A Case Study on Endometriosis

Endometriosis is a chronic reproduction condition that still remains a mystery to the medical community. This paper starts off by providing the background information on what endometriosis is, the etiology, and risk factors associated with the condition. Following the introduction is a case study on a 20 year old female who currently suffers from the condition herself. Based on Patient X’s life, the end of this paper focuses on the prognosis she has as far as living with the disease goes, and things she can change in her lifestyle to improve her symptoms.

qnk322f06z_version1_Endometriosis_Case_Study.docx

size: 24.6 KB | mime_type: application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document | date: 2015-04-16

- V1 published November 16, 2020

Collections

This resource is currently not in any collection.

Work History

Version 1 published.

November 16, 2020 23:39 by Scholarsphere 4 Migration

- Open access

- Published: 26 January 2022

Challenges of and possible solutions for living with endometriosis: a qualitative study

- Gabriella Márki 1 , 2 ,

- Dorottya Vásárhelyi 2 ,

- Adrien Rigó 2 ,

- Zsuzsa Kaló 2 ,

- Nándor Ács 3 &

- Attila Bokor 3

BMC Women's Health volume 22 , Article number: 20 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

14 Citations

29 Altmetric

Metrics details

Endometriosis as a chronic gynecological disease has several negative effects on women’s life, thereby placing a huge burden on the patients and the health system. The negative impact of living with endometriosis (impaired quality of life, diverse medical experiences) is detailed in the literature, however, we know less about patients’ self-management, social support, the meaning of life with a chronic disease, and the needs of patients. To implement a proper multidisciplinary approach in practice, we need to have a comprehensive view of the complexity of endometriosis patients’ life and disease history.

Four focus group discussions were conducted between October 2014 and November 2015 by a team consisting of medical and psychological specialists. 21 women (age: 31.57; SD = 4.45) with surgical and histological confirmation of endometriosis were included in the study. Discussions were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim, and a 62,051-word corpus was analyzed using content analysis.

Four main themes emerged from the analysis: (1) the impact of endometriosis on quality of life, (2) medical experiences, (3) complementary and alternative treatments, and (4) different coping strategies in disease management. All themes were interrelated and highly affected by a lack of information and uncertainty caused by endometriosis. A supporting doctor-patient relationship, active coping, and social support were identified as advantages over difficulties. Finding the positive meaning of life after accepting endometriosis increased the possibility of posttraumatic growth. Furthermore, women’s needs were identified at all levels of the ecological approach to health promotion.

Conclusions

Our results highlight the need for multidisciplinary healthcare programs and interventions to find solutions to the difficulties of women with endometriosis. To achieve this goal, a collaboration of professionals, psychologists, and support organizations is needed in the near future.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Endometriosis is a chronic inflammatory disease that is defined as the presence of endometrium-like tissues outside the uterus causing pain symptoms (dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, chronic pelvic pain) and infertility [ 1 ]. This gynecological disease affects approximately 2–10% of the reproductive-aged and 50% of infertile women, and women with endometriosis have increased risk of obstetric outcome [ 2 ]. Because symptoms are not specific, the diagnostic delay is almost 8–10 years [ 3 ].

Endometriosis has a negative impact on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [ 4 ]. Quantitative studies identified deterioration in physical wellbeing [ 5 ], psychological functioning [ 6 , 7 ], daily life activities and work productivity [ 8 , 9 ], social participation [ 10 ], quality of sexual life [ 11 ], and an increase in financial burden [ 12 ]. Decreased HRQoL has a negative feedback effect on endometriosis progression [ 13 , 14 ]. Furthermore, it is already known that pain is a major cause of these physical, psychosocial, emotional, and work-related difficulties among patients [ 15 , 16 , 17 ].

Previously published qualitative data demonstrated the negative impact of endometriosis on HRQoL and medical experiences but offered fewer findings of self-management, social support, femininity, the meaning of life with a chronic disease, and future directions and needs of patients. Therefore, this study aims to expand knowledge of (i) the difficulties women have when living with endometriosis and (ii) their opportunities and mechanisms for coping with the negative impact of the disease. We assume that by exploring these main areas we can help to develop health promotion strategies to reduce further negative effects on women's lives.

Study design, procedure, and data collection

This qualitative study is part of a comprehensive study on the psychosocial aspects of endometriosis conducted by Eötvös Loránd University in conjunction with Semmelweis University, Budapest, Hungary. Participants with surgical and histological confirmation of endometriosis from our previous study [ 18 ] were invited via e-mail to participate in exploratory focus group discussions, where participation was voluntary. The invitation explained the nature and details of the study. Four focus group discussions were conducted in the department room of the Institute of Psychology, Eötvös Loránd University between October 2014 and November 2015. Within the postpositivist qualitative paradigm [ 19 ] we followed the phenomenological approach to inquiry. Focus groups allow data to be collected through a group, where participants express their opinion more naturally and influence one another, thus it is more likely that new issues will be raised than in a one-to-one interview. Furthermore, focus groups allow the perceptions, emotions, and concerns of participants to be explored [ 20 , 21 ].

Focus group participants were asked to articulate their concerns and experiences on two topics: (i) living with endometriosis, (ii) disease-management, and experiences of medical or other treatments. All conversations were guided by the first author and trained assistant, who took field notes. Focus groups were audiotaped with their permission and transcribed verbatim by the assistant. Overall, there were 462 min of recording which were then transcribed into a 62,051-word corpus for the analysis.

The verbatim transcripts included typical or relevant non-verbal expressions (laughing, long pauses) that were confirmed by the assistant who made observations during focus group sessions. The basic element of analysis was the word. After checking the transcript (rereading the text while listening to the voice recording), the text was analyzed line by line using content analysis [ 22 , 23 ] in ATLAS.ti by two independent coders [ 24 ]. They discussed and compared collected codes from the data and after reaching consensus code groups, defined categories and created themes. Final themes and categories were checked against codes [ 22 ].

Sample characteristics

The study involved 21 patients diagnosed with endometriosis with a mean age of 31.57 (SD = 4.45). Participants (> 18 years) represented a homogenous group in terms of socio-economic background and ethnicity. On average, participants saw more than three gynecologists (range 1–15) and one alternative healer (range 0–4) before being diagnosed with endometriosis. The diagnostic delay was 2.05 years (SD = 3.32; range 0–12). Most participants (66.7%) had endometriosis-related symptoms by the time of the study. In all our participants, peritoneal endometriosis was observed (21/21, 100%), ovarian endometriosis was found in 11 patients (11/21, 52.3%) while deep infiltrating endometriosis affecting the rectum and/or the rectovaginal space was present in 6 cases (6/21, 28.6%). None of our patients had extrapelvic or abdominal wall endometriosis. Most patients of the whole sample used medical hormonal treatment at the time of the conversation. From the whole cohort, 18 (18/21, 85.7%) women received combined oral contraceptive therapy on a continuous regimen. We have observed no difference between the types of oral contraceptives since they were all combined pills containing dienogest and ethinylestradiol. Most of our participants (16/21) struggled to get pregnant, only one of them had a successful clinical pregnancy and delivery at the time of the conversation, further 23.8% of participants were undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF). None of study participants had a comorbid psychiatric disorder.

Thematic analysis findings

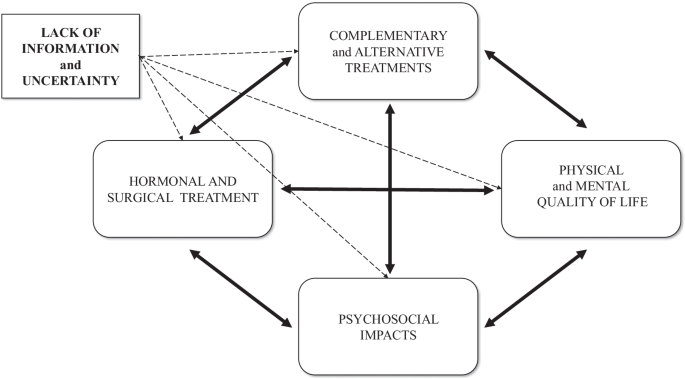

Four main themes emerged from the analysis: (a) impact of endometriosis on quality of life, (b) medical experiences, (c) complementary and alternative treatments, (d) different coping strategies in disease-management (Table 1 ). Notably, that all themes were highly affected by a lack of information and uncertainty related to endometriosis, while all the emerged themes showed a dynamic connection between them and present the patients’ circular pathways (Fig. 1 ).

A model of the dynamic relationship of endometriosis-related themes and negative impacts

Theme 1: Impact of endometriosis on quality of life

Physical impacts.

Most women mentioned chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, and dyspareunia as leading symptoms of their endometriosis. Most of them reported that pain killers or special body positions did not significantly relieve pain.

It was never-ending, so I lived like this every day. I kneeled on the ground. I moved back and forth because it was not good any other way and yet I still held tightly onto my hair because I was in so much pain.

Psychological impacts

Besides the physical burden, participants also reported psychological consequences of endometriosis, namely anxiety, stress, and helplessness , and sometimes these were more confusing and annoying than the physical symptoms. One participant described how depressing it was to realize that she had lost 10 years of her life living in permanent pain without receiving the correct diagnosis and treatment. Feelings of loss and shame were also highlighted by participants. Uncertainty about the possible recurrence of the disease has been identified as a further stress factor in women who wanted to take an active role in their disease management. The negative emotional state negatively shaped their way of thinking, and subsumed their everyday lives.

You can’t do anything about the physical side anymore, but the psychological aspects, they leave their mark on you. I gave in to endometriosis, in fact, my whole life revolved around it. It made me bitter, and I realized after a while that I couldn’t think about anything else.

The psychosocial effects of endometriosis

This category includes common and cumulative effects of physical and psychological impacts. Endometriosis-related uncertainty had several negative impacts on women’s life. Families and friendships were affected by a lack of adequate information and a feeling of helplessness.

Friendships were ruined at that time. There was not one aspect of my life that was not affected by endometriosis. Within the family, you can release the stress that you cannot release anywhere else. It was common for me to cry during family dinners. Even friends who were supportive did not always understand what I was going through.

Intimate relationships were negatively affected by uncertainties. Participants mentioned that explaining the disease and giving reassurance to their husbands was difficult. Women agreed that a supportive partner can be the biggest source of help and support, but not every relationship was able to handle the burden of endometriosis.

It [endometriosis] cost me my marriage… At that time, we had already started in vitro fertilization. The first one ended up in colonic obstruction and I got a stoma for three months. Before the next round of IVF started my ex-husband said it was over for him.

Some women experienced sexual problems and the inconvenience of sharing their experiences of dyspareunia due to the normalizing reaction of society and health care providers. The non-sharable experiences led in two cases to sexual aversion, when “ sex was equal to pain”.

Besides dyspareunia and sexual dysfunctions, the most burden for most women were fertility problems. Participants stated that they pursued one of two options: some women insisted on childbearing and did not give up even after the defeats and inconveniences of IVF, because they thought it was worth the sacrifice; others re-evaluated pregnancy and went on to consider other options for motherhood.

We try and we hope, and I don’t know. I have learned a big lesson from this—that it would be nice to have a baby, but what if I can never have my own baby—because it could happen. Now I can say it out loud: it is okay, I can adopt a child or choose other options.

Female identity was negatively affected by infertility, sexual problems, and impersonal medical examinations. Repression and negative attitudes towards femininity have been mentioned as possible causes of their disease.

If you do not experience your femininity, it will come back to haunt you at some point.

Endometriosis and its treatment had a significant impact on participation in education and employment . Women mentioned sick-leave and semester deferral due to dysmenorrhea, as well as sleeping problems and surgery. The impact on employment usually depended on the boss and the flexibility of the workplace.

It can cause a lot of tension, finding where the line is between asking your boss to let you leave and be patient, or feeling that you are risking your job and tomorrow maybe you don’t have to go to work anymore.

The cost of gynecological consultations, medications, surgery, healthy nutrition, and further treatments caused a financial burden and required a considerable amount of time and energy .

The costs associated with endometriosis are so high; my family has an emergency budget just for this.

Theme 2: Medical experiences

Diagnostic delay.

Participants usually experienced that health professionals normalized symptoms of dysmenorrhea. It was not only normalization but physicians’ lack of adequate knowledge relating to endometriosis that caused misdiagnosis and diagnostic delay.

I went from doctor to doctor for seven years and I knew something was wrong because I could not conceive, so we were looking for the reason behind it. But a lot of doctors did not recognize the disease and that was the biggest problem.

Treatment of endometriosis

The option of pharmacological treatments was divisive among participants; most of them were concerned about side effects. Participants reported being fearful before surgery and stated that they were concerned about reproductive organs and intestinal involvement or getting stoma. Fear and uncertainty were pronounced concerning recovery and lack of information right after surgery. Participants reported that having a child was usually expressly recommended by gynecologists as a potential treatment option . These women often experienced medical and social pressure to have a baby, even if they did not feel ready to become mothers.

A woman can find herself in this trap. Although the gynecologist means well, saying you must have a child as soon as possible is such a burden on the woman. It is unbearable and impossible to process.

Infertility was a sensitive topic in every discussion. Participants who underwent assisted reproductive technology treatment described it as impersonal, physically, and mentally stressful, for men as well. Furthermore, the possible recurrence of endometriosis proved to be one of the biggest uncertainty factors, and it placed a huge burden on women.

Doctor-patient relationship

Most women agreed that having a good, reliable gynecologist specialized in endometriosis is one of the most essential factors in managing endometriosis. Many participants had negative experiences with doctors who were negligent or had insufficient professional knowledge of endometriosis, which increased diagnostic delay by several years. Women highlighted that healthcare professionals’ uncertainty led to mistrust, increased fear, and despondency, and caused them to go ‘doctor-shopping’ because they could not accept their doctor’s negligent attitude towards their symptoms or recommended treatment options. All the women agreed that physicians who reassured and informed them properly as a specialized professional in endometriosis engendered the most trust.

It was an odd experience, that even doctors can’t tell me what is wrong with me and what will make me feel better. So, you have to go until you find someone you can at least trust.

Theme 3: Complementary and alternative treatments

This theme includes women’s motivation towards all kinds of complementary and alternative treatments which may supplement or substitute medical treatments.

Lifestyle changes as treatment

Despite a lack of scientific evidence and findings of the positive effects of lifestyle change , women wanted to achieve better physical health and HRQoL and long-term recovery.

You have to be very conscious and responsible and need an incredible amount of time to develop this routine. I was exhausted and I wanted nothing more than to go to bed, but I knew if I did not prep my lunch for the next day, then I wasn’t going to have a [healthy] meal.

These women were given a great deal of contradictory information about their potential endometriosis diet . Those following a strict diet said it was like being a prisoner and they suffered because of the financial cost. When the diet was ineffective or too strict, women gave in and started to follow the needs of their bodies and developed a unique, personalized diet.

When I accidentally ate something, which was forbidden in the diet I would hate myself. Now I listen to my body, the things it likes or does not like.

Although it is difficult to find enough time and mobilize resources, all women agreed that physical activity is an essential part of managing the disease. Women were doing various sports (yoga, running, cycling, Zumba, swimming, intimate muscle training, and Pilates) regularly, but the efficacy of these sports was not specified during discussions.

Due to the unknown etiology of the disease, participants stated that they had thought about the psychosomatic, stress-related origin of endometriosis. Many women sought psychological help by using cognitive methods, schema therapy, EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing), stress management, autogenic training, meditation, and hypnosis to alleviate their symptoms.

I went to a psychologist, and I opened up about this stuff [dyspareunia]. She pointed out things that I could not see myself, and for some reason, I believe that if I defeat this misery the endometriosis will disappear, too.

Naturopathy and other methods

A wide range of naturopathic medicine (acupuncture, reflexology, Chinese medicine, Ayurveda, kinesiology, herbs) was mentioned in focus group discussions. When women find no answer in western medicine, they seek help through alternative treatments.

Then I decided to start taking a path which I normally would not take, as the path that I am currently on is not working.

Participants were not able to agree about the impact of the aforementioned methods, because each woman had a different view of those effects.

Theme 4: Different coping strategies in disease-management

Obtaining information.

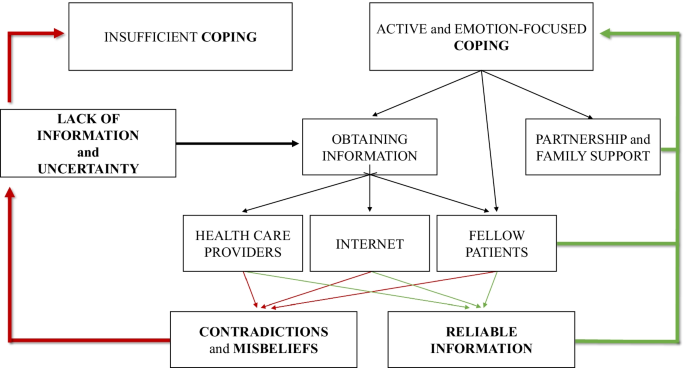

One of the most important aspects of disease-management was obtaining reliable information. Women were motivated to access as much information as possible, however, it was the area with the most obstruction. Contradictory information increased the feeling of uncertainty (see Fig. 2 ). Insufficient information from health care professionals also increased uncertainty . Only some women felt that they were properly informed by their gynecologists, and many of them found that they had to drag the information out of their doctors. After the diagnosis, some participants were sent home to read about endometriosis on the internet .

When you are sent home to look into it on the internet, it’s like being thrown into the sea in order to teach you how to swim.

The model of sufficient and insufficient ways of coping with endometriosis

All women experienced that the internet is full of contradictions and misconceptions . Furthermore, destructive opinions, negative experiences, and rumors from fellow patients on blogs and online forums often confused them. Some women learned the most about endometriosis from fellow patients in the waiting room, where they were able to exchange experiences and inform one another. However, they also drew attention to the distress they had experienced.

We [fellow patients] can understand each other’s problems because we are in the same boat, but if I get no positive feedback and I can’t say anything to her that she needs, it’s not good.

Active control and emotion-focused coping

Women described a wide range of active and emotion-focused coping mechanisms they need to be able to use flexibly. In addition to obtaining information, most women avoided passivity and took control, assuming an active role and self-care in managing endometriosis. Some women stated that since changing their lifestyle, they have been able to live a full life. Others mentioned the importance of listening to the signs and needs of their bodies. Many participants coped with the difficulties and uncertainty of endometriosis by having a positive attitude , trying to find the positive aspects, and trying to remain optimistic.

Endometriosis taught me to take care of myself, and try to heal myself, to listen to my body and my inner voice, to look for methods that might help, and to find those which really help.

Social support

All women agreed on the importance of social support and support from their partners . “I cannot tell you how much it helps when he [male partner] stands by you.” They were able to cope with living with endometriosis, operations, and treatment thanks to the personal support of relatives and friends . Several participants mentioned the important role played by endometriosis community members, who can give support by sharing intimate experiences of endometriosis so that women do not have to face their problems alone.

It is always nice to get support from others who have experienced similar things and similar problems, so it feels good to talk about it. You are not alone.

Positive meaning of life after accepting endometriosis

Women described the difficulties, uncertainties, and lack of information surrounding endometriosis as pervasive features of their lives. Nevertheless, despite many difficulties and problems, women described a positive impact ( peace, patience, openness, personality development, and gratitude ) on their life after accepting their condition.

A whole new world has opened up before me. I am not saying that it is good to have endometriosis, but I have completely changed because of it. I would not be the same person if I had not gone through this. I improved as a person, and the journey is not over yet. I would not be as open towards people, I would not have these kinds of relationships, my family and my relationship would not be the same. I have a sense of purpose.

Possible responses to “do patients know what they need?”

Focus group discussions allowed women with endometriosis to demonstrate their desire to take an active role in the management of their disease and to express their needs and options for alleviating the difficulties and deficiencies. These suggestions allow us to understand the real needs of women with endometriosis and design a proper health promotion program.

Giving proper information from reliable sources could be one of the best ways of reducing uncertainty and increasing HRQoL. Participants highlighted the need for information about surgical results right after the postoperative wake-up, which would reduce postoperative stress, anxiety, and uncertainty.

Women suggested that diagnostic delay, the risk of misdiagnosis, and the normalization of dysmenorrhea could be reduced through more extensive training and by improving the specialist knowledge of a broader range of health care professionals and medical students in all related medical areas in relation to the recognition of endometriosis.

Almost every woman agreed that clinical or health psychologists are needed in hospitals to help cope with diagnosis and surgery and to process disease-management.

All women agreed on the importance of raising awareness of endometriosis by involving male partners, friends, and colleagues. Educating and informing men about endometriosis would have long-term advantages, as men could provide effective help and support to women with endometriosis. Women highlighted the fact that it could also be very stressful for men to be involved, and that because of many uncertainty factors there should be educational and supportive groups for men as well.

To prevent more severe conditions, participants agreed that awareness of and education about endometriosis is necessary from menarche. Preventive and educational programs relating to endometriosis in schools would help ensure the early diagnosis of future patients.

Furthermore, women stated that it is a social responsibility to increase publicity and awareness of endometriosis in society, and a campaign like that for breast cancer would help to educate all social groups.

In our study, we first report a mutual dynamic connection between the main endometriosis-related themes (HRQoL, medical experiences, complementary and alternative treatment, and coping strategies), and show that these areas are negatively influenced by the most prominent themes: uncertainty and lack of information. Exploring the connections between these themes will also help to understand patient pathways, which is essential for planning the long-term management of women with endometriosis.

Identified topics are comparable with previous findings [ 25 , 26 ], where negative impact on HRQoL and medical experience of endometriosis appeared as essential topics. Our results highlight that these themes are not independent of one another (see Figs. 1 , 2 ). Prolonged (pain)symptoms of endometriosis decrease quality of life, and direct women to health care, where patients can face a variety of different experiences. An inadequate doctor-patient relationship affects not only medical experiences and the physical condition of patients but also impairs adherence, compliance, and HRQoL. Ineffective medical attention or treatment affects women’s relationship with healthcare and leads them to use (non)evidence-based alternative treatments. Patients need active, emotion-focused coping strategies which are properly supported by positive medical experiences, reliable information, and effective social support. In their absence, patients may use inadequate coping options, which can have a negative impact on HRQoL. Lifestyle change as a potential coping and disease-management strategy [ 27 ] is an obvious opportunity for women to have control over one aspect of their condition. Nonetheless, the effectiveness of nonmedical treatments in endometriosis has not been sufficiently explored by evidence-based medicine [ 3 ]. Our results highlight the importance of finding a scientific response to women’s questions because failed attempts have a negative impact on prognosis, quality of life, and self-esteem [ 25 ].

Uncertainty and lack of information can have a direct impact on HRQoL, medical experiences, coping, and indirectly, on fertility as well [ 15 ]. The normalization and rejection of symptoms as a general problem impact the doctor-patient relationship before diagnosis and leads to diagnostic delay and eliminates the benefits of early diagnosis [ 3 ].

The lack of information at health care centers causes women to seek self-management strategies [ 15 , 28 , 29 ]. The lack of information causes women to seek self-management strategies. Women try to obtain information from various sources, but they come across a great deal of contradictory information, which needs to be dealt with. Studies identified that becoming assertive and taking control can be a potential coping mechanism before diagnosis and treatment [ 28 ], but there are fewer findings of how women cope with endometriosis and achieve an asymptomatic and fertile life after diagnosis. The women in our study used positive emotion-focused coping strategies to focus on the positive and optimistic aspects of their lives. Besides, problem-focused coping (versus non-adaptive focus on emotions) was found as an adaptive and assertive coping strategy that correlates with lower stress and depressive symptoms. [ 30 ]. On the other hand, catastrophizing is a negative cognitive and emotional coping response to pain [ 31 ] and enhances pain perception as a predictor among women with endometriosis [ 32 ]. Roomaney and Kagee [ 33 ] highlight—in line with our results—that both problem-focused and positive emotion-focused coping strategies can be helpful for women with endometriosis. A third means of coping is based on the help and support provided by personal relationships and endometriosis communities. Strong relationships were characterized by admiration for women’s courage, independence, and inner strength [ 34 , 35 ]. Self-help groups and endometriosis foundations can provide effective support to women from the individual (see reliable information; health promotion programs) [ 36 ] to society (see social awareness and publicity) [ 37 , 38 ].

In addition to negative consequences and needs, there were some interesting findings supporting the results of Facchin et al. [ 22 ] about finding the meaning of life with endometriosis. Women with positive emotion-focused coping strategies and a lower level of stress can accept the disease and find positive meaning in their lives from endometriosis. These results suggest the possibility of posttraumatic growth (PTG) in endometriosis. PTG is defined as the “positive psychological change experienced as a result of the struggle with highly challenging life circumstances” [ 39 ] (e.g. chronic disease as trauma or danger to health). Previous studies on women with chronic disease identified that PTG is negatively associated with age, depression, and stress, while positively associated with time since diagnosis, education, income, social support, mental HRQoL, self-efficacy, self-esteem, and optimism [ 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 ]. These characteristics show similarities with predictors of mental health quality in endometriosis [ 18 , 45 ], although to the author’s knowledge PTG in endometriosis patients has not been measured yet. The authors suggest that PTG may occur due to multiple health behavior changes which improve active coping and the patient’s sense of control [ 46 , 47 , 48 ]. Therefore, it is recommended that the possibility of PTG be explored in future endometriosis studies.

The authors acknowledge that are some limitations to the current study. Firstly, the study sample was low and consisted of participants with homogeneous demographic and disease characteristics. Secondly, we collected our data retrospectively. We asked women about their experiences about living with endometriosis without making differences in the pre- and post-operative period, because we wanted to collect all the affected areas in their life. Although there can be differences before and after the endometriosis surgery for example in the quality of sexual life [ 49 ]. These differences can be analyzed in further qualitative studies.

Thirdly, as endometriosis is a benign disorder, the primary objective of any treatment should be to alleviate symptoms, control progression, and improve quality of life. Laparoscopic surgery is the most widely accepted surgical approach in cases of peritoneal, ovarian, and deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) [ 3 , 50 , 51 ]. Peritoneal disease can be excised or vaporized using different energy sources, while ovarian endometriosis can be managed by cystectomy or ablation. According to the recent data the ovarian cystectomy may lead to the loss ovarian reserve [ 52 ]. The optimal type of colorectal resection in case of bowel DIE, whether conservative (shaving, disc resection) or radical technique (segmental bowel resection) has to be applied is under discussion [ 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 ]. It has been suggested that the conservative surgical therapy of colorectal DIE is associated with lower morbidity, however the unequivocal evidence supporting this hypothesis is still lacking. The external validity of present data regarding the surgical therapy of endometriosis should be investigated in future multicentric prospective randomized trials on a large cohort of patients. A clear limitation of our study is that we did not assess the impact of different surgical methods on the endometriosis related quality of life in our group of patients.

Further, as a result of the recruitment process predominantly women with active coping strategies and an optimistic attitude applied to take part in the study. Thirdly, the themes that emerged were facilitated by means of predetermined questions, and participants would have continued conversations in three areas. This may cause some limitations to the possible themes and topics of endometriosis discussed (e.g. symptoms, medical and surgical experiences).

Finally, coping strategies and PTG in endometriosis would have been identified by using appropriate questionnaires.

Uncertainty and lack of information about endometriosis as main challenges and difficulties have a significant impact on women’s life. The present findings indicate that cooperation between health care professionals, psychologists, and support organizations will be necessary for the future to provide care and find possible solutions to the needs of women living with endometriosis. Communication must be improved, and psychosocial problems need to be recognized by health care providers to ensure that empathetic care is provided. Having evidence-based answers about the efficiency of alternative and complementary therapies could decrease the uncertainty and lack of information. Furthermore, in order to reduce diagnostic delay, health care providers’ knowledge and society’s awareness of endometriosis should be improved in the near future. Health promotion programs and support groups should be managed to facilitate coping and posttraumatic growth in women with endometriosis. Achieving these recommendations would allow women to live an asymptomatic, fertile, and balanced life with endometriosis.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Infiltrating endometriosis

- Health-related quality of life

In vitro fertilization

Posttraumatic growth

Giudice LC, Kao LC. Endometriosis. The Lancet. 2004;364(9447):1789–99.

Article Google Scholar

Berlanda N, Alio W, Angioni S, Bergamini V, Bonin C, Boracchi P, et al. Impact of endometriosis on obstetric outcome after natural conception: a multicenter Italian study. Arch Gynecol Obstet; 2021.

Dunselman GAJ, Vermeulen N, Becker C, Calhaz-Jorge C, D’Hooghe T, De Bie B, et al. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl. 2014;29(3):400–12.

Article CAS Google Scholar

D’Alterio MN, Saponara S, Agus M, Laganà AS, Noventa M, Loi ES, et al. Medical and surgical interventions to improve the quality of life for endometriosis patients: a systematic review. Gynecol Surg. 2021;18(1):13.

De Graaff AA, D’Hooghe TM, Dunselman GAJ, Dirksen CD, Hummelshoj L, WERF EndoCost Consortium, et al. The significant effect of endometriosis on physical, mental and social wellbeing: results from an international cross-sectional survey. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl. 2013; 28(10):2677–85.

Pope CJ, Sharma V, Sharma S, Mazmanian D. A systematic review of the association between psychiatric disturbances and endometriosis. J Obstet Gynaecol Can JOGC J Obstet Gynecol Can JOGC. 2015;37(11):1006–15.

Smorgick N, Marsh CA, As-Sanie S, Smith YR, Quint EH. Prevalence of pain syndromes, mood conditions, and asthma in adolescents and young women with endometriosis. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26(3):171–5.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Fourquet J, Gao X, Zavala D, Orengo JC, Abac S, Ruiz A, et al. Patients’ report on how endometriosis affects health, work, and daily life. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(7):2424–8.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Nnoaham KE, Hummelshoj L, Webster P, d’Hooghe T, de Cicco NF, de Cicco NC, et al. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: a multicenter study across ten countries. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(2):366-373.e8.

Gilmour JA, Huntington A, Wilson HV. The impact of endometriosis on work and social participation. Int J Nurs Pract. 2008;14(6):443–8.

Barbara G, Facchin F, Buggio L, Somigliana E, Berlanda N, Kustermann A, et al. What is known and unknown about the association between endometriosis and sexual functioning: a systematic review of the literature. Reprod Sci Thousand Oaks Calif. 2017;1:1933719117707054.

Google Scholar

Simoens S, Dunselman G, Dirksen C, Hummelshoj L, Bokor A, Brandes I, et al. The burden of endometriosis: costs and quality of life of women with endometriosis and treated in referral centres. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl. 2012;27(5):1292–9.

Laganà AS, La Rosa VL, Rapisarda AMC, Valenti G, Sapia F, Chiofalo B, et al. Anxiety and depression in patients with endometriosis: impact and management challenges. Int J Womens Health. 2017;9:323–30.

Tariverdian N, Theoharides TC, Siedentopf F, Gutiérrez G, Jeschke U, Rabinovich GA, et al. Neuroendocrine-immune disequilibrium and endometriosis: an interdisciplinary approach. Semin Immunopathol. 2007;29(2):193–210.

Culley L, Law C, Hudson N, Denny E, Mitchell H, Baumgarten M, et al. The social and psychological impact of endometriosis on women’s lives: a critical narrative review. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19(6):625–39.

Facchin F, Barbara G, Saita E, Mosconi P, Roberto A, Fedele L, et al. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and mental health: pelvic pain makes the difference. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;36(4):135–41.

Moradi M, Parker M, Sneddon A, Lopez V, Ellwood D. Impact of endometriosis on women’s lives: a qualitative study. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14:123.

Márki G, Bokor A, Rigó J, Rigó A. Physical pain and emotion regulation as the main predictive factors of health-related quality of life in women living with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(7):1432–8.

Ponterotto JG. Qualitative research in counseling psychology: A primer on research paradigms and philosophy of science. J Couns Psychol. 2005;52:126–36.

Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2014.

Morgan DL. The focus group guidebook, vol. 1. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1997.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Joffe H, Yardley L. Content and thematic analysis. In: Research methods for clinical and health psychology. 2004th ed. California: Sage; 2004. p. 56–68.

Creswell JW. Qualitative research design and inquiry: choosing among five approaches. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc.; 2007.

Facchin F, Saita E, Barbara G, Dridi D, Vercellini P. “Free butterflies will come out of these deep wounds”: A grounded theory of how endometriosis affects women’s psychological health. J Health Psychol. 2017;11:1359105316688952.

Young K, Fisher J, Kirkman M. Women’s experiences of endometriosis: a systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2015;41(3):225–34.

Buggio L, Barbara G, Facchin F, Frattaruolo MP, Aimi G, Berlanda N. Self-management and psychological-sexological interventions in patients with endometriosis: strategies, outcomes, and integration into clinical care. Int J Womens Health. 2017;9:281–93.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Cox H, Henderson L, Andersen N, Cagliarini G, Ski C. Focus group study of endometriosis: struggle, loss and the medical merry-go-round. Int J Nurs Pract. 2003;9(1):2–9.

Cox H, Henderson L, Wood R, Cagliarini G. Learning to take charge: women’s experiences of living with endometriosis. Complement Ther Nurs Midwifery. 2003;9(2):62–8.

Donatti L, Ramos DG, de Andres MP, Passman LJ, Podgaec S. Patients with endometriosis using positive coping strategies have less depression, stress and pelvic pain. Einstein Sao Paulo Braz. 2017;15(1):65–70.

Sullivan MJL, Lynch ME, Clark AJ. Dimensions of catastrophic thinking associated with pain experience and disability in patients with neuropathic pain conditions. Pain. 2005;113(3):310–5.

Martin CE, Johnson E, Wechter ME, Leserman J, Zolnoun DA. Catastrophizing: a predictor of persistent pain among women with endometriosis at 1 year. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl. 2011;26(11):3078–84.

Roomaney R, Kagee A. Coping strategies employed by women with endometriosis in a public health-care setting. J Health Psychol. 2016;21(10):2259–68.

Culley L, Law C, Hudson N, Mitchell H, Denny E, Raine-Fenning N. A qualitative study of the impact of endometriosis on male partners. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl. 2017;15:1–7.

Fernandez I, Reid C, Dziurawiec S. Living with endometriosis: the perspective of male partners. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61(4):433–8.

Shoebotham A, Coulson NS. Therapeutic affordances of online support group use in women with endometriosis. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(5):e109.

Richard L, Potvin L, Kishchuk N, Prlic H, Green LW. Assessment of the integration of the ecological approach in health promotion programs. Am J Health Promot AJHP. 1996;10(4):318–28.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Facchin F, Saita E, Barbara G, Dridi D, Vercellini P. Free butterflies will come out of these deep wounds: A grounded theory of how endometriosis affects women’s psychological health. J Health Psychol. 2017;23:538–49.

Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Posttraumatic growth: conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol Inq. 2004;15(1):1–18.

Barskova T, Oesterreich R. Post-traumatic growth in people living with a serious medical condition and its relations to physical and mental health: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31(21):1709–33.

Danhauer SC, Case LD, Tedeschi R, Russell G, Vishnevsky T, Triplett K, et al. Predictors of posttraumatic growth in women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2013;22(12):2676–83.

Koutrouli N, Anagnostopoulos F, Griva F, Gourounti K, Kolokotroni F, Efstathiou V, et al. Exploring the relationship between posttraumatic growth, cognitive processing, psychological distress, and social constraints in a sample of breast cancer patients. Women Health. 2016;56(6):650–67.

Wang M-L, Liu J-E, Wang H-Y, Chen J, Li Y-Y. Posttraumatic growth and associated socio-demographic and clinical factors in Chinese breast cancer survivors. Eur J Oncol Nurs Off J Eur Oncol Nurs Soc. 2014;18(5):478–83.

Yeung NCY, Lu Q. Perceived stress as a mediator between social support and posttraumatic growth among Chinese American breast cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2016;41:53.

Facchin F, Barbara G, Dridi D, Alberico D, Buggio L, Somigliana E, et al. Mental health in women with endometriosis: searching for predictors of psychological distress. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(9):1855–61.

Fong AJ, McDonough MH, Pila E, Sabiston CM. Posttraumatic growth in breast cancer survivors: the roles of physical activity and social support. J Exerc Mov Sport. 2017;49(1):165.

Hawkes AL, Pakenham KI, Chambers SK, Patrao TA, Courneya KS. Effects of a multiple health behavior change intervention for colorectal cancer survivors on psychosocial outcomes and quality of life: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Behav Med Publ Soc Behav Med. 2014;48(3):359–70.

Love C, Sabiston CM. Exploring the links between physical activity and posttraumatic growth in young adult cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2011;20(3):278–86.

Di Donato N, Montanari G, Benfenati A, Monti G, Leonardi D, Bertoldo V, et al. Sexual function in women undergoing surgery for deep infiltrating endometriosis: a comparison with healthy women. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2015;41(4):278–83.

Redwine DB, Sharpe DR. Laparoscopic segmental resection of the sigmoid colon for endometriosis. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1991;1(4):217–20.

Bokor A, Hudelist G, Dobó N, Dauser B, Farella M, Brubel R, et al. Low anterior resection syndrome following different surgical approaches for low rectal endometriosis: a retrospective multicenter study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100(5):860–7.

Younis JS, Shapso N, Ben-Sira Y, Nelson SM, Izhaki I. Endometrioma surgery-a systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect on antral follicle count and anti-Müllerian hormone. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021; S0002-9378(21)00788-2.

Bokor A, Lukovich P, Csibi N, D’Hooghe T, Lebovic D, Brubel R, et al. Natural orifice specimen extraction during laparoscopic bowel resection for colorectal endometriosis: technique and outcome. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25(6):1065–74.

Hudelist G, Aas-Eng MK, Birsan T, Berger F, Sevelda U, Kirchner L, et al. Pain and fertility outcomes of nerve-sparing, full-thickness disk or segmental bowel resection for deep infiltrating endometriosis—a prospective cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2018;97(12):1438–46.

Roman H, Bubenheim M, Huet E, Bridoux V, Zacharopoulou C, Daraï E, et al. Conservative surgery versus colorectal resection in deep endometriosis infiltrating the rectum: a randomized trial. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl. 2018;33(1):47–57.

Borghese G, Raimondo D, Esposti ED, Aru AC, Raffone A, Orsini B, et al. Preoperative ureteral stenting in women with deep posterior endometriosis and ureteral involvement: Is it useful? Int J Gynaecol Obstet Off Organ Int Fed Gynaecol Obstet. 2021.

Seracchioli R, Raimondo D, Arena A, Zanello M, Mabrouk M. Clinical use of endovenous indocyanine green during rectosigmoid segmental resection for endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2018;109(6):1135.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Szilvia Kassai of the Institute of Psychology, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary, for her expert and methodological advice in relation to this study, and Boglárka Kristóf, a psychology student at Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary, for her help with the pilot analysis.

Open access funding provided by Semmelweis University. There were no external sources of funding for this study. We acknowledge the significant contribution of the author’s workplaces, the Institute of Psychology, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest 1064, Hungary and Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Semmelweis University, Budapest 1085, Hungary.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Doctoral School of Psychology, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, 1064, Hungary

Gabriella Márki

Institute of Psychology, Eötvös Loránd University, Izabella Street 46, Budapest, 1064, Hungary

Gabriella Márki, Dorottya Vásárhelyi, Adrien Rigó & Zsuzsa Kaló

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, Semmelweis University, Baross Street 27, Budapest, 1088, Hungary

Nándor Ács & Attila Bokor

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

G.M., A.R., N.Á., and A.B. were involved in designing this study. G.M., A.B., and N.Á. helped recruit participants. G.M. and D.V. corrected the database verbatim. G.M., D.V., Z.K., and A.R. were involved in the analysis and interpretation of data. This manuscript was drafted by G.M., V.D., Z.K., and A.R., and A.B. edited the article. All the authors have approved the final draft.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Attila Bokor .

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate..

This study was approved by the Regional, Institutional Research and Ethics Committee of Semmelweis University, Budapest, Hungary (registration number TUKEB 60/2014), and the work was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was provided by all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Márki, G., Vásárhelyi, D., Rigó, A. et al. Challenges of and possible solutions for living with endometriosis: a qualitative study. BMC Women's Health 22 , 20 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01603-6

Download citation

Received : 22 September 2021

Accepted : 14 January 2022

Published : 26 January 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01603-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Endometriosis

- Psychosocial impact

- Focus group

BMC Women's Health

ISSN: 1472-6874

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Imaging of Endometriosis: The Role of Ultrasound and Magnetic Resonance

- GLOBAL RADIOLOGY (J FRENCHNER, SECTION EDITOR)

- Open access

- Published: 18 February 2022

- Volume 10 , pages 21–39, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Valentina Testini 1 , 2 ,

- Laura Eusebi 3 ,

- Gianluca Grechi 4 ,

- Francesco Bartelli 3 &

- Giuseppe Guglielmi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4325-8330 1 , 2 , 5

10k Accesses

Explore all metrics

Endometriosis is a chronic gynecological disease characterized by the growth of functional ectopic endometrial glands and stroma outside the uterus. It causes pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, or infertility. Diagnosis requires a combination of clinical history, non-invasive and invasive techniques. The aim of the present review was to evaluate the contribution of imaging techniques, mainly transvaginal sonography and magnetic resonance imaging to diagnose different locations and for the most appropriate treatment planning. Endometriosis requires a multidisciplinary teamwork to manage these patients clinically and surgically.

Similar content being viewed by others

Magnetic resonance imaging for deep infiltrating endometriosis: current concepts, imaging technique and key findings

Filomenamila Lorusso, Marco Scioscia, … Arnaldo Scardapane

- Endometriosis

Endometriosis: clinical features, MR imaging findings and pathologic correlation

Pietro Valerio Foti, Renato Farina, … Giovanni Carlo Ettorre

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Endometriosis is a common gynecological inflammatory condition that is defined as functional ectopic endometrial glands and stroma outside the uterus. This disease affects women of reproductive age, with a prevalence of approximately 10% [ 1 ]. Patients can be asymptomatic or present with chronic pelvic pain and/or infertility.

The phenotypes of endometriotic lesions can be divided into three groups: pelvic endometriosis, ovarian endometriomas (OMA) and deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) [ 2 ]. In particular, pelvic endometriosis is defined as the presence of any endometrial tissue within the pelvic cavity, including the peritoneum, within any of the pelvic organs and inside the pouch of Douglas (POD). Ovarian endometriosis, an endometrioma, is defined as an ovarian cyst, of different size, lined by endometrial tissue. DIE is defined as endometriotic tissue that penetrates the retroperitoneal space for a distance of 5 mm or more and may be present in multiple locations, involving anterior or posterior pelvic compartments, or both [ 3 ]. Posterior DIE, a multifocal disease that may affect a variety of anatomical sites, represents the most common type of DIE [ 4 ]. The most typical sites of DIE include uterosacral ligaments (USL), rectovaginal septum (RVS), vaginal wall, POD and bowel, predominantly below the rectosigmoid junction. Anterior DIE corresponds to disease involving the anterior pouch or bladder and is much less common. DIE is a source of pain and infertility [ 5 ].

A frequently association with endometriosis is represented by adenomyosis, a disease characterized by infiltration of endometrial tissue into the myometrium [ 6 ].

Etiopathogenesis

Although the pathogenesis of endometriosis has not been fully elucidated, it is commonly thought that endometriosis occurs when endometrial tissue contained within menstrual fluid flows retrogradely through the fallopian tubes and implants at an ectopic site within the pelvic cavity [ 7 ]. In this process, menses transports viable endometrial fragments through the fallopian tubes to the peritoneal cavity, where they are able to implant, develop and sometimes invade other tissues of the pelvis [ 8 ]. In favor of this hypothesis is that all known factors that increase menstrual flow are also risk factors for endometriosis, including early age at menarche, heavy and long periods as well as short menstrual cycles [ 9 ]. The anatomical distribution of endometriotic lesions can also be explained by the hypothesis of retrograde menstruation as endometriotic lesions tend to have an asymmetrical distribution, which could be explained by the effect of gravity on menstrual flow, the abdominopelvic anatomy and the peritoneal clockwise flow of menses [ 10 ]. However, this theory does not explain the fact that although retrograde menstruation is seen in up to 90% of women, only 10% of women develop endometriosis [ 3 ]. Moreover retrograde menstruation does not explain the mechanism of endometrial tissue grafting onto the peritoneum. It is therefore evident that a variety of environmental, immunological and hormonal factors contribute to the onset of endometriosis, with mechanisms not yet known [ 11 ].

Genetic factors play an important role in the genesis of endometriosis, with an up to six times greater risk of developing the disease for first degree relatives of patients with endometriosis [ 12 ]. Despite this clear inheritance, the identification of the genetic factors that drive the disease is still incomplete.

The first step in diagnosing DE is to establish the patient's clinical history with particular emphasis on symptoms (dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, dysuria, dyschezia, and chronic pelvic pain) as well as, age, height, weight, ethnic origin, gravidity, parity, previous surgery for endometriosis, family history of endometriosis, previous non-surgical treatment for endometriosis, and infertility. No symptom is specific to endometriosis [ 13 ].

However, several authors have underlined the poor relationship between symptoms exhibited by patients and the severity of the lesions rendering clinical diagnosis difficult. Moreover, it is thought that up to 50% of women could have asymptomatic endometriosis [ 14 , 15 ].

The second step is based on physical examination including a systematic analysis of the posterior vaginal fornix with a speculum to look for retraction and dark nodules. Digital examinations should be performed of the vagina to assess the characteristics of the uterus and adnexa, of the vesicouterine pouch to detect bladder invasion, and of the retrocervical area to detect infiltration of the torus uterinus, uterosacral ligaments (USLs), pouch of Douglas (POD), vagina, and rectovaginal septum (RVS) [ 13 ]. Rectal digital examination can help in assessing the involvement of the rectum, parametrium and visceral pelvic fascia. In the particular setting of DE, few data are available to evaluate the accuracy of physical examination. One retrospective study found that routine clinical examination detected DE in only 36% of 140 women with DE, and the authors suggest the accuracy of physical examination improves during menstruation [ 16 ]. To detect rectosigmoid and retrocervical DE without differentiating between the different specific DE locations, Abrao et al. reported that digital vaginal examination had a sensitivity of 72% and 68%, a specificity of 54% and 46%, respectively [ 17 ].

Laboratory tests are limited in the diagnosis of endometriosis (CA-125 has a detection rate of only 54% in patients with severe endometriosis 5 and is neither sensitive nor specific for the diagnosis) [ 18 ].

The gold standard for diagnosis of endometriosis is based on laparoscopy or surgery with histological verification of endometrial glands and/or stroma.

Imaging is needed to diagnose endometriosis and to plan treatment. The techniques used are transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the latter should be considered as a second-line technique after ultrasound [ 1 ].

Treatment of endometriosis is complicated and involves conservative approaches combined with medical therapies or surgery. Imaging is crucial to guide the type of treatment. The American Society for Reproductive Medicine Practice Committee states that “endometriosis should be viewed as a chronic disease that requires a lifelong management plan with the goal of maximizing the use of medical treatment and avoiding repeat surgical procedures” [ 18 ]. Current treatment is essentially surgical, medical, or a combination of both approaches. To this end, many patients are stratified for medical treatment with or without surgical treatment based on symptom severity or imaging results and desire to have children, with medical therapy typically including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, oral contraceptives, androgens, progestogens and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) and/or surgery [ 19 ].

Laparoscopy is an effective surgical approach with the goal of excision of visible endometriosis in a hemostatic fashion. Radical surgery is reserved for those patients with severe symptoms where there is no desired fertility potential and especially when other forms of treatment have failed. Total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy are performed along with resection of any endometriotic lesions as completely as possible [ 4 ].

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) is typically the initial imaging evaluation performed in patients with pelvic pain and infertility or when there is clinical suspicion for endometriosis. This examination is widely available with low relative cost and the sensitivity and specificity for detection of ovarian endometriomas and lesions in the rectal wall are high [ 18 ].

All patients should be examined systematically and carefully using an endocavitary sonography, with a microconvex array probe inserted transvaginally or transrectally. Both techniques are optimal approaches for examining uterus (including the different uterine zones: cervix, endometrium, junctional zone, and myometrium), adnexa, paracolpium, parametrium, vesicocervical, vesicovaginal, and rectovaginal spaces as well as urinary bladder, ureters, and rectum [ 20 ].

Limitations of sonographic technique include anterior compartment detection of endometriosis (bladder and vesicouterine pouch detection) and detection within the middle compartment (torus uterinus and round ligaments) [ 18 ].

The pelvic localization of endometriosis can be described according to three compartments (central, anterior, and posterior) according to functional and clinical relevance [ 21 ]. The anterior compartment includes the insertion site of the ureters, the bladder, the vesicouterine pouch, and the vesicovaginal pouch. The middle compartment contains the uterine body, fallopian tube, and uterine ligaments. The posterior compartment contains the uterosacral ligaments, rectovaginal septum, anterior rectal wall, and sigmoid colon [ 21 ].

Recently, the IDEA (International Deep Endometriosis Analysis group) published a consensus report 18 on the appropriate terms, definitions, and measurements that may be used to describe the sonographic features of the different phenotypes of endometriosis. A standardized pelvic TVS approach is proposed by this IDEA report consisting in four step pelvic evaluation [ 22 ]:

Evaluation of uterus and ovaries:

Evaluation of uterus: 2D–3D sonographic signs of adenomyosis

Evaluation of the adnexa: presence or absence of endometrioma or tubal pathology

Evaluation of TVS organ mobility (adhesions): adnexa and uterine mobility site-specific tenderness

Pouch of Douglas (POD) assessment using real-time ultrasound-based “sliding sign”

Assessment for DIE nodules in anterior lateral and posterior compartments

Anterior Compartment

The anterior compartment is comprised of the urinary bladder, the vesicouterine pouch, round ligaments and ureters. Involvement of the urinary tract occurs in approximately 1–2% of patients with endometriosis and involves bladder in 85% of these cases [ 23 ]. Ureteric involvement is found in 4% of patients with rectovaginal endometriosis [ 24 ]. The prevalence of round ligament endometriosis is estimated between 4.3% and 13.8% [ 25 ].

Bladder endometriosis is considered only in case of infiltration of the bladder wall and not in case of adhesions or superficial peritoneal implants on the bladder serosa.

Before TVS scan, patients are asked not to empty completely the bladder, because the slightly filled bladder permits to better evaluate the structure of the walls.

On ultrasound, bladder endometriosis appears as hypoechoic lesion, either containing cystic lesions or not, with regular/irregular margins of the bladder wall, bulging toward the lumen, involving the serosa, muscularis (most common), or (sub)mucosa of the bladder [ 26 ].

In the assessment of the bladder DIE localization, the bladder wall can be divided into three zones: the trigonal zone and vesical base; the vesical dome (which lies superior to the trigone and is intra-abdominal) and the anterior retroperitoneal bladder. Most frequently bladder endometriosis is located in the vesical dome on the posterior bladder wall close to the vesicouterine pouch [ 27 ].

Bladder adhesions of the vesicouterine pouch are evaluated by the presence or absence of the “sliding sign” between the uterus and the bladder [ 28 ].

During examination, from a longitudinal section through the cervix and moving the probe toward the lateral pelvic wall, it is possible to assess the distal part of the ureter adjacent to the bladder trigone, in order to evaluate the presence of stenosis and subsequent cephalad dilatation of the pelvic ureters. This finding can suggest direct invasion or compression of the ureter by endometriotic nodules, ovarian endometriomas, or adhesions [ 28 ].

The prevalence of ureteral endometriosis ranges from 0.01 to 1% of all patients with the disease and most often affect the distal segment of the ureter [ 29 ]. There are two types of endometriosis involvement of ureters: (1) extrinsic that represents 75–80% of the cases and is defined as the presence of endometrial tissue in the outer adventitia of the ureter that occurs as a nodule encasing the ureter by extension from pelvic foci; (2) intrinsic that represents 20–25% of cases and is defined as the presence of endometrial tissue in the mucosal and/or muscular layer of the ureter. Imaging signs are nodule or mass occurring in the ureter along its course, dilatation of the pelvic ureteral tract, or ureteropelvic hydronephrosis superior to the suspected lesion [ 22 ]. Pelvic ureteral dilation can be easily seen by TVS as a tubular anechoic image, very similar to a blood vessel but with negative color/power Doppler signs. An extrinsic compression, also without ureteral dilatation, is suspected in cases where a DIE lesion is located close to the ureter. The observation of a possible ureteral involvement requires transabdominal ultrasound to evaluate the renal pelvis. In all women with DIE, a transabdominal scan of the kidney to search for ureteral stenosis is necessary because the prevalence of endometriotic lesions in the urinary tract may be underestimated and women with DIE involving the ureter may be asymptomatic [ 30 ].

A review of the literature for bladder endometriosis reveals a reported mean US sensitivity of 55% and specificity of 93.5% [ 31 ].

For vesicouterine pouch endometriosis, two series reported US sensitivities and specificities of 16.7% and 33% and 99% and 100% [ 32 ]. These discrepant results could be partly explained by selection bias of inclusion among studies.

Central Compartment

The central compartment includes uterus and adnexa.

Adenomyosis is characterized by the migration and proliferation of endometrial glands and stroma from the basal layer of endometrium into the myometrium. It is associated with smooth muscle hyperplasia leading to an ultrasound image of ill-defined lesions within the myometrium [ 22 ].

Recently, the ultrasound features have been systematically described by the international Morphological Uterus Sonographic Assessment (MUSA) group [ 33 ].

According to the MUSA consensus, adenomyosis should be described as localized and diffuse.

Adenomyosis is classified as diffuse, if the total involvement of myometrium exceeds 50% of the corpus uteri (when the findings are present in only one part of the myometrium on one or more sites within the uterine wall), and localized (or focal) when less than 50% of myometrium is involved (one or more lesions) [ 33 ]. An adenomyoma is defined as a focal consolidation of endometrial glands and or endometrial stroma located within the myometrium with additional compensatory hypertrophy of the surrounding myometrium [ 27 ]. In rare cases it may present as a large cyst (adenomyotic cyst or cystic adenomyoma, with largest diameter 2 mm and echogenic rim) [ 34 ].

To evaluate adenomyosis, the size of the lesions should be measured (in particular the largest diameter of each focal lesion or the myometrial wall thickness in cases of a diffuse lesion), the involvement of the uterine layers and of the extent of the disease, based on the estimated volume of the uterine corpus affected by adenomyosis (mild < 25%, moderate 25–50%, and severe > 50%) [ 27 , 35 ].

According to several studies, there are different features associated with adenomyosis visible on 2D transvaginal sonographic [ 33 ].

On ultrasound, an adenomyotic uterus appears with a globular shape, enlarged dimensions, and uterine wall asymmetry. The myometrium typically appears inhomogeneous on gray-scale, characterized by the presence of an indistinctly defined area with either decreased or increased echogenicity with myometrial hypoechoic linear striations [ 36 ]. Round anechoic areas of 1-mm to 7-mm diameter, named myometrial cysts, also could be present within the myometrium [ 36 ]. In cases of focal adenomyosis, the adenomyotic lesion appears as a heterogeneous and hypoechogenic area within the myometrium, usually with anechoic lacunae or cysts with ill-defined contours and fan-shaped shadowing. These hypoechogenic areas reflect muscular hypertrophy of the myometrial tissue [ 27 ]. Irregularities of the endometrial-myometrial junctional zone is another common ultrasound marker in the diagnosis of adenomyosis [ 27 ]. This endomyometrial interface is normally visualized as hypoechoic tissue layer seen beyond the endometrial basal layer. In women with adenomyosis, the diffuse or focal hyperplasia and hypertrophy of myocytes determine whether diffuse or focal thickening of this zone is seen [ 37 ].

A characteristic sign is the “question mark sign” defined when the corpus uterus was flexed backward, the fundus of uteri was facing the posterior pelvic compartment, and the cervix was directed frontally toward the urinary bladder [ 38 ]. Investigators found 93% specificity and 75% sensitivity of this sign in detecting adenomyosis [ 22 ].

Power Doppler can be used to distinguish myometrial cysts from blood vessels and discriminate between leiomyomas and focal adenomyosis. Uterine leiomyomas manifest a circular flow along the myoma pseudocapsule, while localized adenomyosis and adenomyomas are characterized by diffusely spread vessels inside the lesions [ 39 ]. 2D ultrasound can yield equivocal result in the case of focal adenomyosis especially if there are coexistent fibroids. A meta-analysis of 14 trials and 1985 participants reported the sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound in the diagnosis of adenomyosis to be as high as 82.5 and 84.6%, respectively, values in line with MRI values [ 40 ].

The use of 3D vaginal ultrasound for the diagnosis of adenomyotic pathology allows a more complete evaluation in the sagittal, transverse and coronal planes, evaluating the ultrasound signs on the acquired 3D volume of the uterus [ 41 ].

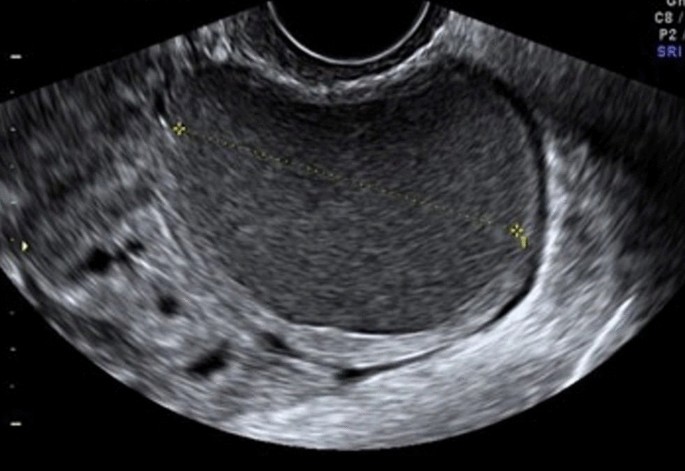

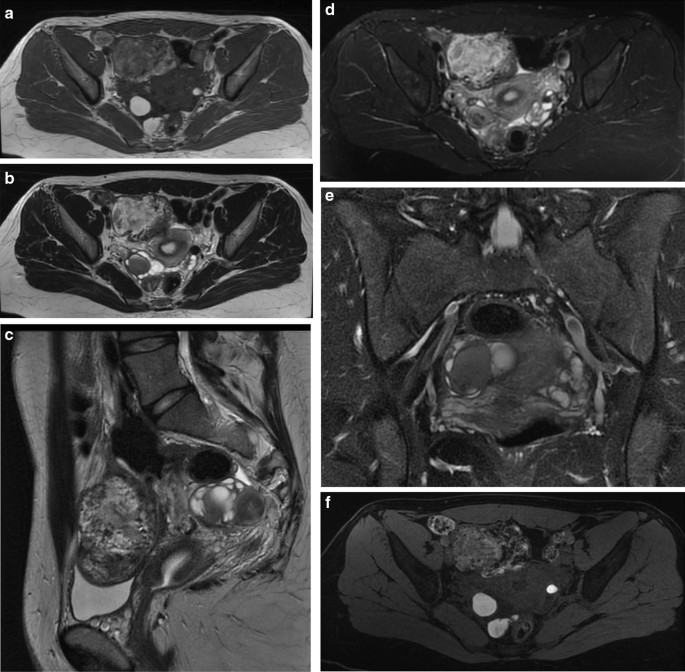

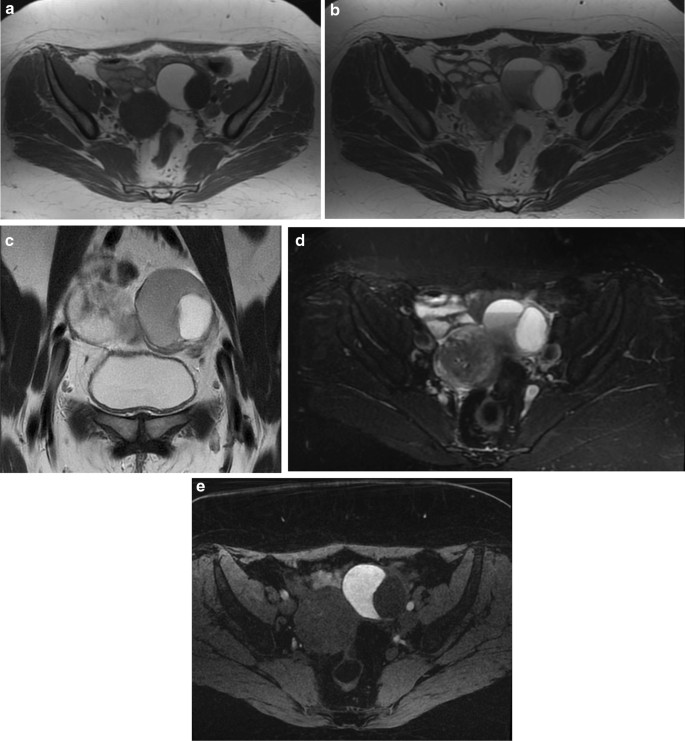

Ovarian endometriomas occur when ectopic endometrial tissue in the ovary hemorrhages, forms a hematoma, enveloped by ovarian parenchyma (Fig. 1 ).

Endometriotic cyst, with regular parenchyma at the periphery, called “crescent sign” characteristic of benign lesions. Absent intralesional vascularization

An ovarian endometrioma has different imaging appearances on US, with the classic appearance being a cyst unilocular or multilocular (less than five locules) with homogeneous low-level echogenicity (ground glass echogenicity) of the cyst fluid, with increased posterior through transmission and no vascularization on color Doppler [ 22 ] (Fig. 2 ).

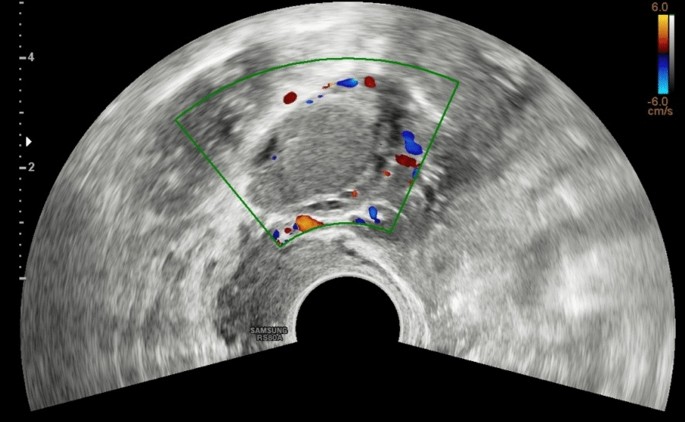

Color Doppler of multiple endometriomas of both ovaries, which appear enlarged and sharpened (ovarian kissing)

Another feature is the presence of peripheral echogenic foci (thought to reflect cholesterol deposits) seen in up to 36% of endometriomas. Endometriomas tend to be multilocular and bilateral (up to 50%) [ 42 ] (Fig. 3 ).

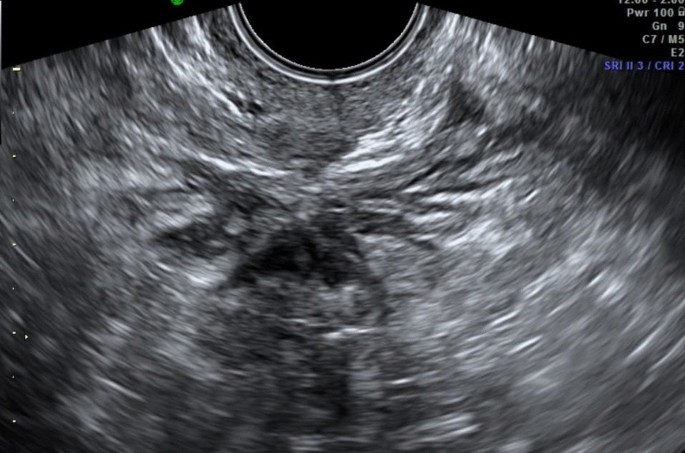

Endometrioma with evidence of the characteristic double fluid–fluid level. Inside the formation, hyperechoic spots can be highlighted, a symptom of hemosiderin accumulation

However, endometriomas may have a variable appearance because of the range of appearance of the internal blood products within them, which can cause fluid–fluid levels, echogenic regions, and papillary projections. In these cases, additional evaluation with MR imaging may be warranted to better evaluate and to exclude malignancy [ 43 ]. There is evidence that ovarian endometriomas originate from ovulatory events and it is likely that the number of endometriomas may increase with age, and multiple endometriomas in the same ovary may assume a multilocular morphology [ 44 ]. Guerriero and colleagues reported that ultrasound appearance of endometriomas differed between premenopausal and postmenopausal patients [ 44 ]. The endometriomas in the postmenopausal patients were less often unilocular cysts and less likely to exhibit ground glass echogenicity [ 27 ].

The primary differential diagnosis of an endometrioma is a hemorrhagic cyst. On US, a hemorrhagic cyst classically has internal reticular strands with retractile clot [ 18 ]. However, these features may not be seen, and instead, homogeneous low-level echoes mimicking that of an endometrioma may be present. Hemorrhagic cysts are unlikely to have the peripheral echogenic foci occasionally seen in endometriomas, and they are less likely to be bilateral or multifocal. Sonographic follow-up demonstrating resolution at 6–12 weeks is diagnostic of a hemorrhagic cyst [ 18 ].

Another differential diagnosis of an endometrioma is an ovarian epithelial neoplasm, which may contain low-level internal homogeneous echoes similar to an endometrioma. This imaging appearance was seen in up to 6% of ovarian serous cystadenomas in the study by Patel et al. [ 42 ] and in up to 20% of mucinous cystadenomas in the study by Van Holsbeke [ 45 ]. To better evaluate for the presence of malignancy (cystadenocarcinomas) in these cases, careful interrogation of the cyst should be performed to assess for internal solid components, such as papillary projections, mural nodules, and thickened septations.

Doppler helps avoid classifying malignancies as endometriomas, especially when evaluating a papillary projection. Generally, these different ultrasound criteria proposed have a sensitivity ranging from 62 to 73%, a specificity of 94–98% [ 46 ].

Masses in postmenopausal women whose cystic contents have a ground glass appearance have a high risk of malignancy. Borderline tumors and carcinomas arising from endometrioid cysts show a vascularized solid component on ultrasound examination [ 47 ].

The uterine tubes can be involved with endometriosis either with adhesions occluding the tube up to 6%) or by DIE foci affecting the tubal walls (up to 26% of the time) [ 18 ].

In case of endometriosis of the tube, we can observe a dilated tube with thick walls and incomplete septa with a fluid dense content similar to an endometrioma (hematosalpinx) [ 48 ]. A “cog-wheel” appearance of the longitudinal folds can be seen when the tube is imaged in cross-section. The presence of a hematosalpinx may be the only sign on imaging of endometriosis in the pelvis [ 49 ].

In case of occlusion of the tube due to adhesion or DIE that involved the distal part and the fimbriae, a hydrosalpinx is seen with the typical “beads-on-a-string” sign, defined as hyperechoic mural nodules measuring approximately 2–3 mm as seen on the cross-section of the fluid-filled distended structure [ 48 ].

The differential diagnosis of a hematosalpinx includes pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) or fallopian tube malignancies. Pyosalpinx of PID can be differentiated clinically by the presence of extreme tenderness on examination as well as the clinical signs of infection (fever, white count). On imaging, hyperemia surrounding the fallopian tube with fatty proliferation/edema in the adjacent fat suggests a pyosalpinx. Fallopian tube carcinoma presents sonographically with solid, vascular internal nodules within the fallopian tube and tends to occur in an older demographic group [ 43 ].

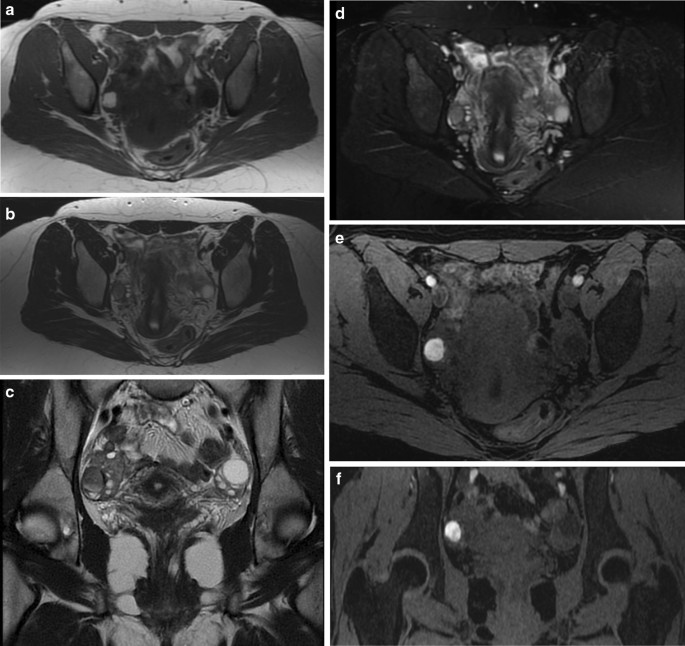

Posterior Compartment

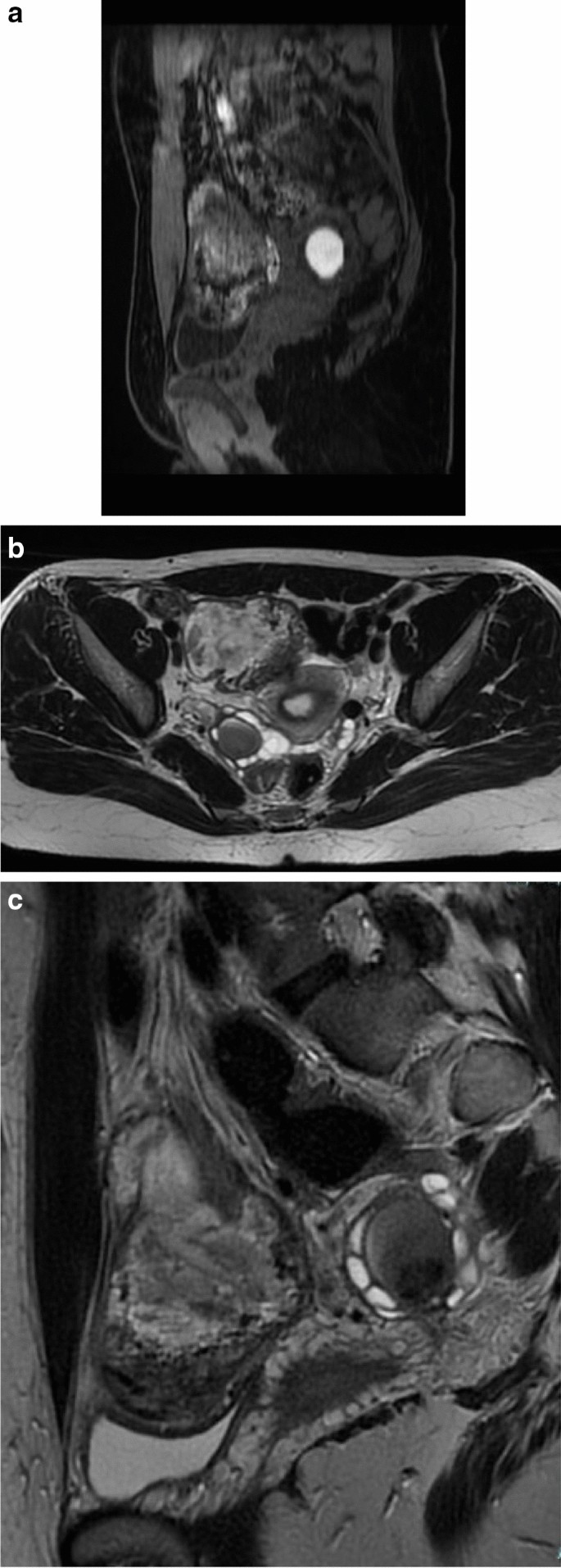

Recently, the ultrasound features of the deep infiltrating endometriosis nodules have been systematically defined by the International Deep Endometriosis Analysis group [ 34 ]. The most common sites of the posterior compartment are posterior vaginal fornix/rectovaginal septum, uterosacral ligaments, anterior rectum/anterior rectosigmoid junction, and sigmoid colon [ 10 ] (Fig. 4 ).

Hypoechoic nodule of the rectosigmoid portion that obliterates the Douglas. At this level, the “sliding sign” can be seen, the sign of the sliding structures on each other which does not occur in the case of endometriosis

Deep endometriosis on sonography is subtle and presents as hypoechoic nodular or infiltrating regions. Occasionally, the infiltrative regions of DIE may have internal hyperechoic foci or complex internal cysts [ 50 ]. The differential diagnosis for DIE includes peritoneal implants; in these cases, to help differential diagnosis, an additional evaluation with MR is recommended [ 18 ]. Three-dimensional (3D) TVS has been also proposed in the evaluation of posterior locations of DIE without intestinal involvement, improving the diagnostic accuracy of 2D ultrasonography [ 51 ].

In the cases of DIE, it is necessary to describe of the anatomical localizations, the size and number of DIE nodules, the depth of infiltration of the nodules, and the degree of stenosis of the bowel lumen which is important to plan the surgical procedures [ 22 ].

Uterosacral Ligaments

The uterosacral ligaments (USL) are usually not visible on ultrasound. The uterosacral ligaments affected by deep infiltrating endometriosis can be seen in the longitudinal view of the uterus at the insertion on the posterior lateral cervix wall, as hypoechoic tissue, with regular/irregular margins within the peritoneal fat surrounding the uterosacral ligaments [ 13 ]. On the transverse cervical section, these hypoechoic nodules appear on the posterior lateral part of the cervix and interrupt the hyperechoic external cervical fascia. Sometimes, the uterosacral ligaments appear thickened and hyperechoic, probably as the morphologic expression of fibrosis, due to the chronic process of inflammation [ 27 ].

USLs lesions may be isolated or may be part of a larger nodule extending into the vagina or into other surrounding structures. In some cases, the DIE lesion involving the USL is located at the torus uterinus as a central thickening of the retrocervical area between USLs [ 52 ]. Two recent meta-analyses of USL endometriosis have reported pooled sensitivities and specificities of 53–64% and 93–97%, respectively [ 53 ].