Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8.1 What Is Political Participation?

Learning objectives.

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- What are the ways in which Americans participate in politics?

- What factors influence voter turnout in elections?

- How do Americans participate in groups?

Americans have many options for taking part in politics, including voting, contacting public officials, campaigning, running for and holding office, protesting, and volunteering. Voting is the most prominent form of political participation. Voter registration and turnout is influenced by legal and structural factors, voter qualifications, the type of election, and voters’ enthusiasm about a particular campaign.

Types of Political Participation

Political participation is action that influences the distribution of social goods and values (Rosenstone & Hansen, 1993). People can vote for representatives, who make policies that will determine how much they have to pay in taxes and who will benefit from social programs. They can take part in organizations that work to directly influence policies made by government officials. They can communicate their interests, preferences, and needs to government by engaging in public debate (Verba, Schlozman, & Brady, 1995). Such political activities can support government officials, institutions, and policies, or aim to change them.

Far more people participate in politics by voting than by any other means. Yet there are many other ways to take part in politics that involve varying amounts of skill, time, and resources. People can work in an election campaign, contact public officials, circulate a petition, join a political organization, and donate money to a candidate or a cause. Serving on a local governing or school board, volunteering in the community, and running for office are forms of participation that require significant time and energy. Organizing a demonstration, protesting, and even rioting are other forms of participation (Milbrath & Goel, 1977).

People also can take part in support activities , more passive forms of political involvement. They may attend concerts or participate in sporting events associated with causes, such as the “Race for the Cure” for breast cancer. These events are designed to raise money and awareness of societal problems, such as poverty and health care. However, most participants are not activists for these causes. Support activities can lead to active participation, as people learn about issues through these events and decide to become involved.

People take part in support activities on behalf of a cause, which can lead to greater involvement.

Midwestnerd – Jingle Bell 5K run – CC BY 2.0.

People also can engage in symbolic participation , routine or habitual acts that show support for the political system. People salute the flag and recite the pledge of allegiance at the beginning of a school day, and they sing the national anthem at sporting events. Symbolic acts are not always supportive of the political system. Some people may refuse to say the pledge of allegiance to express their dissatisfaction with government. Citizens can show their unhappiness with leadership choices by the symbolic act of not voting.

For many people, voting is the primary means of taking part in politics. A unique and special political act, voting allows for the views of more people to be represented than any other activity. Every citizen gets one vote that counts equally. Over 90 percent of Americans agree with the principle that citizens have a duty to vote (Flanigan & Zingale, 1999). Still, many people do not vote regularly.

Voter Qualifications

Registered voters meet eligibility requirements and have filed the necessary paperwork that permits them to vote in a given locality. In addition to the requirement that voters must be eighteen years of age, states can enforce residency requirements that mandate the number of years a person must live in a place before being eligible to vote. A large majority of people who have registered to vote participate in presidential elections.

The composition of the electorate has changed radically throughout American history. The pool of eligible voters has expanded from primarily white, male property owners at the founding to include black men after the Civil War, women after 1920, and eighteen- to twenty-year-olds after 1971. The eligible electorate in the 1800s, when voter turnout consistently exceeded 70 percent, was far different than the diverse pool of eligible voters today.

Barriers to Voting

Social, cultural, and economic factors can keep people from voting. Some barriers to voting are informal. The United States holds a large number of elections, and each is governed by specific rules and schedules. With so many elections, people can become overwhelmed, confused, or just plain tired of voting.

Other barriers are structural. Voter registration laws were implemented in the 1860s by states and big cities to ensure that only citizens who met legal requirements could vote. Residency requirements limited access to registration offices. Closing voting rosters weeks or months in advance of elections effectively disenfranchised voters. Over time, residency requirements were relaxed. Beginning in the 1980s, some states, including Maine, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, made it possible for people to register on Election Day. Turnout in states that have Election Day registration averages ten points higher than in the rest of the country (Wolfinger & Rosenstone, 1980).

The United States is one of the few democracies that requires citizens to register themselves rather than having the government take responsibility for automatically registering them. Significant steps have been taken to make registration easier. In 1993, Congress passed the National Voter Registration Act , also known as the “motor voter” law, allowing citizens to register at motor vehicle and social service offices. “Motor voter’s” success in increasing the ranks of registered voters differs by state depending on how well the program is publicized and executed.

Organizations conducting voter registration drives register as many voters as government voter registration sites.

Rakka – ”twin peaks” and voter registration – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Voter registration also has been assisted by online registration. In most cases, individuals must download the form, sign it, and mail it in. Rock the Vote (RTV), a nonpartisan youth mobilization organization, established the first online voter registration initiative in 1992 with official backing from the Congressional Internet Caucus. RTV registered over 2 million new voters in 1992, 80 percent of whom cast a ballot, and signed up over 2.5 million voters in 2008. [1] Following the 2008 election, RTV lobbied the Obama administration to institute fully automated online voter registration nationally.

Disenfranchisement of Felons

In all states except Maine, Vermont, and Massachusetts, inmates serving time for committing felonies lose their right to vote. At least ten states prohibit former felons from voting even after they have served their time. States argue that their legal authority to deny convicted felons voting rights derives from the Fourteenth Amendment, which stipulates that voting rights of individuals guilty of “participation in rebellion, or other crime” can be denied. This practice excludes almost 4 million people from the voting rolls (Human Rights Watch and the Sentencing Project, 2000).

Opinions are divided on this issue. Some people believe that individuals who have committed a serious crime should be deprived of the privileges enjoyed by law-abiding people. Others contend that the integrity of the democratic process is at stake and that individuals should not be denied a fundamental right once they have served their time.

Voter turnout depends on the type of election. A large number of elections are held in the United States every year, including local elections, elections for county and statewide offices, primaries, and general elections. Only a small number of people, generally under one-quarter of those eligible, participate in local, county, and state elections. Midterm elections, in which members of Congress run for office in nonpresidential-election years, normally draw about one-third of eligible voters (Rosenstone & Hansen, 1993). Voter turnout in presidential elections is generally higher than for lower-level contests; usually more than half the eligible voters cast a ballot.

Much is made about low levels of voter turnout for presidential elections in the current era. However, there have not been great fluctuations in turnout since the institution of universal suffrage in 1920. Forty-nine percent of the voting-age public cast a ballot in the 1924 presidential contest, the same percentage as in 1996. Turnout in presidential elections in the 1960s was over 60 percent. More voters were mobilized during this period of political upheaval in which people focused on issues of race relations, social welfare, and the Vietnam War (Piven & Cloward, 2000). Turnout was lower in the 1980s and 1990s, when the political climate was less tumultuous. There has been a steady increase in turnout since the 2000 presidential election, in which 51 percent of the voting-age public cast a ballot. Turnout was 55 percent in 2004 and 57 percent in 2008, when 132,618,580 people went to the polls (McDonald).

Turnout varies significantly across localities. Some regions have an established culture of political participation. Local elections in small towns in New England draw up to 80 percent of qualified voters. Over 70 percent of Minnesota voters cast ballots in the 2008 presidential election compared with 51 percent in Hawaii and West Virginia (McDonald).

Turnout figures can be skewed by undercounting the vote. This problem gained attention during the 2000 election. The contested vote in the Florida presidential race resulted in a recount in several counties. Ballots can be invalidated if they are not properly marked by voters or are not read by antiquated voting machines. Political scientists have determined that presidential election turnout is underestimated on average by 4 percent, which translates into hundreds of thousands of votes (Flanigan & Zingale, 1999).

Voters in midterm elections choose all the members of the US House of Representatives and one-third of the Senate, along with office holders at the state and local levels. Voter turnout levels have hovered around 40 percent in the past three midterm elections. Turnout for the 2010 midterm election was 41.6 percent, compared with 41.4 percent in 2006 and 40.5 percent in 2002 (McDonald). Young voters are less likely to turn out in midterm elections than older citizens. In 2010, only about 23 percent of eligible eighteen- to twenty-nine-year-olds cast a ballot (Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement). The United States Election Project provides information about voter turnout in presidential campaigns.

Democratic Participation

People have many options for engaging in politics. People can act alone by writing letters to members of Congress or staging acts of civil disobedience . Some political activities, such as boycotts and protest movements, involve many people working together to attract the attention of public officials. Increasingly people are participating in politics via the media, especially the Internet.

Contacting Public Officials

Expressing opinions about leaders, issues, and policies has become one of the most prominent forms of political participation. The number of people contacting public officials at all levels of government has risen markedly over the past three decades. Seventeen percent of Americans contacted a public official in 1976. By 2008, 44 percent of the public had contacted their member of Congress about an issue or concern (Congressional Management Foundation, 2008). E-mail has made contacting public officials cheaper and easier than the traditional method of mailing a letter.

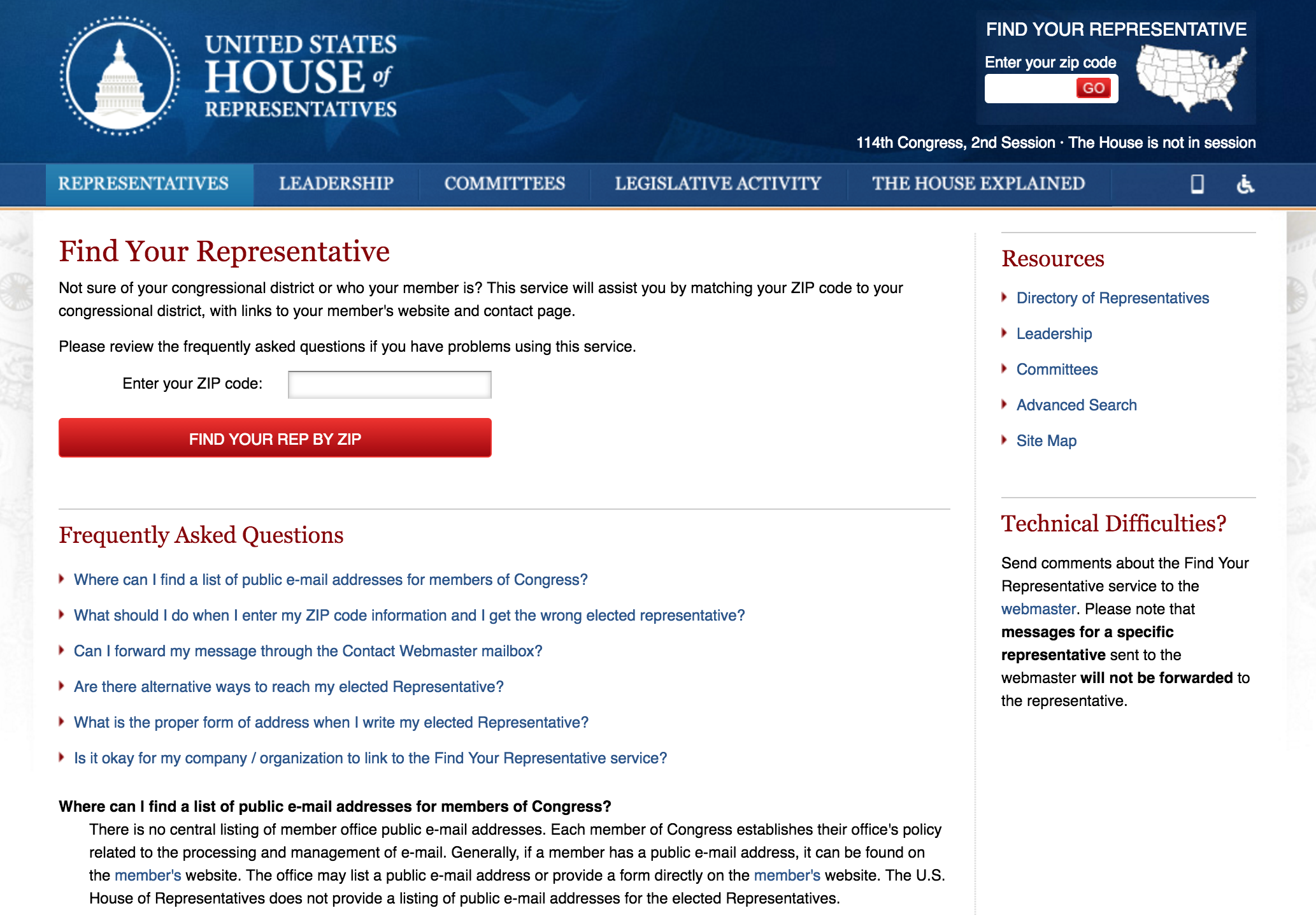

The directive to “write your member of Congress” is taken seriously by increasing numbers of citizens: legislators’ e-mail boxes are filled daily, and millions of letters are processed by the Capitol Hill post offices.

www.house.gov – public domain.

Students interning for public officials soon learn that answering constituent mail is one of the most time-consuming staff jobs. Every day, millions of people voice their opinions to members of Congress. The Senate alone receives an average of over four million e-mail messages per week and more than two hundred million e-mail messages per year (Congressional Management Foundation, 2008). Still, e-mail may not be the most effective way of getting a message across because office holders believe that an e-mail message takes less time, effort, and thought than a traditional letter. Leaders frequently are “spammed” with mass e-mails that are not from their constituents. Letters and phone calls almost always receive some kind of a response from members of Congress.

Contributing Money

Direct mail appeals by single-issue groups for contributions aimed especially at more affluent Americans are targeted methods of mobilizing people.

Wikimedia Commons – CC BY-SA 3.0.

The number of people who give money to a candidate, party, or political organization has increased substantially since the 1960s. Over 25 percent of the public gave money to a cause and 17 percent contributed to a presidential candidate in 2008 (Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, 2008). Direct mail and e-mail solicitations make fundraising easier, especially when donors can contribute through candidate and political-party websites. A positive side effect of fundraising campaigns is that people are made aware of candidates and issues through appeals for money (Jacobson, 1997).

Americans are more likely to make a financial contribution to a cause or a candidate than to donate their time. As one would expect, those with higher levels of education and income are the most likely to contribute. Those who give money are more likely to gain access to candidates when they are in office.

Campaign Activity

In addition to voting, people engage in a range of activities during campaigns. They work for political parties or candidates, organize campaign events, and discuss issues with family and friends. Generally, about 15 percent of Americans participate in these types of campaign activities in an election year (Verba, Schlozman, & Brady, 1995).

New media offer additional opportunities for people to engage in campaigns. People can blog or participate in discussion groups related to an election. They can create and post videos on behalf of or opposed to candidates. They can use social networking sites, like Facebook, to recruit supporters, enlist volunteers for campaign events, or encourage friends to donate money to a candidate.

Participation in the 2008 presidential election was greater than usual, as people were motivated by the open race and the candidate choices.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

The 2008 presidential election sparked high levels of public interest and engagement. The race was open, as there was no incumbent candidate, and voters felt they had an opportunity to make a difference. Democrat Barack Obama, the first African American to be nominated by a major party, generated enthusiasm, especially among young people. In addition to traditional forms of campaign activity, like attending campaign rallies and displaying yard signs, the Internet provided a gateway to involvement for 55 percent of Americans (Owen, 2009). Young people, in particular, used social media, like Facebook, to organize online on behalf of candidates. Students advertised campus election events on social media sites, such as candidate rallies and voter registration drives, which drew large crowds.

Running for and Holding Public Office

Being a public official requires a great deal of dedication, time, energy, and money. About 3 percent of the adult population holds an elected or appointed public office (Verba, Schlozman, & Brady, 1995). Although the percentage of people running for and holding public office appears small, there are many opportunities to serve in government.

Potential candidates for public office must gather signatures on a petition before their names can appear on the ballot. Some people may be discouraged from running because the signature requirement seems daunting. For example, running for mayor of New York City requires 7,500 signatures and addresses on a petition. Once a candidate gets on the ballot, she must organize a campaign, solicit volunteers, raise funds, and garner press coverage.

Protest Activity

Protests involve unconventional, and sometimes unlawful, political actions that are undertaken in order to gain rewards from the political and economic system. Protest behavior can take many forms. People can engage in nonviolent acts of civil disobedience where they deliberately break a law that they consider to be unjust (Lipsky, 1968). This tactic was used effectively during the 1960s civil rights movement when African Americans sat in whites-only sections of public busses. Other forms of protest behavior include marking public spaces with graffiti, demonstrating, and boycotting. Extreme forms of protest behavior include acts that cause harm, such as when environmental activists place spikes in trees that can seriously injure loggers, terrorist acts, like bombing a building, and civil war.

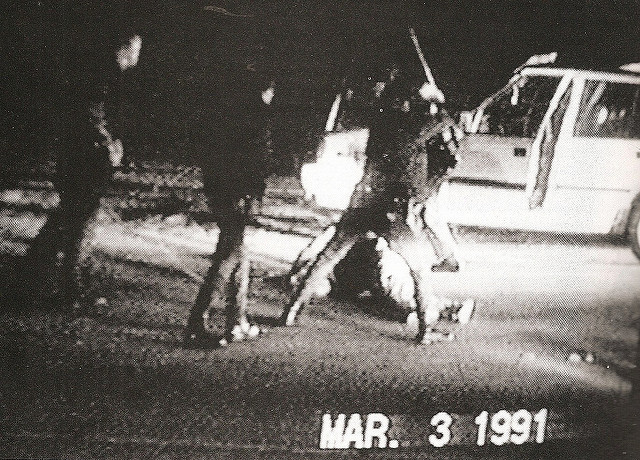

Figure 8.6 The Watts Riots

The Watts riots in 1965 were the first of a number of civil disturbances in American cities. Although its participants thought of them as political protests, the news media presentation rarely gave that point of view.

Extreme discontent with a particular societal condition can lead to rioting. Riots are frequently spontaneous and are sparked by an incident that brings to a head deep-seated frustrations and emotions. Members of social movements may resort to rioting when they perceive that there are no conventional alternatives for getting their message across. Riots can result in destruction of property, looting, physical harm, and even death. Racial tensions sparked by a video of police beating Rodney King in 1991 and the subsequent acquittal of the officers at trial resulted in the worst riots ever experienced in Los Angeles.

Comparing Coverage

The Rodney King Video

In March 1991, KTLA News at Ten in Los Angeles interrupted programming to broadcast an eighty-one-second amateur videotape of several police officers savagely beating black motorist Rodney King as he stood next to his vehicle. A nineteen-second edit of the tape depicted the most brutal police actions and became one of the most heavily broadcast images in television news history. The original and the edited tape tell two different stories of the same event.

Viewing the entire tape, one would have seen a belligerent and violent Rodney King who was difficult for police to constrain. Not filmed at all was an intoxicated King driving erratically, leading police on an eight-mile, high-speed chase through crowded streets.

The edited video showing the beating of King told a different story of police brutality and was the basis of much controversy. Race relations in Los Angeles in 1991 were strained. The tape enraged blacks in Los Angeles who saw the police actions as being widespread within the Los Angeles Police Department and not an isolated incident.

Four white officers were tried in criminal court for the use of excessive force, and they were acquitted of all but one charge. Jurors were shown the entire tape, not just the famous nineteen-second clip. Soon after the verdict was announced, riots broke out. Demonstrators burned buildings and assaulted bystanders. Fifty-four people were killed and two thousand were wounded. Property damage was in the millions of dollars.

The video of the beating of Rodney King in Los Angeles in 1991 sparked riots.

ATOMIC Hot Links – Los Angele’s three day shoot – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

CBS News Report on the Rodney King Incident

The CBS News report on the Rodney King incident included the following controversial video.

http://www.cbsnews.com/video/watch/?id=1344797n .

LA Riots of 1992: Rodney King Speaks

(click to see video)

The following video is the CNN News Report on the Los Angeles Riots, including Rodney King’s appeal to stop the violence.

College students in the 1960s used demonstrations to voice their opposition to the Vietnam War. Today, students demonstrate to draw attention to causes. They make use of new communications technologies to organize protests by forming groups on the Internet. Online strategies have been used to organize demonstrations against the globalization policies of the World Trade Organization and the World Bank. Over two hundred websites were established to rally support for protests in Seattle, Washington; Washington, DC; Quebec City, Canada; and other locations. Protest participants received online instructions at the protest site about travel and housing, where to assemble, and how to behave if arrested. Extensive e-mail listservs keep protestors and sympathizers in contact between demonstrations. Twitter, a social messaging platform that allows people to provide short updates in real time, has been used to convey eyewitness reports of protests worldwide. Americans followed the riots surrounding the contested presidential election in Iran in 2009 on Twitter, as observers posted unfiltered, graphic details as the violent event unfolded.

Participation in Groups

About half the population takes part in national and community political affairs by joining an interest group, issue-based organization, civic organization, or political party. Organizations with the goal of promoting civic action on behalf of particular causes, or single-issue groups , have proliferated. These groups are as diverse as the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), which supports animal rights, the Concord Coalition, which seeks to protect Social Security benefits, and the Aryan Nation, which promotes white supremacy.

There are many ways to advocate for a cause. Members may engage in lobbying efforts and take part in demonstrations to publicize their concerns. They can post their views on blogs and energize their supporters using Facebook groups that provide information about how to get involved. Up to 70 percent of members of single-issue groups show their support solely by making monetary contributions (Putnam, 2000).

Volunteering

Even activities that on the surface do not seem to have much to do with politics can be a form of political participation. Many people take part in neighborhood, school, and religious associations. They act to benefit their communities without monetary compensation.

Maybe you coach a little league team, visit seniors at a nursing home, or work at a homeless shelter. If so, you are taking part in civil society , the community of individuals who volunteer and work cooperatively outside of formal governmental institutions (Eberly, 1998). Civil society depends on social networks , based on trust and goodwill, that form between friends and associates and allow them to work together to achieve common goals. Community activism is thriving among young people who realize the importance of service that directly assists others. Almost 70 percent of high school students and young adults aged eighteen to thirty report that they have been involved in community activities (Peter D. Hart Research Associates, 1998).

Key Takeaways

There are many different ways that Americans can participate in politics, including voting, joining political parties, volunteering, contacting public officials, contributing money, working in campaigns, holding public office, protesting, and rioting. Voting is the most prevalent form of political participation, although many eligible voters do not turn out in elections. People can take part in social movements in which large groups of individuals with shared goals work together to influence government policies. New media provide novel opportunities for political participation, such as using Facebook to campaign for a candidate and Twitter to keep people abreast of a protest movement.

- What are some of the ways you have participated in politics? What motivated you to get involved?

- What political causes do you care the most about? What do you think is the best way for you to advance those causes?

- Do you think people who have committed serious crimes should be allowed to vote? How do you think not letting them vote might affect what kind of policy is made?

Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE), “Young Voters in the 2010 Elections,” http://www.civicyouth.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/2010-Exit-Poll-FS-Nov-17-Update.pdf .

Congressional Management Foundation, Communicating with Congress: How the Internet Has Changed Citizen Engagement (Washington, DC: Congressional Management Foundation, 2008).

Eberly, D. E., America’s Promise: Civil Society and the Renewal of American Culture (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 1998).

Flanigan, W. H. and Nancy H. Zingale, Political Behavior of the American Electorate , 9th ed. (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 1999).

Human Rights Watch and the Sentencing Project, Losing the Vote: The Impact of Felony Disenfranchisement Laws (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2000).

Jacobson, G. C., The Politics of Congressional Elections (New York: HarperCollins, 1997).

Lipsky, M., “Protest as a Political Resource,” American Political Science Review , December 1968, 1145.

McDonald, M., “Voter Turnout,” United States Election Project , http://elections.gmu.edu/voter_turnout.htm .

Milbrath, L. W. and M. L. Goel, Political Participation , 2nd ed. (Chicago: Rand McNally, 1977).

Owen, D., “The Campaign and the Media,” in The American Elections of 2008 , ed. Janet M. Box-Steffensmeier and Steven E. Schier (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2009), 9–32.

Peter D. Hart Research Associates, New Leadership for a New Century (Washington, DC: Public Allies, August 28, 1998).

Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, “Pew Research Center for the People & the Press Re-Interview Poll, Nov, 2008,” Poll Database , http://people-press.org/questions/?qid=1720790&pid=51&ccid=51#top .

Piven, F. F. and Richard A. Cloward, Why Americans Still Don’t Vote (Boston: Beacon Press, 2000).

Putnam, R. D., Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000).

Rosenstone, S. J. and John Mark Hansen, Mobilization, Participation, and Democracy in America (New York: Macmillan, 1993), 4.

Verba, S., Kay Lehman Schlozman, and Henry E. Brady, Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995).

Wolfinger, R. E. and Steven J. Rosenstone, Who Votes? (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1980).

- “The Campaign: Rockers and Rappers,” The Economist , June 20, 1993, 25. ↵

American Government and Politics in the Information Age Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

The Oxford Handbook of Political Participation

Marco Giugni is a professor in the Department of Political Science and International Relations and director of the Institute of Citizenship Studies (InCite) at the University of Geneva. His research focuses on social movements and political participation. He recently co-edited, together with Maria Grasso, The Oxford Handbook of Political Participation (Oxford University Press 2022).

Maria Grasso, Queen Mary University of London

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The Oxford Handbook of Political Participation provides the first comprehensive, up-to-date treatment of political participation in all of its varied expressions. It covers a wide range of topics relating to the study of political participation from different disciplinary and methodological angles, such as the modes of participation, the role of the context as well as the determinants, processes, and outcomes of participation. The volume brings together the political science and political sociology tradition, on the one hand, and the social movement sociological tradition, on the other, is sensitive to theoretical and methodological pluralism as well as the most recent developments in the field, and includes discussions combining perspectives that have traditionally been treated separately in the literature as well as discussions of current trends and future directions for research in this field.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Political Participation: Inclusion of Citizens in Democratic Opinion-Forming and Decision-Making Processes

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2021

- Cite this reference work entry

- Sylke Nissen 7

Part of the book series: Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals ((ENUNSDG))

379 Accesses

1 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Arnstein SR (1969) A ladder of citizen participation. J Am Inst Plann 35:216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

Article Google Scholar

Asher HB, Richardson BM, Weisberg HF (1984) Political participation: an ISSC workbook in comparative analysis. Contributions to empirical social research. Campus, Frankfurt/New York

Google Scholar

Barber B (1984) Strong Democracy: participatory politics for a new age. University of California, Berkely

Barnes SH, Kaase M (eds) (1979) Political action: mass participation in five Western democracies. Sage, Beverly Hills/London

Brady HE, Verba S, Schlozman KL (1995) Beyond SES: a resource model of political participation. Am Polit Sci Rev 89:271–294. https://doi.org/10.2307/2082425

Burns N, Schlozman KL, Verba S (2001) The private roots of public action: gender, equality, and political participation. Harvard University, Cambridge, MA

Carter A (2006) The political theory of global citizenship. Taylor & Francis Books, New York

Christensen HS (2011) Political participation beyond the vote: how the institutional context shapes patterns of political participation in 18 western European democracies. Åbo Akademis Förlag, Åbo

Conge PJ (1988) The concept of political participation: toward a definition. Rev Artic Comp Polit 20:241–249

Dahl RA (1998) On democracy. Yale University Press, New Haven

Dienel P (1999) Planning cells: the German experience. In: Khan U (ed) Political dialogue between government and citizens. UCL Press, London, pp 81–94

Fox S (2014) Is it time to update the definition of political participation? Parliam Aff 67:495–505. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gss094

Gabriel OW (2000) Participation, interest mediation and political equality. Unintended consequences of the participatory revolution. In: Klingemann H-D, Neidhardt F (eds) On the future of democracy. Challenges in the age of globalisation. Edition Sigma, Berlin, pp 99–122 (published in German)

Gallego A (2008) Unequal political participation in Europe. Int J Sociol 37:10–25

Gallego A (2014) Unequal political participation worldwide. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Gibson R, Cantijoch M (2013) Conceptualizing and measuring participation in the age of the internet: is online political engagement really different to offline? J Polit 75:701–716. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381613000431

Gilster ME (2014) Putting activism in its place: the neighborhood context of participation in neighborhood-focused activism. J Urban Aff 36:33–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/juaf.12013

Kaase M, Marsh D (1979) Political action: a theoretical perspective. In: Barnes SH, Kaase M (eds) Political action: mass participation in five Western democracies. Sage, Beverly Hills/London, pp 27–56

Lijphart A (1999) Patterns of democracy: government forms and performance in thirty-six countries. Yale University Press, New Haven

Lindberg LN, Scheingold SA (1970) Europe’s would-be polity: patterns of change in the European Community. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Marien S, Hooghe M, Quintelier E (2010) Inequalities in non-institutionalized forms of political participation: a multi-level analysis of 25 countries. Polit Stud 58:187–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2009.00801.x

Marsh A, Kaase M (1979) Measuring political action. In: Barnes SH, Kaase M (eds) Political action: mass participation in five Western democracies. Sage, Beverly Hills/London, pp 57–96

Marshall TH (1950) Citizenship and social class. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Milbrath LW (1965) Political participation. Rand McNally, Chicago

Nissen S (1992) Citizenship in the modernization process. In: Nissen S (ed) Modernization after socialism. Metropolis, Marburg, pp 199–220 (published in German)

Nissen S (2020) Democracy alongside parliamentarism. On the ambivalence of citizen participation. In: Endreß M, Nissen S, Vobruba G(eds) The actuality of democracy. Structural problems and perspectives. Beltz Juventa, Weinheim, pp 57–103 (published in German)

Norris P (2008) Driving democracy: do power-sharing institutions work? Cambridge University Press, Cambridge/New York

Oxfam (1997) A curriculum for global citizenship. Oxfam’s Development Education Programme, London

Oxley L, Morris P (2013) Global citizenship: a typology for distinguishing its multiple conceptions. Br J Educ Stud 61:301–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2013.798393

Parry G, Moyser G, Day N (1992) Participation and democracy: political activity and attitudes in contemporary Britain. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK/New York

Przeworski A, Bardhan P, Bresser Pereira LC, Bruszt L, Choi JJ (1995) Sustainable democracy, 1. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge [u.a.]

Smith G, Wales C (2016) Citizens’ juries and deliberative democracy. Polit Stud 48:51–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.00250

Solijonov A (2016) Voter turnout trends around the world. IDEA, Stockholm

UNESCO (2014) Global citizenship education: preparing learners for the challenges of the 21st century. UNESCO, Paris

UNESCO (2015) Global citizenship education: topics and learning objectives, Open access for researchers, vol 3. UNESCO, Paris

van Biezen I, Mair P, Poguntke T (2012) Going, going, … gone? The decline of party membership in contemporary Europe. Eur J Polit Res 51:24–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2011.01995.x

van Deth JW (2014) A conceptual map of political participation. Acta Polit 49:349–367. https://doi.org/10.1057/ap.2014.6

Verba S (1967) Democratic participation. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci 373:53–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/000271626737300103

Verba S, Nie NH (1972) Political participation in America: political democracy and social equality. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago/London

Verba S, Schlozman KL, Brady HE (1995) Voice and equality: civic voluntarism in American politics. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Whiteley PF (2010) Is the party over? The decline of party activism and membership across the democratic world. Party Polit 17:21–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068810365505

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Sociology, University of Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany

Sylke Nissen

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sylke Nissen .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

European School of Sustainability Science and Research, Hamburg University of Applied Sciences, Hamburg, Germany

Walter Leal Filho

Center for Neuroscience and Cell Biology, Institute for Interdisciplinary Research, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal

Anabela Marisa Azul

Faculty of Engineering and Architecture, Passo Fundo University, Passo Fundo, Brazil

Luciana Brandli

University of Passo Fundo, Passo Fundo, Brazil

Amanda Lange Salvia

Istinye University, Istanbul, Turkey

Pinar Gökçin Özuyar

University of Chester, Chester, UK

Section Editor information

Graduate Program in Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Passo Fundo, São José, Passo Fundo, RS, Brazil

Department for Water, Environment, Civil Engineering and Safety, Magdeburg-Stendal University of Applied Sciences, Magdeburg, Germany

Petra Schneider

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Nissen, S. (2021). Political Participation: Inclusion of Citizens in Democratic Opinion-Forming and Decision-Making Processes. In: Leal Filho, W., Marisa Azul, A., Brandli, L., Lange Salvia, A., Özuyar, P.G., Wall, T. (eds) Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95960-3_42

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95960-3_42

Published : 16 June 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-95959-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-95960-3

eBook Packages : Earth and Environmental Science Reference Module Physical and Materials Science Reference Module Earth and Environmental Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

STUDYING POLITICAL PARTICIPATION: TOWARDS A THEORY OF EVERYTHING?

Related Papers

Mateusz Wajzer

This paper identifies the major problems associated with the process of conceptualizing political participation. Two of them are discussed in detail. The first problem is that researchers ascribe political characteristics to any social behaviour, which is unsupported by proper arguments that would relate the proposed concepts to the subject matter of political science. The second one points to the strong presence of normative and crypto-normative elements, especially in studies of democratic societies.

Jake Bowers

Asian Journal of Education and Social Studies

Sharon Campbell

This conceptual paper tends to abridge all the theories on political participation in voting system as well as contributing to the government. Political participation is a mandatory choice needs to be analyzed as it is a choice that the state had imposed on its citizens though it centres round very significant factors. Political participation is a necessary ingredient of every political system. By involving many in the matters of the state, political participation fosters stability and order by reinforcing the legitimacy of political authority. This review article defines the political participation, participants, the necessity of participation, the social, political, economic as well as psychological state of affairs that influence citizens to participate. It also highlights the apathy behind not participating and the types and causes of political participation. Thus the paper tries to present a thorough picture of the issues behind the process of political participation.

Political Participation in the Middle East

Holger Albrecht

Thamy Pogrebinschi

hrss hamburg review of social sciences

Markus Pausch

Political participation is an often claimed value in the political and scientific discourse, but it is not always clearly defined. This article tries to concretise the qualities of political participation by the introduction of a four-fold classification inspired by, and based on Ruut Veenhoven's model of the "four qualities of life". In this classification it is argued that political participation contributes on the one hand to the quality of democracy (outer qualities) and on the other hand to the individuals' feeling of self-determination and political freedom (inner qualities). Furthermore, different forms of participation are discussed in respect to their impact on these inner and outer qualities. Finally, indicators for each of the qualities are identified, described and critically discussed.

Human Affairs

Mariano Torcal , Jan Teorell

Iasonas Lamprianou

Although������ years of excellent scholarship has taught us much about the cross-sectional side of political participation, scholars do not know much about the dynamics of political participation, and thus they do not know much about how to study it, let alone think about it. This paper presents a way to understand what stimulates or inhibits episodes of political activity in the lives of ordinary Americans. It introduces the idea that a causal story of political participation must include two kinds of factors: those that affect the potential of a person to ...

RELATED PAPERS

Marek Turczyński

The Ceylon medical journal

Hemantha Senanayake

Joanne Riley

Revista Brasileira de Cartografia

José Claudio Mura

Maurice Dawson

Kazım Gemici

Psychological Reports

015-Fransisca Amelia Firdausyah

Marta Farias

Food Additives & Contaminants: Part A

Viorica Lopez-Avila

Fertility and Sterility

James Grifo

Journal of the American Society of Nephrology

Mingzhi Zhang

Brazilian Journal of Biology

PEDRO MARCOS DE ALMEIDA

Elizabeth Wenner

Organic Letters

Lijuan Jiao

Thrombosis Research

Jernej Vidmar

Journal of Tropical Pediatrics

Tran Nguyen Ngoc Ha (K17 DN)

Pakistan Journal of Botany

HUSSIEN IBRAHIM

Hans De Loof

Journal of shoulder and elbow arthroplasty

Troy Bornes

International journal of business management and economic review

mukhlis yunus

Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences

Nathalie Bréda

Markus Disse

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

Social Media and the Political Engagement of Young Adults: Between Mobilization and Distraction

Scholars have expressed great hopes that social media use can foster the democratic engagement of young adults. However, this research has largely ignored non-political, entertainment-oriented uses of social media. In this essay, I theorize that social media use can significantly dampen political engagement because, by and large, young adults use social media primarily for non-political purposes, which distracts rather than mobilizes.

Design/methodology/approach

I illustrate this argument using aggregate level data from the U.S., Germany, Switzerland, and Japan by comparing relative voter turnout and social media use data of young adults.

Data suggest a so called Social Media Political Participation paradox in those countries: The gap in voter turnout between young adults and older generations has not significantly decreased, despite a skyrocketing rise of social media use on the side of young adults, and the overwhelming research evidence that social media use fosters offline political participation.

Implications

When trying to understand the implications of social media for democracy across the globe, entertainment-oriented content needs to be brought back in.

Originality/value

This essay challenges the dominant research paradigm on social media use and political participation. It urges future research to theoretically develop, describe, and empirically test a comprehensive model of how social media use has the potential to mobilize and to distract.

1 Introduction

Around the globe, social media have become a centerpiece in young adults’ lives. Particularly with their smartphones, young adults can literally be on social media 24/7, permanently connected to the world and their peers ( Vorderer and Kohring 2013 ). In fact, when comparing the current young generation to their older counterparts, there is a fundamental difference in media use behaviors: While young adults, aged 16–25, rely on digital platforms or messenger services, such as Facebook, TikTok, YouTube, Twitter, Instagram, WhatsApp, or WeChat, to get the news, the older generation is much more likely to be exposed to traditional news sources such as television or newspapers. At the same time, there are dozens of studies around the globe demonstrating that, traditionally, young adults are less interested in traditional politics compared to older generations ( Delli Carpini 2017 ), less likely to vote, and generally less politically sophisticated ( Binder et al. 2021 ). In short, political parties had been, before the emergence of digital media, struggling to reach out to the younger generation. Especially when it comes to traditional institutions, you adults are often described as detached and apathetic (e.g., Binder et al. 2021 ; Loader et al. 2014 ).

Yet with social media, scholars have expressed great hopes regarding young adults’ democratic engagement (see Binder et al. 2021 ; Oser and Boulianne 2020 ): It has been argued that particularly social media can build new relationships between political actors and young adults, enable social interaction about political topics, connect people, enhance political opinion expression, equalize engagement and generally foster participation as well as boost voter turnout or contribute to social cohesion (e.g., Boulianne 2011 , 2015 , 2020 ; Goh et al. 2019 ; Loader et al. 2014 ). So, with digital media, there are grounds to believe that the generational engagement gap may be reduced, and that young citizens could be reengaged into the political world. In fact, scholars working on digital media and political engagement have been fascinated by this idea, largely pointing to democratically welcomed outcomes of social media use, such as learning or participation. For instance, researchers observed a positive relationship between the frequency of social media use and protest participation among the youth ( Valenzuala et al. 2014 ), and more generally, it has been found that political social media use is positively related to various forms of political participation (e.g., Ekström et al. 2014 ; Skoric and Zhu 2016 ). With recent meta-analyses on the topic, the evidence for the democratically positive outcomes of social media use is simply overwhelming, particularly in cross-sectional survey research ( Boulianne 2011 ; Chae et al. 2019 ; Skoric et al. 2016 ) and also with respect to young adults ( Boulianne and Theocharis 2020 ).

However, scholarship on the democratic outcomes of social media frequently seem to overlook the fact that social media are primarily used for entertainment and relational purposes, especially when it comes to young adults ( Dimitrova and Matthes 2018 ; but see Skoric and Zhu 2016 ; Theocharis and Quintelier 2016 ). That is, the social media use of young people is clearly dominated by non-political content ( Binder et al. 2021 ). Yet the vast majority of studies do not take these forms of exposure into account, eventually ignoring a large share of the diversity in content on social media. As a consequence, scholars have turned a blind eye on potentially distractive effects of social media use on political engagement, leading to a skewed overall picture of this research field. In this conceptual paper, I take a different approach by theorizing that social media use can significantly dampen political engagement. The main reason is that social media are primarily used for entertainment and social networking purposes, which has the potential to distract rather than mobilize ( Heiss and Matthes 2021 ).