- Colleges and universities

Building Awareness

Terra Greene, city manager of Lexington, North Carolina (pop. 20,000), attended a basic awareness training event hosted by the fire department that was open to all city and county staff. “One key note that was so disturbingly impactful for me to hear in the awareness training … human trafficking is incredibly profitable because the controller or profiteer can sell the same human being over and over again.”

For local governments, the default setting might be to assume that dealing with trafficking falls to law enforcement, social services, or possibly public health clinics. However, research, educational efforts, and real-life scenarios 3 together indicate that additional city and county departmental staff have the potential to identify and report the indicators of trafficking, to build community awareness, and to strengthen local systems of response and intervention.

Greene confirms the access city staff have to homes, businesses, and the community at large and goes on to acknowledge the discomfort they might have about reporting indicators of trafficking. “It is critical that public servants take their role one step further when it comes to overall public safety and speak up if they see something. That step can feel like it taps into tremendous inner courage because oftentimes it is innate behavior to mind your own business, especially when on private property.

Donald Duncan, city manager of Conover, North Carolina (pop. 8,000), began his process of strengthening local government response in a similar way, by immediately integrating the content of a “Human Trafficking 101” training event into the content of his public work.

“After sitting through the session, I began to realize how often we see signs of human trafficking, but do not realize it. It was sobering and admittedly depressing. I had been on the periphery of human trafficking and did not understand that until taking the initial training.”

He thought back to the time his wife, an elementary school teacher, suspected one of her students was being abused. Ultimately, it was discovered the child was being prostituted by her own family. While the situation was obviously harmful to the child, no one called it “human trafficking” at the time, but that is what it was.

SIDEBAR: BUSINESS MODELS OF HUMAN TRAFFICKING MOST VISIBLE TO LOCAL GOVERNMENT STAFF

Almost all of the 25 business models of trafficking identified by the Polaris Project can be visible to local government staff:

- Escort services

- Illicit massage, health and beauty businesses

- Outdoor solicitation

- Residential brothels

- Domestic workers

- Bars, strip clubs, and cantinas

- Traveling sales or clean-up crews

- Restaurants and food service sites

- Peddling and begging rings, fundraising sales

- Agriculture and animal husbandry

- Personal sexual servitude; forced marriages

- Health and beauty services

- Construction industry

- Hotels and hospitality industries

- Landscaping businesses

- Illicit activities operated by gangs and organized crime

- Forestry and logging

- Health-care settings

- Recreational facilities

The four business models of trafficking that are not likely to be seen by local government staff in the course of their regular duties are the production of pornography, commercial cleaning services operating at night, arts/entertainment functions, and remote, interactive, commercial sexual sites.

Taking Action

Conover allows for itinerant merchants to conduct door-to-door sales. After a rash of harassing salesmen, the city council directed Duncan to strengthen the policy governing such sales. “We now require these sales groups to present their identification and pay for a permit. The officers on duty run a quick search through National Crime Information Center (NCIC) to make sure there are no outstanding warrants or prior convictions of fraud or violent crime. After implementing this new procedure, one group came to the police department, and we noticed one person bringing in members of the sales crew, handing them their identification documents 4 as they approached. Staff never suspected trafficking until the group was gone.”

Moving forward, Duncan will promote one general and two specific initiatives. First, he decided to offer the basic training to all city staff as part of the safety training regimen and is working with an area service provider to arrange that training.

Second, he is building on a tradition of training staff to be aware of indicators of criminal activity. In the past, the city implemented Fleet Watch, an initiative of the NC Crime Watch program. “To support community policing, the police department-initiated training for sanitation, meter readers, code enforcement, and fire crews to recognize signs of crime and domestic abuse. The idea of broadening awareness to include indicators of human trafficking will not be a stretch,” said Duncan.

Third, Duncan will work with key city staff to consider trafficking through the lens of organized crime, using strategies that evolved from intelligence gathering methods used by the military in Iraq and Afghanistan. The logic underlying such strategies is that gangs represent domestic terrorism and organized crime.” Through peer pressure and forced initiations, they also act as human traffickers. The tactics used to identify foreign terrorists work just as well in North Carolina with NC GangNET 5 and other gang intervention models currently in use. With slight modifications these could all be applied to combat human trafficking.”

City Manager David Parrish, of Greensboro, North Carolina (pop. 287,000), learned human trafficking was allegedly taking place in the Gate City during a council meeting. One evening, a resident raised a concern, outlining what types of services were for sale at a local massage parlor. The resident referenced how the city had responsibilities for business licensing that should not enable associated illegal activity.

In response, Parrish immediately deployed city staff from police, engineering and inspections, and code enforcement to investigate the massage parlor to determine if illegal activity was happening on the premises. The investigation included a review of the licensing and on-site activity. The multidepartment team effort uncovered evidence confirming the owners were in violation of the law. Charges related to human trafficking were filed against them. Since then, police routinely follow up with code enforcement to make sure businesses are operating legally.

“We appreciate residents being vigilant and willing to say something when they suspect criminal activity is happening. This is an example where multiple city departments worked together, using existing resources, to address and resolve this incident of human trafficking,” said Parrish.

SIDEBAR: VULNERABILITIES = OPPORTUNITIES FOR TRAFFICKERS

In general, human traffickers look for points of weakness to exploit. These vulnerabilities can be social, political, financial, or situational, taking many different forms. Here are some examples:

- Family conflict/instability

- Financial stress

- Social isolation

- Homelessness

- Limited English proficiency

- Immigration status

- Unsafe community or living conditions

- Sexual orientation/gender identity

- Lack of transportation

- Rejection by family or community

- History of physical or sexual trauma

- Foster care placement; aging out of the child welfare system

- Political instability

- Cultural background

- Natural disasters

Key Strategies

Addressing the problem of human trafficking is not simple or easy. Here are some initial strategies to consider.

Build awareness of the indicators and basic dynamics of trafficking across all governmental departments, beyond law enforcement and social services. Suggestion: Invite area service providers to provide basic training, describe local resources for intervention, and begin to build relationships across organizational lines. Encourage self-education through online resources and state or national training opportunities. (See sidebar, “Online Resources for Local Governments.”)

- Develop protocols for reporting in dicators of potential trafficking. Debrief and adjust as needed, once reports are made. Suggestion: At a staff meeting, discuss and decide on the preferred options for reporting (e.g. , local law enforcement, local rapid response team, or the National Human Trafficking Hotline at 1-888-373-7888 or text 233733), as well as expectations for informing departmental supervisors, the city/county manager, or elected officials.

- If your community has a particular challenge with any of the environmental conditions that enable trafficking or any of the business models that traffickers employ, consider taking a focused approach. (See sidebars, “Environmental Conditions That Enable Trafficking” and “Business Models of Human Trafficking Most Visible to Local Government Staff.”) Suggestion: Convene a multi-departmental team to apply existing processes, policies, and procedures to the challenge that relates to trafficking, in order to develop strategies of prevention or intervention.

- If your community is working to address any wicked problem (e.g. , homelessness, food scarcity, substance abuse, success in school), know that you are also working to prevent trafficking. Suggestion: Take time out in those existing work groups to consider the issue through the lens of human trafficking. For example, is there a particular way that the local homeless population is being manipulated? (See sidebar, “Vulnerabilities = Opportunities for Traffickers.”)

SIDEBAR: ONLINE RESOURCES FOR LOCAL GOVERNMENTS*

- Public Management Bulletin #12: “Human Trafficking in North Carolina: Strategies for Local Government Officials.” This bulletin covers ways in which human trafficking can be viewed through the lens of local government. The bulletin begins with a discussion of the basics—what human trafficking is, how it operates, and where it tends to turn up—followed by an examination of human trafficking as a local government concern. The author concludes the bulletin by outlining six strategies that local government leaders can take to address human trafficking in their communities.

- Public Management Bulletin #15: “Exploring the Intersections between Local Governments and Human Trafficking: The Local Government Focus Group Project.” This bulletin focuses on the business models traffickers use to manage their human trafficking enterprises and reports on focus group discussions with local government officials to determine how greater awareness of these models and their various signs within the community might be incorporated into their daily work.

- Public Management Bulletin #16: “Labor Trafficking—What Local Governments Need to Know.” This bulletin focuses on what labor trafficking is and how it shows up in North Carolina.

* from the School of Government, UNC-Chapel Hill, available at www.sog.unc.edu.

While the concept of human trafficking is overwhelming to most of us, there are specific steps any community can take to begin to address the issue. Once local government staff members learn about the indicators of trafficking, they tend to respond in the same way as other professional groups: “We’ve been seeing the signs all along, but we didn’t know that it was trafficking.”

The responsibilities of local government staff put them in homes, businesses, and public spaces on a regular basis. They also tend to be people who care about, and are connected to, their communities. Given that trafficking often operates in plain sight, local government staff offer untapped potential for noticing its indicators.

As Terra Greene observes, “Human trafficking is a very real humanitarian issue, which requires acute awareness and courage to actively contribute to the solution.” Remember: Human traffickers only need local governments to do one thing—nothing. Hopefully, these examples and insights from local government managers in North Carolina can inspire other cities and counties to begin their own efforts to stop human trafficking.

1 “The Typology of Modern Slavery: Defining Sex and Labor Trafficking in the United States” at https://polarisproject.org/typology

2 For a discussion, see PMB No. 15, June 2018, “Exploring the Intersections Between Local Government and Human Trafficking: The Local Government Focus Group Project,” available at www.sog.unc.edu

3 Media reported that law enforcement used the observations of a health inspector to build the investigation in the Jupiter, Florida, illicit massage parlor case, in early 2019.

4 One indicator of trafficking is that a third party takes and controls access to the identification documents of victims. Traveling sales crews are a business model that traffickers employ.

5 https://www.ncdps.gov/Our-Organization/Law-Enforcement/State-Highway-Patrol/NC-GangNET NC GangNET is a database that has a web-based capability of allowing certified users to enter and/or view information on gang suspects and members that have been validated as such using standardized criteria.

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!

Tonya spent night after night in different hotel rooms, with different men, all at the command of someone she once trusted. She was held against her will, beaten and made to feel like she had no other option at the time, all by the man she thought she loved.

She felt she deserved it. Tonya felt she couldn’t escape. Afraid and confused, she thought the emotional and physical abuse she endured was her own doing.

Tonya (a pseudonym) was a victim of human trafficking. “He made me feel like I was doing it because I loved him, and in the end, we’d have a really good [financial] reward,” Tonya said.

When Tonya was 13, she met Eddie (a pseudonym) at the apartment she was living in with her mother in the Dallas, Texas, area. His estranged wife was the property manager. Tonya was classmates with Eddie’s stepdaughter, so the two would often see each other at the apartment and in the local grocery store. It was there that the two first exchanged numbers.

“It was a casual relationship at first. You could see there was a mutual connection. I thought he was cute,” Tonya recalled. “I could tell he was really flirtatious with me. We would talk and flirt a lot, but it was not much more than that until we met again when I was 15.”

Things began to change one night when Tonya ran into Eddie at a bar. The two reconnected, the flirting picked up where it left off and Tonya went home with Eddie that night. Tonya was a runaway at the time, so she eventually moved in with Eddie and the two began a relationship.

It was a “normal” arrangement at first. Tonya would cook, clean and look after Eddie’s kids from time to time. However, it was when the two were at a party filled with alcohol and drugs that the relationship took a turn.

“He approached me and told me in so many words, ‘I want you to have sex with this guy for money,’” Tonya said. “I was very uncomfortable and I kept saying no, I didn’t want to do it. He kept telling me, ‘If you love me, you’ll do this. It’s just one thing. Just try it.’”

After nearly 30 more minutes of constant pressure, Tonya agreed to have sex with the man. What she thought would be a one-time thing became an everyday routine for the next few weeks. Night after night and bar after bar, Tonya would go out with Eddie while he advertised her to potential “suitors.” Tonya thought she loved him. She felt she could deal with the physical toll the trafficking took on her body. It turned out that the hardest part to deal with was the emotional and psychological effects.

“Being able to sleep with that many people and live with myself and get up every day and keep doing it and just lying there being helpless was so hard,” Tonya said.

Help eventually came for Tonya in the form of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) Special Agent Keith Owens. The Grand Prairie, Texas police department had received a tip about Eddie’s crimes and passed the case on to HSI Dallas. Owens and his team took over, moved in and arrested Eddie.

Eddie pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 12 years in prison on May 29, 2015. During the sentencing hearing, Tonya had to testify. Having to hear and see the man who trafficked her was difficult, especially not knowing what the outcome would be and whether he would be convicted.

“Telling people publicly about what I’d been through made me feel more ashamed because I’d never told anyone or was open about it,” Tonya said. “Keith and [HSI Dallas special agent] Allison [Schaefer] were the only two people I’ve really told everything to.”

Tonya feels her life is a little better now. She doesn’t think or talk about what she’s been through and doesn’t want people to know that was once a part of her life. Her focus is on moving forward.

“I want to finish getting my GED and go to community college, take on journalism, go to college and study political science and pre-law,” she said. “I just want to live a normal life, accept my past and not run from it.”

Eventually, Tonya knows that she will have to talk about her experience again. If she has kids one day, she wants to be able to tell them what their mother went through. She wants them to know what to look out for and how to avoid going through something as awful as she did.

Until then, she passes along her words of encouragement to anyone who may be experiencing what she did. She wants any victims out there to know they are not alone.

“You’re worth something. You’re very important to someone,” Tonya said. “No matter what he says, it’s not true. You’re worth something.”

Part 1: The Beginning

It was just supposed to be something to make money, but it quickly turned into much more than she ever imagined. In part one, Tonya (a pseudonym) reveals how she initially became a victim of human trafficking.

Part 2: An Emotional Toll

Dealing with the physical toll the trafficking took on her body was “easy.” It turned out that the hardest part to deal with was the psychological effects. In part two, Tonya discusses the emotional toll of being a victim of human trafficking.

Part 3: A Painful Relief

Although she was ultimately able to “escape” from her trafficker, the experience of being a victim of human trafficking still haunted Tonya. In part three, she talks about the lingering pain that existed even after her ordeal was over.

Part 4: You Deserved It

Like many victims of human trafficking, Tonya felt that she deserved it. In part four, Tonya explains how she and many victims like her feel that way.

Part 5: Knowing What To Look For

What can be done to prevent human trafficking? How can potential victims protect themselves from perpetrators? In the final segment, Tonya discusses what potential victims should look out for, and what law enforcement officials need to do to combat human trafficking.

National Human Trafficking and Slavery Prevention Month

The month of January has been designated by the White House as National Human Trafficking and Slavery Prevention Month. Millions of women, men and children around the world are subjected to forced labor, domestic servitude, or the sex trade at the hands of human traffickers. A form of modern-day slavery, the inhumane practice of human trafficking takes place here in the United States as well.

Human trafficking is one of the most heinous crimes investigated by ICE. In its worst manifestation, human trafficking is akin to modern-day slavery. They are forced into prostitution, involuntary labor and other forms of servitude to repay debts – often incurred during entry into the United States.

ICE recognizes that severe consequences of human trafficking continue even after the perpetrators have been arrested and held accountable. ICE’s Victim Assistance Program helps coordinate services to help human trafficking victims, such as crisis intervention, counseling and emotional support.

In their own words

Disclaimer: The following passages contain first-person accounts from victims of sex trafficking. Names have been altered to protect their identities. Homeland Security Investigations worked in collaboration with the FBI on their case.

“I was 17 around when I met ‘Robert.’ It started off with me and my friend meeting him for social purposes. It just went on for about nine months and we were living in different hotels the entire time and I don’t even remember how many men there were. I was a runaway and wasn’t living anywhere stable, so since I was underage most of the time, I sort of needed him in order to get hotels and move around.

I had already been a prostitute since I was 15 and I think I just didn’t even know what was right or wrong and how I should be treated. Towards the end, he held me against my will in a hostage situation and forced me to prostitute and took all the money and just beat me severely.

The last time I saw him, he was just beating me until he was absolutely tired. I was covered in bruises, my face was completely disfigured and it’s causing me issue with my back to this day because of the way he was beating me and torturing me. That was probably the worst. There was a client in the room and he was having an issue with something I couldn’t do because I was all beat up. I didn’t want to do it anymore. I didn’t want to do anything. He wanted the money back. When Robert and him were talking I ran out of the room and somehow was able to run faster than him.

I didn’t tell anyone. I kept it to myself until I got a call from the FBI that he’d been arrested for something else and asked would I talk. Having to go face everything and realize how serious everything was. For the longest time I didn’t even think it was that serious.

At the trial, it felt empowering to look at him the entire time. I’m sure it drove him crazy. He can never touch me but he had to look at me and listen and it made me feel good.

I had to learn that if I don’t at least have some kind of love and value for myself, no one ever will. My advice to other girls would be to let people help you. It’s not your fault and that you didn’t deserve it. It’s OK to be hurt about it because a lot of people will act like it never happened, because that’s what I was going to do too.

– “Laura” 21

“I was 15 at the time and was a runaway. ‘Tom’ wanted to be a pimp, so I would be in his room in his apartment and he would not let me go out for anything. He tried to intimidate me by threatening to beat me up if I tried to leave. I was scared of him so I wouldn’t leave. He would drop me off at a hotel while he went to work.

It lasted from March until June or July. Sometimes it would be every day, sometimes he would say, ‘not today, but tomorrow.’ Out of the week, maybe 4-5 times a week, I was with different men.

I just felt like that it was my fault and I deserved it and nobody would ever believe me or try to help me, so I just let them control how I thought about myself. They were always verbally abusive and putting you down and it got to the point that I actually started believing it. Just letting someone control your own freedom take over just what you do. I couldn’t leave the room. It was like ‘wow, I’m letting someone make me feel so scared.’

I never called the police because I felt it was my fault. I felt at the time like I had to stay. One day the FBI ended up coming to my house and contacted me because my name came up in their investigation.

You have to know your self-worth. It’s OK to ask for help. They don’t know they are a victim. They feel like it’s their fault. We are victims. You can have the worst past, but that doesn’t mean you can’t have a successful future.”

– “April” 18

- Information Library

- Contact ICE

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Migr Health

Human trafficking and violence: Findings from the largest global dataset of trafficking survivors

Heidi stöckl.

a The Institute for Medical Information Processing, Biometry, and Epidemiology, Medical Faculty, Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich, Germany

Camilla Fabbri

b Gender Violence & Health Centre, Department of Global Health and Development, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Northern Ireland, United Kingdom

c Migrant Protection and Assistance Division International Organization for Migration, Geneva, Switzerland

Claire Galez-Davis

Naomi grant.

d The Freedom Fund, Northern Ireland, United Kingdom

e Institute for Global Health, University College London, Northern Ireland, United Kingdom

Cathy Zimmerman

Human trafficking is a recognized human rights violation, and a public health and global development issue. Violence is often a hallmark of human trafficking. This study aims to describe documented cases of violence amongst persons identified as victims of trafficking, examine associated factors throughout the trafficking cycle and explore prevalence of abuse in different labour sectors.

Methods and findings

The IOM Victim of Trafficking Database (VoTD) is the largest database on human trafficking worldwide. This database is actively used across all IOM regional and country missions as a standardized anti-trafficking case-management tool. This analysis utilized the cases of 10,369 trafficked victims in the VoTD who had information on violence.

The prevalence of reported violence during human trafficking included: 54% physical and/or sexual violence; 50% physical violence; and 15% sexual violence, with 25% of women reporting sexual violence. Experiences of physical and sexual violence amongst trafficked victims were significantly higher amongst women and girls (AOR 2.48 (CI: 2.01,3.06)), individuals in sexual exploitation (AOR 2.08 (CI: 1.22,3.54)) and those experiencing other forms of abuse and deprivation, such as threats (AOR 2.89 (CI: 2.10,3.98)) and forced use of alcohol and drugs (AOR 2.37 (CI: 1.08,5.21)). Abuse was significantly lower amongst individuals trafficked internationally (AOR 0.36 (CI: 0.19,0.68)) and those using forged documents (AOR 0.64 (CI: 0.44,0.93)). Violence was frequently associated with trafficking into manufacturing, agriculture and begging (> 55%).

Conclusions

An analysis of the world's largest data set on trafficking victims indicates that violence is indeed prevalent and gendered. While these results show that trafficking-related violence is common, findings suggest there are patterns of violence, which highlights that post-trafficking services must address the specific support needs of different survivors.

1. Introduction

Human trafficking is a recognized human rights violation, and a public health and global development issue. Target 8.7 of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals calls for states to take immediate and effective measures to eradicate trafficking, forced labour and modern slavery ( Griggs et al., 2013 ).

Human trafficking has been defined by the United Nations’ Palermo Protocol as a process that involves the recruitment and movement of people-by force, coercion, or deception—for the purpose of exploitation ( United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2000 ).

Estimating the scale of human trafficking is difficult, due to the hidden nature of this crime and challenges associated with the definition. As a result, available estimates are contested ( Jahic and Finckenauer, 2005 ). According to data on identified victims of trafficking from the Counter-Trafficking Data Collaborative ( International Organization for Migration 2019 ), nearly half of the victims report being trafficked for the purpose of sexual exploitation, while 39% report forced labour, and the most common sectors of work included: domestic work (30%), construction (16%), agriculture (10%) and manufacturing (9%). Women and girls account for almost all those trafficked for commercial sexual exploitation, and 71% of those report violence ( International Organization for Migration 2019 ; International Labour Organization 2017 ; UNODC 2018 ).

Current data confirm that prevalence of violence is high amongst survivors, although few studies have investigated causal mechanisms related to violence in labour and sexual exploitation ( Kiss et al., 2015 ; Oram et al., 2012 ; Stöckl et al., 2017 ; Ottisova et al., 2016 ). Victims often report experiences of emotional, physical and sexual abuse throughout the various stages of the human trafficking cycle, from recruitment through travel and destination points, to release and reintegration ( Ottisova et al., 2016 ). Currently, evidence is scarce on the patterns of violence across different types of trafficking, despite its importance for more tailored assistance to survivors once they are in a position to receive post-trafficking support.

This study aims to close this evidence gap by describing documented cases of violence amongst trafficking survivors and describe associated factors, drawing on the largest global database to date, the IOM's Victim of Trafficking Database (VoTD).

2.1. Data source

The IOM VoTD is the largest database on human trafficking worldwide. Actively used across all IOM regional and country missions, VoTD is a standardized anti-trafficking case-management tool that monitors assistance for victims of trafficking. In certain contexts, IOM identifies victims at transit centres or following their escape, while in other settings IOM mainly provides immediate assistance following referral by another organization or long-term reintegration assistance. This routinely collected data includes information on various aspects of victims’ experiences, including background characteristics, entry into the trafficking process, movement within and across borders, sectors of exploitation, experiences of abuse, and activities or work at destination.

The primary purpose of IOM's VoTD is to support assistance to trafficked victims, not to collect survey data. It does not represent a standardized survey tool or research programme, and therefore, the quality and completeness of the data vary substantially between registered individuals. IOM case workers often enter data retrospectively and its quality may therefore be affected by large caseloads on staff working with limited resources. In addition, the VoTD sample may be biased by the regional distribution of IOM's missions and by the local focus on certain types of trafficking. For example, in the past, women were a near-exclusive target of IOM's assistance programs due to a focus on sexual exploitation. However, over time, the identification of trafficking victims has increasingly included individuals subjected to forced labour. Nevertheless, in the countries where IOM provides direct assistance to victims of trafficking, VoTD data are broadly representative of the identified victim population in that country and are still the most representative data with the widest global coverage on human trafficking.

Between 2002 and mid-2018, the VoTD registered 49,032 victims of trafficking, with nearly complete records for 26,067 records which provide information on whether individuals reported being exploited, with exploitation other than sexual and labour exploitation, such as organ trafficking or forced marriage accounting for less than five percent of the overall dataset. A bivariate analysis to identify patterns in the distribution of missing data found that missing values spanned across all variables of the data and no specific pattern regarding countries of exploitation or origin emerged that could explain the source of missing data.

2.2. Theory

This study relied on an adapted version of the Zimmerman et al. (2011) theoretical framework on human trafficking and health that comprises four basic stages: recruitment; travel and transit; exploitation; and the reintegration or integration stages; with sub-stages for some trafficked people who become caught up in detention or re-trafficking stages. The modified framework in Fig. 1 displays the three stages of the human trafficking process: recruitment, travel and transit and exploitation and displays the factors associated with experiences of violence during the trafficking process.

Stages of human trafficking adapted from Zimmerman et al. (2011) , incorporating variable coding.

2.3. Measures

The VoTD dataset includes survivors’ responses about whether they experienced physical or sexual violence during any stage of the trafficking process. Information available on trafficked persons’ pre-departure characteristics, risk factors at transit and exploitation stage are outlined in Fig. 1 with their respective coding. Reports on exploitation only include the last form of exploitation a victim of trafficking experienced. It is however possible to report more than one type of exploitation for the most recent situation.

The research team made a substantial effort to code and clean the data, working closely with IOM's data management team. IOM's database refers to the VoTD cases as ‘victims’ as IOM caseworkers follow the Palermo Protocol in their determination and this is the language of the Protocol, recognising the debates around the terminology victims versus survivors ( International Organization for Migration 2014 ). The secondary data analysis of the IOM VoTD data received ethical approval from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine ethical review board.

2.4. Data analysis

To estimate the prevalence of physical or sexual violence or both, as reported by trafficked victims in the VoTD, the analysis was restricted to the 10,369 victims with data available on experiences of physical and/or sexual violence. In total, 94 countries of exploitation were reported, covering the whole globe, including high-, middle- and low-income countries. Descriptive statistics highlight the characteristics of trafficked victims in total and by gender. Associations with physical and/or sexual violence have been calculated using unadjusted odds ratios. Only variables with a significant association with reports of physical and/or sexual violence in the unadjusted odds ratios were included into a staged logistic regression model. The staged logistic regression model aimed to show whether characteristics at pre-departure only or pre-departure and transit remain significantly associated with experiences of physical and/or sexual violence during human trafficking. A separate bivariate analysis was conducted between reported experiences of violence and sectors of exploitation due to the low number of responses for sectors of exploitation. In both the bivariate and multivariate logistic regressions, a p-value below 0.05 is taken to indicate significance.

Of the 10,369 trafficked victims included in this analysis, 89% were adults, of whom 54% were female. The prevalence of reported violence during human trafficking is high: 54% reported physical and/or sexual violence, 50% reported physical violence, and 15% sexual violence. Table 1 shows that more female victims report physical (54% versus 45%) and sexual (25% versus 2%) violence than men, both overall and amongst minors. amongst minors, 52% of girls reported physical violence and 27% sexual violence, compared to 39% and 8%, respectively amongst boys.

Prevalence of violence amongst victims of exploitation.

Pre-departure characteristics, displayed in Table 2 , show that most trafficked persons were in their twenties and thirties, and 17% were minors. amongst all VoTD cases, 75% self-identified as poor before their trafficking experience and 16% as very poor. Records show that 39% were married before they were trafficked. Of the total sample, 40% had achieved a secondary education. The majority reported that they were recruited into the trafficking process (79%), crossed an international border (92%) and were trafficked with others (75%). Forged documents were used in the trafficking process by 10% of trafficked persons. Most victims reported forced labour, 56% of whom were male. Of the 33% who were trafficked into sexual exploitation, 98% were female. Six percent reported they were trafficked into both labour and sexual exploitation. Victims reported a variety of abuses while trafficked, with 60% indicating they were subjected to threats against themselves or their family, 79% were deceived, 76% were denied movement, food or medical attention, 4% were given alcohol and/or drugs, 60% had documents confiscated and 35% reported situations of debt bondage.

Characteristics of trafficked persons at different stages of the trafficking stages for victims.

Exponentiated coefficients; 95% confidence intervals in brackets

Physical and/or sexual violence was significantly associated with being female, young age and self-reported high socio-economic status. More specifically, individuals between ages 18 and 24 are significantly more likely to report violence than those aged 25 to 34 and individuals aged 35 to 49 are less likely to report violence than those aged 25 to 34. Victims reporting their socio-economic status as well-off compared to poor before departure, were significantly more likely to report abuse during their trafficking experience. Crossing one border and using forged documents were all significantly associated with fewer reports of violence during the trafficking experience, while being in sexual exploitation and reporting any other forms of control or abuse during the exploitation stage increased the likelihood of violence reports.

Considering all pre-departure characteristics together, controlling for each other, being female and higher socio-economic status remained significantly associated with reports of physical and/or sexual violence (Model 1, Table 3 ), although only being female remained significant once transit and exploitation factors were taken into account. Controlling for other factors at the transit and exploitation stage, using forged documents remained significantly associated with fewer reports of violence as did most forms of abuses at the exploitation stage such as threats and being forced to take drugs and alcohol. Being in sexual exploitation or both sexual and labour exploitation versus labour alone also remained significant.

Association between trafficking characteristics and physical and/or sexual violence.

Exponentiated coefficients; 95% confidence intervals in brackets. * p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01 *** p < 0.001.

Availability of data on sectors of exploitation was limited. The separate analysis on the prevalence of physical and/or sexual violence in Table 4 displays high reports of violence from those trafficked into sexual exploitation, domestic work, manufacturing, agriculture and begging. Sexual violence was most often reported by victims trafficked into domestic work and the hospitality sector.

Prevalence of violence amongst victims of exploitation by activity sector.

“The opinions expressed in the article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries.”

4. Discussion

Our analysis of the world's largest trafficking victim data set indicates that physical and sexual violence is indeed prevalent in cases of human trafficking, as 52% of the trafficking cases included reports of physical and/or sexual violence. It is noteworthy that nearly half (48%) of survivors did not report violence, indicating that human trafficking does not necessariliy have to involve physical or sexual violence. It is important to recall that 60% of survivors reported being subjected to threats to themselves or their family, a potential explanation for the lack of reports of phyiscal and/or sexual violence. Our analyses also suggest that trafficking-related violence is gendered, as higher levels of abuse were reported by female survivors and in sectors in which women and girls are commonly exploited: sex work and domestic work. It is also noteworthy that sexual violence is an issue amongst trafficked men below the age of 18, indicating the importance of investigating human trafficking by both gender and age and by sector of exploitation.

The prevalence of physical and/or sexual violence found in this study corresponds with the prevalence range reported in a 2016 systematic review, which found rates between 12% to 96% ( Oram et al., 2012 ) and in Kiss et al's 2014 three-country survey of male, female and child trafficking survivors in post-trafficking services in the Mekong. In Kiss et al., 48% reported physical and/or sexual violence, with women reporting higher rates of sexual violence than men ( Kiss et al., 2015 ).

Findings also indicated several contradictions related to common generalisations related to vulnerability to trafficking, which often suggest that the poorest and least educated are at greatest risk of trafficking ( Passos et al., 2020 ). However, our analysis indicated that 40% of those who were trafficked had a secondary education and only 16% self-identified as very poor. Interestingly, when considering who was most at risk of abuse during trafficking, victims who were younger, between ages 18–24, seemed to experience higher levels of violence, perhaps indicating that those who were more mature were more compliant.

Our study also offers new insights about violence that occurs before individuals arrive at the destination of exploitation. Our study highlights that physical or sexual violence is also associated with factors at the recruitment and transit stage of the trafficking process, such as socio-economic status, crossing international borders and the use of forged documents. The latter contradicts current assumptions that are applied in trafficking awareness and training activities, which warn prospective migrants about international trafficking and against the use of forged documents ( Kiss et al., 2019 ). There are a number of possible explanations for this finding on forged documents. First, it is possible that having used forged documents gives traffickers the ability to threaten their victims with arrest or imprisonment because of their illegal status versus using physical abuse. The study found that internal trafficking was associated with a higher prevalence of violence. To interpret this, it is necessary to consider the general population or work-related prevalence of violence in countries from where the victims originate. If their countries of origin have higher levels of violence, this may make individuals less likely to report what they might consider to be minor workplace abuses ( Paasche et al., 2018 ). Similarly, violence in sex work and domestic work may have been related to socially normative abuse patterns and general prevalence of violence in these sectors and locations to which individuals were trafficked ( Kaur-Gill and Dutta, 2020 ). For abuse in situations of commercial sexual exploitation, a sector in which violence was reportedly most prevalent ( Platt et al., 2018 ), victims were likely to have been subjected to abuses by traffickers (e.g., pimps, managers, brothel owners) and clients at levels relative to general levels of abuse in that sector in that location. Likewise, women trafficked into domestic work, would have been exposed to violence from members of the household, a behaviour that is rarely condemned or punished in countries where trafficking into domestic work is common.

It is also possible that the levels of violence experienced by trafficked persons are proportional to the degree of control the exploiter feels he needs to exert over the victim. In that sense, trafficking victims who have more resources or capabilities to leave an exploitative situation may be the ones who experience higher levels of violence. For example, people with greater economic resources may have a greater ability to leave and may also have a social network that can support their exit process. Sexual exploitation may take a higher degree of coercion over victims, which would make threats and violence a useful tactic to keep them in the situation.

The VoTD is a unique dataset on human trafficking. However, it is useful to recognise that the VoTD is a case-management database and not systematically collected survey data. Data is limited to single-item assessments rather than validated instruments to capture complex situations and experiences and often entered retrospectively by caseworkers. For example, socio-economic background was self-assessed through four options only and recruitment through a single question. It is for this reasons that we did not include emotional abuse into our measurement of violence – given the lack of internationally agreed definitions of emotional abuse, we could not be certain that case workers recognize and enter all experiences of emotional abuse uniformly across the globe. Furthermore, the VoTD is cross-sectional in nature and does not allow to infer causality with respect to the factors associated with experiences of violence during the trafficking process. The VoTD is not representative of the overall population of trafficking victims, as it only captures individuals who have been identified as trafficked and who were in contact with post-trafficking services.

Despite these limitations, the analysis highlights the importance of large-scale administrative datasets in future international human trafficking research to complement in-depth qualitative studies. Our analysis suggests the urgent need for clearer and more consistent use of definitions, tools, and measures in human trafficking research, particularly related to socio-economic background, what is meant by ‘recruitment’ and ‘emotional abuse’. In particular, there is a need for international standards and guidance for recording and processing administrative data on human trafficking for research purposes. Prospective donors must also recognize that record-keeping is part of care cost, and support it through grant-making. This will allow frontline organizations to invest in information management systems, staff training, and record keeping policies and protocols. If frontline agencies are to provide data for research purposes, beyond those which are necessary for delivering protection services for victims, additional resources should be considered.

Our study reiterates the importance of psychological outcomes resulting from violence in cases of human trafficking, which has been identified in many other site-specific studies ( Ottisova et al., 2016 ). Yet, despite these common findings, and the world's commitment to eradicate human trafficking in the Sustainable Development Goal 8.7, to date, there has been extremely little evidence to identify what types of post-trafficking support works for whom in which settings. For instance, there have been few robust experimental studies to determine what helps different individuals in different contexts grapple with the psychological aftermath of human trafficking, even amidst growing number of post-trafficking reintegration programs and policies ( Okech et al., 2018 ; Rafferty, 2021 ). Given the increasing amount of case data from many programs working with survivors, organisations will have to produce more systematically collected case data to ensure findings are relevant and useful for future post-trafficking psychological support for distress and disorders, such as PTSD and depression.

Furthermore, the data indicate that abuses may occur throughout the trafficking cycle, which suggests that victim-sensitive policy responses to human trafficking are required at places of origin, transit and, particularly at destination, when different forms of violence often go undetected. Our findings also underline the need for post-trafficking policies and services that recognise the variation in trafficking experiences, particularly the health implications of abuse for many survivors. Ultimately, because of the global magnitude of human trafficking and the prevalence of abuse in cases of trafficking, human trafficking needs to be treated as a public health concern ( Kiss and Zimmerman, 2019 ). Moreover, because survivors’ experiences of violence varied amongst men, women and children and across settings, it will be important to design services that meet individuals’ varying needs, designing context specific interventions ( Kiss and Zimmerman, 2019 ; Greenbaum et al., 2017 ).

5. Conclusion

This study offers substantial new insights on the patterns of physical and/or sexual violence amongst trafficking survivors. By highlighting the linkages between violence and associated factors at different stages of the trafficking process, our findings emphasise the importance of understanding the entire human trafficking process so that intervention planning can more accurately assess opportunities to prevent trafficking-related harm, improve assessments of survivor service needs, and increase well-targeted survivor-centred care. Ultimately, while these results suggest patterns can be observed, they also show that trafficking is a wide-ranging and far-reaching crime that requires responses that are well-developed based on individuals’ different experiences.

The study was funded by a Freedom Fund grant to the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and the International Organization for Migration.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

- Griggs D., et al. Policy: sustainable development goals for people and planet. Nature. 2013; 495 (7441):305. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- UN Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2000. United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime andthe Protocols Thereto, in https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/organized-crime/intro/UNTOC.html . New York. Accessed 01.04.2019.

- Jahic G., Finckenauer J.O. Representations and misrepresentations of human trafficking. Trends Organ. Crime. 2005; 8 (3):24–40. [ Google Scholar ]

- International Organization for Migration. Counter Trafficking Data Collaborative. 2019, in https://www.ctdatacollaborative.org/ . Geneva. Accessed 01.10.2019.

- International Labour Office . Global estimates of modern slavery: Forced labour and forced marriage. ILO; Geneva: 2017. [ Google Scholar ]

- UNODC . UNODC; Vienna: 2018. The Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2018. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kiss L., et al. Health of men, women, and children in post-trafficking services in Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam: an observational cross-sectional study. Lancet Glob. Health. 2015; 3 (3):e154–e161. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Oram S., et al. Prevalence and risk of violence and the physical, mental, and sexual health problems associated with human trafficking: systematic review. PLoS Med. 2012; 9 (5) [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stöckl H., et al. Trafficking of Vietnamese women and girls for marriage in China. Glob. Health Res. Policy. 2017; 2 (1):28. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ottisova L., et al. Prevalence and risk of violence and the mental, physical and sexual health problems associated with human trafficking: an updated systematic review. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2016; 25 (4):317–341. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zimmerman C., Hossain M., Watts C. Human trafficking and health: a conceptual model to inform policy, intervention and research. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011; 73 (2):327–335. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- International Organization for Migration . IOM; Geneva: 2014. Accessing IOM Trafficked Migrants Assistance Database (TMAD) Information for Researchers and Practitioners. [ Google Scholar ]

- Passos T.S., et al. Profile of reported trafficking in persons in brazil between 2009 and 2017. J. Interpers. Violence. 2020 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kiss L., et al. SWiFT Research report. London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine; London: 2019. South Asia Work in Freedom Three-Country evaluation: A theory-Based Intervention Evaluation to Promote Safer Migration of Women and Girls in Nepal, India and Bangladesh. [ Google Scholar ]