- Original Books

- Solved Assignments

- Guess Paper

Sunday, October 20, 2019

Aiou intermediate (fa/i.com) solved assignments - autumn 2023.

Welcome to our website. If you are a student of Allama Iqbal Open University (AIOU) and pursuing Intermediate program, then you have come to the right place. We offer solved assignments for Intermediate (FA/ICOM) 2 years program that you can download easily from our website. Apart from this, we also have helping books available for purchase that can assist you in preparing for your exams. To stay updated with our latest resources, we recommend that you subscribe to our AIOU Studio 9 YouTube channel, where we regularly upload informative videos related to AIOU and its programs.

Intermediate (FA/ICOM) 2 years program

Solved Assignments of Spring / Autumn 2023.

2,174 comments:

books me ha code 364 assignment answer

Sir intermediate course code 363 ki assignment details

Sir 363 or 317 ke assignments be uploud kr dain

Sir 305 and 306 plz upload kar rain

Daniyal Bhai MashAllah 💖 🌹

Allah Pak mazeed AP ko kamyabi ata farmay

Thnks my dear 312 ki assignment no 4....?

Sir 364 ,376 ki assignments bh bta dein plzzz

363 assignment fa autumn ki kab ay ge

Fa ki urdu 363 upload kar da

Asslam o Alaikum Daniyal Iqbal beautiful ❤️

Sir 363 ki be upload kar day

Urdu 363 Ki asaiment b upload kr dy plzzz

376 FA autumn 2019 bi kr dain Daniyal Bhai

Sir urdu code 364 assignment number 1 kb tk a jay gi

Sir muslim history of subcontinent ki assignmnt kab aye gi?

305 and 357

317 puri nhi hai?????

357 KI CHYE SIR JALDI UPLOAD KAR DEN

Sir kindly code363 ki assignments b upload krdain..please..

dear after how much time code 311 assignments are upload.?

Sr 363 bhj den

Kindly 308 ki baki assignment b unload kr dein

Sir kindly upload fa code 376 and 360 solved assignment plzzz

363 ki assignment upload kar daien.. Please

Sir assignment submit karwany ki last date kiya hai??? And assignment 1 or assignment 2 akathy h karwani jama ??

Plz sir 311 ki assigment upload kara dy plz boht difficult ha.... aur agr es main koyi help chaheye ho mtlb examplz waghaira k bary main tou tuitor sy contact karaingy....

363 sir upload kro na

349 ki assignment b upload or dy sir plz Jaldi

Sir please 360 upload karo.

asslam o alikum sir 357 and 305 ki assignment chayie

364part1 open nhi ho rha.kb tk open hoga?

363 ki baije dain

363 or 311 ki b bhj dain plzz

sir 363 ki upload kr den pleaseeeeeee

364 ki 1st Assignment kb tk aye g.

Assalam o alaikum...! Daniyal bhai FA assignment code 322 nhe hein????😐😐😐

General science Ke baqi upload kar dein

sir mere abhi tk books nhi aye tu kya mai ye lekh sakhta ho ? Mai first time Aiou mai admission kya hai tu guide kro plzzzz

Sir ,Arabic ki bna den Plz plz plz.....

Bhai f a ki urdu autum 2019 ka solved paper upload kar dain

311 ki b krdain send plz

363 ni shoo ho rha

364ke1st wali assignment open kase ho ge ni ho rahi wo open

357 ki sir g plzzz

363 assignment plz

Thanks a lot sir G ALLAH pak salamat rakhy

349 ki sir g assignment

Thnks dani bhai

Sir plz bata dain assignmnts ink pen sy likh sakty hain kya ???

Acha sir mujay yeh bataa day k F.A code 305 ki assignment no 1 and 2 ka upload ho gi

Aslamo Alaikum sir 303 ki 1,2,3,4 assignment upload kar dijiye jaldi

Sir 311 plzzz

376 ki assignment no. 3 and 4. Please

sir 360 ki 1st assignment pdf urdu me kaisy aya ge

sir 360 urdu me chahiye

Sir i want 360 an urdu

Sir I want 303 2nd assignment

Asslam-o-Alaikum Sir Sir I want 317, 363 2nd assignment

Plz sir publish these assignments.

303 ki assignments jaldi upload kijiye plz

dear sir 360 urdu me chahiye meri book b urdu me ayi hain plz

376 ki 3rd or 4rd assignment kab tak aahain gi or 312 ki last 4 assignment kab donwload krain gy dani bhai.

This site is very helpful for every one (Bot bot niwazish)

376 and 312 plzz all assignment send Daniiiii Bhai

Sir 305 code ki assignment send ker dain

Baki exercise my PDF likha hai 2 wali my sapace hai WO open nhi ho rhi plzzzz send kr dy....

sir 360 or 347 ki kb aye gi assinment

303 ki 2nd assignment nhi hai plz upload kr den

Aoa fa ki 317 code ki 2 assignment is pr nh a rhi hai?

This comment has been removed by the author.

Asslam-o-Alaikum Sir Plz code 317 (FA) Gen group ki 2nd assignment publish kar dain.

Plz sir AIOU code 317 ki 2nd assignment dy dain

Plz dear 03034794378 py assingment send kr do 376

1421 k assignment please upload krde

311 code key sir ni hain

Aoa sir plzz 1307 assignement. Uplode karda plzzzzzzz

303 ki 2nd assignment upload kr den plz

376 ki first assignment plz sir provide ker dain

Abhi tk fa code 317 ka is pr nh aya

Sir 321 ki No 4 upload kr dein plllzzz Aur 376 ki 3 aur 4 Shkriya

Sir 303 ki second assignment bhe upload karen plz

376 autumn 2019 ki 3 or 4 assignment bi donwload kr dain

1309 mathematics solved assigment send karen

salam.plz urdu ki assignment code 364 send kr Dy 1&2 plz

sir g 311 or 346 ki k send kar day pla juld

305 Rural Development assignment please

Assalam o alaikum sir kindly upload assignment number 2 or 317 please sir

317 ki 2nd assignment kb upload hngi

376 ki 3rd and 4 assignment kab upload kro gy Daniyal bhai

321 ki 4 Num upload kar do.

Code 311 upload karay plzz

Bhi 347 key kb aye ghe assignment please

Code 311 ki assignment bhe upload kr den

1308 ke 2nd assignment aur assignment 1 aur 2 ke Question papers chaheay

Please upload PakStudy(317) part 2 solved assignment.

thanks sir it is very useful website please upload the 347 solve assignment

Sir 321 ki 4th

plz 389 code ki solved assignment bta dain kab ayegi

plz reply mee fast.......

305 assignments needed plz

Sir plzz 317 ka part 2 bi upload kr dy

Mera tuotr ni kill rha kesy pta chly GA goggle pr ni shoo hobrh

sir please upload 361(Persian) assignment.

317 ki 2nd assignment open ni hurai q

Bundle of thanks sda khus abad rhin ap ki yeh naki rahighn na jy its a good efforts for those students who not buy solved assignments .salmt rahiy

Sir excuse me! Ap ny code:316 ki assignment no:2 mai code:317 ki assignment no:2 upload ki hai.so please kindly check out there,and upload again that which is correct one as much as it can possibly hurry.thankyou..

Dear sir Can u share me English F.A autunm 2019 assignment

Kindly share me IT 360 solved assignment in Urdu language

A. O. A sir. Plz upload 1307 assignment fast

sir 311or 346 ki 3or 4 mashak send karay

Kindly ipload 322 i com asgnmnt

I appreciate your work daniyal sir.That's Awesome.

Dear Sir, Ap ne code 316 ki Islamiyat ki 2nd assignment men 417 code assignment upload ki hui hy. kindly usy update kren.

THANKS BUDDY

0305 ki upload kr dain

0305 or0303 ki 2sri bi upload kr dain plz

Bhi please send me 347 301 assignment aiou

Please assignment send me 322

361 plzzzzz🙏

Dear sir, 305 (rural development) ki solved assignment to upload kar dy plzzzzz

Sir fa ki 321 ki 4th assignment chaiye

389 F.A QURAN HAKEEM KI ASSIGNMENT PLZ UPLOAD KAR DY PLZ

Sir f.a banking ki assignment b upload kar dein please

301 ki 2nd kb ayge

Please 301 ki 2nd bhi upload kar den

Sir 322 Aur 305 Ki Assignments Upload Kar Dayn Thanks

السلام علیکم بہت شکریہ آپ کا آپ ہماری اتنی مددکرتے ہے

347 ki kb hngi upload

#1307 FA ki assignment upload krdein.. paisay ly lein per krdein..

309 ki kb aey g.

389 bhi upload karen plz

Sir 346 code icom ki assignmnt 3'4 kb aye gi?????

Sir code 346 ki assgnmnt 3'4 kb aye gi????

sir please 395 2nd assignment please

sir 301 ki assignment no 2 kab ay gi....?

sir dehi taraqee intermediat unit 1-9 code 305??

Hello! Sir kindly 1307 ki assignments aur 1308 ki 2nd assignment upload karday.

301 key 2nd assignment kb aye ge

Bhai 360 urdu may upload karo

Bhai 346 ki 3,4 assignment upload kryn plz. Thanks

Bhai 346 ki 3rd or 4 assignment upload kryn plz.Thanks

222 & 215 ki assignment upload krein plz

Sir Kindly uploaded fA Rural Development 305

Sir kindly uploaded 305

0395 ki 2 mashq upload kab ho gi

395 ki assignment 2ri mashq b upload kr den

F.A 1309 mathematics 3 assignment 1 and 2?

Sir plzzzzz 305 send kardain

Sir 395 part 2 ki assignment upload kr den plzzzz

395 ki scnd exercise snd plz

Sir plz 1307 ki assignments upload kar den time bht kam hai plzzzź

1309 mathematics 3 solved assignments 1 and 2

305 ki nai h assignments

364 ka next 2 part uplod kar dain

Sir 395 2nd assignment ka kafi denon se intezar ha

ASSALAMUALAIKUM Sir g 346 ka assignment 3 or 4 send krain sir

395 part to sir please update

A.o.a sir fa 301 ki 2nd and 305 ki 1st and 2nd assignment upload kr dn kindly

Sir persian ki 0361

Sie persian ki 0361 f.a

301 ki kb 2nd assignment aye gye

sir 395 second assignment upload kar dain

Aslam o alikum yahan code 389 ki assignment q Nahi Hy? Plss agr Kisi k pass Hy to BTa dain M rabta kr lon gi

Asalm o alikum sir 389 ki assignment bi BNA dain plzzz

Sir 322 ki assignment no 2 upload kr dain

305 ki assignment missing ha usko bi upload kar daina.

sir 305 code ki solved assignment

sir 305 ki assignment

Bhai bhot acha kaam karrhay ho i like it sirf aik aur assignment upload kar do 322 Icom

Please 395 ki 2nd bhi upload kar den

slam bhai 346 ki 3,4 upload kryn plz

good website

Sir 361 code wali Solved Assignments nhi hain... wo bhi upload kar dain. Thanks

0402.0438.1424 ye assignment chahye mujhe

4657 ki assiment plz

A.O.A sir kindly 395 KI 2ND ASSIGNMENT UPLOAD KR DY

I m very thankfull to u sir ap nay 389 ke assing uploud ke plz sir 2 and 3 be uploud kar dain plz sir ap ka bout shukriaya

Plz 389 2nd and 3rd

M.a urdu 5601 5602 5603 5604 first semster plz sir uploud kar dain

A.o.a sir computer technology applications 360 ki assignment urdu me send Kar dyn please

395 ki 2nd wali assignments chahiye plz

Daniyal bhai 301 ki assignment no# 2 not available at your supporter blog?

322 bhi kar dein please

AoA sir kindly code 389 ki assignment upload kr dy plz

Sir plzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzz code 247 Ki assignment no 2 upload kar dain please matric ki plzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzz

F.A 360(1&2) IN URDU ASSIGNMENT

Sir 301-2nd assignment upload kr dyplz

A.o.a sr kindly 322 ki 2nd assigment bhi upload kr dein plz

sir F.A code 314 autumn 2019 please

358 or-357 ki assignment s nhi han sir jee

- Join Pak Army

- Join Pak Navy

- Punjab Govt

- Advertise with Us

- Pakistan Passport Renewal

- Nadra Pak Identity

- AIOU Swift Center List

- K-Electric Bill

- Join Whatsapp Group

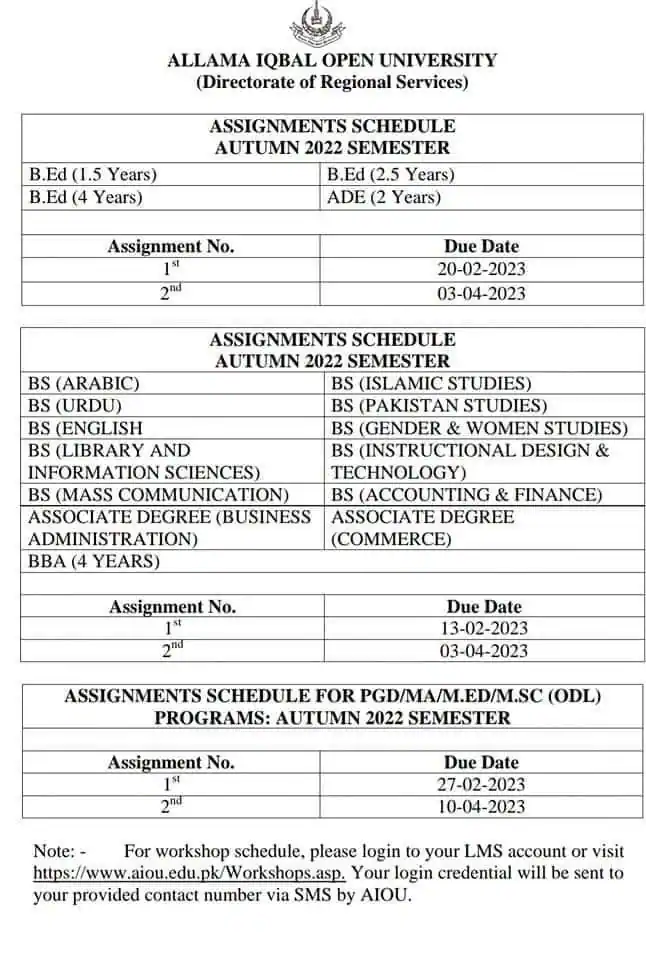

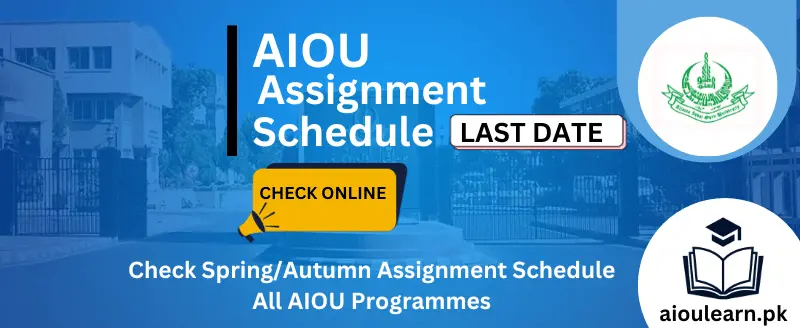

AIOU Assignment Schedule for Autumn 2022 Semester – Allama Iqbal Open University

Allama Iqbal Open University AIOU has issued Assignment Schedule for the Autumn 2022 Semester. This schedule is announced for all programs including Matric, FA, BA, Associate Degree Programs, B.Ed, BS, ADE, ADC, BBA & Post Graduate Programmes.

AIOU Assignment Schedule for Autumn 2022

AIOU Assignment Schedule for B.ED / ADE Programs

AIOU Assignment Schedule for BS Programs / ADC / ADB

AIOU Assignment Schedule for PGD / MA / MSC / M.ED Programs

AIOU Assignment Schedule for BA / Associate Degree Programme

AIOU Assignment Schedule for Matric & FA Programs

AIOu Assignments are assigned through Online LMS Portal for all students. Tutors Name & all other details are available on Students LMS Portals. For more information visit https://aiou.edu.pk/.

AIOU Assignment Schedule Autumn 2022 in PDF

- Matric Programme

- F.A Programme

- BA / Associate Degree Programme

- B.Ed, BS, ADE, ADC, BBA & Post Graduate Programmes

Eid ul Fitr Holidays 2024 Official Notification

Sindh Bank Jobs 2024 – Latest Bank Jobs in Pakistan

CM Punjab Maryam Launches Nawaz Sharif Kissan Card Program

Punjab Govt Announces Local Holiday on 1st April 2024

Employees Corner

CM Punjab Announces Bonus For Employees

NTS Competition Commission of Pakistan Federal Govt Jobs 2024

Bank of Khyber BOK Jobs 2024 Online Apply

CM Punjab Announces Distribution of 50000 Solar Systems Under Roshan Gharana Program

Punjab Education Department News

Punjab Education Department Announces Eid Gift for Pensioners

Private Jobs

Pakistan Oilfields Limited POL Jobs 2024 Apply Online

Discover more from parho pakistan - latest jobs in pakistan.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

- Allama Iqbal Open University (AIOU)

- University of the Punjab

- Scholarships in USA

- Scholarships in Canada

- Scholarships in Belgium

- Scholarships in Germany

- Scholarships in Russia

- Scholarships in Taiwan

- Scholarships without English Proficiency

- Online Courses

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Services

Download AIOU Solved Assignments FA, Icom 2021 • PDFs

AIOU Solved Assignments FA, Icom (Intermediate) 2021 for Free.

Allama Iqbal Open University has a system of Assignments. One must have to send Assignments the Hand-Written assignments to the AIOU Tutor assigned to him/her.

All AIOU Solved Assignments are now updated for Intermediate (FA & ICom) for semester Spring and Autumn in PDF.

- AIOU Solved Assignments of BA, BCom 2021

- AIOU Solved Assignments of BS ODL 2021

- AIOU Solved Assignments of BEd 2021

- AIOU Solved Assignments of Associate Degree Program ADP 2021

- AIOU Solved Assignments of MA, MSc, MEd

Read Also: Check AIOU Tutor Address Online by Roll Number

Allama Iqbal Open University now providing the facility of PDF books in Soft Form for its students. If one has not received its books then he/she can download the AIOU books in PDF .

As we above mentioned that it is necessary to submit assignments because of AIOU count Assignments Marks in Final Result . Submission of Assignments is necessary and students do not have proper guides to solve the questions. That’s why they look for the pre-solved assignments of AIOU . Or, they contact in contact to get pre-hand-written assignments.

Let’s dive in the AIOU Solved Assignments FA, Icom (Intermediate) PDF.

Follow us on our Facebook Page or Join our Facebook group for AIOU updates

Follow us on Twitter

Download Free AIOU Solved Assignments FA, Icom (Intermediate) PDF

Deadline to submit fa, icom assignments.

And, here are the complete details about the deadline of the submission of these assignments.

AIOU Solved Assignments of 3 credit hours subjects

These all books are present in PDF, you can easily avail these in your any device which can open the PDF file.

Read Also: Download FREE AIOU Solved Assignments in PDF

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the last date of aiou fa, icom (intermediate) assignments submission.

Allama Iqbal Open University has extended the date of Assignments. You can submit all of your Allama Iqbal Open University assignments on or before February 20, 2021.

How can I check my AIOU FA, Icom (Intermediate) tutor online?

Well, it is pretty much easy to check AIOU tutor online. You just need your Roll Number to check your assigned tutor. Open this link and here enter your Roll Number to check your Tutor Information online.

Ask your Question

You can easily ask your questions in the comments below. Our team will try their best to promptly help you and will answer your questions as soon as possible

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

Aiou previous result of all years | 2022 to 2021 history of result, aiou extends the last date of admissions (spring 2022), aiou admission 2022 apply online: semester spring & autumn, [2022] download aiou books pdf (all programs), download aiou roll no slips 2022 • all programs, 103 comments.

Madam I can’t find out the 312 and 364solved assignment of FA in 2021 please upload this assignment

sir plzz Cours F.A code 303 ki assignemnt upload kr dy

I.com autumn 2021 ki assignment kasy download ki ja sakti ha please tell me

How can I check online tutor information

A.o.a, 389 ki b assignment upload kr dy plz plzplz plz spring 2021 F.A

Sir Autom 2021 FA ke 1 assignment solve kB upload ho ge or is leya JMA krvna ke last date kya ha

LEAVE A REPLY Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Home » AIOU Latest News 2024 » AIOU Assignments Schedule 2024 Matric, FA, BA, MA, MPhil

AIOU Assignments Schedule 2024 Matric, FA, BA, MA, MPhil

If you are searching the most authentic and updated information about AIOU assignments schedule 2024 for Matric, FA, BA, B.Ed, BS, MA/MSc, MEd, M.Phil and PhD. You can check here the latest schedule of assignments submission for Spring and Autumn semesters. The AIOU is the Pakistan largest organization that provides the home based education in which thousands millions of students (Female and Male) are getting their education from home.

The assignments are also included in every educational program but the number of assignments depend on the degree. It is a golden opportunity for every student to get high marks in assignments just following the guidelines of solving assignments according to the question papers.

You must keep in mind the last date for the completion of assignment and receive at your AIOU Tutor address before the deadline. I will advice you to keep visiting our portal to get additional update regarding revision or extension of last date or assignment date.

AIOU Assignments 2024 Schedule (Updated)

As we already knows that the Allama Iqbal Open University announces two time admissions (Autumn & Spring) in every year. There are different schedule for every semester.

Latest AIOU Assignment News on 6th January 2024 :

- AIOU Announced Assignment Schedule 2023-24 Last Date : Allama Iqbal Open University (AIOU) has recently announced the new schedule of AIOU Assignments submission for Matric, FA, Darse Nizami and ICOM students throughout Pakistan. You can submit your all assignments as per schedule date and after the due date no assignment will be submitted or entertained. [ New ]

- AIOU BA Assignments Result: The AIOU has officially announced the result of BA degree program. Now you can check online your AIOU BA assignments result including all papers marks.

- AIOU BA Assignment Schedule 2024 : The Allama Iqbal Open University has announced the latest schedule of AIOU BA assignment submission schedule 2024 according to the AIOU Autumn Semester 2023. Please follow the below schedule for submission of BA assignments;

AIOU B.A Assignments Submission Schedule : Autumn 2024 Semester

- AIOU Extends Matric, FA Assignments 2024 Submission Date : It is notified for all the concerned that keeping in view the prevailing situation across the country, the Director General Regional Services has graciously extended the deadline for submission of assignments or Matric and FA programs for Semester Spring-2024. The revised date is as given below:

All Regional Heads are requested to intimate the tutors accordingly. The information must be circulated among the students and the same may also be displayed on notice boards Of the office and study/ workshop centers etc.

The Allama Iqbal Open University has officially announced the assignment schedule of Matric, FA, I.Com, B.Ed, ADE, BS, BBA, Associate Degree, PGD, MA, M.Ed and MSc;

Assignment Schedule For BS/Associate Degree/BBA – Program : Autumn 2024 Semester

Assignment schedule for b.ed/ade – program : autumn 2024 semester, aiou matric, fa/ i.com assignments schedule – program : autumn 2024 semester.

- AIOU Autumn 2024 Assignments Schedule : The underlying steps are followed for submission of assignment schedule;

http://result.aiou.edu.pk/AssignmentMarks.asp

The Directorate of Regional Services, AIOU has issued the new assignment schedule given below;

Also Check :

AIOU Admission 2024 Matric, Intermediate, BS, MSc, MPhil, MS, PhD Autumn & Spring Semester

AIOU Latest News About Exams 2024

AIOU Result 2024 Matric, FA, BA, MA Autumn & Spring Semester

Ehsaas Kafalat Program 2024 Registration Centers

AAGHI LMS Portal AIOU 2024

How To Join Online Workshops with LMS & Microsoft Teams Platform

- AAGHI LMS will remain in use as previous practice it will allow the user to integrate automatically with Microsoft Teams.

- Password shall be sent in SMS by AIOU to all the students at their Registered cell numbers.

- Students are required to download Microsoft Teams application either in their computers or in their cell phone. https://t.co/zP4QbP6xOy

- Installed the application and enter your username and ID received in SMS and login to the installed MS Teams application

- Open link https://t.co/CNhiWGn9xK in browser and enter the same username and ID received in SMS from AIOU.

- To activate or integrate MS Teams through AAGHI LMS; once logged in to AAGHI LMS on the right upper corner and in search option write “Microsoft Teams testing* and enter. Click on the button “Microsoft Teams testing” appeared in next window. It will enable to launch MS Teams. Now in chat box write word “Hi” and the enter. This step will enable to activated your account.

- Remember both application AAGHI LMS & Microsoft Teams shall be activated and launched parallel to connect in online workshops.

B.Ed & ADE Assignment Schedule Autumn 2024 Semester

BS Assignment Schedule Autumn 2024 Semester

Assignment schedule autumn 2024 pgd/ma/m.ed/msc (odl) programs.

Note : For workshop schedule, please login to your LMS account or visit https://www.aiou.edu.pk/workshops.asp. Your login credential will be sent to your provided contact number via SMS by AIOU.

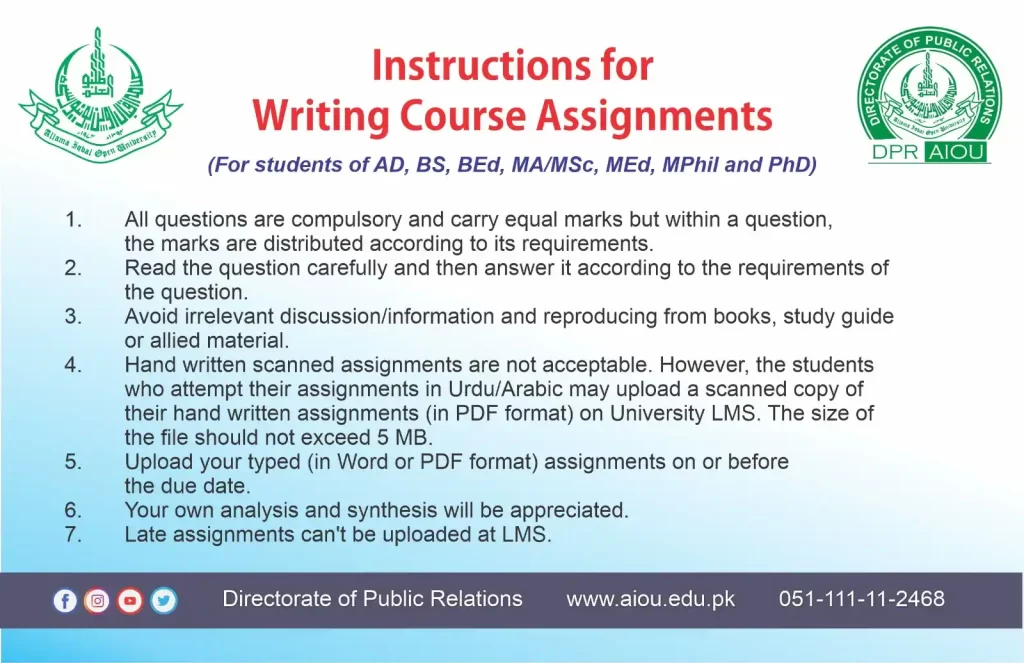

Instructions For Writing of Assignments

Please read the following instructions for writing your assignments.

(AD, BS, BEd, MA/MSc, Med,ATTC) (ODL Mode)

- All questions are compulsory and carry equal marks but within a question, the marks are distributed according to its requirements.

- Read the question carefully and then answer it according to the requirements of the question.

- Avoid irrelevant discussion/information and reproducing from books, study guide or allied material.

- Hand written scanned assignments are not acceptable. However, the students who attempt their assignments in Urdu/Arabic may upload a scanned copy of their hand written assignments (in PDF format) on University LMS. The size of the file should not exceed 5 MB.

- Upload your typed (in Word or PDF format) assignments on or before the due date.

- Your own analysis and synthesis will be appreciated.

- Late assignments can’t be uploaded at LMS.

How To Write AIOU Assignments 2024 in Urdu

برائے مہربانی امتحانی مشقیں حل کرنے سے پہلے درج ذیل ہدایات کو غور سے پڑھیے۔

ہدایات برائے طلباء ایسوسی ایٹ ڈگری، بی ایس، بی ایڈ، ایم اے، ایم ایس سی، ایم ایڈ،اےٹی ٹی سی (ODLموڈ)

۔ تمام سوالات کے نمبر مساوی ہیں البتہ سوال کی نوعیت کے مطابق نمبر تقسیم ہوں گے۔

۔ سوالات کو توجہ سے پڑھیے اور سوال کے تقاضے کے مطابق جواب تحریر کیجیے۔

۔ ہاتھ سے تحریر شدہ یا سکین (scanned)کی گئی امتحانی مشقیں قبول نہیں کی جائیں گی۔ صرف اردو اور عربی میں اپنی مشقیں حل کرنے والے طلبہ اپنی ہاتھ سے لکھی ہوئی مشق سکین کر کے اپنے LMSپورٹل پر اَپ لوڈ کر سکتے ہیں۔ فائل کازیادہ سے زیادہ سائز MBہونا چاہیئے۔

۔ ٹائپ کی گئی امتحانی مشقیںword)یا PDFفارمیٹ) میں LMSپر بروقت یا مقررہ تاریخ سے قبل اَپ لوڈ کیجیے۔

۔ مقررہ تاریخ کے بعد/تاخیر کی صورت میں امتحانی مشقیں اپ لوڈ نہ ہو سکیں گی جس کی تمام تر ذمہ دار ی طالب علم پر ہو گی۔

۔ آپ کے تجزیاتی اور نظریاتی طرزِ تحریر کی قدر افزائی کی جائے گی۔

۔ غیر متعلقہ بحث / معلومات اور کتب، سٹڈی گائیڈ یا دیگر مطالعاتی مواد سے ہو بہو نقل کرنے سے اجتناب کیجیے ۔

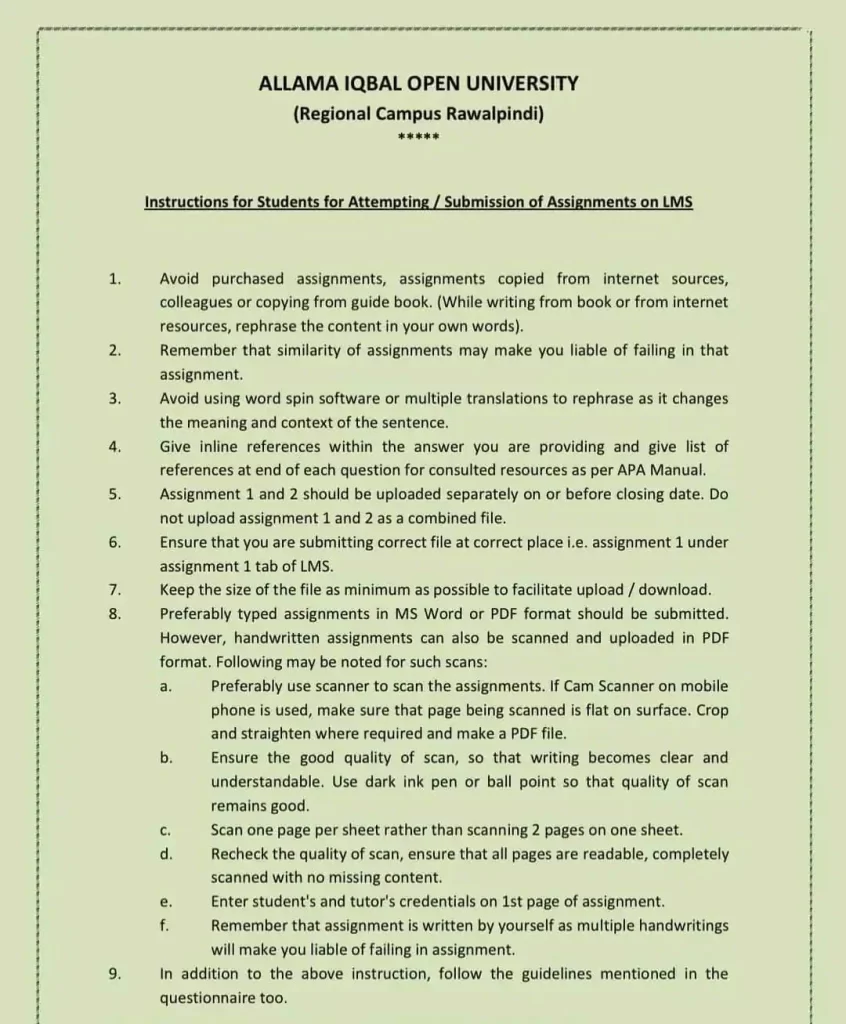

Instructions for Students for Attempting/Submission of Assignments on LMS

- Avoid purchased assignments, assignments copied from internet sources, colleagues or copying from guide book. (While writing from book or from internet resources, rephrase the content in your own words).

- Remember that similarity of assignments may make you liable of failing in that assignment.

- Avoid using word spin software or multiple translations to rephrase as it changes the meaning and context of the sentence.

- Give inline references within the answer you are providing and give list of references at end of each question for consulted resources as per APA Manual.

- Assignment 1 and 2 should be uploaded separately on or before closing date. Do not upload assignment 1 and 2 as a combined file.

- Ensure that you are submitting correct file at correct place i.e. assignment 1 under assignment 1 tab of LMS.

- Keep the size of the file as minimum as possible to facilitate upload/download.

- Preferably typed assignments in MS Word or PDF format should be submitted. However, handwritten assignments can also be scanned and uploaded in PDF format. Following may be noted for such scans:

- Preferably use scanner to scan the assignments. If Cam Scanner on mobile phone is used, make sure that page being scanned is flat on surface. Crop and straighten where required and make a PDF file.

- Ensure the good quality of scan, so that writing becomes clear and understandable. Use dark ink pen or ball point so that quality of scan remains good.

- Scan one page per sheet rather than scanning 2 pages on one sheet.

- Recheck the quality of scan, ensure that all pages are readable, completely scanned with no missing content.

- Enter student’s and tutor’s credentials on 1st page of assignment.

- Remember that assignment is written by yourself as multiple handwritings will make you liable of failing in assignment.

- In addition to the above instruction, follow the guidelines mentioned in the questionnaire too.

How To Get Grace Marks in Assignments

I know every student of AIOU always expect grace marks in assignment but he/she don’t write the outstanding assignment and just write a draft type solve assignment. Please read the following guidelines to get 90+ marks in every assignment;

- Fill your AIOU Assignment Parat (Marks Form) completely with neat and good writing style

- Presentation of Assignment is very important, Put a unique view of assignment

- Answer of each question explain in details with graphical representation

- Style of writing is always the key of success

- Always draw margin line with colourful marker and don’t write outside the margin

- Fill separate Parat for each Assignment

- Before writing any answer please use the criteria “ ANS-Q.No 1 “

- Solve the question with relevant answer and don’t write any irrelevant data

- Don’t become an over-smart by giving same answer of different question because it gives negative effect on overall assignment marks

Related Posts

Sorry, no posts were found.

21 thoughts on “AIOU Assignments Schedule 2024 Matric, FA, BA, MA, MPhil”

Respected sir aoa sir ma na six years later spring 2021 ma bcom 3 papers rhty thy admission baijha tha books bi ni aai na assignments ka liya tutors bty gy na datesheet aai jb ka ma jld sa jld mukamal krna chahti ab AP btyea ka kia kron q ka net pa daikha to papers bi ho chucky ab

You can check your tutor name from AIOU site and then you can also lodge a complain regarding books.

sir b.com ki assisment to aye hi ni ha

Sir ma ne 2021 ma BA ma admission liya but abhi tk mujhy books nhi mili only aik book mili wo b tb jb uski assignment ki last date guzr chuki the plz help kry bht worried hu

I m student of m.a urdu 2022 session mughy books b nahe mile or assignment or tutor k b koi information nahe mil rahe call p b koi information nahe mili kindly guide me kis site se mile ga ye sab .i am little bit woried

I m student of m.a 2022- 23 i have not recieved my assignment n tutor name kindly help me or guide me plz

I m student of m.a 2022- 23 i have not recieved my books kindly help me or guide me plz

I am student of m.a kindly assignment ki last date bta dain..

Am student of m.ed semester spring 2022..any update about assignment submission ?

Asslam oalikum iam student m.a islamic study spring 2022 plzz assigment sumbssion date bty dy aor tutor name bty dy plzzz books code name412,411,4622,4621

I am m.a urdu student. Mera rolnumber ka msg del o gya plz help me

BA Assignment schedule 2022?

As salami o alaikum Sir I had doubt about last date of submission of assignment due to some reasons. 4th 0ct 2022 but I had 17 Oct. What can I do now.?Can you clear me it’s PROBLEM. Thank you

You can contact your concern tutor if he/she can accept

A0A Sir, recently jo autumn 2022 k 2nd phase k m.ed k admission hoe hai us ki assignments website p nhi mil rhi. kya abhi tk upload nhi hoe assignment questions? Plz guide me.

BA assignments

I can’t log into my LMS.And no one helping/guiding me about this matter.

Autumn F.A ki assignment submission ki last date kya he kisi ko pta he ???

Mare I’d ka passward bol gaya ho msg dubara baij da

Thanks for sharing sir

Most Preferable Content .

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

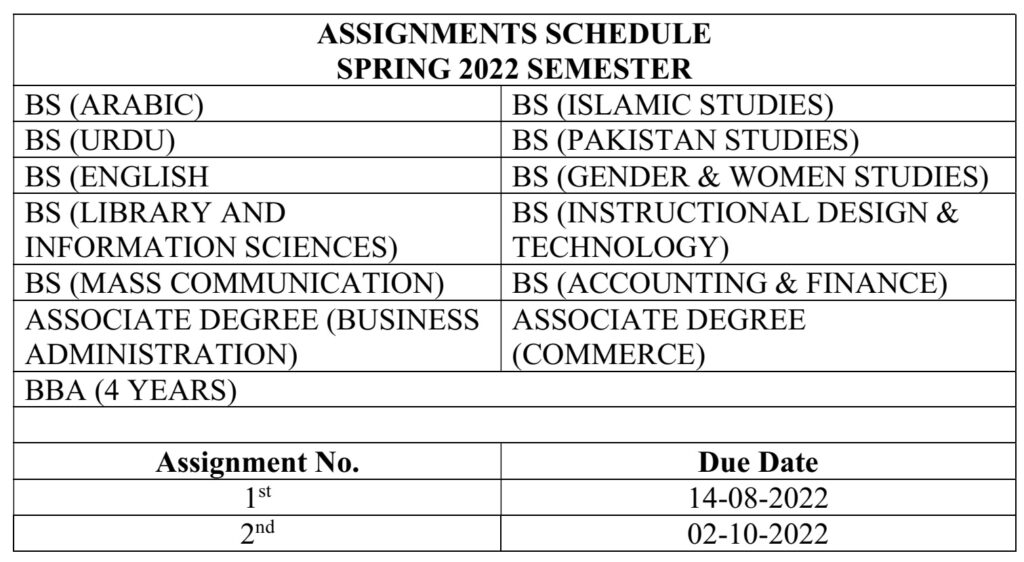

AIOU Assignments Schedule spring 2022 Matric, FA,BA,BS,B.ED,MA

last date of assignment submission aiou spring 2022 matric fa , ba.

- The assignments are also included in every educational program but the number of assignments depends on the degree. It is a golden opportunity for every student to get high marks in assignments just by following the guidelines of solving assignments according to the question papers.

- You must keep in mind the last date for the completion of the assignment and receive it at your Tutor's address before the deadline. I will advise you to keep visiting our portal to get the additional updates regarding the revision or extension of the last date or assignment date

AIOU Assignments Schedule spring 2022 BA

AIOU Assignment Schedule 2022 for BA and ADE Associate Degree Programme

AIOU Assignment Schedule Spring 2022 for B.ED Programs

AIOU Assignment Schedule Spring 2022 for BS Programs

AIOU Assignment Schedule Spring 2022 for MA Med MSc and PGD Programs

How to submit AIOU Assignment in 2022

- To submit AIOU assignments, go to http://assignment1.aiou.edu.pk/login/index.php

- Please submit your assignment to your LMS account within the specified deadlines.

- If you have any objections or questions about LMS, or account accreditations, please contact your local office.

- If it’s not too much difficulty, please keep in mind that the understudy is not qualified to appear in the Final Examinations unless he/she obtains the expected good scores on the task’s section.

You may like these posts

Aiou solved assignment.

Sidebar Posts

Social plugin, important link.

- fresh admission

- Tutor Information

- Cms account

- LMS account

- workshop information

- solved assignment spring 2023

- assignment last date 2023

- Government jobs

Popular post

How to open cms portal aiou march 28, 2022, online tutor address aiou march 28, 2022, aiou continue student online admission march 27, 2022, aiou workshop schedule autumn 2022 december 19, 2022.

- admission 40

- Admissions Open For Semester Spring 2022 29

- aiou pdf compress online 1

- aiou solved assignment 3

- AIOU solved assignments autumn 2021 1

- AIOU Solved Assignments B.ED Autumn 2021 1

- AIOU Solved Assignments BS Autumn 2021 1

- aiou tutor 1

- solved assignment 11

- New Admission

- continue student admission

- assignment/workshop marks

- Roll No slip

- lms account

- Privacy Policy

- cookie policy

- terms and conditions

Footer Copyright

Contact form.

- Help Desk

- [email protected]

- Screen Reader

- 051-111-112-468

Assignments (QP)

S.S.C., H.S.S.C.,ATTC,NFE& Literacy certificate, French Online Courses

Bachelor, ADC,ADB,BS,BBA,B.ed,Post Graduate Courses

Assignment Covering Form

S.S.C., H.S.S.C.,Arabic,NFE& Literacy certificate, French Online Courses

Bachelor, ATTC, ADC,ADB,BS,BBA,B.ed, Post Graduate Courses

Bachelor, ADC,ADB,BS,BBA,B.ed, Post Graduate Courses

S.S.C., H.S.S.C.,NFE& Literacy certificate, French Online Courses

S.S.C., H.S.S.C., French Online Courses

Bachelor, BS/BBA, B.Ed.,ATTC,CT,PTC Courses

All Post Graduate Courses

Contact info Address : Sector H-8, Islamabad [email protected] 051 111 112 468 Helpdesk --> Quick Links About Us Jobs Tender Notices Downloads Research ORIC AIOU Library For Query Email Us [email protected] (Admission) [email protected] (Examination) [email protected] (Regional Services) [email protected] (Student Advisory) [email protected] (Treasurer)

The Allama Iqbal Open University was established in May, 1974, with the main objectives of providing educational opportunities to masses and to those who cannot leave their homes and jobs. During all these past years, the University has more than fulfilled this promise.

AIOU Assignment Schedule 2024 FA, BA, Matric

Here you can check the AIOU Assignment Schedule 2024 FA, BA, Matric for Spring and Autumn semester. AIOU’s major focus is base on Female education for those who cannot manage regular institute studies. Well, this is a small introduction about AIOU, now here we are sharing AIOU Assignment Schedule 2024 FA, BA, and Matric. If you are Allama Iqbal University FA, BA, or Matric class student then keep in mind your AIOU Assignment Schedule 2024 is an issue by the concerned authority. According to University, this year number of Tutors are appointing for students’ assignment checking. You can easily get First, Second, Third, and Fourth Full AIOU Credit Assignments details. Students’ Half Credit AIOU Assignment schedule is also available on this page for your knowledge. According to AIOU officials, relaxations regarding Assignment submission dates are not AIOU policy. So, check out the assignment schedule here.

The Allama Iqbal Open University takes two admissions. One during the spring semester and the other during the autumn semester. For both the semester, it has a different schedule for each program. For instance, when we talk about the autumn semester, its assignment dates begin in November and end in February. So you can check the AIOU Assignment Schedule 2024 for both the spring and autumn semester.

AIOU Spring Assignment Schedule 2024:

CHECK SCHEDULE

For Spring Semester 2024, the assignment schedule is now announced by AIOU. The schedule is for Matric, FA, BA, B.Ed, BS, and ADE programs. So, you can check the last date of submission of the assignments of each subject here. Just click the button given above and then select the program type to check the schedule.

AIOU Autumn Assignment Schedule 2024:

For the year 2024, AIOU will announce the FA, BA, Matric, BS, B.Ed, and ADE schedule soon. So, just stay tuned with us because when the Autumn semester will start the schedule will be announced here.

Note : Avoid Copy/Plagiarized assignments.

So, this is all about AIOU Assignment Schedule 2024 FA, BA, Matric. This is a fact we are not sharing exact dates through the above table but here we are sharing exact months ideas for AIOU Assignment Schedule 2024 FA, BA, Matric. You can consider these dates at the end of the month. We will update the exact date for the announcement. Prepare your assignment for submission. The late and incomplete assignment is not acceptable by officials.

Related Articles

1st Year Admissions 2024

GIKI BS Admissions 2024

STEP by PGC Entry Test Preparation 2024

University of Sindh Merit List 2024 Bachelor, Masters

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Adblock Detected

AIOU Assignment Schedule 2024 Submission Last Date

Check Allama Iqbal Open University Islamabad Aiou st, 2nd, 3rd & 4th Assignment Schedule & Last Date 2024 For All Programs Spring/Autumn here. AIOU Assignment Submission Assignments Schedule 2024 Last Date for Matric, FA BA MA B.Ed, M.Ed, MA Education, MS/MPhil, and PhD programs have been announced. AIOU Assignment submissions for Spring 2024 will be accepted at https://lms.aiou.edu.pk. The last date of assignment submission for AIOU Spring 2024 and Autumn Semester is given below. Please visit aaghi.aiou.edu.pk login to check the Bachelor, ADC, ADB, BS, BBA, B.ed, ATTC, Post Graduate Courses assignment schedule and Assignment Covering Form. Details of Online Workshops + Assignment Submission are available at aaghi.aiou.edu.pk.

Page Contents

Last Date Of Assignment Submission Aiou Spring 2024

علامہ اقبال اوپن یونیورسٹی نے سیمسٹر خزاں دو ہزار بائیس کے میڑک اور ایف اے پروگرام کی آسانمنٹ کے سوالات اپنی ویبسائٹ پر اپلوڈ کر دیے ہیں میڑک اور ایف اے کے سٹوڈنٹس اپنی آسانمنٹ کے سوالات ویبسائٹ سے ڈونلوڈ کر کے اپنی اسائنمنٹس تیار کر سکتے ہیں. نیچے دیے گئے لنک پر کلک کر کے آسانمنٹ کے سوالات ڈونلوڈ کر سکتے ہیں

اگر اسائمنٹ نہیں لکھے تو صرف اپنے ٹیوٹر کو خبر دار کردوکہ صرف پاسنگ مارکس دیں.ورنہ فیل ہونگے

AIOU Assignment Schedule 2024

If you are looking for the latest and most reliable information about the AIOU assignment schedule 2024 for Matric, FA, BA, B.Ed, BS, MA/MSc, MEd, and PhD, you have come to the right place. The most up-to-date deadline information for Spring and Fall semesters’ worth of homework is available on this page. Thousands upon thousands upon thousands of Pakistani students (both male and female) are receiving their education from home through the AIOU, the country’s leading provider of home-based education.

AIOU Assignment Submission Last Date 2024

Read Also , How to Become a Tutor in AIOU?

Remember that your assignment is due at the AIOU Tutor’s address on or before the specified date. As such, I recommend that you bookmark this page and check back frequently for any notices of deadline changes or extensions.

What is the last date of assignment submission in Aiou 2024?

The latest date for submission of the first full course assignment is 2024, whereas the last date for submission of the second exercise is 2024.

How to Submit Assignments on AIOU Aaghi Portal LMS Online?

To access her account, follow the link provided below to the official website, where you will be prompted to enter your User Name and Password.

Then, select the course you wish to submit work for on the aghee site by clicking the My Courses option. The image I am providing here is a snapshot of the pdf file that the aaghi site LMS offers its users.

They may easily complete their assignment by following the on-screen prompts that appear once they click the Assignment link for submission.

You may pursue him down by clicking the Add Submissions button on the page that loads after this one.

You may verify this by going to the page that loads next and clicking the file icon there.

The following graphic depicts the window that will appear. To submit your assignment, first choose the appropriate file from your computer, then click the “Upload” option. Word documents and PDFs are also acceptable for submission.

A confirmation screen will load, and then you may hit the “Save” button to save your changes.

Leave them alone. You may make as many changes to your submission as you’d like up to the due date. The same goes for the submission status page that will load below this post’s verification link.

AIOU Assignment Spring 2024

Every year, Allama Iqbal Open University (AIOU) makes two admissions announcements: in the fall and the spring. Every semester features a unique timetable.

AIOU Assignment Submission Form 2024 Download

Everyone is reminded that the Director General of Regional Services has kindly allowed for the submission deadline for Matric and FA programs for the Spring 2024 semester to be pushed back in light of the current circumstances around the country. The new date is as shown below.

The instructors should be informed accordingly by all regional heads. Students need to be informed, and the school, local libraries, and other community facilities may all help by posting flyers and other information in visible locations.

M.Hadi is a professional education content writer, who have 10 year plus experience in writing. The 50% content of eduhelp.pk is written by the Hadi. He is working on the categoris like Results, Merit list and Roll number slip.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Autumn 2022 Assignments

علامہ اقبال اوپن یونیورسٹی کی حل شدہ اسائنمنٹس۔ پی ڈی ایف۔ ورڈ فائل۔ ہاتھ سے لکھی ہوئی، لیسن پلین، فائنل لیسن پلین، پریکٹس رپورٹ، ٹیچنگ پریکٹس، حل شدہ تھیسس، حل شدہ ریسرچ پراجیکٹس انتہائی مناسب ریٹ پر گھر بیٹھے منگوانے کے لیے واٹس ایپ پر رابطہ کریں۔ اس کے علاوہ داخلہ بھجوانے ،فیس جمع کروانے ،بکس منگوانے ،آن لائن ورکشاپس،اسائنمنٹ ایل ایم ایس پر اپلوڈ کروانے کے لیے رابطہ کریں۔

WhatsApp:03038507371

Recent posts, 8618 school leadership, 8617 plan implementation and educational management, 8616 school administration, 8615 management strategies, 8614 educational statistics, 8612 professionalism in teaching, 8611 critical thinking and reflective practices, 8609 philosophy of education, 8606 citizenship education and community, 8605 educational leadership, to get all aiou assignments contact us on whatsapp.

WhatsApp Us Get Unique Assignments

Unique Assignments are also available. To Order Unique Assignments Contact us on WhatsApp

Copyright © All rights are reserved

AIOU Assignment Schedule 2023 | Check Online Last Date All Programmes

Are you are a students of AIOU and looking to see for AIOU Assignment Schedule 2023 Spring Semester? Or worried about the last date of the assignment? No need to worry. Allama Iqbal Open University AIOU assignment submission last date 2023 for Matric, FA, BA, MA, B.Ed(Old/New), M.Ed MPhil, PhD, and other programs.

According to the schedule, the last date of summation is 1st, 2nd, 3rd & 4th assignments for the full credit course in February, March, April and April respectively. This page is to facilitated AIOU students can access all the information of the assignment schedule according to their programs. You can, however, check the AIOU spring 2023 assignment submission deadline.

AIOU Assignment Schedule 2023 Autumn/Spring

Here, you can easily access the latest spring/autumn assignment schedule of all AIOU programs. AIOU is proud of its extensive undergraduate and postgraduate programs in a variety of academic disciplines.

Related Post:

How to Submit Assignments on AIOU

AIOU Assignment Marks 2023 | Check Assignment Result Online

AIOU Matric Assignment Schedule Autumn 2023

Every citizen in this country has the right to do matriculation education. Thanks to Virtual Education. If any students do not have access to a computer or laptop, they can complete the assignments by writing them using pages. Once done, they can send their assignments via regular mail to their teacher.

Matric class students with very young experience who are not familiar with Microsoft World but can submit their assignments using pages. You can easily download Assignment Schedule of AIOU Matric before the assignment deadline 2023.

AIOU FA Assignment Schedule 2023

Recently, the university released the assignment schedule for a variety of intermediate courses, including Dars e Nizami, FSC, Arts and Commerce Group, ICOM, ICS, and FA. Each course has multiple subjects. Each subject has at least assignments. The table of Inter assignments schedule is given below.

AIOU Assignment Schedule BA 2023

Here, aioulearn will provide you with the AIOU BA Assignment Schedule. It is very important to note that for some courses, particularly 6-credit hour ones, students are required to submit 4 assignments in single semester.For 6-credit hour courses, the last assignment dates are as follows:

For BA and AD 2-year degree programs in the spring season, a total of 8 assignments are expected. 2 assignments must be submitted before the examination by the deadline. 3-credit hour courses, the last assignment dates are as follows:

AIOU B.Ed. BS BBA & Post Graduate Programs Assignment Schedule

Graduation isn’t limited to two-year programs; it also includes four-year programs.

AIOU Assignment Schedule BS ATTC ADC 2023

AIOU’s Bachelor of Science assignment schedule for 2.5 and 4 year degrees is available here online and downloadable.

Can I submit assignments after due date(with fine)?

Assignment submission is dependent on AIOU study center. You can submit your assignments even after the official deadline. To do this, Communicate with your program coordinator and make sure they are aware of your problem.

How do I extend my assignment date?

Tips for Requesting an Extension 1. Read your syllabus or assignments. 2. Ask your instructor as soon as possible. 3. Reach out by email for specific request. 4. If possible ask for a shooter extension. 5. Show your dedication to the course.

What is a good reason for an assignment extension?

Some the difficulties that students might face are: 1. Physical health include: Illnesses, injuries and critical health problems. 1. Mental health issues like: Depression, anxiety, or nonstop or long-term internal health diseases. 2. Bereavement: Because of the death of a family member, a guardian, or relationship, or other personal and emotional losses. 3. Financial difficulties: such as losing a job, unexpected changes to your financial aid package, or unexpected unemployment.

Similar Posts

Aiou assignment marks 2024 | check spring/autumn assignment result online.

Do you want to check how many AIOU Assignments Marks you got in finals? Or do you want to know the passing marks for assignments? Or might be assignment percentage in the finals! In this article we will discuss about all the solutions. Basically the purpose of the assignments is to make the student study…

How to Submit Assignments on AIOU | Online Aaghi Portal LMS

Allama Iqbal Open University (AIOU) is committed to making the learning process easier for its students. Recently, AIOU introduced a new online Learning Management System (LMS) called the Aaghi LMS Portal. The platform provides many different valuable features aimed at enhancing the learning experience and student interaction with the university. Agahi LMS portal is designed…

AIOU BA BCom BS BEd Assignments Last Date Autumn 2022

AIOU BA BCom BS BEd Assignments Last Date Autumn 2022 : For 9th and 10th-grade matriculation students, the Allama Iqbal Open University BA, BCom, BS, and BEd Assignments Schedule for the Autumn Semester 2022 has been rel eased. Parts I and II are available for free download at aiou.edu.pk. The schedule was sent out to students in the BA, BCom, BS, and BEd programs at the Allama Iqbal Open University.

Each semester, the institute will say when the final submission date is for each program. This is done so that individuals will have information regarding the duration of the assignment that will be given to the students who will be attending session 2023 to earn a degree in one of the many programs.

It is not simple to determine when the AIOU Assignment’s due date for the 2023 BA will be, but we will notify you about it on this page. For that goal, you can visit our site at brainacademy1.com, which is uploading the most recent news about the assignment that has been finished.

AIOU BA BCom Assignments Autumn 2022 Last Date 2022 :

This page has a link to the website where Allama Iqbal Open University puts all of its candidates’ program courses and diploma certificate assignments. Here, we also show him a good way to get AIOU Spring 2023 FA-solved assignments. This is because we are giving him a way to get AIOU Spring 2023 FA-solved assignments.

The AIOU MA Assignments Schedule 2023 is now available on the university’s website, which is good news for students who want to attend Allama Iqbal University. The best and most original thing about the study is that it gives you a lot of information and prepares you for work through education. The AIOU Admission Fee Structure 2023 is used every day to check the qualifications of thousands of people who want to get into this university.

We are providing you with access to the most recent AIOU Assignment Schedule for Autumn 2023 for all of the students so that they may see it online and download it for free here without having to pay anything since we are sharing with you the most recent AIOU Assignment Schedule.

AIOU B.Ed BS Assignments Schedule Autumn 2022:

Now, in the end, we’ll post the AIOU Assignment Schedule 2022 Autumn Semester Programs for B.ED. 1.5, 02, 2.5, and 04 years so that students can easily download them for free.

ASSIGNMENTS SCHEDULE AUTUMN 2022 SEMESTER :

- B.Ed (1.5 Years)

- B.Ed (4 Years)

- B.Ed (2.5 Years)

- ADE (2 Years)

ASSIGNMENTS SCHEDULE AUTUMN 2022 SEMESTER:

- BS (ARABIC)

- BS (ISLAMIC STUDIES) BS (PAKISTAN STUDIES)

- BS (ENGLISH

- BS (GENDER & WOMEN STUDIES) BS (INSTRUCTIONAL DESIGN &

- BS (LIBRARY AND

- INFORMATION SCIENCES)

- TECHNOLOGY)

- BS (MASS COMMUNICATION) ASSOCIATE DEGREE (BUSINESS

- BS (ACCOUNTING & FINANCE)

- ADMINISTRATION) BBA (4 YEARS)

- ASSOCIATE DEGREE

Other Information:

Govt New Jobs Apply Now

AIOU BA BCom Exam Results Autumn 2022:

Top Best 3 Apps To Earn Money Online At Home:

Ehsaas Kafalat Program Online Registration 2023:

Khalifa University Scholarship Intake for 2023 (UAE) | Fully Funded :

1 thought on “AIOU BA BCom BS BEd Assignments Last Date Autumn 2022”

- Pingback: AIOU Spring 2023 Admissions Open Today's Latest News | Aiou Spring 2023 Admission Deadline

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Intermediate F.A I.Com Solved Assignments Autumn 2022

Aiou master academy solved assignments.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Allama Iqbal Open University was established in May, 1974, with the main objectives of providing educational opportunities to masses and to those who cannot leave their homes and jobs. During all these past years, the University has more than fulfilled this promise.

To stay updated with our latest resources, we recommend that you subscribe to our AIOU Studio 9 YouTube channel, where we regularly upload informative videos related to AIOU and its programs. Intermediate (FA/ICOM) 2 years program. Solved Assignments of Spring / Autumn 2023. 1. 2.

Allama Iqbal Open University AIOU Assignment Schedule Autumn 2022 Semester. Matric, FA, BA, Associate Degree Programs, BS ... AIOU Assignment Schedule for Matric & FA Programs. 6 Credit Hours Course Last Date 3 Credit Hours Course Last Date; Assignment No 1: 05-12-2022: Assignment No 1: 31-12-2022: Assignment No 2: 31-12-2022: Assignment No 2: ...

16th July to 19th August (04 Weeks) 16th January to 14th February (04 Week) Test/Interview. 20th August to 25th August (01 Week) 17th February to 24th February (01 Week) Enrollment Finalization. 1st Merit list: 28th August (Morning) Dues/Fee: 2nd September. 2nd merit list: 3rd September.

AIOU Assignments Submission Dates of Autumn 2022 For Matric, F.A, and B.A For BS, B.Ed, and All Post Graduate Programmes ... Matric/Fa Autumn 2022 Result Announced. 15/06/2023. AIOU Assignment Posting Dates. 03/06/2023. Comments Now. Leave a Reply Cancel reply. Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Half Credit (3 Credit Hours) Book Assignment Submission Date Spring 2021. Assignment No 1. 20-02-2021 (Extended) Assignment No 2. 20-02-2021. These all books are present in PDF, you can easily avail these in your any device which can open the PDF file. Read Also: Download FREE AIOU Solved Assignments in PDF.

Title: Date Sheet AD, ADE, ADC BEd Autumn 2022 Author: Muhammad Hameed Created Date: 4/11/2023 9:11:55 AM

AIOU Announced Assignment Schedule 2023-24 Last Date: Allama Iqbal Open University (AIOU) has recently announced the new schedule of AIOU Assignments submission for Matric, FA, Darse Nizami and ICOM students throughout Pakistan.You can submit your all assignments as per schedule date and after the due date no assignment will be submitted or entertained.

AIOU Matric FA ICOM BA BCom BEd and BS Assignment Last Date Autumn 2022: Students in 9th and 10th class matriculation, Parts I and II, can get the Allama Iqbal Open University Matric Assignments Schedule for the Autumn Semester 2022 for free at aiou.edu.pk.. The institute announces the last day to turn in work for each semester's program so that people know when the work given to the ...

this vedio related to aiou autumn 2022 assignment. in which discuess the autumn 2022 matric and FA assignment last. watch complete to check method to view me...

So you can check the AIOU Assignment Schedule 2022 for both the spring and autumn semester. For Spring Semester 2022, the assignment schedule is now announced by AIOU. The schedule is for Matric, FA, and BA, and programs. So, you can check the last date of submission of the assignments for each subject here. Just click the given image and check ...

Semester Autumn 2022. S.S.C., H.S.S.C.,NFE& Literacy certificate, French Online Courses. ... Instructions for Writing Assignments . Read more. Contact info. Address : Sector H-8, Islamabad; [email protected]; 051 111 112 468 ; ... The Allama Iqbal Open University was established in May, 1974, with the main objectives of providing educational ...

ALLAMA IQBAL OPEN UNIVERSITY (Directorate of Regional Services) ... Assignment No. Due Date 1st 13-02-2023 2nd 03-04-2023 ASSIGNMENTS SCHEDULE FOR PGD/MA/M.ED/M.SC (ODL) PROGRAMS: AUTUMN 2022 SEMESTER Assignment No. Due Date 1st 27-02-2023 2nd 10-04-2023 Note: - For workshop schedule, please login to your LMS account or visit

For Spring Semester 2024, the assignment schedule is now announced by AIOU. The schedule is for Matric, FA, BA, B.Ed, BS, and ADE programs. So, you can check the last date of submission of the assignments of each subject here. Just click the button given above and then select the program type to check the schedule.

AIOU Assignment Submission Last Date Extended 2024. August 19, 2023 by Mohsin Raza. AIOU Assignment End Date 2024 deadline. This applies to Matric BA, FA, MA, B. AIOU Assignment Scheduling 2024: Autumn Semester 2024 of BEd B.S. PGD MEd MSc has been made public by Management.

AIOU Assignment Submission Assignments Schedule 2024 Last Date for Matric, FA BA MA B.Ed, M.Ed, MA Education, MS/MPhil, and PhD programs have been announced. AIOU Assignment submissions for Spring 2024 will be accepted at https://lms.aiou.edu.pk. The last date of assignment submission for AIOU Spring 2024 and Autumn Semester is given below.

Autumn 2022 Assignments. Previous Homepage. Next AIOU Solved Assignments Spring 2023.

December 26, 2022 by Brain Academy. AIOU Matric FA ICOM Assignment Last Date Autumn 2022: Allama Iqbal Open University Matric Assignments Schedule, Autumn Semester 2022, can be downloaded for free at aiou.edu.pk by students in 9th and 10th class matriculation, Parts I and II. The institute announces the last day to turn in work for each ...

For BS, B.Ed, and All Post Graduate Programmes. You can submit your Handwritten 5MB scanned or 5MB PDF Format Assignments to your Aaghi LMS Portal Online. 1. Allama Iqbal Open University ASSIGNMENTS :-. First and foremost Assignments are an essential part of the students. Because this plays a very important role.

Allama Iqbal Open University AIOU assignment submission last date 2023 for Matric, FA, BA, MA, B.Ed (Old/New), M.Ed MPhil, PhD, and other programs. According to the schedule, the last date of summation is 1st, 2nd, 3rd & 4th assignments for the full credit course in February, March, April and April respectively.

AIOU BA BCom BS BEd Assignments Last Date Autumn 2022: For 9th and 10th-grade matriculation students, the Allama Iqbal Open University BA, BCom, BS, and BEd Assignments Schedule for the Autumn Semester 2022 has been released.Parts I and II are available for free download at aiou.edu.pk. The schedule was sent out to students in the BA, BCom, BS, and BEd programs at the Allama Iqbal Open University.

Introduction to Economics. Waiting for Assignments. 1349. Introduction to Business Math. View Assignments. 1350. Introduction to Business Statistics. View Assignments. Intermediate F.A I.Com Solved Assignments Autumn 2022 Download All F.A Assignments Free | aioumasteracademy.com.