A Guide to Lyric Essay Writing: 4 Evocative Essays and Prompts to Learn From

Poets can learn a lot from blurring genres. Whether getting inspiration from fiction proves effective in building characters or song-writing provides a musical tone, poetry intersects with a broader literary landscape. This shines through especially in lyric essays, a form that has inspired articles from the Poetry Foundation and Purdue Writing Lab , as well as become the concept for a 2015 anthology titled We Might as Well Call it the Lyric Essay.

Put simply, the lyric essay is a hybrid, creative nonfiction form that combines the rich figurative language of poetry with the longer-form analysis and narrative of essay or memoir. Oftentimes, it emerges as a way to explore a big-picture idea with both imagery and rigor. These four examples provide an introduction to the writing style, as well as spotlight tips for creating your own.

1. Draft a “braided essay,” like Michelle Zauner in this excerpt from Crying in H Mart .

Before Crying in H Mart became a bestselling memoir, Michelle Zauner—a writer and frontwoman of the band Japanese Breakfast—published an essay of the same name in The New Yorker . It opens with the fascinating and emotional sentence, “Ever since my mom died, I cry in H Mart.” This first line not only immediately propels the reader into Zauner’s grief, but it also reveals an example of the popular “braided essay” technique, which weaves together two distinct but somehow related experiences.

Throughout the work, Zauner establishes a parallel between her and her mother’s relationship and traditional Korean food. “You’ll likely find me crying by the banchan refrigerators, remembering the taste of my mom’s soy-sauce eggs and cold radish soup,” Zauner writes, illuminating the deeply personal and mystifying experience of grieving through direct, sensory imagery.

2. Experiment with nonfiction forms , like Hadara Bar-Nadav in “ Selections from Babyland . ”

Lyric essays blend poetic qualities and nonfiction qualities. Hadara Bar-Nadav illustrates this experimental nature in Selections from Babyland , a multi-part lyric essay that delves into experiences with infertility. Though Bar-Nadav’s writing throughout this piece showcases rhythmic anaphora—a definite poetic skill—it also plays with nonfiction forms not typically seen in poetry, including bullet points and a multiple-choice list.

For example, when recounting unsolicited advice from others, Bar-Nadav presents their dialogue in the following way:

I heard about this great _____________.

a. acupuncturist

b. chiropractor

d. shamanic healer

e. orthodontist ( can straighter teeth really make me pregnant ?)

This unexpected visual approach feels reminiscent of an article or quiz—both popular nonfiction forms—and adds dimension and white space to the lyric essay.

3. Travel through time , like Nina Boutsikaris in “ Some Sort of Union .”

Nina Boutsikaris is the author of I’m Trying to Tell You I’m Sorry: An Intimacy Triptych , and her work has also appeared in an anthology of the best flash nonfiction. Her essay “Some Sort of Union,” published in Hippocampus Magazine , was a finalist in the magazine’s Best Creative Nonfiction contest.

Since lyric essays are typically longer and more free verse than poems, they can be a way to address a larger idea or broader time period. Boutsikaris does this in “Some Sort of Union,” where the speaker drifts from an interaction with a romantic interest to her childhood.

“They were neighbors, the girl and the air force paramedic. She could have seen his front door from her high-rise window if her window faced west rather than east,” Boutsikaris describes. “When she first met him two weeks ago, she’d been wearing all white, buying a wedge of cheap brie at the corner market.”

In the very next paragraph, Boutskiras shifts this perspective and timeline, writing, “The girl’s mother had been angry with her when she was a child. She had needed something from the girl that the girl did not know how to give. Not the way her mother hoped she would.”

As this example reveals, examining different perspectives and timelines within a lyric essay can flesh out a broader understanding of who a character is.

4. Bring in research, history, and data, like Roxane Gay in “ What Fullness Is .”

Like any other form of writing, lyric essays benefit from in-depth research. And while journalistic or scientific details can sometimes throw off the concise ecosystem and syntax of a poem, the lyric essay has room for this sprawling information.

In “What Fullness Is,” award-winning writer Roxane Gay contextualizes her own ideas and experiences with weight loss surgery through the history and culture surrounding the procedure.

“The first weight-loss surgery was performed during the 10th century, on D. Sancho, the king of León, Spain,” Gay details. “He was so fat that he lost his throne, so he was taken to Córdoba, where a doctor sewed his lips shut. Only able to drink through a straw, the former king lost enough weight after a time to return home and reclaim his kingdom.”

“The notion that thinness—and the attempt to force the fat body toward a state of culturally mandated discipline—begets great rewards is centuries old.”

Researching and knowing this history empowers Gay to make a strong central point in her essay.

Bonus prompt: Choose one of the techniques above to emulate in your own take on the lyric essay. Happy writing!

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

4 Poetry Collections to Read After You Listen to Kacey Musgraves’ Deeper Well

Good For a Laugh: How to Tap into Your Comedic Side in Your Writing

How to Start Your Own Poetry Instagram

In literary nonfiction, no form is quite as complicated as the lyric essay. Lyrical essays explore the elements of poetry and creative nonfiction in complex and experimental ways, combining the subject matter of autobiography with poetry’s figurative devices and musicality of language.

For both poets and creative nonfiction writers, lyric essays are a gold standard of experimentation and language, but conquering the form takes lots of practice. What is a lyric essay, and how do you write one? Let’s break down this challenging CNF form, with lyric essay examples, before examining how you might approach it yourself.

Want to explore the lyric essay further? See our lyric essay writing course with instructor Gretchen Clark.

What is a lyric essay?

The lyric essay combines the autobiographical information of a personal essay with the figurative language, forms, and experimentations of poetry. In the lyric essay, the rules of both poetry and prose become suggestions, because the form of the essay is constantly changing, adapting to the needs, ideas, and consciousness of the writer.

Lyric essay definition: The lyric essay combines autobiographical writing with the figurative language, forms, and experimentations of poetry.

Lyric essays are typically written in a poetic prose style . (We’ll expand on the difference between prose poetry and lyric essay shortly.) Lyric essays employ many of the poetic devices that poets use, including devices of repetition and rhetorical devices in literature.

That said, there are few conventions for the lyric essay, other than to experiment, experiment, experiment. While the form itself is an essay, there’s no reason you can’t break the bounds of expression.

One tactic, for example, is to incorporate poetry into the essay itself. You might start your essay with a normal paragraph, then describe something specific through a sonnet or villanelle , then express a different idea through a POV shift, a list, or some other form. Lyric essays can also borrow from the braided essay, the hermit crab, and other forms of creative nonfiction .

In truth, there’s very little that unifies all lyric essays, because they’re so wildly experimental. They’re also a bit tricky to define—the line between a lyric essay and the prose poem, in particular, is very hazy.

Rather than apply a one-size-fits-all definition for the lyric essay, which doesn’t exist, let’s pay close attention to how lyric essayists approach the open-ended form.

There are few conventions for the lyric essay, other than to experiment, experiment, experiment

Personal essay vs. lyric essay: An example of each

At its simplest, the lyric essay’s prose style is different from that of the personal essay, or other forms of creative nonfiction.

Personal essay example

Here are the opening two paragraphs from Beth Ann Fennelly’s personal essay “ I Survived the Blizzard of ’79. ”

“We didn’t question. Or complain. It wouldn’t have occurred to us, and it wouldn’t have helped. I was eight. Julie was ten.

We didn’t know yet that this blizzard would earn itself a moniker that would be silk-screened on T-shirts. We would own such a shirt, which extended its tenure in our house as a rag for polishing silver.”

The prose in this personal essay excerpt is descriptive, linear, and easy to understand. Fennelly gives us the information we need to make sense of her world, as well as the foreshadow of what’s to come in her essay.

Lyric essay example

Now, take this excerpt from a lyric essay, “ Life Code ” by J. A. Knight:

“The dream goes like this: blue room of water. God light from above. Child’s fist, foot, curve, face, the arc of an eye, the symmetry of circles… and then an opening of this body—which surprised her—a movement so clean and assured and then the push towards the light like a frog or a fish.”

The prose in Knight’s lyric essay cannot be read the same way as a personal essay might be. Here, Knight’s prose is a sort of experience—a way of exploring the dream through language as shifting and ethereal as dreams themselves. Where the personal essay transcribes experiences, the lyric essay creates them.

Where the personal essay transcribes experiences, the lyric essay creates them.

For more examples of the craft, The Seneca Review and Eastern Iowa Review both have a growing archive of lyric essays submitted to their journals. In essence, there is no form to a lyric essay—rather, form and language are experimented with interchangeably, guided only by the narrative you seek to write.

Lyric Essay Vs Prose Poem

Lyric essays are commonly confused with prose poetry . In truth, there is no clear line separating the two, and plenty of essays, including some of the lyric essay examples in this article, can also be called prose poems.

Well, what’s the difference? A prose poem, broadly defined, is a poem written in paragraphs. Unlike a traditional poem, the prose poem does not make use of line breaks: the line breaks simply occur at the end of the page. However, all other tactics of poetry are in the prose poet’s toolkit, and you can even play with poetry forms in the prose poem, such as writing the prose sonnet .

Lyric essays also blend the techniques of prose and poetry. Here are some general differences between the two:

- Lyric essays tend to be longer. A prose poem is rarely more than a page. Some lyric essays are longer than 20 pages.

- Lyric essays tend to be more experimental. One paragraph might be in prose, the next, poetry. The lyric essay might play more with forms like lists, dreams, public signs, or other types of media and text.

- Prose poems are often more stream-of-conscious. The prose poet often charts the flow of their consciousness on the page. Lyric essayists can do this, too, but there’s often a broader narrative organizing the piece, even if it’s not explicitly stated or recognizable.

The two share many similarities, too, including:

- An emphasis on language, musicality, and ambiguity.

- Rejection of “objective meaning” and the desire to set forth arguments.

- An unobstructed flow of ideas.

- Suggestiveness in thoughts and language, rather than concrete, explicit expressions.

- Surprising or unexpected juxtapositions .

- Ingenuity and play with language and form.

In short, there’s no clear dividing line between the two. Often, the label of whether a piece is a lyric essay or a prose poem is up to the writer.

Lyric Essay Examples

The following lyric essay examples are contemporary and have been previously published online. Pay attention to how the lyric essayists interweave the essay form with a poet’s attention to language, mystery, and musicality.

“Lodge: A Lyric Essay” by Emilia Phillips

Retrieved here, from Blackbird .

This lush, evocative lyric essay traverses the American landscape. The speaker reacts to this landscape finding poetry in the rundown, and seeing her own story—family trauma, religion, and the random forces that shape her childhood. Pay attention to how the essay defies conventional standards of self-expression. In between narrative paragraphs are lists, allusions, memories, and the many twists and turns that seem to accompany the narrator on their journey through Americana.

“Spiral” by Nicole Callihan

Retrieved here, from Birdcoat Quarterly .

Notice how this gorgeous essay evolves down the spine of its central theme: the sleepless swallows. The narrator records her thoughts about the passage of time, her breast examination, her family and childhood, and the other thoughts that arise in her mind as she compares them, again and again, to the mysterious swallows who fly without sleep. This piece demonstrates how lyric essays can encompass a wide array of ideas and threads, creating a kaleidoscope of language for the reader to peer into, come away with something, peer into again, and always see something different.

“Star Stuff” by Jessica Franken

Retrieved here, from Seneca Review .

This short, imagery -driven lyric essay evokes wonder at our seeming smallness, our seeming vastness. The narrator juxtaposes different ideas for what the body can become, playing with all our senses and creating odd, surprising connections. Read this short piece a few times. Ask yourself, why are certain items linked together in the same paragraph? What is the train of thought occurring in each new sentence, each new paragraph? How does the final paragraph wrap up the lyric essay, while also leaving it open ended? There’s much to interpret in this piece, so engage with it slowly, read it over several times.

5 approaches to writing the lyric essay

This form of creative writing is tough for writers because there’s no proper formula for writing it. However, if you have a passion for imaginative forms and want to rise to the challenge, here are several different ways to write your essay.

1. Start with your narrative

Writing the lyrical essay is a lot like writing creative nonfiction: it starts with getting words on the page. Start with a simple outline of the story you’re looking to write. Focus on the main plot points and what you want to explore, then highlight the ideas or events that will be most difficult for you to write about. Often, the lyrical form offers the writer a new way to talk about something difficult. Where words fail, form is key. Combining difficult ideas and musicality allows you to find the right words when conventional language hasn’t worked.

Emilia Phillips’ lyric essay “ Lodge ” does exactly this, letting the story’s form emphasize its language and the narrative Phillips writes about dreams, traveling, and childhood emotions.

2. Identify moments of metaphor and figurative language

The lyric essay is liberated from form, rather than constrained by it. In a normal essay, you wouldn’t want your piece overrun by figurative language, but here, boundless metaphors are encouraged—so long as they aid your message. For some essayists, it might help to start by reimagining your story as an extended metaphor.

A great example of this is Zadie Smith’s essay “ The Lazy River ,” which uses the lazy river as an extended metaphor to criticize a certain “go with the flow” mindset.

Use extended metaphors as a base for the essay, then return to it during moments of transition or key insight. Writing this way might help ground your writing process while giving you new opportunities to play with form.

3. Investigate and braid different threads

Just like the braided essay , lyric essays can certainly braid different story lines together. If anything, the freedom to play with form makes braiding much easier and more exciting to investigate. How can you use poetic forms to braid different ideas together? Can you braid an extended metaphor with the main story? Can you separate the threads into a contrapuntal, then reunite them in prose?

A simple example of threading in lyric essay is Jane Harrington’s “ Ossein Pith .” Harrington intertwines the “you” and “I” of the story, letting each character meet only when the story explores moments of “hunger.”

Whichever threads you choose to write, use the freedom of the lyric essay to your advantage in exploring the story you’re trying to set down.

4. Revise an existing piece into a lyric essay

Some CNF writers might find it easier to write their essay, then go back and revise with the elements of poetic form and figurative language. If you choose to take this route, identify the parts of your draft that don’t seem to be working, then consider changing the form into something other than prose.

For example, you might write a story, then realize it would greatly benefit the prose if it was written using the poetic device of anaphora (a repetition device using a word or phrase at the beginning of a line or paragraph). Chen Li’s lyric essay “ Baudelaire Street ” does a great job of this, using the anaphora “I would ride past” to explore childhood memory.

When words don’t work, let the lyrical form intervene.

5. Write stream-of-conscious

Stream-of-consciousness is a writing technique in which the writer charts, word-for-word, the exact order of their unfiltered thoughts on the page.

If it isn’t obvious, this is easier said than done. We naturally think faster than we write, and we also have a tendency to filter our thoughts as we think them, to the point where many thoughts go unconsciously unnoticed. Unlearning this takes a lot of practice and skill.

Nonetheless, you might notice in the lyric essay examples we shared how the essayists followed different associations with their words, one thought flowing naturally into the next, circling around a subject rather than explicitly defining it. The stream-of-conscious technique is perfect for this kind of writing, then, because it earnestly excavates the mind, creating a kind of Rorschach test that the reader can look into, interpret, see for themselves.

This technique requires a lot of mastery, but if you’re keen on capturing your own consciousness, you may find that the lyric essay form is the perfect container to hold it in.

Closing thoughts on the lyric essay form

Creative nonfiction writers have an overt desire to engage their readers with insightful stories. When language fails, the lyrical essay comes to the rescue. Although this is a challenging form to master, practicing different forms of storytelling could pave new avenues for your next nonfiction piece. Try using one of these different ways to practice the lyric craft, and get writing your next CNF story!

[…] Sean “Writing Your Truth: Understanding the Lyric Essay.” writers.com. https://writers.com/understanding-the-lyric-essay published 19 May, 2020/ accessed 13 Oct, […]

[…] https://writers.com/understanding-the-lyric-essay […]

I agree with every factor that you have pointed out. Thank you for sharing your beautiful thoughts on this. A personal essay is writing that shares an interesting, thought-provoking, sometimes entertaining, and humorous piece that is often drawn from the writer’s personal experience and at times drawn from the current affairs of the world.

[…] been wanting to learn more about lyric essay, and this seems a natural transition from […]

thanks for sharing

Thanks so much for this. Here is an updated link to my essay Spiral: https://www.birdcoatquarterly.com/post/nicole-callihan

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

An Introduction to the Lyric Essay

Rebecca Hussey

Rebecca holds a PhD in English and is a professor at Norwalk Community College in Connecticut. She teaches courses in composition, literature, and the arts. When she’s not reading or grading papers, she’s hanging out with her husband and son and/or riding her bike and/or buying books. She can't get enough of reading and writing about books, so she writes the bookish newsletter "Reading Indie," focusing on small press books and translations. Newsletter: Reading Indie Twitter: @ofbooksandbikes

View All posts by Rebecca Hussey

Essays come in a bewildering variety of shapes and forms: they can be the five paragraph essays you wrote in school — maybe for or against gun control or on symbolism in The Great Gatsby . Essays can be personal narratives or argumentative pieces that appear on blogs or as newspaper editorials. They can be funny takes on modern life or works of literary criticism. They can even be book-length instead of short. Essays can be so many things!

Perhaps you’ve heard the term “lyric essay” and are wondering what that means. I’m here to help.

What is the Lyric Essay?

A quick definition of the term “lyric essay” is that it’s a hybrid genre that combines essay and poetry. Lyric essays are prose, but written in a manner that might remind you of reading a poem.

Before we go any further, let me step back with some more definitions. If you want to know the difference between poetry and prose, it’s simply that in poetry the line breaks matter, and in prose they don’t. That’s it! So the lyric essay is prose, meaning where the line breaks fall doesn’t matter, but it has other similarities to what you find in poems.

Thank you for signing up! Keep an eye on your inbox. By signing up you agree to our terms of use

Lyric essays have what we call “poetic” prose. This kind of prose draws attention to its own use of language. Lyric essays set out to create certain effects with words, often, although not necessarily, aiming to create beauty. They are often condensed in the way poetry is, communicating depth and complexity in few words. Chances are, you will take your time reading them, to fully absorb what they are trying to say. They may be more suggestive than argumentative and communicate multiple meanings, maybe even contradictory ones.

Lyric essays often have lots of white space on their pages, as poems do. Sometimes they use the space of the page in creative ways, arranging chunks of text differently than regular paragraphs, or using only part of the page, for example. They sometimes include photos, drawings, documents, or other images to add to (or have some other relationship to) the meaning of the words.

Lyric essays can be about any subject. Often, they are memoiristic, but they don’t have to be. They can be philosophical or about nature or history or culture, or any combination of these things. What distinguishes them from other essays, which can also be about any subject, is their heightened attention to language. Also, they tend to deemphasize argument and carefully-researched explanations of the kind you find in expository essays . Lyric essays can argue and use research, but they are more likely to explore and suggest than explain and defend.

Now, you may be familiar with the term “ prose poem .” Even if you’re not, the term “prose poem” might sound exactly like what I’m describing here: a mix of poetry and prose. Prose poems are poetic pieces of writing without line breaks. So what is the difference between the lyric essay and the prose poem?

Honestly, I’m not sure. You could call some pieces of writing either term and both would be accurate. My sense, though, is that if you put prose and poetry on a continuum, with prose on one end and poetry on the other, and with prose poetry and the lyric essay somewhere in the middle, the prose poem would be closer to the poetry side and the lyric essay closer to the prose side.

Some pieces of writing just defy categorization, however. In the end, I think it’s best to call a work what the author wants it to be called, if it’s possible to determine what that is. If not, take your best guess.

Four Examples of the Lyric Essay

Below are some examples of my favorite lyric essays. The best way to learn about a genre is to read in it, after all, so consider giving one of these books a try!

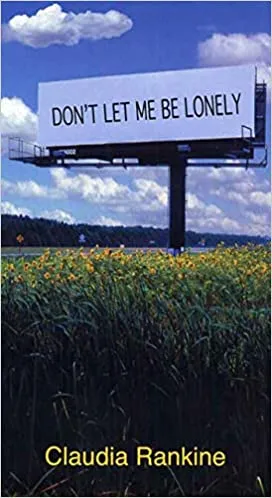

Don’t Let Me Be Lonely: An American Lyric by Claudia Rankine

Claudia Rankine’s book Citizen counts as a lyric essay, but I want to highlight her lesser-known 2004 work. In Don’t Let Me Be Lonely , Rankine explores isolation, depression, death, and violence from the perspective of post-9/11 America. It combines words and images, particularly television images, to ponder our relationship to media and culture. Rankine writes in short sections, surrounded by lots of white space, that are personal, meditative, beautiful, and achingly sad.

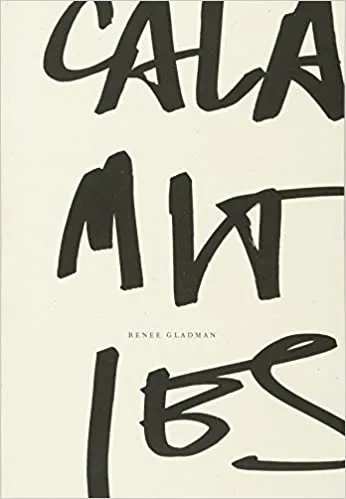

Calamities by Renee Gladman

Calamities is a collection of lyric essays exploring language, imagination, and the writing life. All of the pieces, up until the last 14, open with “I began the day…” and then describe what she is thinking and experiencing as a writer, teacher, thinker, and person in the world. Many of the essays are straightforward, while some become dreamlike and poetic. The last 14 essays are the “calamities” of the title. Together, the essays capture the artistic mind at work, processing experience and slowly turning it into writing.

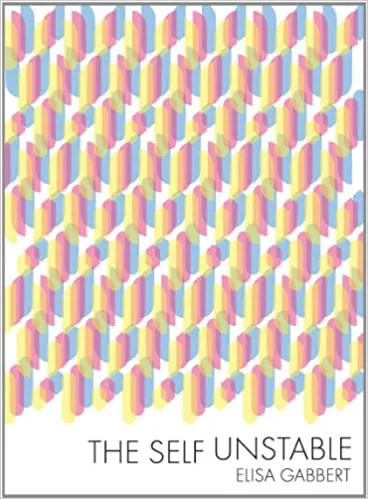

The Self Unstable by Elisa Gabbert

The Self Unstable is a collection of short essays — or are they prose poems? — each about the length of a paragraph, one per page. Gabbert’s sentences read like aphorisms. They are short and declarative, and part of the fun of the book is thinking about how the ideas fit together. The essays are divided into sections with titles such as “The Self is Unstable: Humans & Other Animals” and “Enjoyment of Adversity: Love & Sex.” The book is sharp, surprising, and delightful.

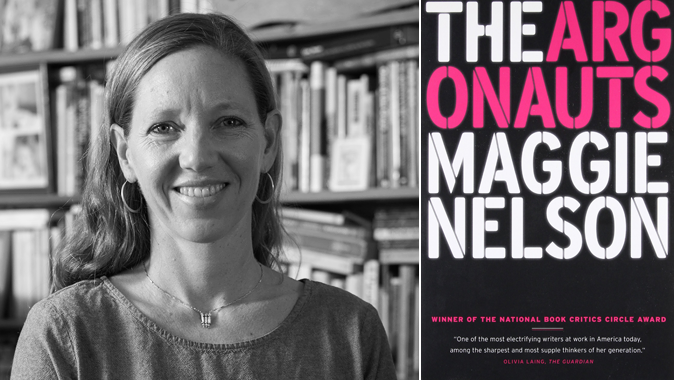

Bluets by Maggie Nelson

Bluets is made up of short essayistic, poetic paragraphs, organized in a numbered list. Maggie Nelson’s subjects are many and include the color blue, in which she finds so much interest and meaning it will take your breath away. It’s also about suffering: she writes about a friend who became a quadriplegic after an accident, and she tells about her heartbreak after a difficult break-up. Bluets is meditative and philosophical, vulnerable and personal. It’s gorgeous, a book lovers of The Argonauts shouldn’t miss.

It’s probably no surprise that all of these books are published by small presses. Lyric essays are weird and genre-defying enough that the big publishers generally avoid them. This is just one more reason, among many, to read small presses!

If you’re looking for more essay recommendations, check out our list of 100 must-read essay collections and these 25 great essays you can read online for free .

You Might Also Like

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Lyric Essays

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

These resources discuss some terms and techniques that are useful to the beginning and intermediate creative nonfiction writer, and to instructors who are teaching creative nonfiction at these levels. The distinction between beginning and intermediate writing is provided for both students and instructors, and numerous sources are listed for more information about creative nonfiction tools and how to use them. A sample assignment sheet is also provided for instructors.

Because the lyric essay is a new, hybrid form that combines poetry with essay, this form should be taught only at the intermediate to advanced levels. Even professional essayists aren’t certain about what constitutes a lyric essay, and lyric essays disagree about what makes up the form. For example, some of the “lyric essays” in magazines like The Seneca Review have been selected for the Best American Poetry series, even though the “poems” were initially published as lyric essays.

A good way to teach the lyric essay is in conjunction with poetry (see the Purdue OWL's resource on teaching Poetry in Writing Courses ). After students learn the basics of poetry, they may be prepared to learn the lyric essay. Lyric essays are generally shorter than other essay forms, and focus more on language itself, rather than storyline. Contemporary author Sherman Alexie has written lyric essays, and to provide an example of this form, we provide an excerpt from his Captivity :

"He (my captor) gave me a biscuit, which I put in my

pocket, and not daring to eat it, buried it under a log, fear-

ing he had put something in it to make me love him.

FROM THE NARRATIVE OF MRS. MARY ROWLANDSON,

WHO WAS TAKEN CAPTIVE WHEN THE WAMPANOAG

DESTROYED LANCASTER, MASSACHUSETS, IN 1676"

"I remember your name, Mary Rowlandson. I think of you now, how necessary you have become. Can you hear me, telling this story within uneasy boundaries, changing you into a woman leaning against a wall beneath a HANDICAPPED PARKING ONLY sign, arrow pointing down directly at you? Nothing changes, neither of us knows exactly where to stand and measure the beginning of our lives. Was it 1676 or 1976 or 1776 or yesterday when the Indian held you tight in his dark arms and promised you nothing but the sound of his voice?"

Alexie provides no straightforward narrative here, as in a personal essay; in fact, each numbered section is only loosely related to the others. Alexie doesn’t look into his past, as memoirists do. Rather, his lyric essay is a response to a quote he found, and which he uses as an epigraph to his essay.

Though the narrator’s voice seems to be speaking from the present, and addressing a woman who lived centuries ago, we can’t be certain that the narrator’s voice is Alexie’s voice. Is Alexie creating a narrator or persona to ask these questions? The concept and the way it’s delivered is similar to poetry. Poets often use epigraphs to write poems. The difference is that Alexie uses prose language to explore what this epigraph means to him.

Course Syllabus

Writing the Lyric Essay: When Poetry & Nonfiction Play

Experiment with form and explore the possibilities of this flexible genre..

Some of the most artful work being done in essay today exists in a liminal space that touches on the poetic. In this course, you will read and write lyric essays (pieces of creative nonfiction that move in ways often associated with poetry) using techniques such as juxtaposition; collage; white space; attention to sound; and loose, associative thinking. You will read lyric essays that experiment with form and genre in a variety of ways (such as the hermit crab essay, the braided essay, multimedia work), as well as hybrid pieces by authors working very much at the intersection of essay and poetry. We will proceed in this course with an attitude of play, openness, and communal exploration into the possibilities of the lyric essay, reaching for our own definitions and methods, even as we study the work of others for models and inspiration. Whether you are an aspiring essayist interested in infusing your work with fresh new possibilities, or a poet who wants to try essay, this course will have room for you to experiment and play.

How it works:

Each week provides:

- discussions of assigned readings and other general writing topics with peers and the instructor

- written lectures and a selection of readings

Some weeks also include:

- the opportunity to submit two essays of 1000 and 2500 words each for instructor and/or peer review

- additional optional writing exercises

- an optional video conference that is open to all students(and which will be available afterward as a recording for those who cannot participate)

Aside from the live conference, there is no need to be online at any particular time of day. To create a better classroom experience for all, you are expected to participate weekly in class discussions to receive instructor feedback.

Week 1: Lyric Models: Space and Collage

In this first week, we’ll consider definitions and models for the lyric essay. You will read contemporary pieces that straddle the line between personal essay and poem, including work by Toi Derricotte, Anne Carson, and Maggie Nelson. In exercises, you will explore collage and the use of white space.

Week 2: Experiments with Form: Braided Essay and Hermit Crab Essay

We will build on our discussion of collage and white space, looking at examples of the braided essay. We’ll also examine the hermit crab essay, in which writers “sneak” personal essays into other forms, such as a job letter, shopping list, or how-to manual. You’ll experiment with your own braided pieces and hermit crab pieces and turn in the first assignment.

Week 3: Lyric Vignette and the Prose Poem

Prose poems will often capture emotional truths using juxtaposition, hyperbole, and absurd or surreal leaps of logic. This week, we’ll investigate how lyrical vignettes can stay true to actual events while employing some of the lyrical, dreamlike, and/or absurd qualities of the prose poem to communicate the wonder and mystery of life.

Week 4: Witnessing the Self: Essays by Poets

Poet Larry Levis has written of the poet as witness, as temporarily emptied of personality but simultaneously connected to a self, a “gazer.” Personal essays by poets retain something of this quality. Examining essays by poets such as Ross Gay, Lucia Perillo, Amy Gerstler, and Elizabeth Bishop, we’ll look at moments of connection and disconnection. Guided exercises will help you find and craft your own such moments.

Week 5: Hybrid Forms and the Documentary Impulse

As we wrap up the course, we will continue investigating the possibilities inherent in straddling and combining genres as we explore multimedia work, as well as work in the “documentary poetics” vein. We will look to writers like Claudia Rankine and Bernadette Mayer, Roz Chast and Maira Kalman for models of what is possible creatively when we observe ourselves as social beings moving through time, collecting text, images, and observations. Students will also turn in a final essay.

Vise and Shadow

Essays on the lyric imagination, poetry, art, and culture.

Peter Balakian

224 pages | 6 color plates, 2 halftones | 5 1/2 x 8 1/2 | © 2015

History: General History

Literature and Literary Criticism: General Criticism and Critical Theory

- Table of contents

- Author Events

Related Titles

"Here are the burdens of literature. Here is the perpetual wandering of ideas that have found a good home. Every chapter is an awakening. Every reflection, something not heard before."

Grace Cavalieri | Washington Independent Review of Books

“While Balakian’s essays [ Vise and Shadow ] reveal the ways history and its discontents inscribe themselves in the smallest features of familiar texts, his poems [ Ozone Journal ] offer a mournful silence in the face of these social upheavals, and their aftermath, that is only possible within the realm of art. Readers will find both texts equally necessary and equally moving.”

Kristina Marie Darling | Colorado Review

“Peter Balakian is the preeminent Armenian writer in English today, whether the genre is poetry (Ziggurat , Ozone Journal ), memoir ( Black Dog of Fate ), history ( The Burning Tigris ), or, as in the present case, cultural criticism. . . . [ Vise and Shadow ] offer[s] new insights into the relationships between trauma, memory, and aesthetic form . . . by exploring two dimensions of the lyric imagination in poetry, art, and culture.”

Keith Garebian | World Literature Today

" Vise and Shadow stands as an important contribution to the ongoing dialog about culture, modernity, and memory."

“Few American poets of the boomer generation have explored the interstices of public and personal history as deeply and urgently as has Balakian, and his significance as a poet of social consciousness is complemented by his work in other genres.”

David Wojahn | Tikkun

" Vise and Shadow belongs on a shelf alongside the literary essays of J. M. Coetzee, Adrienne Rich, and Seamus Heaney--all of whom are absorbed by the very same questions haunting and inspiring Balakian."

Askold Melnyczuk, author of The House of Widows

"With soaring critical erudition, Peter Balakian’s essays range across multiple genres--poetry, memoir, film, visual art, history, ’literary rock’--to create a brilliant collage of both American imagination and Armenian memory. An elegantly written, seminal work of sweeping importance."

James Carroll, author of An American Requiem

Table of Contents

Romantic things.

Mary Jacobus

A Transnational Poetics

Jahan Ramazani

Pitch of Poetry

Charles Bernstein

Strange Footing

Seeta Chaganti

Be the first to know

Get the latest updates on new releases, special offers, and media highlights when you subscribe to our email lists!

Sign up here for updates about the Press

10 of the Best Examples of the Lyric Poem

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

A lyric poem is a (usually short) poem detailing the thoughts or feelings of the poem’s speaker. Originally, lyric poems, as the name suggests, were sung and accompanied by the lyre , a stringed instrument not unlike a harp. Even today, we often use the term ‘lyricism’ to denote a certain harmony or musicality in poetry. Below, we introduce ten of the greatest short lyric poems written in English from the Middle Ages to the present day.

1. Anonymous, ‘Fowls in the Frith’.

We begin our whistle-stop tour of the lyric poem in the thirteenth century, a whole century before Geoffrey Chaucer, with this intriguing and ambiguous anonymous five-line lyric:

Foulës in the frith, The fishës in the flod, And I mon waxë wod; Much sorwe I walkë with For beste of bon and blod.

A ‘frith’ is a wood or forest; the poem, written in Middle English, features a speaker who, he tells us, ‘mon waxë wod’ (i.e. must go mad) because of the sorrow he walks with.

Because the last line is ambiguous (‘the best of bone and blood’ could refer to a woman or to Christ), the poem can be read either as a love lyric or as a religious lyric.

We have gathered together more classic medieval lyrics here .

2. Sir Thomas Wyatt, ‘ Whoso List to Hunt ’.

Whoso list to hunt, I know where is an hind, But as for me, hélas , I may no more. The vain travail hath wearied me so sore, I am of them that farthest cometh behind …

One of the most popular and enduring lyric forms has been the sonnet: 14 lines (usually), in which the poet expresses their thoughts and feelings about love, death, or some other theme. In the English or ‘Shakespearean’ sonnet the poet usually brings their ‘argument’ to a conclusion in the final rhyming couplet.

Here, however, Sir Thomas Wyatt offers an Italian or Petrarchan sonnet, but he introduces the distinctive ‘English’ conclusion: that rhyming couplet. In a loose translation of a fourteenth-century sonnet by Petrarch, Wyatt (1503-42) describes leaving off his ‘hunt’ for a ‘hind’ – in a lyric poem that was possibly a coded reference to his own relationship with Anne Boleyn.

3. Robert Herrick, ‘ Upon Julia’s Clothes ’.

Whenas in silks my Julia goes, Then, then, methinks, how sweetly flows The liquefaction of her clothes …

This very short lyric poem, by one of England’s foremost Cavalier poets of the seventeenth century, is deceptively simple. It seems to be simply a description of the woman’s silken clothing, and its pleasure-inducing effects on our poet.

But the poem seems to hint at far more than this, as we’ve explored in the analysis that follows the poem (in the link provided above). It might be described as one of the finest erotic lyric poems of the early modern period.

4. Emily Dickinson, ‘ The Heart Asks Pleasure First ’.

The Heart asks Pleasure – first – And then – Excuse from Pain – And then – those little Anodynes That deaden suffering …

So begins this short lyric poem from the prolific nineteenth-century American poet Emily Dickinson (1830-86).

The poem examines what one’s ‘heart’ most desires: a common theme in lyric poetry. The heart desires pleasure, but failing that, will settle for being excused from pain, and to live a life without suffering pain.

5. Charlotte Mew, ‘ A Quoi bon Dire ’.

Charlotte Mew (1869-1928) was a popular poet in her lifetime, and was admired by fellow poets Ezra Pound and Thomas Hardy. ‘A Quoi Bon Dire’ was published in Charlotte Mew’s 1916 volume The Farmer’s Bride . The French title of this poem translates as ‘what good is there to say’. And what good is there to say about this short poem? We think it’s a beautiful example of early twentieth-century lyricism:

Seventeen years ago you said Something that sounded like Good-bye; And everybody thinks that you are dead …

Follow the link above to read this tender lyric poem in full.

6. W. B. Yeats, ‘ He Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven ’.

Had I the heavens’ embroidered cloths, Enwrought with golden and silver light, The blue and the dim and the dark cloths Of night and light and the half light …

The gist of this poem, one of Yeats’s most popular short lyric poems, is straightforward: if I were a rich man, I’d give you the world and all its treasures. If I were a god, I could take the heavenly sky and make a blanket out of it for you.

But I’m only a poor man, and obviously the idea of making the sky into a blanket is silly and out of the question, so all I have of any worth are my dreams. And dreams are delicate and vulnerable – hence ‘Tread softly’. But Yeats, using his distinctive lyricism, puts it better than this paraphrase can convey.

7. T. E. Hulme, ‘ Autumn ’.

A touch of cold in the Autumn night – I walked abroad, And saw the ruddy moon lean over a hedge Like a red-faced farmer …

This short poem by arguably the first modern poet in English was written in 1908; it’s a short imagist lyric in free verse about a brief encounter with the autumn (i.e. harvest) moon. This poem earns its place on this list of great lyric poems because of the originality of the image at its centre: that of comparing the ‘ruddy moon’ to a … well, we’ll let you discover that for yourself.

8. H. D., ‘ The Pool ’.

After Hulme’s free verse lyrics came the imagists – a group of modernist poets who placed the poetic image at the centre of their poems, often jettisoning everything else. H. D., born Hilda Doolittle in the US in 1886, was described as the ‘perfect imagist’, and ‘The Pool’ shows why.

In this example of a short free-verse lyric poem, H. D. offers what her fellow imagist F. S. Flint described as an ‘accurate mystery’: clear-cut crystalline imagery whose meaning or significance nevertheless remain shrouded in ambiguity and questions. Here, H. D. even begins and ends her poem with a question. Who, or what, is the addressee of this miniature masterpiece?

9. W. H. Auden, ‘ If I Could Tell You ’.

Lyric poems weren’t all written in free verse once we arrived in the twentieth century. Indeed, many poets of the 1930s, such as the clear leader of the pack, W. H. Auden (1907-73), wrote in more traditional forms, such as the sonnet or, indeed, the villanelle: a form where the first and third lines of the poem are repeated at the ends of the subsequent stanzas.

In this tender lyric poem, Auden explores the limits of the poet’s ability to communicate to the world – or perhaps, to a loved one?

We have analysed this poem here .

10. Carol Ann Duffy, ‘ Syntax ’.

Duffy’s work shows a thorough awareness of poetic form, even though she often plays around with established forms and rhyme schemes to create something new.

First published in 2005, ‘Syntax’ is a contemporary lyric poem about trying to find new and original ways to say ‘I love you’. Duffy’s poem seeks out new ways to express the sincerity of love, explored, fittingly enough, in a new sort of ‘sonnet’ (14 lines and ending in a sort-of couplet, though written in irregular free verse). A love poem for the texting generation?

We introduce more Carol Ann Duffy poems here .

2 thoughts on “10 of the Best Examples of the Lyric Poem”

- Pingback: Monday Post – 16th December, 2019 #Brainfluffbookblog #SundayPost | Brainfluff

- Pingback: 10 Interesting Posts You May Have Missed in December 2019 – Pages Unbound | Book Reviews & Discussions

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Discover more from interesting literature.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

The Lyric Theory Reader

edited by Virginia Jackson and Yopie Prins

Reading lyric poetry over the past century. The Lyric Theory Reader collects major essays on the modern idea of lyric, made available here for the first time in one place. Representing a wide range of perspectives in Anglo-American literary criticism from the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the collection as a whole documents the diversity and energy of ongoing critical conversations about lyric poetry.

Virginia Jackson and Yopie Prins frame these conversations with a general introduction, bibliographies for further reading, and introductions to each of the anthology’s ten sections: genre...

Virginia Jackson and Yopie Prins frame these conversations with a general introduction, bibliographies for further reading, and introductions to each of the anthology’s ten sections: genre theory, historical models of lyric, New Criticism, structuralist and post-structuralist reading, Frankfurt School approaches, phenomenologies of lyric reading, avant-garde anti-lyricism, lyric and sexual difference, and comparative lyric.

Designed for students, teachers, scholars, poets, and readers with a general interest in poetics, this book presents an intellectual history of the theory of lyric reading that has circulated both within and beyond the classroom, wherever poetry is taught, read, discussed, and debated today.

Related Books

edited by Michael McKeon

edited by Michael Groden, Martin Kreiswirth, and Imre Szeman

Inger Sigrun Bredkjær Brodey

Andrew Burstein

edited by David A. Brewer and Crystal B. Lake

The thesis of The Lyric Theory Reader —that the very existence of the genre is more a critical extrapolation than anything solid and real—may seem to be itself a kind of critical conceit, but only because the argument serves the Reader exceptionally well as a cogent frame for taking stock of a diversity of approaches. Accordingly, the Reader would seem especially useful as a primer for up and coming scholars... Overall, the Reader should be considered essential in the formation of a thoughtful scholar of poetry and its criticism.

Through an astute selection of essays and a series of brilliant commentaries on them, Jackson and Prins show that although the way we conceive lyric is a recent invention that embodies a singularly modern and Western set of cultural ideas and values, we uphold lyric as the universal model of what poetry is and should be. Reading The Lyric Theory Reader is an exhilarating experience. In collecting what are arguably the most important modern statements about lyric, it opens up the diverse acuity of commentary on this most enduringly canonical of literary categories, and in that process encourages our most searching reflections on the historical existence of literary forms.

A distinct account emerges of the life-history of the conception of the lyric as a genre—from the moment of its recognition as a genre that is said to have always been central, to the New Critical insistence that lyric is available because everyone can overhear it, to the increasing equation of lyric with poetry that occurs as the collapse of the genre system washes over both the novel and the lyric, leaving narrative and poetry in its wake. The Lyric Theory Reader is a worthy counterpart to Michael McKeon’s Theory of the Novel . It will be essential reading for anyone interested in the lyric, in poetry.

Virginia Jackson and Yopie Prins have done tremendous service to poetics in the nuanced and comprehensive work of constellation and accompanying commentary—providing a model of editorial lucidity, a library in a box, and a ceaselessly generative contradiction which is in the end perhaps itself the strongest argument for the lyric’s eccentric centrality.

Book Details

Acknowledgments General Introduction Part I. How Does Lyric Become a Genre? Section 1. Genre Theory Section 2. Models of Lyric Part I. Twentieth-Century Lyric Readers Section 3. Anglo- American New

Acknowledgments General Introduction Part I. How Does Lyric Become a Genre? Section 1. Genre Theory Section 2. Models of Lyric Part I. Twentieth-Century Lyric Readers Section 3. Anglo- American New Criticism Section 4. Structuralist Reading Section 5. Post- Structuralist Reading Section 6. Frankfurt School and After Section 7. Phenomenologies of Lyric Reading Part III. Lyric Departures Section 8. Avant- garde Anti-lyricism Section 9. Lyric and Sexual Difference Section 10. Comparative Lyric Contributors Source Acknowledgments Index of Authors and Works

Virginia Jackson

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: $20.94 $20.94 FREE delivery: Wednesday, April 10 on orders over $35.00 shipped by Amazon. Ships from: Amazon Sold by: srwilson62

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Buy used: $12.43

Other sellers on amazon.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the authors

Radiant Lyre: Essays on Lyric Poetry Paperback – January 23, 2007

Purchase options and add-ons.

An essential collection of essays by important contemporary poets about the forms and rhetorical strategies of lyric poetry We are delighted when we recognize patterns and continuities, as we are delighted by a new poem's radical adjustment of, critique of, rejection of, or simple application of those patterns and modes. A poem means something because of previous poems. ―from the Introduction Radiant Lyre: Essays on Lyric Poetry is a significant new book on poetry from its earliest, traditional roots to its most recent and fractured forms. The essays gathered here, by an array of brilliant contemporary poets, explore the history of the lyric poem, its rhetorical modes and strategies. How does the lyric operate in an elegy, a love poem, or an ode? How is meaning conveyed by a pastoral poem, the sublime, the narrative? How does the lyric investigate nature, beauty, and time? How are these lyric forms and strategies received? Radiant Lyre gives the contemporary reader a sense of the origin, evolution, and present status of the modes and means of lyric poetry. David Baker and Ann Townsend have assembled an important anthology, vital to any serious reader of poetry. Contributors include Linda Gregerson, Richard Jackson, Eric Pankey, Carl Phillips, and Stanley Plumly.

- Print length 256 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Graywolf Press

- Publication date January 23, 2007

- Dimensions 6.17 x 0.88 x 8.86 inches

- ISBN-10 1555974600

- ISBN-13 978-1555974602

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Customers who bought this item also bought

Editorial Reviews

From publishers weekly, about the author.

David Baker is the author of Midwest Eclogue and Heresy and the Ideal: On Contemporary Poetry . He is the poetry editor of The Kenyon Review.

Product details

- Publisher : Graywolf Press (January 23, 2007)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 256 pages

- ISBN-10 : 1555974600

- ISBN-13 : 978-1555974602

- Item Weight : 15.2 ounces

- Dimensions : 6.17 x 0.88 x 8.86 inches

- #2,495 in Poetry Literary Criticism (Books)

- #8,161 in Essays (Books)

- #10,734 in Literary Criticism & Theory

About the authors

Ann townsend.

Ann Townsend is the author of three collections of poetry: Dear Delinquent (Sarabande Books, 2019), The Coronary Garden (Sarabande Books, 2005), and Dime Store Erotics (Silverfish Review Press, 1998), winner of the Gerald Cable Prize. She also is the editor of a collection of essays, Radiant Lyre: Essays on Lyric Poetry, (with David Baker), published by Graywolf Press in 2007. Her poetry and essays appear in such magazines as The American Poetry Review, Poetry, The Paris Review, The Nation, The Southern Review, and many others. She has read her poems and lectured on poetry and poetics at colleges, universities, writer's workshops, and bookstores around the country.

Professor of English and Creative Writing at Denison University, she teaches courses in creative writing, twentieth century poetry and literary translation. She lives on a small farm in Granville, Ohio where she hybridizes modern daylilies and tends several acres of woods, gardens and orchards.

You can find Ann on Twitter at @anntownsendpoet.

David Baker

David Baker is author of thirteen books of poetry, most recently "Whale Fall" (W. W. Norton, 2022), "Swift: New and Selected Poems" (W. W. Norton, 2019), "Scavenger Loop" (Norton, 2015), "Never-Ending Birds" (Norton, 2009), which won the Theodore Roethke Memorial Poetry Prize in 2011, and "Midwest Eclogue" (Norton, 2005). His six books of prose include "Seek After: Essays on Modern Lyric Poets" (SFA University Press, 2018), "Show Me Your Environment: Essays on Poetry, Poets, and Poems" (Michigan, 2014) and, with Ann Townsend, "Radiant Lyre: Essays on Lyric Poetry" (Graywolf, 2007). Among his awards are prizes and grants from the Guggenheim Foundation, National Endowment for the Arts, Mellon Foundation, and Society of Midland Authors. He holds the Thomas B. Fordham Chair at Denison University, in Granville, Ohio, and is Poetry Editor of "The Kenyon Review."

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top review from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Start Selling with Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

The Writing Seminars

The american sonnet: an anthology of poems and essays.

- Dora Malech (co-editor)

- University of Iowa Press , 2022

- Purchase Online

Poet and scholar team Dora Malech and Laura T. Smith collect and foreground an impressive range of sonnets, including formal and formally subversive sonnets by established and emerging poets, highlighting connections across literary moments and movements. Poets include Phillis Wheatley, Fredrick Goddard Tuckerman, Emma Lazarus, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Gertrude Stein, Fradel Shtok, Claude McKay, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Ruth Muskrat Bronson, Langston Hughes, Muriel Rukeyser, Gwendolyn Brooks, Dunstan Thompson, Rhina P. Espaillat, Lucille Clifton, Marilyn Hacker, Wanda Coleman, Patricia Smith, Jericho Brown, and Diane Seuss. The sonnets are accompanied by critical essays that likewise draw together diverse voices, methodologies, and historical and theoretical perspectives that represent the burgeoning field of American sonnet studies.

- National Poetry Month

- Materials for Teachers

- Literary Seminars

- American Poets Magazine

Main navigation

- Academy of American Poets

User account menu

On Poetry and Community: Jason Magabo Perez

Page submenu block.

- literary seminars

- materials for teachers

- poetry near you

Here in Futures of Joy (On San Diego Community Poetics)

In memory and rememory of Elaine Joy de la Cruz (1978–2003)

Perhaps we were already living these futures. Perhaps we were already living these possibilities. Perhaps, on that rainy and soft-hearted, Manila-like, humid summer afternoon in downtown Chicago, you and I were living a critical moment foretold. I like to believe so. I like to believe that ancestors broke open some sky that summer. I like to believe deeply in the ars poetica of our conversation.

It was 2003, and by that summer we’d already become dear comrades and collaborators. In San Diego, we’d struggled side by side (along with our other dear comrades) for educational justice, for ethnic studies, for a living wage for campus janitors, for dignity and liberation at the onset of a brutal, imperialist War on Terror. We’d performed raw and materialist and urgent poems at both campus and citywide protests, at the Poetry Slam at Urban Grind, Poetic Brew at Claire de Lune’s, Pass the Peas at Galoka, on the Porter’s Pub stage, at Che Café, the UCSD Cross-Cultural Center, and in the middle of Price Center. We’d been inspired by the generous and unapologetic Chicago hip-hop radical realism of I Was Born with Two Tongues, the deeply Bay Area lyrical swagger of 8th Wonder, the anti-imperialist rap chant poetics of the Los Angeles-based Balagtasan Collective, and the bluesy, folksy spiritual medicine of the Michigan-based Long Hairz Collective. And of course, we’d learned about the critical poetics of geography and space-making genius right here in San Diego from the local and legendary Taco Shop Poets. We built solidarity with fellow poetry crews across the city like Elevated, Able Minded Poets, and Goat Song Conspiracy, shared stages across the state with crews like Zero 3, iLL-Literacy, and Proletariat Bronze. We, so young and inexperienced but so committed, had even been invited a few times to run spoken word workshops for local high school students. Those early years had been so intense, so formative, so future-making. How expansive the geographies of our literacies and literature!

Now here we were in the summer of 2003, in downtown Chicago for the APIA Spoken Word Summit. I had braved the first day of the summit alone and was anxiously awaiting your arrival. When you arrived, everyone was all about you. Of course they were—you were an undeniably gifted, gorgeous, and relentless force of lyric and litany, a living example of the poetics of liberation. Who wouldn’t have wanted to say that they knew you? Spoke to you? Witnessed you reading a poem? Dedicated and read a poem to you? That rainy and humid summer afternoon, you and I were eating sandwiches outside Subway. I was debriefing about the first day of the summit. I was inspired and impressed that so many of these poets had come up through or were now teaching and mentoring with literary arts nonprofits like Youth Speaks in their respective regions. “We need something like Youth Speaks in San Diego,” I said. And with all of your calming and confident wisdom you said, “Let’s just build one.” I didn’t then have the capacity to receive that invitation and push. I didn’t realize that this was the conversation that I would return to year after year.

Two months later, you died in a car accident. To this day, we are still here, gathering and making sense and space for Joy. To this day, I speak to you in prayer. I have your signature tattooed on my forearm. I carry you with me—or rather, it’s you who carries me, isn’t it? I sometimes wonder what an alternative timeline might have presented, what a different relationship to poetry and poetics I might have had, what our collaborations might have been. To this day, I ask: What if we had built that poetry and liberation center in San Diego? What if we had grounded that space in experimentation, collaboration, and genuine solidarity? I wonder what worlds open up when we model a radical poetics of relation, when we reckon with our historical and literary entanglements and intimacies, when we develop a shared grammar of past, present, and future. I wonder what worlds open up, what clarity comes, when our poetics remain in the Undercommons—as fugitive, anti-disciplinary, insurgent knowledge from below. Yes, I stay principled, stay anti-imperialist, stay anti-capitalist, stay rough draft, stay ethnic studies, stay close to the ground, stay rooted, stay poetry for the people. And so many we’d met along the way have continued this vital work of community poetics. I often route myself through that seemingly quotidian summer conversation and I wonder if—even that early on—we already knew how to do this work. We were a future organizing for a future of futures. That small conversation opened up so many possibilities, opened up so many spaces to return to.

Here in San Diego, here on occupied Kumeyaay land, here on the coast, here against the border, it feels like the poets and organizers are moving within and returning to these futures, possibilities, and spaces for return. It’s humbling and healing to witness this work, to reflect on it, and to have that same conversation with you over and over again. I know for sure, my dear kasama , that if you and I were to check in right now, as I hold this poet laureate post, as I continue to organize through poetry, you would remind me of how we came up, how poetry and community and solidarity and relationality and liberation have always been the same project; how we commit to this work in a way that shows it’s always people before poetry, always food before poetry, always the U.S. out of the Philippines before poetry, always abolish prisons and police before poetry, always LAND BACK before poetry, always PERMANENT CEASEFIRE NOW before poetry, always END THE OCCUPATION before poetry, always FREE PALESTINE before poetry.

Jason Magabo Perez , poet laureate of San Diego, California, is the author of I ask about what falls away, forthcoming in 2024; This is for the mostless (WordTech Editions, 2017); and Phenomenology of Superhero (Red Bird Chapbooks, 2016). In 2023, he was named an Academy of American Poets Laureate Fellow . Perez will launch a youth empowerment poetry project that includes youth mentorship and workshops on poetry, performance-making, filmmaking, and video art. The project will feature collaborations with local high school ethnic studies and English teachers and the development of open-access poetry curricula, grassroots publishing initiatives, and a culminating youth poetry summit in San Diego.

Newsletter Sign Up

- Academy of American Poets Newsletter

- Academy of American Poets Educator Newsletter

- Teach This Poem

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Author Interviews

A conversation with the author of 'there's always this year'.

NPR's Scott Detrow speaks to Hanif Abdurraqib about the new book There's Always This Year . It's a mix of memoir, essays, and poems, looking at the role basketball played in Abdurraqib's life.

SCOTT DETROW, HOST:

The new book "There's Always This Year" opens with an invitation. Here's a quote - "if you please imagine with me, you are putting your hand into my open palm, and I am resting one free hand atop yours. And I am saying to you that I would like to commiserate here and now about our enemies. We know our enemies by how foolishly they trample upon what we know as affection, how quickly they find another language for what they cannot translate as love." And what follows from that is a lyrical book about basketball but also about geography, luck, fate and many other things, too. It's also about how the career arc of basketball great LeBron James is woven through the life of the book's author, Hanif Abdurraqib, who joins us now. Welcome back to the show.

HANIF ABDURRAQIB: Thank you for having me again, Scott. It's really wonderful to be here.

DETROW: You know, I love this book so much, but I'm not entirely sure how to describe it. It's part memoir, part meditation, part poetry collection, part essay collection. How do you think about this book?

ABDURRAQIB: You know, it's funny. I've been running into that too early on in the process and now - still, when I'm asked to kind of give an elevator pitch. And I think really, if I'm being honest, that feels like an achievement to me because so much of...

DETROW: Yeah.

ABDURRAQIB: ...My intent with the book was working against a singular aboutness (ph) or positioning the book as something that could be operating against neat description because I think I was trying to tie together multiple ideas, sure, through the single - singular and single lens of basketball. But I kind of wanted to make basketball almost a - just a canvas atop which I was laying a lot of other concerns, be it mortality or place or fatherhood and sonhood (ph) in my case. I think mostly it's a book about mortality. It's a book about the passage of time and attempting to be honest with myself about the realities of time's passing.

DETROW: Yeah, it seems to me like it could also be a book about geography, about being shaped by the place you grew up in and that moment where you choose to stay or leave, or maybe leave and come back. And I was hoping you could read a passage that that deals directly with that for us.

ABDURRAQIB: Of course. Yeah. This is from the third quarter or the third act of the of the book.

(Reading) It bears mentioning that I come from a place people leave. Yes, when LeBron left, the reactions made enough sense to me, I suppose. But there was a part of me that felt entirely unsurprised. People leave this place. There are Midwestern states that are far less discernible on a blank map, sure. Even with an understanding of direction, I am known to mess up the order of the Dakotas. I've been known to point at a great many square-like landscapes while weakly mumbling Nebraska. And so I get it. We don't have it too bad. People at least claim to know that Ohio is shaped like a heart - a jagged heart, a heart with sharp edges, a heart as a weapon. That's why so many people make their way elsewhere.

DETROW: What does Ohio, and specifically, what does Columbus mean to you and who you are?

ABDURRAQIB: I think at this stage in my life, it's the one constant that keeps me tethered to a version of myself that is most recognizable. You know, you don't choose place. Place is something that happens to you. Place is maybe the second choice that is made for you after the choice of who your parents are. But if you have the means and ability, there are those of us who at some point in our lives get to choose a place back. And I think choosing that place back doesn't happen once. I mean, it happens several times. It's like any other relationship. You are choosing to love a place or a person as they are, and then checking in with if you are capable of continuing to love that place or person as they evolve, sometimes as they evolve without you or sometimes as you evolve without them. And so it's a real - a math problem that is always unfolding, someone asking the question of - what have I left behind in my growth, or what has left me behind in a growth that I don't recognize?

So, you know, Columbus doesn't look the way - just from an architectural standpoint - does not look the way it looked when I was young. It doesn't even look the way it looked when I moved back in 2017. And I have to kind of keep asking myself what I can live with. Now that, for me, often means that I turn more inward to the people. And I began to think of the people I love as their own architecture, a much more reliable and much more sturdy architecture than the architecture that is constantly under the siege of gentrification. And that has been grounding for me. It's been grounding for me to say, OK, I can't trust that this building will stay. I can't trust that this basketball court will stay. I can't trust that this mural or any of it will stay. But what I do know is that for now, in a corner of the city or in many corners of the city, there are people who know me in a very specific way, and we have a language that is only ours. And through that language, we render each other as full cities unto ourselves.

DETROW: Yeah. Can you tell me how you thought about basketball more broadly, and LeBron James specifically, weaving in and out of these big questions you're asking? - because in the first - I guess the second and third quarter, really, of the book - and I should say, you organize the book like a basketball game in quarters. You know, you're being really - you're writing these evocative, sad scenes of how, like you said, your life was not unfolding the way you wanted it in a variety of ways. And it's almost like LeBron James is kind of floating through as a specter on the TV screen in the background, keeping you company in a moment where it seems to me like you really needed company. Like, how did you think about your relationship with basketball and the broader moments and the broader thoughts in those moments?

ABDURRAQIB: Oh, man, that's not only such a good question, but that's actually - that's such a good image of LeBron James on the TV in the background because it was that. In a way, it was that in a very plainly material, realistic, literal sense because when I was, say, unhoused - right? - I...

ABDURRAQIB: ...Would kind of - you know, sometimes at night you kind of just wander. You find a place, and you walk through downtown. And I remember very clearly walking through downtown Columbus and just hearing the Cavs games blaring out of open doors to bars or restaurants and things like that, and not having - you know, I couldn't go in there because I had no money to buy anything, and I would eventually get thrown out of those places.

So, you know, I think playing and watching basketball - you know, even though this book is not, like, a heavy, in-depth basketball biography or a basketball memoir, I did spend a lot of time watching old - gosh, so much of the research for this book was me watching clips from the early - mid-2000s of...

ABDURRAQIB: ...LeBron James playing basketball because my headspace while living through that was entirely different. It's like you said, like LeBron was on a screen in the background of a life that was unsatisfying to me. So they were almost, like, being watched through static. And now when I watch them, the static clears, and they're a little bit more pleasureful (ph). And that was really joyful.

DETROW: LeBron James, of course, left the Cavs for a while. He took his talents to South Beach, went to the Miami Heat. You write - and I was a little surprised - that you have a really special place in your heart for, as you call them, the LeBronless (ph) years and the way that you...

ABDURRAQIB: Oh, yeah.

DETROW: ...Interacted with the team. What do you think that says? And why do you think you felt that way and feel that way about the LeBronless Cavs?

ABDURRAQIB: I - you know, I'm trying to think of a softer word than awful. But you know what? They were awful.

DETROW: (Laughter).

ABDURRAQIB: I mean they were (laughter) - but that did not stop them from playing this kind of strange level of hard, at times, because I think it hit a point, particularly in the late season, where it was clear they were giving in and tanking. But some of those guys were, like, old professionals. There's, like, an older Baron Davis on that team. You know, some of these guys, like, did not want to be embarrassed. And...

ABDURRAQIB: ...That, to me, was miraculous to watch where - because they're still professionals. They're still NBA players. And to know that these guys were playing on a team that just could not win games - they just didn't have the talent - but they individually did not want to - at least did not want to give up the appearance that they weren't fighting, there's something beautiful and romantic about that to me.

DETROW: It makes a lot of sense why you end the book around 2016 when the Cavs triumph and bring the championship to Cleveland. But when it comes to the passage of time - and I'll say I'm the exact same age as you, and we're both about the same age as LeBron. When it comes to the passage of time, how do you present-day feel about LeBron James watching the graying LeBron James who's paying so much attention to his lower back? - because I don't have anywhere near the intense relationship with him that you do. But, I mean, I remember reading that Sports Illustrated when it came out. I remember watching him in high school on ESPN, and I feel like going on this - my entire adult life journey with him. And I feel like weirdly protective of LeBron James now, right? Like, you be careful with him.

ABDURRAQIB: Yeah.

DETROW: And I'm wondering how you think about him today and what that leads your brain to, given this long, long, long relationship you have with him.

ABDURRAQIB: I find myself mostly anxious now about LeBron James, even though he is still - I think he's still playing at a high level. I mean, I - you know, I think that's not a controversial statement. But I - while he is still playing at a high level, I do - I'm like everyone else. So I'm kind of aware that it does seem like parts of him - or at least he's paying a bit more attention to the aches that just come with aging, right?

ABDURRAQIB: I have great empathy and sympathy for an athlete who's dedicated their life to a sport, who is maybe even aware that their skills are not what they once were, but still are playing because that's just what they've done. And they are...

ABDURRAQIB: ...In some cases, maybe still in pursuit of one more ring or one more legacy-building exploit that they can attach to their career before moving on to whatever is next. And so I don't know. And I don't think LeBron is at risk of a sharp and brutal decline, but I do worry a bit about him playing past his prime, only because I've never seen him be anything but miraculous on the court. And to witness that, I think, would be devastating in some ways.

And selfishly, I think it would signal some things to me personally about the limits of my own miracle making, not as a basketball player, of course, but as - you know, because a big conceit of the book is LeBron and I are similar in age, and we have - you know, around the same age and all this. And I think a deep flaw is that I've perhaps attached a part of his kind of miraculous playing beyond what people thought to my own idea about what miracle is as you age.

And so, you know, to be witness to a decline, a sharp decline would be fascinating and strange and a bit disorienting. But I hope it doesn't get there. You know, I hope - I would like to see him get one more ring. I don't know when it's going to come or how it's going to come, but I would like to see him get one more. I really would. My dream, selfishly, is that it happens again in Cleveland. He'll come back here and team up with, you know, some good young players and get one more ring for Cleveland because I think Cavs fans, you know, deserve that to the degree that anyone deserves anything in sports. That would be a great storybook ending.

DETROW: The last thing I want to ask about are these vignettes and poems that dot the book in praise of legendary Ohio aviators. Can you tell me what you were trying to do there? And then I'd love to end with you reading a few of them for me.