Introduction to qualitative nursing research

This type of research can reveal important information that quantitative research can’t.

- Qualitative research is valuable because it approaches a phenomenon, such as a clinical problem, about which little is known by trying to understand its many facets.

- Most qualitative research is emergent, holistic, detailed, and uses many strategies to collect data.

- Qualitative research generates evidence and helps nurses determine patient preferences.

Research 101: Descriptive statistics

Differentiating research, evidence-based practice, and quality improvement

How to appraise quantitative research articles

All nurses are expected to understand and apply evidence to their professional practice. Some of the evidence should be in the form of research, which fills gaps in knowledge, developing and expanding on current understanding. Both quantitative and qualitative research methods inform nursing practice, but quantitative research tends to be more emphasized. In addition, many nurses don’t feel comfortable conducting or evaluating qualitative research. But once you understand qualitative research, you can more easily apply it to your nursing practice.

What is qualitative research?

Defining qualitative research can be challenging. In fact, some authors suggest that providing a simple definition is contrary to the method’s philosophy. Qualitative research approaches a phenomenon, such as a clinical problem, from a place of unknowing and attempts to understand its many facets. This makes qualitative research particularly useful when little is known about a phenomenon because the research helps identify key concepts and constructs. Qualitative research sets the foundation for future quantitative or qualitative research. Qualitative research also can stand alone without quantitative research.

Although qualitative research is diverse, certain characteristics—holism, subjectivity, intersubjectivity, and situated contexts—guide its methodology. This type of research stresses the importance of studying each individual as a holistic system (holism) influenced by surroundings (situated contexts); each person develops his or her own subjective world (subjectivity) that’s influenced by interactions with others (intersubjectivity) and surroundings (situated contexts). Think of it this way: Each person experiences and interprets the world differently based on many factors, including his or her history and interactions. The truth is a composite of realities.

Qualitative research designs

Because qualitative research explores diverse topics and examines phenomena where little is known, designs and methodologies vary. Despite this variation, most qualitative research designs are emergent and holistic. In addition, they require merging data collection strategies and an intensely involved researcher. (See Research design characteristics .)

Although qualitative research designs are emergent, advanced planning and careful consideration should include identifying a phenomenon of interest, selecting a research design, indicating broad data collection strategies and opportunities to enhance study quality, and considering and/or setting aside (bracketing) personal biases, views, and assumptions.

Many qualitative research designs are used in nursing. Most originated in other disciplines, while some claim no link to a particular disciplinary tradition. Designs that aren’t linked to a discipline, such as descriptive designs, may borrow techniques from other methodologies; some authors don’t consider them to be rigorous (high-quality and trustworthy). (See Common qualitative research designs .)

Sampling approaches

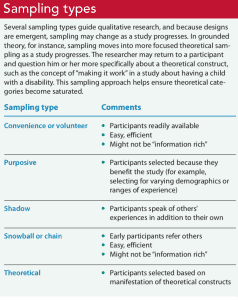

Sampling approaches depend on the qualitative research design selected. However, in general, qualitative samples are small, nonrandom, emergently selected, and intensely studied. Qualitative research sampling is concerned with accurately representing and discovering meaning in experience, rather than generalizability. For this reason, researchers tend to look for participants or informants who are considered “information rich” because they maximize understanding by representing varying demographics and/or ranges of experiences. As a study progresses, researchers look for participants who confirm, challenge, modify, or enrich understanding of the phenomenon of interest. Many authors argue that the concepts and constructs discovered in qualitative research transcend a particular study, however, and find applicability to others. For example, consider a qualitative study about the lived experience of minority nursing faculty and the incivility they endure. The concepts learned in this study may transcend nursing or minority faculty members and also apply to other populations, such as foreign-born students, nurses, or faculty.

Qualitative nursing research can take many forms. The design you choose will depend on the question you’re trying to answer.

A sample size is estimated before a qualitative study begins, but the final sample size depends on the study scope, data quality, sensitivity of the research topic or phenomenon of interest, and researchers’ skills. For example, a study with a narrow scope, skilled researchers, and a nonsensitive topic likely will require a smaller sample. Data saturation frequently is a key consideration in final sample size. When no new insights or information are obtained, data saturation is attained and sampling stops, although researchers may analyze one or two more cases to be certain. (See Sampling types .)

Some controversy exists around the concept of saturation in qualitative nursing research. Thorne argues that saturation is a concept appropriate for grounded theory studies and not other study types. She suggests that “information power” is perhaps more appropriate terminology for qualitative nursing research sampling and sample size.

Data collection and analysis

Researchers are guided by their study design when choosing data collection and analysis methods. Common types of data collection include interviews (unstructured, semistructured, focus groups); observations of people, environments, or contexts; documents; records; artifacts; photographs; or journals. When collecting data, researchers must be mindful of gaining participant trust while also guarding against too much emotional involvement, ensuring comprehensive data collection and analysis, conducting appropriate data management, and engaging in reflexivity.

Data usually are recorded in detailed notes, memos, and audio or visual recordings, which frequently are transcribed verbatim and analyzed manually or using software programs, such as ATLAS.ti, HyperRESEARCH, MAXQDA, or NVivo. Analyzing qualitative data is complex work. Researchers act as reductionists, distilling enormous amounts of data into concise yet rich and valuable knowledge. They code or identify themes, translating abstract ideas into meaningful information. The good news is that qualitative research typically is easy to understand because it’s reported in stories told in everyday language.

Evaluating a qualitative study

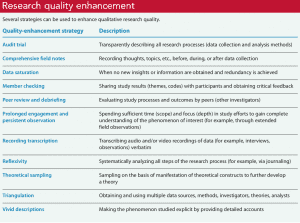

Evaluating qualitative research studies can be challenging. Many terms—rigor, validity, integrity, and trustworthiness—can describe study quality, but in the end you want to know whether the study’s findings accurately and comprehensively represent the phenomenon of interest. Many researchers identify a quality framework when discussing quality-enhancement strategies. Example frameworks include:

- Trustworthiness criteria framework, which enhances credibility, dependability, confirmability, transferability, and authenticity

- Validity in qualitative research framework, which enhances credibility, authenticity, criticality, integrity, explicitness, vividness, creativity, thoroughness, congruence, and sensitivity.

With all frameworks, many strategies can be used to help meet identified criteria and enhance quality. (See Research quality enhancement ). And considering the study as a whole is important to evaluating its quality and rigor. For example, when looking for evidence of rigor, look for a clear and concise report title that describes the research topic and design and an abstract that summarizes key points (background, purpose, methods, results, conclusions).

Application to nursing practice

Qualitative research not only generates evidence but also can help nurses determine patient preferences. Without qualitative research, we can’t truly understand others, including their interpretations, meanings, needs, and wants. Qualitative research isn’t generalizable in the traditional sense, but it helps nurses open their minds to others’ experiences. For example, nurses can protect patient autonomy by understanding them and not reducing them to universal protocols or plans. As Munhall states, “Each person we encounter help[s] us discover what is best for [him or her]. The other person, not us, is truly the expert knower of [him- or herself].” Qualitative nursing research helps us understand the complexity and many facets of a problem and gives us insights as we encourage others’ voices and searches for meaning.

When paired with clinical judgment and other evidence, qualitative research helps us implement evidence-based practice successfully. For example, a phenomenological inquiry into the lived experience of disaster workers might help expose strengths and weaknesses of individuals, populations, and systems, providing areas of focused intervention. Or a phenomenological study of the lived experience of critical-care patients might expose factors (such dark rooms or no visible clocks) that contribute to delirium.

Successful implementation

Qualitative nursing research guides understanding in practice and sets the foundation for future quantitative and qualitative research. Knowing how to conduct and evaluate qualitative research can help nurses implement evidence-based practice successfully.

When evaluating a qualitative study, you should consider it as a whole. The following questions to consider when examining study quality and evidence of rigor are adapted from the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research.

Jennifer Chicca is a PhD candidate at the Indiana University of Pennsylvania in Indiana, Pennsylvania, and a part-time faculty member at the University of North Carolina Wilmington.

Amankwaa L. Creating protocols for trustworthiness in qualitative research. J Cult Divers. 2016;23(3):121-7.

Cuthbert CA, Moules N. The application of qualitative research findings to oncology nursing practice. Oncol Nurs Forum . 2014;41(6):683-5.

Guba E, Lincoln Y. Competing paradigms in qualitative research . In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, eds. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.;1994: 105-17.

Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 1985.

Munhall PL. Nursing Research: A Qualitative Perspective . 5th ed. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2012.

Nicholls D. Qualitative research. Part 1: Philosophies. Int J Ther Rehabil . 2017;24(1):26-33.

Nicholls D. Qualitative research. Part 2: Methodology. Int J Ther Rehabil . 2017;24(2):71-7.

Nicholls D. Qualitative research. Part 3: Methods. Int J Ther Rehabil . 2017;24(3):114-21.

O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med . 2014;89(9):1245-51.

Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice . 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2017.

Thorne S. Saturation in qualitative nursing studies: Untangling the misleading message around saturation in qualitative nursing studies. Nurse Auth Ed. 2020;30(1):5. naepub.com/reporting-research/2020-30-1-5

Whittemore R, Chase SK, Mandle CL. Validity in qualitative research. Qual Health Res . 2001;11(4):522-37.

Williams B. Understanding qualitative research. Am Nurse Today . 2015;10(7):40-2.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Post Comment

NurseLine Newsletter

- First Name *

- Last Name *

- Hidden Referrer

*By submitting your e-mail, you are opting in to receiving information from Healthcom Media and Affiliates. The details, including your email address/mobile number, may be used to keep you informed about future products and services.

Test Your Knowledge

Recent posts.

Why COVID-19 patients who could most benefit from Paxlovid still aren’t getting it

Human touch

Leadership style matters

My old stethoscope

Nurse referrals to pharmacy

Lived experience

The nurse’s role in advance care planning

High school nurse camp

The transformational role of charge nurses in the post-pandemic era

Health Care Workers Push for Their Own Confidential Mental Health Treatment

Do We Simply Not Care About Old People?

Healthcare’s role in reducing gun violence

Early Release: Nurses and firearm safety

Gun violence: A public health issue

Eating disorders are the most lethal mental health conditions – reconnecting with internal body sensations can help reduce self-harm

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Global Qualitative Nursing Research

Preview this book.

- Description

- Aims and Scope

- Editorial Board

- Abstracting / Indexing

- Submission Guidelines

Journal Highlights

- Indexed in: Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI), PubMed Central (PMC) and Scopus

- Publication is subject to payment of an article processing charge (APC)

- Submit here

Global Qualitative Nursing Research (GQNR) is an open access peer reviewed journal focusing on qualitative research in fields relevant to nursing and other health professionals worldwide. Please see the Aims and Scope tab for further information. This journal is a member of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE). Submission information Submit your manuscript at https://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/gqn Please see the Submission Guidelines tab for more information on how to submit your article to the journal. Open access article processing charge (APC) information Publication in the journal is subject to payment of an article processing charge (APC). The APC serves to support the journal and ensures that articles are freely accessible online in perpetuity under a Creative Commons licence. Members of the International Institute for Qualitative Methodology are entitled to a 25% discount on the APC. The article processing charge (APC) for this journal is is 2000 USD. Contact Please direct any queries to [email protected] Special Sections Global Qualitative Nursing Research has the following special sections open for submission and publication:

- Methodological Development

- Advancing Theory/Metasynthesis

- Establishing Evidence

- Application to Practice

Translations Authors can publish translated versions of their article alongside the English version. Please see Submission Guidelines Section 6 for more details.

GQNR will publish research articles using qualitative methods and qualitatively-driven mixed-method designs as well as meta-syntheses and articles focused on methodological development. Special sections include Ethics, Methodological Development, Advancing Theory/Metasynthesis, Establishing Evidence, and Application to Practice.

- Clarivate Analytics: Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI)

- Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ)

- Google Scholar: h-5 index - 11, h-5 median - 13

- PubMed Central (PMC)

Global Qualitative Nursing Research (GQNR) is an international, interdisciplinary, refereed journal focusing on qualitative research in fields relevant to nursing world-wide. The journal specializes in topics related to nursing practice, responses to health, illness, and disability, health promotion, healthcare delivery, and global issues that affect nursing and healthcare. GQNR also welcomes qualitative studies pertinent to nursing that advance knowledge of diversity and systemic biases (e.g., racism), including the intersection of multiple oppressions and social identities, that shape experiences of health and illness, nursing and healthcare, and their implications for health equity. The journal provides a forum for sharing qualitative research from around the world that has international relevance for nursing.

GQNR will publish qualitative methods research, qualitatively-driven mixed-method designs, as well as meta-syntheses and articles focused on methodological developments. Each article accepted by peer review is made freely available online immediately upon publication, is published under a Creative Commons license and will be hosted online in perpetuity. Publication costs of the journal are covered by the collection of article processing charges which are paid by the funder, institution or author of each manuscript upon acceptance. There is no charge for submitting a paper to the journal.

The following author guidelines are designed assist authors with the manuscript preparation and submission process. Please note that manuscripts not conforming to these guidelines may be returned. Only manuscripts of sufficient quality that meet the aims and scope of Global Qualitative Nursing Research will be reviewed.

Sage Publishing disseminates high-quality research and engaged scholarship globally, and we are committed to diversity and inclusion in publishing. We encourage submissions from a diverse range of authors from across all countries and backgrounds.

Manuscript Submission Guidelines: Global Qualitative Nursing Research

- Open Access

- Article processing charge (APC)

- What do we publish? 3.1 Aims & Scope 3.2 Article types 3.3 Writing your paper 3.3.1 Making your article discoverable

- Editorial policies 4.1 Peer review policy 4.2 Authorship 4.3 Acknowledgements 4.4 Writing Assistance 4.5 Funding 4.6 Declaration of conflicting interests 4.7 Research ethics and patient consent 4.8 Clinical trials 4.9 Reporting guidelines 4.10 Diversity: Naming and exploring implications of systematic biases in research 4.11 Sex and gender equity in research

- Publishing policies 5.1 Publication ethics 5.2 Contributor’s publishing agreement

- Preparing your manuscript 6.1 Article format 6.2 Word processing formats 6.3 Writing style 6.4 Artwork, figures and other graphics 6.5 Reference style 6.6 English language editing services 6.7 Publishing translated versions of articles 6.8 Supplementary material

- Submitting your manuscript 7.1 Title, keywords and abstracts 7.2 ORCID 7.3 Information required for completing your submission 7.4 Permissions

- On acceptance and publication 8.1 SAGE Production 8.2 Continuous publication 8.3 Promoting your article

- Further information

1. Open Access

Global Qualitative Nursing Research (GQNR) is an open access, international, peer reviewed journal focusing on qualitative research in field relevant to nursing. GQNR will publish qualitative methods research, qualitatively-driven mixed-method designs, as well as meta-syntheses and articles focused on methodological developments. Each article accepted by peer review is made freely available online immediately upon publication, is published under a Creative Commons license and will be hosted online in perpetuity. Publication costs of the journal are covered by the collection of article processing charges which are paid by the funder, institution or author of each manuscript upon acceptance. There is no charge for submitting a paper to the journal.

For general information on open access at SAGE please visit the Open Access page or view our Open Access FAQs .

Back to top

2. Article processing charge (APC)

If, after peer review, your manuscript is accepted for publication, a one-time article processing charge (APC) is payable. This APC covers the cost of publication and ensures that your article will be freely available online in perpetuity under a Creative Commons license.

As of September 5 2023, the article processing charge (APC) is 2000 USD.

Students are entitled to a 75% discount off the current APC as long as they are the first and corresponding author. Validation is required after submission.

Members of the International Institute for Qualitative Methodology are entitled to a 25% discount on the APC.

Please note that all communication concerning the APC should be conducted with SAGE Publications rather than with GQNR.

3. What do we publish?

Global Qualitative Nursing Research welcomes submissions focusing on qualitative research in fields relevant to nursing and are aligned with the aims and scope of the journal outlined here: https://journals.sagepub.com/aims-scope/GQN .

GQNR is a nursing focused journal and regardless of the topic, if intended for nurses, it should reflect a nursing perspective and/or the contribution that nurses bring to interprofessional ways of delivering care. In addition, we encourage authors to use the language of nursing and nurses versus healthcare professionals, providers, and clinicians when referring to nurses.

GQNR is an international journal so the relevance of manuscripts to the subject field internationally and also its transferability into other care settings, cultures or nursing specialties should be considered.

3.1 Aims & Scope

Before submitting your manuscript to Global Qualitative Nursing Research, please ensure you have read the Aims & Scope.

3.2 Article types

Global Qualitative Nursing Research publishes the following types of articles:

- Single-method qualitative research

- Qualitatively-driven mixed-method research

- Qualitative studies that are part of multiple method projects

- Metasynthesis studies that advance theory

- Scoping reviews of qualitative research

- Qualitative methodological development

- Qualitative study protocols

Guidelines for each article type are included below:

Single method qualitative research : GQNR publishes high quality, methodologically rigorous qualitative research that contributes original findings to areas of international relevance for nursing, midwifery or related fields. The journal welcomes qualitative research papers that are based on various qualitative approaches and forms of data. A full description of the qualitative approach is required including the epistemological underpinnings/methodology and methods, and the analytical lens and strategies used in data analysis, and strategies to support rigor.

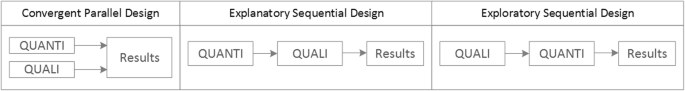

Qualitative driven mixed method research : GQNR invites articles about studies in which the main study was qualitative, and the supplementary data collection was either qualitative or quantitative (QUAL qant or QUAL qual designs) (for more information see Morse, 2003 , 2010 , 2016 ). Mixed-method studies are studies in which the data collected for a main study is supplemented with data that were collected using a data collection strategy that is not normally used in the main study. For example, a study using a grounded theory design in which laboratory results are added to qualitative data collected would be called a mixed-method study, but the addition of the same kind of quantitative data in an ethnographic study would not be called a mixed-method study, as ethnographies typically include both qualitative and quantitative data. Articles reporting studies designed using a mixed-method approach must include the data from both the main study and the supplemental component. Articles that describe supplemental data only will not be accepted, as the supplemental data cannot stand on its own; it is only interpretable in the context of the main study. Within the description of the design, the authors must include a statement about why a mixed-method approach was used. In the data collection section of the article, the authors must include an explanation about when and how the data from the main study and the supplemental component were integrated (e.g., Taylor, 2020 ).

Qualitative studies within multiple method research projects : GQNR is interested in receiving articles about qualitative studies that are part of multiple method projects, provided they meet the usual criteria for qualitative studies. Multiple method (multimethod) projects are comprised of a group of complete studies that are linked by one overarching aim. These studies may be qualitative or quantitative, are complete and can each stand alone, with separate but complementary research questions that link the study to the overall aim of the project. We also invite articles reporting the results of all the studies within a multiple method project (that include at least one qualitative study) and a description of how the results of each study contribute to the overarching aim of the project (e.g., Porr et al., 2010 ).

Metasynthesis studies that advance theory : Articles are invited that synthesize and interpret data across qualitative studies using relevant and rigorous approaches and make distinctive contributions to the body of evidence for practice. Articles should include inclusion/exclusion processes congruent with aims of the review; data display approaches that support analysis; evidence of critical reflection on the role played by method, theoretical framework, disciplinary orientation, and local conditions in shaping included studies; interpretations that reflect advances in the field over time; and a conceptually, well-integrated set of new findings that make a substantive contribution to the field that extends beyond individual qualitative studies. Systematic or scoping reviews of qualitative studies that simply summarize commonalities among a collection of qualitative studies will not be considered.

Scoping reviews of qualitative research: GQNR invites high quality, rigorous scoping reviews of qualitative research that are conducted for the purpose of identifying gaps in the current qualitative evidence, investigating how qualitative research has been conducted, and identifying areas that require further qualitative inquiry. A compelling rationale for the scoping review is required. Scoping reviews will only be considered if they clearly make a substantive and constructive contribution to the field and nursing and/or advance our thinking about qualitative methods. Possible contributions of scoping reviews of qualitative research include: advancing our thinking about how qualitative research is conducted on a particular topic/field and contributing to method development, clarifying concepts in the literature by examining relevant qualitative research, and mapping qualitative evidence to inform future research. Scoping reviews must be conducted using rigorous and transparent methods. Scoping reviews that include both qualitative and quantitative research will not be considered.

Methodological development : Articles are invited that focus on qualitative methods that provide insights, advances or innovations that are likely to be of interest to qualitative researchers in fields relevant to nursing world-wide. What the paper adds to existing methodological knowledge must be clearly explained.

Qualitative study protocols : To further the development of qualitative methods, GQNR accepts nationally funded study protocols for qualitative or qualitatively-driven mixed method studies that illustrate novel methodological ideas and/or practices. Student proposals / non-funded / locally-funded studies will not be considered. We encourage the submission of protocol manuscripts at an early stage of the study and prior to completion of data collection. Manuscripts that report work already carried out will not be considered as protocols. The dates of the study must be included in the manuscript and cover letter. Articles describing study protocols should include: background/study justification, explanation and justification of method, sampling/recruitment, data management/analysis plan, ethical considerations, and approach to supporting qualitative rigor. A dissemination plan (publications, data deposition and curation) should be included, as well as a discussion about how the methods will meet study aims. Proof of both ethics approval and funding will be required on submission as supplementary files. The inclusion of copies of interview guides and/or field work plans as supplementary files are encouraged. Reviewers will be instructed to review for clarity and sufficient detail. The intention of peer review is not to alter the study design. Reviewers will be asked to check that the study is scientifically credible (i.e., congruence between methodology and methods, strategies to establish rigor, etc.) and ethically sound in its scope and methods, and that there is sufficient detail to instill confidence that the study will be conducted successfully.

3.3 Writing your paper

The SAGE Author Gateway has some general advice and on how to get published , plus links to further resources.

3.3.1 Making your article discoverable

The title, keywords and abstract are key to ensuring readers find your article through search engines such as Google. For information and guidance on how to make your article more discoverable, visit our Gateway page on How to Help Readers Find Your Article Online.

4. Editorial policies

4.1 Peer review policy

SAGE does not permit the use of author-suggested (recommended) reviewers at any stage of the submission process, be that through the web-based submission system or other communication.

Reviewers should be experts in their fields and should be able to provide an objective assessment of the manuscript. Our policy is that reviewers should not be assigned to a paper if:

- The reviewer is based at the same institution as any of the co-authors.

- The reviewer is based at the funding body of the paper.

- The author has recommended the reviewer.

- The reviewer has provided a personal (e.g. Gmail/Yahoo/Hotmail) email account and an institutional email account cannot be found after performing a basic Google search (name, department and institution).

Following a preliminary triage to eliminate submissions unsuitable for Global Qualitative Nursing Research all papers are sent out for peer review. The cover letter is important. To help the Editor in this preliminary evaluation, please indicate in your letter to the editor why you think the paper is suitable for publication and relevant to the subject field internationally.

The journal’s policy is to have manuscripts reviewed by three expert reviewers. Global Qualitative Nursing Research utilizes a double-anonymized peer review process in which the reviewer and authors’ names and information are withheld from the other. All manuscripts are reviewed as rapidly as possible, while maintaining rigor. Reviewers make comments to the author and recommendations to the Editor-in-Chief who then makes the final decision.

GQNR maintains a transparent review system: once all reviews are received, they are forwarded to the author(s) as well as to ALL reviewers.

Global Qualitative Nursing Research is committed to delivering high quality, fast peer-review for your paper, and as such has partnered with Publons. Publons is a third-party service that seeks to track, verify and give credit for peer review. Reviewers for Global Qualitative Nursing Research can opt in to Publons in order to claim their reviews or have them automatically verified and added to their reviewer profile. Reviewers claiming credit for their review will be associated with the relevant journal, but the article name, reviewer’s decision and the content of their review is not published on the site. For more information visit the Publons website.

The Editor or members of the Editorial Board may occasionally submit their own manuscripts for possible publication in the journal. In these cases, the peer review process will be managed by alternative members of the Board and the submitting Editor/Board member will have no involvement in the decision-making process.

4.2 Authorship

Papers should only be submitted for consideration once consent is given by all contributing authors. Those submitting papers should carefully check that all those whose work contributed to the paper are acknowledged as contributing authors. The list of authors should include all those who can legitimately claim authorship. This is all those who:

- Made a substantial contribution to the concept or design of the work; or acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data,

- Drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content,

- Approved the version to be published,

- Each author should have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content.

Authors should meet the conditions of all of the points above. Each author should have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content.

When a large, multicenter group has conducted the work, the group should identify the individuals who accept direct responsibility for the manuscript. These individuals should fully meet the criteria for authorship.

Authors should determine the order of authorship among themselves and should settle any disagreements before submitting their manuscript. Changes in authorship (i.e., order, addition, and deletion of authors) should be discussed and approved by all authors. Any requests for such changes in authorship after initial manuscript submission and before publication should be explained in writing to the editor in a letter or email from all authors.

Acquisition of funding, collection of data, or general supervision of the research group alone does not constitute authorship, although all contributors who do not meet the criteria for authorship should be listed in the Acknowledgments section. Please refer to the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) authorship guidelines for more information on authorship.

4.3 Acknowledgements

All contributors who do not meet the criteria for authorship should be listed in an Acknowledgements section. Examples of those who might be acknowledged include a person who provided purely technical help, or a department chair who provided only general support.

4.4 Writing assistance

Individuals who provided writing assistance, e.g. from a specialist communications company, do not qualify as authors and so should be included in the Acknowledgements section. Authors must disclose any writing assistance – including the individual’s name, company and level of input – and identify the entity that paid for this assistance. It is not necessary to disclose use of language polishing services.

For manuscripts translated into English from another language, the name and affiliation of the translator may also be included. Except on a separate title page, the names of authors, and/or translators should not appear in manuscripts submitted for review; they are to be added only after the article is accepted for publication.

Please supply any personal acknowledgements separately to the main text to facilitate anonymous peer review.

4.5 Funding

To comply with the guidance for research funders, authors, and publishers issued by the Research Information Network (RIN), Global Qualitative Nursing Research requires all authors to acknowledge their funding in a consistent fashion under a heading “Funding.” Please visit the Funding Acknowledgements page on the SAGE Journal Author Gateway to confirm the format of the acknowledgment text in the event of funding, or state that: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

4.6 Declaration of conflicting interests

It is the policy of Global Qualitative Nursing Research to require a declaration of conflicting interests from all authors enabling a statement to be carried within the paginated pages of all published articles.

Please include your declaration at the end of your manuscript after any acknowledgments and prior to the references, under a heading “Declaration of Conflicting Interests.” If no conflict exists, please state that ‘The Author(s) declare(s) that there is no conflict of interest’. For guidance on conflict of interest statements, please see the ICMJE recommendations here .

When making a declaration the disclosure information must be specific and include any financial relationship that any author of the article has with any sponsoring organization and the for profit interests the organization represents, and with any for-profit product discussed or implied in the text of the article.

Any commercial or financial involvements that might represent an appearance of a conflict of interest need to be additionally disclosed in the covering letter accompanying your article, to assist the Editor in evaluating whether sufficient disclosure has been made within the Declaration of Conflicting Interests provided in the article.

4.7 Research ethics and patient consent

Medical research involving human subjects must be conducted according to the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki .

Submitted manuscripts should conform to the ICMJE Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing, and Publication of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals .

- All papers reporting animal and/or human studies must state in the methods section that the relevant Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board provided (or waived) approval. Please ensure that you anonymized the name and institution of the review committee until such time as your article has been accepted. The Editor will request authors to replace the name and add the approval number once the article review has been completed.

- For research articles, authors are also required to state in the methods section whether participants provided informed consent and whether the consent was written or verbal.

Global Qualitative Nursing Research is committed to protecting the identity and confidentiality of research study participants. With the exception of participatory action research (PAR), no information that could potentially allow identification of a participant—or even a specific study site—should be included in a submitted manuscript or, subsequently, in a published article. Study sites, such as hospitals, clinics, or other organizations, should not be named, but instead should be described; for example: “Study participants were recruited from the coronary care unit of a large metropolitan hospital on the eastern seaboard of the United States.”

Do not include participant names in the manuscript. If the use of names is absolutely necessary for reader understanding (this is rarely the case), use pseudonyms. Even when using pseudonyms, it should not be possible for the reader to “track” the comments or behaviors of any participant throughout the manuscript.

Authors who include participant names and/or photos/images in which individuals are identifiable must submit written permission from the participants to do so (no exceptions). Permission to use photographs should contain the following verbiage: “Permission is granted to use, reproduce, and distribute the likeness/photograph(s) in all media (print and electronic) throughout the world in all languages.”

Information on informed consent to report individual cases or case series should be included in the manuscript text. A statement is required regarding whether written informed consent for patient information and images to be published was provided by the patient(s) or a legally authorized representative.

Research participants have a right to privacy that should not be infringed upon without informed consent. Identifying information, including participants' names, initials, or other identifying characteristics, should not be published in written descriptions and photographs unless the information is essential for scientific purposes and the participant (or parent or guardian) gives signed and dated written informed consent for publication (submitted as a separate document when submitting the manuscript). Informed consent for this purpose requires that a participant who is identifiable be shown the manuscript to be published prior to giving consent.

Identifying details should be omitted if they are not essential. Faces in photographs should be obscured. If identifying characteristics are altered to protect anonymity, authors should provide assurance that alterations do not distort scientific meaning.

Please also refer to the ICMJE Recommendations for the Protection of Research Participants .

4.8 Clinical trials

Global Qualitative Nursing Research conforms to the ICMJE requirement that clinical trials are registered in a WHO-approved public trials registry at or before the time of first patient enrolment as a condition of consideration for publication. The trial registry name and URL, and registration number must be included at the end of the abstract.

4.9 Reporting guidelines

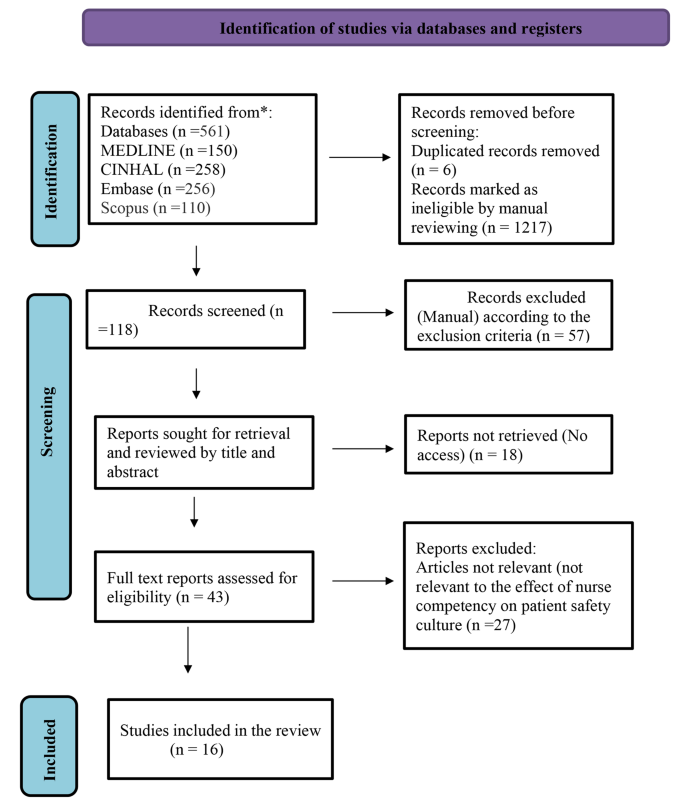

The relevant EQUATOR Network reporting guidelines should be followed depending on the type of study. Metasyntheses should include the completed PRISMA 2020 flow chart as a cited figure and the completed PRISMA checklist should be uploaded with your submission as a supplementary file. The EQUATOR wizard can help you identify the appropriate guideline. Other resources can be found at NLM’s Research Reporting Guidelines and Initiatives .

4.10 Diversity: Naming and exploring implications of systemic biases in research

GQNR encourages authors to acknowledge and advance understanding of diversity and systematic biases that shape experiences of health, illness, disability, nursing and healthcare, and their implications for health equity. Diversity includes all aspects of human differences such as socioeconomic status, race, ethnicity, language, nationality, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, geography, ability, age, and culture.

We invite authors to:

- consider diversity in the design, implementation, and evaluation of research

- name and explore implications of systemic biases (e.g., racism, ageism, ableism, and gender bias) as well as the intersection of multiple oppressions and social identities that shape health

- acknowledge the positionality of the researcher(s) in relation to the study context and its influence on the research process

- use non-stigmatizing, respectful person-first language (e.g., person who used opioids vs. opioid user or addict) or identity-first language (e.g., autistic person, deaf person or person with intellectual disability) keeping in mind what is best for representing study participants

Authors have an opportunity to address issues related to diversity in the background section, explain how diversity was accounted for in the study design, and/or how study findings address or do not address issues of diversity or reveal systemic bias and their implications for health equity.

4.11 Sex and gender equity in research

We encourage authors to follow the ‘ Sex and Gender Equity in Research – SAGER – guidelines ’ and to include sex and gender considerations where relevant. Authors should use the terms sex (biological attribute) and gender (shaped by social and cultural circumstances) carefully in order to avoid confusing both terms. Article titles and/or abstracts should indicate clearly what sex(es) the study applies to. Authors should also describe in the background, whether sex and/or gender differences may be expected; report how sex and/or gender were accounted for in the design of the study; provide disaggregated data by sex and/or gender, where appropriate; and discuss respective results. If a sex and/or gender analysis was not conducted, the rationale should be given in the Discussion. Resources related to integrating sex and gender in health research have been developed by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. They can be freely accessed here: www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/50833.html

5. Publishing policies

5.1 Publication ethics

SAGE is committed to upholding the integrity of the academic record. We encourage authors to refer to the Committee on Publication Ethics’ International Standards for Authors and view the Publication Ethics page on the SAGE Author Gateway .

5.1.1 Plagiarism

Global Qualitative Nursing Research and SAGE take issues of copyright infringement, plagiarism or other breaches of best practice in publication very seriously. We seek to protect the rights of our authors and we always investigate claims of plagiarism or misuse of published articles. Equally, we seek to protect the reputation of the journal against malpractice. Submitted articles may be checked with duplication-checking software. Where an article, for example, is found to have plagiarized other work or included third-party copyright material without permission or with insufficient acknowledgement, or where the authorship of the article is contested, we reserve the right to take action including, but not limited to: publishing an erratum or corrigendum (correction); retracting the article; taking up the matter with the head of department or dean of the author's institution and/or relevant academic bodies or societies; or taking appropriate legal action.

5.1.2 Duplicate and prior publication

Global Qualitative Nursing Research conforms to the ICMJE recommendations regarding duplicate and prior publications . If material has been previously published, it is not generally acceptable for publication in a SAGE journal. However, there are certain circumstances where previously published material can be considered for publication. Please refer to the guidance on the SAGE Author Gateway or if in doubt, contact the Editor at the address given below.

Duplicate publication is publication of a paper that overlaps substantially with one already published, without clear, visible reference to the previous publication. Prior publication may include release of information in the public domain (e.g., preprints).

When authors submit a manuscript reporting work that has already been reported in large part in a published article or is contained in or closely related to another paper that has been submitted or accepted for publication elsewhere, the letter of submission should clearly say so and the authors should provide copies of the related material to help the editor decide how to handle the submission.

Authors who choose to post their work on a preprint server should choose one that clearly identifies preprints as not peer-reviewed work and includes disclosures of authors’ relationships and activities. It is the author’s responsibility to inform a journal if the work has been previously posted on a preprint server. In addition, it is the author’s (and not journal editor’s) responsibility to ensure that preprints are amended to point readers to subsequent versions, including the final published article.

5.2 Contributor’s publishing agreement

Before publication SAGE requires the author as the rights holder to sign a Journal Contributor’s Publishing Agreement. Global Qualitative Nursing Research publishes manuscripts under Creative Commons licenses . The standard license for the journal is Creative Commons by Attribution Non-Commercial (CC BY-NC), which allows others to re-use the work without permission as long as the work is properly referenced and the use is non-commercial. For more information, you are advised to visit SAGE's OA licenses page .

Alternative license arrangements are available, for example, to meet particular funder mandates, made at the author’s request.

6. Preparing your manuscript

The following guidelines are designed to assist authors with the manuscript preparation and submission process. Manuscripts that do not conform to these guidelines will be returned to the authors without further review. The entire manuscript (including tables, figures, and references) must be prepared according to the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (APA Style Manual 7th edition).

6.1 Article format (see previously published articles in GQNR for style)

- Title page: Title should be succinct; list all authors and their affiliation; keywords. Please upload the title page separately from the main document.

- Include a short title (no more than 50 characters) as a header on all pages, including the title page, for the purposes of double-anonymized peer-review.

- Anonymized review: Do not include any author identifying information in your manuscript, including authors’ own citations. Do not include acknowledgements until the article is accepted.

- Abstract: Unstructured, 150-200 words . This should be the first page of the main manuscript, and it should be on its own page.

- Key words: Provide 4-6 keywords to highlight the main concepts and the scope of the manuscript. Please include region/country where the study was conducted as a key word if appropriate. Include key words following the abstract.

- Main manuscript text: GQNR does not have a word or page count limit. Manuscripts should be as tight as possible, preferably less than 30 pages including references . Longer manuscripts, if exceptional, will be considered.

- Ethics: Include a statement of IRB approval and participant consent. Present demographics as a group, not listed as individuals. Do not link quotations to particular individuals unless essential (as in case studies) as this threatens anonymity.

- Results: Rich and descriptive; theoretical; linked to practice if possible.

- Discussion: Link your findings with research and theory in literature, including other geographical areas and qualitative research.

- References: APA 7th Edition format. Use pertinent references only. References should be on a separate page.

6.2 Word processing formats

Accepted formats for the text, tables, and figures of submitted manuscripts are MS Word .doc and .docx files. The text must be double-spaced throughout. Set margins at 1 inch on all sides. Text should be in standard font (e.g., Times New Roman) 12-point. Do not add line numbers to the text; these are added automatically in the Manuscript Central system.

6.3 Writing style

Writing should be scholarly, and the style consistent throughout the manuscript. If there are two or more authors, do not use “I” statements. Use the past tense when writing about things that happened, were said, or were written in the past. Avoid anthropomorphic language; long, complex sentences; and unnecessary information. Voice: Both the abstract and the manuscript should be written in the first-person active voice. Avoid passive language.

6.4 Artwork, figures and other graphics

Include figures, charts, and tables created in MS Word in the main text rather than at the end of the document. However, figures, tables, and other files created outside of Word should be submitted separately. In this instance, please indicate where table and figures should be inserted within manuscript (e.g., INSERT TABLE 1 HERE). If using or adapting any copyrighted (previously published) material see APA for requirements.

6.4.1 Tables

Tables organize relevant, essential data that would be too awkward or too lengthy to include in the text, and should be used only to provide data not already included in the text. For example, grouped participant demographics take less space presented in a descriptive paragraph than they do as a table. Table titles should be concise and descriptive. Multiple tables within the same manuscript should be similar in appearance and design.

6.4.2 Figures

Like tables, figures should be used sparingly, and only when it is necessary to clarify complex relationships or concepts. Mention figure placement in the manuscript text, but submit each figure in a separate document, with the figure number and title on the first page, followed by the figure itself on the second page. Figure titles should be concise and descriptive. Designate placement of each figure within the manuscript by entering (on a separate line between paragraphs) INSERT FIGURE 1 ABOUT HERE. Figure callouts should be placed following the paragraph in which they are first mentioned. Figures supplied in color will appear in color online.

6.4.3 Photographs

Photographs may be included but should have permission to reprint and faces should be concealed using mosaic patches – unless permission has been given by the individual to use their identity. This permission must be forwarded to QHR’s Managing Editor.

TIFF, JPED, or common picture formats accepted. The preferred format for graphs and line art is EPS.

Resolution: Rasterized based files (i.e. with .tiff or .jpeg extension) require a resolution of at least 300 dpi (dots per inch). Line art should be supplied with a minimum resolution of 800 dpi.

Dimension: Check that the artworks supplied match or exceed the dimensions of the journal. Images cannot be scaled up after origination.

6.4.4 Artwork

Participant artwork may be included provided the content is free of any material that could potentially identify the participant who created it (or any persons who might be depicted). Use artwork only with the permission of the participant. All content should be dark enough to facilitate clear visibility online. Artwork supplied in color will appear in color online.

6.5 Reference style

Global Qualitative Nursing Research adheres to the APA 7th edition reference style. You may review this quick reference sheet to ensure your manuscript conforms to this reference style.

To anonymize the manuscript for review, citations for references authored by any author of the submitted manuscript should read only “(Author, year).” References authored by any author of the submitted manuscript should read only “Author. (year).” Do not include the reference title or any other information pertaining to the reference.

6.6 English language editing services

Authors seeking assistance with English language editing, translation, or figure and manuscript formatting to fit the journal’s specifications should consider using SAGE Language Services. Note: Some non-native English authors of accepted articles may be required to have their final manuscript professionally edited by a native-English-speaking editor. Visit SAGE Language Services on our Journal Author Gateway for further information, or contact the journal office at GQNR- [email protected] .

6.7 Publishing translated versions of articles

GQNR encourages authors to submit translated versions of your title, abstract and key words to be published alongside the English version. In addition, GQNR allows translated versions of accepted article to be published along with the English version as a supplementary file. Please follow the instructions in the submission site to ensure your translated version is published. Authors may use the proof of their accepted Article as the basis of the Translation and may use similar formatting and typesetting for the Translation as used in the original Article to create a PDF of the Translation. The Editor will arrange for light review of each Translation prior to publication. The review may be completed by a member of the Editorial Board or other trusted academic reviewer who is fluent in the language of the Translation to review the Translation to confirm there are no material errors in the Translation that result in an inconsistency with the original Article.

As part of GQNR’s commitment to supporting and disseminating qualitative nursing research internationally, selected articles may be subject to translation by GQNR following acceptance and/or publication. Authors will be notified if their article and/or the article title, abstract is selected for translation.

For further questions, please email [email protected]

6.8 Supplementary material

This journal is able to host additional materials online (e.g. datasets, podcasts, videos, images etc.) alongside the full-text of the article. These will be subjected to peer-review alongside the article. For more information please refer to our guidelines on submitting supplementary files, which can be found within SAGE’s Manuscript Submission Guidelines page.

7. Submitting your manuscript

Before submitting your manuscript, please carefully read and adhere to all of the guidelines and instructions provided below, especially the Manuscript Style. Manuscripts not conforming to these guidelines may be returned.

Global Qualitative Nursing Research is hosted on SAGE Track, a web based online submission and peer review system powered by ScholarOne™ Manuscripts. Visit https://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/GQNR to login and submit your article online. Please do not email manuscripts to the journal office.

PLEASE NOTE: If you are in the process of submitting a revision and will need an extension on the submission deadline, please email [email protected] If you choose not to submit a revision, please email [email protected] as soon as possible to notify us of this decision. Until a manuscript is formally withdrawn, it is considered under review at the journal that issued the revision decision.

IMPORTANT: Please check whether you already have an account in the system before trying to create a new one. If you have reviewed or authored for the journal in the past year it is likely that you will have had an account created. For further guidance on submitting your manuscript online please visit ScholarOne Online Help .

All papers must be submitted via the online system. If you seek advice on the submission process, please contact the Publishing Editor.

7.1 Title, keywords and abstract

Please supply a title, an abstract (unstructured, approximately 150 words) and keywords to accompany your article. The title, keywords and abstract are key to ensuring readers find your article online through online search engines such as Google. Please refer to the information and guidance on how best to title your article, write your abstract and select your keywords by visiting the SAGE Journal Author Gateway for guidelines on How to Help Readers Find Your Article Online .

7.2 Information required for completing your submission

Provide full contact details for the corresponding author including email, mailing address and telephone numbers. Academic affiliations are required for all co-authors. These details should be presented separately to the main text of the article to facilitate anonymous peer review.

You will be asked to provide contact details and academic affiliations for all co-authors via the submission system and identify who is to be the corresponding author. These details must match what appears on your manuscript. At this stage please ensure you have included all the required statements and declarations and uploaded any additional supplementary files (including reporting guidelines where relevant).

Please indicate if you are submitting a manuscript for a special collection. Information about open calls for special collections can be found here: https://journals.sagepub.com/gqn/open-special-collections

To facilitate an anonymized review process, no author names, initials, or other identifying information should appear anywhere in the manuscript; however, this information is needed by the Editor. In a “title page” separate from the manuscript, include the following information, in this order:

- Manuscript title

- Author names as they should appear, and in the same order in which they should appear, in the published article

- Affiliation information for each author, to include only the following: (a) thehighest-level institution (e.g., university); (b) the city in which the institution is located; (c) the state or province (if any); and (d)the country [Note: Use “USA” for the United States]

- Name and complete mailing address (including country) of the corresponding author

- Preferred email address of the corresponding author

- A biographical statement for each author, in order. Follow the template below in preparing the bios, and be sure to include all required elements (name, credentials, title or role, affiliation, city, state/province/territory [if any], country):

- Joan L. Bottorff, RN, PhD, FCAHS, FAAN is a professor at the University of British Columbia, Faculty of Health and Social Development, School of Nursing in Kelowna, British Columbia, Canada.

As part of our commitment to ensuring an ethical, transparent and fair peer review process SAGE is a supporting member of ORCID, the Open Researcher and Contributor ID . ORCID provides a unique and persistent digital identifier that distinguishes researchers from every other researcher, even those who share the same name, and, through integration in key research workflows such as manuscript and grant submission, supports automated linkages between researchers and their professional activities, ensuring that their work is recognized.

The collection of ORCID iDs from corresponding authors is now part of the submission process of this journal. If you already have an ORCID iD you will be asked to associate that to your submission during the online submission process. We also strongly encourage all co-authors to link their ORCID ID to their accounts in our online peer review platforms. It takes seconds to do: click the link when prompted, sign into your ORCID account and our systems are automatically updated. Your ORCID iD will become part of your accepted publication’s metadata, making your work attributable to you and only you. Your ORCID iD is published with your article so that fellow researchers reading your work can link to your ORCID profile and from there link to your other publications.

If you do not already have an ORCID iD please follow this link to create one or visit our ORCID homepage to learn more.

7.4 Permissions

Authors are responsible for obtaining permission from copyright holders for reproducing any illustrations, tables, figures or lengthy quotations previously published elsewhere. For further information including guidance on fair dealing for criticism and review, please visit our Frequently Asked Questions on the SAGE Journal Author Gateway . Please do not address permission and copyright questions to the journal office.

8. On acceptance and publication

If your paper is accepted for publication after peer review, you will first be asked to complete the contributor’s publishing agreement. Once your manuscript files have been check for SAGE Production, the corresponding author will be asked to pay the article processing charge (APC) via a payment link. Once the APC has been processed, your article will be prepared for publication and can appear online within an average of 30 days. Please note that no production work will occur on your paper until the APC has been received.

8.1 SAGE Production

Your SAGE Production Editor will keep you informed as to your article’s progress throughout the production process. Proofs will be sent by PDF to the corresponding author and should be returned promptly. Authors are reminded to check their proofs carefully to confirm that all author information, including names, affiliations, sequence and contact details are correct, and that Funding and Conflict of Interest statements, if any, are accurate. Please note that if there are any changes to the author list at this stage all authors will be required to complete and sign a form authorizing the change.

8.2 Online publication

One of the many benefits of publishing your research in an open access journal is the speed to publication. Your article will be published online in a fully citable form with a DOI number as soon as it has completed the production process. At this time it will be completely free to view and download for all.

8.3 Promoting your article

Publication is not the end of the process! You can help disseminate your paper and ensure it is as widely read and cited as possible. The SAGE Author Gateway has numerous resources to help you promote your work. Visit the Promote Your Article page on the Gateway for tips and advice.

9. Further information

Any correspondence, queries or additional requests for information on the Manuscript Submission process should be sent to the Global Qualitative Nursing Research Publishing Editor as follows: Lorianne Sarsfield

Email: [email protected]

- Read Online

- Current Issue

- Email Alert

- Permissions

- Foreign rights

- Reprints and sponsorship

- Advertising

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 15, Issue 1

- Qualitative data analysis

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Correspondence to Kate Seers RCN Research Institute, School of Health & Social Studies, University of Warwick, Coventry, CV4 7AL, Warwick, UK; kate.seers{at}warwick.ac.uk

https://doi.org/10.1136/ebnurs.2011.100352

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Good qualitative research uses a systematic and rigorous approach that aims to answer questions concerned with what something is like (such as a patient experience), what people think or feel about something that has happened, and it may address why something has happened as it has. Qualitative data often takes the form of words or text and can include images.

Qualitative research covers a very broad range of philosophical underpinnings and methodological approaches. Each has its own particular way of approaching all stages of the research process, including analysis, and has its own terms and techniques, but there are some common threads that run across most of these approaches. This Research Made Simple piece will focus on some of these common threads in the analysis of qualitative research.

So you have collected all your qualitative data – you may have a pile of interview transcripts, field-notes, documents and notes from observation. The process of analysis is described by Richards and Morse 1 as one of transformation and interpretation.

It is easy to be overwhelmed by the volume of data – novice qualitative researchers are sometimes told not to worry and the themes will emerge from the data. This suggests some sort of epiphany, (which is how it happens sometimes!) but generally it comes from detailed work and reflection on the data and what it is telling you. There is sometimes a fine line between being immersed in the data and drowning in it!

A first step is to sort and organise the data, by coding it in some way. For example, you could read through a transcript, and identify that in one paragraph a patient is talking about two things; first is fear of surgery and second is fear of unrelieved pain. The codes for this paragraph could be ‘fear of surgery’ and ‘fear of pain’. In other areas of the transcript fear may arise again, and perhaps these codes will be merged into a category titled ‘fear’. Other concerns may emerge in this and other transcripts and perhaps best be represented by the theme ‘lack of control’. Themes are thus more abstract concepts, reflecting your interpretation of patterns across your data. So from codes, categories can be formed, and from categories, more encompassing themes are developed to describe the data in a form which summarises it, yet retains the richness, depth and context of the original data. Using quotations to illustrate categories and themes helps keep the analysis firmly grounded in the data. You need to constantly ask yourself ‘what is happening here?’ as you code and move from codes, to categories and themes, making sure you have data to support your decisions. Analysis inevitably involves subjective choices, and it is important to document what you have done and why, so a clear audit trail is provided. The coding example above describes codes inductively coming from the data. Some researchers may use a coding framework derived from, for example, the literature, their research questions or interview prompts, (Ritchie and Spencer 2 ) or a combination of both approaches.

Qualitative data, such as transcripts from an interview, are often routed in the interaction between the participant and the researcher. Reflecting on how you, as a researcher, may have influenced both the data collected and the analysis is an important part of the analysis.

As well as keeping your brain very much in gear, you need to be really organised. You may use highlighting pens and paper to keep track of your analysis, or use qualitative software to manage your data (such as NVivio or Atlas Ti). These programmes help you organise your data – you still have to do all the hard work to analyse it! Whatever you choose, it is important that you can trace your data back from themes to categories to codes. There is nothing more frustrating than looking for that illustrative patient quote, and not being able to find it.

If your qualitative data are part of a mixed methods study, (has both quantitative and qualitative data) careful thought has to be given to how you will analyse and present findings. Refer to O’Caithain et al 3 for more details.

There are many books and papers on qualitative analysis, a very few of which are listed below. 4 , – , 6 Working with someone with qualitative expertise is also invaluable, as you can read about it, but doing it really brings it alive.

- Richards L ,

- Ritchie J ,

- O'Cathain ,

- Bradley EH ,

- Huberman AM

Competing interests None.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- Open access

- Published: 27 May 2020

How to use and assess qualitative research methods

- Loraine Busetto ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9228-7875 1 ,

- Wolfgang Wick 1 , 2 &

- Christoph Gumbinger 1

Neurological Research and Practice volume 2 , Article number: 14 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

679k Accesses

264 Citations

88 Altmetric

Metrics details

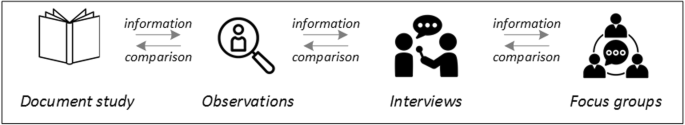

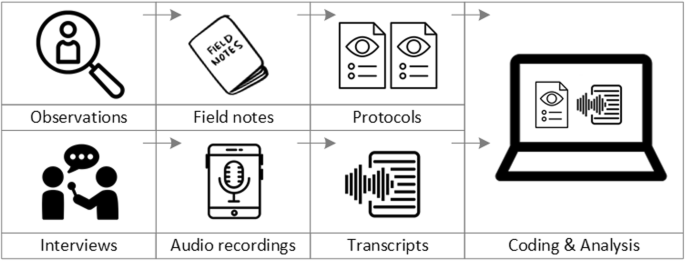

This paper aims to provide an overview of the use and assessment of qualitative research methods in the health sciences. Qualitative research can be defined as the study of the nature of phenomena and is especially appropriate for answering questions of why something is (not) observed, assessing complex multi-component interventions, and focussing on intervention improvement. The most common methods of data collection are document study, (non-) participant observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups. For data analysis, field-notes and audio-recordings are transcribed into protocols and transcripts, and coded using qualitative data management software. Criteria such as checklists, reflexivity, sampling strategies, piloting, co-coding, member-checking and stakeholder involvement can be used to enhance and assess the quality of the research conducted. Using qualitative in addition to quantitative designs will equip us with better tools to address a greater range of research problems, and to fill in blind spots in current neurological research and practice.

The aim of this paper is to provide an overview of qualitative research methods, including hands-on information on how they can be used, reported and assessed. This article is intended for beginning qualitative researchers in the health sciences as well as experienced quantitative researchers who wish to broaden their understanding of qualitative research.

What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is defined as “the study of the nature of phenomena”, including “their quality, different manifestations, the context in which they appear or the perspectives from which they can be perceived” , but excluding “their range, frequency and place in an objectively determined chain of cause and effect” [ 1 ]. This formal definition can be complemented with a more pragmatic rule of thumb: qualitative research generally includes data in form of words rather than numbers [ 2 ].

Why conduct qualitative research?

Because some research questions cannot be answered using (only) quantitative methods. For example, one Australian study addressed the issue of why patients from Aboriginal communities often present late or not at all to specialist services offered by tertiary care hospitals. Using qualitative interviews with patients and staff, it found one of the most significant access barriers to be transportation problems, including some towns and communities simply not having a bus service to the hospital [ 3 ]. A quantitative study could have measured the number of patients over time or even looked at possible explanatory factors – but only those previously known or suspected to be of relevance. To discover reasons for observed patterns, especially the invisible or surprising ones, qualitative designs are needed.

While qualitative research is common in other fields, it is still relatively underrepresented in health services research. The latter field is more traditionally rooted in the evidence-based-medicine paradigm, as seen in " research that involves testing the effectiveness of various strategies to achieve changes in clinical practice, preferably applying randomised controlled trial study designs (...) " [ 4 ]. This focus on quantitative research and specifically randomised controlled trials (RCT) is visible in the idea of a hierarchy of research evidence which assumes that some research designs are objectively better than others, and that choosing a "lesser" design is only acceptable when the better ones are not practically or ethically feasible [ 5 , 6 ]. Others, however, argue that an objective hierarchy does not exist, and that, instead, the research design and methods should be chosen to fit the specific research question at hand – "questions before methods" [ 2 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. This means that even when an RCT is possible, some research problems require a different design that is better suited to addressing them. Arguing in JAMA, Berwick uses the example of rapid response teams in hospitals, which he describes as " a complex, multicomponent intervention – essentially a process of social change" susceptible to a range of different context factors including leadership or organisation history. According to him, "[in] such complex terrain, the RCT is an impoverished way to learn. Critics who use it as a truth standard in this context are incorrect" [ 8 ] . Instead of limiting oneself to RCTs, Berwick recommends embracing a wider range of methods , including qualitative ones, which for "these specific applications, (...) are not compromises in learning how to improve; they are superior" [ 8 ].

Research problems that can be approached particularly well using qualitative methods include assessing complex multi-component interventions or systems (of change), addressing questions beyond “what works”, towards “what works for whom when, how and why”, and focussing on intervention improvement rather than accreditation [ 7 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Using qualitative methods can also help shed light on the “softer” side of medical treatment. For example, while quantitative trials can measure the costs and benefits of neuro-oncological treatment in terms of survival rates or adverse effects, qualitative research can help provide a better understanding of patient or caregiver stress, visibility of illness or out-of-pocket expenses.

How to conduct qualitative research?

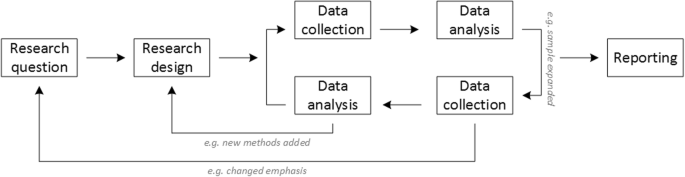

Given that qualitative research is characterised by flexibility, openness and responsivity to context, the steps of data collection and analysis are not as separate and consecutive as they tend to be in quantitative research [ 13 , 14 ]. As Fossey puts it : “sampling, data collection, analysis and interpretation are related to each other in a cyclical (iterative) manner, rather than following one after another in a stepwise approach” [ 15 ]. The researcher can make educated decisions with regard to the choice of method, how they are implemented, and to which and how many units they are applied [ 13 ]. As shown in Fig. 1 , this can involve several back-and-forth steps between data collection and analysis where new insights and experiences can lead to adaption and expansion of the original plan. Some insights may also necessitate a revision of the research question and/or the research design as a whole. The process ends when saturation is achieved, i.e. when no relevant new information can be found (see also below: sampling and saturation). For reasons of transparency, it is essential for all decisions as well as the underlying reasoning to be well-documented.

Iterative research process

While it is not always explicitly addressed, qualitative methods reflect a different underlying research paradigm than quantitative research (e.g. constructivism or interpretivism as opposed to positivism). The choice of methods can be based on the respective underlying substantive theory or theoretical framework used by the researcher [ 2 ].

Data collection

The methods of qualitative data collection most commonly used in health research are document study, observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups [ 1 , 14 , 16 , 17 ].

Document study

Document study (also called document analysis) refers to the review by the researcher of written materials [ 14 ]. These can include personal and non-personal documents such as archives, annual reports, guidelines, policy documents, diaries or letters.

Observations