You are here

Kidney cancer, table of contents, signs and symptoms, kidney disease and kidney cancer, complications, physical activity, alternative medicine, coping and support, questions for your doctor.

Kidney cancer is a disease that starts in the kidneys. It happens when healthy cells in one or both kidneys grow out of control and form a lump (called a tumor ).

Download the infographic:

- Your Kidneys and Cancer: Infographic

- Your Kidneys and Cancer - Infographic - En Español

In the early stages, most people don’t have signs or symptoms. Kidney cancer is usually found by chance during an abdominal (belly) imaging test for other complaints. As the tumor grows, you may have:

- Blood in the urine

- Pain in the lower back

- A lump in the lower back or side of the waist

- Unexplained weight loss, night sweats, fever, or fatigue

The reason why kidney cells change and become cancerous is not yet known.

We know that people are more likely to develop kidney cancer as they age. However, there are certain risk factors linked to the kidney cancer.

Kidney Cancer Animation Series

Watch these animated videos to learn more about kidney cancer.

Additional Languages:

A risk factor is anything that increases your chance of getting a disease. Some risk factors can be changed (smoking, as an example); but others cannot be changed (your gender or family history). Having a risk factor, or even several risk factors, does not mean you will get kidney cancer, but it may increase your risk.

- Risk factors for kidney cancer include:

- Being overweight (obese)

- High blood pressure

- Gender - about twice as many men as compared to women develop kidney cancer

- Being on dialysis treatment for advanced chronic kidney disease

- Family members with kidney cancer

- Long-term use of a pain-relieving drug called phenacetin

- Certain rare genetic diseases, such as von Hippel-Lindau disease, Birt Hogge Dube syndrome, and others

- History of long-term exposure to asbestos or cadmium

You may be able to lower your risk of developing kidney cancer by avoiding those risk factors that can be controlled. For example, stopping smoking may lower the risk, and controlling body weight and high blood pressure may help as well.

Studies show there is a link between kidney cancer and kidney disease .

Kidney cancer risk

Some studies show that people with kidney disease may have a higher risk for kidney cancer due to:

- Long-term dialysis: Some studies show that people on long-term dialysis have a 5-fold increased risk for kidney cancer. Experts believe this risk is due to kidney disease rather than dialysis.

- Immunosuppressant medicines: Some anti-rejection medicines that must be taken by kidney transplant recipients to prevent rejection can increase your risk for kidney cancer. However, taking your immunosuppressant medicine is important if you have a transplant. Without it, your body will reject your new kidney.

About one-third of the 300,000 kidney cancer survivors in the United States have or will develop kidney disease. [1] , [2]

Kidney disease risk

- Surgery to remove an entire kidney (radical nephrectomy) : Sometimes the entire kidney needs to be removed because the tumor is so large and most of the kidney has been destroyed. Your risk for kidney disease is higher if all (rather than part) of the kidney must be removed due to cancer. However, removing the whole kidney is often better for your survival if the tumor is large or centrally located. If a kidney tumor is small, it is better to undergo an operation to remove the tumor but not the entire kidney (partial nephrectomy). This approach decreases the chance of developing chronic kidney disease and associated problems with heart and blood vessel disease.

- Drugs to slow or stop cancer growth: Drugs that spread throughout the body to treat cancer cells, wherever they may be, are sometimes used to treat advanced kidney cancer. All cancer drugs have some side effects, but some can be toxic to the kidney (called nephrotoxic). The word “nephrotoxic” means it can damage your kidney function.

Remember, not everyone with kidney cancer will get kidney disease. Likewise, not everyone who has kidney disease or a transplant will get kidney cancer. Ask your doctor what you can do to lower your risk.

Sign up for a deeper dive into kidney cancer

Useful animated videos, information on treatments, and other helpful resources on kidney cancer.

General prevention tips

- Don’t smoke

- Maintain a healthy weight

- Find out if you’re exposed to certain toxins at work or at home (such as cadmium, asbestos, and trichloroethylene, which may increase kidney cancer risk)

Take care of your kidneys

People with kidney disease may be at increased risk for kidney cancer:

- Ask your healthcare provider about 2 simple tests to find your kidney score:

- A blood test for kidney function called GFR

- A urine test for kidney damage called ACR

- Avoid prolonged use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen and naproxen

- Manage high blood pressure

- Manage your blood sugar if you have diabetes

Be aware of certain risk factors

- Family history of kidney cancer

- Certain diseases you may have been born with, such as von Hippel-Lindau disease

Renal cell carcinoma

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common type of kidney cancer in adults. RCC usually starts in the lining of tiny tubes in the kidney called renal tubules. RCC often stays in the kidney, but it can spread to other parts of the body, most often the bones, lungs, or brain.

Clear cell renal cell carcinoma

Clear cell renal cell carcinoma, also known as ccRCC or conventional renal cell carcinoma , is a the most common form of kidney cancer. Clear cell renal cell carcinoma is named after how the tumor looks under the microscope. The cells in the tumor look clear, like bubbles.

In adults, ccRCC makes up about 80% of all renal cell carcinoma cases. ccRCC is more common in adults than children. Renal cell carcinoma makes up 2% to 6% of childhood and young adult kidney cancer cases."

Rare types of kidney cancer

Rare kidney cancers occur most frequently in children, teenagers, and young adults.

Papillary renal cell carcinoma (PRCC)

- 15% of all renal cell carcinomas

- Tumor(s) located in the kidney tubes

- Type 1 PRCC is more common and grows slowly

- Type 2 PRCC is more aggressive and grows more quickly

Translocation renal cell carcinoma (TRCC)

- Accounts for 1% to 5% of all renal cell carcinomas and 20% of childhood caces

- Tumor(s) located in the kidney

- In children, TRCC usually grows slowly often without any symptoms

- In adults, TRCC tends to be agressive and fast-growing

Benign (non-cancerous) kidney tumors

Benign, or noncancerous kidney tumors grow in size but do not spread to other parts of the body and are not usually life-threatening. Surgical removal is the most common treatment and most tumors do you come back.

Papillary renal adenoma

- The most common benign kidney tumor

- Tumors are small, slow growing, often without any symptoms

- Usually an incidental finding on an imaging test done for a different readon

- Tumors start in the cells of the kidney collecting ducts and tumors can grow in one of both kidneys

- The tumors can grow to a large size about the These tumours can grow quite large, starting at just over an inch (walnut) and growing up to 4 inches (grapefruit)

Angiomyolipoma

- Benign fatty tumors can also be be due to overgrowth of blood vessel and smooth muscle tissue cells

- Tumors are non-cancerous, but they can become very large and destroy surrounding tissue

- Tumors that are over an inch and a half can cause internal bleeding

Complications from kidney cancer may include:

- Kidney failure

- Local spread of the tumor with increasing pain

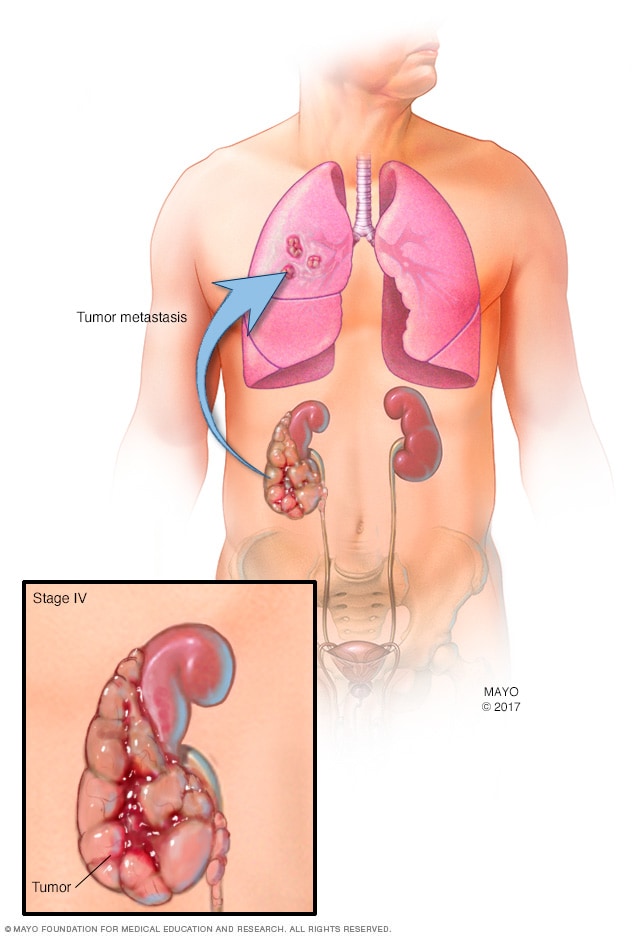

- Spread of the cancer to lung, liver, and bone

Your doctor will diagnose kidney cancer by reviewing your medical history and doing a physical exam, along with blood and urine tests.

Imaging tests:

- Computed tomography (CT) scans use x-rays to make a complete picture of the kidneys and abdomen (belly). They can be done with or without a contrast dye. Small amounts of radiation are used. The CT scan often shows if a tumor appears cancerous or if it has spread beyond the kidney.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans make a complete picture of the kidneys and abdomen, but without radiation. They can be done with or without a contrast dye called gadolinium that should be avoided in people on dialysis or with very low kidney function.

- Ultrasound uses sound waves to give a complete picture of the kidneys and abdomen without radiation. It may be useful in helping to decide if a mass in the kidneys is a fluid-filled cyst or a solid tumor. This test is done without contrast dye.

A biopsy can be used in special cases, but is typically not recommended. A biopsy requires a very small piece of the kidney to be removed with a needle and then tested for cancer cells.

Who can help

Discuss all your treatment options with your medical team.

Your medical team may include the following specialists:

- Urologist (a surgical doctor who treats the urinary system)

- Oncologist (a doctor who specializes in cancer)

- Radiation oncologist (a doctor who treats cancer with radiation)

- Nephrologist (kidney doctor)

- Oncology nurse

- Social worker

- Other healthcare professionals

Make medical and health-related appointments as soon as possible. You may need several opinions about what treatment choices are best for you.

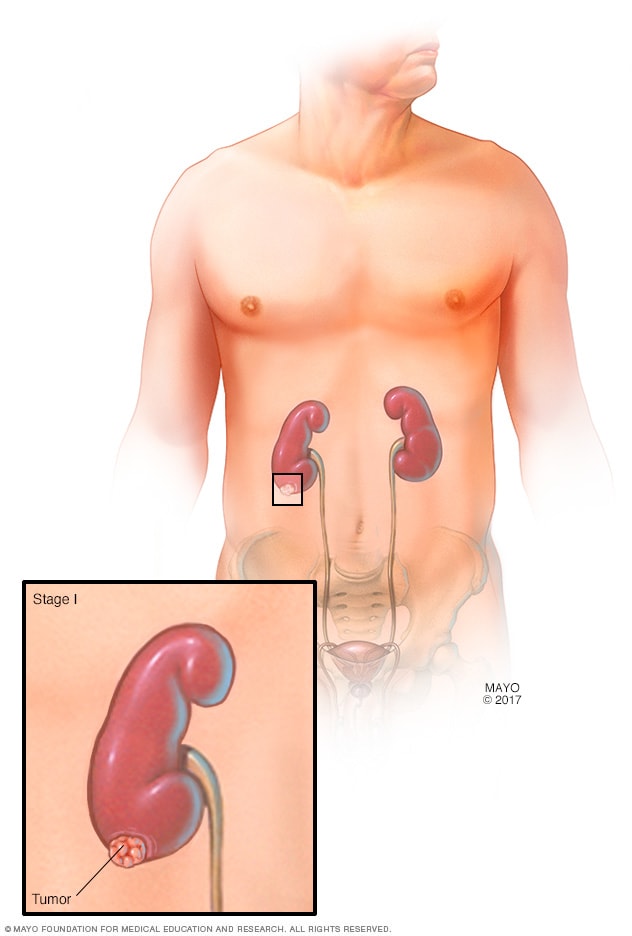

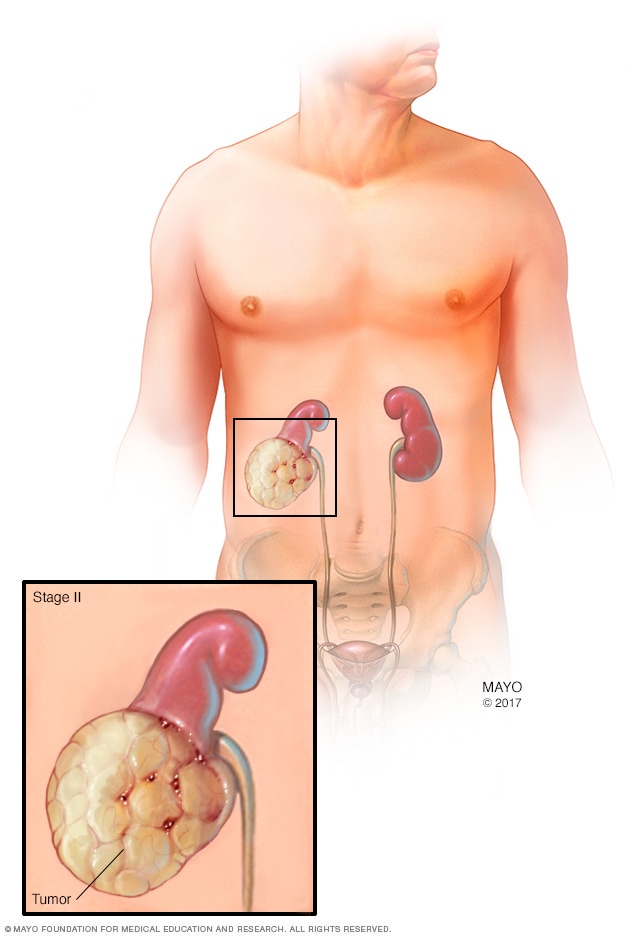

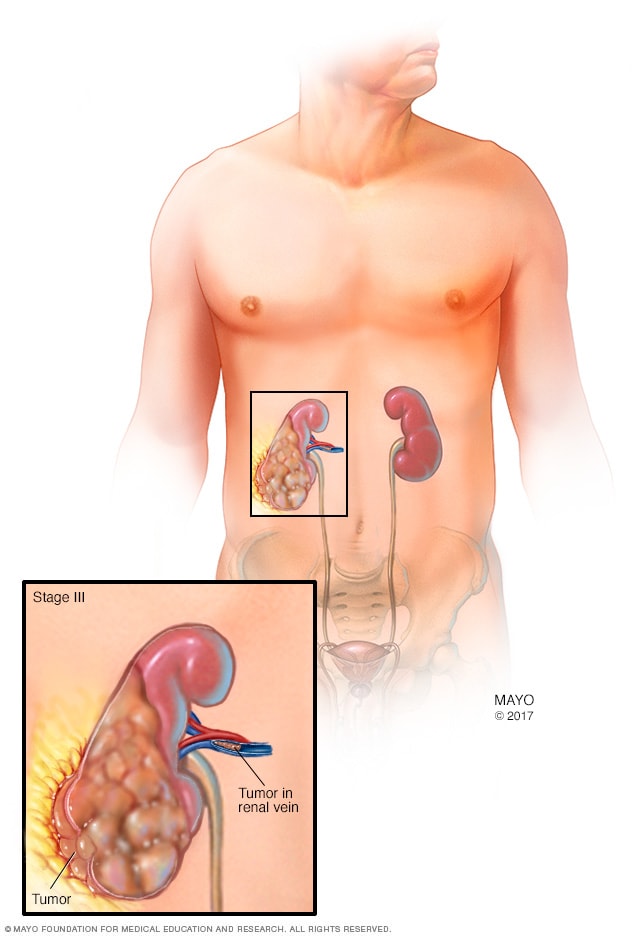

Once kidney cancer is found, your doctor will run tests to find out if the cancer has spread within the kidney or to other parts of the body. This process is called staging. It is important to know the stage before making a treatment plan. The higher the stage, the more serious the cancer.

The most common treatment for kidney cancer is with surgery to remove all or part of the kidney. However, your treatment will depend on the stage of your disease, your general health, your age, and other factors.

Surgery is most common treatment for kidney cancer—most people with early stage cancer (stages 1, 2, and 3) can be cured with surgery.

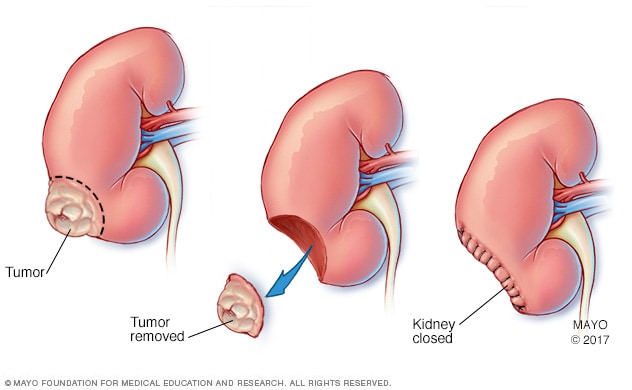

Partial nephrectomy

In a partial nephrectomy, the tumor or the part of the kidney with the tumor is removed to leave behind as much of the kidney as possible

Radical nephrectomy

In a radical nephrectomy, the entire kidney is removed. If needed, the surrounding tissues and lymph nodes may also be removed.

Surgical approaches

Ask your doctor about the surgical approach that is best for you:

- Open (traditional surgery with a long incision)

- Laparoscopic (surgery done with a video camera and thin instruments for smaller incisions)

- Robotic (laparoscopic surgery done with the help of a robot)

Nonsurgical options

Thermal ablation

Thermal ablation kills the tumor by burning or freezing and is most often used for small tumors in people who are not good candidates for nephrectomy surgery

Active surveillance

Active surveillance is used if a small tumor is less than 4 centimeters (1.5 inches)

Chemotherapy and radiation

Forms of chemotherapy and radiation used in other forms of cancer are not usually effective treatments for most forms of kidney cancer

Advanced or recurrent kidney cancer treatment

For people with advanced kidney cancer that has spread to other parts of the body, treatment with a drug may be recommended along with surgery, or instead of surgery. Some of these drugs are given to you as a pill that you take by mouth; others are given as an injection. Much progress has been made in recent years, and people with advanced kidney cancer are living much longer than ten years ago.

- Monoclonal antibodies attack a specific part of cancer cells

- Checkpoint inhibitors help the immune system recognize and attack cancer cells

- Vaccines give an overall boost to the immune system

- Anti-angiogenic therapies reduce the blood supply to a tumor to slow or stop its growth

- Targeted therapies directly inhibit the growth of the cancer

It is important to eat well for good nutrition during cancer treatment. Good nutrition means getting enough calories and nutrients to help prevent weight loss and regain strength. Patients who eat well often feel better and have more energy.

Some people find it hard to eat well during treatment. This is because their treatment may cause them to lose their appetite or have side effects like nausea, vomiting or mouth sores, which can make eating difficult. For some people, food tastes different. Others may not feel like eating because they feel uncomfortable or tired.

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is the term for medical products and practices that are not part of standard medical care. Please discuss with your healthcare team any CAM products you are using to make sure they won't affect your treatment plan. These products are not tested for safety, and many can be harmful.

People with cancer may use CAM to:

- Help cope with the side effects of cancer treatments, such as nausea, pain, and fatigue

- Comfort themselves and ease the worries of cancer treatment and related stress

- Feel that they are doing something to help with their own care

- Try to treat or cure their cancer

Mind & Body Therapies

These combine mental focus, breathing, and body movements to help relax the body and mind. Some examples are:

- Meditation: Focused breathing or repetition of words or phrases to quiet the mind

- Biofeedback: Using simple machines, the patient learns how to affect certain body functions that are normally out of one's awareness (such as heart rate)

- Hypnosis: A state of relaxed and focused attention in which a person concentrates on a certain feeling, idea, or suggestion to aid in healing

- Yoga: Systems of stretches and poses, with special attention given to breathing

- Tai Chi: Involves slow, gentle movements with a focus on the breath and concentration

- Imagery: Imagining scenes, pictures, or experiences to help the body heal

- Creative outlets: Interests such as art, music, or dance

Biologically Based Practices

This type of CAM uses things found in nature. Some examples are:

- Vitamins and dietary supplements

- Botanicals, which are plants or parts of plants such as cannibis

- Herbs and spices such as turmeric or cinnamon

- Special foods or diets

Manipulative and Body-Based Practices

These are based on working with one or more parts of the body. Some examples are:

- Massage: The soft tissues of the body are kneaded, rubbed, tapped, and stroked

- Chiropractic therapy: A type of manipulation of the spine, joints, and skeletal system

- Reflexology: Using pressure points in the hands or feet to affect other parts of the body

Biofield Therapy

Biofield therapy, sometimes called energy medicine, involves the belief that the body has energy fields that can be used for healing and wellness. Therapists use pressure or move the body by placing their hands in or through these fields. Some examples are:

- Reiki: Balancing energy either from a distance or by placing hands on or near the patient

- Therapeutic touch: Moving hands over energy fields of the body

Whole Medical Systems

These are healing systems and beliefs that have evolved over time in different cultures and parts of the world. Some examples are:

- Ayurvedic medicine: A system from India in which the goal is to cleanse the body and restore balance to the body, mind, and spirit

- Acupuncture is a common practice in Chinese medicine that involves stimulating certain points on the body to promote health, or to lessen disease symptoms and treatment side effects

- Homeopathy: Uses very small doses of substances to trigger the body to heal itself

- Naturopathic medicine: Uses various methods that help the body naturally heal itself. An example would be herbal treatment

Living with a serious illness is not easy. People with cancer and those who care about them face many problems and challenges. Coping with these problems often is easier when you have helpful information and support from friends and relatives. It also helps many people to meet in support groups to talk about their concerns with others who have or have had cancer. In support groups, patients share what they have learned about dealing with cancer and the effects of treatment.

Keep in mind that each person is different, and the same treatments and ways of dealing with cancer may not work for everyone. Always discuss the advice of friends and family with members of your healthcare team. Many cancer treatment centers have patient navigators who can help you:

- Know the right questions to ask your doctor and healthcare team

- Find more information about your condition and how to decide on the best treatment

- Make appointments and get the resources you need.

This support can reduce the stress of dealing with your care. Speaking with your doctor, healthcare team, and patient navigator about any concerns or questions is essential to getting the right information you need.

Find more information from the following organizations and programs.

National Cancer Institute

800.4.CANCER (800.422.6237) or www.cancer.gov

National Kidney and Urologic Disease Information Clearinghouse (NKUDIC) , a service of the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases. 800.891.5390 or www.niddk.nih.gov

Kidney Cancer Association www.kidneycancer.org

American Cancer Society 800.227.2345 or www.cancer.org

You and your healthcare provider need to work together. Here are some questions to start the conversation.

- Do I have kidney cancer?

- Has my cancer spread beyond my kidneys?

- Can my kidney cancer be cured?

- What are my treatment options?

- How long will treatment last?

- Are there any risks or side effects associated with my treatment?

- What will my recovery be like?

- How long will it take for me to recover from treatment?

- What are the chances of cancer coming back?

- Should I also see a nephrologist (kidney doctor)?

- Will you be partnering with a nephrologist about my care?

- Should I get a second opinion?

- How much experience do you have treating this kind of cancer?

- Are there any clinical trials I should think about?

[1] What are the Key Statistics about Kidney Cancer. American Cancer Society. 2016; http://www.cancer.org/cancer/kidneycancer/detailedguide/kidney-cancer-adult-key-statistics . Accessed October 20, 2016.

[2] Chang A, Finelli A, Berns JS, Rosner M. Chronic kidney disease in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. Jan 2014;21(1):91-95.

Kidney Cancer Infographic

Save this content:

Is this content helpful?

Back to top:

Kidney Cancer: An Overview of Current Therapeutic Approaches

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Oncology, Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA; Department of Pathology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA; Columbia Center for Translational Immunology, Columbia University Medical Center, 177 Fort Washington Avenue, Suite 6GN-435, New York, NY 10032, USA.

- 2 Columbia Center for Translational Immunology, Columbia University Medical Center, 177 Fort Washington Avenue, Suite 6GN-435, New York, NY 10032, USA; Department of Urology, Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbia University Medical Center, 177 Fort Washington Avenue, Suite 6GN-435, New York, NY 10032, USA; Division of Hematology and Oncology, Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbia University Medical Center, 177 Fort Washington Avenue, Suite 6GN-435, New York, NY 10032, USA. Electronic address: [email protected].

- PMID: 33008493

- DOI: 10.1016/j.ucl.2020.07.009

The management of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) has evolved rapidly in recent years with several immunotherapy-based combinations of strategies approved as first-line therapies. Targeted strategies, including systemic antiangiogenesis agents and immune checkpoint blockade, form the basis of a therapeutic approach. With rising rates of recurrence after first-line treatment, it is increasingly important to not only adopt a personalized treatment plan with minimal adverse events but also develop predictive biomarkers for response. This review discusses currently available first-line and second-line therapies in RCC and their pivotal data, with specific focus on ongoing clinical trials in the adjuvant setting, including those involving novel agents.

Keywords: Atezolizumab; Bevacizumab; Clear cell carcinoma; First-line immunotherapy; Kidney cancer; Pembrolizumab; Tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Copyright © 2020 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Biological Products / therapeutic use*

- Carcinoma, Renal Cell / drug therapy*

- Carcinoma, Renal Cell / mortality

- Carcinoma, Renal Cell / pathology

- Carcinoma, Renal Cell / surgery

- Clinical Trials, Phase II as Topic

- Combined Modality Therapy

- Drug Therapy, Combination

- Immunotherapy / methods*

- Kidney Neoplasms / drug therapy*

- Kidney Neoplasms / mortality

- Kidney Neoplasms / pathology

- Neoplasm Invasiveness / pathology

- Neoplasm Staging

- Nephrectomy / methods

- Survival Analysis

- Treatment Outcome

- United States

- Biological Products

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Kidney cancer

- Kidney cancer FAQs

Urologic oncologist Bradley Leibovich, M.D., answers the most frequently asked questions about kidney cancer.

I'm Dr. Brad Leibovich, a urologic oncologist at Mayo Clinic, and I'm here to answer some questions patients may have about kidney cancer.

Patients diagnosed with kidney cancer often want to know what could they have done differently to prevent this from happening in the first place. In most cases, kidney cancer is completely unrelated to how you've lived your life. And there's really nothing you could have done differently to have prevented this.

Prognosis for kidney cancer depends upon the stage at which the kidney cancer is discovered. For patients with early stage disease, the prognosis is excellent and the expectation is typically that somebody will be cured of their kidney cancer. For later stage disease, thankfully, we have many new treatments. And even if it's not possible to cure a patient, the expectation is we will significantly extend their life.

Patients that have been diagnosed with kidney cancer often want to know if it's necessary to remove the entire kidney. In some cases, the kidney can be preserved and only the tumor needs to be removed. In other cases, it's necessary to remove the entire kidney. Thankfully, most patients have a second kidney and have good enough kidney function with just one kidney, that this is not a problem.

Since most patients have relatively normal kidney function after having a kidney removed, in the majority of circumstances, you do not have to change your lifestyle. Most important is that you have a healthy lifestyle overall. Get good sleep, regular exercise, and have a healthy balanced diet. If you do need to change something about your lifestyle, your doctor will tell you.

Many patients want to know if they need to alter their diet after treatment for kidney cancer. In the majority of circumstances, people have normal enough kidney function that no special diet is required, and people can eat and drink however they did previously.

In my opinion, being the best partner to your medical team means learning as much as you can about your diagnosis and about your options. This will empower you to make the best decisions that are right for you. Never hesitate to ask your medical team any questions or inform them of any concerns you may have. Being informed makes all the difference. Thank you for your time. We wish you well.

- Stage I kidney tumor

The tumor can be up to 2 3/4 inches (7 centimeters) in diameter. The cancer is only in one kidney and completely contained within it.

- Stage II kidney tumor

The tumor is larger than 2 3/4 inches (7 centimeters) in diameter, but it's still confined to the kidney.

- Stage III kidney tumor

The tumor extends beyond the kidney to the surrounding tissue and may also have spread to nearby lymph nodes.

- Stage IV kidney tumor

Cancer spreads outside the kidney, to multiple lymph nodes or to distant parts of the body, such as the bones, liver or lungs.

Tests and procedures used to diagnose kidney cancer include:

- Blood and urine tests. Tests of your blood and your urine may give your doctor clues about what's causing your signs and symptoms.

- Imaging tests. Imaging tests allow your doctor to visualize a kidney tumor or abnormality. Imaging tests might include ultrasound, X-ray, CT or MRI .

- Removing a sample of kidney tissue (biopsy). In some situations, your doctor may recommend a procedure to remove a small sample of cells (biopsy) from a suspicious area of your kidney. The sample is tested in a lab to look for signs of cancer. This procedure isn't always needed.

Kidney cancer staging

Once your doctor identifies a kidney lesion that might be kidney cancer, the next step is to determine the extent (stage) of the cancer. Staging tests for kidney cancer may include additional CT scans or other imaging tests your doctor feels are appropriate.

The stages of kidney cancer are indicated by Roman numerals that range from I to IV, with the lowest stages indicating cancer that is confined to the kidney. By stage IV, the cancer is considered advanced and may have spread to the lymph nodes or to other areas of the body.

More Information

Kidney cancer care at Mayo Clinic

- Computerized tomography (CT) urogram

Kidney cancer treatment usually begins with surgery to remove the cancer. For cancers confined to the kidney, this may be the only treatment needed. If the cancer has spread beyond the kidney, additional treatments may be recommended.

Together, you and your treatment team can discuss your kidney cancer treatment options. The best approach for you may depend on a number of factors, including your general health, the kind of kidney cancer you have, whether the cancer has spread and your preferences for treatment.

Partial nephrectomy

During a partial nephrectomy, only the cancerous tumor or diseased tissue is removed (center), leaving in place as much healthy kidney tissue as possible. Partial nephrectomy is also called kidney-sparing surgery.

For most kidney cancers, surgery is the initial treatment. The goal of surgery is to remove the cancer while preserving normal kidney function, when possible. Operations used to treat kidney cancer include:

Removing the affected kidney (nephrectomy). A complete (radical) nephrectomy involves removing the entire kidney, a border of healthy tissue and occasionally additional nearby tissues such as the lymph nodes, adrenal gland or other structures.

The surgeon may perform a nephrectomy through a single incision in the abdomen or side (open nephrectomy) or through a series of small incisions in the abdomen (laparoscopic or robotic-assisted laparoscopic nephrectomy).

Removing the tumor from the kidney (partial nephrectomy). Also called kidney-sparing or nephron-sparing surgery, the surgeon removes the cancer and a small margin of healthy tissue that surrounds it rather than the entire kidney. It can be done as an open procedure, or laparoscopically or with robotic assistance.

Kidney-sparing surgery is a common treatment for small kidney cancers and it may be an option if you have only one kidney. When possible, kidney-sparing surgery is generally preferred over a complete nephrectomy to preserve kidney function and reduce the risk of later complications, such as kidney disease and the need for dialysis.

The type of surgery your doctor recommends will be based on your cancer and its stage, as well as your overall health.

Nonsurgical treatments

Small kidney cancers are sometimes destroyed using nonsurgical treatments, such as heat and cold. These procedures may be an option in certain situations, such as in people with other health problems that make surgery risky.

Options may include:

- Treatment to freeze cancer cells (cryoablation). During cryoablation, a special hollow needle is inserted through your skin and into the kidney tumor using ultrasound or other image guidance. Cold gas in the needle is used to freeze the cancer cells.

- Treatment to heat cancer cells (radiofrequency ablation). During radiofrequency ablation, a special probe is inserted through your skin and into the kidney tumor using ultrasound or other imaging to guide placement of the probe. An electrical current is run through the needle and into the cancer cells, causing the cells to heat up or burn.

Treatments for advanced and recurrent kidney cancer

Kidney cancer that comes back after treatment and kidney cancer that spreads to other parts of the body may not be curable. Treatments may help control the cancer and keep you comfortable. In these situations, treatments may include:

- Surgery to remove as much of the kidney cancer as possible. If the cancer can't be removed completely during an operation, surgeons may work to remove as much of the cancer as possible. Surgery may also be used to remove cancer that has spread to another area of the body.

- Targeted therapy. Targeted drug treatments focus on specific abnormalities present within cancer cells. By blocking these abnormalities, targeted drug treatments can cause cancer cells to die. Your doctor may recommend testing your cancer cells to see which targeted drugs may be most likely to be effective.

- Immunotherapy. Immunotherapy uses your immune system to fight cancer. Your body's disease-fighting immune system may not attack your cancer because the cancer cells produce proteins that help them hide from the immune system cells. Immunotherapy works by interfering with that process.

- Radiation therapy. Radiation therapy uses high-powered energy beams from sources such as X-rays and protons to kill cancer cells. Radiation therapy is sometimes used to control or reduce symptoms of kidney cancer that has spread to other areas of the body, such as the bones and brain.

- Clinical trials. Clinical trials are research studies that give you a chance to try the latest innovations in kidney cancer treatment. Some clinical trials assess the safety and effectiveness of potential treatments. Other clinical trials try to find new ways to prevent or detect disease. If you're interested in trying a clinical trial, discuss the benefits and risks with your doctor.

- Ablation therapy

- Biological therapy for cancer

- Nephrectomy (kidney removal)

- Radiation therapy

- Radiofrequency ablation for cancer

- Grateful patient talks about his Mayo Clinic experience

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies testing new treatments, interventions and tests as a means to prevent, detect, treat or manage this condition.

Alternative medicine

No alternative medicine therapies have been proved to cure kidney cancer. But some integrative treatments can be combined with standard medical therapies to help you cope with side effects of cancer and its treatment, such as distress.

People with cancer often experience distress. If you're distressed, you may have difficulty sleeping and find yourself constantly thinking about your cancer. You may feel angry or sad.

Discuss your feelings with your doctor. Specialists can help you sort through your feelings and help you devise strategies for coping. In some cases, medications may help.

Integrative medicine treatments may also help you feel better, including:

- Art therapy

- Massage therapy

- Music therapy

- Relaxation exercises

- Spirituality

Talk with your doctor if you're interested in these treatment options.

Coping and support

Each person copes with a cancer diagnosis in his or her own way. Once the fear that comes with a diagnosis begins to lessen, you can find ways to help you cope with the daily challenges of cancer treatment and recovery. These coping strategies may help:

- Learn enough about kidney cancer to feel comfortable making treatment decisions. Ask your doctor for details of your diagnosis, such as what type of cancer you have and the stage. This information can help you learn about the treatment options. Good sources of information include the National Cancer Institute and the American Cancer Society.

- Take care of yourself. Take care of yourself during cancer treatment. Eat a healthy diet full of fruits and vegetables, be physically active when you feel up to it, and get enough sleep so that you wake feeling rested each day.

- Take time for yourself. Set aside time for yourself each day. Time spent reading, relaxing or listening to music can help you relieve stress. Write your feelings down in a journal.

- Gather a support network. Your friends and family are concerned about your health, so let them help you when they offer. Let them take care of everyday tasks — running errands, preparing meals and providing transportation — so that you can focus on your recovery. Talking about your feelings with close friends and family also can help you relieve stress and tension.

- Get mental health counseling if needed. If you feel overwhelmed, depressed or so anxious that it's difficult to function, consider getting mental health counseling. Talk with your doctor or someone else from your health care team about getting a referral to a mental health professional, such as a certified social worker, psychologist or psychiatrist.

Preparing for your appointment

Start by making an appointment with your primary care doctor if you have signs or symptoms that worry you. If your doctor suspects you may have kidney cancer, you may be referred to a doctor who specializes in urinary tract diseases and conditions (urologist) or to a doctor who treats cancer (oncologist).

Consider taking a family member or friend along. Sometimes it can be hard to remember all the information provided during an appointment. Someone who accompanies you may remember something that you missed or forgot.

What you can do

At the time you make the appointment, ask if there's anything you need to do in advance, such as restrict your diet. Then make a list of:

- Symptoms you're experiencing, including any that may seem unrelated to the reason for your appointment

- Key personal information, including any major stresses or recent life changes

- All medications (prescription and over-the-counter), vitamins, herbs or other supplements that you're taking

- Questions to ask your doctor

List your questions from most to least important in case time runs out. Some basic questions to ask your doctor include:

- Do I have kidney cancer?

- If so, has my cancer spread beyond my kidney?

- Will I need more tests?

- What are my treatment options?

- What are the potential side effects of each treatment?

- Can my kidney cancer be cured?

- How will cancer treatment affect my daily life?

- Is there one treatment option you feel is best for me?

- I have these other health conditions. How can I best manage them together?

- Should I see a specialist?

- Are there brochures or other printed material that I can have? What websites do you recommend?

Don't hesitate to ask additional questions that may occur to you during your appointment.

What to expect from your doctor

Your doctor is likely to ask you a number of questions. Be ready to answer them so that you'll have time to cover any points you want to focus on. Your doctor may ask:

- When did you first begin experiencing symptoms?

- Have your symptoms been continuous or occasional?

- How severe are your symptoms?

- What, if anything, seems to improve your symptoms?

- What, if anything, appears to worsen your symptoms?

- Kidney cancer. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx. Accessed May 8, 2020.

- Partin AW, et al., eds. Malignant renal tumors. In: Campbell-Walsh-Wein Urology. 12th ed. Elsevier; 2021. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed May 8, 2020.

- Niederhuber JE, et al., eds. Cancer of the kidney. In: Abeloff's Clinical Oncology. 6th ed. Elsevier; 2020. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed May 8, 2020.

- Renal cell cancer treatment (PDQ). National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/types/kidney/patient/kidney-treatment-pdq. Accessed May 8, 2020.

- Distress management. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx. Accessed May 8, 2020.

- Alt AL, et al. Survival after complete surgical resection of multiple metastases from renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2011; doi:10.1002/cncr.25836.

- Lyon TD, et al. Complete surgical metastasectomy of renal cell carcinoma in the post-cytokine era. The Journal of Urology. 2020; doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000000488.

- Dong H, et al. B7-H1, a third member of the B7 family, co-stimulates T-cell proliferation and interleukin-10 secretion. Nature Medicine. 1999;5:1365.

- Peyronnet B, et al. Impact of hospital volume and surgeon volume on robot-assisted partial nephrectomy outcomes: A multicenter study. BJU International. 2018; doi:10.1111/bju.14175.

- Hsu RCJ, et al. Impact of hospital nephrectomy volume on intermediate- to long-term survival in renal cell carcinoma. BJU International. 2020; doi:10.1111/bju.14848.

- NCCN member institutions. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. https://www.nccn.org/members/network.aspx. Accessed May 20, 2020.

- Locations. Children's Oncology Group. https://www.childrensoncologygroup.org/index.php/locations. Accessed May 20, 2020.

- Kidney Cancer

- What is kidney cancer? An expert explains

Associated Procedures

News from mayo clinic.

- Mayo Clinic Minute: How is kidney cancer treated? March 20, 2023, 02:27 p.m. CDT

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Mayo Clinic Comprehensive Cancer Center

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida, and Mayo Clinic in Phoenix/Scottsdale, Arizona, have been recognized among the top Urology and Cancer hospitals in the nation for 2023-2024 by U.S. News & World Report.

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

- Doctors & departments

- Care at Mayo Clinic

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

Renal cancer articles from across Nature Portfolio

Renal cancer refers to all malignancies that occur within the kidney. Subtypes include renal cell carcinoma and Wilms tumours.

Related Subjects

- Renal cell carcinoma

- Wilms tumour

Latest Research and Reviews

Investigating the causal associations between metabolic biomarkers and the risk of kidney cancer

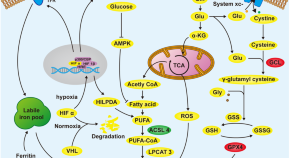

A multiple Mendelian randomization study emphasizes the central role of lactate in kidney tumorigenesis and provides novel insights into possible mechanism how phospholipids could affect kidney tumorigenesis.

- Yaxiong Tang

Targeting STING elicits GSDMD-dependent pyroptosis and boosts anti-tumor immunity in renal cell carcinoma

- Shengpan Wu

- Baojun Wang

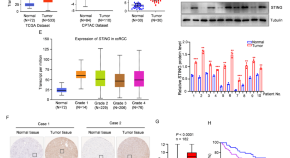

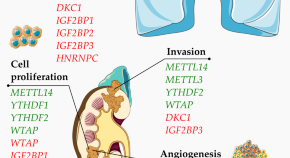

The role of RNA-modifying proteins in renal cell carcinoma

- Muna A. Alhammadi

- Khuloud Bajbouj

- Rifat Hamoudi

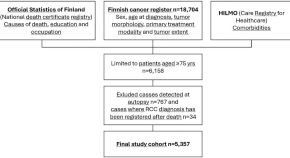

Prognostic factors of renal cell cancer in elderly patients: a population-based cohort study

- Heini Pajunen

- Thea Veitonmäki

- Teemu Murtola

The integrate profiling of single-cell and spatial transcriptome RNA-seq reveals tumor heterogeneity, therapeutic targets, and prognostic subtypes in ccRCC

- Yanlong Zhang

- Xuefeng Huang

Frontier knowledge and future directions of programmed cell death in clear cell renal cell carcinoma

News and Comment

Pericyte–stem cell crosstalk in ccrcc.

- Susan J. Allison

First-line pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib is effective in non-clear-cell RCC

- Diana Romero

A triple dose of optimism: an initial foray into triplet therapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma

COSMIC-313 combines all of the approved drugs against actionable targets in renal cell carcinoma into one triplet regimen. Although this approach has greater clinical efficacy than one of the standard-of-care doublet therapies, toxicities can limit adequate drug administration and, thus, we argue that this regimen should not yet be adopted. We also discuss ongoing investigations of other triplet regimens.

- Kathryn E. Beckermann

- Brian I. Rini

PBRM1 loss redirects chromatin remodelling complex to recruit oncogenic factors

The loss of the polybromo-1 (PBRM1) subunit in a class of SWI/SNF chromatin remodelling complexes in clear cell renal cell carcinoma redirects the deficient complexes to aberrant enhancer regions. The catalytic subunit SMARCA4 of the PBRM1-deficient complexes recruits the nuclear factor-κB transcription factor to drive pro-tumorigenic programs.

New combination therapy for advanced-stage RCC

- Peter Sidaway

Patient preferences in the treatment of genitourinary cancers

Several newly approved therapies have substantially altered the treatment paradigm for multiple genitourinary cancers. Considering the existence of numerous possible treatment approaches, understanding which treatment attributes are most valued by each patient is crucial to physicians to recommend a cancer-directed treatment.

- David J. Benjamin

- Arash Rezazadeh Kalebasty

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Shop Online

- Common cancer symptoms

- Facts and figures

- Early detection and screening

- Check for signs of skin cancer

- Diet and exercise

- Smoking and tobacco

- Family history and cancer

- Environmental causes

- Workplace cancer

- Adenocarcinoma

- Anal cancer

- Brain cancer

- Breast cancer

- Breast cancer in men

- Bladder cancer

- Bone cancer

- Bowel cancer

- Cancer of unknown primary

- Cervical cancer

- Children, teens, and young adult cancers

- Head and neck cancers

- Hodgkin lymphoma

Kidney cancer

- Liver cancer

- Lung cancer

- Mesothelioma

- Mouth cancer

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- Non-melanoma skin cancer

- Oesophageal cancer

- Ovarian cancer

- Pancreatic cancer

- Prostate cancer

- Rare cancers

- Secondary bone cancer

- Skin cancer

- Stomach cancer

- Testicular cancer

- Throat cancer

- Thyroid cancer

- Uterine cancer

- Vaginal cancer

- Vulvar cancer

- Tests and scans

- Coping with a cancer diagnosis

- Your guides to best cancer care

- Telling friends and family

- Find a specialist

- Questions to ask your doctor

- Hospital visits for cancer patients and carers

- Telehealth for cancer patients and carers

- Living with cancer

- After cancer treatment

- Chemotherapy

Radiation therapy (radiotherapy)

- Complementary therapies

- Hormone therapy

Immunotherapy

- Clinical trials

Palliative care

Targeted therapy.

- Advanced cancer treatment

- Breast prostheses and reconstruction

- Changes in thinking and memory

- Mouth health

- Neutropenia

- Peripheral neuropathy

- Sexuality and intimacy

- Taste and smell changes

- Downloadable resources

- Cancer Council 13 11 20

- State based service finder

- Support groups

- Transport services

- Wig service

- Cancer support and information centres

- Children, adolescents and young adults

- Cancer and COVID-19

- Information for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

- Multilingual resources

- Cancer, work and you

- Practical and financial assistance

- Workshops and forums

- Ostomy Service

- Cancer Nurses

- Cancer Council Online Community

- Trusted resources

- Personal cancer stories

- One time donation

- Regular giving

- In memoriam

- In celebration

- Where your money goes

- Workplace Giving

- Upcoming Events and Programs

- Australia's Biggest Morning Tea

- Daffodil Day Appeal

- Relay For Life

- Girls' Night In

- The March Charge

- The Longest Day

- Ponytail Project

- Community fundraising

- Gala Events

- Entertainment books

- Donation tins

- Healthy fundraising

- Men’s Health Pitstop

- Wording for your will

- Shop online

- Find a stockist

- Clothes4Cancer Op Shop

- Clinical Practice Guidelines

- Clinical Guidelines Network

- National Secondary Students' Diet and Activity (NaSSDA) survey

- Research Opportunities, Grants and Scholarships

- Optimal Care Pathways

- Patient resources

- Screening information for GPs

- Informed financial consent

- Inequalities in cancer outcomes

- Caring for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

- Warning signs of cancer in children

- Online learning

- Australian Cancer Atlas

- Cancer Forum

- Diverse Languages and Cultures

- Conferences and events

- Looking Ahead

- Prevention policy

- Early detection policy

- National cancer care policy

- Clinical practice policy

- Supportive care policy

- Position statements

- Submissions to government

- Consumer engagement

- Media releases

- Our spokespeople

- Media contacts

- Cancer Council Australia

- Cancer Council ACT

- Cancer Council NSW

- Cancer Council NT

- Cancer Council Queensland

- Cancer Council SA

- Cancer Council Tasmania

- Cancer Council Victoria

- Cancer Council WA

- National committees

- Affiliations

- Corporate partnerships

- Endorsed Sun Protection Brands

Types of Cancer

What is kidney cancer.

Kidney cancer is cancer that starts in the cells of the kidney. The most common type of kidney cancer is renal cell carcinoma (RCC), accounting for about 90% of all cases. Usually only one kidney is affected, but in rare cases the cancer may develop in both kidneys.

Other less common types include:

- Urothelial carcinoma (also called transitional cell carcinoma) which can begin in the ureter or renal pelvis where the kidney and ureter meet. It is generally treated like bladder cancer .

- Wilms tumour, which is most common in younger children although it is still rare.

It is estimated that more than 4,600 people were diagnosed with kidney cancer in 2023. The average age at diagnosis is 65 years old.

Kidney cancer is the seventh most commonly diagnosed cancer in Australia, and it is estimated that one in 65 people will be diagnosed by the time they are 85.

Kidney cancer signs and symptoms

In its early stages, kidney cancer often does not produce any symptoms.

Symptoms may include:

blood in the urine or passing urine frequently or during the night, change in urine colour – dark, rusty or brown

pain or a dull ache in the side or lower back that is not due to an injury

a lump in the abdomen

constant tiredness

rapid, unexplained weight loss

fever not caused by a cold or flu.

These symptoms can occur with other illnesses and so they don’t necessarily mean you have kidney cancer. If you have any concerns, contact your doctor.

Causes of kidney cancer

The causes of kidney cancer are not known, but factors that put some people at higher risk are:

smoking – smokers have almost twice the risk of developing kidney cancer as nonsmokers

workplace exposure to chemicals such as arsenic, some metal degreasers or cadmium used in mining, welding, farming and painting

a family history of kidney cancer

being overweight or obese

high blood pressure

having advanced kidney disease

being male - men are more likely to develop kidney cancer.

Diagnosis of kidney cancer

Tests to diagnose kidney cancer include:

Blood and urine tests

These tests do not diagnose kidney cancer but will check your general health and for any signs of a problem in the kidney.

Imaging tests

If kidney cancer is detected, you may have scans to see if the cancer has spread to other parts of your body, such as an ultrasound, chest x-ray, CT scan , MRI , or radioisotope bone scan.

A biopsy removes a tissue sample for examination under a microscope and is a common way to diagnose cancer. However, biopsies are not often needed for kidney cancer before treatment ad imaging scans are good at showing if a kidney tumour is cancer.

If you do have a biopsy, it will be a core needle biopsy where an interventional radiologist will put a hollow needle through the skin to remove a tissue sample.

Treatment for kidney cancer

The main treatment for kidney cancer is surgery , alone or with radiation therapy (radiotherapy) and will depend on the extent of the cancer.

If you are a smoker, your doctors will advise you quit before you start treatment.

A CT scan, bone (radioisotope) scan and chest x-ray are done to determine the extent of the cancer.

The most common staging system used for kidney cancer is the TNM system , which describes the stage of the cancer from stage I to stage IV

Active surveillance

If small tumours are found in your kidney your doctor may recommend active surveillance or observation as it is likely that the tumours will not be aggressive and may not grow in your lifetime. You will have regular ultrasounds or CT scans to monitor the tumours.

A radical nephrectomy (removal of the affected kidney) is the most common type of surgery for renal cell carcinoma.

A partial nephrectomy (removal of part of the kidney) may be an option for people who have a small tumour in one kidney (less than 4cm), people with cancer in both kidneys and those who have only one working kidney.

Radiofrequency ablation

Radiofrequency ablation heats the tumour with high energy waves in order to kill the cancer cells. Your doctor will insert a needle into the tumour and an electrical current is passed into the tumour.

Immunotherapy works to enhance your body's own immune system. Immunotherapy is an option for people with advanced kidney cancer. Cytokines (proteins that activate the immune system) can be given intravenously or orally, and may shrink the cancer.

Targeted therapies may be recommended by your doctor if you have advanced kidney cancer or your cancer is growing quickly. Targeted therapies target specific molecules in cells to block cell growth. Targeted therapy drugs are usually given in the form of tablets or intraveneously.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have been trialled in people with advanced kidney cancer and found to cause fewer side effects than chemotherapy drugs.

Radiation therapy may be used if you are not able to have surgery. It may also be used in advanced kidney cancer to shrink tumours and relieve symptoms.

In some cases of kidney cancer, your medical team may talk to you about palliative care . Palliative care aims to improve your quality of life by alleviating symptoms of cancer.

As well as slowing the spread of kidney cancer, palliative treatment can relieve pain and help manage other symptoms. Treatment may include radiotherapy, chemotherapy or other drug therapies.

Treatment Team

- GP (General Practitioner) - looks after your general health and works with your specialists to coordinate treatment.

- Urologist- specialises in the treatment of diseases of the urinary system (male and female) and the male reproductive system

- Nephrologist- diagnoses and treats conditions that cause kidney (renal) failure or impairment.

- Medical oncologist - prescribes and coordinates the course of chemotherapy.

- Radiation oncologist - prescribes and coordinates radiation therapy treatment.

- Radiologist- interprets diagnostic scans (including CT, MRI and PET scans).

- Cancer nurse - assists with treatment and provides information and support throughout your treatment.

- Cancer care coordinators- coordinate your care, liaise with the multidisciplinary team and support you and your family throughout treatment.

- Dietitian - recommends an eating plan to follow while you are in treatment and recovery.

- Other allied health professionals - such as social workers, pharmacists, and counsellors .

Screening for kidney cancer

There is currently no national screening program for kidney cancer available in Australia.

Preventing kidney cancer

Not smoking or quitting smoking. Up to one third of kidney cancers are thought to be due to smoking.

Prognosis for kidney cancer

It is not possible for a doctor to predict the exact course of a disease, as it will depend on each person's individual circumstances. However, your doctor may give you a prognosis, the likely outcome of the disease, based on the type of kidney cancer you have, the test results, the rate of tumour growth, as well as your age, fitness and medical history.

In most cases, the earlier that kidney cancer is diagnosed, the better the prognosis.

- Understanding Kidney Cancer , Cancer Council Australia, © 2020. Last medical review of source booklet: November 2020.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer data in Australia [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023 [cited 2023 Sept 04]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer/cancer-data-in-australia

This information was last updated September 2023.

Back to all cancer types

Advertisement

Renal cancer: overdiagnosis and overtreatment

- Published: 12 August 2021

- Volume 39 , pages 2821–2823, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Giuseppe Rosiello 1 , 2 ,

- Alessandro Larcher 1 , 2 ,

- Francesco Montorsi 1 , 2 &

- Umberto Capitanio 1 , 2

3105 Accesses

12 Citations

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) accounts for approximately 4.1% of all new cancers, with a median age at diagnosis of 64 years. In 2020, around 73,750 new cases were expected to be diagnosed in the United States, with an age-adjusted rate of 16.3 cases/100.000 persons [ 1 ]. Worldwide, the incidence of RCC has been rising [ 2 ] due to the widespread use of cross-sectional imaging performed for other reasons (e.g. hypertension, diabetes, etc.) [ 3 ]. As a consequence, a significant increase in incidental detection of renal masses has been observed over time, especially in elderly patients, who are more likely to undergo radiological investigations for other health-related problems [ 4 ]. It is of note that early detection of kidney tumors has been accompanied by a clinical-stage migration toward earlier tumor stages. Specifically, despite locally advanced RCC continues to be diagnosed in a high proportion of patients, with up to 17% harbouring metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis [ 5 ], the rates of cT 1 renal masses increased from 40% in 1992 to roughly 70% in 2015 [ 6 ] Nevertheless, several reports demonstrated a lack of declining mortality rates for localized RCC over time [ 7 ], and the cancer-specific mortality rate of patients harbouring T 1a disease remains below 5% at 5 years. [ 4 ] Such a controversial relationship between increasing detection rates of small renal masses (SRMs), but relatively stable survival outcomes highlights the importance of carefully evaluating and discussing the phenomenon of early detection in RCC, and make the concept of “overdiagnosis” of great importance in this context.

“Overdiagnosis” can be defined as the detection of a renal mass that would not cause any symptoms or clinical progression, if never diagnosed [ 8 ]. Therefore, the overdiagnosis of a small, silent renal mass crashes against our limited ability in determining the nature and the aggressiveness of the incidentally detected mass. Indeed, despite some improvements have been done in the field of nuclear imaging and radiomics [ 9 ], the current technology is limited and still, more than 20% of surgery are done for SRMs, which result totally benign at final pathology.

During the last two decades, the incidence of RCC increased from 9.2 to 12.5 cases per 100.000 persons/year. Notably, over 45% of newly diagnosed RCC have tumor size ≤ 4 cm, and this percentage is on the rise. Based on what was previously stated, it is not surprising that the incidence of T 1a RCC recorded the highest increase over time: + 50% since the beginning of the new millennium. [ 10 ] However, more in-depth analyses of age-specific data are necessary to better understand this phenomenon and its implications in clinical practice. Specifically, despite the incidence rates of SRMs also increased in young adults (from 0.1 to 0.4 cases per 100.000 persons/year), [ 11 ] such estimates are much lower than what was recorded in the general population. [ 2 ] Conversely, data regarding elderly patients are extremely different and deserve particular attention. Indeed, approximately 75% of newly diagnosed RCC are reported in patients over the age of 60. The age-standardised incidence rate in this patient population is as high as 35.0 cases per 100.000 persons/year, and the highest rate is recorded in patients aged ≥ 75 years. [ 2 ] Moreover, the incidence of SRMs is 30-fold higher in ≥ 75 years old than in younger patients. [ 12 ] These data demonstrate the magnitude of the problem, and should not be underestimated but, instead, they should sensitize the urological community about the important implications that they may have, in a global and comprehensive evaluation of the phenomenon. Indeed, the potential consequences of overdiagnosis may be significant and include psychological and behavioural effects of disease labelling, physical harms and side effects of unnecessary tests or treatments, increased financial costs to individuals and wasted resources and opportunity costs to the health system. Last but not least, overdiagnosis may lead to an increased risk of overtreatment.

In RCC, overdiagnosis does not imply invasive detection manoeuvres, as happens for instance in other urological settings (e.g. prostatic biopsy). Therefore, more importantly than overdiagnosis, the most detrimental and dangerous aspect in RCC is the decision after the diagnosis or in other words—the potential “overtreating”. “Overtreatment” is a partially overlapped phenomenon which implies the treatment (and the related consequences) of cancer which wouldn’t have caused any symptom or cancer-related death. Overtreatment comes immediately after our inaccuracy in determining the characteristics of the mass. Even in the case of malignant pathology, the natural history of small low-grade kidney cancer is indolent—in most of the cases—if well balanced with life expectancy, comorbidities and competing risks mortality. Indeed, the majority of overdiagnoses happen in old and comorbid patients, where the balance between pro and cons is completely different relative to the diagnosis of RCC in a middle-aged and healthy patient. While postoperative complications are the most obvious danger resulting from surgical “overtreatment” of patients with SRMs, the decrease in renal function is also well-established [ 13 , 14 ], and the risk resulting from kidney surgery needs to be evaluated, especially in those at higher risk of long-term renal impairment, such as elderly or comorbid patients. Moreover, studies exploring the benefits of nephrectomy in patients older than 75 years with clinically localized cT 1 renal masses demonstrated no superiority of definitive treatment (either partial or radical approach) compared to active surveillance in terms of cancer-specific survival, due to decreased life expectancy in this patient population. In other words, most of these patients would not live long enough to benefit from surgery [ 4 ].

In the current issue of World Journal of Urology, review papers and original articles provide recent data which may limit the effect of overdiagnosis and overtreatment in the kidney cancer setting. Specifically, the natural history of untreated kidney cancer [ 15 ], the importance of frailty and comorbidities for clinical decision making [ 16 , 17 ], the role of contrast-enhanced ultrasound [ 18 ], the novelties in radiomics and biomarkers and the current ongoing active surveillance protocols were summarized and critically analyzed [ 19 , 20 , 21 ].

Motzer RJ, Jonasch E, Agarwal N, Bhayani S, Bro WP, Chang SS et al (2017) Kidney cancer, version 2.2017: clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 15:804–834. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2017.0100

Article Google Scholar

Capitanio U, Bensalah K, Bex A, Boorjian SA, Bray F, Coleman J et al (2019) Epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol 75:74–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2018.08.036

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Chow W-H, Dong LM, Devesa SS (2010) Epidemiology and risk factors for kidney cancer. Nat Rev Urol 7:245–257. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrurol.2010.46

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Sun M, Becker A, Tian Z, Roghmann F, Abdollah F, Larouche A et al (2014) Management of localized kidney cancer: calculating cancer-specific mortality and competing risks of death for surgery and nonsurgical management. Eur Urol 65:235–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2013.03.034

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Capitanio U, Montorsi F (2016) Renal cancer. Lancet 387:894–906. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00046-X

Kane CJ, Mallin K, Ritchey J, Cooperberg MR, Carroll PR (2008) Renal cell cancer stage migration: analysis of the national cancer data base. Cancer 113:78–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23518

Sun M, Thuret R, Abdollah F, Lughezzani G, Schmitges J, Tian Z et al (2011) Age-adjusted incidence, mortality, and survival rates of stage-specific renal cell carcinoma in North America: a trend analysis. Eur Urol 59:135–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2010.10.029

Welch HG, Black WC (2010) Overdiagnosis in cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 102:605–613. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djq099

Leong JY, Wessner CE, Kramer MR, Forsberg F, Halpern EJ, Lyshchik A et al (2020) Superb microvascular imaging improves detection of vascularity in indeterminate renal masses. J Ultrasound Med. https://doi.org/10.1002/jum.15299

Palumbo C, Pecoraro A, Knipper S, Rosiello G, Luzzago S, Deuker M et al (2020) Contemporary age-adjusted incidence and mortality rates of renal cell carcinoma: analysis according to gender, race, stage, grade, and histology. Eur Urol Focus. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euf.2020.05.003

Palumbo C, Pecoraro A, Rosiello G, Luzzago S, Deuker M, Stolzenbach F et al (2020) Renal cell carcinoma incidence rates and trends in young adults aged 20–39 years. Cancer Epidemiol 67:101762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2020.101762

King SC, Pollack LA, Li J, King JB, Master VA (2014) Continued increase in incidence of renal cell carcinoma, especially in young patients and high grade disease: United States 2001 to 2010. J Urol 191:1665–1670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2013.12.046

Bhindi B, Lohse CM, Schulte PJ, Mason RJ, Cheville JC, Boorjian SA et al (2019) Predicting renal function outcomes after partial and radical nephrectomy (figure presented). Eur Urol 75:766–772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2018.11.021

Rosiello G, Capitanio U, Larcher A (2019) Acute kidney injury after partial nephrectomy: transient or permanent kidney damage? Impact on long-term renal function. Ann Transl Med 7:S317–S317. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2019.09.156

McAlpine K, Finelli A (2021) Natural history of untreated kidney cancer. World J Urol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-020-03578-1

Walach MT, Wunderle MF, Haertel N et al (2021) Frailty predicts outcome of partial nephrectomy and guides treatment decision towards active surveillance and tumor ablation. World J Urol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-020-03556-7

Courcier J, De La Taille A, Lassau N et al (2021) Comorbidity and frailty assessment in renal cell carcinoma patients. World J Urol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-021-03632-6

Bertelli E, Palombella A, Sessa F et al (2021) Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) imaging for active surveillance of small renal masses. World J Urol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-021-03589-6

Patel SH, Singla N, Pierorazio PM (2021) Decision-making in active surveillance in kidney cancer: current trends and future urine and tissue markers. World J Urol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-021-03786-3

Rebez G, Pavan N, Mir MC (2021) Available active surveillance follow-up protocols for small renal mass: a systematic review. World J Urol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-020-03581-6

Kuusk T, Neves JB, Tran M et al (2021) Radiomics to better characterize small renal masses. World J Urol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-021-03602-y

Download references

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Urology, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Via Olgettina 60, 20132 MI, Milan, Lombardia, Italy

Giuseppe Rosiello, Alessandro Larcher, Francesco Montorsi & Umberto Capitanio

Division of Experimental Oncology, URI, Urological Research Institute, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, Italy

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Umberto Capitanio .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

None to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Rosiello, G., Larcher, A., Montorsi, F. et al. Renal cancer: overdiagnosis and overtreatment. World J Urol 39 , 2821–2823 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-021-03798-z

Download citation

Published : 12 August 2021

Issue Date : August 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-021-03798-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Kidney Cancer Research Results and Study Updates

See Advances in Kidney Cancer Research for an overview of recent findings and progress, plus ongoing projects supported by NCI.

In a clinical trial, an injectable form of nivolumab (Opdivo) was as effective against kidney cancer as the intravenous form of the drug. Side effects were also similar and treatment time was shorter. Injectable immunotherapies, several experts said, if found to be comparable to IV forms, can be more convenient to receive and accessible to more people.

Stereotactic body radiotherapy was effective in people with localized kidney cancer who weren’t able to have surgery to remove their tumor, a clinical trial has shown. No patients had their cancer start growing or died from cancer over the next 5 years.

FDA has approved belzutifan (Welireg) to treat adults with von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL) who have tumors of the kidney, brain, nervous system, or pancreas. The drug may help these patients avoid or delay surgery by shrinking their tumors.

Cabozantinib (Cabometyx) is an effective initial treatment for people with metastatic papillary renal cell carcinoma (PRCC), a rare type of kidney cancer. A clinical trial showed the drug was more effective than the current standard treatment.

Results from two studies show that a liquid biopsy that analyzes DNA in blood accurately detected kidney cancer at early and more advanced stages and identified and classified different types of brain tumors.

In two clinical trials, combination treatments that included an immune checkpoint inhibitor and axitinib (Inlyta) led to better outcomes for patients with advanced kidney cancer than treatment with sunitinib (Sutent), the standard initial therapy.

Results from an NCI-sponsored clinical trial may point to an important change in how some children with advanced Wilms tumor, a form of kidney cancer, are treated.

FDA has approved the combination of two immunotherapy drugs, nivolumab (Opdivo) and ipilimumab (Yervoy), as an initial treatment for some patients with advanced kidney cancer. Learn how this approval will affect patient care.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved cabozantinib (Cabometyx®) as an initial treatment for patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma, the most common type of kidney cancer.

Two new studies suggest that a new class of drugs can effectively target a molecular driver of the most common type of kidney cancer.

The FDA has approved two drugs, cabozantinib and lenvatinib, for patients whose advanced kidney cancers have progressed after prior treatment with antiangiogenic therapies.

Results from a recent clinical trial show that post-surgical therapy with two anti-angiogenesis drugs does not improve progression-free survival for patients with kidney cancer and may cause serious side effects.

Researchers with The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) report new findings on papillary renal cell carcinoma and prostate cancer.

We use cookies to enhance our website for you. Proceed if you agree to this policy or learn more about it.

- Essay Database >

- Essay Examples >

- Essays Topics >

- Essay on Urinary System

Free Kidney Cancer Essay Example

Type of paper: Essay

Topic: Urinary System , Kidney , Cancer , Condition , Medicine , Body , Risk , Treatment

Words: 1300

Published: 01/14/2022

ORDER PAPER LIKE THIS

Introduction